ABSTRACT

The detailed information between plasma N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) concentrations and dogs with pulmonic stenosis (PS) is still unknown. The aim of the present study was to investigate the clinical utility of measuring plasma NT-proBNP concentrations in dogs with PS and to determine whether plasma NT-proBNP concentration could be used to assess disease severity. This retrospective study enrolled 30 client-owned, untreated dogs with PS (asymptomatic [n=23] and symptomatic [n=7]) and 11 healthy laboratory beagles. Results of physical examination, thoracic radiography and echocardiography were recorded. Plasma NT-proBNP concentrations were measured using commercial laboratories. Compared to the healthy control dogs, cardiothoracic ratio was significantly increased in dogs with both asymptomatic and symptomatic PS. Similarly, the ratio of the main pulmonary artery to aorta was significantly decreased in dogs with both asymptomatic and symptomatic PS. The pulmonic pressure gradient in the symptomatic PS dogs was significantly higher than that in the asymptomatic PS dogs. Plasma NT-proBNP concentration was significantly elevated in the symptomatic PS dogs compared to the healthy control dogs and the asymptomatic PS dogs. Furthermore, the Doppler-derived pulmonic pressure gradient was significantly correlated with the plasma NT-proBNP concentration (r=0.78, r2=0.61, P<0.0001). Plasma NT-proBNP concentration >764 pmol/l to identify severe PS had a sensitivity of 76.2% and specificity of 81.8%. The plasma NT-proBNP concentration increased by spontaneous PS, i.e. right-sided pressure overload and can be used as an additional method to assess the severity of PS in dogs.

Keywords: BNP, canine, natriuretic peptide, NT-proBNP, pulmonic stenosis

Pulmonic stenosis (PS) is a common congenital heart disease in dogs, which can be classified into 3 types including subvalvular, valvular or supravalvular stenosis [10, 17]. Of these, the valvular stenosis is the most commonly recognized congenital form of PS [9]. In severe cases, it results in right-sided heart failure and causes the clinical symptom, such as exercise intolerance and syncope [4, 11]. Echocardiographic examination is essential method to diagnose the PS in dogs [10, 17]. Continuous wave Doppler is using to assess the pressure gradient (PG) across the pulmonic valve, which indicates the severity of stenosis [9, 14, 21, 28]. The main limitation of Doppler-derived PG is that they require a high technique of echocardiography. In addition, clinical examination might be difficult in case of excitation, panting or need of emergency cardiac treatment. Thus, there is a pressing need for a simpler tool to determine the hemodynamic severity of PS in dogs.

B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) consists of 32 amino acids and is involved in the regulation of body fluid homeostasis and blood pressure [22]. A precursor protein is produced in the ventricular myocardium in response to wall stretching and cleaved into BNP and inactive N-terminal proBNP (NT-proBNP) before secretion [16, 22]. Previous studies have reported that the plasma BNP and NT-proBNP concentration increased in dogs with left-sided heart failure, which provide the information related to the disease severity and prognosis of heart failure [6, 7, 20, 25]. Similarly, Baumwart et al. reported that the plasma BNP concentration increased in Boxers with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy [1]. Thus, measurement of plasma NT-proBNP concentration is expected as a simpler tool to determine the severity of heart failure in dog.

Ventricular pressure overload is thought to be a cause of synthesis and secretion of BNP and NT-proBNP from ventricle into circulation [5, 13, 27]. Previous human medical studies showed that plasma BNP concentrations were elevated in patients with asymptomatic right ventricular (RV) pressure overload compared to the healthy subjects [26]. Plasma BNP concentrations correlated negatively with ejection fraction and positively with mean pulmonary artery pressure and RV end-diastolic pressure [15, 18]. Because PS causes RV pressure overload [19], these results lead to the speculation that measurements of plasma NT-proBNP concentrations can be useful to diagnose and estimate the severity of PS in dogs. However, the detailed information between plasma NT-proBNP concentrations and dogs with PS is still unknown. The purpose of the present study reported here was to investigate the clinical utility of measuring plasma NT-proBNP concentrations to predict the severity of PS in dogs.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Dogs: All the 41 dogs of the study (11 healthy laboratory beagles and 30 dogs with PS) were examined between April 2010 and April 2013 at the Chimura Veterinary Hospital and Kitasato University Veterinary Teaching Hospital. The study followed the guideline for Institutional Laboratory Animal Care and Use of the School of Veterinary Medicine at Kitasato University, Japan.

