Abstract

Complex 3D organizations of materials represent ubiquitous structural motifs found in the most sophisticated forms of matter, the most notable of which are in life-sustaining hierarchical structures found in biology, but where simpler examples also exist as dense multilayered constructs in high-performance electronics. Each class of system evinces specific enabling forms of assembly to establish their functional organization at length scales not dissimilar to tissue-level constructs. This study describes materials and means of assembly that extend and join these disparate systems—schemes for the functional integration of soft and biological materials with synthetic 3D microscale, open frameworks that can leverage the most advanced forms of multilayer electronic technologies, including device-grade semiconductors such as monocrystalline silicon. Cellular migration behaviors, temporal dependencies of their growth, and contact guidance cues provided by the nonplanarity of these frameworks illustrate design criteria useful for their functional integration with living matter (e.g., NIH 3T3 fibroblast and primary rat dorsal root ganglion cell cultures).

Keywords: 3D scaffolds, cellular contact guidance, compressive-assembly, direct ink writing, hydrogels

1. Introduction

Established methods in micro/nanofabrication have the capacity to form diverse classes of functional microsystems technologies, where function and performance are defined by the physical and chemical attributes of the constituent materials and by the dense, layered architectures of the design layouts. Such systems represent the most compelling examples that exist in high-performance/integration density electronics,[1] energy storage,[2] actuators and sensors,[3] and photonics and optoelectronics.[4] The means of fabrication and the materials used in these cases are very different from those in biology, which are largely based on exceptionally complex forms of materials integration, where broad ranges of hard and soft materials are arranged into elaborate, fully 3D architectures. Advances in technology that conjoin the most advanced classes of materials found in state-of-the-art, man-made microsystems with soft, living matter demand approaches to devices that mimic natural tissue 3D hierarchies and render them robustly biologically permissive. The present work addresses these interests.

Controlling cellular behavior and directing the development of tissue is important for both tissue engineering and bioelectronics applications. Contact guidance, a deeply studied property of planar supported cultures, is characterized by cellular responses (e.g., migration, elongation, alignment, proliferation, or initiation of cell death) to microscale topographical features and structures within their local environments.[5] Techniques such as photolithography, electron-beam writing, sublimation-based nanostructuring, and electrospinning underpin numerous exemplars of 2D topographical patterns across a wide range of materials (e.g., silicones, epoxies, semiconductors, organic polymers) that act to induce elongation, migration guidance, and cytoskeletal reorganization of cells cultured on them.[6] Micro/nanopillar and nanowell arrays, randomized geometries, sinusoid curves, roughened surfaces, as well as numerous strain-based assemblies (with feature lengths that can range from 10 nm up to tens of microns) are known to manifest contact guidance properties that also can control cellular adhesion and elongation.[7] A key limitation of these materials systems is that their overall planar confinement of cells is far-removed from the 3D hierarchical and structural environments that are the currency of living systems.

Strategies for fabricating 3D biomimetic scaffolds that contain microporous or microfilamentous structures at cellular-active scales typically rely on polymers patterned through stereolithographic methods or direct laser writing (DLW), methods of controlled microporosity such as gas foaming and porogen leaching, and additive manufacturing methods such as 3D inkjet printing, fused deposition modeling, selective laser sintering, electrospinning and direct ink writing (DIW).[8] Such scaffolds can replicate natural tissue architectures, but they cannot integrate advanced materials or devices found in high-performance electronics or optoelectronics, of potential revolutionary use in monitoring, stimulating or guiding the growth, proliferation and/or migration of living cells and tissues. Recent reports attempt to address this limitation through the use of chemically synthesized nanomaterials, such as graphene sheets and silicon (Si) nanowires.[9] The most recent examples of the latter involve microporous mesh structures where the nanowires offer advanced functionality in sensors and actuators.[10] Although important benchmarks in integration, these systems have key limitations that follow from their reliance on (1) classes of semiconductor nanomaterials and device structures that are unable to leverage the most successful concepts in planar microsystems technologies; and (2) routes to 3D microarchitectures in which mechanical rolling processes yield randomized scaffolds that are unable to include full deterministic control over geometric parameters or topologies of interest.

The work reported here represents an important set of advances that exploit 3D microscale open frameworks formed spontaneously from advanced materials, including device-grade semiconductors such as monocrystalline Si. Here, elastomeric substrates impart forces that lead to a well-defined process of geometric transformation from 2D to 3D, with a diverse set of control parameters.[11] Expanding upon these previously established concepts to yield structures that we refer to as 3D micro-scale cellular frameworks (3D μ-CFs), DIW affords a means to either introduce, using straightforward procedures applied to the 2D precursor structure, growth compliant soft materials for cell integration, or to directly introduce and localize cells. Specifically, DIW with thixotropic gels amenable to extrusion (i.e., “inks”) such as synthetic or natural hydrogels, yields bio-compatible soft materials permanently affixed to 3D μ-CFs via chemical bonding during polymerization or transiently applied for localized cell deposition.

These methods afford 3D μ-CFs that can support and direct cellular and tissue-level cultures with unique properties that include curvilinear forms, true terminating edges without sidewalls, broad variations of supporting feature widths (from the order of the dimensions of single cells to more extended areal layouts), geometrically controllable 3D placements of features (ranging proximally to distances that only self-supporting tissue-level cell constructs can bridge), and (most intriguingly) capacities to support cell growth on the adjoined faces of the supporting membrane scaffold frameworks. The systems explored are ones that emphasize materials classes of direct interest for devices that would allow the integration of electronic forms of functionality into the out-of-plane features of the 3D μ-CF scaffolds (e.g., advanced sensors, actuators, and electrodes for neural electrophysiology, applications exploiting the current work and under current study).[12] We further examine design rules wherein passive perfusion provides stable transport regimes for sustaining cells in culture, obviating the requirement for active media renewal that is typically provided by vascular networks.[13]

A systematic set of studies shows that 3D contact guidance cues present between the cells (fibroblasts and dorsal root ganglion (DRG) cells) and the functionalized 3D μ-CFs on which they grow yield 3D cellular integration outcomes that depend both on the local geometry and aspect ratio of the scaffolds, which in turn yield specific alignment, elongation, and other organizational behaviors that evolve with culture time. In the case of DRG organotypic cultures, the additional factor of strain gradients that develop within the 3D tissue constructs is evidenced by distinct growth motifs (DRG-mimetic clusters, high tension fibers, and cellular sheaths) whose forms arise as a unique consequence of their 3D scaffolds environment. The guidance cues provided in these contexts are ones not necessarily expected to mimic the structures associated with natural 3D extracellular protein networks, but instead to follow in consequence of open framework microarchitectures innate to this class of scaffold. This work reveals features of these mediating design rules, ones developed in detail in the sections that follow.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Design Rules for Biointegration onto 3D α-CFs

The dimensional attributes of the 3D μ-CFs presented in this work are selected because of their corollaries with particular aspects of cellular cultures. Generally, in order to study the contact guidance properties of these scaffold geometries, 3D μ-CF ribbon widths ranging from 2 to 10× the width of a spreading fibroblast are ideal (depending on the spreading aspect ratio of the fibroblast) since it is known that cells in planar cultures need to be developing relatively proximal to structural features in order to be influenced by their geometric cues.[7a–e] We consider 3D μ-CFs with these geometries “high alignment contact guidance” environments (e.g., solenoids). To contrast with these scaffolds, we also fabricate structures that incorporate geometric aspect ratio regions on which the majority of cells grow too far away from edge features to be aligned or influenced substantively by the scaffold geometry itself. For fibroblast cultures, these are considered “low alignment contact guidance” environments (e.g., tables).

In the case of tissue-level DRG cell integration, the role of 3D μ-CF geometries is somewhat different. DRG cell cultures seek to reorganize into clusters of neuronal cell bodies and develop tensile cell extension bundles that interconnect those clusters. The role of the 3D μ-CF consequently should be one of spatially programmed anchoring intersection points and double-sided growth surfaces, which is the design rule of merit used when selecting geometries for DRG applications. DRG cell clusters can in fact be several hundred microns in size as well, due to the number of large neuronal bodies assembling within them, so it becomes important to provide an on-scaffold surface that is large enough to accommodate these cell morphologies. It is unclear prior to 3D DRG cell culture experiments as to what degree the high tensile strain that is known to develop within cellular extension bundles will affect the maintenance of registry between DRC cell structures and their guiding 3D μ-CFs.[14] For this reason, a series of table scaffolds are prepared that vary their degree of support as well as the size and geometry of their aerial intersection region so that we may directly study this property.

Many of the outcomes drawn in this survey of cellular behaviors on 3D μ-CFs directly compare solenoids to tables; however, a key capability of this class of scaffold is the accessibility of numerous diverse scaffold geometries with distinct curvature, intercontact distances, microribbon widths, etc. Because the Si devices are prepared from silicon on insulator (SOI) wafers with a 1.2 μm device layer thickness, all ribbons from this material share that dimensional attribute while the SU8 device ribbons are 10 μm in thickness. Previously, we reported a ratio of κtwist/κbend that is calculated using finite-element analysis (FEA) to designate a curvature value, R, for scaffolds of interest. FEA predictions are also used to illustrate how all 3D μ-CFs successfully assemble because their final strain is <1%, with most scaffolds peaking at ≈0.7% at their point of greatest curvature or inflection points of their 2D geometries. Table 1 lists all 3D μ-CF dimensions and their first in-text reference (where applicable, scaffold names are given as they appear in our previous work)[11a] that are herein examined in various contexts of compressive assembly-assisted DIW gel printing or cellular integration.

