Abstract

Background

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends against routine screening for colorectal cancer (CRC) in adequately screened elderly aged over 75. The USPSTF did not address the appropriateness of screening in elderly aged over 75 without prior screening.

Objective

To determine up to what age CRC screening should be considered in unscreened elderly with no, moderate, and severe comorbidity and to determine which test is indicated at what age.

Design

Microsimulation modeling study.

Data Sources

Derived from the literature.

Target Populations

Unscreened elderly aged 76, 77, (...), and 90 with no, moderate, and severe comorbidity.

Time Horizon

Lifetime.

Perspective

Societal.

Interventions

Once-only colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, and fecal immunochemical test (FIT) screening.

Outcome Measures

CRC cases prevented, CRC deaths prevented, life-years gained, quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) gained, costs, and costs per QALY gained.

Results of Base-Case Analysis

In unscreened elderly with no, moderate, and severe comorbidity, CRC screening was cost-effective up to age 86, 83, and 80, respectively. In unscreened elderly with no comorbidity, colonoscopy screening was most effective and still cost-effective up to age 83; sigmoidoscopy screening was indicated at age 84; and FIT screening was indicated at ages 85 and 86. In unscreened elderly with moderate (severe) comorbidity, colonoscopy screening was indicated up to age 80 (77); sigmoidoscopy screening was indicated at age 81 (78); and FIT screening was indicated at ages 82 and 83 (79 and 80).

Results of Sensitivity Analyses

Results were most sensitive to lowering the threshold for the willingness-to-pay per QALY gained from $100,000 to $50,000.

Limitation

We only considered cohorts at average risk for CRC.

Conclusions

In unscreened elderly with no, moderate, and severe comorbidity, whose physical condition allows a colonoscopy, CRC screening should be considered well beyond age 75: up to age 86, 83, and 80, respectively. At most ages, colonoscopy screening is indicated.

Primary Funding Source

The U.S. National Cancer Institute.

INTRODUCTION

In its most recent recommendation statement on colorectal cancer (CRC) screening, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening using fecal occult blood testing, sigmoidoscopy, or colonoscopy, starting at age 50 and continuing up to age 75 (1). The USPSTF recommends against routine screening in elderly aged over 75 with an adequate screening history (1). This latter recommendation is warranted by an analysis showing that the benefits of continuing screening from age 50 up to age 85 instead of 75 do not justify the additional colonoscopies required (2). Although the USPSTF did not address the appropriateness of screening in inadequately screened elderly, this recommendation has led many in the medical community to believe that no one aged over 75 should be screened for CRC (3, 4). However, as unscreened elderly are at higher risk for CRC than adequately screened elderly, screening them is likely to be effective and cost-effective up to a more advanced age. If so, the lack of more specific recommendations on the age to stop screening might result in an unfounded denial of access to screening in elderly aged over 75 who were never screened for CRC: a group representing 23% of all U.S. elderly aged over 75 (5).

On the other hand, many elderly continue to be screened up to their late 80's or early 90's (6). However, at these ages screening is not likely to be cost-effective, even in those without prior screening: First of all, the high risk of death from competing disease at advanced age tends to offset the benefits of screening (7, 8). Secondly, the risks for screening induced harms (i.e. colonoscopy-related complications and over-diagnosis and over-treatment of CRC) increase with increasing age (9).

The objective of this study was to determine up to what age CRC screening should be considered in elderly without prior screening and to determine which screening test - a colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, or fecal immunochemical test (FIT) – is indicated at what age. As the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of screening depend heavily on an individual's life-expectancy, we performed separate analyses for elderly with no, moderate, and severe comorbidity.

METHODS

To quantify the effectiveness and costs of screening we used Microsimulation Screening Analysis-Colon (MISCAN-Colon).

MISCAN-Colon

MISCAN-Colon is a well-established microsimulation model for CRC developed at the Department of Public Health of the Erasmus University Medical Center (Rotterdam, the Netherlands). The model's structure, underlying assumptions, and calibration are described in the Model Appendix. In brief, MISCAN-Colon simulates the life histories of a large population of persons from birth to death. As each simulated person ages, one or more adenomas may develop. These adenomas can progress from small (≤5mm), to medium (6-9mm), to large size (≥10mm). Some adenomas can develop into preclinical cancer, which may progress through stages I to IV. During each stage CRC may be diagnosed because of symptoms. Survival after clinical diagnosis is determined by the stage at diagnosis, the localization of the cancer, and the person's age (10).

Screening will alter some of the simulated life histories: Some cancers will be prevented by the detection and removal of adenomas; other cancers will be detected in an earlier stage with a more favorable survival. However, screening can also result in serious complications and over-diagnosis and over-treatment of CRC (i.e. the detection and treatment of cancers that would not have been diagnosed without screening). By comparing all life histories with screening with the corresponding life histories without screening, MISCAN-Colon quantifies the effectiveness of screening, as well as the associated costs.

MISCAN-Colon was calibrated to the age-, stage-, and localization-specific incidence of CRC as observed in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program before the introduction of screening (i.e. between 1975 and 1979) and the age-specific prevalence and the multiplicity distribution of adenomas as observed in autopsy studies (11-21). The preclinical duration of CRC and the adenoma dwell-time were calibrated to the rates of interval and surveillance detected cancers observed in randomized controlled trials evaluating screening using guaiac fecal occult blood tests and a once-only sigmoidoscopy (22-26). More detailed information about MISCAN-Colon is available from the authors upon request.

Model Inputs

Populations Simulated

For each age between 76 and 90 we simulated a cohort of 10 million elderly without prior screening with no, moderate, and severe comorbidity: a total of 45 cohorts. Compared with cohorts of adequately screened elderly, the risk for CRC in these cohorts was substantially higher: whereas CRC and adenomas were prevalent in 0.3% and 14.1% of all simulated 80-year-olds with negative screening colonoscopies at ages 50, 60, and 70, these lesions were prevalent in 2.6% and 44.9% of all simulated 80-year-olds without prior screening.

To simulate elderly with no, moderate, and severe comorbidity, we used comorbidity status specific life-tables (27). Individuals are classified as having moderate comorbidity if diagnosed with an ulcer, rheumatologic disease, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, paralysis, or cerebrovascular disease and in case of a history of acute myocardial infarction; as having severe comorbidity if diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, moderate or severe liver disease, chronic renal failure, dementia, cirrhosis and chronic hepatitis, or AIDS; and as having no comorbidity if none of these conditions is present.

Screening Strategies

Within each cohort we simulated once-only colonoscopy, once-only sigmoidoscopy, and once-only FIT screening. For each screening test, test characteristics and complication rates are given in Appendix Table 1. Individuals with an adenoma or CRC detected during sigmoidoscopy or with a positive FIT were referred for a diagnostic colonoscopy. Individuals with adenomas detected and removed during a screening or diagnostic colonoscopy were assumed to undergo colonoscopy surveillance according to the current guidelines (28). We assumed that surveillance continued until the diagnosis of CRC or death. Adherence to screening and diagnostic and surveillance colonoscopies was assumed to be 100%.

We restricted ourselves to once-only colonoscopy and once-only sigmoidoscopy screening, as, at old age, performing more screening colonoscopies or sigmoidoscopies is unlikely to be cost-effective. We explored the impact of FIT screening during two consecutive years in a sensitivity analysis.

Utility Losses Associated with CRC Screening

We assumed a utility loss (i.e. a loss of quality of life) equivalent to two full days of life per colonoscopy (0.0055 QALYs), one day of life per sigmoidoscopy (0.0027 QALYs), and two weeks of life per complication (0.0384 QALYs) (Table 1). We also assigned a utility loss to each LY with CRC care (30).

Table 1.

Model Inputs: Utility Losses and Costs Associated with Colorectal Cancer Screening.

| UTILITY LOSS (QALYs)* | ||||

| Per FIT | 0 | |||

| Per sigmoidoscopy | ||||

| without biopsy | 0.0027 | |||

| with biopsy | 0.0027 | |||

| Per colonoscopy | ||||

| without polypectomy/ biopsy | 0.0055 | |||

| with polypectomy/ biopsy | 0.0055 | |||

| Per complication of colonoscopy | 0.038 | |||

| Per LY with CRC care†‡ | Initial care | Continuing care | Terminal care Death CRC | Terminal care Death other cause |

| Stage I CRC | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.70 | 0.05 |

| Stage II CRC | 0.18 | 0.05 | 0.70 | 0.05 |

| Stage III CRC | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.70 | 0.24 |

| Stage IV CRC | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.70 |

|

COSTS (2013 US$)§ | ||||

| Per FIT | 42 | |||

| Per sigmoidoscopy | ||||

| without biopsy | 299 | |||

| with biopsy | 557 | |||

| Per colonoscopy | ||||

| without polypectomy/ biopsy | 887 | |||

| with polypectomy/ biopsy | 1,096 | |||

| Per complication of colonoscopy | 6,045 | |||

| Per LY with CRC care† | Initial care | Continuing care | Terminal care Death CRC | Terminal care Death other cause |

| Stage I CRC | 36,683 | 3,050 | 63,809 | 19,176 |

| Stage II CRC | 49,234 | 2,870 | 63,555 | 17,279 |

| Stage III CRC | 59,759 | 4,021 | 67,041 | 21,457 |

| Stage IV CRC | 77,790 | 12,178 | 88,368 | 49,866 |

QALY = quality-adjusted life-year; FIT = fecal immunochemical test; LY = life-year; CRC = colorectal cancer

The loss of quality of life associated with a particular event.

