Background: The calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) is a key mediator of Ca2+ homeostasis in vivo.

Results: An l-Phe binding site at the CaSR hinge region globally enhances its cooperative activation by Ca2+.

Conclusion: Communication between the binding sites for Ca2+ and l-Phe is crucial for functional cooperativity of CaSR-mediated signaling.

Significance: The results provide important insights into the molecular basis of Ca2+ sensing by the CaSR.

Keywords: Amino Acid, Calcium Imaging, Calcium Signaling, Cooperativity, G Protein-coupled Receptors (GPCR), Calcium-sensing Receptor, Calcium Oscillation

Abstract

Functional positive cooperative activation of the extracellular calcium ([Ca2+]o)-sensing receptor (CaSR), a member of the family C G protein-coupled receptors, by [Ca2+]o or amino acids elicits intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) oscillations. Here, we report the central role of predicted Ca2+-binding site 1 within the hinge region of the extracellular domain (ECD) of CaSR and its interaction with other Ca2+-binding sites within the ECD in tuning functional positive homotropic cooperativity caused by changes in [Ca2+]o. Next, we identify an adjacent l-Phe-binding pocket that is responsible for positive heterotropic cooperativity between [Ca2+]o and l-Phe in eliciting CaSR-mediated [Ca2+]i oscillations. The heterocommunication between Ca2+ and an amino acid globally enhances functional positive homotropic cooperative activation of CaSR in response to [Ca2+]o signaling by positively impacting multiple [Ca2+]o-binding sites within the ECD. Elucidation of the underlying mechanism provides important insights into the longstanding question of how the receptor transduces signals initiated by [Ca2+]o and amino acids into intracellular signaling events.

Introduction

It has long been recognized that Ca2+ acts as a second messenger that is released from intracellular stores and/or taken up from the extracellular environment in response to external stimuli to regulate diverse cellular processes. The discovery of the parathyroid Ca2+-sensing receptor (CaSR)2 by Brown et al. (1) has established a new paradigm of Ca2+ signaling. In addition to its known role as a second messenger, extracellular Ca2+ can function as a first messenger by CaSR-mediated triggering of multiple intracellular signaling pathways, including activation of phospholipases C, A2, and D, and various mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), as well as inhibition of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) production (2–7). This receptor is present in the key tissues involved in [Ca2+]o homeostasis (e.g., parathyroid, kidney, and bone) and diverse other nonhomeostatic tissues (e.g., brain, skin, etc.) (8–11). CaSR consists of a large N-terminal extracellular domain (ECD) (∼600 residues) folded into a Venus flytrap motif, followed by a seven-pass transmembrane region and a cytosolic C terminus. The ECD has been shown to play an important role in the cooperative response of the CaSR to [Ca2+]o. Elevations in [Ca2+]o activate the CaSR, evoking increases in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i), producing [Ca2+]i oscillations, modulating the rate of parathyroid hormone secretion, and regulating gene expression (3, 12–14). The pattern of [Ca2+]i oscillations is one of the most important signatures reflecting the state of CaSR activity.

More than 200 naturally occurring mutations have been identified in the CaSR that either inactivate the receptor (reducing sensitivity to [Ca2+]o), leading to familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia or neonatal severe hyperparathyroidism, or activate it (increasing sensitivity to [Ca2+]o), thereby causing autosomal dominant hypoparathyroidism (15–17). Several of these naturally occurring mutations of CaSR exhibit altered functional cooperativity (15).

Functional cooperativity of CaSR (i.e., based on biological activity determined using functional assays rather than a direct binding assay), particularly the functional positive homotropic cooperative response to [Ca2+]o, is essential for the ability of the receptor to respond over a narrow physiological range of [Ca2+]o (1.1–1.3 mm) (3). CaSR has an estimated Hill coefficient of 3–4 for its regulation of processes such as activating intracellular Ca2+ signaling and inhibiting parathyroid hormone release. Under physiological conditions, l-amino acids, especially aromatic amino acids (e.g., l-Phe), as well as short aliphatic and small polar amino acids (18), potentiate the high [Ca2+]o-elicited activation of the CaSR by altering the EC50 values required for [Ca2+]o-evoked [Ca2+]i responses and its functional cooperativity (19, 20). In aggregate, the levels of amino acids in human serum in the fed state are close to those activating the CaSR in vitro (19, 21) and can further enhance functional cooperativity via positive heterotropic cooperativity. Recently, several groups have reported that the CaSR in cells within the lumen of the gastrointestinal tract is activated by l-Phe and other amino acids, which have long been recognized as activators of key digestive processes. Hence, the CaSR enables the tract to monitor events relevant to both mineral ion and protein/amino acid metabolism in addition to the sensing capability of CaSR in blood and other extracellular fluids (19, 22, 23). Glutathione and its γ-glutamylpeptides also allosterically modulate the CaSR at a site similar to the l-amino acid-binding pocket but with over 1,000-fold higher potencies (20, 24). Thus, CaSR is essential for monitoring and integrating information from both mineral ions/nutrients/polyamines in blood and related extracellular fluids. Nevertheless, we still lack a thorough understanding of the molecular mechanisms by which CaSR is activated by [Ca2+]o and amino acids, which, in turn, regulate CaSR functional positive cooperativity. In addition, in a clinical setting, the molecular basis for the alterations in this cooperativity caused by disease-associated mutations is largely unknown because of the lack of knowledge of the structure of this receptor and its weak binding affinities for [Ca2+]o and amino acids (13, 15, 25, 26).

In the present study, we use two complementary approaches—monitoring [Ca2+]i oscillations in living cells and performing molecular dynamics (MD) simulations—to provide important insights into how the CaSR functions and the behavior of the receptor at the atomic level. We first demonstrate that the molecular connectivity between [Ca2+]o-binding sites that is encoded within key Ca2+-binding site 1 in the hinge region of the CaSR ECD is responsible for the functional positive homotropic cooperativity in the CaSR response to [Ca2+]o. We further identify an l-Phe-binding pocket adjacent to Ca2+-binding site 1. We show that occupancy of this binding pocket by l-Phe is essential for functional positive heterotropic cooperativity by virtue of its having a marked impact on all five of the predicted Ca2+-binding sites in the ECD with regard to [Ca2+]o-evoked [Ca2+]i signaling. Furthermore, with MD simulations, we show that the simulated motions of Ca2+-binding site 1 are correlated with those of the other predicted Ca2+-binding sites. Finally, the dynamic communication of l-Phe at its predicted binding site in the hinge region with the CaSR Ca2+-binding sites not only influences the adjacent [Ca2+]o binding site 1 but also globally (i.e., by exerting effects widely over the ECD) enhances cooperative activation of the receptor in response to alterations in [Ca2+]o.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Computational Prediction of l-Phe-binding Site and Ca2+-Binding Sites from a Model Structure

The structure of the extracellular domain of CaSR (residues 25–530) was modeled based on the crystal structure of metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 (mGluR1) (Protein Data Bank codes 1EWT, 1EWK, and 1ISR), and the potential Ca2+-binding sites in the CaSR ECD were predicted using MetalFinder (25, 27). Prediction of the l-Phe-binding site was performed by AutoDock-Vina (28). In brief, the docking center and grid box of the model structure and the rotatable bonds of l-Phe were defined by AutoDock tools 1.5.4. The resultant l-Phe coordinates were combined back to the Protein Data Bank file of the model structure for input into the ligand-protein contacts and contacts of structural units (LPC/CSU) server to analyze interatomic contacts between the ligand and receptor (29). The residues within 5 Å around l-Phe were considered as l-Phe-binding residues.

Measurement of [Ca2+]i Responses in Single Cells Transfected with WT or Mutant CaSRs with or without l-Phenylalanine

Measurement of intracellular free Ca2+ was assessed as described by Huang et al. (30). Briefly, wild type CaSR or its mutants were transiently transfected into HEK293 cells grown on coverslips and cultured for 48 h. The cells were subsequently loaded for 15 min using 4 μm Fura-2 AM in 2 ml of physiological saline buffer (10 mm HEPES, 140 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 1.0 mm MgCl2, 1 mm CaCl2, pH 7.4). The coverslips were mounted in a bath chamber on the stage of a Leica DM6000 fluorescence microscope, and the cells were incubated in calcium-free physiological saline buffer for 5 min. The cells were then alternately illuminated with 340- or 380-nm light, and the fluorescence at an emission wavelength 510 nm was recorded in real time as the concentration of extracellular Ca2+ was increased in a stepwise manner in the presence or absence of 5 mm l-Phe. The ratio of the emitted fluorescence intensities resulting from excitation at both wavelengths was utilized as a surrogate for changes in [Ca2+]i and was further plotted and analyzed as a function of [Ca2+]o. All experiments were performed at room temperature. The signals from 30–60 single cells were recorded for each measurement. Oscillations were defined as three successive fluctuations in [Ca2+]i after the initial peak.

Measurement of [Ca2+]i in Cell Populations by Fluorimetry

The [Ca2+]i responses of wild type CaSR and its mutants were measured as described by Huang et al. (25). Briefly, CaSR-transfected HEK293 cells were grown on 13.5 × 20-mm coverslips. After the cells reached 90% confluence, they were loaded by incubation with 4 μm Fura-2 AM in 20 mm HEPES, containing 125 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 1.25 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgCl2, 1 mm NaH2PO4, 1% glucose, and 1% BSA (pH 7.4) for 1 h at 37 °C and then washed once with 20 mm HEPES (pH 7.4) containing 125 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 0.5 mm CaCl2, 0.5 mm MgCl2, 1% glucose, and 1% BSA (bath buffer). The coverslips with transfected, Fura-2-loaded HEK293 cells were placed diagonally in 3-ml quartz cuvettes containing bath buffer. The fluorescence spectra at 510 nm were measured during stepwise increases in [Ca2+]o with alternating excitation at 340 or 380 nm. The ratio of the intensities of the emitted light at 510 nm when excited at 340 or 380 nm was used to monitor changes in [Ca2+]i. The EC50 and Hill constants were fitted using the following Hill equation,

|

where ΔS is the total signal change in the equation and [M] is the free ligand concentration.

MD Simulation and Correlation Analysis Using Amber

MD simulation provides an approach complementary to the experiments in live cells for understanding biomolecular structure, dynamics, and function. The initial coordinates for all the simulations were modeled from the 2.20 Å resolution x-ray crystal structure of mGluR1 with Protein Data Bank code 1EWK (31). The AMBER 10 suite of programs (32) was used to carry out all of the simulations in an explicit TIP3P water model (33), using the modified version of the all-atom Cornell et al. (34) force field and the reoptimized dihedral parameters for the peptide ω-bond (35). An initial 2-ns simulation was performed using NOE restraint during the equilibration to reorient the side chains residues in the Ca2+-binding site, but no restraints were used during the actual simulation. A total of three MD simulations were carried out for 50 ns each on the apo-form and ligand-loaded forms. During the simulations, an integration time step of 0.002 ps was used to solve Newton's equation of motion. The long range electrostatic interactions were calculated using the particle mesh Ewald method (36), and a cutoff of 9.0 Å was applied for nonbonded interactions. All bonds involving hydrogen atoms were restrained using the SHAKE algorithm (37). The simulations were carried out at a temperature of 300 K and a pressure of 1 bar. A Langevin thermostat was used to regulate the temperature with a collision frequency of 1.0 ps−1. The trajectories were saved every 500 steps (1 ps). The trajectories were analyzed using the ptraj module in Amber 10.

