Abstract

Objective

Apolipoprotein E (apoE) has been implicated as conveying increased risk for coronary artery disease (CAD). Previous studies suggest a role of apoE as a modulator of immune response and inflammatory properties. We hypothesized that the presence of apo E4 is associated with an increased inflammatory burden in subjects with CAD as compared to subjects without CAD.

Methods

ApoE genotypes, systemic (C-reactive protein [CRP], fibrinogen, serum amyloid-A [SAA]) and vascular inflammatory markers (Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 [Lp-PLA2] and pentraxin-3 [PTX-3]) were assessed in 324 Caucasians and 208 African Americans, undergoing coronary angiography.

Results

For both ethnic groups, Lp-PLA2 index, an integrated measure of Lp-PLA2 mass and activity, increased significantly and stepwise across apoE isoforms (P=0.009 and P=0.026 for African Americans and Caucasians respectively). No differences were found for other inflammatory markers tested (CRP, fibrinogen, SAA and PTX-3). For the top cardiovascular score tertile, apo E4 carriers had a significantly higher level of Lp-PLA2 index in both ethnic groups (P=0.027 and P=0.010, respectively).

Conclusion

The presence of the apo E4 isoform was associated with a higher level of Lp-PLA2 index, a marker of vascular inflammation. Our results suggest that genetic variation at the apoE locus may impact cardiovascular disease risk through enhanced vascular inflammation.

Keywords: ApoE genotype, inflammation, coronary artery disease, ethnicity

INTRODUCTION

In spite of many advances in understanding underlying mechanisms, coronary artery disease (CAD) remains a major world-wide contributor to morbidity and mortality. It is well established that genetic as well as environmental factors contribute to the disease burden. During recent years, evidence for a role of inflammation in the development of CAD has accumulated, and the atherosclerotic process shares many characteristics with chronic inflammatory diseases [1]. In view of this, interest has focused on serum markers to better assess CAD risk conveyed by an inflammatory process.

Genetic variability at the apoE locus has been shown to be associated with risk for cardiovascular disease [2-5]. Three different apoE alleles (ε2, ε3, ε4) code for three common protein isoforms (E2, E3 and E4), resulting in six different genotypes (E2/2, E3/2, E4/2, E3/3, E4/3 and E4/4) [6]. In many studies, presence of the apo ε4 allele has been positively associated with higher LDL cholesterol levels and cardiovascular risk, while the apo ε2 allele has been protective [2-4]. ApoE allele frequencies vary among different ethnic groups, with a higher apo ε4 frequency among subjects of African or Northern European descent [3-5, 7]. Beyond an association of apoE isoforms with lipid levels, it seems likely that other factors may underlie associations between apoE genotypes and cardiovascular disease as well as other diseases. One such potential modulator would be inflammatory factors, although there is at present limited information available on the relationship of inflammatory factors and genetic variability in development of cardiovascular disease.

It has been suggested that beyond serving as markers of disease state, circulating acute phase reactants such as C-reactive protein (CRP), serum amyloid-A (SAA), pentraxin-3 (PTX-3) or fibrinogen might contribute to disease pathogenesis [8, 9]. Of note, although contradictory findings have been reported regarding the relationship between apo E4 and CRP, a number of studies report a negative association [10, 11]. Beyond CRP, other inflammatory markers such as lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 (Lp-PLA2) have been shown to predict cardiovascular disease, and thereby recently assessment of Lp-PLA2 levels has been recommended as a supplemental risk assessment marker for high risk population groups [12]. So far, there is limited information on any association between Lp-PLA2 and apoE genotypes. Notably, levels of CRP and Lp-PLA2 show only a modest association, suggesting that these markers capture different modalities of the inflammatory response. To better understand the relationship between apoE and the inflammatory response, we assessed the relationship between apoE isoforms and inflammatory markers and their association with CAD across ethnicity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Subjects were recruited from a patient population scheduled for diagnostic coronary angiography at either Harlem Hospital Center in New York City or the Mary Imogene Bassett Hospital in Cooperstown, NY [4, 13]. All consecutive patients scheduled for elective coronary angiography at the 2 sites between June 1993 and April 1997 were approached. A total of 648 patients, 401 men and 247 women, ethnically self-identified as Caucasians (n=344), African-Americans (n=232), or other (n=72) were enrolled. Exclusion criteria for this study were age ≥71 years, recent acute myocardial infarction, prior balloon angioplasty or other percutaneous intervention, or the use of lipid-lowering drug therapy. In this study, plasma samples were available from 560 subjects, 336 Caucasians and 224 African-Americans. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Harlem Hospital, Bassett Healthcare, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, and University of California Davis, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Clinical and Biochemical Assessment

