Highlights

► Costimulatory pathways have a critical role in the regulation of alloreactivity. ► A complex network of positive and negative pathways regulates T cell responses. ► Blocking costimulation improves allograft survival in rodents and non-human primates. ► The costimulation blocker belatacept is being developed as immunosuppressive drug in renal transplantation.

Keywords: T cell costimulation, Costimulation blockade, Transplantation, Tolerance

Abstract

Secondary, so-called costimulatory, signals are critically required for the process of T cell activation. Since landmark studies defined that T cells receiving a T cell receptor signal without a costimulatory signal, are tolerized in vitro, the investigation of T cell costimulation has attracted intense interest. Early studies demonstrated that interrupting T cell costimulation allows attenuation of the alloresponse, which is particularly difficult to modulate due to the clone size of alloreactive T cells. The understanding of costimulation has since evolved substantially and now encompasses not only positive signals involved in T cell activation but also negative signals inhibiting T cell activation and promoting T cell tolerance. Costimulation blockade has been used effectively for the induction of tolerance in rodent models of transplantation, but turned out to be less potent in large animals and humans. In this overview we will discuss the evolution of the concept of T cell costimulation, the potential of ‘classical’ and newly identified costimulation pathways as therapeutic targets for organ transplantation as well as progress towards clinical application of the first costimulation blocking compound.

1. Introduction

The development of new immunosuppressive drugs together with other innovations has lowered acute rejection rates and has improved short-term graft survival after organ transplantation, but long-term graft survival improved much less [1]. T cells play a central role in the immune response towards allografts [2]. Therefore, interfering with T cell activation offers the potential of prolonging graft survival through modulation of the alloresponse. The process of T cell activation is now recognized to involve multiple signals and distinctly regulated pathways. A 2-signal model was initially proposed by Lafferty and Cunningham in 1975 [3]. Signal 1 is delivered through the T-cell receptor (TCR) interacting with cognate antigen in the context of MHC and initiates the T cell activation process. Signal 1 alone is, however, insufficient for full T cell activation but rather leads to T cell anergy [4]. An additional signal 2 – the so-called costimulatory signal – provided by a number of specialised cell surface receptors is required for survival, clonal expansion and differentiation of activated T cells.

The paradigm of T cell costimulation originally implicated that blocking costimulatory signals at the time of antigen encounter abrogates a T cell response and induces T cell anergy, an antigen-specific state of tolerance. Consequently great interest was triggered in exploiting the concept of T cell costimulation therapeutically with the goal of more selectively targeting the T cell allo-responses [5] and possibly even inducing immunologic tolerance [6]. Over the last two decades, noticable progress has indeed been made in the development of ‘costimulation blockers’ for the use in transplant recipients (which is discussed in more detail later) [6,7]. In the meantime, our understanding of T cell costimulation at the molecular level has evolved considerably, too. It is now recognized that the spectrum of mechanisms triggered by costimulation blockade involves not only anergy, but also clonal deletion and regulation [8,9]. Moreover, while costimulation blockade effectively induces allograft tolerance in selected rodent models [10,11], it has become evident that it is insufficient to do so in non-human primates (NHP) [12–15]. Memory T cells – whose frequency is markedly higher in NHP than in laboratory rodents and which are less dependent on conventional costimulation signals – have been identified as a major factor in costimulation blockade-resistant rejection [16,17]. Finally, with the identification of numerous additional costimulation pathways, including those that negatively regulate T cell activation, the concept of T cell costimulation is now much more complex and its therapeutic exploitation less straightforward than originally anticipated [18].

2. Costimulatory pathways

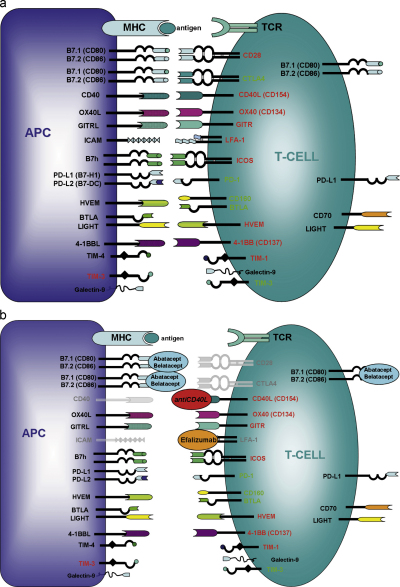

Costimulatory molecules can be categorized based either on their functional attributes or on their structure. The costimulatory molecules discussed in this review will be divided into (1) positive costimulatory pathways: promoting T cell activation, survival and/or differentiation; (2) negative costimulatory pathways: antagonizing TCR signalling and suppressing T cell activation; (3) as third group we will discuss the members of the TIM family, a rather “new” family of cell surface molecules involved in the regulation of T cell differentiation and Treg function. According to structure, costimulatory molecules can be broadly divided into 4 distinct groups: (i) the immunoglobulin (Ig) family (e.g. CD28, CTLA4, PD-1, ICOS), (ii) the TNF–TNFR family (e.g. CD40, CD137, OX40), (iii) the TIM family and (iv) cell adhesion molecules (e.g. CD2, LFA-1). In addition to discussing the “classical” targets of costimulation blockade (CD28, CD154), we will focus on selected other costimulation pathways with therapeutic potential in organ transplantation (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Costimulatory pathways relevant in transplantation. (a) Expression patterns of costimulatory molecules on T cells and APC are depicted. Categorization according to structure and function as positive or negative signalling pathway are indicated. (b) Costimulation blockers in (pre)clinical development and their ligands are depicted. Signals inhibited by these compounds are shown in grey.

2.1. Positive costimulatory pathways

2.1.1. Costimulatory molecules of the Ig family

2.1.1.1. CD28/B7 pathway

The CD28 costimulation pathway is one of the best characterized and probably the most important one for naïve T cell activation in both mouse and humans. CD28 is a homodimeric transmembrane protein which is constitutively expressed on all T cell subsets in mice, and on 95% of CD4 and 50% of CD8 T cells in humans [19]. CD28 binds to B7.1 (CD80) which is inducibly expressed and B7.2 (CD86), which is constitutively expressed on the surface of APCs [20,21]. B7.1 and B7.2 expression is also found on T cells [21]. Upon engagement with its ligands, CD28 provides a costimulatory signal triggering survival, proliferation and cytokine production of T cells. CD28/B7 ligation in the presence of TCR stimulation increases the expression of the IL2 receptor α-chain (CD25) and of CD40 ligand (CD40L and CD154), and induces cytokine production, including IL2 and interferon-γ (IFNγ). Furthermore, expression of anti-apoptotic molecules (e.g. Bcl-xL) is enhanced and IL2/CD25 binding activates the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway initiating T cell proliferation [22]. TCR stimulation in the absence of CD28 signalling induces classical T cell anergy in vitro [23]. Anergic T cells are functionally inactivated with reduced proliferation, differentiation and cytokine production [24].

Upon activation, T cells up-regulate the negative costimulatory molecule cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated-antigen 4 (CTLA4 and CD152), which shares ∼20% homology with CD28 and binds the same ligands as CD28, i.e. B7.1 and B7.2. Notably, CTLA4 binds B7 molecules with higher avidity and affinity, thereby outcompeting CD28 and preventing its ligation. Moreover, the intracellular CTLA4 signal directly antagonizes CD28 signalling by inhibiting AKT [19]. Thus, CTLA4 provides a negative feedback loop that down-regulates T cell responses [25,26]. Besides, CTLA4 is constitutively expressed on FoxP3+ Tregs and is critical for their suppressor function [27,28]. CTLA4-dependent ligation of B7 also transmits outside-in signals to the APC, down-modulating expression of B7 molecules [29] and up-regulating the tolerogenic enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) [30].

As direct blockade of CD28 with anti-CD28 mAbs turned out to be difficult due to unwanted agonistic ‘side effects’, alternative strategies were sought and resulted in the development of the fusion protein CTLA4Ig [31]. This fusion protein consists of the extracellular CTLA4 domain and the Fc portion of IgG1. Due to its higher affinity CTLA4Ig prevents CD28 signals by outcompeting CD28 for binding to its only ligands CD80/86 [32]. At the time when CTLA4Ig was designed, the higher binding affinity but not the physiologic function of CTLA4 as negative regulator had been revealed [33]. Only later it was recognized that blocking CD80/86 also prevents ligation of CTLA4 and thus prevents a negative costimulatory signal to the T cell. CTLA4Ig (abatacept) has since been approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis [34] and a second generation CTLA4Ig, belatacept [35], is close to clinical approval for renal transplantation (see below) [36,37]. Another approach to target CD28 was the development of anti-CD80/86 monoclonal antibodies (mAb). Anti-CD80/86 prolonged renal allograft survival in non-human primates (NHP) [38,39] and were tested in a phase I clinical trial [40]. Further development seems uncertain [28] in particular in view of CTLA4's role in the induction of peripheral tolerance [41].

