Controlled interactions of cells on artificial surfaces modulate cellular functions, an essential prerequisite for tissue engineering applications.[i] In living systems, cellular orientation is provided through contact guidance of extracellular matrix proteins.[ii] Similarly, synthetically fabricated nanotopographic structures have been employed to control cell morphology, alignment, adhesion, and cytoskeleton organization.[iii] Recent developments in micro- and nanofabrication techniques including photopatterning,[iv] soft-lithography,[v] electron-beam lithography,[vi] dip-pen nanolithography,[vii] and nanoimprint lithography (NIL)[viii] enable the fabrication of surfaces that mimic the structure and length scale of native topography in two-dimensional substrates. These scaffolds control complex cellular processes including tissue organization[ix] and stem-cell differentiation[x]. NIL is a particularly promising method that can be used to pattern chemically functional materials,[xi] integrating high resolution with high throughput.[xii]

Cellular response towards synthetic functionality is important for translating substrate properties such as chemical functionality, feature size, and the topology to cells.[xiii] This transmission, however, is complicated by the non-specific adsorption of proteins, altering the cellular response towards the template.[xiv] This alteration in surface properties is likewise responsible for the rejection of implants.[xv] Therefore, prevention of non-specific adsorption of proteins coupled with adhesion of cells on surfaces is an essential goal in tissue engineering scaffolds as well as implant design.[xvi]

Recently, we have developed an effective strategy for fabricating charged and uncharged surfaces using gold nanoparticle (NP) immobilization onto cross-linked polyethyleneimine (PEI) surfaces via dithiocarbamate chemistry (DTC).[xvii] These surfaces are highly resistant to protein biofouling, providing the possibility of direct substrate-cell interactions. Moreover, the topology provided by NP-based surfaces provides enhanced cell viability and adhesion relative to planar surfaces.[xviii] These surfaces can be patterned using nanolithography, making them promising biofunctional structures for cell patterning. Herein, we report the use of NP coated PEI surfaces to provide non-toxic surfaces for cellular growth. These surfaces were then patterned via NIL to generate scaffolds that provide essentially complete control over the cellular alignment (Figure 1).

