Abstract

Impairments in language processing and thought disorder are core symptoms of schizophrenia. Here we used fMRI to investigate functional abnormalities in the neural networks subserving sentence-level language processing in childhood-onset schizophrenia (COS). Fourteen children with COS (mean age: 13.34; IQ: 95) and 14 healthy controls (HC; mean age: 12.37; IQ: 104) underwent fMRI while performing a semantic judgment task previously shown to differentially engage semantic and syntactic processes. We report four main results. First, different patterns of functional specialization for semantic and syntactic processing were observed within each group, despite similar level of task performance. Second, after regressing out IQ, significant between-group differences were observed in the neural correlates of semantic and, to a lesser extent, syntactic processing, with HC children showing overall greater activity than COS children. Third, while these group differences were not related to effects of medications, a significant negative correlation was observed in the COS group between neuroleptic dosage and activity in the left inferior frontal gyrus for the semantic condition. Finally, COS children's level of thought disorder was significantly correlated with task-related activity in language-relevant networks. Taken together, these findings suggest that children with COS exhibit aberrant patterns of neural activity during semantic, and to a lesser extent syntactic, processing and that these functional abnormalities in language-relevant networks are significantly related to severity of thought disorder.

1. Introduction

Language processing abnormalities and thought disorder are among the hallmark features of schizophrenia (e.g., DeLisi, 2001). Neuroimaging studies investigating the neural basis of these symptoms in schizophrenic adults have regularly identified both abnormal structural organization in language-related circuitry (DeLisi, Szulc, Bertisch, Majcher & Brown, 2006; Walder et al., 2007; Weiss, Dewitt, Goff, Ditman & Heckers, 2005) and aberrant patterns of neural activity in fronto-temporal networks in response to a broad range of tasks with linguistic demands (Kircher, Oh, Brammer & McGuire, 2005; Kuperberg, Deckersbach, Holt, Goff & West, 2007; Kuperberg, West, Lakshmanan & Goff, 2008; Ngan et al., 2003; Ragland et al., 2008; Razafimandimby et al., 2007; Weinstein, Werker, Vouloumanos, Woodward & Ngan, 2006; Weiss et al., 2006). For example, research has found that schizophrenic adults exhibit abnormal neural activity as compared to normal adults when assessing word meaning, with hypoactivation in some frontal regions and hyperactivation in others (Kubicki et al., 2003). Additionally, while normal adults are known to have left-lateralization of neural activity in fronto-temporal regions during language processing, individuals with schizophrenia have been found to exhibit more bilateral, or even right-lateralized activity during speech processing, verbal fluency, and lexical discrimination tasks (Li et al., 2007; Ngan et al., 2003; Weiss et al., 2005). Interestingly, this abnormal lateralization profile has also been observed in individuals at high genetic risk for schizophrenia, who have not yet manifested symptoms of the disease (Li et al., 2007).

Neuroimaging studies of adults with schizophrenia have also attempted to characterize the relationship between severity of thought disorder and brain activity in language-related networks. For instance, severity of thought disorder has been found to be associated with less activation in left temporal regions and with greater activation in the precentral gyrus, cerebellar vermis and caudate when participants were asked to generate verbal descriptions of pictures (Kircher et al., 2001a). Furthermore, adults with schizophrenia who have thought disorder showed decreased activity in the right inferior frontal gyrus and increased activity in the left fusiform gyrus, inferior frontal gyrus and inferior temporal gyrus while generating sentences (vs. reading sentences), as compared to adults with schizophrenia who did not have thought disorder (Kircher et al., 2001a). Severity of thought disorder has also been found to be positively related to increased activity in the left posterior superior temporal lobe (Weinstein et al., 2006) and posterior middle temporal gyrus (Weinstein, Woodward & Ngan, 2007) while listening to speech. Taken together, these findings indicate that severity of thought disorder, a key feature of schizophrenia, is integrally related to the abnormal neural activity observed in language-related networks in adults with schizophrenia.

Substantially less is known about the neural underpinnings of language processing and thought disorder in childhood onset schizophrenia (COS). Despite onset by 13 years of age, these children have hallucinations, delusions, and thought disorder (Caplan, Guthrie, Tang, Komo & Asarnow, 2000; Green et al., 1984; Kolvin, Ounsted, Humphrey & McNay, 1971; McKenna et al., 1994; Russell, Bott & Sammons, 1989), as well as a significant decrease in IQ around the onset of the illness (Gochman et al., 2005), just as observed in the adult disorder. However, cytogenetic abnormalities, found in 10% of the childhood onset cases and a higher rate of familial transmission imply that COS is a more severe form than the adult disease (Addington & Rapoport, 2009). Treatment with typical (Kumra et al., 1996; Spencer & Campbell, 1994) and atypical neuroleptics (Sikich et al., 2008) reduces symptom severity, and clozapine, more than high dose olanzepine, mitigates negative symptoms in treatment resistant subjects (Kumra et al., 2008; Shaw et al., 2006). Clinical predictors of outcome include premorbid impairment, baseline severity of the illness, and illness course in treatment resistant COS (Kumra et al., 2008; Shaw et al., 2006; Sporn et al., 2007). Interestingly IQ, rather than clinical symptoms, predicts the long-term adult social outcome of COS with varying illness severity (Munro, Russell, Murray, Kerwin & Jones, 2002).

The thought disorder of COS includes illogical thinking, loose associations, and under use of cohesive ties (mainly conjunctions, referential cohesion, ambiguous and unclear reference), as well as self-initiated repair (Caplan, Guthrie & Komo, 1996; Caplan et al., 2000). Significantly more thought disorder in younger compared to older individuals with COS reflects onset of the illness during the protracted parallel development of children's discourse skills and language-related brain regions (Caplan et al., 2000). Supporting this conclusion, structural MRI studies have reported that adolescents with schizophrenia have reduced grey matter volume in language-related cortices, including the right superior temporal gyrus, Broca's area, and the parietal operculum (Douaud et al., 2007; Matsumoto et al., 2001). They also have reduced white matter in the arcuate fasciculus as well as decreased anisotropy of the white matter composing the corpus callosum (Douaud et al., 2007). In contrast, children with COS have increased volume of the right superior posterior temporal gyrus, the right hemisphere homologue of Wernicke's area (Taylor et al., 2005) that has been linked to the neural processing of discourse and prosody, important subcomponents of language comprehension (Caplan & Dapretto, 2001; Dapretto, Lee & Caplan, 2005; Lee & Dapretto, 2006; Mitchell, Elliott, Barry, Cruttenden & Woodruff, 2003; St George, Kutas, Martinez & Sereno, 1999). Taken together, at least at the structural level, COS patients manifest significant brain abnormalities in language-related regions, similar to what has been observed in patients with later onset of schizophrenia (Walder et al., 2007; Weiss et al., 2005). Whether children with COS exhibit aberrant patterns of neural activity during language processing in addition to these observed structural abnormalities, however, is still largely unknown.

The present study begins to bridge the gap in our knowledge of the neural underpinnings of language and thought disorder in COS by exploring the relationship between aberrant patterns of neural activity in language-relevant networks and thought disorder. Behavioral research has shown syntactic processing to be relatively preserved in schizophrenic adults, with the most marked deficits observed for semantic processing, from word meanings to discourse (for a review, see Covington et al., 2005). For example, adults with schizophrenia have been reported to show poor semantic categorization of recalled words, indicating poor semantic encoding (Kareken, Moberg & Gur, 1996). Additionally, pronounced semantic deficits in the absence of significantly impaired syntactic processing have been reported in patients with high IQ, indicating that semantic impairment exists even in patients with otherwise intact intellectual abilities (Rodriguez-Ferrera, McCarthy & McKenna, 2001). These findings have been paralleled in behavioral studies of children with COS which identified not only impairment in general language abilities (Hollis, 1995; Jacobsen & Rapoport, 1998; Remschmidt, 2002), but also significant impairment in semantic processing (Phillips, James, Crow & Collinson, 2004) and lesser impairment in syntactic processing (Baltaxe & Simmons, 1995).

