Abstract

Objective(s)

The clinical translation of tissue-engineered vascular grafts has been demonstrated in children. The remodeling of biodegradable, cell-seeded scaffolds to functional neovessels is partially attributed to matrix metalloproteinases. Noninvasive assessment of matrix metalloproteinase activity may indicate graft remodeling and elucidate the progression of neovessel formation. Therefore, matrix metalloproteinase activity was evaluated in grafts implanted in lambs using in vivo and ex vivo hybrid imaging. Graft growth and remodeling was quantified using in vivo X-ray computed tomography angiography.

Methods

Cell-seeded and unseeded scaffolds were implanted in lambs (n=5) as inferior vena cava interposition grafts. At 2 and 6 months post-implantation, in vivo angiography assessed graft morphology. In vivo and ex vivo single photon emission tomography/X-ray computed tomography imaging was performed with a radiolabeled compound targeting matrix metalloproteinase activity at 6 months. Neotissue was examined at 6 months using qualitative histologic and immunohistochemical staining and quantitative biochemical analysis.

Results

Seeded grafts demonstrated significant luminal and longitudinal growth from 2 to 6 months. In vivo imaging revealed subjectively higher matrix metalloproteinase activity in grafts vs. native tissue. Ex vivo imaging confirmed a quantitative increase in matrix metalloproteinase activity and demonstrated higher activity in unseeded vs. seeded grafts. Glycosaminoglycan content was increased in seeded grafts vs. unseeded grafts, without significant differences in collagen content.

Conclusions

Matrix metalloproteinase activity remains elevated in tissue-engineered grafts 6 months post-implantation and may indicate remodeling. Optimization of in vivo imaging to noninvasively evaluate matrix metalloproteinase activity may assist in serial assessment of vascular graft remodeling.

Introduction

Our research team developed the first tissue engineered vascular graft (TEVG) to be used in humans 1 and applied this technology in a clinical trial for congenital heart surgery.2 We are currently conducting the first FDA approved clinical trial examining the safety and efficacy of TEVG implantation in children within the United States.3 The TEVGs are constructed with autologous bone marrow mononuclear cells (BM-MNCs) seeded onto a biodegradable scaffold 4 and demonstrate growth potential in vivo,5 making the grafts ideally suited for application in infants and children.

The transition of a cell-seeded scaffold to a neovessel is a process characterized by scaffold degradation as a result of hydrolysis, cellular infiltration, and extraceullar matrix (ECM) deposition and remodeling.6 Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are enzymes that are thought to play important roles in tissue homeostasis and functional growth and may significantly contribute to ECM remodeling during neovessel formation.6,7 Specifically, MMP-2 and -9 are basement membrane-degrading MMPs that can play critical roles in ECM remodeling. Prior post-mortem examination of TEVGs implanted in a murine model has demonstrated progressively higher MMP-2 expression over a 4-week time course following TEVG implantation, while MMP-9 expression peaked at 1 week after surgery and significantly decreased by 4 weeks.6 The elevated expression of MMP-2 within a murine model of TEVG is consistent with the post-mortem findings of Cummings et al.,7 who observed elevated MMP-2 expression in a lamb model of TEVG implantation; however, MMP-9 expression also remained elevated for 80 weeks following implantation. These results suggest that MMPs may play a role in the remodeling of TEVGs and that this process may be prolonged for many months following implantation.

Current clinical imaging techniques for serial assessment of TEVG remodeling have focused on evaluation of morphological changes with X-ray computed tomography (CT) and MR angiography;2,5 however, these approaches do not provide information related to the underlying mechanisms responsible for ongoing neovessel formation. Targeted imaging of MMP activity has been previously demonstrated in animal models of atherosclerosis,8–12 vascular remodeling, 13,14 and myocardial infarction 15,16 with single-photon emission tomography (SPECT) and magnetic resonance (MR) approaches. Additionally, near-infrared (NIR) fluorescence imaging has indicated progressive remodeling in a murine model of TEVG implantation that was associated with qualitative elevations in MMP-2 and -9 activity.17 The technetium-99m (99mTc)-labeled tracer, 99mTc-RP805, is a broad-spectrum MMP-targeted compound used for SPECT/CT imaging that may localize to the site of ECM remodeling and provide an opportunity to serially assess the progression of TEVG remodeling and the formation of functional neotissue. Therefore, we hypothesize that 99mTc-RP805 SPECT/CT imaging of MMP activity can complement standard noninvasive imaging approaches and may serve as a useful tool for serial assessment of neovessel formation. To test this hypothesis, we evaluated the feasibility of in vivo and ex vivo SPECT/CT imaging of MMP activity within TEVGs in a clinically relevant large animal model 6 months following TEVG implantation and evaluated serial changes in TEVG morphology using CT angiography.