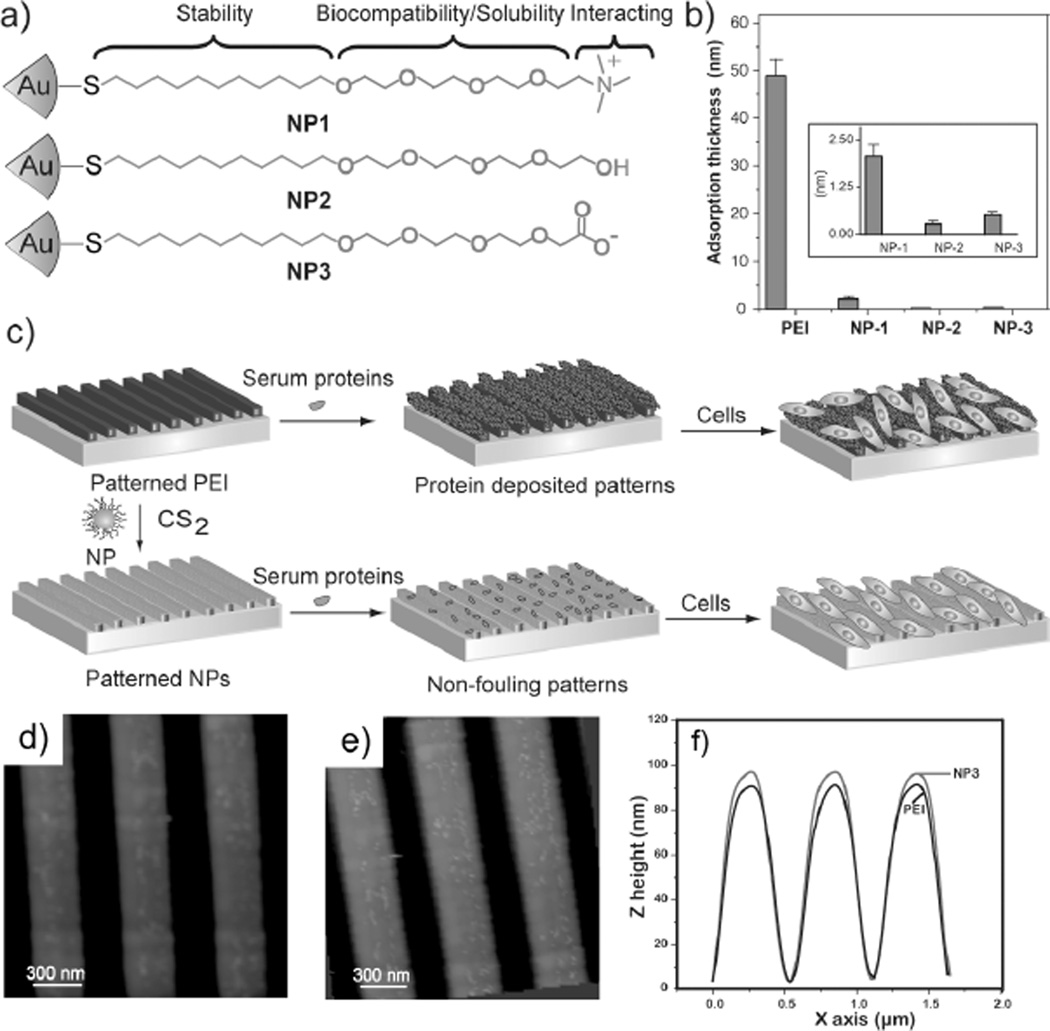

Figure 1.

a) Monolayer structures of 2 nm core diameter gold nanoparticles used in this study, b) the increase in thickness after protein adsorption onto the surfaces using ellipsometer, inset in 1b is an enlargement of Figure 1b, showing the adsorbed protein thickness onto NP-based surfaces c) patterned PEI surface for cell culture, d) AFM image of a patterned PEI surface, e) AFM image of a patterned PEI surface after NP3 immobilization, and f) change in the Z-height after immobilization of NPs onto PEI surface.

Our initial studies focused on the effect of NP charge on the viability of attached cells. We fabricated three functional gold nanoparticles (NP1-NP3) built upon a common scaffold differing only in the charge of the head groups. Positively charged NP1 possesses a quaternary ammonium head group, NP2 has a neutral hydroxyl terminus, and NP3 possesses an anionic carboxylate head group (Figure 1a).[xix] The homology of these particles[xx] allows us to directly explore the effect of the NP surface charge on cell adhesion, spreading, and viability.

The functionalized NPs were immobilized on polymer PEI surfaces using DTC as described previously.[xxi] For this purpose, a silicon surface was spin-coated with PEI polymer and was then thermally cross-linked. After the formation of the PEI film, the surfaces were immersed in a solution of carbon disulfide (CS2) and NP1-3 to generate the coated surfaces. To validate NP immobilization onto the PEI surfaces, the surfaces were characterized using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and confirmed by the relevant XPS peaks of Au 4f at 84.2 and 84.5 eV and S 2p at 162.6 eV (Figure S1). Before exploring the effect of charged and uncharged surfaces on cell viability, we investigated protein adsorption onto these surfaces in the cell culture media using ellipsometry. The NP coated surfaces showed only monolayer or sub-monolayer protein adsorptions, whereas PEI is found to be a highly protein adsorbing surface (Figure 1b).[17]

Qualitative assessment of the cell viability on these NP surfaces was obtained using mouse embryonic fibroblast cells (NIH3T3). The cells were cultured on the NP coated planar surfaces for 2 days. Fluorescent micrographs (Figure 2) were captured after co-staining the surface adhered cells with calcein AM (3µM) and propidium iodide (3µM). Cells cultured on all three NP-based surfaces showed high cell adhesion, viability, and were homogenously dispersed across the surfaces. Cells on the NP2 and NP3 surfaces were well spread and healthy, with relatively greater adhesion observed with the anionic NP3 surface (Figure S2). However, NP1-functionalized surfaces showed slightly lower cell viability than the other NPs, presumably due to the positive charge on the ammonium head group (Figure 2e).[xxii] Significantly, all of these surfaces showed higher viability than the toxic bare PEI or PEI surface exposed to carbon disulfide alone (Figure S3). Overall, these results indicate that the NP3 surface provides high viability and cell adhesion, making it an excellent candidate for cell patterning.

Figure 2.