Table 1.

Intercontact distances and dimensional analyses of 3D μ-CF structures used for cellular culture.

| Material | 3D μ-CF Structure | Figure | Length (2D) | Width (2D) | Height (3D) | Ribbon depth | Ribbon width | Inter-contact (adj)a) | Inter-contact (opp)b) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silicon | Double floor helix | 1b-1 | 4540 | 2210 | 500 | 1.2 | 60 | 1280 | 2550 |

| Solenoid | 1b-2 | 28600 | 700 | 500 | 1.2 | 100 | 1834 | – | |

| Dumbbell (scaffold) R = 0 | 1b-3 | 2210 | 1210 | 700 | 1.2 | 50 | 750 | 2230 | |

| Peacock | 1b-4 | 1710 | 1210 | 800 | 1.2 | 50 | 1150 | 1270 | |

| Circular helix I R = 0.89 | S1d | 1520 | 1520 | 500 | 1.2 | 80 | 1030 | 2180 | |

| Switchback | S2a | 4210 | 1210 | 500 | 1.2 | 50 | 770 | 2240 | |

| Coil on gallery | S2c | 14210 | 1210 | 600 | 1.2 | 50 | 790 | 2010 | |

| Grid bridge | 1d | 2470 | 2700 | 500 | 1.2 | 50 | 1565 | 1900 | |

| Box II R = 0.16 | 1e | 1980 | 1980 | 500 | 1.2 | 50 | 780 | 1210 | |

| Solenoid Narrow | 2a | 28600 | 660 | 500 | 1.2 | 60 | 1854 | – | |

| Solenoid Medium | 2a | 28600 | 700 | 500 | 1.2 | 100 | 1834 | – | |

| Solenoid Wide | 2a | 28600 | 740 | 500 | 1.2 | 140 | 1810 | – | |

| Table R = 0 | 3a | 2000 | 2000 | 800 | 1.2 | 70 | 1670 | 2130 | |

| Tent R = 0 | S7 | 1600 | 1600 | 800 | 1.2 | 50 | 800 | 800 | |

| Channel table R = 0 | S14 | 2720 | 2720 | 800 | 1.2 | 70 | 1760 | 2130 | |

| Double floor helix array | S22 | 7370 | 7370 | 500 | 1.2 | 40 | 1300 | 2700 | |

| Triple-floor building | S28a | 3410 | 2210 | 600 | 1.2 | 50 | 760 | 1510 | |

| Inverted flower II | S28b | 1770 | 1770 | 500 | 1.2 | 80 | 1135 | 2400 | |

| Star R = 0.36 | S29 | 3300 | 3300 | 600 | 1.2 | 100 | 1280 | 2720 | |

| Tent array R = 0 | S30 | 4800 | 4800 | 800 | 1.2 | 50 | 360 | 630 | |

| 4 Point flower R = 0.11 | S32 | 1130 | 1130 | 500 | 1.2 | 80 | 1135 | 2360 | |

| Three-layer flower | S33 | 5670 | 5670 | 500 | 1.2 | 60 | 1439 | 1456 | |

| Circular helix II R = 1.07 | S34 | 3560 | 3560 | 400 | 1.2 | 60 | 1130 | – | |

| Two-layer flower | S36 | 3050 | 2440 | 700 | 1.2 | 50 | 1455 | – | |

| Table array R = 0 | S38 | 7930 | 7930 | 800 | 1.2 | 50 | 1670 | 2130 | |

|

| |||||||||

| SU8 | Table IR = 0 | S47 | 2000 | 2000 | 800 | 10 | 50 | 1071 | 1199 |

| Table legs R = 0 | 4d | 1600 | 1600 | 800 | 10 | 50 | 755 | 800 | |

| Mini table R = 0 | 4d | 2000 | 2000 | 800 | 10 | 50 | 1097 | 1215 | |

| Open table R=0 | 4d | 2000 | 2000 | 800 | 10 | 50 | 1086 | 1384 | |

adj = adjacent;

opp = opposite.

2.2. Heterogeneous Soft Materials Integration with 3D Si α-CFs

DIW using thixotropic gels amenable to extrusion (i.e., “inks”) such as synthetic or natural hydrogels, yields biocompatible soft materials permanently affixed to 3D μ-CFs via chemical bonding during polymerization or transiently applied for localized cell deposition. As an example of functional chemical integration, inks for two model hydrogel materials—ones of interest due to their varying utility for biocompatibility and chemomechanical actuation—are printed by DIW onto 2D lithographic μ-CF patterns prepared on prestrained elastomeric substrates and then self-assembled into their 3D forms by strain release (Figure 1). A surface modification of the Si patterns with a silyl methacrylate coupling reagent is required to promote adhesive bonding (Figure 1a-1). The various hydrogel inks are printed in registry with the 2D Si patterns using a 10 μm capillary tip (Figure 1a-2). Prestrain release in the substrate buckles the Si μ-CF/polymer hybrid bilayer devices into their proscribed 3D geometries followed by a final UV-induced polymerization to covalently bond them together (Figure 1a-3).

Figure 1.

Deterministic integration of hydrogels onto 3D microscaffolds. a) Schematics of direct ink writing (DIW) hydrogels onto, e.g., compressively buckled Si μ-CFs consisting of (1) silyl methacrylate surface treatment during transfer printing, (2) printing methacrylate-based hydrogel pre-polymer gels onto 2D μ-CFs on prestrained elastomers, and (3) releasing prestrain buckles the scaffolds and the UV treatment cures the hydrogel into place. b) Scaffold pattern schematics (orange bonded contacts, blue free-assembling scaffold) and corresponding colorized SEM images of hydrogel/μ-CF hybrid devices (HEMA hydrogel in red, scaffold in blue, substrate in yellow; scale bars 200 μm for 1,2,4; 50 μm for 3). c) HEMA (red) or NIPAM (green) monomers incorporated into printable hydrogel inks, resulting in d) the schematic and colorized image of hydrogel networks hybridized onto compressively buckled 300 nm Au ribbon patterns (scale bar 200 μm), and e,f) schematics (left) and confocal fluorescence data (right) for representative scaffold geometries patterned with HEMA and NIPAM-based hydrogel bilayer gradients (scale bars e)100 μm; f) 500 μm).

The additive modifications of materials patterning afforded by DIW extend to diverse μ-CF geometries, as illustrated in the representative poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) (pHEMA)-based bilayer scaffolds shown in Figure 1b. Multiple hydrogel filaments can be printed and affixed to the Si patterns as illustrated here for inks using the monomers N-isopropyl acrylamide (NIPAM, shown in green)—that yields a material poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (pNIPAM) for use in hydrogel-based programmable actuators[3a]—and 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA, shown in red)—that yields a pHEMA material that allows for tuning cellular adhesion modes (Figure 1c).[15] The capacity to construct polymeric overlayers that bridge, span, or variously interconnect the μ-CF is enabled by DIW and is illustrated in Figure 1d by pHEMA hydrogel mesh that uses the underlying scaffold features as a structural reinforcement. In the example shown, strain release leads to 3D motifs in the hydrogel that follow (and add to) the induced buckling modes (shown schematically in Figure 1d, left, and with colorized light micrographs, Figure 1d, right). Additional bilayer images, ink chemistries, and exemplary structures are shown in Supporting Information 1–3.

The methods described above allow a general approach to hybrid 3D μ-CF construction that embeds complex gradient forms and that is complementary to recent advances in local functionalization of soft polymer materials via DLW in that the limit of localized resolution is defined in this case by the smallest bead diameter that can be extruded by a pulled glass capillary printing tip.[16] While in both DLW and compressive assembly-assisted DIW, the soft hydrogels require some sort of structural anchor to stabilize their suspension above the substrate, DIW has the advantage of rapidly and accurately aligning those loci at points many hundreds of microns above their substrates without auxiliary gel infrastructure. This is illustrated in Figure 1e,f, which show schematic representations (left) and experimental confocal fluorescence micrographs (CFM; right) of two μ-CF designs that have been hybridized in hierarchy with the two hydrogel inks (pHEMA and pNIPAM). Additional 3D confocal fluorescence projections are given in Supporting Information 4. The various iterations in Figure 1 demonstrate that additive patterning methods, as are afforded by high precision DIW, can be used to modify functional scaffold chemistries with registrations that are retained in the final 3D scaffold assembly. These modifications are not limited to hydrogels, as we illustrate in the following sections that describe inks and other modification modes that facilitate their integration into developing cellular/tissue-mimetic cultures.