Clinically healthy dogs were recruited from healthy laboratory beagles. Beagle dogs of both genders (3 males and 8 females), aged 2.0–8.0 years and weighing 8.8–13.0 kg, were enrolled as study subjects. These dogs were determined to be healthy on the basis of physical examinations, thoracic radiography and echocardiography.

Dogs with PS were enrolled based on the results of physical examination, thoracic radiography and echocardiography. Owners provided informed consent before their dogs participated in the study. Inclusion criteria for thirty dogs with PS were presence of systolic murmur and confirmation of the diagnosis by echocardiography. All owners were asked detailed questions on whether dogs had received previous treatment for PS. Untreated dogs with PS were enrolled in the present study. These dogs were divided into asymptomatic PS and symptomatic PS groups according to presence or absence of clinical symptoms (i.e. syncope and overt exercise intolerance). Exclusion criteria for the study were other heart diseases, infection and systemic diseases. After all examinations were completed, if necessary, dogs received medical treatment for PS.

Thoracic radiography and echocardiography: Cardiothoracic ratio and vertebral heart score were evaluated using thoracic radiography according to the method described previously [3, 12]. Echocardiographic examinations were performed by 2 experienced sonographers (YH and SC) using ultrasonographic unit with a 7.5 to 12-MHz probe. Echocardiographic examinations were performed without sedation or anesthesia in a quiet examination room. Echocardiographic diagnosis of PS was made on the basis of morphological abnormality and color flow Doppler echocardiographic evidence of abnormal flow. The ratio of the main pulmonary artery to aorta (PA/Ao) was measured in the right parasternal short-axis view. PA/Ao ratio was obtained at the Q wave or the onset of QRS complex of the electrocardiography. Peak systolic pulmonary flow velocities were measured using continuous wave Doppler echocardiography with the sample volume positioned at the tip of the pulmonic valve leaflets in the right parasternal short-axis view. The size of the Doppler sample volume was set at an axial length of 2 mm. The trans-pulmonic valve PG was calculated by modified Bernoulli’s equation (PG=4 × (peak PS velocity2) [28].

Plasma NT-proBNP measurements: Blood samples for determining of NT-proBNP concentrations were collected from the jugular vein. The blood samples were collected in an ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid tube containing aprotinin and centrifuged immediately for 15 min at 4°C and 3,500 rpm, and the plasma was separated and stored at −80°C until the assays were performed. Plasma NT-proBNP concentrations were measured using an enzyme immunoassay for canine NT-proBNP by commercial laboratories (Cardiopet proBNP, IDEXX Laboratories, Westbrook, ME, U.S.A.). The maximum assay sensitivity of NT-proBNP was 3,000 pmol/l. Plasma NT-proBNP concentration over measurement limit was deemed 3,000 pmol/l, because of statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis: All values are expressed as median [min-max]. A Kruskal-Wallis test was used to analyze distributed data among groups (age, body weight, radiographic measurements, echocardiographic measurements and plasma NT-proBNP concentrations) followed by Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to determine statistical significance between asymptomatic group and symptomatic group in the PS flow velocity and pulmonic PG. Spearman’s nonparametric correlation analysis was applied to compare the pulmonic PG with the plasma NT-proBNP concentrations, radiographic measurements or echocardiographic measurements. Stepwise regression analysis was used to determine the pulmonic PG that correlated best with specific Doppler variables. Values of F>2.0 were considered significant. Receiver-operating characteristic analyses were used to assess the predictive accuracy of plasma NT-proBNP concentrations for identification of dogs with severe PS (pulmonic PG>70 mmHg) [10, 11]. We determined the cutoff value that resulted in the highest sensitivity and specificity. A value of P<0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

