Abstract

The kidneys perform a wide array of functions in the body, most of which are essential for life. Regulation of water and electrolytes, excretion of metabolic waste and of bioactive substances like hormones, drugs etc., which affect bodily functions; regulation of arterial blood pressure, red blood cell and vitamin D production; are some of the major functions that the kidneys perform. It is obvious then, that patients with renal failure present a steep challenge to the physician taking care of this special population. Renal replacement therapy remains only a part of treatment that helps substitute the regulation of water and electrolytes, removal of metabolic waste, and to a certain extent removal of drugs and other bioactive substances from the body. This article aims to provide an understanding of different types of renal replacement therapy, mainly to patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD).

Introduction

According to the USRDS data, in 2007, the incident and prevalence rate of ESRD dialysis patients in the U.S. was 354 per million and 1,163 per million respectively. Diabetes and hypertension remain the two most common causes of patients reaching ESRD. In the U.S., the annual cost of providing dialysis is estimated to be approximately $ 24 billion, accounting for about 6 % of the total Medicare spending. The projected incident and prevalent ESRD patients in 2020 would be 142,858 and 774,376 patients respectively. It is clear from these statistics that ESRD patients are and will continue to be an important subset of population that an internist would be caring for.

Approach to Renal Replacement Therapy (RRT)

To achieve greatest good from the limited resources, some suggest that sick patients with multiple co-morbidities, who are unlikely to survive more than few months should not be offered dialysis.1 This appears contrary to clinical studies2, 3 that showed inability to predict the likelihood of mortality by statistical models and clinical judgment of the perceived ‘high-risk’ patients. And hence, clinicians should resist any imposition of rationing criteria on dialysis provision; especially in an ever increasing elderly population.1 Now, it is the standard of practice to offer RRT to all patients in ESRD, even those whose prognosis is uncertain. A trial of dialysis is suggested for those who are uncertain of dialysis benefits, thus providing patients and their family a better understanding of dialysis process involved. Choice of a RRT modality is made by the patient after a comprehensive education regard to pros and cons of each options. Nevertheless, patient’s decision is respected in all instances, as long as no medical contraindications exist.

When to Initiate Dialysis?

The National Kidney Foundation Dialysis Outcome Quality Initiative Clinical Practice Guidelines recommends that RRT should be initiated when patient’s weekly renal Kt/V is less than 2 and/or patients with uremic symptoms. As a standard of practice, non-diabetic patients with estimated GFR less than 10 ml/min and diabetic patients (due to poor uremic-symptom tolerance) with an e-GFR of less than 15 ml/min are considered eligible to initiate RRT. Some advocate dialysis initiation on approaching these e-GFR indications, even without uremic symptoms, so called a “healthy start”, with the intention to prevent or minimize crippling uremic complications. When uremic complications do occur, some are irreversible, and others take long time to reverse. However, a recently reported, Initiating Dialysis Early and Late (IDEAL) study of 828 patients concluded that early start hemodialysis has no survival advantage, and the traditional approach of initiating dialysis in symptomatic patients with low e-GFR should be continued.4

Renal Replacement Therapy Options

Allograft renal transplantation is the most preferred form of renal replacement therapy (RRT), which has been described in the other sections of the Journal. Due to organ (deceased kidneys and live donor) scarcity, only about 16,000 transplant surgeries are performed annually in the U.S., while over 100,000 patients are wait-listed to receive kidneys. Many elderly and those with multi-organ damages are generally excluded from the transplantation due to associated high risk of surgery and post surgery immunosuppression. Therefore, those who are ineligible or choose not to receive a kidney or those needing dialysis while waiting for a kidney are maintained on chronic dialysis, either hemodialysis (HD) or peritoneal dialysis (PD). During dialysis, the toxic metabolic waste products from the blood compartment are removed when the blood is run across a semi-permeable membrane (artificial or natural), resulting in ‘clearance of blood’ of the toxic metabolic waste. In the U.S., large majority of patients are on HD, approximately 86% as opposed to only 14% on peritoneal dialysis (PD)5. The overwhelming preference of HD over PD is an enigma and is a subject of intense discussion among the leadership in the community. The subject is a complex issue and is multi-factorial. Although there is no survival advantage with either of the dialysis therapy over four to five years, several non-medical factors, like economics of dialysis, lack of well trained dialysis team and psychological factors have been implicated5 in the biased preference of one form of dialysis over the other. Ideally, the choice of a dialysis modality should be made by the patient after a comprehensive education regard to pros and cons of each options. A dialysis facility should have the provision to provide all possible modes of dialysis.

