Abstract

The size‐tunable emission of luminescent quantum dots (QDs) makes them highly interesting for applications that range from bioimaging to optoelectronics. For the same applications, engineering their luminescence lifetime, in particular, making it longer, would be as important; however, no rational approach to reach this goal is available to date. We describe a strategy to prolong the emission lifetime of QDs through electronic energy shuttling to the triplet excited state of a surface‐bound molecular chromophore. To implement this idea, we made CdSe QDs of different sizes and carried out self‐assembly with a pyrene derivative. We observed that the conjugates exhibit delayed luminescence, with emission decays that are prolonged by more than 3 orders of magnitude (lifetimes up to 330 μs) compared to the parent CdSe QDs. The mechanism invokes unprecedented reversible quantum dot to organic chromophore electronic energy transfer.

Keywords: energy transfer, luminescence, nanoparticles, phosphorescence, triplet sensitization

Quantum Dots (QDs) are nanostructured materials with unique photophysical properties that are not observed in their parent ‐bulk material, such as broad‐band absorption spectra with very high absorption cross‐section and high luminescence quantum yield, longer luminescence lifetimes in comparison with many popular fluorophores, high photostability, and size‐dependent emission spectra.1, 2 Combining photoactive QDs with molecular chromophores3 may be used to modify observed QD properties without recourse to redesigning new composites, providing there is significant QD–molecule interplay. The resulting inorganic–organic hybrids are of high interest for applications in photovoltaic, lighting, and sensing devices.3, 4

Previously, we reported core–shell CdSe‐ZnS QDs surface‐functionalized with pyrene ligands, which showed that the two components behaved orthogonally within the conjugate, retaining their individual characteristics. This allowed them to be exploited as nano‐objects for luminescence‐based ratiometric determination of O2 concentration.5, 6 Interestingly, it was recently shown that core CdSe QDs (lacking the ZnS barrier) allowed QD–organic chromophore interaction through an interfacial unidirectional Dexter‐like triplet–triplet energy transfer towards surface‐anchored polyaromatic carboxylic acid acceptors, thereby acting as a photosensitizer and populating a long‐lived aromatic organic triplet.7 Energy transfer in the reverse direction, that is, from organic triplets to interfaced PbSe and PbS QDs, was also demonstrated.8

In this work, we sought to obtain novel nanoconjugate behavior by fine‐tuning the QD excitonic level (in the absence of a shell) such that it is quasi‐isoenergetic with long‐lived triplet levels of surface‐anchored organic chromophores (Figure 1), which could represent a general strategy to dramatically modify excited QD properties, particularly in terms of modifying luminescence properties. Notably, a new set of parameters would be obtained for QDs of a given composition and size.

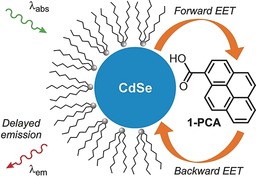

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the QD–pyrene conjugates and the investigated processes.

Specific energetic and kinetic criteria that need to be satisfied are: 1) close energetic proximity between low‐lying excited‐state energy levels on the QD and chromophore (ΔE≤1000 cm−1); and 2) relatively fast intercomponent energy transfer with respect to other deexcitation pathways. On fulfilling these conditions, reversible electronic energy transfer (REET) between chromophores may in principle be allowed and, in analogy with molecular bichromophoric species, would greatly modify the excited‐state properties.9, 10, 11 Figure 1 shows a representation of the envisaged target nanoconjugates, which are CdSe‐based core QDs of a specific designated size, capped with alkyl surfactants and decorated with 1‐pyrenecarboxylic acid (1‐PCA).

Indeed, pyrene, which has a long‐lived triplet state (τ≈10 ms, 2.1 eV) that is largely insensitive to its environment, is the organic chromophore of choice in the current work, while carboxylate groups have proven effective in anchoring chromophores on different nanoparticles.6, 12

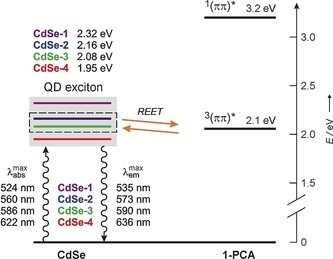

Different batches of hydrophobic QDs were synthesized according to the method developed by Maitra and co‐workers13 and subsequently decorated with 1‐PCA, as described in the Supporting Information. Particular care was taken to isolate QDs with suitable sizes in order to satisfy the energetic criteria for the REET to take place. Specifically, four different samples of QDs (CdSe‐1, CdSe‐2, CdSe‐3, and CdSe‐4) were prepared and investigated (Figure 2). The average number of pyrene units per nanoparticle depends on the size of the latter, and ranges from 68 for CdSe‐1 to 300 for CdSe‐4.