Fluorescent micrographs of the cells stained with calcein AM (3µM) and propidium iodide (3µM) on surfaces; Cells on NPs coated surfaces (a) NP1, (b) NP2, (c) NP3, (d) PEI, and (e) Relative percentage cell viabilities of fibroblast cells on the surfaces. Scale bars: 100µm.

We next used NIL to generate biofunctional patterns[xxiii] functionalized with NP3 (Figure 1c). Patterned NP surfaces were prepared via a two-step process, as the PEI polymer was first patterned using NIL to provide templates for NP immobilization.[16] Particles were then immobilized onto the NIL templates using DTC chemistry. Based on studies by Lynn,[xxiv] we chose 300 nm patterns (Figure 1d) to achieve efficient cell directionality. In practice, the patterned surfaces were placed in a 6-well plate and mouse embryonic fibroblast cells NIH3T3 were cultured. After 2 days, cells were stained with phalloidin and Hoechst- 33342 to stain actin filaments and cell nuclei respectively (Figure 3). Figure 3a shows that the planar NP3 surface has randomly oriented cells, while Figure 3b shows a high degree of cell alignment on the NP3 patterned surfaces. In both cases, the cells possess a homogeneous spread of cytoskeleton F-actin fibers, indicating good cell adhesion to the surface. The cells on the patterned surface were elongated, spread evenly, and highly aligned in the direction of the patterns. From these studies, we can conclude that direct interaction of the surface functionality with the cells reorganizes the cellular cytoskeleton through non-specific cell surface interactions,[xxv] efficiently patterning the cells. This high degree of cellular alignment occurs due to the non-fouling nature of the surface, providing direct communication from the NP3 coated surface to the cells (Figure 3d). As a control, the highly protein-adsorbing pristine PEI pattern shows a less efficient alignment of cells due to the lack of direct communication from the patterned surface to the cells (Figure 3c), demonstrating the importance of direct cell-surface communication.

Figure 3.

Fluorescent micrographs of the cells on surfaces. a) non-patterned NP3 surface, b) patterned NP3 surface, c) patterned PEI surface, and d) cell alignments on these surfaces. Scale bars: 20µm.

In summary, we have demonstrated that charged and uncharged non-fouling nanoparticle-based surfaces support cell growth and adhesion. These surfaces provide templates for cell patterning, as demonstrated using anionic NP3-based surfaces proving most effective. The resistance of patterns based on NP3 to proteins provides a high degree of cellular alignment, demonstrating effective communication between the surface and the cells. These studies demonstrate the potential of gold nanoparticle coated surfaces for use as artificial scaffolds for tissue engineering applications. Future studies will utilize the ease of tunability and biocompatibility of gold nanoparticle-based surfaces for tissue engineering and cell-based sensor systems in both 2- and 3-dimensional applications.

Experimental

Materials and methods

Polyethyleneimine (PEI) (MW 60,000) was purchased from Aldrich and used without further purification. Epoxy resin (Araldite 502) was obtained from Polysciences, having a weight per epoxide equivalent of 233–250. The accelerator DMP-30 [2,4,6-tri(dimethylaminoethyl)phenol] was also acquired from Polysciences and used without further purification. NPs were synthesized as published previously.[19,xxvi]

Film preparation

Solutions consisting of 400 mg PEI, 10 mg of diglycidyl ether of bisphenol-A (DGEBA) and 10 mg of 2,4,6-tris(dimethylaminomethyl)phenol in 15 mL of 1:3 methanol/chloroform mixture was prepared. The solution was filtered and spin-coated at 3000rpm for 60s onto a silicon substrate, yielding a thin film of PEI (~90 nm). This film was crossslinked by heating at 100 °C for 5 h in air. A thin layer of PS for NIL was applied to the top of the PEI layer by spin coating a 10% (wt) PS in toluene solution.

Nanoimprint lithography

Nanoimprinting of the PS was performed using a Nanonex NX-2000 nanoimprinter using a patterned silicon mold. The silicon mold (line width 303 nm, period 606 nm and Groove depth 190 nm) is purchased from Lightsmyth Technologies, which was used in the cell patterning. Imprinting was performed at 150 °C and a pressure of 400 psi for 2 minutes. The residual layer from the imprinting process was etched by RIE under the following conditions: pressure 250 mTorr; inductively coupled plasma 500W; reactive ion etching 25W; oxygen 50SCCm for 90s.