The study population of thirty dogs consisted of 8 Chihuahuas; 7 Pomeranians; 6 French Bulldogs; 2 mixed-breed dogs and the remaining dogs represented 7 other breeds. These dogs were divided into 2 groups based on clinical signs: asymptomatic (n=23) and symptomatic (n=7). Although the diagnosis could be obtained from results of B-mode with color Doppler flow echocardiography and pulmonic PG, there were not recorded the PA/Ao ratio at five dogs: asymptomatic (n=3) and symptomatic (n=2). The distribution of the sex, age and physical examination among the groups is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. The distribution of the sex, age and physical examination among the groups.

| Healthy controls | Asymptomatic | Symptomatic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male/Female | 3/8 | 15/8 | 5/2 |

| Age (years) | 6.0 [2.0–8.0] | 0.9 [0.3–5.6]‡ | 0.5 [0.3–3.0]† |

| Body weight (kg) | 10.4 [8.8–13.0] | 2.3 [1.0–14.7]‡ | 4.4 [1.2–14.0] |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 108 [88–132] | 122 [80–190] | 142 [76–193] |

| Murmur Grade (II/III/IV/V) | - | 5/13/4/1 | 0/5/1/1 |

All data are described as median values [min-max]. †; P<0.01 vs. healthy controls, ‡; P<0.001 vs. healthy controls.

Thoracic radiographic and echocardiographic data among groups are shown in Table 2. The vertebral heart score was not changed among groups. In contrast, cardiothoracic ratio was significantly higher in the asymptomatic and symptomatic PS dogs than in the healthy control dogs (each P<0.001). The PA/Ao ratio was significantly decreased in dogs with asymptomatic and symptomatic PS dogs, compared with the healthy control dogs (each P<0.01). Both PS flow velocity and pulmonic PG in the symptomatic PS dogs were significantly higher than those in the asymptomatic PS dogs (each P<0.005).

Table 2. Comparison of radiographic and echocardiographic variables among groups.

| Healthy controls (n) | Asymptomatic (n) | Symptomatic (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vertebral heart score | 10.0 [8.8–10.3] (11) | 10.5 [9.0–19.0] (22) | 11.5 [9.0–16.0] (7) |

| Cardiothoracic ratio (%) | 47.9 [44.3–53.3] (11) | 61.5 [49.8–74.1]‡ (21) | 72.9 [52.1–84.3]‡ (7) |

| PA/Ao ratio | 0.99 [0.88–1.18] (10) | 0.83 [0.50–1.13]† (20) | 0.79 [0.60–0.91]† (5) |

| PS flow velocity (m/s) | - | 4.9 [2.1–7.6] (23) | 6.3 [4.9–7.2]§ (7) |

| Pulmonic PG (mmHg) | - | 97.6 [17–228] (23) | 161 [96–206]§ (7) |

All data are described as median values [min-max]. PA/Ao ratio, the ratio of the pulmonary artery to the aorta; PS, Pulmonic stenosis; PG, pressure gradient. †; P<0.01 vs. healthy controls, ‡; P<0.001 vs. healthy controls, §; P<0.005 vs. asymptomatic PS.

