SUMMARY

Cytosolic pathogen- and damage-associated molecular patterns are sensed by pattern recognition receptors, including members of the nucleotide-binding domain and leucine-rich repeat containing gene family (NLR), which cause inflammasome assembly and caspase-1 activation to promote maturation and release of the inflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-18 and induction of pyroptosis. However, the contribution of most of the NLRs to innate immunity, host defense, inflammasome activation and their specific agonists, are still unknown. Here we describe identification and characterization of an NLRP7 inflammasome in human macrophages, which is induced in response to microbial acylated lipopeptides. Activation of NLRP7 promoted ASC-dependent caspase-1 activation, IL-1β and IL-18 maturation and restriction of intracellular bacterial replication, but not caspase-1-independent secretion of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α. Our study therefore increases our currently limited understanding of NLR activation, inflammasome assembly and maturation of IL-1β and IL-18 in human macrophages.

INTRODUCTION

Pathogen infection triggers a host defense program utilizing distinct germline-encoded pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), which collectively mount an inflammatory host response via production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and induction of pyroptosis to eliminate invading pathogens. PRRs are not limited to specifically recognizing conserved molecules on pathogens referred to as pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), but also sense host-derived damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). While engagement of some PRRs, such as TLRs and some nucleotide-binding domain and leucine-rich repeat containing gene family members (NLRs) containing a caspase recruitment domain (NLRCs) lead to a transcriptional response, activation of other NLRCs and NLRPs (NLRs containing a PYRIN domain; PYD) promote the maturation of the pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-18 in inflammasomes and the induction of pyroptosis in macrophages (Khare et al., 2010; Schroder and Tschopp, 2010). The human NLR family consists of 22 intracellular PRRs with a tripartite domain architecture featuring a C-terminal leucine rich region (LRR), a central nucleotide binding NACHT domain, and an N-terminal effector domain crucial for downstream signaling. Inflammasomes are protein scaffolds linking PAMP and DAMP recognition by PRRs to the activation of caspase-1-dependent processing and release of IL-1β and IL-18 (Martinon et al., 2002). PAMP and DAMP sensing occurs by the LRRs and results in receptor unfolding, oligomerization and PYD-mediated adaptor protein binding (Faustin et al., 2007). ASC is the essential adaptor for bridging NLRPs with caspase-1 (Srinivasula et al., 2002; Stehlik et al., 2003), and macrophages deficient in ASC are impaired in caspase-1 activation and maturation of IL-1β and IL-18 (Mariathasan et al., 2004; Yamamoto et al., 2004).

Little is known about the nature of NLRP agonists. NLRP1 recognizes muramyl-dipeptide (MDP) and B. anthraces lethal toxin (Boyden and Dietrich, 2006; Faustin et al., 2007). NLRP3 senses a variety of infectious and stress conditions by multiple mechanisms that include potassium efflux, lysosomal damage and generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Schroder and Tschopp, 2010). Although the signals that activate NLRP6 are unknown, it assembles an inflammasome to control the gut microflora (Chen et al., 2011; Elinav et al., 2011; Grenier et al., 2002). However, the physiological function of most NLRPs and their agonists is currently unknown.

Bacterial acylated (ac) lipopeptides (LP) signal through TLR2 and promote IL-1β maturation and release from macrophages and cause septic shock in mice (Aliprantis et al., 1999; Guan et al., 2010; Takeuchi et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 1997). However, the mechanism of acLP-induced IL-1β release is still elusive. In the present study we identified an NLRP7-containing inflammasome that senses microbial acLP and promotes caspase-1-dependent IL-1β and IL-18 maturation in human macrophages to restrict bacterial replication. Therefore, our study is an important contribution towards a better understanding of the pathogen-derived agonists that trigger NLR activation and inflammasome assembly in human macrophages.

RESULTS

Mycoplasma spp. (MP) Activate Macrophage Inflammasomes

MP are intracellular pathogens that cause macrophage activation (Sacht et al., 1998). We therefore tested whether MP are sensed by inflammasomes. We previously described NLRP3 agonist-induced redistribution of ASC from the nucleus to the cytosol and inflammasome formation (Bryan et al., 2009). We noticed that MP infection of human THP-1 monocytic cells (Figure 1A) and treatment of THP-1 cells (Figure 1A) and human primary macrophages (MΦ (Figure 1B) with heat killed (HK) Acholeplasma laidlawii (HKAL) also caused redistribution of ASC. Inflammasome formation was also induced by HK Gram negative Legionella pneumophilia (HKLP) and Gram positive Staphylococcus aureus (HKSA) (Figure 1A), which are sensed by NLRP3 and NLRC4 or NLRP3, respectively, and require ASC (Mariathasan et al., 2006; Vinzing et al., 2008). Subcellular fractionation also revealed nuclear and cytosolic ASC in mock-infected cells, but only cytosolic ASC in MP-infected cells (Figure 1C). To directly test MP for inflammasome activation, we treated MΦ with HKAL, which caused a significant increase in IL-1β release into culture supernatants (SN) (Figure 1D), indicating that live and HK MP are sufficient to prime MΦ and promote inflammasome activation. HKAL promoted secretion of the mature IL-1β, since total cell lysates (TCL) contained the 32 kDa precursor and the mature 17 kDa IL-1β, but only the mature IL-1β was detected in the culture SN (Figure 1E). Treatment of THP-1 cells with HKAL, HKLP and HKSA not only induced redistribution and aggregation of ASC, but also cause release of comparable IL-1β (Figure 1F). Furthermore, infection of THP-1 cells with MP promoted IL-1β release (Figure 1G). Infection was confirmed with the MycoAlert assay (Figure 1H).

Figure 1. MP causes ASC translocation form the nucleus to the cytosol and secretion of IL-1β from MΦ.

(A,B) (A) THP-1 cells were treated with culture SN from HEK293 cells either negative (Ctrl, panel 1) or positive for MP for 30 min (panel 2) or for 16 hrs (panel 3), treated with HKAL (panel 4), HKLP (panel 5) or HKSA (panel 6) for 6 hrs or (B) MΦ were either mock treated (upper panel) or treated with HKAL (lower panel) for 6 hrs and immunostained for ASC, DNA and actin. The scale bar is 20 μm.

(C) Mock and MP infected THP-1 cells were separated into nuclear (Nuc) and cytosolic (Cyt) fractions and analyzed by Western blot (WB).

(D,E) MΦ were treated with vehicle Ctrl or HKAL for 16 hrs and (D) SN were analyzed for IL-1β (n=3 ±SD) or (E) TCL and concentrated SN were analyzed by WB.

(F–H) THP-1 cells were treated with (F) vehicle Ctrl or HK bacteria for 16 hrs or (G) with Ctrl or MP positive culture SN for 24 hrs. SN were analyzed for IL-1β as above or (H) analyzed for the presence of MP (OD600 ≥ 1.0 indicates the presence of MP); n=3 ±SD; *p≤0.05.

MP and MP-Derived PAMPs Promote ASC and NLRP7-Dependent IL-1β Release

Maturation and release of IL-1β in BMDM is ASC-dependent (Mariathasan et al., 2004; Yamamoto et al., 2004). We therefore investigated, whether MP-induced IL-1β maturation also requires ASC, using THP-1 cells with stably silenced ASC (THP-1shASC), scrambled (THP-1shCtrl)) or luciferase-targeted control shRNA (THP-1shLuc) (Bryan et al., 2009; Kung et al., 2012). IL-1β release into culture SN of THP-1shASC cells treated with HKAL, HKLP or HKSA was impaired compared to THP-1shLuc cells (Figure 2A). MP-induced TLR2 activation occurs via diacylated LP, such as FSL-1 (Garcia et al., 1998; Sacht et al., 1998; Takeuchi et al., 2000). We therefore investigated the contribution of acLP to this ASC-dependent response. While treatment of THP-1shCtrl cells with HKAL, FSL-1, diacylated Pam2CSK4 and triacylated Pam3CSK4 caused IL-1β release, it was impaired in THP-1shASC cells (Figure 2B), indicating that microbial acLP are sufficient to cause ASC-dependent IL-1β release, as shown for ASC deficient BMDM (Ozoren et al., 2006).