Dithiocarbamate reaction

10 µL of carbon disulfide was dissolved in a solvent mixture of methanol and water (1:1 ratio). 1 mL of the above mixture was mixed with 20 µL of a 40 µM nanoparticle solution. The substrate was incubated in the solution for 3h and washed with water and methanol multiple times and finally dried under argon gas.

Media protein adsorption studies

The surfaces were incubated in media containing 10% serum overnight. The surfaces were characterized to observe the increase in thickness using an ellipsometer.

Cell culture

3T3 cells were grown in DMEM media (ATCC, 30–2002) supplemented with 10% bovine calf serum (ATCC, 30–2030) and 1% antibiotics in T75 flasks. Cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 and cells were subcultured in every three days.

Cell viability assay

Cells grown in T75 flasks were washed with DPBS buffer, trypsinized with 1X trypsin and collected in DMEM media. Cells were spun down, re-suspended in DMEM media with serum proteins/antibiotics and counted using a hemocytometer. Non patterned and patterned surfaces were placed in 6-well plates. A suspension of nearly 100,000 cells in 3 mL of media was placed in each well of a 6-well plate. Cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 for 48h. Calcein AM (Biotium Inc, 80011-2) and propidium iodide (Invitrogen) solutions were prepared in PBS buffer at a final concentration of 3 µM for both dyes and cells were incubated with the mixed dye solution for 30 minutes. Calcein AM is membrane permeant and can stain both membrane intact or membrane-compromised cells whereas propidium iodide is only permeable to dead cells/membrane-compromised cells to intercalate with cellular DNA. Fluorescence microscopy pictures were taken using Fluorescence Olympus IX51 microscope to quantify live and dead cell population. The cells were counted using ImageJ software and the cell viabilities were measured.

Cell orientation was measured from the fluorescent images using ImageJ software by determining the angle of the long axis of the nucleus with respect to the parallel direction of the pattern. In the case of non-patterned samples, orientation was measured with respect to an arbitrary direction. The cell boundaries were manually given and processed for each cell. Four images were randomly taken over the entire surface for each sample. The number of cells was counted according to their angle of alignment from 0° to 90° in 10°increments. This value is then converted into percentage cell distribution and graphed.

Cell adhesion studies

Cells grown in T75 flasks were washed with DPBS buffer, trypsinized with 1X trypsin, and collected in DMEM media. Cells were spun down, re-suspended in DMEM media with serum proteins/antibiotics and counted using a hemocytometer. Non-patterned and patterned surfaces were placed in 6-well plates. A suspension of 100,000 cells in 3 mL of media was placed in each well of 6-well plate. Cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 for 48h. After washing two times incubation period, cells were washed twice with pre-warmed PBS and fixed in a 3.7% methanol free formaldehyde solution (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Cat# 15714-S). Cells were washed three time with PBS and extracted with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 minutes. After washing two times, each surface containing cells were incubated with 1% bovine serum albumin solution for 30 minutes to reduce nonspecific background staining. Each surface was washed three times with PBS and then mixed solution of green emitting Oregon Green 488 phalloidin (Invitrogen, O7466) to stain actin filaments and blue emitting nuclear stain Hoechst stain (Invitrogen, H1399) to stain nuclei was added at a final concentrations of 200 nM and 1 µg/mL in PBS, respectively. After 30 minutes of incubation, each surface was washed three times and fluorescence images were captured.

Characterization

Bright field images and fluorescence were detected using an Olympus IX51 microscope with excitation wavelength of 470 nm and 535 nm. AFM imaging of surfaces was done on a Dimensions 3000 (Veeco) in tapping mode using a RTESP7 tip (Veeco). A Veeco Dektak Stylus profilometer was used to measure the thickness of the polymer films. Attenuated total reflectance infrared (ATR-IR) spectroscopy was used to follow the chemical functionalization. XPS studies were carried on a Physical Electronics Quantum 2000 spectrometer using a monochromatic Al Kα excitation at a spot size of 10 mm with pass energy of 46.95 eV at 15° take-off angle to probe the topmost layer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Kenneth R. Carter, from the Department of Polymer Science and Engineering, University of Massachusetts Amherst for assitance with the nanoimprinter and reactive ion etching. This research was supported by the National Institute of Health (GM077173), NSF: (CHE-0808945, VR, DGE-0504485, BC), MRSEC facilities (DMR-0820506), and the Center for Hierarchical Manufacturing (CMMI-1025020).