In vivo blockade of CD28 with CTLA4Ig potently prolongs allograft survival in numerous rodent models [42–44]. CTLA4Ig induces long-term survival of heart [44,45], islet [46] and renal grafts [47,48], although donor splenocyte transfusion (DST) – promoting the generation of Tregs [49] – was required for the induction of robust tolerance in most models [43]. CTLA4Ig synergizes with other costimulation blockers, most notably with anti-CD154 [10]. The timing of CTLA4Ig administration influences its effects with delayed administration leading to superior results [43], probably by allowing up-regulation and engagement of CTLA4 [9,50]. Although CTLA4Ig is highly effective in rodent models, it does not lead to skin graft tolerance across MHC barriers [10,42]. Translation of CTLA4Ig therapy into NHP was disappointing at first, with only modest prolongation of allograft survival [12,51], which prompted the development of belatacept, a 2nd generation CTLA4Ig with increased binding affinity [35]. Recently, alefacept, a dimeric fusion protein consisting of the CD2-binding portion of the human lymphocyte function-associated antigen-3 (LFA-3) linked to the Fc portion of human IgG1, was found to act synergistically with CTLA4Ig in NHP renal transplantation [52]. Alloreactive CD8 T cells progressively lose CD28 expression upon activation, becoming increasingly insensitive to CD28 blockade by CTLA4Ig/belatacept. However, since they upregulate CD2 in this process, alefacept effectively targets those effector/memory CD8 cells that are not controlled by CTLA4Ig/belatacept [53]. As alefacept is clinically approved for the treatment of psoriasis, this combination of treatments offers immediate potential for clinical translation.

Recently, interest in CD28-specific mAbs was rekindled. Two types of agonistic anti-CD28 mAbs can be distinguished [54]: superagonistic anti-CD28 mAbs induce full T cell activation even in the absence of TCR stimulation, whereas conventional (agonistic) anti-CD28 mAbs provide a costimulatory signal only in combination with TCR stimulation. Superagonistic anti-CD28 mAb leads to the preferential activation and expansion of Tregs in vitro and in vivo [55,56]. Agonistic anti-CD28 mAbs prevent autoimmune diseases [57], GVHD [58] and prolong allograft survival [59,60] in rodent models. Clinical development of superagonistic anti-CD28 had to be stopped, however, after catastrophic results from a phase I trial. Six healthy volunteers experienced a massive cytokine storm upon administration of a superagonistic anti-CD28 mAb [61]. In rodents, in sharp contrast, superagonistic anti-CD28 therapy had not been associated with massive release of pro-inflammatory cytokines [57], presumably because activation and expansion of Tregs effectively suppressed the inflammatory response [62]. Recently, progress was reported in the development of mAbs blocking CD28 without agonistic activity. A monovalent single chain antibody (sc28AT) prevented T cell proliferation and cytokine production in vitro and synergized with CNIs to prevent acute and chronic allograft rejection in NHP models [63]. By selectively blocking CD28, CTLA4 (and presumably PDL-1) signals remain intact and contribute to the immunomodulatory effects.

2.1.1.2. ICOS/B7h pathway

The CD28 homolog inducible costimulatory molecule (ICOS) is expressed upon activation in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and persists in effector and memory T cells [64,65]. ICOS binds to its ligand B7h (B7 homolog; B7-H2, ICOSL) which is structurally related to B7-1/2 but does not bind to CD28 or CTLA4 [66]. Signalling through ICOS enhances T cell proliferation, survival and cytokine production and is important for T–B cell interactions, providing help to B cells [67]. ICOS expression on B cells is involved in the immunoglobulin class switch [64], germinal center formation and memory B cell generation [21]. Furthermore ICOS is upregulated on NK cells, promoting NK cell function [68].

ICOS is expressed on both Th1 and Th2 cells, however expression is higher on Th2 cells. In non-transplant settings, ICOS blockade effectively inhibits Th2 responses through mechanisms requiring intact CTLA4 and STAT6 signalling pathways [69]. A critical role for ICOS in Th1 responses was not observed in models examining primary and recall responses [70] but it seems to regulate CD28-independent anti-viral Th1 and Th2 responses and cytokine proliferation [71]. Anti-ICOS mAbs prolong cardiac allograft survival [72], with timing of ICOS blockade being a critical factor as only delayed blockade suppresses effector CD8+ T cell generation and significantly extends allograft survival [69]. ICOS blockade prolongs allograft survival to a lesser degree than anti-CD40L mAbs or CTLA4Ig [72], but combined treatment with either of these results in long-term cardiac allograft survival and prevents chronic rejection [73]. Thus co-blockade of ICOS/B7h and CD28/B7 or CD40/CD40L has synergistic effects on the prevention of allograft rejection.

2.1.2. Costimulatory molecules of the TNF/TNFR family

2.1.2.1. CD40/CD154 pathway

In addition to CD28/B7, the CD40/CD154 (CD40L) pathway is the second major pathway on which interest focuses in transplantation medicine. CD40 is a member of the TNFR superfamily and is constitutively expressed – at low levels – on the surface of APCs, including B cells, endothelial cells and fibroblasts [74] and is significantly upregulated upon activation [75]. Ligation of CD40 is critical for DC activation and maturation as well as for B cell activation and the immunoglobulin class switch. Downstream signalling of CD40 leads to up-regulation of MHC molecules and costimulatory molecules of the B7 family as well as increased inflammatory cytokine production [18]. CD154 (CD40L) – the only known ligand of CD40 – belongs to the TNF superfamily, is expressed on activated T cells (including iNKT cells) and subsets of NK cells, eosinophils and platelets [74]. To date, it has still not been fully resolved whether CD40L transmits a signal to T cells, which is of particular interest with regard to the development of antibodies to CD40L/CD40 [76–80]. Mutations in the CD40 or the CD40L gene cause the hyper IgM syndrome, an immunodeficiency disorder characterized by defects of immunoglobulin class switch recombination, with or without defects of somatic hypermutation leading to humoral immunodeficiency and a susceptibility to opportunistic infections [81].

Increased levels of CD40 (upon activation) result in increased CD40/CD154 interactions and an increased strength of antigen specific signals, making interruption of this pathway an attractive therapeutic target in autoimmune diseases [82] and allograft rejection [5,18]. Blockade of CD40/CD154 costimulation (by either anti-CD154 mAb or genetic knockout) is exceptionally effective in experimental transplantation models [9], preventing acute rejection and prolonging allograft survival [83]. However, CD40/CD154 blockade on its own does not prevent chronic rejection [84,85]. The therapeutic efficacy of CD40/CD154 blockade is increased through combination with a number of other therapies, in particular DST, CTLA4Ig and rapamycin [86]. Combining anti-CD154 mAbs with DST leads to donor-specific tolerance without signs of chronic rejection in murine models of islet and cardiac allograft transplantation [10]. Although CTLA4Ig was shown to synergize with anti-CD154 mAb [10], long-term skin graft survival was not achieved when stringent strain combinations were used [87,88].

Monoclonal antibodies specific for CD154 have shown great promise in both rodent and early NHP models [10,12,13,89]. Unexpectedly, however, anti-humanCD154 antibodies were associated with severe thromboembolic complications in a phase I trial [90] (and subsequent NHP studies [91]). Clinical development of anti-CD154 mAbs was suspended indefinitely. The pro-thrombotic effects of anti-CD154 mAbs were identified to involve the expression of CD154 on platelets where it participates in the stabilization of thrombi [92]. Anti-CD40 mAbs are an alternative approach for blocking CD40/CD154 costimulatory signals without interfering with the aggregation of platelets. Results obtained with newly designed anti-CD40 mAbs are encouraging [93,94]. A chimeric anti-CD40 mAb (Chi220) substantially prolongs islet allograft survival in rhesus macaques, acting synergistically with belatacept [93]. Several anti-CD40 mAbs are currently under investigation, with at least one of them having recently entered clinical development (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01279538).

2.1.2.2. OX40/OX40L

The costimulatory molecule OX40 (CD134) belongs to the TNFR family, is expressed on activated T cells [95] (preferentially on CD4+ T cells including activated Tregs) and mediates T cell differentiation, proliferation and survival [96]. OX40 ligand (OX40L) is expressed on activated dendritic cells, B cells and vascular epithelial cells [97]. Signalling through the OX40/OX40L pathway is critical for humoral immune responses and enhances B cell proliferation and differentiation [97]. OX40 costimulation is not dependent on intact CD28 signalling although CD28 signal up-regulates OX40 expression on T cells [98]. OX40 has a critical role in regulating differentiation programs for Th1/Th2 as well as memory T cell generation [96,99,100].

