Abstract

Social isolation (SI) has been linked epidemiologically to high rates of morbidity and mortality following stroke. In contrast, strong social support enhances recovery and lowers stroke recurrence. However, the mechanism by which social support influences stroke recovery has not been adequately explored. The goal of this study was to examine the effect of post-stroke pair housing and SI on behavioural phenotypes and chronic functional recovery in mice. Young male mice were paired for 14 days before a 60 minute transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) or sham surgery and assigned to various housing environments immediately after stroke. Post-stroke mice paired with either a sham or stroke partner showed significantly higher (p<0.05) sociability after MCAO than isolated littermates. Sociability deficits worsened over time in isolated animals. Pair-housed mice showed restored sucrose consumption (p<0.05) and reduced immobility in the tail suspension test compared to isolated cohorts. Pair-housed stroked mice demonstrated significantly reduced cerebral atrophy after 6 weeks (17.5 ± 1.5% in PH vs. 40.8 ± 1.3% in SI; p<0.001). Surprisingly, total brain arginase-1, a marker of a M2 “alternatively activated” myeloid cells was higher in isolated mice. However, a more detailed assessment of cellular expression showed a significant increase in the number of microglia that co-labeled with arginase-1 in the peri-infarct region in PH stroke mice compared to SI mice. Pair housing enhances sociability and reduces avolitional and anhedonic behaviour. Pair housing reduced serum IL-6 and enhanced peri-infarct microglia arginase-1 expression. Social interaction reduces post-stroke depression and improves functional recovery.

Keywords: Sociability, Ischemic Stroke, Social Isolation, Post stroke depression, Arginase-1, IL-6

1. Introduction

Social support is one of the most recognized psychological factors influencing recovery from disease [1, 2] and has the potential to alleviate maladaptive psychological responses to stress [3]. In contrast, social isolation (SI) exacerbates disease and slows recovery. Absence of social interaction has been linked epidemiologically with high mortality rates following various pathological stressors including stroke [4]. Social isolation and feelings of loneliness not only increase the risk of death but also delays recovery [5]. Social interaction has well documented health benefits in humans and can be easily assessed in the clinic by tools such as the UCLA loneliness scale [6]. However, discovering the biological mechanisms underlying the benefits of social interaction requires the development of pre-clinical animal studies. Although reproducing social behaviour in mice has limitations, there are many advantages [7].

As not all strokes can be prevented, evaluating the influence of social and emotional factors on stroke recovery is an important area of research. Depression and anxiety are common clinical findings after stroke, with up to 40% of stroke survivors affected [8]. These behavioural deficits have been associated with higher levels of disability and lower levels of social support [9, 10]. Post-stroke depression (PSD) leads to increased cognitive deficits, sexual dysfunction, anhedonia, feelings of despair and social withdrawal [11-15]. These disturbances not only affect the overall well-being of patients but also confound the recovery process by leading to further isolation. SI is predicted by depressive symptomatology using the geriatric depression scale (GDS) in clinical populations [16, 17]. However, no such scale or validated behavioural paradigms to measure complex behaviour changes after stroke exists for rodent stroke models. Historically, the lack of appropriate behavioural quantification and analysis has been a major limiting factor in drug development for stroke[18].

Housing conditions prior to an induced stroke are a strong determinant of long-term survival in mice. Mice pair housed prior to injury had a 100% survival rate after 7 days in contrast to a 40% survival rate among isolated animals [19]. The detrimental effects of social isolation on infarct volume and behavioural recovery were evident in both sexes [20]. However, many studies have examined isolation prior to stroke, and focused on motor recovery and survival at acute endpoints. Therefore in this study we analyzed and validated behavioural changes after stroke in long term survival cohorts with a focus on depressive behaviour.

Emerging evidence indicates a relationship between SI and systemic inflammation [19]. Clinical studies have shown that plasma levels of inflammatory cytokines were increased after stroke [21]. Immune cells, most notably resident microglia or peripheral macrophages that migrate to the area of ischemic injury also participate in pathological changes during stroke by releasing various pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines [22-24]. Microglia/macrophages are highly plastic cells that can assume diverse phenotypes in response to specific micro-environmental signals [23-25]. These macrophages and/or resident microglia may either contribute to damage or enhance repair in the brain [25]. These divergent effects in the brain are mediated by distinct macrophage subsets, i.e., “classically activated” proinflammatory (M1) or “alternatively activated” anti-inflammatory (M2) cells. Their phenotype is dependent on the cytokine environment present during macrophage activation [23]. Myeloid cells are divided into these two distinct phenotypes based in part upon L-Arginine metabolism. M1 (or classically activated) cells express high levels of iNOS and low levels of Arginase-1 and participate in the clearance of intracellular pathogens. Conversely, M2 (alternatively activated) myeloid cells express the reverse pattern, and are involved in repair [26]. In this study, chronic behavioural changes induced by pair housing, and the potential contribution of microglia/macrophages to post-stroke depressive phenotypes were examined.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Experimental animals

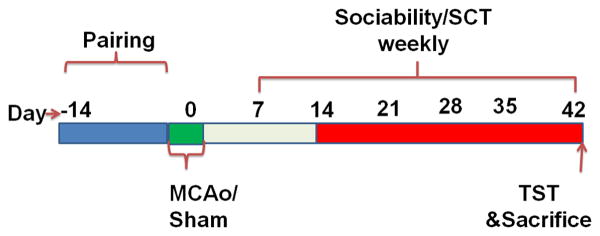

All animal protocols were approved by the University's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington, CT and were performed in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines. Six-week-old C57Bl/6 male mice were purchased from Harlan laboratories, USA. All mice were maintained in an ambient temperature and humidity controlled vivarium with ad libitum access to food and water. After arrival, the mice were acclimatized in the animal care facility for two weeks in their original groups. Thereafter, all mice were randomly housed in groups of 2 mice per cage for an additional two weeks. During pair housing all the mice were examined daily for compatibility (observed for fighting, or the failure to gain weight in either partner). After two weeks of pair housing all mice were subjected to stroke or sham surgery. Immediately after surgery, mice were randomly assigned to one of six groups using a two way factorial design. Surgical condition (sham (SH) or stroke (ST)), was the first between-subjects factor and housing condition (housed with sham (SH), housed with stroke (ST) or housed in isolation (ISO), was the second between-subjects factor [27]. Thus, the six groups were: SHcSH (n = 6), SHcST (n = 8), SH ISO (n = 7), STcSH (n = 8), STcST (n = 8), and ST ISO (n = 9). Mice remained in these housing conditions throughout the experiment (Fig 1). If any mice died during the experiments, all of the subjects housed in the same cage were excluded from the study. The experiments were conducted in two separate cohorts. In the first cohort behavioural deficits (Sociability, SCT and TST tasks) were assessed at one time point, 6 weeks after stroke. In the second cohort the mice were tested (Sociability, SCT) weekly through 6 weeks with testing initiated at day 7 after MCAO [Number of animals/group; ST-PH (n = 10), SH-ISO (n = 6), SH-PH (n = 8), and ST ISO (n = 7); detail for groups is described in result section 3.1].

Fig. 1.

Schematic of experimental design and behavioural testing (Cohort 2).

