Previous studies have identified a mixed-phenotype of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with co-existing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Although NSCLC and COPD share a common risk factor in smoking, whether and how smoking may contribute to the coexistence of NSCLC with COPD (NSCLC-COPD) is unclear. The present study suggests that cigarette smoking is the major risk factor for the development of NSCLC-COPD, especially in females and amongpatients with squamous cell carcinoma subtype.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is an established risk factor for lung cancer (LC), resulting in a mixed-phenotype of LC with the coexistence of COPD (LC-COPD). Although cigarette smoking has been associated with COPD and LC, it is unclear whether and to what extent smoking may contribute to LC-COPD. We examined the association between smoking and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with COPD (NSCLC-COPD) in 3862 patients with NSCLC and 1646 healthy controls (without LC and COPD). Logistic regression was used to calculate odds ratios (ORs), adjusting for covariates. In 3862 patients with NSCLC, there were 999 cases with physician-diagnosed COPD (NSCLC-COPD). Compared with never-smokers, the ORs for NSCLC-COPD in ex-smokers and current-smokers were 10.76 (95%CI, 7.32–15.81; p<0.0001) and 45.02 (95%CI, 29.75–68.13, p<0.001), respectively; whereas the corresponding ORs for NSCLC-NO-COPD were only 2.05 (95%CI, 1.75–2.40; p<0.0001) and 4.17 (95%CI, 3.45–5.03; p<0.001), respectively. ORs for NSCLC-COPD were also higher than that for NSCLC-NO-COPD for all categories of smoking pack-years. Associations of smoking with NSCLC-COPD were stronger in females than in males, and in patients with squamous cell carcinoma than in adenocarcinoma. Cubic spline analyses showed that the risk of NSCLC-COPD increased nonlinearly with smoking dosages. In contrast, quitting smoking significantly reduced the risk of NSCLC-COPD. In summary, cigarette smoking is the most important cause of NSCLC-COPD. Smoking intensity exerts a stronger effect on NSCLC-COPD in females than in males, and in squamous cell carcinoma than in adenocarcinoma.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and lung cancer (LC) are lung disorders that primarily result from the effects of smoking exposure, with almost 90% of LC and COPD cases attributable to cigarette smoking.1–2 Importantly, COPD and LC are the fourth and the seventh leading causes of deaths in the world, accounting for approximately 3 million and 1 million deaths per year, respectively.3

Although COPD and LC are different at the clinical, cellular and molecular levels, COPD has been recognized to be a major risk factor for LC, a risk that is independent of age and smoking dosage.4–5,50 Smokers with COPD may have up to 4–6 fold-increased risk of developing LC when compared with smokers without COPD.6–7 In fact, multiple studies have shown that approximately 50%-70% of patients with LC have co-existing impaired lung function or COPD.5,8–9 These observations suggest the existence of a mixed phenotype of LC that includes co-existing COPD and LC as a sub-phenotype.10 Given the large proportion of coexisting COPD among LC cases, if considered as a separate category, the mixed phenotype of lung cancer with COPD (LC-COPD) would rank as one of the most common causes of cancer death worldwide. To date, however, most studies of COPD and LC have been done independently of each other, only a few have specifically targeted mixed LC-COPD phenotype.10–12 While much has been learnt on the etiologies of COPD and LC, little is known about the risk factors for LC-COPD.

Since smoking is causally associated with COPD and LC, it appears plausible that smoking may also be relevant to the development of LC-COPD. However, it has been observed that LC risk remains increased in patients with COPDafter quitting smoking.13 Even in individuals who never smoked, decreased lung function and COPD was also directly associated with the development of LC.4,14 It is therefore unclear to what extent smoking may contribute to the LC-COPD risk. The aim of this study was to assess the magnitude of the risk of LC-COPD in relation to smoking status, smoking dosage (pack-years), and smoking cessation. We focused our analysis on non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with COPD since NSCLC accounts for ~80% of LC cases worldwide. We also tested the hypothesis that effect of smoking on the risk of NSCLC-COPD may be related to tumor histologic subtype and gender.

Material and Methods

Study population

This study included 3862 NSCLC cases and 1646 healthy subjects, recruited from Boston at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) since 1991. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of MGH, DFCI, and the Harvard School of Public Health. Details of the study population have been previously reported.15–16 Briefly, patients (>18 years old) with pathologically confirmed newly diagnosed NSCLCwere consecutively recruited at the MGH in Boston, MA. Controls were recruited at MGH from healthy friends and non-blood-related family members (usually spouses) of several groups of hospital patients: (a) patients with cancer, whether related or not related to a case; or (b) patients with a cardiothoracic condition undergoing surgery. Potential controls who carried a previous diagnosis of any cancer (other than non-melanoma skin cancer) were excluded from participation. Over 85% of eligible subjects were recruited and informed consent was obtained from each subject or their surrogates. Demographic and clinicopathologic information (including age, gender, smoking status and intensity, and medical history) were collected by research nurses at the time of recruitment.

For both cases and controls, smoking status was defined as never-, ex- and current smokers. Smoking intensity was computed as pack-years (defined as the number of cigarettes smoked per day divided by 20 and multiplied by the number of years smoked). Smoking habits were defined at 1 year prior to diagnosis for cases, or 1 year prior to interview for controls. Never-smokers was defined as individuals who had smoked fewer than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime; former smokers were subjects who had quit smoking for more than 12 months; current smokers were those who were currently smoking or had quit during the past 12 months; and ever smokers were individuals who were either former or current smokers.17 The baseline questionnaire listed chronic bronchitis, emphysema, and/or COPD, and other lung disorders (asthma, tuberculosis,..). All cases and controls were asked to self-report whether a physician had ever diagnosed them with chronic bronchitis, emphysema, or COPD, categorized as present or absent. Subjects who had physician-diagnosed chronic bronchitis, emphysema, and/or COPD were defined as having COPD.4, 18–20 Subjects who had other lung disorders were excluded from the study.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic and clinical information between cases and controls, and between NSCLC-COPD and NSCLC-NO-COPD was compared using chi-square tests for categorical variables and by the Student t test or the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables, where appropriate. Smoking-related odds ratios (ORs), and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using unconditional logistic regression models, adjusting for age and gender. Trend tests were performed with categorized smoking levels (1-<20, 20-<40, 40-<60, and ≥60 pack years), using never smokers as the reference group; and with categorized years since quitting smoking (5-<10, 10-<15, 15-<20, ≥20 years), and using subjects with <5 years smoking cessation as the reference group. Analyses were performedon case status (NSCLC versus control), and on COPD status (NSCLC-COPD versus NSCLC-NO-COPD). In addition to the overall association analysis, we performed stratified analyses by gender and histology to further explore the association between smoking and the risk NSCLC-COPD in each stratum. All reported p-values are based on two-sided tests. P-values<0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analysis were done using SAS software version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