Fasting blood samples were drawn approximately 2 to 4 h before the catheterization procedure, and plasma samples were stored at –80°C before analysis. Concentrations of total and HDL cholesterol (Roche, Sommerville, NJ) were determined using standard enzymatic procedures. Plasma Lp(a) levels were measured by an apo(a) size insensitive sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Sigma Diagnostics, St Louis, MO). ApoE isoforms were determined at the DNA level by amplification using the polymerase chain reaction. The amplified fragments were then digested with the enzyme HhaI and separated on a polyacrylamide gel as described by Hixson and Vernier [14]. High-sensitivity CRP levels were measured using an ELISA, standardized according to the World Health Organization First International Reference Standard [15]. Fibrinogen levels were measured by the clot-rate method of Clauss [16]. Lp-PLA2 mass was assayed using a microplate-based enzyme linked immunosorbent assay, and Lp-PLA2 activity was measured with a colorimetric activity method (diaDexus, Inc., South San Francisco, CA) [13]. Lp-PLA2 index (nmol/min/ng), an integrated measure of mass and activity, expressing enzymatic properties, was calculated as activity per mass [17]. PTX-3 levels were determined by PTX-3 (human) Detection Set from Alexis Biochemicals (Axxora, LLC, Plymouth Meeting, PA). Plasma SAA levels were measured by a commercially available ELISA kit (Invitrogen, Inc., Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instruction.

Coronary Angiography

The coronary angiograms were read by 2 experienced readers blinded to patient identity, the clinical diagnosis, and laboratory results. The readers recorded the location and extent of luminal narrowing for 15 segments of the major coronary arteries [18]. A composite cardiovascular score (0-75) was calculated based on determination of presence of stenosis on a scale of 0-5 of the 15 predetermined coronary artery segments.

Statistics

Data are described as mean ± SEM or as the median and interquartile range as appropriate. Values for CRP, SAA, PTX-3 and the composite cardiovascular score were logarithmically transformed before statistical analyses. For Lp-PLA2 mass, activity and index, levels were adjusted for confounders including LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and Lp(a) due to their function as Lp-PLA2 carriers. For ApoE genotype analysis, subjects were divided into three genotype groups: E2-carriers (genotype E2/2, E3/2), E3-carriers (genotype E3/3) and E4-carriers (genotype E3/4, E4/4). Twelve Caucasian and 16 African American subjects with the apo E2/4 genotype were excluded from analysis due to the known opposite effect of E2 and E4 on lipid levels. Group means were compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA) or analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with confounders as covariates in a model and if the overall group comparison was significant, post hoc analyses were further performed for two group pairwise comparisons with the Bonferroni correction for multiple testing. Two-tailed P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Levels of systemic and vascular inflammatory markers and the composite cardiovascular score among apoE genotypes across ethnicity are shown in Table 1. As seen in the table, the Lp-PLA2 index differed significantly across apoE isoforms with the highest level for apoE4 carriers in both Caucasians and African Americans (P=0.026, P=0.009, respectively). Notably, none of the other inflammatory markers tested differed across apoE groups among Caucasians, while fibrinogen (P=0.026), and Lp-PLA2 activity (P=0.005) levels differed significantly across apoE groups among African Americans, again with higher level for apo E4 carriers. As indicated in Table 1, the composite cardiovascular score was very similar for the different apoE genotypes among Caucasians. Further, for apo E3 and apo E4 carriers, the level was similar across Caucasian and African American ethnicity. In contrast, African American apo E2 carriers had a lower cardiovascular score compared to both the corresponding Caucasian group, as well as compared to African American apo E3 and apo E4 carriers.

Table 1.

Systemic and vascular inflammation and composite cardiovascular score among apoE genotypes across ethnicity.

