Background: The A128T substitution in HIV-1 integrase (IN) confers resistance to allosteric integrase inhibitors (ALLINIs).

Results: The A128T substitution does not significantly alter ALLINI IC50 values for IN-LEDGF/p75 binding but confers marked resistance to ALLINI-induced aberrant integrase multimerization.

Conclusion: Allosteric perturbation of HIV-1 integrase multimerization underlies ALLINI antiviral activity.

Significance: Our findings underscore the mechanism of ALLINI action and will facilitate development of second-generation compounds.

Keywords: HIV-1, Infectious Diseases, Integrase, Pharmacology, Structural Biology, Allosteric Inhibitors, Drug Resistance, Protein-DNA Interactions, Protein-Drug Integrations, Protein-Protein Interactions

Abstract

Allosteric HIV-1 integrase (IN) inhibitors (ALLINIs) are a very promising new class of anti-HIV-1 agents that exhibit a multimodal mechanism of action by allosterically modulating IN multimerization and interfering with IN-lens epithelium-derived growth factor (LEDGF)/p75 binding. Selection of viral strains under ALLINI pressure has revealed an A128T substitution in HIV-1 IN as a primary mechanism of resistance. Here, we elucidated the structural and mechanistic basis for this resistance. The A128T substitution did not affect the hydrogen bonding between ALLINI and IN that mimics the IN-LEDGF/p75 interaction but instead altered the positioning of the inhibitor at the IN dimer interface. Consequently, the A128T substitution had only a minor effect on the ALLINI IC50 values for IN-LEDGF/p75 binding. Instead, ALLINIs markedly altered the multimerization of IN by promoting aberrant higher order WT (but not A128T) IN oligomers. Accordingly, WT IN catalytic activities and HIV-1 replication were potently inhibited by ALLINIs, whereas the A128T substitution in IN resulted in significant resistance to the inhibitors both in vitro and in cell culture assays. The differential multimerization of WT and A128T INs induced by ALLINIs correlated with the differences in infectivity of HIV-1 progeny virions. We conclude that ALLINIs primarily target IN multimerization rather than IN-LEDGF/p75 binding. Our findings provide the structural foundations for developing improved ALLINIs with increased potency and decreased potential to select for drug resistance.

Introduction

HIV-1 integrase (IN)2 is an important therapeutic target, as its function is essential for viral replication (1). IN catalyzes the insertion of the reverse-transcribed RNA genome into human chromatin in a two-step reaction (2). During the initial step (termed 3′-processing), IN removes a GT dinucleotide from each 3′ terminus of the viral DNA. The subsequent transesterification reactions (termed DNA strand transfer) covalently join the recessed viral DNA ends into the host genome. To carry out these reactions, highly dynamic IN subunits assemble in the presence of cognate DNA to form the stable synaptic complex or intasome (3–5). Premature multimerization of HIV-1 IN by various ligands in the absence of cognate DNA restricts the functionally essential dynamic interplay between individual subunits and DNA and thus impairs IN catalytic activities (3, 4, 6, 7).

A cellular protein, lens epithelium-derived growth factor (LEDGF)/p75, markedly enhances the integration process in vitro and in infected cells. LEDGF/p75 tethers stable synaptic complexes to chromatin via direct interactions of its N-terminal chromatin-binding domain with nucleosomes, whereas its C-terminal IN-binding domain links to HIV-1 IN (8, 9). Structural studies (10, 11) have elucidated the principal interacting interfaces between the LEDGF/p75 IN-binding domain and the HIV-1 IN catalytic core domain (CCD). The cornerstone of this protein-protein interaction is a hydrogen bonding network between the side chain oxygen atoms of LEDGF/p75 Asp-366 and the IN backbone amides of Glu-170 and His-171 (10, 11). These findings have opened up new venues for antiviral drug discovery.

Using a structure-based rational drug design approach, Christ et al. (12) developed 2-(quinolin-3-yl)acetic acid derivatives, which inhibit the IN-LEDGF/p75 interaction in vitro and HIV-1 replication in cell culture. Paradoxically, the identical class of compounds has emerged from a high-throughput screen for IN 3′-processing activity (13). Subsequent studies from our group and others demonstrated that 2-(quinolin-3-yl)acetic acid derivatives exhibit a multimodal mechanism of action by allosterically modulating the IN structure, which affects both IN-LEDGF/p75 binding and catalytic activity (14–16). Accordingly, we have proposed to name this class of inhibitors as allosteric IN inhibitors (ALLINIs). Structural studies have shown that the carboxylic acid of ALLINIs hydrogen bonds with the backbone amides of Glu-170 and His-171 and thus occupy the principal LEDGF/p75-binding interface (12, 14, 16). At the same time, the quinoline core and the substituted phenyl group of the inhibitor bridge the two IN subunits and promote allosteric multimerization of the protein. As a result, ALLINIs potently inhibit both IN-LEDGF/p75 binding and LEDGF/p75-independent IN catalytic activities.

The ability of ALLINIs to impair steps in the viral replication cycle that extend beyond IN catalytic function results in a highly cooperative inhibition of HIV-1 replication (14). Along these lines, it was recently reported that HIV-1 particles made in the presence of ALLINIs are noninfectious (15). Whereas the Food and Drug Administration-approved HIV-1 IN strand transfer inhibitor raltegravir (RAL) exhibits a Hill coefficient of 1, which is consistent with only a single or non-cooperative mode of action, ALLINIs impair viral replication with a Hill coefficient of ∼4, indicating a highly cooperative mode of action (14). Compounds with a high cooperativity are particularly desirable for superior clinical outcomes because they enable stronger viral suppression at clinical drug concentrations (17, 18).

The A128T substitution in HIV-1 IN has been identified from cell culture assays as a primary mechanism for resistance to ALLINI compounds (12, 16, 19). Ala-128 is located at the IN dimer interface in the pocket occupied by ALLINIs or LEDGF/p75. Here, we have investigated the structural and mechanistic properties for the resistance of A128T IN to ALLINIs. Strikingly, the A128T substitution only modestly affected ALLINI IC50 values for IN-LEDGF/p75 binding but markedly altered the multimerization of IN in the presence of the inhibitors. As a result, the catalytic activities of the WT protein were potently inhibited by ALLINIs, whereas A128T IN exhibited significant resistance to the inhibitor. Furthermore, considerably higher concentrations of ALLINIs were required to inhibit the infectivity of the A128T mutant virus compared with the WT counterpart. Taken together, our studies highlight that aberrant IN multimerization is the primary target of this class of inhibitors and thus provide the structural foundations for the development of second-generation ALLINIs with increased potency and decreased potential to select for drug resistance.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Antiviral Compounds

ALLINI-1, referred to as BI-1001 previously, was synthesized as described (14). The synthesis of ALLINI-2 is described in supplemental Figs. S1 and S2. RAL and saquinavir were obtained from the National Institutes of Health AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program.

