Abstract

THEMIS, a recently identified T-lineage restricted protein, is the founding member of a large metazoan protein family. Gene inactivation studies have revealed a critical requirement for THEMIS during thymocyte positive selection, implicating THEMIS in signaling downstream of the T cell antigen receptor (TCR); but the mechanistic underpinnings of THEMIS’ function have remained elusive. A previous model posited that THEMIS prevents thymocytes from inappropriately crossing the positive/negative selection threshold by dampening TCR signaling. However, new data suggest an alternative model where THEMIS enhances TCR signaling, enabling thymocytes to reach the threshold for positive selection avoiding death by neglect. We review the data supporting each model and conclude that the preponderance of evidence favors an enhancing function for THEMIS in TCR signaling.

The THEMIS enigma

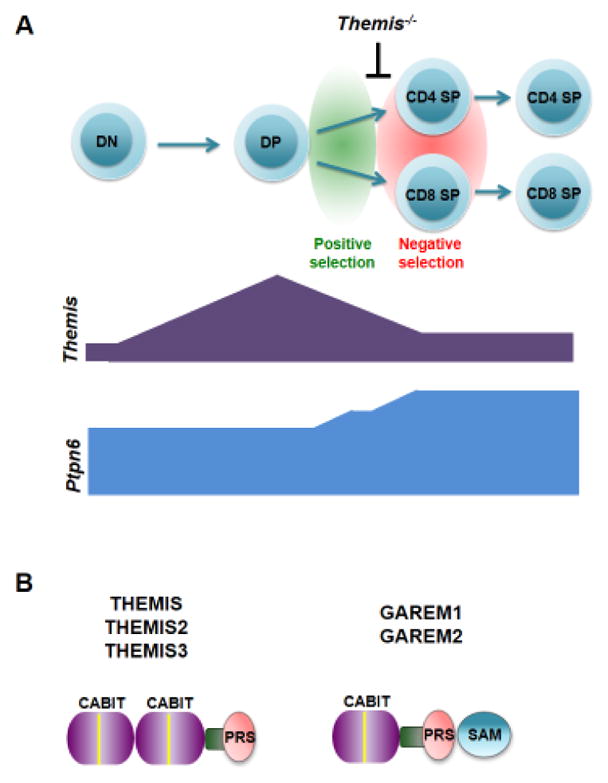

THEMIS made its dramatic debut on the immunology stage in 2009 when five separate groups published reports of its initial characterization [1–5]. Two labs discovered THEMIS by screening for T cell phenotypes in N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) induced mutant mice [2, 5], the other three by genetic or bioinformatic screening for genes specifically expressed in thymocytes [1, 3, 4]. Each lab reported a strikingly similar phenotype in their THEMIS mutant mice: maturation of thymocytes from the immature DN (please see Glossary) stage to the intermediate DP stage was unaffected, but maturation of DP thymocytes to the final CD4 SP or CD8 SP stage was defective with a more severe reduction in CD4 SP thymocytes and peripheral T cells. The block in T cell maturation in Themis−/− mice coincided with the stage where thymocytes undergo positive selection (Fig. 1A), (Box 1). This suggested an important role for THEMIS in the T cell antigen receptor (TCR) signaling response since TCR signals control this event [6]. However, initial screens of Themis−/− thymocytes either failed to identify a TCR signaling defect [1, 2, 4], or found relatively mild signaling defects that appeared insufficient to explain the severe developmental block [3].

Figure 1. Themis expression during T cell development.

A. Top, Schematic of T cell development showing the main stages of maturation defined by expression of the CD4 and CD8 co-receptors. The stage at which positive and negative selection occur and the point where thymocyte development is partially blocked in Themis−/− mice are shown. Bottom, Expression of Themis and Ptpn6 during thymocyte development. Results are from RT-PCR of cDNA from different thymocyte populations isolated by cell sorting. B. Domain schematic of the five mammalian CABIT proteins showing location of the globular CABIT module(s) (purple), proline-rich sequence (PRS; pink), conserved helical segment (green), conserved CABIT core sequence (yellow), and Sterile alpha motif (SAM) domain (blue).

Box 1. Thymocyte selection.

At the DP stage, thymocytes are subjected to a screening process called ‘thymocyte selection’ [57]. Thymocyte selection is controlled by the affinity of their expressed TCRs for self-peptides bound to self-MHC molecules (self-pMHC) that are presented to developing thymocytes by thymus stromal and dendritic cells [58]. Thymocyte selection is a cell fate decision that is controlled and determined by the signaling response of the TCR [6]. TCR ligand specificity is conferred by the ligand binding chains of the TCR complex (TCRα and TCRβ) that are generated by V-[D]-J recombination of germline gene segments [59]. V-[D]-J recombination is a semi-stochastic process that results in an extremely large degree of potential ligand binding diversity of the pre-selection TCR repertoire. Self-peptides bound to Class I or Class II MHC complexes engage the TCR on DP thymocytes together with the CD8 or CD4 co-receptor, respectively. TCR/self-pMHC interactions that are above a certain affinity threshold result in the transduction of TCR and co-receptor initiated signals that are sufficient to induce survival of DP thymocytes and their transition to the SP stage (positive selection). If the expressed TCR on a DP thymocyte fails to engage self-pMHC (or does so below a certain affinity threshold), the cell fails to generate sufficient signals for positive selection and undergoes death by apoptosis (referred to as ‘non-selection’). Thymocytes that express TCRs that bind with high affinity to self-pMHC transduce strong signals that induce cell death by apoptosis. This event, termed negative selection may occur concomitantly with positive selection at the DP stage or at a later immature SP stage. The outcome of thymocyte selection is the generation of a mature TCR repertoire that is self-tolerant as a result of negative selection but also minimally self-reactive as a result of positive selection to increase the probability that the TCR will be capable of binding to foreign peptides with sufficient affinity to transduce activating signals. Although positive selection is often portrayed as being mediated by only TCR/co-receptor-derived signals for simplicity, these are not sufficient for positive selection [36]. Other ligand interactions, signals, and/or factors provided by the thymus microenvironment are necessary for positive selection and SP thymocyte development [58].