Figure 2. ASC and NLRP7 are required for HKAL and acLP-induced IL-1β secretion.

(A,B) THP-1shLuc, THP-1shCtr and THP-1shASC cells were treated with (A) vehicle Ctrl or HK bacteria (B) vehicle Ctrl, HKAL or acLP for 16 hrs and SN were analyzed for IL-1β (n=3 ±SD). TCL were analyzed by WB.

(C–F) THP-1 cells were transfected with (C,D) pooled or (E, F) individual non-targeting siRNAs (Ctrl) and siRNAs targeting NLRPs, as indicated and treated with HKAL for 16 hrs; (C,E) mRNA expression of NLRPs was analyzed by RT-PCR and β-actin control; (D,F) SN were analyzed for IL-1β as above. n=3, ±SD (G,H) MΦ were transfected with Ctrl or NLRP-specific siRNAs, treated with HKAL or FSL-1 for 16 hrs; (G) IL-1β in SN was determined (n=3 ±SD) and (H) Silencing of NLRP expression was confirmed by RT-PCR.

(I–K) (I) THP-1 cells or (J,K) MΦ were transfected using Ctrl or NLRP7 siRNAs, mock- or acLP-treated, transfected with dA:dT or primed with ultrapure LPS for 6 hrs and infected with adenovirus (AdV) for 16 hrs, as indicated and (I,J) analyzed for IL-1β and (K) IL-18 release as above. n=3 ±SD; *p≤0.05

The requirement of ASC for MP and acLP-induced IL-1β release suggests the involvement of inflammasomes and we hypothesized that NLRs are involved in this response in addition to TLRs. To identify this NLR, we performed an RNAi screen focusing on the 14 human NLRPs, due to the ASC requirement. We tested expression of all NLRPs in resting and HKAL-treated THP-1 cells by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and confirmed expression of 11 NLRPs (NLRP1–3, 5–9, 11–13) in THP-1 cells, with no change in expression following HKAL treatment (data not shown). We then silenced NLRP expression using pooled siRNAs and silencing was achieved, as confirmed by RT-PCR and qPCR, for all NLRPs except NLRP1 and NLRP13, which we excluded from further experiments (Figure 2C,S1A and data not shown). Only siRNAs targeting NLRP7 consistently prevented HKAL-induced IL-1β release (Figure 2D). We also noticed reduced IL-1β release in cells with silenced NLRP3, although it was not as potent as NLRP7 silencing. The increased inflammasome activity observed in response to HKAL in NLRP12 silenced cells agrees with a previous report showing an inhibitory role of NLRP12 on NF-κB activation and IL-1β release in response to TLR agonists, including acLP (Williams et al., 2005). We also validated individual siRNAs targeting NLRP7. Only the two siRNAs causing efficient silencing, as determined by RT-PCR (Figure 2E) and quantitative PCR (qPCR) (Figure S1B), blocked HKAL-induced IL-1β release (Figure 2F), further suggesting that NLRP7 is required for MP-mediated IL-1β release.

Microbial acLP are Specifically Sensed by NLRP7

FSL-1 was sufficient to cause ASC-dependent IL-1β release (Figure 2B) and we therefore hypothesized that NLRP7 should also be required. We silenced NLRP7, NLRP3 and randomly chosen NLRP2 and NLRP9 as controls in MΦ, and determined HKAL or FSL-1-induced IL-1β release. Silencing of NLRP7, but not NLRP2 or NLRP9, impaired HKAL and FSL-1-induced IL-1β release in MΦ (Figure 2G). Silencing of NLRP3 affected HKAL, but not FSL-1-induced IL-1β release. NLR silencing was confirmed by RT-PCR (Figure 2H) and qPCR (Figure S1C). These results support a specific role of NLRP7 in the cytosolic MP response through FSL-1 recognition. Other acLP, such as MALP-2, Pam2CSK4 and Pam3CSK4 mediate a TLR2-mediated response similar to FSL-1 (Alexopoulou et al., 2002; Guan et al., 2010; Takeuchi et al., 2000; Takeuchi et al., 2001; Takeuchi et al., 2002). We therefore investigated, whether NLRP7 is selective for MP-derived LP. Silencing of NLRP7 prevented IL-1β release in response to MP-derived diacylated FSL-1 and MALP-2 and reduced the response to the synthetic diacylated Pam2CSK4 and triacylated Pam3CSK4, but did not impair IL-1β release induced by dsDNA (dA:dT), which is recognized by absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2) (Fernandes-Alnemri et al., 2010; Rathinam et al., 2010) and to adenovirus (AdV), which elicits an NLRP3-mediated response (Muruve et al., 2008) in THP-1 cells (Figure 2I) and MΦ (Figure 2J). Activation of inflammasomes promotes release of IL-1β and IL-18 and accordingly, silencing of NLRP7 also impaired acLP-induced IL-18 release in MΦ (Figure 2K).

NLRP7 and NLRP3 Sense Bacteria, but Only NLRP7 Senses acLP

Activation of BMDM with bacterial RNA or HK bacteria requires co-stimulation with exogenous ATP (Kanneganti et al., 2007; Mariathasan et al., 2006), but we observed that exogenous ATP is not necessary for NLRP3 inflammasome activation in MΦ. Silencing of NLRP3 in MΦ was sufficient to block IL-1β release in response to E.coli total RNA, a known NLRP3 agonist (Kanneganti et al., 2006), and NLRP3 silencing was confirmed by RT-PCR (Figure S2A). In addition, we observed that NLRP7 also sensed HKAL and acLP in the absence of exogenous ATP. We therefore tested the inflammasome response to HK Gram negative (HKLP and Porphyromonas gingivalis, HKPG) and Gram positive (HKSA and Listeria monocytogenes, HKLM) bacteria, which was NLRP3- and NLRP7-dependent in MΦ cells (Figure S2B,C). Since the NLRP3-ASC complex senses various PAMPs, we confirmed that silencing of NLRP7 did not affect NLRP3 or ASC expression in MΦ by RT-PCR (Figure 3C) and qPCR (Figure S2D). To further examine NLR specificity, we silenced NLRP3, NLRP7 and treated cells with FSL-1. We had used NLRP2 as control before and used NLRP12 due to its inhibitory effect. While both NLRP3 and NLRP7 are required for HK bacteria-induced IL-1β release, only silencing of NLRP7, but not of NLRP3 or NLRP2 impaired FSL-1-induced IL-1β release in MΦ (Figure 3D) and THP-1 cells (Figure S2E), while NLRP12 silencing enhanced FSL-1-induced IL-1β release.

Figure 3. NLRP3 and NLRP7 recognize intracellular bacteria and restrict bacterial replication.

(A–D) MΦ were transfected using Ctrl and NLRP siRNAs, mock treated or treated with HK bacteria or FSL-1 for 16 hrs, as indicated and (A,B,D) analyzed for IL-1β (n=3 ±SD, *p≤0.05) or (C) analyzed by RT-PCR.

(E–H) MΦ were transfected using Ctrl, NLRP3 or NLRP7 siRNAs and left uninfected or were infected with (E,F) S. aureus (S.a) or (G,H) L. monocytogenes (L.m) and analyzed for (E,G) IL-1β 345 min p.i. (n=3 ±SD) or (F,H) were lysed at 75 and 345 min p.i. and intracellular colony forming units (CFU) were determined. Results from a RIP representative experiment are presented as CFU/cell and the fold increase compared to control siRNA transfected cells at 75 minutes p.i. is indicated.

(I) THP-1 cells were transfected with siRNAs as indicated and kept uninfected or infected with S.a. as above. SN were analyzed at the indicated times for released LDH and presented as % cytotoxicit (n=3 ±SD; *p≤0.05); n.d.: not detectable.

