Abstract

The high prevalence of child under-nutrition remains a profound challenge in the developing world. Maternal autonomy was examined as a determinant of breast feeding and infant growth in children 3 to 5 months of age. Cross-sectional baseline data on 600 mother-infant pairs were collected in 60 villages in rural Andhra Pradesh, India. The mothers were enrolled in a longitudinal randomized behavioral intervention trial. In addition to anthropometric and demographic measures, an autonomy questionnaire was administered to measure different dimensions of autonomy (e.g. decision-making, freedom of movement, financial autonomy, and acceptance of domestic violence). We conducted confirmatory factor analysis on maternal autonomy items and regression analyses on infant breast feeding and growth after adjusting for socioeconomic and demographic variables, and accounting for infant birth weight, infant morbidity, and maternal nutritional status. Results indicated that mothers with higher financial autonomy were more likely to breastfeed 3–5 month old infants. Mothers with higher participation in decision-making in households had infants that were less underweight and less wasted. These results suggest that improving maternal financial and decision-making autonomy could have a positive impact on infant feeding and growth outcomes.

Keywords: infant feeding, infant growth, maternal autonomy, confirmatory factor analysis, India, nutrition, mothers

Introduction

Child malnutrition and related morbidity and mortality are continuing challenges faced throughout the developing world. India, a country with a population of more than one billion, has one of the highest rates of undernourished children in the world: 48% of children under 5 years of age are short for their age (stunted) and 43% children are underweight (International Institute for Population Sciences and ORC Macro, 2007).

The literature identifies several determinants (inadequate dietary intake, infection & acute illness, lack of health services, and social and economic factors) of poor infant and child nutritional status (Black et al., 2008; Frongillo et al., 1997). Within the household, the role of the mother in child feeding is central. Variables associated with maternal status, such as education, are associated with child survival (Cleland, 2010) and child nutritional status (Frost et al., 2005). Mothers with more education are also more likely to have children with better growth (Basu & Stephenson, 2005; Cleland, 2010; Miller & Rodgers, 2009), but this relation is not universal (Agee, 2010; Moestue & Huttly, 2008; Thang & Popkin, 2003). In South Asia, where child malnutrition is very high, mothers regardless of their education may be constrained by gender-based rules that restrict opportunities to make decisions and move around the community.

About 15 years ago, Ramalingaswami et al. (1996) proposed that low women’s status in India was a major contributing factor to poor child health and growth. The implication is that even a woman with sufficient knowledge and resources, accrued as a result of education or SES, will be unable to use these skills to her child’s benefit if she is not enabled to make decisions. The concept of autonomy has been employed by several researchers to capture behaviors such as decision-making and mobility that may or may not be under the mother’s control. One possibility of the mechanism through which maternal autonomy acts to affect child care behaviors lies in the theory of self-determination (Ryan & Deci, 2000). This theory conceptualizes autonomy as an inner psychological need for self-motivation to bring about positive behavior processes. We hypothesize that maternal autonomy is one of the psychological needs that according to the self-determination theory results in intrinsic motivation and behavioral regulation, which in turn will bring about positive, sustained, and long-term behavioral change to impact child health and well-being (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

Demographers and sociologists have defined women’s autonomy in several ways. For example, Dyson (1983) emphasizes decision-making power regarding a woman’s life and those close to her, whereas, Dixon (1978) and Jejeebhoy (2000) focus on control over resources like food, income, knowledge, and prestige, within the family and in society at large. In line with previous research (Agarwala & Lynch, 2006; Jejeebhoy, 2000; Mason, 1986; Shroff et al., 2009), we conceptualize women’s autonomy as consisting of seven dimensions in which women make decisions and control resources within the family: household decision making autonomy, child related decision-making autonomy, financial control and access (financial autonomy), decisions regarding mobility (mobility autonomy), freedom of movement (mobility), acceptance of domestic violence, and experience of domestic violence. These dimensions are relevant to India where women tend to have limited access to resources such as knowledge, information and finances, and are restrained in their movements in and out of the house (Dharmalingam & Morgan, 1996; Visaria et al., 1999; Vlassoff, 1992). Women’s autonomy has been examined in past research as a determinant of contraceptive use, smaller family size, and larger birth intervals (Jejeebhoy, 1991; Schuler & Hashemi, 1994; Upadhyay & Hindin, 2005). However, its effect on child health outcomes is less studied.

Recent literature suggests that women’s autonomy may be one of the important social variables responsible for influencing child nutritional status (Brunson, Shell-Duncan, & Steele, 2009; Shroff et al., 2009; Smith, 2003). In particular, Begin et al. (1999) found that mothers’ higher decision-making power surrounding child feeding is a significant predictor of improved height-for-age z-scores. Engle (1993) found that mothers with a higher contribution of money to the family income had children with significantly better nutritional status. Mothers are more likely to use scarce resources for the benefit of their child if they are free to do so (Castle, 1993; Engle et al., 2000; Mason et al., 1999; Schmeer, 2005). Mothers with greater autonomy may also benefit in other ways that indirectly affect their child. For example, they make greater use of antenatal care despite a variation in socio-economic status (Mistry et al., 2009). This could impact her infant’s birth weight, morbidity and her own nutritional status (Fikree & Pasha, 2004). Thus we examined the influence of factors such as infant morbidity, birth weight, and maternal nutritional status on the associations in our study.

Our research adds to the past work on linkages between autonomy and child health in the following ways. It builds on past research showing the positive link between women’s autonomy and child health (Abadian, 1996; Dreze & Murthi, 2001; Malhotra et al., 1995; Miles-Doan & Bisharat, 1990; Smith, 2003). Some have used proxy (or indirect) measures to operationalize autonomy (such as education, labor force participation, employment status, age at marriage) (Mason, 1986). Others have included specific items to measure autonomy (Balk, 1997; Bloom et al., 2001; Mistry et al., 2009). However, despite recognition that autonomy is a multi-dimensional construct (Agarwala & Lynch, 2006), the majority of past research focuses on one of two dimensions of autonomy such as decision making autonomy (Balk, 1997; Begin et al., 1999; Dharmalingam & Morgan, 1996; Miles-Doan & Brewster, 1998; Senarath & Gunawardena, 2009). Our study differs by examining maternal autonomy as a multi-dimensional concept and develops distinct dimensions of autonomy using confirmatory factor analysis. The underlying premise is that each dimension of women’s autonomy may relate differently to health behaviors and outcomes.

Finally, in previous studies, the child health outcomes examined were primarily growth outcomes in older infants (Begin et al., 1999; Brunson et al., 2009; Johnson & Rogers, 1993; Miles-Doan & Bisharat, 1990; Shroff et al., 2009) and infant morbidity or mortality (Caldwell, 1986; Castle, 1993). Yet maternal autonomy may more directly influence an infant’s nutrition status through the practice of breastfeeding. Exclusive breastfeeding is a practice known to reduce infant morbidity and mortality, enhance development and also protect maternal health by lengthening pregnancy intervals (Black et al., 2008). Hence, in our study, in addition to the growth outcomes, we examined exclusive breastfeeding, a key modifiable feeding behavior.