Materials and Methods

Graft scaffold

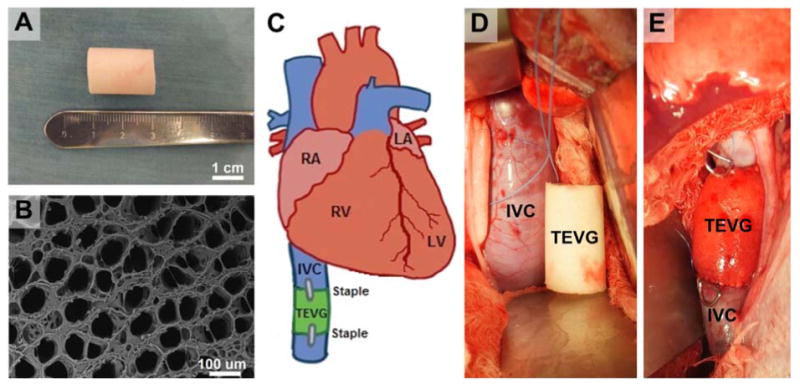

Scaffolds were constructed using a polyglycolic acid non-woven sheet coated with a 50:50 copolymer solution of poly (L-lactic acid-co-ε-caprolactone) (Gunze Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) as previously described.2 Prior to seeding, all grafts had a measured luminal diameter of 12 mm, wall thickness of 1.5 mm, and length of 20 mm (Fig. 1A). Graft porosity was examined by scanning electron microscopy (Model XL-30, FEI Company, Hillsboro, Oregon).

Figure 1.

Graft scaffold (A) and scanning electron micrograph (B) of polymer scaffold prior to surgical implantation. C) Schematic representation of surgical implantation of inferior vena cava interposition graft. Intra-operative photograph prior to (D) and immediately following (E) surgical implantation of an unseeded scaffold. Staples denote proximal and distal anastomoses.

Bone marrow-derived cell isolation

Autologous BM-MNCs were isolated from the iliac crest or femoral head of three juvenile Dover lambs into a heparinized syringe (100 U/mL), diluted 1:4 in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and passed through a 100 μm filter to remove fat and bone fragments. Bone marrow/PBS solution was added to Histopaque-1077 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for density centrifugation at 1500 rpm for 30 minutes. The BM-MNCs were isolated and subsequently washed with PBS and centrifuged (1500 rpm for 10 min) two additional times. This cell isolation procedure was performed for each of the three lambs that were implanted with cell-seeded scaffolds.

Scaffold seeding

Scaffolds were added to a sterile vacuum seeding setup as previously described.18 A pressure of 50 mm Hg was applied to the system thereby vacuum seeding the BM-MNCs onto the scaffolds. Following seeding, the scaffolds were placed in autologous serum and incubated for 24 hours (37°C, 5% CO2, 95% relative humidity, 760 torr). A sample of each graft was stained with Lee's methylene blue on glycol methacrylate-fixed tissue to quantify the number of attached cells.

