Abstract

Objective

There is a bidirectional association between depression and cardiovascular disease. The neurobiological mechanisms underlying this association may involve an inability to cope with disrupted social bonds. This study investigated in an animal model the integration of depressive behaviors and cardiac dysfunction following a disrupted social bond and during an operational measure of depression, relative to the protective effects of intact social bonds.

Methods

Depressive behaviors in the forced swim test and continuous electrocardiographic parameters were measured in 14 adult, female socially monogamous prairie voles (rodents), following 4 weeks of social pairing or isolation.

Results

Following social isolation, animals exhibited (all values are mean ± standard error of the mean, isolated vs. paired respectively) increased heart rate (416±14bpm vs. 370±14bpm, P<0.05) and reduced heart rate variability [3.3±0.2ln(ms2) vs. 3.9±0.2ln(ms2)]. During the forced swim test, isolated animals exhibited greater helpless behavior (immobility, 106±11sec vs. 63±11sec, P<0.05), increased heart rate (530±22bpm vs. 447±15bpm, P<0.05), reduced heart rate variability [1.8±0.4ln(ms2) vs. 2.7±0.2ln(ms2), P<0.05), and increased arrhythmias (arrhythmic burden score, 181±46 vs. 28±12, P<0.05).

Conclusions

The display of depressive behaviors during an operational measure of depression is coupled with increased heart rate, reduced heart rate variability, and increased arrhythmias, indicative of dysfunctional behavioral and physiological stress-coping abilities as a function of social isolation. In contrast, social pairing with a sibling is behaviorally- and cardioprotective. The present results can provide insight into a possible social mechanism underlying the association of depression and cardiovascular disease in humans.

Keywords: Autonomic nervous system, Forced swim test, Heart rate variability, Helplessness, Isolation, Prairie vole

INTRODUCTION

A significant bidirectional relationship between depressive disorders and cardiovascular disease has been observed in humans. For instance, the presence of depression is associated with increased incidence of and mortality from cardiovascular disease, and the presence of cardiovascular disease is associated with an increased incidence of depression (1–6). Research reviewed in detail (6–9) has focused on a number of biopsychosocial mechanisms that may underlie this association, including autonomic dysfunction, dysregulated stress coping, immune system disturbances, and central neurotransmitter dysregulation.

Increased attention has been devoted to understanding the interactions of the social environment with other mechanisms that influence the relationship between negative mood and cardiovascular dysfunction. Individuals who are socially isolated or lack appropriate social integration show an increased risk of both depression and cardiovascular disease; and conversely, social support can be protective against these behavioral and physiological disorders (10–15). For instance, increased depressive symptomatology has been observed in individuals with smaller social networks, versus those with larger networks (16). Social isolation and lack of social connections (e.g., being single or unmarried, having fewer social interactions with friends or family, being less involved in community organizations, and/or perceiving lower levels of social support) are associated with several cardiovascular risk factors and increased cardiovascular mortality (16–23). Further, high perceived social support buffers the relationship between depression and mortality in patients following myocardial infarction (24).

In the context of understanding the neurobiological mechanisms of depression and cardiovascular disease, research with valid and reliable animal models can offer important insights. Previous research with the socially monogamous prairie vole has addressed the translational relevance of studying behavioral, neural, and physiological consequences of social stressors and the beneficial effects of positive social relationships (9,25,26). The prairie vole is a useful model for investigating social and neural mechanisms underlying depression and cardiovascular disease for several reasons. This species is one of very few rodents with a reliance on the surrounding social context similar to humans, displaying long-term social bonds, bi-parental care, and cooperative living (27–29). Therefore, this species can serve as a beneficial model for studying both the consequences of negative social experiences and the potential protective effects of social affiliation. Also, the prairie vole exhibits high levels of parasympathetic input to the heart with comparatively less regulation from the sympathetic nervous system, similar to humans and larger mammals, allowing for translational investigations of physiological changes associated with the autonomic nervous system (30).

Further, prairie voles are highly sensitive to the disruption of social bonds, exhibiting several examples of altered behavior, cardiovascular dysregulation, and disruptions in neuroendocrine and autonomic responses to stressors. Both short- and long-term social isolation in prairie voles result in behavioral changes in validated measures of depression and anxiety (31–34). For example, we have previously demonstrated that 4 weeks of social isolation in this species produces depressive behaviors, including anhedonia (reduced reward-seeking behavior) and learned helplessness (reduced active coping strategies during an acute stressor), relative to social pairing with a sibling which is protective against these behavioral consequences (31,32,34). This same period of social isolation also produces several cardiac and autonomic disturbances that mirror those observed in cardiovascular disease, including: (a) an increase in resting and 24-hour heart rate (HR), (b) a decrease in resting and 24-hour HR variability, (c) exaggerated cardiac reactivity to acute stressors, and (d) autonomic imbalance; whereas social pairing is protective against all of these cardiovascular and autonomic disturbances (32,35,36). Related to these behavioral and cardiovascular disruptions, 4 weeks of social isolation in female prairie voles (versus social pairing) is associated with widespread neuroendocrine dysregulation, including: (a) increased basal levels of oxytocin in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus and in the systemic circulation, (b) increased activation of oxytocin and corticotropin-releasing hormone neurons in the paraventricular nucleus following a brief social stressor, and (c) increased circulating stress hormones (oxytocin, adrenocorticotropic hormone, corticosterone) following a brief social stressor (34). Taken together, these findings from the prairie vole model provide evidence that appropriate social bonds are protective against depressive behaviors, cardiac and autonomic dysregulation, and neuroendocrine disruptions.

While an increasing body of literature suggests that the disruption of social bonds in prairie voles produces altered behaviors, cardiac function, and neuroendocrine and autonomic dysregulation, research is limited on the integration of depressive behaviors and cardiac pathophysiology. A greater understanding of this integration can provide novel insight into the mechanisms by which negative social experiences influence depression and cardiovascular disease. A common test of depressive behaviors used in rodents - including prairie voles - is the forced swim test (FST), which involves exposing an animal to one or more brief periods of swimming in an inescapable task (31,33,37,38). The animal is evaluated for evidence of active coping behaviors, such as struggling and swimming, versus a passive response of immobility. This test is argued to possess a high degree of validity for operationally defining the behavioral state of depression (i.e., behavioral despair or helplessness) (37,39–41). Previous research with the FST has focused on the ability of pharmacological agents such as antidepressants to increase an animal’s active coping strategies and reduce helpless behaviors (37,40). Additional research suggests that this paradigm is a potent psychological stressor (41,42). However, available evidence on the precise interactions of behaviors and physiological responses during the FST is not clear. For example, exposure to the FST in rats leads to an increase in HR (relative to pre-swim values), but there is no association between helpless behaviors and circulating stress hormones (either adrenocorticotropic hormone or corticosterone levels) (43).

The interpretation of behaviors during the FST will be strengthened with a detailed view of the autonomic state of the animal. Further, understanding the effects of positive and negative social experiences on behaviors and autonomic function during the FST will offer novel insight into the mechanisms underlying depression and cardiovascular disease, and will provide a foundation for further mechanistic studies focused on depressive behaviors and cardiovascular regulation. Given these considerations, the current study was designed to reach two related goals. First, to extend previous findings from this animal model (31,32), we tested the hypothesis that 4 weeks of social isolation in female prairie voles would lead to disruptive stress-coping strategies in the FST consistent with a depressive behavior, along with cardiac rate and rhythm disturbances consistent with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease. Second, we tested the hypothesis that depressive behaviors would be directly related to cardiac rate and rhythm disturbances during the FST. We predicted that greater helplessness during a period of forced swimming would be associated with increased cardiac disturbances, providing direct evidence that the altered behaviors displayed during this task are a function of a psychological stress response.