Expression and Purification of Recombinant Proteins

LEDGF/p75 and WT and A128T HIV-1 IN recombinant proteins with His or FLAG tags were expressed in Escherichia coli and purified as described previously (14).

Protein-Protein Interaction Assays

Homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence (HTRF)-based IN-LEDGF/p75 binding and IN multimerization assays were performed as described previously (14). The HTRF signal was recorded using a PerkinElmer EnSpire multimode plate reader.

Solubility Assays

WT IN was diluted to a final concentration of 100 nm in buffer containing 25 mm Tris (pH 7.4), 2 mm MgCl2, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 1 mg/ml BSA, and either 150 or 750 mm NaCl. Increasing concentrations of ALLINI-1 or ALLINI-2 were then added to the mixture and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The mixture was subjected to centrifugation for 2 min at 2000 × g. The supernatant was collected, and the pellet was washed three times with the same buffer. The supernatant and pellet fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and IN was detected with anti-His antibody (Abcam).

3′-Processing, Strand Transfer, and LEDGF/p75-dependent Integration Assays

Gel-based LEDGF/p75-dependent and LEDGF/p75-independent integration activity assays were performed as described previously (14). A recently reported time-resolved fluorescence assay (16) was used to quantify IN 3′-processing and strand transfer activities. The HTRF-based LEDGF/p75-dependent integration activity was measured by adding recombinant LEDGF/p75 protein to the assay mixture prior to the incubation with labeled DNA substrates. The time-resolved fluorescence signal was recorded using a PerkinElmer EnSpire multimode plate reader.

Size Exclusion Chromatography

Experiments were performed with a Superdex 200 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) at 0.5 ml/min in elution buffer containing 20 mm HEPES (pH 6.8), 750 mm NaCl, 10 mm MgSO4, 0.2 mm EDTA, 5 mm β-mercaptoethanol, 5% glycerol, and 200 μm ZnCl2. IN (20 μm) was incubated with ALLINIs or Me2SO (control) for 30 min and then subjected to size exclusion chromatography. The column was calibrated with the following proteins: bovine thyroglobulin (670,000 Da), bovine γ-globulin (158,000 Da), chicken ovalbumin (44,000 Da), horse myoglobin (17,000 Da), and vitamin B12 (1,350 Da). Proteins were detected by absorbance at 280 nm. All the procedures were performed at 4 °C.

Crystallization and X-ray Structure Determination

The HIV-1 IN CCD (residues 50–212 containing the F185K substitution) and A128T CCD (with an extra substitution of A128T) were expressed and purified as described (20). The CCD was concentrated to 8 mg/ml and crystallized at 4 °C using the hanging drop vapor diffusion method. The crystallization buffer contained 10% PEG 8000, 0.1 m sodium cacodylate (pH 6.5), 0.1 m ammonium sulfate, and 5 mm DTT. Crystals reached 0.1–0.2 mm within 4 weeks. The A128T CCD was concentrated to 8.5 mg/ml and crystallized at room temperature (20 °C) using the hanging drop vapor diffusion method. The crystallization buffer contained 0.1 m sodium cacodylate (pH 6.5), 1.4 m sodium acetate, and 5 mm DTT. The crystals reached 0.2–0.4 mm within 1 week.

A soaking buffer containing 5 mm ALLINI-1 or ALLINI-2 was prepared by dissolving the compound in crystallization buffer supplemented with 10% Me2SO. The protein crystal was soaked in the buffer for 8 h before flash-freezing in liquid N2. Diffraction data were collected at 100 F on a Rigaku R-AXIS 4++ image plate detector at the Ohio State University Crystallography Facility. Intensity data integration and reduction were performed using the HKL2000 program (21). The molecular replacement program Phaser (22) in the CCP4 package (23) was used to solve the structure, with the HIV-1 IN CCD structure (Protein Data Bank code 1ITG) (20) serving as starting model. The Coot program (24) was used for the subsequent refinement and building of the structure. Refmac5 (25) of the CCP4 package was used for the restraint refinement. TLS (26) and restraint refinement was applied for the last step of the refinement. The crystals belonged to space group P3121 with cell dimensions a = b = 73 and c = 65 Å, with one 18-kDa monomer in the asymmetric unit. The data collection and refinement statistics are listed in supplemental Table 1. Coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession numbers 4JLH, 4GW6, and 4GVM (supplemental Table 1).

HIV-1 Virion Production and Infectivity Assay

HEK293T and HeLa TZM-bl cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagles medium (Invitrogen), 10% FBS (Invitrogen), and 1% antibiotic/antimycotic (Invitrogen) at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Cultures of HEK293T cells (2 × 105 cells/well of a 6-well plate in 2 ml of complete medium) were transfected with 2 μg of pNL4–3 (WT or A128T mutant) at a 1:3 ratio of DNA to X-tremeGENE HP (Roche Applied Science) following the manufacturer's protocol. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, cells were washed once with complete medium, and the culture supernatant was replaced with complete medium containing Me2SO, RAL (250 nm), ALLINI-1, or ALLINI-2 (at the indicated concentrations). After 1 h, the culture supernatant was again replaced with fresh complete medium containing either Me2SO or the indicated inhibitors. The virus-containing cell-free supernatant was collected after 24 h, and HIV-1 Gag p24 ELISA (ZeptoMetrix) was performed following the manufacturer's protocol. Virions equivalent to 2–4 ng of HIV-1 p24 was used to infect 2 × 105 HeLa TZM-bl cells in the presence of 8 μg/ml Polybrene (Sigma). HeLa TZM-bl cultures were extracted in 1× reporter lysis buffer (Promega), and virion infectivity was measured using the luciferase assay (Promega).

Antiviral Activity Assays

ALLINI EC50 values were determined in spreading HIV-1 replication assays as described previously (14).