Basic Principles of Dialysis

Diffusive removal (first described by Thomas Graham in 1861) across a semi-permeable membrane is the result of random Brownian movement of solutes and is dependent on several variables derived from Fick’s law. HD works on the principle of diffusion.

Solutes (metabolic wastes) are classified mainly into three categories – small molecule (<500 Daltons), middle molecules (500–1500 Daltons), and large molecules (>1500 Daltons). Small molecules are removed by diffusion, and middle molecules by diffusion and convection (fluid removal without any change in concentration of solutes). Larger solutes are primarily cleared by convection, which occurs when ultra-filtration (UF) is performed. Although blood urea (a small molecule) was the first ‘uremic toxin’ to be identified in patients with renal failure; over the years, an increasing number of substances (middle molecules and large molecules) have been identified as uremic toxins6, 7 and are implicated in the pathogenesis of uremic syndrome. The importance of larger molecules in causing dialysis morbidity and mortality is being increasingly recognized.

Hemodialysis

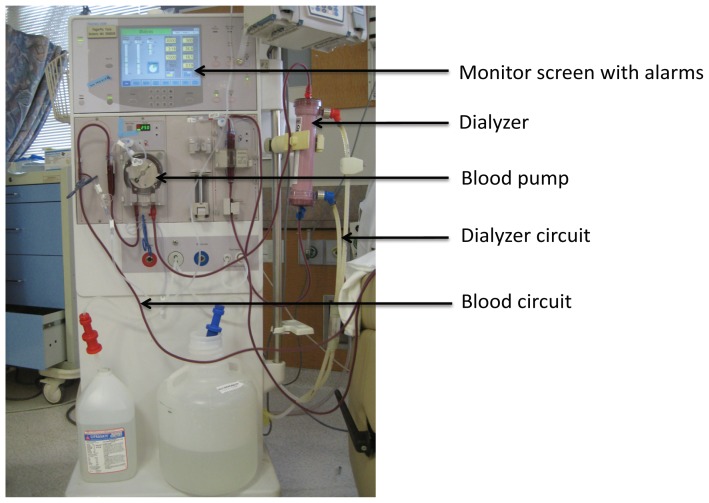

The hemodialysis (HD) apparatus consists of HD machine, the blood circuit, the dialysis solution circuit and the dialyzer (See Figure 1). The HD machine consists of blood pump, dialysate delivery system and safety monitors, which are becoming increasingly sophisticated. A dialyzer consists of rigid polyurethane cartridge containing dialysis membranes (hollow fibers or parallel sheets). The dialysis membrane can be made of cellulose, modified cellulose or synthetic material. Synthetic membranes elicit least inflammatory response when exposed to patient’s blood. Although increasingly used, data regarding synthetic membrane’s superiority conflicting and controversial.8 High-flux dialyzers have larger pore size compared to low-flux dialyzers.

Figure 1.

The hemodialysis apparatus consists of hemodialysis machine, the blood circuit, the dialysis solution circuit, and the dialyzer.

The use of ultrapure water for preparation of dialysis solution is the standard of care in all HD units across the United States. Water treatment is a multistage process that involves sequential passage of regular tap water through a micro filter, activated carbon, water softener and Reverse Osmosis.8 The dialysis solution composition is a key step in achieving body fluid electrolyte and acid-base homeostasis in patients on HD. The ‘treated water’ is appropriately reconstituted close to the final entry of dialysis solution into the dialyzer. The blood and dialysis solution then flow through the dialyzer, in opposite directions to achieve maximum removal of solute from the blood to dialysate compartment.