2.3. Directed Integration of Living Cells onto 3D Si α-CFs

We investigated 3D Si μ-CFs properties in cultures made with a model murine cell line, NIH 3T3 (3T3) fibroblasts. The cells in these microcultures are shown not only to respond to contact guidance cues provided by 3D microarchitectures but to adapt to them with a temporal dependence that impacts their on-scaffold growth morphology as their culture time lengthens. The complex temporal evolution of 3T3 cell morphology is illustrated in the results of a survey culture on a 3D Si μ-CF solenoid array made from a 1.2 μm thick device layer and patterned with three ribbon widths (Figure 2a). The temporal sensitivities of the cellular adaptation to the 3D μ-CFs are probed using an additive patterning method to localize, and thus specifically plate, the cells. To do so, DIW of the 3T3 fibroblasts is carried out using a 3T3/media/poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) gel suspension and localized at one end of a freshly prepared solenoid array (Figure 2b, top). The PEG gel initially adheres to the substrate, resisting dissolution by the incubation media for several hours; as a result, the 3T3 fibro-blasts adhere locally. Once the PEG gel dissolves (Figure 2b, bottom left), the 3T3 cells begin to migrate and advance along the solenoid array (Figure 2b, bottom right). The micrograph in Figure 2c shows a representative 3T3 cell’s morphology while it is migrating along the scaffold ribbon, with its cytoplasm elevated off the surface and bunched up with apparent actin polymerization-mediated leading edge protrusions and acto-myosin-mediated retraction edges evident.[17] The highlighted image selections illustrate the well-defined filopodia that anchor the cell to a scaffold ribbon pretreated with a fibronectin/poly-L-lysine (FN/PLL) protein mixture. This combination of extracellular matrix (ECM) and poly-ionic proteins is found to be an efficacious means to activate the Si μ-CF surfaces toward fibroblast attachment and growth (Supporting Information 5). The filopodia of migrating fibroblasts morphologically appear to have formed numerous focal adhesions, here presumably with the arginine-glycine-aspartic acid integrin recognition sequence (RGD) present in the extracellular matrix FN protein.

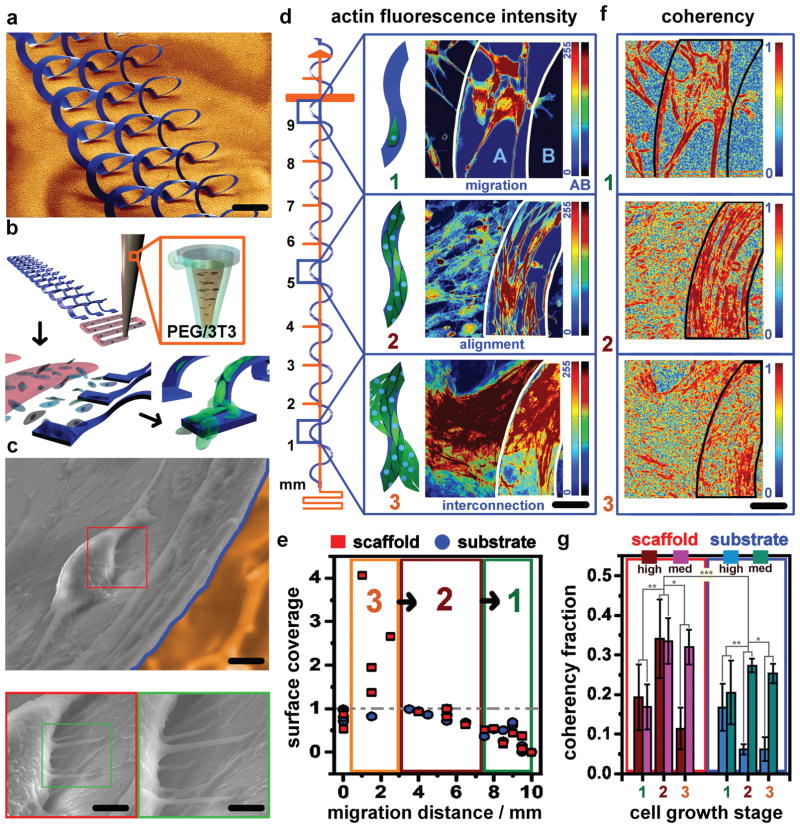

Figure 2.

3D migration dynamics and coherency of fibroblasts on microscaffolds. a) Colorized SEM images of a compressively buckled solenoid array (scale bar 500 μm). b) Schematics of DIW poly(ethylene glycol)/media-3T3 gel (top) that dissolves in culture as 3T3 cells attach locally (bottom-left) and then migrate onto the solenoid array (bottom-right). c) Colorized SEM and higher magnification insets of a migrating 3T3 cell on the solenoid array (yellow substrate, blue border on cell-loaded scaffold; scale bars 5 μm (top), 3 μm (lower left), 1 μm (lower right). d) Growth stages of 3D 3T3 cell migration, shown schematically where they occur on the solenoid scaffold, consisting of: (1, 0–3 d) migration, (2, 3–14 d) alignment, and interconnection (3, 14–21 d). Growth phases over 21 d are qualified by relative actin fluorescence intensity from confocal images, depicted for clarity with separate 0–255 color-scales (image, right) mapping actin fluorescence for either scaffold (A) or substrate (B, scale bar 50 μm). e) Fractional actin surface coverage quantification for scaffold and substrate. Fractional coverage >1 signifies the interconnection growth stage (3, orange box). Fractional coverage approaching 1 signifies near-confluence during the alignment stage (2, maroon box). Fraction coverage far below 1 signifies low cell density during the migration stage (1, olive box). f) Coherency maps calculated for exemplary confocal images visually quantify coherency distribution for each growth stage, with the color-scale of 1 describing high anisotropy/alignment and 0 describing isotropy. g) Coherency fractional coverage quantified for all growth stage images shows peak high coherency fractions (C > 0.9) for scaffolds only during the alignment stage (2), and medium coherency fractions (0.7 < C < 0.9) increasing for stages 2 and 3 on scaffold and substrate. Highest coherency seen on scaffolds. Statistical analysis to determine significance is given in Figure S7 (Supporting Information).

CFM images provide evidence of three growth phases for 3D cell migration/integration onto the 3D microarchitectures. The first growth phase is characterized by migration, during which small numbers of cells climb up onto free areas of solenoid ribbons from the substrate and begin to extend and align along its edges (Figure 2d-1). The second phase is characterized by alignment in which actin fibers of loose, cooperative cellular networks extend along the ribbon axes, whose lateral dimensions (2–10× the size of a spreading fibroblast, depending on the ribbon width examined) are ones that direct qualitatively similar degrees of high alignment and elongation of the networking cells, with only modest variation in cellular alignment depending on ribbon width, since for the same degree of cellular development, a wider ribbon is proportionally less con-fluent. In this phase, cells tend to align along the scaffold edges first and then gradually proliferate and migrate into open space until the ribbon area coverage is confluent (Figure 2d-2). Given that the substrate migration front maintains the same overall pace of advancement as the on-scaffold migration, we do not find conclusive evidence supporting a preferential 3D migration of cells onto the scaffold materials over that of their supporting substrates. Of note however is the fact that the curvature of the 3D μ-CF scaffolds indicates an implicitly longer distance over which cells must develop on them in order to achieve a spatially similar migration front to those cells developing on the substrate. This observation may suggest that higher cell migration velocities on the scaffolds are possible, or that the complete structural confinement of the developing cells leads to accelerated localized confluence and advancement of the cell growth front. In both growth phases 1 and 2, the primary effect of distance from substrate is that alignment increases with lateral distance, since junction/contact points provide multidirectional contact guidance cues that cease to be present with elevation off the substrate. The final phase of growth observed is interconnection, in which cells are confluent but do not yet stop dividing. Here, dense tissue-like sheets are observed that ultimately come to engulf the scaffold and interconnect it to the substrate (Figure 2d-3). Distance from substrate in growth phase 3 is best thought of in terms of an axial distance in that any interconnections will begin to form most proficiently when the gap between scaffold and substrate is small and progressively scale with time as the axial gap increases to its maximal displacement (≈500 μm) above the supporting substrate. The actin coverage fraction of the 3D scaffolds, which correlates with the developing 3T3 fibroblast network, is quantified and compared to the development patterns seen in the supporting elastomer substrate (Figure 2e). At confluence, a coverage fraction of unity (1) is expected. Coverage fractions on the 3D scaffolds can in fact yield values >1 for stage three growth behaviors, where tissue-like meshes engulf and span the full 3D height of the scaffold. Stage two growth coverage fractions range from unity to 0.5, and stage one growth coverage fractions taper off rapidly toward 0 at the migration front (the maximum distance of cellular migration, found to be 9.5 mm over 21 d in culture). Additional light, CFM, and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images documenting the 3T3 fibroblast growth on solenoid ribbon arrays as well as their 2D substrates are given in Supporting Information 6.

