SUMMARY

Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive value are typically used to quantify the accuracy of a binary screening test. In some studies it may not be ethical or feasible to obtain definitive disease ascertainment for all subjects using a gold standard test. When a gold standard test cannot be used an imperfect reference test that is less than 100% sensitive and specific may be used instead. In breast cancer screening, for example, follow-up for cancer diagnosis is used as an imperfect reference test for women where it is not possible to obtain gold standard results. This incomplete ascertainment of true disease, or differential disease verification, can result in biased estimates of accuracy. In this paper, we derive the apparent accuracy values for studies subject to differential verification. We determine how the bias is affected by the accuracy of the imperfect reference test, the percent who receive the imperfect reference standard test not receiving the gold standard, the prevalence of the disease, and the correlation between the results for the screening test and the imperfect reference test. It is shown that designs with differential disease verification can yield biased estimates of accuracy. Estimates of sensitivity in cancer screening trials may be substantially biased. However, careful design decisions, including selection of the imperfect reference test, can help to minimize bias. A hypothetical breast cancer screening study is used to illustrate the problem.

Keywords: Bias, Predictive values, Screening, Sensitivity, Specificity

1 Introduction

In a trial by Lewin et al. [1], study participants were considered to have breast cancer if a suspicious screening result or signs and symptoms during follow-up led to pathological confirmation of disease. The accuracy of digital mammography was compared against two reference standards: the gold standard of biopsy followed by pathological confirmation, and an imperfect reference standard of follow-up for cancer status. Only women with suspicious imaging exams received biopsy.

In many screening trials, as in the trial by Lewin et al., [1], ethical and practical constraints make it impossible to apply the gold standard test to all study participants. Studies which use an imperfect reference standard in addition to a gold standard are subject to differential verification bias [2], [3], [4]. Differential verification can result in biased estimates of the accuracy of the screening test. Rutjes et al. [5] examined 487 screening studies published between 1999 and 2002, and found that 20% of the studies had differential verification. However, the bias could not be quantified, because the truth was unknown.

Differential verification bias differs from verification bias and imperfect reference standard bias. Verification bias occurs when only the data from participants who receive a gold standard test is used to assess diagnostic accuracy [6]. A variety of maximum likelihood (e.g., [6], [7], [8]) and Bayesian (e.g., [9], [10]) approaches are available to provide estimates of sensitivity and specificity in the presence of verification bias. Imperfect reference standard bias occurs when all study participants are evaluated with an imperfect reference standard. There is an extensive literature assessing bias in accuracy estimates resulting from the use of an imperfect reference test (e.g., [11], [12], [13], [14]). When the screening test and imperfect reference test are conditionally dependent, i.e. not independent conditional on the true disease status, use of an imperfect reference test can result in significant bias in estimates of accuracy [13].

In this manuscript, we quantify differential verification bias and describe the factors that affect it. We explicitly allow conditional dependence between the index test and the imperfect reference test. We focus on designs commonly used to evaluate the accuracy of breast cancer screening methods. In Section 2, we present equations to quantify the amount of differential verification bias in the apparent values of prevalence, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV). These equations are used in Section 3 to show the possible extent of the bias and investigate the impact various parameters have on the bias. In Section 4, we use accuracy values from the literature to construct a hypothetical breast cancer study with differential disease verification, and estimate the bias. We end with a discussion. The results of this study will allow investigators to choose their tests and designs in order to avoid or minimize differential verification bias.