In the U.S., majority of patients receive ‘in-centre’ HD for an average of three to four hours. Approximately two percent of HD is performed at home. Due to increasing recognition of importance of ‘time’ of HD sessions, daily home HD or in-centre long nocturnal (six to eight hours) HD are being encouraged. A patient with the support of a partner performs dialysis daily at home. Portable machines capable of performing safe dialysis at home are available and are catching the imagination of dialysis community.9

Debate continues in the nephrology world regarding the adequate dose (three times per week with target Kt/V 1.2 or daily short-HD or nocturnal-long HD etc.) of dialysis to be prescribed to improve outcomes in ESRD patients. Adequate’ HD, from a clinical perspective, should be considered to be the ‘dose’ at which the patient can lead a life as near to normal as possible in terms of physical and mental well being.

Peritoneal Dialysis

In peritoneal dialysis (PD), the dialysis solution (2 to 2.5 liters) is instilled in the peritoneal cavity within 15 to 20 minutes using a pre-inserted PD catheter. This is followed by a ‘dwell time’ ranging from four, six or twelve hours (depending upon the individual patient’s membrane type) in which the dialysis solution comes in contact with the peritoneal membrane. During this process, the transfer of solute and fluid takes place across the peritoneal membrane by the process of diffusion, (driven by concentration gradients across the membrane) and by convection (driven by osmotic and hydrostatic pressure gradients). Different solutes, based on their molecular size, equilibrate differently during the dwell time. At the end of the pre-determined dwell time, equilibrated dialysate is then ‘drained’ out and the next ‘exchange’ is started.

The ‘peritoneal-membrane’ is made of capillary wall, the interstitium and mesothelial cells. The permeability of the capillary wall can be described by the ‘three-pore model’ of membrane transport10, 11. Small solutes and water move across the ‘small-pores’, large solutes across ‘large-pores’ and only water moves across the ‘ultra-small pores’ (aquaporins). As each individual is unique and has a different body size and shoe size, each person differs in his or her ‘membrane-permeability’. The Peritoneal Equilibration Test can assess this12. Depending on the results of PET, the patients are classified in to slow (low), average or fast (high) transporters. Fast transporters remove solutes at a faster rate, and slow transporters equilibrate solutes at slower rate.

PD may be prescribed either intermittently or continuously in order to achieve an adequate solute clearance and water removal (ultrafiltration). In Continuous Ambulatory PD (CAPD), the patient performs three to five exchanges in 24 hours and the peritoneal cavity is never ‘dry’. The less used intermittent PD (IPD), only nighttime exchanges (Nocturnal IPD) are performed by a machine while the patient is asleep; Continuous cyclical PD (CCPD) is a hybrid of CAPD and IPD; nighttime machine exchanges followed by day time additional manual exchanges. Because of the continuous nature, patients on PD tolerate this form of dialysis better than HD primarily because of slower rate of water removal results in slower fluid shifts from the body compartments.

PD-related complications could be catheter-related or peritoneal membrane-related. Fluid-leaks and exit-site infections are complications of PD catheter insertion. The causes of catheter malfunction (poor drainage, problems with inflow) are constipation, intra-abdominal adhesions, catheter migration within the peritoneal cavity, catheter kinking, fibrin formation. Rise in intra peritoneal pressure may predispose patients to hernia formation at sites where abdominal wall is week. Although the rates of PD peritonitis has improved significantly over the years, it remains a major cause of patient dropout from PD to HD. Touch contamination of skin organisms are the most common causative organisms. Patients instill intra-peritoneal antibiotics at home for treatment. Less than 10% of PD peritonitis are severe and require hospitalization. Long-term exposure (typically > 5 years) of peritoneal membrane to unphysiologic PD solution and/or recurrent peritonitis, result in gradual loss of peritoneal membrane function that requires patient to transfer to HD. Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis is a rare complication of PD that results in thickening of the membrane and loss of function along with abdominal complication.