A host of neuroimaging studies in healthy adults have shown that syntactic and semantic processes are at least partially distinct at the neural level (for a review, see Bookheimer, 2002). Given this neural dissociation and the independence of semantic and syntactic impairments previously observed in both adults and children with schizophrenia at the behavioral level, we examined brain activity in language-relevant circuits in children with COS via an activation paradigm previously shown to pose differential semantic and syntactic demands during language processing at the sentence level (Dapretto & Bookheimer, 1999). During the task, subjects were asked to determine whether two sentences had the same meaning. Unbeknownst to the subject, the type of linguistic information (semantic vs. syntactic) the subjects had to rely upon in order to make this decision was manipulated. In the semantic condition, the judgment ultimately rested on the comparison between single word meanings, the syntactic structure of the sentences within each pair being the same. In contrast, in the syntactic condition, computing and comparing the syntactic structure of the sentences within each pair was essential to determine whether their meaning differed or not, as the individual word meanings used in each pair of sentences were identical. This paradigm was ideally suited for the present study as it allowed us to explore not only the differences in sentence-level language processing between children with COS and controls, but also to explore how semantic and syntactic processing may be differentially impaired at the neural level in children with COS.

Although a prior study examining these processes in 5- to 6-year-old healthy control (HC) children found that they showed less specialization for semantic and syntactic components of language than adults (Brauer & Friederici, 2007), we expected our sample of older HC children to display some differential frontal activity for semantic and syntactic processing, similar to what we previously observed in adults using the same task. In light of the pronounced semantic deficits seen in schizophrenia (Baltaxe & Simmons, 1995; Covington et al., 2005; Kareken et al., 1996; Phillips et al., 2004; Rodriguez-Ferrera et al., 2001), we expected that the COS children would display abnormal patterns of neural activity during semantic processing as compared to the HC children. Additionally, given the relative preservation of syntactic processing observed in schizophrenia (Covington et al., 2005; Rodriguez-Ferrera et al., 2001), we predicted that the two groups would show more similar patterns of functional specialization during syntactic processing. Furthermore, as a link between aberrant neural activity for language and thought disorder has previously been observed in adults with schizophrenia (e.g., Kircher et al., 2001a), we hypothesized that severity of thought disorder in our sample of COS children would be significantly related to neural activity in fronto-temporal networks subserving language processing. Lastly, as previous research has reported significant impairments of semantic associations in thought disorder (Goldberg et al., 1998; Kuperberg et al., 2007; Stirling, Hellewell, Blakey & Deakin, 2006; Titone & Levy, 2004), we expected that measures of thought disorder would primarily be related to neural activity during semantic, but not syntactic, processing.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

Participants included 14 children with COS (7 males) and 14 HC children (6 males). The two groups were matched on age (M = 13.34, SD = 2.14 and M = 12.37, SD = 2.39, respectively), average slice-to-slice motion during the fMRI scan, as well on task performance (see Results section below). Children with COS, however, differed from the HC children in terms of mean Full Scale IQ (M = 95.36, SD = 11.32 and M = 104.15, SD = 7.87, respectively). Accordingly, IQ was entered as a covariate in the between-group analyses. By report, all subjects were right-handed, native speakers of American English with no history of neurological disorders. We recruited and diagnosed all children using the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders (Kaufman et al., 1997), as described in Caplan et al. (2000).

Twelve of the fourteen subjects with COS were on neuroleptic medication, five on aripiperazole, three on risperidone, one on thorazine, one on haloperidol and quetiapine, one on risperidone and olanzepine, and one on risperidone and aripiperazole. Chlorpromazine (CPZ) equivalent values, measures of the potency of a given neuroleptic and its dosage relative to a set standard (chlorpromazine) (Davis, 1974), were computed to examine possible effects of medication on task-related brain activity. CPZ equivalent scores are subsequently referred to as medication dosage.

2.2 Stimuli and Activation Paradigm

The activation paradigm involved two experimental conditions presented in a blocked design where subjects listened to pairs of sentences and were asked to determine whether the two sentences had the same or different meanings. Subjects indicated their responses in the scanner using a two-button box. In the “semantic” condition, each pair of sentences was identical in all respects except for one word that was replaced with either a synonym or a different word. For example, “The lawyer questioned the witness” and “The attorney questioned the witness” would be a same-meaning pair whereas “The man was attacked by the doberman” and “The man was attacked by the pitbull” would be a pair with different meanings. In the “syntactic” condition, the sentences in each pair were either cast in a different form (i.e., in the active vs. passive voice) or used a different word order (i.e., preposed versus postposed prepositional phrases). For example, “The pool is behind the gate” and “Behind the gate is the pool” would be a same-meaning pair, whereas “West of the bridge is the airport” and “The bridge is west of the airport” would be a pair having different meanings. Importantly, the number of sentences in the active and passive forms, as well as the number of preposed and postposed phrases, was the same in the two conditions. Accordingly, both overall syntactic complexity and related working memory demands were equated across the two conditions. As processing language at the higher level of structure – sentences and discourse – is mandatory when one attends to linguistic stimuli, we expected the subjects to process the sentences in all conditions at both the syntactic and semantic levels; however, we also expected the data to reflect that the relative weight each type of processing had in performing the judgment task varied orthogonally between the two conditions.

In both the syntactic and semantic conditions, participants heard eight sentence pairs (recorded by a female native speaker of American English) presented though a set of magnet-compatible stereo headphones (Resonance Technology, Northridge, CA) at a rate of one pair every 7.5 sec. Stimuli were presented using MacStim 3.2 psychological experimentation software (CogState, West Melbourne, Victoria, Australia). In both the semantic and the syntactic conditions, half of the sentence pairs had the same meaning, the other half had meanings that differed. The order of presentation of same and different meaning pairs was randomized within each condition. Presentation order of the two conditions was counterbalanced within each group. The two activation conditions, each lasting 60 seconds, were interleaved with three 30 second blocks where subjects were instructed to rest; thus, the total experiment lasted 3 minutes and 30 seconds. The total amount of time that subjects were in the scanner varied according to the number of scans (both structural and functional) that were collected for each subject; however, the majority subjects were in the scanner for approximately 30 minutes.

2.3 fMRI Data Acquisition

Images were acquired using a 3.0 Tesla Siemens Allegra MRI scanner. A 2-D spin-echo scout (TR = 4000 msec, TE = 40 msec, matrix size 256 × 256, 4-mm thick, 1-mm gap) was acquired in the sagittal plane to allow prescription of the slices to be obtained in the remaining scans. One functional scan lasting 3 min and 30 sec was acquired covering the whole cerebral volume (84 images; EPI gradient echo sequence; TR = 2500 msec; TE = 25 msec, flip angle = 90°, matrix size = 64 × 64, FOV = 20 cm; 36 slices; 3.125-mm in-plane resolution, 3-mm thick, 1-mm gap). For each participant, a high-resolution structural echo-planar imaging volume was also acquired (TR = 4000 msec, TE = 65 msec, matrix size 128 × 128, FOV = 20 cm, 1.56-mm in-plane resolution, 3-mm thick), coplanar with the functional scans, to allow for spatial registration of each participant's data into a standard coordinate system.

2.4 Thought Disorder Measures

The Story Game (Caplan, Guthrie, Fish, Tanguay & David-Lando, 1989) was used to elicit speech samples from children. Two raters with no knowledge of the children's neurological diagnoses coded videotapes of the Story Game with the Kiddie Formal Thought Disorder Rating Scale (K-FTDS) (Caplan et al., 1989) and transcriptions of the Story Game with Caplan et al.'s modifications of Halliday and Hasan's analysis of cohesion (1976) and Evans (1985) guidelines for repair, as described in detail in Caplan et al. (1992; 1996).

The K-FTDS scores are frequency counts of illogical thinking and loose association ratings divided by the number of sentences (clauses) made by the child. The generalizability coefficient for illogical thinking and Kappa for loose associations were 0.75 (SD=0.15) and 0.66 (SD=0.01), respectively, in a larger sample of 39 children (Caplan et al., 2000).

The cohesion measures, the frequency with which the child used linguistic ties that connect ideas and referents across sentences, include: conjunctions, referential cohesion, lexical cohesion, ellipsis, unclear reference, ambiguous reference, and exophora. The interrater agreement (intraclass correlation) of these scores in a larger sample of 31 children was 0.97 for conjunction, 0.96 for referential cohesion, 0.97 for lexical cohesion, 0.99 for ellipsis, 0.99 for unclear/ambiguous reference, and 0.99 for exophora (Caplan et al., 2000).

The repair scores are frequency measures of how often the child corrects errors in the organization of thoughts (e.g., fillers, false starts, repetition) or linguistic errors (e.g., syntax, semantics, reference) while speaking. Interrater reliability (intraclass correlation) for the repair scores was 0.92 in a larger cohort of 45 children (Caplan et al., 1996).

