Abstract

Individualizing cancer therapy for molecular targeted inhibitors requires a new class of molecular profiling technology that can map the functional state of the cancer cell signal pathways containing the drug targets. Reverse phase protein microarrays (RPMA) are a technology platform designed for quantitative, multiplexed analysis of specific phosphorylated, cleaved, or total (phosphorylated and non‐phosphorylated) forms of cellular proteins from a limited amount of sample. This class of microarray can be used to interrogate tissue samples, cells, serum, or body fluids. RPMA were previously a research tool; now this technology has graduated to use in research clinical trials with clinical grade sensitivity and precision. In this review we describe the application of RPMA for multiplexed signal pathway analysis in therapeutic monitoring, biomarker discovery, and evaluation of pharmaceutical targets, and conclude with a summary of the technical aspects of RPMA construction and analysis.

Keywords: Biomarker, Individualized therapy, Microarray, Protein, Phosphoprotein, Reverse phase protein microarray

Abbreviations

- CAP/CLIA

College of American Pathologists/Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments

- DAB

Diaminobenzidine

- LCM

Laser capture microdissection

- LMW

Low molecular weight

- MS

Mass spectrometry

- NOD/SCID

Non-obese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient

- NSCLC

Non-small cell lung cancer

- RPMA

Reverse phase protein microarray

- SH2

Src homology 2 binding domain

1. Introduction

Practicing oncologists are the first to recognize the individuality of the cancer treatment response. Tumors with vastly different clinical outcomes can look the same at the microscopic level. The advent of immunohistochemistry in the last century to further sub‐classify tumors based on histomorphology has added a significant dimension to clinical diagnostics. Nevertheless, tumor diagnostics are largely still based on morphologic patterns. It is assumed that the staining pattern, nuclear shape and contour, cellular configuration, and pleomorphism of a particular neoplastic lesion are the outward manifestation of molecular changes that are occurring inside cells within the tumor microenvironment. The dogma of molecular oncology is that genes, proteins and other molecules that drive the biologic behaviour of an individual patient's tumor are knowable, and can explain or predict why one patient's tumor regresses while another patient's tumor recurs (Baak et al., 2003, 2006, 2006, 2005). The next generation of cancer therapies is providing great optimism that we can reach a new level of efficacy if the therapy is tailored to the molecular make‐up of each patient's tumor cells (see “Targeted nanoagents for the detection of cancers” by McCarthy et al., 2010). Over the past five years considerable progress has been made in the use of genetic and genomic profiling to individualize chemotherapy (Chow, 2010; Gangadhar and Schilsky, 2010). Nevertheless, the future of cancer treatment is molecular therapy, such as kinase inhibitors that target protein signal pathways (Liotta and Petricoin 2001, 2003, 2003). Individualizing molecular therapy will require a new class of proteomic profiling technology because genomics cannot provide direct information regarding the state of protein signaling pathways that contain the target of these new molecular targeted inhibitors. Protein microarrays, and in particular Reverse Phase Protein Microarrays (RPMA) are a widely adopted technology that can meet this need for the profiling of the functional state of cellular signal pathways. RPMA technology has graduated from the realm of basic science to the level of clinical trial implementation (Table 1). As such, the focus of this review is on ongoing research clinical trial applications using RPMA.

Table 1.

Example clinical trials incorporating reverse phase protein microarray analysis.

| Trial identifiera | Acronym | Conditions | Study design | Phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT01042379 | I‐SPY 2 | Breast cancer | Open‐label; interventional | II |

| NCT01023477 | PINC | Breast DCISb | Open‐label; interventional | I/II |

| NCT01074814 | Side‐out | Metastatic breast cancer | Open‐label; interventional | II/III |

| NCT00798655 | N/A | Head and neck cancer | Open‐label; interventional | II |

| NCT00952809 | N/A | Lymphoma | Observational | N/A |

| NCT00867334 | NITMEC | Colorectal cancer | Open‐label; interventional | II/III |

Clinicaltrials.gov identifier accessed from http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/home, provided by the U.S. National Library of Medicine, as of April 15, 2010.

DCIS = ductal carcinoma in situ.

1.1. Molecular Pathology: the role of clinical proteomics

While individualized treatments have been used in medicine for years (Jain, 2002), advances in cancer treatment have now generated a need to more precisely define and identify patients that will derive the most benefit from molecular targeted agents (Pierotti et al., 2010). Even though general morphological parameters including tumor size, degree of tumor cell differentiation, presence or absence of metastases, cytogenetic analysis, and immunohistochemical classification of proteins such as HER2/neu play an important role in therapeutic decision making, they fail to address the molecular complexity and heterogeneity of individual tumors that can lead to success or failure of a targeted therapeutic agent. Genomic profiling using gene expression arrays has shown considerable potential for the classification of patient populations (Brennan et al., 2005). Nevertheless, transcript profiling, by itself, provides an incomplete picture of the dynamic molecular network for a number of clinically important reasons. First, gene transcript levels have not been found to correlate significantly with protein expression or the functional (often phosphorylated) forms of the encoded proteins (Nishizuka et al., 2003). RNA transcripts also provide little information about protein–protein interactions and the state of the cellular signaling pathways (Celis and Gromov, 2003; Hunter, 2000). The discordance between transcript data and protein expression data was shown in a proteomic and transcriptomic study in a panel of 60 human cell lines (NCI‐60), representing 9 tissue types (Shankavaram et al., 2007). RPMA protein expression analysis coupled with Affymetrix human gene chip (HG‐U95 and HG‐U133A) microarray data was developed as a “consensus set” revealing that only 65% of gene transcripts were significantly associated with protein data and emphasized the utility of kinase network pathway data for individualized therapy based on proteomic information. For this reason, it has been recognized that RPMA technology may provide a previously missing class of information useful in screening candidate cancer drugs (Havaleshko et al., 2009). Ma et al. developed a computational model system, based on 52 proteins from Nishizuka et al.'s RPMA analysis of the NCI‐60 cell line, to classify drug sensitivity for 118 different compounds (Ma et al., 2006, 2009, 2003). The conclusion was that RPMA analysis provided a feasible means to predict chemosensitivity.

The new class of molecular therapeutics is directed at protein targets, and these targets are often protein kinases and/or their substrates. The human “kinome”, or full complement of kinases encoded by the human genome, comprises the molecular networks and signaling pathways of the cell, or secreted proteins in the circulation (see Karagiannis et al., 2010). The activation state of these proteins and networks fluctuate constantly depending on the cellular microenvironment. Consequently, the source material for molecular profiling studies needs to shift from in vitro models to the use of actual diseased human tissue. Schwamborn and Caprioli (2010) show the evolving role of coupling imaging to molecular analysis for correlating histomorphology of a patient's tissue with molecular markers. The application of molecular profiling to provide individually tailored therapy should include direct proteomic pathway analysis of patient material. Moreover, because the kinome represents a rich source for new molecular targeted therapeutics, technologies that can broadly profile and assess the activity of the human kinome will be critical for the realization of patient‐tailored therapy.

1.2. Reverse phase protein microarray historical perspective

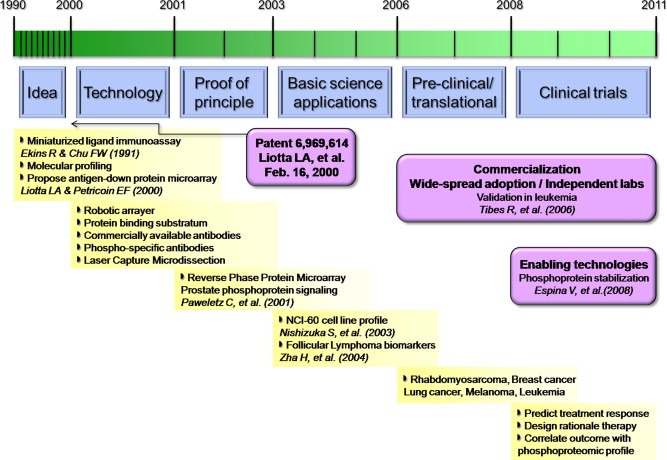

Reverse phase protein microarrays are a direct descendent of miniaturized immunoassays (Ekins, 1989; Ekins and Chu, 1991). The introduction of gene expression microarray technology in 1995 (Schena et al., 1995) provided researchers with technology needed to fabricate high‐throughput protein microarrays. Prior to development of RPMA, immunoassays and protein microarrays were generally sandwich‐style assays in which one antibody was used to capture the analyte of interest and a second antibody, directed against a different epitope on the same protein, was used as a detection molecule (Celis et al., 2004; Haab et al., 2001; Sanchez‐Carbayo, 2006). An early iteration of future RPMA was a ‘dot blot’, which was constructed by manually depositing protein samples on a membrane. Dot blotting was labor intensive and could only accommodate a few samples per blot. Advances in technology related to molecular profiling such as laser capture microdissection (Emmert‐Buck et al., 1996), pin‐and‐ring and quill pin style robotic arrayers, and commercially available phospho‐specific antibodies, were the basis of “antigen‐down” microarrays (Liotta and Petricoin, 2000; MacBeath and Schreiber, 2000) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Maturation of reverse phase protein microarray technology. Within the past 20 years, concepts regarding miniaturization of immunoassays, molecular profiling, gene expression microarrays, and protein microarrays have evolved into the “antigen‐down” class of reverse phase protein microarrays. Technological improvements in robotic arrayers and protein binding substratum, in combination with the availability of phospho‐specific antibodies and commercial laser capture microdissection instruments, enabled the production of high‐throughput reverse phase protein microarrays generated from a small microdissected tissue sample. Basic science applications provided proof‐of‐concept in multiple tissues and disease states. Independent laboratories validated the RPMA technology, and the array format was widely adopted for pre‐clinical studies using microdissected and non‐microdissected tissue, cells lines, serum, and body fluids. Enabling technologies such as phosphoprotein preservative solutions have helped mature the RPMA into a robust, reproducible research clinical trial tool for assessing the state of cell signaling proteins, predicting therapy response, and prospectively correlating outcome with proteomic profiles.