In India, only 46.3% of infants between 0 to 5 months of age are exclusively breastfed (IIPS & MacroInternational, 2007). In addition to demographic and health system determinants of early cessation of exclusive breast feeding (Bhandari et al., 2008; Chandrashekhar et al., 2007; Gupta et al., 2010; Madhu et al., 2009; Tiwari et al., 2009), autonomy may be relevant because of its effect on health system use and depression during and after delivery, though the findings are not consistent for depression and breast feeding practices (Dennis & McQueen, 2009; Harpham et al., 2009; Navaneetham & Dharmalingam, 2002; Pallikadavath et al., 2004; Simkhada et al., 2010).

Thus, the objectives of this study were to: (1) identify several dimensions of autonomy through confirmatory factor analysis, and (2) examine how autonomy relates to exclusive breast feeding behavior and infant growth indicators. Specifically, we examined whether rural Indian mothers with higher levels of autonomy were more likely to exclusively breast feed infants and have infants with better growth, after accounting for potentially confounding covariates.

Data and methods

Study design and study population

We used baseline data from a 3-arm longitudinal randomized education intervention trial aimed at improving the feeding, growth, and development of 3–15 month old infants. Between September 2005 and July 2006, data were collected from 600 mother-infant pairs in 60 villages in the district of Nalgonda in the state of Andhra Pradesh, India. Sixty villages were selected purposively from three project areas (20 villages in each area) of the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) -- the largest multi-package maternal and child health government program in India. These villages were treated as clusters of three villages and matched on population and maternal literacy within a triplet of villages. The villages within each cluster did not share geographical boundaries to avoid contamination effects from the intervention. The villages within each matched triplet were randomly allocated to the study groups. Within the villages all women in their 3rd trimester of pregnancy were contacted and then recruited into the study when their infants were approximately 3–5 months of age. Thus, the data used in our study are the baseline data for infants aged between 3–5 months, who weighed more than 1.5 kg at birth, and who had no apparent chronic or congenital illness. This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC) of the National Institute of Nutrition, Indian Council of Medical Research, India, as well as the IRB at University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Outcome measures: Breastfeeding behavior and growth of infants

The first outcome used in this study is exclusivity in breastfeeding (at 3–5 months of age) in accordance with WHO guidelines for appropriate feeding specifying that no other foods or liquids be given in the first six months of life (WHO, 2003). We measured breastfeeding with questions used in the NFHS-2 survey (International Institute for Population Sciences and ORC Macro, 2000). We represented feeding behavior with a binary variable=0 if the infant was fed any foods or liquids other than breast milk at or before the time of the survey, and =1 if the infant was exclusively breastfed until the time of the survey. We studied exclusive rather than predominant breastfeeding in light of the fact that even feeding of non-nutritive liquids can increase risk of diarrheal diseases (Popkin et al., 1990). We also examined nutritional status outcomes including length-for-age (LAZ), weight-for-age (WAZ), and weight-for-length or (WLZ) calculated using the WHO 2005 growth standards (WHO, 2006).

Maternal autonomy: main explanatory variable

We measured the various dimensions of autonomy using a self-reported 47-item questionnaire. Majority of the responses were made on a 3 or 5 point Likert scale; scores were recoded such that 1represented low levels of autonomy and the higher score represented higher levels of autonomy. Except for the experience of domestic violence dimension, the other dimensions were identified a priori and validated using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Thus, the seven dimensions were household decision making, child-related decision-making, financial independence, permission for mobility reverse scored to reflect mobility autonomy, actual mobility, non-acceptance of domestic violence, and experience of domestic violence. A significant majority of the questions came from the survey on the Status of Women and Fertility (Smith, Ghuman, Lee, & Mason, 2000) and the Indian National Family Health Survey (International Institute for Population Sciences and ORC Macro, 2000).

Construction of latent autonomy variables (dimensions)

We used Mplus v.4.1 to carry out CFA to reduce our 46 items to six latent factors. Being a single item, experience of domestic violence was not included in the CFA. CFA is a hypothesis testing procedure and it validates an a priori conceptualization of factors by accounting for measurement errors in individual observed variables. This technique was chosen over exploratory factor analysis because previous researchers have identified the important domains of autonomy. We used CFA to test their applicability in this sample and setting. Specifically, we examined the model fit, the factor to item R2 and factor loadings from the CFA to assess the construct validity of the factors. Further, we assumed the missing at random approach for the items considered and used the type = missing option in Mplus that uses the full information maximum likelihood estimator to account for the missing data.

The measurement model included items representing the following dimensions: (1) household decision making, (2) decisions regarding child care, (3) mobility autonomy, (4) actual mobility, (5) financial autonomy, and (6) non-acceptance of domestic violence. The items under certain dimensions were reverse coded appropriately such that a higher score on each item represented higher autonomy. The first model had poor fit. To improve model fit, we removed items from the respective dimension if the R-square was less than 0.40 and modification indices were greater than 10.0 (Brown, 2006). Our final model fitted well with the following indices: CFI 0.932, TLI 0.941, RMSEA 0.052 (see Table 2) (Brown, 2006). Overall, these findings suggest that the measurement model performed well. Weighting each response with the standardized factor score for that item, we created a composite score for each of the six autonomy variables. The correlation between the autonomy factors ranges from −0.10 to 0.40 and thus factors were fairly independent of each other.

Table 2.

Percent of mothers answering autonomy questions administered at the baseline among mothers from 60 villages in Andhra Pradesh, India, along with item factor loadings

| Household Decision-making autonomy | |||||

| Who in your family decides the following: | Others in household | Jointly with others in household | Respondent | n | Factor loadings |

| 1. What food to buy for family meals? | 65.88 | 18.82 | 15.29 | 595 | - |

| 2. Whether to purchase small household items such as a table, utensils? | 64.71 | 20.50 | 14.79 | 595 | - |

| 3. What gifts to give when relatives marry? | 59.33 | 36.30 | 4.37 | 595 | 1 |

| 4. Whether or not you should work outside the home? | 50.91 | 10.18 | 38.90 | 383 | 0.755 |

| 5. Inviting guests to your home? | 56.51 | 34.69 | 8.80 | 591 | - |

| 6. Your going and staying with parents or siblings? | 83.90 | 11.19 | 4.92 | 590 | - |

| 7. Obtaining health care for yourself? | 63.16 | 30.39 | 6.45 | 589 | 0.737 |

| 8. Whether to purchase major goods for the household such as a TV? | 76.18 | 22.97 | 0.84 | 592 | - |

| 9. Whether to purchase or sell animals? | 79.41 | 19.79 | 0.80 | 374 | - |

| 10. Whether to purchase or sell gold/silver jewelry? | 66.44 | 30.14 | 3.42 | 584 | 0.812 |

| 11. How your earnings are spent? | 57.29 | 25.99 | 16.71 | 377 | - |

| 12. Whether money can be spent on health care for the child? | 62.02 | 31.43 | 6.55 | 595 | 0.959 |