2.2 Stroke model

In all stroke groups, transient focal cerebral ischemia was induced in mice (20 to 25 g) by 60 min of transient right middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) under isoflurane anesthesia followed by reperfusion as described previously [28, 29]. Briefly, a midline ventral neck incision was made, and unilateral right MCAO was performed by advancing a 6-0 silicone-coated nylon monofilament (Doccol Corporation, CA) into the internal carotid artery 6 mm from the internal carotid artery bifurcation via an external carotid artery stump. Rectal temperatures were monitored with a temperature control system (Fine Science Tools, Canada) and temperature was maintained with an automatic heating pad at ∼37 °C during surgery. Cerebral blood flow measurements by Laser Doppler Flowmetry (DRT 4/Moor Instruments Ltd, Devon, UK) confirmed ischemic occlusion (reduction to 15% of baseline) during MCAO and restoration of blood flow during reperfusion. In sham mice, an identical surgery was performed except the suture was not advanced into the internal carotid artery.

2.3 Assessment of Social Interaction/ Sociability

The three-chamber paradigm, established by Crawley and colleagues [30] has been used to examine mouse sociability in models of autism and other psychiatric disorders. We used this paradigm to study PSD in PH vs. ISO mice with minor modifications. In the first cohort sociability was assessed at 6 weeks after MCAO. In the second cohort, social behaviour was tested at several time points after stroke, each at 7 day intervals through 6 weeks with testing initiated at day 7 after stroke.

The social testing apparatus was comprised of a rectangular, three-chambered Plexiglas box (22 inch L × 16 inch W × 9 inch H). Dividing walls had a single rectangular opening 2Wx2L inches in diameter allowing access into each chamber (Supp Fig.1). Initially, the test mouse was habituated to the test chamber for 5 minutes. In this habituation phase the mouse had full access to both sides of the chamber each containing an empty round wire cage. After this habituation period, the test mouse was returned to its home cage and the test chamber was cleaned with 70% alcohol. A stranger mouse of the same sex that had no prior contact with the test mouse was then placed under a round wire cage within the right chamber of the testing apparatus. The wire cage effectively allows for nose contact between mice but prevents fighting or further direct interaction. At this point the test mouse was re-introduced into the middle chamber and allowed to explore the entire testing apparatus for a 10 minute session.

Parameters recorded include the % time spent in right chamber (the chamber with the stranger mouse), and the total interaction time (Time spent during direct contact between the test mouse and the containment cup with the stranger mouse, or stretching of the body of the test mouse in an area 3 cm around the cup) with the stranger mouse. [31] Top scan software was used to record these variables and to track the test mouse's movement (Top scan, Clever Sys Inc. Reston, Virginia)

2.4 Tail Suspension Test

(TST): The tail suspension test (TST) was performed as described previously [32] with minor modifications. Briefly, the mice were individually suspended from the tail suspension apparatus, 60 cm above the surface of the table. The experiment was recorded for 6 minutes using a digital video camera (JVC Everio, Victor Company, Japan). A trained observer that was blinded to the housing and surgical group then recorded the duration of immobility. The mouse was considered immobile in the absence of initiated movement. In general, an immobile mouse will appear to hang passively unless it has retained momentum from a movement immediately prior to the current bout of immobility. The testing apparatus was cleaned between trials to remove olfactory cues.

2.5 Sucrose Consumption Test

The sucrose consumption test (SCT) was performed in two separate cohorts to measure anhedonia. The SCT has been previously used to address post-stroke anhedonia [15]. In this test, mice are presented with the option of consuming either water or a 3% sucrose solution. A preference for sucrose is seen in naive animals [33], whereas mice that have no preference for sucrose solution are considered anhedonic. This is a well validated test for a depressive phenotype, and the lack of preference for sucrose can be restored with anti-depressant treatment [34]. Two identical 10 mL vials were placed on a custom made wire cage top. PH mice were temporarily separated overnight for this test to ensure an accurate measure of consumption for each individual mouse. On the first day of habituation, each individual mouse was provided two 10 mL vials of water for 12 hours. The following morning, all mice were returned to their original housing condition and provided their normal drinking water and cage tops. That evening mice were again separated and provided with two 10 mL vials of 3% sucrose overnight (12 hours). After completion of habituation, all PH mice were again returned to their partners and provided their normal drinking water and cage tops. On the day of testing, mice were water deprived in their original housing condition for 6 hours, then separated (if PH) and kept in a new cage with the customized cage top and one 10 mL vial of water and one 10 mL vial of 3% sucrose solution overnight (12 hours). The volume of consumption of both solutions was recorded the following day by an observer blinded to housing condition in both cohorts as per experimental design.

2.6 Tissue and Ventricular Atrophy Analysis

All animals were sacrificed with an overdose of Avertin (250 mg/kg i.p) after completion of experiments. Subsequent to cardiac puncture and blood collection, the mice underwent transcardial perfusion, using cold heparinized PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). The brain was post-fixed overnight in 4% PFA and placed in cryoprotectant (30% sucrose solution) for 72 hours before processing. The brains were then cut into 30-μm free-floating sections on a freezing microtome and every eighth slice was stained by cresyl violet to visualize tissue loss [20]. The slices were photographed and ventricular and tissue atrophy were analyzed using computer software (Sigma scan Pro5) as previously described [35, 36]. Tissue atrophy percentage was calculated by using the following formula: % tissue atrophy = (total ipsilateral tissue/total contralateral tissue) × 100 and was performed by an investigator blinded to treatment.

2.7 Spleen and body weight

Body weight was recorded immediately prior to sacrifice. The spleen was removed after perfusion. The splenic weight at sacrifice was also recorded and normalized to body weight by the following formula: (splenic weight/body weight) × 100.

2.8 Measurement of serum IL-6

Serum Interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels were assessed at sacrifice (after 6 weeks) in the first experimental cohort of mice as per manufacturer's instructions (Mouse IL-6 ELISA Ready-SET-Go!®, eBiosciences Inc, San Diego, CA 92121).

2.9 Whole cell lysis and western blot

Samples were obtained 6 weeks after stroke from the second experimental cohort of mice by rapidly removing the brains, followed by immediate dissection into the right (R; ischemic) and left (L; non-ischemic) hemispheres and flash freezing in 2-methylbutane on dry ice and stored at −80 °C if not used immediately. Samples were homogenized with dounce homogenizers in cold triton lysis buffer (25mM HEPES, 100mM NaCl,1 mM EDTA, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 1mM PMSF, 10mM DTT, 1mM sodium orthovanadate and 1:50 protease inhibitor) and briefly sonicated on ice. Extracts were immediately centrifuged at 14,000×g and frozen at −80°C. Protein concentration was determined by BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Rockford, IL) and subjected to Western Blotting as previously described [37]. A total of 30 μg of protein was loaded in each well and resolved on 4% to 15% SDS electrophoresis gels and transferred to a PVDF (polyvinylidene difluoride membrane). Total myelin, arginase-1 and actin were detected by using their specific antibodies; Myelin Basic Protein (1:1000 Abcam), Arginase-1 (1:1000 BD bioscience) and actin (1:5000, Sigma) respectively. All blots were blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk for 1 hour at room temperature and incubated overnight in primary antibodies at 4 °C in non-fat dry milk. Secondary antibodies (goat anti-rabbit IgG 1:10,000, goat anti-mouse IgG 1:10,000) were used to detect these proteins. Thermo Scientific Super Signal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate was used for signal detection. The densitometry of Western blotting images (n= 5 per group) was performed with computer software (Image J).