NLRP3 deficient BMDM show impaired caspase-1 activation and IL-1β release in response to infection with Gram positive S. aureus and L. monocytogenes (Mariathasan et al., 2006), but L. monocytogenes is also sensed by NLRC4 and AIM2 (Wu et al., 2010). S. aureus and L. monocytogenes-induced IL-1β release was blunted in cells with silenced NLRP3 and also in cells with silenced NLRP7 (Figure 3E,G), indicating that NLRP7 is another cytosolic PRR recognizing both bacteria by sensing bacterial acLP. Consistent with impaired inflammasome activation, we observed an increase in intracellular bacteria in NLRP3 and NLRP7 silenced cells at 345 minutes post infection (Figure 3F,H). Since bacterial counts were identical at 75 minutes post infection, NLRP3 and NLRP7 silencing did not affect bacterial uptake. Thus, reminiscent of NLRP3, NLRP7 inflammasome activation contributes to the restriction of intracellular growth of S. aureus and L. monocytogenes.

Activation of inflammasomes is sometimes linked to pyroptosis and silencing of NLRP3 impaired early time points of pyroptosis (McCoy et al., 2010) of up to 2 hours post infection of THP-1 cells with S. aureus, as determined by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release and annexin V staining, but not later time points (Figure 3I and S2F). In contrast, NLRP7 silencing did not affect pyroptosis at any time point tested (Figure 3I,S2F), suggesting that NLRP7 is only involved in cytokine release.

NLRP7 is Required for acLP-Induced Caspase-1 Activation

HKAL and acLP-induced IL-1β release was caspase-1 dependent, since zYVAD-fmk, a specific cell permeable caspase-1 inhibitor completely abolished it, while the caspase-9 inhibitor zLEHD-fmk had no effect (Figure 4A,S3A). In addition, NLRP7 silencing prevented FSL-1-induced caspase-1 activation, as demonstrated by impaired processing of caspase-1 p45 into p35 (Figure 4B). Crude lipopolysaccharide (cLPS) was used as a positive control. Furthermore, NLRP7 silencing prevented release of active caspase-1 p20 into culture SN (Figure 4C), directly demonstrating that NLRP7-mediated caspase-1 activation is required for acLP-induced IL-1β release.

Figure 4. NLRP7 mediates acLP-induced IL-1β release through caspase-1 activation.

(A) MΦ were pretreated with vehicle Ctrl (DMSO), zYVAD-fmk or zLEHD-fmk for 1 hr, treated with vehicle Ctrl, HKAL or FSL-1 for 16 hrs and analyzed for IL-1β release (n=3 ±SD); *p≤0.05.

(B,C) MΦ were not transfected (none), transfected with Ctrl or NLRP7 siRNAs. (B) Mock or cycloheximide (CHX)-treated (to prevent re-synthesis of pro-caspase-1) and FSL-1 or cLPS activated as indicated or (C) FSL-1-activated for 6 hrs and (B) TCL and (C) SN were analyzed by WB.

(D,E) (D) MΦ or (E) THP-1 cells were transfected with Ctrl or NLRP7 siRNAs and activated with FSL-1 or cLPS for 16 hrs as indicated and SN were analyzed for (D) IL-6 and (E) TNFα by ELISA (n=3 ±SD). Cells were pre-treated for 1 hr with anakinra to prevent autocrine IL-1β signaling; n.d.: not detectable.

(F) MΦ (upper panel) and THP-1 cells (lower panel) were transfected as indicated, activated with FSL-1, cLPS or TNF-α for the indicated times and TCL were analyzed by WB.

NLRP7 is a Bona Fide Inflammasome Activator and Does Not Affect NF-κB

acLP, LPS and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) activate TLR and cytokine receptor-mediated NF-κB-dependent transcription of inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-6, which is sufficient for secretion. However, release of IL-1β requires in addition a caspase-1-dependent maturation step. To rule out that NLRP7 silencing had a general effect on the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, we analyzed FSL-1-induced secretion of IL-6 and TNF-α, using cLPS as control, which activates TLR2 and TLR4. To eliminate any potential autocrine IL-1β effects, we pre-treated cells with the IL-1 receptor (IL-1R) antagonist anakinra (Taxman et al., 2006). However, contrary to the release of IL-1β, NLRP7 silencing did not affect the release of IL-6 and TNF-α in MΦ (Figure 4D,S3C) and THP-1 cells (Figure 4E,S3B), indicating that NLRP7 is not involved in the transcriptional regulation of cytokines. Furthermore, NLRP7 silencing did not affect FSL-1, cLPS or TNF-α-induced IκBα phosphorylation and degradation in MΦ and THP-1 cells (Figure 4F), further ruling out NLRP7 effects on NF-κB activation.

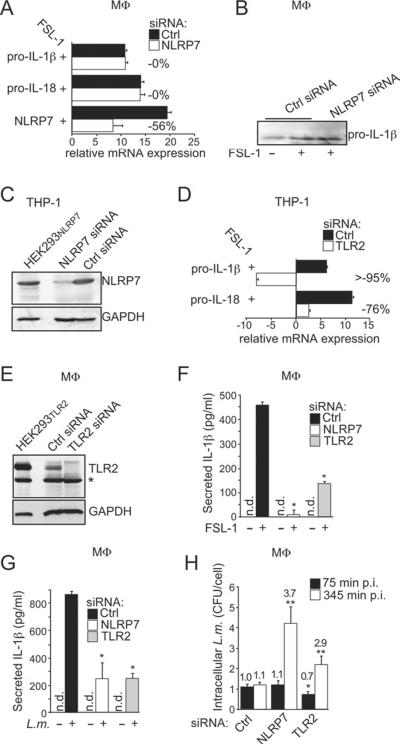

NLRP7 and TLR2 are Required for acLP-Induced IL-1β Release

FSL-1 upregulates IL-1β and IL-18 transcription through a TLR- and NF-κB-dependent mechanism. Although we achieved efficient silencing of NLRP7, this did not affect IL-1β and IL-18 transcription, as determined by qPCR (Figure 5A) and expression of pro-IL-1β in MΦ (Figure 5B), although we achieved efficient silencing of NLRP7 protein (Figure 5C). In contrast, TLR2 silencing abolished FSL-1-induced transcription of IL-1β and IL-18 (Figure 5D) and silencing was confirmed by immunoblot (Figure 5E,S4A). As expected, silencing of either TLR2 or NLRP7 prevented FSL-1-induced IL-1β release in MΦ (Figure 5F) and in THP-1 cells (Figure S4B). Since NLRP7 silencing did not affect IL-1β transcription, we conclude that NLRP7 is not involved in TLR2 signaling. Tlr2 and Asc are required for host defense against L. monocytogenes through transcription factor and caspase-1 activation, respectively (Ozoren et al., 2006). Accordingly, silencing of NLRP7 and TLR2 impaired L. monocytogenes-induced IL-1β release in MΦ (Figure 5G) and caused increased intracellular L. monocytogenes counts (Figure 5H). Since TLR2 is also required for efficient phagocytosis of L. monocytogenes (Shen et al., 2010), intracellular bacterial counts were lower upon TLR2 silencing compared to NLRP7 silencing, but TLR2 also controls L. monocytogenes infection (Torres et al., 2004). Collectively, these results demonstrate that TLR2 and NLRP7 are required for acLP-induced IL-1β release through distinct molecular mechanisms.

Figure 5. NLRP7 and TLR2 are required for acLP-induced IL-1β release.

(A) MΦ were transfected with Ctrl or NLRP7 siRNAs, activated with FSL-1 for 16 hrs and analyzed by qPCR (relative expression compared to βactin, n=3 ±SD). Silencing efficiency is indicated in % compared to control siRNA.

(B) MΦ were transfected with Ctrl or NLRP7 siRNAs, activated with FSL-1 for 16 hrs in the presence of zYVAD-fmk to prevent maturation of IL-1β and TCL were analyzed for pro-IL-1β by WB.

(C) THP-1 cells were transfected with Ctrl or NLRP7 siRNAs and analyzed by WB, using NLRP7-transfected HEK293NLRP7 cells as control.

(D) THP-1 cells were transfected with Ctrl or TLR2 siRNAs, treated with FSL-1 for 16 hrs and analyzed by qPCR for IL-1β and IL-18 mRNA, as described above. n=3 ±SD.