Care for CRC was divided in three clinically relevant phases: the initial, continuing, and terminal care phase. The initial care phase was defined as the first 12 months after diagnosis; the terminal care phase was defined as the final 12 months of life; the continuing care phase was defined as all months in between. In the terminal care phase, we distinguished between CRC patients dying from CRC and CRC patients dying from another cause. For patients surviving less than 24 months, the final 12 months were allocated to the terminal care phase and the remaining months were allocated to the initial care phase.

Utility losses for LYs with initial care were derived from a study by Ness and colleagues (30). For LYs with continuing care for stage I and II CRC, we assumed a utility loss of 0.05 QALYs; for LYs with continuing care for stage III and IV CRC, we assumed the corresponding utility losses for LYs with initial care. For LYs with terminal care for CRC, we assumed the utility loss for LYs with initial care for stage IV CRC. For LYs with terminal care for another cause, we assumed the corresponding utility losses for LYs with continuing care.

Costs include copayments and patient time costs (i.e. the opportunity costs of spending time on screening or being treated for a complication or CRC), but do not include travel costs, costs of lost productivity, and unrelated health care and non-health care costs in added years of life. We assumed that the value of patient time was equal to the median wage rate in 2012: $16.71 per hour (29). We assumed that FITs, sigmoidoscopies, colonoscopies, and complications used up 1, 4, 8 and 16 hours of patient time, respectively. Patient time costs were already included in the estimates for the costs of LYs with CRC care obtained from a study by Yabroff and colleagues (31).

Assigning utility losses to LYs with CRC care works two ways: On the one hand, screening prevents cancers by the detection and removal of adenomas, thereby reducing LYs with CRC care, and hence, resulting in a gain of quality of life. On the other hand, screening results in over-diagnosis and over-treatment of cancers, resulting in LYs with CRC care in individuals who would never have been diagnosed with CRC without screening, and hence, a loss of quality of life. The net impact on quality of life depends on the balance between cancers prevented and cancers over-diagnosed and can be either positive or negative.

Costs Associated with CRC Screening

The cost-effectiveness analyses were conducted from a societal perspective. The costs of colonoscopies, sigmoidoscopies, and FITs were based on 2007 Medicare payment rates and copayments (Table 1) (29, 32). The costs of complications were obtained from a cost-analysis of cases of unexpected hospital use after endoscopy in 2007 (33). We added patient time costs to both. The costs of LYs with CRC care were obtained from an analysis of SEER-Medicare linked data and included copayments and patient time costs (31). We adjusted all costs to reflect the 2013 level using the U.S. consumer price index (34).

Assigning costs to LYs with CRC care also works two ways: On the one hand, screening prevents cancers, reducing the costs of CRC care. On the other hand, screening results in over-treatment of cancers, increasing these costs. The net effect can be either a reduction or an increase in costs.

Outcomes

For each cohort we quantified the effectiveness (i.e. the number of CRC cases prevented, CRC deaths prevented, LYs gained, and QALYs gained) and costs of once-only colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, and FIT screening, applying the conventional 3% annual discount rate for both.

Analyses

For all cohorts, we first determined the cost-effectiveness of each screening strategy compared with no screening. For each comorbidity level, we determined the upper age at which each screening strategy was cost-effective compared with no screening applying a threshold for the willingness to pay per QALY gained of $100,000.

We subsequently performed an analysis to determine the optimal screening strategy for each cohort; that is, the most effective, still cost-effective screening strategy. To do so, we first excluded all dominated screening strategies, i.e. those strategies that were more costly and less effective than (combinations of) other strategies. For all remaining strategies, the so-called efficient strategies, we determined the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio: the additional costs per additional QALY gained compared with the next less effective, efficient strategy. From the efficient strategies, we selected the optimal strategy again applying a threshold for the willingness to pay per QALY gained of $100,000.

Sensitivity Analyses

We repeated our analyses assuming 1) half and twice the base-case utility losses for colonoscopies, sigmoidoscopies, and complications; 2) a utility loss of 0.12, 0.18, 0.24, and 0.70 QALYs for each life-year with continuing care for stage I, II, III, and IV CRC, respectively; 3) 25% higher and 25% lower costs for colonoscopies, sigmoidoscopies, and FITs; 4) 25% higher and 25% lower costs for CRC care; 5) twice the base-case miss rates for adenomas and CRC for both sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy; 6) no surveillance in adenoma patients; 7) a 25% higher and a 25% lower risk for CRC in all cohorts; and 8) a threshold for the willingness to pay per QALY gained of $50,000. Furthermore, we explored the impact of FIT screening during two consecutive years.

Role of the Funding Source

The study described was supported by Grant Number U01-CA152959 from the National Cancer Institute as part of the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute. The National Cancer Institute had no role in the study's design, conduct, and reporting.

Institutional Review Board Review

This study did not include patient-specific information and was exempt from institutional review board review.

RESULTS

Effectiveness

The effectiveness of CRC screening in unscreened elderly declined with increasing age (Table 2). Once-only colonoscopy screening, for example, prevented fewer CRC deaths (4.5 versus 11.9 per 1,000 individuals) and resulted in fewer LYs gained (12.3 versus 68.5 per 1,000 individuals) in healthy 90-year-olds than in healthy 76-year-olds. Moreover, whereas colonoscopy screening prevented 15.4 CRC cases per 1,000 individuals aged 76, it resulted in over-diagnosis, and hence, over-treatment of 7.7 CRC cases per 1,000 individuals aged 90. As a result, colonoscopy screening resulted in a positive overall effect on length and quality of life (i.e. a net health benefit) in healthy 76-year-olds (67.2 QALYs gained per 1,000 individuals), whereas it resulted in a net harm in healthy 90-year-olds (1.7 QALYs lost per 1,000 individuals).

Table 2.

The Effectiveness of Once-Only Colonoscopy, Sigmoidoscopy, and FIT Screening in Elderly Without Prior Screening With No Comorbidity (compared with no screening; results per 1,000 individuals; 3% discounted).*

| CRC cases prevented† |

CRC deaths prevented |

LYs gained‡ |

Impact on quality of life (QALYs)§ | QALYs gained¶ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening strategy | Age | (A) |

Screening test (B) |

Diagnostic colonoscopies (C) |

Surveillance colonoscopies (D) |

Complications (E) |

LYs with CRC care∥ (F) |

(A+B+C+D+E+F) | ||

| Once-only colonoscopy screening | 76** | 15.4 | 11.9 | 68.5 | −5.5 | 0 | −3.2 | −0.6 | 8.1 | 67.2 |

| 80 | 10.4 | 10.7 | 52.9 | −5.5 | 0 | −2.8 | −0.7 | 3.0 | 46.9 | |

| 85 | 0.8 | 7.4 | 28.3 | −5.5 | 0 | −2.0 | −0.9 | −2.9 | 17.1 | |

| 90 | −7.7 | 4.5 | 12.3 | −5.5 | 0 | −1.4 | −1.1 | −6.1 | −1.7 | |

| Once-only sigmoidoscopy screening | 76 | 12.0 | 9.4 | 54.6 | −2.7 | −1.6 | −2.2 | −0.4 | 6.2 | 53.9 |

| 80 | 8.2 | 8.7 | 43.1 | −2.7 | −1.7 | −2.0 | −0.5 | 2.3 | 38.6 | |

| 85 | 0.6 | 6.0 | 23.1 | −2.7 | −1.7 | −1.4 | −0.6 | −2.3 | 14.3 | |

| 90 | −6.2 | 3.7 | 9.9 | −2.7 | −1.6 | −1.0 | −0.7 | −4.9 | −1.0 | |

| Once-only FIT screening | 76 | 1.7 | 4.1 | 25.9 | 0 | −0.4 | −0.5 | −0.1 | −0.6 | 24.2 |

| 80 | 0.2 | 4.2 | 22.5 | 0 | −0.4 | −0.4 | −0.1 | −2.2 | 19.2 | |

| 85 | −2.8 | 3.4 | 13.8 | 0 | −0.5 | −0.4 | −0.1 | −3.8 | 9.0 | |

| 90 | −6.2 | 2.3 | 6.6 | 0 | −0.5 | −0.3 | −0.2 | −4.7 | 0.9 | |

FIT = fecal immunochemical test; CRC = colorectal cancer; LY = life-year; QALY = quality-adjusted life-year

Individuals are classified as having no comorbidity if none of the following conditions is present: an ulcer, a history of acute myocardial infarction, rheumatologic disease, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, paralysis, cerebrovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, moderate or severe liver disease, chronic renal failure, dementia, cirrhosis and chronic hepatitis, or AIDS.

Negative values occur when the number of CRC cases prevented by screening is exceeded by the number of CRC cases over-diagnosed by screening.

The impact of screening on quantity of life.

The impact of the screening test, diagnostic colonoscopies, surveillance colonoscopies, complications, and LYs with CRC care on quality of life. Values are derived by multiplying number(s) of events with the corresponding utility loss(es) per event stated in Table 1. An example: When applying the once-only colonoscopy screening strategy, in each cohort, 1,000 individuals undergo a screening colonoscopy. As the utility loss per screening colonoscopy is 0.0055 QALYs, the total utility loss due to screening colonoscopies is 5.5 QALYs in each cohort.

Screening results in a gain of quality of life by preventing LYs with CRC care and a loss of quality of life by adding LYs with CRC care. The net effect can be a gain of quality of life (positive values) or a loss of quality of life (negative values). As a result of the shift from preventing to over-diagnosing CRC with increasing age, the net effect on quality of life becomes less favorable with age. Whereas once-only colonoscopy screening in unscreened elderly without comorbidity reduced the total number of LYs with CRC care for stage III or IV CRC at age 76 (−14 LYs per 1,000 individuals), it increased this number of LYs at age 90 (+16 LYs per 1,000 individuals).