Graft implantation

TEVGs were implanted as inferior vena cava (IVC) interposition grafts (3 seeded scaffolds; 2 unseeded scaffolds) in five juvenile Dover lambs (implantation weight, 22.4 ± 2.3 kg). Lambs were sedated with intramuscular acepromazine (0.05 mg/kg), followed by intravenous diazepam (0.2 mg/kg) and ketamine (2.75 mg/kg). Anesthesia was maintained throughout surgery with 1-5% isofluorane and intravenous propofol (25 ug/kg/min). Peri-operative cefazolin (22 mg/kg) was administered. A right thoracotomy was performed through the seventh intercostal space. Following isolation of the IVC and dissection of the phrenic nerve, heparin (100 IU/kg) was administered intravenously. The IVC was then clamped for 5 minutes and unclamped for 2 minutes – this process was repeated three times for adequate conditioning. Next, a 2 cm TEVG was anastomosed (proximally, then distally) using a running monofilament 5.0 suture. Radio-opaque markers were placed at the anastomoses (Fig. 1E). Fibrin sealant (Tisseal, Baxter Pharmaceuticals) was used for hemostasis. A marcaine nerve block was given for intercostal nerves 5-9. A layered closure was performed and chest tube was removed in the operating room. Post-operatively, animals were treated with fentanyl patches and banamine for analgesia. No post-operative anti-platelets or anti-coagulants were given. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Yale University approved the use of animals and all procedures. All animals received humane care in compliance with the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” published by the National Institutes of Health, the Animal Welfare Act, and Animal Welfare Regulations.

CT angiography imaging and analysis

In vivo 64-slice X-ray CT angiography with iodinated contrast (350 mgI/ml, Omnipaque, GE Healthcare) was performed (Discovery NM-CT 570c, GE Healthcare) in lambs at 2 and 6 months following TEVG implantation to assess graft luminal and longitudinal growth.

Following sedation, animals were intubated and mechanically ventilated (Venturi, Cardiopulmonary Incorporated) with 35% oxygen, 65% nitrous oxide, and 1-3% isoflurane. Blood pressure, oxygen saturation, and an electrocardiogram signal were continuously monitored during each imaging session (IntelliVue MP50, Philips). Peripheral vein access was established and a 5F polyethylene catheter was placed for the administration of fluids, CT contrast agent, and radioisotope. Prior to imaging, all animals were fasted overnight and given an intravenous 500 cc bolus of normal saline to attain euvolemia. CT images were acquired at a slice thickness of 0.625 mm, at 300 mA and 120 kVp. Intravenous contrast injections were performed with a power injector (Stellant D, MEDRAD) at a constant rate of 3 cc/sec and total volume of 30 cc, followed by a 20 cc saline flush at 3 cc/sec. TEVG luminal volume and length were quantified using commercially available software (Advanced Workstation v4.4, GE Healthcare). Measurement of TEVG length was standardized by selecting the mid-point of each marker that was attached to the distal and proximal anastomoses. Stenosis was defined as a decrease in luminal diameter that was greater than 50% of initial diameter at the time of implantation.

In vivo hybrid SPECT/CT imaging

In vivo single isotope imaging was performed 6 months after IVC graft implantation for qualitative assessment of MMP activity using hybrid SPECT/CT with 99mTc-RP805 (Lantheus Medical Imaging, Inc.). 99mTc-RP805 is a broad-spectrum MMP-targeted compound that binds to the activated exposed catalytic domain of MMPs -2, -3, -7, -9, -12, and -13. Previous work in our lab has demonstrated various binding characteristics associated with this radiotracer for each of these MMPs.16 SPECT imaging was performed 60 minutes following intravenous injection of radiotracer at rest (1468.9 ± 159.1 MBq). All images were acquired with a dedicated cardiac SPECT camera (Discovery 570c, GE Healthcare) at a slice thickness of 4 mm. Immediately following each SPECT acquisition, non-contrast CT images were acquired and reconstructed with a filtered back projection to create CT attenuation maps. The SPECT images were reconstructed with a maximum a posteriori (MAP) algorithm at 80 iterations using commercially available software (Xeleris, GE Healthcare). Smoothing parameters were selected as β=0.2 and α=0.41. Images were reconstructed with a dimension of 150 × 150 × 150 voxels to alleviate artifacts that may be caused by truncated projections from the limited field-of-view (FOV) associated with this SPECT system.19 The attenuation map was incorporated into the reconstruction for attenuation correction. No post-filtering was applied in order to preserve the image resolution.

