Abstract

Background

To examine the rates and predictors of deep peri-prosthetic infections following shoulder hemi-arthroplasty.

Methods

We used prospectively collected Institutional Registry data on all primary shoulder hemi-arthroplasty patients from 1976–2008. We estimated survival-free of deep peri-prosthetic infections using the Kaplan-Meier survival curves. Using univariate Cox regression analyses, we examined the association of patient-related factors (age, gender, body mass index (BMI)), comorbidity (Charlson index), ASA grade, underlying diagnosis and implant fixation with the risk of infection.

Results

1,349 patients, with mean age 63 years (standard deviation, 16) with 63% women, underwent 1,431 primary shoulder hemi-arthroplasties. Mean follow-up was 8 years (standard deviation, 7 years). Fourteen deep peri-prosthetic infections occurred during the follow-up, confirmed by medical record review. Most common organisms were staphylococcus aureus, staphylococcus coagulase negative and Propionobacterium acnes, each accounting for 3 cases (21% each). The 5-, 10- and 20-year prosthetic infection-free rates (95% confidence interval) were 98.9% (98.3%, 99.5%), 98.7% (98.1%, 99.4%) and 98.7% (98.1%, 99.4%) respectively. None of the factors evaluated were significantly associated with risk of prosthetic infection after primary shoulder hemi-arthroplasty, except that an underlying diagnosis of trauma was associated with significantly higher hazard ratio of 3.18 (95% confidence interval, 1.06–9.56) of infection compared to all other diagnoses (p=0.04). A higher body mass index showed a non-statistical trend towards association with higher hazard (p=0.13).

Conclusion

The periprosthetic infection rate after shoulder hemi-arthroplasty was low, estimated at 1.3% at 20-year follow-up. An underlying diagnosis of trauma was associated with a higher risk of periprosthetic infection. These patients should be observed closely for development of infection.

Keywords: Shoulder hemiarthroplasty, humeral head replacement, infection, age

BACKGROUND

Shoulder arthroplasty is the surgical treatment for end-stage shoulder pain due to multiple causes including, but not limited to, arthritis, rotator cuff disease, trauma and tumors. Total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) and shoulder hemiarthroplasty, also commonly known as humeral head replacement (HHR), are two commonly available surgical options 1. HHR is associated with significant improvements in pain, function and quality of life, although the improvements are slightly less optimal than those with TSA 1; 10. One of the modes of early failure is infection, associated with unsatisfactory results 7–8; 13. Previous studies have reported prevalence of infection of shoulder arthroplasty combined patients with TSA and HHR and infection rate was ranged from 0.4% to 2.9% 3; 14. Hematoma formation was found to be a risk factor for periprosthetic infection after shoulder arthroplasty in a single-center study 2.

We are unaware of any study of prevalence, etiology and predictors of periprosthetic infection in a cohort of patients with HHR. Our study aimed to fill this knowledge gap by studying deep periprosthetic infections in a patient cohort that underwent HHR at a large volume medical center using prospectively collected data over 3 decades.

METHODS

We used the Mayo Clinic Total Joint Registry to identify and follow-up every patient who had undergone primary shoulder hemiarthroplasty/HHR. This study was a retrospective review of prospectively collected data. The Mayo Clinic Total joint registry has prospectively captured data on every shoulder arthroplasty since the shoulder arthroplasty surgery was first performed in 1976 at the Mayo Clinic. Our study cohort consisted of all adults aged 18 years or older who underwent primary HHR performed at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, in a 33-year period from 1976 to 2008. As a part of the Mayo Clinic Total joint registry, each patient who undergoes shoulder arthroplasty at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota is followed prospectively. Clinical follow-up visits are scheduled at 1-, 2- and 5-years, and every 5 years thereafter, monitoring for complications such as fracture, dislocation, additional surgeries, infection, pain, function etc. Patients failing to return for clinic follow-up are contacted with a mailed standardized shoulder questionnaire and requested to send their radiographs. Patients failing to return the questionnaire are interviewed on the phone by trained registry staff using standardized shoulder questionnaire, and regarding complications of shoulder arthroplasty and additional surgeries. Data, including operative reports for indication and operative findings, are requested for surgeries at other hospitals. For this study, we validated each deep periprosthetic infection documented in the total joint registry by performing a complete medical review and standardized data abstraction. Patient characteristics (age, gender, body mass index), implant fixation (cemented versus uncemented), comorbidity, underlying diagnosis and American Society of Anesthesiologist (ASA) class (higher class =worse physical status) were obtained from Joint Registry and other electronic databases. Comorbidity was measured with Deyo-Charlson index, a validated measure consisting of a weighted scale of 17 comorbidities 4; higher score indicates more comorbidity.