The impact of screening on quantity and quality of life incorporated in one measure, i.e. the net health benefit of screening. Discrepancies between the columns might occur due to rounding.

More detailed results for this cohort are given in Appendix Table 2.

Compared with once-only colonoscopy screening, once-only sigmoidoscopy, and, particularly, once-only FIT screening were generally less effective (Table 2): in healthy 76-year-olds, for example, colonoscopy screening resulted in 67.2 QALYs gained per 1,000 individuals, whereas sigmoidoscopy and FIT screening resulted in 53.9 and 24.2 QALYs gained per 1,000 individuals, respectively. The only exceptions were observed at the most advanced ages, at which FIT screening was most effective; a result primarily explained by the zero utility loss associated with this test. In individuals with moderate and, particularly, severe comorbidity, screening was less effective than in individuals without comorbidity (Appendix Table 3).

Costs

Whereas the effectiveness of screening in unscreened elderly declined with increasing age, the net costs of screening increased substantially (Table 3). While colonoscopy screening was associated with a lifetime cost of $725,000 per 1,000 healthy 76-year-olds, it was associated with a lifetime cost of $2,130,000 per 1,000 healthy 90-year-olds. This increase was again explained by the shift from preventing to over-treating CRC with age.

Table 3.

The Costs of Once-Only Colonoscopy, Sigmoidoscopy, and FIT Screening in Elderly Without Prior Screening With No Comorbidity (compared with no screening; results per 1,000 individuals; 3% discounted).*

| Costs (*$1,000) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening strategy | Age | Screening test † | Diagnostic colonoscopies | Surveillance colonoscopies | Complications | LYs with CRC care ‡ | Total§ |

| Once-only colonoscopy screening | 76∥ | 983 | 0 | 569 | 98 | −925 | 725 |

| 80 | 987 | 0 | 484 | 114 | −483 | 1,102 | |

| 85 | 987 | 0 | 350 | 137 | 230 | 1,705 | |

| 90 | 986 | 0 | 239 | 168 | 737 | 2,130 | |

| Once-only sigmoidoscopy screening | 76 | 387 | 309 | 397 | 64 | −718 | 439 |

| 80 | 392 | 331 | 345 | 75 | −380 | 764 | |

| 85 | 392 | 330 | 251 | 89 | 189 | 1,251 | |

| 90 | 390 | 323 | 169 | 106 | 592 | 1,580 | |

| Once-only FIT screening | 76 | 42 | 80 | 88 | 14 | −7 | 218 |

| 80 | 42 | 87 | 78 | 17 | 130 | 355 | |

| 85 | 42 | 93 | 62 | 23 | 356 | 577 | |

| 90 | 42 | 98 | 46 | 29 | 541 | 756 | |

FIT = fecal immunochemical test; LY = life-year; CRC = colorectal cancer

Individuals are classified as having no comorbidity if none of the following conditions is present: an ulcer, a history of acute myocardial infarction, rheumatologic disease, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, paralysis, cerebrovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, moderate or severe liver disease, chronic renal failure, dementia, cirrhosis and chronic hepatitis, or AIDS.

At very advanced age, the costs of screening colonoscopies and sigmoidoscopies show a slight decline. This is explained by the small observed decrease in the prevalence of adenomas at very advanced age (11-18, 20, 21).

Screening prevents costs by preventing LYs with CRC care and induces costs by adding LYs with CRC care. The net effect can be an increase in costs (positive values) or a decrease in costs (negative values).

Discrepancies between the columns might occur due to rounding.

More detailed results for this cohort are given in Appendix Table 2.

Besides being most effective, colonoscopy screening was also most expensive (Table 3). In healthy 76-year-olds, for example, the costs of colonoscopy screening were $725,000 per 1,000 individuals compared with $439,000 and $218,000 for sigmoidoscopy and FIT screening, respectively. In individuals with moderate and, particularly, severe comorbidity, screening was not only less effective, but also more costly (Appendix Table 4).

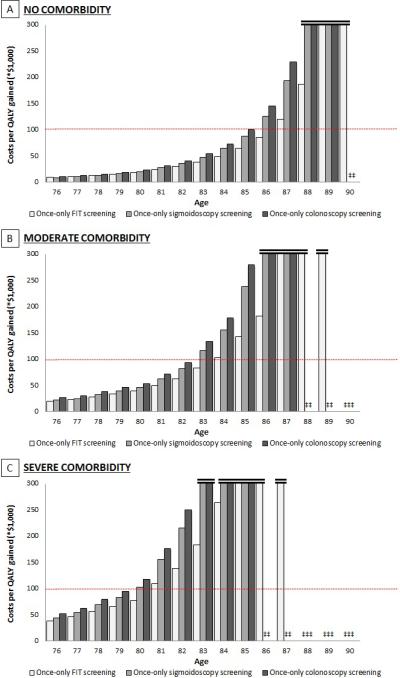

Cost-Effectiveness Compared with No Screening

As the effectiveness of screening declined with increasing age, and the costs increased substantially, the cost-effectiveness of screening deteriorated rapidly with age (Figure 1). In unscreened elderly without comorbidity, colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy screening were cost-effective up to age 85, whereas FIT screening was cost-effective up to age 86. In elderly with moderate comorbidity, colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy screening were cost-effective up to age 82, whereas FIT screening was cost-effective up to age 83. In those with severe comorbidity, colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy screening were cost-effective up to age 79, whereas FIT screening was cost-effective up to age 80.

Figure 1. The Cost-Effectiveness of Once-Only Colonoscopy, Sigmoidoscopy, and FIT Screening Compared with No Screening in Elderly Without Prior Screening with No (A), Moderate (B), and Severe Comorbidity (C) (3% discounted)*†.

*Individuals are classified as having moderate comorbidity if diagnosed with an ulcer, rheumatologic disease, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, paralysis, or cerebrovascular disease and in case of a history of acute myocardial infarction; as having severe comorbidity if diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, moderate or severe liver disease, chronic renal failure, dementia, cirrhosis and chronic hepatitis, or AIDS; and as having no comorbidity if none of these conditions is present.

†The dashed red line indicates a threshold for the willingness to pay per QALY gained of $100,000. Screening strategies costing less than $100,000 per QALY gained are considered cost-effective.

‡Screening strategy associated with a net health loss, rather than a benefit (Table 2 and Appendix Table 3).

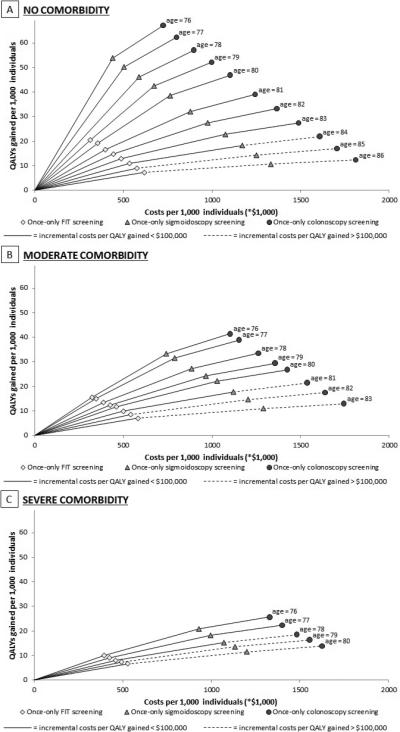

Incremental Cost-Effectiveness

Based on the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios of the efficient screening strategies, we determined the optimal screening strategy for each cohort. In unscreened elderly with no comorbidity, colonoscopy screening was most effective and still cost-effective up to age 83 (Figure 2 and Table 4); sigmoidoscopy screening was the optimal strategy at age 84; and FIT screening was the optimal strategy at ages 85 and 86. In elderly with moderate comorbidity, colonoscopy screening was the optimal strategy up to age 80, sigmoidoscopy screening was the optimal strategy at age 81, and FIT screening was the optimal strategy at ages 82 and 83. In those with severe comorbidity, colonoscopy screening was the optimal strategy up to age 77, followed by sigmoidoscopy screening at age 78, and FIT screening at ages 79 and 80.

Figure 2. The Incremental Costs-Effectiveness of the Efficient Screening Strategies in Elderly Without Prior Screening with No (A), Moderate (B), and Severe Comorbidity (C) (results per 1,000 individuals; 3% discounted)*†‡.

*Individuals are classified as having moderate comorbidity if diagnosed with an ulcer, rheumatologic disease, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, paralysis, or cerebrovascular disease and in case of a history of acute myocardial infarction; as having severe comorbidity if diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, moderate or severe liver disease, chronic renal failure, dementia, cirrhosis and chronic hepatitis, or AIDS; and as having no comorbidity if none of these conditions is present.

†In elderly without prior screening with no, moderate, and severe comorbidity, none of the screening strategies are cost-effective from age 87, 84, and 81 onwards, respectively (Figure 1).

‡For each age, the efficient screening strategies are connected by an efficiency fron er. A solid line indicates that the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of a screening strategy is lower than $100,000 per QALY gained, implying that the strategy is considered cost-effective. A dashed line indicates that the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of a screening strategy exceeds $100,000 per QALY gained, implying that the strategy is not considered cost-effective.

Table 4.

The Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratios (ICERs) of the Efficient Screening Strategies in Elderly Without Prior Screening by Comorbidity Status (QALYs gained, incremental QALYs gained, costs, and incremental costs per 1,000 individuals; 3% discounted; visually displayed in Figure 2).*†

| NO COMORBIDITY | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Screening strateg‡ | QALYs gained§ | Incremental QALYs gained∥ (A) | Costs (*$1,000)§ | Incremental costs (*$1,000)∥ (B) | ICER (*$1,000) (B/A) | Optimal screening strategy¶ |

| 76** | Sigmoidoscopy | 53.9 | 53.9 | 439 | 439 | 8 | |

| Colonoscopy | 67.2 | 13.3 | 725 | 285 | 21 | X | |

| 77** | Sigmoidoscopy | 50.3 | 50.3 | 503 | 503 | 10 | |

| Colonoscopy | 62.3 | 12.1 | 799 | 296 | 25 | X | |

| 78** | Sigmoidoscopy | 46.2 | 46.2 | 588 | 588 | 13 | |

| Colonoscopy | 57.1 | 10.9 | 898 | 310 | 29 | X | |

| 79 | FIT | 20.5 | 20.5 | 313 | 313 | 15 | |

| Sigmoidoscopy | 42.5 | 22.0 | 673 | 360 | 16 | ||

| Colonoscopy | 52.1 | 9.6 | 998 | 325 | 34 | X | |

| 80 | FIT | 19.2 | 19.2 | 355 | 355 | 18 | |

| Sigmoidoscopy | 38.6 | 19.4 | 764 | 409 | 21 | ||

| Colonoscopy | 46.9 | 8.4 | 1102 | 338 | 40 | X | |

| 81 | FIT | 16.6 | 16.6 | 398 | 398 | 24 | |

| Sigmoidoscopy | 32.1 | 15.5 | 878 | 480 | 31 | ||

| Colonoscopy | 39.0 | 7.0 | 1244 | 366 | 53 | X | |

| 82 | FIT | 14.8 | 14.8 | 444 | 444 | 30 | |

| Sigmoidoscopy | 27.5 | 12.7 | 976 | 532 | 42 | ||

| Colonoscopy | 33.3 | 5.8 | 1365 | 390 | 68 | X | |

| 83 | FIT | 12.9 | 12.9 | 488 | 488 | 38 | |

| Sigmoidoscopy | 22.8 | 9.9 | 1076 | 588 | 60 | ||

| Colonoscopy | 27.4 | 4.7 | 1490 | 414 | 89 | X | |

| 84 | FIT | 11.0 | 11.0 | 535 | 535 | 49 | |

| Sigmoidoscopy | 18.3 | 7.3 | 1171 | 636 | 87 | X | |

| Colonoscopy | 22.0 | 3.7 | 1608 | 437 | 119 | ||

| 85 | FIT | 9.0 | 9.0 | 577 | 577 | 64 | X |

| Sigmoidoscopy | 14.3 | 5.3 | 1251 | 674 | 126 | ||

| Colonoscopy | 17.1 | 2.7 | 1705 | 454 | 166 | ||

| 86 | FIT | 7.2 | 7.2 | 619 | 619 | 86 | X |

| Sigmoidoscopy | 10.7 | 3.4 | 1332 | 714 | 208 | ||

| Colonoscopy | 12.5 | 1.8 | 1810 | 478 | 261 | ||

| MODERATE COMORBIDITY | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Screening strategy‡ | QALYs gained§ | Incremental QALYs gained∥ (A) | Costs (*$1,000)§ | Incremental costs (*$1,000)∥ (B) | ICER (*$1,000)∥ (B/A) | Optimal screening strategy¶ |

| 76 | FIT | 15.6 | 15.6 | 324 | 324 | 21 | |

| Sigmoidoscopy | 33.4 | 17.8 | 742 | 418 | 23 | ||

| Colonoscopy | 41.4 | 8.0 | 1,102 | 361 | 45 | X | |

| 77 | FIT | 15.0 | 15.0 | 347 | 347 | 23 | |

| Sigmoidoscopy | 31.6 | 16.6 | 789 | 443 | 27 | ||

| Colonoscopy | 38.9 | 7.4 | 1,153 | 363 | 49 | X | |

| 78 | FIT | 13.5 | 13.5 | 387 | 387 | 29 | |

| Sigmoidoscopy | 27.3 | 13.8 | 885 | 497 | 36 | ||

| Colonoscopy | 33.5 | 6.2 | 1,262 | 377 | 61 | X | |

| 79 | FIT | 12.4 | 12.4 | 426 | 426 | 34 | |

| Sigmoidoscopy | 24.3 | 11.9 | 966 | 540 | 45 | ||

| Colonoscopy | 29.5 | 5.2 | 1,356 | 390 | 75 | X | |

| 80 | FIT | 11.7 | 11.7 | 460 | 460 | 39 | |

| Sigmoidoscopy | 22.2 | 10.5 | 1,029 | 569 | 54 | ||

| Colonoscopy | 26.8 | 4.6 | 1,425 | 396 | 86 | X | |

| 81 | FIT | 9.9 | 9.9 | 500 | 500 | 51 | |

| Sigmoidoscopy | 17.8 | 7.9 | 1,121 | 621 | 79 | X | |

| Colonoscopy | 21.5 | 3.7 | 1,537 | 416 | 113 | ||

| 82 | FIT | 8.6 | 8.6 | 542 | 542 | 63 | X |

| Sigmoidoscopy | 14.7 | 6.1 | 1,204 | 662 | 108 | ||

| Colonoscopy | 17.6 | 2.8 | 1,638 | 434 | 152 | ||

| 83 | FIT | 7.0 | 7.0 | 583 | 583 | 83 | X |

| Sigmoidoscopy | 11.0 | 4.1 | 1,290 | 707 | 174 | ||

| Colonoscopy | 13.0 | 2.0 | 1,744 | 453 | 230 | ||

| SEVERE COMORBIDITY | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Screening strategy† | QALYs gained§ | Incremental QALYs gained∥ (A) | Costs (*$1,000)§ | Incremental costs (*$1,000)∥ (B) | ICER (*$1,000) (B/A) | Optimal screening strategy¶ |

| 76 | FIT | 10.1 | 10.1 | 395 | 395 | 39 | |

| Sigmoidoscopy | 20.8 | 10.8 | 930 | 535 | 50 | ||

| Colonoscopy | 25.7 | 4.8 | 1,329 | 399 | 83 | X | |

| 77 | FIT | 9.1 | 9.1 | 425 | 425 | 47 | |

| Sigmoidoscopy | 18.2 | 9.1 | 995 | 571 | 62 | ||

| Colonoscopy | 22.4 | 4.1 | 1,400 | 404 | 98 | X | |

| 78 | FIT | 8.1 | 8.1 | 460 | 460 | 57 | |

| Sigmoidoscopy | 15.3 | 7.2 | 1,071 | 611 | 85 | X | |

| Colonoscopy | 18.6 | 3.3 | 1,483 | 412 | 124 | ||

| 79 | FIT | 7.4 | 7.4 | 493 | 493 | 66 | X |

| Sigmoidoscopy | 13.6 | 6.1 | 1,134 | 640 | 104 | ||

| Colonoscopy | 16.4 | 2.8 | 1,554 | 420 | 150 | ||

| 80 | FIT | 6.7 | 6.7 | 528 | 528 | 78 | X |

| Sigmoidoscopy | 11.6 | 4.8 | 1,200 | 672 | 139 | ||

| Colonoscopy | 13.9 | 2.3 | 1,625 | 424 | 185 | ||

QALY = quality-adjusted life-year; ICER = incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; FIT = fecal immunochemical test

Individuals are classified as having moderate comorbidity if diagnosed with an ulcer, rheumatologic disease, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, paralysis, or cerebrovascular disease and in case of a history of acute myocardial infarction; as having severe comorbidity if diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, moderate or severe liver disease, chronic renal failure, dementia, cirrhosis and chronic hepatitis, or AIDS; and as having no comorbidity if none of these conditions is present.

In elderly without prior screening with no, moderate, and severe comorbidity, none of the screening strategies are cost-effective from age 87, 84, and 81 onwards, respectively (Figure 1).

All screening strategies consist of a once-only screening examination followed by diagnostic and surveillance colonoscopies if indicated.

Compared with no screening.

Compared with the next less effective, efficient strategy, which is no screening for the first screening strategy mentioned at each age.

The most effective, still cost-effective screening strategy based on a threshold for the willingness to pay per QALY gained of $100,000.

In elderly without prior screening with no comorbidity aged 76 up to 78, FIT screening is dominated by a combination of sigmoidoscopy screening and no screening (Figure 2).

Sensitivity Analyses

Besides comorbidity status, the upper age at which screening was cost-effective was most sensitive to lowering the threshold for the willingness to pay per QALY gained to $50,000 (Appendix Table 5). Based on this threshold, screening unscreened elderly with no, moderate, and severe comorbidity should be considered up to age 84, 80, and 77, respectively. The upper ages at which screening should be considered were robust to all other sensitivity analyses (Appendix Table 5).

The tests that were indicated at specific ages did differ substantially between analyses (Appendix Table 5). Besides the threshold for the willingness to pay per QALY gained, the level of risk for CRC and the utility losses associated with colonoscopies, sigmoidoscopies, and complications were the most important factors in this respect.

In 84-year-olds without comorbidity and 78-year-olds with severe comorbidity, sigmoidoscopy screening was not cost-effective compared with FIT screening during two consecutive years. In 85-year-olds without comorbidity, 82-year-olds with moderate comorbidity, and 79- and 80-year-olds with severe comorbidity, FIT screening during two consecutive years was cost-effective compared with once-only FIT screening.