RESULTS

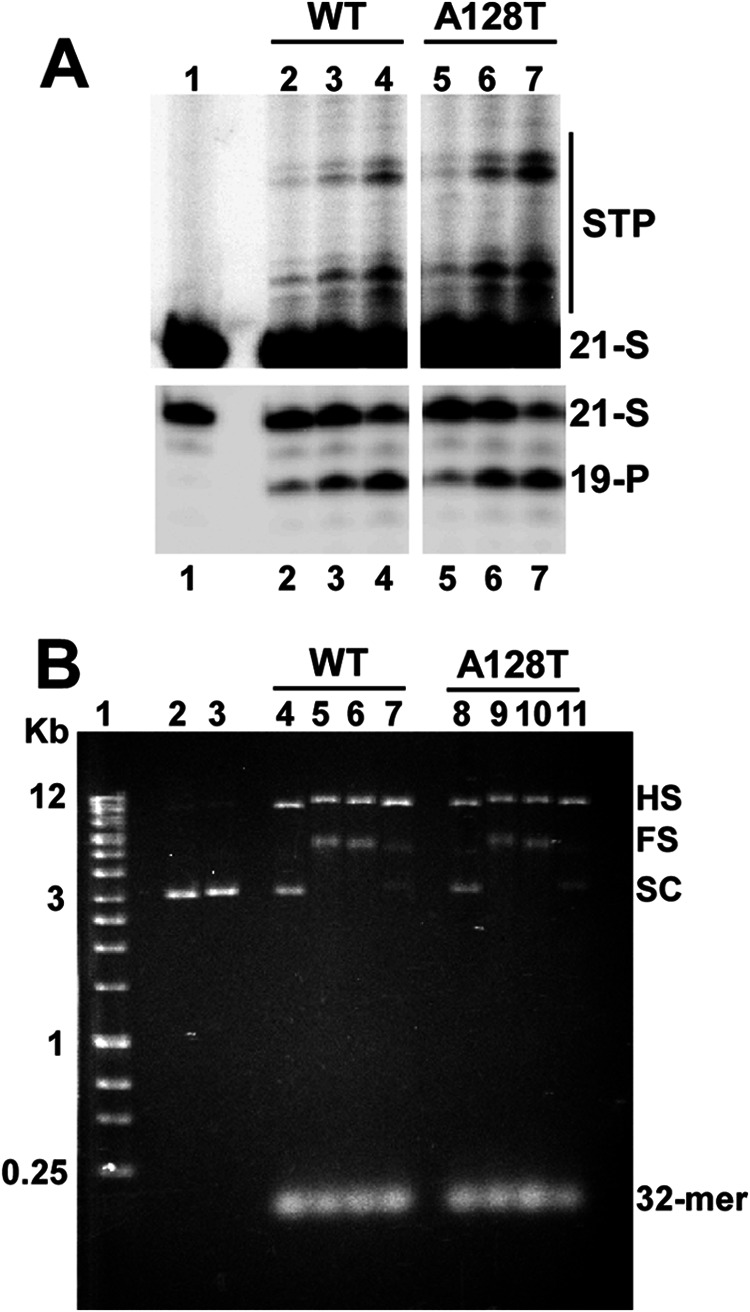

To examine the effects of the A128T substitution on HIV-1 IN function, we compared the catalytic activities of purified recombinant WT and mutant proteins. The two proteins exhibited comparable levels of LEDGF/p75-independent and LEDGF/p75-dependent integration activities (Fig. 1). Thus, the A128T substitution does not significantly alter the function of IN.

FIGURE 1.

Catalytic activities of WT and A128T INs. A, strand transfer reaction products (STP; upper panels) and 3′-processing products (19-P; lower panels). Lane 1, 21-mer DNA substrate (21-S) without IN; lanes 2–4, increasing concentrations (0.5, 1, and 2 μm) of WT IN added to the reactions; lanes 5–7, increasing concentrations (0.5, 1, and 2 μm) of A128T IN added to the reactions. B, concerted integration results. The positions of 32-mer donor and supercoiled (SC) target DNA substrates, as well as full-site (FS) and half-site (HS) integration products, are indicated. Lane 1, DNA markers (Bioline Quanti-Marker, 1 kb); lanes 2 and 3, target DNA; lane 4, WT IN (2.4 μm) added to donor and target DNA substrates without LEDGF/p75; lanes 5–7, LEDGF/p75 added with decreasing concentrations (2.4, 1.2, and 0.6 μm) of WT IN; lane 8, A128T IN (2.4 μm) added to donor and target DNA substrates without LEDGF/p75; lanes 9–11, LEDGF/p75 with decreasing concentrations (2.4, 1.2, and 0.6 μm) of A128T IN.

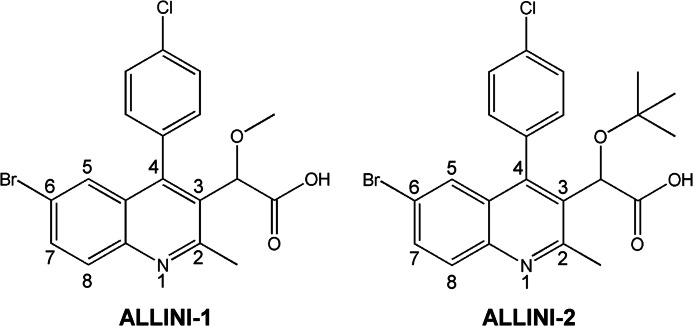

The A128T mutation has been shown to confer resistance to four different ALLINI compounds in cell culture assays (12, 15, 16, 19). To delineate the mechanism of drug resistance, the ALLINI-1 and ALLINI-2 compounds were synthesized (Fig. 2). ALLINI-1 was identified by Boehringer Ingelheim through a high-throughput screen for IN 3′-processing activity (13), and its multimodal mechanism of action has been elucidated by our group (14). In resistance studies under selective pressure of ALLINI-1 (19), the A128T substitution in IN was identified in both early and late stage viral passages. This single amino acid change resulted in 32-fold higher ALLINI-1 IC50 values compared with the WT virus. In this study, we also examined ALLINI-2, a tert-butyl derivative of ALLINI-1. Similar to a published report (16) showing that the tert-butyl group increases the potency of this class of compounds, ALLINI-2 was ∼10-fold more potent (IC50 = 0.63 ± 0.3 μm) (supplemental Table 2) than ALLIN-1 (IC50 = 5.8 ± 0.1 μm). Although we have not selected for the A128T mutation by serially passaging HIV-1 in the presence of ALLINI-2, the ability of this mutation to confer relative pan-tropic resistance to a number of different compounds, including those that harbor the tert-butyl moiety (15, 16), gave us confidence that A128T would likely confer resistance to ALLINI-2. Supplemental Table 2 indeed shows that A128T conferred 19-fold resistance to ALLINI-2 in a spreading HIV-1 replication assay.