METHODS

Animals

Fourteen adult female prairie voles, descendants of a wild stock caught near Champaign, Illinois, were used. Animals had a mean (± standard error of the mean; SEM) age of 81±5 days, and a body weight of 35±1 grams. All animals were maintained on a 14/10 h light/dark cycle (lights on at 0630h), with a mean ± SEM ambient temperature of 25±2°C and relative humidity of 30±5%. Animals were allowed food (Purina rabbit chow) and water ad libitum. Offspring were removed from breeding pairs at 21 days of age and housed in same-sex sibling pairs. For all procedures described herein, only one animal from each sibling pair was studied. All procedures were conducted according to the National Institutes of Health’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the local university Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees.

Females were used here for several reasons. First, female rodents are an understudied group both in behavioral and physiological investigations of mood and cardiovascular disorders (see 44). Second, female prairie voles (45,46) and humans (47) may be especially sensitive to the effects of social stressors. Finally, female prairie voles do not show a spontaneous puberty or estrous cycle; the ovaries remain inactive until the female has physical contact with a male, allowing for the use of reproductively intact animals without the need for controlling the estrous cycle (48).

Telemetric Transmitter Implantation

Wireless radiofrequency transmitters [Data Sciences International (DSI), St. Paul, MN; model TA10ETA-F20] were implanted intraperitoneally for continuous ECG and activity recordings, under aseptic conditions during the light period, using procedures described previously (49). Care was taken to ensure that animals did not experience unnecessary pain or distress during the procedures. Briefly, animals were anesthetized (ketamine 67mg/kg, sc; xylazine 13.33mg/kg, sc; NLS Animal Health, Owings Mills, MD), and the transmitter was inserted into the abdominal cavity. The leads were directed rostrally and anchored in place on either side of the heart with permanent sutures. All skin incisions were sutured closed, and subcutaneous sterile saline was administered as necessary.

Following the surgical procedures, all animals were monitored carefully for potential adverse responses to the implantation of the transmitter using both visual inspection and radiotelemetry data generated from the transmitter. Animals were housed for 5 days in custom-designed cages (see 30) which allowed the instrumented animal to interact with its sibling through a divider, but also permitted adequate healing of suture wounds in the instrumented animal. All animals were given ad libitum access to food, water, and 2% sucrose for this 5-day period, along with access to a heat lamp for the first 2 days following surgical procedures. Previous studies (30,32) involving surgical implantation of these transmitters in prairie voles have demonstrated that this period is necessary to facilitate adequate healing of suture wounds, but it does not significantly affect the animal’s ability to re-establish social bonds with its respective sibling. Following 5 days of recovery in divided cages, each animal was returned to the standard home cage (with its sibling) for an additional 7–10 days before the onset of experimentation.

Radiotelemetric Recordings

ECG signals were recorded continuously throughout the experimental procedures with a radiotelemetry receiver (DSI; sampling rate 5kHz, 12-bit precision digitizing, Dataquest ART, Version 4.1 Acquisition software). Activity level (sampling rate 256Hz) and body temperature (sampling rate 1kHz) were monitored via the receiver.

Social Isolation

Following recovery from the surgical procedures, prairie voles were randomly divided into two independent groups of either continuous pairing (social support condition; n = 7) or isolation (n = 7). Isolated animals were separated from their respective siblings and housed individually (in a separate room, without visual or olfactory cues) for 4 weeks, while paired animals were continually housed with the siblings during this period. This time period was chosen to be consistent with previous studies showing that 4 weeks of social isolation in female prairie voles disrupts affective behaviors, (31,34), cardiac function (32), and neuroendocrine and autonomic function (32,34). Handling and cage changing were matched between the two groups. Body weight was recorded prior to isolation, and following 2 and 4 weeks of this period.

ECG and activity level were recorded continuously throughout the isolation/pairing period and analyzed as specified below.

Forced Swim Test

Investigation of swimming behavior in the FST was used as an index of a depressive phenotype. Following the 4-week period of isolation or pairing, all animals were exposed to a 5-minute period of forced swimming during the light period, using a modification of procedures described elsewhere (31,37). A clear, cylindrical Plexiglas tank (height 46cm; diameter 20cm) was filled to a depth of 18cm with warm tap water (35–37°C). The temperature of the water was modified from room temperature, as previously described (37), to ensure accurate ECG measurements that were not confounded by a drop in core body temperature. Animals were placed individually into the tank for 5 minutes. The tank was cleaned thoroughly and filled with clean warm water prior to testing each animal. Each animal was returned to its home cage immediately following the swim period, and was given a heat lamp for 15 minutes.

Behaviors during the swim test were recorded using a digital video camera, and defined as the following: (a) swimming, movements of the forelimbs and hindlimbs without breaking the surface of the water; (b) struggling, forelimbs breaking the surface of water; (c) climbing, attempts to climb the walls of the tank; and (d) immobility, no limb or body movements (floating) or using limbs solely to remain afloat without corresponding trunk movements. Struggling, climbing and swimming were summed to provide one index of active coping behaviors; immobility was used as the operational index of depressive behavior, according to previous tests of validity and reliability (31,37).

ECG, activity level, and body temperature were recorded continuously throughout the 5-minute swim period and analyzed as specified below.

Data Quantification

Processing of Telemetric Variables

ECG, activity, and body temperature signals were recorded with a radiotelemetry receiver (DSI) and quantified using the vendor software (Dataquest ART Acquisition software version 4.1) according to methods described previously (30). Briefly, multiple segments of 1–5 minutes of stable, continuous data were used to evaluate HR, HR variability, arrhythmic events, activity, and body temperature following isolation and during the FST.

All R-R intervals were manually inspected using custom-designed software [Brain-Body Center, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL (50,51)], and were used to calculate the following variables: (a) HR, (b) standard deviation of all R-R (normal-to-normal; N-N) intervals [SDNN Index (52)], (c) respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) amplitude (30,53), (d) ventricular arrhythmic events, and (e) supraventricular arrhythmic events. All segments of ECG data that included artifact from animal movement were excluded from analyses of HR, SDNN index, RSA amplitude, and arrhythmias. Further, all segments of ECG data that included arrhythmic events were excluded from analyses of HR, SDNN index, and RSA amplitude.

Quantification of Heart Rate and Heart Rate Variability

HR was evaluated by quantifying the number of beats per unit time (beats per minute, bpm). HR variability was evaluated using SDNN index and RSA amplitude. The SDNN index is hypothesized to represent the convergence of both sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation to the sino-atrial node, and was evaluated according to procedures described previously (52).

The amplitude of RSA has been hypothesized to represent the functional impact of myelinated vagal efferent pathways originating in the nucleus ambiguus on the sino-atrial node (see 54). RSA was assessed with time-frequency procedures (50,51) that have been validated with humans (54), applied to small mammals (53), modified for the prairie vole (30), and are appropriate for use during periods of both low activity and exercise (55–57). The following procedures were employed to ensure that the assumption of stationarity was not violated: (a) R–R intervals were time-sampled into equal time intervals with a sampling rate of 20Hz; and (b) time series were de-trended with a moving polynomial filter (58) that removed variance in the series below 1Hz (i.e., 21-point cubic polynomial). The residuals of these procedures were free of aperiodic and slow periodic processes that may have violated the assumption of stationarity. A bandpass filter was applied to define RSA by extracting only the variance in the HR spectrum between the frequencies of 1 and 4Hz, which has been confirmed through spectral analyses to be the frequency band in which breathing is observed in mammals of similar size to prairie voles (30,59,60).