Summary measures for each of four categories of thought disorder, namely, formal thought disorder (illogical thinking, loose associations, exophora), cohesion (conjunction, referential cohesion, ambiguous and unclear reference, lexical cohesion, substitution, ellipsis), repair of errors in the organization of thinking (fillers, repetition, false starts, postponement), and revision of linguistic errors (word choice revision, syntactic revision, referential revision) were derived as described in Caplan et al. (2006). Scores ranged from 0 (normal) to 1 (schizophrenic). Average thought disorder scores for the children with COS are presented in Table 1. For each child with COS, these four scores, taken to index the degree of thought disorder, were the variables of interest in our analysis of the imaging data.

Table 1. Means and Standard Deviations of Thought Disorders Scores of Children with Schizophrenia.

| Thought Cohesion | Repair of the Organization of Thoughts | Revision of Linguistic Errors | Formal Thought Disorder | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | 0.48 (0.206) |

0.49 (0.181) |

0.50 (0.081) |

0.41 (0.191) |

Scores vary from 0 in normal subjects to 1 in COS

2.5 fMRI Data Analysis

Using Automated Image Registration (AIR 5.2.5; Woods, Grafton, Holmes, Cherry & Mazziotta, 1998; Woods, Grafton, Watson, Sicotte & Mazziotta, 1998) within the LONI pipeline environment (http://pipeline.loni.ucla.edu; Rex, Ma & Toga, 2003), all functional images for each participant were: (a) realigned to correct for head motion and coregistered to their respective high-resolution structural images using a six-parameter rigid-body transformation model; (b) spatially normalized into a Talairach-compatible MR atlas (Woods, Dapretto, Sicotte, Toga & Mazziotta, 1999) using polynominal nonlinear warping; and (c) smoothed using a 6-mm full-width, half-maximum isotropic Gaussian kernel. Following image conversion and preprocessing, the imaging data were analyzed using Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM2; Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, Institute of Neurology, London, UK; http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm).

For each participant, condition effects were estimated according to the general linear model using a canonical hemodynamic response function. The resulting contrast images were entered into second-level analyses using random effects models to allow for inferences to be made at the population level (Friston, Holmes, Price, Büchel & Worsley, 1999). While the researchers performing the imaging experiment were not blind as to the subjects' group assignment since this information was essential for conducting between-group comparisons, IQ and thought disorder assessment was conducted by an independent group of researchers who were blind to group membership, thus preventing any potential bias during data analysis. Within each group, the main contrasts for each condition (Semantic and Syntactic) vs. resting baseline were conservatively thresholded at p < .001 for magnitude (t > 3.85), with correction for multiple comparisons applied at the cluster level (p < .05). The ensuing activation maps were then used to create a joint mask that defined our regions of interest (i.e., search space) for all subsequent comparisons. These between-group analyses were two sample t-tests where IQ was covaried out. These contrasts were slightly more liberally thresholded at p < .01 for magnitude (t > 2.48), with a minimum cluster size of k > 15 (p > .05, uncorrected); as can be seen in the tables, however, the observed activity often greatly exceeded these thresholds. Additionally, percent signal change was calculated for all clusters where significant differences were observed in the between-group analyses. These percent signal calculations were performed by extracting the timeseries from all voxels within the regions of interest using MARsBaR (MARSeille Boîte À Région d'Intérêt;Brett, Anton, Valabregue & Poline, 2002).

3. Results

3.1 Behavioral Reponses

Analyses of the behavioral responses collected during the fMRI scan revealed no significant between-group differences, in either condition, for both response times and accuracy. Across conditions, the mean response times were 5.28 seconds (SD = .38) for the COS children and 5.29 seconds (SD = .31) for the HC children. The accuracy of behavioral responses for the COS group was .79 (SD = .12) and .79 (SD = .09) for the HC group. The reaction times and accuracy scores did not differ between the two conditions. For each group, mean accuracy and reaction time data for each experimental condition are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Means and Standard Deviations of Accuracy and Reaction Times of Behavioral Responses Divided by Condition and Group.

| Reaction Time | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semantic | Syntactic | Total | ||

| Healthy Control Children | M (SD) |

5.19 (0.46) |

5.43 (0.47) |

5.29 (0.35) |

| Children with Schizophrenia | M (SD) |

5.26 (0.37) |

5.31 (0.44) |

5.28 (0.38) |

| Accuracy | ||||

| Semantic | Syntactic | Total | ||

| Healthy Control Children | M (SD) |

0.77 (0.12) |

0.79 (0.20) |

0.79 (0.09) |

| Children with Schizophrenia | M (SD) |

0.75 (0.17) |

0.85 (0.16) |

0.79 (0.12) |

3.2 Within-Group Comparisons

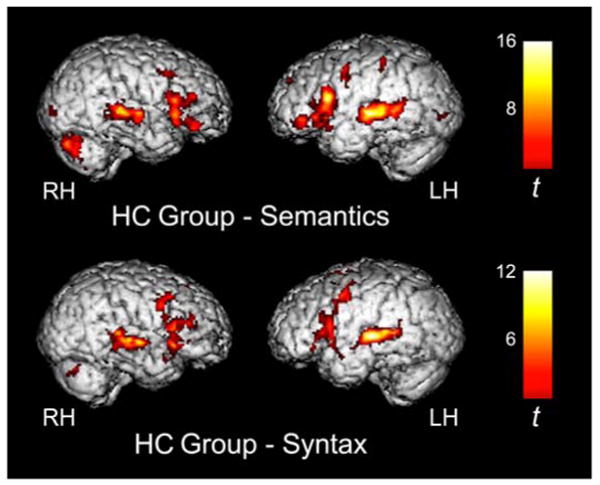

As shown in Figure 1 and Tables 3 and 4, HC children activated a similar network of regions for both the Semantic and Syntactic conditions (vs. resting baseline) which included canonical language areas in left fronto-temporal cortices (inferior frontal gyrus, IFG; superior and middle temporal gyri, STG and MTG) and their right hemisphere homologues, as well as activity in anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), dorsal medial prefrontal cortex (DMPFC), bilateral dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), left premotor cortex, basal ganglia, and cerebellum. In addition, in the Semantic condition only, significant activity was also observed in the left inferior parietal lobule (IPL) and in visual association cortex. In the direct comparisons between the two activation conditions (see Table 5), HC children showed significantly greater activity for the Semantic condition in the most inferior aspect of the left IFG (BA 47), as previously observed in normal adults, as well as in the right cerebellum. In the reversed comparison (Syntactic > Semantic), HC children showed significant activity only in supplementary motor speech area (BA 6).

Figure 1.

Several clusters of significant activity in fronto-temporal language regions were observed in HC children for both the semantic (top) and syntactic (bottom) conditions as compared to resting baseline. Activation maps are displayed at a threshold of t > 3.85, p < 0.001 for magnitude, p < .05, corrected for spatial extent.

Table 3. Peaks of Activation for the Semantic Condition Compared to Resting Baseline in the HC and COS Groups.

| Semantic Condition vs. Resting Baseline | Healthy Control Children | Children with Schizophrenia | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anatomical Regions | BA | x | y | z | t | x | y | z | t | |

| Inferior Frontal Gyrus | 44 | L | -54 | 18 | 16 | 15.02 | -58 | 12 | 28 | 6.66 |

| 45 | L | -56 | 24 | 6 | 10.73 | |||||

| 46 | L | -52 | 30 | 12 | 5.13 | -50 | 24 | 24 | 5.37 | |

| 47 | L | -42 | 26 | 2 | 6.48 | |||||

| 45 | R | 48 | 20 | 4 | 10.04 | |||||

| 46 | R | 36 | 32 | 12 | 5.12 | |||||

| 47 | R | 38 | 40 | -8 | 8.35 | 28 | 24 | -4 | 6.59 | |

| Dorsal Lateral Prefrontal Cortex | 9 | L | -40 | 0 | 42 | 6.31 | ||||

| 9 | R | 34 | 14 | 40 | 5.16 | |||||

| 46 | R | 40 | 38 | 20 | 9.29 | |||||

| Presupplementary Motor Area | 6 | L | -4 | 14 | 54 | 8.06 | ||||

| Premotor Cortex | 6 | L | -52 | 10 | 8 | 5.30 | ||||

| Dorsal Medial Prefrontal Cortex | 8 | L | -14 | 24 | 40 | 7.48 | -8 | 30 | 48 | 7.83 |

| 9 | L | -10 | 50 | 34 | 5.68 | -4 | 40 | 32 | 7.55 | |

| 8 | R | 2 | 22 | 44 | 10.88 | |||||

| 9 | R | 6 | 42 | 30 | 6.90 | 2 | 54 | 30 | 3.99 | |

| Anterior Cingulate Cortex | 32 | R | 4 | 36 | 28 | 7.17 | ||||

| Superior Temporal Gyrus | 22 | L | -56 | -22 | 4 | 16.51 | -56 | -24 | 0 | 5.07 |

