Abstract

Background and purpose

Femoral lengthening may result in decrease in knee range of motion (ROM) and quadriceps and hamstring muscle weakness. We evaluated preoperative and postoperative knee ROM, hamstring muscle strength, and quadriceps muscle strength in a diverse group of patients undergoing femoral lengthening. We hypothesized that lengthening would not result in a significant change in knee ROM or muscle strength.

Patients and methods

This prospective study of 48 patients (mean age 27 (9–60) years) compared ROM and muscle strength before and after femoral lengthening. Patient age, amount of lengthening, percent lengthening, level of osteotomy, fixation time, and method of lengthening were also evaluated regarding knee ROM and strength. The average length of follow-up was 2.9 (2.0–4.7) years.

Results

Mean amount of lengthening was 5.2 (2.4–11.0) cm. The difference between preoperative and final knee flexion ROM was 2° for the overall group. Congenital shortening cases lost an average of 5% or 6° of terminal knee flexion, developmental cases lost an average of 3% or 4°, and posttraumatic cases regained all motion. The difference in quadriceps strength at 45° preoperatively and after lengthening was not statistically or clinically significant (2.7 Nm; p = 0.06). Age, amount of lengthening, percent lengthening, osteotomy level, fixation time, and lengthening method had no statistically significant influence on knee ROM or quadriceps strength at final follow-up.

Interpretation

Most variables had no effect on ROM or strength, and higher age did not appear to be a limiting factor for femoral lengthening. Patients with congenital causes were most affected in terms of knee flexion.

Modern advances in limb lengthening techniques and increased experience have led to more reliable results. Despite improvements, complications such as joint stiffness, muscle weakness, joint dislocations, and nerve injuries have been reported (Paley 1990). Knee range of motion (ROM) has been reported to decrease during lengthening (Barker et al. 2001, Maffulli et al. 2001, Motmans and Lammens 2008). Several authors have reported that knees may remain stiff after lengthening (Hosalkar et al. 2003, Khakharia et al. 2009, Martin et al. 2013), while others have reported that patients eventually reach preoperative knee ROM values (Barker et al. 2001, Maffulli et al. 2001, Acharya and Guichet 2006, Motmans and Lammens 2008). Femoral lengthening is considered to be more prone to complications such as loss of knee ROM than is tibial lengthening (Herzenberg et al. 1994, Maffulli et al. 2001, Zarzycki et al. 2002).

Another common complication associated with femoral lengthening is quadriceps muscle weakness. Causes of this weakness are thought to be disuse and neurogenic factors (Kaljumäe et al. 1995, Oey et al. 1999). A review of the literature revealed only a few previous studies that examined the effect of femoral lengthening on quadriceps muscle strength (Holm et al. 1995, Maffulli and Fixsen 1995, Yasui et al. 1997). Those studies measured strength before surgery and after frame removal. Maffulli and Fixsen (1995) showed that quadriceps strength was compromised for a prolonged period after femoral lengthening for congenitally short femora. Yasui et al. (1997) measured pre- and post-lengthening strength in 35 patients with achondroplasia. They showed that postoperative quadriceps strength was equal to or greater than preoperative quadriceps strength in the majority of cases. Holm et al. (1995) prospectively assessed thigh muscle function with at least 2-year follow-up in 9 patients who underwent bilateral femoral lengthening. They found only small changes in muscle strength postoperatively, and that patients had normal ROM at final follow-up.

The purpose of the present study was to evaluate preoperative and postoperative knee ROM, hamstring muscle strength, and quadriceps muscle strength in a diverse group of patients undergoing femoral lengthening. We hypothesized that lengthening would not result in a significant change in knee ROM or muscle strength. Patient age, amount of lengthening, percent lengthening, level of osteotomy, fixation time, and method of lengthening (conventional Ilizarov method vs. lengthening-over-nail (LON) method) were also evaluated with respect to knee ROM and strength.