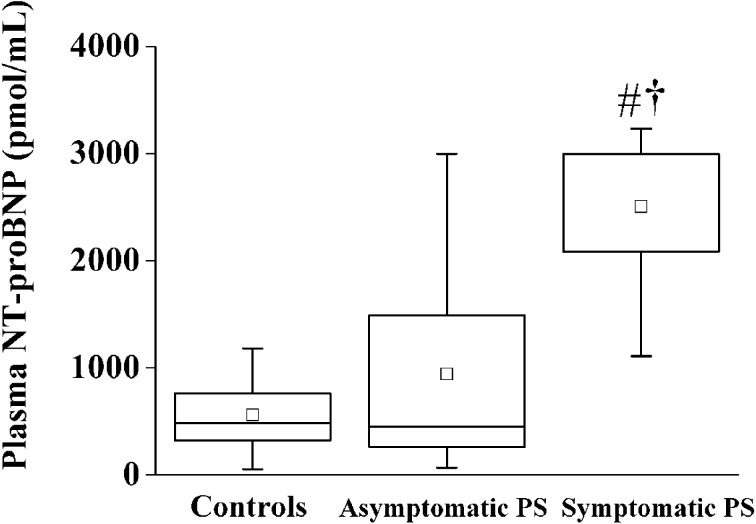

Compared with the healthy dogs, plasma NT-proBNP concentration was significantly elevated in the symptomatic PS dogs (485 [55–1,181] pmol/l vs. 3,000 [1,108–3,000] pmol/l; P<0.01), whereas plasma NT-proBNP concentration in the asymptomatic PS dogs was insignificantly elevated (450 [50–3,000] pmol/l; Fig. 1). Furthermore, plasma NT-proBNP concentration was significantly higher in the symptomatic PS dogs than in the asymptomatic PS dogs (P<0.01).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of the plasma NT-proBNP concentrations among groups. The plasma NT-proBNP concentration was significantly higher in the symptomatic PS group than in the healthy controls and the asymptomatic PS groups. The plasma NT-proBNP concentration in the asymptomatic PS group was insignificantly higher than the healthy controls group. †; P<0.01 vs healthy controls, #; P<0.01 vs asymptomatic PS.

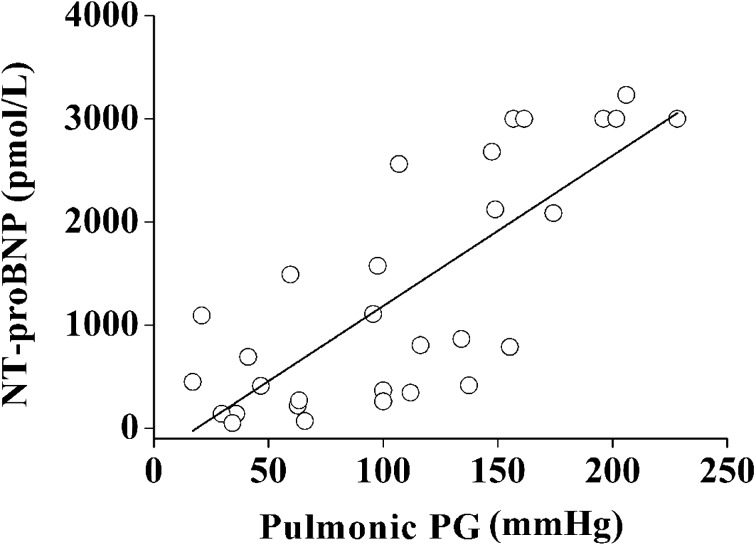

The pulmonic PG, which indicates hemodynamic severity of stenosis [23], was not correlated with vertebral heart score and PA/Ao ratio. In contrast, the pulmonic PG was positively correlated with cardiothoracic ratio (r=0.46, P<0.013; Table 3). Moreover, the pulmonic PG was highly correlated with the plasma NT-proBNP concentration (r=0.78, r2=0.61, P<0.0001; Fig. 2). Stepwise regression analysis revealed that the plasma NT-proBNP concentration (F=2.5) and cardiothoracic ratio (F=2.1) could be used to predict the pulmonic PG (r2=0.71; P<0.0001). Sensitivity and specificity for identifying dogs with severe PS (PG>70 mmHg) at cutoff values were determined. Use of a plasma NT-proBNP concentration>764 pmol/l to identify severe PS had a sensitivity of 76.2% and specificity of 81.8%. The area under the curve of plasma NT-proBNP was 0.83 (95% confidence interval, 0.68 to 0.93; P<0.0001).