| 42 | L | -48 | -30 | 8 | 10.49 | -60 | -20 | 6 | 7.62 | |

| 22 | R | 52 | -32 | 6 | 13.91 | 56 | -14 | 2 | 7.08 | |

| 42 | R | 42 | -26 | 10 | 6.86 | 50 | -30 | 8 | 5.11 | |

| Middle Temporal Gyrus | 21 | L | -54 | -46 | 4 | 7.86 | -56 | -14 | -4 | 6.86 |

| 21 | R | 48 | -42 | 0 | 5.22 | 56 | -34 | -2 | 7.05 | |

| Inferior Parietal Lobule | 40 | L | -44 | -34 | 52 | 5.79 | -50 | -34 | 48 | 5.59 |

| Occipital Gyrus | 18 | L | -32 | -84 | 0 | 7.32 | ||||

| Lingual Gyrus | 18 | R | 14 | -90 | 2 | 6.12 | ||||

| Insula | L | -34 | 22 | 2 | 6.17 | |||||

| Caudate Nucleus | L | -14 | 16 | 10 | 5.82 | |||||

| R | 12 | 6 | 16 | 7.21 | ||||||

| Putamen | L | -26 | 2 | 10 | 8.66 | |||||

| Thalamus | L | -12 | -10 | 8 | 6.69 | |||||

| R | 6 | -8 | 10 | 5.57 | ||||||

| Cerebellum | L | -12 | -76 | -16 | 6.59 | |||||

| R | 24 | -78 | -26 | 10.46 | 12 | -50 | -18 | 5.90 | ||

HC refers to health control subjects; COS refers to subjects with childhood-onset schizophrenia; BA refers to putative Brodmann Area; L and R refer to left and right hemispheres; x, y, and z refer to the Talairach coordinates corresponding to the left-right, anterior-posterior, and inferior-superior axes, respectively; t refers to the highest t score within a region.

Table 4. Peaks of Activation for the Syntactic Condition Compared to Resting Baseline in the HC and COS Groups.

| Syntactic Condition vs. Resting Baseline | Healthy Control Children | Children with Schizophrenia | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anatomical Regions | BA | x | y | z | t | x | y | z | t | |

| Inferior Frontal Gyrus | 44 | L | -58 | 16 | 16 | 8.88 | ||||

| 45 | L | -56 | 22 | 8 | 9.60 | |||||

| 47 | L | -52 | 30 | -8 | 6.02 | |||||

| 44 | R | 44 | 14 | 14 | 5.89 | 46 | 14 | 26 | 5.93 | |

| 45 | R | 52 | 18 | 18 | 6.63 | 36 | 20 | 20 | 6.08 | |

| 47 | R | 40 | 20 | -2 | 6.12 | |||||

| Dorsal Lateral Prefrontal Cortex | 6 | L | -38 | 0 | 46 | 6.30 | ||||

| 9 | L | -38 | 2 | 42 | 6.99 | |||||

| 9 | R | 38 | 14 | 42 | 6.70 | |||||

| 46 | R | 40 | 36 | 24 | 5.96 | |||||

| Presupplementary Motor Area | 6 | L | -2 | 14 | 56 | 10.06 | ||||

| 6 | R | 4 | 10 | 56 | 6.02 | |||||

| Dorsal Medial Prefrontal Cortex | 8 | L | -2 | 22 | 46 | 8.81 | ||||

| 9 | L | -10 | 36 | 32 | 6.46 | |||||

| 8 | R | 2 | 26 | 48 | 10.41 | |||||

| 9 | R | 6 | 36 | 32 | 6.96 | |||||

| Anterior Cingulate Cortex | 32 | R | 2 | 20 | 42 | 10.82 | ||||

| Precentral Gyrus | 4 | L | -32 | -6 | 54 | 5.06 | ||||

| Superior Temporal Gyrus | 22 | L | -64 | -14 | 2 | 8.83 | -52 | -24 | 2 | 6.55 |

| 42 | L | -56 | -18 | 6 | 11.27 | -46 | -30 | 12 | 7.51 | |

| 22 | R | 50 | -10 | 0 | 11.90 | 58 | -28 | 4 | 10.16 | |

| Middle Temporal Gyrus | 21 | L | -56 | -48 | 8 | 5.91 | -64 | -16 | 0 | 5.96 |

| 21 | R | 56 | -18 | -4 | 5.63 | 54 | 0 | -8 | 6.06 | |

| Inferior Parietal Lobule | 40 | L | -42 | -34 | 52 | 5.91 | ||||

| Insula | R | 34 | 16 | 2 | 7.03 | |||||

| Caudate Nucleus | R | 12 | 4 | 18 | 5.41 | |||||

| Putamen | L | -16 | 4 | 8 | 9.94 | |||||

| Thalamus | L | -14 | -14 | 14 | 5.85 | |||||

| R | 8 | -2 | 8 | 5.83 | ||||||

| Cerebellum | L | -16 | -80 | -22 | 5.71 | |||||

| R | 28 | -70 | -24 | 7.49 | ||||||

HC refers to health control subjects; COS refers to subjects with childhood-onset schizophrenia; BA refers to putative Brodmann Area; L and R refer to left and right hemispheres; x, y, and z refer to the Talairach coordinates corresponding to the left-right, anterior-posterior, and inferior-superior axes, respectively; t refers to the highest t score within a region.

Table 5. Peaks of Activation for the Direct Comparisons between the Semantic and Syntactic Conditions in the HC and COS Groups.

| Semantic > Syntactic Condition | Healthy Control Cildren | Children with Schizophrenia | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anatomical Regions | BA | x | y | Z | t | p | k | x | y | z | t | p | k | |

| Inferior Frontal Gyrus | 47 | L | -42 | 40 | -10 | 3.78 | 0.001 | 31 | ||||||

| Cerebellum | R | 32 | -70 | -36 | 4.43 | 0.000 | 25 | |||||||

| Dorsal Medial Prefrontal Cortex | 8 | L | -2 | 34 | 46 | 4.20 | 0.001 | 29 | ||||||

| 8 | L | -6 | 38 | 36 | 3.88 | 0.001 | 97 | |||||||

| Middle Temporal Gyrus | 21 | L | -64 | -42 | 0 | 4.66 | 0.000 | 18 | ||||||

| Caudate Nucleus | R | 10 | 8 | 0 | 3.28 | 0.003 | 14 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Syntactic > Semantic Condition | Healthy Control Cildren | Children with Schizophrenia | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Anatomical Regions | BA | x | y | Z | t | p | k | x | y | z | t | p | k | |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Presupplementary Motor Area | 6 | L | -2 | 10 | 56 | 4.90 | 0.000 | 86 | ||||||

| Middle Temporal Gyrus | 21 | R | 46 | -28 | 0 | 3.64 | 0.001 | 23 | ||||||

| Superior Temporal Gyrus | 22 | L | -48 | -28 | 4 | 4.30 | 0.000 | 22 | ||||||

| 22 | R | 56 | -22 | 6 | 3.87 | 0.001 | 31 | |||||||

HC refers to health control subjects; COS refers to subjects with childhood-onset schizophrenia; BA refers to putative Brodmann Area; L and R refer to left and right hemispheres; x, y, and z refer to the Talairach coordinates corresponding to the left-right, anterior-posterior, and inferior-superior axes, respectively; t refers to the highest t score within a region; p refers to the probability associated with the preceding t value; k refers to the number of voxels in a cluster.

As shown in Figure 2 and Tables 3 and 4, COS children showed overall reduced activity compared to their HC counterparts, both in terms of magnitude and spatial extent. However, COS children did show significant activity in bilateral STG and MTG, as well as in left IPL, for both conditions (vs. resting baseline). In addition, for the Semantic condition, reliable activity was also observed in left IFG, MFG, and premotor cortex, as well as in DMPFC and right cerebellum. For the Syntactic condition, additional reliable activity was only observed in the right IFG. In contrast to what was observed in the HC group, in the direct comparisons between conditions (see Table 5), COS children showed significantly greater activity for the Semantic condition in DMPFC and left MTG. In the reversed comparison (Syntactic > Semantic), the COS group showed significant activity in bilateral STG.

Figure 2.

Children with COS also showed significant task-related activity during the semantic (top) and syntactic (bottom) conditions as compared to resting baseline, albeit to a lesser degree than observed in the HC group. Activation maps are displayed at a threshold of t >3.85, p < 0.001 for magnitude, p < .05, corrected for spatial extent.

