Abstract

Significance: Iron is the most abundant transition metal in biology and an essential cofactor for many cellular enzymes. Iron homeostasis impairment is also a component of peripheral neuropathies. Recent Advances: During the past years, much effort has been paid to understand the molecular mechanism involved in maintaining systemic iron homeostasis in mammals. This has been stimulated by the evidence that iron dyshomeostasis is an initial cause of several disorders, including genetic and sporadic neurodegenerative disorders. Critical Issues: However, very little has been done to investigate the physiological role of iron in peripheral nervous system (PNS), despite the development of suitable cellular and animal models. Future Directions: To stimulate research on iron metabolism and peripheral neuropathy, we provide a summary of the knowledge on iron homeostasis in the PNS, on its transport across the blood–nerve barrier, its involvement in myelination, and we identify unresolved questions. Furthermore, we comment on the role of iron in iron-related disorder with peripheral component, in demyelinating and metabolic peripheral neuropathies. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 21, 634–648.

Introduction

Iron is a crucial cofactor for vital functions, such as oxygen transport, DNA synthesis and repair, respiratory activity, myelin formation maintenance, and for the synthesis of neurotransmitters (10, 140). Its importance is due to its ability to easily switch from the ferrous (Fe2+) to the ferric (Fe3+) state allowing the catalysis of cellular electron-transfer reactions (58, 59). The ferric form is highly insoluble at physiological pH values and only when bound to a carrier can be transported through cellular compartments. The ferrous form, instead, is soluble at physiological pH but is rapidly oxidized to the ferric form, and thus, it must be continuously reduced and kept bound to a carrier to avoid oxygen exposure. In both oxidation states, excess iron is thought to catalyze the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (58). Fe2+ is a substrate of the Fenton reaction, whereas Fe3+ is implicated in the Haber and Weiss reaction, which appears to occur in vivo in the presence of iron (88), and it is commonly referred to as the iron-catalyzed Haber–Weiss reaction (75) (Fig. 1). Furthermore, iron may also promote the consumption of glutathione (GSH), which is the most abundant antioxidant agent in the intracellular medium (63, 105) (Equations in Fig. 1). Thus, iron excess could be extremely detrimental as active redox iron may directly contribute to cell damage or affect signaling pathways involved in cell necrosis–apoptosis.

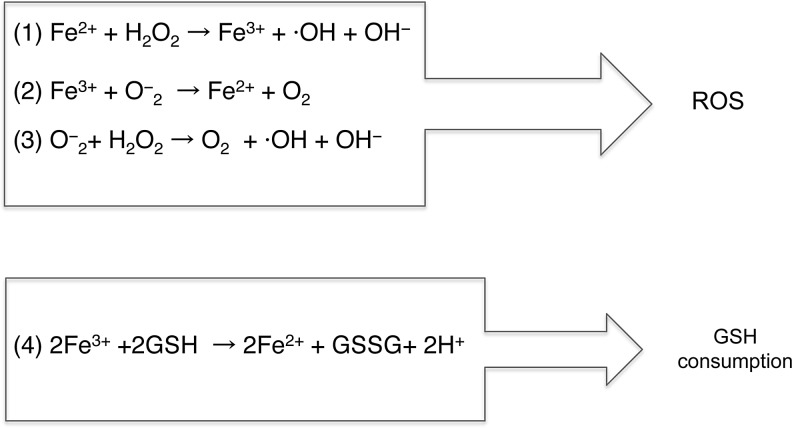

FIG. 1.

The reaction catalyzed by iron and O2. In the presence of H2O2, Fe2+ triggers the formation of hydroxyl radicals via the equations named Fenton reaction (Eq. 1). In the presence of trace amount of iron, the so-called Haber and Weiss reactions (Eqs. 2 and 3) occur. (Eq. 4) Equation of GSH consumption by iron. GSH, glutathione.

Nervous system, in particular human brain, is highly susceptible to oxidative stress injury. This is most likely due to high concentrations of lipids and unsaturated fatty acids, accompanied by a relatively high concentration of iron, which increases during aging, and a low concentration of enzymes able to inactivate ROS. Indeed, in recent years, excess iron has been described as a common hallmark in many neurodegenerative disorders, including Parkinson's and Alzheimer's diseases (2).

Also, iron deficiency is involved in the pathogenesis of restless leg syndrome (RLS) (121) (now named Willis–Ekbom disease [WED/RLS; OMIM 102300]) and in peripheral neuropathies (72), further highlighting the importance of this component. In these disorders, local alterations of iron levels or of the proteins involved in iron metabolism have often been reported. However, it is still unclear whether this is causative or a consequence of degenerating processes. Nevertheless, the desire of clarifying alterations in iron homeostasis in neurodegenerative diseases has triggered a novel interest in understanding the iron metabolism management in the nervous system, although the majority of the studies have focused on the central nervous system (CNS). Accordingly, it is well established that the brain is characterized by limited iron exchanges, since the blood–brain barrier (BBB) limits its transport, and that it expresses all the proteins involved in the systemic iron regulatory mechanisms (74, 99). This includes proteins for cellular iron uptake (metal transporters, transferrin receptors [TfRs], ferroxidases), iron storage proteins (ferritins), cellular iron exporter (ferroportin [FPN1]), and iron regulatory proteins (Iron Responsive Proteins 1 and 2) [reviewed in refs. (38, 96), and described in Fig. 2]. On the contrary, relative little is known on iron metabolism in the peripheral nervous system (PNS). This lack of interest probably reflects a consideration that iron alterations in the PNS might be less relevant. The purpose of this article was to review the current literature on the physiological role of iron in the PNS and its involvement in peripheral neuropathy. More importantly, we would like to stimulate further studies on this topic. The availability of animal models faithfully reproducing disorders in iron metabolism could constitute a valid approach to investigate the role of iron in the PNS.

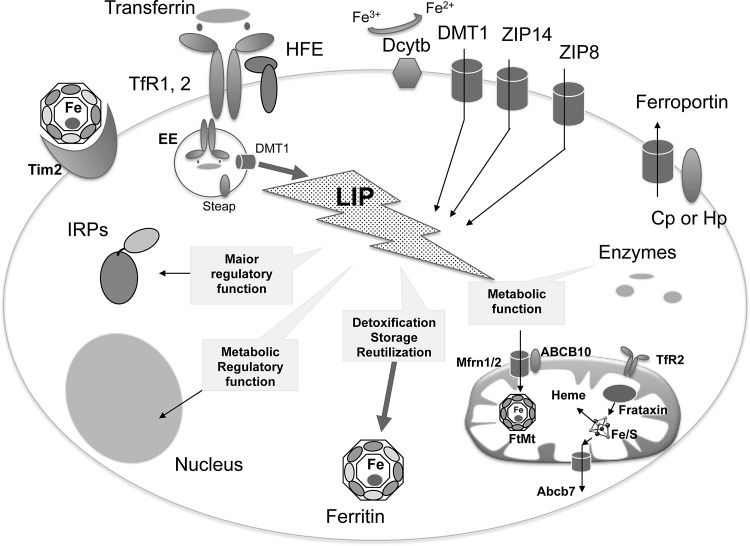

FIG. 2.

Schematic representation of cellular components involved in iron homeostasis. Nonheme iron can enter mammalian cells via two distinct mechanisms. Fe3+ is transported via receptor-mediated endocytosis of Tf/TfR1/2 (transferrin/transferrin receptor1/2) or ferritin/Tim2. HFE interacts with TfR1 to influence the rate of receptor-mediated uptake of transferrin-bound iron. Transport of Fe2+ is mediated by divalent channel located on the plasmamembrane (DMT1, ZIP14, ZIP8), on endosomes (DMT1), and lysosomes (not shown). Their activity is joined to ferric reductases (Dcytb, Steap). When in cytosol, iron forms the LIP, which is the redox-reactive form of iron. It is sensed by IRPs, the excess stored into the iron-storage ferritin molecule or addressed to mitochondria. The mitochondrial iron importers are Mfrn 1/2, assisted by ABC10, and, at least in dopaminergic neurons, the TfR2. In the organelle, iron is utilized for maintaining iron-dependent cofactor biosynthesis, like heme and iron–sulfur cluster (Fe/S). These cofactors are coupled with enzymes inside mitochondria and also exported by specialized transporters (ABCB7 for Fe/S and FLVCR1b for heme, in erythroid progenitors) into cytosol for the loading into cytosolic enzymes. Iron excess is stored by FtMt, which is expressed in cells with high metabolic activity. The only iron exporter so far identified is ferroportin. Its activity is supported by the feroxidases, named Cp or Hp. Cp, ceruloplasmin; DMT1, dimetal transporter 1; FtMt, mitochondrial ferritin; Hp, hephestin; IRPs, iron protein expression regulatory proteins; LIP, labile iron pool; Tf, transferrin; TfR, transferrin receptor; HFE, MHC-related protein, that is mutated in hereditary hemochromatosis.

PNS Structure

During embryonic development, PNS neurons and associated glial cells derive from the neuroectoderm, whereas the nerve sheath and nerve vasculature originate from the mesoderm. Neural crest cells, which are responsible for the formation of neurons and glial cells, can generate distinct but also overlapping sets of derivative. In particular, Schwann cells (SCs), the myelinating glia of the PNS, derive from neural crest cells of the entire anteroposterior axis (82). In addition, while most premigratory cells, such as sensory neurons and glia, are multipotent (48), there are also precursors generating a single unique neural crest derivative.