2.10 Immunohistochemical Analysis

A standard procedure was utilized for IHC staining on 30-μm sections (experimental cohort1) mounted on Fischer Scientific Superfrost Plus charged slides. Briefly, mounted tissue sections were thoroughly rinsed in 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS). After rinsing antigen retrieval was performed by heating the tissue in a 10 mM sodium citrate buffer at pH 6.2. Tissue sections were incubated for 1 hour in blocking solution (0.3% Triton-X, 5% normal goat serum in 1X PBS) and then incubated overnight in primary antibody at 4°C (Arginase-1 1:100; IBA-1 1:100; GFAP-Cy3 1:500). Following primary antibody incubation, tissue sections were thoroughly rinsed in PBST (0.05% tween 20 in PBS) and were incubated with the appropriate Alexa-Fluor conjugated secondary antibody (1:1000, Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) for 1 hour at room temperature except for GFAP treated tissue. After rinsing in PBST, sections were coverslipped with mounting media (UltraCruz™ Mounting Medium | Santa Cruz Biotech, USA). Three coronal brain sections per mouse (n = 4 per group), taken 0.02, 0.45, and 0.98 mm from bregma, were stained and visualized for quantification at 10x magnification at the core/penumbra junction. To quantify GFAP and IBA-1, MosaiX software was utilized to obtain a full brain section image for cell counting. A blinded observer quantified the Arginase-1, DAPI, and IBA-1 co-expressing cells using Image J software. The average numbers of cells visualized from 3 adjacent regions at the core/penumbra junction were recorded for each mouse.

2.11 Statistics

All data were analyzed and expressed as means ±S.E.M. Measurement of tissue atrophy and other tests with two groups were analyzed with T test. For the two-factor interaction a two-way ANOVA was used with (cohort 2) or without (cohort 1) repeated measures followed by a Bonferroni post hoc test. A probability value of p< 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Investigators performing and analyzing behavioural tests and histological analyses were blinded to housing conditions.

3 Results

3.1 PH mice show increased sociability

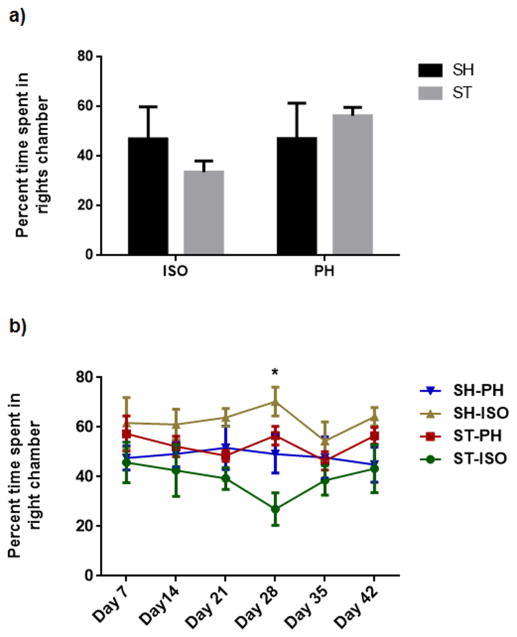

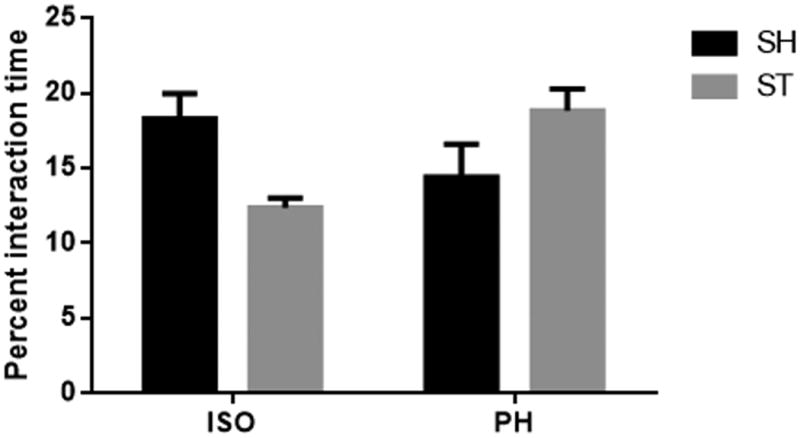

No side preference (right vs. left chamber) was found at baseline or during the habituation period. No significant differences in sociability in stroke mice PH with a healthy partner (STcSH) vs. stroke mice PH with a stroke partner (STcST) was seen (Supplementary fig 2). Similarly there was no significant difference between sham mice pair housed with a stroke (SHcST) or with a healthy partner (SHcSH) (Supplementary fig. 3) Therefore, we pooled STcSH and STcST groups and referred to the collapsed group as the ST-PH group in all subsequent analysis. Similarly, SHcST and SHcSH were also pooled and referred to as the SH-PH group. A significant interaction was found between stroke and housing condition (F (1, 39) = 6.026; P=0.0187) mice at 6 weeks after stroke (cohort 1) (Fig 2 a). Moreover, there was a significant difference between ST-ISO and ST-PH mice (P=0.0185). When the changes in sociability were followed over time in cohort 2, we found that the sociability index was unaffected by housing condition early after stroke (days 7, 14 & 21) but diverged at day 28 (p<0.05), suggesting transient sociability deficits during the chronic phase in ST-ISO mice. A two-factor interaction ‘group versus days’ in a repeated measure two-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni post hoc tests showed an overall significant difference between the PH and SI groups (F 3,24 = 5.413 p< 0.01) (Fig 2b). Additionally, a significant interaction was found between stroke and housing conditions in the amount of sniffing time between the test and stranger mice (F 1, 21=5.884, P<0.05). There was no main effect of either stroke or housing condition alone, but ST-ISO mice showed a reduced interaction (sniffing) with stranger mice (Fig 3) compared to ST-PH mice. This data suggest that that housing conditions affect social interaction.

Fig. 2.

A significant interaction was found between stroke and housing condition (F (1, 39) = 6.026; P=0.0187) in mice after 6 weeks of stroke (cohort 1). Moreover, there was a significant difference between ISO and PH mice (P=0.0185) (Fig 2 a). b) A two-factor interaction ‘group versus days’ in the repeated measure two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc tests showed an overall significant difference between the PH and SI groups (F 3,24 = 5.413 p< 0.01)

Fig. 3.

A significant interaction was found between stroke and housing conditions during sniffing time between test and stranger mice (F 1,21=5.884, P<0.05). However there was no main effect of either stroke or housing condition alone in a two way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc tests.

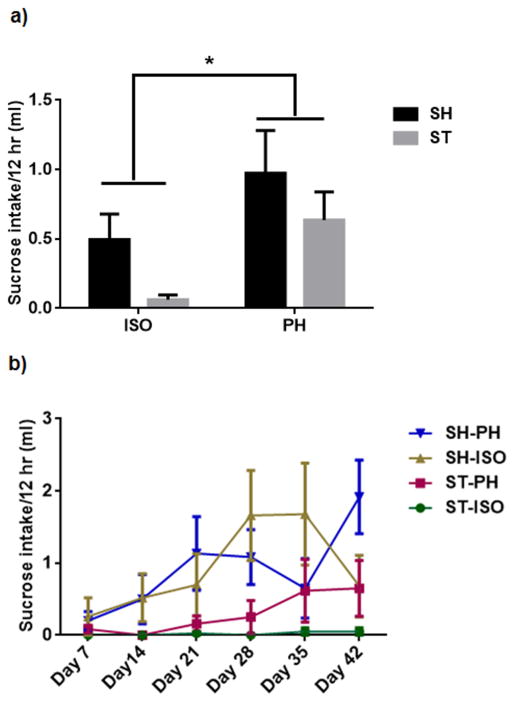

3.2 Pair housing reverses anhedonic behaviour

All stroke animals, regardless of housing condition, showed reduced consumption of sucrose during the acute phase of injury. In cohort 1, ST-ISO mice demonstrated an overall reduction in sucrose consumption as compared to other groups (Supp Fig 4). There was no significant interaction between stroke and housing condition. However, there was a significant effect of housing (P<0.05) in consumption of sucrose, which was independent of stroke (Fig 4 a). No change is water consumption was observed in cohort 1(Supp Fig 5) In cohort 2, both ST-ISO and SH-ISO mice showed a decrease in sucrose consumption, indicating a depressive-type phenotype in isolated animals, regardless of injury. ST-PH mice, by contrast, showed a tendency to recover faster and began drinking earlier after injury compared to all ISO mice. Similar to cohort 1, all PH mice in cohort 2 consumed significantly more sucrose compared to all SI mice. A two-factor interaction ‘group versus days” test showed a significant interaction between groups and days (F18, 102= 1.740, p<0.05). The consumption of sucrose increased significantly in all of the groups in a day dependent manner (p<0.001) (Fig 4 b).