The amino acid sequence of the THEMIS protein provided few clues to its function. THEMIS does not contain a known catalytic domain; in fact, only two defined motifs are present in THEMIS, a centrally located potential nuclear localization signal, and a C-terminal Proline Rich Sequence (PRS), (Fig. 1B). However, sequence analysis conducted by one of the groups that initially reported on THEMIS identified two tandem copies of a novel domain of unknown function, designated the CABIT (Cysteine-containing, All-Beta-In-THEMIS) module, that defines a new protein family [2] (Fig. 1B), (Box 2) and that would be revealed to be central to THEMIS activity.

Box 2. CABIT Modules.

CABIT (Cysteine-containing-All-Beta-In-THEMIS) modules are conserved protein domains first identified in THEMIS [2]. CABIT modules are approximately 260 amino acids and contain a highly conserved core sequence (ϕXCX7–26ϕXLPϕX3GXF with X = any amino acid and ϕ = any hydrophobic residue) [2]. CABIT modules are predicted to adopt an SH3-like β-barrel fold and contain conserved amino acids that are predicted to be ligand binding contact residues. CABIT modules are found only in metazoans but are widely represented in multiple species (to date, GenBank lists 1124 CABIT modules in 781 non-redundant proteins). Sequence homology-based searches performed in the initial THEMIS studies identified two related mammalian dual CABIT family members (Fig. 1b): ICB-1 (subsequently re-named THEMIS2) which is expressed in B and myeloid cells and THEMIS3 which is expressed only in the intestine [1–3]. THEMIS and THEMIS2 are present in all mammals, whereas THEMIS3 is absent in primates. Two single CABIT module proteins are also expressed in mammals; GAREM1 which is broadly expressed [31] and GAREM2 which is expressed in neuronal cells [32]. GAREM1, GAREM2 and most other single CABIT module proteins also contain a Sterile alpha motif (SAM) putative protein interaction domain (Fig. 1b). Despite their abundance, to date no CABIT containing proteins other than THEMIS, THEMIS2, THEMIS3, GAREM1 and GAREM2 and the Drosophila protein Serrano [60] have been extensively studied. The function of the THEMIS CABIT modules was recently determined (see text) [23].

The fog begins to clear

Genetic reconstitution studies aimed at mapping functional domains within THEMIS identified a requirement for the PRS, NLS and CABIT sequences for THEMIS in vivo activity (Box 3). A major focus of early research on THEMIS was to identify potential interacting proteins. In their initial publications on THEMIS, three groups independently reported that THEMIS binds to the ubiquitous cytosolic adapter Growth factor receptor-bound protein 2 (GRB2) [1, 2, 4]. GRB2 contains a central Src homology 2 (SH2) domain flanked by two SH3 domains [7]. The THEMIS:GRB2 interaction was shown to require the THEMIS PRS which binds to one of the GRB2 SH3 domains [8–10]. GRB2, via its SH2 domain, recruits THEMIS to the scaffolding transmembrane T cell adapter Linker for Activation of T cells (LAT) upon TCR engagement [8, 9, 11]. The THEMIS:GRB2 interaction is required for THEMIS in vivo activity [9, 10, 12] indicating that recruitment of THEMIS to LAT by GRB2 is essential for its function.

Box 3. Mapping THEMIS functional domains.

Three independent groups performed genetic reconstitution studies with domain deletion variants of THEMIS to determine which regions are required for its in vivo activity. THEMIS proteins lacking either the PRS [9, 10, 12] or the NLS [10, 12] were unable to rescue T cell maturation in Themis−/− mice. As described in the text, the PRS is required for binding of THEMIS to the cytosolic adapter GRB2. THEMIS is detectable in the nucleus of thymocytes [1, 8, 10, 12] and the NLS is required for its nuclear localization [8, 10, 12]; however, the function of THEMIS in the nucleus remains unclear and requires additional investigation. A THEMIS protein containing C/A mutations of the conserved cysteines in CABIT1(Cys153) and CABIT2(Cys413) was capable of rescuing T cell development in Themis−/− mice [12] whereas deletion of the 23–24aa conserved core sequences in either the CABIT1 or CABIT2 module abolished THEMIS function [10]. Interestingly, the developmental block in Themis−/−thymocytes was significantly worsened by expression a transgenic THEMIS protein that lacked the CABIT1 core sequence (ΔCore1), and THEMIS ΔCore1 had a dominant negative effect on T cell maturation when expressed in Themis+/+ mice [10]. THEMIS is rapidly tyrosine phosphorylated by the protein tyrosine kinase LCK following TCR engagement [8, 9]. Mutagenesis experiments indicate that Y540 and Y541 in human THEMIS (Y542 and Y543 in mouse THEMIS) are the major sites of tyrosine phosphorylation [9]. Although the functional relevance of THEMIS phosphorylation has not been determined, a THEMIS protein containing a Y-F mutation of Y540 and Y541 was unable to bind to GRB2 [9].

More recent studies identified an interaction between THEMIS and the protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) Src homology region 2 domain-containing phosphatase-1 (SHP-1) encoded by the gene Ptpn6 [13–15] suggesting that THEMIS forms a tri-molecular complex with GRB2 and SHP-1 [9]. Establishing a connection between THEMIS and SHP-1 was an important breakthrough in the THEMIS story. SHP-1 is an inhibitory tyrosine phosphatase that de-phosphorylates and inactivates several key proximal effectors in the TCR signaling pathway including the protein tyrosine kinases LCK and Zeta chain associated protein kinase 70 (ZAP-70) and the guanine nucleotide exchange factor, Vav1 [16–18]. A robust finding, confirmed by two groups, was that tyrosine phosphorylation of SHP-1 is markedly reduced in Themis−/− thymocytes, both before and after TCR stimulation [14, 15]. These observations energized research aimed at identifying a role for THEMIS in regulating SHP-1 activity. Two lines of investigation were pursued by separate groups that led in entirely different directions, eventually resulting in contrasting models of THEMIS function.