FIGURE 2.

Chemical structures of ALLINI-1 and ALLINI-2.

We and others have shown that ALLINIs inhibit multiple functions of WT IN, including LEDGF/p75-independent catalysis and IN-IN multimerization, with similar IC50 values (14–16). Such a mechanism has been attributed to the fact that these compounds occupy the LEDGF/p75-binding pocket at the IN dimer interface. As a result, ALLINIs inhibit IN-LEDGF/p75 binding and also bridge two IN subunits and allosterically modulate their multimerization. In turn, the latter impairs the catalytic functions of WT IN.

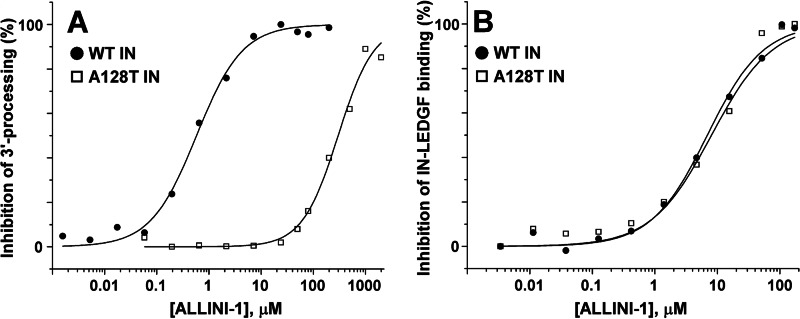

Strikingly, we observed that the A128T substitution had markedly different effects on the IC50 values for different assays in comparison with WT IN (Table 1). For example, the mutation conferred only an ∼2-fold increase in IC50 values for inhibiting the IN-LEDGF/p75 interaction, whereas the IC50 values for the 3′-processing reaction increased by 287-fold and 1112-fold for ALLINI-1 and ALLINI-2, respectively. Thus, A128T IN was markedly resistant to ALLINIs in 3′-processing reactions, whereas these compounds remained potent inhibitors of A128T IN binding to LEDGF/p75 (Fig. 3 and supplemental Fig. S3). The A128T substitution resulted in ∼11.5- and 5-fold resistance to ALLINI-1 and ALLINI-2, respectively, in the strand transfer reactions (Table 1). In LEDGF/p75-dependent integration assays, the mutant protein exhibited ∼12- and 25-fold resistance to ALLINI-1 and ALLINI-2, respectively (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Effects of the A128T substitution on the IC50 values of ALLINIs

Means ± S.E. are shown for at least three independent experiments, with -fold changes in ALLINI resistance for the mutant enzyme in parentheses.

| IC50 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IN-LEDGF binding |

3′-Processing |

Stand transfer |

LEDGF-dependent integration |

|||||

| WT | A128T | WT | A128T | WT | A128T | WT | A128T | |

| μm | ||||||||

| ALLINI-1 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 4.0 ± 0.6 (2) | 0.91 ± 0.06 | 261.5 ± 48 (287) | 0.4 ± 0.09 | 4.61 ± 0.45 (11.5) | 1.29 ± 0.34 | 15.6 ± 3.5 (12) |

| ALLINI-2 | 0.3 ± 0.02 | 0.78 ± 0.06 (2.6) | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 200.2 ± 17 (1112) | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 0.89 ± 0.19 (5) | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 1.49 ± 0.03 (25) |

FIGURE 3.

Effects of ALLINI-1 on 3′-processing activities and IN-LEDGF/p75 binding of WT and A128T INs. A, dose-response effects of ALLINI-1 on 3′-processing activities of WT (●) and A128T (□) INs. B, dose-response effects of ALLINI-1 on the IN-LEDGF/p75 binding for WT (●) and A128T (□) INs. The IC50 values and S.E. obtained from curve fittings are given in Table 1.

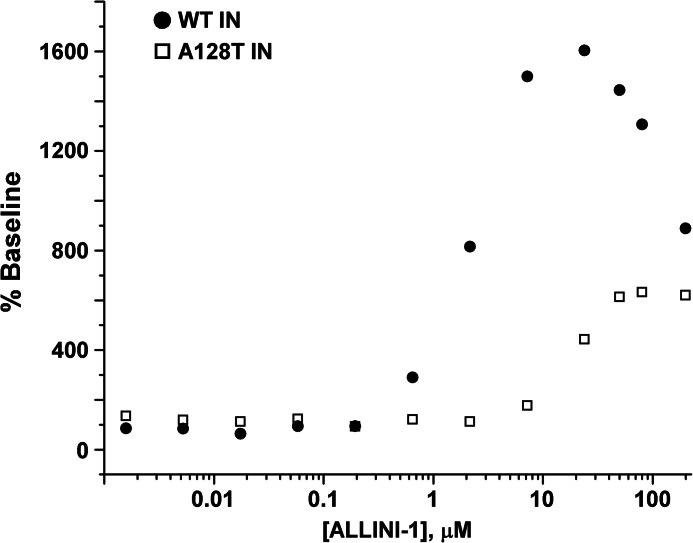

Interestingly, IN multimerization assays have revealed further striking differences between WT and mutant INs (Fig. 4 and supplemental Fig. S4). Both WT and A128T INs exhibited a characteristic biphasic dose-response curve upon the addition of ALLINIs. The HTRF signal increase with increasing concentrations of inhibitor was due to the inhibitor-induced protein multimerization, yielding higher FRET. Although the exact nature of the descending curve was not clear, it could be explained by reduced accessibility of the fluorescent antibodies to their respective tags in the context of higher order IN oligomers. The assay uses anti-His6-XL665 and anti-FLAG-europium-cryptate antibodies to monitor fluorescence energy transfer (HTRF signal) between His-IN and IN-FLAG proteins. During the initial multimerization of IN, when dimers and tetramers form, the affinity tags are sufficiently exposed to readily engage the antibodies. However, these interactions may be limited in higher order IN oligomers (see Fig. 5 and supplemental Fig. S5) due to structural hindrance of the affinity tags and could thus account for the drop in HTRF signal. Fig. 4 and supplemental Fig. S4 show that the dose-dependent addition of ALLINIs to WT and A128T INs yielded different peak heights. These differences could be explained by WT and mutant INs adopting different oligomeric states (see below) or alternative conformations in the presence of the inhibitor.