The main function of the PNS is to collect impulses from the periphery and transfer them to the CNS, where they are integrated to generate an adequate response. PNS neurons extend over a significant length that in humans can reach above 1 m in extension (12). Thus, a correct and fast conduction of electrical impulses is essential for rapid and maximal response. In vertebrates, this is achieved by the generation of myelin (158). Besides providing axonal insulation, several evidences indicate that myelin is essential also for neuronal protection. In the absence of myelin, axons degenerate and this is the main cause of morbidity in demyelinating and dysmyelinating disorders (102).

Myelin is composed of 70% of lipids and 30% of proteins and insulates the majority of PNS and CNS axons (93). This structure is formed by the wrapping of the plasma membrane of myelinating glial cells, oligodendrocytes (OL) in the CNS, and SC in the PNS, along the axons and is continuous except at the levels of the Nodes of Ranvier (12). The latter are the regions with high concentration of sodium and potassium channels that facilitate the saltatory conduction of electrical impulses (127). Given the importance of myelin, we will briefly discuss the mechanisms controlling its generation in the following paragraph. We will essentially describe peripheral myelin, as this is the main topic of this review. Thorough analyses on the role of myelin in the CNS and a more exhaustive description of PNS myelin components goes beyond the aim of this review and have been extensively described in several review (19, 42, 43, 51).

Blood–nerve barrier

In the PNS, individual nerve fibers are protected from the environment by a compact connective tissue matrix, consisting of three layers: the epineurium, the perineurium, and the endoneurium.

Unlike the CNS where the capillaries that form the BBB are completely impermeable to proteins and macromolecules, the blood–nerve barrier (BNB) is more permeable. The BNB, also known as blood–nerve interface, is indeed a relative impermeable structure formed by the endoneurial vascular endothelium and the perineurium. Of note, the extent of permeability varies depending on different regions of the PNS, with capillaries in the fascicles more impermeable than those present in the ganglia (76).

The main function of the BNB is to protect the endoneurium and the SC from potentially dangerous constituents of the circulating plasma (12). Besides being protective, BNB facilitates also a selective exchange of nutrients and components between the endoneurium and the outside environment. The main cellular components forming the BNB are perineurium pericytes that could participate in BNB maintenance, tissue repair, and novel vascularization after an injury event (73).

Myelination in the PNS

Most peripheral nerves in vertebrates consist of a mix of myelinated and nonmyelinated fibers. In contrast, nerves of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system contain predominantly nonmyelinated fibers (78). Myelinated and nonmyelinated fibers are deputed to different types of transmission; the first are characterized by rapid conduction of the nerve impulses that can reach up to 80 m/s in humans in large caliber axons, the latter instead by a slow conduction velocity (10 m/s) (78).

The strict interconnection between axons and SC is essential for normal PNS development. Myelinating SCs in contact with axons acquire a 1:1 relationship with the axons and express a set of totally different proteins from nonmyelinating SC that instead engulf nonmyelinated axons. These two cell types, although presenting the same embryological origin, constitute two entirely different classes of cells. Nonmyelinating SCs segregate a variable number of small caliber axons (<1 μm), from a single axon up to 20, by sending out cytoplasmic processes in between. Furthermore, they maintain the expression of a set of proteins characteristic of immature SC (70, 157).

Besides controlling the final phenotype of myelinating glial cells, axons are important for SC proliferation and survival. Once a sufficient cohort of SC is generated, axonal signals determine whether SC will differentiate into myelinating or ensheathing cells, distinguishable by their anatomic relationship to the axon and the expression of distinct proteins (126). In myelinated fibers, axons also determine the amount of myelin they form. Glial cells, in turn, promote neuronal survival and regulate the organization and maintain the integrity of axons (137).

The key molecule regulating all the aspects linked to SC differentiation and myelination in the PNS is a protein member of the Neuregulin 1 (NRG1) epidermal growth factor superfamily: NRG1 type III (13, 157). NRG1 promotes the commitment of neural crest cells, the maturation, proliferation, and survival of SC and ultimately myelination (70). Specific inactivation of either NRG1 type III (156) or its cognate ErbB receptors (118) determines a lack of SC precursors and consequent death of neurons along developing nerves, thus revealing that the survival of neurons and glia in developing nerves is strictly interconnected.

In the PNS, the amount of axonal NRG1 type III determines whether a SC will myelinate or not. Above a threshold level of expression of NRG1 type III, axons are myelinated and the amount of myelin is proportional to the levels of NRG1 type III on the axons (95, 138).

PNS plasticity

Unlike CNS axons, PNS neurons present a remarkable regenerative capacity, although PNS lesions could still present several adverse effects, including paralysis and lack of autonomic control of affected body areas (18). These effects are a particular cause of morbidity in all PNS pathologies and a big effort has been dedicated in finding effective therapies that could enhance regeneration and remyelination (102). This is particularly relevant in chronic disorders independent of whether their cause is a primary defect in the PNS, as in CMT hereditary neuropathies, or secondary to a metabolic alteration, as in diabetic patients.

Given the importance of these events, we will briefly summarize the actual knowledge in this field.

After an injury in peripheral axons, the part distal to the injury site undergoes a series of changes known as Wallerian degeneration. These events are controlled at several levels and require interactions between SC, macrophages that invade the space after BNB breakdown, and neuronal cells. Among the early events following injury, there is the disruption of the axonal plasma membrane, which allows the entry of extracellular ions into axons and subsequent depolarization. This neuronal cytoplasmic disorganization triggers the activation of SCs, which start to proliferate and eventually facilitate the recruitment of macrophages. Both SCs and macrophages are instrumental for myelin clearance. In addition, SC undergo significant changes in their morphology and eventually line up along injured nerves to form the Bands of Bunger that are essential for directing the axons toward their target [reviewed in ref. (128)]. Recent studies have shown that the transcription factor c-jun is the key molecule driving all these events (4). Several studies have also indicated that the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines facilitates the recruitment of macrophages at the lesion site (16, 33, 101).

Although the amount of regeneration is relevant in PNS injury events, two main issues limit its effectiveness. The entire regenerating process is extremely slow, thus hampering complete regeneration. Furthermore, the lack of selectivity in the axon-target recognition ultimately causes poor functional recovery (18).

Very few studies have investigated the role of iron in Wallerian degeneration; thus, it will be particularly important to deeply investigate its role in an animal model of PNS injury given the importance of this ion in controlling cellular metabolism.

Iron Transport Across BNB

The BNB, as above discussed, consists of the endoneurial microvessels within the nerve fascicle and the investing perineurium (155). Unlike the detailed analysis of iron transport through the BBB [reviewed in ref. (96)], little is known about iron passage through the BNB. From few comparative studies on the expression of enzymes, transporters, and receptors at both the BNB and BBB, as well as in the perineurium of peripheral nerves, it is clear that the BNB and BBB share common features but have also distinct identities (97). In a comparative study, Orte et al. analyzed the relative distribution of TfR1, using immunodetection of the protein on rat brain cortex and sciatic nerve by the monoclonal OX-26 (107). The data showed a higher heterogeneity of membrane proteins in nerve compared to brain. In particular, the expression of TfR1 resulted in a strongly reduced BNB (107). In the brain, cerebrovascular endothelial cells forming BBB facilitate iron uptake (68). At this level, the receptor-mediated endocytosis of transferrin (Tf) plays a primary role (74, 99), although also Tf-independent mechanisms may contribute to brain iron transport (20, 98), as suggested by normal amount of iron in brains of hypotransferrinemic mice (11). This reflects the existence of different mechanisms in iron acquisition in the PNS compared to the CNS, or, more likely, the necessity of reduced amount of iron to maintain functional PNS neuronal activity is yet to be determined. However, peripheral nerves are particularly rich in Tf (87), at least in a determined period of life. Tf was initially identified as sciatin in chicken sciatic nerve by Markelonis and Tae Hwan (90), where it operated as a trophic factor for the maturation and maintenance of skeletal muscle cells (90). Then, the same authors recognized sciatin as Tf (91), and further studies indicated that it acts as a neurotrophic factor (9). The massive presence of Tf sustains the importance of the Tf-TfR1 complex for iron acquisition also in the PNS.

Another source of iron in CNS is ferritin, via its cellular internalization by the specific receptor Tim-2 expressed by OL (142). Mammalians ferritin is a spherical shell molecule made of 24 subunits of two types (H and L) that assemble in heteropolimers containing up to 4000 iron atoms per molecule (3). Thus, ferritin may play an important role in iron delivering to the cells. Surprisingly, no data are available on the expression of Tim-2 in the PNS. Furthermore, several studies in which ferritin was utilized as electron-dense tracer in peripheral nerve fibers or as a marker of BNB integrity have shown that a ferritin-dependent active mechanism does not exist in the PNS (57). Accordingly, the perineurium is an efficient barrier for in vivo delivery of ferritin into sciatic nerve of adult mice (57). Moreover, ferritin exudation occurs only when the BNB become clearly defective as in the pathogenesis of leprosy neuropathy (15) or by alterations following nerve crush (22).