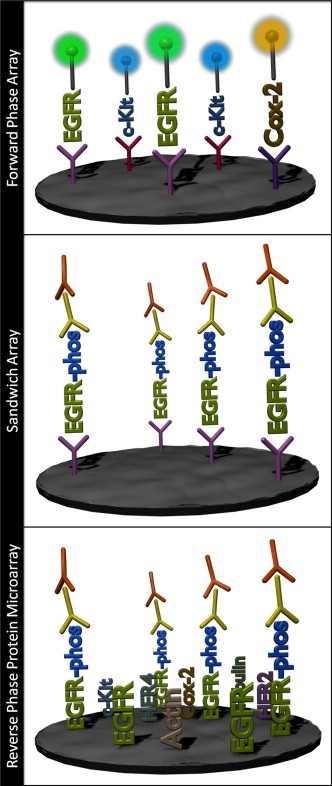

The term “reverse phase” refers to the fact that the analyte (antigen) is immobilized as a capture molecule, rather than immobilizing an antibody as the capture molecule (Liotta et al., 2003, 2003) (Figure 2). The term reverse phase protein microarray was coined by Paweletz et al. in the seminal paper describing the technology for its application to cell signaling analysis of laser capture microdissected pre‐malignant prostate lesions (Figure 1) (Paweletz et al., 2001, 2001). Each microarray consists of a self‐contained assay comprised of duplicate/triplicate samples, controls and calibrators that are analyzed with one class of antibody and amplification chemistry. Since this time, terms used in the literature include “lysate array” (Posadas et al., 2005), reverse phase lysate microarrays (Romeo et al., 2006), and protein microarray (Belluco et al., 2005; Korf et al., 2008). On a side note, the protein microarray field would benefit from adoption of standardized nomenclature to help differentiate reverse phase protein microarrays from sandwich‐style (antibody) microarrays, as well as establishing a standard database search term.

Figure 2.

Protein microarray formats. Reverse phase protein microarrays have been referred to as ‘protein microarrays’, ‘lysate arrays’, and ‘tissue lysate arrays’ in the literature but not all protein microarrays are reverse phase microarrays. In general, 3 classes of protein microarrays exist: forward phase, sandwich, and reverse phase. In a forward phase, or antibody array, multiple antibodies are immobilized on a surface to capture proteins from a sample. Sandwich arrays require a pair of antibodies to capture the protein of interest and to detect the analyte. Each antibody of a sandwich assay must be able to detect unique epitopes of the same analyte on the sample. The reverse phase format consists of immobilizing the analyte protein on a surface and probing the array with a single antibody directed against the analyte of interest.

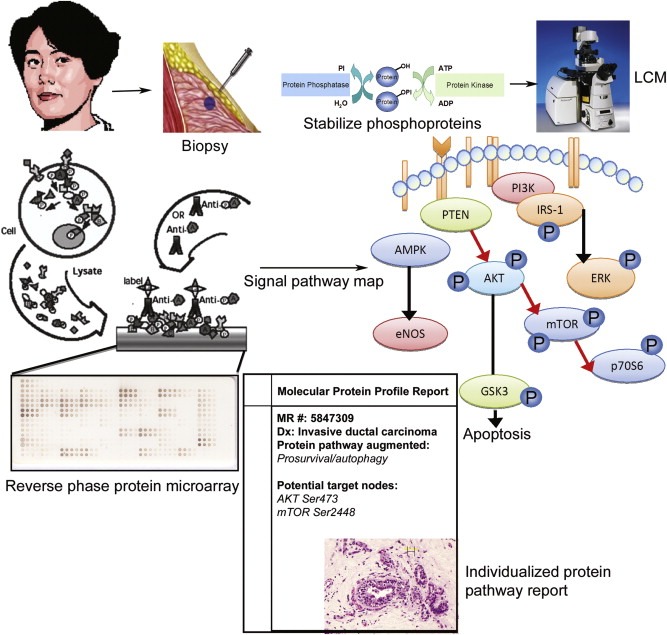

While RPMA were originally developed to quantitatively measure numerous proteins extracted from a small number of cells obtained from tissue microdissection (Belluco et al., 2005, 2005, 2005, 2005, 2007, 2005, 2010, 2008, 2008), the technology has been used in pre‐clinical studies of heterogeneous tissue samples (Agarwal et al., 2009; Gonzalez‐Angulo et al., 2009; Hennessy et al., 2009; Jiang et al., 2006), cell lines (Mazzone et al., 2010; Moore et al., 2009; Nishizuka et al., 2003; Srivastava et al., 2004; Zhou et al., 2007), and serum/plasma (Aguilar‐Mahecha et al., 2009, 2005, 2009, 2009, 2010) (Figure 3). Despite the differences in sample types, each RPMA makes it possible to evaluate the state of entire portions of a signaling pathway or cascade, even though the cell is lysed, by quantitatively analyzing phosphorylated, glycosylated, acetylated, cleaved, or total cellular proteins from multiple samples printed on a series of identical arrays (Liotta et al., 2003, 2003). Many identical arrays can be measured in parallel using commercially available anti‐phosphoprotein or other specific antibodies (Spurrier et al., 2008).

Figure 3.

Clinical workflow for personalized medicine. Reverse phase protein microarrays were originally developed to profile cell signaling proteins from microdissected tissue samples. In current ongoing clinical trials a patient's biopsy is preserved in a novel preservative solution that retains both cellular antigenicity and histomorphology. Cells of interest are procured by laser capture microdissection, lysed, and printed on a reverse phase protein microarray. Multiple independent arrays are analyzed with a single antibody per array in order to map the state of the cellular signaling network. The final result can be an individualized therapy report or protein network analysis. (ArcturusXT laser capture microdissection photo courtesy of Applied Biosystems/Life Technologies).

The emphasis of this review is on the application of RPMA technology to clinical translational research. We will summarize the goals of clinical trials and show how RPMA are a necessary component. Examples of pre‐clinical and basic science applications will also be reviewed and we will summarize the technical aspects of constructing, staining, and analyzing RPMA.

2. Advances in clinical trial applications of reverse phase protein microarrays

2.1. Protein stability and pre‐analytical variability

As technologies advance from initial conception to clinical applications, one must consider the entire spectrum of clinical assay variability, including pre‐analytical as well as post‐analytical events, which could potentially impact the final result. The promise of tissue protein biomarkers to provide revolutionary diagnostic and therapeutic information will never be realized unless the problem of tissue protein biomarker instability is recognized, studied, and solved. Cells within a tissue biopsy react and adapt to the trauma of excision, ischemia, hypoxia, acidosis, accumulation of cellular waste, absence of electrolytes, and temperature changes (Espina et al., 2008; Spruessel et al., 2004). A large surge of stress, hypoxia, and wound repair related signal pathway proteins and transcription factors are induced in the tissue immediately following procurement (Li et al., 2003, 2005). Investigators in the past have worried about the effects of vascular clamping and anesthesia, prior to excision, on the fidelity of molecular data in tissues (Dash et al., 2002). A much more significant and underappreciated issue is the fact that excised tissue is alive and reacting to ex vivo stress (Espina et al., 2008). During the ex vivo time period, because the tissue cells are alive and reactive, phosphorylation of certain kinase substrates may transiently increase due to the persistence of functional signaling, activation by hypoxia, or some other stress‐response signal (Espina et al., 2008; Grellner, 2002; Grellner and Madea, 2007; Grellner et al., 2005). Without stabilization, imbalances of kinases/phosphatases will significantly distort the tissue's molecular signature compared to the state of in vivo markers.