Two models for THEMIS function

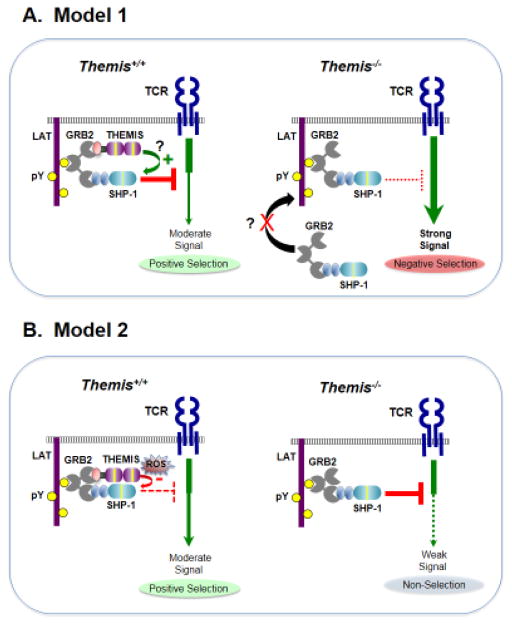

Model 1: THEMIS dampens TCR signaling in DP thymocytes to prevent crossing the threshold for negative selection

In their initial report on Themis−/− mice, one group found that calcium flux and ERK activation were reduced in Themis−/− thymocytes following TCR stimulation [3]. They later found that ERK phosphorylation, IL-2 production and Nuclear Factor of Activated T-cells (NFAT)/Activator Protein 1 (AP-1) reporter expression were reduced in response to TCR stimulation in Jurkat T cells following shRNA-mediated knock-down of Themis expression, and concluded that THEMIS is a positive regulator of TCR signaling [11, 19]. However, in subsequent studies, the same group reported that activation (phosphorylation) of several TCR signaling effectors including LCK, LAT, Phospholipase C-γ1 (PLC-γ1), and Extracellular signal-Regulated Kinase (ERK) as well as calcium flux were increased in Themis−/− thymocytes or in THEMIS knock-down Jurkat T cells when the cells were stimulated with low affinity tetramer/peptide ligands that promote positive selection in vivo [13, 15]. They concluded that TCR signaling responses are enhanced in the absence of THEMIS, but this effect is only evident under sub-maximal stimulation conditions [15]. Based on these latter observations, a model was proposed for THEMIS function in thymocytes [15, 20] referred to here as Model 1 (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2. Two models of Themis function in thymocytes.

THEMIS expression is high in CD4+CD8+ (DP) thymocytes when positive selection occurs. THEMIS and SHP-1 bind to the cytosolic adapter GRB2 and are recruited by GRB2 to the scaffolding adapter LAT following TCR stimulation. A. Model 1. Left, in Themis+/+ thymocytes, THEMIS facilitates recruitment of SHP-1 to LAT via GRB2 and/or enhances SHP-1 PTP activity. TCR/co-receptor signals are attenuated by SHP-1 so that signals initiated by low affinity positively selecting TCR/self-pMHC interactions are appropriate for positive selection and do not induce negative selection. Right, in the absence of THEMIS (Themis−/− thymocytes), SHP-1 activity is reduced and/or SHP-1 recruitment to LAT is impaired. Positively selecting TCR/self-pMHC interactions transduce strong signals that trigger negative selection. B. Model 2. Left, the THEMIS CABIT modules bind to the SHP-1 phosphatase domain blocking access to substrate and promoting or stabilizing oxidation of the SHP-1 catalytic cysteine by Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) thereby inhibiting SHP-1 phosphatase activity. Inhibition of SHP-1 enables low affinity TCR interactions to generate signals sufficient for positive selection. Right, in the absence of THEMIS (Themis−/− thymocytes), SHP-1 PTP activity is not attenuated and low affinity TCR/self-pMHC interactions that normally are sufficient for positive selection fail to induce positive selection resulting in cell death by non-selection (also known as ‘death by neglect’). The sequences in SHP-1 responsible for binding to the GRB2 SH3 domain have not been identified; therefore, the SHP-1:GRB2 interaction depicted is speculative. pY, phospho-tyrosine.

In Model 1, THEMIS dampens TCR signaling initiated by low affinity self-pMHC interactions, preventing transmission of a strong signaling response to these stimuli that would trigger negative selection [15, 20]. THEMIS is speculated to function by promoting SHP-1 PTP activation and/or by facilitating its recruitment to LAT where it is brought into contact with its primary targets [20]. SHP-1 PTP activity was not assayed in Themis−/− thymocytes, but was inferred to be reduced from the reduction in SHP-1 tyrosine phosphorylation [15, 20].

Model 2: THEMIS enhances TCR signaling enabling thymocytes to reach the threshold required for positive selection

Experiments recently performed in our laboratories confirmed that ERK activation is enhanced in Themis−/− thymocytes when they are stimulated under sub-maximal conditions [14]. However, we found that tyrosine phosphorylation of Vav1 was reduced in Themis−/− thymocytes under the same stimulation conditions [14]. In vivo activated (CD69+) Themis−/− DP thymocytes expressed lower amounts of CD5 and a Nuclear receptor 77 (Nur77)-Green Fluorescence Protein (GFP) reporter [1, 14], both indicators of TCR signal intensity [21, 22]. These results suggested that while activation of some signaling effectors is enhanced in Themis−/− thymocytes under certain submaximal in vitro stimulation conditions, THEMIS deficiency results in an overall reduction in the intensity of the integrated TCR signaling response in vivo [14].

To gain further insight into THEMIS function, we focused our studies on the novel CABIT modules. We discovered that the THEMIS CABIT modules bind directly to SHP-1 and inhibit SHP-1 PTP activity both in vitro and in vivo by blocking access to substrate and by promoting or sustaining oxidation of the SHP-1 catalytic cysteine [23], (Box 4). The latter inhibitory mechanism, which represents a novel mode of biological PTP regulation, required the presence of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) at the time of TCR stimulation. Signaling defects, including reduced tyrosine phosphorylation of the protein tyrosine kinases LCK and ZAP-70, which are targets of SHP-1, were revealed in Themis−/− thymocytes following TCR stimulation in the presence but not in the absence of ROS (e.g., H2O2) [23]. Collectively, these results suggested an alternative model for THEMIS function in thymocytes, referred to here as Model 2 (Fig. 2B).

Box 4. Redox regulation of protein tyrosine phosphatases.