Fig. 4.

Effect of sucrose consumption in mice a) A two way ANOVA with bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons found no significant interaction between housing condition and stroke in sucrose consumption in cohort1 at 6 weeks after stroke. However, there was a significant difference (P<0.05) between ISO and PH group independent of stroke in the consumption of sucrose. b) In repeated testing of sucrose consumption test a two-factor interaction ‘group versus Days’ in the repeated measure two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc tests showed a significant interaction between groups and days (F18, 102= 1.740, p<0.05). The consumption of sucrose increased progressively in both SI and PH groups.

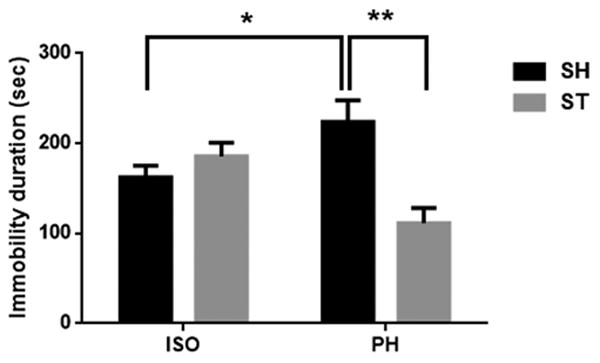

3.3 Isolation increased immobility in the TST

A highly significant interaction (F 1, 21 = 13.81; P = 0.0013) was found between housing conditions and stroke (Fig 5). ISO mice demonstrated significantly increased immobility duration in the TST compared to ST-PH mice after 6 weeks suggesting that avolitional effects of the stroke were modified by housing conditions. Moreover, a significant main effect of stroke (P = 0.0233) was also found. Multiple comparison analysis also revealed that ST-ISO were significantly more immobile as compared to the ST-PH group. Surprisingly, SH-PH showed a highly significant (P<0.01) increase in immobility duration compared to SH-ISO suggesting an independent effect of isolation.

Fig. 5.

Immobility duration was significantly decreased in post stroke PH mice compared to ISO mice (* P<0.05). Interestingly, sham mice pair housed with stroke partner also showed a significant increase in immobility duration (**P<0.01, two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparison test). A significant interaction (F1, 21,=13.81, P<0.01) was also found between housing condition and stroke in two way ANOVA.

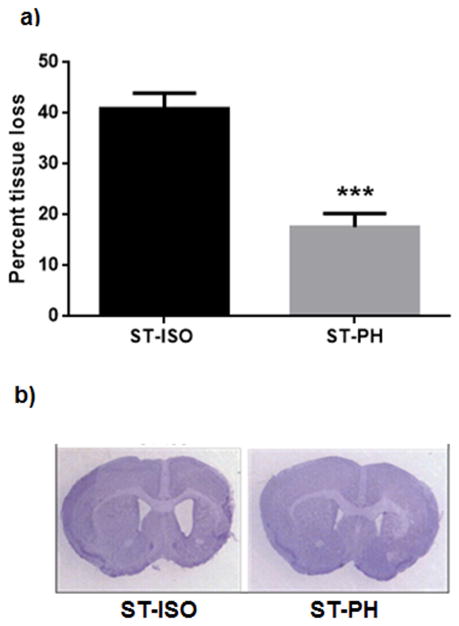

3.4 Ventricular atrophy

A significant loss in brain tissue resulting in ventricular enlargement was found in ST-ISO mice. ST-PH group had significantly less tissue loss compared to ST ISO mice (7.5 ± 1.51% in PH vs. 40.8 ± 1.3% in SI; p<0.001) (Fig 6a). Fig 6b shows a representative coronal section of stroke mice from both PH and SI group at 6 weeks after stroke.

Fig. 6.

(a) Stroke mice paired with healthy partner had significantly less cerebral atrophy. (***P<0.001). (b) Representative coronal section of post stroke ISO and PH brains stained with Cresyl violet.

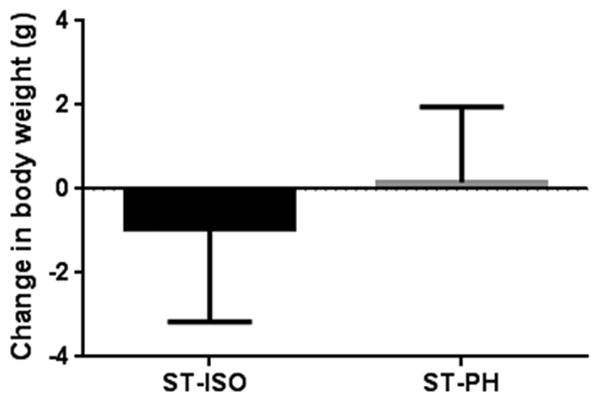

3.5 Changes in spleen and body weight

No differences in spleen weight, spleen/body weight ratios, or body weight between ST-ISO and ST-PH mice after 6 weeks of stroke (Fig 7), suggesting that splenic weight is unaffected by housing condition in the chronic phase.

Fig. 7.

Post stroke PH mice regained their initial body weight after 6 weeks. However, isolated mice did not return to their initial weight even after 6 weeks.

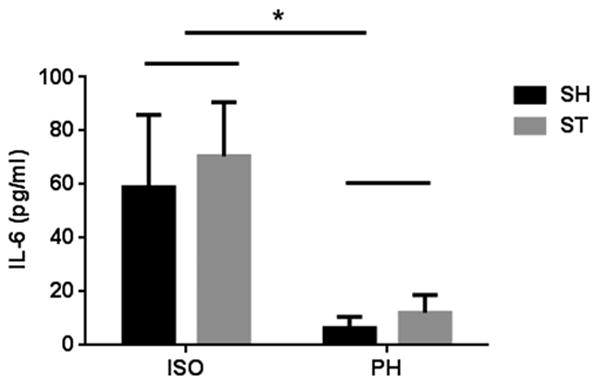

3.6 IL-6 levels

Higher levels of the serum inflammatory biomarker interleukin-6 (IL-6) correlate with poor clinical outcomes in the acute period after ischemic stroke [38], however, little is known about chronic post-stroke changes in IL-6 levels in experimental models. Serum levels of IL-6 in ST-PH mice were lower than those observed in ST-ISO animals 6 weeks after stroke, but this was not statistically significant. A two-way ANOVA test followed by multiple comparisons after Bonferroni correction did not show any significant interaction (F 1, 36 = 0.02826, P = 0.8674) between housing and stroke. However, there was a significant effect of housing (F 1, 36 = 10.31, P = 0.0028) between ISO and PH group on serum IL-6 independent of stroke (Fig 8). This suggests that SI leads to a chronic pro-inflammatory state even in the absence of injury.

Fig. 8.

IL-6 levels were measured in serum collected from mice prior to sacrifice. A two way ANOVA test followed by multiple comparisons after bonferroni correction showed no significant difference between ST-PH and ST-ISO group i.e., there was no stroke effect nor any interaction between housing and stroke (F 1, 36 = 0.02826, P = 0.8674). However there was a significant difference (P<0.05) between ISO and PH group regardless of stroke i.e., isolation increased IL-6 levels.