2 Bias in studies with incomplete verification

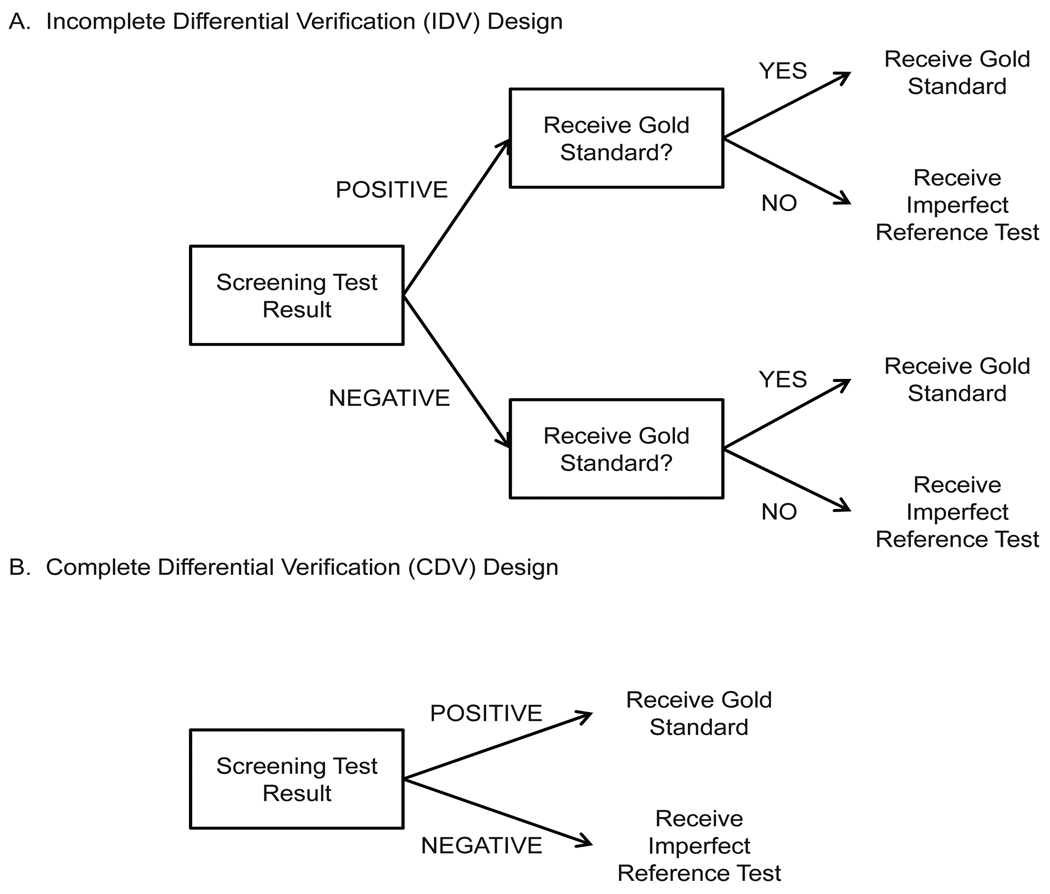

We consider two designs common in screening studies (Figure 1). In the first, the incomplete differential verification design (IDV), disease status is assessed using the gold standard for a fraction of the screen positives and for a fraction of screen negatives. Disease status is ascertained using an imperfect reference test for those who do not receive the gold standard. In the second design, the complete differential verification (CDV) design, the gold standard is applied to all screen positives and the imperfect reference test is given to all screen negatives. Motivated by the trial of Lewin et al. [1], we also consider a particular CDV design where the imperfect reference test is 100% specific but less than 100% sensitive.

Figure 1.

Diagram illustrating IDV and CDV designs.

Bias in screening studies depends on two measures of agreement or conditional dependence between the screening and imperfect reference tests: the true positive positive fraction (TPPF) and the true negative negative fraction (TNNF) [15]. The TPPF (pa in Table 1) is the probability that both the screening test and the imperfect reference test classify diseased subjects as having disease. The TNNF (ph) is the probability that both the screening test and the imperfect reference test classify non-diseased subjects as not having disease.

Table 1.

Cell probabilities for a study where all subjects receive screening test T, imperfect reference test R, and gold standard D. Some of the cells will not be observed for studies with differential disease verification. pa + pb + pc + pd = 1 and pe + pf + pg + ph = 1

|

2.1 Apparent accuracy in the IDV Design

Consider an IDV design where the gold standard test is administered to γ × 100% of the subjects who test positive with the screening test and τ × 100% of the screen negatives. An imperfect reference test is used to assess disease status for the remaining subjects.

Errors in the imperfect reference standard test can result in four types of misclassification: 1) true positives can be misclassified as false positives (pb in Table 1), 2) false positives can be misclassified as true positives (pe), 3) false negatives can be misclassified as true negatives (pd), and 4) true negatives can be misclassified as false negatives (pg).

Denote the true sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of screening test T as SeT, SpT, PPVT, and NPVT, respectively. Similarly, the sensitivity and specificity of the imperfect reference test R are denoted SeR and SpR, respectively. The prevalence of disease is π. In Appendix A we derive the following equations for apparent accuracy of the screening test T in an IDV design (denoted by subscript IDV):

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

These equations reduce to true disease prevalence and screening test accuracy when the imperfect reference test is 100% sensitive (i.e. SeR = 1) and 100% specific (i.e. SpR = 1).

Investigators can use the above equations to determine the amount of bias that would result from using an IDV design by subtracting true accuracy from the apparent accuracy calculated using the equations above. The amount of bias resulting from common scenarios are considered in Section 3.3. In addition to specifying the true sensitivity and specificity of the screening test and imperfect reference test along with disease prevalence, investigators need to specify the misclassification rates (pb, pd, pe, and pg), or the amount of agreement between the screening test and the imperfect reference test.

2.2 Apparent accuracy in the CDV Design

The CDV design is a special case of the IDV design where the gold standard is applied to all screen positives and the imperfect reference test is given to all screen negatives. That is, the CDV design is an IDV design where γ = 1 and τ = 0. In this design the cell probabilities pa + pb, pe + pf, pc + pg, and pd + ph are observed rather than the individual cell probabilities because of the differential disease verification.

Substituting γ = 1 and τ = 0 into equations (1)–(5) yields the following equations for the apparent accuracy of a CDV study (denoted by subscript CDV):

These equations reduce to true disease prevalence and screening test accuracy when the imperfect reference test is 100% sensitive (i.e. SeR = 1) and 100% specific (i.e. SpR = 1). When the imperfect reference test is 100% sensitive and 100% specific, pa = SeT and ph = SpT. By substituting these values into the above equation for πCDV, we see that πCDV reduces to the true disease prevalence and it follows that SeCDV = SeT.

By subtracting true accuracy values from the apparent values calculated using the equations above, investigators can determine the amount of bias resulting from a CDV design. PPV from a CDV design is equivalent to the true PPV because PPV is the proportion of screen positives with disease, and true disease status is obtained for all screen positives.

2.3 Bias for CDV design with 100% specific reference test

In some CDV studies the imperfect reference test is 100% specific but less than 100% sensitive. A common example is in cancer screening, where study participants are assumed to be cancer-free unless cancer is detected in follow-up. Follow-up occasionally misses cases of cancer. Thus, follow-up is 100% specific but less than 100% sensitive. This implies pe = pg = 0, ph = SpT, and pd is the probability of misclassification by the imperfect reference test. By substituting these values into the equations in Section 2.2, we obtain the following equations for the percent bias, which is the bias, apparent value minus the true value, divided by the true value multiplied by 100%. The percent bias is a function of the probability results are misclassified by the imperfect reference test (denoted MC).

where MC=πpd and Pr(T−) = 1 −[πSeT + (1 − π)(1 − SpT)].

It is clear from these equations that the CDV design will underestimate disease prevalence when the imperfect reference test has 100% specificity and less than 100% sensitivity, and thus, overestimate the sensitivity, specificity, and NPV of the screening test. The percent bias in estimating sensitivity, specificity, and NPV increases as MC, the probability results are misclassified by the imperfect reference test, increases. MC is greatest when the screening test and imperfect reference test have the highest agreement (TPPF). The magnitude of the bias for various scenarios with this design is considered in Section 3.1.

If the imperfect reference test is less than 100% sensitive and less than 100% specific, the CDV design could result in underestimation or overestimation of sensitivity and specificity depending on the accuracy of the imperfect reference test and the agreement between the screening and imperfect reference tests. Numerical examples are presented in Section 3.2.