Patients and methods

119 consecutive patients were enrolled in the study between March 1996 and December 2002. Of these 119 patients, 65 were excluded because they required additional surgical procedures (42 patients) or they had inadequate follow-up visits to obtain strength and ROM data (23 patients). To have statistically independent observations only, 6 patients who underwent bilateral femoral lengthening were also excluded. The remaining 48 patients were included in the study.

Of the 48 femora that were lengthened, the causes of limb shortening were congenital in 14 femora, developmental in 14, and posttraumatic in 20. Mean patient age at the time of operation was 27 (9–60) years. 16 patients were less than 16 years of age, 14 were between the ages of 16 and 30 years, and 18 were 30 years or older.

There were 3 levels of osteotomies: 16 femora underwent osteotomy at the proximal level, 12 at the middle level, and 19 at the distal level, with one femur having a combined osteotomy level of middle and distal.

27 of the 48 patients underwent either soft-tissue release or injection of BOTOX into the rectus femoris or hamstring muscle. 14 of them underwent intramuscular lengthening of the rectus femoris, 7 underwent release of the distal fascia lata, 14 underwent proximal adductor lengthening, and 6 underwent hamstring lengthening. In 4 of the 48 patients, we also injected BOTOX into the thigh muscles (quadriceps and hamstrings). The decision to inject BOTOX or to perform soft-tissue releases at the time of fixator application was based on prone knee flexion for measurement of the rectus femoris tightness and range of popliteal angle for measurement of hamstring tightness. In 3 patients, delayed soft-tissue lengthenings were performed. These surgical interventions were aimed at treating substantial loss of knee motion during lengthening, knee flexion less than 30°, and development of knee flexion contracture greater than 30°.

Limb-length discrepancies were measured on full-length radiographs obtained with erect limbs and with the use of appropriate lifts. All radiographic measurements were normalized for magnification by using magnification markers.

2 types of lengthening were performed: 21 femoral lengthenings were performed with the conventional Ilizarov method (Smith and Nephew Orthopedics, Memphis, TN), and 27 femoral lengthenings were performed using the LON (Russell-Taylor Delta; Smith and Nephew Orthopedics) femoral nail procedure with intramedullary nails (Paley el al. 1997). There were no criteria for choosing to treat with either the conventional Ilizarov method or LON. The traditionally preferred method for lengthening was Ilizarov until the advent of the LON method, provided there were no specific contraindications for this method. In the conventional Ilizarov group, we used a distal pin pattern that minimized transfixation of the muscles (Paley 2005). In the LON group, 25 femora were lengthened with the use of a monolateral external fixator (Orthofix, Lewisville, TX) and 2 with the use of a circular external fixator. 16 patients who had unstable knees had the femoral fixation hinged at the knee and extended to the tibia to control knee joint position during lengthening (Stanitski et al. 1996, Paley 2005). This technique has achieved superior results for knee ROM and a reduction in articular cartilage damage (Stanitski et al. 1996). For patients in the LON group, the external fixator was applied to the femur with simultaneous insertion of an intramedullary nail and the nail was locked proximally. At the end of lengthening, the nail was locked distally and the external fixator was then removed.

We used a KinCom isokinetic dynamometer (Chattecx Corp., Chattanooga, TN) for measurement of pre- and postoperative muscle strength. Measurements with this dynamometer has been found to be accurate (Mayhew et al. 1994, Dillon et al. 1998), reproducible (Boiteau et al. 1995, Dillon et al. 1998), and reliable (Boiteau et al. 1995, Chester et al. 2003). We used a standard long-arm goniometer to measure knee ROM (Stanitski et al. 1996). All measurements were obtained with the hip joint in a neutral position to eliminate the effect of the hamstring and rectus femoris muscles on knee ROM (Greene and Heckman 1993). All measurements of strength and of ROM were obtained by AB. JEH and DP performed all the surgical procedures, and physiotherapists obtained the radiographic measurements of the preoperative limb-length differences and the postoperative amounts and percentages of lengthening.