We also investigated the relationship between smoking and NSCLC-COPD using cubic spline models to plot the dose-response relationship on a continuous scale. This approach helps to eliminate the assumption of linearity to evaluate the functional form of the dose risk curve.21 Restricted cubic spline models allow for easy visualization of non-linear relationships between an exposure and an outcome,22 in this case, smoking and NSCLC-COPD. These analyses used never-smoking (pack-year = 0) as reference and adjusted for age (continuous) and gender (categorical). Plots were constructed for overall subgroups and also for stratified subgroups.

Results

Characteristics of cases and controls

A total of 3862 NSCLC cases and 1646 controls were included in the analysis. Table 1 shows the basic characteristics for cases and controls. The cases averaged 65 years of age at interview compared to 58 years for the controls. Smoking exposure variables (ever- and current-smokers, pack years, and years of quitting smoking) in NSCLC cases were significantly higher than that of controls.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

| Characteristics | Controls | NSCLC cases | P value1 | P value2 | P value3 | P value4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ( n = 1646) | All cases (n = 3862) |

NSCLC-COPD (n = 999) |

NSCLC-NO- COPD(n = 2863) |

||||||

| Age, mean ± SD | 58.3 ± 11.9 | 65.2 ± 11.0 | 66.3 ± 10.1 | 64.7 ± 11.2 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0002 | |

| Gender, n (%) | |||||||||

| Male | 739 (44.9%) | 1879 (48.7%) | 448 (44.8%) | 1418 (49.5%) | 0.01 | 0.53 | 0.003 | 0.07 | |

| Female | 907 (55.1%) | 1983 (51.4%) | 551 (55.2%) | 1445 (50.5%) | |||||

| Histologic cell type | |||||||||

| ADC | 1865 (48.3%) | 428 (42.8%) | 1437 (50.2%) | <0.0001 | |||||

| SQCC | 774 (20.0%) | 264 (26.4%) | 510 (17.8%) | ||||||

| Others | 1223 (31.7%) | 307(30.7%) | 916 (32.0%) | ||||||

| Smoking status | |||||||||

| Never | 611 (36.1%) | 494 (12.8%) | 32 (3.2%) | 462 (16.1%) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| Ex-smokers | 760 (46.2%) | 2085 (54.0%) | 530 (53.1%) | 1555 (54.3%) | |||||

| Current smokers | 292 (17.7%) | 1283 (33.2%) | 437 (43.7%) | 846 (29.6%) | |||||

| Pack-years | |||||||||

| 0 | 594 (36.1%) | 494 (12.8%) | 32 (3.2%) | 462 (16.1%) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| 1–<20 | 474 (28.8%) | 568 (14.7%) | 71 (7.1%) | 497 (17.3%) | |||||

| 20–<40 | 304 (18.5%) | 872 (22.6%) | 220 (22.0%) | 652 (22.8%) | |||||

| 40–<60 | 155 (9.4%) | 900 (23.3%) | 305 (30.5%) | 595 (20.8%) | |||||

| ≥60 | 119 (7.2%) | 1028 (26.6%) | 371 (37.1%) | 657 (23.0%) | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 18.5 ± 24.7 | 44.2 ± 36.5 | 57.0 ± 35.6 | 39.7 ± 36.7 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| Years since quitting smoking5 | (n = 760) | (n = 2845) | (n = 618) | n = 1555) | |||||

| <5 | 77 (10.2%) | 385 (18.5%) | 125 (23.6%) | 260 (16.7%) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0004 | |

| 5–<10 | 87 (11.5%) | 333 (16.0%) | 114 (21.5%) | 219 (14.1%) | |||||

| 10–<15 | 119 (15.7%) | 327 (15.7%) | 92 (17.4%) | 235 (15.1%) | |||||

| 15–<20 | 106 (14.0%) | 273 (13.1%) | 67 (12.6%) | 206 (13.3%) | |||||

| ≥20 | 371 (48.8%) | 767 (36.8%) | 132 (24.9%) | 635 (40.8%) | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 20.2 ± 12.2 | 17.0 ± 12.4 | 13.7 ± 10.9 | 18.1 ± 12.6 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

P value comparing controls vs. total NSCNSCLC cases;

P value comparing controls vs.NSCLC- COPD;

P value comparing controls vs.NSCLC-NO-COPD;

P value comparing NSCLC-COPD vs. NSCLC-NO-COPD;

Among ex-smokers; ADC: Adenocarcinoma; SQCC: Squamous cell carcinoma.

Among patients with NSCLC, we documented 999 cases with COPD (NSCLC-COPD) and 2863 cases without COPD (NSCLC-NO-COPD). The mean age (66.3 ± 10.1) of cases with NSCLC-COPD was significantly (p<0.0001) higher than that of NSCLC-NO-COPD patients (64.7 ± 11.2). The proportion of COPD-NSCLC patients who had never smoked was 3.2% as compared with 16.1% in NSCLC-NO-COPD. Smoking intensity in COPD-NSCLC cases (57.0 ± 35.6 pack years) was significantly (p<0.0001) higher than that in NSCLC-NO-COPD patients (39.7 ± 36.7 pack years). Patients with NSCLC-COPD also had shorter (p<0.0001) years of quitting smoking (13.7 ± 10.9 years) than that in patients of NSCLC-NO-COPD (18.1 ± 12.6 years).