Biomarker preservation becomes critically important in community‐based hospitals or multi‐center clinical trial sites, where the living, reacting tissue may remain in the collection container for hours or must be shipped to a different facility for processing/analysis. At any point in time within the tissue cellular microenvironment, the phosphorylated state of a protein is a function of the local stoichiometry of associated kinases and phosphatases specific for the phosphorylated residue. Thus, in the absence of kinase activity, proteins may be dephosphorylated by phosphatases, reducing the level of a phosphoprotein analyte causing a false negative result. This can be prevented by a variety of chemical‐ and protein‐based phosphatase inhibitors (Goldstein, 2002; Neel and Tonks, 1997). However if the kinase remains active, then the addition of a phosphatase inhibitor alone will result in an augmentation of the phospho‐epitope, generating a false‐positive result. Consequently, cellular samples for RPMA kinase network analysis require stabilization, or preservation, of the kinases and phosphoproteins immediately post tissue procurement (Espina et al., 2008). Enabling technologies such as molecular fixatives that arrest both sides of the kinase/phosphatase balance are currently being evaluated in clinical research trials for their compatibility with RPMA analysis (Figure 1) (Espina et al., 2008, 2009).

2.2. Clinical applications of RPMA

Historically, cancer diagnosis and treatment has been categorized based on morphological and histological analysis of the tumor. Although histological analysis provides information regarding tumor type, stage, and cellular differentiation, it does not provide quantitative information for protein post‐translational modifications such as phosphorylation or cleavage events. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors bind protein receptors, interfering with receptor dimerization and subsequent autophosphorylation events (Hynes and Lane, 2005). The activity or quantity of individual proteins or their post‐translationally modified forms, both upstream and downstream from the receptor or drug target, can be used to predict a patient's response to therapy, as well as monitor therapy and disease progression (Agarwal et al., 2009; Gonzalez‐Angulo et al., 2009; Havaleshko et al., 2009; Petricoin et al., 2007; VanMeter et al., 2008). In the last decade considerable interest has focused on the prospect of tailoring therapy to an individual patient's tumor. This new concept emanated from the growing awareness that every disease develops as a unique molecular entity in the context of the patient's individual genetic background. Thus two tumors could look the same under the microscope but they could be driven by different renegade signal pathways. Consequently a treatment that effectively targets one patient's tumor may not work for another patient. For this reason, we may treat a population of cancer patients with the same drug but only a small percentage will respond (Humphery‐Smith et al., 2002). Quantitative analysis of the specific phosphorylation events offers an approach to profile the activity state of pathways that contain the drug targets, in addition to deciphering off‐target effects. Knowing the activity state of the signal pathways in a patient's tumor is therefore considered a key to separating responders from non‐responders (Petricoin et al., 2007).

The intracellular information network delicately regulates, by internal feedback processes, cellular homeostasis. This intracellular balance is carefully maintained by constant rearrangements of the post‐translational modification of proteins through the activity of a series of kinases, phosphatases, deacetylases, or proteolytic enzymes. As a consequence, the study of these kinase and phosphatase events is a fundamental aspect for understanding and characterizing cellular activities in a variety of normal and/or disease processes (Alizadeh et al., 2000) (Figure 3).

The concept of personalized therapy based on an individual patient's molecular profile will hopefully provide clinicians with information required to effectively treat each patient's disease while minimizing toxicity, and sparing unnecessary treatment. With this overall goal in mind, reverse phase protein arrays can provide a rapid, quantitative readout of post‐translational modifications and kinase levels. RPMA are uniquely suited for profiling the state of in vivo kinase signaling networks from human clinical tissue samples due to the minimal total cellular volume requirements, high sensitivity (femtogram–attogram range), and good precision (<15% CV) (Dupuy et al., 2009, 2001, 2001, 2005, 2006, 2008).

2.2.1. RPMA in the molecular oncology clinic

RPMA have been successfully applied to the analysis of the state of prosurvival, apoptosis and mitogenesis pathways within microdissected human malignant lesions, including comparisons to adjacent normal epithelium, invasive carcinoma, or host stroma (Belluco et al., 2005, 2008, 2003, 2005, 2001, 2001, 2005, 2007, 2008, 2003, 2008). Patient clinical information, combined with protein network data obtained from RPMA, provide insights into the mechanisms of receptor blockade, compensatory post treatment receptor activation, and overall differences in pathway signaling between patients, and/or between treatment arms. Pre‐clinical data generated from RPMA performed following professional and federal laboratory standards (College of American Pathologists/Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CAP/CLIA)) has propelled the technology into several clinical research trials (Espina et al., 2010; Petricoin et al., 2007; Wulfkuhle et al., 2008) (Table 1). Information pertaining to the clinical trials was obtained from the sponsor or from Clinicaltrials.gov accessed from http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/home, provided by the U.S. National Library of Medicine, as of April 15, 2010.

2.2.2. I‐SPY 1 and I‐SPY 2 breast cancer clinical trials

I‐SPY 1 and I‐SPY 2 (Investigation of Serial Studies to Predict Your Therapeutic Response with Imaging and Molecular Analysis) are a series of national clinical trials sponsored by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (USA) for patients with stage II/III breast cancer. I‐SPY 1 completed enrollment, while I‐SPY 2 is currently recruiting (Table 1). A primary objective of I‐SPY 1 was to establish a research infrastructure for combining imaging, comparative genomic hybridization (CGH), gene expression, fluorescent in situ hybridization, immunohistochemistry, and RPMA data that were generated at independent research centers. Within this infrastructure, data‐sharing portals were developed at the National Institutes of Health to a) integrate information from the research sites, b) determine molecular predictors of response and outcome to standard neoadjuvant therapy, as well as the c) development of non‐invasive (magnetic resonance imaging) markers of response. I‐SPY 1 was the first clinical trial in which the reverse phase protein microarray analysis of frozen core needle biopsies was reduced to practice in a CAP/CLIA compliant laboratory. CAP/CLIA provide professional and federal (USA) guidelines for clinical laboratory analysis.

For most of the clinical research studies referenced here, the cancer cell, or the stromal cell, subpopulation in the tissue is harvested with Laser Capture Microdissection prior to RPMA analysis of signaling networks. Wulfkuhle et al. confirmed the lack of concordance and diminished protein signaling levels in non‐microdissected whole tissue lysate samples compared to microdissected samples (Wulfkuhle et al., 2008), affirming the requirement for microdissection to obtain an accurate portrait of the tumor cells. The success of I‐SPY 1 has lead to the establishment of I‐SPY 2 in which an adaptive trial design will be used to correlate response and outcome with molecular targeted inhibitors (Figitumumab/Neratinib/ABT‐888).

2.2.3. New individualized therapy trial for metastatic colorectal cancer (NITMEC) trial

RPMA are flexible assays in the sense that the arrays can be probed with any given panel of validated antibodies, essentially providing a custom pathway network profile based on the disease, drug target(s), patient population, or pathway. An urgent clinical need exists to identify new drug targets for metastatic lesions, particularly in late stage disease which has the poorest prognosis. RPMA data may be of tremendous importance for personalized therapy and patient stratification because the metastasis cell signaling network is different from the primary tumor due to the microenvironment tumor niche (Liotta and Kohn 2001; Mendoza and Khanna, 2009).

The extent of cell signaling changes associated with metastasis, and insights into the relative role of the “seed” and “soil” in patients with primary colorectal cancer concomitant with hepatic metastasis, was the basis for developing a score to stratify patients for a Phase I/II study (NITMEC, Table 1) of imatinib alone or in combination with panitumumab. The score was developed based on RPMA data from a population of hepatic metastases, derived from primary colorectal cancer tumors, which indicated that a high percentage of liver metastasis with wild type KRAS had high levels of phosphorylated c‐KIT and PDGF; thus implying that the liver metastasis may be sensitive to imatinib. Investigators in the NITMEC trial are profiling hepatic metastasis samples procured by laser capture microdissection, rather than profiling the primary colorectal tumor, to evaluate the feasibility of a predefined lab score based on proteomic data and whether it can predict which patients will respond to imatinib treatment (Belluco et al., 2005).

2.2.4. Side‐out refractory breast cancer clinical trial

The purpose of this trial, sponsored by the Side Out Foundation and TGen Drug Development Services, is to employ molecular profiling to individualize therapy for patients with refractory, metastatic breast cancer (Table 1). In order to assess whether individualized therapy can change the clinical course of disease a Growth Modulation Index (GMI) will be calculated for each patient. The GMI is calculated as the ratio of Progression‐free survival (PFS) under the individualized therapy to the time to progression (TTP) for the most recent regimen on which the patient has progressed.

Biopsies of the metastatic disease are analyzed using immunohistochemistry, transcript arrays, and RPMA. For the RPMA portion of the study, biopsies are subjected to laser capture microdissection and the activated state of selected signal pathways is scored compared to a series of cell line derived calibrators printed on each array. The RPMA generated value for a selected set of endpoints is compared to a previously gathered reference set of data from breast and lung metastasis samples. The purpose of this comparison is to determine if an individual patient falls in the top, or bottom, quartile compared to the reference population. Data from immunohistochemistry, transcript arrays, and RPMA proteomics is used to select therapy for each individual patient. Genomic and proteomics data correlations are being assessed in this trial because the optimal therapy, as predicted by the molecular analysis, may be chemotherapy rather than molecular therapy. For this trial, the RPMA data is being used to select molecular targeted therapy such as kinase inhibitors. Genomics cannot provide information on the activated (e.g. phosphorylated) state of signal pathway proteins existing within a signal pathway targeted by the kinase inhibitor, therefore genomic data is being used to chose chemotherapy regimens. Thus combining these two classes of molecular analysis covers both chemotherapy and molecular targeted therapy.