| Child- care decision making autonomy | |||||

| Who in your family decides the following: | Others in household | Jointly with others | Respondent | n | Factor loadings |

| 1. Not feeding the new born baby colostrums? | 13.53 | 4.92 | 81.55 | 569 | - |

| 2. Exclusive breast feed newborn for 6 months? | 3.55 | 2.20 | 94.26 | 592 | - |

| 3. Immunization of the infant | 14.48 | 15.99 | 69.53 | 594 | 1 |

| 4. What to do if the child falls sick? | 24.79 | 36.26 | 38.95 | 593 | 1.154 |

| Financial autonomy: Control over finances | |||||

| No | Yes | n | Factor loadings | ||

| 1. If you wanted to buy yourself a dress, would you feel free to do it without consulting your husband? | 61.46 | 38.54 | 589 | 1 | |

| 2. If you wanted to buy yourself a small item of jewelry, such as a pair of earrings or bangle, would you feel free to do it? | 65.99 | 34.01 | 588 | 1.037 | |

| 3. If you wanted to buy a small gift for your parents or other family members, would you feel free to do it? | 83.39 | 16.61 | 584 | - | |

| Never | Some of the time | All the time | n | ||

| 4. Are you allowed to have some money set aside that you can use as you wish? | 28.89 | 35.98 | 35.14 | 592 | 0.656 |

| 5. When you earn money, do you usually give all of it to your husband? (Reverse code) | 49.86 | 29.43 | 20.71 | 367 | - |

| 6. Do you and your husband ever talk alone with each other about what to spend money on? | 23.36 | 45.38 | 31.26 | 595 | 0.804 |

| 7. Do you have a say in how the household’s overall income is spent? | 27.73 | 56.81 | 15.46 | 595 | 0.710 |

| 8. Do you get any cash in hand to spend on household expenditure? | 43.58 | 39.24 | 17.19 | 576 | - |

| Mobility autonomy | |||||

| Do you have to ask your husband or senior family members for permission to go to (reverse scored) | Always | Some of the time | Never | n | Factor loadings |

| 1. Any place outside your house or compound? | 69.30 | 8.25 | 22.46 | 570 | 1 |

| 2. To the local market? | 64.34 | 9.69 | 25.97 | 258 | - |

| 3. To the local health center? | 81.77 | 9.20 | 9.03 | 587 | 1.386 |

| 4. Fields outside the village? | 65.67 | 6.81 | 27.52 | 367 | - |

| 5. Community center in the village? | 69.79 | 9.72 | 20.49 | 566 | - |

| 6. Home of relatives or friends in the village? | 65.11 | 12.34 | 22.55 | 235 | - |

| 7. A nearby fair? | 80.24 | 10.58 | 9.18 | 501 | 1.316 |

| 8. The next village? | 87.46 | 8.25 | 4.30 | 582 | 1.354 |

| Mobility | |||||

| Can you go to any of the following by yourself: | Never allowed to go | Sometimes when I choose to | Always when I choose | n | Factor loadings |

| 1. Local market? | 30.67 | 8.00 | 61.33 | 300 | - |

| 2. Local health center? | 39.06 | 6.23 | 54.71 | 594 | 1 |

| 3. Fields? | 10.55 | 3.17 | 86.28 | 379 | - |

| 4. Community center in the village? | 11.43 | 6.94 | 81.63 | 245 | - |

| 5. Home of relatives or friends in the village? | 17.86 | 6.83 | 75.31 | 571 | 1.009 |

| 6. Temple? | 30.52 | 9.14 | 60.34 | 580 | 1.188 |

| 7. Next Village? | 64.59 | 7.78 | 27.63 | 514 | - |

| 8. Fair? | 29.62 | 17.94 | 52.44 | 574 | 0.712 |

| Non-acceptance of Domestic Violence | |||||

| Sometimes a wife can do something that bothers her husband. Please tell me if you think that a husband is justified in beating his wife in the following situations: | Always | Some of the time | Never | n | Factor loadings |

| 1. If he suspects her of being unfaithful? | 1.69 | 37.33 | 60.98 | 592 | 1 |

| 2. If her natal family does not give expected money, jewelry, or other items? | 0.67 | 8.24 | 91.09 | 595 | 1.012 |

| 3. If she shows disrespect for in-laws? | 0.67 | 44.52 | 54.81 | 593 | 1.089 |

| 4. If she goes out without telling him? | 0.17 | 29.63 | 70.20 | 594 | 1.073 |

| 5. If she neglects the house or children? | 1.35 | 56.73 | 41.92 | 594 | 1.131 |

| 6. If she doesn’t cook food properly | 0.34 | 16.97 | 82.69 | 595 | 0.830 |

| Freedom from Domestic Violence | |||||

| Yes | No | n | |||

| Does your husband ever hit or beat you? | 24.83 | 75.17 | 592 | ||

Method of Analysis: Multivariate modeling

Given that mothers were drawn from multiple villages, we first examined if there were village-level variations in our outcomes. Second, using logistic regression, we examined the association between each of the 6 autonomy variables along with the experience of domestic violence, and exclusive breastfeeding. Similar procedures were used to examine autonomy in relation to infant weight and length outcomes, this time using a least squares multiple regression. Our model building process consisted of regressing each autonomy dimension and the outcome variable (7 regressions) and then a final eighth regression that included all the seven autonomy dimensions in the same model. In the interest of space we only present the models including all seven autonomy dimensions, although the significance of the association between the autonomy dimensions and outcomes did not change in models where the autonomy dimensions were entered individually. In each of the regression models we also controlled for covariates. We considered several household, maternal, and infant characteristics as covariates, including standard of living, caste, household social structure (joint versus nuclear), mother’s age, education, employment status, height, child’s age, sex and parity, that may act as confounders of the relationship of autonomy with the feeding and growth outcomes. The household standard of living was adapted from the National Family Health Survey (International Institute for Population Sciences and ORC Macro, 2000). The questions included in the index measure the quality of household construction, land and household ownership, house type, toilet facility, source of lighting, main fuel for cooking, source of drinking water, separate room for cooking, ownership of the house, agricultural land, irrigated land, livestock and household assets such as radio, television, and a bed. We also examined the influence of factors such as birth weight, maternal nutritional status, maternal depression and infant morbidity (measured as the number of illness episodes in the last two weeks) on the relationship between autonomy and the main infant growth and feeding outcomes. The series of regression models were carried out using STATA v.10 and the significance was tested with alpha equal to 0.05.