3 Numerical Study

In this section numerical studies are performed to investigate the magnitude of bias in test accuracy that would be observed in CDV and IDV studies with varying true test accuracy, imperfect reference test accuracy, agreement between tests, and disease prevalence. We consider scenarios where the screening test is less accurate than the imperfect reference test (SeT=0.5, SeR=0.7, SpT=0.8, SpR=0.9), screening test and imperfect reference test have the same accuracy (SeT = SeR=0.7, SpT = SpR=0.9), and screening test is more accurate than the imperfect reference test (SeT=0.9, SeR=0.7, SpT=0.9, SpR=0.7).

Agreement is measured by TPPF for participants with disease and TNNF for participants without disease. TPPF and TNNF have the following constraints [16]:

We consider minimum agreement, maximum agreement, and median agreement which is calculated as the midpoint between minimum and maximum agreement.

3.1 CDV design with 100% specific reference test

We now discuss estimation of sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of the screening test in CDV studies where the reference test is 100% specific but less than 100% sensitive (Table 2).

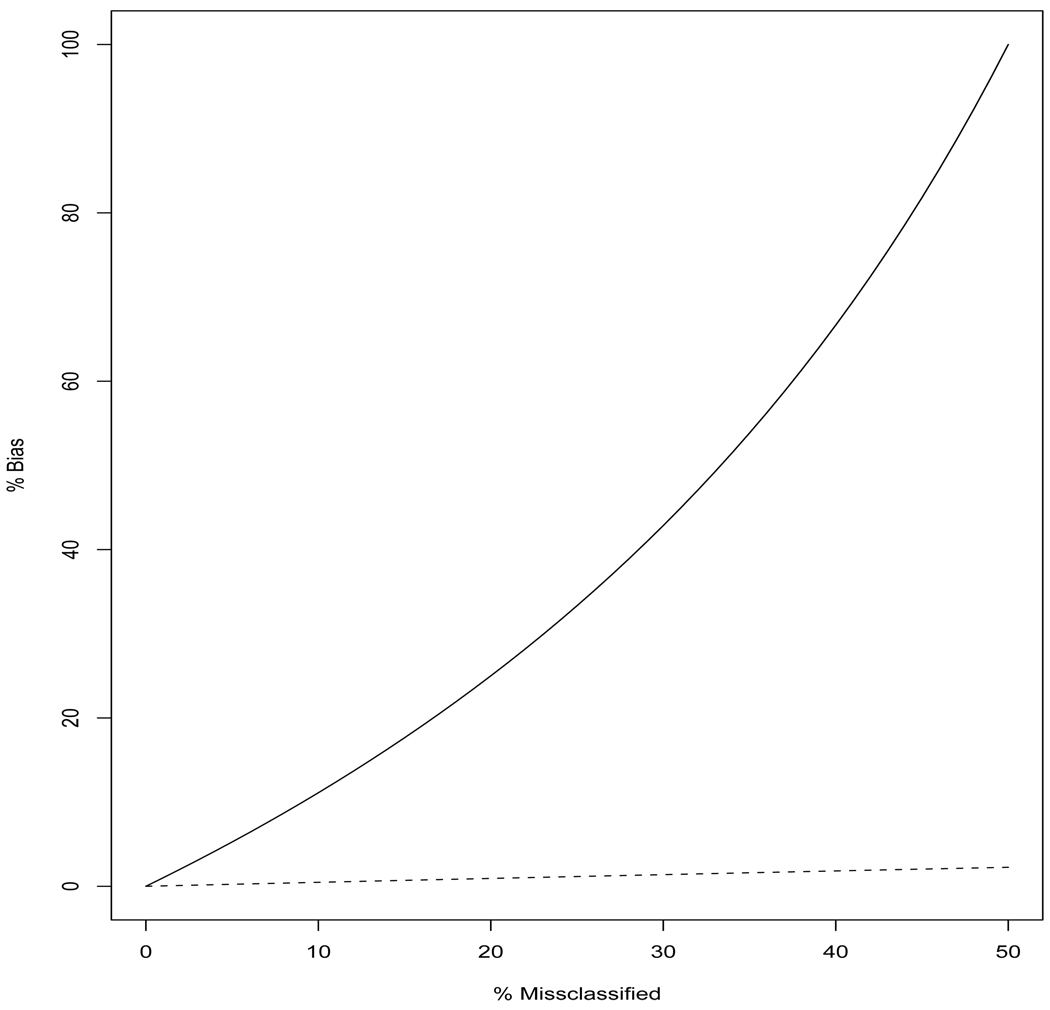

Sensitivity - There is no bias in estimating screening test sensitivity when there is minimum TPPF because this results in pd = 0 when SeT + SeR ≥ 1 which is true in the scenarios considered and typically in practice. However, increasing TPPF, increases the percentage of cases that screen negative and are incorrectly identified as non-cases by the imperfect reference standard test. This results in larger bias when estimating sensitivity (Figure 2). Sensitivity can be overestimated by as much as 100% when the sensitivity of the screening test and reference test are both 50% and there is maximum TPPF. That is, the CDV design would erroneously indicate the screening test was 100% sensitive when in truth it was only 50% sensitive. Increasing the sensitivity of the imperfect reference standard test decreases the bias observed for sensitivity.

Specificity - Similar to sensitivity, there is no bias in specificity when there is minimum TPPF and SeT + SeR ≥ 1. The magnitude of the bias observed for specificity (0.5%–2.3%) is much smaller than that for sensitivity (Figure 2) because in the scenarios considered only a small fraction of the truly non-diseased cases are misclassified by the imperfect reference test. The amount of bias in specificity increases as prevalence increases and decreases as the sensitivity of imperfect reference test increases.

PPV - There is no bias in PPV because PPV is the proportion of screen positives with disease, and in this design true disease status is obtained for all screen positives.