Association of smoking status with the risk of NSCLC-COPD

Table 2 shows the relative risk estimates for various measures of exposure to cigarette smoking. Compared with never smokers, the overall odds ratios for NSCLC were 2.49 for ex-smokers (95%CI, 2.13–2.91; p<0.0001) and 5.89 for current smokers (95% CI, 4.90–7.01; p<0.0001). Restriction of analyses to NSCLC-NO-COPD vs. controls showed very similar risk estimates. But comparison analysis betweenNSCLC-COPD vs. controls gave much higher ORs, resulting an OR of 10.76 (95% CI, 7.32–15.81; p<0.0001) for ex-smokers and an OR of 45.02 (95%CI, 29.75–68.13; p<0.0001) for current smokers.

Table 2.

Associations of smoking with risk of developing NSCNSCLC by COPD

| Variables | All NSCLC cases (n = 3862) vs. controls (n = 1646) |

NSCLC-NO-COPD (n = 2863) vs. controls (n = 1646) |

NSCLC-COPD (n = 999) vs. controls (n = 1646) |

NSCLC-COPD (n = 999) vs. NSCLC-NO-COPD (n = 2863) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | P value1 | OR (95%CI) | P value1 | OR (95%CI) | P value1 | OR (95%CI) | P value1 | ||

| Smoking status | |||||||||

| Never | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||||

| Ex-smokers | 2.49 (2.13–2.91) | <0.0001 | 2.05 (1.75–2.40) | <0.0001 | 10.76 (7.32–15.81) | <0.0001 | 4.69 (3.22–6.81) | <0.0001 | |

| Current -smokers | 5.89 (4.90–7.01) | <0.0001 | 4.17 (3.45–5.03) | <0.0001 | 45.02 (29.75–68.13) | <0.0001 | 7.92 (5.43–11.57) | <0.0001 | |

| Pack-years | |||||||||

| 0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||||

| 1–<20 | 1.43 (1.20–1.71) | <0.0001 | 1.34 (1.12–1.61) | 0.0015 | 2.90 (1.87–4.51) | <0.0001 | 2.07 (1.34–3.20) | 0.001 | |

| 20–<40 | 3.24 (2.71–3.90) | <0.0001 | 2.56 (2.12–3.08) | <0.0001 | 13.90 (9.23–20.82) | <0.0001 | 5.03 (3.40–7.43) | <0.0001 | |

| 40–<60 | 5.99 (4.84–7.41) | <0.0001 | 4.27 (3.43–5.32) | <0.0001 | 32.92 (21.78–82.18) | <0.0001 | 7.70 (5.23–11.33) | <0.001 | |

| ≥60 | 8.75 (6.94–11.02) | <0.0001 | 5.81 (4.59–7.37) | <0.0001 | 53.78 (35.20–82.18) | <0.0001 | 8.87 (6.04–13.03) | <0.0001 | |

| Trend | 1.78 (1.70–1.88) | <0.0001 | 1.60 (1.52–1.69) | <0.0001 | 2.72 (2.51–2.96) | <0.0001 | 1.61 (1.51–1.72) | <0.0001 | |

| Years since quitting smoking# | |||||||||

| <5 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||||

| 5–<10 | 0.68 (0.47–0.97) | <0.0001 | 0.69 (0.47–1.003) | 0.052 | 0.72 (0.45–1.15) | 0.14 | 1.00 (0.73–1.38) | 0.97 | |

| 10–<15 | 0.42 (0.30–0.59) | <0.0001 | 0.48 (0.33–0.68) | <0.0001 | 0.32 (0.20–0.51) | <0.0001 | 0.73 (0.52–1.01) | 0.058 | |

| 15–<20 | 0.37 (0.26–0.53) | <0.0001 | 0.44 (0.30–0.63) | <0.0001 | 0.24 (0.15–0.40) | <0.0001 | 0.57 (0.40–0.82) | 0.002 | |

| ≥20 | 0.22 (0.16–0.30) | <0.0001 | 0.29 (0.21–0.40) | <0.0001 | 0.08 (0.06–0.13) | <0.0001 | 0.33 (0.25–0.45) | <0.0001 | |

| Trend | 0.69 (0.65–0.74) | <0.0001 | 0.75 (0,70–0,80) | <0.0001 | 0.53 (0.48–0.59) | <0.0001 | 0.74 (0.70–0.80) | <0.0001 | |

Adjusted for age, gender;

among ex-smokers.

When subjects were stratified by gender, ex-smoking of cigarette was associated with an OR for NSCLC-NO-COPD of 2.25 (95% CI, 1.77–2.87; p< 0.0001) in men and 1.99 (95% CI, 1.61–2.46) in women. The ORs for NSCLC-NO-COPD in current smokers were 5.26 (95%CI, 3.91–7.07; p< 0.0001) for males and 3.58 (95%CI, 2.80–4.58; p< 0.0001) for female, respectively. Similar but stronger trends of association were observed between smoking status and NSCLC-COPD. Specifically, ex-smoking conferred ORs of 10.24 (95%CI, 5.50–18.99; p< 0.0001) in men and 11.60 (95%CI, 7.07–19.03; p< 0.0001) for NSCLC-COPD and in women, respectively. The ORs of NSCLC-COPD were 52.43 (95%CI, 26.73–102.85; p< 0.0001) for male current smokers and 40.41 (95%CI, 23.89–68.37; p< 0.0001) for female current smokers.