The survival of PD patients is better in the first two years of treatment compared to those on HD.13 Overall, long term patient survival is similar for both treatments. Mortality is determined by older age, diabetes and other co-morbid conditions. In general, older diabetic women do not do as well on PD as patients on HD.

Future of Renal Replacement Therapy

Exponential increase in the incidence of ESRD worldwide has generated interest in development of alternative forms of RRT. The xeno-transplantation (renal transplant between different species) is an area of intense research interest that when successful, will answer the issue of organ shortage for kidney transplant. Immune rejection and risk of infection transmission still remain a major concern14, 15 with kidney transplant.

Advances in Hemodialysis-Related Technologies

Hemodiafiltration, due to its increased clearance of ‘middle-molecules’ is being currently investigated in clinical trials.16 The use of specialized protein-leaking dialyzer membranes17 (providing increased clearance) and use of ‘membraneless’ dialysis18 (two parallel fluid streams exchanging solutes) is being investigated too. A cartridge containing living renal tubular cells lining the inside of the hollow fiber has been developed and is called Renal Tubular assist device. This device has been shown to provide ‘selective transport’ functions of kidney when connected in series with the dialyzer cartridge19. Advances in more ‘biocompatible’ PD fluids, gene therapy in improvement of PD has been recognized, but lacks clinical applications.14

Tissue Engineering and Stem Cell Research

This technology has a great potential in development of RRT but malignant transformation of cell and ethical issues remain main barriers in their clinical applications at this time. Integration of new nephrons, repair of nephrons in-situ using stem cells, generation of tissue by nuclear transplantation with embryonic stem cells and implantation of pluri-potent cells in peritoneal membranes, thus using the concept of ‘distributed renal functionality’ are some of techniques being developed14.

The Artificial Wearable Kidney

The use of the artificial wearable kidney (WAK) will enable patients with ESRD to receive higher doses of dialysis, longer and slower dialysis that is more physiological, at reduced cost offer improved quality of life. Davenport et al, in a pilot study20 have demonstrated that due to improved technology, the WAK is an exciting option for ESRD patients. Further clinical trials are ongoing to evaluate the application, performance and safety of WAK.21

Renal Replacement Therapy for Acute Kidney Injury

Sepsis remains the most common cause of Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) in hospitalized patients. Until recently, there was no consensus in the definition of acute renal failure, let alone an agreement on initiation of RRT in this population. There is a lack of prospective trials comparing alternative thresholds for initiation of dialysis, thus resulting in a wide variation of therapy for AKI between clinicians, inter and intra-center facilities.

Two basic forms of RRT are available in the U.S. for acute renal failures; both being forms of hemodialysis. Intermittent hemodialysis (IHD), as the name suggests is offered intermittently, usually limited to four-hour sessions and is not tolerated well by hemodynamically unstable patients. A hydrid-form of RRT called Slow Low-Efficiency Daliy Dialysis (SLED, SLEDD) offers the advantages of a continuous therapy but can be used intermittently. Continuous hemodialysis (abbreviated as CRRT) is a continuous form of dialysis and is tolerated well by an ICU cohort. Hemodiafiltration (HDF) is a technique that offers more clearance (inflammatory cytokines, for example which are elevated in septic patients) but has not shown to have survival benefit over hemodialysis. In fact, survival benefit has not been demonstrated in several underpowered randomized clinical trials between IHD and CRRT.1

Conclusion

Major improvements in dialysis technology, increased availability of medications that substitute endocrine functions of the kidneys, viz. recombinant erythropoietin, vitamin D analogues etc., ease of availability of all forms of dialysis therapies, have improved the care of ESRD patients on dialysis. The aim of renal replacement therapy is directed towards ‘overall well-being’ of the patients such that they can have a meaningful social life, and keep eligible patients healthy enough to undergo kidney transplantation.