Ex vivo SPECT/CT imaging and quantification

Ex vivo 99mTc-RP805 SPECT/CT imaging was performed immediately following graft explantation. Grafts were placed on a conical tube to allow for circumferential visualization and differentiation of MMP activity in the graft wall. Immediately following each SPECT acquisition, non-contrast CT images were acquired as previously described above. SPECT images were reconstructed at a slice thickness of 2 mm using the same reconstruction configuration as specified above. Total counts were recorded on axial slices of the explanted graft and adjacent native IVC using the vendor's software (Xeleris, GE Healthcare) and normalized to cross-sectional area (CSA) of tissue for each axial slice. Retention of 99mTc-RP805 within graft tissue and native IVC was expressed as a ratio (TEVG / native IVC).

Histological assessment

Following surgical explantation and imaging, portions of TEVG tissue and native IVC were fixed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin. Five μm sections, sampled from the midsection of the TEVG, were stained using standardized techniques for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Masson's Trichrome (collagen), Alcian blue (glycosaminoglycans), and Elastica van Gieson (elastin).

Biochemical assessment

Collagen content was determined for TEVG tissue and native IVC in triplicate using a Sircol soluble collagen assay (Biocolor Assays, Inc) according to manufacturer's instructions. Glycosaminoglycan content was determined in triplicate using a Blyscan™ colorimetric assay (Biocolor Assays, Inc) in a similar fashion.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using commercially available software (GraphPad Prism v6.00 for Mac OS X, GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Paired t-tests were used to evaluate serial changes in luminal volume and graft length (using CT angiography) in seeded grafts. Unpaired t-tests were used to evaluate differences in CT angiography, ex vivo 99mTc-RP805 SPECT/CT, and biochemical results between seeded and unseeded grafts. Statistical significance for all analyses was set at p < 0.05. Values are expressed as means ± SD unless stated otherwise. A biostatistician at The Research Institute at Nationwide Children's Hospital reviewed all statistical analyses for proper methodology and interpretation.

Results

Graft scaffold and cell seeding

The scaffold matrix was approximately 80% porous, with pore diameters ranging from 20 to 100 μm (Fig. 1B). Isolation and seeding of BM-MNCs onto graft scaffolds (n=3) resulted in the attachment of 3,189 ± 2,337 cells/mm2 prior to surgical implantation. All 5 lambs survived through the duration of the 6-month study without any graft-related complications.

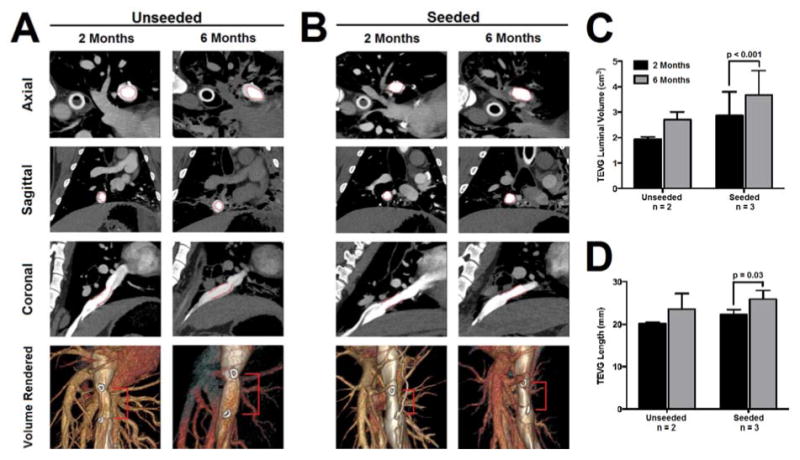

CT angiography

In vivo CT angiography demonstrated graft patency in all lambs at 2 and 6 months following implantation (Fig. 2). Seeded grafts had a significantly higher luminal volume at 6 months compared to 2 months following implantation (2 months, 2.9 ± 0.9 cm3; 6 months, 3.7 ± 0.9 cm3; p<0.001) and demonstrated significant longitudinal growth from 2 to 6 months (2 months, 22.3 ± 1.2 mm; 6 months, 26.0 ± 2.0 mm; p=0.03).

Figure 2.

In vivo CT angiography at 2 and 6 months following implantation of an unseeded (A) and seeded (B) scaffold demonstrates graft patency (lumen indicated by red markers). Serial quantification of CT angiography revealed significant increases in TEVG luminal volume (C) and length (D) in seeded grafts.