A very recent article indicated dimetal transporter 1 (DMT1), a Fe2+ transporter responsible for iron uptake from the gut and transport from endosomes, as another candidate of nontransferrin bound iron (NTBI) acquisition within the PNS (151). By immunotechniques, the authors showed the presence of DMT1 in nerve homogenate, isolated from adult rat and in cultured SC, where it localizes on the plasma membrane (151). Unfortunately, they did not show any data on the specificity of the commercially available antibody used in immunofluorescence experiments, making the observation not exhaustive. The DMT1-dependent mechanism of iron import is well described in CNS (21), and thus, it is conceivable that it may be conserved also in the PNS.

No data are available at the moment on the expression in the PNS of other metal-ion transporters, like ZIP8 and ZIP14, which are involved in iron transport and expressed in human brain tissues (153) and rat primary astrocytes (14).

Iron in SCs

Several data indicate that iron is a crucial element in the multifactorial process of OL myelination in the CNS (122, 131, 141). Unlike the significant number of studies investigating iron management in OL (141), a small amount of data are reported on iron in SCs. In OL, Tf lacks the signal peptide for the export and it is required for OL maturation and myelin formation (10, 85, 109).

In the PNS, Tf appears to accumulate in SC cytoplasm in myelinating sciatic nerves, but not in unmyelinated cervical sympathetic trunk, supporting a major role for Tf and iron in myelination (87). More recent studies, however, performed on isolated SCs at different stages of development, lead to partially different conclusions (125). According to Salis et al., Tf mRNA is expressed in SCs during late embryonic age but not postnatally, whereas the protein is detectable in late embryonic development and only in young animals (125). They also suggest that differences with previous analyses are possibly related to a different preparation of the analyzed samples: Lin et al. examined a section of sciatic nerve (87) whereas Salis et al. studied Tf expression on isolated SCs and cultured for 12 h (125). The conclusions of this latter study are that (i) the temporal correlation between the expression of Tf mRNA and protein suggests that Tf is locally synthesized and (ii) Tf seems to be required during SC maturation and myelin formation. They further confirm this result by analyzing Tf expression 3 days after mechanical injury of rat sciatic nerve and during regeneration. In these analyses, Tf mRNA is expressed in damaged nerve, but it is downregulated 7 days after injury (125) (Fig. 3).

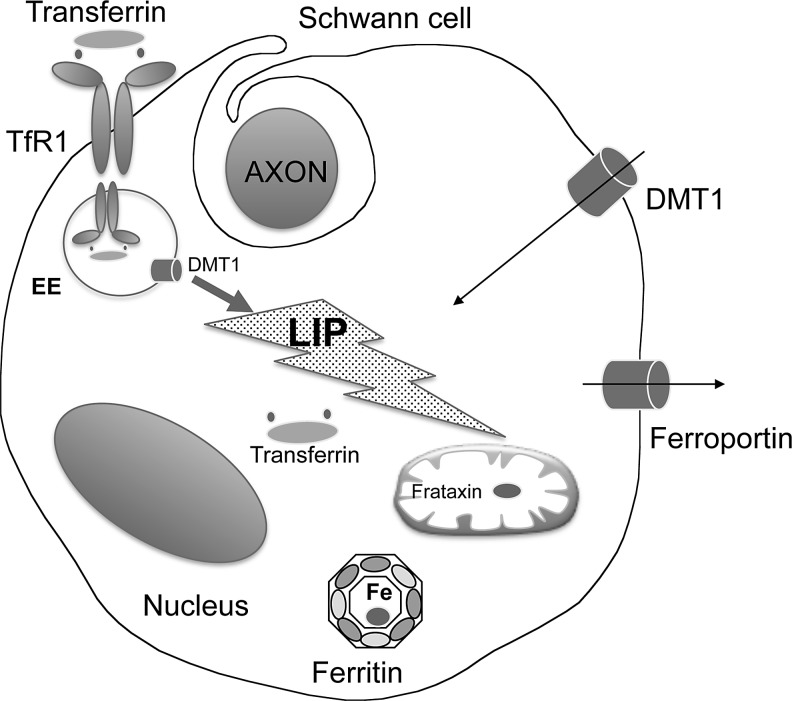

FIG. 3.

Schematic representation of iron homeostasis in SC. The scheme summarizes the data available on iron proteins expression in SC and the small amount of information regarding the Tf/TfR1 complex, DMT1, ferritin, frataxin, and ferroportin. Of note, the presence of transferrin in cytosolic compartment. Symbols and abbreviations as in Figure 2. SC, Schwann cell.

Thus, Salis et al. propose that in the PNS locally synthesized Tf acts as a prodifferentiating factor during late embryonic ages and during nerve regeneration, whereas in the adult animals, SCs harvest Tf by receptor-mediated mechanism from the circulation (125). However, we cannot exclude that Tf may act as an intracellular iron transporter in SCs, even if only during conditions of a major cellular iron requirement (development or regeneration).

Although Tf might play a role in PNS myelination and during regeneration, a deeper investigation on the role of this molecule in vivo in animal models lacking proteins specific for iron metabolism is required. Isolated SCs as well as analyses in sciatic nerve sections do not entirely recapitulate all the events occurring in an in vivo setting (Fig. 4). In particular, the analysis of PNS morphology in hypotransferrinemic mouse could be very informative, but unfortunately, there are no data available on this animal model.

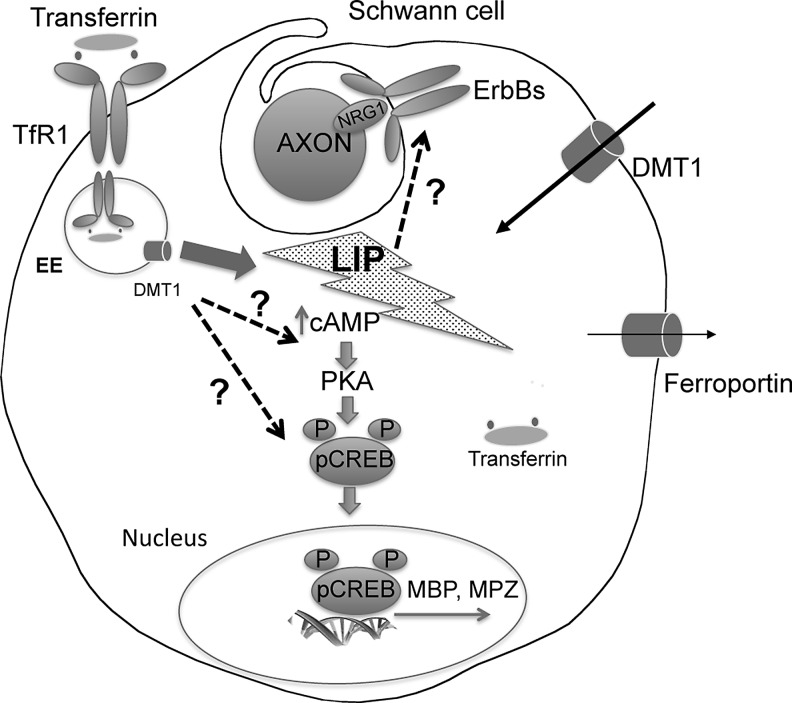

FIG. 4.

Schematic representation of the proposed myelination pathway in SC. The scheme described the myelination pathway in SC proposed by Salis and coworkers. Question marks indicate the still not conclusive results obtained on the role of human transferrin (hTf) and low Fe3+ amount on SC differentiation (123). The data presented, although suggestive, do not allow a definitive conclusion on the role of hTf in SC differentiation. To further substantiate the presented results, it would be important to assess the role of Fe3+ and hTf in myelinating cocultures and to determine whether this may impact the effectiveness of NRG1 signaling in SC differentiation and in myelination. NRG1, neuregulin 1.

The importance of iron uptake in the regulation of cellular growth and proliferation during PNS regeneration is also highlighted in earlier studies. Raivich et al. analyzed the expression and distribution of Tf receptors and of intravenously injected 59Fe3+ following injury in rat sciatic nerve (115). By immunocytochemistry using the OX-26 monoclonal antibody, Raivich et al. demonstrated that SC upregulated TfR1 and that its expression is paralleled to a massive increase in endoneural 59Fe-uptake restricted to the lesion site (115). After axotomy, a similar phenomenon occurs also in regenerating motor neurons, which showed a strong increase of TfR1 expression and iron uptake (53). SC dedifferentiation is also dependent on iron availability as demonstrated by the capacity of holo-Tf, but not of apo-Tf, to prevent a decrease in the expression of myelin basic protein (MBP) and myelin protein zero (MPZ) and the increase in immature SC markers (p75NTR and glial fibrillary acidic protein) following serum deprivation (124). More recently, the same group showed that also Fe3+ is able to stimulate the differentiation of cultured SCs (123). The mechanism seems linked to the pro-oxidant iron effect that increase cAMP levels and CREB phosphorylation, with subsequent stimulation of MBP and MPZ expression (123) (Fig. 4).

During nerve regeneration, another source of iron may be represented by heme. In myelin-phagocytosing SC of rat-injured sciatic nerves, the stress protein heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) is induced (64). HO-1 catalyzes the oxidation of heme to biliverdin with the release of Fe2+ and CO, and it is thought to be involved in protecting cells from oxidative damage (143). Interestingly, the induction of HO-1 expression is paralleled by the expression of TfR1, suggesting that iron derived by heme catabolism is recycled during nerve regeneration. SCs also express hemopexin, the heme-scavenger protein involved in heme catabolism (143). Hemopexin is present at low level in sciatic nerve (136), but it strongly accumulates after nerve injury, whereas its level decreases progressively during regeneration (27). Thus, an exceptional iron/heme trafficking appears to occur during the acute phase of nerve regeneration.