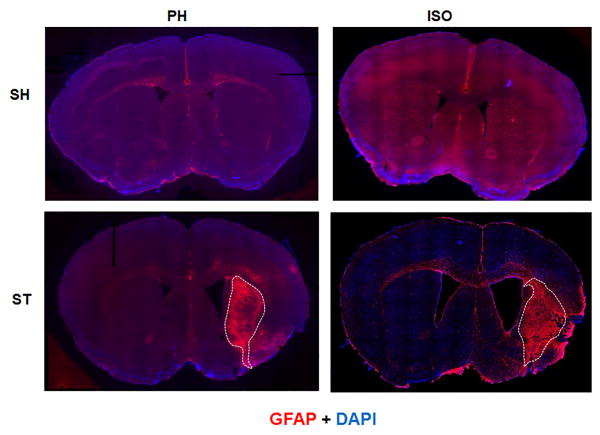

3.7 Pair housing reduces glial activation and modulates Arginase-1 expression

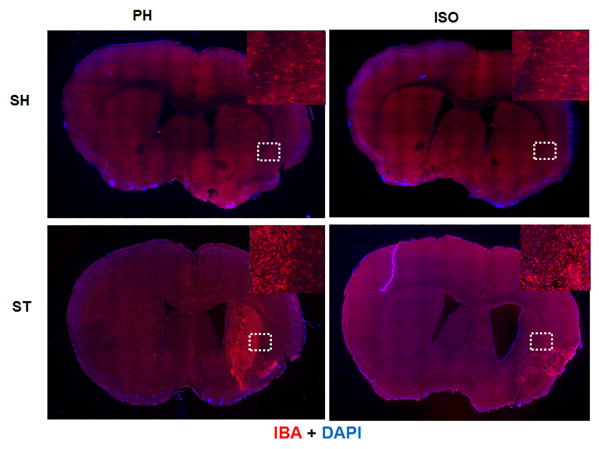

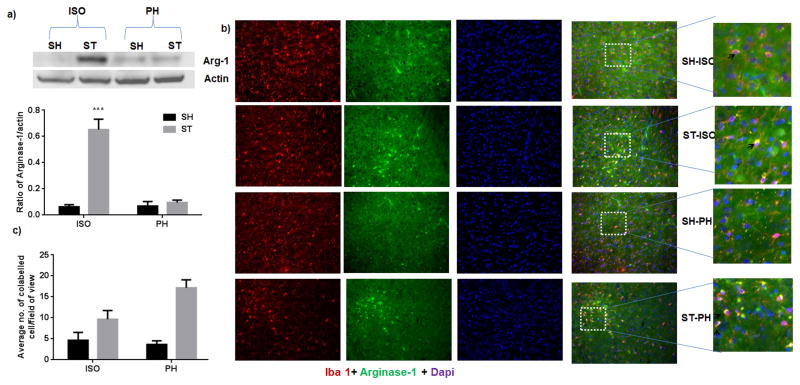

In order to elucidate the mechanism underlying the apparent beneficial effects of pair housing, we examined the expression of GFAP and IBA-1, markers of reactive astrogliosis and microgliosis respectively, 6 weeks after stroke. We found that the glial scar (dense GFAP expression) was confined to the striatal region in the ST-PH group, whereas the glial scar extended into both striatal and cortical regions in ST-ISO mice (Fig 9). Similarly, the region of intense IBA-1+ expression by microglial/macrophages was also confined to the striatal region in stroke PH group (Fig. 10). Interestingly, the overall expression of Arginase-1 in whole brain lysate was significantly higher (F 1, 14 = 18.05, P = 0.0008) in the ST-ISO group compared to other groups (Fig 11a). However, when specific cell types were examined, an increase in the number of microglia/macrophages that co-labelled with IBA-1 and Arginase-1, was seen in the peri-infarct region of ST-PH mice (Fig. 11b & 11c).

Fig. 9.

Representative mosaic image of mouse brain section captured at 10x magnification for GFAP expression at 6 weeks after MCAO. Double immunostaioning of GFAP (red) and DAPI (blue) showed that GFAP+ cell were activated at the site of infraction in both stroke groups. Dotted lines show that dense GFAP expression (Glial scar) was confined to the striatal region in ST-PH mice while in strokes-ISO mice it was widely expressed in both striatum and cortex (n=4 per group). SI sham mice also showed higher baseline activity of GFAP.

Fig. 10.

Representative mosaic image of mouse brain section (adjacent to the section used for GFAP expression) captured at 10x magnification for Iba-1 expression. Brain section was taken after 6 weeks of stroke. Double immunostaioning of Iba-1 (red) and DAPI (blue) showed that Iba-1+ cell were dense and appeared “activated” at the site of infraction in both stroke groups (n=4 per group). Unlike GFAP, Iba-1 expression was not widespread in ipsilateral hemisphere in the ST-ISO group, and was confined to damaged areas as shown by dotted lines.

Fig 11.

a) Arginase-1 expression after stroke a) Overall expression of arginase-1 was significantly increased (F 1, 14 = 18.05, P = 0.0008)) in ST-ISO group as compared to other groups in the lysate of ipsilateral brain (n=5 in each group). b) Immunofluorescent staining for Iba1 (red), arginase-1 (green) and DAPI (blue) in the brains of young mice 6 weeks after MCAO (representative of 4 animals). Increased expression of arginase-1 was found in both ST- ISO and ST- PH group as compared to SH-ISO and SH-PH. c) However, higher number of both Iba+ and arginase-1+ cells ( ) were present in PH house stroke (ST-PH) mice as compared to other groups of mice (*P<0.05 and **P<0.001 vs ST-PH).

4. Discussion

Stroke survivors, often because of their limited functional mobility, are at risk for social isolation. Social isolation and reduced social support are linked to an increased risk of depression and poorer stroke recovery [39]. The negative effects of SI on stroke have been well documented in clinical populations [40, 41]. SI prior to stroke enhances tissue injury, delays recovery and increases mortality [42, 43]. Experimental studies have shown similar findings. The detrimental effects of SI are mediated in part by enhanced NF-KB activation, IL-6 production, and decreased oxytocin [20, 44, 45]. The majority of pre-clinical studies examined pre-stroke isolation which may be less translationally relevant as patients are often not identified as isolated until after they come to medical attention for their stroke. A recent study from our lab has shown that post-stroke pair housing increases BDNF levels and improves behavioural recovery [27]. However, detailed evaluation of sociability and depressive behaviour was not evaluated. Our work here suggests that a progressive deficit in sociability occurs in isolated animals, with increasing social withdrawal over time, further worsening the opportunity for functional recovery.

Mice exhibit a rich repertoire of social behaviours. These behaviours are important for forming bonds, foraging, defending territories, avoiding predators, and reproducing successfully [46]. Mice have a natural tendency to approach and investigate unfamiliar conspecifics [30]. Stroke impacts this normal affiliative behaviour and may alter the natural tendency to approach unfamiliar conspecifics [7, 47]. We addressed the need for a “sociability” behavioural test after stroke, as data is currently lacking for mice, by modifying a pre-existing three-chamber sociability task [30] to measure post-stroke sociability/affiliative behaviour over time.