(E,F) MΦ were transfected with Ctrl, NLRP7 or TLR2 siRNAs, mock treated or treated with FSL-1 for 16 hrs and (E) TCL were analyzed by WB using TLR2 transfected HEK293TLR2 cells as control. *cross-reactive protein; and (F) analyzed for IL-1β release (n=3 ±SD).

(G,H) MΦ were transfected using Ctrl, NLRP7 or TLR2 siRNAs and either left uninfected or were infected with L. monocytogenes (L.m.) and (G) were analyzed for IL-1β release 345 min p.i., or (H) were lysed at 75 and 345 min p.i. and CFU were determined. Results are presented as CFU/cell and the fold increase compared to Ctrl siRNA transfected cells at 75 min p.i. is indicated (n=3 ±SD); n.d.: not detectable; *p≤0.05

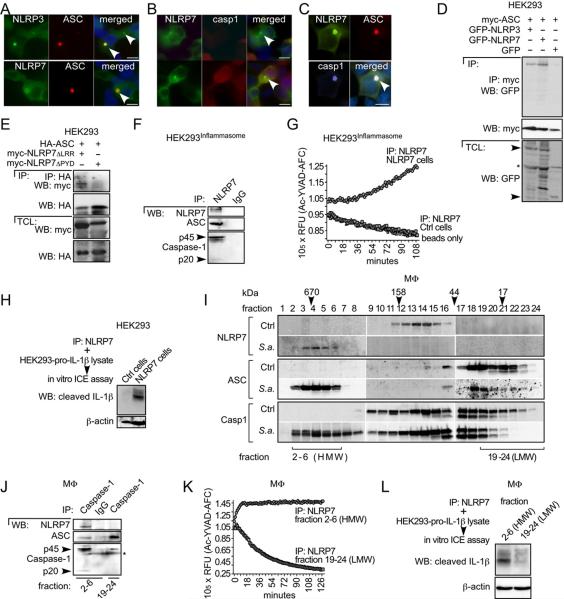

NLRP7, ASC, and Caspase-1 Assemble into a High Molecular Weight Complex in Response to Bacterial Infection

ASC, caspase-1 and NLRP7 are required for acLP-induced maturation and release of IL-1β. Therefore, we expected ASC to be recruited to NLRP7, similar to its recruitment to NLRP3. Co-expression of NLRP7 with ASC caused their co-localization in aggregates, similar to NLRP3, although additional factors might influence this interaction, since it was not as efficient as NLRP3 (Figure 6A). NLRP7 alone localized diffusely throughout the cytosol (data not shown), but aggregates appeared in cells with higher NLRP7 expression (Figure 6B). Distribution of NLRP7 was not affected in the presence or absence of caspase-1 expression (compare lower and upper panels). However, co-expression of NLRP7 with ASC and caspase-1 caused co-localization of all three proteins in aggregates (Figure 6C), suggesting that ASC is required to bridge NLRP7 to caspase-1. To demonstrate that NLRP7 and ASC physically interact, we transiently transfected GFP, GFP-NLRP7 or GFP-NLRP3 into stably ASC-expressing HEK293 cells (HEK293ASC), and immunoprecipitated ASC. ASC co-purified NLRP3 and NLRP7, but not GFP, indicating that NLRP7 can interact with ASC (Figure 6D). As predicted, the interaction required the PYD of NLRP7, since NLRP7ΔLRR, but not NLRP7ΔPYD was co-purified with ASC (Figure 6E). HEK293 cells lack endogenous inflammasome proteins, but restoring defined concentrations of pro-caspase-1, pro-IL-1β, ASC, and NLRP3 is sufficient to release IL-1β, even in the absence of agonists (Bryan et al., 2009). To demonstrate that the NLRP7 complex contains inflammasome activity, we first purified NLRP7 from stable inflammasome-reconstituted cells expressing pro-caspase-1 and ASC, transfected with NLRP7, using immobilized NLRP7 antibodies and control IgG. NLRP7 specifically co-purified ASC and caspase-1, further indicating that all three proteins existed in a complex (Figure 6F). We then subjected the purified NLRP7 protein complexes, which were isolated from these cells and from inflammasome-reconstituted cells lacking NLRP7, to an in vitro caspase-1 activity assay. Caspase-1 activity was co-purified only from cells expressing NLRP7, indicating that an active caspase-1 is present in the NLRP7 protein complex (Figure 6G). To further demonstrate that it has IL-1β converting enzyme (ICE) activity, we incubated the purified NLRP7 protein complexes with a protein lysate containing pro-IL-1β as a substrate. Only the NLRP7 protein complex purified from cells expressing NLRP7 contained ICE activity, as determined by its capability to mature pro-IL-1β (Figure 6H).

Figure 6. Activation of NLRP7 causes the formation of a high-molecular weight inflammasome in MΦ.

(A–C) Immunofluorescence staining of HEK293 cells transiently transfected with (A) ASC and NLRP3 (upper panel), ASC and NLRP7 (lower panel), (B) NLRP7 and pro-caspase-1 (upper panel shows a cell expressing only NLRP7; lower panel shows cells expressing NLRP7 and caspase-1) or (C) NLRP7, ASC and pro-caspase-1. NLR-containing aggregates are marked by arrowheads. The scale bar is 20 μm.

(D) HEK293ASC cells were transfected with GFP, GFP-NLRP3 or GFP-NLRP7 as indicated and TCL were used for IP with immobilized myc antibodies and WB as indicated.

(E) HEK293 cells were transfected with HA-ASC, myc-NLRP7ΔLRR or myc-NLRP7ΔPYD, as indicated and TCL were used for IP with immobilized HA antibodies and WB as indicated.

(F–H) Stable HEK293 inflammasome reconstituted cells (HEK293Inflammasome) were transfected with control or NLRP7 as indicated, and TCL were used for IP with immobilized NLRP7 antibodies. Immune complexes were analyzed (F) by WB as indicated; (G) equilibrated in caspase-1 assay buffer and subjected to in vitro caspase-1 activity assay or (H) for ICE activity incubated with a TCL isolated from HEK293 cells transfected with pro-IL-1β and analyzed by WB for mature IL-1β.

(I–L) Ctrl or S.a.-infected MΦ were fractionated by SEC and pooled fractions were (I) TCA precipitated and analyzed by WB as indicated; (J) Caspase-1 was immunoprecipitated from fractions 2–6 and 19–24 of S.a.-infected MΦ using IgG as control and analyzed by WB as indicated; (K,L) NLRP7 was immunoprecipitated from the same fractions and (K) assayed for caspase-1 activity assay (activity purified from fractions 2–6 saturated the assay) or (L) assayed for ICE activity as above. *cross-reactive protein.

We then investigated endogenous NLRP7 inflammasome formation by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) of TCL (Figure S5). While NLRP7 was present in fractions corresponding to its molecular weight in resting cells, it was efficiently shifted into a high molecular weight (HMW) complex following S. aureus infection of MΦ (Figure 6I). This complex was less than 1.5 MDa, since NLRP7 was not present in the void volume (1st fraction). Also ASC and caspase-1 shifted into the NLRP7-containing HMW fractions in S. aureus-infected MΦ. Caspase-1 co-purified ASC and NLRP7 from the HMW (fractions 2–6), but only co-purified ASC from the low molecular weight (LMW) (fractions 19–24) after S. aureus infection (Figure 6J). We also performed the reciprocal experiment and purified NLRP7 from both fractions and caspase-1 activity was only purified from the HMW fraction (Figure 6K), which also contained ICE activity (Figure 6L), providing biochemical support for NLRP7-containing inflammasome formation.