DISCUSSION

Our study shows, that in elderly without prior screening, screening remains cost-effective well beyond age 75 (the recommended age to discontinue screening in adequately screened individuals). In unscreened elderly with no, moderate, and severe comorbidity, CRC screening is cost-effective up to age 86, 83, and 80, respectively (Table 5). In unscreened elderly without comorbidity, colonoscopy screening is indicated up to age 83; sigmoidoscopy screening is indicated at age 84; and FIT screening is indicated at ages 85 and 86. In elderly with moderate comorbidity, colonoscopy screening is indicated up to age 80, sigmoidoscopy screening is indicated at age 81, and FIT screening is indicated at ages 82 and 83. In those with severe comorbidity, colonoscopy screening is indicated up to age 77, followed by sigmoidoscopy screening at age 78, and FIT screening at ages 79 and 80.

Table 5.

CRC Screening Indicated in Elderly Without Prior Screening: Results Summary

| Comorbidity status* | Up to what age should CRC screening be considered? | Which screening strategy is indicated at what age? | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||||||||||

| 76 | 77 | 78 | 79 | 80 | 81 | 82 | 83 | 84 | 85 | 86 | ||

| No comorbidity | 86 | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | SIG | FIT | FIT |

| Moderate comorbidity | 83 | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | SIG | FIT | FIT | |||

| Severe comorbidity | 80 | COL | COL | SIG | FIT | FIT | ||||||

CRC = colorectal cancer; COL = once-only colonoscopy screening; SIG = once-only sigmoidoscopy screening; FIT = once-only fecal immunochemical test screening

Individuals are classified as having moderate comorbidity if diagnosed with an ulcer, rheumatologic disease, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, paralysis, or cerebrovascular disease and in case of a history of acute myocardial infarction; as having severe comorbidity if diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, moderate or severe liver disease, chronic renal failure, dementia, cirrhosis and chronic hepatitis, or AIDS; and as having no comorbidity if none of these conditions is present.

In the special occasion in which an elderly individual is only willing to undergo one particular screening test, the cost-effectiveness of that screening test compared with no screening becomes relevant. In elderly without comorbidity, who only accept one screening modality, colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy screening can be considered up to age 85 and FIT screening can be considered up to age 86. The corresponding ages for elderly with moderate and severe comorbidity are 82 and 79 for colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy screening and 83 and 80 for FIT screening, respectively.

Although the incidence of CRC increases up to very advanced age (19), the effectiveness of screening declines with increasing age. This decline is primarily explained by the increasing risk for other cause mortality with age, which reduces both the probability that screening will prevent CRC mortality and the number of LYs gained if mortality is prevented. Moreover, the risks for screening induced harms, i.e. colonoscopy-related complications and, more importantly, over-diagnosis and over-treatment of CRC, increase with age (9). At the same time, the shift from preventing to over-treating CRC causes the net costs of screening to increase with age. Together, these phenomena explain the rapid deterioration of the cost-effectiveness of screening with increasing age.

Whereas colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, and FIT screening are almost equally effective when applied every 10, 5, and 1 year(s) from age 50 up to age 75, respectively (1, 2), colonoscopy screening is more effective than sigmoidoscopy and FIT screening when only one screening examination is performed. This is explained by its higher overall sensitivity for adenomas and CRC. However, as colonoscopies are more expensive than sigmoidoscopies and FITs, and as the effectiveness of all screening tests is very limited at very advanced age, colonoscopy screening is not cost-effective compared with sigmoidoscopy and FIT screening at the most advanced ages at which screening should be considered.

The fact that screening remains cost-effective up to a more advanced age in those without comorbidity than in those with comorbidity is explained by their more favorable life-expectancy. This increases the probability that screening will prevent CRC, increasing the effectiveness of screening, while simultaneously reducing its net costs through preventing CRC care.

To our knowledge, our study is the first to investigate the net health benefit and the cost-effectiveness of CRC screening in elderly aged over 75 without prior screening. An earlier study by Ko and Sonnenberg did demonstrate that the probability that screening prevents CRC mortality declines with increasing age, while the probability of screening-related complications increases with age (7). Furthermore, a study by Lin and colleagues demonstrated that the number of LYs gained by screening declines with age, resulting in an increase in the number of colonoscopies required per LY gained (8). However, neither of these studies quantified the most important adverse effect of screening in elderly adults: over-diagnosis and over-treatment of cancer, nor did they consider costs. As a result, these studies cannot easily be used to determine whether unscreened elderly should be screened or not.

Some other, more recent, studies have suggested that screening should be continued after age 75 (3, 4). However, these studies did not distinguish between adequately screened elderly and elderly without prior screening. Furthermore, these studies based their conclusions on CRC incidence data only. Our study demonstrates that quantification of all favorable and adverse health effects of screening as well as its costs is required.

Whereas the USPSTF selected its recommended screening strategies based on the number of colonoscopies required per LY gained (undiscounted),(1, 2) we based our conclusions on the appropriateness of screening on its costs per QALY gained (3% discounted). We did so for two reasons: First of all, to maximize population health, policy makers should be able to compare the efficiency of a wide range of health interventions; a resource utilization outcome measure does not allow for this. Secondly, effects on both length and quality of life should be considered: whereas colonoscopy screening of 1,000 unscreened, healthy 90-year-olds might still prevent CRC death in 5 individuals, it requires 1,000 individuals to undergo a screening, and possibly, surveillance colonoscopies, causing 28 complications and resulting in over-diagnosis, and possibly over-treatment, of CRC in 8 additional individuals. However, ultimately, the undiscounted numbers of colonoscopies required per LY gained associated with once-only colonoscopy screening in 83-year-olds with no comorbidity, 80-year-olds with moderate comorbidity, and 77-year-olds with severe comorbidity: 32, 32, and 35, respectively, were very comparable to the number of colonoscopies required per LY gained associated with colonoscopy screening as recommended by the USPSTF (i.e. at ages 50, 60, and 70), which was 30 according to MISCAN-Colon and 35 according to another microsimulation model (2).

Our study has two main limitations. First of all, in accordance with the analysis informing the USPSTF guidelines (2), we did not perform separate analyses by sex and race. However, we do not expect that results from such analyses would have differed much from the results presented in this paper. First of all, a substantial part of the difference in life-expectancy between males and females and between blacks and whites is explained by differences in the prevalence of moderate and severe comorbidity between these groups, and we did perform analyses by comorbidity status. Secondly, those with the most favorable life-expectancy (i.e. white females) are at lowest risk for CRC and vice versa. Hence, the impact of life-expectancy on the cost-effectiveness of screening is, at least partially, counter-balanced by the impact of CRC risk (35).

Furthermore, although we did perform sensitivity analyses on the level of risk for CRC, we did not perform separate analyses for identifiable high-risk subgroups of unscreened elderly, such as elderly with a family history of CRC (36). In those elderly, screening might be cost-effective up to a more advanced age.

Our analysis highlights some critical future research directions. First of all, we did not investigate how many round of FIT screening are indicated in relatively young elderly who are not willing to undergo a screening colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy. Secondly, we recognize that decisions on CRC screening should not be based on cost-effectiveness only, but also on patient preferences. This requires personalized information on the benefits, burden, and harms of screening. Although our study might provide some relevant information (Table 2 and Appendix Table 3), additional studies focusing on those outcomes most meaningful to patients are required. Finally, our analysis demonstrates that the cost-effectiveness of screening in elderly does not only depend on age, but also on comorbidity status. As this will also hold for adequately screened elderly, studies evaluating the appropriate age to stop screening in adequately screened elderly with no, moderate, and severe comorbidity are also required.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that in elderly without prior screening (23% of all U.S. elderly), CRC screening should be considered well beyond age 75. In unscreened elderly with no, moderate, and severe comorbidity, whose physical condition allows a colonoscopy, screening should be considered up to age 86, 83, and 80, respectively. At most of these ages, a screening colonoscopy is indicated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial Support Information: The study described was supported by Grant Number U01-CA152959 from the National Cancer Institute as part of the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET).

Appendix

Appendix Table 1.

Test Characteristics of Colonoscopy, Sigmoidoscopy, and FIT.

| Test Characteristic | Colonoscopy | Test Sigmoidoscopy | FIT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specificity | 90%* | 92%* | 97.7%‡ |

| Sensitivity | |||

| Small adenomas (≤5mm) | 75%† | 75%† | 0%‡ |

| Medium-sized adenomas (6-9mm) | 85%† | 85%† | 5.2%‡ |

| Large adenomas (≥10mm) | 95%† | 95%† | 26%‡ |

| CRCs that would not have been clinically detected in their current stage | 95%† | 95%† | 41%‡ |

| CRCs that would have been clinically detected in their current stage | 95%† | 95%† | 77%‡ |

| Reach | 95% reaches the cecum; the reach of the remaining 5% is distributed uniformly over colon and rectum | 100% reaches the rectosigmoid junction, 88% reaches the sigmoid-descending junction, 6% reaches the splenic flexure§ | whole colon and rectum |

| Complication rate | |||

| Positive test | increases exponentially with age (from 20 per 1,000 colonoscopies at age 76 to 48 per 1,000 colonoscopies at age 90∥) | 0 | 0 |

| Negative test | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mortality rate | |||

| Positive test | 0.033 per 1,000¶ | 0 | 0 |

| Negative test | 0 | 0 | 0 |

We assumed that in 10% of all negative colonoscopies and in 8% of all negative sigmoidoscopies a non-adenomatous lesion was detected, resulting in a polypectomy or a biopsy, respectively.