NPV - NPV is overestimated by up to 5% in the scenarios considered in Table 2. The amount of bias in NPV increases as prevalence increases, and bias decreases for increasing sensitivity of the imperfect reference test.

The observation that a CDV design with an imperfect reference that is 100% specific but less than 100% sensitive will overestimate the sensitivity and specificity of the screening test is consistent with the findings of [17].

Table 2.

Percent misclassification (MC) by the reference test and bias in apparent screening test sensitivity and specificity when a CDV design is employed with a reference test with 100% specificity. Disease prevalence is fixed at 10%. TNNF equals 0.7. Results are presented for minimum (MIN) and maximum (MAX) TPPF.

| % bias SeCDV | % bias SpCDV | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SeT, SpT, SeR, SpR | % MC MIN | % MC MAX | MIN | MAX | MIN | MAX |

| 0.5, 0.7, 0.5, 1.0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 100.0 | 0 | 2.3 |

| 0.5, 0.7, 0.7, 1.0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 42.9 | 0 | 1.4 |

| 0.5, 0.7, 0.9, 1.0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 11.1 | 0 | 0.5 |

| 0.7, 0.7, 0.5, 1.0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 42.9 | 0 | 1.4 |

| 0.7, 0.7, 0.7, 1.0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 42.9 | 0 | 1.4 |

| 0.7, 0.7, 0.9, 1.0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 11.1 | 0 | 0.5 |

| 0.9, 0.7, 0.5, 1.0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 11.1 | 0 | 0.5 |

| 0.9, 0.7, 0.7, 1.0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 11.1 | 0 | 0.5 |

| 0.9, 0.7, 0.9, 1.0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 11.1 | 0 | 0.5 |

Figure 2.

Percent bias in sensitivity (solid curve) and specificity (dashed curve) for CDV design where the imperfect reference test is 100% specific but less than 100% sensitive. The percentage of results misclassified is varied. Prevalence is 10% and SpT = 0.7.

3.2 CDV design

Consider CDV studies where the imperfect reference test is less than 100% sensitive and less than 100% specific.