3.3 Between-Group Comparisons

Direct between-group comparisons revealed that HC children showed significantly greater activity than COS children for both the Semantic and Syntactic conditions after controlling for IQ (see Table 6). Specifically, for the Semantic condition, significantly greater activity was observed in the HC group (vs. COS group) in medial prefrontal cortex (ACC and DMPFC), left STG, MTG, and putamen, as well as right IFG and cerebellum. Significantly greater activity in DMPFC, left putamen, premotor cortex, and IFG (BA 44) as well as right caudate was observed in the HC > COS comparison for the Syntactic condition. The reverse comparisons (COS > HC) revealed that COS children did not show any significantly greater activity than HC children for either the Semantic or Syntactic conditions. To further explore the magnitude of the activation differences in the regions that were more active in the HC than the COS group, percent signal change (PSC) was calculated for both groups in all of the significant clusters of activation. PSC in these regions ranged from .17 to .44 percent in the HC group and from -.01 to .14 percent in the group of children with COS. These PSC results are shown in Figures 3 and 4.

Table 6. Peaks of Activation for the Between Group Comparisons for the Semantic and Syntactic Conditions (vs. Resting Baseline).

| Healthy Control Children > Children with Schizophrenia | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semantic Condition vs. Resting Baseline | ||||||||

| Anatomical Regions | BA | x | y | z | t | p | k | |

| Inferior Frontal Gyrus | 45 | R | 46 | 22 | 12 | 3.53 | 0.001 | 55 |

| 47 | R | 32 | 30 | -6 | 3.15 | 0.002 | 37 | |

| Dorsal Medial Prefrontal Cortex | 8 | R | 6 | 28 | 36 | 5.44 | 0.000 | 264 |

| Anterior Cingulate Cortex | 32 | R | 10 | 30 | 28 | 5.38 | 0.000 | |

| Superior Temporal Gyrus | 22 | L | -56 | -54 | 14 | 3.89 | 0.000 | 69 |

| Middle Temporal Gyrus | 21 | L | -56 | -50 | 6 | 2.89 | 0.004 | |

| Putamen | L | -30 | 2 | 10 | 3.85 | 0.000 | 62 | |

| Cerebellum | R | 30 | -68 | -28 | 5.17 | 0.000 | 97 | |

|

| ||||||||

| Syntactic Condition vs. Resting Baseline | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Anatomical Regions | BA | x | y | z | t | p | k | |

|

| ||||||||

| Inferior Frontal Gyrus | 44 | L | -48 | 10 | 30 | 3.64 | 0.001 | 110 |

| Premotor Cortex | 6 | L | -38 | 2 | 44 | 4.51 | 0.000 | |

| Dorsal Medial Prefrontal Cortex | 8 | L | -2 | 42 | 36 | 3.28 | 0.002 | 57 |

| 8 | R | 2 | 26 | 46 | 4.29 | 0.000 | 97 | |

| Presupplementary Motor Area | 6 | R | 2 | 16 | 54 | 3.00 | 0.003 | |

| Caudate Nucleus | R | 12 | 14 | 10 | 4.07 | 0.000 | 68 | |

| Putamen | L | -24 | 2 | 8 | 3.40 | 0.001 | 120 | |

BA refers to putative Brodmann Area; L and R refer to left and right hemispheres; x, y, and z refer to the Talairach coordinates corresponding to the left-right, anterior-posterior, and inferior-superior axes, respectively; t refers to the highest t score within a region; p refers to the probability associated with the preceding t value; k refers to the number of voxels in a cluster.

Figure 3.

Percent signal change from resting baseline during the semantic condition was significantly greater in the healthy control children than the children with COS in the left STG, MTG, and putamen as well as the right IFG, ACC, DMPFC, and cerebellum.

Figure 4.

Percent signal change from resting baseline during the syntactic condition was significantly greater in the healthy control children than the children with COS in the left IFG, premotor cortex and putamen, as well as the DMPFC bilaterally and the right presupplemental motor area and caudate.

3.4 Regression Analyses: Medication Dosage

To examine the possible impact of medications on the observed between-group differences in brain activity, regression analyses were performed in the COS group using medication dosage. These analyses revealed that, for the Semantic condition only, level of medication was negatively correlated with activity in left IFG (BA 45, x = -56, y = 28, z = 8, t = 5.51, p < .001, k = 96, p < .05, corrected).

3.5 Regression Analyses: Thought Disorder

To examine how thought disorder might be related to brain activity observed in the COS group, separate regression analyses were performed using the four thought disorder summary scores. Significant correlations between task-related activity and thought disorder measures (see Table 7) were only observed with the scores indexing formal thought disorder (see Figure 5) and the repair of the organization of thoughts (see Figure 6). More specifically, level of formal thought disorder was negatively correlated with activity in left IFG and STG for both conditions, with additional negative correlations observed in DLPFC and DMPFC during the Semantic condition, and in the left insula for the Syntactic condition. For the Semantic condition only, COS children's scores indexing the repair of the organization of thoughts were negatively correlated with activity in bilateral MTG (BA 21), ACC, DMPFC, and right caudate, as well as positively correlated with activity in left STG (BA 42).

Table 7. Peaks of Activation for the Regression Analyses of Thought Disorder Scores.

| Formal Thought Disorder in Children with Schizophrenia | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semantic Condition | ||||||||

| Negative Correlation | ||||||||

| Anatomical Regions | BA | x | y | z | t | p | k | |

| Inferior Frontal Gyrus | 45 | L | -52 | 22 | 4 | 6.72 | 0.000 | 49 |

| DLPFC | 9 | L | -44 | 6 | 38 | 3.65 | 0.002 | 25 |

| DMPFC | 9 | L | -8 | 52 | 32 | 3.93 | 0.001 | 32 |

| Superior Temporal Gyrus | 22 | L | -52 | -28 | 4 | 3.57 | 0.002 | 37 |

|

| ||||||||

| Syntactic Condition | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Negative Correlation | ||||||||

| Anatomical Regions | BA | x | y | z | t | p | k | |

| Inferior Frontal Gyrus | 44 | L | -58 | 12 | 10 | 3.68 | 0.002 | 48 |

| 45 | L | -54 | 16 | 22 | 4.26 | 0.001 | ||

| Superior Temporal Gyrus | 22 | L | -52 | -30 | 4 | 4.36 | 0.000 | 49 |

| Insula | L | -30 | 26 | 4 | 6.10 | 0.000 | 54 | |

|

| ||||||||

| Repair of Organization of Thought in Children with Schizophrenia | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Semantic Condition | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Positive Correlation | ||||||||

| Anatomical Regions | BA | x | y | z | t | p | k | |

| Superior Temporal Gyrus | 22 | L | -50 | -24 | 12 | 4.24 | 0.001 | 40 |

| Negative Correlation | ||||||||

| Anatomical Regions | BA | x | y | z | t | p | k | |

| Pre-supplementary Motor Are | a 6 | L | -10 | 12 | 54 | 3.91 | 0.001 | 257 |

| Anterior Cingular Cortex | 32 | R | 2 | 26 | 34 | 4.86 | 0.000 | |

| Middle Temporal Gyrus | 21 | L | -60 | -30 | 0 | 6.03 | 0.000 | 45 |

| 21 | R | 54 | -18 | 0 | 6.00 | 0.000 | 160 | |

| Caudate Nucleus | R | 12 | 14 | 8 | 6.33 | 0.000 | 68 | |

BA refers to putative Brodmann Area; L and R refer to left and right hemispheres; x, y, and z refer to the Talairach coordinates corresponding to the left-right, anterior-posterior, and inferior-superior axes, respectively; t refers to the highest t score within a region; p refers to the probability associated with the preceding t value; k refers to the number of voxels in a cluster.

Figure 5.

Significant negative correlations were observed between COS children's formal thought disorder scores and activity during the semantic condition in left IFG and STG (shown here at t > 2.68, p < 0.01 for magnitude, p < .05, uncorrected for spatial extent), as well as in DMPFC and DLPFC (see Table 5). The scatter plot illustrates the negative relationship between formal thought disorder scores and activity within the left IFG and STG (r = -0.84; p < 0.001; r = -0.75; p < 0.002, respectively).

Figure 6.

Significant negative correlations were also observed between COS children's repair of organization of thought scores and activity during the semantic condition in bilateral MTG and DMPFC (shown here at t > 2.68, p < 0.01 for magnitude, p < .05, uncorrected for spatial extent), as well as in the right caudate nucleus (see Table 5). The scatter plot illustrates the negative correlations between repair of organization of thought scores and activity within left and right MTG and DMPFC (r = -0.80; p < 0.001; r = -0.81; p < 0.001; r = -0.72; p < 0.003, respectively).