Biography

Gautam Phadke, MD, is Clinical Fellow. Ramesh Khanna, MD, MSMA member since 2010, is the Karl D. Nolph, MD, Chair in Nephrology, Professor of Medicine, Director, Division of Nephrology. Both are at the University of Missouri School of Medicine.

Contact: khannar@health.missouri.edu.

Footnotes

Disclosure

None reported.

Referencces

- 1.Feehally J, Floege J, Johnson RJ. Comprehensive clinical nephrology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrett BJ, Parfrey PS, Morgan J, et al. Prediction of early death in end-stage renal disease patients starting dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997 Feb;29(2):214–222. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(97)90032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chandna SM, Schulz J, Lawrence C, Greenwood RN, Farrington K. Is there a rationale for rationing chronic dialysis? A hospital based cohort study of factors affecting survival and morbidity. BMJ. 1999 Jan 23;318(7178):217–223. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7178.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper BA, Branley P, Bulfone L, et al. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Early versus Late Initiation of Dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2010 Jun 27; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lameire N, Van Biesen W. Epidemiology of peritoneal dialysis: a story of believers and nonbelievers. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2010 Feb;6(2):75–82. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2009.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vanholder R, De Smet R, Glorieux G, et al. Review on uremic toxins: classification, concentration, and interindividual variability. Kidney Int. 2003 May;63(5):1934–1943. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Almeras C, Argiles A.The general picture of uremia Semin Dial July–August2009224329–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levy J. Oxford handbook of dialysis. 3rd ed. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nissenson AR, Fine RN. Handbook of dialysis therapy. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rippe B, Stelin G. Simulations of peritoneal solute transport during CAPD. Application of two-pore formalism. Kidney Int. 1989 May;35(5):1234–1244. doi: 10.1038/ki.1989.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rippe B, Stelin G, Haraldsson B. Computer simulations of peritoneal fluid transport in CAPD. Kidney Int. 1991 Aug;40(2):315–325. doi: 10.1038/ki.1991.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nolph KD, Twardowski ZJ, Khanna R.Peritoneal dialysis ASAIO Trans July–September198632111–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vonesh EF, Snyder JJ, Foley RN, Collins AJ. The differential impact of risk factors on mortality in hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. Kidney Int. 2004 Dec;66(6):2389–2401. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.66028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braam B, Verhaar MC, Blankestijn P, Boer WH, Joles JA. Technology insight: Innovative options for end-stage renal disease--from kidney refurbishment to artificial kidney. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2007 Oct;3(10):564–572. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Butler D. Last chance to stop and think on risks of xenotransplants. Nature. 1998 Jan 22;391(6665):320–324. doi: 10.1038/34749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Penne EL, Blankestijn PJ, Bots ML, et al. Resolving controversies regarding hemodiafiltration versus hemodialysis: the Dutch Convective Transport Study Semin Dial January–February200518147–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ward RA. Protein-leaking membranes for hemodialysis: a new class of membranes in search of an application? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005 Aug;16(8):2421–2430. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005010070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leonard EF, West AC, Shapley NC, Larsen MU. Dialysis without membranes: how and why? Blood Purif. 2004;22(1):92–100. doi: 10.1159/000074929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Humes HD, MacKay SM, Funke AJ, Buffington DA. Tissue engineering of a bioartificial renal tubule assist device: in vitro transport and metabolic characteristics. Kidney Int. 1999 Jun;55(6):2502–2514. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davenport A, Gura V, Ronco C, Beizai M, Ezon C, Rambod E. A wearable haemodialysis device for patients with end-stage renal failure: a pilot study. Lancet. 2007 Dec 15;370(9604):2005–2010. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61864-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gura V, Ronco C, Davenport A.The wearable artificial kidney, why and how: from holy grail to reality Semin Dial January–February200922113–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]