FIGURE 4.

Effects of ALLINI-1 on multimerization of WT and A128T INs. Shown are the dose-response effects of ALLINI-1-induced multimerization of WT (●) and A128T (□) INs. The HTRF signal observed due to the dynamic exchange of IN subunits in the absence of the inhibitor is considered 100% base line. The mean values of three independent experiments are shown.

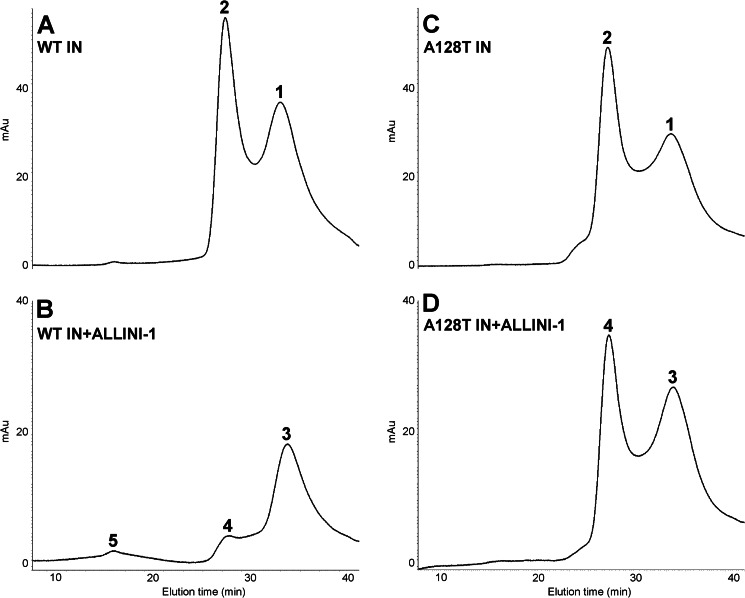

FIGURE 5.

Size exclusion chromatography demonstrating differential multimerization of WT and A128T INs in the presence of ALLINI-1. Shown are the elution profiles of 20 μm WT IN in the absence (A) and presence (B) of 80 μm ALLINI-1. The elution times and respective estimated oligomeric states for the indicated peak are summarized in supplemental Table 3. Also shown are the elution profiles of 20 μm A128T IN in the absence (C) and presence (D) of 80 μm ALLINI-1. The elution times and respective estimated oligomeric states of A128T peaks are summarized in supplemental Table 4.

To delineate between these possibilities, we performed size exclusion chromatography experiments (Fig. 5 and supplemental Fig. S5). Due to the reduced sensitivity of this approach compared with the HTRF-based assays, elevated concentrations of IN and ALLINIs were necessary. Tetramer and monomer peaks were detected with both WT and A128T INs in the absence of inhibitor, demonstrating that the substitution does not affect IN multimerization (Fig. 5 and supplemental Fig. S5) or catalytic activities (Fig. 1). Upon the addition of ALLINIs, the tetramer peak of WT IN was markedly reduced, and instead, new peaks corresponding to higher order oligomers were detected. In sharp contrast, the tetramer peak persisted upon the addition of ALLINI-1 or ALLINI-2 to A128T IN (Fig. 5 and supplemental Fig. S5 and Tables 3–6). These findings are consistent with the results of the HTRF-based multimerization assays: the formation of higher order structures upon ALLINI addition resulted in greater HTRF signal strength compared with mutant IN and could also account for the downward slope of the WT IN curves at high compound concentrations (Fig. 4 and supplemental Fig. S4).

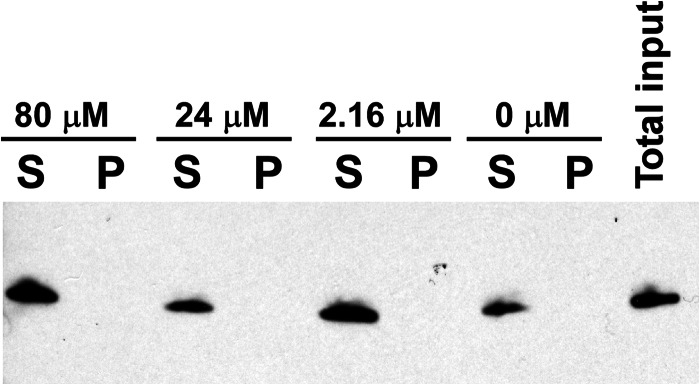

We next examined whether the addition of ALLINIs to IN might promote the formation of insoluble aggregates. WT IN was incubated with increasing concentrations of ALLINI-1 or ALLINI-2 and then subjected to centrifugation. The results in Fig. 6 and supplemental Fig. S6 show that, under our reaction conditions, the IN-ALLINI complexes remained soluble. The solubility (Fig. 6 and supplemental Fig. S6) and HTRF-based IN multimerization (Fig. 4 and supplemental Fig. S4) assays were carried out at two different NaCl concentrations (150 and 750 mm) and yielded very similar results, indicating that the changes in the ionic strength of the buffer did not significantly affect the solubility of ALLINI-induced higher order IN oligomers. This supports the notion that higher order IN multimerization and not precipitation led to the decrease in HTRF signal seen in Fig. 4 and supplemental Fig. S4.

FIGURE 6.

Solubility of the complex of WT IN and ALLINI-1. WT IN was incubated with the indicated concentrations of ALLINI-1 and then subjected to centrifugation. The supernatant (S) and pellet (P) fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and IN was detected by anti-His antibody.