Association of smoking intensity with the risk of NSCLC-COPD

Table 2~4 summarize the ORs for NSCLC-COPD according to smoking exposure levels. Separate ORs were given for NSCLC with or without COPD, for genders, and for different histologic types. Overall, cumulative smoking intensity (pack years) was significantly associated with increased risk of both NSCLC-COPD and NSCLC-NO-COPD in a dose-response manner, but this association was considerably stronger for NSCLC-COPD than for NSCLC-NO-COPD. Specifically, heavy smokers (pack years ≥60) showed a 53.8-fold increase in NSCLC-COPD risk compared to an OR of 5.8 for NSCLC-NO-COPD risk. There were no remarkable gender difference in the association of smoking with risk of NSCLC-NO-COPD by smoking exposure levels, but ORs of smoking levels for NSCLC-COPD in females were generally higher than that in male smokers. ORs were systematically higher for squamous cell carcinoma (SQCC) than that for adenocarcinoma (ADC) for both NSCLC with and without COPD, but ORs were generally higher for NSCLC-COPD than for NSCLC-NO-COPD by cell type. In particular, heavy smokers (pack years ≥60) had 172.2-fold increase in SQCC-COPD risk compared to an OR of 30.8 for SQCC-NO-COPD.

Table 4.

Associations of smoking with risk of developing NSCNSCLC by COPD and major subtypes

| NSCLC-NO-COPD (n = 2865) vs. controls (n = 1646) | NSCLC-COPD (n = 999) vs. controls (n = 1646) | NSCLC-COPD (n = 999) vs. NSCLC-NO-COPD (n = 2865) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | ADC | SQCC | ADC | SQCC | ADC | SQCC | |||||||

| OR* (95%CI) | P* | OR* (95%CI) | P* | OR# (95%CI) | P* | OR# (95%CI) | P* | OR# (95%CI) | P* | OR# (95%CI) | P* | ||

| Smoking status | |||||||||||||

| Never | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||||||

| Ex-smokers | 1.79 (1.50–2.15) | <0.0001 | 7.59 (4.91–11.74) | <0.0001 | 8.12 (5.00–13.25) | <0.0001 | 33.16 (10.60–107.97) | <0.0001 | 3.65 (2.25–5.93) | <0.0001 | 12.05 (3.82–38.08) | <0.0001 | |

| Current -smokers | 3.27 (2.63–4.07) | <0.0001 | 27.54 (17.22–44.05) | <0.0001 | 34.54 (20.64–57.81) | <0.0001 | 175.1 (55.58–572.6) | <0.0001 | 5.89 (3.62–9.58) | <0.0001 | 21.39 (6.74–67.90) | <0.0001 | |

| Pack-years | |||||||||||||

| 0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||||||

| 1–<20 | 1.27 (1.03–1.57) | 0.02 | 2.87 (1.75–4.72) | <0.0001 | 2.59 (1.47–4.58) | 0.001 | 5.87 (1.65–20.86) | 0.006 | 1.75 (0.98–3.11) | 0.056 | 3.35 (0.93–12.10) | 0.065 | |

| 20–<40 | 2.18 (1.76–2.70) | <0.0001 | 8.68 (5.47–13.77) | <0.0001 | 12.10 (7.25–20.20) | <0.0001 | 29.58 (9.05–96.65) | <0.0001 | 4.46 (2.69–7.37) | <0.0001 | 10.17 (3.13–32.95) | <0.0001 | |

| 40–<60 | 3.38 (2.64–4.32) | <0.0001 | 17.82 (11.15–28.49) | <0.0001 | 27.13 (16.15–45.55) | <0.0001 | 106.0 (32.88–341.8) | <0.0001 | 5.92 (3.58–9.77) | <0.0001 | 19.93 (6.25–63.57) | <0.0001 | |

| ≥60 | 4.08 (3.13–5.32) | <0.0001 | 30.81 (19.29–49.21) | <0.0001 | 38.32 (22.55–65.13) | <0.0001 | 172.2 (53.40–555.0) | <0.0001 | 6.49 (3.92–1.073) | 0.043 | 25.33 (7.98–80.42) | <0.0001 | |

| trend | 1.46 (1.38–1.55) | <0.0001 | 2.30 (2.10–2.51) | <0.0001 | 2.50 (2.26–2.76) | <0.0001 | 3.07 (2.68–3.51) | <0.0001 | 1.51 (1.39–1.65) | <0.0001 | 1.84 (1.63–2.09) | <0.0001 | |

| Years since quitting smoking# | |||||||||||||

| <5 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||||||

| 5–<10 | 0.73 (0.48–1.11) | 0.14 | 0.71 (0.41–1.23) | 0.22 | 0.71 (0.40–1.26) | 0.23 | 0.65 (0.34–1.25) | 0.20 | 0.93 (0.60–1.45) | 0.757 | 0.94 (0.58–1.53) | 0.799 | |

| 10–<15 | 0.50 (0.34–0.75) | 0.0009 | 0.48 (0.29–0.81) | 0.006 | 0.35 (0.20–0.61) | 0.0003 | 0.28 (0.15–0.55) | <0.0002 | 0.67 (0.42–1.07) | 0.094 | 0.59 (0.34–1.01) | 0.053 | |

| 15–<20 | 0.46 (0.30–0.70) | 0.0003 | 0.29 (0.16–0.51) | <0.0001 | 0.25 (0.14–0.47) | <0.0001 | 0.16 (0.08–0.33) | <0.0001 | 0.52 (0.31–0.87) | 0.013 | 0.40 (0.22–0.73) | 0.003 | |

| ≥20 | 0.35 (0.25–0.49) | <0.0001 | 0.12 (0.07–0.19) | <0.0001 | 0.12 (0.07–0.20) | <0.0001 | 0.05 (0.02–0.09) | <0.0001 | 0.40 (0.26–0.60) | <0.0001 | 0.19 (0.11–0.31) | <0.0001 | |

| trend | 0.78 (0.72–0.84) | <0.0001 | 0.57 (0.51–0.64) | <0.0001 | 0.58 (0.52–0.65) | <0.0001 | 0.46 (0.40–0.54) | <0.0001 | 0.78 (0.71–0.86) | <0.0001 | 0.66 (0.58–0.74) | <0.0001 | |