Accelerated Molecular Dynamics Simulation

Accelerated MD was carried out on the free CaSR ECD using the Rotatable accelerated Molecular Dynamics, (RaMD) method (38) implemented in a pmemd module of AMBER on the rotatable torsion. A boost energy, E, of 2,000 kcal/mol was added to the average dihedral energy, and a tuning parameter, α, of 200 kcal/mol was used. The dual boost was also applied to accelerate the diffusive and solvent dynamics as previously described (39). The simulation conditions were similar to that of the normal MD simulations above. Principal component analysis was carried out on the trajectories using the ptraj module in AMBER. The directions of the eigenvectors for the slowest modes were visualized using the Interactive Essential Dynamics plugin (40).

Docking Studies of Phe, Asp, and Glutathione

The binding energies for the ligands were calculated using an ensemble-docking method and Autodock vina (28). The ensemble of conformations of CaSR was generated using molecular dynamics simulations as described above. Gasteiger charges were assigned to the ligands and CaSR using the Autodock ADT program. The ligands were flexible during docking to each conformation of CaSR using the following parameters: the grid spacing was 1.0 Å; the box size was 25 Å in each dimension, and the center of the box was chosen as the center of the active site of CaSR, with a large enough space to sample all possible ligand conformations within the box. The maximum number of binding modes saved was set to 10. The conformation with the lowest binding energy was used and assumed to be the best binder. Distributions of the binding energies for each ligand were calculated based on the lowest binding energy of each ligand to each conformation in the ensemble of CaSR conformations.

Principal Component Analysis

Using the ptraj module of AMBER 10, principal component analysis (PCA) (41, 42) was performed on all the atoms of the residues that are 5 Å away from site 1 of CaSR ECD. The covariance matrix of the x, y, and z coordinates of all the atoms obtained from each snapshot of the combined trajectories of the ligand-free CaSR ECD, the Ca2+-loaded form, the form loaded with only l-Phe, and the form loaded with both Ca2+ and l-Phe were calculated. The covariance matrix was further diagonalized to produce orthonormal eigenvectors and their corresponding eigenvalues, ranked on the basis of their corresponding variances. The first three eigenvectors, the principal components that contributed the majority of all the atomic fluctuations, were used to project the conformational space onto them, i.e., along two dimensions.

Statistics

The data are presented as means ± S.E. for the indicated number of experiments. Statistical analyses were carried out using the unpaired Student's t test when two groups were compared. A p value of < 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

RESULTS

Molecular Connectivity among Predicted Calcium-binding Sites Is Required for Functional Positive Cooperativity of CaSR

It has been documented that in several regions of the CaSR and mGluRs, the amino acid residues are highly conserved (43). Those conserved elements provide a structural framework for the modeling of the CaSR ECD. Among all the available crystal structures of the mGluRs, studies on mGluR1 give concrete structural information about ligand-free as well as various ligand-bound forms of the receptor. Moreover, CaSR and mGluR1 share similar signaling pathways and can form heterodimers with one another either in vivo or in vitro (44). Thus, the crystal structures of mGluR1 were employed for modeling the CaSR ECD. By using our own computational algorithms, we previously identified five putative Ca2+-binding sites in the modeled CaSR ECD (Fig. 1) (25, 26, 45). Among these, site 1 is located in the hinge region between the two lobes in the Venus flytrap motif. Among 34 newly identified naturally occurring missense mutations within the ECD, 18 are located within 10 Å of one or more of the predicted Ca2+-binding sites (15). Interestingly, a few disease-associated human mutations severely impair the functional cooperativity of CaSR (46).

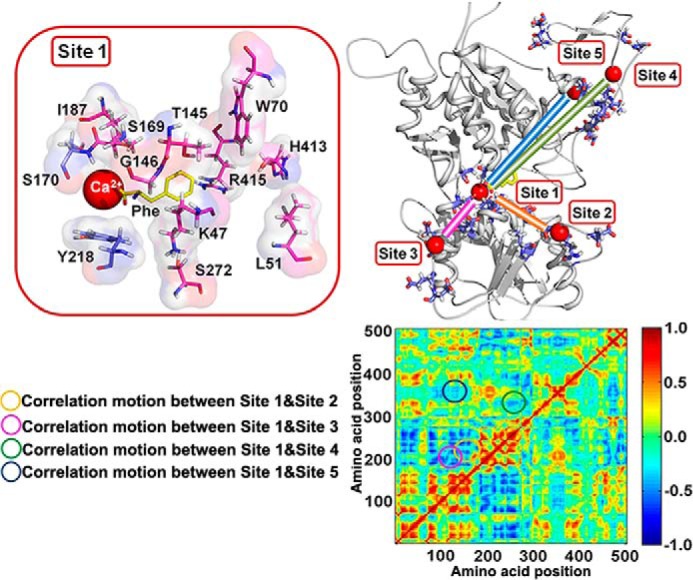

FIGURE 1.

Delineating the molecular connectivity associated with functional positive homotropic and positive heterotropic cooperativity within the CaSR ECD by molecular modeling of l-Phe- and Ca2+-binding sites. The model structure of the ECD of CaSR was based on the mGluR1 crystal structure (Protein Data Bank code 1ISR) and was generated using MODELER 9v4 and PyMOL. Upper right panel, five predicted Ca2+-binding sites are located in the ECD and are highlighted with frames. Residues involved in Ca2+-binding are shown in violet. Correlated motions among Ca2+-binding site 1 and the other Ca2+-binding sites are shown by lines of various colors. Upper panel, a zoomed in view of site 1; residues involved in the predicted l-Phe-binding site are highlighted in pink. Red, Ca2+; yellow, l-Phe. Lower panel, the correlation map of the modeled CaSR ECD structure. The correlation map is depicted based on MD simulations. The strongest negative correlation is given the value −1, whereas the strongest positive correlation is defined as +1. The circles on the correlation map reflect the movements between different binding sites (corresponding to the correlated motions in the upper right panel) during the MD simulation.

Functional positive homotropic cooperativity here refers to [Ca2+]o-induced changes in CaSR activity that can be ascribed to interactions between the five predicted Ca2+-binding sites, which are located in different regions of the ECD (47–49). To understand the observed cooperativity and the origin of changes in cooperativity caused by disease-associated mutations at the atomic level, we have carried out MD simulations on the modeled CaSR ECD to predict correlated motions. MD simulation provides an approach complementary to the experiments in live cells for understanding biomolecular structure, dynamics, and function (50). We calculated the cross-correlation coefficients of each residue with those of all of the other residues in the CaSR ECD from the simulations (“Material and Methods”). Fig. 1 (lower right panel) shows the normalized correlation matrix map of both negative (blue) and positive (red) correlated motions between each pair of residues. Negative and positive correlated motions indicate movements in the opposite direction or in the same direction, respectively. Positive correlations occur between groups of residues if they are within the same domain or directly interact with each other. Fig. 1 shows strong correlations among residues from Ser169 to Ala324. Notably, the negative correlated motions between residues Lys47–Leu125 and residues Ser240–Ala300 suggest that the two lobes undergo a dynamic change similar to that of mGluR1 upon interactions with its ligands. Closer analysis indicates that residues involved in Ca2+-binding site 1 exhibit negative correlations with residues in sites 2–5 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Analysis of correlated motions of WT CaSR model structure

The cross-correlation coefficients of each residue to all of the other residues of the modeled CaSR ECD structure after docking with calcium were calculated from the simulation. The strongest positive correlation of a residue with itself is given the value 1; the strongest negative correlation between two residues is given the value −1. A cutoff at >0.7 and <−0.4 is considered as a strong correlation between residues. Strongly correlated residues in predicted calcium-binding sites are listed in the table.

| Residue pairs | |

|---|---|

| Negative correlation | Ser170 (site 1):Asp398 (site 5) |

| Asp190 (site 1):Ser244 (site 2) | |

| Asp190 (site 1):Asp248 (site 2) | |

| Glu297 (site 1):Asp248 (site 2) | |

| Asp190 (site 1):Gln253 (site 2) | |

| Glu297 (site 1):Gln253 (site 3) | |

| Glu218 (site 1):Glu350 (site 4) | |

| Glu297 (site 1):Glu378 (site 5) | |

| Positive correlation | Glu224 (site 3):Glu228 (site 3) |

| Glu228 (site 3):Glu229 (site 3) | |

| Ser244 (site 2):Asp248 (site 2) | |

| Ser244 (site 2):Gln253 (site 2) | |

| Glu350 (site 4):Glu353 (site 4) | |

| Glu354 (site 4):Glu353 (site 4) | |

| Glu378 (site 5):Glu379 (site 5) | |

| Asp398 (site 5):Glu399 (site 5) |

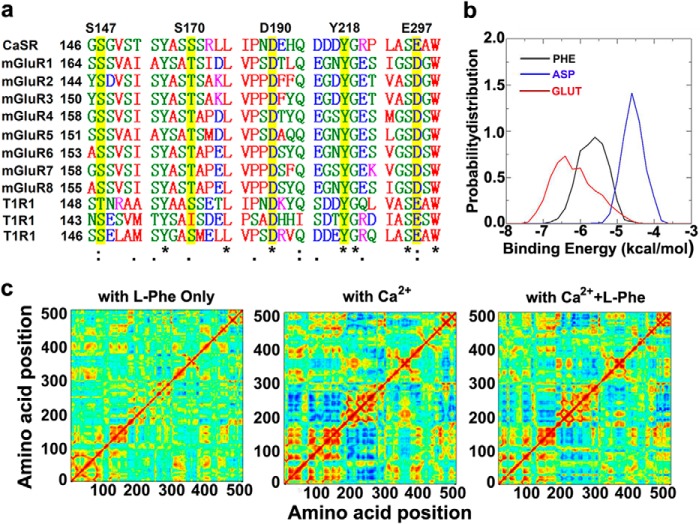

We then predicted a putative amino acid-binding site in the modeled CaSR based on its sequence homology to mGluR1 and its ligand-loaded form using AutoDock-Vina (28). As shown in Fig. 1 (upper left panel), this potential amino acid-binding pocket, formed by residues Lys47, Leu51, Trp70, Thr145, Gly146, Ser169, Ser170, Ile187, Tyr218, Ser272, His413, and Arg415, partially overlaps Ca2+-binding site 1 in the modeled CaSR ECD. Its predicted location is consistent with previous functional studies, suggesting important roles for Ser170 and Thr145 in amino acid-potentiated intracellular calcium responses (51–53). This l-Phe-binding site is also located within the hinge region of the ECD of CaSR with a relatively localized configuration during MD simulations. Other Ca2+-binding sites (sites 2–5) are more than 10 Å away from the l-Phe-binding site (26). This partial colocalization of predicted Ca2+-binding site 1 and the amino acid-binding site at the hinge domain in the ECD of the CaSR is also observed in other members of the family C G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), including mGluRs and taste receptors, which share some degree of sequence similarity with the CaSR (Fig. 2a) (1, 5, 10, 16, 54–56). The calculated free energies for the binding of CaSR with various ligands (in the order of glutathione > l-Phe > l-Asp) is in excellent agreement with the experimental results obtained by determining the EC50 of intracellular Ca2+ responses to the same ligands (Fig. 2b) (19).