Table 3. Correlation between the pulmonic PG and radiographic measurements, echocardiographic measurements or plasma NT-proBNP concentrations in the dogs with PS.

| n | r | r2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiothoracic ratio | 28 | 0.46 | 0.21 | 0.013 |

| Vertebral heart score | 29 | –0.001 | <0.001 | 0.99 |

| PA/Ao ratio | 25 | –0.005 | 0.003 | 0.81 |

| NT-proBNP | 30 | 0.78 | 0.61 | <0.0001 |

PA/Ao ratio, the ratio of the pulmonary artery to the aorta; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide.

Fig. 2.

Correlation between the pulmonic PG and the plasma NT-proBNP concentration. The pulmonic PG was highly correlated with the plasma NT-proBNP concentrations (r=0.78, r2=0.61, P<0.0001).

DISCUSSION

The stenosed pulmonic valve is well recognized to increase the RV systolic pressure, which induces RV pressure overload [10, 19]. In addition, human patients with RV pressure overload, i.e. transposition of the great arteries, tetralogy of Fallot and PS, are known to induce significant elevation of the plasma BNP concentration [15, 26]. Even if mild RV pressure overload (RV systolic pressure over 35 mmHg), plasma concentration of BNP in the human patients was significantly higher than that of the healthy controls [26]. These results suggest that ventricular pressure overload stimulate the synthesis and secretion of BNP and NT-proBNP into circulation [5, 13, 27]. Although Saunders et al. reported that serum concentration of cardiac troponin I increased in 7 of 23 dogs with severe PS [23], however, no information has previously been reported regarding plasma NT-proBNP concentrations in dogs with PS. In the present study, we firstly demonstrated that plasma NT-proBNP concentration in dogs with symptomatic PS was significantly higher than those of healthy controls and dogs with asymptomatic PS. These results suggest that PS is one of the causes to elevate circulating NT-proBNP in dogs, and plasma NT-proBNP concentration is elevated in sympathetic dogs with PS.

The hemodynamic severity of stenosis is most important information to assess the disease severity and prognosis of PS in human patients and dogs [10, 24], which can be determined by cardiac catheterization or echocardiography. However, invasive assessment is uncommonly available in veterinary medicine, because they require general anesthesia and carry a risk of life-threatening complications. In contrast, the continuous wave Doppler-derived peak PG system, which measures the PG across the pulmonic valve as an indirect assessment of hemodynamics [8, 14, 21, 28], is essential method to diagnose the severity of PS in dogs [10, 17]. Francis et al. reported that the Doppler-derived PG increases in proportion to the degree of PS in dogs [10]. Doppler-derived PG of more than 60 mmHg is related to poor prognosis [4, 10, 11] and was associated with 86% sensitivity and 71% specificity of predicting cardiac death in dogs with PS [10]. In our present study, the pulmonic PG in the dogs with symptomatic PS was significantly higher than that in the asymptomatic PS, which was supported by previous studies [4, 10, 11]. Furthermore, we firstly demonstrated that the plasma NT-proBNP concentration in the PS dogs was highly correlated with the pulmonic PG. Stepwise regression analysis revealed that the plasma NT-proBNP concentration and cardiothoracic ratio could be used to predict the pulmonic PG. Use of a plasma NT-proBNP concentration >764 pmol/l to identify severe PS had a sensitivity of 76.2% and specificity of 81.8%. These results indicate that the plasma NT-proBNP concentration is useful for assessment of the hemodynamic severity of PS in dogs.

Limitations: Because our retrospective study was limited by the small sample size and we could not exclude the possibility that differences of breed and body weight may have affected the results, a study with a larger sample size will be required. In addition, because the pulmonic PG to assess pulmonic stenosis will lead to a systematic overstatement of the severity of the stenosis [24], a precise hemodynamics, i.e. invasive hemodinamic data, is required to discuss detailed relationship with the plasma NT-proBNP concentraiton. The effects of PS on the plasma NT-proBNP concentrations should be interpreted with caution, because several factors affect serum NT-proBNP concentrations, including systemic pressure, age and renal function [2, 5].