Footnotes

Supporting information available: XPS and cell adhesion data. This material is available online at Wiley InterScience or from the authors.

Biocompatible Structures for Cellular Patterning: Biocompatible surfaces are generated to provide protein nonfouling patterns, offering direct communication to the cells for controlling cell adhesion, and proliferation. These biofunctional surfaces provide a platform for aligning the cells in the direction of patterns, showing potential application in the field of tissue engineering. (See Figure)

References

- [i].a) Bettinger CJ, Langer R, Borenstein JT. Angew. Chem. Intl. Ed. 2009;48:5406. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wong TS, Brough B, Ho CM. Mol. Cell Biomech. 2009;6:1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Ratner BD, Bryant SJ. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2004;6:41. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.6.040803.140027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [ii].a) Ma PX. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2008;60:184. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Nichol JW, Khademhosseini A. Soft Matter. 2009;5:1312. doi: 10.1039/b814285h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [iii].a) Truskett VN, Watts MPC. Trends Biotechnol. 2006;24:312. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lawrence BD, Marchant JK, Pindrus MA, Omenetto FG, Kaplan DL. Biomaterials. 2009;30:1299. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Krebs MD, Erb RM, Yellen BB, Samanta B, Bajaj A, Rotello VM, Alsberg E. Nano Lett. 2009;9:1812. doi: 10.1021/nl803757u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Barrett DG, Yousaf MN. ChemBioChem. 2008;9:62. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Slaughter BV, Khurshid SS, Fisher OZ, Khademhosseini A, Peppas NA. Adv. Mater. 2009;21:3307. doi: 10.1002/adma.200802106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [iv].a) Scotchford CA, Ball M, Winkelmann M, Vörös J, Csucs C, Brunette DM, Danuser G, Textor M. Biomaterials. 2003;24:1147. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00488-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Bhatia SN, Yarmush ML, Toner M. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1997;34:189. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199702)34:2<189::aid-jbm8>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [v].a) Li HW, Muir BVO, Fichet G, Huck WTS. Langmuir. 2003;19:1963. [Google Scholar]; b) Pla-Roca M, Fernandez JG, Mills CA, Samitier Martinez E. Langmuir. 2007;23:8614. doi: 10.1021/la700572r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [vi].a) Rundqvist J, Mendoza B, Werbin JL, Heinz WF, Lemmon C, Romer LH, Haviland DB, Hoh JH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:59. doi: 10.1021/ja063698a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Krsko P, McCann TE, Thach TT, Laabs TL, Geller HM, Libera MR. Biomaterials. 2009;30:721. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [vii].a) Lee K, Park S, Mirkin C, Smith J, Mrksich M. Science. 2002;295:1702. doi: 10.1126/science.1067172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wilson DL, Martin R, Hong S, Cronin-Golomb M, A Mirkin C, Kaplan DL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:13660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241323198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [viii].a) Falconnet D, Pasqui D, Park S, Eckert R, Schift H, Gobrecht J, Barbucci R, Textor MA. Nano Letters. 2004;4:1909. [Google Scholar]; b) Truskett VN, Watts MPC. Trends Biotechnol. 2006;24:312. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [ix].a) Goldberg M, Langer R, Jia X. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2007;18:241. doi: 10.1163/156856207779996931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Park H, Cannizzaro C, Vunjak-Novakovic G, Langer R, Vacanti CA, Farokhzad OC. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:1867. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [x].a) Valamehr B, Jonas SJ, Polleux J, Qiao R, Guo S, Gschweng EH, Stiles B, Kam K, Luo TJ, Witte ON, Liu X, Dunn B, Wu H. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:14459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807235105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Marklein RA, Burdick JA. Adv. Mater. 2010;22:175. doi: 10.1002/adma.200901055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [xi].a) Ofir Y, Moran IW, Subramani C, Carter KR, Rotello VM. Adv. Mater. 2010;22:3608. doi: 10.1002/adma.200904396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Subramani C, Cengiz N, Saha K, Gevrek TN, Yu X, Jeong Y, Bajaj A, Sanyal A, Rotello VM. Adv. Mater. 2011;23:3165. doi: 10.1002/adma.201101292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [xii].a) Chou SY, Krauss PR, Zhang W, Guo L, Zhuang L. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B. 1997;15:2897. [Google Scholar]; b) Chou SY, Krauss PR, Renstrom PJ. Science. 1996;272:85. [Google Scholar]; c) Chou SY, Krauss PR, Renstrom PJ. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B. 1996;14:4129. [Google Scholar]