Blockade of the OX40/OX40L pathway (using anti-OX40L mAbs) has little effect on the survival of allografts. However, OX40 plays a critical role in CD28- and CD40-independent rejection as anti-OX40L prolongs allograft survival in CD28/CD40L double deficient mice [101] and synergizes with CD154- and/or CD28-blockade to prevent allograft rejection [101,102]. Although OX40 signalling seems to have little impact on primary T cell responses [101], it is important for the survival of activated T cells and memory T cell generation [103]. Thus, OX40 blockade is a potent candidate for targeting CD154/CD28 costimulation blockade-resistant memory cells [104,105], which are a major concern in clinical transplantation [106].

Of note, OX40 is constitutively expressed on both natural and induced Tregs and plays a pivotal role in Treg generation and suppressor function [107–109]. In contrast to its positive costimulatory role in effector T cells, signalling through the OX40/OX40L pathway leads to negative costimulation in Tregs. OX40 ligation leads to decreased FoxP3 expression and loss of suppressor function in vitro and in vivo [110]. Moreover, OX40 costimulation prevents the de novo induction of iTregs by TGFβ [110] and the generation of Tr1 regulatory cells [111]. Thus, OX40 signals promote effector cells and shut down regulatory T cells.

2.1.2.3. 4-1BB/4-1BBL pathway

4-1BB (CD137) is also a member of the TNFR family, primarily expressed on activated T cells [112], mediating T cell activation, differentiation and survival upon engagement [113,114]. Its ligand 4-1BBL is expressed on mature DC, activated B cells and macrophages. The 4-1BB/4-1BBL pathway is suggested to contribute to skin allograft rejection in the absence of CD28 signalling, and is critical for cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses [115,116].

The role of the 4-1BB costimulatory pathway with regard to transplantation varies between models. Blocking the 4-1BB signal with 4-1BB-Ig, anti-4-1BBL mAbs or genetic knockdown leads to prolongation of cardiac and intestinal allograft survival, whereas skin grafts are still promptly rejected [117,118]. The bulk of data suggests that 4-1BB costimulatory signals play an eminent role in CD8+ T cell mediated allograft rejection [5].

2.1.2.4. GITR/GITRL pathway

The glucocorticoid-induced TNF-R family related gene (GITR) is expressed at high levels on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells upon activation, whereas Tregs constitutively express GITR [119]. GITR is suggested to be involved in Treg survival and function as anti-GITR leads to loss of suppressive function in vitro [120,121]. In conventional T cells GITR/GITRL costimulatory signals promote T cell proliferation and cytokine production. However, its role in transplantation still needs to be clarified [122,123].

2.1.3. Cell adhesion molecules

2.1.3.1. LFA-1/ICAM pathway

Leukocyte function-associated antigen-1 (LFA-1) is a β2 integrin heterodimer consisting of the unique α chain CD11a and the common β chain CD18. LFA-1 binds to intracellular adhesion molecules, primarily ICAM-1. LFA-1 is involved in T cell trafficking, immunological synapse formation and costimulation [124]. In addition to promoting optimal T cell activation through stabilization of the T/APC contact during TCR engagement, LFA-1 appears to deliver direct costimulatory signals [125] involved in T cell activation and CTL function [126,127]. LFA-1 is also expressed on B cells [128] and upregulated on memory T cells [129], suggesting therapeutic potency in targeting CD154/CD28 costimulation blockade-resistant memory cells.

Blockade of LFA-1 (by anti-LFA-1 mAbs) synergizes with other costimulation blockers and immunosuppressive drugs in prolonging survival of islet, cardiac and skin allografts and in preventing GVHD [130–135]. An anti-LFA-1 mAb disappointed in early clinical pilot trials of adult BMT [136] and data on the efficacy in solid organ transplantation remain controversial [137,138]. A humanized anti-LFA-1 (i.e. anti-CD11a, efalizumab) mAb was effective in the treatment of psoriasis and was approved by the FDA for this indication [139,140]. Efalizumab reversibly blocks LFA-1/ICAM-1, resulting in reduced T cell activation and impaired T cell trafficking [141]. However, efalizumab was withdrawn from the market due to safety concerns [18]. Given the encouraging efficacy results of efalizumab in autoimmune disease, LFA-1 was reconsidered as therapeutic target in transplantation and LFA-1 blockade has recently been reported to prolong cardiac and islet allograft survival in NHP [142,143].

2.2. Negative costimulatory pathways

2.2.1. CTLA4/B7

CTLA4 (CD152) is a member of the Ig superfamily and shares ligands B7.1 and B7.2 (with a preference for B7.1 [144]) with the structurally related CD28, but has a 10–20-fold higher binding affinity [144]. In contrast to CD28, CTLA4 is expressed only by activated T cells, but not by naive, resting T cells [20]. However, CTLA4 is constitutively expressed at high levels by Tregs, where it is critical for their suppressive function [28,145]. Both naive CD4+CD25− T cells and memory T cells up-regulate CTLA4 upon stimulation, however expression declines rapidly in CD4+CD25− T cells [146]. Engagement of CTLA4 delivers a negative costimulatory signal (co-inhibitory signal), inhibiting TCR- and CD28-mediated signal transduction, leading to suppression of T cell activation and the induction of T cell anergy [21,25,147]. The importance of CTLA4 as central negative regulator of T cell responses is underlined by the fact that CTLA4 knockout mice rapidly die from lymphoproliferative disease due to uncontrolled B7 costimulation [148–150]. The details coordinating the balance between costimulatory signals through CD28 and CTLA4 during an immune response still need to be clarified. CTLA4 plays an important role in attenuating alloresponses and promoting tolerance induction. Importantly, an intact CTLA4 pathway is critical for tolerance induction even in the absence of a CD28/B7 costimulatory signal [5,151]. In light of this pro-tolerogenic function of CTLA4, the therapeutic use of CTLA4Ig raises concerns as it blocks a potentially beneficial CTLA4 signal through saturating B7 [20]. Indeed, blocking CTLA4 experimentally results in abrogation of tolerance, highlighting its importance for tolerance induction/maintenance [41,152]. Deliberate ligation of CTLA4 could suppress allogeneic T cell responses. However, most soluble anti-CTLA4 mAbs lack agonistic properties and rather block CTLA4 signals when used in vivo. Membrane-bound anti-CTLA4 mAbs with ligating properties resembling natural B7-1, in contrast, were effective in down-modulating allogeneic T cell responses in vivo [151].

2.2.1.1. PD-1/PD-L1/2

Programmed death-1 (PD-1) belongs to the Ig superfamily and shares homology with CTLA4 and CD28. It is inducibly expressed as monomer on activated T cells, activated B cells, NK cells and macrophages [21] and binds to PD-L1 (B7-H1) and PD-L2 (B7-DC). PD-L1 is constitutively expressed on T cells (including Tregs), B cells, myeloid cells (including mast cells) and dendritic cells and can be upregulated upon activation [153]. In contrast to B7-1/2, PD-L1 is also expressed on non-hematopoietic cells and non-lymphoid organs (heart, lung, and muscle) where it is suggested to regulate peripheral tolerance [154]. Notably, PD-L1 has recently been identified as additional ligand for B7.1 [155]. Functional studies suggested that the B7-1:PD-L1 interaction inhibits T cell proliferation and cytokine production [155]. Expression of PD-L2 is inducible by cytokines and restricted to macrophages, mast cells and dendritic cells [21]. The fact that PD-L1/2 is expressed on mast cells suggests a role for the PD-1/PD-L1/2 pathway in Treg/mast cell interactions in peripheral tolerance [156,157]. Moreover, PD-L1 promotes Treg development and function [158], implicating PD-1 as attractive therapeutic target in autoimmune diseases and tolerance induction [159]. PD-1 signals inhibit T cell activation, proliferation and cytokine production by mechanisms distinct from CTLA4 [160]. Co-localization of PD-1 and TCR/CD28 is required for PD-1 mediated inhibition and can be overcome by exogenous IL2 [161]. The importance of PD-1 as potent regulator of T and B cell responses is demonstrated by PD-1 knockout mice that develop lymphoproliferative/autoimmune disease [162,163].

The role of the PD-1/PD-L1/2 pathway in transplantation is rather complex and incompletely understood [5]. Expression of PD-1 and its ligands is upregulated in cardiac allografts during acute rejection [164]. PD-L1Ig (but not PD-L2Ig) was shown to synergize with anti-CD154 or rapamycin in preventing rejection of cardiac and islet allografts [164,165]. However, other studies have shown that PD-L1/2 can trigger stimulatory signals, which may be related to the widespread tissue expression of PD-1 ligands [5,21]. Thus, although PD-1 is a promising therapeutic target, the exact roles of PD-1 and its ligands in allograft rejection still need to be determined before its potential can be realized.