| Ethnicity Inflammatory marker | ApoE genotype |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apo E2 | Apo E3 | Apo E4 | P value | |

| Caucasians | N=40 | N=208 | N=76 | |

| CRP (mg/L) | 3.4 (1.4-7.0) | 2.8 (1.4-7.6) | 3.0 (1.6-9.1) | NS |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dl) | 325±11 | 323±6 | 344±11 | NS |

| Lp-PLA2 mass (ng/ml) | 312±13 | 291±5 | 294±9 | NS |

| Lp-PLA2 activity (nmol/min/ml) | 167±6 | 171±3 | 183±5 | NS |

| Lp-PLA2 index (nmol/min/ng) | 0.56±0.02 | 0.61±0.01 | 0.64±0.02 | 0.026 |

| SAA (mg/L) | 28 (15-78) | 28 (14-92) | 54 (19-110) | NS |

| PTX-3 (ng/ml) | 1.4 (1.1-1.8) | 1.7 (1.0-2.7) | 1.7 (1.0-2.7) | NS |

| Composite score | 14.9±2.3 | 16.9±1.1 | 16.8±2.0 | NS |

| African Americans | N=36 | N=83 | N=89 | |

| CRP (mg/L) | 3.7 (1.7-9.9) | 3.3 (1.7-7.2) | 5.2 (2.6-11.7) | NS |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dl) | 370±18† | 364±11† | 409±13† | 0.026 |

| Lp-PLA2 mass (ng/ml) | 239±18† | 231±7† | 232±8† | NS |

| Lp-PLA2 activity (nmol/min/ml) | 126±7† | 142±5† | 148±4*† | 0.005 |

| Lp-PLA2 index (nmol/min/ng) | 0.57±0.03 | 0.64±0.02 | 0.68±0.02* | 0.009 |

| SAA (mg/L) | 42 (10-101) | 33 (10-98) | 43 (18-104) | NS |

| PTX-3 (ng/ml) | 0.9 (0.4-1.6)† | 1.0 (0.6-1.7)† | 1.3 (0.7-2.0)† | NS |

| Composite score | 8.1±1.8† | 15.8±1.8* | 15.7±1.7* | 0.033 |

Data are expressed as means ± SEM or median (interquartile range) for non-normally distributed variables. NS, not significant. Values for CRP, SAA, PTX-3 and composite score were logarithmically transformed before inference analyses. Nontransformed values are shown. Group means were compared by ANOVA, followed by post hoc analyses for two group pairwise comparisons with the Bonferroni correction for multiple testing.

P < 0.01 compared to Apo E2 subjects

P < 0.05 compared to Caucasians. Data for PTX-3 and composite score were based on n=307 and n=312 in Caucasians, and n=204 and n=201 in African Americans, respectively.

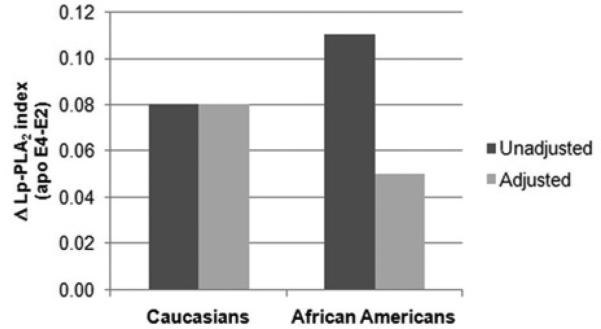

Next, we assessed the relationships of Lp-PLA2 mass, activity and index levels with apoE genotypes, adjusting for lipid confounders, including LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and Lp(a) levels (Table 2). Taking these factors into account, the differences in mean Lp-PLA2 index among apoE genotypes remained significant for Caucasians (P=0.049), while no significant differences were seen for African Americans. To further explore this finding we compared Lp-PLA2 index differences across apoE genotypes in relation to lipid levels. The relative mean difference (delta) in the Lp-PLA2 index between apo E4 and apo E2 carriers are shown in Figure 1. While the difference remained unchanged in Caucasians after adjustment for lipid levels (i.e. LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol and Lp(a) levels), the corresponding difference was substantially different with vs. without adjustment for lipid levels among African Americans. These results suggest that confounders might impact on differences in Lp-PLA2 index across apoE isoforms in the latter group.

Table 2.

Lp-PLA2 levels adjusted for lipid levels across apoE genotypes in Caucasians and African Americans.

| Ethnicity Inflammatory marker | ApoE genotype |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apo E2 | Apo E3 | Apo E4 | P value | |

| Caucasians | ||||

| Lp-PLA2 mass (ng/ml) | 315±12 | 292±5 | 297±9 | NS |

| Lp-PLA2 activity (nmol/min/ml) | 170±6 | 170±2 | 183±4 | 0.034 |

| Lp-PLA2 index (nmol/min/ng) | 0.56±0.03 | 0.61±0.01 | 0.64±0.02 | 0.049 |

| African Americans | ||||

| Lp-PLA2 mass (ng/ml) | 234±14 | 232±9 | 234±8 | NS |

| Lp-PLA2 activity (nmol/min/ml) | 136±6 | 141±4 | 146±4 | NS |

| Lp-PLA2 index (nmol/min/ng) | 0.62±0.03 | 0.63±0.02 | 0.67±0.02 | NS |

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. NS, not significant. ANCOVA were used for comparisons in mean Lp-PLA2 mass, activity and index with LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol and Lp(a) levels as covariates in a model, followed by post hoc analyses for two group pairwise comparisons with the Bonferroni correction for multiple testing.