FIGURE 2.

Sequence alignment and binding energy calculations based on the MD simulation of modeled CaSR ECD. a, sequence alignment of the orthosteric binding site for Glu in mGluR1 with CaSR and 10 other GPCRs of family C. Residues involved in predicted CaSR Ca2+-binding site 1 are labeled at the top, and corresponding residues in other group members are highlighted in yellow. b, the binding energies were calculated from molecular dynamics simulations and docking studies. Red line, CaSR-ECD docking with glutathione (GLUT); black line, CaSR-ECD docking with phenylalanine (PHE); blue line, CaSR-ECD docking with aspartic acid (ASP). c, the cross correlation matrices show the movements of residues during MD simulation. Positive values (in red) show residues moving in the same direction, whereas negative values (in blue) indicate residues moving away from one another.

We define functional positive heterotropic cooperativity as that which occurs when the functional positive cooperative effect of interaction with one ligand (e.g., Ca2+) affects the functional response resulting from interaction of a different ligand with the protein (i.e., an aromatic amino acid) (57). This term can be applied in the case of CaSR when it simultaneously senses Ca2+ and l-Phe. We have also observed greater correlated motions among the multiple Ca2+-binding sites after docking both Ca2+ and l-Phe compared with docking of l-Phe alone to the ECD domain of the CaSR (Fig. 2c). Taking these results together, we propose that there is molecular connectivity centered at predicted calcium-binding site 1 that plays an essential role in regulating the correlated motions among the multiple Ca2+-binding sites. Further communication of this site with the amino acid-binding site is likely to mediate functional heterotropic cooperativity of CaSR-mediated signaling, as shown later.

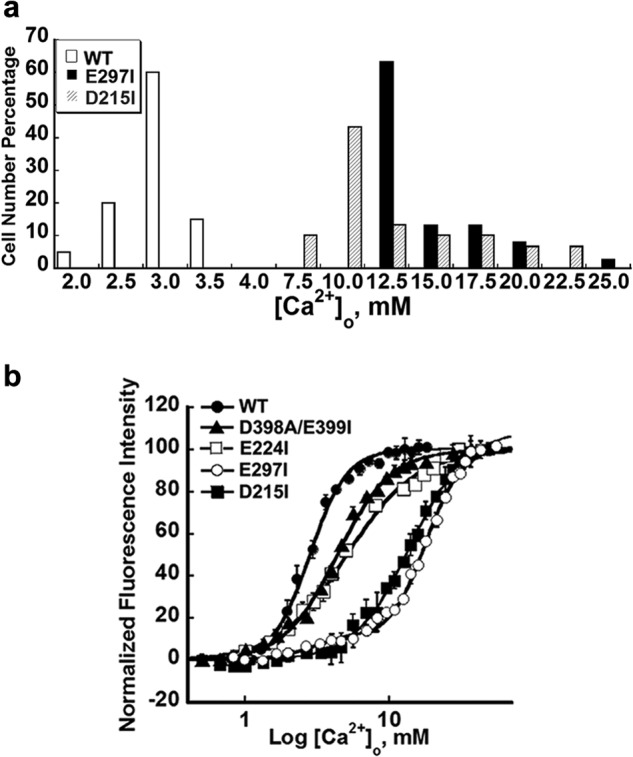

Functional Positive Homotropic Cooperativity among Ca2+-binding Sites

Given that it is not readily possible to perform radioligand binding assays on CaSR because of its low affinity for its ligands, especially Ca2+ (e.g., mm Kd), as well as difficulty in purification of CaSR, we monitored [Ca2+]i responses both by using a cuvette population assay and by monitoring [Ca2+]i oscillations using single-cell imaging to determine functional cooperativity of CaSR. HEK293 cells transfected with WT CaSR exhibited sigmoidal concentration response curves for [Ca2+]o-evoked [Ca2+]i responses (as monitored by changes in the ratio of fluorescence at 510 nm when excited at 340 or 380 nm) during stepwise increases in [Ca2+]o with a Hill coefficient of 3.0 ± 0.1 and a EC50 of 2.9 ± 0.2 mm. This result suggests strong positive homotropic cooperativity within the five predicted Ca2+-binding sites of the CaSR (Fig. 3). The sensitivity to agonist was assessed using the [Ca2+]o at which cells began to show [Ca2+]i oscillations and the frequency of the oscillations at the respective levels of [Ca2+]o at which more than 50% of the cells started to oscillate.

FIGURE 3.

Intracellular Ca2+ responses of CaSR mutants involving various Ca2+-binding sites following simulation with increases in [Ca2+]o. a, frequency distribution of the [Ca2+]i oscillation starting points in HEK293 cells transfected with WT, E297I, or D215I, respectively. The [Ca2+]o was recorded at the point when single cells started to oscillate. Approximately 30–60 cells were analyzed and further plotted as a bar chart. b, population assays of WT and Ca2+-binding site-related mutations. HEK293 cells transfected with CaSR or its mutants were loaded with Fura-2 AM. The intracellular Ca2+ level was assessed by monitoring emission at 510 nm with excitation alternately at 340 or 380 nm as described previously (30). The [Ca2+]i changes in the transfected cells were monitored using fluorimetry during stepwise increases in [Ca2+]o. The [Ca2+]i responses at various [Ca2+]o were plotted and further fitted using the Hill equation.

To seek the key determinants underlying the observed functional positive homotropic cooperativity, mutations were introduced into the various predicted Ca2+-binding sites of the CaSR by site-directed mutagenesis. The mutated receptors exhibited impaired Ca2+ sensing capabilities with altered oscillation patterns in single-cell studies and higher EC50 values compared with WT CaSR in population studies (Tables 2 and 3 and Figs. 3 and 4). Such population studies were also reported in our previous studies (25, 26). Results from Western blot and immunofluorescence staining using an anti-CaSR antibody indicated essentially equivalent expression of WT CaSR as well as its variants on the cell surface (Fig. 5). As shown in Fig. 3a, the level of [Ca2+]o required to initiate oscillations in mutant E297I at predicted Ca2+-binding site 1 or D215I at site 2 increased markedly from 3.0 ± 0.1 mm to 17.0 ± 0.4 and 13.9 ± 0.2 mm, respectively (n>30, p < 0.05). Correlating well with these results, the two mutants had significantly impaired responses to [Ca2+]o in the population assay with increased EC50 values (Table 3). The Hill coefficients in Table 3 and Fig. 3b indicate that the cooperativity among the various Ca2+-binding sites was impaired by mutating each of them separately. Strikingly, removal of Ca2+-binding ligand residues, such as E297I and Y218Q at site 1, converted the single process for functional activation of the WT CaSR by [Ca2+]o to biphasic functional processes, suggesting that the underlying cooperative binding mechanism had been substantially perturbed (Figs. 3b and 6d).

TABLE 2.

Summary of individual cellular responses to the indicated increments of [Ca2+]o in HEK293 cells transiently transfected with WT CaSR or mutations in the indicated Ca2+-binding sites

HEK293 cells were seeded on coverslips 1 day prior to transient transfection with the WT CaSR or Ca2+ binding-related CaSR mutants. After 48 h, the cells were loaded with Fura-2 as described under “Materials and Methods.” The level of [Ca2+]o was recorded at which [Ca2+]i oscillation started or reached a plateau, which are referred to as the starting point and ending point, respectively. For experiments without l-Phe, the frequency (peaks/min) was recorded at the level of [Ca2+]o at which the majority of the cells (>50%) started to oscillate, whereas for experiments with 5 mm l-Phe, the frequency was analyzed at the corresponding level of [Ca2+]o that was studied in the absence of l-Phe. Specifically, the frequency was studied at 3.0 mm [Ca2+]o for WT, 12.5 mm [Ca2+]o for E297I, 10.0 mm [Ca2+]o for D215I and D398A/E399I, 4 mm [Ca2+]o for E224I, and 5.0 mm [Ca2+]o for E353I. More than 30 cells were analyzed from a total of three independent experiments. The values are means ± S.E. NA, not available.

| Predicted sites | Residues | Mutants | Starting point |

Ending point |

Frequency |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without l-Phe | With l-Phe | Without l-Phe | With l-Phe | Without l-Phe | With l-Phe | |||

| mm | mm | |||||||

| WT | WT | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0.2a | 6.4 ± 0.3 | 4.3 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.2a | |

| Site 1 | Ser147, Ser170, Asp190, Tyr218, Glu297 | E297I | 17.0 ± 0.4b | 7.3 ± 0.2a | NA | NA | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 2.9 ± 0.1a |

| Site 2 | Asp215, Leu242, Ser244, Asp248, Gln253 | D215I | 13.9 ± 0.2b | 6.7 ± 0.3a | NA | 17.7 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 2.5 ± 0.2a |

| Site 3 | Glu224, Glu228, Glu229, Glu231, Glu232 | E224I | 5.0 ± 0.2b | 3.2 ± 0.1a | 16.8 ± 0.3 | 11.0 ± 0.1a | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.1a |

| Site 4 | Glu350, Glu353, Glu354, Asn386, Ser388 | E353I | 3.4 ± 0.1b | 2.4 ± 0.1a | 10.8 ± 0.2 | 4.9 ± 0.2a | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.2a |

| Site 5 | Glu378, Glu379, Thr396, Asp398, Glu399 | D398A/E399I | 9.3 ± 0.1b | 5.5 ± 0.2a | NA | NA | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.2a |

a Indicates significance with respect to the corresponding experiment in the same mutant without l-Phe (p < 0.05).

b Indicates significance with respect to wild type CaSR without l-Phe (p < 0.05).

TABLE 3.