4. Discussion

The results of this fMRI investigation – to our knowledge the first study to examine the functional representation of language in children with COS – revealed clear abnormalities in the neural correlates subserving semantic and, to a lesser extent, syntactic processing in this population. As found in the previous study utilizing the same paradigm with adults (Dapretto & Bookheimer, 1999), HC children showed some degree of functional specialization for semantic and syntactic processing (see Figure 1). This finding supports the hypothesis that functional specialization of semantic and syntactic processing in typically-developing children begins before adulthood.

As predicted, COS children showed overall reduced activity in several fronto-temporal and subcortical regions as compared to HC children (see Figures 1-2 and Tables 3-4 and 6). During the syntactic condition, the COS group had increased right lateralization of neural activity which is consistent with adult studies of language processing in schizophrenia (Li et al., 2007; Ngan et al., 2003; Weiss et al., 2005). Children with COS also exhibited different patterns of functional specialization for semantic and syntactic processing (see Table 5), indicating that semantic and syntactic information may be encoded differently by children with COS. While the differences in syntactic processing between the HC and COS groups were greater than predicted, the results nonetheless indicate dissociable impairments of syntactic and semantic processing at the neural level in the children with COS.

During both conditions, COS children and healthy controls performed equally well behaviorally, in terms of mean scores and variance of the scores, indicating that the groups were able to complete the task with similar competency. This is particularly noteworthy given that non-equivalent behavioral performance can undermine the validity of observed between-group differences when comparing control subjects to a clinical population. Given that the COS group was able to perform as well as the HC group on this task behaviorally, one could speculate that the COS group must be recruiting additional neural regions to compensate for reduced activity in the fronto-temporal regions that controls rely on to perform the task. However, since the HC subjects had significantly more cortical activity and a wider distribution of functional activation than the patient group, our findings do not point to increased effort via activation of alternate regions in the COS group as a means to adequately complete the task.

The general pattern of reduced cortical activity in the schizophrenic subjects parallels the widespread reduced gray matter (volumes, concentration, and thickness) in the inferior frontal gyrus, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, medial frontal lobe, anterior cingulate, superior temporal gyrus, middle temporal gyrus, parietal lobe, putamen, and caudate found in cross-sectional and follow-up studies of childhood (Gogtay, 2008; Thompson et al., 2001; Vidal et al., 2006), adolescent (Douaud et al., 2007; Matsumoto et al., 2001) and adult schizophrenia (for a review, see Glahn et al., 2008). Although gray matter deficits in childhood schizophrenia progress in a back-front direction starting in the parietal region, the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and superior temporal gyrus are the last regions to mature during adolescence in both normal and schizophrenic subjects (Thompson et al., 2001). There is parallel impairment in the front-to-back (frontal-parietal) increase and organization of white matter with a slower rate in the left frontal, right frontal, parietal, and occipital lobes, and particularly in the right parietal lobe in COS (Gogtay et al., 2008). Individuals at high risk for schizophrenia also have abnormalities in brain structure and function that involve inferior frontal, medial temporal and cingulate cortices (Hoptman et al., 2008; Li et al., 2007; Pantelis et al., 2003; Walterfang et al., 2008). Given the cross-sectional study design of the present investigation, it remains to be determined if the abnormal functional representation of semantics and syntax in childhood onset schizophrenia reflects the neuropathology underlying the disorder, onset of the illness during active development of language-related brain regions, or both.

In the present study, we also explored the relationship between formal thought disorder and both semantic and syntactic processing at the neural level. Two separate measures of thought disorder in COS children (formal thought disorder; under use of repair of the organization of thoughts) were found to be meaningfully associated with task-related activity, during the semantic condition, while only formal thought disorder was related to neural activation during the syntactic condition (see Table 7). Both volumetric (Matsumoto et al., 2001; Rajarethinam, DeQuardo, Nalepa & Tandon, 2000; Shenton, Dickey, Frumin & McCarley, 2001; Wisco et al., 2007) and functional studies (Assaf et al., 2006; Kircher et al., 2001a; Kircher et al., 2001b; Kircher et al., 2002; Kuperberg et al., 2007; Kuperberg, Lakshmanan, Caplan & Holcomb, 2006; Kuperberg, McGuire & David, 1998; Kuperberg et al., 2008) in schizophrenic adults and adolescents have indicated thought disorder related abnormalities in the superior temporal gyrus, as well as in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, middle temporal gyrus, inferior frontal gyrus, and anterior cingulate. In our fMRI study, formal thought disorder was significantly related to decreased cortical activity during the semantic condition in the left superior temporal gyrus, dorsolateral prefrontal gyrus, dorsomedial frontal gyrus, and inferior frontal gyrus. Formal thought disorder was also related to neural activity during the syntactic condition in the left inferior frontal gyrus and superior temporal gyrus as well as the insula (Table 7).

The relationship of abnormal cortical activity in the semantic condition with both formal thought disorder and impaired self-initiated repair of communication breakdowns underscores the extensively demonstrated role of abnormal semantic associations in the thought disorder of adult schizophrenia (Goldberg et al., 1998; Kuperberg et al., 2007; Stirling et al., 2006; Titone & Levy, 2004). Furthermore, the association of reduced cortical activity in the ACC with under use of repair of communication breakdowns might reflect the role of the ACC in the on-line monitoring involved in identifying and correcting communication breakdown as well as the reduced volumes described in both childhood (Vidal et al., 2006) and adult schizophrenia in this region (Assaf et al., 2006; Mitelman, Shihabuddin, Brickman, Hazlett & Buchsbaum, 2005). The association between neural responses during the syntactic condition in the left inferior frontal gyrus and superior temporal gyrus and formal thought disorder was an unexpected result. However, given that these regions were also related to formal thought disorder during the semantic condition, this finding may indicate that these regions are affected by the severity of formal thought disorders in relation to language processing more generally. Another unexpected result, the involvement of the left insula in the formal thought disorder of the schizophrenic subjects, also warrants some exploration in future investigations as recent studies have found evidence of cytoarchitectural and volumetric abnormalities (Pennington, Dicker, Hudson & Cotter, 2008) in this brain region in schizophrenia.

Cortical activity did not appear to be related to the dosage of neuroleptics in our patient group, except for the left inferior frontal gyrus where activation was inversely correlated with medication dosage during the semantic condition. This finding suggests that some of the abnormal neural activation in the COS group that was observed during the semantic condition may be attributable medication dosage. However, given that medication was not related to neural activity during the syntactic condition, measures of thought disorder, or accuracy of behavioral responses, there is no indication that medication dosage had a significant effect on linguistic processing in the present study.

Similarly, there is inconsistent evidence regarding neuroleptic effects on neural activation in schizophrenic populations. Studies have identified increased BOLD response during an attention task when switching from a typical to an atypical neuroleptic (Schlagenhauf et al., 2008) and during short-term treatment with an atypical neuroleptic (Schlagenhauf et al., 2008), as well as a differential effect on prefrontal and subcortical brain regions when adding clozapine to risperidone (Molina et al., 2008). However, one study found no difference between neuroleptic treated adult schizophrenic subjects vs. drug naïve schizophrenic subjects (Szulc et al., 2007). In addition, previously established differences in gray and white matter volume as well as neural activation between healthy children and children with COS have also consistently been found to be independent of neuroleptic effects (Gogtay, 2008; Gogtay et al., 2008; Sporn et al., 2003; Thompson et al., 2001; Vidal et al., 2006). In light of the variable findings on the effects of medication dosage in adult and COS populations, the results of the present study need to be confirmed by replication in a larger sample of children with COS.

Other factors that could have influenced the observed neural differences between the COS and HC groups in this study include severity of illness and IQ. Severity of illness might contribute to the reduced cortical activity in the left inferior frontal gyrus during the semantic condition given that activity in this region was significantly related to both formal thought disorder and medication dosage. Unfortunately, severity of illness data were not available in this study, so this could not be explored further. Low IQ is related to the severity of schizophrenia (Daneluzzo et al., 2002) and is consistently found in COS (Gochman et al., 2005). However, abnormalities in the neural correlates subserving semantic and syntactic processing in the COS subjects were unrelated to IQ despite the significantly lower mean IQ of the COS group. Furthermore, the severity of thought disorder in COS has not been shown associated with IQ, (Caplan et al., 2000) which was also the case in the present study. Moreover, prospective studies of brain development in COS have also shown no relationship between the structural abnormalities and IQ (Gogtay, 2008; Thompson et al., 2001; Vidal et al., 2006).