Quantification of Arrhythmias

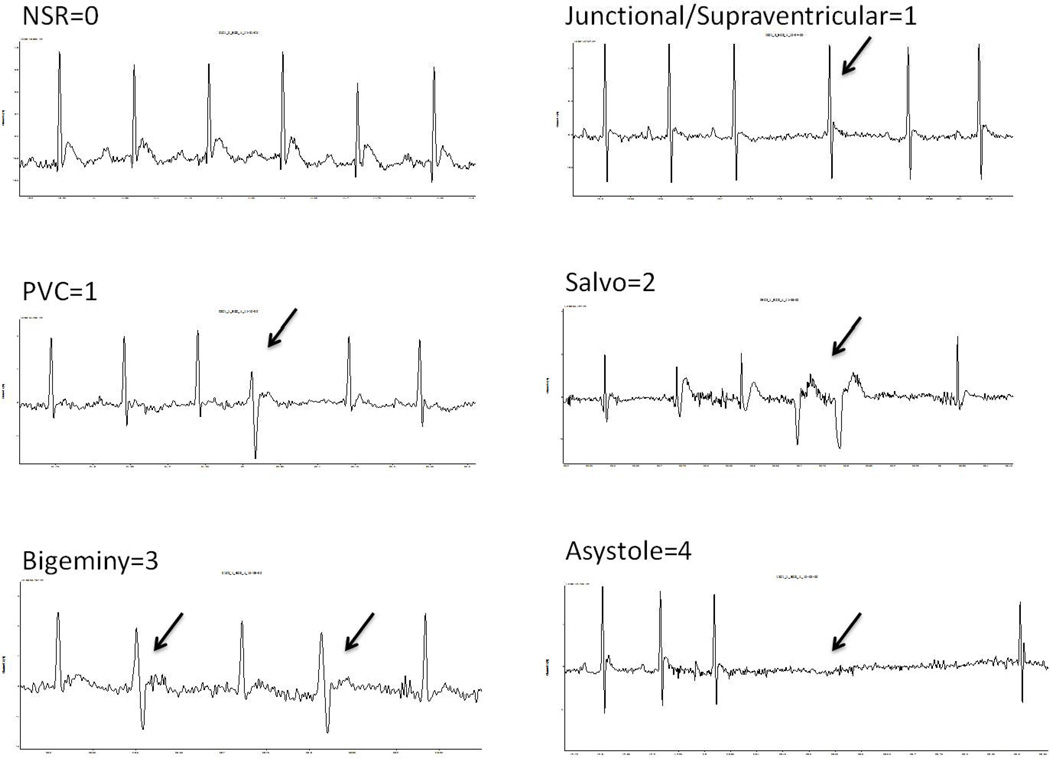

During the FST, arrhythmic events were quantified using modified procedures described previously (61). Specifically, each raw ECG signal was analyzed, and arrhythmic events were assigned the following point values modified according to the most frequently observed ECG events in prairie voles (Figure 1), as described in the Supplement of Khoo et al. (61): (a) 0 points for the absence of any arrhythmia; (b) 1 point for isolated supraventricular events (premature atrial, junctional or atrioventricular block) or an isolated premature ventricular or ventricular escape complex; (c) 2 points for supraventricular tachycardia, or 2 or 3 consecutive premature ventricular complexes (salvo); (d) 3 points for premature ventricular beats in a trigeminal or bigeminal pattern or non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (defined as ≥3 and ≤10 consecutive premature ventricular contractions); or (d) 4 points for sustained ventricular tachycardia (defined as >10 consecutive premature ventricular contractions) or asystole (absence of electrical activity during the loss of 2 or more consecutive cardiac cycles as defined by the length of the 2 preceding cardiac cycles). Using these categories, an arrhythmic burden was calculated for each animal, defined as the sum of the scored arrhythmic events during the swim period. Separate arrhythmic burdens were calculated for ventricular and supraventricular events.

Figure 1.

Electrocardiographic examples of the most common arrhythmias observed and classified in the prairie vole. Classification criteria are defined in the methods. Arrows denote arrhythmic event. NSR = normal sinus rhythm; PVC = premature ventricular contraction.

Data Analyses

Data are presented as means ± SEM for all analyses and figures. A value of P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Repeated variables were analyzed with mixed-design analyses of variance (ANOVA), with group (paired or isolated) as the independent factor and time (pre-isolation, post-isolation, and during the FST) as the repeated factor. Single variables and multiple comparisons were conducted using a priori Student’s t-tests.

RESULTS

Recovery Following Surgical Procedures

All animals showed a predictable recovery pattern following implantation of the radiotelemetry transmitter, including the following: (a) visible signs of eating, drinking (water and 2% sucrose), and periodic activity [conforming to an approximate ultradian cycle (30)] within 24 hours after surgery; (b) visible signs of urination and defecation within 24 hours after surgery; (c) recovery of core body temperature (37.5°C) within 48 hours after surgery; (d) appropriate healing of suture wounds within 5 days after surgery; and (e) evidence of a stable ECG signal within 14 days after surgery (data not shown). No animal in this study demonstrated an adverse effect following the surgical procedures.

Body Weight

Social isolation did not significantly affect body weight relative to pairing. The ANOVA yielded a main effect of time [F(2,24)=4.05, P<0.05]; all animals weighed slightly more at the end of the experiment compared to the baseline (pre-isolation) period. The main effect of group and the group × time interaction were not significant (P>0.05). No follow-up tests were conducted (data not shown).

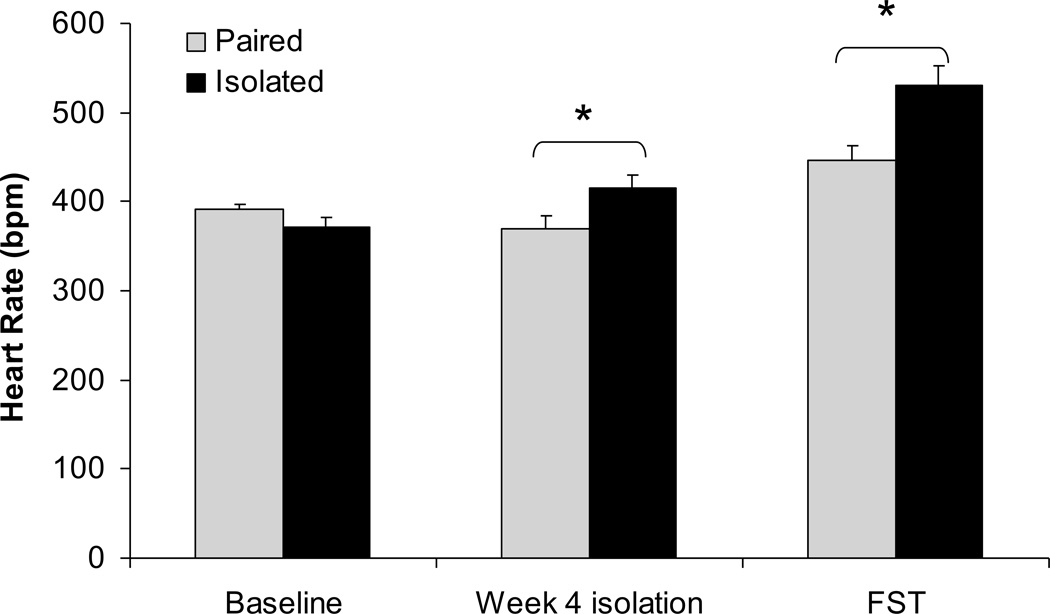

Heart Rate

Social isolation was associated with an increase in resting and stressor-induced HR relative to pairing (Figure 2). The ANOVA yielded main effects of group [F(1,12)=8.51, P<0.05] and time [F(2,24)=33.85, P<0.05], and a group×time interaction [F(2,24)=6.70, P<0.05]. The HR of paired and isolated groups did not differ prior to the isolation period (P>0.05). The HR of the isolated group was significantly higher than that of the paired group following 4 weeks of isolation [t(12)=2.24, P<0.05] and during the FST [t(12)=3.11, P<0.05]. Body temperature did not differ between the two groups (isolated: 36.3°C; paired: 36.6°C; P>0.05).