Despite the extensive literature regarding ferritin (49) and more limited on FPN1 in CNS (161), very little is known on these two proteins in the PNS. Koeppen and colleagues made a detailed description of ferritin and FPN1 in peripheral neurological component, investigating iron involvement in peripheral neuropathy in Freidreich's ataxia (FRDA) (discussed below). From his work, in physiological condition, ferritin immunostaining results prominent in SC cytosol and in satellite cells, whereas FPN1 immunostaining is positive in cytoplasm of satellite cells, neurons, and large axons of sural nerve (100). FPN1 is the only cellular iron exporter, identified so far, thus, its presence indicates iron trafficking within peripheral nerve components. Intracellular iron amount regulates the activity of the iron protein expression regulatory proteins/iron responsive element (IRE) machinery, which modulates the expression of ferritin, FPN1, TfR1, and DMT1 at translational level [reviewed in ref. (62)]. This homeostatic control is described to occur in brain (69, 132), but no data are collected in the PNS.

Iron in Peripheral Neurons

In 1997, in an elegant work, Hemar et al. demonstrated that a dendroaxonal transcytotic pathway is used by the endogenous ligand Tf and its receptor to transport iron in cultured hippocampal and sympathetic neurons. They used a combination of semiquantitative light microscopy, video microscopy, and a biochemical assay to show that the internalized 55Fe-Tf from the cell body–dendrite area is released at the axonal end. In addition, they demonstrated that excitatory neurotransmitters increase Tf receptor transcytosis, whereas inhibitory neurotransmitters reduce it (61). Thus, this system seems to provide iron to the axon in physiological condition, and it is plastic enough to respond to neurotransmitters.

PNS neurons express DMT1. Four major mRNA isoforms exist; they differ at the 5′ (designated 1A vs. 1B) or at 3′ (+IRE+IRE vs. −IRE) reflecting the presence/absence of IRE at the mRNA 3′ end. These differences are important for DMT1 regulation at transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels (52). Using specific antibodies, Roth et al. determined the expression and the distribution of DMT1 isoforms in different cell lines and cultures of sympathetic ganglion neurons isolated from perinatal rat pups (119). They showed that the +IRE form of DMT1 is distributed within vesicles in the cell body and axonal projections, with minimal nuclear staining, whereas the −IRE form of DMT1 selectively accumulate in the nucleus of neuronal cells, with limited nuclear staining observed in SCs. In addition, they recently demonstrated that the transcription of DMT1 1B isoform is under regulation of nitric oxide in several cell lines, including rat primary sympathetic neurons (112). Nuclear NF-kappaB mediates this regulation in PC19 cells, suggesting that DMT1 might respond to stress-related signaling processes. This mechanism could be relevant in peripheral neurons to create a relationship between iron uptake and stress-related event.

By reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction, in situ hybridization, and immunohistochemistry, Zechel et al. demonstrated that hepcidin mRNA and protein are expressed in dorsal root ganglia (DRG) neurons (159). Hepcidin is a small circulating peptide that modulates systemic iron balance by limiting the absorption of dietary iron and the release of iron from macrophage stores (46). Defects in hepcidin expression are responsible for massive parenchymal iron accumulation, such as in hemocromatosis (25), whereas mice overexpressing hepcidin die postnatally by a severe anemia. Unfortunately, no other data on hepcidin in the PNS appeared after the important finding reported by Zechel et al. (159) in 2006. Thus, the cellular mechanisms and functions of hepcidin in the PNS remain to be elucidated.

Iron-Related Disorders with PNS Component

As expected by the high neuronal sensibility to iron toxicity and by the involvement of iron in myelin formation and maintenance in CNS (108, 141), both iron overload and iron deficiency may induce peripheral neuropathy; however, little is known on the role of iron in the pathogenesis of peripheral neuropathies. Although there are some evidences on iron metabolism alterations, more studies are required to specifically correlate iron metabolism with the pathogenesis of PNS disorders.

Friedreich's ataxia

FRDA (OMIM #229300) is the most prevalent form of autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia in Caucasian (1:50,000) and the most studied iron-related neurological disorder with the PNS involvement system (28). FRDA is a neurodegenerative and demyelinating disorder caused by frataxin deficiency due to GAA repeated expansion in frataxin gene (FXN) [reviewed in ref. (111)]. Frataxin is a ubiquitous nuclear-encoded mitochondrial protein that participates in the biogenesis of iron–sulfur clusters (86). Iron–sulfur clusters are cofactors of several enzymes, including those involved in electron transport chain, TCA cycle, and heme synthesis [reviewed in ref. (86)]. Thus, insufficiency of these cofactors leads to impairment of oxidative phosphorylation and oxidative damage.

FRDA is characterized by a complex neuropathological phenotype with typical lesions in DRGs, dorsal spinal roots, dorsal nuclei of Clarke, spinocerebellar and corticospinal tracts, dentate nuclei, and sensory nerves. In particular, the hallmark of sensory neuropathy in FRDA is hypomyelination due to a defective interaction between axons and SC and slow axonal degeneration.

The non-neurological aspects of the phenotype include hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, the leading cause of patients' death, and diabetes mellitus (111). In humans, iron accumulation in the heart of FRDA patients is well established (81, 94) at both mitochondrial (65) and cytosolic level (117), whereas iron burden in the nervous system was detected by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in dentate nuclei (152). This result is, however, controversial as biochemical and histological data obtained by the analyses of nine dentate nuclei from FRDA patients did not confirm the differences in total iron amount (79). Surprisingly, despite the extensive studies on the role of iron in various cellular and animal disease models (92), the contribution of iron to the pathogenesis of FRDA is still controversial. Although some authors consider iron accumulation not a triggering event in early FRDA pathogenesis (8), we cannot exclude that it may be involved in causing tissue oxidative damage, which is particularly detrimental to the nervous system.

To assess the role of iron and iron proteins in FRDA peripheral neuropathies, Koeppen et al. examined ferritin, mitochondrial ferritin, and FPN1 by immunocytochemistry in DRG from 19 FRDA cases. They also utilized high-definition X-ray fluorescence (HDXRF) to visualize iron accumulation on the same specimens (80). Furthermore, they measured total iron in unfixed frozen tissue of DRG from three FRDA patients and nine normal controls. Although the difference in total iron between patients and controls was not significant, in DRG of FRDA patients, HDXRF detected regional and diffuse increase in iron fluorescence that matched ferritin expression in satellite cells. Also, FPN1 immunostaining was defective in FRDA DRG neurons, whereas satellite cells remained FPN1 positive. Based on these results, the authors concluded that satellite cells and DRG neurons in FRDA are affected by iron dysmetabolism.

This does not seem to be confirmed at distal nerve site. Morphological analyses of autoptic sural nerves of six FRDA patients suggested that ferritin normally localizes in SC cytoplasm and that the staining is not increased in patients. Furthermore, all sural nerve axons in FRDA resulted positive to FPN1, indicating that there is no sign of distal iron dysmetabolism in FRDA patients (100). Thus, iron dyshomeostasis appears concentrated more proximally in the DRGs.

Interestingly, SC knockdown of frataxin by RNA interference reduces cell death viability and proliferation (89). Microarray analyses of frataxin-deficient SCs showed strong activations of inflammatory and cell death genes and inflammatory arachidonate metabolites. The toxicity in frataxin-deficient SCs is partially rescued by anti-inflammatory and antiapoptotic drugs, whereas antioxidant and iron-chelated drugs had no beneficial effect (89). These data are in agreement with the evidence that in the PNS, SCs may, in some stressed conditions, serve as partially immunocompetent cells by producing a variety of proinflammatory cytokines that can lead to cell death (89). The relationship between iron and inflammatory processes is well defined at systemic level (26), and it begins to be clarified also in the CNS (145), where iron accumulation enhances the inflammatory cytokine effect (160). This connection is exerted by hepcidin (50). Hepcidin synthesis is upregulated in response to inflammatory stimuli and may lead to intracellular iron overload by promoting the degradation of the cellular iron exporter FPN1 (154). Unfortunately, there are no data available on the expression of hepcidin in SCs or satellite cells, and thus, the role of iron during PNS inflammation remains to be determined.

Neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation

Neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA) characterizes a class of neurodegenerative diseases featuring a prominent extrapyramidal movement disorder, intellectual deterioration, and a characteristic deposition of iron in the basal ganglia. The diagnosis of NBIA is made on the basis of the combination of representative clinical features along with MRI evidence of iron accumulation (55). NBIA includes very rare genetic infantile and adult-onset disorders, caused by alteration in iron genes (neuroferritinopathy and aceruplasminemia) or in genes apparently unrelated to iron homeostasis. Few of them show also phenotypic alteration in the PNS. Thus, understanding why only some of these disorders manifest also a PNS component could help in a better understanding of the mechanisms causative of these pathologies and might prove useful for the development of future treatments.