Since there is no universal definition of deep periprosthetic infection, a definition was developed a priori in discussion with two experienced orthopedic surgeons (J.W.S. and R.H.C.) and a rheumatologist-epidemiologist (J.A.S). We defined infected shoulder hemi-arthroplasty by the presence of one or more of the following: (1) positive joint fluid culture from needle aspiration, arthroscopic procedure, fluid obtained at surgery or fluid draining from a wound communicating with the humerus; (2) clinically suspected septic arthritis plus either culture-negative purulent or serosanguinuous joint fluid or necrotic joint tissue (or culture not performed) or positive blood culture; (3) frank pus/purulent material at surgery; and, (4) positive synovial or bone tissue culture. Infections that were limited to the skin and subcutaneous tissue without any extension beyond the facial planes were categorized as superficial infections.

Baseline characteristics were expressed as mean and standard deviation or number and percentage as appropriate. Kaplan-Meier survival was used to estimate 5-, 10- and 20-year survival-free of shoulder implant infection. Observations were censored at the time of revision arthroplasty or death, implying that once either event (infection or death) was recorded for a patient, that patient did not contribute any more observation period. Censoring is a standard method used in time-to-event analysis, since it allows each patient to be observed until the time they have the event of interest for the first time, i.e. infection in index HHR in our case; no patient contributes more than one observation (only one infection counted per patient). Cox regression analyses were used to assess the univariate associations of patient characteristics of interest with the risk of periprosthetic infections. We had planned to perform multivariable-adjusted analyses, including all variables with p<0.10, if sufficient events were available. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

During the study period 1976–2008, 1,349 patients, with mean age 63 years (standard deviation (SD), 16) with 63% women, underwent 1,431 HHRs. Mean (SD) follow-up was 8 years (7 years), and follow-up was censored at revision arthroplasty. Mean BMI was 28 kg/m2 (SD, 6), mean Charlson index was 1.4 (SD, 2), and 60% had cemented implant. ASA grade was 1 or 2 in 49% and 3 or 4 in 39%; the underlying diagnosis was trauma in 35%, osteoarthritis in 24%, rheumatoid arthritis in 16%, rotator cuff disease in 10%, tumor in 10% and other diagnoses in 5%.

Prevalence of Prosthetic Infections and Overall Infection-Free Survival

There were twenty-one deep periprosthetic infections recorded during the follow-up in the Mayo Clinic Total Joint Registry following shoulder hemiarthroplasty. Of these 14 deep infections were confirmed on medical record review. In all confirmed cases, an organism was identified on gram stain or culture or both (n=14). Of the 7 infections identified using registry, but unconfirmed or confirmed not to be deep infections, four patients had superficial infection or hematoma, records were not available for one patient and no evidence of infection was present in two patients.