Adjusted for age and gender;

among ex-smokers; ADC: Adenocarcinoma; SQCC: Squamous cell carcinoma

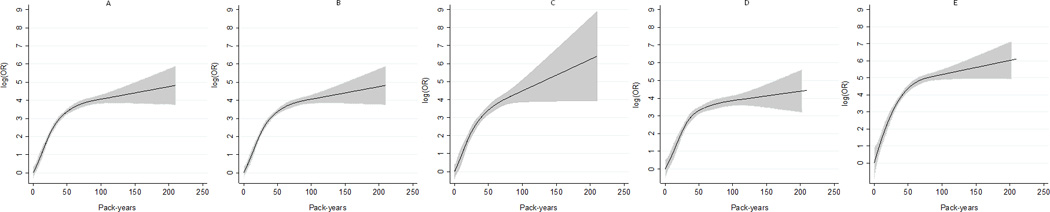

The use of non-parametric cubic spline models showed similar trends of association of smoking intensity with NSCLC, and stronger associations were also observed for NSCLC-COPD and SQCC-COPD than for NSCLC-NO-COPD and ADC-COPD, respectively.Interestingly, these associations rose steeply and tended to plateau from 50 pack years (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The dose-response analysis between smoking (pack-years) and risks of NSCLC-COPD, NSCLC-COPD in males, NSCLC-COPD in females, ADC-COPD, and SQCC-COPD, with cubic spline models. The solid line and the grey area represent the estimated relative risk (log OR) and it’s 95% confidence interval of the nonlinear relationship, respectively.

Cessation of cigarette smoking and risk reduction of NSCLC-COPD

A decline of OR for NSCLC-COPD following cessation of smoking was observed as soon as 5 years after cessation. Compared with subjects who had quit smoking for less than 5 years, the ORs were 0.72 (95%CI, 0.45–1.15; p= 0.14) for those who had quit for 5≤10 years; 0.32 (95%CI, 0.20–0.51; p< 0.0001) for those who had quit for 10≤15 years; 0.24 (95% CI, 0.15–0.40; p<0.0001) for those who had quit for 15≤20 years; and 0.08 (95%CI, 0.06–0.13; p< 0.0001) for those who had quit for more than 20 years. This trend of risk decline was stronger than that of NSCLC-NO-COPD. Similar trends of risk reduction were also observed in overall NSCLC, in stratified analyses by genders and cell types, but risk reductions were greater larger for SQCC-COPD than for ADC-COPD (Table 2).

Effects of smoking on NSCLC-COPD in comparison with NSCLC-NO-COPD

To examine whether smoking is an independent risk factor for NSCLC-COPD, we further characterize the effect of smoking on NSCLC-COPD using NSCLC-NO-COPD patients as references. Compared with NSCLC-NO-COPD subjects, increased associations of smoking with NSCLC-COPD were seen in both ex-smokers and in current smokers, as well as in dose-response manners with smoking exposure levels (Table 2–4).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study investigating risk factors for the co-development of NSCLC with COPD. Our data indicate that smoking dosage is the most important risk factor for NSCLC-COPD, especially in females and in NSCLC patients with squamous cell carcinoma subtype. Whereas quitting smoking clearly reduced the risk of developing NSCLC-COPD. In support of this, comparison analysis between NSCLC-COPD and NSCLC-NO-COPD indicates that smoking is an independent risk factor for NSCLC-COPD.

The main strength of this study is its ample sample. This large sample size allows us to conduct analyses on subgroups such as genders and specific histologic types. By selecting patients with a pathologically confirmed diagnosis of NSCLC we avoid a possible bias due to inaccurate histological characterization. In addition, the detailed ascertainment of life-time smoking exposure by standardized questionnaire enables us to explore the dose-response relationship between smoking and the risk of NSCLC-COPD.

Our data showed that smoking quantity is the most significant risk factor for developing NSCLC-COPD. We also observed lower risk of NSCLC-COPD in former smokers than in current smokers. These observations are in agreement with published studies showing a similar trend of association in COPD23 and NSCLC,24 respectively. On the other hand, quitting smoking reduces the relative risk of NSCLC-COPD. This is also in agreement with previous reports in COPD25 and in NSCLC26 phenotypes. Smokers showed a large reduction in relative risk after quitting smoking, but the risk did not fully return to baseline in accordance with other observations.27 A drop in OR was evident already after 5 years of smoking cessation pointing to a potential promoting effect of tobacco smoke. This highlights the importance of smoking cessation were both short term and long term.

Using non-parametric models to explore the shape of the dose-response curve, we showed that the association between NSCLC-COPD occurrence and smoking intensity plateaued at an amount of about 50 pack-years. Several hypotheses may explain the plateau: 1. Heavy smokers may adapt to smoking by inhaling relatively less from each cigarette;28 2. Enzymatic saturation during the metabolic transformation of tobacco smoke in heavy smokers;29 3. DNA repair capacity after carcinogen damages is more efficient in heavy than in light smokers.30

A stronger association between smoking intensity and NSCLC-COPD was observed for women than for men. Our findings are consistent with some prior studies demonstrating an increased susceptibility to COPD in female smokers.31–32 There has been an alarming rise in the number of women diagnosed with COPD every year compared with men, with the number of deaths from COPD being higher in women than in men in both the United States and Canada.33–34 Women may be biologically more susceptible to the adverse effect of smoking than men, due to gender differences in cigarettes smoke metabolism.35 When normalized for pack-years smoked, the rate of lung function decline in women is faster than that of men, with women losing as much as 10ml/pack-year and men losing 8ml/pack-year.31,36 The airways of women are anatomically smaller, and hence each cigarette smoked may represent a proportionally greater exposure.37 Dimensional, immunological, and hormonal determinants are other biological possibilities for a gender difference.38 Additionally, in patients with COPD who have successfully quit smoking, women had a 2.5-fold greater improvement in lung function compared with men who quit.39 Sex differences in both clinical and pathological outcomes of patients with lung cancer have been observed.40 Data from case-control studies suggested that women have a higher susceptibility to cigarette smoke on NSCLC.41–42 However, several cohort studies have indicated that there is no gender difference in susceptibility to NSCLC,43–44 which may be due to variation in smoking patterns and prevalence between countries.45 Most recently, an analysis consisting of 12,121 incident cases of NSCLC and 48,216 age-and sex-matched controls reported that women who have ever smoked moderately or heavily had a higher risk of NSCLC than men who smoked the same amount.45