The changes in actin alignment present in the three qualitative growth stages are quantified as their orientation and isotropy in regions of interest using the structure tensor, J (a 2 × 2 symmetric matrix representation of partial derivatives that is commonly used in image processing),[18] given in Equation (1)

| (1) |

From this, we used the metric of coherency, C, to determine whether cellular features are oriented or not. This parameter is defined by Equation (2)

| (2) |

where λmax and λmin are the corresponding eigenvalues to the first (dominant orientation) and second eigenvectors of J. Figure 2f-1–3 shows the results of coherency calculations for representative CFM micrographs of each growth phase, where blue values (0) correspond to regions where local features are isotropic and red values (1) correspond to features that have one dominant orientation. Figure 2g gives the quantitative comparison of fractional coherency coverage for scaffold and substrate regions of CFM micrographs for each growth phase. These show that high coherency coverage (1 ≥ C ≥ 0.9) peaks dramatically during the alignment phase of growth on the scaffold only. Concurrently, moderate coherency coverage (0.9 ≥ C ≥ 0.7) increases with cell coverage during the alignment growth phase two, and remains high during the interconnection growth phase three. These data confirm that the alignment growth phase corresponds to a real increase in actin fiber orientation within the developing fibroblast networks, a trend that is statistically verified in the Supporting Information 7, with additional cell growth micrographs given as Supporting Information 8.

A critical feature of the on-scaffold cellular migration mechanism implicitly evidenced in these data relates to the fact that cell attachment and migration occur facilely on both faces of the μ-CF ribbons forming the solenoids. This is in fact a generalized feature of on-scaffold migration for other 3D geometries, as well as other scaffold materials beyond the Si exemplars shown in Figure 2, such as epoxy from photoresist SU8 shown in the Supporting Information 9–12. These optically transparent polymeric structures facilitate full reconstructions of cell organizational properties in culture by CFM. For instance, the lithographically patterned parallel gaps etched into the scaffold structures provide an environment unique to μ-CF structures in which cells can bridge and eventually in-fill the 20 μm gaps without substrate interferences, with cell network development progressing concurrently from both the dorsal and ventral table scaffold planes. While live imaging of cellular dynamics will be key to understanding the mechanisms of these behaviors, it is clear from CFM analysis that the fibroblasts need to anchor to their scaffold materials immediately adjacent to the aerial channels in order to eventually span them.

In the sections that follow, we directly compare the ways in which the scaffold geometry and aspect ratio of its features impact the morphological and quantitative alignment of 3T3 cells in culture. We also consider more complex and organotypic DRG cell populations that reorganize in vitro following their integration onto their 3D μ-CF environment.

2.4. Alignment Effects of α-CF Geometries on 3D 3T3 Fibroblast Cultures

Cell traction forces (CTFs) are known to regulate cell shape and tensional equilibrium[19] in static cells, but to also be the driving force that propels cellular migration, for example via force transmission to focal adhesions at the cell/scaffold interface. The environments of the 3D cultures studied here are ones vide infra defined by a high level of tensile strain.[20] More specifically, from the data above it is seen that the edges of the μ-CF materials provide key contact guidance cues that induce cellular extension and alignment adjacent to them. As the 3T3 cells proliferate on the μ-CF ribbons (Figure 2), they continue to elongate and align cooperatively as has been noted in the literature via their interactions with edge-adjacent cells.[6d,21] These induced organizations are design rule-sensitive and follow in different ways the 3D contact guidance cues presented by the μ -CF environment.

We explored the latter sensitivity by carrying out cultures of 3T3 cells on several geometric designs. The first is a low alignment contact guidance environment provided by a compressively buckled table scaffold, where induced strains are minimized on the table top except in regions lying close to the supporting leg (depicted schematically in Figure 3a, left inset). The table top (diameter of 1000 μm, 70 μm leg support widths) provides minimal directional information and disordered, low alignment cell networks develop as a consequence as seen in a CFM micrograph (green actin and blue nuclei, Figure 3a, left) and a colorized SEM image (orange substrate, cells-on-scaffold outlined in blue, Figure 3a, middle) at the same magnification, and a high-magnification colorized SEM image (Figure 3a, right). One notes that the long cell axes are oriented stochastically on their scaffold. Additional images of low alignment cell growth on tables are given as Supporting Information 13.

Figure 3.

Fibroblast responses to low and high alignment 3D microscaffold environments. a) Low alignment contact guidance from Si μ-CFs tables leads to disordered 3T3 networks shown with fluorescently stained (green) actin and (blue) nuclei (left, scale bar 50 μm), and with SEM images (yellow substrate, blue bordered scaffold loaded with cells, middle; scale bar: 50 μm). Long cell axes orient stochastically on planar table surfaces (right, scale bar 10 μm). b) High alignment contact guidance from Si μ-CF solenoids leads to ordered 3T3 networks with higher elongation, shown with fluorescently stained (green) actin and (blue) nuclei (left, 30 μm), and with SEM images (yellow substrate, blue bordered scaffold loaded with cells, middle; scale bar: 30 μm). Long cell axes orient in ordered networks that align to complex spatial vectors of the 3D ribbon surface (right, 10 μm). c) 3D alignment angles (Θ) compare the actin vector to the angle of the tangent at the nearest scaffold edge, a distance calculated from each nucleus center. d) Schematics of a Si μ-CF table (1 mm diameter) and Si μ-CF solenoid ribbons (widths 60, 100, 140 μm) are colorized relative to alignment conditions that occur on them (blue, higher alignment, low alignment angles; coral, lower alignment, high alignment angles). e) Histograms of elongation factor (left) and alignment angle (right) distributions for low and high alignment environments, shown with average values as bar graph insets. f) Distance from edge effects on average alignment angles and angle distribution FWHM for cells on a Si μ-CF table scaffold correspond with the points A and B (specified in d). Alignment angles and angle distribution FWHM for cells on Si μ-CF solenoid ribbon scaffolds correspond with the points C, D, and E (specified in d), with half widths (30, 50, 70 μm, respectively) used for the solenoids due to the presence of parallel edges. Statistical analysis to determine significance in e and f is given in Figure S16 (Supporting Information).

The second contact guidance environment studied is a high alignment compressively buckled solenoid ribbon (shown schematically in Figure 3b, left inset) with a critical design width of only 1–5 times the spreading 3T3 cell’s dimensions. Figure 3b (left) shows a representative CFM micrograph (green actin and blue nuclei) and a colorized SEM image (Figure 3b, middle) at the same magnification (orange substrate, cells-on-scaffold outlined in blue). Figure 3b (right) shows a high magnification colorized SEM image of fibroblasts grown on the buckled solenoid ribbon. One sees in these images that the cell aspect ratios are elongated and the long cell axes are oriented along a vector lying nearly parallel to the curvature of their scaffold ribbon. Fibroblasts growing in these and other environments that are stained with the calcein acetoxymethyl (AM) fluorescent live or immunocytochemically (ICC) stained following fixation are given as Supporting Information 14 and 15.

To quantitatively compare the difference in cellular alignment between specific low and high alignment 3D motifs, the angular difference between the actin vector of each 3T3 cell and the tangent vector of its nearest scaffold edge is measured (shown schematically in Figure 3c). The cell populations (≈150 for each condition) grown on either low (tables) or high (ribbons, shown schematically in Figure 3d) alignment scaffolds were measured by CFM. Differences in the elongation factors (long axes/short axes) were not found to be statistically significant between these two cases (Figure 3e, left). The average alignment angles showed pronounced differences, however, with values for cells grown on the ribbons (9.3 ± 8.6°) fully meeting the literature convention (<15°) for a highly aligned state (Figure 3e, right).[22] To analyze the influence of edge proximity for dictating actin alignment, fibroblasts grown on table scaffolds were subdivided based on their radial distance from the table edge. In this way, we measured their transition from an edge-aligned state within the first ≈60 μm of the scaffold edge (Figure 3f, A) to an unaligned state at larger distances (Figure 3f, B). Fibroblast alignment angles on the three different solenoid ribbon dimensions (Figure 3f, C–E, half width used to estimate edge proximity), were not found to be statistically significant from one another, though all cases showed extremely low alignment angles (significant alignment). In marked contrast, the variance in the angular distributions increased with distance from edge-related guidance cues of the table top scaffolds (Figure 3d–f). Angular distribution changes, CFM micrographs, and statistical analyses of these findings are given in Supporting Information 16. The results show that 3D μ-CF design rules play clear roles in dictating morphological decision-making of individual fibroblasts as well as their networks. In the sections that follow, we extend these findings to an organotypic cell culture in which primary rat DRG cell populations reorganize into ganglion-mimicking tissues.

2.5. Tissue-Level Integration onto 3D α-CFs

Specific micron scale design rules of the μ-CFs provide important functional contexts for controlling morphologies and organization of more complex tissue-level cellular structures—here exemplified in primary neuronal tissue cultures as they redevelop ex vivo. Dorsal root ganglia (DRGs) isolated from rats (Figure 4a) are nodular masses of sensory neuronal and other cell bodies at the posterior spinal cord root that relay information from the peripheral nervous system (PNS) back to the spinal cord.[23] The main DRG cell types are: (1) the DRG neurons, whose spherical cell bodies extend long bifurcating axons, sending one projection to the spinal cord and one to the periphery; (2) satellite glial cells (2–5 μm cell bodies) that coat the DRG neurons as supporting cell sheaths; and (3) Schwann cells, the main type of glial cells in the PNS, which support the neuronal extensions by myelinating axons and forming sheaths around neuronal processes.[24] Schwann cells also develop into their own networks in vitro by forming processes adjacent to their neural counterparts (Figure 4a, inset).[25]

Figure 4.