Neuroferritinopathy (OMIM, 606159, also labeled as hereditary ferritinopathies) is a rare autosomal dominant progressive movement disorder caused by mutations in exon 4 of the ferritin light chain gene (40). Symptoms and abnormal physical signs interest mainly the nervous system, and they are generally observed in the fourth to sixth decade of life. Wide ranges of neurological symptoms occur: choreoathetosis, dystonia, spasticity, and rigidity, whereas cognitive decline is rare or subtle in the early stages. The hallmark of this disease is the presence of abundant spherical inclusions in the brain and in other organs such as skin, kidney, liver, and muscle, which are positive to iron, ferritin, and ubiquitin staining. Data obtained by in vitro experiments suggest that the pathogenesis could be caused by a reduction in ferritin iron storage capacity and by enhanced toxicity associated with iron-induced ferritin aggregates. In contrast, data on cellular models, confirmed by the study on transgenic mouse model (6), suggest that the pathogenesis could be related to oxidative damage (35, 36). Schroder described similar pathognostic structures in nerve biopsy specimens in a case with similar symptoms, previously described as “granular nuclear inclusion body disease.” The nuclear inclusions were iron positive and immunoreactive for ferritin. Furthermore, they were essentially located within the epineurium in perivascular cells, whereas no nuclear inclusions were detected in endothelial cells or in SCs of myelinated or unmyelinated fibers (130). However, the lack of genetic analyses, confirming neuroferritinopathy mutations, makes this interesting observation not conclusive. Thus, more studies are necessary to determine the decisive involvement of the PNS. These findings suggest a ferritin-aggregation mechanism specific on cell type that could be easily investigated on already available neuroferritinopathy transgenic mice.

Within NBIA, peripheral neuropathy has been described also in patients affected by infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy (INAD; OMIM #256600). INAD is an inherited degenerative disorder characterized by nerve abnormalities in brain, spinal cord, and peripheral nerves. PLA2G6, which encodes for a Ca(2+)-independent phospholipase A(2), is the causative gene, but how mutations in this gene lead to the disease is unknown. The only immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study on the CNS and PNS of INAD cases revealed numerous spheroid bodies in the CNS and PNS that unfortunately were not been investigated for iron or iron proteins (67). It is therefore necessary to more profoundly investigate the identity of these deposits. The results of these studies might be very helpful in the comprehension of the INAD pathogenetic mechanisms, and whether there might be differences in iron protein expression in the CNS and PNS.

Willis–Ekbom disease (restless legs syndrome)

Willis–Ekbom disease (WED/RLS) is a common sensorimotor disorder characterized by a strong urge to move the legs, especially during rest (121, 144). It may be idiopathic (primary) or secondary depending on clinical features. The pathophysiology of WED/RLS is only partly clarified, but a strong association with brain iron deficiency possibly resulting in impaired dopaminergic function has been recognized (126). Another supporting data on the relevance of iron availability in WED/RLS come from a very recent article reporting a unique case of a 23-year-old female patient affected by idiopathic generalized seizures and atypical WED/RLS, carrying a homozygous loss-of-function mutation in the L-ferritin gene (37). The study of the pathogenetic mechanism, carried out on patient's fibroblasts and induced neurons, shows a causative correlation between diminished cytoplasmic iron availability, due to the absence of L-ferritin chain, and the development of epilepsy and WED/RLS (37). Of note, iron treatment reduces the severity of WED/RLS (31, 56).

Iron deficiency is frequently associated with hypomyelination in brains of animal models (108). Data from postmortem and imaging-based analyses of 11 WED/RLS patients and 11 controls indicated a wide spread impairment in CNS myelin associated to ferritin and Tf decrease in the myelin fraction of affected patients (34). Direct evidences on myelin composition in the PNS of WED/RLS patients are not available; however, associations between peripheral neuropathy and WED/RLS have been described. In a recent study, Hattan et al. screened a large cohort of 245 patients with peripheral neuropathy and 245 age- and sex-matched controls for WED/RLS and concluded that WED/RLS is more prevalent among patients with hereditary but not acquired neuropathies (60). Thus, whether peripheral neuropathy is among the potential causes of WED/RLS remains to be determined, and further studies on the prevalence of peripheral neuropathies in WED/RLS-affected patients are also required.

Iron-deficiency anemia

Despite strong evidences that iron deficiency in utero or in early postnatal life can hamper cerebral development, few studies have related the effect of iron-deficiency anemia (IDA) to peripheral neuropathies. Kabakus et al. assessed nerve conduction velocity in 18 children with IDA and 12 healthy children before and after 3 months of iron therapy. In IDA children, nerves conduction velocity and distal-amplitude values were lower compared with controls. More importantly, they also showed that peripheral neuropathy symptoms in IDA patients could be improved with iron therapy (72). However, these results were not confirmed in another study in which the authors put in IDA relationship with WED/RLS. Thirty-four patients affected by IDA were screened for WED/RLS symptoms, and both the groups were subjected to electrophysiological examination, including motor and sensory nerve conduction, F-responses, H-reflex, blink-reflex, and mixed nerve silent periods. The authors concluded that IDA does not cause electrophysiological changes in peripheral nerves and that no significant differences were evident between the two groups (1). More studies are therefore required to conclude that there is a PNS component in IDA patients.

Other evidences suggesting that anemia could be involved in peripheral neuropathy also come from patients affected by beta-thalassemia, who usually show a high prevalence of sensory neuropathy (133). Also subjects undertaking bariatric surgery develop peripheral neuropathy more frequently than those subjected to other abdominal surgeries, most likely as a consequence of malnutrition (139).

Iron in Demyelinating Neuropathies

Charcot–Marie–Tooth neuropathies

Charcot–Marie–Tooth (CMT) neuropathies represent a class of highly heterogeneous family of disorder due to mutations in more than 40 genes. These genes encode for proteins with different cellular localization, transcription factors, molecules involved in axonal transport, mitochondrial metabolism, cytoskeleton formation, and intracellular signaling (129). The more frequent form of the disorder is due to the duplication of the peripheral myelin protein 22 (PMP22) gene that accounts for ∼50% of all cases. All CMT patients present a progressive neuropathy that affects myelinated motor and sensory axons in a length-dependent manner (113). Independent of their genetic origin, CMT neuropathies determine a progressive axonal degenerative process. Despite the incidence of the disease (50/100,000) and the significant impairment in the quality of life of affected patients, there is no adequate treatment for these neuropathies (114).

CMT neuropathies are classified based on the nerve conduction velocity and nerve pathology and are subdivided into several classes:

• CMT1: Demyelinating neuropathy with significant myelin alterations and severely impaired nerve conduction velocity (<38 m/s).

• CMT2: Axonal neuropathy characterized by axonal degeneration and mild reduction in nerve conduction velocity (above 38 m/s).

• CMTX: X-linked form of the disease with intermediate nerve conduction velocity (30–45 m/s).

• CMT4: Very severe autosomal recessive form characterized by earlier onset and severe course. Nerve conduction velocity is <38 m/s.

In addition to the above-described main classes, CMT neuropathies are characterized by intermediate forms due to the heterogeneity of the genes involved and their complex interactions.

Interestingly, recent microarray analyses of brain of mice subjected to high content of iron in the diet have described alterations in the expression of genes encoding ganglioside-induced differentiation-associated protein 1 (Gapd1) and lipopolysaccharide-induced TNF factor (Litaf), also known as SIMPLE (71). Both genes are associated with CMT disease (7, 39, 103, 134). Although mutations in the Litaf/SIMPLE gene cause a classical CMT1C disorder, mutations in Gdap1 cause a severe form of neuropathy (CMT4A) with very early onset and severe course.

Recent studies (84) have shown that Litaf/SIMPLE is necessary for the recruitment of some components of the endosomal sorting complex required for transport. In particular, this study proposes that Hsr, TSG101, and STAM1 regulate the endosomal internalization of ErbB receptors. Of note, TSG101 has been also implicated in controlling the internalization of the Tfr2 (30). Whether alterations in iron metabolism and TfR2 are present in CMT1C patients have not been yet investigated.

More interestingly, in the analyses of Gdap1 function, recent studies suggested that this gene is implicated in mitochondrial activity, thus proposing that oxidative stress might be implicated in the pathogenesis of CMT4A. Indeed, overexpression of wild type but not mutated forms of Gdap1 protect against oxidative stress. Furthermore, Gdap1 participates in regulating the metabolism of GSH, which is downregulated in fibroblasts from patients with CMT4A. Of note, GSH depletion hampers the neutralization of ROS species. Thus, Gdap1 might increase the levels of GSH and decrease the production of ROS, by stabilizing the mitochondrial membrane potential and respiratory chain (104).

Finally, up to 20% of dominant axonal CMT neuropathies are due to mutations in the mitofusin 2 (MNF2) gene. This is a severe form of CMT characterized also by CNS white matter abnormalities (113). MFN2, together with mitofusin 1, is necessary for mitochondrial fusion. Furthermore, MNF2 is important for an in vitro intra-axonal mitochondria transport in sensory neurons (150). Thus, a correct mitochondrial activity in some forms of CMT disorders is most likely essential to maintain the integrity of the axon, suggesting that also a correct iron metabolism might be relevant. Accordingly, severe forms of CMT neuropathies have recently been described in patients carrying mutations in both Gdap1 and MNF2 (29, 149).