We measured isometric strength of the quadriceps and hamstring muscles at 90° and at 45° of knee flexion. We found that many patients experienced anterior knee pain during isokinetic exercises at 60° per second, while isometric exercises were pain-free after distraction was completed. Due to this, we chose isometric testing to reduce bias caused by anterior knee pain. The lever arm was attached just above the malleoli. The distance from the knee joint center to the center of the lever arm was measured. The same distance was used to place the lever arm when obtaining postoperative strength measurements. This was critical, because the transducer of the isokinetic dynamometer is in the pad that attaches just above the malleoli. Because of this, a change in lever arm would significantly alter the force or torque measured. We were meticulous in measuring, documenting, and repeating the test with the same measurements used preoperatively. Patients performed 3 maximal isometric contractions at 90° and at 45° of knee flexion. This was done for both extension and flexion to measure the isometric strength of the quadriceps and hamstrings. The 3 measurements of peak torque in flexion and extension were averaged. Isometric strength measurements were obtained preoperatively, and isometric postoperative strength measurements were obtained at least twice during the rehabilitation phase after fixator removal. At the second postoperative examination, if the strength was found to be greater than the preoperative strength, no further measurements were obtained. For some patients, up to 4 measurements were obtained during the follow-up period.

When obtaining knee ROM measurements, particular care was taken to align the goniometer to the femur by palpating the greater trochanter and then aligning the goniometer close to the femur. In patients with knee joint hinges, measurements were obtained with the goniometer centered at the hinge, with the distal arm of the goniometer parallel to the tibia and the proximal arm parallel to the femur. Knee ROM measurements were obtained throughout the lengthening and consolidation phases, at the time of fixator removal, and at follow-up. We used discrete endpoints for analysis of knee ROM: (1) preoperative, (2) at the end of lengthening, (3) at the end of consolidation or at fixator removal, and (4) after fixator removal at final follow-up. All patients underwent at least 4 follow-up examinations after fixator removal (range: 4–7). For patients undergoing LON, the end of lengthening was the time of fixator removal.

Physiotherapy protocol

As part of their postoperative care, all patients received physiotherapy 5 times a week during the lengthening process. For patients younger than 16 years and for patients with bulky frames, we recommended an additional session of physiotherapy that consisted of hydrotherapy, for the purpose of neutralizing the effect of gravity during active motion, thereby promoting active ROM. We instructed the patients and therapists to focus on soft-tissue flexibility and joint mobilization during the lengthening process. All patients were encouraged to sleep with the knee in extension. For patients with a quadriceps active extension lag greater than 20°, electrical muscle stimulation was used to augment quadriceps contraction during physiotherapy. During the lengthening phase, patients with the Ilizarov external fixator achieved weight bearing as tolerated with the aid of 2 crutches. Patients in the LON group were permitted touch-down weight bearing until lengthening was complete. During the lengthening phase, if knee ROM less than 40° was observed, the rate of lengthening was reduced. During the consolidation phase, patients in the Ilizarov group progressively increased weight bearing as tolerated and reduced the need for bilateral crutches to the use of a single crutch or cane in the opposite hand. During the consolidation phase, patients in the LON group were permitted increased weight bearing based on the results of anteroposterior and lateral view radiographs, which were reviewed by the surgeons.

The goal of physiotherapy during the consolidation phase was to maximize knee and hip ROM. The frequency of physiotherapy during the consolidation phase was 2 or 3 times per week. After frame removal, physiotherapy was resumed, the intensity of joint mobilization was increased, and the soft-tissue flexibility regimen gradually progressed. The majority of patients received physiotherapy 3 times a week until joint ROM was normalized, or at least until preoperative measurements were obtained. After ROM was normalized, we encouraged our patients to continue to perform resistive exercises to improve quadriceps strength. All the patients were encouraged to perform an exercise program at home and to continue with health club-type activities for up to 2 years after fixator removal.

Statistics

Pre- and postoperative values were compared using a paired t-test, while differences in subgroup means were compared using Welch’s unequal variance t-test with p < 0.05 being considered significant. We performed ANOVA to assess differences in ROM and strength loss by etiology, while linear regression was used to determine the association between amount of lengthening and changes in both ROM and strength. Multivariable analysis using multiple linear regression was conducted in those instances in which univariate analysis showed statistically significant variables of interest. Multiple measurements were obtained for each test and then averaged.

Statistical analysis was conducted using R version 3.2.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Ethics and registration

Our institutional review board approved the protocol and study design (registration number 1538). The procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional review board and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

Results

The mean amount of lengthening was 5.2 (2.4 − 11) cm. The mean percent lengthening was 13% (5.0 − 33).

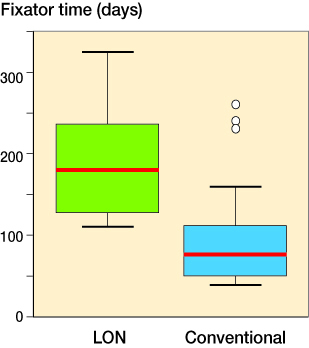

Knee flexion normalized in most patients within 4 months, but for some patients it took as long as 6 months. Mean duration of treatment with external fixation for the conventional method was 195 (110–324) days (SD 75). Mean duration of treatment with external fixation for the LON group was 97 (40–260) days (SD 62) (Figure 1). Patients in the LON group had the external fixator in place for less time than did patients in the conventional Ilizarov group (p < 0.001). This allowed the LON group to start physiotherapy much earlier and therefore to achieve recovery of knee ROM earlier than did patients who underwent conventional lengthening (p = 0.002).

Figure 1.

Mean duration of treatment with external fi xation for lengthening-over-nail (LON) technique vs. conventional Ilizarov external fi xation. The LON group had the external fi xator in place for signifi cantly less time than did patients in the conventional Ilizarov group (p < 0.001).

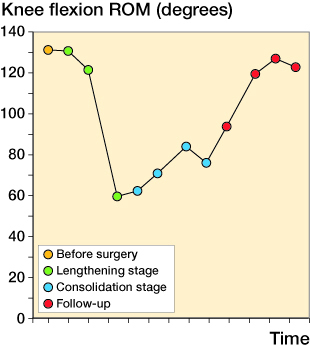

The difference between preoperative and final knee flexion ROM was not significant (p = 0.1) (mean loss was 1% (SD 9)). The majority of the patients had lost significant flexion ROM by the end of lengthening (p < 0.001) (Figure 2). Mean preoperative knee flexion was 126° (90 − 140), and mean knee flexion at the end of lengthening was less (55° (17 − 100)) (p < 0.001). At the end of consolidation, knee flexion improved by an average of 26° (12 − 40) to achieve a final average of 81° (32–120).

Figure 2.

Aggregate average knee fl exion range of motion (ROM) for the entire patient population during different stages of the lengthening process.

After treatment, knee extension ROM remained the same or improved in all limbs. Average preoperative knee extension was 0° in 83% of cases (40 limbs); 6 limbs had knee flexion contracture values between 5° and 10°, and 2 limbs had hyperextension of 5°. At the end of lengthening, average knee extension ROM was 6° (0–20). At the end of consolidation, average knee extension was 1° (0–15). No flexion contracture was measured. At final follow-up, 47 of the 48 limbs had 0° of knee extension (1 limb had 5°, which matched the preoperative value).

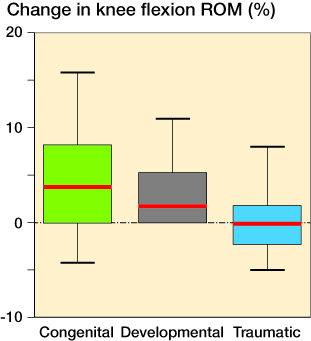

Using univariate analyses and ANOVA, we were unable to find any statistically significant factors associated with loss of knee flexion. Loss of knee flexion was not significantly influenced by sex (p = 0.5), age (p = 0.7), amount of lengthening (p = 0.4), percent of lengthening (p = 0.7), BOTOX injection (p = 0.3), muscle release (p = 0.9), fixation time (p = 0.9), type of lengthening (conventional Ilizarov method vs. LON method) (p = 0.2), and level of osteotomy (p = 0.4). The etiology of limb shortening approached statistical significance, with congenital and developmental etiologies having greater loss of knee flexion (p = 0.09) (Figure 3). In the LON group, there was no change in knee ROM (mean gain =0.07%, range: 21% loss to 37% gain). In the Ilizarov group, the mean loss of knee ROM was 3.4% (range: 11% loss to 13% gain).

Figure 3.

Change in knee fl exion range of motion when patients were categorized according to the cause of limb shortening (p = 0.09).

We measured the isometric strength (peak torque) of the quadriceps and hamstrings at 90° and at 45° of knee flexion. For statistical analysis, we averaged the values obtained at 90° and at 45°. Preoperative strength measurements showed that the short side was always also the weaker side. The averaged peak torque was 40–50% weaker for the quadriceps muscle and 15–20% weaker for the hamstrings for the affected side compared to the unaffected side. The difference between the short and long sides was significant (p < 0.001). The difference between preoperative quadriceps strength and postoperative strength measured at 45° was not significant (p = 0.06). Immediately after limb lengthening, quadriceps strength at 90° of flexion returned to within 5% of preoperative levels in 8 of the 48 lengthenings, increased to more than 5% of preoperative levels in 26 patients, and decreased by more than 5% compared to preoperative levels in 14 patients. The majority of patients required 11 months after fixator removal to regain strength. Sex (p = 0.7), amount of lengthening (p = 0.7), percent lengthening (p = 0.4), level of osteotomy (p = 0.2), fixation time (p = 0.9), and type of lengthening (p = 0.5) had no significant influence on loss of muscle strength at final follow-up.

Data for knee range of motion (ROM) and quadriceps muscle strength presented as the paired difference between the preoperative value and the value obtained after lengthening was completed (for muscle strength) or final follow-up value (for knee ROM) expressed as a mean (SD) and 95% CI

| Pre- operative value |

Value after completed lengthening |

Final follow-up value |

Mean difference |

95% CI |

p-value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knee flexion (°) | 126 (12) | – | 124 (12) | −2.4 | −5.3 to 0.5 | 0.01 |

| Knee extension (°) | −0.7 (2.9) | – | 0.1 (0.7) | 0.8 | 0.02 to 1.6 | 0.04 |

| Quadriceps strength (Nm) | ||||||

| in 45° flexion | 52 (20) | 54 (23) | – | 2.7 | −0.1 to 5.5 | 0.06 |

| in 90° flexion | 71 (24) | 75 (29) | – | 4.0 | 0.4 to 7.6 | 0.03 |

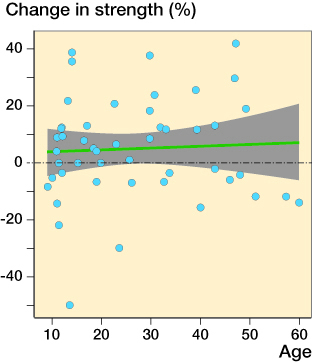

Regression analysis showed no relationship between age and loss of strength (p = 0.7) (Figure 4). When we divided the patients into 3 age groups (9–15.9 years, 16–29.9 years, and 30–60 years), there was no statistically significant difference in loss of quadriceps strength between groups. We also compared hamstring strength using analysis of variance of pre- and post-lengthening measurements. Hamstring strength was similar in all age groups before and after surgery (p = 0.9). Based on postoperative measurements in the 30- to 60-year age group, the hamstring muscle was significantly less affected by the method of lengthening than was the quadriceps muscle (p = 0.05). Mean loss of hamstring strength was 5.5% (range: −3.8 to 7.8) in the 30- to 60-year age group. The preoperative and postoperative change in hamstring strength was not clinically relevant in the other 2 age groups.

Figure 4.

Patient age compared to percent change in muscle strength postoperatively.

The Table summarizes the data for knee ROM and quadriceps muscle strength, presented as the paired difference between the preoperative value and the value obtained after lengthening was completed (for muscle strength) or final follow-up value (for knee ROM) expressed as mean and 95% CI. Although there was a statistically significant difference in the parameters measured, the mean difference was not clinically relevant.

Discussion

This study showed that knee motion and strength after femoral lengthening were not dependent on the amount of lengthening, percent lengthening, level of osteotomy, fixation time, or type of lengthening. However, recovery of knee flexion was achieved more quickly in patients who underwent LON than in patients who underwent conventional Ilizarov lengthening. This may have been because of the shorter length of time required for external fixation with LON; more aggressive rehabilitation could therefore occur earlier. The external fixation pins tether the muscles, so they inhibit motion. In addition, the etiology of limb shortening had the greatest effect on knee flexion. Taken as a whole, loss of knee flexion was not statistically significant. However, patients with congenital causes were most susceptible to joint stiffness. This is important information, affecting preoperative planning and prognosis of femoral lengthening for patients affected by congenital shortening.

We found no statistically significant changes from preoperative to postoperative measurements of quadriceps strength. In 34 of 48 femoral lengthenings, quadriceps strength increased or returned to preoperative measurements. There was no significant difference in change in muscle strength by age. This may be useful information for preoperative planning and prognosis in older patients.

We did not study joint cartilage thickness or long-term prognosis of the knees, so we cannot address the question of whether or not femoral lengthening causes degenerative changes, as described by Stanitski et al. (1996). Aggressive physiotherapy was given to all patients, and it remains unclear what effect this had on patient outcomes. To gain more insight into these trends, further study with a larger, more diverse group of participants is needed. The reproducibility of our results in other settings has not been proven. The quality of our outcomes may in large part be attributed to the careful and extensive physiotherapy regimen that we used for our patient population.

In summary, most variables had no effect on ROM or strength. Older patients did not appear to lose a significantly greater percentage of muscle strength or ROM after limb lengthening, which could be important for older patients hoping to undergo this procedure. However, patients with congenital and developmental causes were most affected in terms of knee flexion. Loss of knee flexion of approximately 5% in patients with congenital causes can be expected. It would be interesting to know whether the recent improvements in fully implantable lengthening nails would have any effect on strength or ROM results, particularly in patients with congenital conditions (Shabtai et al. 2014).

The authors were responsible for the study design (AB, AA, DP, JEH), data collection and analysis (AB, LS, AA, EW), writing of the manuscript (AB, LS, AA, EW), and performing substantial revisions of the manuscript (AB, LS, AA, DP, JEH, EW).

We thank Amanda E. Chase, MA, and Joy Marlowe, MA, for invaluable assistance with the manuscript.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Acharya A, Guichet J M.. Effect on knee motion of gradual intramedullary femoral lengthening. Acta Orthop Belg 2006; 72(5): 569–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker K L, Simpson A H, Lamb S E.. Loss of knee range of motion in leg lengthening. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2001; 31(5): 238–44; discussion 245-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boiteau M, Malouin F, Richards C L.. Use of a hand-held dynamometer and a Kin-Com dynamometer for evaluating spastic hypertonia in children: a reliability study. Phys Ther 1995; 75(9): 796–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chester R, Costa M L, Shepstone L, Donell S T.. Reliability of isokinetic dynamometry in assessing plantarflexion torque following Achilles tendon rupture. Foot Ankle Int 2003; 24(12): 909–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon R W, Tis L L, Johnson B F, Higbie E J.. The accuracy of velocity measures obtained on the KinCom 500H isokinetic dynamometer. Isokinetics and Exercise Sci 1998; 7(1): 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Greene W B, Heckman J D (eds). The Clinical Measurement of Joint Motion. Rosemont: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Herzenberg J E, Scheufele L L, Paley D, Bechtel R, Tepper S.. Knee range of motion in isolated femoral lengthening. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1994; 301: 49–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm I, Steen H, Ludvigsen P, Bjerkreim I.. Unchanged muscle function after bilateral femoral lengthening. A prospective study of 9 patients with a 2-year follow-up. Acta Orthop Scand 1995; 66(3): 258–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosalkar H S, Jones S, Chowdhury M, Hartley J, Hill R A.. Quadricepsplasty for knee stiffness after femoral lengthening in congenital short femur. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2003; 85(2): 261–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaljumäe U, Märtson A, Haviko T, Hänninen O.. The effect of lengthening of the femur on the extensors of the knee: an electromyographic study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1995; 77(2): 247–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khakharia S, Fragomen A T, Rozbruch S R.. Limited quadricepsplasty for contracture during femoral lengthening. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009; 467(11): 2911–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maffulli N, Fixsen J A.. Muscular strength after callotasis limb lengthening. J Pediatr Orthop 1995; 15(2): 212–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maffulli N, Nele U, Matarazzo L.. Changes in knee motion following femoral and tibial lengthening using the Ilizarov apparatus: a cohort study. J Orthop Sci 2001; 6(4): 333–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin B D, Cherkashin A M, Tulchin K, Samchukov M, Birch J G.. Treatment of femoral lengthening-related knee stiffness with a novel quadricepsplasty. J Pediatr Orthop 2013; 33(4): 446–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayhew T P, Rothstein J M, Finucane S D, Lamb R L.. Performance characteristics of the Kin-Com dynamometer. Phys Ther 1994; 74(11): 1047–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motmans R, Lammens J.. Knee mobility in femoral lengthening using Ilizarov’s method. Acta Orthop Belg 2008; 74(2): 184–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oey P L, Engelbert R H, van Roermond P M, Wieneke G H.. Temporary muscle weakness in the early phase of distraction during femoral lengthening: clinical and electromyographical observations. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol 1999; 39(4): 217–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paley D. Problems, obstacles, and complications of limb lengthening by the Ilizarov technique. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1990; 250: 81–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paley D. Principles of Deformity Correction. 1st ed, Corr. 3rd printing. Rev. ed. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 2005; p 47 and 359. [Google Scholar]

- Paley D, Herzenberg J E, Paremain G, Bhave A.. Femoral lengthening over an intramedullary nail: a matched-case comparison with Ilizarov femoral lengthening. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1997; 79(10): 1464–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabtai L, Specht S C, Standard S C, Herzenberg J E.. Internal lengthening device for congenital femoral deficiency and fibular hemimelia. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014; 472(12): 3860–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanitski D F, Rossman K, Torosian M.. The effect of femoral lengthening on knee articular cartilage: the role of apparatus extension across the joint. J Pediatr Orthop 1996; 16(2): 151–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasui N, Kawabata H, Kojimoto H, Ohno H, Matsuda S, Araki N, Shimomura Y, Ochi T.. Lengthening of the lower limbs in patients with achondroplasia and hypochondroplasia. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1997; 344: 298-306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarzycki D, Tesiorowski M, Zarzycka M, Kacki W, Jasiewicz B.. Long-term results of lower limb lengthening by physeal distraction. J Pediatr Orthop 2002; 22(3): 367–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]