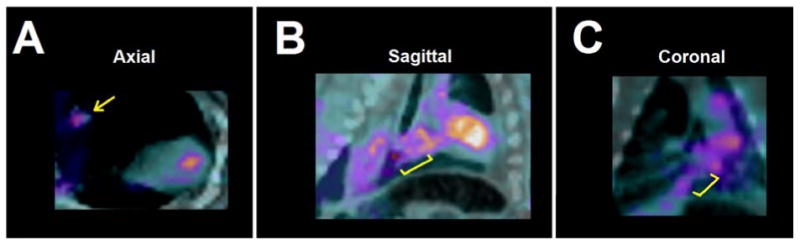

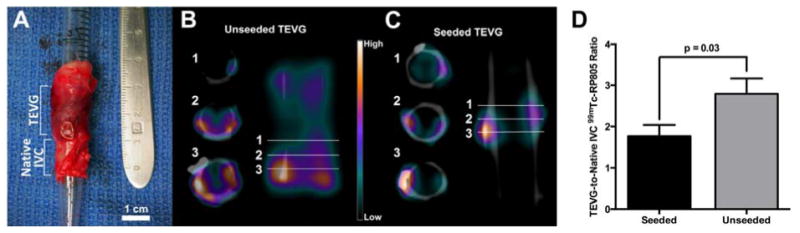

In vivo and ex vivo 99mTc-RP805 SPECT/CT imaging

In vivo SPECT/CT imaging demonstrated an increase in 99mTc-RP805 activity within the region of the IVC graft (Fig. 3). Quantitative analysis of ex vivo SPECT/CT imaging demonstrated higher 99mTc-RP805 activity within the TEVG compared to the adjacent native IVC and significantly higher relative tracer uptake in unseeded vs. seeded grafts (TEVG/native vessel, unseeded: 2.8 ± 0.4, seeded: 1.8 ± 0.3; p=0.03; Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Increased 99mTc-RP805 activity is observed in the blood pool and the region of IVC graft implantation (indicated by yellow marker) in axial (A), sagittal (B), and coronal (C) views.

Figure 4.

Ex vivo SPECT/CT imaging and quantification. A) Representative sample of explanted TEVG and native IVC tissue prior to ex vivo SPECT/CT imaging. SPECT/CT imaging demonstrated heterogeneous uptake of 99mTc-RP805 in the graft, as illustrated by representative cross sections of the vessel wall in both unseeded (B) and seeded (C) grafts. Significantly higher MMP activity is seen in unseeded compared to seeded grafts (D).

Histology

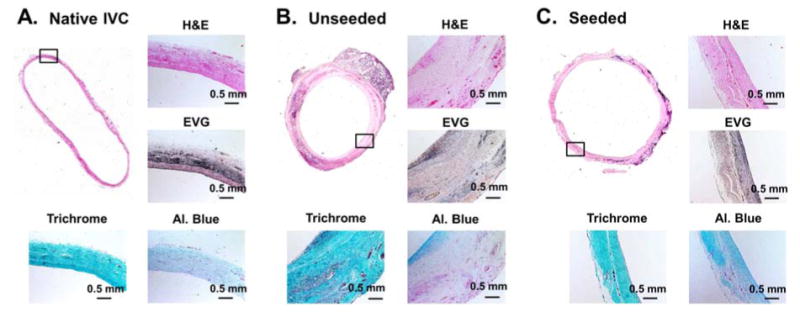

Histology was performed on TEVG and native IVC tissue at 6 months following implantation to assess neotissue cellularity and the presence of collagen, glycosaminoglycans, and elastic fiber formation (Fig. 5). Tissue staining with Masson's trichrome and H&E demonstrated that the polymer had degraded by 6 months and was subsequently replaced by a collagen-dominated neotissue. Alcian blue staining suggested increased glycosaminoglycan content in the seeded graft neotissues compared to the unseeded and indicated that glycosaminoglycans were inhomogeneously distributed in the unseeded grafts (Fig. 5B). Elastica-Van Gieson demonstrates mild, but comparable elastic fiber formation between seeded and unseeded groups with both remaining inferior to the native IVC (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

H&E, Elastica-Van Gieson, Masson's trichrome, and Alcian blue staining of native IVC (A), unseeded TEVG at 6 months (B), and seeded TEVGs at 6 months (C). Implanted scaffolds completely degraded over 6 months and were replaced with collagen-dominated neotissue (B & C). Elastic fiber formation was comparable in TEVGs, but appeared suboptimal compared to native IVC (A). Alcian blue staining demonstrated higher amount of glycosaminoglycans in the seeded compared to unseeded TEVG.