Dorsal root ganglion-derived cellular integration on 3D microscaffolds. a) Schematic of primary rat dorsal root ganglia and the cell populations that are dissociated from them (DRG neurons, Schwann cells, and satellite glia) which are b) cultured on Si μ-CF tables or SU8 epoxy polymer tables (light blue scaffolds). DRG scale bar is 450 μm and 2D DRG cell culture scale bar is 65 μm. c) Si μ-CF table arrays are cultured with DRG cells that redevelop tissue constructs guided by the 3D scaffolds (scale bar 1.5 mm) in (1) calcein AM-stained live cultures (scale bar 100 μm) and (2) fixed cultures immunocytochemically (ICC) stained for (red) neurons, (green) glia and (blue) nuclei. Red arrows specify neuron cell body positions (scale bar 150 μm). d) Colorized SEM images of SU8 epoxy μ-CF polymer tables of varying geometries include table legs only (top, 1), a mini table (middle,1), and an open table (bottom, 1; scale bar 150 μm), each cultured with DRG cells shown with phase contrast 2; scale bar 500 μm) and ICC microscopy (3; scale bar 400 μm).

In these studies, we examined μ-CFs comprised of both Si and SU8 epoxy materials to various benefit for optical characterization by CFM. Dissociated DRG cells are introduced to each, and the differences in growth compliance followed in extended live cultures (Figure 4b) in order to analyze the specific morphological and temporal responses of the primary cell culture to the 3D structural attributes of the scaffold. These responses are categorized by their specific morphologies, as detailed in later sections, but are well described in qualitative terms by the schematics presented in Figure 4b (inset), in which all three types of DRG cells reassemble in culture into ganglion-mimetic formations that develop differently on 3D scaffolds than they do in a 2D control. The data in Figure 4c-1 shows calcein AM live-stained DRG tissue cultures on an exemplary Si μ-CF table after ≈45 d in culture, which is part of a larger scaffold array given as Supporting Information 17. In all instances, the table μ-CFs supported cellular network formation, with numerous instances of axonal fibril bundles that are morphologically consistent with high-tension formations/connections that span between different parts of the scaffold. A representative Si μ-CF table top is shown in Figure 4c-2 following neurite-specific (microtubule-associated protein 2, MAP2, red) and glia-specific (glial fibrillary acidic protein, GFAP, green) ICC staining. Glia-mediated cell networks are seen to interconnect legs on opposite and adjacent sides of the scaffold. The nuclear stain DAPI (blue) is also used to help differentiate between individual cells. As shown, neurons tend to cluster on the legs of the tables, although they are seen with a lower frequency to adhere to the table top. Neuronal cell bodies (noted with red arrows) have a green halo due to the sheaths of glial satellite cells that surround them. Additional ICC cell images on Si table arrays are given as Supporting Information 18 and 19. The prevalence of DRG cell clusters at the junction between the table top and legs signify a 3D-specific mode of DRG cell network formation that is not evidenced in control planar cultures.

To examine how specific attributes of the μ-CF geometry direct the 3D DRG cell network development, a series of epoxy tables were prepared on PDMS substrates and seeded with dissociated DRG cells following surface treatment with a poly-ionic protein, PDL, that we chemically modified with the RGD integrin recognition sequence to prepare an RGD–PDL hybrid protein that renders strong growth compliance properties to these substrates. These structures, shown as colorized SEM images in Figure 4d-1, consist of a four-leg basic junction (or table legs), a mini table, and an open-ring table (in addition to the previously described four-leg table scaffold, presented in the context of an integrated light and CFM experimental series as Supporting Information 20). Light microscopy of all scaffolds performed over ≈45 d in culture showed that by day 7, mixed cell populations organize into clusters on the legs of all table types, while maintaining dense on-scaffold networks (Figure 4d-2). ICC images taken after 45 d in culture (Figure 4d-3) show that on-scaffold growth remains robust for the four-leg basic junction and the four-leg mini table, which have the smallest inter-cluster distances. Larger tables show moderate-to-low on-scaffold growth in comparison. Open-ring table scaffolds initially show good alignment between DRG cell networks and underlying scaffold geometry. As the culture times lengthen (at 2–3 weeks), the open ring curvature is increasingly disregarded as high tension axonal bundles bridge the shortest distance between adjacent cell clusters, until fewer cells are found on this scaffold geometry than on the others. Interestingly, the table Si 3D μ-CFs have 70 μm legs, the table SU8 3D μ-CFs have 50 μm legs, and both geometries show preferential cluster formation at the tabletop-to-leg junction. This suggests that a range of ribbon widths with dimensions on this order might equally support their development and attachment. All growth modes are contrasted with their 2D scaffold counterparts, which were found to guide network formation primarily through edge detection and resulted in cluster formations and interconnections that anchored or intersected the 2D scaffold geometries at random and arbitrary points (Supporting Information 21).

2.6. DRG Tissue-Level Organization and Morphology on 3D α-CFs

We next characterized the tissue-level morphologies that developed in the scaffold-supported DRG cell cultures. As the cultured cells reorganize as tissue-like assemblies, specific morphologies develop that require support by the non-planar attributes of the scaffolds’ microarchitecture. These tissue constructs are influenced by their scaffold’s contact guidance cues (in a manner similar to that seen in model fibroblast cultures), but are also dictated by the tensile strain fields (reported in the literature in the range of 100–102 nN for developing growth cones) that originate within the cell populations.[14a,g,h] These 3D-specific morphologies include: (1) ganglion-mimetic on-ribbon clusters (clusters that reorganize in a way that resembles the native dorsal root ganglion) (Figure 5a); (2) high tension fibers (Figure 5b) that are either scaffold-supported (top panels), or scaffold-anchored (bottom panels); and (3) cellular sheaths (Figure 5c) that occur on the flat plane of the table μ-CFs as the organotypic cell culture reorganizes.

Figure 5.

3D-specific morphological formations of dorsal root ganglion-derived cells. DRG tissue constructs develop through contact guidance from the scaffold and through development of apparent tensile morphologies within their networks. Tissue construct motifs include a) ganglion mimetic clusters that re-form around elevated, high aspect ratio scaffold geometries in (top) phase contrast, (middle) live calcein-AM stained, and (bottom) ICC-stained (scale bars 100, 50, 100 μm). b) High tension fibers form shortcuts that interconnect scaffold geometries in scaffold-supported and scaffold-anchored morphologies shown at low and high magnification SEM images (left, middle) and (right) fluorescence micrographs (scale bars top: 150, 5, 15 μm; bottom: 20, 10, 20 μm). c) Cellular sheaths develop as glial cells network around DRG neurons on table scaffold planes. More exposed neurons are shown at left, with thicker cellular sheaths shown at middle, and fluorescence micrograph of on-scaffold tissue networks at right (scale bars 8, 5, 20 μm).

The ganglion-mimetic cluster motifs are densely populated with cells, as illustrated in an exemplary optical image of a cluster lying at the junction between the leg and ring of an open-ring table scaffold (Figure 5a, top). With calcein AM live cell imaging, cell size heterogeneity is apparent (Figure 5a, middle). Fixed ICC imaging shows the heterogeneous cell population (blue nuclei, red neurons, and green glia) native to a cluster of this kind (Figure 5a, bottom). The frequency and functional locations of neuron-centric on-ribbon clusters indicate them to be a central anchoring component of the 3D growth motif. These clusters mimic how related cell populations interact within the DRG in vivo, as neuronal cell bodies are naturally clustered together in native DRGs, with their terminals bundled in fibers, supported by Schwann cells.[22]

Two additional motifs present in the 3D cultures were visualized with SEM and distinguished biologically with ICC. As noted, DRG tissue cultures show a pronounced tendency to form high tension constructs that interconnect adjacent table legs, spanning linearly even when table curvature is present (Figure 5b, top left). These are described as scaffold-supported fibers, contain numerous bundles of axons (Figure 5b, top middle), and can be differentiated into glial, neuronal, and nuclear components (Figure 5b, top right). These bundles of neuronal axons and Schwann cells also develop into high tension fibers that anchor to table μ-CFs but are sufficiently tensile to not use additional support (Figure 5b, bottom left). These structures also contain numerous cellular projections and axons (Figure 5b, bottom middle), that are distinguished biologically with ICC (Figure 5b, bottom right).

Also observed are cellular sheaths in which neuron attachment on the table top is densely woven with glial processes (Figure 5c, left) that blanket them with glial networks as shown in the SEM image in Figure 5c, (middle) and the CFM image in Figure 5c (right); neuron bodies covered with satellite glial cells are also seen (red circles). SEM images showing DRG cell morphologies are given as Supporting Information 22. These results suggest that compressively buckled μ-CFs are extremely promising for the programmable engineering of complex 3D functional materials environments. Beyond capacities for control of chemical environments, these findings suggest immediate opportunities that might provide embodiments to engender new applications in tissue engineering, regenerative medicine, 3D diagnostics, and therapeutic/implantable electronics.