All Class I protein tyrosine phosphatases including SHP-1 and SHP-2 contain a catalytic cysteine within a conserved ‘signature motif’ (I/V)HCxxGxxR(S/T) that catalyzes hydrolysis of tyrosine phosphate by forming a thio-phosphate intermediate [16, 61]. The conserved adjacent proton accepting histidine residue is critical for lowering the acid dissociation constant (pKa) of the active site cysteine maintaining it in the active thiol (S−) deprotonated state at physiological pH. Although this configuration is essential for phosphatase activity in vivo, it also renders the reduced cysteine thiol extremely susceptible to oxidation and inactivation by Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) such as hydrogen peroxide. The active site cysteine thiol can be reversibly oxidized to the sulfenic acid (-SOH) state or less frequently, irreversibly ‘hyperoxidized’ to the sulfinic (-SO2H) or sulfonic (-SO3H) state. The oxidized sulfenated active site cysteine thiol can subsequently be reduced and reactivated by glutathione and cytosolic redox regulatory proteins such as glutaredoxin, thioredoxin and peroxiredoxin. An important cellular mechanism for regulating protein tyrosine phosphatases is through localized production of ROS by cell surface NADPH oxidases that are co-activated with antigen receptor stimulation [33, 62].

In Model 2, THEMIS functions to enhance TCR signaling in DP thymocytes by inhibiting SHP-1 PTP activity. Model 2 proposes that the developmental defect in Themis−/− thymocytes is secondary to reduced, not enhanced, TCR signaling responses. In the absence of THEMIS, TCR/self-pMHC interactions fail to produce signals sufficient for positive selection of DP thymocytes leading to ‘non-selection’ (also known as ‘death by neglect’) (Box 1).

Examining the evidence for Model 1 and Model 2

Regulation of SHP-1 PTP activity by THEMIS

Model 1 and Model 2 propose opposite regulatory roles for THEMIS with respect to SHP-1 (activating or inhibitory, respectively) and therefore predict that reducing SHP-1 expression in thymocytes should have opposite effects on the Themis−/− phenotype. In Model 1, reducing the amount of SHP-1 in Themis−/− thymocytes should exacerbate the developmental block (or have no effect if SHP-1 activation requires THEMIS). In Model 2, reducing the amount of SHP-1 in Themis−/− thymocytes should alleviate the block in positive selection. The results of this key experiment supported the mechanism proposed in Model 2 [23]. Thymocyte-specific deletion of Ptpn6, the gene encoding SHP-1, resulted in a dramatic rescue of positive selection demonstrated by increased SP thymocyte and T cell numbers in Themis−/− mice indicating that the Themis−/− defect is a result of increased SHP-1 activity [23].

The phenotype of Ptpn6−/− mice does not resemble that of Themis−/− mice as might have been predicted by Model 1 [24, 25]. In contrast to Themis−/− mice, positive selection is not markedly impaired in Ptpn6−/− mice [24], although the survival of post-selection SP thymocytes is reduced, possibly due to enhanced negative selection [25]. In Themis−/− mice, a defect in thymocyte maturation is observed at the first stage of positive selection (TCRint CD69int) [1, 3] whereas Ptpn6−/− mice do not exhibit a developmental defect until the later TCRhi CD69hi post-selection stage [25]. Also, CD4 SP thymocyte and T cell numbers are unaffected or only slightly reduced in Ptpn6−/− mice [24, 25] but are strongly diminished in Themis−/− mice [1–5]. The proponents of Model 1 have proposed that positive regulation of both SHP-1 and the closely related but widely expressed SH2 PTP, SHP-2 by THEMIS could explain the milder phenotype of Ptpn6−/− mice compared to Themis−/− mice if SHP-1 and SHP-2 are functionally redundant, and predicted that the phenotype of thymocytes lacking both SHP-1 and SHP-2 should phenocopy that of Themis−/− thymocytes [15]. However, this speculation is at odds with the recent finding that deletion of Ptpn6 rescues the developmental block in Themis−/− mice [23].

Effect of SHP-1 tyrosine phosphorylation on SHP-1 PTP activity

As mentioned previously, tyrosine phosphorylation of SHP-1 is markedly reduced in Themis−/− thymocytes [14, 15]. This finding was interpreted by the group that proposed Model 1 as indicative of reduced SHP-1 PTP activity [15]. Auto-phosphorylation of key tyrosine residues within the ‘activation loop’ of protein tyrosine kinases (PTKs) results in increased PTK activity [26–28]. Although a similar regulatory function for tyrosine phosphorylation has been inferred for PTPs, experimental data do not strongly support the notion that tyrosine phosphorylation influences the in vivo PTP activity of SHP-1. In vitro and transfection studies have shown that phosphorylation of C-terminal tyrosines in SHP-1 can result in enhanced SHP-1 PTP activity by relieving auto-inhibition of the SHP-1 catalytic domain by the SHP-1 SH2 domains [29]. However, the in vivo significance of this potential regulatory mechanism has been questioned [16]. Tyrosine phosphorylation of SHP-1 is not required for PTP activity, and constitutive association of SHP-1 with GRB2 or other ligands in vivo likely occupies the SHP-1 SH2 domains preventing autoinhibition [16]. Also, the C-terminal tyrosines of SHP-1 that are targets for phosphorylation are rapidly auto-dephosphorylated in vivo by catalytically active SHP-1 [16]. We demonstrated that SHP-1 PTP activity is increased in Themis−/− thymocytes even though tyrosine phosphorylation of SHP-1 is markedly reduced [23]. In addition, in cell lines expressing SHP-1 and one of its substrates, Spleen tyrosine Kinase (SYK), co-transfection of THEMIS inhibits SHP-1 PTP activity as demonstrated by increased tyrosine phosphorylation of SYK, but tyrosine phosphorylation of SHP-1 is also increased [23]. Also notable are results indicating that tyrosine phosphorylation of SHP-1 is not required for THEMIS:GRB2:SHP-1 association or for THEMIS-mediated regulation of TCR signaling [13]. Taken together, these findings indicate that the reduced tyrosine phosphorylation of SHP-1 in Themis−/− thymocytes most likely reflects and is a consequence of increased SHP-1 PTP activity.