In agreement with reports in NSCLC,24,46 we found that all major histological types of NSCLC-COPD are associated with smoking, although the association was stronger for SQCC-COPD than for ADC-COPD. Quitting smoking clearly reduced the risk of developing any types of NSCLC-COPD, compared with continuing to smoke. The decline in risk after quitting was stronger for SQCC than for ADC.27,47 Smokers with COPD also had a higher risk of developing SQCC.7,48 The strength of the association with tobacco smoke may differ by histological type due to lower exposure of tobacco smoke particles to sites that are more peripheral in the respiratory tract. SQCC occurs mainly in the larger central bronchi, an area highly exposed to tobacco smoke, compared to ADC, located in the peripheral sections of the lung.49

Several limitations of this study should be considered when interpreting our findings. First, the information on physician-diagnosed COPD was self-reported, which could result in misclassification of the disease.50 However, several previous studies have shown that self-reported COPD was strongly associated with spirometry-based COPD and was deemed accurate for epidemiologic studies.19–20 Similarly, a validation of self-reported physician-diagnosed COPD in the cohort of Nurse’ Health Study found high rates of lung disease (emphysema, chronic bronchitis, or COPD) confirmed by medical records.18 It is also possible that a proportion of undiagnosed COPD cases may exist in the current population. If present, however, this misclassification of self-reported COPD would likely result in biases of ORs toward the null. Furthermore, because of the cross-sectional design of the study we could not accurately measure the effect of COPD before the onset of NSCLC-COPD. This temporality issue is complicated by the fact that smoking cessation is known to have a strong risk-reduction effect on COPD and NSCLC. Future prospective studies in other populations with similar demographic and clinic-pathologic characteristics are necessary to confirm the conclusions of our study. Another limitation to this study, and all studies that rely on self-report, is the possibility of misclassification of history COPD, such as under diagnosed COPD. Given that COPD status in cases and controls was both defined by self-reported, it is probably that this potential bias of misclassification may not change the direction of associations in the present study. Future studies need to include better defined COPD phenotype that include lung function test variables.

In summary, our findings indicate that smoking is the major cause of NSCLC-COPD, with the risks stronger for females and for SQCC cell type. Additional studies should include better defining COPD using spirometry and computed tomography, as well as together with smoking biomarkers, to more accurately characterize the effects of smoking on NSCLC-COPD risk.

Table 3.

Associations of smoking with risk of developing NSCNSCLC by COPD and gender

| Variables | NSCLC-NO-COPD (n = 2865) vs. controls (n = 1646) | NSCLC-COPD (n = 999) vs. controls (n = 1646) | NSCLC-COPD (N = 999) vs. NSCLC-NO-COPD (N = 2865) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | ||||||||

| OR* (95%CI) | P* | OR* (95%CI) | P* | OR# (95%CI) | P* | OR# (95%CI) | P* | OR# (95%CI) | P* | OR# (95%CI) | P* | ||

| Smoking status | |||||||||||||

| Never | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||||||

| Ex-smokers | 2.25 (1.77–2.87) | <0.0001 | 1.99 (1.61–2.46) | <0.0001 | 10.24 (5.5–18.99) | <0.0001 | 11.60 (7.07–19.03) | <0.0001 | 3.95 (2.16–7.24) | <0.0001 | 5.06 (3.14–8.15) | <0.0001 | |

| Current -smokers | 5.26 (3.91–7.07) | <0.0001 | 3.58 (2.80–4.58) | <0.0001 | 52.43 (26.73–102.8) | <0.0001 | 40.41 (23.89–68.37) | <0.0001 | 6.43 (3.47–11.89) | <0.0001 | 8.95 (5.55–14.47) | <0.0001 | |

| Pack-years | |||||||||||||

| 0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||||||

| 1–<20 | 1.28 (0.96–1.70) | 0.09 | 1.41 (1.12–1.78) | 0.004 | 2.11 (1.01–4.39) | 0.047 | 3.46 (1.99–6.02) | <0.0001 | 1.57 (0.76–3.28) | 0.225 | 2.36 (1.37–4.07) | 0.002 | |

| 20–<40 | 2.48 (1.87–3.30) | <0.0001 | 2.74 (2.13–3.52) | <0.0001 | 10.22 (5.37–19.46) | <0.0001 | 17.14 (10.17–28.90) | <0.0001 | 4.01 (2.13–7.56) | <0.0001 | 5.54 (3.37–9.09) | <0.0001 | |

| 40–<60 | 4.96 (3.59–6.86) | <0.0001 | 3.69 (2.73–4.99) | <0.0001 | 28.26 (14.73–54.22) | <0.0001 | 34.54 (20.25–58.90) | <0.0001 | 5.66 (3.04–10.55) | <0.0001 | 9.05 (5.52–14.81) | <0.0001 | |

| ≥60 | 5.93 (4.35–8.08) | <0.0001 | 6.01 (4.04–8.93) | <0.0001 | 44.31 (29.31–67.00) | <0.0001 | 66.60 (36.99–120.0) | <0.0001 | 6.11 (3.31–11.26) | <0.0001 | 11.53 (7.00–18.97) | <0.0001 | |

| trend | 1.63 (1.52–1.75) | <0.0001 | 1.58 (1.47–1.71) | <0.0001 | 2.51 (2.24–2.83) | <0.0001 | 2.92 (2.60–3.29) | <0.0001 | 1.46 (1.33–1.61) | <0.0001 | 1.75 (1.60–1.90) | <0.0001 | |

| Interaction | OR = 1.01 (0.71–1.07); P = 0.197 | OR = 0.86 (0.73–1.02); P = 0.077 | OR = 0.85 (0.75–0.97); P = 0.014 | ||||||||||