2.2.5. Prevention of Invasive breast Neoplasia by Chloroquine (PINC) trial

Prevention of Invasive breast Neoplasia by Chloroquine (PINC) is a new neoadjuvant therapy trial for patients with breast ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) sponsored by Inova Health Systems (USA) (Table 1). The human DCIS neoadjuvant therapeutic target is the autophagy pathway and the proposed treatment is oral Aralen (chloroquine phosphate). The therapeutic strategy is based on data from Espina et al. that supports the hypothesis that cellular autophagy is necessary for the survival and propagation of DCIS neoplastic cells (Espina et al., 2010). The novel design of the study provides immediate molecular and biological feedback regarding the treatment impact on the neoplastic cell target. The clinical study will examine the safety and effectiveness of Aralen administration for a 12‐week period to patients with low, intermediate and high grade DCIS. Patients with estrogen receptor (ER) positive high grade DCIS will receive standard of care tamoxifen (20 mg/day), plus Aralen (500 mg/week). Patients with low grade, ER + DCIS, will receive tamoxifen only. Patients who are ER negative (expected to be approximately one half of the high grade DCIS cases) will receive Aralen only. Magnetic Resonance Imaging studies will be performed on each patient at enrollment and just before surgical therapy after the 12‐week treatment. All patients will receive standard of care surgical therapy: mastectomy or lumpectomy depending on the size and confluence of the primary DCIS lesion.

Effectiveness in this study will be measured in two ways directly at the molecular level in the DCIS tissue before and after treatment. Using RPMA technology, the activated state of 100 signal pathway proteins associated with autophagy, hypoxia, adhesion apoptosis, and p53 mediated cell survival will be measured before and after therapy within the microdissected epithelial and stromal compartments. In parallel, DCIS living organoids and DCIS progenitor cells, pre‐ and post‐treatment, will be harvested and studied for a) ex vivo invasive potential in human breast stroma, b) progenitor cell yield and growth, and c) the tumorigenicity and invasion following NOD/SCID (non‐obese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient) murine transplantation. Full genome molecular cytogenetics will be performed on the microdissected DCIS cells.

2.2.6. Phase II trial of Trastuzumab and/or Lapatinib plus chemotherapy for Her2+ breast cancer

US Oncology 05‐074/GlaxoSmithKline LPT109096 sponsored trial, “Phase II randomized trial of neoadjuvant Trastuzumab and/or Lapatinib plus chemotherapy in women with ErbB2 (HER2/neu) over‐expressing invasive breast cancer”, recently completed patient accrual (n = 100). RPMA are providing quantitative cell signaling data related to the in vivo effects of molecular‐targeted therapy before and after therapy. This multi‐site trial has established a proteomic workflow for breast core needle biopsy collection, preservation, and shipping without the need for dry ice or frozen samples. Core needle biopsies are placed immediately in a phosphoprotein/kinase preservative that retains sample antigenicity and morphology, and is compatible with laser capture microdissection and frozen section preparation (Espina et al., 2008). Two important questions related to molecular targeted therapy are being addressed via RPMA data in this clinical trial: 1. Does mono or combination Her2 inhibition therapy improve complete patient response?; and 2. Can we prospectively identify responders to Her2 targeted therapy?

Lapatinib and trastuzumab have different modes of action on the Her2/EGFR signaling cascade. Lapatinib, a small molecule inhibitor, is a dual tyrosine kinase inhibitor that blocks both EGFR (ErbB1) and Her2 (ErbB2) by binding to the ATP pocket. In addition, lapatinib can inhibit truncated forms of the receptor (Medina and Goodin, 2008), while trastuzumab, a monoclonal antibody, binds directly to the Her2 extra‐cellular domain (Goldenberg, 1999). Despite numerous studies, we still don't understand the mechanism or significance of ErbB blockade, particularly for an individual patient. Molecular profiling provides a means to individualize therapy for tyrosine kinase inhibitors used in combination or as monotherapy. This is the first in vivo proteomic monitoring trial of signal pathway targets before and after mono or dual therapy. HER2+ breast cancer patients are treated with Lapatinib alone, Lapatinib plus Trastuzumab, or Trastuzumab alone for 2 weeks, before chemotherapy with FEC75 ×4 followed by weekly paclitaxel ×12. In this trial RPMAs are being used to: 1) identify kinase signal pathway activation states in microdissected tumor cells collected prior to therapy (biopsy one), or during therapy (biopsy two), which predict later clinical response following standard of care chemotherapy and surgery; and 2) identify kinase pathway interconnections in the cancer cells that are altered in response to therapy. Changes in compensatory or inter‐connected proteins could indicate off‐target effects or provide insights for new combination therapies.

2.2.7. Phase II trial of radiation, cisplatin, and panitumumab in head and neck cancer

The University of Pittsburgh sponsored trial (NCT00798655; Table 1) for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck will evaluate progression‐free survival of patients undergoing post‐operative chemoradiotherapy with panitumumab. Patient inclusion criteria include status post‐surgical resection, with stage III/IVa tumors, without any prior chemotherapy or EGFR pathway inhibitor therapy. RPMA are being used in baseline archival paraffin‐embedded tumor tissue samples to correlate potential efficacy parameters with EGFR, angiogenesis, and downstream pathway activation for at least 17 total or phosphorylated cell signaling proteins, including EGFR, pEGFR, pSTAT5, p38, p21, PARP, Ki‐67 and IL‐8. Data will be correlated with additional parameters including FcyR polymorphisms, and tumor and serum cytokines.

2.3. Translational research applications of RPMA: retrospective analysis of tissue specimens

Translational studies using frozen tissue samples matched with appropriate clinical outcome have shown that RPMA can measure the state of kinase signaling pathways to provide clues regarding prognostic markers and the identification of drug targets. Non‐cancer applications have included newborn screening for inherited immunodeficiency disorders due to the loss of the third component of complement (C3) (Janzi et al., 2009).

2.3.1. Childhood rhabdomyosarcoma

Despite combination chemotherapy, 40% of children with Rhabdomyosarcoma fail to respond to current combination therapy. Petricoin et al. applied RPMA and laser capture microdissection technology to address the lack of chemotherapy response in a set of frozen tissue samples obtained from a subset of children with Rhabdomyosarcoma enrolled in the Children's Oncology Group Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study (IRS) IV, D9502 and D9803 (Petricoin et al., 2007). Embryonal, alveolar and botyroid histological tumor subtypes were microdissected and profiled by RPMA for a set of endpoints that were hypothesized to be implicated in Rhabdomyosarcoma. Tumor histological subtype (embryonal, alveolar and botyroid) is a known prognostic indicator, with alveolar considered a poor prognostic factor due to translocations t(2:13) or t(1:13), which result in PAX3‐FKHR or PAX7‐FKHR fusion genes (Mercado and Barr, 2007). Although the histological subtype was not correlated with protein signaling network data, an altered interconnection between phosphorylated forms of mTOR, IRS‐1 and AKT proteins in the therapy non‐responder cohort compared to the therapy responders was discovered in the patient tumors (Petricoin et al., 2007). CCI‐779, an mTOR inhibitor, was able to reduce tumor burden in a mouse xenograft model of Rhabdomyosarcoma, confirming the significance of the AKT/mTOR pathway (Petricoin et al., 2007). This disrupted prosurvival/growth feedback loop was suggested to be an effective drug target for treatment with mTOR and/or IRS inhibitors prior to standard chemotherapy.

2.3.2. Breast cancer

Tumor recurrence and metastasis may be driven by the tumor microenvironment (Liotta and Stracke, 1988) as well as by tumor progenitor cells (Bonuccelli et al., 2009; Espina et al., 2010). Stroma/tumor interactions influence signaling networks. The implications of protein expression on patient outcomes have been correlated via RPMA and transcript profiling for breast cancer samples stored in tissue biobanks (Agarwal et al., 2009; Gonzalez‐Angulo et al., 2009; Hennessy et al., 2009). Cyclins B1, D1, and E1 regulate cell cycle progression. Their differential expression in heterogeneous, frozen breast tissue samples and 53 cell lines was evaluated by RPMA analysis and transcriptional profiling (Agarwal et al., 2009). Elevated levels of Cyclin B1, in the presence of normal copy numbers of the CCNB1 gene, in this study set correlated with the hormone receptor‐positive breast cancers suggesting that Cyclin B1 inhibitors may have therapeutic potential for this subset of hormone positive tumors. This same group also retrospectively evaluated breast tumor pathogenesis driven, in some cases, by steroid family hormones including estrogen, progesterone, or androgens in conjunction with mass spectrometry identification of single nucleotide polymorphism alterations in the PI3K gene (Gonzalez‐Angulo et al., 2009). Androgen receptor signaling and cross‐talk with Phosphoinositide kinase (PI3K) pathway proteins were profiled from a cohort of 347 non‐microdissected frozen tissue samples from a biobank. Androgen receptor levels were found to be highest in the estrogen/progesterone receptor‐positive subset and thus may aid in classifying breast tumors for treatment/prognosis (Gonzalez‐Angulo et al., 2009).