THEMIS:SHP-1 interaction

Based on the results of experiments performed in Jurkat T cells, it was concluded previously that interaction of THEMIS and SHP-1 is GRB2-dependent since a THEMIS protein lacking the PRS, which is required for GRB2 binding, failed to co-immunoprecipitate SHP-1 [13]. However, a close examination of the data from those experiments indicates that SHP-1 does in fact bind to THEMIS variants that either lack the PRS or contain a mutation of the PRS, although the THEMIS-ΔPRS:SHP-1 interaction is clearly reduced compared to that observed with WT THEMIS [13]. We recently reported that purified THEMIS binds directly to SHP-1 in vitro [23]. We also found that THEMIS could be co-immunoprecipitated with SHP-1 in GRB2-deficient thymocytes and that a THEMIS protein lacking the PRS can co-immunoprecipitate SHP-1 in transfected cells [23]. In vitro binding experiments demonstrated that the THEMIS:SHP-1 interaction is mediated by the THEMIS CABIT modules that bind directly to the SHP-1 catalytic domain [23]. Thus, although GRB2 likely has an important role in recruitment of both THEMIS and SHP-1 to LAT following TCR engagement [9], our recent data demonstrate that GRB2 is not required for THEMIS:SHP-1 association or for negative regulation of SHP-1 by THEMIS [23].

Reconciling the Models: the TCR signaling conundrum

As mentioned above, several experimental results support an activating role for THEMIS in TCR signaling. THEMIS inhibits the activity of SHP-1, which has well documented inhibitory effects on TCR signaling responses [16], and activation (phosphorylation) of VAV1 in Themis−/− thymocytes is reduced following TCR/co-receptor cross-linking [14]. In addition, Nur77-GFP reporter expression, which reflects the intensity of TCR/co-receptor signaling [21], was reduced in freshly isolated CD69+ Themis−/− thymocytes that had received positively selecting TCR signals in vivo and that were prevented from undergoing apoptosis by transgenic overexpression of the pro-survival protein B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) [14]. The other mammalian CABIT proteins have also been shown to have activating functions in receptor signaling. The B cell homologue of THEMIS, THEMIS2, lowers the threshold for B cell receptor-mediated activation by low avidity antigens and therefore has a positive role in B cell receptor signaling [30]. THEMIS and THEMIS2 are functionally interchangeable since transgenic expression of THEMIS2 rescued the developmental defect in Themis−/− mice [8]. The single CABIT module mammalian proteins GAREM1 (GRB2-associated and regulator of MAPK1, subtype 1) and GAREM2, are positive regulators of ERK signaling in response to epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor engagement [31, 32]. Nevertheless, it was reported that ERK activation, calcium flux, NFATC2 nuclear translocation and other effector responses [15] are enhanced in Themis−/− thymocytes under sub-maximal TCR/co-receptor stimulation conditions [14, 15]. The puzzling and seemingly contradictory results observed from assays of TCR/co-receptor signaling in Themis−/− thymocytes by different groups indicate that the effects of THEMIS deficiency on TCR signaling responses are more complex than can be explained by either Model 1 or Model 2 in their simplest forms. Here, we propose two possible explanations for the discrepancies noted in TCR signaling responses in Themis−/− thymocytes that could reconcile these conflicting results.

A role for ROS in T cell development?

We found that inhibition of SHP-1 by THEMIS was dependent in part on ROS and that activation of the proximal signaling effectors LCK and ZAP-70 is reduced in Themis−/− thymocytes when they are stimulated by TCR/co-receptor cross-linking in the presence of ROS [23]. On the other hand, ROS (or cellular redox status) was not evaluated or used as a variable in the assays that reported enhanced TCR signaling responses in THEMIS deficient thymocytes and Jurkat T cells [13, 15]. ROS, generated intrinsically or by myeloid cells at sites of T cell activation have been shown to regulate lymphocyte signaling responses, in part by inhibiting PTPs including SHP-1 [33]. The role of ROS in the thymus has not been extensively examined; however, two studies indicate that ROS have a positive effect on T cell maturation [34, 35]. It is also worth noting that the methods used to assess TCR/co-receptor signaling responses in Themis−/− thymocytes by the groups advocating for either Model 1 or Model 2 are not sufficient for positive selection. Positive selection requires the presence of thymic stromal cells which presumably provide additional interactions and factors (that might include ROS) that are essential for completion of this process [36]. Consequently, the actual effect(s) and consequences of THEMIS deficiency on signaling responses relevant to positive selection may not have been fully or accurately revealed by in vitro administered TCR/co-receptor stimulation alone, regardless of type.

Regulation of SHP-2 by THEMIS?

Our recent results demonstrated that THEMIS inhibits SHP-1 activity as depicted in Model 2 (Fig. 2). However, several findings also suggest that THEMIS regulates the activity of SHP-2. SHP-2 was co-imunoprecipitated with THEMIS in Jurkat T cells and in transfected HEK-293 cells [13, 15]. We found that THEMIS binds directly to SHP-2 and inhibits SHP-2 PTP activity in vitro, though the inhibitory effect on SHP-2 was not as pronounced as on SHP-1 [23]. The precise function of SHP-2 in TCR signaling has not been firmly resolved; however, in contrast to SHP-1, which appears to have an exclusively inhibitory role in cell signaling, SHP-2 has been ascribed both inhibitory and activating roles depending on the substrate [16, 17, 37, 38]. Indeed, T-lineage specific deletion of Ptpn11, the gene encoding SHP-2, results in impaired TCR induced ERK activation in thymocytes and reduced TCR-induced IL-2 production and CD69 and CD25 expression in T cells [39]. Enhanced activity of both SHP-1 and SHP-2 could therefore result in a complex phenotype with both activating and inhibitory effects on specific TCR/co-receptor signaling effectors and pathways similar to what has been reported in Themis−/− thymocytes [13–15, 23]. Nevertheless, it is important to note that the substantial rescue of positive selection in Themis−/− thymocytes by deletion of Ptpn6, but not by deletion of Ptpn11, indicates that the main effect of THEMIS relevant to T cell development is through inhibition of SHP-1 PTP activity [23].

The Themis−/− effect - Non-selection or negative selection?