3. Conclusion

Advances in materials assembly, specifically the combined use of the deterministic assembly of advanced electronic materials and direct ink writing of biocompatible polymer gels, provide a means through which to construct complex 3D architectures and devices that heterogeneously integrate soft/biological matter with high performance semiconductors. Such 3D μ-CFs—rendered growth compliant by modifications of their surfaces—yield nonplanar contact guidance environments that elicit tissue-mimetic hierarchies of organization. While the guidance cues provided by 3D μ-CFs do not directly replicate the nanostructural features of natural extracellular matrices, their open frameworks and supporting out-of-plane scaffold organizations make them an interesting addition to materials structures for use in tissue-level modes of cellular organization. They further engender new capacities for design and structural organization that distinguish them from planar patterns and more quasi 2D device formats for cellular cultures. As illustrated in the examples presented above, these distinctions include curvilinear forms, true terminating edges without sidewalls, broad variations of supporting feature widths (from the order of the dimensions of single cells to more extended areal layouts), geometrically controllable 3D placements of features (ranging proximally to distances that only self-supporting tissue-level cell constructs can bridge), and capacities to support cell growth on the adjoined faces of the supporting membrane substrates. Taken together, these findings describe new methodologies and design principles for 3D fabrication with ramifications in the fields of tissue engineering, diagnostics, therapeutics, and implantable electronics.

4. Experimental Section

Reagent List

Commercially available chemical reagents and abbreviations used in the following experiments were as follows. HEMA monomer (99%, containing 50 ppm monomethyl ether hydroquinone as inhibitor), NIPAM monomer, the radical initiator 2-hydroxy-4′-(2-hydroxyethoxy)-2-methylpropiophenone (Irgacure, IRG, 98%), pHEMA (pHEMA-300, average 300 kDa powder and pHEMA-1000, average 1,000 kDa powder), PEG (1E6 mw), trimethoxysilyl propyl(methacrylate), NaOH; dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and the radical initiator 2,2-dimethoxy-2-phenylacetophenone (DMPA, 99%), pNIPAM (carboxylic acid terminated average, Mn 10 000), sodium acrylate, polyvinyl pyrrolidone, hexamethyl disilazane (HMDS) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich and used as received. Organic cross-linker ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA, 98%, contains 90–110 ppm monomethyl ether hydroquinone as inhibitor) was filtered with a prepacked column for removing hydroquinone and monomethyl ether hydroquinone (Sigma) and stored away from light at 2–5 °C prior to use. For preparing protein solutions, succinimidyl 3-(2-pyridyldithio)propionate (SPDP), HEPES (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid) buffer, HBSS (Hank’s Balanced Salt solution) and fibronectin bovine protein plasma (FN) were purchased from Life Technologies. The polycationic protein poly-L-lysine hydrobromide (PLL, 30–70 kDa) and PDL (30–70 kDa), and FITC poly-L-lysine (FITC-PLL 30–70 kDa) were purchased from Sigma.

For cellular subculture embryonic murine fibroblasts (NIH/3T3 CRL-1658), Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), and calf bovine serum (CBS) were purchased from ATCC. Penicillin–streptomycin (Pen-Strep), trypsin, and Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (DPBS) were purchased from Life Technologies. For cell fixation and fluorescent staining, pH 7 4% paraformaldehyde-DPBS and 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) were purchased from Polysciences Inc. Bovine serum albumin (BSA) powder was purchased from Sigma. 1% Triton X-100 solution, rhodamine-phalloidin (R-P), Alexa 488 Phalloidin, and Alexa 555 goat anti-mouse secondary antibody were purchased from Life Technologies. Fluoro-gel mounting medium was purchased from EMS Acquisition Corp. Water used in all experiments was purified using a Milli-Q water purification system (Millipore, Bedford, MA) with resistivity higher than 18 MΩ cm.

Scaffold Fabrication

Si and SU8 microscaffolds were prepared as previously described. Briefly, preparation of 3D structures in Si began with photolithography and reactive ion etching (RIE) of the top Si layer on a SOI wafer. Immersion in hydrofluoric (HF) acid removed the buried oxide from the exposed regions and also from the regions near the edges of the patterned Si. Spin coating a layer of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) defined a uniform coating (≈100 nm) across the substrate and into the undercut regions. Photolithography and etching of a thin (50 nm) layer of gold deposited by electron beam evaporation yielded a mask for removing the PTFE from selected regions by RIE. Following removal of the gold, immersion in HF eliminated the remaining buried oxide by complete undercut etching of the Si. The PTFE remained at the edge regions, where it served to tether the Si microscaffolds to the bottom wafer. Transfer printing was used to retrieve the Si and to deliver it to a piece of water soluble tape (polyvinyl alcohol, PVA). A thin sheet of a silicone served as the assembly platform, stretched to well-defined levels of prestrain using a custom stage. Exposing the prestrained elastomer and the 2D Si precursor (on PVA) to ultraviolet light ozone (UVO) yielded hydroxyl termination on the surfaces of both the silicone and Si. Laminating the tape onto the elastomer with the Si side down, followed by baking in an oven yielded strong covalent bonds between the Si and silicone. Washing with tap water dissolved away the tape. Drying the sample and then slowly releasing the pre-strain in the substrate completed the assembly process.

Preparation of 3D structures in a photodefinable epoxy (SU8) began with spin-coating a layer (500 nm) of polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) as a sacrificial layer on Si wafer. And then a layer of SiO2 (50 nm) was coated on the PMMA by electron beam evaporation. Photolithography and etching by RIE defined the bonding site with SiO2. Spin-coating formed a layer of SU8 (4 μm) on the top of the patterned SiO2. Photopatterning of the SU8 defined the geometries of the 2D precursors that were aligned with the SiO2 underneath. Immersion in hot acetone partially removed the underlying PMMA layer, thereby allowing the entire structure to be retrieved from the Si wafer onto the surface of a piece of water-soluble tape (3M, Inc.). The following steps (prestraining, UVO activation, and releasing) were the same as in the Si microscaffold sample.

Preparation of 3D Polymer μ-CFs

The fabrication procedures began with thermal growth of a thin layer of silicon dioxide (SiO2, 500 nm in thickness) on a Si wafer. Next, spin casting and photolithography defined 2D polymer patterns using photodefinable epoxy (SU8, 4 μm in thickness) on the SiO2. Immersion in HF acid removed the buried SiO2 layer from the edges of SU8 patterns and exposed regions. Spin casting and photolithography patterned a layer of photoresist (AZ 5214, 4 μm in thickness) on top of the SU8 patterns to define bonding regions. Immersion in HF for around 6 h fully removed the remaining SiO2. Transfer-printing techniques enabled the retrieval 2D precursors from the Si wafer and their delivery onto water-soluble tape (PVA). A thin sheet (≈0.5 mm in thickness) of PDMS elastomeric substrate, created by mixing in a 30:1 ratio by weighing base and curing agent of a commercial material (Sylgard 184 Dow Corning), was stretched to a certain prestrain on a customized stage. The elastomer substrate and PVA tape were subjected to UV-induced ozone radiation to produce hydroxyl termination on their exposed surfaces. The PVA tape was then laminated on the prestrained elastomer with patterns facing downwards. Baking (70 °C for 10 min) resulted in the formation of strong covalent bond between PDMS and exposed patterns due to the condensation reactions between the hydroxyl groups. PVA tape was dissolved in hot water and the photoresist was removed by acetone. 3D polymer microstructures were formed by slowly releasing the prestrain.

Preparation of 3D polymer tables with parallel channels followed steps similar to those for making 3D polymer structures, except that SU8 (10 μm thickness) and silicone sheets (Dragon Skin Smooth-On, ≈0.5 mm in thickness) were used. For micro-scaffold surface modification, trimethoxysilyl propyl(methacrylate) was combined with acetic acid and water in a 1:2:2 ratio. The scaffolds were incubated for 1 h in this solution while on the PDMS transfer block, then rinsed with EtOH and H2O and dried. A pHH printable hydrogel was prepared as previously described, with a standard ink formulation of 25 wt% pHEMA-300, 10 wt% pHEMA-1000, 40 wt% HEMA, 23.5 wt% H2O, 1 wt% EGDMA, and 0.5 wt% DMPA. These reagents were mixed until DMPA dispersion was complete. pHEMA-300 and pHEMA-1000 powders were then added and the ink was mixed at room temperature away from light on a rotation mixing plate for 7–14 d to allow for complete homogenization of the viscous shear-thinning gel. A pHEMA/NIPAM printable hydrogel was prepared with the formulation 5 wt% pNIPAM, 30 wt% pHEMA-1000, 23.5 wt% dH2O, 38.65 wt% NIPAM, 1.875 wt% EGDMA, 1 wt% Irgacure.

Motion Control System

An Aerotech AGS-1000 high precision custom gantry with an A3200 integrated automation motion system was used for 3D printing scaffolds. G-Code programming language was used for generating diverse scaffold patterns. An Ultimus V high precision dispenser (Nordson EFD) was used for positive-pressure controlled printing in combination with 3cc amber light block syringe barrels and 10 μm pre-pulled glass pipette tip print-heads (World Precision Instruments Inc.). An IDS USB 3.0 C-Mount Camera with a color CMOS sensor with a 1.5× Navitar Attachment Lens and a 2.0× Precise Eye Navitar Adaptor Lens (1stVision Inc.) was mounted to the axial stage.