2.2.1.2. BTLA/CD160/HVEM

B and T lymphocyte attenuator (BTLA; CD272) is a member of the Ig superfamily and is expressed in the thymus and in the bone marrow during T cell and B cell development, respectively. BTLA is constitutively expressed at low levels on naïve T and B cells, NK cells, macrophages and dendritic cells and is up-regulated on activated T cells. Unlike CTLA4 and PD-L1, BTLA is not expressed on Tregs [166]. Interestingly, BTLA binds to herpes virus-entry mediator (HVEM), a member of the TNFR family expressed on activated T cells, B cells and NK cells [167,168]. The co-inhibitory signal through BTLA/HVEM suppresses T cell activation and differentiation in vitro [169], but little is currently known about its role regarding B cells and NK cells regulation.

CD160, also a new member of the Ig superfamily, is the second co-inhibitory ligand of HVEM. It is constitutively expressed in subsets of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and NKT cells and is upregulated upon activation [166,170]. Engagement of CD160 and HVEM suppresses T cell activation and proliferation upon CD3/CD28 stimulation in vitro [171]. The balance between negative costimulatory signals through BTLA/HVEM and CD160/HVEM engagement and positive costimulatory signals through LIGHT/HVEM or LTβR/HVEM contributes to allogeneic T cell regulation, however the exact mechanisms still have to be determined. Although binding affinity of HVEM is higher for LIGHT than for BTLA and CD160, co-inhibitory functions are dominant over costimulatory functions. This complex pathway highlights the importance of differences in ligand/receptor binding affinity and distinct expression patterns of these molecules in immune response regulation [170].

Targeting the BTLA/HVEM/CD80 pathway in transplantation models prolongs survival of heart [172] and islet allografts [173,174], with the outcome depending on the degree of MHC mismatch [175]. Blockade of BTLA at the time of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation prevents GVHD, but is not sufficient to reverse ongoing disease [176]. Different approaches have been employed for targeting the BTLA/HVEM/CD160 pathway including non-depleting antagonistic mAb blocking HVEM (anti-HVEM mAb, anti-LIGHT mAb, anti-LTβR), non-depleting agonistic mAbs signalling through co-inhibitory receptors (anti-BTLA mAb, anti-CD160 mAb) and depleting mAbs against CD160 and LIGHT in combination with therapies that inhibit CD4+ T cell-mediated alloresponses [166]. The therapeutic efficiency and possible interactions with other costimulatory pathways still need to be determined.

2.3. TIM family molecules

T cell immunoglobulin (Ig) and mucin domain (TIM) molecules are members of the type I transmembrane glycoprotein family. Initially, TIM molecules were identified as cell-surface proteins for differentiation between Th1 and Th2 cells, but soon they gained a lot of attention as putative therapeutic targets for immune regulation in autoimmune and allergic diseases [177,178]. The TIM family has 8 known members in mice (TIM 1–4 and putative TIM 5–8) and 3 members in humans (TIM 1, 3 and 4), all of them encoding transmembrane proteins that have an IgV domain, a mucin-like domain and a cytoplasmic tail. The TIM molecules have broad immunological functions, including T cell activation, induction of T cell apoptosis and T cell tolerance, and the capacity of APCs to clear apoptotic cells [179].

2.3.1. TIM 1/TIM 4

In mice, TIM 1 is inducibly expressed on activated CD4+ T cells. Upon differentiation only Th2 cells constitutively express TIM 1 whereas Th1 and Th17 cells lose TIM 1 expression [179,180]. TIM 1 is also expressed on mast cells [181] and some B cells [182]. Human TIM 1 was originally described as cellular receptor for hepatitis A virus (HAVCR) [183] and is also known as kidney injury molecule 1 (KIM1), which is highly upregulated after ischemia/reperfusion injury [184]. Several ligands have been identified, among them TIM 1 itself [185], TIM 4 [186], IgAλ [187] and phosphatidylserine [188]. Unlike other TIM family members, TIM 4 is constitutively expressed on APCs but not on T cells and lacks a cytoplasmic signalling motif [186]. Engagement of TIM 1 delivers costimulatory signals involved in T cell proliferation, survival and cytokine production [180]. Different TIM 1 mAbs recognizing distinct epitopes of TIM 1 as well as different binding affinities have profoundly different effects on the type of response that is induced [179]. Additionally, TIM 1 costimulation abrogates suppressor function in Tregs and reduces FoxP3 expression, thereby preventing Treg generation. As agonist anti-TIM 1 mAb enhances Th17 differentiation, TIM 1 is suggested to play a major role in regulating the balance between Tregs and Th17 cell conversion [189].

While agonist anti-TIM 1 mAbs prevent tolerance induction in an islet allograft model [189], low affinity anti-TIM mAb synergizes with rapamycin to prolong cardiac allograft survival by inhibition of the alloreactive Th1 responses [190]. TIM 1 costimulation modulates the T cell response by inducing a Th1- to Th2-type cytokine switch, and by regulating the Treg/Th17 balance, however the exact mechanisms have yet to be defined.

2.3.2. TIM 3

TIM 3 is expressed on Th1 and Th17 cells but not on resting T cells or Th2 cells [191,192]. Moreover, TIM 3 is constitutively expressed by cells of the innate immune system mast cells, macrophages and dendritic cells [193,194]. TIM 3 binds to galectin 9, which is predominantly expressed on Tregs and on naive CD4+ T cells—where it is down-regulated upon activation. Engagement of TIM 3/galectin 9 inhibits Th1 responses by induction of cell death [195] and also inhibits Th17 differentiation in vitro [196].

Blocking TIM 3 costimulation by anti-TIM 3 mAbs or TIM 3Ig accelerates the development of autoimmune disease and abrogates tolerance in islet allograft models [192]. TIM 3 signalling is suggested to play a major role in regulating allograft tolerance by negatively regulating T-cell responses.

3. Costimulatory blockade and the mixed chimerism approach

As discussed earlier, blocking the CD28 and CD40 pathways has potent immonomodulating effects but does not induce robust tolerance by itself. The use of costimulation blockers as part of mixed chimerism protocols, however, turned out to be particularly effective in promoting tolerance in stringent rodent models. Establishment of mixed chimerism through transplantation of donor bone marrow (BM) is a promising strategy for inducing transplantation tolerance, achieving permanent acceptance of fully MHC mismatched skin grafts in the experimental setting (which is commonly regarded as the most stringent test for tolerance) [197] and operational tolerance in clinical renal transplantation [198,199]. Widespread clinical application of this tolerance approach is, however, prevented by the toxicities of current BM transplantation (BMT) protocols. Since the introduction of the mixed chimerism concept with myeloablative total body irradiation (TBI) [200] and global T cell depletion [201,202], gradual progress has been made towards the development of minimally toxic conditioning regimens [203]. The introduction of costimulation blockers as a component of BMT protocols was a major step closer to this goal, allowing a drastic reduction of recipient conditioning by obviating the need for global destruction of the pre-existing recipient T cell repertoire [204,205]. Subsequently, protocols devoid of recipient irradiation [206,207] and even devoid of any cytotoxic conditioning became possible with the use of costimulation blockers [208]. Numerous such BMT protocols have since been developed, employing anti-CD154 mAbs with or without CTLA4Ig. In attempts to minimize cytotoxic recipient conditioning several adjunctive treatments were identified that promote BM engraftment under minimal conditioning in costimulation blocker-treated BMT recipients, including the use of facilitating cells, DST, non-depleting anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 mAbs, rapamycin, NK cell depletion and Treg treatment (reviewed in detail in [203,209]).

Central clonal deletion was recognized as a cardinal tolerance mechanism in mixed chimerism a long time ago and has remained a key mechanism also in protocols using costimulation blockers [210]. Since costimulation blockers allow BMT in recipients in which the pre-existing T cell repertoire was for the first time left largely intact, mechanisms of peripheral tolerance need to effectively control mature donor-reactive T cells in these systems. Progressive peripheral clonal deletion of mature donor-reactive CD4 [211] and CD8 [212] T cells was identified as the main mechanism of peripheral tolerance in such chimeras [205,213]. Deletion shows features of both activation-induced cell death and passive cell death [213], but the molecular details of this powerful tolerance mechanism that clonally eliminates mature donor-reactive T cells remain incompletely understood to this day. PD-1/PD-L1 is essential for CD8 but not CD4 T cell tolerance [214] as cell intrinsic PD-1 and either CTLA4 or B7-1/2 are required by CD8 (but not CD4) T cells [215]. While CD28 signalling is not required for tolerance induction in this model, an early cell intrinsic CTLA4 signal is critical for CD4 tolerance [216]. Non-deletional, regulatory mechanisms also contribute to peripheral tolerance [217], but their relative importance depends on the degree of recipient conditioning, with regulation becoming more important with minimal conditioning [208,218,219].