Summary of EC50 values and Hill coefficients predicted using Hill equation for the WT and mutant CaSRs

HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with the WT CaSR or Ca2+ binding-related CaSR mutants, and after 48 h the cells were loaded with Fura-2 as described under “Materials and Methods.” The cells on glass coverslips were then transferred into the cuvette for fluorimetry and exposed to various increases in [Ca2+]o (from 0.5 to 30 mm) in the absence or presence of 5 mm l-Phe as described above. The average of [Ca2+]i at each [Ca2+]o was plotted against [Ca2+]o and further fitted using the Hill equation, which gave EC50 and Hill numbers. The maximum response for each mutant was subtracted from the baseline and normalized to the maximal cumulative [Ca2+]i response of the WT receptor. The data were obtained from three experiments for each construct.

| Sites | Mutants | Response at 30 mm [Ca2+] |

EC50 [Ca2+]o |

Hill coefficient |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without l-Phe | With l-Phe | Without l-Phe | With l-Phe | Without l-Phe | With l-Phe | ||

| WT | 100.0 ± 2.0 | 104.6 ± 2.9 | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.2a | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 4.0 ± 0.4a | |

| Site 1 | E297I | 78.0 ± 6.9b | 132.8 ± 1.9a | Phase 1: 3.2 ± 0.4 | 7.4 ± 0.6a | Phase 1: 2.8 ± 0.2 | 4.2 ± 0.3a |

| Phase 2: 17.8 ± 0.5 | Phase 2: 3.5 ± 0.1 | ||||||

| Site 2 | D215I | 88.0 ± 2.5b | 147.5 ± 6.0a | 14.7 ± 1.9b | 9.0 ± 0.5a | 2.0 ± 0.2b | 2.8 ± 0.3a |

| Site 3 | E224I | 83.2 ± 5.2b | 104.2 ± 4.5a | 5.3 ± 0.4b | 3.1 ± 0.1a | 1.9 ± 0.1b | 4.3 ± 0.2a |

| Site 4 | E353I | 80.7 ± 1.6b | 88.9 ± 1.8a | 4.0 ± 0.1b | 2.6 ± 0.1a | 2.3 ± 0.1b | 3.6 ± 0.1a |

| Site 5 | D398A/E399I | 80.9 ± 7.0b | 78.3 ± 6.5 | 4.7 ± 0.7b | 3.3 ± 0.1b | 2.4 ± 0.1b | 3.6 ± 0.4a |

a Indicates significance with respect to the corresponding mutants in the absence of l-Phe (p < 0.05).

b Indicates significance with respect to wild type CaSR in the absence of l-Phe (p < 0.05).

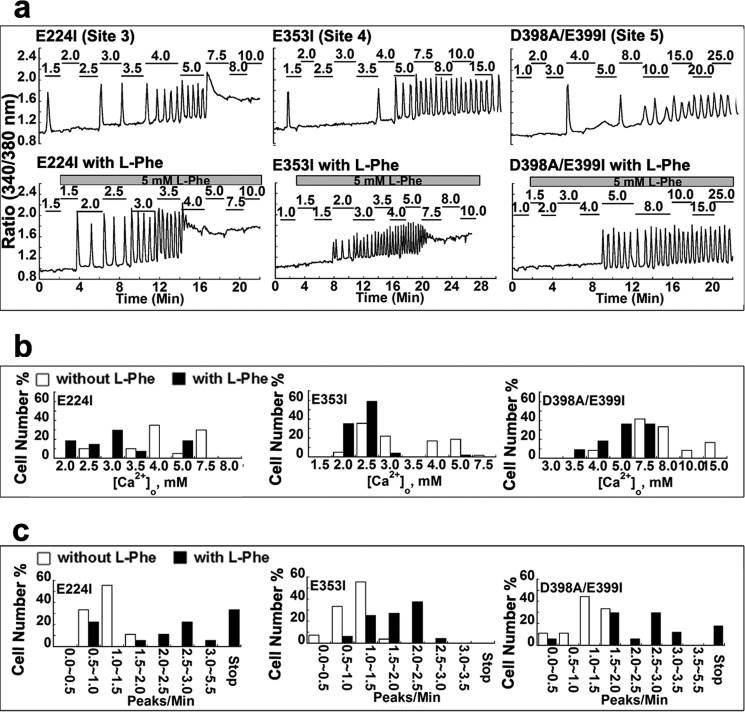

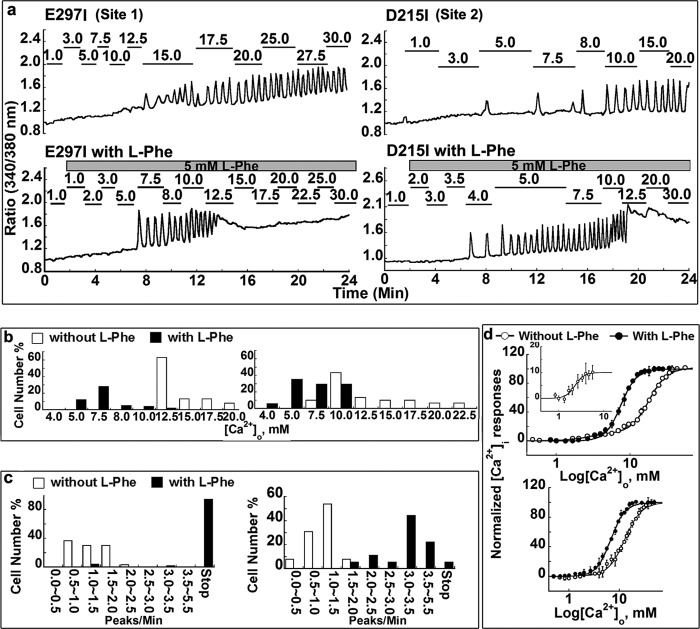

FIGURE 4.

Individual cellular responses of mutants in calcium-binding sites to the indicated increments of [Ca2+]o in the presence or absence of l-Phe. a, representative intracellular calcium response from a single cell. Fura-2-loaded HEK293 cells expressing CaSR with mutations in calcium-binding site 3, 4, or 5 were prepared for single-cell experiments. Each experiment with or without 5 mm l-Phe began in the same non-calcium-containing Ringer buffer followed by stepwise increases in [Ca2+]o as indicated above the oscillation pattern using a perfusion system until [Ca2+]i reached a plateau (up to 30 mm [Ca2+]o). At least 30 cells were analyzed for each mutant. b, frequency distribution of the [Ca2+]o at which CaSR-transfected single HEK293 cells started to oscillate. The cell number percentage is defined as the number of cells starting to oscillate at a given [Ca2+]o/total cell number showing oscillation pattern × 100. Empty bar, in the absence of l-Phe; black bar, in the presence of 5 mm l-Phe. c, the frequency distribution of the oscillation frequency from single cells was investigated as described before. For experiments without l-Phe, the number of peaks/min was recorded at the level of [Ca2+]o at which the majority of the cells (>50%) started to oscillate; for experiments with 5.0 mm l-Phe, the frequency was analyzed at the same [Ca2+]o that was used in the absence of l-Phe. Specifically, the frequency of E224I was studied at 4 mm [Ca2+]o; E353I was analyzed at 5.0 mm [Ca2+]o; and D398A/E399I was investigated at 10.0 mm [Ca2+]o. Empty bar, in the absence of l-Phe; black bar, in the presence of 5 mm l-Phe.

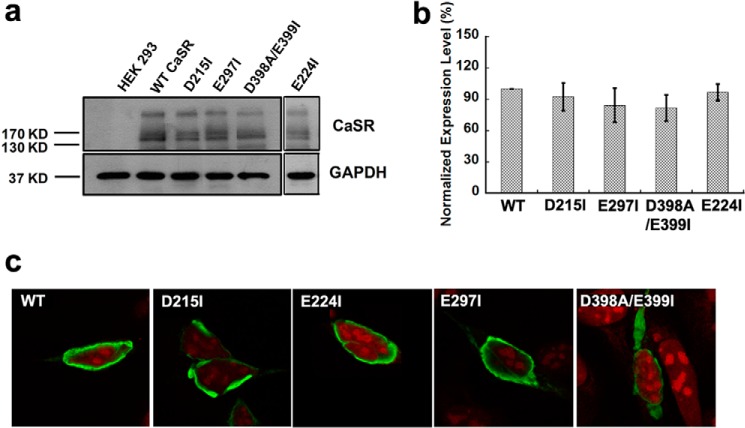

FIGURE 5.

Expression of WT CaSR and its mutants in HEK293 cells. a, Western blot analyses of CaSR and its mutants in transiently transfected HEK293 cells. 40 μg of total protein from cellular lysates were subjected to 8.5% SDS-PAGE. Three characteristic bands are shown in the upper panel, including the top band representing the dimeric receptor, the middle band showing mature glycosylated CaSR monomer (150 kDa), and the lowest band indicating immature glycosylated CaSR monomer (130 kDa). b, quantification of the expression of WT CaSR and its mutants in HEK293 cells. All the bands, including the one indicating dimeric receptor, mature glycosylated monomer and the one showing immature CaSR monomer, were taken into consideration. The internal control GAPDH was used to standardize CaSR expression, and the mutants were further normalized to the WT CaSR expression. c, immunofluorescence analyses of surface expressed WT CaSR and its mutants in HEK293 cells. Immunostaining was done with anti-CaSR monoclonal antibody ADD (70), and detection was carried out with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated, goat anti-mouse secondary antibody. Red, propidium iodide staining of cell nuclei; green, CaSR. Equivalent expression of WT CaSR as well as its variants on the cell surface suggests that the difference in the Ca2+ sensing capabilities among the WT and mutant receptors are due to perturbation of the functions of cell surface receptors, rather than, for example, impaired trafficking of the receptor proteins to the cell surface.

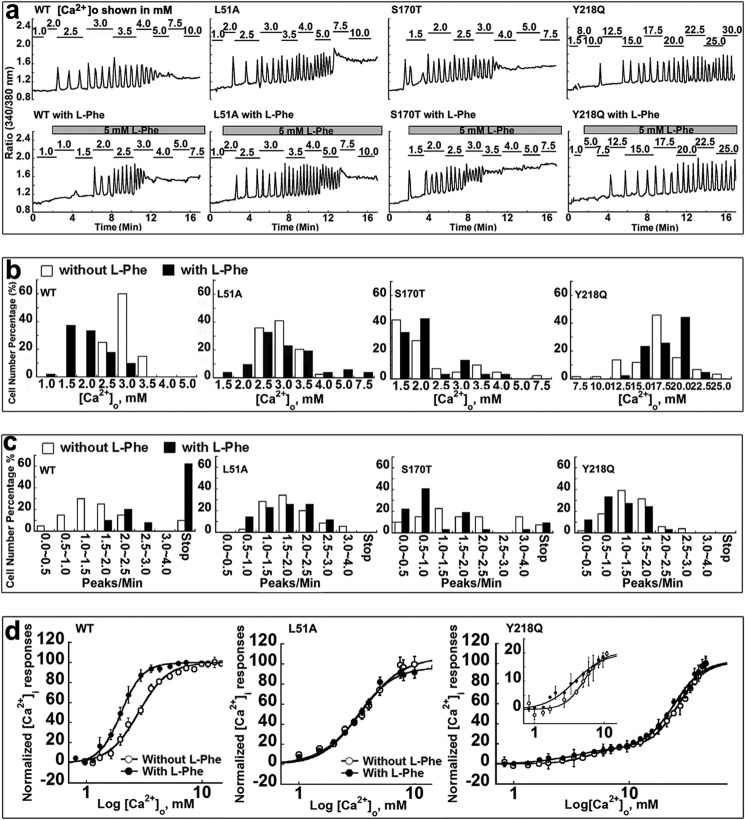

FIGURE 6.