In this study, we found that ST-PH mice maintain social interaction and sociability throughout the experiment unlike ST ISO mice. Most interestingly, ST ISO mice demonstrated a progressive decline in sociability that started at day 7 and progressed over the 4 weeks post-stroke, leading to the lowest interaction a month after injury. In most behavioural paradigms, especially when assessing motor deficits, stroke recovery begins within days after stroke [48], even after large insults. We have previously found persistent deficits in tasks of sensory-motor integration (i.e., on the “corner” test) for 6 weeks after injury in prior studies [49] but this is the first description of a behaviour that progressively worsens over time despite recovery in other tasks. Post-stroke isolation was therefore associated with alterations in at least 3 major behaviours associated with a depression phenotype: sociability, avolition and anhedonia. Improvements in sociability were seen with pair-housing. This suggests that there is a great deal of opportunity in the sub-acute post-stroke period to enhance neuroplasticity and repair by environmental manipulations. Environmental enrichment refers to housing conditions that facilitate enhanced sensory, social, cognitive stimulation, and motor activity [50], simple changes in the post-stroke environment led to enhanced sociability and interaction which improved outcomes. Moreover, these non-invasive strategies can be employed to enhance recovery in stroke patients. This is the first application of the three-chamber sociability task to study post-stroke affiliative behaviour in transient focal cerebral ischemia. Our findings demonstrate this paradigm's applicability for quantifying sociability after stroke.

In addition to the effect of isolation or pair housing, the location of a lesion has also been shown to contribute to social behaviours, with injury to the frontal lobes and right hemisphere in particular being associated with behavioural deficits [51]. The observed impairment in sociability may be secondary to the severe tissue loss of prefrontal cortex, temporo-parietal junction, cingulate cortex, insula, and amygdala, as well as their connecting pathways [52, 53] observed in our post-stroke SI cohorts. Moreover, the delay in cortical reorganization as suggested in previous studies may contribute to impairment and adoption of compensatory behaviour, which in turn can lead to a delay in the recovery of brain function [54, 55]. A recent study suggests that social interaction in mice requires the coordinated activity of oxytocin and 5-HT in the nucleus accumbens core (NAC) and demonstrated that oxytocin acts as a social reinforcement signal and induces synaptic plasticity which further requires activation of nucleus accumbens 5-HT1B receptors [56]. Alterations in sociability also led to reduced myelin thickness in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) in a model of juvenile isolation. The reduced thickness of myelin reduces the conduction velocity of myelinated mPFC axons, leading to abnormal information processing, which in turn may contribute to aberrant social behaviours and working memory [57]. Loss of myelin also contributes to delayed behavioural recovery in mice after chronic social isolation in a test of score approach-avoidance behaviours toward an unfamiliar social target [58]. However such robust changes in overall expression of myelin basic protein (Supp Fig 6) were not seen in this study except in the ST ISO group. This could have been due to the higher degree of tissue loss in isolated mice.

Depression is one of the most prominent psychological changes associated with stroke [59]. The mechanisms underlying post stroke depression are not well understood and research on this topic has been hindered by a lack of reliable chronic animal models of depression after stroke. The data from the current study and also from previous work [15] suggest that it is possible to induce and study anhedonia as an index of post-stroke depressive-like behaviour in mice. We observed that sucrose consumption significantly decreased for all groups following surgery (Supp. Fig 4). Furthermore, ISO mice showed a significantly lower consumption of sucrose than PH mice. This anhedonic characteristic of the depressive phenotype has also been reported in other models of social isolation [60]. Interestingly, the healthy non-stroke partners of stroke mice also showed a depressive phenotype as assessed by immobility in the TST. This may be similar to what is seen in clinical populations, where caregivers that spend the majority of their time with dependent patients at home also are at high risk for depression [61].

Similar to what was seen in the SCT and TST, PH improves affiliative behaviour in the three-chamber sociability test. Taken together this data suggests that the reduced sociability phenotype is an additive effect of isolation and stroke. Although, it can be argued that the increased behavioural deficits seen in post stroke SI mice are simply an epiphenomenon of changes in infarct size, however this is unlikely based on the progressive nature of the sociability deficit in this group [62]. Therefore, our data showed that stroke and social isolation independently and synergistically contributed to a depression phenotype.

Stroke is also associated with dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and neuroinflammation. Both of these physiological alterations have been associated with depressive symptoms in non-stroke populations [63-65]. The association between depression, depressive symptoms and elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-6, and C-reactive protein (CRP), has been well described in both clinical and preclinical models of psychosocial stress [19, 66]. We found no significant changes in circulating IL-6 levels 6 weeks after stroke in PH versus SI mice. However, SI mice from both sham and stroke groups had a significant increase in serum IL-6 levels compared to PH mice. This suggests that chronic isolation leads to a baseline “pro-inflammatory state” which may contribute to enhanced damage when an injury does occur. This is consistent with previous reports where isolation itself leads to increases in serum IL-6 levels in men [66] and may be part of the mechanism by which pre-stroke social isolation enhances disease. In contrast to our results, several previous studies [20] have found increased levels of serum IL-6 in isolated mice. However the levels were obtained at short time poits after injury (12-72 hours after stroke). It is likely that these elevations in IL-6 are transient and seen only in the acute phase. It appears that IL-6 levels retuen to baseline as stroke-induced inflammation wanes, similar to what we observed with stroke-induced changes in splenic volume [67].

Microglia/macrophages represent the first line of defense against CNS and ischemic brain injury[68, 69]). The resident microglia and peripheral macrophages are rapidly mobilized to the site of injury where they initiate dual but opposing responses. Others have found that there is an intial anti-inflammatory M2 response during early reperfusion, but the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype rapidly emerges and dominates the myeloid response, but these responses were only evaluated for 2 weeks after injury [69]. In this study we examined arginase-1, a marker for M2 activation 6 weeks after stroke. Unexpectedly, total brain arginase-1 expression was higher in isolated stroke mice. This finding however is consistent with a recent study reporting increased expression of arginase-1 after stroke, postulated to be be involved in secondary expansion of ischemic damage by increasing reactive oxygen species [70]. [71]. The higher level of arginase-1 in SI mice was surprising as arginase-1 is a well characterized marker of the M2 myeloid phenotype, considered to be reparative subset of myeloid cells [72]. To further explore this finding, we examined the expression of arginase-1 specifically in Iba-1+ cells. Higher numbers of arginase-1 and Iba-1+ co-expressing cells were seen in post-stroke PH mice comapred to SI mice and the intensity of arginase-1 expression was higher in these cells. This suggests that the M2 phenotype in microglia/macrophase dominates during the recovery phase in ST-PH as compared to ST-ISO mice. The paradoxical findings in the expression of arginase-1 in our western blot, which examined whole cell lysates (which includes all cell types) versus our findings from subsequent IHC experiments suggest that arginase-1 might have cell specific effects [71, 73, 74].

Overall, our findings suggest that 1) PH hastens recovery and reduces histological damage after stroke. 2) SI and stroke can either independently or additively alter at least 3 major aspects of the depressive phenotype: sociability, avolition and anhedonia. 3) Progressive withdrawal in isolated animals may further hinder recovery. 4) The three chamber socialization task can be an appropriate model to study long term behaviour changes. 5) Finally, the protective effects of PH may be mediated by M2 activation in microglia/macrophages. These studies may help translate targeted social interventions to reduces PSD and enhance recovery after stroke.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Abnormal social behaviour is seen after stroke.

Pair housing after stroke enhances recovery from stroke-induced behavioural deficits.