| Years since quitting smoking # | |||||||||||||

| <5 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||||||

| 5–<10 | 0.77 (0.44–1.34) | 0.36 | 0.68 (0.40–1.15) | 0.15 | 0.95 (0.48–1.92) | 0.89 | 0.57 (0.30–1.08) | 0.09 | 1.06 (0.67–1.66) | 0.815 | 0.96 (0.61–1.49) | 0.845 | |

| 10–<15 | 0.41 (0.25–0.68) | 0.0006 | 0.57 (0.34–0.95) | 0.03 | 0.37 (0.19–0.72) | 0.004 | 0.29 (0.15–0.54) | 0.0001 | 0.79 (0.49–1.28) | 0.343 | 0.65 (0.41–1.02) | 0.061 | |

| 15–<20 | 0.33 (0.20–0.55) | <0.0001 | 0.60 (0.35–1.03) | 0.06 | 0.23 (0.11–0.46) | <0.0001 | 0.26 (0.13–0.54) | 0.0003 | 0.62 (0.38–1.03) | 0.064 | 0.50 (0.30–0.84) | 0.008 | |

| ≥20 | 0.21 (0.13–0.32) | <0.0001 | 0.45 (0.29–0.70) | 0.0004 | 0.08 (0.05–0.15) | <0.0001 | 0.09 (0.05–0.16) | <0.0001 | 0.36 (0.23–0.55) | <0.0001 | 0.27 (0.18–0.42) | 0.013 | |

| trend | 0.67 (0.61–0.74) | <0.0001 | 0.84 (0.77–0.93) | 0.0003 | 0.51 (0.44–0.59) | <0.0001 | 0.55 (0.48–0.63) | <0.0001 | 0.76 (0.69–0.84) | <0.0001 | 0.72 (0.65–0.79) | <0.0001 | |

Adjusted for age;

among ex-smokers

Acknowledgments

We thank the physicians and surgeons of the Massachusetts General Hospitalfor their support, and the study participants.

Grant sponsor: National Institute of Health; Grant number: CA92824, CA74386, CA90578