In conclusion, these studies indicate that oxidative stress might significantly contribute to the pathogenesis of some rare and severe forms of CMT. In particular, the occurrence of peripheral neuropathy in several mitochondrial disorders indicates that there might be a link between iron metabolism, oxidative stress, and ROS production. This is not surprising, as the extensive length of PNS axons requires continuous support of energy also at distance. Furthermore, the detrimental effects of ROS on axons are suggestive that mitochondrial metabolism is strictly related to the generation of efficient peripheral nerves. However, due to the limited analyses of the role of iron in the pathogenesis of these disorders, it is not possible to conclude whether altered iron metabolism is among the cause of morbidities of peripheral neuropathies.

Iron in Metabolic Neuropathies

Diabetes

Diabetic polyneuropathy is a severe complication of diabetes and is characterized by progressive distal symmetric polyneuropathy, with sensory symptoms more relevant than motor ones. Symptoms, including numbness, pain, tingling, and weaknesses, originate from the distal part of the lower limbs (feet) and higher limbs (hands) and then spread to the rest of the limb in a length-dependent manner, following a distal to proximal pattern (120). Diabetic neuropathy is more frequent in patients with type II diabetes than in patients with type I diabetes. Type I diabetes is an autoimmune disorder characterized by the destruction of islet β-pancreatic cells and subsequent loss of insulin production. Type II diabetes, which affects the majority of the population, is instead a metabolic disorder with high pancreatic insulin production, eventually leading to insulin resistance, mainly in liver and muscle (24). Diabetic patients manifest a gradual but progressive loss of small myelinated and unmyelinated fibers. Patients with severe distal symmetric neuropathy are at risk of amputation with a significant impairment in the quality of their life. Another complication arising in up to 20% of diabetic patients is the development of neuropathic pain, for which there is no effective treatment. Neuropathic pain, a characteristic trait of several neuropathies, is characterized by burning and electric sensations frequently accompanied by numbness (23).

Several studies have shown that glucose control and uptake in type I patients preserves the eventual development of diabetic polyneuropathy. In the case of type II diabetic patients, however, factors other than glucose uptake contribute to the development of the neuropathy. In particular, it has been recently reported that other factors, such as obesity hypertension, dyslipidemia, inflammation, and probably neuronal insulin resistance, also contribute to the development of diabetic neuropathy (66, 77, 146). Interestingly, free fatty acids can directly affect SC metabolism (110).

Despite these recent studies, hyperglycemia is still the main factor contributing to the development of diabetic neuropathy. Prolonged excess in glucose uptake can cause cellular damage in multiple ways. In particular, the excess of glycolisis can overload the mitochondria electron transporter chain leading to an increase ROS production (148). Furthermore, increased glucose can augment cellular osmolarity and reduce NADPH levels, thus leading to oxidative stress (106). In addition, hyperglycemia can favor the production of advanced glycation end products (AGEs), which can bind to a dedicated receptor (RAGE), initiate inflammation, and generate oxidative stress (135, 147). Thus, several factors contribute to the development of this neuropathy, including mitochondrial dysfunction, DNA damage, and endoplasmic reticulum stress (23), which could be further enhanced by iron dysregulation.

Several studies have already described a link between iron metabolism and the development of diabetes. Interestingly, in vitro, insulin can redistribute TfR1 to the cell surface, suggesting that it may actively contribute to modulate cellular iron uptake. This result was further confirmed in vivo by showing that injection of insulin can increase circulating levels of soluble TfR1 (32). Experimental studies in animals have also shown that iron deficiency correlates with increased insulin sensitivity in rats (17, 44). Similarly, parental administration of iron can induce diabetes (41), indicating a possible causative role of increased iron stores in type II diabetic patients (5).

Epidemiological analyses have found that patients with type II diabetes present increased levels of circulating ferritin compared to nondiabetic individuals (47). In addition, levels of circulating NTBI are also augmented in type II diabetic patients (83). These studies are, however, not conclusive as it is possible that the primary cause for higher levels of ferritin circulation is due to obesity and/or inflammation. Furthermore, as above discussed, diabetic conditions lead to an increase in oxidative stress and mitochondrial alterations, all aspects strictly linked to iron metabolism (116).

Finally, it has been proposed that increased levels of iron storage in liver might hamper insulin extraction, causing an ultimate suppression of hepatic glucose production (45). Iron could also impair insulin action and interfere with glucose uptake in adipocytes (54). As for many of the diseases with altered iron metabolism, even in the case of diabetes, a direct link between these components requires more investigation.

Conclusions and Future Perspective

Despite the fast-growing amount of information of iron involvement in neuronal disorders, it is clear that the comprehension of the physiological role of iron in the PNS is far to be adequate. The main request is to define the expression pattern of iron proteins and their interrelationships in different PNS compartment. It is of note that, although available, the PNS of animal models lacking the proteins relevant for iron metabolism has not been investigated. This characterization accompanied by a thorough analysis of their expression profile in SC and in injured nerves could be informative on how iron participates in peripheral nerves development and regeneration. Efforts should be made to gain a mechanistic understanding on iron transport across the BNB, on the role of SC in regulating axon iron uptake, and on how iron participates in myelin synthesis. Since inflammation is a well-documented event in neuronal death, the study of the hepcidin/FPN1 axis and its link with the inflammatory process could be very instructive to acquire novel insights on the progression of axonal degeneration. Furthermore, to verify the specificity of regional iron overload in brain, it should be interesting to collect data on iron accumulation in the PNS in patients affected by NBIA. All these are crucial information on which to build a deeper knowledge on iron involvement in the pathophysiological mechanisms of peripheral neuropathies. Finally, the results of these studies might be also relevant for a better understanding of the role of iron in CNS-associated iron pathologies.

Abbreviations Used

- AGE

advanced glycation end product

- BBB

blood–brain barrier

- BNB

blood–nerve barrier

- CMT

Charcot–Marie–Tooth

- CNS

central nervous system

- Cp

ceruloplasmin

- DMT1

dimetal transporter 1

- DRG

dorsal root ganglia

- FPN1

ferroportin

- FRDA

Freidreich's ataxia

- FtMt

mitochondrial ferritin

- Gapd1

ganglioside-induced differentiation-associated protein 1

- GSH

glutathione

- HDXRF

high-definition X-ray fluorescence

- HO-1

heme oxygenase 1

- Hp

hephestin

- IDA

iron-deficiency anemia

- INAD

infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy

- IRE

iron responsive element

- IRPs

iron protein expression regulatory proteins

- LIP

labile iron pool

- Litaf

lipopolysaccharide-induced TNF factor

- MBP

myelin basic protein

- Mfrn

mitoferrin

- MNF2

mitofusin 2

- MPZ

myelin protein zero

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- NBIA

neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation

- NRG1

neuregulin 1

- NTBI

nontransferrin bound iron

- OL

oligodendrocytes

- PMP22

peripheral myelin protein 22

- PNS

peripheral nervous system

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SCs

Schwann cells

- Tf

transferrin

- TfR

transferrin receptor

- WED/RLS

Willis–Ekbom disease/restless legs syndrome

Acknowledgments

The financial support of Telethon-Italia (Grants no. GGP10099 and GGP11088) is gratefully acknowledged to S.L. Work in the laboratory of C.T. is supported by the Italian Minister of Health (GR08-35); FISM, Italy; and Telethon, Italy.