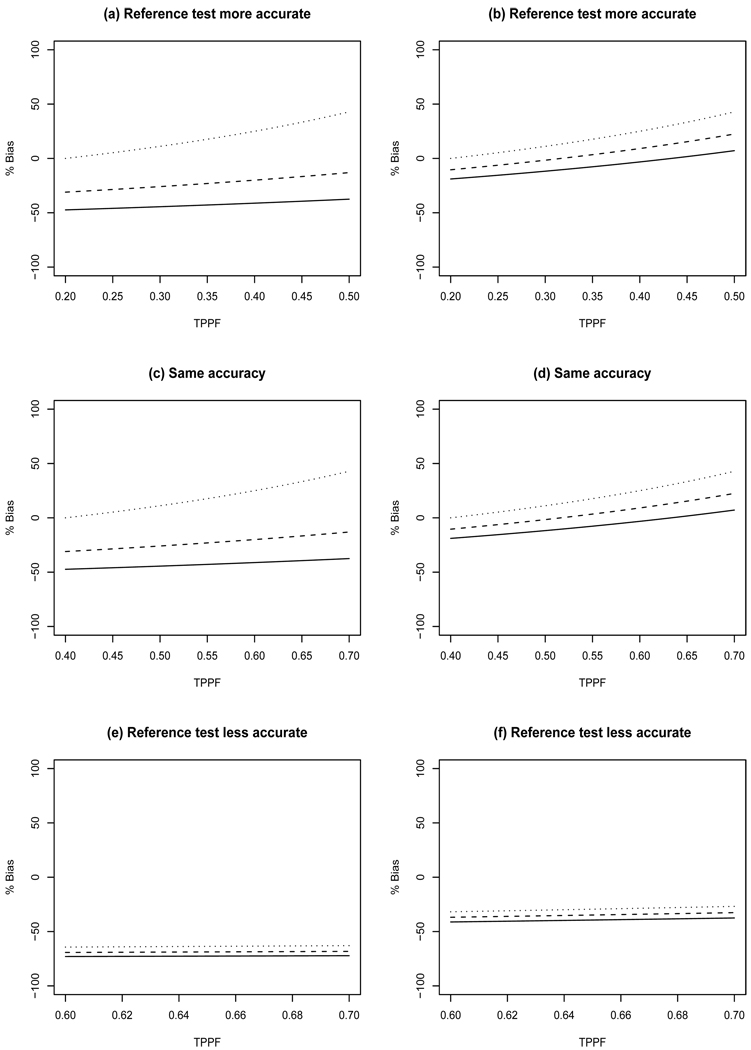

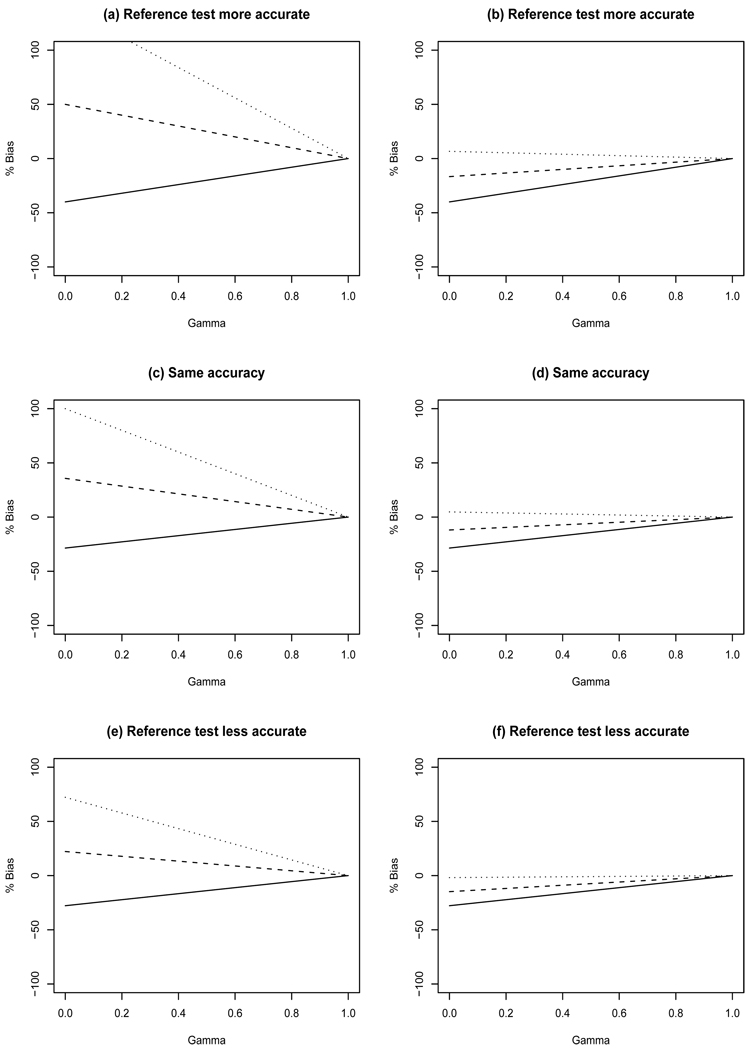

Sensitivity - In these scenarios the CDV design can result in overestimation or underestimation of true sensitivity depending on the amount of agreement between the screening and imperfect reference tests (Figure 3). The largest bias occurs when the screening test is more accurate than the imperfect reference test. Generally less bias is observed for larger TNNF because this results in less misclassification of results by the imperfect reference test. Increasing TPPF decreases bias, except for the case with maximum TNNF in which increasing TPPF increases bias. The magnitude of sensitivity bias decreases as the true prevalence increases.

Specificity - The bias for specificity is low with bias ranging from −4.8% to 2.8%.

PPV - There is no bias because PPV is the proportion of screen positives with disease, and in this design true disease status is obtained for all screen positives.

NPV - Percent bias for NPV ranges from −33% to 4% and −33% to 16% when true disease prevalence is 10% and 30%, respectively. Generally less bias is observed for larger TNNF because this results in less misclassification by the imperfect reference test.

Disease prevalence - Percent bias for prevalence ranges from −30% to 270% and −30% to 70% when the true disease prevalence is 10% and 30%, respectively. The magnitude of prevalence bias decreases as the true prevalence increases. The largest bias occurs when the screening test is more accurate than the imperfect reference test. Generally less bias is observed for larger TNNF because this results in less misclassification of results by the imperfect reference test. Increasing TPPF decreases bias, except for the case with maximum TNNF in which increasing TPPF increases bias.

Figure 3.

Percent bias in sensitivity resulting from CDV designs. Left panels have true prevalence of 10% while the right panels have prevalence of 30%. Top row: SeT=0.5, SpT=0.8, SeR=0.7, SpR=0.9; Middle row: SeT=0.7, SpT=0.9, SeR=0.7, SpR=0.9; Bottom row: SeT=0.9, SpT=0.9, SeR=0.7, SpR=0.7. Minimum TNNF (solid line), median TNNF (dashed line), and maximum TNNF (dotted line).

3.3 IDV design

We first consider IDV designs where γ × 100% of the screen positives receive the gold standard and the remaining screen positives and all screen negatives (i.e. τ=0) receive the imperfect reference test. The design γ = 0 is only subject to reference standard bias because an imperfect reference test is applied to all study subjects. Conversely, designs with γ > 0 results in differential verification bias.

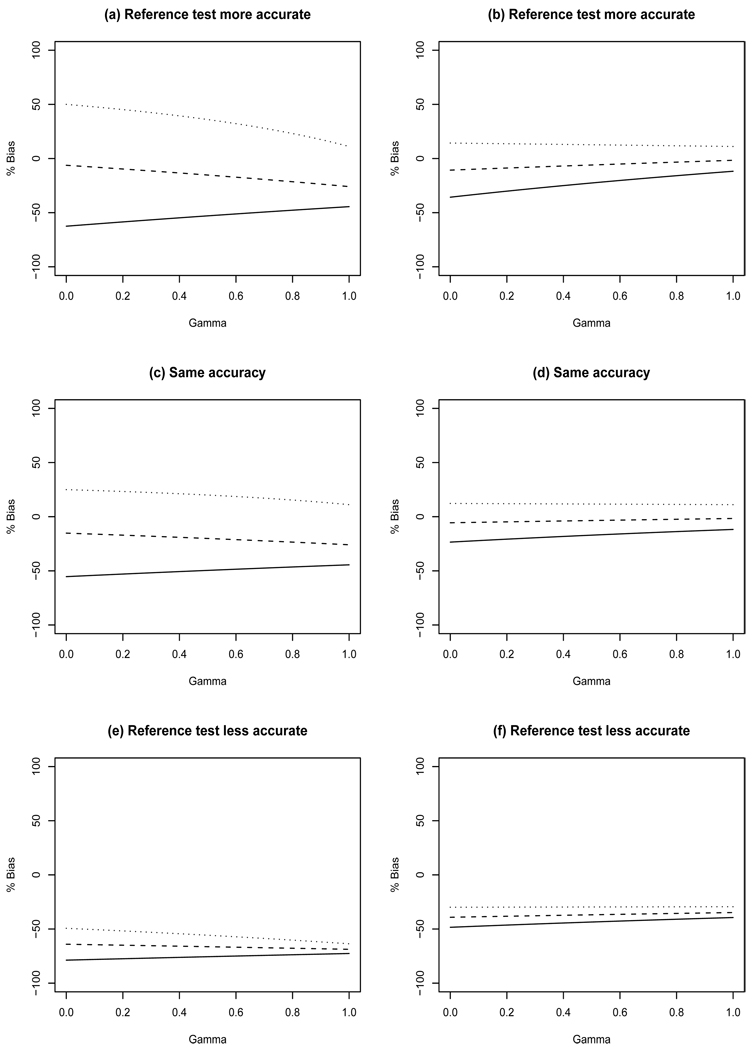

Sensitivity - This design can underestimate sensitivity by as much as 79% when γ = 0 (Figure 4e) and overestimate it by as much as 50% when γ = 0 (Figure 4a) when there is 10% disease prevalence. Smaller disease prevalence, similar to that considered in the breast cancer illustration in Section 4, yields even greater bias (results not shown). The largest amount of bias is observed for minimum TNNF because misclassification occurs when pg > 0, and as TNNF increases, pg must decrease for a fixed SeT. It is clear in Figure 4 that there is less bias for increasing prevalence. In addition, there is less bias for increasing γ except for median TNNF when there is 10% prevalence (Figures 4 a,c,e).