Figure 2.

Energy‐level diagram for CdSe QDs decorated with 1‐PCA. CdSe‐2 and CdSe‐3 exhibit reversible electronic energy transfer (REET) involving their excitonic level and the energy‐matched triplet excited state of 1‐PCA. The excitonic levels of CdSe‐1 and CdSe‐4 are too high and too low, respectively, for REET to occur at RT.

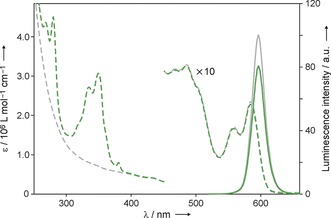

In all cases the UV/Vis absorption spectra of the conjugates correspond to the sum of the QD and pyrene chromophoric components, thus indicating the absence of strong electronic interactions in the ground state (Figure 3). It is important to note that the absorption onset of 1‐PCA is at 390 nm, and thus the absorption of photons with longer wavelengths affords selective excitation of the nanocrystal component.

Figure 3.

Absorption (dashed lines, left scale) and luminescence (full lines, right scale; λ exc=500 nm) spectra of CdSe‐3 (gray traces) and CdSe‐3@1‐PCA (green traces) in air‐equilibrated heptane at RT (C=2.1×10−7 mol L−1). Each nanoparticle is decorated with 90±7 pyrene units on average.

The presence of 1‐PCA does not significantly affect the maximum and profile of the emission band of the various QD samples, but it causes a decrease in its intensity (Table 1). Such quenching can be ascribed to less efficient surface passivation afforded by the carboxylate ligands in comparison with the native caps and, in the case of CdSe‐1, also to unidirectional energy transfer to the pyrene triplet state. It is noteworthy that all of the QD batches maintain intense luminescence after decoration with 1‐PCA (Table 1).

Table 1.

Luminescence properties of the QDs samples at RT.

| Air‐equilibrated heptane | Deoxygenated heptane | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Φ [a] | τ [ns] (F)[b] | Φ [a] | τ [ns] (F)[b] |

| CdSe‐1 | 0.18 | 133 (32 %) | 0.18 | 133 (35 %) |

| CdSe‐1 @1‐PCA | 0.04 | 70 (26 %) | 0.04 | 73 (34 %) |

| CdSe‐2 | 0.16 | 76 (24 %) | 0.16 | 76 (21 %) |

| CdSe‐2 @1‐PCA | 0.04 | 66 (20 %) | 0.04 | 3.3×105 (1.5 %)[c] |

| CdSe‐3 | 0.57 | 84 (10 %) | 0.57 | 89 (10 %) |

| CdSe‐3 @1‐PCA | 0.44 | 104 (11 %) | 0.46 | 2.1×105 (1.8 %)[c] |

| CdSe‐4 | 0.03 | 37 (26 %) | 0.03 | 37 (25 %) |

| CdSe‐4 @1‐PCA | 0.01 | 41 (27 %) | 0.01 | 40 (31 %) |

[a] Luminescence quantum yield. [b] Luminescence lifetime measured by time‐correlated single‐photon counting, unless otherwise noted. For simplicity, only the longest component of the luminescence decay is reported; the fractional contribution (F) to the overall decay is shown in parentheses. Complete data are available in the Supporting Information. [c] Measured by gated streak camera upon ps laser excitation.

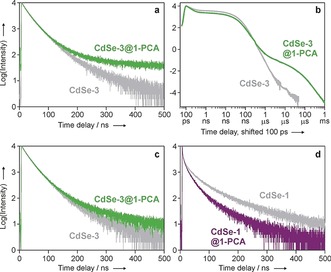

Remarkable differences, however, were observed in the time‐dependent luminescence properties of the various QD samples, and in the effect of dissolved oxygen on the emission decays (Table 1 and Figure 4). In line with literature reports, all of the bare QDs exhibit multiexponential emission decays in the 10–100 ns range, which could be satisfactorily fitted with a tri‐exponential function, and are virtually unaffected by dissolved oxygen. When CdSe‐2 and CdSe‐3 are decorated with 1‐PCA, a component in the 100 μs domain appears in their luminescence decay measured in deoxygenated heptane solution (Figure 4 a,b). Such a long‐lived component is not detected in air‐equilibrated solution (Figure 4 c). From the analysis of the decay curves, we estimate that the fraction of the long‐lived photons over the total emitted photons is about 1.5 % and 1.8 % for CdSe‐2@1‐PCA and CdSe‐3@1‐PCA, respectively.