Conclusions: Plasma NT-proBNP concentration in dogs with symptomatic PS was significantly higher than those of healthy controls and dogs with asymptomatic PS. Furthermore, the plasma NT-proBNP level was significantly correlated with the pulmonic PG. Our results suggested that the plasma NT-proBNP concentration can be used as an additional method to assess the hemodynamic severity of PS. A further study will be required to determine the diagnostic value, sensitivity and specificity to assess severity of PS in dogs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baumwart R. D., Meurs K. M.2005. Assessment of plasma brain natriuretic peptide concentration in Boxers with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Am. J. Vet. Res. 66: 2086–2089. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2005.66.2086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boswood A., Dukes-McEwan J., Loureiro J., James R. A., Martin M., Stafford-Johnson M., Smith P., Little C., Attree S.2008. The diagnostic accuracy of different natriuretic peptides in the investigation of canine cardiac disease. J. Small Anim. Pract. 49: 26–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buchanan J. W., Bücheler J.1995. Vertebral scale system to measure canine heart size in radiographs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 206: 194–199 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bussadori C., DeMadron E., Santilli R. A., Borgarelli M.2001. Balloon valvuloplasty in 30 dogs with pulmonic stenosis: effect of valve morphology and annular size on initial and 1-year outcome. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 15: 553–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2001.tb01590.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cemri M., Arslan U., Kocaman S. A., Cengel A.2008. Relationship between N-terminal pro-B type natriuretic peptide and extensive echocardiographic parameters in mild to moderate aortic stenosis. J. Postgrad. Med. 54: 12–16. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.39183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chetboul V., Serres F., Tissier R., Lefebvre H. P., Sampedrano C. C., Gouni V., Poujol L., Hawa G., Pouchelon J.2009. Association of plasma N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide concentration with mitral regurgitation severity and outcome in dogs with asymptomatic degenerative mitral valve disease. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 23: 984–994. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2009.0347.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeFrancesco T. C., Rush J. E., Rozanski E. A., Hansen B. D., Keene B. W., Moore D. T., Atkins C. E.2007. Prospective clinical evaluation of an ELISA B-type natriuretic peptide assay in the diagnosis of congestive heart failure in dogs presenting with cough or dyspnea. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 21: 243–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2007.tb02956.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dennis S.2012. Evidence for increased probability of cardiac death in dogs with pulmonic stenosis questionable. J. Small Anim. Pract. 53: 304–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2011.01196.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fingland R. B., Bonagura J. D., Myer C. W.1986. Pulmonic stenosis in the dog: 29 cases (1975–1984). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 189: 218–226 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Francis A. J., Johnson M. J., Culshaw G. C., Corcoran B. M., Martin M. W., French A. T.2011. Outcome in 55 dogs with pulmonic stenosis that did not undergo balloon valvuloplasty or surgery. J. Small Anim. Pract. 52: 282–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2011.01059.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson M. S., Martin M., Edwards D., French A., Henley W.2004. Pulmonic stenosis in dogs: balloon dilation improves clinical outcome. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 18: 656–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2004.tb02602.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamlin R. L.1968. Analysis of the cardiac silhouette in dorsoventral radiographs from dogs with heart disease. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 153: 1446–1460 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hori Y., Tsubaki M., Katou A., Ono Y., Yonezawa T., Li X., Higuchi S. I.2008. Evaluation of NT-pro BNP and CT-ANP as markers of concentric hypertrophy in dogs with a model of compensated aortic stenosis. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 22: 1118–1123. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2008.0161.