Functional studies of receptors with mutations in l-Phe-binding site in HEK293 cells. a, representative oscillation pattern from a single cell. Each experiment with or without 5 mm l-Phe began in Ca2+-free Ringer buffer followed by stepwise increases in [Ca2+]o until [Ca2+]i reached a plateau (up to 30 mm [Ca2+]o). b, the pattern of [Ca2+]i responses in each cell (minimum of 30 cells) was analyzed, and the [Ca2+]o at which individual cells started to oscillate was recorded and plotted as a bar chart. c, the frequency of the oscillation patterns of the individual cells was investigated. For experiments without l-Phe, the number of peaks/min was recorded at the level of [Ca2+]o at which the majority of the cells (>50%) started oscillating, although for experiments with 5 mm l-Phe, the frequency was analyzed at the same levels of [Ca2+]o as in the corresponding experiments carried out without l-Phe. d, population assay for [Ca2+]i responses of HEK293 cells transiently overexpressing WT CaSR or CaSR mutants L51A or Y218Q using Fura-2 AM during stepwise increases in [Ca2+]o from 0.5 to 30 mm. The ratio of the intensity of light emitted at 510 nm upon excitation with 340 or 380 nm was normalized to its maximum response. The [Ca2+]o concentration response curves were fitted using the Hill equation.

Functional Positive Heterotropic Cooperativity Contributed by the Identified l-Phe-binding Site

Fig. 6a shows the effect of 5 mm l-Phe on the [Ca2+]i responses at different levels of [Ca2+]o in HEK293 cells transiently transfected with the WT CaSR or its variants with mutations around the predicted l-Phe-sensing site. l-Phe lowered the threshold for [Ca2+]o-induced oscillations in the WT CaSR from 3.0 ± 0.1 to 2.0 ± 0.2 mm, a 1.5-fold decrease (Fig. 6a and Table 2). Concurrently, l-Phe also increased the oscillation frequency from 1.5 ± 0.1 to 2.2 ± 0.2 peaks/min (n>30, p < 0.05) in the presence of 3.0 mm [Ca2+]o in the single-cell assay (Fig. 6c and Table 2). Meanwhile, l-Phe produced functional positive heterotropic cooperativity of the receptor, because it facilitated the response of the WT CaSR to [Ca2+]o by significantly decreasing the EC50 from 2.9 ± 0.2 to 1.9 ± 0.2 mm (n = 3, p < 0.05) and increasing the Hill coefficient from 3.0 to 4.0 in the cell population assay (Fig. 6d and Table 3).

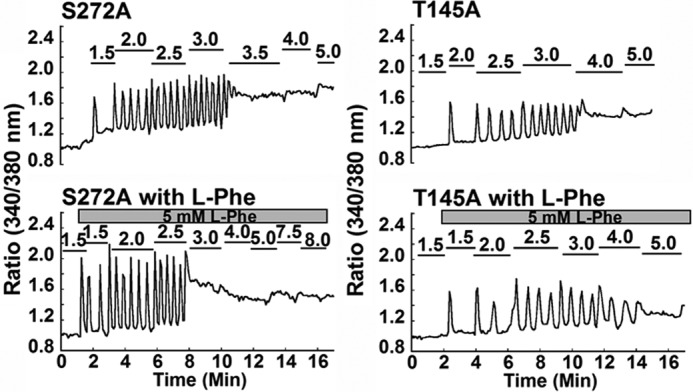

We then performed detailed analyses to understand the role of residues in the modeled l-Phe-binding site in the functional positive heterotropic cooperativity contributed by l-Phe (Fig. 6 and Table 4). Five of 12 residues located within 5 Å of the modeled l-Phe-binding site exhibited impaired l-Phe-sensing ability. Mutants L51A and S170T exhibited impaired l-Phe sensing capability as indicated by the absence of any change in the starting point (Fig. 6b) as well as constant oscillatory frequencies (∼1.7 and 1.4 peaks/min) in the presence of l-Phe (Fig. 6c), whereas they maintained relatively unaltered calcium-sensing functions. Consistent with the single-cell assay results, cell population studies revealed that the EC50 values of L51A, S170T, and Y218Q remained the same with or without l-Phe (Fig. 6d) (the effect of l-Phe on S170T has previously been reported by Zhang et al. (51) in a cell population assay). The addition of 5 mm l-Phe lowered the [Ca2+]o required to initiate oscillations in cells transfected with mutations S272A or T145A but failed to increase the oscillatory frequency at 2.5 mm [Ca2+]o (the level at which the majority of the cells began to oscillate), nor did it reduce the EC50 (Table 4 and Fig. 7). Tyr218 is predicted to be involved in binding of both l-Phe in its binding pocket and of Ca2+ in site 1. Indeed, the mutation Y218Q largely disrupted the functional positive homotropic cooperativity with transformation of the single cooperative response to [Ca2+]o of the WT CaSR to a biphasic process in the cell population assay. Y218Q also exhibited less sensitivity to [Ca2+]o, because [Ca2+]i oscillations did not start until [Ca2+]o was increased to more than 10 mm, reflecting its role in this Ca2+-binding site. Of note, however, addition of 5 mm l-Phe failed to restore the calcium sensitivity of this mutant as manifested by an unchanged oscillation pattern. An oscillation frequency of ∼1.5 peaks/min was observed at 20 mm [Ca2+]o both with and without l-Phe for this mutant. In contrast, mutations such as K47A, Y63I, W70L, G146A, I162A, S169A, I187A, H413L, and R415A did not abrogate the positive allosteric effect of 5 mm l-Phe (Table 5). Taken together, these results suggest that residues located at the predicted l-Phe-binding site, including Leu51, Thr145, Ser170, Ser272, and Tyr218, play key roles in sensing l-Phe.

TABLE 4.

Summary of cellular responses of HEK293 cells transiently transfected with WT CaSR or mutants in the predicted l-Phe-binding site

The average [Ca2+]o at which cells started [Ca2+]i oscillations was recorded using the aforementioned methods for WT or each mutant CaSR. For the oscillation frequency in the absence of l-Phe, peaks/min were measured at the level of [Ca2+]o at which more than 50% cells started to oscillate; when l-Phe was added, frequencies were recorded at the same [Ca2+]o as their counterparts without l-Phe. Specifically, the frequencies of WT and L51A were measured at 3.0 mm [Ca2+]o, whereas S272A, T145A, and S170T were measured at 2.5 mm [Ca2+]o, and Y218Q was analyzed at 15.0 mm [Ca2+]o. The values are means ± S.E. EC50 and Hill numbers were obtained from the cell population assay by fitting plots using the Hill equation.

| Mutant | Starting point |

Frequency |

EC50 |

Hill number |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without l-Phe | With l-Phe | Without l-Phe | With l-Phe | Without l-Phe | With l-Phe | Without l-Phe | With l-Phe | |

| mm | peaks/min | mm | ||||||

| WT | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0.2a | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.2a | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.2a | 3.2 ± 0.3 | 4.1 ± 0.1a |

| L51A | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 3.5 ± 0.2 | 3.2 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 2.8 ± 0.2 |

| T145A | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.2a | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 3.3 ± 0.3 | 3.7 ± 0.4 |

| S170T | 2.1 ± 0.2b | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 2.2 ± 0.1 |

| Y218Q | 17.7 ± 1.0b | 16.7 ± 2.2 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | Phase 1: 3.7 ± 0.4 | Phase 1: 3.6 ± 0.2 | Phase 1: 3.8 ± 1.0 | Phase 1: 3.9 ± 0.4 |

| Phase 2: 27.1 ± 0.8 | Phase 2: 24.6 ± 0.5 | Phase 2: 3.4 ± 0.5 | Phase 2: 2.8 ± 0.8 | |||||

| S272A | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.1a | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.1 |

a Significant difference between cases without l-Phe and with 5 mm l-Phe (p < 0.05).

b Significant difference between mutant receptor and WT CaSR without l-Phe (p < 0.05).

FIGURE 7.

Individual cellular responses of mutants in the l-Phe-sensitive site to the indicated increments of [Ca2+[rsqb]o in the presence or absence of l-Phe. HEK293 cells transfected with wild type CaSR or mutants were loaded with Fura-2 AM for 15 min. Each experiment with or without 5 mm l-Phe began in the same non-calcium-containing Ringer buffer followed by stepwise increases in [Ca2+]o until [Ca2+]i reached a plateau (up to 30 mm) as monitored by changes in the ratio of light emitted at 510 nm following excitation at 340 or 380 nm. At least 30 cells were analyzed for mutants S272A and T145A. Representative cellular responses from a single cell are shown.

TABLE 5.

Summary of cellular responses from HEK293 cells transiently transfected with WT CaSR or mutants in the predicted l-Phe-sensing site

The intracellular calcium responses of HEK293 cells transiently overexpressing WT CaSR or various mutants potentially involved in the interaction with l-Phe were measured using Fura-2 AM during stepwise increases in [Ca2+]o. The pattern of [Ca2+]i responses in each cell (minimum of 30 cells) was analyzed, and the [Ca2+]o at which individual cells started to oscillate was recorded. For experiments without l-Phe, the number of peaks/min was recorded at the level of [Ca2+]o at which the majority of the cells (>50%) started oscillating, whereas for experiments with 5 mm l-Phe, the frequency was analyzed at the same levels of [Ca2+]o as in the corresponding experiments carried out without l-Phe. Specifically, WT, K47A, G146A, S169A, and H413L were measured at 3.0 mm [Ca2+]o; Y63I and R415A were measured at 3.5 mm [Ca2+]o; I187A was measured at 10.0 mm [Ca2+]o; and W70L and I162A were measured at 12.5 mm [Ca2+]o. The average fluorescence intensity ratio at each increase in the level of [Ca2+]o was plotted against [Ca2+]o and fitted using the Hill equation, which gave EC50 and Hill numbers. The values are means ± S.E. NA, not available.

| Mutant | Starting point |

Frequency |

EC50 |

Hill number |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without l-Phe | With l-Phe | Without l-Phe | With l-Phe | Without l-Phe | With l-Phe | Without l-Phe | With l-Phe | |

| mm | Peaks/min | mm | ||||||

| WT | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0.2a | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.2a | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.2a | 3.2 ± 0.3 | 4.1 ± 0.1a |

| K47A | 2.4 ± 0.1b | 1.9 ± 0.1a | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 2.8 ± 0.2a | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.1a | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 3.6 ± 0.2a |

| Y63I | 3.3 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.2a | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.2a | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.1a | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 3.6 ± 0.2a |

| W70L | 13.9 ± 1.0b | 9.2 ± 0.3a | 2.7 ± 0.2 | 3.1 ± 0.2a | 8.2 ± 0.3 | 7.8 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 3.7 ± 0.2a |

| G146A | 2.5 ± 0.1b | 1.9 ± 0.1a | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 2.9 ± 0.2a | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.1a | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 3.3 ± 0.1 |

| I162A | 13.0 ± 1.2b | 9.6 ± 0.3a | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 2.5 ± 0.2a | 7.9 ± 0.4 | 11.3 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.1 |

| S169A | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 2.3 ± 0.1a | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 0.2a | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.1a | 3.3 ± 0.1 | 3.9 ± 0.1 |

| I187A | 8.1 ± 0.4b | 3.4 ± 0.1a | 1.8 ± 0.1 | NA | 9.0 ± 0.3 | 3.4 ± 0.1a | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 2.6 ± 0.1a |

| H413L | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.1a | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 2.1 ± 0.1a | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.1a | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 3.6 ± 0.1 |

| R415A | 3.5 ± 0.3 | 2.8 ± 0.2a | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 2.6 ± 0.3a | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.1a | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 3.4 ± 0.1a |

a Significant difference between cases without l-Phe and with 5 mm l-Phe (p < 0.05).

b Significant difference between mutant receptor and WT CaSR without l-Phe (p < 0.05).

Global Functional Positive Heterotropic Cooperative Tuning by l-Phe of the Positive Homotropic Cooperative Response of CaSR to [Ca2+]o

The sensing of l-Phe at the hinge region adjacent to site 1 has marked global (i.e., extending widely over the ECD) effects on the five predicted Ca2+-binding sites predicted earlier, which are spread over several different locations in the CaSR ECD. Interestingly, addition of 5 mm l-Phe significantly rescued the [Ca2+]i responses of the two mutants, E297I and D215I, in sites 1 and 2, respectively, that exhibited disrupted cooperativity. Notably, l-Phe converted the biphasic Ca2+-response curve for E297I back to a uniphasic curve (Fig. 8). Fig. 8 shows that their starting points for [Ca2+]o-initiated oscillations were reduced from 17.0 ± 0.4 to 7.3 ± 0.2 mm (E297I) and from 13.9 ± 0.2 to 6.7 ± 0.3 mm (D215I), respectively, in the presence of l-Phe (Table 2). Both of the mutants exhibited more than 2-fold shifts in their starting points in the presence of l-Phe. The frequencies of their oscillations increased to more than 2 peaks/min in both cases compared with the frequencies without l-Phe (Fig. 8c and Table 2). Similarly, the addition of l-Phe decreased their EC50 values in the cell population assay (Table 3).

FIGURE 8.

[Ca2+[rsqb]i responses of CaSRs with mutations in the Ca2+-binding sites stimulated by increasing [Ca2+]o in the presence or absence of 5 mml-Phe. a, [Ca2+]i was monitored in mutants E297I and D215I in the absence or presence of l-Phe. [Ca2+]o was increased stepwise up to 30 mm or until [Ca2+]i reached a plateau. b, frequency distribution of [Ca2+]o at which CaSR-transfected single HEK293 cells started to oscillate. c, in the single-cell experiments, the frequency of the oscillation patterns was investigated in more than 30 cells. For experiments without l-Phe, the number of peaks/min was recorded at the level of [Ca2+]o at which the majority of the cells (>50%) started to oscillate, whereas for experiments with 5 mm l-Phe, the frequency was analyzed at the corresponding level of [Ca2+]o that was studied in the absence of l-Phe. Empty bar, in the absence of l-Phe; black bar, in the presence of 5 mm l-Phe. d, population assay for measuring [Ca2+]i responses of HEK293 cells transiently transfected with Ca2+-binding site-related CaSR mutants using Fura-2 AM during stepwise increases in [Ca2+]o from 0.5 to 30 mm. [Ca2+]i responses were further fitted using the Hill equation. Inset in top panel of d, zoomed in view of the binding first phase.

Mutant E224I at site 3 exhibited increases in the [Ca2+]o required to initiate [Ca2+]i oscillations but manifested smaller changes (from 3.0 ± 0.1 to 5.0 ± 0.2 mm [Ca2+]o (n > 30, p < 0.05), compared with the previous two mutants. Moreover, its elevated EC50 value obtained in the population study correlated well with results from the single-cell study (Tables 2 and 3), suggesting an impaired ability of this mutant to sense [Ca2+]o. However, addition of l-Phe not only significantly decreased the level of [Ca2+]o required for initiating oscillations but also increased the oscillation frequency measured at the same level of [Ca2+]o. Furthermore, the population assay showed that the EC50 was reduced, and the maximum response was rescued by 5 mm l-Phe.

Glu353 is part of Ca2+-binding site 4 in lobe 2, whereas Asp398 and Glu399 are involved in site 5 (26). Table 3 and Fig. 4 show that removal of these negatively charged residues at sites 4 and 5 increased the level of [Ca2+]o required to initiate [Ca2+]i oscillations and also the receptors' EC50 values of the mutant receptors. l-Phe at 5 mm was able to enhance the sensitivity of these mutants to [Ca2+]o and decrease their EC50 values. Therefore, as shown in Table 2, not only Ca2+-binding residues adjacent to the predicted l-Phe-binding site (e.g., sites 1 and 2) but also sites farther away from the hinge region exhibited l-Phe-induced decreases in EC50 and starting point as well as increases in oscillation frequency and Hill coefficient. This result suggests the global nature of the functional positive heterotropic cooperative interaction between l-Phe and extracellular Ca2+.

The Ensemble of Conformations of Calcium- and l-Phe-loaded CaSR ECD Is Distinguishable from the Nonloaded Forms

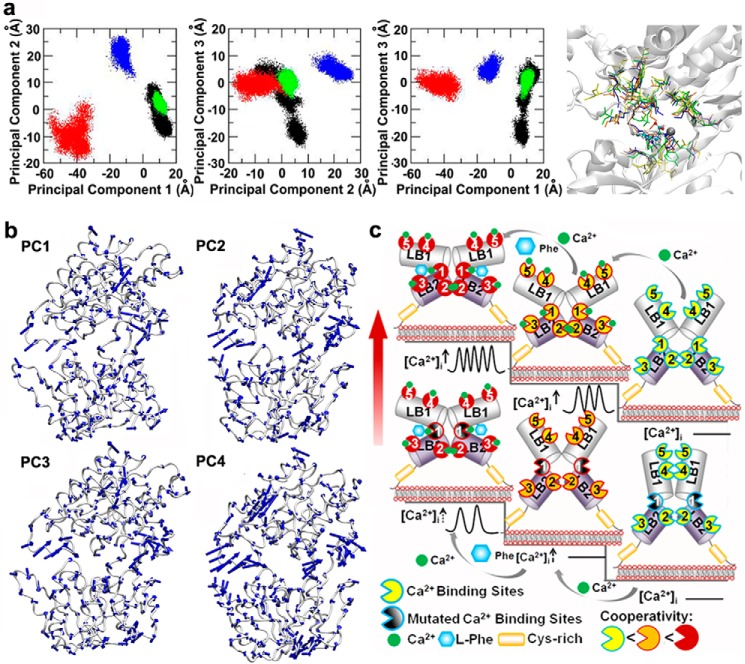

To provide a more detailed description of the CaSR mechanism of action at the atomic level, we again used MD simulations to analyze the trajectories of these simulations using PCA (“Materials and Methods”), which separates out the protein motions into principal modes ranked according to their relative contributions (41). Projection of the trajectories of the different states of CaSR onto the first three modes, which accounted for the majority of the total fluctuations, is shown in Fig. 9a. The conformations sampled by the Ca2+-free and l-Phe-free forms of the CaSR are distinctly different from those sampled by the Ca2+-loaded and Ca2+- and l-Phe-loaded forms of the receptor. Interestingly, the conformations of the l-Phe-loaded and the free forms of CaSR are essentially indistinguishable, as can be seen in Fig. 9a. The results suggest that [Ca2+]o shifts the population of conformational ensembles of CaSR to a semiactive ensemble that can subsequently be shifted to an ensemble of more active conformations upon interaction of the receptor with l-Phe. These results are consistent with the experiments described above and suggest that the unbound CaSR does not respond to l-Phe alone, because l-Phe cannot effectively shift the inactive conformations to an active ensemble of conformations. The above results do not rule out the role of conformational selection, which implies the existence of all relevant active and inactive conformations of the receptor before binding, in the mechanism of activation of CaSR, but clearly indicate that the ensembles of active and inactive conformations are distinctly different and that [Ca2+]o alone and/or [Ca2+]o and l-Phe together are required to shift the population, in agreement with previously well documented experimental results that l-Phe could not activate CaSR at subthreshold levels of [Ca2+]o (below ∼1.0 mm in CaSR-transfected HEK293 cells) (58).

FIGURE 9.

PCA of CaSR ECD, combined with experimental data, suggest a model for the mechanism underlying activation of the CaSR by extracellular Ca2+ and l-Phe. a, PCA of CaSR ECD. The trajectories of the molecular dynamics simulations were analyzed using PCA, which separates out the motions of the CaSR ECD into principal modes ranked according to their relative contributions. The first three principal modes were included in the present study to analyze four different states of the protein: ligand-free (black), presence of l-Phe-only (green), presence of Ca2+-only (red), or presence of both Ca2+ and l-Phe (blue). The superposition of the last snapshots of the aforementioned simulation systems is shown in the right panel. Ca2+ is shown as the black sphere; residues involved in Ca2+-binding site 1 are shown in bond representation; l-Phe is shown as a ball and stick model. b, representations of the four slowest principal components of the ECD of CaSR using the eigenvectors mapped onto the backbone C atoms of CaSR. The directions of the eigenvectors indicate the bending and twisting motions of the ECD of CaSR. c, model for the mechanism underlying activation of the CaSR by extracellular Ca2+ and l-Phe. Ca2+ and l-Phe modulate the activity as well as the cooperativity of CaSR (the color changes of the calcium binding sites from yellow to red indicates an increase in cooperativity). Higher [Ca2+]o, ∼3.0 mm, could change the conformation of CaSR into an active form (second stair level) in a positive homotropic cooperative manner (as indicated by the change of the color of the Ca2+-binding sites from yellow to orange) and further trigger [Ca2+]i oscillations. l-Phe binds to the hinge region between lobe 1 and lobe 2, modulating the receptor together with Ca2+ in a positive heterotropic cooperative way (as indicated by the change in the color from orange to red). This could produce a conformation of the receptor that is a “superactivated” form (third stair level) associated with a higher frequency of [Ca2+]i oscillations and a left-shifted EC50. CaSR mutants (lower activity stair level), especially those containing mutations close to the hinge region between lobe 1 (LB1) and lobe 2 (LB2) (show in black truncated circle), could cause a disruption of the cooperativity among the various Ca2+-binding sites (lower level, middle stair). [Ca2+]o at 3.0 mm does not trigger [Ca2+]i oscillations in the mutant CaSR. The impaired receptor function and the cross-talk between Ca2+-binding sites can be rescued, at least in part, by introducing l-Phe into the extracellular buffer (lower level, left stair). Red arrow, receptor activity.