Notwithstanding the study limitations due to the relatively small sample size, possible drug effects, and significantly lower IQ in the COS group, this first study on the neural correlates of linguistic functions in COS demonstrates abnormal patterns of functional specialization during semantic and syntactic processing in the schizophrenic group in both fronto-temporal and subcortical language-related networks. In addition to corroborating the well-established structural abnormalities found in COS in these same regions, these functional abnormalities as well as the observed associations with thought disorder further support the role of impaired semantic associations in the thought disorder of schizophrenia.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants MH 67187 (RC) and NS 32070 (RC) from the National Institute of Health (NIH). For generous support the authors also wish to thank the Brain Mapping Medical Research Organization, Brain Mapping Support Foundation, Pierson-Lovelace Foundation, Ahmanson Foundation, Tamkin Foundation, Jennifer Jones-Simon Foundation, Capital Group Companies Charitable Foundation, Robson Family, William M. and Linda R. Dietel Philanthropic Fund at the Northern Piedmont Community Foundation, and Northstar Fund. This project was in part also supported by grants (RR12169, RR13642 and RR00865) from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health; its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NCR or NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Addington AM, Rapoport JL. The genetics of childhood-onset schizophrenia: When madness strikes the prepubescent. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2009;11(2):156–61. doi: 10.1007/s11920-009-0024-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assaf M, Rivkin PR, Kuzu CH, Calhoun VD, Kraut MA, Groth KM, et al. Abnormal object recall and anterior cingulate overactivation correlate with formal thought disorder in schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;59(5):452–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltaxe CA, Simmons JQ. Speech and language disorders in children and adolescents with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1995;21(4):677–92. doi: 10.1093/schbul/21.4.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookheimer S. Functional MRI of language: New approaches to understanding the cortical organization of semantic processing. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2002;25:151–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauer J, Friederici AD. Functional neural networks of semantic and syntactic processes in the developing brain. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2007;19(10):1609–23. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.10.1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brett M, Anton JL, Valabregue R, Poline JB. Region of interest analysis using an SPM toolbox. Neuroimage. 2002;16(2):1140–1141. [Google Scholar]