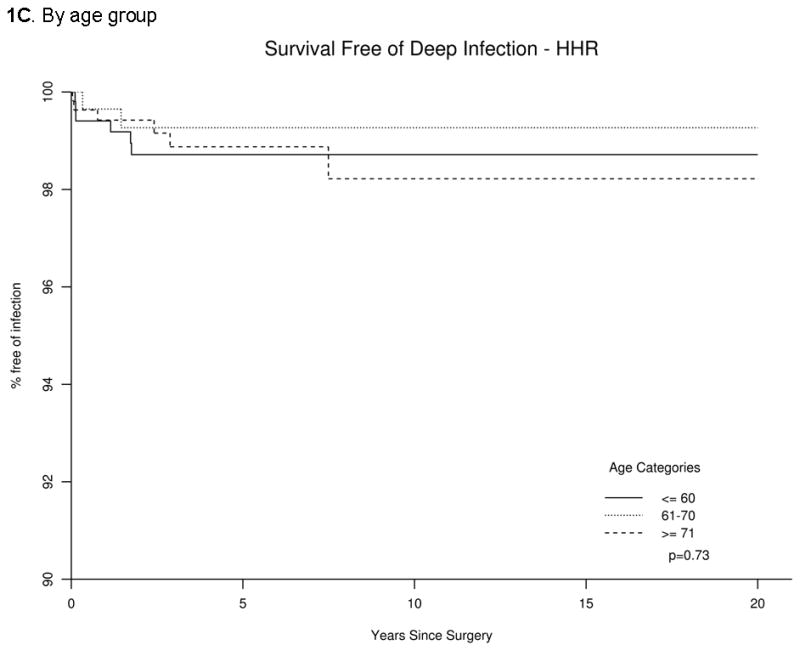

Estimates of survival-free of deep periprosthetic infection (95% confidence interval) at 5-, 10- and 20-years were 98.9% (98.3%, 99.5%), 98.7% (98.1%, 99.4%) and 98.7% (98.1%, 99.4%), respectively. Infection-free survival by gender, age and BMI and overall infection-free survival are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Infection-free Survival following Shoulder Hemiarthroplasty/Humeral Head Replacement (HHR) overall (1A), by gender (1B), age group (1C) and body mass index (BMI) (1D).

The p-value represents comparison of overall infection-free survival by each characteristic in panels B, C and D.

Etiology for Prosthetic Joint Infection after HHR

Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus coagulase negative and Propionibacterium were the most common organisms seen in 21% each of all prosthetic infections (3 patients each). One patient each had the following underlying organism: Clostridium species, Pseudomonas species, Bacillus species, Enterococcus and Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Of the 14 periprosthetic infections, 6 occurred during 1976–1990, 4 during 1991–2000 and 4 during 2001–2008 and the underlying organisms [time from arthroplasty to diagnosis] were as follows: (1) 1976–1990 (n=6): Staphylococcus aureus, n=2 [45 days, 119 days]; Stapyhlococcus coagulase negative, n=2 [412 days, 631 days]; Clostridium species, n=1 [1,036 days]; Pseudomonas, n=1 [522 days]; (2) 1991–2000 (n=4): 1 each of Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) [2,698 days], Staphylococcus aureus [40 days], Stapyhlococcus coagulase negative [13 days] and Enterococcus species [27 days]; (3) 2000–2008 (n=4): Propionibacterium acnes, n=3 [47 days, 868 days, 620 days]; Bacillus species, n=1 [275 days].

By categorizing the infections by the time from arthroplasty to the diagnosis of deep periprosthetic infections were as follows: (1) Early, <6-months (n=6): Staphylococcus aureus(n=3), Stapyhlococcus coagulase negative (n=1), Propionibacterium acnes (n=1) and Enterococcus species (n=1); (2) Intermediate-term infections, 6–24 months (n=5): Stapyhlococcus coagulase negative (n=2), Propionibacterium acnes (n=1), Pseudomonas (n=1) and Bacillus species (n=1); and (3) Late infections, >24-months (n=3): Propionibacterium acnes (n=1), Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (n=1) and Clostridium species (n=1).