- [xiii].a) Freed LE, Engelmayr GC, Borenstein JT, Moutos FT, Guilak F. Adv. Mater. 2009;21:3410. doi: 10.1002/adma.200900303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Langer R. Adv. Mater. 2009;21:3235. doi: 10.1002/adma.200902589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Wang Y, Kim H-J, V-Novakovic G, Kaplan DL. Biomaterials. 2006;27:6064. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Tekin H, Anaya M, Brigham MD, Nauman C, Langer R, Khademhosseini A. Lab Chip. 2010;10:2411. doi: 10.1039/c004732e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [xiv].a) Allen LT, Tosetto M, Miller IS, O’Connor DP, Penney SC, Lynch I, Keenan AK, Pennington SR, Dawson KA, Gallagher WM. Biomaterials. 2006;27:3096. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Rosengren A, Pavlovic E, Oscarsson S, Krajewski A, Ravaglioli A, Piancastelli A. Biomaterials. 2002;23:1237. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00244-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [xv].a) Ratner BDJ. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1993;27:283. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820270302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Bryers JD. Colloids Surf. B. 1994;2:9. [Google Scholar]; c) Wisniewski N, Reichert M. Colloids Surf. B. 2000;18:197. doi: 10.1016/s0927-7765(99)00148-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [xvi].Grafahrend D, Heffels K-H, Beer MV, Gasteier P, Möller M, Boehm G, Dalton PD, Groll J. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011;10:67. doi: 10.1038/nmat2904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [xvii].Subramani C, Bajaj A, Miranda OR, Rotello VM. Adv. Mater. 2010;22:5420. doi: 10.1002/adma.201002851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [xviii].Jang K-J, Nam J-M. Small. 2008;4:1930. doi: 10.1002/smll.200800270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [xix].Chompoosor A, Han G, Rotello VM. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008;19:1342. doi: 10.1021/bc8000694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [xx].Moyano DF, Rotello VM. Langmuir. 2011;27:10376. doi: 10.1021/la2004535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [xxi].Subramani C, Ofir Y, Patra D, Jordan BJ, Moran IW, Park M-H, Carter KR, Rotello VM. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2009;19:2937. [Google Scholar]

- [xxii].a) Chompoosor A, Saha K, Ghosh PS, Macarthy DJ, Miranda OR, Zhu ZJ, Arcaro KF, Rotello VM. Small. 2010;6:2246. doi: 10.1002/smll.201000463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Goodman CM, Chari NS, Han G, Hong R, Ghosh P, Rotello VM. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2006;67:297. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2006.00372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Moghimi SM, Symonds P, Murray JC, Hunter AC, Debska G, Szewczyk A. Mol. Ther. 2005;11:990. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [xxiii].a) Pompe T, Zschoche S, Herold N, Salchert K, Gouzy M-F, Sperling C, Werner C. Biomacromolecules. 2003;4:1072. doi: 10.1021/bm034071c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Moon JJ, Hahn MS, Kim I, Nsiah BA, West JL. Tissue Eng. Part A. 2008;14:1. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Hahn MS, Miller JS, West JL. Adv. Mater. 2005;17:2939. [Google Scholar]; d) Yousaf MN, Houseman BT, Mrksich M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:5992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101112898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Stevens MM, Mayer M, Andersona DG, Weibel DB, Whitesides GM, Langer R. Biomaterials. 2005;26:7636. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Chen CS, Mrksich M, Huang S, Whitesides GM, Ingber DE. Science. 1997;276:1425. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5317.1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [xxiv].Fredin NJ, Broderick AH, Buck ME, Lynn DM. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10:994. doi: 10.1021/bm900045c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [xxv].Wang B, He T, Liu L, Gao C. Colloids Surf. B. 2005;46:169. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [xxvi].Bajaj A, Miranda OR, Kim I-B, Phillips RL, Jerry DJ, Bunz UHF, Rotello VM. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:10912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900975106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.