2.3.3. Hematologic malignancies

Follicular lymphoma and multiple myeloma are examples of incurable diseases with marked clinical heterogeneity (Horning, 2000; Raab et al., 2009). In both cases, patients may survive for years with indolent disease or succumb rapidly to aggressive disease. Combination chemotherapy regimens, and newer molecular targeted inhibitors, have provided remission periods, yet relapses occur and ultimately progress to death (Hideshima et al., 2007). Known genetic translocations such as t(14:18) in follicular lymphoma (Tsujimoto et al., 1985, 1985) or t(11:14) and t(4:14) in myeloma (Hideshima et al., 2007) provide prognostic information, while protein signaling network analysis provides functional profiles for designing individualized therapy regimens. B‐Cell lymphoma is a disease of the apoptosis pathway caused, at least in part, by genetic translocations that lead to Bcl‐2 overexpression, which is a potent apoptosis inhibitor (Gulmann et al., 2005, 1985, 1985; Zha et al., 2004). Transcript analysis alone cannot reveal the functional state of the apoptotic pathway. Apoptosis activation depends on post‐translational protein modifications (cleavage/phosphorylation). Gulmann et al. used laser capture microdissection and RPMA to profile frozen lymphoid tissue from patients diagnosed with follicular lymphoma or follicular hyperplasia to define pathways of cancer complementary to genomic information (Gulmann et al., 2005). Ratios of apoptosis related proteins (Bcl‐2/Bak) were able to discriminate lymphoma from hyperplasia. Panels of biomarkers, or ratios of proteins, may be the diagnostic and prognostic indicators of the future. As new molecular targeted agents are developed, such as anti‐sense Bcl‐2 (Oblimersen) (Herbst and Frankel, 2004), it will be imperative to validate the state of drug targets, pre‐ and post‐treatment, that may signify clinically relevant protein signatures of hematologic malignancies (Gulmann et al., 2005; Kornblau et al., 2010; Zha et al., 2004).

3. Pharmaceutical discovery applications

The NIH Biomarker Working Group defined a biomarker as “a characteristic that is objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biological or pathological processes or pharmacological responses to a therapeutic intervention” (Atkinson et al., 2001). RPMA lend themselves to pre‐clinical drug target validation due to the quantitative readout of cell signaling proteins that represents the “pharmacological response to a therapeutic intervention”. Although novel drugs, antibody‐based therapeutics, or small molecule inhibitors are well characterized prior to Phase 1 clinical trials, unexpected in vivo on‐target and/or off‐target effects often occur due to promiscuous ligand binding within domain families (Castagnoli et al., 2004). Even though specific kinase inhibitors, such as imatinib, have achieved great success in inducing tumor remission, oncologists are still plagued by the development of drug resistance (Krishnamurty and Maly, 2007, 2010). Activating mutations within the ATP‐binding pocket of EGFR in NSCLC (Kobayashi et al., 2005), or BCR‐ABL mutations which hinder drug binding (Azam et al., 2003) but do not effect the catalytic activity, may cause unexpected tumor growth. One of the areas in which RPMA data may be used to guide therapy is predicting which receptors are active, even if the mutation status is unknown. In a study of microdissected NSCLC samples, with known EGFR mutation, VanMeter et al. showed that ratios of specific phosphorylated EGFR residues, or ratios of phosphorylated forms to total EGFR, were associated with EGFR L858R activating mutations suggesting that phoshpproteomic data could be used as surrogate indicators of genetic mutations (VanMeter et al., 2008). RPMA proteome profiling utilizing cell culture lysates or surrogate cell populations provides a) pre‐clinical validation of drug targets (Sikora et al., 2010), b) identification of off‐target effects (Sevecka and MacBeath, 2006), and c) candidate biomarkers of drug sensitivity (Havaleshko et al., 2009).

Pre‐clinical validation of biomarkers as potential drug targets can drastically reduce time and money required for clinical trial validation of new compounds. Proteins often have pro‐tumor and anti‐tumor effects depending on the context of the tumor microenvironment and presence of stimulatory or inhibitory ligands. One such system is nitric oxide signaling in response to inflammation or hypoxia. Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) inhibition, by a small molecule antagonist (L‐nil) in a NOD/SCID xenograft model, showed tumor suppression (Sikora et al., 2010). Potential mechanisms of action for tumor suppression were highlighted by RPMA analysis, suggesting that iNOS inhibition affected the post‐translational stability of Bcl‐2, an anti‐apoptotic protein, resulting in decreased expression of Bcl‐2 (Sikora et al., 2010).

Three examples in which RPMA are revealing insights into drug target effects are summarized below. Using RPMA to understand how information flows through protein signaling networks, in addition to detecting potential interventional nodes, can reveal non‐intuitive, potential drug targets. High‐throughput, microtiter plate format RPMA are described by Sevecka and MacBeath as a strategy to screen small molecule kinase and phosphatase inhibitors to develop ErbB signaling network maps based on cell signaling changes induced by the compound (Sevecka and MacBeath, 2006). Using an A431 cell line and the EGFR pathway as a model signaling system, they screened a commercially available kinase and phosphatase library for protein activation and attenuation. Clustering algorithms, based on a weighted Euclidean distance as the similarity metric, were designed to visualize protein networks (Sevecka and MacBeath, 2006). In addition, their system was shown to be applicable for generating high‐throughput dose‐response curves for multiple compounds and proteins.

Telomere 3′ overhang specific DNA oligonucleotides (T‐oligos) induce autophagy rather than apoptosis through a proposed mechanism in which the T‐oligo mimicks the telomere loop disruption that is often caused by DNA damage (Aoki et al., 2007; Yokoyama et al., 2007). T‐oligos were found to inhibit mTOR and STAT3 in a malignant glioma cell model, suggesting T‐oligos as a potential therapeutic agent (Aoki et al., 2007; Yokoyama et al., 2007). This study emphasizes the specific drug target information content provided by the reverse phase protein microarray technology.

Anti‐tumor mechanisms of the gastrin‐releasing peptide receptor antagonist (PD176252) in combination with erlotinib in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell lines were investigated by Zhang et al. using RPMA (Zhang et al., 2007). Phosphoprotein profiling showed decreased expression of phospho c‐jun, phospho p70S6K, and phospho p38 in the mucosal epithelial cell model suggesting that the combination treatment targets multiple nodes within proliferation/survival pathway networks.

4. Validation of mass spectrometry discovered candidate biomarkers by RPMA

Validation of candidate biomarkers discovered by mass spectrometry (MS) must use independent sample sets, separate from those used for discovery. A typical mass spectrophotometric workflow for phosphoprotein detection is presented by Harsha and Pandey in this issue (see “Phosphoproteomics in Cancer”). Technologies for protein biomarker validation fall into three categories depending on antibody sourcing:

RPMA. If only a single validated antibody exists for the biomarker, then Reverse Phase Protein Microarrays can be used to validate mass spectrometry derived biomarker candidate proteins (VanMeter et al., 2008). For adequately validated antibodies, RPMA has a sensitivity in the picogram per mL with clinical grade precision (Paweletz et al., 2001, 2001, 2006, 2008).

Low molecular weight (LMW) serum protein fractions are likely to contain proteins and peptides that have been shed from the diseased tissue (Liotta et al., 2003, 2003, 2005, 2005). Serum‐based biomarkers are attractive as drug targets and for screening because serum is often more readily available and easier to collect compared to tissue. Mueller et al. used Liquid Chromatography‐MS/MS to identify candidate protein biomarkers in LMW serum fractions from a community‐based cohort of patients with minimal cognitive impairment before and after cognitive decline to Alzheimer's Disease (Mueller et al., 2010). Based upon their mass spectrometry analysis, Biliverdin reductase B (BLVRB) and S100A7, in addition to proteins in the heme degradation pathway, were selected for verification by RPMA. Super Oxide Dismutase, MMP‐9, PDGFR Tyr716, Estrogen Receptor α (ERA), Biliverdin reductase A (BLVRA) and HemeOxygenase1 were analyzed by RPMA for correlations with protein abundance. No statistical differences were found for individual protein abundances, but non‐parametric analysis revealed six protein abundance ratios that were elevated after cognitive decline compared to the stable, minimal cognitively impaired group: BLVRB/BLVRA, Estrogen Receptor α/BLVRA, HemeOxygenase1/BLVRA, MMP‐9/BLVRA, PDGFR Tyr716/BLVRA and S100A7/BLVRA (Mueller et al., 2010).

Sandwich ELISA. If an antibody sandwich pair exists then a clinical grade ELISA or bead assay can be used for validation.

Multiple Reaction Ion Monitoring (MRM). If no antibodies exist for the candidate antigen then Multiple Reaction Ion Monitoring (MRM) mass spectrometry (Yang and Lazar, 2009; Yocum and Chinnaiyan, 2009) can be attempted to detect a specific peptide fragment of the analyte. MRM technology does not require a specific antibody, but antibody capture can be used to enrich the antigen concentration introduced into the MRM instrument.