References

- 1.Akyol A, Kiylioglu N, Kadikoylu G, Bolaman AZ, and Ozgel N. Iron deficiency anemia and restless legs syndrome: is there an electrophysiological abnormality? Clin Neurol Neurosurg 106: 23–27, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altamura S. and Muckenthaler MU. Iron toxicity in diseases of aging: Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease and atherosclerosis. J Alzheimer's Dis 16: 879–895, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arosio P. and Levi S. Cytosolic and mitochondrial ferritins in the regulation of cellular iron homeostasis and oxidative damage. Biochim Biophys Acta 1800: 783–792, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arthur-Farraj PJ, Latouche M, Wilton DK, Quintes S, Chabrol E, Banerjee A, Woodhoo A, Jenkins B, Rahman M, Turmaine M, Wicher GK, Mitter R, Greensmith L, Behrens A, Raivich G, Mirsky R, and Jessen KR. c-Jun reprograms Schwann cells of injured nerves to generate a repair cell essential for regeneration. Neuron 75: 633–647, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Awai M, Narasaki M, Yamanoi Y, and Seno S. Induction of diabetes in animals by parenteral administration of ferric nitrilotriacetate. A model of experimental hemochromatosis. Am J Pathol 95: 663–673, 1979 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barbeito AG, Garringer HJ, Baraibar MA, Gao X, Arredondo M, Nunez MT, Smith MA, Ghetti B, and Vidal R. Abnormal iron metabolism and oxidative stress in mice expressing a mutant form of the ferritin light polypeptide gene. J Neurochem 109: 1067–1078, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baxter RV, Ben Othmane K, Rochelle JM, Stajich JE, Hulette C, Dew-Knight S, Hentati F, Ben Hamida M, Bel S, Stenger JE, Gilbert JR, Pericak-Vance MA, and Vance JM. Ganglioside-induced differentiation-associated protein-1 is mutant in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 4A/8q21. Nat Genet 30: 21–22, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bayot A, Santos R, Camadro JM, and Rustin P. Friedreich's ataxia: the vicious circle hypothesis revisited. BMC Med 9: 112, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beach RL, Popiela H, and Festoff BW. The identification of neurotrophic factor as a transferrin. FEBS Lett 156: 151–156, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beard JL, Connor JR, and Jones BC. Iron in the brain. Nutr Rev 51: 157–170, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beard JL, Wiesinger JA, Li N, and Connor JR. Brain iron uptake in hypotransferrinemic mice: influence of systemic iron status. J Neurosci Res 79: 254–261, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berthold CH, Fraher K, King RHM, and Rydmark MJP. Microscopic anatomy of the peripheral nervous system. In: Peripheral Neuropathy, edited by Dyck PJ. and Thomas PK. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 2005. pp. 35–80 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Birchmeier C. and Nave KA. Neuregulin-1, a key axonal signal that drives Schwann cell growth and differentiation. Glia 56: 1491–1497, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bishop GM, Scheiber IF, Dringen R, and Robinson SR. Synergistic accumulation of iron and zinc by cultured astrocytes. J Neural Transm 117: 809–817, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boddingius J. Ultrastructural and histophysiological studies on the blood-nerve barrier and perineurial barrier in leprosy neuropathy. Acta Neuropathol 64: 282–296, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boivin A, Pineau I, Barrette B, Filali M, Vallieres N, Rivest S, and Lacroix S. Toll-like receptor signaling is critical for Wallerian degeneration and functional recovery after peripheral nerve injury. J Neurosci 27: 12565–12576, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borel MJ, Beard JL, and Farrell PA. Hepatic glucose production and insulin sensitivity and responsiveness in iron-deficient anemic rats. Am J Physiol 264: E380–E390, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bosse F. Extrinsic cellular and molecular mediators of peripheral axonal regeneration. Cell Tissue Res 349: 5–14, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bunge RP. Glial cells and the central myelin sheath. Physiol Rev 48: 197–251, 1968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burdo JR. and Connor JR. Brain iron uptake and homeostatic mechanisms: an overview. Biometals 16: 63–75, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burdo JR, Menzies SL, Simpson IA, Garrick LM, Garrick MD, Dolan KG, Haile DJ, Beard JL, and Connor JR. Distribution of divalent metal transporter 1 and metal transport protein 1 in the normal and Belgrade rat. J Neurosci Res 66: 1198–1207, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bush MS, Reid AR, and Allt G. Blood-nerve barrier: ultrastructural and endothelial surface charge alterations following nerve crush. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 19: 31–40, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Callaghan BC, Cheng HT, Stables CL, Smith AL, and Feldman EL. Diabetic neuropathy: clinical manifestations and current treatments. Lancet Neurol 11: 521–534, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Callaghan BC, Hur J, and Feldman EL. Diabetic neuropathy: one disease or two? Curr Opin Neurol 25: 536–541, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Camaschella C. and Poggiali E. Inherited disorders of iron metabolism. Curr Opin Pediat 23: 14–20, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Camaschella C. and Silvestri L. Molecular mechanisms regulating hepcidin revealed by hepcidin disorders. Sci World J 11: 1357–1366, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Camborieux L, Bertrand N, and Swerts JP. Changes in expression and localization of hemopexin and its transcripts in injured nervous system: a comparison of central and peripheral tissues. Neuroscience 82: 1039–1052, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campuzano V, Montermini L, Molto MD, Pianese L, Cossee M, Cavalcanti F, Monros E, Rodius F, Duclos F, Monticelli A, Zara F, Canizares J, Koutnikova H, Bidichandani SI, Gellera C, Brice A, Trouillas P, De Michele G, Filla A, De Frutos R, Palau F, Patel PI, Di Donato S, Mandel JL, Cocozza S, Koenig M, and Pandolfo M. Friedreich's ataxia: autosomal recessive disease caused by an intronic GAA triplet repeat expansion. Science 271: 1423–1427, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cassereau J, Casasnovas C, Gueguen N, Malinge MC, Guillet V, Reynier P, Bonneau D, Amati-Bonneau P, Banchs I, Volpini V, Procaccio V, and Chevrollier A. Simultaneous MFN2 and GDAP1 mutations cause major mitochondrial defects in a patient with CMT. Neurology 76: 1524–1526, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen J, Wang J, Meyers KR, and Enns CA. Transferrin-directed internalization and cycling of transferrin receptor 2. Traffic 10: 1488–1501, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cho YW, Allen RP, and Earley CJ. Lower molecular weight intravenous iron dextran for restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med 14: 274–277, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clairmont KB. and Czech MP. Insulin injection increases the levels of serum receptors for transferrin and insulin-like growth factor-II/mannose-6-phosphate in intact rats. Endocrinology 127: 1568–1573, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coleman MP. and Freeman MR. Wallerian degeneration, wld(s), and nmnat. Annu Rev Neurosci 33: 245–267, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Connor JR, Ponnuru P, Wang XS, Patton SM, Allen RP, and Earley CJ. Profile of altered brain iron acquisition in restless legs syndrome. Brain 134: 959–968, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cozzi A, Rovelli E, Frizzale G, Campanella A, Amendola M, Arosio P, and Levi S. Oxidative stress and cell death in cells expressing L-ferritin variants causing neuroferritinopathy. Neurobiol Dis 37: 77–85, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cozzi A, Santambrogio P, Corsi B, Campanella A, Arosio P, and Levi S. Characterization of the l-ferritin variant 460InsA responsible of a hereditary ferritinopathy disorder. Neurobiol Dis 23: 644–652, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cozzi A, Santambrogio P, Privitera D, Broccoli V, Rotundo LI, Garavaglia B, Benz R, Altamura S, Goede JS, Muckenthaler MU, and Levi S. Human L-ferritin deficiency is characterized by idiopathic generalized seizures and atypical restless leg syndrome. J Exp Med 210: 1779–1791, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crichton RR, Dexter DT, and Ward RJ. Brain iron metabolism and its perturbation in neurological diseases. J Neural Transm 118: 301–314, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cuesta A, Pedrola L, Sevilla T, Garcia-Planells J, Chumillas MJ, Mayordomo F, LeGuern E, Marin I, Vilchez JJ, and Palau F. The gene encoding ganglioside-induced differentiation-associated protein 1 is mutated in axonal Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 4A disease. Nat Genet 30: 22–25, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Curtis AR, Fey C, Morris CM, Bindoff LA, Ince PG, Chinnery PF, Coulthard A, Jackson MJ, Jackson AP, McHale DP, Hay D, Barker WA, Markham AF, Bates D, Curtis A, and Burn J. Mutation in the gene encoding ferritin light polypeptide causes dominant adult-onset basal ganglia disease. Nat Genet 28: 350–354, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davis RJ, Corvera S, and Czech MP. Insulin stimulates cellular iron uptake and causes the redistribution of intracellular transferrin receptors to the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem 261: 8708–8711, 1986 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Emery B. Regulation of oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelination. Science 330: 779–782, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fancy SP, Chan JR, Baranzini SE, Franklin RJ, and Rowitch DH. Myelin regeneration: a recapitulation of development? Annu Rev Neurosci 34: 21–43, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Farrell PA, Beard JL, and Druckenmiller M. Increased insulin sensitivity in iron-deficient rats. J Nutr 118: 1104–1109, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferrannini E. Insulin resistance, iron, and the liver. Lancet 355: 2181–2182, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Finberg KE. Regulation of systemic iron homeostasis. Curr Opin Hematol 20: 208–241, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ford ES. and Cogswell ME. Diabetes and serum ferritin concentration among U.S. adults. Diabetes Care 22: 1978–1983, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Frank E. and Sanes JR. Lineage of neurons and glia in chick dorsal root ganglia: analysis in vivo with a recombinant retrovirus. Development 111: 895–908, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Friedman A, Arosio P, Finazzi D, Koziorowski D, and Galazka-Friedman J. Ferritin as an important player in neurodegeneration. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 17: 423–430, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ganz T. and Nemeth E. Hepcidin and iron homeostasis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1823: 1434–1443, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Garbay B, Heape AM, Sargueil F, and Cassagne C. Myelin synthesis in the peripheral nervous system. Prog Neurobiol 61: 267–304, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Garrick MD, Zhao L, Roth JA, Jiang H, Feng J, Foot NJ, Dalton H, Kumar S, and Garrick LM. Isoform specific regulation of divalent metal (ion) transporter (DMT1) by proteasomal degradation. Biometals 25: 787–793, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Graeber MB, Raivich G, and Kreutzberg GW. Increase of transferrin receptors and iron uptake in regenerating motor neurons. J Neurosci Res 23: 342–345, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Green A, Basile R, and Rumberger JM. Transferrin and iron induce insulin resistance of glucose transport in adipocytes. Metabolism 55: 1042–1045, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gregory A. and Hayflick SJ. Genetics of neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 11: 254–261, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Grote L, Leissner L, Hedner J, and Ulfberg J. A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled, multi-center study of intravenous iron sucrose and placebo in the treatment of restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord 24: 1445–1452, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hall SM. and Williams PL. The distribution of electron-dense tracers in peripheral nerve fibres. J Cell Sci 8: 541–555, 1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Halliwell B. Free radicals and antioxidants: updating a personal view. Nutr Rev 70: 257–265, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Halliwell B. and Gutteridge JM. Role of iron in oxygen radical reactions. Methods Enzymol 105: 47–56, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hattan E, Chalk C, and Postuma RB. Is there a higher risk of restless legs syndrome in peripheral neuropathy? Neurology 72: 955–960, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hemar A, Olivo JC, Williamson E, Saffrich R, and Dotti CG. Dendroaxonal transcytosis of transferrin in cultured hippocampal and sympathetic neurons. J Neurosci 17: 9026–9034, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hentze MW, Muckenthaler MU, Galy B, and Camaschella C. Two to tango: regulation of Mammalian iron metabolism. Cell 142: 24–38, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hider RC. and Kong XL. Glutathione: a key component of the cytoplasmic labile iron pool. Biometals 24: 1179–1187, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hirata K, He JW, Kuraoka A, Omata Y, Hirata M, Islam AT, Noguchi M, and Kawabuchi M. Heme oxygenase1 (HSP-32) is induced in myelin-phagocytosing Schwann cells of injured sciatic nerves in the rat. Eur J Neurosci 12: 4147–4152, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Huang ML, Becker EM, Whitnall M, Suryo Rahmanto Y, Ponka P, and Richardson DR. Elucidation of the mechanism of mitochondrial iron loading in Friedreich's ataxia by analysis of a mouse mutant. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 16381–16386, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hur J, Sullivan KA, Pande M, Hong Y, Sima AA, Jagadish HV, Kretzler M, and Feldman EL. The identification of gene expression profiles associated with progression of human diabetic neuropathy. Brain 134: 3222–3235, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Itoh K, Negishi H, Obayashi C, Hayashi Y, Hanioka K, Imai Y, and Itoh H. Infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy—immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies on the central and peripheral nervous systems in infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy. Kobe J Med Sci 39: 133–146, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jefferies WA, Brandon MR, Hunt SV, Williams AF, Gatter KC, and Mason DY. Transferrin receptor on endothelium of brain capillaries. Nature 312: 162–163, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jeong SY, Crooks DR, Wilson-Ollivierre H, Ghosh MC, Sougrat R, Lee J, Cooperman S, Mitchell JB, Beaumont C, and Rouault TA. Iron insufficiency compromises motor neurons and their mitochondrial function in Irp2-null mice. PloS One 6: e25404, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jessen KR. and Mirsky R. The origin and development of glial cells in peripheral nerves. Nat Rev Neurosci 6: 671–682, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Johnstone D. and Milward EA. Genome-wide microarray analysis of brain gene expression in mice on a short-term high iron diet. Neurochem Int 56: 856–863, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kabakus N, Ayar A, Yoldas TK, Ulvi H, Dogan Y, Yilmaz B, and Kilic N. Reversal of iron deficiency anemia-induced peripheral neuropathy by iron treatment in children with iron deficiency anemia. J Trop Pediatr 48: 204–209, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kanda T. Biology of the blood-nerve barrier and its alteration in immune mediated neuropathies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 84: 208–212, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ke Y. and Qian ZM. Brain iron metabolism: neurobiology and neurochemistry. Prog Neurobiol 83: 149–173, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kehrer JP. The Haber-Weiss reaction and mechanisms of toxicity. Toxicology 149: 43–50, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kiernan JA. Vascular permeability in the peripheral autonomic and somatic nervous systems: controversial aspects and comparisons with the blood-brain barrier. Microsc Res Tech 35: 122–136, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kim B, McLean LL, Philip SS, and Feldman EL. Hyperinsulinemia induces insulin resistance in dorsal root ganglion neurons. Endocrinology 152: 3638–3647, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kimura J. Nerve conduction and needle electromyography. In: Peripheral Neuropathy, edited by Dyck PJ. and Thomas PK. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 2005, pp. 899–969 [Google Scholar]