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Houston A. B., Sheldon C. D., Simpson I. A., Doig W. B., Coleman E. N.1985. The severity of pulmonary valve or artery obstruction in children estimated by Doppler ultrasound. Eur. Heart J. 6: 786–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagaya N., Nishikimi T., Okano Y., Uematsu M., Satoh T., Kyotani S., Kuribayashi S., Hamada S., Kakishita M., Nakanishi N., Takamiya M., Kunieda T., Matsuo H., Kangawa K.1998. Plasma brain natriuretic peptide levels increase in proportion to the extent of right ventricular dysfunction in pulmonary hypertension. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 31: 202–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morello A. M., Januzzi J. L.2006. Amino-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide: a biomarker for diagnosis, prognosis and management of heart failure. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 6: 649–662. doi: 10.1586/14737159.6.5.649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oliveira P., Domenech O., Silva J., Vannini S., Bussadori R., Bussadori C.2011. Retrospective review of congenital heart disease in 976 dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 25: 477–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2011.0711.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oosterhof T., Tulevski I. I., Vliegen H. W., Spijkerboer A. M., Mulder B. J.2006. Effects of volume and/or pressure overload secondary to congenital heart disease (tetralogy of fallot or Pulmonary Stenosis) on right ventricular function using cardiovascular magnetic resonance and B-type natriuretic peptide levels. Am. J. Cardiol. 97: 1051–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.10.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orito K., Yamane T., Kanai T., Fujii Y., Wakao Y., Matsuda H.2004. Time course sequences of angiotensin converting enzyme and chymase-like activities during development of right ventricular hypertrophy induced by pulmonary artery constriction in dogs. Life Sci. 75: 1135–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oyama M. A., Fox P. R., Rush J. E., Rozanski E. A., Lesser M.2008. Clinical utility of serum N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide concentration for identifying cardiac disease in dogs and assessing disease severity. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 232: 1496–1503. doi: 10.2460/javma.232.10.1496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richards K. L.1991. Assessment of aortic and pulmonic stenosis by echocardiography. Circulation 84 (Suppl. 3): 182–187 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruskoaho H.2003. Cardiac hormones as diagnostic tools in heart failure. Endocr. Rev. 24: 341–356. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saunders A. B., Smith B. E., Fosgate G. T., Suchodolski J. S., Steiner J. M.2009. Cardiac troponin I and C-reactive protein concentrations in dogs with severe pulmonic stenosis before and after balloon valvuloplasty. J. Vet. Cardiol. 11: 9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jvc.2009.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silvilairat S., Cabalka A. K., Cetta F., Hagler D. J., O’Leary P. W.2005. Echocardiographic assessment of isolated pulmonary valve stenosis: which outpatient Doppler gradient has the most clinical validity? J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 18: 1137–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.03.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takemura N., Toda N., Miyagawa Y., Asano K., Tejima K., Kanno N., Arisawa K., Kurita T., Nunokawa K., Hirakawa A., Tanaka S., Hirose H.2009. Evaluation of plasma N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NTproBNP) concentrations in dogs with mitral valve insufficiency. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 71: 925–929. doi: 10.1292/jvms.71.925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tulevski I. I., Groenink M., van Der Wall E. E., van Veldhuisen D. J., Boomsma F., Stoker J., Hirsch A., Lemkes J. S., Mulder B. J.2001. Increased brain and atrial natriuretic peptides in patients with chronic right ventricular pressure overload: correlation between plasma neurohormones and right ventricular dysfunction. Heart 86: 27–30. doi: 10.1136/heart.86.1.27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoshimura M., Yasue H., Okumura K., Ogawa H., Jougasaki M., Mukoyama M., Nakao K., Imura H.1993. Different secretion patterns of atrial natriuretic peptide and brain natriuretic peptide in patients with congestive heart failure. Circulation 87: 464–469. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.87.2.464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Valdes-Cruz L. M., Horowitz S., Sahn D. J., Larson D., Oliveira L. C., Mesel E.1984. Validation of a Doppler echocardiographic method for calculating severity of discrete stenotic obstructions in a canine preparation with a pulmonary arterial band. Circulation 69: 1177–1181. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.69.6.1177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]