Figure 1.

Relative mean differences (delta) in the Lp-PLA2 index between apo E4 and apo E2 carriers across Caucasians and African Americans. Comparison between unadjusted and adjusted for LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol and Lp(a) levels.

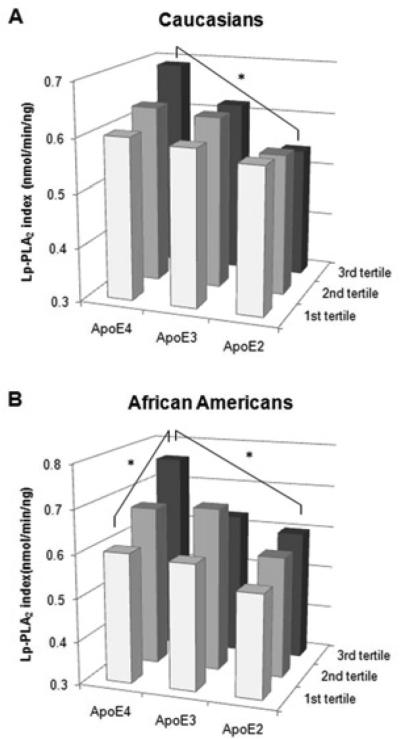

The association of the Lp-PLA2 index with the composite cardiovascular score across apoE isoforms is shown separately for each ethnic group in Figure 2, for more detail see Supplemental Table I. While there was no significant difference in the Lp-PLA2 index for any apoE genotype with increasing cardiovascular score among Caucasians (Supplemental Table I, horizontal comparison), the Lp-PLA2 index increased stepwise and differed significantly across cardiovascular score tertiles among African American apo E4 carriers with the highest Lp-PLA2 index level for the third tertile (P=0.006) (Figure 2). We next compared the Lp-PLA2 index across apoE genotypes for a given cardiovascular score tertile (Supplemental Table I, vertical comparison). While there were no significant differences in the Lp-PLA2 index among apoE genotypes for the 1st and 2nd cardiovascular score tertile, the Lp-PLA2 index differed significantly across apoE genotypes for the third cardiovascular score tertile with the highest levels for apo E4 carriers (P=0.027 and P=0.010, for Caucasians and African Americans respectively).

Figure 2.

Lp-PLA2 index levels among apoE genotypes across composite score tertiles in Caucasians and African Americans. * P < 0.05 across apoE genotypes and across composite score tertiles within each ethnic group.

DISCUSSION

Many studies have demonstrated that genetic variation at the apoE locus has a strong impact on cardiovascular disease, and that the frequency of apoE alleles varies considerably across geographical areas and ethnic groups [3-5, 7]. While we did not detect any significant differences across apoE genotypes for many of the markers tested, in the present study, we report that Lp-PLA2 index, an integrated measure of Lp-PLA2 mass and activity, differed across apoE genotypes with the highest levels for apo E4 carriers in both ethnic groups. This finding adds to a growing constellation of potentially adverse metabolic and inflammatory factors present among apo E4 carriers across ethnicity. In addition, the results further underscore the importance of Lp-PLA2 in assessing cardiovascular disease risk and suggest that apo E4 carriers may be exposed to a higher degree of vascular inflammation which potentially could accelerate development of cardiovascular disease.

The recent focus on a role of inflammation as well as genetic variation in the development of cardiovascular disease raises the issue to what extent genetic factors may modulate an inflammatory response. Although genetic variation of the apoE gene is shown to be a significant determinant of variation in total and LDL cholesterol levels, a role of apoE in disease conditions beyond the cardiovascular system is still unclear. Apo E4 has been associated with an increase in inflammatory cytokines in the central nervous system inflammatory response and in patients undergoing cardiopulmonary artery bypass [19-21]. Another role of apoE may be modulation of an immunological response through development of lipid antigens, delivered by apolipoproteins to achieve T-cell activation [22]. On the other hand, it has been suggested that presence of apo E4 may have provided advantages with regard to infectious diseases, such as an increased host resistance [23, 24]. Collectively, apo E4 has been implicated as having an immunomodulatory role, producing an altered balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines [25].