- 79.Koeppen AH, Michael SC, Knutson MD, Haile DJ, Qian J, Levi S, Santambrogio P, Garrick MD, and Lamarche JB. The dentate nucleus in Friedreich's ataxia: the role of iron-responsive proteins. Acta Neuropathol 114: 163–173, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Koeppen AH, Morral JA, Davis AN, Qian J, Petrocine SV, Knutson MD, Gibson WM, Cusack MJ, and Li D. The dorsal root ganglion in Friedreich's ataxia. Acta Neuropathol 118: 763–776, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lamarche JB, Cote M, and Lemieux B. The cardiomyopathy of Friedreich's ataxia morphological observations in 3 cases. Can J Neurol Sci 7: 389–396, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Le Douarin NM. and Ziller C. Plasticity in neural crest cell differentiation. Curr Opin Cell Biol 5: 1036–1043, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lee DH, Liu DY, Jacobs DR, Jr, Shin HR, Song K, Lee IK, Kim B, and Hider RC. Common presence of non-transferrin-bound iron among patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 29: 1090–1095, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lee SM, Chin LS, and Li L. Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease-linked protein SIMPLE functions with the ESCRT machinery in endosomal trafficking. J Cell Biol 199: 799–816, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Leitner DF. and Connor JR. Functional roles of transferrin in the brain. Biochim Biophys Acta 1820: 393–402, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lill R, Hoffmann B, Molik S, Pierik AJ, Rietzschel N, Stehling O, Uzarska MA, Webert H, Wilbrecht C, and Muhlenhoff U. The role of mitochondria in cellular iron-sulfur protein biogenesis and iron metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta 1823: 1491–1508, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lin HH, Snyder BS, and Connor JR. Transferrin expression in myelinated and non-myelinated peripheral nerves. Brain Res 526: 217–220, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Liu D, Liu J, Sun D, and Wen J. The time course of hydroxyl radical formation following spinal cord injury: the possible role of the iron-catalyzed Haber-Weiss reaction. J Neurotrauma 21: 805–816, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lu C, Schoenfeld R, Shan Y, Tsai HJ, Hammock B, and Cortopassi G. Frataxin deficiency induces Schwann cell inflammation and death. Biochim Biophys Acta 1792: 1052–1061, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Markelonis G. and Tae Hwan OH. A sciatic nerve protein has a trophic effect on development and maintenance of skeletal muscle cells in culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 76: 2470–2474, 1979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Markelonis GJ, Bradshaw RA, Oh TH, Johnson JL, and Bates OJ. Sciatin is a transferrin-like polypeptide. J Neurochem 39: 315–320, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Martelli A, Friedman LS, Reutenauer L, Messaddeq N, Perlman SL, Lynch DR, Fedosov K, Schulz JB, Pandolfo M, and Puccio H. Clinical data and characterization of the liver conditional mouse model exclude neoplasia as a non-neurological manifestation associated with Friedreich's ataxia. Dis Model Mech 5: 860–869, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Martenson RE. Myelin: Biology and Chemistry. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 94.Michael S, Petrocine SV, Qian J, Lamarche JB, Knutson MD, Garrick MD, and Koeppen AH. Iron and iron-responsive proteins in the cardiomyopathy of Friedreich's ataxia. Cerebellum 5: 257–267, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Michailov GV, Sereda MW, Brinkmann BG, Fischer TM, Haug B, Birchmeier C, Role L, Lai C, Schwab MH, and Nave KA. Axonal neuregulin-1 regulates myelin sheath thickness. Science 304: 700–703, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mills E, Dong XP, Wang F, and Xu H. Mechanisms of brain iron transport: insight into neurodegeneration and CNS disorders. Future Med Chem 2: 51–64, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mizisin AP. and Weerasuriya A. Homeostatic regulation of the endoneurial microenvironment during development, aging and in response to trauma, disease and toxic insult. Acta Neuropathol 121: 291–312, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Moos T. and Morgan EH. Evidence for low molecular weight, non-transferrin-bound iron in rat brain and cerebrospinal fluid. J Neurosci Res 54: 486–494, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Moos T, Rosengren Nielsen T, Skjorringe T, and Morgan EH. Iron trafficking inside the brain. J Neurochem 103: 1730–1740, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Morral JA, Davis AN, Qian J, Gelman BB, and Koeppen AH. Pathology and pathogenesis of sensory neuropathy in Friedreich's ataxia. Acta Neuropathol 120: 97–108, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nadeau S, Filali M, Zhang J, Kerr BJ, Rivest S, Soulet D, Iwakura Y, de Rivero Vaccari JP, Keane RW, and Lacroix S. Functional recovery after peripheral nerve injury is dependent on the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1beta and TNF: implications for neuropathic pain. J Neurosci 31: 12533–12542, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nave KA. and Trapp BD. Axon-glial signaling and the glial support of axon function. Annu Rev Neurosci 31: 535–561, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nelis E, Erdem S, Van Den Bergh PY, Belpaire-Dethiou MC, Ceuterick C, Van Gerwen V, Cuesta A, Pedrola L, Palau F, Gabreels-Festen AA, Verellen C, Tan E, Demirci M, Van Broeckhoven C, De Jonghe P, Topaloglu H, and Timmerman V. Mutations in GDAP1: autosomal recessive CMT with demyelination and axonopathy. Neurology 59: 1865–1872, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Noack R, Frede S, Albrecht P, Henke N, Pfeiffer A, Knoll K, Dehmel T, Meyer Zu Horste G, Stettner M, Kieseier BC, Summer H, Golz S, Kochanski A, Wiedau-Pazos M, Arnold S, Lewerenz J, and Methner A. Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease CMT4A: GDAP1 increases cellular glutathione and the mitochondrial membrane potential. Hum Mol Genet 21: 150–162, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nunez MT, Urrutia P, Mena N, Aguirre P, Tapia V, and Salazar J. Iron toxicity in neurodegeneration. Biometals 25: 761–776, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]