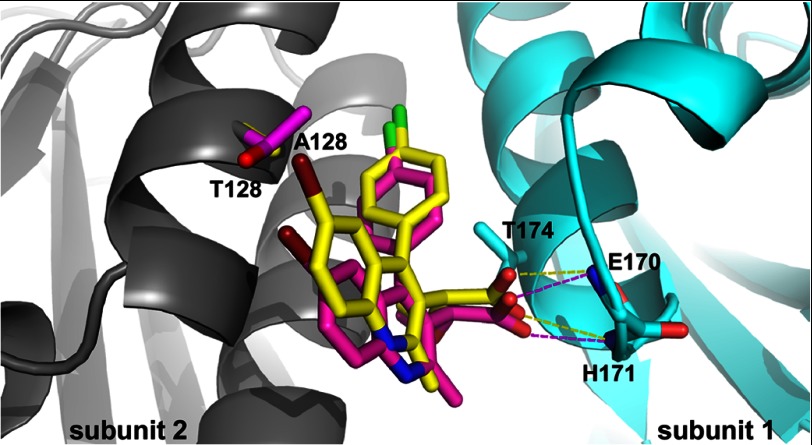

To elucidate the structural basis for how the resistance mutation affects ALLINI binding, we solved the crystal structures of the inhibitors bound to the WT and A128T IN CCDs (Fig. 7 and supplemental Fig. S7). The overlay of these two structures shows that the hydrogen bonding network between ALLINIs and subunit 1 is fully preserved in both the WT and mutant proteins (Fig. 7 and supplemental Fig. S7). These include the interactions of the carboxylic acid with the backbone amides of Glu-170 and His-171 and the methoxy group of ALLINI-2 with the side chain of Thr-174. Thus, ALLINIs effectively shield the access of the key LEDGF/p75 Asp-366 contact to its cognate hydrogen bonding partners on both WT and A128T INs. Accordingly, these compounds inhibited the binding of the cellular cofactor to WT and A128T INs with comparable IC50 values (Fig. 3 and supplemental Fig. S3).

FIGURE 7.

Overlay of crystal structures of ALLINI-1 bound to A128T and WT IN CCDs. Ala-128 and its corresponding ligand ALLINI-1 are colored yellow, whereas Thr-128 and the respective ALLINI-1 molecule are colored magenta. Hydrogen bonds between ALLINI-1 molecules and the backbones of Glu-170 and His-171 are shown by yellow (for WT IN) and magenta (for A128T IN) dashed lines. Subunits 1 and 2 are colored cyan and gray, respectively.

Interestingly, the A128T substitution affected the positioning of the quinoline group (Fig. 7 and supplemental Fig. S7). ALLINIs were shifted down and inward (toward the protein) by ∼2 Å as measured at the common bromine atom. Because the positioning of the carboxylic group remained intact, this resulted in the rotation of the rigid molecule by ∼18° (as measured by the shift of the bromine atom with respect to the C3 atom (numbering according to Fig. 2) in the quinoline ring). This change also caused the substituted phenyl group to shift downward by 0.8 Å at the chlorine atom. These structural changes could be explained by the substitution of Ala-128 with the bulkier and polar threonine, which could exert a steric effect and electronic repulsion of the compounds. The shifts of the quinoline and substituted phenyl groups that bridge the two monomers of the CCD could be the reason for the differential multimerization of WT and mutant INs.

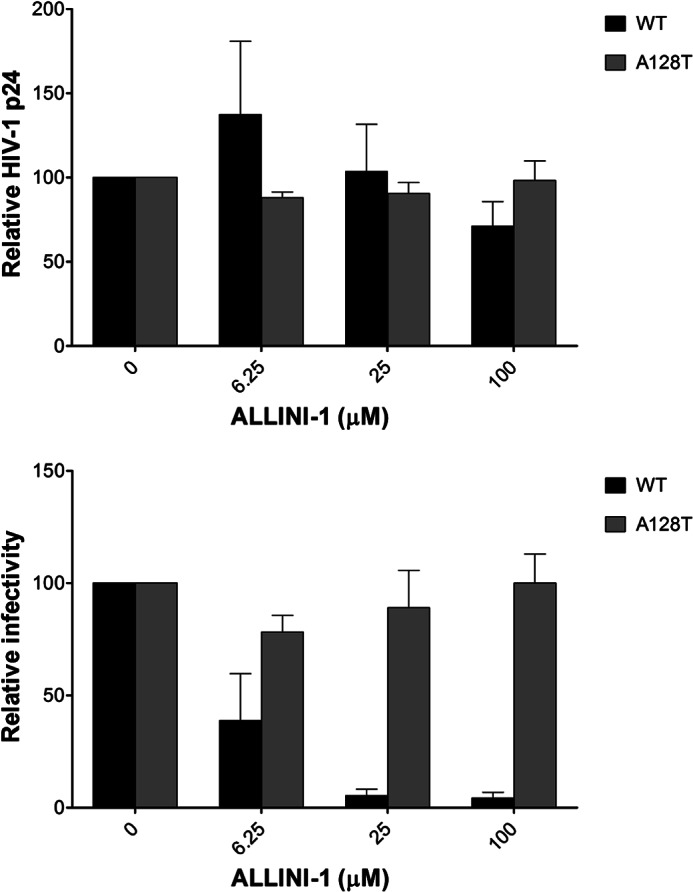

A previous study (15) demonstrated that ALLINIs do not affect bulk viral particle production but nevertheless impair the infectivity of HIV-1 progeny virions. Here, we examined how the A128T substitution affects this aspect of ALLINI inhibition (Fig. 8 and supplemental Fig. S8). For this, HEK293T cells were transfected with pNL4–3 (WT or A128T mutant) and cultured for 24 h to ensure expression of the provirus. Next, we monitored the production of HIV-1 particles in the presence of increasing concentrations of ALLINIs. Twenty-four hours post-addition of the compounds, the virus-containing cell-free supernatant was harvested, and the amounts of viral particles produced were measured by p24 ELISA. The production of both WT and A128T IN viral particles was not affected by ALLINIs (Fig. 8 (upper panel) and supplemental Fig. S8A). Subsequently, we examined the infectivity of these progeny virions in a HeLa-based reporter cell line (TZM-bl) containing the HIV-1 LTR-luciferase reporter gene. For this, TZM-bl cells were infected with equivalent cell-free virions without any additional inhibitor being added to the target cells. Under these conditions, only 0.1% of the input ALLINIs was carried over from the producer cells to the target cells based on the supernatant volumes used for the infections. At the highest concentration of ALLINIs tested (100 μm ALLINI-1 treatment of the producer cells), only 100 nm inhibitor would carry over, which is well below the IC50 value for the WT virus and thus will have negligible effects on the TZM-bl cell infections. The results in Fig. 8 (lower panel) and supplemental Fig. S8B demonstrate that WT virions produced in the presence of the inhibitors lost their infectivity, with estimated IC50 values of ∼6 μm for ALLINI-1 and ∼0.5 μm for ALLINI-2. In contrast, the A128T virions exhibited a marked resistance to ALLINIs (Fig. 8 (lower panel) and supplemental Fig. S8B). Control experiments with RAL showed no effects of this inhibitor on viral production or infectivity (data not shown).