The main finding in our study was the association between apoE genotypes and the Lp-PLA2 index, where apo E4 carriers had a higher index. The ability of Lp-PLA2, a marker of a vascular inflammation, to predict cardiovascular disease has been shown in multiple studies [12, 13, 26]. Lp-PLA2 is at the crossroads of lipid metabolism and the inflammatory response as it is produced by inflammatory cells and circulates bound to LDL and other lipoproteins [27]. We and others have used Lp-PLA2 index as an integrated measure of mass and activity, and we recently demonstrated a significant association of this index with cardiovascular disease [13, 17]. Our present finding reinforces this focus on Lp-PLA2 index and contributes to the concept of apo E4 as pro-inflammatory. The relative difference in the Lp-PLA2 index between apo E4 and apo E2 carriers remained unchanged in Caucasians after adjustment for lipid levels (i.e. LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol and Lp(a) levels) while the corresponding difference became substantially lower after adjustment among African Americans. This suggests that the relative distribution of Lp-PLA2 across lipoprotein classes might differ between African Americans and Caucasians, in agreement with observations in our previous study [28]. Further, our finding of a significant increase in the Lp-PLA2 index across apoE genotypes in subjects with the highest composite cardiovascular score tertile underscores the notion that a combination of genetic, metabolic and inflammatory risk factors may promote an accelerated disease development. Notably, a recent mechanistic study in mice provided evidence of apoE serving as a control switch between lipid and inflammatory risk in the progression of atherosclerosis [29]. To the best of our knowledge, our study is one of the first exploring this connection in humans.

We acknowledge some of the limitations of this cross-sectional study. Subjects in our study were recruited from patients scheduled for coronary angiography and are likely more typical of a high-risk patient group than the healthy general population at large. Furthermore, we defined and assessed CAD on the basis of the presence of stenotic lesions. For some genotypes, the number of subjects was relatively small. As the apo E4 genotype has been associated with CAD, a potential source of bias might be a differing distribution of apoE genotypes among our subjects compared with the population at large. Arguing against this possibility, the apoE allele frequency pattern was similar to that described previously for African-American and Caucasian populations [3, 4, 7]. We acknowledge that there is limited experience in use of the Lp-PLA2 index, however it reflects two Lp-PLA2 properties - mass and activity. Although our findings support the notion of vascular inflammation as contributory to CAD risk, additional studies are needed to verify these results in other populations.