Examining the distribution of infections by each diagnosis, we found that nine infections occurred in patients with trauma (three with Staphylococcus coagulase-negative, two with Staphylococcus aureus, two with P.acnes, one with Clostridium species and one with Enterococcus species), three infections occurred in patients with osteoarthritis (one each with Staphylococcus aureus, P.acnes and Bacillus species) and one infection each in patients with tumor (Pseudomonas species) and rotator cuff disease (MRSA).

Univariate Association of Patient Characteristics with Deep Periprosthetic Infections

Gender, age, comorbidity, ASA class, and cement status were not associated with risk of periprosthetic infection (Table 1). The underlying diagnosis, when categorized as osteoarthritis versus others was not significantly associated with infection. An underlying diagnosis of trauma was associated with significantly increase hazard of periprosthetic infection (p=0.04; Table 1). BMI≥30 had a non-significant trend of association with hazard of periprosthetic infection (p=0.13). The number of events (n=14) was insufficient to perform multivariable analyses.

Table 1.

Univariate risk factors for deep periprosthetic infection after Shoulder hemiarthroplasty

| Variable | Kaplan-Meier estimates (95% CI) | Cox proportional hazards | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| # shoulders | # events | 5 years | 10 years | 20 years | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

|

| |||||||

| Female | 898 | 7 | 99.1 (98.5,99.8) | 99.1 (98.5,99.8) | 99.1 (98.5,99.8) | 0.57 (0.20,1.63) | 0.29 |

| Male | 533 | 7 | 98.5 (97.3,99.7) | 98.0 (96.5,99.5) | 98.0 (96.5,99.5) | 1.0 (ref) | |

| Age at Surgery | 0.73 | ||||||

| ≤60 years | 539 | 6 | 98.7 (97.7,99.7) | 98.7 (97.7,99.7) | 98.7 (97.7,99.7) | 1.0 (ref) | |

| 61–70 years | 328 | 2 | 99.3 (98.3,100) | 99.3 (98.3,100) | 99.3 (98.3,100) | 0.58 (0.12,2.86) | 0.50 |

| ≥71 years | 564 | 6 | 98.9 (97.9,99.9) | 98.2 (96.6,99.9) | 98.2 (96.6,99.9) | 1.03 (0.32,3.32) | 0.97 |

| Age (per 10 years)a | 0.95 (0.67,1.34) | 0.76 | |||||

| Deyo-Charlson indexb | 1.05 (0.85,1.30) | 0.64 | |||||

| Body Mass Indexc | 0.13 | ||||||

| < 24.9 kg/m2 | 335 | 1 | 99.6 (98.9,100) | 99.6 (98.9,100) | 99.6 (98.9,100) | 1.0 (ref) | |

| 25–29.9 kg/m2 | 349 | 6 | 98.2 (96.7,99.8) | 97.3 (94.9,99.7) | 97.3 (94.9,99.7) | 5.73 (0.69,47.68) | |

| 30–39.9 kg/m2 | 291 | 1 | 99.5 (98.6,100) | 99.5 (98.6,100) | 99.5 (98.6,100) | 1.22 (0.08,19.57) | |

| ≥40 kg/m2 | 51 | 1 | 97.9 (94.0,100) | 97.9 (94.0,100) | 97.9 (94.0,100) | 7.41 (0.46,120.3) | |

| ASAd | 0.48 | ||||||

| Class (1,2) ‡ | 489 | 5 | 99.0 (98.1,100) | 98.3 (96.5,100) | 98.3 (96.5,100) | 1.0 (ref) | |

| Class (3,4) | 501 | 3 | 99.2 (98.4,100) | 99.2 (98.4,100) | N/A | 0.60 (0.15,2.50) | |

| Implant Fixatione | |||||||

| No cement | 575 | 6 | 98.9 (98.0,99.9) | 98.4 (97.1,99.8) | 98.4 (97.1,99.8) | 1.0 (ref) | |

| Cement | 870 | 8 | 98,9 (98.2,99.7) | 98.9 (98.2,99.7) | 98.9 (98.2,99.7) | 0.88 (0.30,2.56) | 0.82 |