Figure 4.

Luminescence decay, monitored at 600 nm, of CdSe‐3 (gray trace) and CdSe‐3@1‐PCA (green trace) in deoxygenated heptane solution at RT, as measured by a) time‐correlated single‐photon counting (log plot, λ exc=405 nm) and b) gated streak camera (log‐log plot, λ exc=465 nm). c) Luminescence decay of CdSe‐3 QDs, with and without 1‐PCA, in air‐equilibrated heptane. d) Luminescence decay of CdSe‐1 QDs, monitored at 540 nm, with and without 1‐PCA, in deoxygenated heptane. The data in panels (c) and (d) were obtained by single‐photon counting upon 405 nm excitation at RT.

Conversely, modification of CdSe‐1 and CdSe‐4 with 1‐PCA does not cause significant changes in their emission decay kinetics in deoxygenated (Figure 4 d) or air‐equilibrated solutions, and a long‐lived component is not observed.

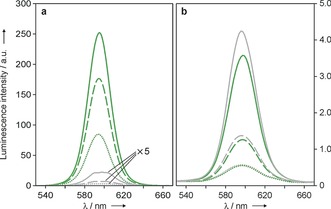

To gain further evidence of the presence of a long‐lived component in the nanocrystal emission for CdSe‐2 and CdSe‐3 decorated with 1‐PCA, we recorded time‐gated luminescence spectra in deoxygenated conditions. For the CdSe‐3‐based conjugates, the QD emission can still be clearly detected 100 μs after the excitation pulse when the pyrene chromophore is present (Figure 5 a). Conversely, the emission of the same QDs lacking the 1‐PCA ligand can be barely seen even at a delay of 40 μs. In air‐equilibrated solution the emission intensity of the CdSe‐3‐based QDs, observed in the 100‐μs range, is very weak and is independent on the presence of the pyrenyl ligand (Figure 5 b), thus confirming that dissolved oxygen selectively quenches the long‐lived emission component without affecting the intrinsic luminescence of the nanocrystal.

Figure 5.

Luminescence spectra of optically matched solutions of CdSe‐3@1‐PCA (green traces) and CdSe‐3 (gray traces) in deoxygenated (a) and air‐equilibrated (b) heptane, recorded at different delay times (full lines, 40 μs; dashed lines, 80 μs; dotted lines, 100 μs) upon pulsed excitation at 500 nm.

These results are fully consistent with REET between the nanocrystal and the organic chromophore. The excitation energy can be stored in the long lived organic triplet state and shuttled back to the QD exciton, thereby extending its lifetime. Clearly, O2 quenches the pyrenyl‐centered triplet excited state populated by energy transfer from the QD exciton, thus preventing the reverse transfer and interrupting the shuttling mechanism. Unfortunately, experiments aimed at probing the transient absorption of the lowest triplet excited state of 1‐PCA upon excitation of the QD were unfruitful, most likely because of the very low energy‐transfer efficiency.

It is known that the excitonic levels responsible for the CdSe QD emission (bright states) have a singlet character, and that triplet levels (often referred to as the “dark exciton”) lie a few meV below the bright states.14 It is reasonable to assume that these triplet excitons are responsible for the Dexter‐type energy transfer to and from the pyrene triplet level in our conjugates (Figure 2 is simplified in this regard). Since the Dexter mechanism relies on orbital overlap and its efficiency is exponentially dependent on donor–acceptor distance,15 a close proximity of the pyrene moiety to the CdSe surface is most likely an additional crucial requirement for the observation of REET. Such a requirement is met in our conjugates thanks to the short length of the ligand and the absence of an inorganic shell (e.g., ZnS). Indeed, the fact that core–shell CdSe‐ZnS QDs decorated with 1‐PCA and with the same core diameter of CdSe‐3 do not exhibit an emission component decaying in the μs domain is consistent with this hypothesis.

In summary, compelling evidence is presented for both initial quantum dot to pyrene energy transfer and the subsequent return process in an energetically matched chromophore pair (as in the case of CdSe‐2 and CdSe‐3), compared both to analogues without the organic chromophore and to different nanocrystals with a raised (CdSe‐1) or lowered (CdSe‐4) excitonic level with respect to the lowest triplet excited state of 1‐PCA. Reversible interconjugate energy shuttling was engineered in a predetermined fashion based on knowledge of energy levels and quantum dot and pyrene triplet decay kinetics, on allowing close approach of the two constituent chromophores. The result is long‐lived luminescence, which is desirable for gated detection. The ample choice of organic chromophores16 and fine tuning of the QD exciton energy ensures high flexibility.