FIGURE 8.

Effects of ALLINI-1 on WT and A128T HIV-1 p24 production and infectivity. Upper panel, HEK293T cells were transfected with either WT or A128T IN provirus. HIV-1 particles were produced in the presence or absence of ALLINI-1 for 24 h, and cell-free Gag was measured by HIV-1 p24 ELISA. Lower panel, the indicated WT or A128T IN cell-free virus equivalent to 4 ng of HIV-1 p24 was used to infect TZM-bl cells, and luciferase assay was performed at 48 h post-infection. The luciferase signal, obtained in the absence of ALLINI-1 (Me2SO alone) for WT or A128T IN, was set to 100%. The average values from at least triplicate infections are shown, and error bars represent S.D.

DISCUSSION

ALLINIs are a growing class of new anti-HIV-1 compounds. Importantly, these inhibitors are complementary to all Food and Drug Administration-approved antiretroviral agents, including the IN strand transfer inhibitors RAL and elvitegravir. Whereas the IN strand transfer inhibitors specifically interact with the IN-viral DNA complex (27), ALLINIs target a clinically unexploited IN dimer interface at the LEDGF/p75-binding site. Consequently, ALLINIs allosterically modulate IN multimerization and impair IN-LEDGF/p75 binding (14–16).

The IN A128T substitution has been identified from cell culture assays as a primary mechanism of HIV-1 resistance to numerous ALLINIs (12, 15, 16, 19). Here, we elucidated the structural and mechanistic basis for this resistance. The alanine-to-threonine substitution affects positioning of the core quinoline and substituted phenyl ring of ALLINIs that bridge the two IN subunits, whereas the hydrogen bonding network between the inhibitor and the protein that closely mimics the IN-LEDGF/p75 interaction remains intact. As a result, the A128T substitution shows marked resistance to ALLINI-induced aberrant multimerization of IN compared with its WT counterpart, whereas the compound remains a potent inhibitor of the A128T IN binding to LEDGF/p75.

We have shown that ALLINIs promote aberrant higher order multimerization of WT IN, but not A128T IN. Although previous studies have attributed the HTRF signal increase to IN dimerization (16), the size exclusion chromatography data in Fig. 5 and supplemental Fig. S5 clarify that the addition of ALLINIs to the WT protein promotes the formation of higher order oligomers. As a result, the catalytic activities of the WT protein are fully compromised. In sharp contrast, A128T IN is remarkably resistant to ALLINIs in the 3′-processing assays (287- and 1112-fold for ALLINI-1 and ALLINI-2, respectively) and exhibits 5–11-fold resistance in strand transfer assays. How does one explain the differential levels of resistance of A128T IN for 3′-processing and strand transfer activities? The HTRF assays coupled with size exclusion chromatography indicate that ALLINIs stabilize a tetrameric form of A128T IN. Of note, IN tetramers formed in the absence and presence of viral DNA adopt distinct conformations (3). Although preformed tetramers are known to be active in 3′-processing, the strand transfer reactions require individual IN monomers to assemble in the presence of viral DNA to correctly engage target DNA (3, 4). Parallels can be drawn with our earlier results demonstrating the importance of highly dynamic interplay of individual IN subunits for productive integration (3, 4). The IN tetramers stabilized by the LEDGF/p75 IN-binding domain are active in 3′-processing reactions but fail to catalyze concerted HIV-1 integration. Similarly, IN tetramers prematurely stabilized by ALLINIs are likely to be different from the fully functional tetramers in the intasome formed in the presence of DNA substrate.

To understand the 5–11-fold resistance of A128T IN in the strand transfer assays, we analyzed the HTRF data in Fig. 4 and supplemental Fig. S4. Accurate measurements of ALLINI IC50 values from these assays were complicated due to biphasic curves and differing peak heights for WT and A128T INs. Still, the analysis of the initial ascending curves enabled us to estimate the IC50 values for WT versus A128T IN: 2.27 ± 0.13 μm versus 17.81 ± 1.46 μm for ALLINI-1 and 0.070 ± 0.008 μm versus 0.68 ± 0.06 μm for ALLINI-2. The ∼10-fold increase in estimated IC50 values for the initial multimerization phase for A128T IN compared with its WT counterpart could explain the observed resistance of mutant IN in the strand transfer assays (Table 1).

The differential multimerization of WT and A128T INs induced by ALLINIs correlates with the differences in infectivity of HIV-1 progeny virions. The treatment of producer cells with the inhibitors impairs WT HIV-1 infectivity, with estimated IC50 values of ∼6 μm for ALLINI-1 and ∼0.6 μm for ALLINI-2, whereas A128T HIV-1 exhibits marked resistance to these compounds (Fig. 8 and supplemental Fig. S8). In turn, these results correlate well with the inhibitory activities of these compounds with respect to WT and A128T HIV-1 replication in spreading assays (supplemental Table 2) (14).

In conclusion, our findings that the A128T substitution did not significantly alter ALLINI IC50 values for IN-LEDGF/p75 binding but substantially affected IN multimerization in the presence of the inhibitors indicate that allosteric IN oligomerization is the primary target of these inhibitors in infected cells. Our structural data showing that the A128T substitution repositions the quinoline ring of ALLINIs at the IN dimer interface provide a path for rationale development of second-generation ALLINI compounds with decreased potential to select for drug resistance.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants AI081581 and AI062520 (to M. K.), GM103368 (to A. E. and M. K.), AI097044 (to J. J. K. and J. R. F.).

This article contains supplemental “Experimental Procedures,” Figs. S1–S8, Tables 1–6, and additional references.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 4JLH, 4GW6, and 4GVM) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

- IN

- integrase

- LEDGF

- lens epithelium-derived growth factor

- CCD

- catalytic core domain

- ALLINI

- allosteric IN inhibitor

- RAL

- raltegravir

- HTRF

- homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence.