| Diagnosis | |||||||

| No osteoarthritise | 1083 | 11 | 98.9 (98.3,99.6) | 98.7 (97.9,99.5) | 98.7 (97.9,99.5) | 1.0 (ref) | |

| Osteoarthritis | 348 | 3 | 98.9 (97.6,100) | 98.9 (97.6,100) | 98.9 (97.6,100) | 0.94 (0.26,3.35) | 0.92 |

| Diagnosisf | |||||||

| No trauma | 939 | 5 | 99.5 (98,9,100) | 99.2 (98.4,100) | 99.2 (98.4,100) | 1.0 (ref) | |

| Trauma | 492 | 9 | 97.9 (96.6,99.3) | 97.9 (96.6,99.3) | 97.9 (96.6,99.3) | 3.18 (1.06,9.56) | 0.04 |

Age at surgery;

Hazard ratio is for 1-point change in Deyo-Charlson index;

available from 9/1/1987 to present;

available from 11/1/1988 to present;

Humeral and/or glenoid components were cemented. ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologist; CI, confidence interval; N/A, not applicable since there were no additional events

No osteoarthritis category included the following diagnoses: Rheumatoid arthritis, rotator cuff disease, tumor, trauma and other.

No osteoarthritis category included the following diagnoses: Rheumatoid arthritis, rotator cuff disease, tumor, trauma and other.

Diagnosis was also examined slightly differently by underlying trauma versus other diagnosis (no trauma), due to observation of high number of events in the trauma group.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we examined the risk of periprosthetic infections following shoulder hemiarthroplasty/HHR in a cohort accumulated over a 33-year period, 1976–2008. Infection-free survival was high at 99% at 20-years post-surgery. Only 14/1,431 HHRs had deep periprosthetic infection during the follow-up. Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus coagulase negative and Propionibacterium acnes were the commonest organisms. Age, gender, implant fixation, comorbidity or ASA class were not associated with hazard of periprosthetic infection. An underlying diagnosis of trauma was associated with a higher risk of periprosthetic infection. Only 15% patients had nonstandard procedures (10% tumor and 5% other diagnoses). Several findings in this study are novel and merit further discussion. These findings must be interpreted considering the strengths and limitations of this study.

This study was based on a large prospective joint-registry. The presence and the type of each deep periprosthetic infection following shoulder hemi-arthroplasty were confirmed with medical records as the gold standard, thus validating the infection outcome. Most surgeries at this large tertiary center have been performed by two main surgeons (R.H.C. and J.W.S.), which reduces surgical factor-related variability. Our study has several limitations. These results may not be generalizable to other community practices, since Mayo Clinic provides medical care to the local residents as well as referral specialty care. The frequency of infection and/or type of organisms may differ by type of medical center (community versus university hospital) and geography. Despite inclusion of 33-year data, we found only 14 confirmed periprosthetic infections, limiting us from performing multivariable-adjusted analyses and making our results liable to type II error, i.e., missing important associations when they actually may have existed. Given the rarity of periprosthetic infection and even larger potential ascertainment biases in large datasets such as Medicare and Veterans Affairs databases, due to absence of specific prospective data collection regarding arthroplasty-related complications, a dataset such as the Mayo Clinic Joint Registry was invaluable. Our ability to confirm each infection by detailed medical record review of each patient was a particular strength of this study. Another strength of our study was the active surveillance of all patients who undergo shoulder arthroplasty for infection with a rigorous follow-up using multiple strategies.