Distinguishing between enhanced negative selection and failure of positive selection can be surprisingly difficult, due in large part to the fact that both result in apoptotic cell death [40]. In Model 1, the developmental defect in Themis−/− mice is proposed to be caused by enhanced TCR signaling responses that convert positive selection into negative selection resulting in cell death by apoptosis [15, 20]. Supporting that mechanism is the finding that stimulation of Themis−/− DP thymocytes with low affinity TCR ligands that have been shown to promote positive selection in vivo resulted in increased activation of caspase-3 [15]. Knockdown of Themis expression in Jurkat T cells also resulted in increased caspase-3 induction and increased apoptosis following TCR stimulation [13]. Although these studies demonstrate that THEMIS deficient thymocytes and T cells are more sensitive to activation-induced cell death, the conclusion that in vivo signals initiated by positively selecting self-pMHC interactions trigger negative selection is speculative, particularly since the mechanism proposed to be responsible for induction of negative selection in Themis−/− thymocytes, namely reduced SHP-1 PTP activity, is no longer tenable [23].

Two studies analyzed whether the disruption of Bcl2l11, the gene encoding BIM, a pro-apoptotic factor required for negative selection [41], could rescue T cell development in Themis−/− mice [14, 15]. Numbers of CD4 SP and CD8 SP T cells were increased in Themis−/− Bcl2l11−/− mice relative to Themis−/− mice, but were still significantly reduced compared to Themis+/+ Bcl2l11−/− control mice [14, 15]. Also, CD4 SP thymocytes were mostly immature (CD24hi) in Themis−/− Bcl2l11−/− mice [14]. Similar results were observed in Themis−/− mice that express transgenic BCL2 [1]. These findings suggest that deletion of Bcl2l11 or overexpression of BCL2 does not rescue positive selection of Themis−/− thymocytes as previously claimed [15], but instead prevents deletion of strongly self-reactive SP thymocytes that would otherwise be negatively selected.

An alternative explanation for the increased apoptosis of Themis−/− thymocytes is that it results from elevated SHP-1 activity. Several studies have revealed a positive role for SHP-1 in the induction of Fas-mediated apoptosis without causing increased Fas surface expression [42–44]. Although Fas-induced cell death is not thought to be a major pathway for negative selection, DP thymocytes, and especially CD24hiCD4+CD8− thymocytes, the first population that is numerically reduced in Themis−/− mice [1], are susceptible to Fas-mediated apoptosis [45–47].

A Theoretical argument for Model 2

A workable model for THEMIS function should provide an explanation for its high and relatively restricted expression in DP thymocytes (Fig. 1). Model 1 is predicated on the premise that DP thymocytes require mechanisms to attenuate TCR signaling to prevent inappropriate triggering of negative selection by low affinity TCR/self p-MHC interactions whereas Model 2 speculates that DP thymocytes require TCR signal enhancing mechanisms to enable those same interactions to transmit signals that are sufficient for positive selection. Several studies have demonstrated that, despite lower TCR surface expression, preselection thymocytes are more sensitive to TCR-mediated activation than mature T cells [6, 48, 49]. The enhanced sensitivity of DP thymocytes to TCR engagement has been speculated to be crucial to allow low affinity TCR/self-p-MHC interactions to induce positive selection, whereas the reduced responsiveness of mature T cells to the same self-pMHC interactions prevents T cell activation and overt autoimmunity by the same self-ligands [50, 51]. Similar to THEMIS, mir181a, TESPA, and Scn4b, which each function to enhance TCR signaling responses, are highly expressed in DP thymocytes but are down-regulated in mature T cells [52–54]. On the other hand, we are unaware of examples of TCR signaling inhibitors that are selectively expressed in DP thymocytes which would support the underlying premise of Model 1.

It is also potentially revealing that CD4 SP thymocyte development is much more severely impacted than CD8 SP thymocyte development in Themis−/− mice [1–5]. CD4 SP development is dependent upon persistent TCR signaling whereas CD8 SP development requires cessation of TCR signaling and is dependent on IL-7 mediated survival signals [55]. We previously reported that MHC class II restricted Themis−/− thymocytes are ‘re-directed’ from the CD4 SP to the CD8 SP lineage [1] consistent with impaired/disrupted TCR signaling [56]. Thus, the phenotype of in Themis−/− mice is suggestive of a defect that results in a reduction in or interruption of TCR signaling.

Concluding remarks and future perspectives

Eight years after the first THEMIS reports were published, we are now just beginning to understand this remarkable molecule. The identification of a function for the CABIT modules represents an important milestone in this process and suggests a new ‘signal enhancing’ model for THEMIS function that we contend is more strongly supported by prevailing experimental data than the previous ‘signal dampening’ model. Although the function of THEMIS in thymocyte development has become much clearer, THEMIS has raised as many questions as it has answered (see Outstanding Questions) promising to keep interested parties occupied for some time to come.

Outstanding Questions.

Do the THEMIS CABIT modules regulate the activity of tyrosine phosphatases other than SHP-1 (e.g., SHP-2) in vivo? If so, does this explain the complex effects of THEMIS deficiency on TCR signaling responses?

What are the targets of the other mammalian CABIT proteins (THEMIS3, GAREM1 and GAREM2)? Do they also regulate SHP-1 PTP activity or do different CABIT proteins have different targets?

How does THEMIS inhibit SHP-1 at the molecular level? What is the structure of the CABIT modules? Which residues are important for contact with the SHP-1 phosphatase domain and for inhibition of SHP-1?

Does THEMIS regulate specific mature T cell effector responses? Is THEMIS expression regulated in mature T cell subsets (memory T cells, T follicular helper cells, Tregs, γδ T cells) or in response to TCR-mediated activation or cytokine signaling?

What role do ROS have in T cell development? Are ROS generated in thymocytes in response to thymocyte:stromal cell interactions? Are macrophages and dendritic cells in the thymus important sources of ROS? Thymocyte development cannot currently be recapitulated in vitro. Could ROS be one of the key factors supplied by the thymus that is required for DP to SP thymocyte development?

Trends.

THEMIS plays a critical role in T cell development by promoting thymocyte positive selection.

THEMIS is the founding member of a large protein family defined by the presence of a novel conserved sequence, the CABIT module.

A previous model proposed an inhibitory role for THEMIS in TCR signaling wherein THEMIS activates the tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 preventing positively selecting ligands from generating strong signals that cross the negative selection threshold.