- Caplan R, Dapretto M. Making sense during conversation: An fmri study. Neuroreport. 2001;12(16):3625–32. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200111160-00050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan R, Guthrie D, Foy JG. Communication deficits and formal thought disorder in schizophrenic children. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1992;31(1):151. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199201000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan R, Guthrie D, Komo S. Conversational repair in schizophrenic and normal children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35(7):950–8. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199607000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan R, Guthrie D, Fish B, Tanguay PE, David-Lando G. The kiddie formal thought disorder rating scale: Clinical assessment, reliability, and validity. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1989;28(3):408. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198905000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan R, Guthrie D, Tang B, Komo S, Asarnow RF. Thought disorder in childhood schizophrenia: Replication and update of concept. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39(6):771–8. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200006000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan R, Siddarth P, Bailey CE, Lanphier EK, Gurbani S, Donald Shields W, et al. Thought disorder: A developmental disability in pediatric epilepsy. Epilepsy & Behavior : E&B. 2006;8(4):726–35. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covington MA, He C, Brown C, Naçi L, McClain JT, Fjordbak BS, et al. Schizophrenia and the structure of language: The linguist's view. Schizophrenia Research. 2005;77(1):85–98. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daneluzzo E, Arduini L, Rinaldi O, Di Domenico M, Petruzzi C, Kalyvoka A, et al. PANSS factors and scores in schizophrenic and bipolar disorders during an index acute episode: A further analysis of the cognitive component. Schizophrenia Research. 2002;56(1-2):129–36. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00277-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dapretto M, Bookheimer SY. Form and content: Dissociating syntax and semantics in sentence comprehension. Neuron. 1999;24(2):427–32. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80855-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dapretto M, Lee SS, Caplan R. A functional magnetic resonance imaging study of discourse coherence in typically developing children. Neuroreport. 2005;16(15):1661–5. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000183332.28865.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JM. Dose equivalence of the antipsychotic drugs. J Psychiatr Res. 1974;11:65–9. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(74)90071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLisi LE. Speech disorder in schizophrenia: Review of the literature and exploration of its relation to the uniquely human capacity for language. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2001;27(3):481–96. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLisi LE, Szulc KU, Bertisch HC, Majcher M, Brown K. Understanding structural brain changes in schizophrenia. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 2006;8(1):71–8. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2006.8.1/ldelisi. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douaud G, Smith S, Jenkinson M, Behrens T, Johansen-Berg H, Vickers J, et al. Anatomically related grey and white matter abnormalities in adolescent-onset schizophrenia. Brain : A Journal of Neurology. 2007;130(Pt 9):2375–86. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans MA. Self-Initiated speech repairs: A reflection of communicative monitoring in young children. Developmental Psychology. 1985;21(2):365–371. [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Holmes AP, Price CJ, Büchel C, Worsley KJ. Multisubject fmri studies and conjunction analyses. Neuroimage. 1999;10(4):385–96. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1999.0484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glahn DC, Laird AR, Ellison-Wright I, Thelen SM, Robinson JL, Lancaster JL, et al. Meta-Analysis of gray matter anomalies in schizophrenia: Application of anatomic likelihood estimation and network analysis. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;64(9):774–81. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gochman PA, Greenstein D, Sporn A, Gogtay N, Keller B, Shaw P, et al. IQ stabilization in childhood-onset schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2005;77(2-3):271–7. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogtay N. Cortical brain development in schizophrenia: Insights from neuroimaging studies in childhood-onset schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2008;34(1):30–6. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogtay N, Lu A, Leow AD, Klunder AD, Lee AD, Chavez A, et al. Three-Dimensional brain growth abnormalities in childhood-onset schizophrenia visualized by using tensor-based morphometry. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(41):15979–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806485105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg TE, Aloia MS, Gourovitch ML, Missar D, Pickar D, Weinberger DR. Cognitive substrates of thought disorder, I: The semantic system. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155(12):1671–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.12.1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green WH, Campbell M, Hardesty AS, Grega DM, Padron-Gayol M, Shell J, et al. A comparison of schizophrenic and autistic children. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry. 1984;23(4):399–409. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)60317-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliday MAK, Hasan R. Cohesion in spoken and written english. 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Hollis C. Child and adolescent (juvenile onset) schizophrenia. A case control study of premorbid developmental impairments. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;166(4):489–495. doi: 10.1192/bjp.166.4.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoptman MJ, Nierenberg J, Bertisch HC, Catalano D, Ardekani BA, Branch CA, et al. A DTI study of white matter microstructure in individuals at high genetic risk for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen LK, Rapoport JL. Research update: Childhood-Onset schizophrenia: Implications of clinical and neurobiological research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 1998;39(1):101–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kareken DA, Moberg PJ, Gur RC. Proactive inhibition and semantic organization: Relationship with verbal memory in patients with schizophrenia. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society : JINS. 1996;2(6):486–93. doi: 10.1017/s135561770000165x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, et al. Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(7):980–8. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircher TT, Bulimore ET, Brammer MJ, Williams SC, Broome MR, Murray RM, et al. Differential activation of temporal cortex during sentence completion in schizophrenic patients with and without formal thought disorder. Schizophrenia Research. 2001a;50(1-2):27–40. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(00)00042-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircher TT, Liddle PF, Brammer MJ, Williams SC, Murray RM, McGuire PK. Neural correlates of formal thought disorder in schizophrenia: Preliminary findings from a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001b;58(8):769–74. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircher TT, Liddle PF, Brammer MJ, Williams SC, Murray RM, McGuire PK. Reversed lateralization of temporal activation during speech production in thought disordered patients with schizophrenia. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32(3):439–49. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702005287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircher TT, Oh TM, Brammer MJ, McGuire PK. Neural correlates of syntax production in schizophrenia. The British Journal of Psychiatry : The Journal of Mental Science. 2005;186:209–14. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.3.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolvin I, Ounsted C, Humphrey M, McNay A. Studies in the childhood psychoses. II. The phenomenology of childhood psychoses. The British Journal of Psychiatry : The Journal of Mental Science. 1971;118(545):385–95. doi: 10.1192/bjp.118.545.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubicki M, McCarley RW, Nestor PG, Huh T, Kikinis R, Shenton ME, et al. An fmri study of semantic processing in men with schizophrenia. Neuroimage. 2003;20(4):1923–1933. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00383-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumra S, Frazier JA, Jacobsen LK, McKenna K, Gordon CT, Lenane MC, et al. Childhood-Onset schizophrenia. A double-blind clozapine-haloperidol comparison. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1996;53(12):1090–7. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830120020005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumra S, Kranzler H, Gerbino-Rosen G, Kester HM, De Thomas C, Kafantaris V, et al. Clozapine and “high-dose” olanzapine in refractory early-onset schizophrenia: A 12-week randomized and double-blind comparison. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;63(5):524–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuperberg GR, Deckersbach T, Holt DJ, Goff D, West WC. Increased temporal and prefrontal activity in response to semantic associations in schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64(2):138. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.2.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuperberg GR, Lakshmanan BM, Caplan DN, Holcomb PJ. Making sense of discourse: An fmri study of causal inferencing across sentences. Neuroimage. 2006;33(1):343–61. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuperberg GR, McGuire PK, David AS. Reduced sensitivity to linguistic context in schizophrenic thought disorder: Evidence from on-line monitoring for words in linguistically anomalous sentences. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107(3):423–34. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.3.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuperberg GR, West WC, Lakshmanan BM, Goff D. Functional magnetic resonance imaging reveals neuroanatomical dissociations during semantic integration in schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;64(5):407–18. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SS, Dapretto M. Metaphorical vs. Literal word meanings: Fmri evidence against a selective role of the right hemisphere. Neuroimage. 2006;29(2):536–44. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Branch CA, Ardekani BA, Bertisch H, Hicks C, DeLisi LE. Fmri study of language activation in schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and in individuals genetically at high risk. Schizophrenia Research. 2007;96(1-3):14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto H, Simmons A, Williams S, Hadjulis M, Pipe R, Murray R, et al. Superior temporal gyrus abnormalities in early-onset schizophrenia: Similarities and differences with adult-onset schizophrenia. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158(8):1299–304. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.8.1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna K, Gordon CT, Lenane M, Kaysen D, Fahey K, Rapoport JL. Looking for childhood-onset schizophrenia: The first 71 cases screened. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1994;33(5):636–44. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199406000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell RL, Elliott R, Barry M, Cruttenden A, Woodruff PW. The neural response to emotional prosody, as revealed by functional magnetic resonance imaging. Neuropsychologia. 2003;41(10):1410–21. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(03)00017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitelman SA, Shihabuddin L, Brickman AM, Hazlett EA, Buchsbaum MS. Volume of the cingulate and outcome in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2005;72(2-3):91–108. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina V, Tamayo P, Montes C, De Luxán A, Martin C, Rivas N, et al. Clozapine may partially compensate for task-related brain perfusion abnormalities in risperidone-resistant schizophrenia patients. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 2008;32(4):948–54. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro JC, Russell AJ, Murray RM, Kerwin RW, Jones PB. IQ in childhood psychiatric attendees predicts outcome of later schizophrenia at 21 year follow-up. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2002;106(2):139–42. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.02030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngan ET, Vouloumanos A, Cairo TA, Laurens KR, Bates AT, Anderson CM, et al. Abnormal processing of speech during oddball target detection in schizophrenia. Neuroimage. 2003;20(2):889–97. doi: 10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00385-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantelis C, Velakoulis D, McGorry PD, Wood SJ, Suckling J, Phillips LJ, et al. Neuroanatomical abnormalities before and after onset of psychosis: A cross-sectional and longitudinal MRI comparison. Lancet. 2003;361(9354):281–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12323-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennington K, Dicker P, Hudson L, Cotter DR. Evidence for reduced neuronal somal size within the insular cortex in schizophrenia, but not in affective disorders. Schizophrenia Research. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips TJ, James AC, Crow TJ, Collinson SL. Semantic fluency is impaired but phonemic and design fluency are preserved in early-onset schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2004;70(2-3):215–22. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragland JD, Moelter ST, Bhati MT, Valdez JN, Kohler CG, Siegel SJ, et al. Effect of retrieval effort and switching demand on fmri activation during semantic word generation in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2008;99(1-3):312–23. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajarethinam RP, DeQuardo JR, Nalepa R, Tandon R. Superior temporal gyrus in schizophrenia: A volumetric magnetic resonance imaging study. Schizophrenia Research. 2000;41(2):303–12. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razafimandimby A, Maïza O, Hervé PY, Lecardeur L, Delamillieure P, Brazo P, et al. Stability of functional language lateralization over time in schizophrenia patients. Schizophrenia Research. 2007;94(1-3):197–206. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remschmidt H. Early-Onset schizophrenia as a progressive-deteriorating developmental disorder: Evidence from child psychiatry. Journal of Neural Transmission (Vienna, Austria : 1996) 2002;109(1):101–17. doi: 10.1007/s702-002-8240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rex DE, Ma JQ, Toga AW. The LONI pipeline processing environment. Neuroimage. 2003;19(3):1033–48. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00185-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Ferrera S, McCarthy RA, McKenna PJ. Language in schizophrenia and its relationship to formal thought disorder. Psychological Medicine. 2001;31(2):197–205. doi: 10.1017/s003329170100321x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell AT, Bott L, Sammons C. The phenomenology of schizophrenia occurring in childhood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1989;28(3):399–407. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198905000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlagenhauf F, Wüstenberg T, Schmack K, Dinges M, Wrase J, Koslowski M, et al. Switching schizophrenia patients from typical neuroleptics to olanzapine: Effects on BOLD response during attention and working memory. European Neuropsychopharmacology : The Journal of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;18(8):589–99. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw P, Sporn A, Gogtay N, Overman GP, Greenstein D, Gochman P, et al. Childhood-Onset schizophrenia: A double-blind, randomized clozapine-olanzapine comparison. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63(7):721–30. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenton ME, Dickey CC, Frumin M, McCarley RW. A review of MRI findings in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2001;49(1-2):1–52. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00163-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikich L, Frazier JA, McClellan J, Findling RL, Vitiello B, Ritz L, et al. Double-Blind comparison of first- and second-generation antipsychotics in early-onset schizophrenia and schizo-affective disorder: Findings from the treatment of early-onset schizophrenia spectrum disorders (TEOSS) study. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165(11):1420–31. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08050756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer EK, Campbell M. Children with schizophrenia: Diagnosis, phenomenology, and pharmacotherapy. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1994;20(4):713–25. doi: 10.1093/schbul/20.4.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sporn AL, Greenstein DK, Gogtay N, Jeffries NO, Lenane M, Gochman P, et al. Progressive brain volume loss during adolescence in childhood-onset schizophrenia. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160(12):2181–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.12.2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sporn AL, Vermani A, Greenstein DK, Bobb AJ, Spencer EP, Clasen LS, et al. Clozapine treatment of childhood-onset schizophrenia: Evaluation of effectiveness, adverse effects, and long-term outcome. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46(10):1349–56. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31812eed10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St George M, Kutas M, Martinez A, Sereno MI. Semantic integration in reading: Engagement of the right hemisphere during discourse processing. Brain : A Journal of Neurology. 1999;122(Pt 7):1317–25. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.7.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirling J, Hellewell J, Blakey A, Deakin W. Thought disorder in schizophrenia is associated with both executive dysfunction and circumscribed impairments in semantic function. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36(4):475–84. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szulc A, Galińska B, Tarasów E, Kubas B, Dzienis W, Konarzewska B, et al. N-Acetylaspartate (NAA) levels in selected areas of the brain in patients with chronic schizophrenia treated with typical and atypical neuroleptics: A proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H MRS) study. Medical Science Monitor : International Medical Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research. 2007;13 1:17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JL, Blanton RE, Levitt JG, Caplan R, Nobel D, Toga AW. Superior temporal gyrus differences in childhood-onset schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2005;73(2-3):235–41. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson PM, Vidal C, Giedd JN, Gochman P, Blumenthal J, Nicolson R, et al. Mapping adolescent brain change reveals dynamic wave of accelerated gray matter loss in very early-onset schizophrenia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(20):11650–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201243998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titone D, Levy DL. Lexical competition and spoken word identification in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2004;68(1):75–85. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00212-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal CN, Rapoport JL, Hayashi KM, Geaga JA, Sui Y, McLemore LE, et al. Dynamically spreading frontal and cingulate deficits mapped in adolescents with schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63(1):25–34. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walder DJ, Seidman LJ, Makris N, Tsuang MT, Kennedy DN, Goldstein JM. Neuroanatomic substrates of sex differences in language dysfunction in schizophrenia: A pilot study. Schizophrenia Research. 2007;90(1-3):295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walterfang M, McGuire PK, Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Velakoulis D, Wood SJ, et al. White matter volume changes in people who develop psychosis. The British Journal of Psychiatry : The Journal of Mental Science. 2008;193(3):210–5. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.043463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein S, Werker JF, Vouloumanos A, Woodward TS, Ngan ET. Do you hear what I hear? Neural correlates of thought disorder during listening to speech in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2006;86(1-3):130–7. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]