NLRP7, ASC, and Caspase-1 are Sufficient for the Inflammasome Response to MP and acLP

We used the inflammasome reconstitution system to dissect NLRP7 signaling. NLRP7 expression alone was not sufficient to cause IL-1β release in the presence of pro-caspase-1, but required co-expression of ASC (Figure 7A), further emphasizing the essential role of ASC in the NLRP7 inflammasome. To directly demonstrate that NLRP7 is sufficient for HKAL and FSL-1 recognition, we transfected cells with suboptimal concentrations of NLRP7, followed by a 2nd transfection to deliver HKAL and FSL-1 to the cytosol. While transfection of HKAL and FSL-1 did not promote IL-1β release in control cells, it enhanced IL-1β release in NLRP7 transfected cells (Figure 7B). Addition of HKAL or FSL-1 to the culture medium also caused inflammasome activity, albeit less than the activity obtained by cytosolic delivery of HKAL or FSL-1 (Figure S6A), since agonists need to reach the cytosol for NLR activation. To demonstrate the specificity of acLP for NLRP7, we reconstituted NLRP7 and NLRP3 inflammasomes and used Nod1, which can directly interact with caspase-1 (Yoo et al., 2002), and the inflammasome unrelated AFAP1 as controls. FSL-1 caused significantly increased IL-1β release only in reconstituted NLRP7 inflammasomes (Figure 7C). As expected, AFAP1 did not promote IL-1β It is generally believed that the LRR is required for ligand-sensing and specificity, and deletion of the LRR renders NLRP3 unresponsive in vivo (Hoffman et al., 2010). However, previous studies demonstrate that deletion of the LRR in several NLRs renders the protein hyperactive in vitro. NLRP7ΔLRR similarly displayed enhanced activity in the inflammasome reconstitution assay, but failed to respond to FSL-1 (Figure 7D). Collectively, these experiments demonstrate that NLRP7 is sufficient to promote FSL-1-induced inflammasome activation and that the LRR is necessary to sense acLP.

Figure 7. Reconstituted NLRP7 inflammasomes are sufficient to respond to HKAL and acLP.

(A)HEK293 cells were transiently transfected as indicated and release of IL-1β was determined in SN. Results are presented as fold increase compared to cells transfected with pro-IL-1β and pro-caspase-1; (n=3 ±SD); *p≤0.05 compared to cells not transfected with NLRPs.

(B) HEK293 cells were transfected as above with suboptimal concentrations of NLRP7, followed by a 2nd transfection after 24 hrs with transfection reagent alone (Ctrl), HKAL (8×105 cfu) or FSL-1 (0.5 μg). Secreted IL-1β is presented as fold increase compared to control transfected cells. (n=3 ±SD); *p≤0.05 compared to cells lacking NLRP7; **p≤0.05 compared to the 2nd round of mock-transfected cells.

(C) HEK293 cells were transfected as above with suboptimal concentrations of NLRP7, NLRP3, Nod1 or AFAP1, followed by FSL-1 transfection. Secreted IL-1β is presented as fold increase compared to Ctrl transfected cells; (n=3 ±SD); *p≤0.05 compared to cells lacking NLRs; **p≤0.05 compared to the 2nd round of mock-transfected cells. Expression of NLRP7 (118 kDa), NLRP3 (118 kDa), Nod1 (107 kDa), and AFAP1 (110 kDa) in the inflammasome reconstitution assay was verified by WB.

(D) HEK293 cells were transfected and analyzed for IL-1β secretion as above, but with NLRP7 and NLRP7ΔLRR; (n=3 ±SD); *p≤0.05 compared to the 2nd round of mock-transfected cells.

(E) HEK293 cells were transfected with NLRP7, NLRP7R693W, NLRP7R693P or NLRP7D657V, followed by FSL-1 transfection as above and secreted IL-1β is presented as fold increase compared to cells transfected with pro-IL-1β and pro-caspase-1; (n=3 ±SD); *p≤0.05 compared to cells not transfected with FSL-1; **p≤0.05 compared to cells transfected with NLRP7; ***p≤0.05 compared to cells transfected with NLRP7 and FSL-1. Expression of NLRP7 was verified by WB.

(F) MΦ were transfected using Ctrl, NLRP3 or NLRP7 siRNAs, primed with ultra pure LPS for 4 hrs and either left untreated or lysosomal damage was inflicted with Leu-Leu-OMe for 16 hrs and analyzed for IL-1β release (n=6 ±SD).

(G,H) THP-1 cells were pretreated with either medium containing 130 mM KCl (KCL) or a cathepsin B inhibitor (CA-074-Me), mock-treated or treated with MSU or (G) MSU or (H) FSL-1 for 8 hrs and secreted IL-1β was determined; (n=3 ±SD); ***p≤0.05.

We next started to investigate the mechanism of NLRP7 activation. Hereditary mutations within the NACHT-LRR region of NLRP3 cause excessive release of IL-1β through constitutive inflammasome activation. Several hereditary mutations have also been identified in NLRP7 and are linked to recurrent hydatidiform moles (HM), but a link to IL-1β or IL-18 is not known (Murdoch et al., 2006). Comparison of WT and three HM-linked NLRP7 mutations, R693W, R693P and D657V in the inflammasome reconstitution assay, provided evidence that HM-linked mutations are more potent in activating inflammasomes than NLRP7 (Figure 7E).

Direct interaction of any ligand with an NLRP has not been demonstrated, but several indirect mechanism have been proposed for NLRP3 activation, including lysosomal damage, cathepsin B release, ROS generation and K+ efflux (schroder and Tschopp, 2010). We could not detect co-localization of fluorescently labeled FSL-1 with NLRP7, nor could we co-purify biotinylated FSL-1 with NLRP7 (data not shown), suggesting an indirect mechanism of NLRP7 activation, as proposed for NLRP3. Lysosomal destabilization with the dipeptide Leu-Leu-OMe resulted in IL-1β release in MΦ which was significantly blocked upon silencing of NLRP3 and NLRP7 (Figure 7F), suggesting that both function downstream of lysosomal damage. Lysosomal rupture releases cathepsin B, which promotes NLRP3 activation in response to particulates (Hornung et al., 2008). While MSU crystal-induced NLRP3 activation was blocked in cells treated with the cathepsin B inhibitor CA-074-Me (Figure 7G), FSL-1-induced IL-1β release was only partially prevented, suggesting mechanistical differences of NLRP3 and NLRP7 activation (Figure 7H). A distinct activation mechanism is also supported by the observation that MSU-induced NLRP3 activation was impaired when cells were cultured in 130 mM KCl-containing medium (Figure 7G), which blocks K+ efflux (Petrilli et al., 2007), but FSL-1-induced IL-1β release was only slightly affected (Figure 7H). The ROS scavenger NAC and the NADPH oxidase inhibitor APDC prevent MSU-induced IL-1β release (Dostert et al., 2008), but we did not observe any effect (data not shown), which is not surprising considering NLRP7 activation is independent of K+ efflux, which is frequently linked to ROS generation.

DISCUSSION

Our study in MΦ identified the NLRP7 inflammasome, which sensed microbial infection through recognition of acLP. An earlier study failed to detect IL-1β release by immunoblot in response to the acLP Pam3Cys after only 3 hours of activation (Martinon et al., 2004). Using a more sensitive ELISA assay and increased activation time allowed us to detect acLP-induced IL-1β release, in agreement with Nlrp3-independent acLP-induced IL-1β secretion (Kanneganti et al., 2006). NLRP3 is activated by diverse stimuli, including phagocytosis of bacteria and silencing of NLRP3 or NLRP7 inhibited the response to HK and live bacteria, but only silencing of NLRP7 impaired the acLP-induced response. We propose that NLRP7 specifically recognizes bacterial acLP. Our results indicate that NLRP7 is an inflammasome activator and not a signaling component downstream of TLR2. Nevertheless, an initial extracellular acLP-induced transcriptional response through TLR2 is required for NF-κB-dependent IL-1β and IL-18 transcription (Aliprantis et al., 1999; Guan et al., 2010; Takeuchi et al., 2000). Accordingly, silencing of TLR2 impaired IL-1β transcription and release, but caspase-1 activation is not impaired in MΦ of Tlr2, Tlr4, MyD88 and Trif deficient mice, clearly separating it from TLR signaling (Kanneganti et al., 2007), and we ruled out effects on cytokine transcription. Furthermore, in our inflammasome reconstitution assay synthesis of IL-1β was TLR2 and NF-κB-independent, since HEK293 cells lack TLR2. Collectively, our results indicate that TLR2 signaling is necessary for IL-1β and IL-18 transcription, while NLRP7 is essential for IL-1β and IL-18 maturation and release in response to acLP. In contrast, a previous in vitro study suggested that NLRP7 is an inhibitor of caspase-1, based on the stable expression of a truncated NLRP7 in THP-1 cells (Kinoshita et al., 2005). A HEK293 cell overexpression study suggested that NLRP7 negatively regulates expression of co-transfected pro-IL-1β (Messaed et al., 2011a), while another study in HEK293 cells did not observe effects on IL-1β secretion (Grenier et al., 2002). In contrast, we showed that endogenous NLRP7 forms an ASC-dependent inflammasome in response to acLP in MΦ. Insufficient sensitivity may prevent detecting the NLRP7 inflammasome, since we observed that overexpressed NLRP7 is unstable and proteasomally degraded, resulting in lower expression compared to other NLRs. In addition, NLRs are spliced, resulting in altered activities. NLRP7 in our study contained 9 LRRs (118 kDa), but we also cloned a shorter transcript (NLRP7-S; 109 kDa) with 5 LRRs and reduced activity (Figure S6B).