The induction of chimerism and tolerance is markedly more difficult to achieve in large animals/NHP than in rodents, requiring more extensive recipient conditioning. In a DLI-identical canine BMT model, CTLA4Ig [220] and anti-CD154 mAb (together with DST) [221] improved BM engraftment, allowing the dose of total body irradiation to be reduced (tolerance was not tested). In an irradiation-based non-myeloablative NHP model of kidney allograft tolerance, adjunctive anti-CD154 mAb treatment enhanced chimerism and obviated the need for splenectomy, but did not obviate the need for T cell depletion [222]. Of note, while stable chimerism is necessary for the induction of skin graft tolerance in mice, transient chimerism in combination with kidney transplantation is sufficient to promote renal allograft tolerance in certain NHP systems [222–224] and in patients [199,225], indicating that the tolerance mechanisms differ significantly between these two settings. This difference might be explained at least in part through the fact that the kidney graft itself seems to participate in tolerance induction in NHP and humans [226]. In another NHP BMT model employing non-myeloablative doses of busulfan, costimulation blockade with anti-CD154 mAb plus belatacept, together with basiliximab and sirolimus, led to remarkably high levels of chimerism and a median chimerism duration of >4 months (no organ transplants were preformed in this study) [227]. More recently, new MHC typing technologies became available in this rhesus macaque model allowing the investigation of defined MHC barriers [228]. Unexpectedly, donor BM was rejected after withdrawal of immunosuppression/costimulation blockade even in the MHC-matched situation (and also in the one haplotype-mismatched setting). Pre-existing non-tolerized donor-reactive T cells appear to be mainly responsible for BM rejection, although the mechanisms of this resistance towards costimulation blockade and mixed chimerism remain undefined. As no organs were transplanted, it is unclear whether or not operational tolerance towards a kidney graft would have been achieved with this regimen inducing transient chimerism. Thus, costimulation blockers are effective in large animal models of mixed chimerism, but considerably less so than in rodent models, necessitating more extensive recipient conditioning.

4. Clinical translation of costimulatory blockade

Once it became apparent in the NHP setting that costimulation blockade does not induce tolerance by itself, attention shifted to employing costimulation blockers as immunosuppressive drug therapy. As mentioned earlier, development of anti-CD40L mAbs had to be stopped due to thromboembolic events and no data are yet available for the clinical use of anti-CD40 mAbs as possible alternative. Similarly, efalizumab (anti-LFA), which had been approved for the treatment of psoriasis, is no longer on the market. Thus, belatacept is currently the only costimulation blocker in an advanced stage of clinical development for use in organ transplant recipients.

Results from phase II and phase III renal transplant trials have been reported with belatacept [36,37,229–231]. Collectively, the obtained data demonstrate that belatacept is effective as primary immunosuppressant (i.e. it does not require concomitant use of calcineurin inhibitors). Graft and patient survival in belatacept patients were comparable to those receiving cyclosporine. Notably, renal function at 1 and 2 years post-transplant was significantly better with belatacept compared to cyclosporine. However, episodes of acute rejection were more frequent in belatacept patients. Paradoxically, the incidence of acute rejection was higher in the group treated with a higher dose of belatacept than in the one treated with a lower dose (two dosing regimens were compared) [37]. While the specific cause for these observations is presently unknown, the current understanding of the complexities of the CD28/B7 pathway offers some potential explanations. It is conceivable that at higher concentrations B7 occupation by belatacept reaches a level that interferes with inhibitory signals through CTLA4 and/or PDL-1 which are important regulatory mechanisms fostering graft acceptance [5,63,155,232]. Moreover, T regulatory cells might be impeded twofold, through the abrogation of CD28 signals and the inhibition of CTLA4 function. As CD28 signals suppress Th17 differentiation, CD28 blockade through belatacept might also drive Th17 development [233]. Regarding safety aspects, the side effects of belatacept were limited to the immune system without off-target toxicities, which are a major morbidity factor with calcineurin inhibitors. Like any non-specific immunosuppression, however, belatacept was associated with increased risks of infections and tumors. Of particular concern is the high incidence of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders (PTLD), including an unusually high number of cases with CNS involvement, that was observed with belatacept, in particular in Epstein–Barr virus serology negative recipients [37].

Thus, it is hoped that the costimulation blocker Belatacept will be approved as an immunosuppressant for use in kidney transplantation. The FDA however has expressed concerns about the high incidence of vascular rejection and occurrence of PTLD especially in the brain and thus has delayed its decision until clinical data at 3 years is presented. Despite these concerns the advantages of the use of this agent will hopefully allow approval which will reduce the dependence on CNI use. It remains to be seen whether belatacept-based protocols – likely involving additional biologicals [52] – can be developed which allow minimization or even controlled withdrawal of immunosuppression.

5. Conclusion

It is firmly established that costimulatory signals are critical for the regulation of allo-immune responses and that their modulation represents a potent tool for preventing allograft rejection and potentially even for the induction of tolerance. However, recent advances in the field revealed that costimulation pathways are a complex network of numerous positive and negative, time-dependent and partially redundant signals whose effect also depends on the specific subset of T cells they affect. Although the therapeutic exploitation of costimulation blockade has consequently become more difficult to realize than initially envisioned, the costimulation blocker CTLA4Ig/belatacept is close to clinical approval as immunosuppressive drug and offers hope that other biologicals modulating T cell costimulation will follow.

Acknowledgements

Some of the work described in this review was supported by a research grant from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF, TRP151-B19 to T.W.) and by NIAID RO1 AI 51559 and R01 AI 070820-01A1 for MHS.