With an infection-free survival rate of approximately 99% at 20-years, we noted a 1.3% infection rate at 20-year follow-up, which is within the range of 0.4%–2.9% infection rate reported previously, with shorter mean follow-up 3; 14, but higher than the 0.4% in a systematic review of 3,584 patients at mean follow-up of 5-years 15. All previous studies had shorter mean follow-up than our study. The low infection rate noted in this study may partially be due to the choice of healthier cohort of patients with shoulder disease that are fit/healthy to undergo arthroplasty and underreporting and capture of some infections. One may speculate if longer empiric antibiotic prophylaxis at the time of shoulder arthroplasty in high risk patients (high comorbidity, obesity, underlying diagnosis of tumor, trauma or rheumatoid arthritis) may reduce this low risk of infection even further; however, this may have to be balanced against adverse events of antibiotics, which are not uncommon.

We observed some changes in microbiology of organisms leading to infection, with progression of time. Emergence of Propionibacterium acnes in later time periods was particularly noticeable and may need further surveillance in other ongoing and future studies. This may be due to one or more of the following reasons: (1) a changing pattern in offending organism for shoulder periprosthetic infection or common use of antibiotics against Staphylococcus, allowing for other organisms to be associated with periprosthetic infection; (2) recent recognition and heightened surveillance for Propionibacterium acnes as an underlying organism may have led to higher detection rates; and/or (3) longer culture incubation periods over the study period may have also influenced the rate of detection of P. acnes. With small numbers in our study, it was not possible to conclude which of these reasons were responsible for increasing diagnosis of P. acnes as the causative organism for shoulder arthroplasty infections. Future studies should be able to address this since now most laboratories test for P.acnes and long incubations are routine. Considering that majority of infections prior to 2000 were staphylococcal, where as P. acnes emerged as a common cause during 2000–2006, surgeons may consider adding prophylactic perioperative antibiotics that cover P. acnes to potentially reduce the risk of P.acnes infection.

We noted some patterns regarding the type of infection based on time since arthroplasty. More than 2/3rd of the early infections diagnosed within 6-months were staphylococcal. Forty percent of intermediate-term infections (6–24 months) were caused by staphylococcus coagulase-negative, where as the late infections (>24 months) were equally divided between Propionibacterium acnes, methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus and clostridium species. These distributions can possibly help surgeons in choosing appropriate antibiotics while microbiological diagnosis is awaited or in difficult cases, where cultures have been negative.

In the two previous studies of infection following shoulder arthroplasty from our institution, data were presented combined for all shoulder arthroplasties 2; 12. Hematoma formation was a risk factor for deep periprosthetic infection after shoulder arthroplasty 2. As our current study emphasizes only the HHRs, a separate study on the TSAs might show that hematoma is an even more significant risk in TSA than in the combined group.

An underlying diagnosis of trauma was associated with lower infection-free survival. This was a novel finding in our study. Surgeons may consider more expanded perioperative antibiotic coverage for patients with shoulder trauma undergoing arthroplasty. These patients should also be monitored more closely for early signs of infection. BMI≥30 had a non-significant trend towards an association with higher risk of deep periprosthetic infection after HHR. Morbid obesity and comorbidity were associated with higher risk of deep periprosthetic infections after knee arthroplasty 5–6; 11 and higher comorbidity with periprosthetic infection following hip arthroplasty 9. The lack of association of these factors in our study seems primarily related to a small number of infections. Studies of larger series of periprosthetic infections are needed to explore this association further.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we found an excellent 20-year infection-free survival of 99% of shoulder hemi-arthroplasty implant. Staphylococcus and Propionibacterium were the most common underling pathogens. BMI showed a non-significant trend towards significance, a finding that needs to be explored with larger sample sizes. Shoulder hemiarthroplasty is a procedure with low risk of periprosthetic infections and excellent implant survival. Despite a large number of patients in our study, we feel that even larger studies with more outcome events are needed to examine potential associations of important clinical characteristics with the risk of deep periprosthetic infections after shoulder hemiarthroplasty.

Acknowledgments

Grant support: This material is the result of work supported with National Institute of Health (NIH) Clinical Translational Science Award 1 KL2 RR024151-01 (Mayo Clinic Center for Clinical and Translational Research) and the resources and the use of facilities at the Birmingham VA Medical Center, Alabama, USA. The study sponsors had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; and, in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Oother contributors-We thank Youlonda Lochler for help in data retrieval.