Results

Description of Sample

The study sample consisted of 600 mother-child dyads, with an equal distribution of nuclear and joint family households (Table 1). These households were predominantly Hindu and 65% of the sample belonged to the “backward caste” of the caste system.i In our sample, 60% of the households were categorized in the highest level of standard of living and 35% with a medium standard of living index based on the standard for living index relative to a national standard of living ranking index. More than one third of the mothers had no education, and another third had only primary education. Approximately one third of the mothers were undernourished, with a BMI <18.5. 12% of children were reported to weigh between 1500 and 2500 grams at birth.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of mothers and children from the 60 villages in Andhra Pradesh, India

| Variables | n | Percentage | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household characteristics | ||||

| Religion | ||||

| Hindu | 581 | 97.8 | - | - |

| Muslim | 13 | 2.2 | - | - |

| Standard of living index(score)* | 594 | - | 26.68 | 7.54 |

| Low | 23 | 3.9 | - | - |

| Medium | 208 | 35.0 | - | - |

| High | 363 | 61.1 | - | - |

| Caste | ||||

| Schedule Caste/Tribe | 152 | 25.6 | - | - |

| Backward Class | 387 | 65.1 | - | - |

| Forward Class | 55 | 9.2 | - | - |

| Family type | ||||

| Nuclear | 268 | 45.2 | - | - |

| Joint | 324 | 54.7 | - | - |

| Mother’s characteristics | ||||

| Age (years) | 590 | - | 22.14 | 3.35 |

| Height (cm) | 575 | - | 151.51 | 5.53 |

| Weight (kg) | 575 | - | 45.36 | 6.79 |

| BMI† | 574 | - | 19.72 | 2.57 |

| <18.5 | 192 | 33.5 | - | - |

| ≥18.5 and <25 | 362 | 63.0 | - | - |

| ≥25 | 20 | 3.5 | - | - |

| Education | ||||

| No schooling | 226 | 38.1 | - | - |

| Primary | 197 | 33.2 | - | - |

| Secondary | 135 | 22.7 | - | - |

| Higher | 35 | 6.0 | - | - |

| Work status | ||||

| Non-working | 456 | 77.4 | - | - |

| Working | 133 | 22.6 | - | - |

| Parity | ||||

| 1 child | 222 | 37.4 | - | - |

| 2 child | 241 | 40.5 | - | - |

| > 2 child | 131 | 22.0 | - | - |

| Infant’s characteristics | ||||

| Age (months) | 594 | - | 3.4 | 0.54 |

| Sex | ||||

| Boys | 294 | 49.2 | - | - |

| Girls | 303 | 50.7 | - | - |

| Birth weight(kg) | ||||

| <=2 | 42 | 7.0 | - | - |

| >2 & <2.5 | 35 | 5.9 | - | - |

| >=2.5 | 517 | 87.1 | - | - |

| Infant anthropometry | ||||

| Length (cm) | 593 | 59.059 | 2.559 | |

| Weight (kg) | 592 | 5.525 | 0.814 | |

| Length-for-Age z-score | 585 | −1.182 | 1.065 | |

| Weight-for-Age z-score | 585 | −1.178 | 1.100 | |

| Weight-for-length z-score | 585 | −0.337 | 1.167 | |

| Outcome: Feeding practices | ||||

| Exclusive breast feeding at the time of the survey (i.e. at the ages of 3–5 months) | ||||

| No | 149 | 24.9 | - | - |

| Yes | 446 | 75.1 | - | - |

Standard of living index- score created based on the weighted index created by NFHS (Demographic Health Survey, India)

BMI=((weight*1000/(height)2)

In our sample, 75% of mothers exclusively breast fed their infants. The mean length-for-age z-scores (LAZ) among the infants was −1.182 and mean weight-for-age z-score (WAZ) was −1.178. These scores indicate that the infants in our sample were much shorter and lighter, compared to the international standard.

We present descriptive statistics for each of the autonomy questions in Table 2. Key findings from these reveal that around 66% mothers reported that the decisions regarding how her own earnings are to be spent or whether she can seek healthcare for herself are taken by others in the household. Approximately 50% of mothers sometimes or most of the time gave their earnings to their husbands, and 45% of mothers did not have their own cash for household expenditures. 70% of mothers reported they needed permission to go any place in or outside the village, and 80% of mothers reported needing permission to go to the local health center.

Prediction of Breastfeeding, Height and Weight

The seven autonomy variables were first included in multivariate logistic regression models with exclusive breastfeeding as the outcome. Because our data had multiple individuals within a village, we examined village level variation. There was no significant village-level variation in this model. In both the unadjusted and adjusted models, financial autonomy was significantly associated with exclusive breastfeeding (Table 3). In the adjusted model, mothers who scored higher on financial autonomy were 1.26 times more likely to exclusively breastfeed [OR = 1.26; 95% CI: 1.00, 1.58]. None of the other autonomy dimensions was significantly associated with exclusive breastfeeding. Maternal depression and birth weight were not significantly associated with exclusive breastfeeding in bivariate analysis and maternal nutritional status did not change the result of the association observed between financial autonomy and exclusive breastfeeding.

Table 3.

Results from Logistic Regression Model presenting odds ratios of Breast feeding behavior in mothers with infants 3–5 months of age, Andhra Pradesh, India

| Exclusive breastfeeding behavior at the time of the survey (Outcome) | Unadjusted model (n=592) | Adjusted model (n=554) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | |

| Autonomy factors* | ||||

| Financial Independence | 1.23 | (1.00, 1.51) | 1.26** | (1.00, 1.58) |

| Mobility autonomy | 0.99 | (0.69, 1.09) | 0.99 | (0.77, 1.58) |

| Mobility | 1.00 | (0.81, 1.24) | 0.99 | (0.78, 1.24) |

| Household decision | 1.06 | (0.81, 1.37) | 0.98 | (0.73, 1.31) |

| Child care decision | 0.86 | (0.68, 1.08) | 0.83 | (0.65, 1.05) |

| Non-accept of Domestic Violence | 0.87 | (0.71, 1.06) | 0.88 | 0.70, 1.09) |

| Experience of Domestic Violence | 0.78 | (0.51, 1.21) | 0.69 | (0.42, 1.11) |

| Covariates | ||||

| Mother’s Age | 0.97 | (0.90, 1.03) | ||

| Mother’s Education: Ref. No education | ||||

| Primary Education | 1.00 | (0.60, 1.67) | ||

| Secondary Education | 1.01 | (0.55, 1.84) | ||

| Greater than Secondary Education | 0.88 | (0.36, 2.18) | ||

| Mother’s Body Mass Index | 1.05 | (0.97, 1.14) | ||

| Mother working status: Ref. Does not work | ||||

| Mother works for cash/kind | 0.87 | (0.54, 1.40) | ||

| Child’s Age | 1.33 | (0.89, 1.98) | ||

| Child’s Gender: Ref. Male | ||||

| Female | 0.95 | (0.63, 1.43) | ||

| Parity: Ref. First child | ||||

| Second child | 2.20** | (1.35, 3.57) | ||

| Third or greater than third child | 2.07** | (1.12, 3.82) | ||

| Standard of living: Ref. Low | ||||

| Medium | 1.46 | (0.51, 4.16) | ||

| High | 1.79 | (0.61, 5.22) | ||

| Family structure: Ref. Nuclear | ||||

| Joint | 0.89 | (0.55, 1.44) | ||

| Caste: Ref. Schedule caste/tribe | ||||

| Backward class | 0.61 | (0.37, 1.02) | ||

| Forward class | 0.64 | (0.28, 1.47) | ||

Autonomy factors used as Latent Factor Score;

p<0.001,

p<0.05,

p<0.1

Among the outcomes, only WAZ and LAZ showed significant (p < 0.05) village-level variation (and intra-class correlation, ICC). For consistency, we report random-effect models for all the three growth outcomes. Using random-effect regression models for WAZ, LAZ, and WLZ, differential effects of the autonomy dimensions were observed for the three growth indicators. The ability to make household decisions was significantly and positively associated with WAZ [β = 0.167; 95% CI: 0.037, 0.297] and WLZ [β = 0.263; 95% CI: 0.106, 0.421] after controlling for covariates (Table 4). In addition, a high score on mobility autonomy (i.e. not needing permission to go out) was associated with lower WLZ [β = −0.202; 95% CI: −0.342, −0.063].