Surface Modification

To prepare true ECM protein solutions, FN and PLL proteins were suspended in water and DPBS, respectively, and were deposited on scaffold surfaces such that final concentrations of each during incubation were between 0.1 and 0.3 mg mL−1. RGD–PDL (0.1 mg mL−1) was used for the ECM–mimetic protein surface treatment. Incubation times (1–4 h) were used for all samples and protein-treated surfaces were allowed to dry prior to cell seeding. All Si microscaffolds were surface-treated in this way. UVO treatment (7–10 min) was performed prior to protein incubation for SU8 table scaffolds, which were either exposed to DPBS, true ECM protein solution, or an ECM–mimetic protein solution which we previously describe and was briefly reiterated here. To prepare ECM–mimetic protein solutions, a solution of PDL (2 mg mL−1) in HEPES buffer was reacted with solutions of SPDP in DMSO (50 × 10−6 m, 30 min, RT). The reaction mixtures were filtered through spin desalting columns, then subjected to solutions of cyc(RGDyC) (50 × 10−6 m) and stirred at 4 °C overnight. The products were purified by filtration through spin desalting columns.

Subculture and Fixation of NIH 3T3 Embryonic Murine Fibroblasts

NIH 3T3 embryonic murine fibroblasts were maintained in complete media containing DMEM with 10% CBS and 1% Pen-Strep. At 60–80% confluence, fibroblasts were incubated with trypsin (3 mL for 12 min) to achieve complete cell detachment. Resulting solutions were neutralized with complete media (4 mL) and flasks were rinsed DPBS (3 mL) to completely transfer cells prior to centrifugation. Cells were pelleted from solution and re-suspended in complete medium prior to scaffold seeding. Subculture was performed to maintain this cell line every 3 d. All fibroblasts were maintained at 37 °C at 5.0% medical grade CO2 throughout the period of cell culture and following seeding onto scaffolds. A Zeiss Axiovert 40 microscope with phase-contrast was used to monitor live cultures.

For fluorescence characterization of FN/PLL protein surface treatment, 300 μL 0.1 mg mL−1 FN solution was combined with FPLL (200 μL of 0.5 mg mL−1) and 1 mL DPBS. Scaffolds are incubated in the resulting fluorescent protein solution for 4 h, and stored protected from light prior to imaging. For 7 d and 14 d studies of diverse Si scaffold geometries, media were replaced every 72–96 h. For 21 d studies on Si solenoid scaffolds, fresh media were added between 72 and 96 h and the media were 90% exchanged for fresh complete media every 7 d. For 7 d studies on SU8 Tables, scaffolds were imaged with light microscopy between 72 and 96 h after seeding and fresh media were added.

To print fibroblast via DIW adjacent to solenoid scaffold array, cells were grown to 70–80% confluence in a 75 cm2 cell culture flask, then removed from the flask via a 10 min trypsin treatment and pelleted via centrifugation. All supernatant media were removed over the cell pellet, then the pellet was resuspended at the ambient residual volume over the pellet (≈200 μL). 1E6 mw PEG (27.5 mg) was combined with complete media (0.25 mL) and homogenized in a microcentrifuge tube with a THINKY centrifugal mixer then 100 μL of cell pellet concentrate was pipetted into the PEG matrix. A microspatula was used to homogenize the cells within the thick gelatinous matrix, which was then loaded into a 150 μm diameter printhead (Nordson EFD) and extruded via DIW in a smooth contiguous printhead. Cells were printed in alternating lines at one end of the solenoid scaffolds on which they were intended to migrate. After 24 h, there was already very high cell density localized in that region, and the cells had migrated forward into the scaffold vicinity.

For applying cells universally to 3D μ-CFs, the fibroblasts seeding density was 1E6 cells mL−1. The areas of the regions seeded onto were varied based on overall scaffold areas, which were encircled in a thermoadhesive ring prior to surface treatments and whose areas were as large as 2.5 cm by 5 cm. 2 mL of cells was added at this concentration to the scaffold area, or proportionally for smaller scaffold areas. Scaffolds were incubated with cells for 1 h before additional media were added to allow for cellular attachment.

Fibroblast scaffolds were fixed and stained with 1 of 2 protocols. For red actin filament stains, scaffolds were rinsed 3× with DPBS then fixed in pH 7 4% paraformaldehyde–DPBS solution at room temperature for 10 min. Scaffolds were rinsed with DPBS for 5 min then exposed to Triton X-100 in DPBS (0.25%, 3 min) to permeate membranes. Following an additional DPBS rinse, cells were incubated in BSA–DPBS solution (1%, 10 min) to reduce nonspecific binding of fluorescent stains. To fluorescently stain actin filaments and nuclei, 1:200 diluted R-P solution in BSA–DPBS (1%) was applied to the scaffolds for 20 min immediately followed by 1 min incubation in DAPI–DPBS (0.002%, Polysciences Inc.). Scaffold assemblies containing fixed and stained fibroblasts were then washed gently with dH2O. For scaffolds that have green actin filaments, PF and Triton X-100 treatments and rinses were performed as described, then rinsed in DPBS, then incubated for 1 min in DAPI. The scaffold was again rinsed in DPBS and incubated for 1 h in 1:400 ALEXA 488 Phalloidin followed by a dH2O wash. For all samples, Fluoro-gel (EMS Acquisition Corp.) liquid mounting medium was applied to the scaffolds to prevent photobleaching and to protect the integrity of scaffold filaments. 25 mm diameter round 1.5H high precision coverslips (Azer Scientific) or 1.5 rectangular coverslips were gently applied over the mounting medium, and samples were stored away from light at 4 °C prior to imaging.

Adult Rat DRG Isolation

All work with live animals was performed in full compliance with local and federal guidelines for the humane care and treatment of animals and in accordance with approved by the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign IACUC animal use protocol. Sprague-Dawley male rats were quickly decapitated using a sharp guillotine. Spine vertebrae were surgically cut on both side between pedicle and lamina in the area of the facet of superior articular process. This cut exposed the spinal cord which was removed. Additional cuts on sides and in the middle of the ventral portion of the vertebral column created two chains of vertebra pieces with easily visualized DRGs. DRGs were removed using fine forceps and placed into the Hibernate A (Life Technologies) solution located on ice.

Primary Adult Rat DRG Dissociation and Seeding

Approximately 20 lumbar and thoracic DRGs from an adult rat were collected and stored in Hibernate A media up to 2 d before seeding. The Hibernate media was then removed. The DRGs were treated with collagenase (0.25%) in DRG physiological media (1.5 h at 37 °C), shaken a few times during incubation and violently upon completion of the incubation period. The DRGs were centrifuged (200 × g for 2–3 min) to remove supernatant, and washed with HBSS. After another centrifugation to remove the HBSS, the DRG were incubated in Trypsin with EDTA (0.25% for 15 min at 37 °C). The DRGs were centrifuged to remove supernatant, resuspended in DRG media +1% fetal bovine serum (FBS) for 50 s to inactivate trypsin, and triturated. Once some of the pellet resettled, the supernatant was collected and centrifuged for 5 min at 200 × g. The resulting pellet was washed with HBSS and centrifuged to remove supernatant. The cells located in the pellet were resuspended in the desired amount of DRG media containing the glial inhibitor AraC, usually 1 mL per 10 original DRGs. After cell seeding, the scaffolds were incubated for 10 min at 37 °C to allow for cell attachment before an additional 2 mL per Petri dish (3 mm in diameter) of DRG media was added. The media were changed every 7 d. The concentration of AraC in the DRG media was kept at 0.3 × 10−6 m from the moment of cell seeding until the end of the culture.

Immunocytochemistry–Neuronal Extensions (MAP2)/Glia (GFAP)/Nuclei Staining

After 7 d in culture, neurons were rinsed three times with PBS (37 °C), immersed in 4% PF (37 °C) at ambient temperature (23–25 °C) for 20 min and then rinsed again with PBS, five times (last time for 5 min on a shaking board). A PBS solution containing 0.25% Triton X-100 was added to the samples for 10 min to permeabilize cellular membranes, before rinsing again with PBS five times. The samples were incubated in a 5% NGS (Normal Goat Serum) for 30 min before rinsing again with PBS five times. The samples were then exposed to primary rabbit anti-MAP2 antibody (Abcam) at a 1:1000 dilution at 4 °C overnight and then rinsed five times with PBS. Next, the samples were exposed to primary chicken anti-GFAP (Abcam, 1:1,000 dilution) antibody at room temp for 1 h and then rinsed five times with PBS. Secondary Alexa 594 anti-rabbit (Life Technologies) and Alexa 488 anti-chicken IgG antibodies (LifeTechnologies,1:200) were added to the samples, which were allowed to incubate for 1 h (23–25 °C). The samples were then rinsed with PBS five times. Finally, the samples were incubated with DAPI in PBS (0.002% for 1 min) and rinsed with deionized water 30 s. The samples were covered with 2–3 drops of antifade mounting media and a coverslip was set on top of the mounted sample.