Animals isolated after stroke had a progressive deficit in sociability that worsened over time

The protective effects of pair housing may be mediated by M2 activation of microglia/macrophages.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by R01 NSO77769 and NS055215 to L.D.M.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Glass TA, Matchar DB, Belyea M, Feussner JR. Impact of social support on outcome in first stroke. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 1993;24:64–70. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glass TA, Maddox GL. The quality and quantity of social support: stroke recovery as psycho- social transition. Social science & medicine. 1992;34:1249–61. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90317-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ditzen B, Schmidt S, Strauss B, Nater UM, Ehlert U, Heinrichs M. Adult attachment and social support interact to reduce psychological but not cortisol responses to stress. Journal of psychosomatic research. 2008;64:479–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steptoe A, Shankar A, Demakakos P, Wardle J. Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:5797–801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219686110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hinojosa R, Haun J, Hinojosa MS, Rittman M. Social isolation poststroke: relationship between race/ethnicity, depression, and functional independence. Topics in stroke rehabilitation. 2011;18:79–86. doi: 10.1310/tsr1801-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. A Short Scale for Measuring Loneliness in Large Surveys: Results From Two Population-Based Studies. Research on aging. 2004;26:655–72. doi: 10.1177/0164027504268574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Craft TK, Glasper ER, McCullough L, Zhang N, Sugo N, Otsuka T, et al. Social interaction improves experimental stroke outcome. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2005;36:2006–11. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000177538.17687.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kouwenhoven SE, Gay CL, Bakken LN, Lerdal A. Depressive symptoms in acute stroke: A cross-sectional study of their association with sociodemographics and clinical factors. Neuropsychological rehabilitation. 2013 doi: 10.1080/09602011.2013.801778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson CS, Mahon A, McLeod W. Nutritional, functional and psychosocial correlates of disability among older adults. The journal of nutrition, health & aging. 2006;10:45–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jean FA, Swendsen JD, Sibon I, Feher K, Husky M. Daily life behaviours and depression risk following stroke: a preliminary study using ecological momentary assessment. Journal of geriatric psychiatry and neurology. 2013;26:138–43. doi: 10.1177/0891988713484193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kauhanen M, Korpelainen JT, Hiltunen P, Brusin E, Mononen H, Maatta R, et al. Poststroke depression correlates with cognitive impairment and neurological deficits. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 1999;30:1875–80. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.9.1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langer SL, Pettigrew LC, Wilson JF, Blonder LX. Personality and social competency following unilateral stroke. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society : JINS. 1998;4:447–55. doi: 10.1017/s1355617798455048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neau JP, Ingrand P, Mouille-Brachet C, Rosier MP, Couderq C, Alvarez A, et al. Functional recovery and social outcome after cerebral infarction in young adults. Cerebrovascular diseases. 1998;8:296–302. doi: 10.1159/000015869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piamarta F, Iurlaro S, Isella V, Atzeni L, Grimaldi M, Russo A, et al. Unconventional affective symptoms and executive functions after stroke in the elderly. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics Supplement. 2004:315–23. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2004.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Craft TK, DeVries AC. Role of IL-1 in poststroke depressive-like behaviour in mice. Biological psychiatry. 2006;60:812–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diamond PT, Holroyd S, Macciocchi SN, Felsenthal G. Prevalence of depression and outcome on the geriatric rehabilitation unit. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation / Association of Academic Physiatrists. 1995;74:214–7. doi: 10.1097/00002060-199505000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schubert DS, Taylor C, Lee S, Mentari A, Tamaklo W. Detection of depression in the stroke patient. Psychosomatics. 1992;33:290–4. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(92)71967-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freret T, Schumann-Bard P, Boulouard M, Bouet V. On the importance of long-term functional assessment after stroke to improve translation from bench to bedside. Experimental & translational stroke medicine. 2011;3:6. doi: 10.1186/2040-7378-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karelina K, Norman GJ, Zhang N, Morris JS, Peng H, DeVries AC. Social isolation alters neuroinflammatory response to stroke. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:5895–900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810737106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Venna VR, Weston G, Benashski SE, Tarabishy S, Liu F, Li J, et al. NF-kappaB contributes to the detrimental effects of social isolation after experimental stroke. Acta neuropathologica. 2012;124:425–38. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-0990-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maas MB, Furie KL. Molecular biomarkers in stroke diagnosis and prognosis. Biomarkers in medicine. 2009;3:363–83. doi: 10.2217/bmm.09.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schilling M, Besselmann M, Muller M, Strecker JK, Ringelstein EB, Kiefer R. Predominant phagocytic activity of resident microglia over hematogenous macrophages following transient focal cerebral ischemia: an investigation using green fluorescent protein transgenic bone marrow chimeric mice. Experimental neurology. 2005;196:290–7. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kigerl KA, Gensel JC, Ankeny DP, Alexander JK, Donnelly DJ, Popovich PG. Identification of two distinct macrophage subsets with divergent effects causing either neurotoxicity or regeneration in the injured mouse spinal cord. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2009;29:13435–44. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3257-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perry VH, Nicoll JA, Holmes C. Microglia in neurodegenerative disease. Nature reviews Neurology. 2010;6:193–201. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chiba T, Umegaki K. Pivotal roles of monocytes/macrophages in stroke. Mediators of inflammation. 2013;2013:759103. doi: 10.1155/2013/759103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hesse M, Modolell M, La Flamme AC, Schito M, Fuentes JM, Cheever AW, et al. Differential regulation of nitric oxide synthase-2 and arginase-1 by type 1/type 2 cytokines in vivo: granulomatous pathology is shaped by the pattern of L-arginine metabolism. Journal of immunology. 2001;167:6533–44. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Keefe LM, Doran SJ, Mwilambwe-Tshilobo L, Conti LH, Venna VR, McCullough LD. Social isolation after stroke leads to depressive-like behaviour and decreased BDNF levels in mice. Behavioural brain research. 2014;260:162–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.10.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kilic E, Hermann DM, Kugler S, Kilic U, Holzmuller H, Schmeer C, et al. Adenovirus-mediated Bcl-X(L) expression using a neuron-specific synapsin-1 promoter protects against disseminated neuronal injury and brain infarction following focal cerebral ischemia in mice. Neurobiology of disease. 2002;11:275–84. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li J, Zeng Z, Viollet B, Ronnett GV, McCullough LD. Neuroprotective effects of adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase inhibition and gene deletion in stroke. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2007;38:2992–9. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.490904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moy SS, Nadler JJ, Perez A, Barbaro RP, Johns JM, Magnuson TR, et al. Sociability and preference for social novelty in five inbred strains: an approach to assess autistic-like behaviour in mice. Genes, brain, and behaviour. 2004;3:287–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-1848.2004.00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaidanovich-Beilin O, Lipina T, Vukobradovic I, Roder J, Woodgett JR. Assessment of social interaction behaviours. Journal of visualized experiments JoVE. 2011 doi: 10.3791/2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chatterjee M, Jaiswal M, Palit G. Comparative evaluation of forced swim test and tail suspension test as models of negative symptom of schizophrenia in rodents. ISRN psychiatry. 2012;2012:595141. doi: 10.5402/2012/595141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Chiara V, Errico F, Musella A, Rossi S, Mataluni G, Sacchetti L, et al. Voluntary exercise and sucrose consumption enhance cannabinoid CB1 receptor sensitivity in the striatum. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:374–87. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cryan JF, Mombereau C, Vassout A. The tail suspension test as a model for assessing antidepressant activity: review of pharmacological and genetic studies in mice. Neuroscience and biobehavioural reviews. 2005;29:571–625. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li J, Henman MC, Doyle KM, Strbian D, Kirby BP, Tatlisumak T, et al. The pre-ischaemic neuroprotective effect of a novel polyamine antagonist, N1-dansyl-spermine in a permanent focal cerebral ischaemia model in mice. Brain research. 2004;1029:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li J, McCullough LD. Sex differences in minocycline-induced neuroprotection after experimental stroke. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2009;29:670–4. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu F, Benashski SE, Persky R, Xu Y, Li J, McCullough LD. Age-related changes in AMP-activated protein kinase after stroke. Age. 2012;34:157–68. doi: 10.1007/s11357-011-9214-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Whiteley W, Jackson C, Lewis S, Lowe G, Rumley A, Sandercock P, et al. Inflammatory markers and poor outcome after stroke: a prospective cohort study and systematic review of interleukin-6. PLoS medicine. 2009;6:e1000145. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morris PL, Robinson RG, Raphael B. Prevalence and course of depressive disorders in hospitalized stroke patients. International journal of psychiatry in medicine. 1990;20:349–64. doi: 10.2190/N8VU-6LWU-FLJN-XQKV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith TW, Ruiz JM. Psychosocial influences on the development and course of coronary heart disease: current status and implications for research and practice. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2002;70:548–68. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.3.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mookadam F, Arthur HM. Social support and its relationship to morbidity and mortality after acute myocardial infarction: systematic overview. Archives of internal medicine. 2004;164:1514–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.14.1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cornwell EY, Waite LJ. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. Journal of health and social behaviour. 2009;50:31–48. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang YC, McClintock MK, Kozloski M, Li T. Social isolation and adult mortality: the role of chronic inflammation and sex differences. Journal of health and social behaviour. 2013;54:183–203. doi: 10.1177/0022146513485244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nicholson NR. A review of social isolation: an important but underassessed condition in older adults. The journal of primary prevention. 2012;33:137–52. doi: 10.1007/s10935-012-0271-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zlatkovic J, Filipovic D. Chronic social isolation induces NF-kappaB activation and upregulation of iNOS protein expression in rat prefrontal cortex. Neurochemistry international. 2013;63:172–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang M, Silverman JL, Crawley JN. Automated three-chambered social approach task for mice. Current protocols in neuroscience / editorial board, Jacqueline N Crawley [et al] 2011 doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0826s56. Chapter 8:Unit 8 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wills GD, Wesley AL, Moore FR, Sisemore DA. Social interactions among rodent conspecifics: a review of experimental paradigms. Neuroscience and biobehavioural reviews. 1983;7:315–23. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(83)90035-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Manwani B, Liu F, Xu Y, Persky R, Li J, McCullough LD. Functional recovery in aging mice after experimental stroke. Brain, behaviour, and immunity. 2011;25:1689–700. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li X, Blizzard KK, Zeng Z, DeVries AC, Hurn PD, McCullough LD. Chronic behavioural testing after focal ischemia in the mouse: functional recovery and the effects of gender. Experimental neurology. 2004;187:94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Faralli A, Bigoni M, Mauro A, Rossi F, Carulli D. Noninvasive strategies to promote functional recovery after stroke. Neural plasticity. 2013;2013:854597. doi: 10.1155/2013/854597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Greenham M, Spencer-Smith MM, Anderson PJ, Coleman L, Anderson VA. Social functioning in children with brain insult. Frontiers in human neuroscience. 2010;4:22. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2010.00022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Adolphs R. The neurobiology of social cognition. Current opinion in neurobiology. 2001;11:231–9. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00202-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spikman JM, Timmerman ME, Milders MV, Veenstra WS, van der Naalt J. Social cognition impairments in relation to general cognitive deficits, injury severity, and prefrontal lesions in traumatic brain injury patients. Journal of neurotrauma. 2012;29:101–11. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miyazaki T, Takase K, Nakajima W, Tada H, Ohya D, Sano A, et al. Disrupted cortical function underlies behaviour dysfunction due to social isolation. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2012;122:2690–701. doi: 10.1172/JCI63060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zeiler SR, Gibson EM, Hoesch RE, Li MY, Worley PF, O'Brien RJ, et al. Medial premotor cortex shows a reduction in inhibitory markers and mediates recovery in a mouse model of focal stroke. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2013;44:483–9. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.676940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dolen G, Darvishzadeh A, Huang KW, Malenka RC. Social reward requires coordinated activity of nucleus accumbens oxytocin and serotonin. Nature. 2013;501:179–84. doi: 10.1038/nature12518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Makinodan M, Rosen KM, Ito S, Corfas G. A critical period for social experience-dependent oligodendrocyte maturation and myelination. Science. 2012;337:1357–60. doi: 10.1126/science.1220845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu J, Dietz K, DeLoyht JM, Pedre X, Kelkar D, Kaur J, et al. Impaired adult myelination in the prefrontal cortex of socially isolated mice. Nature neuroscience. 2012;15:1621–3. doi: 10.1038/nn.3263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Whyte EM, Mulsant BH. Post stroke depression: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and biological treatment. Biological psychiatry. 2002;52:253–64. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01424-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Grippo AJ, Gerena D, Huang J, Kumar N, Shah M, Ughreja R, et al. Social isolation induces behavioural and neuroendocrine disturbances relevant to depression in female and male prairie voles. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2007;32:966–80. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pagani M, Giovannetti AM, Covelli V, Sattin D, Raggi A, Leonardi M. Physical and Mental Health Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms in Caregivers of Patients in Vegetative State and Minimally Conscious State. Clinical psychology & psychotherapy. 2013 doi: 10.1002/cpp.1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu F, Schafer DP, McCullough LD. TTC, fluoro-Jade B and NeuN staining confirm evolving phases of infarction induced by middle cerebral artery occlusion. Journal of neuroscience methods. 2009;179:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bogousslavsky J. William Feinberg lecture 2002: emotions, mood, and behaviour after stroke. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2003;34:1046–50. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000061887.33505.B9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pollak Y, Yirmiya R. Cytokine-induced changes in mood and behaviour: implications for ‘depression due to a general medical condition’, immunotherapy and antidepressive treatment. The international journal of neuropsychopharmacology / official scientific journal of the Collegium Internationale Neuropsychopharmacologicum. 2002;5:389–99. doi: 10.1017/S1461145702003152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wright CE, Strike PC, Brydon L, Steptoe A. Acute inflammation and negative mood: mediation by cytokine activation. Brain, behaviour, and immunity. 2005;19:345–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hafner S, Emeny RT, Lacruz ME, Baumert J, Herder C, Koenig W, et al. Association between social isolation and inflammatory markers in depressed and non-depressed individuals: results from the MONICA/KORA study. Brain, behaviour, and immunity. 2011;25:1701–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ceulemans AG, Zgavc T, Kooijman R, Hachimi-Idrissi S, Sarre S, Michotte Y. The dual role of the neuroinflammatory response after ischemic stroke: modulatory effects of hypothermia. Journal of neuroinflammation. 2010;7:74. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-7-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kreutzberg GW. Microglia: a sensor for pathological events in the CNS. Trends in neurosciences. 1996;19:312–8. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(96)10049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hu X, Li P, Guo Y, Wang H, Leak RK, Chen S, et al. Microglia/macrophage polarization dynamics reveal novel mechanism of injury expansion after focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2012;43:3063–70. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.659656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pernow J, Jung C. Arginase as a potential target in the treatment of cardiovascular disease: reversal of arginine steal? Cardiovascular research. 2013;98:334–43. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Quirie A, Demougeot C, Bertrand N, Mossiat C, Garnier P, Marie C, et al. Effect of stroke on arginase expression and localization in the rat brain. The European journal of neuroscience. 2013;37:1193–202. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gordon S, Taylor PR. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nature reviews Immunology. 2005;5:953–64. doi: 10.1038/nri1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Estevez AG, Sahawneh MA, Lange PS, Bae N, Egea M, Ratan RR. Arginase 1 regulation of nitric oxide production is key to survival of trophic factor-deprived motor neurons. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2006;26:8512–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0728-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Deng K, He H, Qiu J, Lorber B, Bryson JB, Filbin MT. Increased synthesis of spermidine as a result of upregulation of arginase I promotes axonal regeneration in culture and in vivo. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2009;29:9545–52. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1175-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.