Table 4.

Results from Random-effects GLS Models presenting Coefficients for WAZ and WLZ of infants 3–5 months of age

| Weight-for-age z-score (WAZ) | Weight-for-length z-score (WLZ) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted model (N=582, R2=0.013) | Adjusted model (N=465, R2=0.324) | Unadjusted model (N=582, R2=0.019) | Adjusted model (N=465, R2 =0.110) | |||||

| β | 95%CI | β | 95%CI | β | 95%CI | β | 95%CI | |

| Autonomy factors* | ||||||||

| Financial Independence | 0.024 | (−0.072, 0.120 | −0.010 | (−0.104, 0.097) | −0.013 | (−0.117, 0.090) | −0.039 | (−0.174, 0.070) |

| Mobility autonomy | −0.039 | (−0.140, 0.062) | −0.028 | (−0.142, 0.086) | −0.145** | (−0.266, −0.025) | −0.202** | (−0.342, −0.063) |

| Mobility | −0.052 | (−0.165, 0.061) | −0.042 | (−0.142, 0.057) | −0.089 | (−0.198, 0.019) | −0.064 | (−0.185, 0.056) |

| Household Decision making | 0.113* | (−0.012, 0.237) | 0.167** | (0.037, 0.297) | 0.173** | (0.041, 0.306) | 0.263** | (0.106, 0.421) |

| Child care decision making | −0.003 | (−0.110, 0.104) | 0.062 | (−0.044, 0.168) | −0.020 | (−0.134, 0.093) | −0.006 | (−0.134, 0.122) |

| Acceptance of Domestic Violence | −0.077 | (−0.173, 0.018) | −0.019 | (−0.118, 0.079) | −0.053 | (−0.154, 0.049) | −0.001 | (−0.119, 0.119) |

| Experience of Domestic Violence | 0.001 | (−0.209, 0.212) | 0.095 | (−0.129, 0.321) | 0.066 | (−0.159, 0.290) | 0.088 | (−0.185, 0.361) |

| Covariates | ||||||||

| Mother’s Age | −0.006 | (−0.037, 0.023) | −0.025 | (−0.063, 0.011) | ||||

| Mother’s Education: Ref. No education | ||||||||

| Primary Education | 0.069 | (−0.159, 0.299) | −0.028 | (−0.307, 0.250) | ||||

| Secondary Education | 0.012 | (−0.252, 0.277) | −0.218 | (−0.540, 0.104) | ||||

| Greater than Secondary Education | −0.127 | (−0.517, 0.264) | −0.209 | (−0.684, 0.266) | ||||

| Mother’s Body Mass Index | 0.022 | (−0.013, 0.057) | 0.064** | (0.021, 0.107) | ||||

| Mother’s height | 0.033*** | (0.016, 0.050) | −0.018 * | (−0.039, 0.002) | ||||

| Mother working status: Ref. Does not work | ||||||||

| Mother works for cash/kind | −0.086 | (−0.305, 0.132) | −0.154 | (−0.417, 0.109) | ||||

| Child’s Age | −0.074 | (−0.239, 0.091) | −0.158 | (−0.360, 0.043) | ||||

| Child’s Gender: Ref. Male | ||||||||

| Female | 0.187** | (0.004, 0.371) | −0.049 | (−0.272, 0.173) | ||||

| Child’s birth weight | 1.072*** | (0.881, 1.263) | 0.281** | (0.052, 0.510) | ||||

| Parity: Ref. First child | ||||||||

| Second child | 0.027 | (−0.184, 0.238) | −0.046 | (−0.302, 0.209) | ||||

| Third or greater than third child | −0.175 | (−0.454, 0.105) | −0.187 | (−0.527, 0.151) | ||||

| Standard of living: Ref. Low | ||||||||

| Medium | −0.144 | (−0.680, 0.391) | −0.148 | (−0.800, 0.503) | ||||

| High | 0.047 | (−0.493, 0.587) | 0.073 | (−0.583, 0.730) | ||||

| Family structure: Ref. Nuclear | ||||||||

| Joint | −0.018 | (−0.200, 0.237) | 0.147 | (−0.117, 0.412) | ||||

| Caste: Ref. Schedule caste/tribe | ||||||||

| Backward class | 0.151 | (−0.074, 0.376) | 0.015 | (−0.261, 0.292) | ||||

| Forward class | 0.097 | (−0.263, 0.457) | 0.095 | (−0.344, 0.534) | ||||

| Maternal depression | −0.006 | (−0.018, 0.005) | 0.008 | (−0.006, 0.021) | ||||

Autonomy factors used as Latent Factor Score;

p<0.001,

p<0.05,

p<0.1

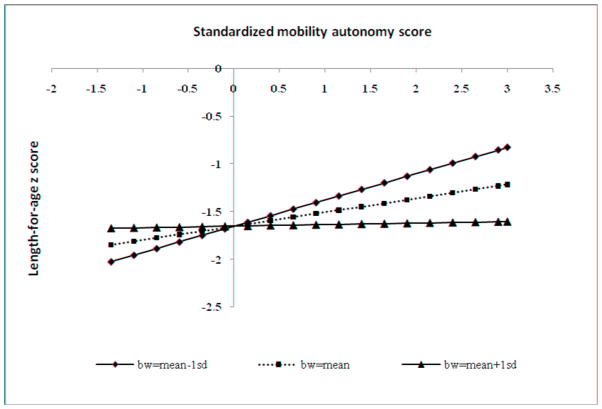

For LAZ, there was no significant association observed in the unadjusted models and subsequent models adjusted for household and maternal characteristics (Table 5, Models 1). However, we observed a positive influence of both mobility autonomy [β =0.147; 95% CI: 0.048, 0.246] and child-care decision-making [β = 0.097; 95% CI: 0.005, 0.188] on LAZ when we controlled for birth weight in addition to other household and maternal characteristics (Table 5, Model 2). To understand this further, we introduced interaction terms, namely birth weight × child-care decision-making and birth weight × mobility autonomy into the model (Table 5, Model 3). We observed that the interaction term of birth weight × mobility autonomy was significantly and negatively associated with LAZ [β =−0.265; 95% CI: −0.430, −0.100]. Figure 1 presents a graph showing that not requiring permission to go places was more strongly associated with LAZ for infants with lower birth weight (birth weight mean –1SD) compared to those of higher birth weight.