Confocal Fluorescence Imaging

All fixed scaffolds were visualized using the Zeiss LSM7 Live CFM. 10x EC Plan-Neofluar NA 0.3 and 20× objective lenses were used to image large scaffold volumes and required no immersion medium. A 40× NA 1.4 objective lens was used for cell structural analysis and alignment analysis, and a 100× Plan Apochromat NA 1.4 objective lens was used to image individual morphologies of gap spanning cellular structures. Both lenses used Zeiss Immersol 518 immersion medium with refractive index ne = 1.518 at 23 °C. FN/FPLL-treated scaffold fluorescence was measured with 488 nm laser excitation and fluorescence emission was collected with an LP 495 filter. Pinhole diameters for all images ranged from 1 to 2 AU and followed Nyquist sampling rules. An NFT 490 beam splitter, BP 495–520+BP550-615 IR filter and BP 415–480 filter were used to collect multichannel fluorescence data from 405, 488, and 550 nm laser excitation for fibroblast-seeded scaffolds.

Live/Dead Assays and SEM Sample Preparations

The live/dead assay was applied to scaffolds at relevant time-points by mixing calcein AM “live” stain (5 μL) and ethidium homodimer “dead” stain (5 μL) with DPBS (10 mL) and incubating all sample chambers in this solution (200–300 μL) during imaging on a Zeiss Axiovert 25 microscope.

To prepare samples for SEM, samples were fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde then soaked for another 24 h in DPBS. A 30% EtOH/H2O was then applied to all samples to begin incremental dehydration. This was followed in succession by a 70% EtOH:H2O and 100% EtOH solution. Incubation in solution type was no less than 20 min and no more than 1 h. The EtOH solution was replaced with fresh EtOH solution, in which the samples were stored overnight. They were then immersed in EtOH/HMDS solution of incrementally high concentration consisting 2:1 EtOH/HMDS, 1:1 EtOH/HMDS, 1:2 EtOH/HMDS, 100% HMDS, then allowed to dry overnight for full evaporation of HMDS. The samples were then mounted for SEM and sputter-coated (30 s) with Au/Pd prior to imaging. The JEOL 7000F SEM was used for collecting images.

Keyence VK-X250 Laser Scanning Microscope Imaging

Samples were prepared for imaging according to the SEM sample preparation protocol. Keyence VK-X250 laser scanning micrographs were recorded with either the 50× or 150× objective lens. A 1024 × 768 array of height data was acquired and corrected using the tilt correction feature to remove a second-order polynomial curve from the surface and create a flat reference plane for measurements. For creating a height profile, a cross-section was drawn across the center of the given cell. The maximum profile height was identified using the software. The average value of the base reference line was then identified using a least-squares averaging across a drawn line segment of data. Finally, the height distance from the maximum to the base reference line was calculated and output.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

J.M.M. and S.X contributed equally to this work. J.M.M. directed cellular growth experiments, DIW printing, confocal imaging and related analyses, data quantification, statistical analyses, and manuscript development. S.X. directed engineering and fabrication of scaffolds, developed the principal experimental goal, collected SEM micrographs of cell-free scaffolds, and contributed to manuscript development. A.B. completed DRG cellular growth experiments and related confocal imaging, and contributed to manuscript development. K.I.J. contributed foundational scaffold engineering. Z.Y. directed engineering and fabrication of polymer scaffolds for DRG experiments. J.M.M., S.X., A.B., and Z.Y. contributed to planning experiments. D.J.W collected SEM micrographs for fixed DRG cellular cultures. M.A.A. contributed to manuscript development. K.N., Q.L., M.H., Z.W., M.P., R.W., and J.S. assisted with scaffold fabrication, engineering and/or optimization. J.W.L. contributed to the discussion of data and results. S.S.R. harvested primary cells for DRG cultures. J.V.S. contributed foundational knowledge and resources for underlying principles of this study including cellular dynamics and DRG culture. R.G.N. and J.A.R. developed and organized the central principles and foundational approaches for the project overall and the manuscript specifically. J.M.M., S.X., A.B., Z.Y., S.S.R, J.V.S., J.A.R., and R.G.N. contributed to discussion and evaluation of results. The authors graciously acknowledge Prof. Jennifer A. Lewis for her foundational contributions regarding the principles underlying DIW. The authors also thank A. Sydney Gladman for her instrumental advice for setting up the DIW system. The authors thank MRL Senior Research Scientist Julio A.N.T. Soares and Carl Zeiss Microscopy Advanced Imaging Specialist Matthew Curtis for their assistance with CFM optics and imaging protocols. This material was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, under Award Number DE-FG02-07ER46471 through the Frederick Seitz Materials Research Laboratory at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. The support of the National Institute on Drug Abuse through P30DA018310 facilitating studies of neuronal cultures (S.S.R., J.V.S.) is also gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Contributor Information

Dr. Joselle M. McCracken, School of Chemical Sciences University of Illinois-Urbana Champaign Urbana, IL 61801, USA

Prof. Sheng Xu, Frederick Seitz Materials Research Laboratory and Department of Materials Science and Engineering University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Urbana, IL 61801, USA

Adina Badea, School of Chemical Sciences University of Illinois-Urbana Champaign Urbana, IL 61801, USA.

Dr. Kyung-In Jang, Frederick Seitz Materials Research Laboratory and Department of Materials Science and Engineering University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Urbana, IL 61801, USA

Dr. Zheng Yan, Frederick Seitz Materials Research Laboratory and Department of Materials Science and Engineering University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Urbana, IL 61801, USA

Dr. David J. Wetzel, School of Chemical Sciences University of Illinois-Urbana Champaign Urbana, IL 61801, USA

Kewang Nan, Frederick Seitz Materials Research Laboratory and Department of Materials Science and Engineering University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Urbana, IL 61801, USA.

Qing Lin, Frederick Seitz Materials Research Laboratory and Department of Materials Science and Engineering University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Urbana, IL 61801, USA.

Mengdi Han, Frederick Seitz Materials Research Laboratory and Department of Materials Science and Engineering University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Urbana, IL 61801, USA.

Mikayla A. Anderson, School of Chemical Sciences University of Illinois-Urbana Champaign Urbana, IL 61801, USA

Jung Woo Lee, Frederick Seitz Materials Research Laboratory and Department of Materials Science and Engineering University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Urbana, IL 61801, USA.

Zijun Wei, Frederick Seitz Materials Research Laboratory and Department of Materials Science and Engineering University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Urbana, IL 61801, USA.

Prof. Matt Pharr, Frederick Seitz Materials Research Laboratory and Department of Materials Science and Engineering University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Urbana, IL 61801, USA

Renhan Wang, Frederick Seitz Materials Research Laboratory and Department of Materials Science and Engineering University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Urbana, IL 61801, USA.

Jessica Su, Frederick Seitz Materials Research Laboratory and Department of Materials Science and Engineering University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Urbana, IL 61801, USA.

Dr. Stanislav S. Rubakhin, Neuroscience Program University of Illinois-Urbana Champaign Urbana, IL 61801, USA

Prof. Jonathan V. Sweedler, School of Chemical Sciences University of Illinois-Urbana Champaign Urbana, IL 61801, USA. Neuroscience Program University of Illinois-Urbana Champaign Urbana, IL 61801, USA

Prof. John A. Rogers, School of Chemical Sciences University of Illinois-Urbana Champaign Urbana, IL 61801, USA. Frederick Seitz Materials Research Laboratory and Department of Materials Science and Engineering University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Urbana, IL 61801, USA

Prof. Ralph G. Nuzzo, School of Chemical Sciences University of Illinois-Urbana Champaign Urbana, IL 61801, USA. Frederick Seitz Materials Research Laboratory and Department of Materials Science and Engineering University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Urbana, IL 61801, USA

References

- 1.a) Kim DH, Ahn JH, Choi WM, Kim HS, Kim TH, Song J, Huang YY, Liu Z, Lu C, Rogers JA. Science. 2008;320:507. doi: 10.1126/science.1154367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ahn JH, Kim HS, Lee KJ, Jeon S, Kang SJ, Sun YG, Nuzzo RG, Rogers JA. Science. 2006;314:1754. doi: 10.1126/science.1132394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoon J, Baca AJ, Park S-I, Elvikis P, Geddes JB, Li L, Kim RH, Xiao J, Wang S, Kim T-H, Motala MJ, Ahn BY, Duoss EB, Lewis JA, Nuzzo RG, Ferreira PM, Huang Y, Rockett A, Rogers JA. Nat Mater. 2008;7:907. doi: 10.1038/nmat2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Yu C, Yuan P, Erickson EM, Daly CM, Rogers JA, Nuzzo RG. Soft Matter. 2015;11:7953. doi: 10.1039/c5sm01892g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Stewart ME, Anderton CR, Thompson LB, Maria J, Gray SK, Rogers JA, Nuzzo RG. Chem Rev. 2008;108:494. doi: 10.1021/cr068126n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Bronstein ND, Yao Y, Xu L, O’Brien E, Powers AS, Ferry VE, Alivisatos AP, Nuzzo RG. ACS Photonics. 2015;2:1576. [Google Scholar]; b) Kim HS, Brueckner E, Song J, Li Y, Kim S, Lu C, Sulkin J, Choquette K, Huang Y, Nuzzo RG, Rogers JA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:10072. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102650108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Park SI, Xiong Y, Kim RH, Elvikis P, Meitl M, Kim DH, Wu J, Yoon J, Chang-Jae Y, Liu Z, Huang Y, Hwang KC, Ferreira P, Xiuling L, Choquette K, Rogers JA. Science. 2009;325:977. doi: 10.1126/science.1175690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]