Validation of MS discovered biomarkers from tissue or body fluids must be done with the following analytical principles in mind:

The sensitivity of MS for biomarker discovery is low (Bell et al., 2009) – in the range of 50–500 ng/mL, depending on the platform and the sample preparation method. The HUPO plasma proteome project has yielded mainly high abundance proteins (Schenk et al., 2008). Most clinically relevant disease biomarkers fall in the range of 0.1–10 ng/mL, below the level of MS detection. Thus a biomarker considered by MS to be negative, or absent, actually may be present in the sample at a concentration below the level of MS sensitivity (Longo et al., 2009). A sensitive technology such as RPMA or ELISA may therefore detect a candidate biomarker in a control sample considered to be negative by MS. The MS result should not be considered a false negative.

The epitope identified by MS may not be recognized by the antibody used for validation. The MS spectrum of a candidate protein may be only a small segment of an antigen sequence associated with a fragment flanked by trypsin cleavage sites. The MS identified trypsin fragment may be derived from a fragment or isoform of the antigen that is not present in the non‐trypsinized sample or is not recognized by the antibody used for validation. While the use of a polyclonal antibody has a greater probability of recognizing the correct MS identified epitope on the antigen, polyclonal antibodies have a greater probability of cross‐reactivity with the other antigens.

MRM currently has a low sensitivity of detection. The sensitivity has been reported to be 50 ng/mL or greater when the input sample is plasma or serum (Yocum and Chinnaiyan, 2009). Moreover the sensitivity of the MRM may not match the sensitivity of the original MS platform used for discovery of the candidate antigen. Thus the use of MRM for validation of candidate biomarkers discovered by MS may generate false negatives. If the suspected concentration of the true biomarker is below the detection limit of MRM then it is advisable to generate an antibody to a synthetic peptide representing the original trypsin fragment domain. The antibody can then be used to enrich the input to the MRM (Whiteaker et al., 2007), or can be employed in the RPMA for definitive validation.

4.1. Validation study design depends on the intended use

The final, and most critical stage of research clinical validation is blinded testing of the biomarker panel using independent (not used in discovery), large clinical study sets that are ideally drawn from at least three geographically separate locations. The required size of these test sets for adequate statistical power depends on both the performance of the analyte panel in the platform validation phase and the intended use of the analyte in the clinic. For example, markers for general population screening require more patients than those for high‐risk screening, which in turn require more patients than markers for recurrence/therapeutic monitoring. Employing previously verified controls and calibrators, under standard clinical chemistry guidelines for immunoassays (Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute approved guidelines, www.clsi.org), the sensitivity and specificity can be determined for the representative test population. It is important to emphasize that sensitivity and specificity in an experimental test population does not translate to the positive predictive value that would be seen if the putative test was used routinely in the clinic (Hodgson et al., 2009). The true positive predictive value is a function of the indicated use and the prevalence of the cancer (or other disease condition within the target population). For example, the percentage of expected cancer cases in a population of patients at high genetic risk for cancer is higher than the general population. Consequently, the probability of false‐positive results in the latter population would be much higher. For this reason the ultimate adoption of a protein biomarker‐based test will be strongly dependent on the clinical context of its use (Hodgson et al., 2009).

5. Diverse applications of reverse phase protein microarrays

Numerous creative studies have successfully employed RPMA for addressing protein signaling in cancer as well as infectious disease. Selected examples of basic research studies include deciphering protein interactions and quantitative effects of RNAi in a breast tumor cell line model (Sahin et al., 2007), examining the molecular effects of anthrax infection in lung cells (Popova et al., 2009), elucidating antibody profiles after Plasmodium infection (Doolan et al., 2008), assessing tumor–stroma interactions (Iyengar et al., 2005), validating clusterin as a blood biomarker of carcinogenesis (Aguilar‐Mahecha et al., 2009), identifying IGFBP2 as a candidate biomarker and therapeutic target of glioblastoma (Moore et al., 2009), evaluating protein expression in Drosophila models of metastasis (Woodhouse et al., 2003), deciphering cardiac glycoside suppression of IL‐8 in a cystic fibrosis model (Srivastava et al., 2004), characterizing prosurvival pathways in cancer stem‐like cells from breast MCF7 cell lines (Zhou et al., 2007), and profiling thiol oxidation in tumor cells (Seo and Carroll, 2009).

5.1. RPMA provide mechanistic insights of tyrosine kinase receptor pathways

Complimentary studies by Machida et al. (2007) and Jones et al. (2006) generated quantitative Src homology 2 (SH2) binding profiles and equilibrium dissociation constants of ErbB1 SH2 binding domains. The SH2 binding domain, an integral signaling moiety in tyrosine kinase receptors such as ErbB2 (EGFR), regulate binding and dissociation of downstream effector molecules such as Src kinases (Gonfloni et al., 1997, 2000). Global interactive profiling provides in‐depth insights into the mechanisms of tyrosine kinase signaling pathways.

5.2. Pre‐printed reverse phase protein microarrays

Commercially available, pre‐printed reverse phase protein microarrays provide a means of screening multiple tissues for protein–protein interactions, post‐translational modifications (phosphorylation, glycosylation, acetylation, etc.), biochemical pathway activity, or specific protein target binding (SomaPlex™ (Protein Biotechnologies), ProtoArray® (Invitrogen), ProteoScan (Origene)). High quality tissue and well‐annotated clinical data, including information regarding elapsed time from collection to preservation, are essential for interpreting any RPMA, whether it is commercially produced or an in‐house custom array.

6. RPMA technology tutorial

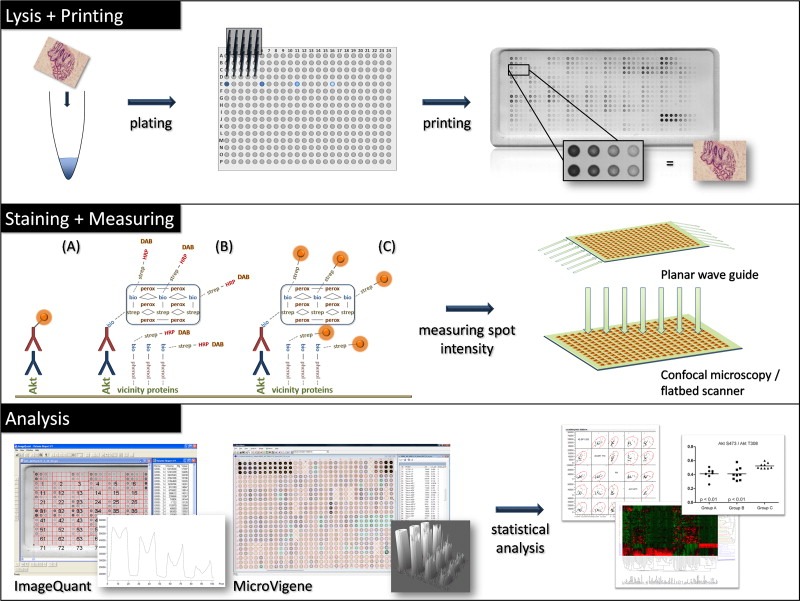

The purpose of this review has been to show how RPMA have graduated from basic research tools to clinical research trials. For readers interested in improving the technology or adopting this technology, we provide details for sample preparation, array printing, protein detection and staining, as well as spot analysis (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Reverse phase protein microarray technology summary. Lysis and Printing: reverse phase protein microarrays are constructed by preparing samples in a microtiter plate prior to deposition on a series of identical nitrocellulose coated slides by a robotic arrayer. Each sample is printed in a dilution series, shown here as a series of four 2‐fold dilutions. Each spot represents the protein composition of the sample at the time of stabilization after sample procurement. Each individual array represents a self‐contained assay because it includes controls, calibrators and samples on the same array. Staining and Measuring: a single array slide is stained with one antibody that has been previously validated and shown to be specific for the protein of interest. Detection chemistries can be fluorescent, chemiluminescent, or chromogenic. Spot intensity is analyzed by a suitable platform based on the detection chemistry. Examples of fluorescent spot analysis include planar waveguide imaging and confocal laser scanning. Chromogenic spot analysis is performed with a high‐resolution flatbed scanner. Analysis: spot finding software programs convert pixel density for each spot into numerical values. Histograms of spot morphology can also be reviewed. The quantitative pixel intensity can be further normalized and applied to statistical or bioinformatics analysis.

6.1. Array formats: forward phase and sandwich arrays

A distinction has been made in the literature regarding the three classes of protein microarrays: a) antibody arrays also known as forward phase arrays, b) sandwich arrays, and c) reverse phase protein microarrays (Figure 2). Forward phase (antibody) arrays are constructed from multiple bait molecules (antibodies, nucleic acids or lipids) immobilized on each array and probed simultaneously with one complex, biological mixture containing a multitude of different proteins. Cellular lysates or serum samples are common probes and the analyte of interest is directly labeled, typically with a fluorescent molecule (Kusnezow et al., 2006). The forward phase array permits the simultaneous analysis of multiple analytes present in one sample. The sandwich array, in contrast, employs a two‐antibody system for binding and detecting the protein of interest. One antibody is required to bind the analyte of interest to the substratum and a second antibody binds a different epitope on the same molecule, which functions as a detection molecule (Templin et al., 2002; Zhu and Snyder, 2003). The current state‐of‐the‐art for oncoproteomic profiling with forward phase arrays is reviewed by Alhamdani et al. (2009).