Figure 2.

Mean ± standard error of the mean heart rate in paired and isolated prairie voles at baseline (before isolation), after 4 weeks of isolation, and during the forced swim test (FST). * p < .05 between the paired and isolated groups.

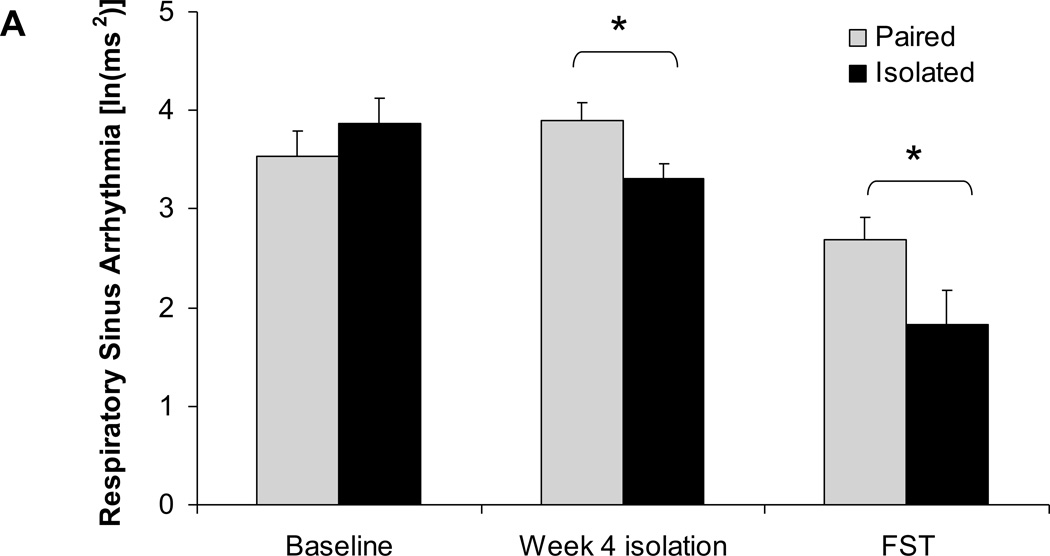

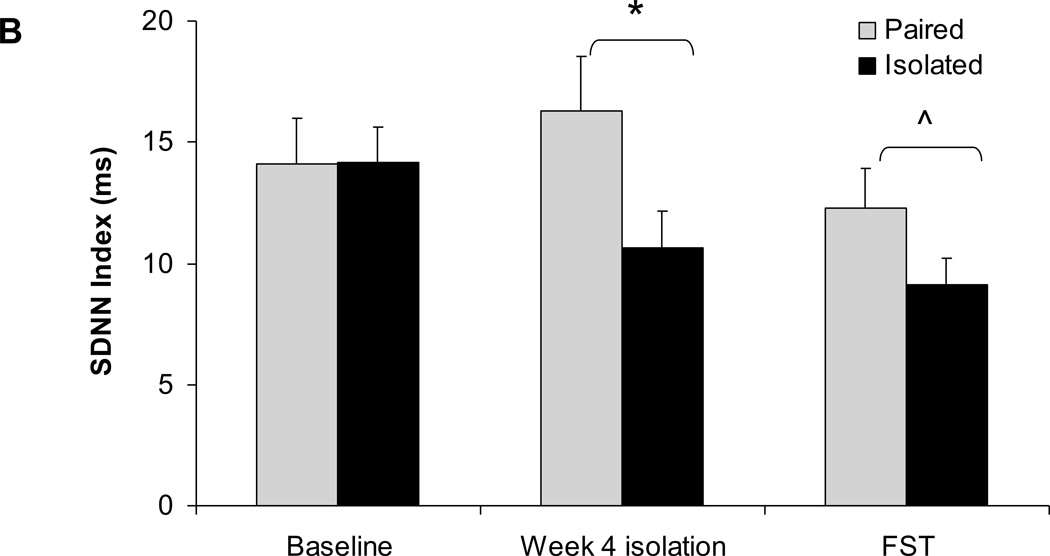

Heart Rate Variability

Social isolation was associated with a reduction in resting HR variability (RSA amplitude and SDNN index) and a reduction in stressor-induced HR variability (RSA amplitude) (Figure 3). The ANOVA for RSA amplitude yielded a main effect of time [F(2,24)=23.48, P<0.05] and a group×time interaction [F(2,24)=1.38, P<0.05]. The RSA amplitude of paired and isolated groups did not differ prior to isolation (P>0.05), however this value was significantly lower in the isolated group versus the paired group following 4 weeks of isolation [t(12)=2.54, P<0.05] and during the FST [t(12)=2.03, P<0.05].

Figure 3.

Mean ± standard error of the mean heart rate variability, including amplitude of respiratory sinus arrhythmia (A) and standard deviation of normal-to-normal intervals (SDNN index; B) in paired and isolated prairie voles at baseline (before isolation), after 4 weeks of isolation, and during the forced swim test (FST). * p < .05 between the paired and isolated groups. ^ p < .07 between the paired and isolated groups.

The ANOVA for SDNN index yielded a main effect of group [F(1,12)=6.63, P<0.05]. A priori comparisons indicated that the two groups did not differ in SDNN index prior to isolation (P>0.05). The SDNN index was significantly lower in the isolated group versus the paired group following 4 weeks of isolation [t(12)=2.06, P<0.05], and was slightly (but non-significantly) lower in the isolated group during the FST [t(12)=1.60, P<0.07].