Abbreviations

- NSCLC

non-small cell lung cancer

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- OR

odds ratio

- CI

confidence interval

- SQCC

squamous cell carcinoma

- ADC

adenocarcinoma

References

- 1.Lokke A, Lange P, Scharling H, Fabricius P, Vestbo J. Developing COPD: a 25 year follow up study of the general population. Thorax. 2006;61:935–939. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.062802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sekine Y, Katsura H, Koh E, Hiroshima K, Fujisawa T. Early detection of COPD is important for lung cancer surveillance. Eur Respir J. 2012;39:1230–1240. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00126011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turner MC, Chen Y, Krewski D, Calle EE, Thun MJ. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with lung cancer mortality in a prospective study of never smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:285–290. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200612-1792OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Young RP, Hopkins RJ, Christmas T, Black PN, Metcalf P, Gamble GD. COPD prevalence is increased in lung cancer, independent of age, sex and smoking history. Eur Respir J. 2009;34:380–386. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00144208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Torres JP, Bastarrika G, Wisnivesky JP, Alcaide AB, Campo A, Seijo LM, Pueyo JC, Villanueva A, Lozano MD, Montes U, Montuenga L, Zulueta JJ. Assessing the relationship between lung cancer risk and emphysema detected on low-dose CT of the chest. Chest. 2007;132:1932–1938. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Purdue MP, Gold L, Jarvholm B, Alavanja MC, Ward MH, Vermeulen R. Impaired lung function and lung cancer incidence in a cohort of Swedish construction workers. Thorax. 2007;62:51–56. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.064196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loganathan RS, Stover DE, Shi W, Venkatraman E. Prevalence of COPD in women compared to men around the time of diagnosis of primary lung cancer. Chest. 2006;129:1305–1312. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.5.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson DO, Weissfeld JL, Balkan A, Schragin JG, Fuhrman CR, Fisher SN, Wilson J, Leader JK, Siegfried JM, Shapiro SD, Sciurba FC. Association of radiographic emphysema and airflow obstruction with lung cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:738–744. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200803-435OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Young RP, Hopkins RJ. How the genetics of lung cancer may overlap with COPD. Respirology. 2011;16:1047–1055. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.02019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boelens MC, Gustafson AM, Postma DS, Kok K, van der Vries G, van der Vlies P, Spira A, Lenburg ME, Geerlings M, Sietsma H, Timens W, van den Berg A, et al. A chronic obstructive pulmonary disease related signature in squamous cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2011;72:177–183. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Andrade M, Li Y, Marks RS, Deschamps C, Scanlon PD, Olswold CL, Jiang R, Swensen SJ, Sun Z, Cunningham JM, Wampfler JA, Limper AH, et al. Genetic variants associated with the risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with and without lung cancer. Cancer Prev Res. 2012;5:365–373. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pride NB, Soriano JB. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the United Kingdom: trends in mortality, morbidity, and smoking. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2002;8:95–101. doi: 10.1097/00063198-200203000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brenner DR, McLaughlin JR, Hung RJ. Previous lung diseases and lung cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one. 2011;6:e17479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhai R, Liu G, Zhou W, Su L, Heist RS, Lynch TJ, Wain JC, Asomaning K, Lin X, Christiani DC. Vascular endothelial growth factor genotypes, haplotypes, gender, and the risk of non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:612–617. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heist RS, Zhai R, Liu G, Zhou W, Lin X, Su L, Asomaning K, Lynch TJ, Wain JC, Christiani DC. VEGF polymorphisms and survival in early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:856–862. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.5947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun S, Schiller JH, Gazdar AF. Lung cancer in never smokers--a different disease. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:778–790. doi: 10.1038/nrc2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barr RG, Herbstman J, Speizer FE, Camargo CA., Jr. Validation of self-reported chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a cohort study of nurses. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:965–971. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.10.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Straus SE, McAlister FA, Sackett DL, Deeks JJ. Accuracy of history, wheezing, and forced expiratory time in the diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:684–688. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.20102.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eisner MD, Trupin L, Katz PP, Yelin EH, Earnest G, Balmes J, Blanc PD. Development and validation of a survey-based COPD severity score. Chest. 2005;127:1890–1897. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.6.1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenland S. Dose-response and trend analysis in epidemiology: alternatives to categorical analysis. Epidemiology. 1995;6:356–365. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199507000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marrie RA, Dawson NV, Garland A. Quantile regression and restricted cubic splines are useful for exploring relationships between continuous variables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:511–517. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.05.015. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dresler CM, Leon ME, Straif K, Baan R, Secretan B. Reversal of risk upon quitting smoking. Lancet. 2006;368:348–349. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69086-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pesch B, Kendzia B, Gustavsson P, Jöckel KH, Johnen G, Pohlabeln H, Olsson A, Ahrens W, Gross IM, Brüske I, Wichmann HE, Merletti F, et al. Cigarette smoking and lung cancer--relative risk estimates for the major histological types from a pooled analysis of case-control studies. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:1210–1219. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garcia Rodriguez LA, Wallander MA, Tolosa LB, Johansson S. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in UK primary care: incidence and risk factors. COPD. 2009;6:369–379. doi: 10.1080/15412550903156325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dela Cruz CS, Tanoue LT, Matthay RA. Lung cancer: epidemiology, etiology, and prevention. Clin Chest Med. 2011;32:605–644. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khuder SA, Mutgi AB. Effect of smoking cessation on major histologic types of lung cancer. Chest. 2001;120:1577–1583. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.5.1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vineis P, Kogevinas M, Simonato L, Brennan P, Boffetta P. Levelling-off of the risk of lung and bladder cancer in heavy smokers: an analysis based on multicentric case-control studies and a metabolic interpretation. Mutat Res. 2000;463:103–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruano-Ravina A, Figueiras A, Montes-Martinez A, Barros-Dios JM. Doseresponse relationship between tobacco and lung cancer: new findings. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2003;12:257–263. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200308000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wei Q, Cheng L, Amos CI, Wang LE, Guo Z, Hong WK, Spitz MR. Repair of tobacco carcinogen-induced DNA adducts and lung cancer risk: a molecular epidemiologic study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1764–1772. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.21.1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gan WQ, Man SF, Postma DS, Camp P, Sin DD. Female smokers beyond the perimenopausal period are at increased risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Res. 2006;7:52. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sorheim IC, Johannessen A, Gulsvik A, Bakke PS, Silverman EK, DeMeo DL. Gender differences in COPD: are women more susceptible to smoking effects than men? Thorax. 2010;65:480–485. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.122002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chapman KR. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: are women more susceptible than men? Clin Chest Med. 2004;25:331–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mannino DM, Homa DM, Akinbami LJ, Ford ES, Redd SC. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease surveillance--United States: 1971–2000. Respir Care. 2002;47:1184–1199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ben-Zaken Cohen S, Pare PD, Man SF, Sin DD. The growing burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer in women: examining sex differences in cigarette smoke metabolism. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:113–120. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200611-1655PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prescott E, Osler M, Andersen PK, Bjerg A, Hein HO, Borch-Johnsen K, Lange P, Schnohr P, Vestbo J. Mortality in women and men in relation to smoking. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27:27–32. doi: 10.1093/ije/27.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Han MK, Postma D, Mannino DM, Giardino ND, Buist S, Curtis JL, Martinez FJ. Gender and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: why it matters. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:1179–1184. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200704-553CC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Townsend EA, Miller VM, Prakash YS. Sex differences and sex steroids in lung health and disease. Endocr Rev. 2012;33:1–47. doi: 10.1210/er.2010-0031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Connett JE, Murray RP, Buist AS, Wise RA, Bailey WC, Lindgren PG, Owens GR. Changes in smoking status affect women more than men: results of the Lung Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:973–979. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harichand-Herdt S, Ramalingam SS. Gender-associated differences in lung cancer: clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes in women. Semin Oncol. 2009;36:572–580. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Henschke CI, Yip R, Miettinen OS. Women's susceptibility to tobacco carcinogens and survival after diagnosis of lung cancer. JAMA. 2006;296:180–184. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.2.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Belani CP, Marts S, Schiller J, Socinski MA. Women and lung cancer: epidemiology, tumor biology, and emerging trends in clinical research. Lung Cancer. 2007;55:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bain C, Feskanich D, Speizer FE, Thun M, Hertzmark E, Rosner BA, Colditz GA. Lung cancer rates in men and women with comparable histories of smoking. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:826–834. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Freedman ND, Leitzmann MF, Hollenbeck AR, Schatzkin A, Abnet CC. Cigarette smoking and subsequent risk of lung cancer in men and women: analysis of a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:649–656. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70154-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iyen-Omofoman B, Hubbard RB, Baldwin DR, Tata LJ. The association between smoking quantity and lung cancer in men and women. Chest. 2013;143:123–129. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khuder SA. Effect of cigarette smoking on major histological types of lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Lung Cancer. 2001;31:139–148. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(00)00181-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kenfield SA, Wei EK, Stampfer MJ, Rosner BA, Colditz GA. Comparison of aspects of smoking among the four histological types of lung cancer. Tob Control. 2008;17:198–1204. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.022582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Papi A, Casoni G, Caramori G, Guzzinati I, Boschetto P, Ravenna F, Calia N, Petruzzelli S, Corbetta L, Cavallesco G, Forini E, Saetta M, et al. COPD increases the risk of squamous histological subtype in smokers who develop non-small cell lung carcinoma. Thorax. 2004;59:679–681. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.018291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morabia A, Wynder EL. Cigarette smoking and lung cancer cell types. Cancer. 1991;68:2074–2078. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19911101)68:9<2074::aid-cncr2820680939>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwartz AG, Cote ML, Wenzlaff AS, Van Dyke A, Chen W, Ruckdeschel JC, Gadgeel S, Soubani AO. Chronic obstructive lung diseases and risk of non-small cell lung cancer in women. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:291–299. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181951cd1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]