6.1.1. Reverse phase microarray format

RPMA address the analytical challenges of sandwich and forward phase arrays. Antibody arrays are particularly not well suited for tissue‐based analysis in which the input cell number is in the hundreds to thousands. Since the reverse phase array maintains the concentration of the input sample, the sensitivity is greater compared to an antibody array probed with the same small number of input cells. Reverse phase protein microarrays are constructed by printing serial dilutions of each sample, control or standard, which maintains input sample concentration, as well as effectively matching the primary antibody affinity with the sample concentration for numerous different samples on each array. Each spot within an RPMA contains an immobilized sample (bait) zone measuring only a few hundred microns in diameter thus maximizing precision and lowering the limit of detection compared to traditional dot blots (Ekins and Edwards, 1997, 1989, 2001, 2001).

6.2. Samples

Types of samples commonly immobilized on the microarray are: a) denatured cellular lysates from laser capture microdissected material (Silvestri et al., 2010), b) serum (Janzi et al., 2005, 2009), c) body fluids such as ovarian effusions (Davidson et al., 2006), or vitreous (Davuluri et al., 2009), d) cell culture lysates (Hong et al., 2010; Nishizuka et al., 2003), e) low molecular weight serum protein fractions (Mueller et al., 2010), f) peptides (MacBeath and Schreiber, 2000), or g) Fine Needle Aspirates (Rapkiewicz et al., 2007). Tissue samples can be fresh, frozen, or fixed (ethanol or formalin fixed paraffin‐embedded), effectively expanding RPMA for retrospective or prospective proteomic analysis (Becker et al., 2007; Menard et al., 2005). Selection of lysis conditions, buffers, and antibodies should be selected based on the nature of the protein, i.e. native or denatured (Winters et al., 2007). Gromov et al. effectively applied a commercially available (Cell Lysis Buffer 1, Zeptosens) tissue lysis solution to multiple proteomic platforms, including 2D gel electrophoresis, western blotting, RPMA, and antibody arrays (Gromov et al., 2008). Incorporation of a single lysis solution allows comparison across multiple platforms from a single, small volume sample.

6.3. Substratum

The substratum requirements for protein microarrays are 1) high‐binding capacity, 2) retention of protein structure, 3) low background, and 4) ability to provide compact, uniform spot morphology. Substrates as diverse as gold coated glass or nylon (Arrayit® Corp.) (Grainger et al., 2007; Olle et al., 2005), functionalized glass (El Khoury et al., 2010; Seurynck‐Servoss et al., 2007), hydrogel (Bally et al., 2010; Guilleaume et al., 2005; Miller et al., 2003), PVDF (Dalessio and Ashley, 1992; LeGendre, 1990), macroporous silicon (Ressine et al., 2007), and nitrocellulose polymers (Stillman and Tonkinson, 2000; Tonkinson and Stillman, 2002) meet these criteria but nitrocellulose coated glass has, to date, been the most commonly used substratum (available from vendors including Arrayit® Corp. (SuperNitro coating), GE Healthcare (FAST® slide), Grace Bio‐Labs (ONCYTE® Avid™ or Nova™ film slides), or Schott AG (Nexterion® C or NC slides). Nitrocellulose polymer coatings permit protein‐binding capacities of 75–150 μg/cm2 in a volume of 0.3–2 nL/spot (Stillman and Tonkinson, 2000; Tonkinson and Stillman, 2002).

Commercially available systems, which include proprietary substratum, imaging and analysis software, provide a single source vendor for RPMA construction and analysis. Zeptosens technology (ZeptoCHIP) uses a substratum consisting of a planar waveguide, composed of glass on which a diffraction grating has been etched and coated with thin, high refractive index film. The planar waveguide allows laser light to propagate within the film, creating an evanescent wave (Figure 4). Fluorescence excitation of the fluorophores is restricted to the surface, providing high signal:noise ratios compared to confocal fluorescent scanning (Pawlak et al., 2002; van Oostrum et al., 2008; Voshol et al., 2009).

6.4. Arraying devices

Protein microarrays are printed using the same technology as DNA microarrays, using either contact (Loebke et al., 2008) or non‐contact devices (Schena, 2000). Microarray printing needs to be reproducible, high capacity, and automated for high‐throughput testing. The pinhead, and type of printing assembly, is key to successful protein array printing. Sample volume, viscosity, number of arrays required, and substratum are parameters to be considered prior to selecting a printing system.

6.5. Detection strategies

Protein microarray technology is not as straightforward as DNA‐based microarrays due to the complex structure of proteins and the variety of post‐translational modifications. Molecular variability, coupled with the wide dynamic range of protein concentrations found in any complex biological sample, presents particular challenges for detection strategies (Celis and Gromov, 2003, 2007, 2008, 2008, 2009). Critical aspects of protein array technology discussed in detail below are a) availability of validated antibodies to the protein of interest, b) robust signal amplification methods, and c) sensitive detection systems.

6.5.1. Antibody affinity and sample concentration

Principles of immunoassay measurement (Ekins and Edwards, 1997, 1998, 1989) may more aptly apply to RPMA. As such, effects of spot size to analyte ratio (miniaturization), protein concentration per spot, amplification chemistries, and antibody affinity play a role in the accuracy, precision, and limit of detection. Each antibody–ligand interaction has its own unique affinity constants (association and dissociation rates) that must be determined empirically. The affinity constants constrain the linear range of the assay. The linear detection range can only be attained if the concentration of the analyte and antibody/ligand is properly matched to the affinity. The analyte concentration in many situations is, by definition, unknown, and may be the experimental goal. Multiplexed formats containing multiple antibodies with varying affinities will not be able to achieve linearity for all analytes in each spot (Liotta et al., 2003, 2003).

Reverse Phase Protein Microarrays circumvent issues of prior determination of affinity constants and protein concentration by 1) immobilizing the sample lysate in a dilution curve, and 2) probing multiple samples on one array with only one primary antibody. In this format, each sample dilution curve ensures that antibody affinity and protein concentration can be matched for each individual sample because each sample dilution acts as a mini‐affinity constant experiment.

Detection hinges on the availability of antibodies that have been proven by experimental means to be specific for the protein of interest. Each batch or lot number of antibody could have a different affinity and specificity. Thus, validation of antibody specificity and sensitivity, prior to use as a probe for protein microarrays, is of utmost importance for ensuring accurate protein detection (Bjorling and Uhlen, 2008, 2003, 2003, 2006, 2002). Validation is generally performed by western blotting using complex biological samples similar to those used on the RPMA (Bjorling and Uhlen, 2008). Peptides, rather than native proteins, are often used as immunogens in antibody production. Peptide derived antibodies may not bind to proteins in the native state, limiting the ability to detect protein–protein interactions or native, full‐length proteins.

6.5.2. Chromogenic detection

Based solely on competitive immunoassay mass action kinetics, one would surmise that an assay in which the capture molecule concentration is limitless would be the most sensitive (Ekins and Edwards, 1997, 1998, 1989), but the binding capacity of the substratum can dramatically effect the concentration of the antigen and thus change the concentration of the capture molecule. Comparisons of array platform detection limits must take into consideration the optimal substratum for each platform (Jaras et al., 2007). In general, amplification techniques with stringent amplification chemistries are used for chromogenic detection (Bobrow et al., 1989, 1991, 1996, 1997) and fluorescent detection of proteins in a nitrocellulose based RPMA format.

Detection methods developed for protein microarrays generally depend on a) the expected analyte concentration, b) type of microarray imaging system, and c) type of sample. Detection methods can be direct or indirect. Direct methods employ a labeled capture molecule, which is either the protein of interest or a second, labeled antibody (Jaras et al., 2007; Loebke et al., 2007), while indirect methods (Paweletz et al., 2001, 2001) utilize an amplification step to enhance the signal:noise ratio. Chromogenic detection via horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and alkaline phosphatase (AP) act on a variety of colorless chemical substrates, each generating a different colored product producing permanent signals that are easily visualized for analysis (Espina et al., 2004). Diaminobenzidine (DAB) is a commonly used chromogen (Paweletz et al., 2001, 2001, 2006, 2008).

6.5.3. Fluorescence detection

Not all substrata are compatible with fluorescence detection strategies due to inherent auto‐fluorescence of the material (Tonkinson and Stillman, 2002). Fluorophore selection depends on sample type, substratum, and emission characteristics. Cy3 and Cy5 dyes are commonly used for fluorescent detection due to their decreased dye interactions, increased brightness and the ability to add charged groups to the dyes (e.g. streptavidin) (Pawley, 1995). Large dynamic ranges are the hallmark of fluorescent detection systems. Therefore fluorescence is well suited for microarrays in which the spots have a total protein content of 1.0 mg/mL or greater, or the arrays are comprised of samples with varying amounts of total protein. Photo bleaching and quenching is a disadvantage of fluorescent detection strategies and may cause false decreases in the total signal observed on a microarray.