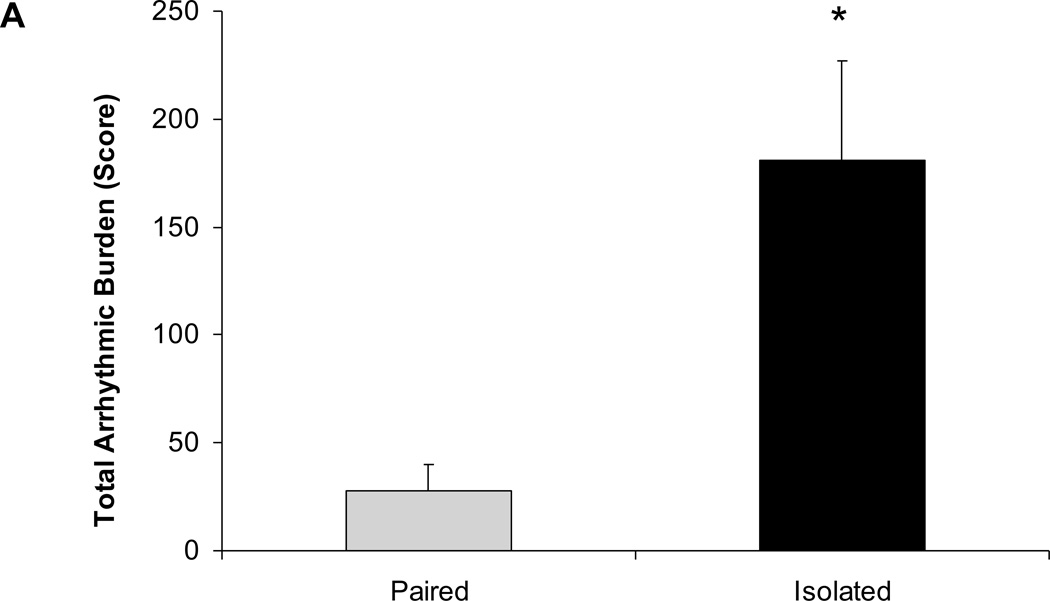

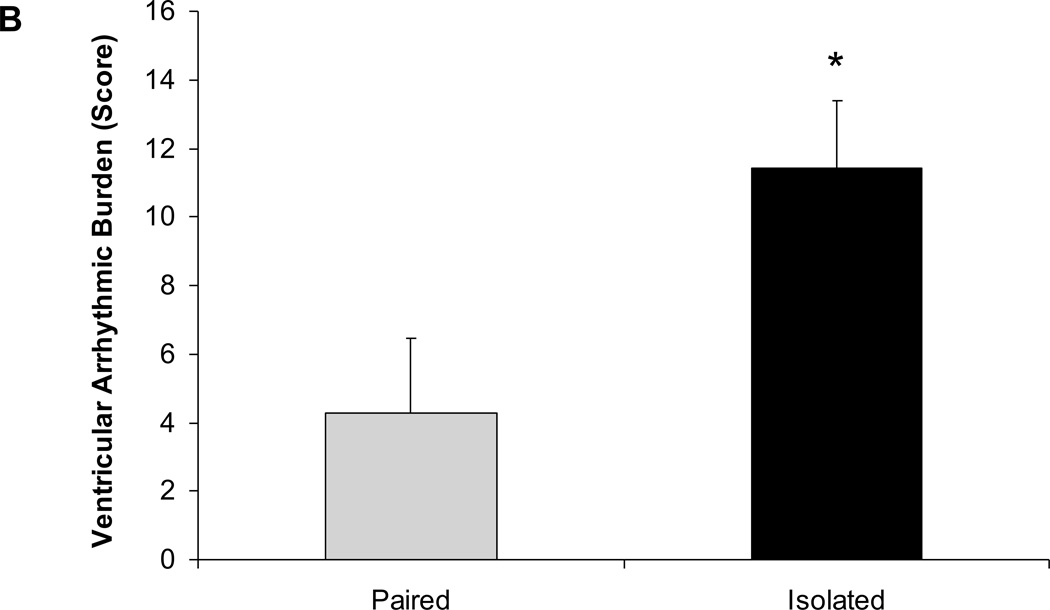

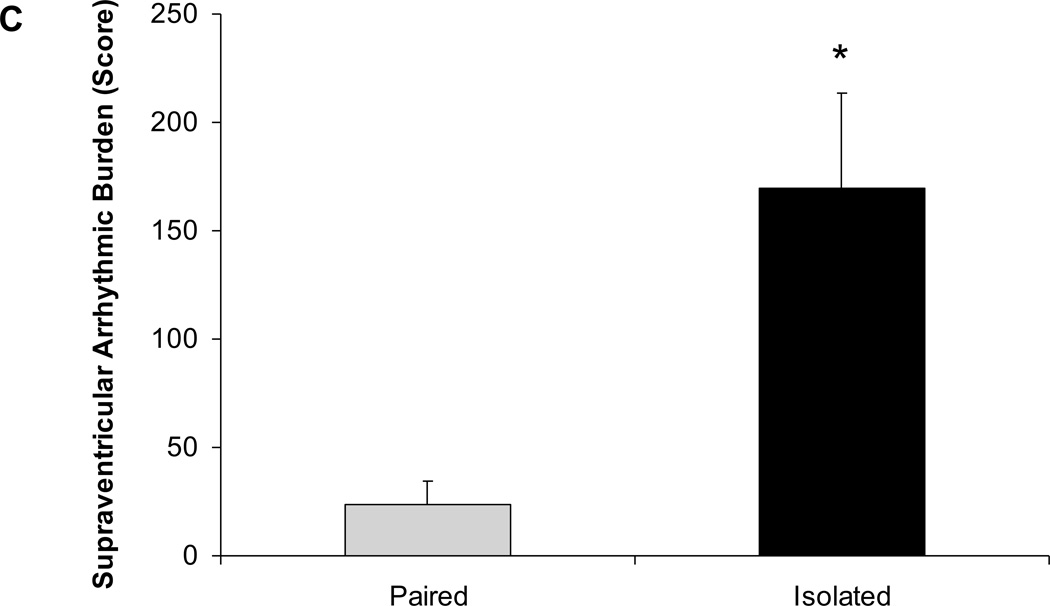

Arrhythmias

Social isolation was associated with an increased arrhythmic burden during the FST (Figure 4). Animals exposed to 4 weeks of social isolation displayed a significantly higher arrhythmic burden during the FST, versus those that had been paired [t(12)=3.22, P<0.05]. The increased arrhythmic burden in the isolated group was evident for both ventricular [t(12)=2.43, P<0.05] and supraventricular arrhythmias [t(12)=3.20, P<0.05].

Figure 4.

Mean ± standard error of the mean arrhythmic burden during the forced swim test, including total arrhythmic burden (A), ventricular arrhythmic burden (B), and supraventricular arrhythmic burden (C) in paired and isolated prairie voles. * p < .05 versus the respective paired group.