REFERENCES

- 1. Johnson A. A., Marchand C., Pommier Y. (2004) HIV-1 integrase inhibitors: a decade of research and two drugs in clinical trial. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 4, 1059–1077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brown P. O. (1997) Integration. in Retroviruses (Coffin J. M., Hughes S. H., Varmus H. E. eds) pp. 161–204, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Plainview, NY [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kessl J. J., Li M., Ignatov M., Shkriabai N., Eidahl J. O., Feng L., Musier-Forsyth K., Craigie R., Kvaratskhelia M. (2011) FRET analysis reveals distinct conformations of IN tetramers in the presence of viral DNA or LEDGF/p75. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 9009–9022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McKee C. J., Kessl J. J., Shkriabai N., Dar M. J., Engelman A., Kvaratskhelia M. (2008) Dynamic modulation of HIV-1 integrase structure and function by cellular lens epithelium-derived growth factor (LEDGF) protein. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 31802–31812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Li M., Mizuuchi M., Burke T. R., Jr., Craigie R. (2006) Retroviral DNA integration: reaction pathway and critical intermediates. EMBO J. 25, 1295–1304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kessl J. J., Eidahl J. O., Shkriabai N., Zhao Z., McKee C. J., Hess S., Burke T. R., Jr., Kvaratskhelia M. (2009) An allosteric mechanism for inhibiting HIV-1 integrase with a small molecule. Mol. Pharmacol. 76, 824–832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Raghavendra N. K., Engelman A. (2007) LEDGF/p75 interferes with the formation of synaptic nucleoprotein complexes that catalyze full-site HIV-1 DNA integration in vitro: implications for the mechanism of viral cDNA integration. Virology 360, 1–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maertens G., Cherepanov P., Pluymers W., Busschots K., De Clercq E., Debyser Z., Engelborghs Y. (2003) LEDGF/p75 is essential for nuclear and chromosomal targeting of HIV-1 integrase in human cells. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 33528–33539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cherepanov P., Devroe E., Silver P. A., Engelman A. (2004) Identification of an evolutionarily conserved domain in human lens epithelium-derived growth factor/transcriptional co-activator p75 (LEDGF/p75) that binds HIV-1 integrase. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 48883–48892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hare S., Shun M. C., Gupta S. S., Valkov E., Engelman A., Cherepanov P. (2009) A novel co-crystal structure affords the design of gain-of-function lentiviral integrase mutants in the presence of modified PSIP1/LEDGF/p75. PLoS Pathog. 5, e1000259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cherepanov P., Ambrosio A. L., Rahman S., Ellenberger T., Engelman A. (2005) Structural basis for the recognition between HIV-1 integrase and transcriptional coactivator p75. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 17308–17313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Christ F., Voet A., Marchand A., Nicolet S., Desimmie B. A., Marchand D., Bardiot D., Van der Veken N. J., Van Remoortel B., Strelkov S. V., De Maeyer M., Chaltin P., Debyser Z. (2010) Rational design of small-molecule inhibitors of the LEDGF/p75-integrase interaction and HIV replication. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6, 442–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tsantrizos Y. S., Boes M., Brochu C., Fenwick C., Malenfant E., Mason S., Pesant M. (November 22, 2007) Inhibitors of human immunodeficiency virus replication. International Patent PCT/CA2007/000845

- 14. Kessl J. J., Jena N., Koh Y., Taskent-Sezgin H., Slaughter A., Feng L., de Silva S., Wu L., Le Grice S. F., Engelman A., Fuchs J. R., Kvaratskhelia M. (2012) A multimode, cooperative mechanism of action of allosteric HIV-1 integrase inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 16801–16811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Christ F., Shaw S., Demeulemeester J., Desimmie B. A., Marchand A., Butler S., Smets W., Chaltin P., Westby M., Debyser Z., Pickford C. (2012) Small-molecule inhibitors of the LEDGF/p75 binding site of integrase block HIV replication and modulate integrase multimerization. Antimicrob. agents Chemother. 56, 4365–4374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tsiang M., Jones G. S., Niedziela-Majka A., Kan E., Lansdon E. B., Huang W., Hung M., Samuel D., Novikov N., Xu Y., Mitchell M., Guo H., Babaoglu K., Liu X., Geleziunas R., Sakowicz R. (2012) New class of HIV-1 integrase (IN) inhibitors with a dual mode of action. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 21189–21203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shen L., Rabi S. A., Siliciano R. F. (2009) A novel method for determining the inhibitory potential of anti-HIV drugs. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 30, 610–616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shen L., Peterson S., Sedaghat A. R., McMahon M. A., Callender M., Zhang H., Zhou Y., Pitt E., Anderson K. S., Acosta E. P., Siliciano R. F. (2008) Dose-response curve slope sets class-specific limits on inhibitory potential of anti-HIV drugs. Nat. Med. 14, 762–766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fenwick C. W., Tremblay S., Wardrop E., Bethell R., Coulomb R., Elston R., Faucher A.-M., Mason S., Simoneau B., Tsantrizos Y., Yoakim C. (2011) Resistance studies with HIV-1 non-catalytic site integrase inhibitors. International Workshop on HIV and Hepatitis Virus Drug Resistance and Curative Strategies, Los Cabos, Mexico, June 7–11, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dyda F., Hickman A. B., Jenkins T. M., Engelman A., Craigie R., Davies D. R. (1994) Crystal structure of the catalytic domain of HIV-1 integrase: similarity to other polynucleotidyl transferases. Science 266, 1981–1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Otwinowski Z., Minor W. (1997) Processing of x-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McCoy A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Adams P. D., Winn M. D., Storoni L. C., Read R. J. (2007) Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 658–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 (1994) The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 50, 760–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Emsley P., Lohkamp B., Scott W. G., Cowtan K. (2010) Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 486–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A., Dodson E. J. (1997) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53, 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Painter J., Merritt E. A. (2006) Optimal description of a protein structure in terms of multiple groups undergoing TLS motion. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 62, 439–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hare S., Gupta S. S., Valkov E., Engelman A., Cherepanov P. (2010) Retroviral intasome assembly and inhibition of DNA strand transfer. Nature 464, 232–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.