Specificity - This design results in little bias in specificity. For 10% prevalence, the bias ranges from −4.8% to 8.6%, −3.4% to 8.5%, and −8.2% to 6.9% for settings where the screening test has inferior, identical, and superior accuracy compared with the imperfect reference test. The amount of bias decreases as γ increases because more study participants have their disease status ascertained by the gold standard. As prevalence increases, this design yields increasing negative bias in estimating specificity. There is greater bias if accuracy of the screening and imperfect reference tests are equal but smaller than those considered (results not shown).

PPV - This design can result in substantial bias when estimating PPV for small values of γ (Figure 5). This design can overestimate PPV by as much as 140% (Figure 5a) and underestimate it by as much as 29% (Figure 5c). The largest amount of bias is observed for the maximum non-diseased agreement (i.e. TNNF). Again, bias decreases as γ increases and for increasing prevalence.

NPV - Since only results for screen negatives are included in estimation of NPV, NPV bias is not a function of γ. In this design none of the screen negatives receive the gold standard. This can result in varying amounts of bias when estimating NPV depending on the amount of agreement. For example, minimum TNNF results in bias of −11.1%, −9.9%, and −32.7% for settings where the screening test has inferior, identical, and superior accuracy compared with the imperfect reference test, respectively. Maximum TNNF results in bias of 1.4%, 1.2%, 6.9% for the same settings.

Figure 4.

Percent bias in sensitivity resulting from IDV designs with τ = 0. Left panels have true prevalence of 10% while the right panels have prevalence of 30%. Top row: SeT=0.5, SpT=0.8, SeR=0.7, SpR=0.9, TPPF=0.3; Middle row: SeT=0.7, SpT=0.9, SeR=0.7, SpR=0.9, TPPF=0.5; Bottom row: SeT=0.9, SpT=0.9, SeR=0.7, SpR=0.7, TPPF=0.65. Minimum TNNF (solid line), median TNNF (dashed line), and maximum TNNF (dotted line).

Figure 5.

Percent bias in PPV resulting from IDV designs with τ = 0. Left panels have true prevalence of 10% while the right panels have prevalence of 30%. Top row: SeT=0.5, SpT=0.8, SeR=0.7, SpR=0.9, TPPF=0.3; Middle row: SeT=0.7, SpT=0.9, SeR=0.7, SpR=0.9, TPPF=0.5; Bottom row: SeT=0.9, SpT=0.9, SeR=0.7, SpR=0.7, TPPF=0.65. Minimum TNNF (solid line), median TNNF (dashed line), and maximum TNNF (dotted line).

Next, we consider the effect of varying τ for IDV designs with a fixed value of γ. Increasing τ reduces the amount of bias when estimating sensitivity, specificity, and NPV for a fixed value of γ. For a fixed value of γ, there is no effect of varying τ on PPV estimation because there is no impact on results for the screen positives. For increasing τ, the percent bias for the apparent prevalence decreases linearly from overestimation to underestimation.

4 Breast cancer illustration

In the previous sections, we demonstrated that bias for accuracy studies can range from non-existent to severe in studies with differential disease verification. In a real screening study, what would the effect of bias be? In this section, we use data from observational studies to provide reasonable estimates of the diagnostic accuracy parameters for a hypothetical study of mammography screening for breast cancer. We then calculate the resulting bias present in the apparent estimates of diagnostic accuracy to demonstrate the utility of our methods.

We consider a study with a CDV design to assess the accuracy of mammography screening to detect breast cancer. All women who screen positive on mammography receive the gold standard test, biopsy. All women who screen negative on mammography receive the imperfect reference test, one year of clinical follow-up. Using data from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) [18], [19] and a report of 752,081 clinical breast examinations and screening mammography [20], we used the following parameter values in our analysis. Mammography has 79% sensitivity and 90% specificity [18]. Follow-up has a sensitivity of 59% and specificity of 93% [20]. The prevalence of breast cancer is 0.006 [21], [18] and TPPF and TNNF between mammography and follow-up are 0.43 and 0.83, respectively (based on data from [20]).

Using these parameter values, we calculated the bias for a CDV design, where all women in the study received a single round of screening mammography. The results are shown in Table 3. This design would substantially overestimate both breast cancer prevalence and the sensitivity of mammography screening. There would be little bias in the apparent specificity and NPV of mammography screening. There is no bias when estimating PPV because all screen positives have definitive disease status determined by the gold standard.

Table 3.

True and apparent accuracy parameters for hypothetical breast cancer screening study with CDV design.

| Parameter | Truth | Apparent value | Bias | Percent Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence | 0.006 | 0.0753 | 0.0693 | 1154.7% |

| Sensitivity | 0.79 | 0.063 | −0.73 | −92.0% |

| Specificity | 0.90 | 0.893 | −0.007 | −0.83% |

| PPV | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0% |

| NPV | 0.999 | 0.921 | −0.078 | −7.7% |

We made a few assumptions that could impact the amount of bias. First, we assumed that the diagnostic accuracy of clinical breast examination is roughly equivalent to that of clinical follow-up. We thought this was a reasonable assumption because clinical follow-up is positive when a woman or her physician detects signs or symptoms of disease including breast lumps, nipple discharge, skin changes, or architectural distortions [22]. In a clinical breast examination, a physician is looking for the same physical signs of breast cancer.