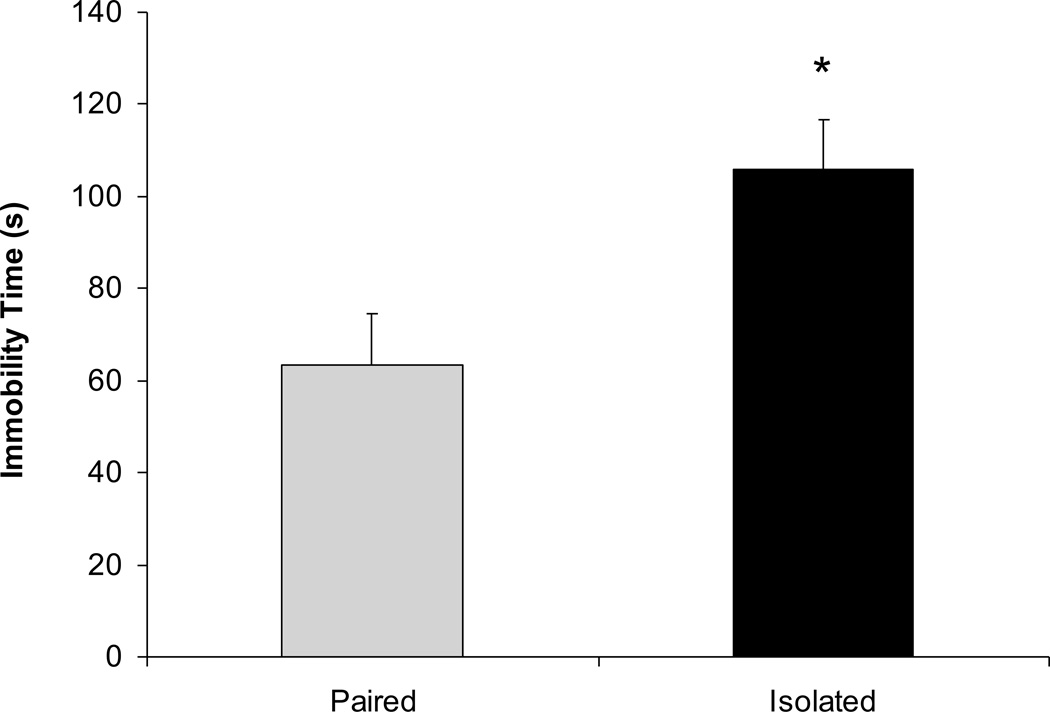

Behaviors

Social isolation was associated with an increase in depressive behavior (immobility) during the FST (Figure 5). The isolated group exhibited a greater amount of immobility versus the paired group [t(12)=2.73, P<0.05]. The activity count recorded by the radiotelemetry transmitter was lower in the isolated versus paired group [isolated: 40.6±7cpm; paired: 68.1±8cpm; t(12)=2.63, P<0.05].

Figure 5.

Mean ± standard error of the mean immobility time during a 5-minute forced swim test in paired and isolated prairie voles. The remainder of the 300 seconds is composed of the active coping behaviors of swimming, struggling, and climbing (see text for further description). * p < .05 versus the respective paired group.

DISCUSSION

The prairie vole is a rodent species with considerable utility for investigating the role of the social environment in mediating the link between mood and cardiovascular function. Prairie voles are heavily reliant on the social context, exhibiting characteristics of social monogamy similar to humans (27,28). In the current study, the disruption of a familial bond in female prairie voles produced both depression-relevant behaviors and cardiac dysfunction, including specific cardiac rate and rhythm disturbances during the FST. Conversely, social pairing with a female sibling was protective against these alterations. This study extends previous findings indicating that social isolation in prairie voles produces behavioral, autonomic, and neuroendocrine disruptions relevant to depression and cardiovascular disease (31,32,34,36), by demonstrating for the first time the integration of depressive behavior and cardiac reactivity during a validated operational measure of depression.

These results provide new insights into the mechanisms by which negative social experiences influence the association of depression and cardiovascular dysfunction, along with the protective effects of social support. Consistent with previous research (31), social isolation in prairie voles was associated with a depressive phenotype indicated by greater immobility during the FST. However, the present findings are novel in that they enhance the reliability of the behavioral consequences of social isolation in the prairie vole model. Although isolated prairie voles were less active than their paired counterparts in the FST (i.e., displaying lower levels of active movements and higher levels of immobility), these animals exhibited a pattern of cardiac responses that suggests an increased stress response, including greater HR, lower HR variability, and a greater incidence of cardiac arrhythmias. In contrast to social isolation, social pairing was protective against both depressive behaviors and cardiac reactivity; the animals in this group exhibited lower levels of immobility (i.e., increased active coping strategies), lower HR, higher HR variability, and a reduced incidence of arrhythmias.

The FST has been employed for the study of depressive behaviors and stress-coping ability in a variety of contexts, in multiple species including rats, mice, meadow voles, and prairie voles (31,33,37,38,62). This test has a high level of utility for screening and describing the effects of antidepressant drugs, supporting its predictive validity (37). The FST also has been demonstrated to possess both face and construct validity in the context of operationally defining the behavioral state of depression (37,41). The current results, indicating that isolated prairie voles show immobility combined with cardiac dysfunction and a greater arrhythmic burden, make an important contribution to the validity of the FST. These findings are in line with a recent observation that the FST increased HR in rats, versus pre-swim HR values (43). It can be concluded from these findings that that the immobility observed during the FST is representative of a helpless behavioral state in response to a psychologically stressful situation.

The results from the present study suggest that the capacity of the autonomic nervous system to regulate the heart is compromised as a result of negative social experiences, and conversely that pairing with a family member can be an appropriately protective form of social support. Socially isolated prairie voles (versus paired) displayed a significantly higher incidence of both ventricular and supraventricular arrhythmias, coupled with elevated HR and reduced HR variability, during the FST. This pattern of cardiac responses is indicative of autonomic imbalance, and may be an important mechanism by which depression increases the risk of cardiac mortality (63–68). These findings indicate that social pairing can be cardioprotective as well as behaviorally protective in the context of depression, and highlight the need for further investigation of the integration of behavior and cardiac function.

One possible explanation for the cardiac dysfunction in the current study is that social isolation elicited sympathovagal imbalance resulting in electrical destabilization of the myocardium and predisposition to cardiac arrhythmias during the stressor. Changes in cardiac autonomic tone exert powerful influence on the arrhythmogenic potential of the myocardium. With regard to ventricular arrhythmias, increases in sympathetic outflow are pro-arrhythmic, while increases in parasympathetic tone are more anti-arrhythmic (see for review 69). It is unknown whether the present results are primarily due to increased cardiac sympathetic tone, reduced parasympathetic tone, or a combination of these two. However, previous findings suggest that sympathetic and parasympathetic drive to the heart are altered in socially isolated prairie voles (32), and therefore may suggest that the arrhythmias exhibited in the present study are due to a combination of both sympathetic and parasympathetic dysfunction. Future experiments using more direct physiologic or neural approaches will be required to determine the changes in myocardial structure or cellular dysfunction, as well as possible dysregulation of autonomic nuclei in the brain.

The findings observed here complement and extend previous findings from both humans and animal models showing interactions among social experiences, depression, and autonomic dysregulation (26,70). As described previously, long-term social isolation in female prairie voles has been associated not only with depressive behaviors in multiple operational measures, but also with basal and stressor-induced cardiac dysfunction, sympathovagal imbalance, and exaggerated neural and physiological stress responses (31,32,34,35). Also, a prior history of trauma was associated with reduced RSA during an acute stressor in depressed women (71). In line with this finding, individuals with both depressive symptomatology and a high number of ventricular arrhythmias (greater than 10 arrhythmic events per hour) following myocardial infarction had an increased risk of mortality, versus those with either of these variables alone (3). Finally, in patients with cardiovascular dysfunction requiring the use of implantable defibrillators, those who perceived higher levels of social support displayed improved cardiovascular recovery following an acute mental stress task (72).

The present study extends previous research by describing the integration of depressive behaviors and cardiac dysfunction, and more specifically the presence of stressor-induced ventricular and supraventricular arrhythmias, in socially isolated prairie voles during the forced swim test. This study provides a foundation for additional investigation of the mechanisms by which the social environment influences emotion and autonomic balance. Further, these findings provide a strong basis for evaluating behavioral and neurobiological consequences of social stressors as well as the protective effects of social support, including both peripheral and central nervous system processes. Continued research using valid and reliable animal models, along with studies of human samples, will therefore increase our understanding of the link between depression and cardiovascular disease and lead to the development of more effective treatments for individuals with these disorders.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to Emily Aberson, Stephanie Allen, Sue Carter, Ph.D., Parag Davé, Heather Giless, Erica Hymen, Damon Lamb, Gregory Lewis, Vitoria McDaniel, Stephen Porges, Ph.D., Melissa-Ann Scotti, Ph.D., and Loren Weese for assistance. This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants MH73233 and MH77581.