Table 5.

Results from Random-effects GLS Models presenting Coefficients for Length-for-age z-score (LAZ) of infants 3–5 months of age

| Outcome: LAZ | Unadjusted (Model 1) (N=582; R2 =0.010) | Adjusted (Model 2) (N=465; R2=0.409) | Adjusted for interaction (Model 3) (N=465; R2=0.424) | Adjusted for depression (Model 4) (N=465; R2=0.449) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95%CI | β | 95%CI | β | 95%CI | β | 95%CI | |

| Autonomy factors* | ||||||||

| Financial Independence | 0.052 | (−0.040, 0.145) | 0.033 | (−0.056, 0.122) | 0.039 | (−0.048, 0.127) | 0.016 | (−0.072, 0.105) |

| Mobility autonomy | 0.069 | (−0.039, 0.177) | 0.147** | (0.048, 0.246) | 0.894** | (0.419, 1.369) | 0.141** | (0.043, 0.240) |

| Mobility | 0.031 | (−0.067, 0.128) | −0.001 | (−0.087, 0.086) | −0.010 | (−0.097, 0.075) | 0.004 | (−0.081, 0.090) |

| HH Decision making | −0.042 | (−0.161, 0.077) | −0.056 | (−0.169, 0.056) | −0.058 | (−0.169, 0.053) | −0.064 | (−0.175, 0.046) |

| Child care decision | 0.047 | (−0.054, 0.149) | 0.097** | (0.005, 0.188) | 0.089* | (0.000, 0.180) | 0.100** | (0.011, 0.191) |

| Acceptance of Domestic Violence | −0.043 | (−0.134, 0.048) | −0.011 | (−0.095, 0.074) | −0.014 | (−0.098, 0.069) | −0.024 | (−0.108, 0.059) |

| Experience of Domestic Violence | −0.042 | (−0.244, 0.160) | 0.027 | (−0.167, 0.221) | 0.020 | (−0.171, 0.212) | 0.035 | (−0.158, 0.229) |

| Covariates | ||||||||

| Mother’s Age | 0.006 | (−0.020, 0.033) | 0.008 | (−0.018, 0.034) | 0.007 | (−0.019, 0.033) | ||

| Mother’s Education: Ref. No education | ||||||||

| Primary Education | 0.072 | (−0.126, 0.271) | 0.091 | (−0.104, 0.288) | 0.106 | (−0.089, 0.303) | ||

| Secondary Education | 0.210 | (−0.020, 0.441) | 0.229** | (0.001, 0.458) | 0.201** | (0.026, 0.428) | ||

| Greater than Secondary Education | 0.082 | (−0.260, 0.424) | 0.097 | (−0.241, 0.435) | 0.086 | (−0.249, 0.421) | ||

| Mother’s Body Mass Index | −0.020 | (−0.051, 0.010) | −0.020 | (−0.050, 0.010) | −0.016 | (−0.047, 0.014) | ||

| Mother’s height | 0.052*** | (0.038, 0.067) | 0.052*** | (0.037, 0.066) | 0.050*** | (0.035, 0.065) | ||

| Mother working status: Ref. Does not work | ||||||||

| Mother works for cash/kind | −0.080 | (−0.270, 0.109) | −0.080 | (−0.267, 0.107) | −0.038 | (−0.225, 0.147) | ||

| Child’s Age | −0.097 | (−0.243, 0.048) | −0.084 | (−0.228, 0.061) | −0.050 | (−0.195, 0.095) | ||

| Child’s Gender: Ref. Male | ||||||||

| Female | 0.288*** | (0.129, 0.447) | 0.294*** | (0.136, 0.451) | 0.290*** | (0.133, 0.447) | ||

| Child’s birth weight (BW) | 1.069*** | (0.905, 1.233) | 1.058*** | (0.896, 1.221) | 1.092*** | (0.930, 1.254) | ||

| Interaction: | -- | -- | −0.265** | (−0.430, −0.100) | −0.143*** | (−0.225, −0.062) | ||

| Birth Weight * mobility autonomy | ||||||||

| Parity: Ref. First child | ||||||||

| Second child | 0.121 | (−0.062, 0.304) | 0.124 | (−0.057, 0.305) | 0.111 | (−0.069, 0.291) | ||

| Third or greater than third child | −0.027 | (−0.272, 0.217) | 0.006 | (−0.237, 0.249) | 0.009 | (−0.233, 0.251) | ||

| Standard of living: Ref. Low | ||||||||

| Medium | −0.096 | (−0.538, 0.347) | −0.078 | (−0.516, 0.360) | −0.040 | (−0.510, 0.421) | ||

| High | −0.023 | (−0.446, 0.419) | −0.003 | (−0.441, 0.434) | 0.060 | (−0.403, 0.528) | ||

| Family structure: Ref. Nuclear | ||||||||

| Joint | −0.102 | (−0.289, 0.085) | −0.110 | (−0.295, 0.075) | −0.045 | (−0.234, 0.144) | ||

| Caste: Ref. Schedule caste/tribe | ||||||||

| Backward class | 0.011 | (−0.088, 0.312) | 0.096 | (−0.102, 0.294) | 0.118 | (−0.080, 0.318) | ||

| Forward class | 0.070 | (−0.237, 0.378) | 0.046 | (−0.259, 0.351) | 0.062 | (−0.251, 0.374) | ||

| Maternal Depression | −0.133*** | (−0.215, −0.052) | ||||||

Autonomy factors used as Latent Factor Score;

p<0.001,

p<0.05,

p<0.1

Figure 1.

Graph presenting LAZ outcome with interaction of birth weight and mobility autonomy

After controlling for maternal depression in the growth models, results for the main effect of autonomy did not change. Further, maternal depression remained significant only in the LAZ model (Table 5, Model 4). There were no mediating effects of infant morbidity, maternal nutritional status, and maternal depression on autonomy and the growth outcomes (results not shown).

Discussion

In a sample of 600 mother-infant dyads in rural Andhra Pradesh, India, we examined the association of different dimensions of maternal autonomy with exclusivity of breastfeeding as well as infant growth in the first 3–5 months of life. Mothers with higher levels of financial autonomy were more likely to exclusively breastfeed, independent of other autonomy dimensions and controlling for covariates. Further, household decision making autonomy was positively associated with infant WLZ and WAZ. Mobility autonomy showed negative association with WLZ. We also observed a positive association of LAZ with mobility autonomy and child-care decision-making after controlling for birth weight of the infant.

The positive impact of financial autonomy of mothers on child nutritional status has been studied previously (Begin et al., 1999; Engle, 1993) but the direct relationship with breastfeeding behavior has not been observed. In a recent study using the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-2) data, financial autonomy of mothers was significantly associated with use of antenatal care in the southern states of India (Mistry et al., 2009). Thus, it is possible that the relationship between financial autonomy and exclusive breast feeding observed in our study is because mothers with higher financial autonomy received more advice about optimal breastfeeding while attending antenatal care. Most antenatal care services in this part of India provide information regarding postnatal infant care, including breastfeeding counseling. However, we do not have data on antenatal care for this sample to test this hypothesis.