Based on all the experimental results and the directions of the eigenvectors from the long time simulation (Fig. 9b), we propose a model to illustrate the possible mechanism by which Ca2+ and l-Phe regulate the function of the CaSR mainly through the molecular connectivity encoded at the hinge region of the ECD of the protein. Our model (Fig. 9c) suggests that a local conformational change upon interaction of the CaSR with l-Phe might affect the overall conformation of the receptor, thereby influencing the cooperativity between multiple Ca2+-binding sites and enhancing the overall response of the receptor to Ca2+.

DISCUSSION

Several major barriers have hampered our understanding of how CaSR integrates its activation by two different classes of nutrients, divalent cations and amino acids, to regulate the functional cooperativity of the receptor and of the alterations of this cooperativity caused by disease mutations. These include “invisible” binding pockets for these two key physiological agonists of the CaSR, namely Ca2+ and amino acids, challenges in obtaining structural information associated with membrane proteins, and the lack of direct binding methods in determining the mechanism underlying cooperative activation of the CaSR by Ca2+ and amino acids (13, 19, 59). To overcome these limitations, we have developed several computer algorithms and a grafting approach for identifying and predicting Ca2+-binding sites in proteins, and we have successfully verified the intrinsic Ca2+-binding capabilities of predicted Ca2+-binding sites in the CaSR and mGluR1α (25–27, 60).

Our studies, shown in Figs. 1, 3, and 6, suggest that mutations in Ca2+-binding site 1, such as E2971 and Y218Q, not only disrupt the Ca2+ sensing capacity of CaSR but also have an impact on the positive homotropic cooperative interactions of Ca2+ with the other Ca2+-binding sites. The biphasic behavior of these mutants with a large disruption of cooperativity is very similar to our previously reported metal-binding concentration response curves of subdomain 1 and its variants with increases in [Ca2+]o (26). Subdomain 1 of CaSR contains a protein sequence encompassing Ca2+-binding sites 1, 2, and 3, but not Ca2+-binding sites 4 and 5. It also exhibits both strong and weak metal-binding components. This strong metal-binding process can be removed by further mutating site 1 (E297I). In contrast, mutations at sites 2 and 3 in subdomain 1 have less impact on the first binding process (26). These experimental results are consistent with molecular dynamics simulation studies carried out here showing that residues located at site 1 have strong correlated motions with other residues involved in sites 2, 3, 4 and 5 (Table 1). The results suggest that the dynamics of site 1 are intricately coupled to those of the other binding sites; therefore, any changes in the dynamics of site 1 could affect those of the other sites. The observation of this molecular connectivity and its relationship to positive cooperativity from the molecular dynamics simulations provides a description at the atomic level of the cross-talk between the different sites of the CaSR suggested by the experimental results in live cells.

Here, we have also identified and characterized an l-Phe-binding pocket formed by residues Leu51, Ser170, Thr145, Tyr218, and Ser272 that is adjacent to and partially overlaps the key Ca2+-binding site 1 at the hinge region of the Venus flytrap of the CaSR. This Ca2+-binding site is also conserved in other family C GPCRs, including the mGluR1 Venus flytrap (Fig. 2) (27, 31, 56). Tyr218 is involved in sensing both Ca2+ and l-Phe. The aromatic ring from residue Tyr218 could form delocalized pi bonds with the side chain of l-Phe and the hydrophobic interaction between Leu51 and l-Phe would further stabilize this interaction. Mutating Ser170 might interfere with H-bonding of the ligated amino acid to the α-amino group of Ser170 based on the structure of mGluR1α (53). S170T has been reported by different groups to interfere with the l-Phe sensing ability of CaSR (51, 53). Consideration of the crystal structure of the glutamate-bound form of mGluR1 (31), together with our docking analysis, implies that residues Thr145 and Ser272 may not directly participate in the interaction with l-Phe but could possibly interact with l-Phe by ligation of water molecules, which is a relatively weaker type of interaction.

We have observed essentially equivalent expression of WT CaSR as well as its variants on the cell surface (Fig. 5). These data suggest that the difference in the Ca2+ sensing capacities among the WT and mutant receptors are due to perturbation of the cell surface receptor functions rather than, for example, impaired trafficking of the receptor proteins to the cell surface. l-Phe rescued the calcium responses of the tested mutants located in all five predicted Ca2+-binding sites, and it had more dramatic rescuing effects on mutants E297I and D215I compared with the other mutants (Fig. 8d). Thus, the importance of the hinge region, where l-Phe likely interacts with the CaSR ECD, is once again highlighted.

The PCA results suggest that the need for Ca2+ in initially activating CaSR, as suggested by these experiments, is related to shifting the ensemble of conformations of CaSR from an inactive state to an active state. The activity of the Ca2+-loaded form of CaSR is then further enhanced by the binding of l-Phe, which produces an additional change in the ensembles of conformations of CaSR. Therefore, the global modulation of receptor activity by Ca2+ and l-Phe might be explained by a combination of an induced fit and population shift models (61); that is, the overall structure of the receptor could vary in the equilibrium distributions of conformations that can interchange dynamically in the absence of Ca2+ and l-Phe. Our experimental results suggest that binding of Ca2+ at its various sites is associated with motions of these sites that are highly correlated with one another. Consequently, the shift in the ensemble of conformations of CaSR induced by the initial binding of Ca2+ at site 1 will alter the equilibrium population of the unbound conformations of other Ca2+-binding sites because of their cross-talk with site 1. The binding of Ca2+ to site 1 and the subsequent interaction of CaSR with l-Phe can further shift the conformations of the ECD from one part of the free energy landscape to another. In this way, Ca2+ binding to other sites is more readily favorable. Our findings here also enhance our understanding of the role of Ca2+ in modulating key Ca2+-binding proteins, such as calmodulin, to mediate signal transduction via correlated motions among their multiple Ca2+-binding sites, thereby generating cooperative responses with critical biological consequences (62, 63).

The coactivation of CaSR by these two classes of ligands may be particularly important in the gastrointestinal tract, where high concentrations of amino acids resulting from protein digestion would promote activation of the CaSR and its stimulation of digestive processes even when there are relatively low levels of [Ca2+]o. Moreover, as reported in clinical studies, there are 33 disease-related variants near Ca2+-binding site 1 associated with receptor activation or inactivation and, in some cases, with reduced cooperativity (15). Our work suggests that it is likely that such mutations disrupt the molecular connectivity encoded in the receptor and provide a better understanding of the molecular basis of some of the CaSR-related clinical disorders. Although the circulating levels of Ca2+ and l-Phe in vivo are lower than in the in vitro experiments, the discrepancy noted here (2–3-fold for the WT receptor for Ca2+) is substantially less than variety of more classical hormone receptor systems. For the cloned parathyroid hormone receptor, for example, the Kd values for activation of adenylate cyclase and stimulation of PLC, are 1 and 20–50 nm, respectively, whereas the normal circulating levels of parathyroid hormone are ∼1–7 pm, i.e., resulting in a >100-fold discrepancy to even a >1,000-fold discrepancy between in vivo and in vitro results (64). Our finding of the capacity of l-Phe to rescue disease-linked mutations suggests the possibility of enhancing the activities of such mutant receptors using calcimimetics of various types as pharmacotherapy. Thus, our results provide insights into key factors regulating the overall activity of the receptor, which can lay the foundation for a new generation of therapeutics and drugs.

In addition to the Ca2+-sensing receptor, [Ca2+]o regulates 14 of the other members of the family C GPCRs, including the mGluRs, GABAB receptors, and receptors for pheromones, amino acids, and sweet substances (1, 5, 10, 16, 54–56, 65). The observed molecular connectivity centered at predicted calcium-binding site 1 of the CaSR, which is adjacent to an amino acid-binding pocket at the hinge region of the receptor, may be shared by other members of the family C GPCRs (66, 67). In addition to the strong conservation of the predicted calcium-binding site 1 and the adjacent amino acid-binding pocket, several lines of evidence support this suggestion (Fig. 2) (25, 26, 56, 68). We have predicted a Ca2+-binding site partially sharing a Glu-binding site in the ECD of mGluR1α, and both of them coactivate the receptor (27). A Ca2+-binding pocket was proposed to be present in the ligand-binding site of the GABAB receptor (55). Many animals and humans can detect the taste of calcium via a calcium taste receptor that is modulated by an allosteric mechanism (69).

In summary, our present study provides a mechanistic view of the interplay among extracellular Ca2+, amino acids and the CaSR via molecular connectivity that modulates the positive homotropic and heterotropic cooperativity of CaSR-mediated intracellular Ca2+ signaling. The positive cooperative coactivation of the CaSR by Ca2+ and l-Phe and the importance of the positive homotropic and heterotropic cooperativity, respectively, exhibited by the two agonists may be further extended to other members of the family C GPCRs to facilitate understanding of the molecular basis for related human disorders and the development of new therapeutic strategies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Yubin Zhou, Dr. Michael Kirberger, Dr. Rajesh Thakker, Katheryn Lee Meenach, and Xiaojun Xu for critical review and assistance.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants GM081749 and EB007268 (to J. J. Y.). This work was also supported by National Science Foundation Grant MCB-0953061 (to D. H.), a Center for Diagnostics and Therapeutics (CDT) fellowship (to C. Z.), and funds from the Georgia Research Alliance.

- CaSR

- calcium-sensing receptor

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- ECD

- extracellular domain

- MD

- molecular dynamics

- PCA

- principal component analysis

- mGluR

- metabotropic glutamate receptor

- AM

- acetoxymethylester.