Acronyms

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- DSI

Data Sciences International

- ECG

electrocardiographic

- FST

forced swim test

- HR

heart rate

- RSA

respiratory sinus arrhythmia

- SDNN

standard deviation of normal-to-normal intervals

- SEM

standard error of the mean.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Freedland KE, Rich MW, Skala JA, Carney RM, Dávila-Román VG, Jaffe AS. Prevalence of depression in hospitalized patients with congestive heart failure. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:119–128. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000038938.67401.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barefoot JC, Schroll M. Symptoms of depression, acute myocardial infarction, and total mortality in a community sample. Circulation. 1996;93:1976–1980. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.11.1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frasure-Smith N, Lespérance F, Talajic M. Depression and 18-month prognosis after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1995;91:999–1005. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.4.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Penninx BWJH, Beekman ATF, Honig A, Deeg DJH, Schoevers RA, van Eijk JTM, van Tilburg W. Depression and cardiac mortality: results from a community-based longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:221–227. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.3.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carney RM, Freedland KE. Depression, mortality, and medical morbidity in patients with coronary heart disease. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:241–247. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van der Kooy K, van Hout H, Marwijk H, Marten H, Stehouwer C, Beekman A. Depression and the risk for cardiovascular diseases: systematic review and meta analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22:613–626. doi: 10.1002/gps.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glassman AH. Depression and cardiovascular comorbidity. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2007;9:9–17. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2007.9.1/ahglassman. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Jonge P, Rosmalen JGM, Kema IP, Doornbos B, van Melle JP, Pouwer F, Kupper N. Psychophysiological biomarkers explaining the association between depression and prognosis in coronary artery patients: A critical review of the literature. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;35:84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grippo AJ. Mechanisms underlying altered mood and cardiovascular dysfunction: the value of neurobiological and behavioral research with animal models. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009;33:171–180. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwerdtfeger A, Friedrich-Mai P. Social interaction moderates the relationship between depressive mood and heart rate variability: evidence from an ambulatory monitoring study. Health Psychol. 2009;28:501–509. doi: 10.1037/a0014664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steptoe A, Owen N, Kunz-Ebrecht SR, Brydon L. Loneliness and neuroendocrine, cardiovascular, and inflammatory stress responses in middle-aged men and women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29:593–611. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4530(03)00086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Crawford LE, Ernst JM, Burleson MH, Kowalewski RB, Malarkey WB, Van Cauter E, Berntson GG. Loneliness and health: potential mechanisms. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:407–417. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200205000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berkman LF, Melchior M, Chastang JF, Niedhammer I, Leclerc A, Goldberg M. Social integration and mortality: a prospective study of French employees of Electricity of France-Gas of France: the GAZEL Cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:167–174. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thurston RC, Kubzansky LD. Women, loneliness, and incident coronary heart disease. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:836–842. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181b40efc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC. Social isolation and health, with an emphasis on underlying mechanisms. Perspec Biol Med. 2003;46(Suppl 3):S39–S52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rutledge T, Linke SE, Olson MB, Francis J, Johnson BD, Bittner V, York K, McClure C, Kelsey SF, Reis SE, Cornell CE, Vaccarino V, Sheps DS, Shaw LJ, Krantz DS, Parashar S, Merz CN. Social networks and incident stroke among women with suspected myocardial ischemia. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:282–287. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181656e09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaplan GA, Salonen JT, Cohen RD, Brand RJ, Syme SL, Puska P. Social connections and mortality from all causes and from cardiovascular disease: prospective evidence from eastern Finland. Am J Epidemiol. 1988;128:370–380. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rutledge T, Reis SE, Olson M, Owens J, Kelsey SF, Pepine CJ, Mankad S, Rogers WJ, Bairey Merz CN, Sopko G, Cornell CE, Sharaf B, Matthews KA. Social networks are associated with lower mortality rates among women with suspected coronary disease: the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute sponsored Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation study. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:882–888. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000145819.94041.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eng PM, Rimm EB, Fitzmaurice G, Kawachi I. Social ties and change in social ties in relation to subsequent total and cause-specific mortality and coronary heart disease incidence in men. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:700–709. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.8.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramsay S, Ebrahim S, Whincup P, Papacosta O, Morris R, Lennon L, Wannamethee SG. Social engagement and the risk of cardiovascular disease mortality: results of a prospective population based study of older men. Annals of Epidemiology. 2008;18:476–483. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kop WJ, Berman DS, Gransar H, Wong ND, Miranda-Peats R, White MD, Shin M, Bruce M, Krantz DS, Rozanski A. Social network and coronary artery calcification in asymptomatic individuals. Psychosom Med. 2005;37:343–352. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000161201.45643.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brummett BH, Mark DB, Siegler IC, Williams RB, Babyak MA, Clapp-Channing NE, Barefoot JC. Perceived social support as a predictor of mortality in coronary patients: effects of smoking, sedentary behavior, and depressive symptoms. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:41–45. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000149257.74854.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hemingway H, Malik M, Marmot M. Social and psychosocial influences on sudden cardiac death, ventricular arrhythmia and cardiac autonomic function. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:1082–1101. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2000.2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frasure-Smith N, Lespérance F, Gravel G, Masson A, Juneau M, Talajic M, Bourassa MG. Social support, depression, and mortality during the first year after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2000;101:1919–1924. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.16.1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carter CS, Grippo AJ, Pournajafi-Nazarloo H, Ruscio MG, Porges SW. Oxytocin, vasopressin and sociality. Prog Brain Res. 2008;170:331–336. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)00427-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grippo AJ. The utility of animal models in understanding links between psychosocial processes and cardiovascular health. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2011;5/4:164–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00342.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carter CS, DeVries AC, Getz LL. Physiological substrates of mammalian monogamy: the prairie vole model. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1995;19:303–314. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(94)00070-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carter CS, Keverne EB. The neurobiology of social affiliation and pair bonding. Horm Brain Behav. 2002;1:299–337. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Getz LL, Carter CS. Prairie-vole partnerships. Am Scientist. 1996;84:56–62. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grippo AJ, Lamb DG, Carter CS, Porges SW. Cardiac regulation in the socially monogamous prairie vole. Physiol Behav. 2007;90:386–393. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grippo AJ, Wu KD, Hassan I, Carter CS. Social isolation in prairie voles induces behaviors relevant to negative affect: toward the development of a rodent model focused on cooccurring depression and anxiety. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25:E17–E26. doi: 10.1002/da.20375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grippo AJ, Lamb DG, Carter CS, Porges SW. Social isolation disrupts autonomic regulation of the heart and influences negative affective behaviors. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:1162–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bosch OJ, Nair HP, Ahern TH, Neumann ID, Young LJ. The CRF system mediates increased passive stress-coping behavior following the loss of a bonded partner in a monogamous rodent. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:1406–1415. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grippo AJ, Gerena D, Huang J, Kumar N, Shah M, Ughreja R, Carter CS. Social isolation induces behavioral and neuroendocrine disturbances relevant to depression in female and male prairie voles. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32:966–980. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grippo AJ, Sgoifo A, Mastorci F, McNeal N, Trahanas DM. Cardiac dysfunction and hypothalamic activation during a social crowding stressor in prairie voles. Autonom Neurosci Basic Clin. 2010;156:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grippo AJ, Carter CS, McNeal N, Chandler DL, LaRocca MA, Bates SL, Porges SW. 24-Hour autonomic dysfunction and depressive behaviors in an animal model of social isolation: implications for the study of depression and cardiovascular disease. Psychosom Med. 2011;73:59–66. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31820019e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cryan JF, Valentino RJ, Lucki I. Assessing substrates underlying the behavioral effects of antidepressants using the modified rat forced swimming test. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29:547–569. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kurtuncu M, Luka LJ, Dimitrijevic N, Uz T, Manev H. Reliability assessment of an automated forced swim test device using two mouse strains. J Neurosci Methods. 2005;149:26–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Willner P. The validity of animal models of depression. Psychopharmacology. 1984;83:1–16. doi: 10.1007/BF00427414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Porsolt RD, Le Pichon M, Jalfre M. Depression: a new animal model sensitive to antidepressant treatments. Nature. 1977;266:730–732. doi: 10.1038/266730a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bielajew C, Konkle AT, Kentner AC, Baker SL, Stewart A, Hutchins AA, Barbagallo LS, Fouriezos G. Strain and gender specific effects in the forced swim test: effects of previous stress exposure. Stress. 2003;6:269–280. doi: 10.1080/10253890310001602829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Connor TJ, Kelly JP, Leonard BE. Forced swim test-induced neurochemical, endocrine, and immune changes in the rat. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1997;58:961–967. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(97)00028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pintér O, Domokos A, Mergl Z, Mikics E, Zelena D. Do stress hormones connect environmental effects with behavior in the forced swim test? Endocrine Journal. 2011;58:395–407. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k10e-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Konkle AT, Baker SL, Kentner AC, Barbagallo LSM, Merali Z, Bielajew C. Evaluation of the effects of chronic mild stressors on hedonic and physiological responses: sex and strain compared. Brain Res. 2003;992:227–238. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grippo AJ, Cushing BS, Carter CS. Depression-like behavior and stressor-induced neuroendocrine activation in female prairie voles exposed to chronic social isolation. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:149–157. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31802f054b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cushing BS, Carter CS. Peripheral pulses of oxytocin increase partner preferences in female, but not male, prairie voles. Horm Behav. 2000;37:49–56. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1999.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taylor SE, Gonzaga GC, Klein LC, Hu P, Greendale GA, Seeman TE. Relation of oxytocin to psychological stress responses and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis activity in older women. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:238–245. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000203242.95990.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carter CS, Witt DM, Schneider J, Harris ZL, Volkening D. Male stimuli are necessary for female sexual behavior and uterine growth in prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster) Horm Behav. 1987;21:74–82. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(87)90032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grippo AJ, Trahanas DM, Zimmerman RR, II, Porges SW, Carter CS. Oxytocin protects against negative behavioral and autonomic consequences of long-term social isolation. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:1542–1553. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Porges SW. Method and apparatus for evaluating rhythmic oscillations in aperiodic physiological response systems. 4,510,944. Patent Number. 1985 Apr 16;