Unlike other studies, financial autonomy was not associated with infant growth in our study (Brunson et al., 2009; Engle, 1993). This may be due to the younger ages of our sample. Engle et al. (1993) reported that the percentage of income contributed by mothers to the total household income was positively associated with nutritional status of children aged 8–47 months. Thus, the mothers with more control over finances (higher financial autonomy) may have greater control over food fed to young children. However, in our study, the children of 3 to 5 months were predominantly breastfed, and therefore unlikely to benefit from family food distribution. Next, our results show that mothers who had higher participation in household decision-making had infants with better WAZ and WLZ, compared to infants of mothers with less household decision-making. Our findings confirm those of previous research, suggesting that decision making autonomy impacts the nutritional status of children (Desai & Johnson, 2005; Johnson & Rogers, 1993; Jones et al., 2006; Miles-Doan & Bisharat, 1990). However, unlike earlier studies, we found that decision making about household management was associated with infants’ nutritional status, not only that of older children.

Birth weight moderated the association between mobility autonomy and LAZ. Infants at the lower end of the birth weight distribution may have benefited from their mother’s ability to move without permission, for example, to attend postnatal check-ups, monitor adequate growth, and get advice on health care. Similarly, lower birth weight children benefited more from their mothers’ freedom to make child-care decisions on their own. We examined data in our study on the number of morbidity episodes experienced by an infant in the two weeks before the survey and additional analyses show that autonomy was not related to morbidity episodes (results not shown here). However, it is possible that mothers with higher child care-related decisions may make more appropriate decisions about care when an infant is unwell, which could shorten the morbidity episode. Although we confirm the results of previous studies that postnatal depression is associated with stunting (Black et al., 2009; Stewart, 2007), we do not find maternal depression to significantly mediate the relationships observed with autonomy in our study. Surprisingly, there was an inverse relation between mothers’ mobility autonomy and infants’ WLZ. Mothers with greater freedom to go places without permission had children with greater length only if the infant was on the lower end of the birth weight distribution, but overall the mothers with higher mobility autonomy had children with lower weight for their length. These findings need further replication.

A potential limitation is that we are unable to provide a conceptual framework for why specific domains of autonomy might or might not relate to specific child feeding and nutritional outcomes. Our findings suggest it may be premature to provide such a framework. In some cultures, the items may all load on the same factor, though in our sample they constituted different domains of autonomy. Still, several domains correlated positively, namely household decision making, mobility autonomy, and financial autonomy, yet none correlated with the mothers’ level of schooling. Some of the autonomy questions were not applicable to all. For example, if the mother did not work and earn money, then the questions on “who decides on how her earnings are spent or does she give her earnings to her husband” were not applicable. Not all mothers answered all questions. These items dropped out during the confirmatory factor analysis as they did not load well on the respective sub-construct of autonomy.

To conclude, we examined the impact of multiple dimensions of maternal autonomy on feeding and nutritional outcomes of infants in a rural setting of Andhra Pradesh, India. Our findings suggest that individual domains of autonomy could operate differently to influence child growth.

Research highlights.

We examined maternal autonomy as a determinant of feeding practice and infant growth in India.

Autonomy could potentially influence self-motivation to bring about positive behavior processes.

Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to develop multiple dimensions of maternal autonomy.

Individual domains of autonomy could operate differently to influence child growth and well-being.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Linda Adair for her valuable comments on previous drafts of this paper. This study was supported by the funding received from NIH/NICHD (R01 HD042219-03S1)

Footnotes

Backward caste is a term used by the Government of India, for castes which are economically and socially disadvantaged and face, or may have faced, discrimination on account of birth (Backward Class 2007, June 27). Forward caste, in India, denotes peoples, communities and castes from any religion who do not currently qualify for a Government India reservation benefit (for political representation) for backward classes, scheduled castes and tribes.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abadian S. Women’s autonomy and its impact on fertility. World Development. 1996;24(12):1793–1809. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwala R, Lynch SM. Refining the measurement of women’s autonomy: An international application of a multi-dimensional construct. Social Forces. 2006;84(4):2077–2098. [Google Scholar]

- Agee MD. Reducing child malnutrition in Nigeria: Combined effects of income growth and provision of information about mothers’ access to health care services. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;71(11):1973–1980. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balk D. Defying Gender Norms in Rural Bangladesh: A Social Demographic Analysis. Population Studies. 1997;51(2):153–172. [Google Scholar]

- Basu AM, Stephenson R. Low levels of maternal education and the proximate determinants of childhood mortality: a little learning is not a dangerous thing. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;60(9):2011–2023. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begin F, Frongillo EA, Jr, Delisle H. Caregiver behaviors and resources influence child height-for-age in rural Chad. Journal of Nutrition. 1999;129(3):680–686. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.3.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari N, Kabir AK, Salam MA. Mainstreaming nutrition into maternal and child health programmes: scaling up of exclusive breastfeeding. Maternal and Child Nutrition. 2008;4(Suppl 1):5–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2007.00126.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black MM, Baqui AH, Zaman K, El Arifeen S, Black RE. Maternal depressive symptoms and infant growth in rural Bangladesh. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2009;89(3):951S–957S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26692E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, Caulfield LE, de Onis M, Ezzati M, et al. Maternal and child undernutrition: global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet. 2008;371(9608):243–260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61690-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom SS, Wypij D, Das Gupta M. Dimensions of women’s autonomy and the influence on maternal health care utilization in a north Indian city. Demography. 2001;38(1):67–78. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research. New York: The Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Brunson EK, Shell-Duncan B, Steele M. Women’s autonomy and its relationship to children’s nutrition among the Rendille of northern Kenya. American Journal of Human Bioliology. 2009;21(1):55–64. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell JC. Routes to Low Mortality in Poor Countries. Population and Development Review. 1986;12(2):171–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2010.00353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castle SE. Intra-household differentials in women’s status: household function and focus as determinants of children’s illness management and care in rural Mali. Health Transit Rev. 1993;3(2):137–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrashekhar TS, Joshi HS, Binu V, Shankar PR, Rana MS, Ramachandran U. Breast-feeding initiation and determinants of exclusive breast-feeding - a questionnaire survey in an urban population of western Nepal. Public Health Nutrition. 2007;10(2):192–197. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007248475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleland J. The benefits of educating women. The Lancet. 2010;376(9745):933–934. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61417-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis CL, McQueen K. The relationship between infant-feeding outcomes and postpartum depression: a qualitative systematic review. Pediatrics. 2009;123(4):e736–751. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai S, Johnson K. Women’s Decisionmaking and Child Health: Familial and Social Hierarchies. In: Kishor S, editor. A Focus on Gender. Calverton, Maryland: ORC Macro; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dharmalingam A, Morgan PS. Women’s Work, Autonomy, and Birth Control: Evidence from Two South India Villages. Population Studies. 1996;50(2):187–201. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon RB. Rural Women at work: Strategies for Development in South Asia. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Dreze J, Murthi M. Fertility, Education, and Development: Evidence from India. Population and Development Review. 2001;27(1):33–63. [Google Scholar]