Biochemical analysis

No significant differences were observed in collagen content within seeded (n=3: 65.2 ± 47.8 ug/mg) and unseeded TEVGs (n=2: 110.0 ± 11.8 ug/mg). Glycosaminoglycan content was significantly higher in the seeded TEVG group (n=3, 6.5 ± 0.3 ug/mg) when compared to the unseeded TEVG group (n=2, 4.1 ± 0.8 ug/mg; p=0.01).

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrate the feasibility of targeted SPECT/CT imaging for the quantitative assessment of MMP activity within surgically implanted IVC interposition grafts with complementary serial evaluation of graft morphological changes using in vivo CT angiography. We utilized a previously validated lamb model of IVC graft implantation 5 and the density centrifugation technique for isolation of BM-MNCs met the same criteria for scaffold cell attachment that is implemented in our ongoing clinical trial.3 All grafts were patent at 2 and 6 months following implantation, with seeded grafts demonstrating significant luminal and longitudinal growth (Fig. 2). Significantly higher activity of MMP activity was found in grafts compared to native IVCs at 6 months post-implantation, with significantly higher MMP activity in unseeded vs. seeded grafts (Fig. 4). The elevated MMP activity in grafts may be related to ongoing neotissue formation and persist at a higher level in unseeded graft scaffolds at 6 months. The combined imaging techniques of CT angiography and hybrid SPECT/CT offer a potentially novel approach for noninvasive, serial evaluation of ongoing graft remodeling and neotissue formation in tissue-engineered grafts.

Previous studies from our laboratory have indicated that neotissue formation occurs via an early inflammatory-mediated phase of vascular remodeling as the polymeric scaffold degrades.20–22 The balance of the production and removal of structurally significant ECM constituents (e.g., collagen, elastin, glycosaminoglycans) and the degradation of the implanted graft scaffold dictate vascular neotissue evolution. MMPs play an important role in this balance. Therefore, monitoring of MMP activity may provide valuable information related to the status of neotissue development in the setting of TEVG implantation. Two previous studies have quantified MMP activity within TEVGs implanted as IVC interposition grafts; however, these studies required histologic evaluation of explanted neotissue.6,7 In the present study, we sought to evaluate the feasibility of noninvasive assessment of MMP activity in a clinically relevant large animal model of TEVG implantation. We observed elevated MMP activity within the region of TEVG implantation at 6 months following implantation using in vivo SPECT/CT imaging (Fig. 3) of a broad-spectrum MMP-targeted radiotracer (99mTc-RP805). Although increased radiotracer activity was observed with in vivo SPECT/CT imaging, it is clear that much of this activity still remains in the blood pool during the time of image acquisition at one hour following radiotracer injection, complicating quantification of MMP activity in the graft at this early time point following radiotracer injection (Fig. 3). Improved in vivo localization and quantification of 99mTc-RP805 in the vascular wall may be achieved in future studies with the incorporation of a later image acquisition time (2-4 hrs post-radiotracer injection), as indicated by previous attempts at SPECT/CT vascular imaging of MMP activity.11,13 Additionally, in vivo SPECT/CT imaging was not performed with cardiac gating, thus limiting the ability to quantify local MMP activity within the region of TEVG implantation.