Differences exist in the repertoire of human and mouse NLRs and Nlrp7 is lacking from mice, but nevertheless, one can expect the existence of an acLP-sensing functional NLRP7 mouse analogue. Another difference is that BMDM require exogenous ATP for IL-1β release, while MΦ release IL-1β in response to acLP alone. Future studies will need to identify the mechanism of NLRP7 activation and address if the agonist repertoire of NLRP7 is similar to that of TLR2, restricted to acLP, or if it also responds to non-TLR2 agonists. acLP are used as vaccine adjuvant and immune-activating serum acLP have been identified (Thacker et al., 2009). Thus, NLRP7-activating DAMPs might exist, similar to the ones recognized by NLRP3.

Hereditary mutations in NLRP7 are linked to HM, which predisposes women towards molar pregnancy and may develop into a choriocarcinoma, but only 60% of HM patients harbor NLRP7 mutations (Murdoch et al., 2006). It is not known, whether IL-1β or IL-18 contribute to HM (Slim and Mehio, 2007). Monocytes from some HM patients with NLRP7 mutations show reduced IL-1β secretion (Messaed et al., 2011a), while 2 out of 4 HM patients showed increased IL-1β secretion in another study (Messaed et al., 2011b), but even the general population show varying IL-1β secretion (Gattorno et al., 2007). Our preliminary results from 3 common HM mutations showed increased activity in the inflammasome reconstitution system, but future studies need to investigate the contribution of IL-1β and IL-18 to HM. In addition, a connection between latent MP infection, NLRP7 activation and chronic inflammatory disease will need to be elucidated. Inhibition of bacterial replication is independently achieved by autocrine IL-1β signaling and pyroptosis (Broz et al., 2010), but we did not observe NLRP7-mediated pyroptosis, indicating that NLRP7 acts through cytokine release to limit bacterial replication, supported by the critical role of IL-1β in the host defense against S. aureus (Bernthal et al., 2011). Thus, our finding of NLRP7 as an activator of caspase-1, which restricts intracellular bacterial replication has broad implications for understanding host defense and inflammatory and autoimmune disease, and expands our limited understanding of NLRs and their respective agonists.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials and Cell Culture

THP-1 and MF were treated with HK Acholeplasma laidlawii (HKAL), Legionella pneumophila (HKLP), Staphylococcus aureus (HKSA), Porphyromonas gingivalis (HKPG), Listeria monocytogenes (HKLM) (2×105 cfu/ml), FSL-1 (0.1 μg/ml), Pam2CSK4 (2 μg/ml), Pam3CSK4 (2 μg/ml), ultrapure LPS (10 ng/ml, Invivogen), crude E. coli LPS (cLPS, 0111:B4, 600 ng/ml, Sigma), MALP-2 (0.2 μg/ml, Imgenex), TNF-α (20 ng/ml, Biosource), Leu-Leu-OMe (1 mM; Bachem), or cells were transfected with dA:dT (2 ng/ml, Sigma) using Lipofectamine LTX+ (Invitrogen) or infected with adenovirus (AdV, serotype 5). Where indicated, cells were pre-treated for 1 hr with Anakinra (10 μg/ml, Amgen), zYVAD-fmk or zLEHD-fmk (100 μM, Calbiochem), CA-074-Me (50 μM), or with medium containing 130 mM KCl. Stable THP-1shASC, THP-1shLuc and THP-1shCtrl cells were described earlier (Bryan et al., 2009; Kung et al., 2012).

Bacterial infection

THP-1 cells were treated with culture SN from HEK293 cells that tested negative or positive for MP, as determined by morphology, DAPI staining and MP test (MycoAlert, Lonza). Control HEK293 cells were grown in the presence of Plasmocin and Plasmocure (Invivogen) to prevent MP infection. 67 hrs post transfection, cells were infected with Listeria monocytogenes (MOI=12) or Staphylococcus aureus (MOI=3) for 45 min. Extracellular bacteria were eliminated with gentamycin (50 μg/ml) for 30 min, followed by collection of culture SN for ELISA as indicated and lysed in 0.02% Triton X-100 for CFU determination.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Cells were fixed, permeabilized and immunostained as described (Bryan et al., 2009). For co-localization studies, HEK293 cells were transfected with NLRP7 or co-transfected with ASC and/or pro-caspase-1. Images were acquired by confocal laser scanning and epifluorescence microscopy on a Zeiss LSM 510 and a Nikon TE2000E2-PFS with a 100× oil objective and image deconvolution.

Subcellular fractionation

106 cells were fractionated by hypotonic lysis and centrifugation into cytosolic and nuclear fractions as previously described (Bryan et al., 2009).

Cytokine and caspase-1 measurement

Cytokine secretion was quantified from clarified culture SN by ELISA (BD Biosciences, Invitrogen) from 3×105 MΦ following treatment for 5 hrs (live bacteria) or 16 hrs (all other treatments), or 24 hrs post-transfection of 4×105 HEK293 cells. Samples were analyzed in triplicate and repeated at least 3 times, showing a representative result. TCL (3×105 MΦ) and SN (4×106 MΦ) were analyzed for caspase-1 by WB. Cycloheximide (10 μg/ml) was added to prevent re-synthesis of pro-caspase-1 when analyzing TCL. In vitro caspase-1 activity was determined by kinetic fluorescence assay using NLRP7 immune complexes isolated from 5–12×107 S. aureus-infected and size fractionated MF, or from HEK293Inflammasome cells transfected with control or NLRP7 in assay buffer (50 mM Hepes pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% Chaps, 10% sucrose, 10 mM DTT, 50 μM AcYVAD-AFC) and fluorescence was determined at 37°C at 400/505 nm. Caspase-1 proteolytic activity was determined by incubating NLRP7 complexes in assay buffer, supplemented with TCL from HEK293 cells transfected with pro-IL-1β, and analysis of mature IL-1β by WB.

Pyroptosis

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity was measured using a kit (Clontech). Cells were lysed with 1% Triton X-100 for maximal LDH release.

Inflammasome reconstitution system

HEK293 cells were transfected with expression constructs for mouse pro-IL-1β and human pro-caspase-1, ASC, and NLRs using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). A stably transfected HEK293 reconstitution system (HEK293Inflammasome) was used in some experiments. Cells were transfected a 2nd time with transfection mixture, HKAL (8×105 cfu) or FSL-1 (500 ng) using Lipofectamine 2000.

Co-immunoprecipitation

Stable myc-ASC HEK293 cells (HEK293ASC) were transfected with GFP, GFP-NLRP3, or GFP-NLRP7, adjusted to yield comparable expression. Alternatively, HEK293 cells were transfected with HA-ASC and myc-NLRP7ΔLRR or NLRP7ΔPYD, or HEK293Inflammasome cells were transfected with control or NLRP7. Cells were lysed (120 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris pH 7.4, 10% glycerol, 0.2% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitors) 36 hrs post transfection. Cleared TCL or SEC fractions were subjected to IP using immobilized antibodies as indicated for 12 hrs at 4°C, washed in lysis buffer and bound proteins were analyzed by WB using HRP-conjugated secondary native IgG-recognizing antibodies (eBioscience), ECL detection (Pierce) and image acquisition (Ultralum). TCL (10% volume) were analyzed where indicated.