The presented approach enables the preparation of QDs with the same emission maximum and bandshape but different lifetimes, thus adding a new potential dimension to multiplexed detection.17 Moreover, a luminescent response for molecular oxygen can be implemented with nanocrystals that are inherently insensitive to O2. The strategy presented here provides opportunities for fundamental research on as‐yet poorly investigated triplet energy transfer in inorganic–organic nanoconjugates,4a and discloses new perspectives for tailoring optical properties in a wealth of nanomaterials.18

In memory of Ugo Mazzucato

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

Financial support from the European Union (H2020‐ERC Advanced Grant “Leaps” no. 692981, and FP7‐NMP grant “Hysens” no. 263091) and the Università Italo‐Francese (Vinci fellowship to M.L.R.) is gratefully acknowledged.

M. La Rosa, S. A. Denisov, G. Jonusauskas, N. D. McClenaghan, A. Credi, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 3104.

Contributor Information

Dr. Gediminas Jonusauskas, Email: gediminas.jonusauskas@u-bordeaux.fr

Dr. Nathan D. McClenaghan, Email: nathan.mcclenaghan@u-bordeaux.fr.

Prof. Dr. Alberto Credi, Email: alberto.credi@unibo.it.

References

- 1.

- 1a. Alivisatos A. P., J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 13226–13239; [Google Scholar]

- 1b. Talapin D. V., Lee J.-S., Kovalenko M. V., Shevchenko E. V., Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 389–458; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1c. Pietryga J. M., Park Y.-S., Lim J., Fidler A. F., Bae W. K., Brovelli S., Klimov V. I., Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 10513–10622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Photoactive Semiconductor Nanocrystal Quantum Dots—Fundamentals and Applications (Ed.: A. Credi), Springer, Basel, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.

- 3a. Somers R. C., Bawendi M. G., Nocera D. G., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007, 36, 579–591; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3b. Medintz I. L., Mattoussi H., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2009, 11, 17–45; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3c. Yildiz I., Erhan D., Raymo F. M., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 1859–1867; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3d. Aguilera-Sigalat J., Pais V. F., Domenech-Carbo A., Pischel U., Galian R. E., Perez-Prieto J., J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 7365–7375; [Google Scholar]

- 3e. Silvi S., Credi A., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 4275–4289; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3f. Harris R. D., Homan S. B., Kodaimati M., He C., Nepomnyashchii A. B., Swenson N. K., Lian S., Calzada R., Weiss E. A., Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 12865–12919; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3g. Hildebrandt N., Spillmann C. M., Algar W. R., Pons T., Stewart M. H., Oh E., Susumu K., Diaz S. A., Delehanty J. B., Medintz I. L., Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 536–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.

- 4a. Bardeen C. J., Nat. Mater. 2014, 13, 1001–1003; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4b. Huang Z., Li X., Mahboub M., Hanson K. M., Nichols V. M., Le H., Tang M. L., Bardeen C. J., Nano Lett. 2015, 15, 5552–5557; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4c. Wu M., Congreve D. N., Wilson M. W. B., Jean J., Geva N., Welborn M., Van Voorhis T., Bulović V., Bawendi M. G., Baldo M. A., Nat. Photonics 2016, 10, 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Amelia M., Lavie-Cambot A., McClenaghan N. D., Credi A., Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 325–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. González-Carrero S., de la Guardia M., Galian R. E., Pérez-Prieto J., ChemistryOpen 2014, 3, 199–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.

- 7a. Mongin C., Garakyaraghi S., Razgoniaeva N., Zamkov M., Castellano F. N., Science 2016, 351, 369–372; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7b. Garakyaraghi S., Mongin C., Granger D. B., Anthony J. E., Castellano F. N., J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2017, 8, 1458–1463; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7c. Xia P., Huang Z., Li X., Romero J. J., Vullev V. I., Pau G. S. H., Tang M. L., Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 1241–1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.