Although limitations existed with in vivo SPECT/CT imaging that prevented quantification of TEVG radiotracer uptake, MMP activity was quantified in TEVGs and native IVCs using ex vivo SPECT/CT imaging. Significant differences in MMP activity were found in unseeded compared to seeded TEVGs at 6 months (Fig. 4). Previous investigation in our lab has demonstrated the importance of cell seeding in the TEVG remodeling process and has identified higher rates of stenosis in unseeded vs. seeded scaffolds;23 however, no evidence of aneurysm or stenosis was apparent in unseeded or seeded scaffolds in the present study. Serial in vivo CT angiography demonstrated significant luminal and longitudinal growth in seeded scaffolds from 2 to 6 months (Fig. 2). This noted growth of TEVGs in the present study is consistent with previously reported results from our lab that identified serial changes in TEVG growth using MR angiography in juvenile lambs.5 The patterns of longitudinal growth measured by CT angiography suggest that implanted scaffolds have biodegraded by 6 months and allowed for growth of newly formed neotisse within juvenile lambs that nearly doubled in weight during the 6 month duration of study (implantation weight, 22.4 ± 2.3 kg; 6 month weight, 42.7 ± 4.3 kg).

Histologic evaluation of TEVG tissue at 6 months post-implantation confirmed graft scaffold degradation and subsequent replacement by a collagen-dominant neotissue (Fig. 5). While no significant differences in collagen content were identified by biochemical analysis, lower collagen content and increased MMP activation in TEVGs compared to native IVC suggests that ECM remodeling continues at 6 months post-implantation and indicates that the neotissue is still actively remodeling. Elastica van Gieson staining demonstrated mild, but comparable elastic fiber formation between seeded and unseeded neotissue (Fig. 5), while both TEVG groups remained inferior to native IVC tissue. These histologic observations indicate continued ECM remodeling that corresponds with SPECT/CT imaging of increased MMP activity at 6 months following TEVG implantation. Improved in vivo SPECT/CT imaging for the noninvasive assessment of MMP activity should greatly facilitate our understanding of the time course associated with neotissue formation and enhance the application of tissue engineering within the cardiovascular system.

Limitations

A small number of animals were used in the present study. While these numbers were sufficient for a feasibility study, future investigations with a greater number of implantations are necessary to increase statistical power and evaluate the full potential for noninvasive imaging of MMPs in vascular grafts. Additionally, in vivo SPECT imaging was not optimized for localization and quantification of MMP activity. SPECT imaging protocols incorporating cardiac gating and later acquisition times following radiotracer injection should provide improved localization of radiotracer activity and allow for noninvasive in vivo quantification of MMP activity within TEVGs. Although this study evaluated the feasibility of noninvasive imaging of MMP activity for the detection of ongoing TEVG remodeling, immunohistochemistry was not performed. Such analysis may have provided further insight into the presence of specific MMPs within neotissue at 6 months following implantation. Future investigations targeted at the TEVG remodeling process may greatly benefit from correlative immunohistochemistry findings to validate noninvasive molecular imaging.

Conclusions

The present study demonstrates the feasibility of targeted SPECT/CT imaging of MMP activity within TEVGs implanted in a growing large animal model. The ability to noninvasively assess MMP activity within TEVGs in vivo may provide a unique opportunity to evaluate the underlying mechanisms regulating the transition from TEVG to neovessel and may assist with improved translation of tissue engineering into clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Christi Hawley for technical assistance with animal care and Yongjie Miao for consultation related to statistical analyses. The authors would also like to thank Lantheus Medical Imaging, Inc. for supplying the RP805 compound used for SPECT imaging.

Sources of Funding: This work was supported in part by NIH grant T32 HL098069 (AJ Sinusas) and the OHSE Committee (Dept. of Surgery, Yale Univ. School of Medicine; MW Maxfield).