In conclusion, this is one of the first studies to demonstrate an association between apoE genotype and Lp-PLA2, an emerging marker of vascular inflammation. The Lp-PLA2 index, an integrated measure of Lp-PLA2 mass and activity was higher in apo E4 carriers irrespective of ethnicity. The findings underscore the importance of assessing the relationship between genetic predisposition and phenotypic characteristics, such as presence of inflammation, in the assessment of cardiovascular disease risk.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Apolipoprotein E (apoE) has been implicated as conveying increased risk for coronary artery disease (CAD). We hypothesized that the presence of apo E4 is associated with an increased inflammatory burden in subjects with CAD as compared to subjects without CAD. The presence of the apo E4 isoform was associated with a higher level of Lp-PLA2 index, a marker of vascular inflammation. Our results suggest that genetic variation at the apoE locus may impact cardiovascular disease risk through enhanced vascular inflammation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research project was supported by grant HL 62705 (PI: L Berglund) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and by the UC Davis Clinical and Translational Research Center (RR024146). Dr Anuurad is a recipient of an UC Davis Clinical and Translational Science Center K12 Award (RR024144). We thank diaDexus, Inc. for assistance with Lp-PLA2 measurements.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ross R. Atherosclerosis-an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:115–126. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eichner JE, Dunn ST, Perveen G, et al. Apolipoprotein E polymorphism and cardiovascular disease: a HuGE review. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:487–495. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.6.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerdes LU, Gerdes C, Kervinen K, et al. The apolipoprotein epsilon4 allele determines prognosis and the effect on prognosis of simvastatin in survivors of myocardial infarction : a substudy of the Scandinavian simvastatin survival study. Circulation. 2000;101:1366–1371. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.12.1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anuurad E, Rubin J, Lu G, et al. Protective effect of apolipoprotein E2 on coronary artery disease in African Americans is mediated through lipoprotein cholesterol. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:2475–2481. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600288-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howard BV, Gidding SS, Liu K. Association of apolipoprotein E phenotype with plasma lipoproteins in African-American and white young adults. The CARDIA Study. Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148:859–868. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahley RW, Rall SC., Jr. Apolipoprotein E: far more than a lipid transport protein. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2000;1:507–537. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.1.1.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eggertsen G, Tegelman R, Ericsson S, et al. Apolipoprotein E polymorphism in a healthy Swedish population: variation of allele frequency with age and relation to serum lipid concentrations. Clin Chem. 1993;39:2125–2129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pearson TA, Mensah GA, Alexander RW, et al. Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: application to clinical and public health practice: A statement for healthcare professionals from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2003;107:499–511. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000052939.59093.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Latini R, Maggioni AP, Peri G, et al. Prognostic significance of the long pentraxin PTX3 in acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2004;110:2349–2354. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000145167.30987.2E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eiriksdottir G, Aspelund T, Bjarnadottir K, et al. Apolipoprotein E genotype and statins affect CRP levels through independent and different mechanisms: AGES-Reykjavik Study. Atherosclerosis. 2006;186:222–224. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grammer TB, Hoffmann MM, Renner W, et al. Apolipoprotein E genotypes, circulating C-reactive protein and angiographic coronary artery disease: The Ludwigshafen Risk and Cardiovascular Health Study. Atherosclerosis. 2011;215:487–493. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davidson MH, Corson MA, Alberts MJ, et al. Consensus panel recommendation for incorporating lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 testing into cardiovascular disease risk assessment guidelines. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:51F–57F. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anuurad E, Ozturk Z, Enkhmaa B, et al. Association of lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 with coronary artery disease in African-Americans and Caucasians. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:2376–2383. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hixson JE, Vernier DT. Restriction isotyping of human apolipoprotein E by gene amplification and cleavage with HhaI. J Lipid Res. 1990;31:545–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macy EM, Hayes TE, Tracy RP. Variability in the measurement of C-reactive protein in healthy subjects: implications for reference intervals and epidemiological applications. Clin Chem. 1997;43:52–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clauss A. [Rapid physiological coagulation method in determination of fibrinogen.]. Acta Haematol. 1957;17:237–246. doi: 10.1159/000205234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saougos VG, Tambaki AP, Kalogirou M, et al. Differential effect of hypolipidemic drugs on lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2236–2243. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.147280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller M, Mead LA, Kwiterovich PO, Jr., et al. Dyslipidemias with desirable plasma total cholesterol levels and angiographically demonstrated coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1990;65:1–5. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)90017-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lynch JR, Tang W, Wang H, et al. APOE genotype and an ApoE-mimetic peptide modify the systemic and central nervous system inflammatory response. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:48529–48533. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306923200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drabe N, Zund G, Grunenfelder J, et al. Genetic predisposition in patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass surgery is associated with an increase of inflammatory cytokines. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2001;20:609–613. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(01)00842-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahley RW, Nathan BP, Pitas RE. Apolipoprotein E. Structure, function, and possible roles in Alzheimer's disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1996;777:139–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb34412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van den Elzen P, Garg S, Leon L, et al. Apolipoprotein-mediated pathways of lipid antigen presentation. Nature. 2005;437:906–910. doi: 10.1038/nature04001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuhlmann I, Minihane AM, Huebbe P, et al. Apolipoprotein E genotype and hepatitis C, HIV and herpes simplex disease risk: a literature review. Lipids Health Dis. 2010;9:8. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-9-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finch CE, Morgan TE. Systemic inflammation, infection, ApoE alleles, and Alzheimer disease: a position paper. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2007;4:185–189. doi: 10.2174/156720507780362254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jofre-Monseny L, Minihane AM, Rimbach G. Impact of apoE genotype on oxidative stress, inflammation and disease risk. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2008;52:131–145. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ballantyne CM, Hoogeveen RC, Bang H, et al. Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, and risk for incident coronary heart disease in middle-aged men and women in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Circulation. 2004;109:837–842. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000116763.91992.F1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Epps KC, Wilensky RL. Lp-PLA- a novel risk factor for high-risk coronary and carotid artery disease. J Intern Med. 2011;269:94–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Enkhmaa B, Anuurad E, Zhang W, et al. Association of Lp-PLA(2) activity with allele-specific Lp(a) levels in a bi-ethnic population. Atherosclerosis. 2010;211:526–530. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murphy AJ, Akhtari M, Tolani S, et al. ApoE regulates hematopoietic stem cell proliferation, monocytosis, and monocyte accumulation in atherosclerotic lesions in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011 doi: 10.1172/JCI57559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.