Second, we may have misspecified the amount of agreement between screening mammography and follow up. We calculated the TPPF as the proportion of cases with an abnormal clinical breast exam and an abnormal mammogram from Table 2 in [20]. We calculated the TNNF from the BCSC summary tables [18], [19] using the reported specificity of screening mammography and the proportion of non-cases who had a diagnostic mammogram due to signs and symptoms of breast cancer.

Finally, we used estimates of accuracy for mammography and follow-up from the largest studies available. However, we could have used different estimates. Prospective studies of the accuracy of mammography have yielded estimates of sensitivity ranging from 41% to 77% and specificity ranging from 92% to 98% [1], [21], [23], [24]. The sensitivity of clinical breast examination, as a surrogate for clinical follow-up, ranges from 21% to 59% and the specificity ranges from 92% to 99% [20],[25],[26],[27]. The estimates of bias in Table 3 are relatively insensitive to changes in the sensitivity or specificity of mammography, or the sensitivity of follow-up.

However, increasing the specificity of follow-up reduces the amount of bias. If the specificity of follow-up is 99% with minimum TNNF between mammography and follow-up, then the percent bias is 160.7% for prevalence, −61.4% for sensitivity, −0.1% for specificity, and −1.1% for NPV. If the specificity of follow-up is 99% with maximum TNNF between mammography and follow-up, then the percent bias is −5.0% for prevalence, 5.3% for sensitivity, 0.003% for specificity, and 0.03% for NPV. This illustrates that a CDV design can yield little bias in a low prevalence setting if the imperfect reference standard has high specificity. Statisticians designing screening trials can essentially remove differential verification bias in cancer screening by choosing a follow-up test with excellent specificity in a low prevalence setting.

5 Discussion

The formulae presented in this paper for calculating apparent accuracy requires one to specify the amount of agreement (TPPF and TNNF) expected between the screening test and imperfect reference test. If pilot data are not available to aid the determination of the magnitude of agreement, then a sensitivity analysis, similar to that of [28], could be performed for the minimum and maximum amounts of agreement. This approach is used in Section 3.

When bias is expected for a design with differential disease verification, it would be beneficial to have estimation methods that account or adjust for this differential verification so as to eliminate or reduce the amount of bias in the resulting estimates of accuracy. Maximum likelihood methods do not appear feasible in this setting because there are more parameters to be estimated than there are degrees of freedom in the data. An alternative may be to use a Bayesian approach that places prior distributions on the parameters. It may be possible to extend the Bayesian approaches used to correct for verification bias (e.g., [9], [10]) to adjust for differential verification bias, similar to the recent work of Lu et al. [29]. This is an area that requires future attention.

In early phases of the development of disease screening, investigators often assess the performance of a screening test using apparent sensitivity and specificity [30]. As shown in this paper, apparent estimates of sensitivity and specificity may be biased. This bias may be unavoidable, due to ethical and practical constraints. There are four strategies to avoid or reduce bias. First, mortality can be used as an endpoint rather than diagnosis of cancer. Mortality studies, however, are costly and take years to complete, making them impractical for many applications. Second, the probability of interval cancers before and after the introduction of a cancer screening test can be compared [31]. The third strategy to reduce bias is to obtain gold standard results for more subjects. This strategy is often impossible and unethical in cancer screening trials. The fourth strategy is to select the most appropriate imperfect reference standard depending on the anticipated accuracy of the screening test and disease prevalence.

We have shown that the bias when estimating accuracy is low when the following four conditions are satisfied: (1) the disease has very low prevalence; (2) the imperfect reference test has high specificity; (3) the true negative negative fraction attains its maximum; and (4) the screening test has high sensitivity. These conditions hold in many cancer screening trials. Both investigators and statisticians should be reassured as to the accuracy of their estimates.

Acknowledgements

This research is partially funded by NIH 1R03CA136048-01A1. The authors would like to thank an associate editor and two reviewers for their valuable comments that led to an improved article.

Appendix A

Technical derivation of apparent accuracy in IDV design

Consider a study with an IDV design where the binary test result T is available for all subjects. Based on results of T, subjects either receive the gold standard assessment of disease (D) or an imperfect reference test R. Let V + indicate those that receive the gold standard and V − those that receive the reference test. Then we calculate the following probabilities:

Next, we derive equations 1–5 by using the values for the above probabilities as needed.

Equation 1 is obtained by replacing pc in the above equation with SeR − pa and pg with SpT − ph. Equations 2–4 are calculated as follows.

Contributor Information

Todd A. Alonzo, Division of Biostatistics, University of Southern California, Keck School of Medicine, 440 E. Huntington Dr, 4th floor, Arcadia, CA 91006, USA, talonzo@childrensoncologygroup.org, Phone: 626-241-1522, Fax: 626-445-4334

John T. Brinton, Department of Biostatistics, Colorado School of Public Health, University of Colorado, Denver, CO, USA

Brandy M. Ringham, Department of Biostatistics, Colorado School of Public Health, University of Colorado, Denver, CO, USA

Deborah H. Glueck, Department of Biostatistics, Colorado School of Public Health, University of Colorado, Denver, CO, USA