The sensitivity of colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy for the detection of adenomas and CRC within the reach of the endoscope was obtained from a systematic review on miss rates observed in tandem colonoscopy studies (39).

The test characteristics of FIT were fitted to the positivity rates and detection rates observed in the first screening round of the Dutch screening trial. We assumed that the probability that a CRC bleeds and thus the sensitivity of FIT for CRC depends on the time until clinical diagnosis, in concordance with our findings for gFOBT (25).

The reach of sigmoidoscopy was obtained from a study by Painter and colleagues (38).

Age-specific risks for complications of colonoscopy requiring a hospital admission or emergency department visit were obtained from a study by Warren and colleagues (9).

Appendix Table 2.

The Effects of Once-Only Colonoscopy Screening in 76-Year-Olds Without Prior Screening With No Comorbidity (results per 1,000 individuals; 3% discounted).*

| Screening | No screening | Screening - No screening† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| EFFECTS ON HEALTH CARE USE | |||

| Colonoscopies | |||

| Screening - polypectomy | 461 | 0 | 461 |

| Screening - no polypectomy | 539 | 0 | 539 |

| Surveillance - polypectomy | 219 | 0 | 219 |

| Surveillance - no polypectomy | 370 | 0 | 370 |

| Complications of colonoscopy | 16.2 | 0 | 16.2 |

| LYs with initial CRC care‡ | |||

| Stage I | 11.5 | 6.4 | 5.1 |

| Stage II | 8.0 | 12.4 | −4.4 |

| Stage III | 5.1 | 7.3 | −2.2 |

| Stage IV | 0.7 | 2.9 | −2.2 |

| LYs with continuing CRC care | |||

| Stage I | 92.8 | 34.9 | 57.9 |

| Stage II | 60.0 | 61.6 | −1.6 |

| Stage III | 33.9 | 30.7 | 3.2§ |

| Stage IV | 1.5 | 5.2 | −3.7 |

| LYs with terminal care - CRC | |||

| Stage I | 0.5 | 0.7 | −0.2 |

| Stage II | 1.0 | 2.6 | −1.6 |

| Stage III | 1.5 | 3.2 | −1.8 |

| Stage IV | 1.1 | 5.8 | −4.7 |

| LYs with terminal care - other cause | |||

| Stage I | 8.3 | 5.1 | 3.2 |

| Stage II | 5.4 | 9.3 | −4.0 |

| Stage III | 2.9 | 4.6 | −1.8 |

| Stage IV | 0.2 | 1.0 | −0.8 |

| EFFECTS ON HEALTH | |||

| CRC cases | 27.9 | 43.4 | −15.4 |

| CRC deaths | 4.5 | 16.4 | −11.9 |

| LYs lost due to CRC (A) | 32.5 | 100.9 | −68.5∥ |

| Utility losses (QALYs) | |||

| Screening colonoscopies | 5.5 | 0 | 5.5 |

| Surveillance colonoscopies | 3.2 | 0 | 3.2 |

| Complications of colonoscopy | 0.6 | 0 | 0.6 |

| LYs with CRC care | 25.7 | 33.8 | −8.1 |

| Total (B) | 35.1 | 33.8 | 1.3 |

| QALYs lost (A+B) | 67.5 | 134.7 | −67.2¶ |

| EFFECTS ON COSTS (*$1,000) | |||

| Screening colonoscopies | 983 | 0 | 983 |

| Surveillance colonoscopies | 569 | 0 | 569 |

| Complications of colonoscopy | 98 | 0 | 98 |

| LYs with CRC care | 2,404 | 3,329 | −925 |

| Total | 4,054 | 3,329 | 725** |

LY = life-year; CRC = colorectal cancer; QALY = quality-adjusted life-year

Individuals are classified as having no comorbidity if none of the following conditions is present: an ulcer, a history of acute myocardial infarction, rheumatologic disease, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, paralysis, cerebrovascular disease, constructive obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, moderate or severe liver disease, chronic renal failure, dementia, cirrhosis and chronic hepatitis, or AIDS.

Discrepancies between columns might occur due to rounding.

As screening results in prevention and earlier detection of CRC, it reduces the total numbers of LYs with initial care for CRC, terminal care for CRC, and terminal care for other causes in CRC patients; however, as screening improves the average survival of CRC patients, it increases the total number of LYs with continuing care for CRC.

The increase in LYs with continuing care for stage III CRC is explained by the more favorable average survival that we model for screen-detected versus clinically detected cancers as described in the Model Appendix.

The number of LYs gained by screening (Table 2).

The number of QALYs gained by screening (Table 2).

The costs of screening (Table 3).

Appendix Table 3.

The Effectiveness of Once-Only Colonoscopy, Sigmoidoscopy, and FIT Screening in Elderly Without Prior Screening With Moderate and Severe Comorbidity (compared with no screening; results per 1,000 individuals; 3% discounted).*

| MODERATE COMORBIDITY | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRC cases prevented† |

CRC deaths prevented |

LYs gained‡ |

Impact on quality of life (QALYs)§ | QALYs gained¶ | ||||||

| Screening strategy | Age | (A) |

Screening test (B) |

Diagnostic colonoscopies (C) |

Surveillance colonoscopies (D) |

Complications (E) |

LYs with CRC care∥ (F) |

(A+B+C+D+E+F) | ||

| Once-only colonoscopy screening | 76 | 8.8 | 9.0 | 46.3 | −5.5 | 0 | −2.6 | −0.6 | 3.8 | 41.4 |

| 80 | 4.0 | 8.1 | 35.2 | −5.5 | 0 | −2.2 | −0.7 | 0.0 | 26.8 | |

| 85 | −4.3 | 5.6 | 18.9 | −5.5 | 0 | −1.6 | −0.8 | −4.2 | 6.8 | |

| 90 | −11.0 | 3.5 | 8.8 | −5.5 | 0 | −1.1 | −1.0 | −6.1 | −4.8 | |

| Once-only sigmoidoscopy screening | 76 | 6.8 | 7.2 | 36.9 | −2.7 | −1.6 | −1.8 | −0.4 | 2.9 | 33.4 |

| 80 | 3.1 | 6.6 | 28.7 | −2.7 | −1.7 | −1.6 | −0.4 | −0.1 | 22.2 | |

| 85 | −3.5 | 4.6 | 15.4 | −2.7 | −1.7 | −1.1 | −0.5 | −3.4 | 5.9 | |

| 90 | −8.8 | 2.9 | 7.1 | −2.7 | −1.6 | −0.7 | −0.6 | −4.9 | −3.5 | |

| Once-only FIT screening | 76 | −0.1 | 3.3 | 17.9 | 0 | −0.4 | −0.4 | −0.1 | −1.5 | 15.6 |

| 80 | −1.9 | 3.4 | 15.4 | 0 | −0.4 | −0.4 | −0.1 | −2.8 | 11.7 | |

| 85 | −4.8 | 2.7 | 9.4 | 0 | −0.5 | −0.3 | −0.1 | −4.0 | 4.6 | |

| 90 | −7.7 | 1.9 | 4.8 | 0 | −0.5 | −0.2 | −0.2 | −4.4 | −0.5 | |

| SEVERE COMORBIDITY | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRC cases prevented† |

CRC deaths prevented |

LYs gained‡ |

Impact on quality of life (QALYs)§ | QALYs gained¶ | ||||||

| Screening strategy | Age | (A) |

Screening test (B) |

Diagnostic colonoscopies (C) |

Surveillance colonoscopies (D) |

Complications (E) |

LYs with CRC care∥ (F) |

(A+B+C+D+E+F) | ||

| Once-only colonoscopy screening | 76 | 2.6 | 6.7 | 32.3 | −5.5 | 0 | −2.0 | −0.5 | 1.4 | 25.7 |

| 80 | −2.2 | 5.9 | 23.3 | −5.5 | 0 | −1.6 | −0.6 | −1.7 | 13.9 | |

| 85 | −9.4 | 4.0 | 12.2 | −5.5 | 0 | −1.1 | −0.8 | −4.5 | 0.4 | |

| 90 | −14.6 | 2.6 | 5.8 | −5.5 | 0 | −0.7 | −1.0 | −5.7 | −7.1 | |

| Once-only sigmoidoscopy screening | 76 | 2.0 | 5.3 | 25.8 | −2.7 | −1.6 | −1.4 | −0.3 | 1.1 | 20.8 |

| 80 | −1.9 | 4.8 | 19.0 | −2.7 | −1.7 | −1.2 | −0.4 | −1.4 | 11.6 | |

| 85 | −7.6 | 3.3 | 10.0 | −2.7 | −1.7 | −0.8 | −0.5 | −3.6 | 0.6 | |

| 90 | −11.7 | 2.1 | 4.6 | −2.7 | −1.6 | −0.5 | −0.6 | −4.5 | −5.4 | |

| Once-only FIT screening | 76 | −2.2 | 2.5 | 12.7 | 0 | −0.4 | −0.3 | −0.1 | −1.8 | 10.1 |

| 80 | −4.2 | 2.5 | 10.4 | 0 | −0.4 | −0.3 | −0.1 | −2.9 | 6.7 | |

| 85 | −7.1 | 2.0 | 6.2 | 0 | −0.5 | −0.2 | −0.1 | −3.7 | 1.7 | |

| 90 | −9.5 | 1.4 | 3.2 | 0 | −0.5 | −0.1 | −0.2 | −4.0 | −1.7 | |

FIT = fecal immunochemical test; CRC = colorectal cancer; LY = life-year; QALY = quality-adjusted life-year

Individuals are classified as having moderate comorbidity if diagnosed with an ulcer, rheumatologic disease, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, paralysis, or cerebrovascular disease and in case of a history of acute myocardial infarction and as having severe comorbidity if diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, moderate or severe liver disease, chronic renal failure, dementia, cirrhosis and chronic hepatitis, or AIDS.