Acknowledgement of funding sources: This material is the result of work supported with National Institute of Health (NIH) Clinical Translational Science Award 1 KL2 RR024151-01 (Mayo Clinic Center for Clinical and Translational Research) and the resources and the use of facilities at the Birmingham VA Medical Center, Alabama, USA.

Statement of role of funding source in publication, etc): The study sponsors had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; and, in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Financial Conflict: There are no financial conflicts related to this work.

J.A.S. has received speaker honoraria from Abbott; research and travel grants from Allergan, Takeda, Savient, Wyeth and Amgen; and consultant fees from Savient, URL pharmaceuticals and Novartis.

J.W.S. has received royalties from Aircast and Biomet, consultant fees from Tornier and owns stock in Tornier.

R.H.C. has received royalties from Smith and Nephew.

IRB Approval: This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic’s Institutional Review Board and all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

Author contributions

JAS-Study and protocol design, IRB application, review of data analysis and interpretation, manuscript preparation and revision CS-data acquisition, data analysis WH-data analysis JS-Review of study design, data analysis and interpretation, critical revision of manuscript RC-Review of study design, data analysis and interpretation, critical revision of manuscript

Disclaimer

“The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.”

IRB Approval

This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (07-00367).

Level of evidence: Level IV, Case Series, Treatment Study

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bishop JY, Flatow EL. Humeral head replacement versus total shoulder arthroplasty: clinical outcomes--a review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005 Jan-Feb;14(1 Suppl S):141S–6S. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2004.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheung EV, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Infection associated with hematoma formation after shoulder arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008 Jun;466(6):1363–7. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0226-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cofield RH, Edgerton BC. Total shoulder arthroplasty: complications and revision surgery. Instr Course Lect. 1990;39:449–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992 Jun;45(6):613–9. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dowsey MM, Choong PF. Obese diabetic patients are at substantial risk for deep infection after primary TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009 Jun;467(6):1577–81. doi: 10.1007/s11999.008.0551-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jamsen E, Varonen M, Huhtala H, Lehto MU, Lumio J, Konttinen YT, et al. Incidence of prosthetic joint infections after primary knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2010 Jan;25(1):87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mileti J, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Reimplantation of a shoulder arthroplasty after a previous infected arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004 Sep-Oct;13(5):528–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mileti J, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of postinfectious glenohumeral arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003 Apr;85-A(4):609–14. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200304000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ong KL, Kurtz SM, Lau E, Bozic KJ, Berry DJ, Parvizi J. Prosthetic joint infection risk after total hip arthroplasty in the Medicare population. J Arthroplasty. 2009 Sep;24(6 Suppl):105–9. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Radnay CS, Setter KJ, Chambers L, Levine WN, Bigliani LU, Ahmad CS. Total shoulder replacement compared with humeral head replacement for the treatment of primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007 Jul-Aug;16(4):396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2006.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samson AJ, Mercer GE, Campbell DG. Total knee replacement in the morbidly obese: a literature review. ANZ J Surg. 2010 Sep;80(9):595–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2010.05369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sperling JW, Kozak TK, Hanssen AD, Cofield RH. Infection after shoulder arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001 Jan;(382):206–16. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200101000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strickland JP, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. The results of two-stage re-implantation for infected shoulder replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008 Apr;90(4):460–5. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B4.20002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swanson AB, de Groot Swanson G, Sattel AB, Cendo RD, Hynes D, Jar-Ning W. Bipolar implant shoulder arthroplasty. Long-term results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989 Dec;(249):227–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van de Sande MA, Brand R, Rozing PM. Indications, complications, and results of shoulder arthroplasty. Scand J Rheumatol. 2006 Nov-Dec;35(6):426–34. doi: 10.1080/03009740600759720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]