References

- 1.Lamb K.E., Lodhi S., Meier-Kriesche H.U. Long-term renal allograft survival in the United States: a critical reappraisal. Am J Transplant. 2010;11:450–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenberg A.S., Mizuochi T., Sharrow S.O., Singer A. Phenotype, specificity, and function of T cell subsets and T cell interactions involved in skin allograft rejection. J Exp Med. 1987;165:1296–1315. doi: 10.1084/jem.165.5.1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lafferty K.J., Cunningham A.J. A new analysis of allogeneic interactions. Aust J Exp Biol Med Sci. 1975;53:27–42. doi: 10.1038/icb.1975.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jenkins M.K., Schwartz R.H. Antigen presentation by chemically modified splenocytes induces antigen-specific T cell unresponsiveness in vitro and in vivo. J Exp Med. 1987;165:302–319. doi: 10.1084/jem.165.2.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li X.C., Rothstein D.M., Sayegh M.H. Costimulatory pathways in transplantation: challenges and new developments. Immunol Rev. 2009;229:271–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sayegh M.H., Turka L.A. The role of T-cell costimulatory activation pathways in transplant rejection. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1813–1821. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199806183382506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pree I., Wekerle T. New approaches to prevent transplant rejection: co-stimulation blockers anti-CD40L and CTLA4Ig. Drug Discov Today. 2006;3:41–47. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mueller D.L. Mechanisms maintaining peripheral tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:21–27. doi: 10.1038/ni.1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wekerle T., Kurtz J., Bigenzahn S., Takeuchi Y., Sykes M. Mechanisms of transplant tolerance induction using costimulatory blockade. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14:592–600. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00378-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larsen C.P., Elwood E.T., Alexander D.Z., Ritchie S.C., Hendrix R., Tucker-Burden C. Long-term acceptance of skin and cardiac allografts after blocking CD40 and CD28 pathwys. Nature. 1996;381:434–438. doi: 10.1038/381434a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sayegh M.H., Zheng X.G., Magee C., Hancock W.W., Turka L.A. Donor antigen is necessary for the prevention of chronic rejection in CTLA4Ig-treated murine cardiac allograft recipients. Transplantation. 1997;64:1646–1650. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199712270-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirk A.D., Harlan D.M., Armstrong N.N., Davis T.A., Dong Y., Gray G.S. CTLA4-Ig and anti-CD40 ligand prevent renal allograft rejection in primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:8789–8794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirk A.D., Burkly L.C., Batty D.S., Baumgartner R.E., Berning J.D., Buchanan K. Treatment with humanized monoclonal antibody against CD154 prevents acute renal allograft rejection in nonhuman primates. Nat Med. 1999;5:686–693. doi: 10.1038/9536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu H., Tadaki D.K., Elster E.A., Burkly L.C., Berning J.D., Cruzata F. Humanized anti-CD154 antibody therapy for the treatment of allograft rejection in nonhuman primates. Transplantation. 2002;74:940–943. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200210150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kean L.S., Gangappa S., Pearson T.C., Larsen C.P. Transplant tolerance in non-human primates: progress, current challenges and unmet needs. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:884–893. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larsen C.P., Knechtle S.J., Adams A., Pearson T., Kirk A.D. A new look at blockade of T-cell costimulation: a therapeutic strategy for long-term maintenance immunosuppression. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:876–883. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valujskikh A., Pantenburg B., Heeger P.S. Primed allospecific T cells prevent the effects of costimulatory blockade on prolonged cardiac allograft survival in mice. Am J Transplant. 2002;2:501–509. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2002.20603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ford M.L., Larsen C.P. Translating costimulation blockade to the clinic: lessons learned from three pathways. Immunol Rev. 2009;229:294–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00776.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paterson A.M., Vanguri V.K., Sharpe A.H. SnapShot: B7/CD28 costimulation. Cell. 2009;137:974–1974. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salomon B., Bluestone J.A. Complexities of CD28/B7: CTLA-4 costimulatory pathways in autoimmunity and transplantation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:225–252. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenwald R.J., Freeman G.J., Sharpe A.H. The B7 family revisited. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:515–548. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halloran P.F. Immunosuppressive drugs for kidney transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2715–2729. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra033540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwartz R.H. A cell culture model for T lymphocyte clonal anergy. Science (New York, NY) 1990;248:1349–1356. doi: 10.1126/science.2113314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwartz R.H. T cell anergy. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:305–334. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walunas T.L., Lenschow D.J., Bakker C.Y., Linsley P.S., Freeman G.J., Green J.M. CTLA-4 can function as a negative regulator of T cell activation. Immunity. 1994;1:405–413. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson C.B., Allison J.P. The emerging role of CTLA-4 as an immune attenuator. Immunity. 1997;7:445–450. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80366-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sakaguchi S., Ono M., Setoguchi R., Yagi H., Hori S., Fehervari Z. Foxp3+ CD25+ CD4+ natural regulatory T cells in dominant self-tolerance and autoimmune disease. Immunol Rev. 2006;212:8–27. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wing K., Onishi Y., Prieto-Martin P., Yamaguchi T., Miyara M., Fehervari Z. CTLA-4 control over Foxp3+ regulatory T cell function. Science (New York, NY) 2008;322:271–275. doi: 10.1126/science.1160062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oderup C., Cederbom L., Makowska A., Cilio C.M., Ivars F. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4-dependent down-modulation of costimulatory molecules on dendritic cells in CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T-cell-mediated suppression. Immunology. 2006;118:240–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02362.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grohmann U., Orabona C., Fallarino F., Vacca C., Calcinaro F., Falorni A. CTLA-4-Ig regulates tryptophan catabolism in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:1097–1101. doi: 10.1038/ni846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Linsley P.S., Wallace P.M., Johnson J., Gibson M.G., Greene J.L., Ledbetter J.A. Immunosuppression in vivo by a soluble form of the CTLA-4 T cell activation molecule. Science (New York, NY) 1992;257:792–795. doi: 10.1126/science.1496399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Linsley P.S., Greene J.L., Brady W., Bajorath J., Ledbetter J.A., Peach R. Human B7-1 (CD80) and B7-2 (CD86) bind with similar avidities but distinct kinetics to CD28 and CTLA-4 receptors. Immunity. 1994;1:793–801. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(94)80021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bluestone J.A., St Clair E.W., Turka L.A. CTLA4Ig: bridging the basic immunology with clinical application. Immunity. 2006;24:233–238. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kremer J.M., Westhovens R., Leon M., Di Giorgio E., Alten R., Steinfeld S. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis by selective inhibition of T-cell activation with fusion protein CTLA4Ig. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1907–1915. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Larsen C.P., Pearson T.C., Adams A.B., Tso P., Shirasugi N., Strobert E. Rational development of LEA29Y (belatacept), a high-affinity variant of CTLA4-Ig with potent immunosuppressive properties. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:443–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vincenti F., Larsen C., Durrbach A., Wekerle T., Nashan B., Blancho G. Costimulation blockade with belatacept in renal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:770–781. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vincenti F., Charpentier B., Vanrenterghem Y., Rostaing L., Bresnahan B., Darji P. A phase III study of belatacept-based immunosuppression regimens versus cyclosporine in renal transplant recipients (BENEFIT study) Am J Transplant. 2010;10:535–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.03005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kirk A.D., Tadaki D.K., Celniker A., Batty D.S., Berning J.D., Colonna J.O. Induction therapy with monoclonal antibodies specific for CD80 and CD86 delays the onset of acute renal allograft rejection in non-human primates. Transplantation. 2001;72:377–384. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200108150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Birsan T., Hausen B., Higgins J.P., Hubble R.W., Klupp J., Stalder M. Treatment with humanized monoclonal antibodies against CD80 and CD86 combined with sirolimus prolongs renal allograft survival in cynomolgus monkeys. Transplantation. 2003;75:2106–2113. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000066806.10029.7A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vincenti F. What's in the pipeline? New immunosuppressive drugs in transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2002;2:898–903. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2002.21005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perez V.L., Van Parijs L., Biuckians A., Zheng X.X., Strom T.B., Abbas A.K. Induction of peripheral T cell tolerance in vivo requires CTLA-4 engagement. Immunity. 1997;6:411–417. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pearson T.C., Alexander D.Z., Winn K.J., Linsley P.S., Lowry R.P., Larsen C.P. Transplantation tolerance induced by CTLA4-Ig. Transplantation. 1994;57:1701–1706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin H., Bolling S.F., Linsley P.S., Wei R.Q., Gordon D., Thompson C.B. Long-term acceptance of major histocompatibility complex mismatched cardiac allografts induced by CTLA4Ig plus donor-specific transfusion. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1801–1806. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.5.1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baliga P., Chavin K.D., Qin L., Woodward J., Lin J., Linsley P.S. CTLA4Ig prolongs allograft survival while suppressing cell-mediated immunity. Transplantation. 1994;58:1082–1090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Turka L.A., Linsley P.S., Lin H., Brady W., Leiden J.M., Wei R.Q. T-cell activation by the CD28 ligand B7 is required for cardiac allograft rejection in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:11102–11105. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.11102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lenschow D.J., Zeng Y., Thistlethwaite J.R., Montag A., Brady W., Gibson M.G. Long-term survival of xenogeneic pancreatic islet grafts induced by CTLA4lg. Science (New York, NY) 1992;257:789–792. doi: 10.1126/science.1323143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Azuma H., Chandraker A., Nadeau K., Hancock W.W., Carpenter C.B., Tilney N.L. Blockade of T-cell costimulation prevents development of experimental chronic renal allograft rejection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12439–12444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chandraker A., Azuma H., Nadeau K., Carpenter C.B., Tilney N.L., Hancock W.W. Late blockade of T cell costimulation interrupts progression of experimental chronic allograft rejection. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2309–2318. doi: 10.1172/JCI2299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cavinato R.A., Casiraghi F., Azzollini N., Cassis P., Cugini D., Mister M. Pretransplant donor peripheral blood mononuclear cells infusion induces transplantation tolerance by generating regulatory T cells. Transplantation. 2005;79:1034–1039. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000161663.64279.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Judge T.A., Tang A., Spain L.M., Deans-Gratiot J., Sayegh M.H., Turka L.A. The in vivo mechanism of action of CTLA4Ig. J Immunol. 1996;156:2294–2299. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Levisetti M.G., Padrid P.A., Szot G.L., Mittal N., Meehan S.M., Wardrip C.L. Immunosuppressive effects of human CTLA4Ig in a non-human primate model of allogeneic pancreatic islet transplantation. J Immunol. 1997;159:5187–5191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weaver T.A., Charafeddine A.H., Agarwal A., Turner A.P., Russell M., Leopardi F.V. Alefacept promotes co-stimulation blockade based allograft survival in nonhuman primates. Nat Med. 2009;15:746–749. doi: 10.1038/nm.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lo D.J., Weaver T.A., Stempora L., Mehta A.K., Ford M.L., Larsen C.P. Selective targeting of human alloresponsive CD8+ effector memory T cells based on CD2 expression. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:22–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03317.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Poirier N., Blancho G., Vanhove B. A more selective costimulatory blockade of the CD28–B7 pathway. Transpl Int. 2011;24:2–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2010.01176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lin C.H., Hunig T. Efficient expansion of regulatory T cells in vitro and in vivo with a CD28 superagonist. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:626–638. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hunig T. Manipulation of regulatory T-cell number and function with CD28-specific monoclonal antibodies. Adv Immunol. 2007;95:111–148. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(07)95004-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Beyersdorf N., Gaupp S., Balbach K., Schmidt J., Toyka K.V., Lin C.H. Selective targeting of regulatory T cells with CD28 superagonists allows effective therapy of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 2005;202:445–455. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Beyersdorf N., Ding X., Hunig T., Kerkau T. Superagonistic CD28 stimulation of allogeneic T cells protects from acute graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2009;114:4575–4582. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-218248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Haspot F., Seveno C., Dugast A.S., Coulon F., Renaudin K., Usal C. Anti-CD28 antibody-induced kidney allograft tolerance related to tryptophan degradation and TCR class II B7 regulatory cells. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:2339–2348. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Laskowski I.A., Pratschke J., Wilhelm M.J., Dong V.M., Beato F., Taal M. Anti-CD28 monoclonal antibody therapy prevents chronic rejection of renal allografts in rats. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:519–527. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V132519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Suntharalingam G., Perry M.R., Ward S., Brett S.J., Castello-Cortes A., Brunner M.D. Cytokine storm in a phase 1 trial of the anti-CD28 monoclonal antibody TGN1412. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1018–1028. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gogishvili T., Langenhorst D., Luhder F., Elias F., Elflein K., Dennehy K.M. Rapid regulatory T-cell response prevents cytokine storm in CD28 superagonist treated mice. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4643. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Poirier N., Azimzadeh A.M., Zhang T., Dilek N., Mary C., Nguyen B. Inducing CTLA-4-dependent immune regulation by selective CD28 blockade promotes regulatory T cells in organ transplantation. Sci Transl Med. 2010:2. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hutloff A., Dittrich A.M., Beier K.C., Eljaschewitsch B., Kraft R., Anagnostopoulos I. ICOS is an inducible T-cell co-stimulator structurally and functionally related to CD28. Nature. 1999;397:263–266. doi: 10.1038/16717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Coyle A.J., Lehar S., Lloyd C., Tian J., Delaney T., Manning S. The CD28-related molecule ICOS is required for effective T cell-dependent immune responses. Immunity. 2000;13:95–105. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Okazaki T., Iwai Y., Honjo T. New regulatory co-receptors: inducible co-stimulator and PD-1. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14:779–782. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00398-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tafuri A., Shahinian A., Bladt F., Yoshinaga S.K., Jordana M., Wakeham A. ICOS is essential for effective T-helper-cell responses. Nature. 2001;409:105–109. doi: 10.1038/35051113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Richter G., Hayden-Ledbetter M., Irgang M., Ledbetter J.A., Westermann J., Korner I. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha regulates the expression of inducible costimulator receptor ligand on CD34(+) progenitor cells during differentiation into antigen presenting cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:45686–45693. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108509200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Harada H., Salama A.D., Sho M., Izawa A., Sandner S.E., Ito T. The role of the ICOS–B7h T cell costimulatory pathway in transplantation immunity. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:234–243. doi: 10.1172/JCI17008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dong C., Juedes A.E., Temann U.A., Shresta S., Allison J.P., Ruddle N.H. ICOS co-stimulatory receptor is essential for T-cell activation and function. Nature. 2001;409:97–101. doi: 10.1038/35051100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kopf M., Coyle A.J., Schmitz N., Barner M., Oxenius A., Gallimore A. Inducible costimulator protein (ICOS) controls T helper cell subset polarization after virus and parasite infection. J Exp Med. 2000;192:53–61. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ozkaynak E., Gao W., Shemmeri N., Wang C., Gutierrez-Ramos J.C., Amaral J. Importance of ICOS–B7RP-1 costimulation in acute and chronic allograft rejection. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:591–596. doi: 10.1038/89731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kosuge H., Suzuki J., Gotoh R., Koga N., Ito H., Isobe M. Induction of immunologic tolerance to cardiac allograft by simultaneous blockade of inducible co-stimulator and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 pathway. Transplantation. 2003;75:1374–1379. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000061601.26325.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Larsen C.P., Pearson T.C. The CD40 pathway in allograft rejection, acceptance, and tolerance. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:641–647. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80043-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.van Kooten C., Banchereau J. Functions of CD40 on B cells, dendritic cells and other cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:330–337. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Blair P.J., Riley J.L., Harlan D.M., Abe R., Tadaki D.K., Hoffmann S.C. CD40 ligand (CD154) triggers a short-term CD4(+) T cell activation response that results in secretion of immunomodulatory cytokines and apoptosis. J Exp Med. 2000;191:651–660. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.4.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Waldmann H. The new immunosuppression: just kill the T cell. Nat Med. 2003;9:1259–1260. doi: 10.1038/nm1003-1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mai G., Bucher P., Morel P., Mei J., Bosco D., Andres A. Anti-CD154 mAb treatment but not recipient CD154 deficiency leads to long-term survival of xenogeneic islet grafts. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:1021–1031. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kurtz J., Ito H., Wekerle T., Shaffer J., Sykes M. Mechanisms involved in the establishment of tolerance through costimulatory blockade and BMT: lack of requirement for CD40L-mediated signaling for tolerance or deletion of donor-reactive CD4+ cells. Am J Transplant. 2001;1:339–349. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2001.10409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Monk N.J., Hargreaves R.E., Marsh J.E., Farrar C.A., Sacks S.H., Millrain M. Fc-dependent depletion of activated T cells occurs through CD40L-specific antibody rather than costimulation blockade. Nat Med. 2003;9:1275–1280. doi: 10.1038/nm931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Conley M.E., Larche M., Bonagura V.R., Lawton A.R., 3rd, Buckley R.H., Fu S.M. Hyper IgM syndrome associated with defective CD40-mediated B cell activation. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:1404–1409. doi: 10.1172/JCI117476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Peters A.L., Stunz L.L., Bishop G.A. CD40 and autoimmunity: the dark side of a great activator. Semin Immunol. 2009;21:293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Quezada S.A., Jarvinen L.Z., Lind E.F., Noelle R.J. CD40/CD154 interactions at the interface of tolerance and immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:307–328. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shimizu K., Schonbeck U., Mach F., Libby P., Mitchell R.N. Host CD40 ligand deficiency induces long-term allograft survival and donor-specific tolerance in mouse cardiac transplantation but does not prevent graft arteriosclerosis. J Immunol. 2000;165:3506–3518. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.3506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Guillot C., Guillonneau C., Mathieu P., Gerdes C.A., Menoret S., Braudeau C. Prolonged blockade of CD40–CD40 ligand interactions by gene transfer of CD40Ig results in long-term heart allograft survival and donor-specific hyporesponsiveness, but does not prevent chronic rejection. J Immunol. 2002;168:1600–1609. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.4.1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Xu H., Montgomery S.P., Preston E.H., Tadaki D.K., Hale D.A., Harlan D.M. Studies investigating pretransplant donor-specific blood transfusion, rapamycin, and the CD154-specific antibody IDEC-131 in a nonhuman primate model of skin allotransplantation. J Immunol. 2003;170:2776–2782. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.5.2776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Trambley J., Bingaman A.W., Lin A., Elwood E.T., Waitze S.Y., Ha J. Asialo GM1(+) CD8(+) T cells play a critical role in costimulation blockade-resistant allograft rejection. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:1715–1722. doi: 10.1172/JCI8082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Williams M.A., Trambley J., Ha J., Adams A.B., Durham M.M., Rees P. Genetic characterization of strain differences in the ability to mediate CD40/CD28-independent rejection of skin allografts. J Immunol. 2000;165:6849–6857. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.6849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kenyon N.S., Fernandez L.A., Lehmann R., Masetti M., Ranuncoli A., Chatzipetrou M. Long-term survival and function of intrahepatic islet allografts in baboons treated with humanized anti-CD154. Diabetes. 1999;48:1473–1481. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.7.1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sidiropoulos P.I., Boumpas D.T. Lessons learned from anti-CD40L treatment in systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Lupus. 2004;13:391–397. doi: 10.1191/0961203304lu1032oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kawai T., Andrews D., Colvin R.B., Sachs D.H., Cosimi A.B. Thromboembolic complications after treatment with monoclonal antibody against CD40 ligand. Nat Med. 2000;6:114. doi: 10.1038/72162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Andre P., Prasad K.S., Denis C.V., He M., Papalia J.M., Hynes R.O. CD40L stabilizes arterial thrombi by a beta3 integrin-dependent mechanism. Nat Med. 2002;8:247–252. doi: 10.1038/nm0302-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Adams A.B., Shirasugi N., Jones T.R., Durham M.M., Strobert E.A., Cowan S. Development of a chimeric anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody that synergizes with LEA29Y to prolong islet allograft survival. J Immunol. 2005;174:542–550. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.1.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gilson C.R., Milas Z., Gangappa S., Hollenbaugh D., Pearson T.C., Ford M.L. Anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody synergizes with CTLA4-Ig in promoting long-term graft survival in murine models of transplantation. J Immunol. 2009;183:1625–1635. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gramaglia I., Weinberg A.D., Lemon M., Croft M. Ox-40 ligand: a potent costimulatory molecule for sustaining primary CD4 T cell responses. J Immunol. 1998;161:6510–6517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rogers P.R., Song J., Gramaglia I., Killeen N., Croft M. OX40 promotes Bcl-xL and Bcl-2 expression and is essential for long-term survival of CD4 T cells. Immunity. 2001;15:445–455. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00191-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Stuber E., Strober W. The T cell–B cell interaction via OX40–OX40L is necessary for the T cell-dependent humoral immune response. J Exp Med. 1996;183:979–989. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Walker L.S., Gulbranson-Judge A., Flynn S., Brocker T., Raykundalia C., Goodall M. Compromised OX40 function in CD28-deficient mice is linked with failure to develop CXC chemokine receptor 5-positive CD4 cells and germinal centers. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1115–1122. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.8.1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lane P. Role of OX40 signals in coordinating CD4 T cell selection, migration, and cytokine differentiation in T helper (Th)1 and Th2 cells. J Exp Med. 2000;191:201–206. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.2.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sugamura K., Ishii N., Weinberg A.D. Therapeutic targeting of the effector T-cell co-stimulatory molecule OX40. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:420–431. doi: 10.1038/nri1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Demirci G., Amanullah F., Kewalaramani R., Yagita H., Strom T.B., Sayegh M.H. Critical role of OX40 in CD28 and CD154-independent rejection. J Immunol. 2004;172:1691–1698. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.3.1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yuan X., Salama A.D., Dong V., Schmitt I., Najafian N., Chandraker A. The role of the CD134–CD134 ligand costimulatory pathway in alloimmune responses in vivo. J Immunol. 2003;170:2949–2955. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.2949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Dawicki W., Bertram E.M., Sharpe A.H., Watts T.H. 4-1BB and OX40 act independently to facilitate robust CD8 and CD4 recall responses. J Immunol. 2004;173:5944–5951. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.10.5944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Gudmundsdottir H., Turka L.A. A closer look at homeostatic proliferation of CD4+ T cells: costimulatory requirements and role in memory formation. J Immunol. 2001;167:3699–3707. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.7.3699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wu Z., Bensinger S.J., Zhang J., Chen C., Yuan X., Huang X. Homeostatic proliferation is a barrier to transplantation tolerance. Nat Med. 2004;10:87–92. doi: 10.1038/nm965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Koehn B., Gangappa S., Miller J.D., Ahmed R., Larsen C.P. Patients, pathogens, and protective immunity: the relevance of virus-induced alloreactivity in transplantation. J Immunol. 2006;176:2691–2696. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.5.2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.So T., Croft M. Cutting edge: OX40 inhibits TGF-beta- and antigen-driven conversion of naive CD4 T cells into CD25+Foxp3+ T cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:1427–1430. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Gri G., Piconese S., Frossi B., Manfroi V., Merluzzi S., Tripodo C. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells suppress mast cell degranulation and allergic responses through OX40–OX40L interaction. Immunity. 2008;29:771–781. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Valzasina B., Guiducci C., Dislich H., Killeen N., Weinberg A.D., Colombo M.P. Triggering of OX40 (CD134) on CD4(+)CD25+ T cells blocks their inhibitory activity: a novel regulatory role for OX40 and its comparison with GITR. Blood. 2005;105:2845–2851. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Vu M.D., Xiao X., Gao W., Degauque N., Chen M., Kroemer A. OX40 costimulation turns off Foxp3+ Tregs. Blood. 2007;110:2501–2510. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-070748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ito T., Wang Y.H., Duramad O., Hanabuchi S., Perng O.A., Gilliet M. OX40 ligand shuts down IL-10-producing regulatory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13138–13143. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603107103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Adams A.B., Larsen C.P., Pearson T.C., Newell K.A. The role of TNF receptor and TNF superfamily molecules in organ transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2002;2:12–18. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2002.020104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Cannons J.L., Lau P., Ghumman B., DeBenedette M.A., Yagita H., Okumura K. 4-1BB ligand induces cell division, sustains survival, and enhances effector function of CD4 and CD8 T cells with similar efficacy. J Immunol. 2001;167:1313–1324. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Vinay D.S., Kwon B.S. Role of 4-1BB in immune responses. Semin Immunol. 1998;10:481–489. doi: 10.1006/smim.1998.0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.DeBenedette M.A., Wen T., Bachmann M.F., Ohashi P.S., Barber B.H., Stocking K.L. Analysis of 4-1BB ligand (4-1BBL)-deficient mice and of mice lacking both 4-1BBL and CD28 reveals a role for 4-1BBL in skin allograft rejection and in the cytotoxic T cell response to influenza virus. J Immunol. 1999;163:4833–4841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Cooper D., Bansal-Pakala P. Croft M. 4-1BB (CD137) controls the clonal expansion and survival of CD8 T cells in vivo but does not contribute to the development of cytotoxicity. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:521–529. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200202)32:2<521::AID-IMMU521>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wang J., Guo Z., Dong Y., Kim O., Hart J., Adams A. Role of 4-1BB in allograft rejection mediated by CD8+ T cells. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:543–551. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2003.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Cho H.R., Kwon B., Yagita H., La S., Lee E.A., Kim J.E. Blockade of 4-1BB (CD137)/4-1BB ligand interactions increases allograft survival. Transpl Int. 2004;17:351–361. doi: 10.1007/s00147-004-0726-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Shimizu J., Yamazaki S., Takahashi T., Ishida Y., Sakaguchi S. Stimulation of CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory T cells through GITR breaks immunological self-tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:135–142. doi: 10.1038/ni759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Durrbach A., Francois H., Jacquet A., Beaudreuil S., Charpentier B. Co-signals in organ transplantation. Curr Opin Org Transplant. 2010;15:474–480. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e32833c1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kanamaru F., Youngnak P., Hashiguchi M., Nishioka T., Takahashi T., Sakaguchi S. Costimulation via glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor in both conventional and CD25+ regulatory CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2004;172:7306–7314. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Gravestein L.A., Borst J. Tumor necrosis factor receptor family members in the immune system. Semin Immunol. 1998;10:423–434. doi: 10.1006/smim.1998.0144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ronchetti S., Zollo O., Bruscoli S., Agostini M., Bianchini R., Nocentini G. GITR, a member of the TNF receptor superfamily, is costimulatory to mouse T lymphocyte subpopulations. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:613–622. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Nicolls M.R., Gill R.G. LFA-1 (CD11a) as a therapeutic target. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:27–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Shimizu Y. LFA-1: more than just T cell Velcro. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1052–1054. doi: 10.1038/ni1103-1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Van Seventer G.A., Shimizu Y., Horgan K.J., Shaw S. The LFA-1 ligand ICAM-1 provides an important costimulatory signal for T cell receptor-mediated activation of resting T cells. J Immunol. 1990;144:4579–4586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Cai Z., Brunmark A., Jackson M.R., Loh D., Peterson P.A., Sprent J. Transfected Drosophila cells as a probe for defining the minimal requirements for stimulating unprimed CD8+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14736–14741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Owens T. A role for adhesion molecules in contact-dependent T help for B cells. Eur J Immunol. 1991;21:979–983. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830210418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Sanders M.E., Makgoba M.W., Sharrow S.O., Stephany D., Springer T.A., Young H.A. Human memory T lymphocytes express increased levels of three cell adhesion molecules (LFA-3, CD2, and LFA-1) and three other molecules (UCHL1, CDw29, and Pgp-1) and have enhanced IFN-gamma production. J Immunol. 1988;140:1401–1407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Metzler B., Gfeller P., Bigaud M., Li J., Wieczorek G., Heusser C. Combinations of anti-LFA-1, everolimus, anti-CD40 ligand, and allogeneic bone marrow induce central transplantation tolerance through hemopoietic chimerism, including protection from chronic heart allograft rejection. J Immunol. 2004;173:7025–7036. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.11.7025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Rayat G.R., Gill R.G. Indefinite survival of neonatal porcine islet xenografts by simultaneous targeting of LFA-1 and CD154 or CD45RB. Diabetes. 2005;54:443–451. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.2.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Nicolls M.R., Coulombe M., Yang H., Bolwerk A., Gill R.G. Anti-LFA-1 therapy induces long-term islet allograft acceptance in the absence of IFN-gamma or IL-4. J Immunol. 2000;164:3627–3634. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.7.3627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Isobe M., Yagita H., Okumura K., Ihara A. Specific acceptance of cardiac allograft after treatment with antibodies to ICAM-1 and LFA-1. Science (New York, NY) 1992;255:1125–1127. doi: 10.1126/science.1347662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]