- Dyson T. On Kinship Structure, Female Autonomy, and Demographic Behavior in India. Population and Development Review. 1983;9(1):35–60. [Google Scholar]

- Engle PL. Influences of mothers’ and fathers’ income on children’s nutritional status in Guatemala. Social Science and Medicine. 1993;37(11):1303–1312. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90160-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engle PL, Bentley M, Pelto G. The role of care in nutrition programmes: current research and a research agenda. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2000;59(1):25–35. doi: 10.1017/s0029665100000045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fikree FF, Pasha O. Role of gender in health disparity: the South Asian context. British Medical Journal. 2004;328(7443):823–826. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7443.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frongillo EA, Jr, de Onis M, Hanson KM. Socioeconomic and demographic factors are associated with worldwide patterns of stunting and wasting of children. Journal of Nutrition. 1997;127(12):2302–2309. doi: 10.1093/jn/127.12.2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost MB, Forste R, Haas DW. Maternal education and child nutritional status in Bolivia: finding the links. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;60(2):395–407. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Dadhich JP, Faridi MM. Breastfeeding and complementary feeding as a public health intervention for child survival in India. Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 2010;77(4):413–418. doi: 10.1007/s12098-010-0049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harpham T, Huttly S, De Silva MJ, Abramsky T. Maternal mental health and child nutritional status in four developing countries. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2005;59(12):1060–1064. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.039180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ORC Macro. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005–06. India. Mumbai: IIPS; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ORC Macro. . National Family Health Survey (NFHS-2), 1998–99. India. Mumbai: IIPS; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jejeebhoy SJ. Women’s Status and Fertility: Successive Cross-Sectional Evidence from Tamil Nadu, India, 1970–80. Studies in Family Planning. 1991;22(4):217–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jejeebhoy SJ. Women’s autonomy in rural India: its dimensions, determinants, and the influence of context. In: Sen HBPaG., editor. Women’s empowerment and demographic processes: moving beyond Cairo. 2000. pp. 204–238. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson FC, Rogers BL. Children’s nutritional status in female-headed households in the Dominican Republic. Social Science and Medicine. 1993;37(11):1293–1301. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones G, Schultink W, Babille M. Child survival in India. Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 2006;73(6):479–487. doi: 10.1007/BF02759891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhu K, Chowdary S, Masthi R. Breast feeding practices and newborn care in rural areas: a descriptive cross-sectional study. Indian Journal of Community Medicine. 2009;34(3):243–246. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.55292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra A, Vanneman R, Kishor S. Fertility, Dimensions of Patriarchy, and Development in India. Population and Development Review. 1995;21(2):281–305. [Google Scholar]

- Mason J, Hunt J, Parker D, Jonsson U. Investing in child nutrition in Asia. Asian Development Review. 1999;17(1,2):1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Mason K. The Status of Women: Conceptual and Methodological Issues in Demographic Studies. Sociological Forum. 1986;1(2):284–300. [Google Scholar]

- Miles-Doan R, Bisharat L. Female autonomy and child nutritional status: the extended-family residential unit in Amman, Jordan. Social Science and Medicine. 1990;31(7):783–789. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90173-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles-Doan R, Brewster KL. The impact of type of employment on women’s use of prenatal-care services and family planning in urban Cebu, the Philippines. Studies in Family Planning. 1998;29(1):69–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JE, Rodgers Y. Mother’s Education and Children’s Nutritional Status: New Evidence from Cambodia. Asian Development Review. 2009;26(1):131–165. [Google Scholar]

- Mistry R, Galal O, Lu M. Women’s autonomy and pregnancy care in rural India: A contextual analysis. Social Science & Medicine; Part Special Issue: Women, Mothers and HIV Care in Resource Poor Settings. 2009;69(6):926–933. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moestue H, Huttly S. Adult education and child nutrition: the role of family and community. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2008;62(2):153–159. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.058578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navaneetham K, Dharmalingam A. Utilization of maternal health care services in Southern India. Social Scienece and Medicine. 2002;55(10):1849–1869. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallikadavath S, Foss M, Stones RW. Antenatal care: provision and inequality in rural north India. Social Scienece and Medicine. 2004;59(6):1147–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popkin BM, Adair L, Akin JS, Black R, Briscoe J, Flieger W. Breast-feeding and diarrheal morbidity. Pediatrics. 1990;86(6):874–882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramalingaswami V, Jonsson U, Rohde J. The progress of nations. New York: Unicef; 1996. The Asian enigma; pp. 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist. 2000;55(1):68–78. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmeer K. Married Women’s Resource Position and Household Food Expenditures in Cebu, Philippines. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67(2):399. [Google Scholar]

- Schuler SR, Hashemi SM. Credit Programs, Women’s Empowerment, and Contraceptive use in Rural Bangladesh. Studies in Family Planning. 1994;25(2):65–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senarath U, Gunawardena NS. Women’s Autonomy in Decision Making for Health Care in South Asia. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health. 2009;21(2):137–143. doi: 10.1177/1010539509331590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shroff MR, Griffiths P, Adair L, Suchindran CM, Bentley M. Maternal autonomy is inversely related to child stunting in Andhra Pradesh, India. Maternal and Child Nutrition. 2009;5(1):64–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2008.00161.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simkhada B, Porter MA, van Teijlingen ER. The role of mothers-in-law in antenatal care decision-making in Nepal: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010;10(1):34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-10-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith H, Ghuman SJ, Lee HJ, Mason KO. Survey on the Status of Women and Fertility: Questionnaires. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Smith LC. The Importance of Women’s Status for Child Nutrition in Developing Countries. IFPRI; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart RC. Maternal depression and infant growth: a review of recent evidence. Maternal and Child Nutrition. 2007;3(2):94–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2007.00088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thang NM, Popkin B. Child malnutrition in Vietnam and its transition in an era of economic growth. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics. 2003;16(4):233–244. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-277x.2003.00449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari R, Mahajan PC, Lahariya C. The Determinants of Exclusive Breast Feeding in Urban Slums: A Community Based Study. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics. 2009;55(1):49–54. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmn037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay UD, Hindin MJ. Do higher status and more autonomous women have longer birth intervals? Results from Cebu, Philippines. Social Scienece and Medicine. 2005;60(11):2641–2655. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visaria L, Jejeebhoy S, Merrick T. From family planning to reproductive health: Challenges facing India. International Family Planning Perspectives. 1999;25:S44–S49. [Google Scholar]

- Vlassoff C. Progress and Stagnation: Changes in Fertility and Women’s Position in an Indian Village. Population Studies. 1992;46(2):195–212. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- WHO; Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group. WHO Child Growth Standards: Length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age: Methods and development. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]