Negative values occur when the number of CRC cases prevented by screening is exceeded by the number of CRC cases over-diagnosed by screening.

The impact of screening on quantity of life.

The impact of the screening test, diagnostic colonoscopies, surveillance colonoscopies, complications, and LYs with CRC care on quality of life. Values are derived by multiplying number(s) of events with the corresponding utility loss(es) per event stated in Table 1. An example: When applying the once-only colonoscopy screening strategy, in each cohort, 1,000 individuals undergo a screening colonoscopy. As the utility loss per screening colonoscopy is 0.0055 QALYs, the total utility loss due to screening colonoscopies is 5.5 QALYs in each cohort.

Screening results in a gain of quality of life by preventing LYs with CRC care and a loss of quality of life by adding LYs with CRC care. The net effect can be a gain of quality of life (positive values) or a loss of quality of life (negative values). As a result of the shift from preventing to over-diagnosing CRC with increasing age, the net effect on quality of life becomes less favorable with age.

The impact of screening on quantity and quality of life incorporated in one measure, i.e. the net health benefit of screening. Discrepancies between the columns might occur due to rounding.

Appendix Table 4.

The Costs of Once-Only Colonoscopy, Sigmoidoscopy, and FIT Screening in Elderly Without Prior Screening With Moderate and Severe Comorbidity (compared with no screening; results per 1,000 individuals; 3% discounted).*

| MODERATE COMORBIDITY | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Costs (*$1,000) | |||||||

| Screening strategy | Age |

Screening test † |

Diagnostic colonoscopies |

Surveillance colonoscopies |

Complications |

LYs with CRC care ‡ |

Total§ |

| Once-only colonoscopy screening | 76 | 983 | 0 | 462 | 90 | −434 | 1,102 |

| 80 | 987 | 0 | 388 | 106 | −57 | 1,425 | |

| 85 | 987 | 0 | 278 | 131 | 502 | 1,898 | |

| 90 | 986 | 0 | 185 | 161 | 838 | 2,170 | |

| Once-only sigmoidoscopy screening | 76 | 387 | 309 | 323 | 58 | −336 | 742 |

| 80 | 392 | 331 | 278 | 69 | −41 | 1029 | |

| 85 | 392 | 330 | 199 | 84 | 409 | 1414 | |

| 90 | 390 | 323 | 132 | 100 | 673 | 1618 | |

| Once-only FIT screening | 76 | 42 | 80 | 72 | 13 | 116 | 324 |

| 80 | 42 | 87 | 63 | 16 | 252 | 460 | |

| 85 | 42 | 93 | 50 | 22 | 448 | 655 | |

| 90 | 42 | 98 | 36 | 28 | 578 | 782 | |

| SEVERE COMORBIDITY | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Costs (*$1,000) | |||||||

| Screening strategy | Age |

Screening test † |

Diagnostic colonoscopies |

Surveillance colonoscopies |

Complications |

LYs with CRC care ‡ |

Total§ |

| Once-only colonoscopy screening | 76 | 983 | 0 | 354 | 83 | −91 | 1,329 |

| 80 | 987 | 0 | 288 | 99 | 250 | 1,625 | |

| 85 | 987 | 0 | 199 | 123 | 658 | 1,967 | |

| 90 | 986 | 0 | 131 | 154 | 868 | 2,139 | |

| Once-only sigmoidoscopy screening | 76 | 387 | 309 | 248 | 52 | −67 | 930 |

| 80 | 392 | 331 | 206 | 63 | 207 | 1200 | |

| 85 | 392 | 330 | 143 | 77 | 534 | 1477 | |

| 90 | 390 | 323 | 94 | 95 | 698 | 1600 | |

| Once-only FIT screening | 76 | 42 | 80 | 56 | 12 | 204 | 395 |

| 80 | 42 | 87 | 47 | 15 | 337 | 528 | |

| 85 | 42 | 93 | 36 | 20 | 493 | 685 | |

| 90 | 42 | 98 | 26 | 27 | 576 | 769 | |

FIT = fecal immunochemical test; LY = life-year; CRC = colorectal cancer

Individuals are classified as having moderate comorbidity if diagnosed with an ulcer, rheumatologic disease, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, paralysis, or cerebrovascular disease and in case of a history of acute myocardial infarction and as having severe comorbidity if diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, moderate or severe liver disease, chronic renal failure, dementia, cirrhosis and chronic hepatitis, or AIDS.

At very advanced age, the costs of screening colonoscopies and sigmoidoscopies show a slight decline. This is explained by the small observed decrease in the prevalence of adenomas at very advanced age (11-18, 20, 21).

Screening prevents costs by preventing LYs with CRC care and induces costs by adding LYs with CRC care. The net effect can be an increase in costs (positive values) or a decrease in costs (negative values).

Discrepancies between the columns might occur due to rounding.

Appendix Table 5.

CRC Screening Indicated in Elderly Without Prior Screening: Results of Sensitivity Analyses.

| NO COMORBIDITY | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis | Up to what age should CRC screening be considered? | Which screening strategy is indicated at what age? | ||||||||||||||

| Age | ||||||||||||||||

| 76 | 77 | 78 | 79 | 80 | 81 | 82 | 83 | 84 | 85 | 86 | 87 | 88 | 89 | 90 | ||

| Base Case | 86 | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | SIG | FIT | FIT | ||||

| Utility loss colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, complication*0.5 | 86 | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | SIG | FIT | ||||

| Utility loss colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, complication*2 | 86 | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | SIG | FIT | FIT | FIT | FIT | ||||

| Utility loss LYs with continuing care stage I, II CRC = 0.12, 0.18 | 84 | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | SIG | SIG | ||||||

| Costs of colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, FIT*1.25 | 86 | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | SIG | FIT | FIT | FIT | ||||

| Costs of colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, FIT*0.75 | 86 | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | SIG | FIT | ||||

| Costs of CRC care*1.25 | 86 | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | SIG | FIT | FIT | ||||

| Costs of CRC care*0.75 | 87 | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | SIG | FIT | FIT | FIT | |||

| Miss rates colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy*2 | 86 | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | FIT | FIT | FIT | ||||

| No surveillance in adenoma patients | 86 | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | SIG | FIT | ||||

| CRC risk*1.25 | 86 | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | FIT | ||||

| CRC risk*0.75 | 86 | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | SIG | SIG | SIG | FIT | FIT | FIT | ||||

| 2 annual FITs as an additional screening strategy | 86 | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | 2FITs | 2FITs | FIT | ||||

| Threshold willingness to pay per QALY gained = $50,000 | 84 | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | SIG | SIG | FIT | FIT | ||||||

| MODERATE COMORBIDITY | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis | Up to what age should CRC screening be considered? | Which screening strategy is indicated at what age? | ||||||||||||||

| Age | ||||||||||||||||

| 76 | 77 | 78 | 79 | 80 | 81 | 82 | 83 | 84 | 85 | 86 | 87 | 88 | 89 | 90 | ||

| Base Case | 83 | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | SIG | FIT | FIT | |||||||

| Utility loss colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, complication*0.5 | 84 | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | SIG | FIT | FIT | ||||||

| Utility loss colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, complication*2 | 83 | COL | COL | COL | SIG | FIT | FIT | FIT | FIT | |||||||

| Utility loss LYs with continuing care stage I, II CRC = 0.12, 0.18 | 81 | COL | COL | COL | COL | SIG | SIG | |||||||||

| Costs of colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, FIT*1.25 | 83 | COL | COL | COL | COL | SIG | FIT | FIT | FIT | |||||||

| Costs of colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, FIT*0.75 | 84 | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | SIG | FIT | FIT | ||||||

| Costs of CRC care*1.25 | 83 | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | SIG | FIT | FIT | |||||||

| Costs of CRC care*0.75 | 84 | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | SIG | FIT | FIT | FIT | ||||||

| Miss rates colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy*2 | 83 | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | SIG | FIT | FIT | |||||||

| No surveillance in adenoma patients | 84 | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | FIT | FIT | ||||||

| CRC risk*1.25 | 83 | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | FIT | |||||||

| CRC risk*0.75 | 83 | COL | COL | SIG | SIG | SIG | FIT | FIT | FIT | |||||||

| 2 annual FITs as an additional screening strategy | 83 | COL | COL | COL | COL | COL | SIG | 2FITs | FIT | |||||||

| Threshold willingness to pay per QALY gained = $50,000 | 80 | COL | COL | SIG | SIG | FIT | ||||||||||

| SEVERE COMORBIDITY | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis | Up to what age should CRC screening be considered? | Which screening strategy is indicated at what age? | ||||||||||||||

| Age | ||||||||||||||||

| 76 | 77 | 78 | 79 | 80 | 81 | 82 | 83 | 84 | 85 | 86 | 87 | 88 | 89 | 90 | ||

| Base Case | 80 | COL | COL | SIG | FIT | FIT | ||||||||||

| Utility loss colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, complication*0.5 | 80 | COL | COL | COL | SIG | SIG | ||||||||||

| Utility loss colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, complication*2 | 80 | SIG | FIT | FIT | FIT | FIT | ||||||||||

| Utility loss LYs with continuing care stage I, II CRC = 0.12, 0.18 | 78 | COL | SIG | SIG | ||||||||||||

| Costs of colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, FIT*1.25 | 80 | SIG | SIG | FIT | FIT | FIT | ||||||||||

| Costs of colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, FIT*0.75 | 80 | COL | COL | COL | SIG | SIG | ||||||||||

| Costs of CRC care*1.25 | 80 | COL | COL | SIG | SIG | FIT | ||||||||||

| Costs of CRC care*0.75 | 81 | COL | COL | SIG | FIT | FIT | FIT | |||||||||

| Miss rates colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy*2 | 80 | COL | COL | FIT | FIT | FIT | ||||||||||

| No surveillance in adenoma patients | 81 | COL | COL | COL | SIG | FIT | FIT | |||||||||

| CRC risk*1.25 | 80 | COL | COL | COL | COL | FIT | ||||||||||

| CRC risk*0.75 | 80 | SIG | SIG | FIT | FIT | FIT | ||||||||||

| 2 annual FITs as an additional screening strategy | 80 | COL | COL | 2FITs | 2FITs | 2FITs | ||||||||||

| Threshold willingness to pay per QALY gained = $50,000 | 77 | SIG | FIT | |||||||||||||