A recent study found that the THEMIS CABIT modules function to inhibit SHP-1 tyrosine phosphatase activity. These results support a new model wherein THEMIS enhances TCR signaling by low affinity ligands enabling thymocytes to reach the signaling threshold for positive selection.

CABIT modules represent a new mechanism for regulation of phosphotyrosine signaling in metazoans.

Acknowledgments

We thank Remy Bosselut and B.J. Fowlkes for helpful comments and suggestions. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver, NICHD (PEL: Project number 1ZIAHD001803-19), the Medical Research Council, UK, (RC), and INSERM, France (RL).

Glossary

- CABIT

Cysteine-containing-All-Beta-In-THEMIS. A newly described conserved protein module detected in a large number of metazoan proteins (see Box 2).

- DN

Double negative (CD4−CD8−) thymocytes. The most immature stage of thymocyte development.

- DP

Double positive (CD4+CD8+) thymocytes. The intermediate stage of thymocyte development. Positive selection occurs at the DP stage.

- MHC

Major Histocompatibility Complex. A chromosomal locus that encodes cell surface protein complexes that are responsible for antigen presentation to the TCR. MHC Class I complexes bind to the TCR and the CD8 co-receptor; MHC Class II complexes bind to the TCR and the CD4 co-receptor.

- pMHC

Peptide bound MHC (see MHC).

- PTP

Protein tyrosine phosphatase. Enzymes including SHP-1 and SHP-2 that remove phosphate groups from phosphorylated tyrosines on proteins.

- PRS

Proline Rich Sequence (also known as Proline Rich Region; PRR). A short amino acid sequence that contains multiple prolines. PRS frequently bind to SH3 domains.

- ROS

Reactive Oxygen Species. Chemically reactive species containing oxygen (e.g., peroxides, superoxide, hydroxyl radical, singlet oxygen). ROS are derived from NADPH oxidase complexes in the cell membrane and by mitochondrial metabolism.

- SH2 domain

Src-homology-2 domain. Conserved protein domain frequently found in signaling and adapter proteins, especially those that participate in tyrosine kinase signaling pathways. SH2 domains typically bind to phosphorylated tyrosine residues in proteins.

- SH3 domain

Src-homology-3 domain. Conserved protein domain frequently found in signaling and adapter proteins that typically binds to proline-rich peptide sequences (PRS) in proteins.

- SP

Single positive (CD4+CD8−; CD4 SP or CD4−CD8+; CD8 SP) thymocytes. The final stage of thymocyte development. Mature CD4 SP and CD8 SP thymocytes exit the thymus and populate the peripheral lymphoid organs. Negative selection occurs primarily at the DP and immature SP stages.