Size exclusion chromatography (SEC)

TCL were prepared from 5–12×107 Ctrl and 90 min S. aureus-infected MΦ by lysis in SEC buffer (10 mM Na4P2O7, 10 mM NaF, 5 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% octylglucoside and protease inhibitors) for 5 min on ice and Dounce homogenization. TCL were cleared by centrifugation (12,000 ×g at 4°C for 10 min) and 0.45 μm filtration. SEC was performed on a 16×600 mm HiPrep Sephacryl S300HR column (GE Healthcare) in 50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl at 4°C at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. Collected fractions were either TCA precipitated for WB analysis or used to purify protein complexes.

siRNA transfection

3×105 THP-1 cells were electroporated (Invitrogen) with 60 nM single or pooled siRNA duplexes and MΦ were transfected using 120 nM siRNA (F2/virofect; Targeting Systems) and analyzed 72 hrs post transfection.

RNA isolation and RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated (Trizol, Invitrogen), DNase I digested, reverse transcribed (Superscript III, Invitrogen) and analyzed by exon-spanning RT-PCR (Table S2) or qPCR (Applied Biosystems) and displayed as relative expression compared to βactin. PCR products were sequence verified.

Statistics

A standard two-tailed t test was used for statistical analysis and values of p≤0.05 were considered significant.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS

-

▶

NLRP7 is a cytosolic pattern recognition receptor in human macrophages

-

▶

NLRP7 links microbial acylated lipopeptides to inflammasome activation

-

▶

NLRP7 recruits ASC to promote caspase-1 activation and IL-1β and IL-18 maturation

-

▶

NLRP7 restricts intracellular bacterial replication

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM071723, GM071723-S1, AI082406, AI082406-S1/S2 and AR057216 to CS). SK is an Arthritis Foundation fellow (AF161715) and LA is supported by the American Heart Association (11POST585000). This work was supported by the Northwestern University Monoclonal Antibody Facility, Flow Cytometry Facility, a Cancer Center Support Grant (CA060553) and the Skin Disease Research Center (P30AR057216). We thank Sara Kramer for isolation of PBMCs and Drs. C. Cuda and H. Perlman for help with flow cytometry.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Detailed experimental procedures are described in the supplemental information.

REFERENCES

- Alexopoulou L, Thomas V, Schnare M, Lobet Y, Anguita J, Schoen RT, Medzhitov R, Fikrig E, Flavell RA. Hyporesponsiveness to vaccination with Borrelia burgdorferi OspA in humans and in TLR1- and TLR2-deficient mice. Nat Med. 2002;8:878–884. doi: 10.1038/nm732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aliprantis AO, Yang RB, Mark MR, Suggett S, Devaux B, Radolf JD, Klimpel GR, Godowski P, Zychlinsky A. Cell activation and apoptosis by bacterial lipoproteins through toll-like receptor-2. Science. 1999;285:736–739. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5428.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernthal NM, Pribaz JR, Stavrakis AI, Billi F, Cho JS, Ramos RI, Francis KP, Iwakura Y, Miller LS. Protective role of IL-1β against post-arthroplasty Staphylococcus aureus infection. J Orthopaed Res. 2011;29:1621–1626. doi: 10.1002/jor.21414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyden ED, Dietrich WF. Nalp1b controls mouse macrophage susceptibility to anthrax lethal toxin. Nat Genet. 2006;38:240–244. doi: 10.1038/ng1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broz P, von Moltke J, Jones JW, Vance RE, Monack DM. Differential Requirement for Caspase-1 Autoproteolysis in Pathogen-Induced Cell Death and Cytokine Processing. Cell Host & Microbe. 2010;8:471–483. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan NB, Dorfleutner A, Rojanasakul Y, Stehlik C. Activation of inflammasomes requires intracellular redistribution of the apoptotic speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain. J Immunol. 2009;182:3173–3182. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen GY, Liu M, Wang F, Bertin J, Nunez G. A functional role for nlrp6 in intestinal inflammation and tumorigenesis. J Immunol. 2011;186:7187–7194. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dostert C, Petrilli V, Van Bruggen R, Steele C, Mossman BT, Tschopp J. Innate Immune Activation Through Nalp3 Inflammasome Sensing of Asbestos and Silica. Science. 2008;320:674–677. doi: 10.1126/science.1156995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elinav E, Strowig T, Kau AL, Henao-Mejia J, Thaiss CA, Booth CJ, Peaper DR, Bertin J, Eisenbarth SC, Gordon JI, et al. NLRP6 Inflammasome Regulates Colonic Microbial Ecology and Risk for Colitis. Cell. 2011;145:745–757. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faustin B, Lartigue L, Bruey JM, Luciano F, Sergienko E, Bailly-Maitre B, Volkmann N, Hanein D, Rouiller I, Reed JC. Reconstituted NALP1 inflammasome reveals two-step mechanism of caspase-1 activation. Mol Cell. 2007;25:713–724. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes-Alnemri T, Yu JW, Juliana C, Solorzano L, Kang S, Wu J, Datta P, McCormick M, Huang L, McDermott E, et al. The AIM2 inflammasome is critical for innate immunity to Francisella tularensis. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:385–393. doi: 10.1038/ni.1859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia J, Lemercier B, Roman-Roman S, Rawadi G. A Mycoplasma fermentans-derived synthetic lipopeptide induces AP-1 and NF-κB activity and cytokine secretion in macrophages via the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:34391–34398. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.51.34391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattorno M, Tassi S, Carta S, Delfino L, Ferlito F, Pelagatti MA, D'Osualdo A, Buoncompagni A, Alpigiani MG, Alessio M, et al. Pattern of interleukin-1β secretion in response to lipopolysaccharide and ATP before and after interleukin-1 blockade in patients with CIAS1 mutations. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3138–3148. doi: 10.1002/art.22842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenier JM, Wang L, Manji GA, Huang WJ, Al-Garawi A, Kelly R, Carlson A, Merriam S, Lora JM, Briskin M, et al. Functional screening of five PYPAF family members identifies PYPAF5 as a novel regulator of NF-κB and caspase-1. FEBS Lett. 2002;530:73–78. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03416-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Y, Ranoa DR, Jiang S, Mutha SK, Li X, Baudry J, Tapping RI. Human TLRs 10 and 1 share common mechanisms of innate immune sensing but not signaling. J Immunol. 2010;184:5094–5103. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman HM, Scott P, Mueller JL, Misaghi A, Stevens S, Yancopoulos GD, Murphy A, Valenzuela DM, Liu-Bryan R. Role of the leucine-rich repeat domain of cryopyrin/NALP3 in monosodium urate crystal-induced inflammation in mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:2170–2179. doi: 10.1002/art.27456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornung V, Bauernfeind F, Halle A, Samstad EO, Kono H, Rock KL, Fitzgerald KA, Latz E. Silica crystals and aluminum salts activate the NALP3 inflammasome through phagosomal destabilization. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:847–856. doi: 10.1038/ni.1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanneganti TD, Lamkanfi M, Kim YG, Chen G, Park JH, Franchi L, Vandenabeele P, Nunez G. Pannexin-1-mediated recognition of bacterial molecules activates the cryopyrin inflammasome independent of Toll-like receptor signaling. Immunity. 2007;26:433–443. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanneganti TD, Ozoren N, Body-Malapel M, Amer A, Park JH, Franchi L, Whitfield J, Barchet W, Colonna M, Vandenabeele P, et al. Bacterial RNA and small antiviral compounds activate caspase-1 through cryopyrin/Nalp3. Nature. 2006;440:232–236. doi: 10.1038/nature04517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khare S, Luc N, Dorfleutner A, Stehlik C. Inflammasomes and their activation. Crit Rev Immunol. 2010;30:463–487. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v30.i5.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita T, Wang Y, Hasegawa M, Imamura R, Suda T. PYPAF3, a PYRIN-containing APAF-1-like protein, is a feedback regulator of caspase-1-dependent interleukin-1b secretion. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:21720–21725. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410057200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung VL, Khare S, Stehlik C, Bacon EM, Hughes AJ, Hauser AR. An rhs gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa encodes a virulence protein that activates the inflammasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109285109. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariathasan S, Newton K, Monack DM, Vucic D, French DM, Lee WP, Roose-Girma M, Erickson S, Dixit VM. Differential activation of the inflammasome by caspase-1 adaptors ASC and Ipaf. Nature. 2004;430:213–218. doi: 10.1038/nature02664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariathasan S, Weiss DS, Newton K, McBride J, O'Rourke K, Roose-Girma M, Lee WP, Weinrauch Y, Monack DM, Dixit VM. Cryopyrin activates the inflammasome in response to toxins and ATP. Nature. 2006;440:228–232. doi: 10.1038/nature04515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinon F, Agostini L, Meylan E, Tschopp J. Identification of bacterial muramyl dipeptide as activator of the NALP3/cryopyrin inflammasome. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1929–1934. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J. The Inflammasome: A molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-1β. Mol Cell. 2002;10:417–426. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00599-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy AJ, Koizumi Y, Higa N, Suzuki T. Differential regulation of caspase-1 activation via NLRP3/NLRC4 inflammasomes mediated by aerolysin and type III secretion system during Aeromonas veronii infection. J Immunol. 2010;185:7077–7084. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messaed C, Akoury E, Djuric U, Zeng J, Saleh M, Gilbert L, Seoud M, Qureshi S, Slim R. NLRP7, a NOD-like receptor protein, is required for normal cytokine secretion and co-localizes with the Golgi and the microtubule organizing center. J Biol Chem. 2011a;286:43313–43323. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.306191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messaed C, Chebaro W, Di Roberto RB, Rittore C, Cheung A, Arseneau J, Schneider A, Chen MF, Bernishke K, Surti U, et al. NLRP7 in the spectrum of reproductive wastage: rare non-synonymous variants confer genetic susceptibility to recurrent reproductive wastage. J Med Genet. 2011b;48:540–548. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2011.089144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch S, Djuric U, Mazhar B, Seoud M, Khan R, Kuick R, Bagga R, Kircheisen R, Ao A, Ratti B, et al. Mutations in NALP7 cause recurrent hydatidiform moles and reproductive wastage in humans. Nat Genet. 2006;38:300–302. doi: 10.1038/ng1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muruve DA, Petrilli V, Zaiss AK, White LR, Clark SA, Ross PJ, Parks RJ, Tschopp J. The inflammasome recognizes cytosolic microbial and host DNA and triggers an innate immune response. Nature. 2008;452:103–107. doi: 10.1038/nature06664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozoren N, Masumoto J, Franchi L, Kanneganti TD, Body-Malapel M, Erturk I, Jagirdar R, Zhu L, Inohara N, Bertin J, et al. Distinct Roles of TLR2 and the adaptor ASC in IL-1β/IL-18 secretion in response to Listeria monocytogenes. J Immunol. 2006;176:4337–4342. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.4337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrilli V, Papin S, Dostert C, Mayor A, Martinon F, Tschopp J. Activation of the NALP3 inflammasome is triggered by low intracellular potassium concentration. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1583–1589. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathinam VA, Jiang Z, Waggoner SN, Sharma S, Cole LE, Waggoner L, Vanaja SK, Monks BG, Ganesan S, Latz E, et al. The AIM2 inflammasome is essential for host defense against cytosolic bacteria and DNA viruses. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:395–402. doi: 10.1038/ni.1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacht G, Marten A, Deiters U, Sussmuth R, Jung G, Wingender E, Muhlradt PF. Activation of nuclear factor-κB in macrophages by mycoplasmal lipopeptides. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:4207–4212. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199812)28:12<4207::AID-IMMU4207>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder K, Tschopp J. The Inflammasomes. Cell. 2010;140:821–832. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Kawamura I, Nomura T, Tsuchiya K, Hara H, Dewamitta SR, Sakai S, Qu H, Daim S, Yamamoto T, et al. Toll-like receptor 2- and MyD88-dependent phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Rac1 activation facilitates the phagocytosis of Listeria monocytogenes by murine macrophages. Infect Immun. 2010;78:2857–2867. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01138-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slim R, Mehio A. The genetics of hydatidiform moles: new lights on an ancient disease. Clin Genet. 2007;71:25–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2006.00697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasula SM, Poyet J-L, Razmara M, Datta P, Zhang Z, Alnemri ES. The PYRIN-CARD protein ASC is an activating adaptor for Caspase-1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21119–21122. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200179200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stehlik C, Lee SH, Dorfleutner A, Stassinopoulos A, Sagara J, Reed JC. Apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain is a regulator of procaspase-1 activation. J Immunol. 2003;171:6154–6163. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.6154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi O, Kaufmann A, Grote K, Kawai T, Hoshino K, Morr M, Muhlradt PF, Akira S. Preferentially the R-stereoisomer of the mycoplasmal lipopeptide macrophage-activating lipopeptide-2 activates immune cells through a toll-like receptor 2- and MyD88-dependent signaling pathway. J Immunol. 2000;164:554–557. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi O, Kawai T, Muhlradt PF, Morr M, Radolf JD, Zychlinsky A, Takeda K, Akira S. Discrimination of bacterial lipoproteins by Toll-like receptor 6. Int Immunol. 2001;13:933–940. doi: 10.1093/intimm/13.7.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi O, Sato S, Horiuchi T, Hoshino K, Takeda K, Dong Z, Modlin RL, Akira S. Role of Toll-like receptor 1 in mediating immune response to microbial lipoproteins. J Immunol. 2002;169:10–14. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taxman DJ, Zhang J, Champagne C, Bergstralh DT, Iocca HA, Lich JD, Ting JP. ASC mediates the induction of multiple cytokines by Porphyromonas gingivalis via caspase-1-dependent and -independent pathways. J Immunol. 2006;177:4252–4256. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.7.4252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thacker JD, Brown MA, Rest RF, Purohit M, Sassi-Gaha S, Artlett CM. 1-Peptidyl-2-arachidonoyl-3-stearoyl-sn-glyceride: an immunologically active lipopeptide from goat serum is an endogenous damage-associated molecular pattern. J Nat Prod. 2009;72:1993–1999. doi: 10.1021/np900360m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres D, Barrier M, Bihl F, Quesniaux VJ, Maillet I, Akira S, Ryffel B, Erard F. Toll-like receptor 2 is required for optimal control of Listeria monocytogenes infection. Infect Immun. 2004;72:2131–2139. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.4.2131-2139.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinzing M, Eitel J, Lippmann J, Hocke AC, Zahlten J, Slevogt H, N'Guessan P D, Gunther S, Schmeck B, Hippenstiel S, et al. NAIP and Ipaf control Legionella pneumophila replication in human cells. J Immunol. 2008;180:6808–6815. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.10.6808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KL, Lich JD, Duncan JA, Reed W, Rallabhandi P, Moore C, Kurtz S, Coffield VM, Accavitti-Loper MA, Su L, et al. The CATERPILLER protein monarch-1 is an antagonist of toll-like receptor-, tumor necrosis factor α-, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis-induced pro-inflammatory signals. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:39914–39924. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502820200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Alnemri ES. Involvement of the AIM2, NLRC4, and NLRP3 Inflammasomes in Caspase-1 Activation by Listeria monocytogenes. J Clin Immunol. 2010;30:693–702. doi: 10.1007/s10875-010-9425-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M, Yaginuma K, Tsutsui H, Sagara J, Guan X, Seki E, Yasuda K, Yamamoto M, Akira S, Nakanishi K, et al. ASC is essential for LPS-induced activation of procaspase-1 independently of TLR-associated signal adaptor molecules. Genes Cells. 2004;9:1055–1067. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2004.00789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo NJ, Park WS, Kim SY, Reed JC, Son SG, Lee JY, Lee SH. Nod1, a CARD protein, enhances pro-interleukin-1β processing through the interaction with pro-caspase-1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;299:652–658. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02714-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Peterson JW, Niesel DW, Klimpel GR. Bacterial lipoprotein and lipopolysaccharide act synergistically to induce lethal shock and proinflammatory cytokine production. J Immunol. 1997;159:4868–4878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.