REFERENCES

- 1. Brown E. M., Gamba G., Riccardi D., Lombardi M., Butters R., Kifor O., Sun A., Hediger M. A., Lytton J., Hebert S. C. (1993) Cloning and characterization of an extracellular Ca2+-sensing receptor from bovine parathyroid. Nature 366, 575–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chang W., Shoback D. (2004) Extracellular Ca2+-sensing receptors. An overview. Cell Calcium 35, 183–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Breitwieser G. E. (2006) Calcium sensing receptors and calcium oscillations. Calcium as a first messenger. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 73, 85–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Huang C., Miller R. T. (2007) The calcium-sensing receptor and its interacting proteins. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 11, 923–934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wellendorph P., Bräuner-Osborne H. (2009) Molecular basis for amino acid sensing by family C G-protein-coupled receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 156, 869–884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cheng S. X., Geibel J. P., Hebert S. C. (2004) Extracellular polyamines regulate fluid secretion in rat colonic crypts via the extracellular calcium-sensing receptor. Gastroenterology 126, 148–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tu C. L., Oda Y., Komuves L., Bikle D. D. (2004) The role of the calcium-sensing receptor in epidermal differentiation. Cell Calcium 35, 265–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mathias R. S., Mathews C. H., Machule C., Gao D., Li W., Denbesten P. K. (2001) Identification of the calcium-sensing receptor in the developing tooth organ. J. Bone Miner. Res. 16, 2238–2244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Buchan A. M., Squires P. E., Ring M., Meloche R. M. (2001) Mechanism of action of the calcium-sensing receptor in human antral gastrin cells. Gastroenterology 120, 1128–1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hofer A. M., Brown E. M. (2003) Extracellular calcium sensing and signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 530–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brown E. M., MacLeod R. J. (2001) Extracellular calcium sensing and extracellular calcium signaling. Physiol. Rev. 81, 239–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dolmetsch R. E., Xu K., Lewis R. S. (1998) Calcium oscillations increase the efficiency and specificity of gene expression. Nature 392, 933–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Miedlich S., Gama L., Breitwieser G. E. (2002) Calcium sensing receptor activation by a calcimimetic suggests a link between cooperativity and intracellular calcium oscillations. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 49691–49699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Young S. H., Rozengurt E. (2002) Amino acids and Ca2+ stimulate different patterns of Ca2+ oscillations through the Ca2+-sensing receptor. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 282, C1414–C1422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hannan F. M., Nesbit M. A., Zhang C., Cranston T., Curley A. J., Harding B., Fratter C., Rust N., Christie P. T., Turner J. J., Lemos M. C., Bowl M. R., Bouillon R., Brain C., Bridges N., Burren C., Connell J. M., Jung H., Marks E., McCredie D., Mughal Z., Rodda C., Tollefsen S., Brown E. M., Yang J. J., Thakker R. V. (2012) Identification of 70 calcium-sensing receptor mutations in hyper- and hypo-calcaemic patients. Evidence for clustering of extracellular domain mutations at calcium-binding sites. Hum. Mol. Genet. 21, 2768–2778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hu J., Spiegel A. M. (2003) Naturally occurring mutations of the extracellular Ca2+-sensing receptor. Implications for its structure and function. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 14, 282–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hendy G. N., Guarnieri V., Canaff L. (2009) Calcium-sensing receptor and associated diseases. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 89, 31–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Francesconi A., Duvoisin R. M. (2004) Divalent cations modulate the activity of metabotropic glutamate receptors. J. Neurosci. Res. 75, 472–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Conigrave A. D., Quinn S. J., Brown E. M. (2000) l-Amino acid sensing by the extracellular Ca2+-sensing receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 4814–4819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang M., Yao Y., Kuang D., Hampson D. R. (2006) Activation of family C G-protein-coupled receptors by the tripeptide glutathione. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 8864–8870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Conigrave A. D., Mun H. C., Lok H. C. (2007) Aromatic l-amino acids activate the calcium-sensing receptor. J. Nutr. 137, (Suppl. 1) 1524S–1548S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Conigrave A. D., Brown E. M. (2006) Taste receptors in the gastrointestinal tract. II. l-amino acid sensing by calcium-sensing receptors. Implications for GI physiology. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 291, G753–G761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liou A. P., Sei Y., Zhao X., Feng J., Lu X., Thomas C., Pechhold S., Raybould H. E., Wank S. A. (2011) The extracellular calcium-sensing receptor is required for cholecystokinin secretion in response to l-phenylalanine in acutely isolated intestinal I cells. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 300, G538–G546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Broadhead G. K., Mun H. C., Avlani V. A., Jourdon O., Church W. B., Christopoulos A., Delbridge L., Conigrave A. D. (2011) Allosteric modulation of the calcium-sensing receptor by γ-glutamyl peptides. Inhibition of PTH secretion, suppression of intracellular cAMP levels, and a common mechanism of action with l-amino acids. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 8786–8797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Huang Y., Zhou Y., Yang W., Butters R., Lee H. W., Li S., Castiblanco A., Brown E. M., Yang J. J. (2007) Identification and dissection of Ca2+-binding sites in the extracellular domain of Ca2+-sensing receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 19000–19010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Huang Y., Zhou Y., Castiblanco A., Yang W., Brown E. M., Yang J. J. (2009) Multiple Ca2+-binding sites in the extracellular domain of the Ca2+-sensing receptor corresponding to cooperative Ca2+ response. Biochemistry 48, 388–398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jiang Y., Huang Y., Wong H. C., Zhou Y., Wang X., Yang J., Hall R. A., Brown E. M., Yang J. J. (2010) Elucidation of a novel extracellular calcium-binding site on metabotropic glutamate receptor 1α (mGluR1α) that controls receptor activation. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 33463–33474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Trott O., Olson A. J. (2010) AutoDock Vina. Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 31, 455–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sobolev V., Sorokine A., Prilusky J., Abola E. E., Edelman M. (1999) Automated analysis of interatomic contacts in proteins. Bioinformatics 15, 327–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Huang Y., Zhou Y., Wong H. C., Castiblanco A., Chen Y., Brown E. M., Yang J. J. (2010) Calmodulin regulates Ca2+-sensing receptor-mediated Ca2+ signaling and its cell surface expression. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 35919–35931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kunishima N., Shimada Y., Tsuji Y., Sato T., Yamamoto M., Kumasaka T., Nakanishi S., Jingami H., Morikawa K. (2000) Structural basis of glutamate recognition by a dimeric metabotropic glutamate receptor. Nature 407, 971–977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Case D. A., Darden T. A., Cheatham I., T. E., Simmerling C. L., Wang J., Duke R. E., Luo R., Crowley M., Walker R. C., Zhang W., Merz K. M., Wang B., Hayik S., Roitberg A., Seabra G., Kolossva′ry I., Wong K. F., Paesani F., Vanicek J., Wu X., Brozell S. R., Steinbrecher T., Gohlke H., Yang L., Tan C., Mongan J., Hornak V., Cui G., Mathews D. H., Seetin M. G., Sagui C., Babin V., Kollman P. A. (2008) AMBER 10, University of California, San Francisco [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jorgensen W. L., Chandrasekhar J., Madura J. D., Impey R. W., Klein M. L. (1983) Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 79, 926–935 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cornell W. D., Cieplak P., Christopher I. B., Gould I. R., Merz J. K., Ferguson D. M., Spellmeyer D. C., Fox T., Caldwell J. W., Kollman P. A. (1995) A second generation force field for the simulation of proteins, nucleic acids, and organic molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 5179–5197 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Urmi D., Hamelberg D. (2009) Reoptimization of the AMBER force field parameters for peptide bond (Omega) torsions using accelerated molecular dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. 113, 16590–16595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Darden T., York D., Pedersen L. (1993) Particle mesh Ewald. An N log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 10089–10092 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ryckaert J. P., Ciccotti G., Berendsen H. J. (1977) Numerical integration of the cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints. Molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. J. Comput. Phys. 23, 327–341 [Google Scholar]

- 38. Doshi U., Hamelberg D. (2012) Improved statistical sampling and accuracy with accelerated molecular dynamics on rotatable torsions. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 8, 4004–4012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hamelberg D., de Oliveira C. A., McCammon J. A. (2007) Sampling of slow diffusive conformational transitions with accelerated molecular dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 127, 155102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mongan J. (2004) Interactive essential dynamics. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 18, 433–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Levy R. M., Srinivasan A. R., Olson W. K., McCammon J. A. (1984) Quasi-harmonic method for studying very low frequency modes in proteins. Biopolymers 23, 1099–1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jolliffe I. T. (2002) Principal Component Analysis, Springer, New York [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bai M. (2004) Structure-function relationship of the extracellular calcium-sensing receptor. Cell Calcium 35, 197–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gama L., Wilt S. G., Breitwieser G. E. (2001) Heterodimerization of calcium sensing receptors with metabotropic glutamate receptors in neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 39053–39059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wang X., Kirberger M., Qiu F., Chen G., Yang J. J. (2009) Towards predicting Ca2+-binding sites with different coordination numbers in proteins with atomic resolution. Proteins 75, 787–798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Thakker R. V. (2004) Diseases associated with the extracellular calcium-sensing receptor. Cell Calcium 35, 275–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Monod J., Wyman J., Changeux J. P. (1965) On the nature of allosteric transitions. A plausible model. J. Mol. Biol. 12, 88–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Koshland D. E., Jr., Némethy G., Filmer D. (1966) Comparison of experimental binding data and theoretical models in proteins containing subunits. Biochemistry 5, 365–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ackers G. K. (1998) Deciphering the molecular code of hemoglobin allostery. Adv. Protein Chem. 51, 185–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Adcock S. A., McCammon J. A. (2006) Molecular dynamics. Survey of methods for simulating the activity of proteins. Chem. Rev. 106, 1589–1615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zhang Z., Qiu W., Quinn S. J., Conigrave A. D., Brown E. M., Bai M. (2002) Three adjacent serines in the extracellular domains of the CaR are required for l-amino acid-mediated potentiation of receptor function. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 33727–33735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mun H. C., Franks A. H., Culverston E. L., Krapcho K., Nemeth E. F., Conigrave A. D. (2004) The Venus fly trap domain of the extracellular Ca2+-sensing receptor is required for l-amino acid sensing. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 51739–51744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mun H. C., Culverston E. L., Franks A. H., Collyer C. A., Clifton-Bligh R. J., Conigrave A. D. (2005) A double mutation in the extracellular Ca2+-sensing receptor's Venus flytrap domain that selectively disables l-amino acid sensing. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 29067–29072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wise A., Green A., Main M. J., Wilson R., Fraser N., Marshall F. H. (1999) Calcium sensing properties of the GABA(B) receptor. Neuropharmacology 38, 1647–1656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Galvez T., Urwyler S., Prézeau L., Mosbacher J., Joly C., Malitschek B., Heid J., Brabet I., Froestl W., Bettler B., Kaupmann K., Pin J. P. (2000) Ca2+ requirement for high-affinity γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) binding at GABA(B) receptors. Involvement of serine 269 of the GABABR1 subunit. Mol. Pharmacol. 57, 419–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]