- TCR

T cell antigen receptor. The multi-subunit cell surface complex responsible for binding to self or foreign peptides presented by self-MHC molecules. The TCR transmits signals that are required for thymocyte (positive and negative) selection, thymocyte maturation and mature T cell activation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lesourne R, et al. Themis, a T cell-specific protein important for late thymocyte development. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:840–847. doi: 10.1038/ni.1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson AL, et al. Themis is a member of a new metazoan gene family and is required for the completion of thymocyte positive selection. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:831–839. doi: 10.1038/ni.1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fu G, et al. Themis controls thymocyte selection through regulation of T cell antigen receptor-mediated signaling. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:848–856. doi: 10.1038/ni.1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patrick MS, et al. Gasp, a Grb2-associating protein, is critical for positive selection of thymocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:16345–16350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908593106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kakugawa K, et al. A novel gene essential for the development of single positive thymocytes. Molecular and cellular biology. 2009;29:5128–5135. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00793-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hogquist KA, Jameson SC. The self-obsession of T cells: how TCR signaling thresholds affect fate ‘decisions’ and effector function. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:815–823. doi: 10.1038/ni.2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jang IK, et al. Grb2, a simple adapter with complex roles in lymphocyte development, function, and signaling. Immunol Rev. 2009;232:150–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lesourne R, et al. Interchangeability of Themis1 and Themis2 in thymocyte development reveals two related proteins with conserved molecular function. J Immunol. 2012;189:1154–1161. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paster W, et al. GRB2-mediated recruitment of THEMIS to LAT is essential for thymocyte development. J Immunol. 2013;190:3749–3756. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okada T, et al. Differential function of Themis CABIT domains during T cell development. PloS one. 2014;9:e89115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brockmeyer C, et al. T cell receptor (TCR)-induced tyrosine phosphorylation dynamics identifies THEMIS as a new TCR signalosome component. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:7535–7547. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.201236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zvezdova E, et al. In vivo functional mapping of the conserved protein domains within murine Themis1. Immunol Cell Biol. 2014;92:721–728. doi: 10.1038/icb.2014.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paster W, et al. A THEMIS:SHP1 complex promotes T-cell survival. The EMBO journal. 2015;34:393–409. doi: 10.15252/embj.201387725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zvezdova E, et al. Themis1 enhances T cell receptor signaling during thymocyte development by promoting Vav1 activity and Grb2 stability. Sci Signal. 2016;9:ra51. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aad1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fu G, et al. Themis sets the signal threshold for positive and negative selection in T-cell development. Nature. 2013;504:441–445. doi: 10.1038/nature12718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pao LI, et al. Nonreceptor protein-tyrosine phosphatases in immune cell signaling. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:473–523. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lorenz U. SHP-1 and SHP-2 in T cells: two phosphatases functioning at many levels. Immunol Rev. 2009;228:342–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00760.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stebbins CC, et al. Vav1 dephosphorylation by the tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 as a mechanism for inhibition of cellular cytotoxicity. Molecular and cellular biology. 2003;23:6291–6299. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.17.6291-6299.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gascoigne NR, Palmer E. Signaling in thymic selection. Curr Opin Immunol. 2011;23:207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gascoigne NR, Acuto O. THEMIS: a critical TCR signal regulator for ligand discrimination. Curr Opin Immunol. 2015;33:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2015.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moran AE, et al. T cell receptor signal strength in Treg and iNKT cell development demonstrated by a novel fluorescent reporter mouse. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2011;208:1279–1289. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Azzam HS, et al. CD5 expression is developmentally regulated by T cell receptor (TCR) signals and TCR avidity. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1998;188:2301–2311. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi S, et al. THEMIS enhances TCR signaling and enables positive selection by selective inhibition of the phosphatase SHP-1. Nat Immunol. 2017;18:433–441. doi: 10.1038/ni.3692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson DJ, et al. Shp1 regulates T cell homeostasis by limiting IL-4 signals. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2013;210:1419–1431. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martinez RJ, et al. Targeted loss of SHP1 in murine thymocytes dampens TCR signaling late in selection. Eur J Immunol. 2016;46:2103–2110. doi: 10.1002/eji.201646475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lemmon MA, Schlessinger J. Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell. 2010;141:1117–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang H, et al. ZAP-70: an essential kinase in T-cell signaling. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a002279. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a002279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson LN, et al. Active and inactive protein kinases: structural basis for regulation. Cell. 1996;85:149–158. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Z, et al. The role of C-terminal tyrosine phosphorylation in the regulation of SHP-1 explored via expressed protein ligation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:4668–4674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210028200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng D, et al. Themis2 lowers the threshold for B cell activation during positive selection. Nat Immunol. 2017;18:205–213. doi: 10.1038/ni.3642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tashiro K, et al. GAREM, a novel adaptor protein for growth factor receptor-bound protein 2, contributes to cellular transformation through the activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284:20206–20214. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.021139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taniguchi T, et al. A brain-specific Grb2-associated regulator of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (Erk)/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) (GAREM) subtype, GAREM2, contributes to neurite outgrowth of neuroblastoma cells by regulating Erk signaling. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013;288:29934–29942. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.492520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simeoni L, Bogeski I. Redox regulation of T-cell receptor signaling. Biol Chem. 2015;396:555–568. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2014-0312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moon EY, et al. Reactive oxygen species induced by the deletion of peroxiredoxin II (PrxII) increases the number of thymocytes resulting in the enlargement of PrxII-null thymus. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:2119–2128. doi: 10.1002/eji.200424962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jin R, et al. Redox balance of mouse medullary CD4 single-positive thymocytes. Immunol Cell Biol. 2013;91:634–641. doi: 10.1038/icb.2013.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chidgey AP, Boyd RL. Thymic stromal cells and positive selection. APMIS. 2001;109:481–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2001.apm090701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen L, Flies DB. Molecular mechanisms of T cell co-stimulation and co-inhibition. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2013;13:227–242. doi: 10.1038/nri3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stanford SM, et al. Regulation of TCR signalling by tyrosine phosphatases: from immune homeostasis to autoimmunity. Immunology. 2012;137:1–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2012.03591.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nguyen TV, et al. Conditional deletion of Shp2 tyrosine phosphatase in thymocytes suppresses both pre-TCR and TCR signals. J Immunol. 2006;177:5990–5996. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.5990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Surh CD, Sprent J. T-cell apoptosis detected in situ during positive and negative selection in the thymus. Nature. 1994;372:100–103. doi: 10.1038/372100a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bouillet P, et al. BH3-only Bcl-2 family member Bim is required for apoptosis of autoreactive thymocytes. Nature. 2002;415:922–926. doi: 10.1038/415922a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Su X, et al. Defective expression of hematopoietic cell protein tyrosine phosphatase (HCP) in lymphoid cells blocks Fas-mediated apoptosis. Immunity. 1995;2:353–362. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chakrabandhu K, et al. An Evolution-Guided Analysis Reveals a Multi-Signaling Regulation of Fas by Tyrosine Phosphorylation and its Implication in Human Cancers. PLoS biology. 2016;14:e1002401. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Daigle I, et al. Death receptors bind SHP-1 and block cytokine-induced anti-apoptotic signaling in neutrophils. Nat Med. 2002;8:61–67. doi: 10.1038/nm0102-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Castro JE, et al. Fas modulation of apoptosis during negative selection of thymocytes. Immunity. 1996;5:617–627. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80275-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kishimoto H, Sprent J. Negative selection in the thymus includes semimature T cells. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1997;185:263–271. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.2.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ogasawara J, et al. Selective apoptosis of CD4+CD8+ thymocytes by the anti-Fas antibody. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1995;181:485–491. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.2.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lucas B, et al. Divergent changes in the sensitivity of maturing T cells to structurally related ligands underlies formation of a useful T cell repertoire. Immunity. 1999;10:367–376. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Davey GM, et al. Preselection thymocytes are more sensitive to T cell receptor stimulation than mature T cells. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1998;188:1867–1874. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.10.1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pircher H, et al. Lower receptor avidity required for thymic clonal deletion than for effector T-cell function. Nature. 1991;351:482–485. doi: 10.1038/351482a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hogquist KA, et al. T cell receptor antagonist peptides induce positive selection. Cell. 1994;76:17–27. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li QJ, et al. miR-181a is an intrinsic modulator of T cell sensitivity and selection. Cell. 2007;129:147–161. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang D, et al. Tespa1 is involved in late thymocyte development through the regulation of TCR-mediated signaling. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:560–568. doi: 10.1038/ni.2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lo WL, et al. A voltage-gated sodium channel is essential for the positive selection of CD4(+) T cells. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:880–887. doi: 10.1038/ni.2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Singer A, et al. Lineage fate and intense debate: myths, models and mechanisms of CD4- versus CD8-lineage choice. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2008;8:788–801. doi: 10.1038/nri2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu X, Bosselut R. Duration of TCR signaling controls CD4-CD8 lineage differentiation in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:280–288. doi: 10.1038/ni1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Starr TK, et al. Positive and negative selection of T cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:139–176. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Klein L, et al. Positive and negative selection of the T cell repertoire: what thymocytes see (and don’t see) Nature reviews. Immunology. 2014;14:377–391. doi: 10.1038/nri3667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bassing CH, et al. The mechanism and regulation of chromosomal V(D)J recombination. Cell. 2002;109(Suppl):S45–55. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00675-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chung S, et al. Serrano (sano) functions with the planar cell polarity genes to control tracheal tube length. PLoS genetics. 2009;5:e1000746. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tonks NK. Redox redux: revisiting PTPs and the control of cell signaling. Cell. 2005;121:667–670. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chiarugi P, Cirri P. Redox regulation of protein tyrosine phosphatases during receptor tyrosine kinase signal transduction. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:509–514. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]