Conflicts of Interest: Drs. Breuer and Shinoka received financial support from the Gunze Corporation. RP805 compound was supplied to Dr. Sinusas from Lantheus Medical Imaging, Inc.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Shinoka T, Ikada Y, Imai Y. Transplantation of a tissue-engineered pulmonary artery. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(7):532–533. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102153440717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hibino N, McGillicuddy E, Matsumura G, et al. Late-term results of tissue-engineered vascular grafts in humans. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139(2):431–436. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vogel G. Mending the youngest hearts. Science (80-) 2011;333(6046):1088–1089. doi: 10.1126/science.333.6046.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shinoka T, Matsumura G, Hibino N, et al. Midterm clinical result of tissue-engineered vascular autografts seeded with autologous bone marrow cells. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129(6):1330–1338. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brennan MP, Dardik A, Hibino N, et al. Tissue-engineered vascular grafts demonstrate evidence of growth and development when implanted in a juvenile animal model. Ann Surg. 2008;248(3):370–377. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318184dcbd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naito Y, Williams-Fritze M, Duncan DR, et al. Characterization of the natural history of extracellular matrix production in tissue-engineered vascular grafts during neovessel formation. Cells Tissues Organs. 2011;195(1-2):60–72. doi: 10.1159/000331405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cummings I, George S, Kelm J, et al. Tissue-engineered vascular graft remodeling in a growing lamb model: expression of matrix metalloproteinases. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;41(4):167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2011.02.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lancelot E, Amirbekian V, Brigger I, et al. Evaluation of matrix metalloproteinases in atherosclerosis using a novel noninvasive imaging approach. Arter Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:425–432. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.149666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hyafil F, Vucic E, Cornily JC, et al. Monitoring arterial wall remodelling in atherosclerotic rabbits with a magnetic resonance imaging contrast agent binding to matrix metalloproteinases. Eur Hear J. 2011;32:1561–1571. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haider N, Hartung D, Fujimoto S, et al. Dual molecular imaging for targeting metalloproteinase activity and apoptosis in atherosclerosis: molecular imaging facilitates understanding of pathogenesis. J Nucl Cardiol. 2009;16:753–762. doi: 10.1007/s12350-009-9107-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujimoto S, Hartung D, Oshima S, et al. Molecular imaging of matrix metalloproteinase in atherosclerotic lesions: resolution with dietary modification and statin therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(23):1847–1857. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Razavian M, Tavakoli S, Zhang J, et al. Atherosclerosis plaque heterogeneity and response to therapy detected by in vivo molecular imaging of matrix metalloproteinase activation. J Nucl Med. 2011;52(11):1795–1802. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.092379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang J, Nie L, Razavian M, et al. Molecular imaging of activated matrix metalloproteinases in vascular remodeling. Circulation. 2008;118:1953–1960. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.789743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tavakoli S, Razavian M, Zhang J, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase activation predicts amelioration of remodeling after dietary modification in injured arteries. Arter Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31(1):102–109. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.216036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sahul ZH, Mukherjee R, Song J, et al. Targeted imaging of the spatial and temporal variation of matrix metalloproteinase activity in a procine model of postinfarct remodeling: relationship to myocardial dysfunction. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4(4):381–391. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.110.961854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Su H, Spinale FG, Dobrucki LW, et al. Noninvasive targeted imaging of matrix metalloproteinase activation in a murine model of postinfarction remodeling. Circulation. 2005;112(20):3157–3167. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.583021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hjortnaes J, Gottlieb D, Figueiredo JL, et al. Intravital molecular imaging of small-diameter tissue-engineered vascular grafts in mice: a feasibility study. Tissue Eng. 2010;16(4):597–607. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2009.0466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Udelsman B, Hibino N, Villalona G, et al. Development of an operator-independent method for seeding tissue-engineered vascular grafts. Tissue Eng Part C. 2011;17(7):731–736. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2010.0581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan C, Dey J, Sinusas AJ, Liu C. Improved image reconstruction for dedicated cardiac SPECT with truncated projections. J Nucl Med. 2012;53(4):666. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roh JD, Sawh-Martinez R, Brennan MP, et al. Tissue-engineered vascular grafts transform into mature blood vessels via an inflammation-mediated process of vascular remodeling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(10):4669–4674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911465107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hibino N, Villalona G, Pietris N, et al. Tissue-engineered vascular grafts form neovessels that arise from regeneration of the adjacent blood vessel. FASEB J. 2011;25(8):2731–2739. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-182246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roh JD, Sawh-Martinez R, Brennan MP, et al. Small-diameter biodegradable scaffolds for functional vascular tissue engineering in the mouse model. Biomaterials. 2008;29(10):1454–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.11.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hibino N, Yi T, Duncan DR, et al. A critical role for macrophages in neovessel formation and the development of stenosis in tissue-engineered vascular grafts. FASEB J. 2011;25(12):4253–4263. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-186585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]