- 51.Porges SW, Bohrer RE. Analyses of periodic processes in psychophysiological research. In: Cacioppo JT, Tassinary LG, editors. Principles of psychophysiology: physical, social, and inferential elements. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1990. pp. 708–753. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology, North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Circulation. 1996;93:1043–1065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yongue BG, McCabe PM, Porges SW, Rivera M, Kelley SL, Ackles PK. The effects of pharmacological manipulations that influence vagal control of the heart on heart period, heart-period variability and respiration in rats. Psychophysiology. 1982;19:426–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1982.tb02499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Porges SW. The polyvagal perspective. Biol Psychol. 2007;74:116–143. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Houtveen JH, Rietveld S, de Geus EJ. Contribution of tonic vagal modulation of heart rate, central respiratory drive, respiratory depth, and respiratory frequency to respiratory sinus arrhythmia during mental stress and physical exercise. Psychophysiology. 2002;39:427–436. doi: 10.1017.S0048577202394022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Byrne EA, Fleg JL, Vaitkevicius PV, Wright J, Porges SW. Role of aerobic capacity and body mass index in the age-associated decline in heart rate variability. J Appl Physiol. 1996;81:743–750. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.2.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Porges SW, Heilman KJ, Bazhenova OV, Bal E, Doussard-Roosevelt JA, Kolekin M. Does motor activity during psychophysiological paradigms confound the quantification and interpretation of heart rate and heart rate variability measures in young children? Dev Psychobiol. 2007;49:485–494. doi: 10.1002/dev.20228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Porges SW, Byrne EA. Research methods for measurement of heart rate and respiration. Biol Psychol. 1992;324:93–130. doi: 10.1016/0301-0511(92)90012-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gehrmann J, Hammer PE, Maguire CT, Wakimoto H, Triedman JK, Berul CI. Phenotypic screening for heart rate variability in the mouse. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H733–H740. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.2.H733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ishii K, Kuwahara M, Tsubone H, Sugano S. Autonomic nervous function in mice and voles (Microtus arvalis): investigation by power spectral analysis of heart rate variability. Lab Animals. 1996;30:359–364. doi: 10.1258/002367796780739880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Khoo MSC, Li J, Singh MV, Yang Y, Kannankeril P, Wu Y, Grueter CE, Guan X, Oddis CV, Zhang R, Mendes L, Ni G, Madu EC, Yang J, Bass M, Gomez RJ, Wadzinski BE, Olson EN, Colbran RJ, Anderson ME. Death, cardiac dysfunction, and arrhythmias are increased by calmodulin kinase II in calcineurin cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2006;114:1352–1359. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.644583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Galea LAM, Lee TTY, Kostaras X, Sidhu JA, Barr AM. High levels of estradiol impair spatial performance in the Morris water maze and increase 'depressive-like' behaviors in the female meadow vole. Physiol Behav. 2002;77:217–225. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00849-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Barton DA, Dawood T, Lambert EA, Esler MD, Haikerwal D, Brenchley C, Socratous F, Kaye DM, Schlaich MP, Hickie I, Lambert GW. Sympathetic activity in major depressive disorder: identifying those at increased cardiac risk? J Hypertens. 2007;25:2117–2124. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32829baae7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Carney RM, Saunders RD, Freedland KE, Stein P, Rich MW, Jaffe AS. Association of depression with reduced heart rate variability in coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76:562–564. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80155-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pitzalis MV, Iacoviello M, Todarello O, Fioretti A, Guida P, Massari F, Mastropasqua F, Russo GD, Rizzon P. Depression but not anxiety influences the autonomic control of heart rate after myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2001;141:765–771. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.114806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Grippo AJ, Moffitt JA, Johnson AK. Cardiovascular alterations and autonomic imbalance in an experimental model of depression. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;282:R1333–R1341. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00614.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Grippo AJ, Santos CM, Johnson RF, Beltz TG, Martins JB, Felder RB, Johnson AK. Increased susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmias in a rodent model of experimental depression. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H619–H626. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00450.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Carney RM, Freedland KE, Rich MW, Smith LJ, Jaffe AS. Ventricular tachycardia and psychiatric depression in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Med. 1993;95:23–28. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(93)90228-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Verrier RL, Antzelevich C. Autonomic aspects of arrhythmogenesis: the enduring and the new. Current Opinion in Cardiology. 2004;19:2–11. doi: 10.1097/00001573-200401000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Taggart P, Boyett MR, Logantha S, Lambiase PD. Anger, emotion, and arrhythmias: from brain to heart. Frontiers in Physiology. 2011;2:1–11. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2011.00067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cyranowski JM, Hofkens TL, Swartz HA, Salomon K, Gianaros PJ. Cardiac vagal control in nonmedicated depressed women and nondepressed controls: impact of depression status, lifetime trauma history, and respiratory factors. Psychosom Med. 2011;73:336–343. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318213925d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lache B, Meyer T, Herrmann-Lingen C. Social support predicts hemodynamic recovery from mental stress in patients with implanted defribrillators. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63:515–523. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]