References

- 1.Lewin JM, Hendrick RE, D’Orsi CJ, Isaacs PK, Moss LJ, Karellas A, Sisney GA, Kuni CC, Cutter GR. Comparison of full-field digital mammography with screen film mammography for cancer detection: results of 4,945 paired examinations. Radiology. 2001;218:873–880. doi: 10.1148/radiology.218.3.r01mr29873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lijmer JG, Mol BW, Heisterkamp S, Bonsel GJ, Prins MH, van der Meulen JHP, Bossuyt PM. Empirical evidence of design-related bias in studies of diagnostic tests. JAMA. 1999;282:1061–1066. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.11.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glueck DH, Lamb MM, O’Donnell CI, Ringham BM, Brinton JT, Muller KE, Lewin JM, Alonzo TA, Pisano ED. Bias in trials comparing paired continuous tests can cause researchers to choose the wrong screening modality. BMC medical research methodology. 2009;9:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ringham BM, Alonzo TA, Grunwald GK, Glueck DH. Estimates of observed sensitivity and specificity must be corrected when reporting the results of the second test in a screening trial conducted in series. BMC medical research methodology. 2010;10:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rutjes AW, Reitsma JB, Di Nisio M, Smidt N, van Rijn JC, Bossuyt PMM. Evidence of bias and variation in diagnostic accuracy studies. CMAJ. 2006;174:1–12. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Begg CB, Greenes RA. Assessment of diagnostic tests when disease is subject to selection bias. Biometrics. 1983;39:207–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baker SG. Evaluating multiple diagnostic tests with partial verification. Biometrics. 1995;51:330–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou XH. Correcting for verification bias in studies of a diagnostic test’s accuracy. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 1998;7:337–353. doi: 10.1177/096228029800700403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martinez EZ, Achcar JA, Louzada-Neto F. Estimators of sensitivity and specificity in the presence of verification bias: a bayesian approach. Computational Statistics and Data Analysis. 2006;51:601–611. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buzoianu M, Kadane JB. Adjusting for verification bias in diagnostic test evaluation: a bayesian approach. Statistics in Medicine. 2008;27:2453–2473. doi: 10.1002/sim.3099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vacek PM. The effect of conditional dependence on the evaluation of diagnostic tests. Biometrics. 1985;41:959–968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baker SG. Evaluating a new test using a reference test with estimated sensitivity and specificity. Communication in Statistics: Theory and Methods. 1991;20:2739–2752. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Torrance-Rynard VL, Walter SD. Effects of dependent errors in the assessment of diagnostic test performance. Statistics in Medicine. 1997;16:2157–2175. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19971015)16:19<2157::aid-sim653>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reitsma JB, Rutjes AW, Khan KS, Coomarasamy A, Bossuyt PM. A review of solutions for diagnostic accuracy studies with an imperfect reference or missing reference standard. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2009;62:797–806. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pepe MS. The Statistical Evaluation of Medical Tests for Classification and Prediction. Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alonzo TA, Braun TM, Moskowitz CS. Small sample estimation of relative accuracy for binary screening tests. Statistics in Medicine. 2004;15:21–34. doi: 10.1002/sim.1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Panzer RJ, Suchman AL, Griner PF. Workup bias in prediction research. Medical Decision Making. 1987;7:115–119. doi: 10.1177/0272989X8700700209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.NCI-funded Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium co-operative agreement (U01CA63740, U01CA86076, U01CA86082, U01CA63736, U01CA70013, U01CA69976, U01CA63731, U01CA70040) 2010 May; http://www.breastscreening.cancer.gov/data/benchmarks/screening/tableSensSpec.html.

- 19.NCI-funded Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium co-operative agreement (U01CA63740, U01CA86076, U01CA86082, U01CA63736, U01CA70013, U01CA69976, U01CA63731, U01CA70040) 2010 May; http://www.breastscreening.cancer.gov/data/benchmarks/diagnostic/tableSensSpec.html.

- 20.Bobo JK, Lee NC, Thames SF. Findings from 752,081 clinical breast examinations reported to a national screening program from 1995 through 1998. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2000;92:971–976. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.12.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pisano ED, Gatsonis C, Hendrick E, Yaffe M, Baum JK, Acharyya S, Conant EF, Fajardo LL, Bassett L, D’Orsi C, Jong R, Rebner M. Digital mammographic imaging screening trial (DMIST) investigators group: Diagnostic performance of digital versus film mammography for breast-cancer screening. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353:1773–1783. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ikeda DM, Andersson I, Wattsgard C, Janzon L, Linell F. Interval carcinomas in the Malmo mammagraphic screening trial: radiographic appearance and prognostic considerations. American Journal of Roentgenology. 1992;159:287–294. doi: 10.2214/ajr.159.2.1632342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skaane P, Hofvind S, Skjennald A. Randomized trial of screen-film versus full-field digital mammography with soft-copy reading in population-based screening program: follow-up and final results of Oslo II study. Radiology. 2007;244:708–717. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2443061478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poplack SP, Tosteson AN, Grove MR, Wells WA, Carney PA. Mammography in 53,803 women from the new hampshire mammography network. Radiology. 2000;217:832–840. doi: 10.1148/radiology.217.3.r00dc33832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berg WA, Gutierrez L, NessAiver MS, Carter WB, Bhargavan M, Lewis RS, Ioffe OB. Diagnostic accurcy of mammography, clinical examination, US, and MR imaging in peroperative assessment of breast cancer. Radiology. 2004;233:830–849. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2333031484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kolb TM, Lichy J, Newhouse JH. Performance of screening mammography, physical examination, and breast US and evaluation of factors that influence them: an analysis of 27,825 patient evaluations. Radiology. 2002;225:165–175. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2251011667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oestreicher N, Lehman CD, Seger DJ, Buist DS, White E. The incremental contribution of clinical breast examination to invasive cancer detection in a mammography screening program. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2005;184:428–432. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.2.01840428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schneeweiss S. Sensitivity analysis of the diagnostic value of endoscopies in cross-sectional studies in the absence of a gold standard. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care. 2000;16:834–841. doi: 10.1017/s0266462300102107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu Y, Dendukuri N, Schiller I, Joseph L. A Bayesian approach to simultaneously adjusting for verification and reference standard bias in diagnostic test studies. Statistics in Medicine. 2010;29:2532–2543. doi: 10.1002/sim.4018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pepe MS, Etzioni R, Feng Z, Potter JD, Thompson M, Thornquist M, Winget M, Yasui Y. Phases of biomarker development for early detection of cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2001;93:1054–1061. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.14.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baker SG. Improving the biomarker pipeline to develop and evaluate cancer screening tests. JNCI. 2009;101:1–4. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]