CRC = colorectal cancer; LY = life-year; QALY = quality-adjusted life-year; COL = once-only colonoscopy screening; SIG = once-only sigmoidoscopy screening; FIT = once-only fecal immunochemical test screening; 2FITs = fecal immunochemical test screening during two consecutive years

Individuals are classified as having moderate comorbidity if diagnosed with an ulcer, rheumatologic disease, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, paralysis, or cerebrovascular disease, and in case of a history of acute myocardial infarction; as having severe comorbidity if diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, moderate or severe liver disease, chronic renal failure, dementia, cirrhosis and chronic hepatitis or AIDS; and as having no comorbidity if none of these conditions is present.

REFERENCES

- 1.Screening for colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(9):627–37. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-9-200811040-00243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zauber AG, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Knudsen AB, Wilschut J, van Ballegooijen M, Kuntz KM. Evaluating test strategies for colorectal cancer screening: a decision analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(9):659–69. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-9-200811040-00244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rozen P, Liphshitz I, Barchana M. The changing epidemiology of colorectal cancer and its relevance for adapting screening guidelines and methods. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2011;20(1):46–53. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e328341e309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shellnut JK, Wasvary HJ, Grodsky MB, Boura JA, Priest SG. Evaluating the age distribution of patients with colorectal cancer: are the United States Preventative Services Task Force guidelines for colorectal cancer screening appropriate? Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53(1):5–8. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181bc01d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shapiro JA, Klabunde CN, Thompson TD, Nadel MR, Seeff LC, White A. Patterns of colorectal cancer test use, including CT colonography, in the 2010 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(6):895–904. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodwin JS, Singh A, Reddy N, Riall TS, Kuo YF. Overuse of screening colonoscopy in the Medicare population. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(15):1335–43. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ko CW, Sonnenberg A. Comparing risks and benefits of colorectal cancer screening in elderly patients. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(4):1163–70. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin OS, Kozarek RA, Schembre DB, Ayub K, Gluck M, Drennan F, et al. Screening colonoscopy in very elderly patients: prevalence of neoplasia and estimated impact on life expectancy. JAMA. 2006;295(20):2357–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.20.2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Mariotto AB, Meekins A, Topor M, Brown ML, et al. Adverse events after outpatient colonoscopy in the Medicare population. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(12):849–57. W152. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-12-200906160-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rutter CM, Johnson EA, Feuer EJ, Knudsen AB, Kuntz KM, Schrag D. Secular trends in colon and rectal cancer relative survival. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(23):1806–13. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blatt L. Polyps of the Colon and Rectum: Incidence and Distribution. Dis Colon Rectum. 1961;4:277–82. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arminski TC, McLean DW. Incidence and Distribution of Adenomatous Polyps of the Colon and Rectum Based on 1,000 Autopsy Examinations. Dis Colon Rectum. 1964;7:249–61. doi: 10.1007/BF02630528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bombi JA. Polyps of the colon in Barcelona, Spain. An autopsy study. Cancer. 1988;61(7):1472–6. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19880401)61:7<1472::aid-cncr2820610734>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chapman I. Adenomatous polypi of large intestine: incidence and distribution. Ann Surg. 1963;157:223–6. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196302000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark JC, Collan Y, Eide TJ, Esteve J, Ewen S, Gibbs NM, et al. Prevalence of polyps in an autopsy series from areas with varying incidence of large-bowel cancer. Int J Cancer. 1985;36(2):179–86. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910360209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jass JR, Young PJ, Robinson EM. Predictors of presence, multiplicity, size and dysplasia of colorectal adenomas. A necropsy study in New Zealand. Gut. 1992;33(11):1508–14. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.11.1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johannsen LG, Momsen O, Jacobsen NO. Polyps of the large intestine in Aarhus, Denmark. An autopsy study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1989;24(7):799–806. doi: 10.3109/00365528909089217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rickert RR, Auerbach O, Garfinkel L, Hammond EC, Frasca JM. Adenomatous lesions of the large bowel: an autopsy survey. Cancer. 1979;43(5):1847–57. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197905)43:5<1847::aid-cncr2820430538>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Cancer Statistics Branch Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program SEER*Stat Database: Incidence - SEER 9 Regs Limited-Use, Nov 2002 Sub (1973-2000) released April 2003, based on the November 2002 submission, 2003. Accessed at: www.seer.cancer.gov.

- 20.Vatn MH, Stalsberg H. The prevalence of polyps of the large intestine in Oslo: an autopsy study. Cancer. 1982;49(4):819–25. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820215)49:4<819::aid-cncr2820490435>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams AR, Balasooriya BA, Day DW. Polyps and cancer of the large bowel: a necropsy study in Liverpool. Gut. 1982;23(10):835–42. doi: 10.1136/gut.23.10.835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atkin WS, Edwards R, Kralj-Hans I, Wooldrage K, Hart AR, Northover JM, et al. Once-only flexible sigmoidoscopy screening in prevention of colorectal cancer: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9726):1624–33. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60551-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hardcastle JD, Chamberlain JO, Robinson MH, Moss SM, Amar SS, Balfour TW, et al. Randomised controlled trial of faecal-occult-blood screening for colorectal cancer. Lancet. 1996;348(9040):1472–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03386-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jorgensen OD, Kronborg O, Fenger C. A randomised study of screening for colorectal cancer using faecal occult blood testing: results after 13 years and seven biennial screening rounds. Gut. 2002;50(1):29–32. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, van Ballegooijen M, Boer R, Zauber A, Habbema JD. A novel hypothesis on the sensitivity of the fecal occult blood test: Results of a joint analysis of 3 randomized controlled trials. Cancer. 2009;115(11):2410–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mandel JS, Church TR, Ederer F, Bond JH. Colorectal cancer mortality: effectiveness of biennial screening for fecal occult blood. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91(5):434–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.5.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cho H, Klabunde CN, Yabroff KR, Wang Z, Meekins A, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, et al. Comorbidity-adjusted life expectancy: a new tool to inform recommendations for optimal screening strategies. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(10):667–76. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-10-201311190-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lieberman DA, Rex DK, Winawer SJ, Giardiello FM, Johnson DA, Levin TR. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after screening and polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(3):844–57. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.The United States Department of Labor [January 16th 2013];Bureau of Labor Statistics. Current Employment Statistics - CES (National) Accessed at: http://www.bls.gov/web/empsit/ceseesummary.htm.

- 30.Ness RM, Holmes AM, Klein R, Dittus R. Utility valuations for outcome states of colorectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(6):1650–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yabroff KR, Lamont EB, Mariotto A, Warren JL, Topor M, Meekins A, et al. Cost of care for elderly cancer patients in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(9):630–41. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zauber AG, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Wilschut J, Knudsen AB, Ballegooijen Mv, Kuntz KM. Cost-effectiveness of DNA stool testing to screen for colorectal cancer. 2007 doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-153-6-201009210-00004. Accessed at: https://www.cms.hhs.gov/mcd/viewtechassess.asp?where5index&tid552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Leffler DA, Kheraj R, Garud S, Neeman N, Nathanson LA, Kelly CP, et al. The incidence and cost of unexpected hospital use after scheduled outpatient endoscopy. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(19):1752–7. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.The United States Department of Labor [September 23rd 2013];Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index. Accessed at: http://www.bls.gov/cpi/

- 35.Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, van Ballegooijen M, Zauber AG, Boer R, Wilschut J, Winawer SJ, et al. Individualizing colonoscopy screening by sex and race. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70(1):96–108, e1-24. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Freedman AN, Slattery ML, Ballard-Barbash R, Willis G, Cann BJ, Pee D, et al. Colorectal cancer risk prediction tool for white men and women without known susceptibility. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(5):686–93. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.4797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gatto NM, Frucht H, Sundararajan V, Jacobson JS, Grann VR, Neugut AI. Risk of perforation after colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy: a population-based study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(3):230–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.3.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Painter J, Saunders DB, Bell GD, Williams CB, Pitt R, Bladen J. Depth of insertion at flexible sigmoidoscopy: implications for colorectal cancer screening and instrument design. Endoscopy. 1999;31(3):227–31. doi: 10.1055/s-1999-13673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Rijn JC, Reitsma JB, Stoker J, Bossuyt PM, van Deventer SJ, Dekker E. Polyp miss rate determined by tandem colonoscopy: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(2):343–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.