Despite these issues, Dupuy et al. have developed a near‐infra red detection system combined with tyramide signal amplification. Reported lower limits of detection were less than 1 amol with two rounds of amplification indicating that RPMA possess adequate sensitivity to detect antigens from a very limited total protein content input (Dupuy et al., 2009). A commercially available array system (Zeptosens) offers fluorescence‐based detection without further amplification steps (Pawlak et al., 2002; Pirnia et al., 2009; van Oostrum et al., 2008)

6.5.4. Total protein detection

In addition to using antibodies to detect specific proteins of interest, it is also useful to measure the total protein content per microarray spot. The total protein content per spot may vary across spots due to differences in protein concentration between samples, sample evaporation during the printing process, or differences in protein content across a dilution series. Total protein content per spot is often used to normalize signal intensities between spots. Total protein staining can be either fluorometric (Sypro Ruby (Invitrogen)) (Berggren et al., 2002), Fast Green FCF (Loebke et al., 2007), or Deep Purple (GE Healthcare)) (Mackintosh et al., 2003), or colorimetric (colloidal gold (AuroDye™, GE Healthcare)) (Switzer et al., 1979). The dye choice is dependent on a) expected protein content per spot/sensitivity of the stain, b) substratum, and b) detection instrumentation. Colloidal gold produces a permanent photostable pink/red spot. AuroDye™ Forte's sensitivity is comparable to silver staining (0.3–10 ng/mL on a gel (Switzer et al., 1979)). AuroDye™ Forte is compatible with nitrocellulose and PVDF (polyvinyl difluoride) membranes, but not with nylon. Deep Purple is a naturally occurring fluorescent compound, epicocconone, derived from the Fungus Epicoccum nigrum (Mackintosh et al., 2003). Deep Purple is a reversible stain that binds histidine, arginine and lysine residues. It has an excitation peak of 520 nm and emission peak of 600 nm. Deep Purple images can be acquired with a UV transilluminator or fluorescent scanner with a sensitivity of 0.25–1.0 ng/mm2 protein. Sypro Ruby staining is a permanent fluorescent protein stain, with an excitation wavelength of 280 and emission wavelengths of 450 nm/618 nm. The stain is composed of a heavy metal ruthenium complex. The stain is photostable, allowing long emission lifetime and the ability to measure fluorescence over a longer time frame, minimizing background fluorescence (Berggren et al., 2002). Sypro Ruby stain can detect 0.25–1.0 ng/mm2 of protein on a 1‐D gel.

6.6. Spot analysis and bioinformatics

Although RPMA may be viewed by some as microarray technology analogous to DNA microarrays, protein microarrays are technically in a distinct class due to signal variability across the array (Sboner et al., 2009). DNA microarrays are assumed to have nearly identical mRNA levels across all samples, whereas protein microarrays can have markedly different total protein and analyte protein concentrations across different samples (Sboner et al., 2009). The absolute concentration of a protein will affect the overall signal:noise ratio and the limit of detection. Spatial effects may be a cause of poor reproducibility on arrays. Acceptable reproducibility due to spatial effects can be achieved by simply increasing the number of local control spots used to normalize values (Anderson et al., 2009), but this process results in a diminished area for printing sample spots.

Various algorithms and software packages are currently available for RPMA spot detection and analysis including PCSAN (Carlisle et al., 2000), ImageQuant (Petricoin et al., 2007), MicroVigene (Wulfkuhle et al., 2008), GenePix ((Sevecka and MacBeath, 2006), ZeptoVIEW 3 (van Oostrum et al., 2008; Voshol et al., 2009) and Gentel AthenaQuant™. Normalization algorithms include Robust‐Linear‐Model normalization (Sboner et al., 2009), calibration curve normalization (Sevecka and MacBeath, 2006), reference standard normalization (Sheehan et al., 2005), and “spike‐in” internal standard normalization (Korf et al., 2008; Loebke et al., 2008).

7. Limitations

7.1. Antibody specificity and availability

Gene transcript profiling was catalyzed by the ease and throughput of manufacturing probes with known, specific and predictable affinity constants. In contrast, the probes (e.g. antibodies, aptamers, ligands, drugs) for protein microarrays cannot be directly manufactured with predictable affinity and specificity. The availability of high quality, specific antibodies or suitable protein‐binding ligands is the limiting factor, and starting point, for successful utilization of protein microarray technology (Liotta et al., 2003, 2003, 2002).

The degree of post‐translational modifications or protein–protein interactions, for an individual analyte protein, will contain critical biologic meaning that cannot be ascertained by measuring the total concentration of the analyte. Thus a significant challenge for protein microarrays is the requirement for antibodies, or similar detection probes, that are specific for the modification or activation state of the target protein. Sets of high quality modification state‐specific antibodies are commercially available, however they only represent a small percentage of the known proteins involved in signal networks and gene regulation. A significant challenge for cooperative groups, funding agencies, and international consortia, is the generation of large comprehensive libraries of fully characterized specific antibodies, ligands and probes. Both government and private entities are addressing this issue by publishing databases of antibody specificity and epitope characterization such as AntibodypediaA (http://www.antibodypedia.org/) which was developed as a Human Proteome Organization (HUPO) Antibody Initiative and the European Union ProteomeBinders (Bjorling and Uhlen, 2008). AntibodypediaA provides a comprehensive listing of antibody validation criteria (supportive, not supportive or uncertain) based on immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence, western blotting, and protein array data. Other antibody validation consortia include Alliance for Cellular Signaling (AfCS Antibody Database) (http://www.signaling‐gateway.org/data/antibody/cgi‐bin/targets.cgi); PhosphoSite® (http://www.phosphosite.org); and Antibody Epitope/Registry Database (http://phm.utoronto.ca/∼jeffh/AERD.htm).

7.2. Sample degradation and preservation

Although it is now possible to extract proteins from formalin fixed tissue (Becker et al., 2007), formalin penetrates tissue at a variable rate, reported within the range of mm/h (Fox et al., 1985; Helander, 1994; Srinivasan et al., 2002). Portions of the living tissue deeper than several mm would be expected to undergo significant fluctuations in phosphoprotein analytes. A typical 16‐gauge core needle biopsy is 7 mm × 1.6 mm (volume = 17.9 mm3). Even in a relatively small core needle biopsy, it is clear that proteins and nucleic acids in the depth of the tissue will have significantly degraded by the time formalin permeates the tissue (Fox et al., 1985; Nassiri et al., 2008). An important long‐term need for the clinical implementation of phosphoprotein biomarkers will be the design of stabilizers for the preservation of post‐translational modified proteins without the need for freezing. Ideally, the stabilizing chemistry should arrest both kinases/phosphatases, in order to prevent positive or negative fluctuations in phosphorylation events as the living excised tissue reacts to the ex vivo conditions. Fidelity of any proteomic analysis will be enhanced if tissue samples are stabilized as soon as possible after excision. 20 min from excision to preservation have been informally adopted as a maximum time interval for stabilizing tissue (e.g. flash freezing, thermal denaturizing, or chemical stabilization) (Espina et al., 2009). Preservation of tissue histology and morphology is essential for verification of tissue type and cellular content. Sample excision/collection time, elapsed time to preservation/stabilization, and length of fixation time are critical data elements for assessing sample quality.

8. Conclusions and vision for the future

RPMA technology was developed to fill a critical missing component of molecular profiling: quantitative measurement of signal pathway proteins, and their post‐translationally modified forms. Measuring this class of analytes, which contains the targets of molecular inhibitors, provides information about the disease state of cells that could not be obtained by genetics or genomics. The need to measure this class of protein analytes from small biopsy samples will continue and expand into the future. The trend is neoadjuvant therapy selected on diagnosis made by fine needle biopsies or aspirates. Every month new signal pathway analytes are validated and more antibodies are commercialized. Consequently the sample size will continue to shrink and the complexity of the analyte repertoire will expand. Therefore, the future will bring greater demands on the sensitivity, precision and versatility of RPMA technology. RPMA technology will evolve to utilize nanotechnology, 3rd generation amplification technologies, and new antigen recognition technology, so that the ultimate clinical embodiment is a one‐step technology from the user's perspective. We can imagine a time in which readout is fully electronic and does not go through an array image capture step. It may even be possible to achieve a multiplex assay with high sensitivity in a homogenous (solution phase) format.

The utility of RPMA technology for individualizing therapy lies in signal pathway profiling. The knowledge we gain from the ongoing clinical research trials will shape how signal pathway profiling will be done in the routine clinical practice of the future. The ongoing clinical trials may reveal unexpected endpoints and pathways that correlate, or do not correlate, with outcome. We may find that activated proteins we expect to increase, may do the opposite following therapy, and this may be the best predictor of resistance or efficacy. We will surely find previously unknown interconnections between nodes in a network that lead to new combination therapeutic strategies. Measuring the strength of protein–protein interactions (Interaction‐omics) to map signaling network pathways that were previously unknown to be inter‐connected will be an important advancement in RPMA technology. Moreover it is likely that networks of signal proteins are inter‐connected differently from one patient to the next.