- 8a. Tabachnyk M., Ehrler B., Gélinas S., Böhm M. L., Walker B. J., Musselman K. P., Greenham N. C., Friend R. H., Rao A., Nat. Mater. 2014, 13, 1033–1038; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8b. Thompson N. J., Wilson M. W. B., Congreve D. N., Brown P. R., Scherer J. M., Bischof T. S., Wu M., Geva N., Welborn M., Van Voorhis T., Bulović V., Bawendi M. G., Baldo M. A., Nat. Mater. 2014, 13, 1039–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reviews:

- 9a. Lavie-Cambot A., Lincheneau C., Cantuel M., Leydet Y., McClenaghan N. D., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 506–515; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9b. Wang X. Y., Del Guerzo A., Schmehl R. H., J. Photochem. Photobiol. C 2004, 5, 55–77; [Google Scholar]

- 9c. McClenaghan N. D., Leydet Y., Maubert B., Indelli M. T., Campagna S., Coord. Chem. Rev. 2005, 249, 1336–1350. [Google Scholar]

- 10.

- 10a. Denisov S. A., Gan Q., Wang X., Scarpantonio L., Ferrand Y., Kauffmann B., Jonusauskas G., Huc I., McClenaghan N. D., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 1328–1333; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 1350–1355; [Google Scholar]

- 10b. Denisov S., Cudré Y., Verwilst P., Jonusauskas G., Marín-Suárez M., Fernandez-Sanchez J., Baranoff E., McClenaghan N. D., Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 2677–2682; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10c. Ragazzon G., Verwilst P., Denisov S. A., Credi A., Jonusauskas G., McClenaghan N. D., Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 9110–9112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.

- 11a. Ford W. E., Rodgers M. A. J., J. Phys. Chem. 1992, 96, 2917–2920; [Google Scholar]

- 11b. Passalacqua R., Loiseau F., Campagna S., Fang Y.-Q., Hanan G. S., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 1608–1611; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2003, 115, 1646–1649; [Google Scholar]

- 11c. McCusker C. E., Chakraborty A., Castellano F. N., J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118, 10391–10399; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11d. Yi C., Xu S. X., Wang J. L., Zhao F., Xia H. Y., Wang Y. B., Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 4885–4890. [Google Scholar]

- 12.See, e.g.:

- 12a. Sykora M., Petruska M. A., Alstrum-Acevedo J., Bezel I., Meyer T. J., Klimov V. I., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 9984–9985; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12b. Ren T., Mandal P. K., Erker W., Liu Z., Avlasevich Y., Puhl L., Müllen K., Basché T., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 17242–17243; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12c. Zhu H., Song N., Lian T., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 15038–15045; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12d. Comesaña-Hermo M., Estivill R., Ciuculescu D., Amiens C., Batat P., Jonusauskas G., McClenaghan N. D., Lecante P., Tardin C., Mazeres S., ChemPhysChem 2011, 12, 2915; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12e. Zhang L., Cole J. M., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 3427–3455; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12f. De Roo J., Ibanez M., Geiregat P., Nedelcu G., Walravens W., Maes J., Martins J. C., Van Driessche I., Koyalenko M. V., Hens Z., ACS Nano 2016, 10, 2071–2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chakrabarty A., Chatterjee S., Maitra U., J. Mater. Chem. C 2013, 1, 2136–2144. [Google Scholar]

- 14.

- 14a. Nirmal M., Norris D. J., Kuno M., Bawendi M. G., Efros A. L., Rosen M., Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995, 75, 3728–3731; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14b. Leung K., Pokrant S., Whaley K. B., Phys. Rev. B 1998, 57, 12291–12301; [Google Scholar]

- 14c. Underwood D. F., Kippeny T., Rosenthal S. J., J. Phys. Chem. B 2001, 105, 436–443; [Google Scholar]

- 14d. Clapp A. R., Medintz I. L., Mattoussi H., ChemPhysChem 2006, 7, 47–57; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14e. Russ Algar W., Kim H., Medintz I. L., Hildebrandt N., Coord. Chem. Rev. 2014, 263–264, 65–85. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Photochemistry and Photophysics: Concepts, Research, Applications (Eds.: V. Balzani, P. Ceroni, A. Juris), Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Handbook of Photochemistry (Eds.: M. Montalti, A. Credi, L. Prodi, M. T. Gandolfi), CRC Press, Boca Raton, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 17.

- 17a. Howes P. D., Chandrawati R., Stevens M. M., Science 2014, 346, 53; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17b. Wegner K. D., Hildebrandt N., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 4792–4834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.While this paper was under review, an article describing similar results was published: Mongin C., Moroz P., Zamkov M., Castellano F. N., Nat. Chem. 2018, 10, 225–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary