Abstract

Children in grades 4 to 6 (N=14) who despite early intervention had persisting dyslexia (impaired word reading and spelling) were assessed before and after computerized reading and writing instruction aimed at subword, word, and syntax skills shown in four prior studies to be effective for treating dyslexia. During the 12 two-hour sessions once a week after school they first completed HAWK Letters in Motion© for manuscript and cursive handwriting, HAWK Words in Motion© for phonological, orthographic, and morphological coding for word reading and spelling, and HAWK Minds in Motion© for sentence reading comprehension and written sentence composing. A reading comprehension activity in which sentences were presented one word at a time or one added word at a time was introduced. Next, to instill hope they could overcome their struggles with reading and spelling, they read and discussed stories about struggles of Buckminister Fuller who overcame early disabilities to make important contributions to society. Finally, they engaged in the new Kokopelli's World (KW)©, blocks-based online lessons, to learn computer coding in introductory programming by creating stories in sentence blocks (Tanimoto and Thompson 2016). Participants improved significantly in hallmark word decoding and spelling deficits of dyslexia, three syntax skills (oral construction, listening comprehension, and written composing), reading comprehension (with decoding as covariate), handwriting, orthographic and morphological coding, orthographic loop, and inhibition (focused attention). They answered more reading comprehension questions correctly when they had read sentences presented one word at a time (eliminating both regressions out and regressions in during saccades) than when presented one added word at a time (eliminating only regressions out during saccades). Indicators of improved self-efficacy that they could learn to read and write were observed. Reminders to pay attention and stay on task needed before adding computer coding were not needed after computer coding was added.

Keywords: dyslexia, computerized writing instruction, hope themes, mode of sentence presentation during reading comprehension, computer coding instruction

To begin, dyslexia, a specific learning disability (SLD) in otherwise typically developing students, is defined and contrasted with another SLD, dysgraphia. Then a review of prior research studies on effective treatment for dyslexia based on a hybrid model (combined human teacher instruction and use of computerized learning activities) and a review of recent research studies based only on computer teacher instruction are presented. Next, the rationale is explained for introducing in the current study new sentence reading comprehension learning activities based on recent eye movement research findings. Finally, the methods and results for the current study that added a hope story and a hands-on engagement learning activity, as used in prior hybrid studies, to explicit literacy instruction aimed at subword, word, and sentence/text close in time, as used in prior studies employing computer teacher instruction, are first described and then discussed.

Defining and Identifying Dyslexia

Dyslexia is a word of Greek origin meaning impaired (dys) word (lexical) skills; a morphological modification replaces the –ical at the end of the base word with –ia and thus transforms an adjective (word-like) into a noun (condition of having). Dyslexia is a reading disability associated with problems in decoding unfamiliar words or pronounceable nonwords without meaning, but it is also a writing disability. Increasingly the persisting spelling problems in those with dyslexia have been documented in research across languages with deep orthographies such as English (Berninger, Nielsen, Abbott, Wijsman and Raskind 2008; Bruck, 1993; Connelly, Campbell, MacLean and Barnes 2006; Lefly, and Pennington 1991; Maughan, Messer, Collishaw, Snowling, Yule and Rutter 2009) and shallow orthographies such as Spanish (Serrano and Defior 2011) and German (Roeske et al. 2009). Both the word reading/decoding and spelling/encoding problems are impaired word-level skills.

Individuals with dyslexia may also have co-occurring dysgraphia (condition of impaired subword letter writing, i.e., handwriting); and individuals with dysgraphia may have problems in spelling but not reading (Berninger, Nielsen et al. 2008). Unfortunately during a time in education when evidence-based identification of reading disabilities and reading instruction for treating them is emphasized, evidence-based identification of writing disabilities and writing instruction for treating them has received far less attention. See review of research supporting the claim that writing disabilities have been left behind whether they occur alone as in dysgraphia or co-occur with dyslexia (Berninger, Nielsen et al. 2008; Katusic, Colligan, Weaver and Barbaresi 2009). However, research on identifying writing disabilities and treating them has emerged in the past decade and is increasing.

On the one hand, this research shows that dyslexia and dysgraphia are disorders of written language. Individuals with dyslexia have difficulty encoding/spelling words (written lexical units) as well as decoding/reading written words by transforming them into overt or covert spoken words (e.g., Bruck, 1993; Lefly and Pennington 1991). Individuals with dysgraphia and in some cases dyslexia have difficulty forming letters legibly and writing them automatically; and these difficulties cannot be explained solely on basis of motor processes— orthographic processes (coding written letters in memory) are also involved (e.g., Berninger 2009). On the other hand, not only written language processes are involved. Perceptual processes are involved in perceiving the initial visual input during reading and motor processes are involved in oral reading or written spelling, but neither reading nor writing can be understood or taught purely as a perceptual or motor process—language processing is also involved. After incoming visual stimuli are perceived, they are converted into visible language; and outgoing oral reading of words and written production of letters and words involve expressing outputs of language processing via oral-motor system (oral reading, i.e., language by mouth) or manual-motor system (handwriting, i.e., language by hand). However, attention and executive functions (Berninger, Abbott, Cook and Nagy 2016) and social emotional variables (Nielsen, Haberman, Todd, Abbott, Mickail and Berninger in press) are also involved. Thus, diagnosing and instructionally treating SLDs-WL such as dyslexia with or without co-occurring dysgraphia should take into account multiple relevant processes: sensory, motor, language, social emotional, and attention/executive functions.

Treating Dyslexia

Although the biological basis of SLDs such as dyslexia has been well established based on brain and genetics research, treatment of dyslexia requires instructional intervention (for recent reviews of the biological bases and effective treatment across multiple research groups see Berninger 2015). The current study drew on programmatic research over 25 years, much of it involving computers for assessment and/or intervention, to identify necessary components of instruction for effective treatment of dyslexia. Like fine cuisine for which the mix of multiple ingredients matters for taste and car engines for which multiple components are needed and must be tuned up to work together, functional brain systems that support reading and writing draw on multiple components. Thus, the goal of the past and current studies was not to identify the single treatment component that causes the affected individual to begin to read or write better, but rather to identify the set of instructional components that enable the affected individual to begin to read and write better.

Hybrid studies

Four prior studies combined human teacher instruction with use of computers for specific learning activities included in the instructional program. This research drew upon prior randomized controlled studies with at risk readers and writers in grades 1 to 4 in school settings and demonstrated the effectiveness of teaching to each level of language (subword letter writing, word reading/decoding and spelling/encoding, and syntax and text comprehension and composing) close in time with instructional activities that do not last long resulting in habituation. The four studies, which were conducted in a university setting with participants in multi-generational family genetics research, replicated this instructional design principle which helps students pay attention and sustain attention and make connections across the levels of the multi-leveled reading and writing systems.

All studies taught handwriting using the components identified in randomized controlled studies in schools as being the most effective of the six handwriting methods compared. The teacher names the letter at each of the following steps repeated for each of the 26 letters in a different random order in each lesson: study numbered arrow cues for sequence of strokes in formation of a letter, close eyes and see the letter form in the mind's eye; open eyes and write letter; compare letter produced with model and fix if does not look like it (see Berninger 2009).

Word reading and spelling were taught based on results of three prior studies. The first study in Berninger, Winn et al. (2008) showed that adding morphological awareness training to word reading and spelling instruction is more effective than phonological awareness training alone. The second study in Berninger, Winn et al. (2008) showed that adding orthographic awareness training to phonological and morphological awareness training is more effective than only phonological and morphological awareness training. Thus, all studies that followed taught phonological, morphological, and orthographic awareness and their interrelationships in each lesson for word reading and spelling.

One study showed the importance of the writing path to reading and teaching strategies for silent reading as well as writing (Niedo, Lee, Breznitz, & Berninger, 2014). Thus, subsequent studies taught writing and reading learning activities in the same lesson sets, silent as well as oral reading, and writing strategies (Niedo, Tanimoto, Thompson, Abbott, and Berninger, 2016).

Computer teacher only instruction

Computerizing instruction for dyslexia has many potential benefits. To begin with it makes it possible to share the computerized literacy instruction (reading and writing) with many schools, teachers, and students who can benefit from evidence based practices. Although computers are often used in schools for accommodations for students with SLDs, a premise of these computer teacher studies was that computers can also be employed to deliver specially designed instruction (Thompson et al., 2016a).

A unique feature of the five versions of the computerized Human Assisted Writing Knowledge (HAWK™) developed by our research group is that it employs computer teachers that use oral language instruction that students hear through ear phones while they work with the computer screen and tools. These include animation and other computer-supported techniques for displaying the visible language on a screen (Berninger, Nagy, Tanimoto, Thompson and Abbott 2015; Tanimoto, Thompson, Berninger, Nagy, and Abbott 2015). Also, the optimal combinations of input-output modes for writing notes or summaries of source material (Thompson et al. 2016a) and effective ways for teaching orthographic coding and orthographic loop skills involved in handwriting and spelling (Thompson, Tanimoto, Berninger and Nagy 2016b, 2016c) have been investigated for computerized writing instruction. Human teachers are needed only to sign in students so the server stores their responses to learning activities and monitor that students are paying attention to and engaging in them, that is, are not daydreaming or are doing something else. If students do not appear to be attending to or engaging in the learning activities, the human teacher prompts them gently to do so (Niedo et al., 2016).

For the current study building upon these past computer teacher studies we were also interested in expanding the learning activities for reading comprehension beyond the sentence level alone to the text level and in ways informed by a recent eye movement study conducted by the brain imaging group in the interdisciplinary research center. Because the defining hallmark impairment in dyslexia is reading unfamiliar words, which are typically operationalized as nonwords that can be decoded based on the alphabetic principle but lack semantic meaning (Lyon, Shaywitz and Shaywitz 2003), many of the learning activities in the prior versions had focused on decoding in the reading direction and encoding in the spelling direction. Yet, all students including those with dyslexia need to read sentences for meaning, which requires saccadic eye movements—forward and backward—punctuated by fixations during which one or two words are read. Eye movement research has shown that those with dyslexia exhibit selective attention dyslexia when reading words in context, that is, distraction by nearby written words in sentences (Rayner, Murphy, Henderson and Pollatsek (1989). A recent study found that during saccades those with dyslexia are more likely than typical readers or those with pure dysgraphia to make regressions out (beyond the next word they should fixate on) and regressions in (back to prior fixated words or skipped words) (Yagel et al. 2017).

A premise motivating the current research is, therefore, that how a computer presents the words in sentences may help those with dyslexia bypass their tendency to regress out and regress in. A paradigm introduced by Potter and colleagues (e.g., Potter, Kroll and Harris, 1980) compares presentation of a sentence with all words appearing simultaneously (one sentence at a time) versus with each word appearing alone over time in syntactic order but never all together (one word at a time). In the current study another presentation mode—adding one word at a time to accumulating text—was compared to one word at a time. Adding one word at a time presentation allows regressions in to prior text but not regressions out to words ahead of the one that comes next in serial order. One word at a time does not allow either regressions out or regressions in because no other text appears simultaneously. Comparison of sentence reading comprehension accuracy between these two presentation modes—one word at a time versus one added word at a time— is relevant to understanding how mode of computer presentation can affect reading comprehension in children with dyslexia.

Adding hope stories and hands-on engagement to computer teacher studies

Students who experience chronic struggles and failures may develop social emotional issues especially internalizing disorders (Nielsen et al., in press), give up on themselves, and develop belief systems that they cannot succeed in writing and/or reading. For example, as one student who was participating in the assessment study and a related genetics study told his mother who then shared with the research team: “I am damaged goods. There is no way I can learn to write and read like other kids my age. There is no point continuing to try or having children of my own because they will have learning disabilities too. It's in my genes.” Indeed research has shown that for adolescents their hope in their future academic success is predicted by their beliefs about self-efficacy and loneliness, especially if one has a history of learning disabilities (Lackaye and Margalit 2008). Hope has also been shown to be a mediator between risk and protective factors; and self-efficacy for academic achievement; and hope can affect how much effort a student with learning disabilities will devote to overcoming learning problems (Idan and Margalit 2015).

One way to help students who experience chronic failure and struggles and question whether they can learn is to incorporate hope themes across lessons designed to provide explicit writing and/or reading instruction. Examples of hope themes that have been used in instructional intervention programs for students with dyslexia have included the stories of the lives of Albert Einstein (Berninger 2000), Mark Twain (Berninger, Winn et al. 2008), and John Muir (Berninger, Winn et al. 2008). All these individuals did not succeed early in their schooling but ended up not only succeeding in later life but also making important contributions to society: Einstein changed the paradigm in physics; Twain captured cultural insights orally and in writing and wrote the first novel composed by typewriter; and John Muir combined science and writing to record observations of nature in American wildernesses before founding the national park system in the United States. Also, Sequoyah, a Native American for whom the redwood forests in the US are named and who had physical disabilities, during middle age created the written syllabary for recording the oral Cherokee language in writing (Niedo et al. 2014). However, the current study is the first study using the HAWK© computerized lessons to include Hope Stories in the session.

Another way to motivate students with chronic struggles related to dyslexia or other kinds of SLDs is through learning activities that they find interesting, which affects their attention to the content and tasks, and that engage them mentally (Abbott et al., 2017). Prior hybrid research studies for students with dyslexia showed that one way to facilitate interest in and engagement of the mind is through including hands-on science problem solving activities in the literacy lessons. For example, students read interesting illustrated texts on specific topics in science, discussed them, built models of relevant concepts from manipulatives, and wrote about the concepts (Berninger, 2000). Or, they took notes while listening to audio recorded text about specific topics in science, discussed, wrote about those read and heard texts, and made illustrative drawings or engaged in virtual reality problem solving activities with computers (Berninger, Winn et al. 2008). Yet another potentially effective approach we investigated for the first time in the current study is to teach students computer coding and programming.

Increasingly the value of teaching computer coding to all students not just those headed to a career in computer programming is being recognized (Guzdial 2016; Howland & Good 2015; Papert 1980; Papert & Solomon 1972; Resnick et. al. 2009; Thompson et al. 2016b; Wing 2006). Research has already demonstrated the advantages of teaching computer coding to students with learning disabilities (Huffington Post 2016; Powell, Moore, Gray, Finlay and Reaney 2004). Thus, teaching students with dyslexia computer coding offers yet another approach to engaging the minds of struggling literacy learners through hands-on learning. One method for doing so employs blocks-based language commands (Morgado, Cruz, and Kahn 2006; Resnick et al. 2009; Semmett 1978). Students learn to program by issuing commands to create stories from combinations of ordered words (InfoWorld, 1980; Thompson and Tanimoto 2016), that is, the syntax of the natural language learning mechanism (Chomsky 2006).

Thus, although explicit instruction in language by hand and language by eye may be necessary to teach literacy skills as shown in prior research, such instruction may not be sufficient to ensure that struggling writers and readers become successful, especially if the struggling learners have lost hope they can overcome their chronic struggles or do not pay attention to and engage in the computerized instruction which is not the same as a computer game (Thompson et al. 2016a). For these reasons the current study incorporated both hope stories as in the initial hybrid studies with human teachers and computers, and the learning activities taught only by the computer teacher that aimed literacy instruction at all levels of language. However, to facilitate hands on intellectual engagement, computer coding learning activities were introduced for the first time in this programmatic line of research on treating persisting dyslexia in the upper grades.

Specific Aims and Design of Current Research Study

The first research aim of the current study was therefore to evaluate the effectiveness of incorporating computerized lessons for explicit reading and writing instruction, hope theme stories, and computer coding employing blocks-based language programming in each of 12 intervention sessions for students with diagnosed persisting dyslexia. The computerized lessons were a modification of prior computerized lessons that focused at the subword level on handwriting writing skills, at the word level on reading and spelling skills, and at the text level on reading comprehension or written sentence construction (prior text-level reading-writing or listening-writing learning activities were omitted).

To instill in the participants a belief that they could overcome their chronic struggles with reading and spelling and motivate them to keep trying, not only during this study but as they continued in their educational journeys after the study, the life of Buckminister Fuller was used as the hope theme (Fuller 1963 Fuller 1972; Fuller, Fuller, Agel and Flore 1970). In each session Bucky Stories, based on the life of Fuller, who overcame early sensory and motor disabilities and ongoing educational struggles throughout his schooling to make significant contributions to humanity as an adult, were read and discussed. Participants could interact socially and discuss with others their emotional issues in dealing with dyslexia. Finally, for hands-on engagement, each session included activities specially designed to teach the language of computer coding in reference to the syntax of natural language used in story construction.

Effectiveness of this multi-component intervention engaging sensory and motor, language, social emotional, attention/executive function, and cognitive systems of the learners was evaluated on the basis of whether they improved significantly on normed tests for grade or age from before to after the 12 lessons in

hallmark deficits in dyslexia—oral decoding of written pseudowords, which are pronounceable but have no semantic meaning, and written spelling of pronounced real words;

phenotype skills (behavioral markers of genetic and/or brain variables) related to dyslexia and/or needed to learn read and spell English, a morphophonemic orthography; and

syntactic skills for heard, spoken, written, and read language.

Syntactic skills were of interest for five reasons: (a) listening to what is heard in instructional talk and storing the syntax structures in working memory to process and comprehend it are related to learning across the content areas of school curriculum (academic register); (b) expressing one's thoughts in oral syntax is necessary for participation in classroom discussions; (c) written composition requires construction of both sentence syntactic structures and text organization of multiple sentences; (d) reading comprehension requires understanding not only word meaning and text content and organization but also single sentences; and (e) the computer coding employing blocks-based language programming featured constructing sentences to tell stories. Phenotype skills of interest included component working memory phenotypes identified in genetics and brain research as associated with dyslexia that support language learning: word-form coding for storing and processing heard and spoken words (phonological coding) and read and written words (orthographic coding); the orthographic loop that links internal orthographic codes for word-specific spellings with the serial finger movements involved in production of word-specific spellings and can be assessed by how many legible letters are written in alphabetic order from memory in 15 seconds, and supervisory attention of working memory for focusing on what is relevant and inhibiting what is irrelevant (for review, see Berninger and Richards 2010). Also of interest was morphological coding, which although not a hallmark impairment in dyslexia, has been shown to be necessary in treatment of dyslexia in English morphophonemic orthography (Berninger, Winn et al. 2008).

The second research aim was to compare overall performance on accuracy of answering comprehension questions for one word at a time versus one added word at a time on the reading comprehension questions. Overall accuracy on comprehension questions administered following these two contrasting, alternative modes of sentence presentation (alternating across the 12 sessions) in a text reading comprehension learning activity was compared.

The third research aim was to analyze frequency of correct coding on three aspects of the computer programming activities: loop, function, and conditional.

The fourth research aim was to observe students during the discussions of the hope stories and survey their perspectives on the computer coding activities in keeping with ongoing work on seeking the perspectives of the learner in improving instruction (Berninger, Geselowitz and Wallis in press). Of interest was whether adding hope stories and hands-on computer coding activities was associated with signs of improved motivation, paying attention, and engagement in language learning activities than in past studies providing computerized lessons with explicit language instruction without hope stories and computer programming activities.

Method

Participants

Ascertainment

Participants were recruited through flyers distributed to local elementary and middle schools in school districts within driving distance of the university where the research was conducted. The flyers announced an opportunity to participate in a study for students with persisting specific learning disabilities (SLDs) above grade 4 such as dyslexia. For parents who contacted the university research team an initial interview was conducted over the phone using a scripted set of questions approved by the university's institutional review board. The purpose of this interview was to determine if the reading and spelling problems might not show the typical profile associated with dyslexia but rather be the result of pervasive developmental disability, neurogenetic disorders like fragile-X, neurofibromatosis, or phenylketonuria, sensory disorders like significant hearing or visual impairment, motor disorders like cerebral palsy or muscular dystrophy, spinal cord or brain injuries, substance abuse, and medical conditions like epilepsy or other seizure disorders, etc. (see Batshaw, Roizen and Lotrecchiano 2013). Attention deficit and/or hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), which sometimes but not always co-occurs with dyslexia, was not an exclusion criterion. Also, questions were asked about developmental and educational history, including whether the child in past or currently showed signs of persisting struggle with some aspect of oral language (i.e., listening comprehension or oral expression) or written language (i.e., reading words, reading comprehension, handwriting, spelling, or composition) despite help at and/or outside school. An appointment was scheduled for formal pretesting at the university, if based on the phone interview, the child did not appear to have one of the exclusionary disorders or oral language problems during the preschool years; and the word reading and spelling problems were first noted in kindergarten or first grade but persisted into the upper elementary grades despite early intervention at and/or outside school in the early grades.

Diagnosis of dyslexia

If the parent granted informed consent and the child granted assent, as approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the university, assessment with a test battery described in the methods of the current study was conducted in keeping with the ethical principles of the American Psychological Association. While the participating student completed the test battery given in a standard order across participants, the parent completed questionnaires about developmental, medical, family, and educational histories and child's current functioning at and outside school. This test battery included the Verbal Comprehension Index (VCI), a measure of cognitive-oral language translation ability, which had to fall at least within the lower limits of the average range (25th percentile) because VCI tends to fall below 25th % tile in many other disorders but not in dyslexia that is specific to word level decoding and spelling. VCI was given only at pretest and is not reported in Table 1 which is specific to changes in pretest and posttest scores.

Table 1. Pretest Posttest Scores for Hallmark Impairments in Dyslexia (Word Decoding and Spelling), Subword Handwriting, Aural, Oral, Written, and Read Syntax (Sentences), and Working Memory Phenotypes Related to Dyslexia.

| Measure | Pretest M (SD) | Posttest M (SD) | df | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WJ 3 Word Attack | 91.14 (17.02) | 97.79 (10.09) | 12 | −2.64 | .03 |

| TOWRE Phonemic | 89.07 (13.01) | 95.43 (13.41) | 12 | −2.47 | .028 |

| WIAT 3 Spelling | 84.86 (9.54) | 90.64 (9.19) | 13 | −2.36 | .035 |

| DASH Copy Best | 8.21 (3.20) | 14.64 (3.46) | 13 | −8.13 | . 001 |

| DASH Copy Fast | 7.57 (3.50) | 14.21 (4.14) | 13 | −7.14 | .001 |

| PAL II WM Sentence Listening | 13.15 (2.79) | 16.00 (1.83) | 13 | −3.75 | .003 |

| CELF 4 Formulated Sentences | 12.08 (1.38) | 13.46 (0.97) | 12 | −2.64 | .022 |

| WJ 3 Writing Fluency | 95.50 (13.89) | 103.86 (14.68) | 12 | −2.64 | .001 |

| WJ 3 Passage Comprehension | 97.50 (19.16) | 102.21 (11.81) | 12 | −1.38 | .19 |

| CTOPP Nonword (Phono Coding) | 8.00 (1.52) | 9.07 (1.90) | 12 | −1.67 | .119 |

| PAL II Expressive Coding (Ortho) | 6.77 (.342) | 8.23 (2.92) | 13 | −.237 | .035 |

| Comes From (Morpho Coding) | 0.24z (0.51) | 0.50 (0.34) | 13 | −2.15 | .051 |

| Alphabet 15 raw (orthographic loop) | 9.00 (0.25) | 12.57 (4.20) | 13 | −5.28 | .001 |

| D-KEFS Color Word Inhibition | 9.29 (4.05) | 11.36 (2.95) | 12 | −2.35 | .02 |

Means (M), Standard Deviations (SD), and within participant t-tests across time.

Students were diagnosed with dyslexia if their performance on at least two word-level reading (real words or pseudowords) or spelling measures fell below the 50th percentile and at least one standard deviation below the Verbal Comprehension Index (VCI) on the Wechsler scales, and there was parent reported history of past and current persisting word reading and/or spelling problems despite prior help at and/or outside school. The component working memory phenotypes were not employed for determining assignment to SLD groups, but were assessed because of considerable interdisciplinary evidence that they tend to be lower in children with dyslexia than typical readers and spellers (Berninger and Richards 2010).

Sample demographics

Altogether 6 females and 8 males (N=14, ages 9 to 12, M=10 years 3 months) completed the comprehensive assessment battery and the computerized lessons. Their verbal cognitive abilities ranged, as is typical in those with dyslexia, from the average range (104) to very superior range (140) on the WISC IV Verbal Comprehension Index (VCI) (Wechsler 2003) (M=116.57; SD=12.24). Reported ethnic identities were representative of the region where the research was conducted: White (n=8), Asian (n=1), Black or African American (n=2), and n=3 who did not report ethnicity. Regarding mother's education, 6 reported some college, 4 indicated more than college, and 4 did not provide the information.

Assessment for Evaluating Effectiveness of Multi-Component Intervention

Hallmark impairments in dyslexia (word-level language skills)

To assess accuracy of phonological decoding, the WJ III Word Attack subtest (Woodcock et al. 2001) was given. The task (test-retest reliabilities range from 0.73 to 0.81) is to pronounce written pseudowords on a list. The total raw score (an indicator of accuracy of decoding) is converted to a standard score (M = 100 and SD = 15). To assess rate of phonological decoding, the Pseudoword Efficiency on the TOWRE (Torgesen et al. 1999) was given. The task (test-retest reliability is 0.90) is to read a list of printed pronounceable non-words accurately within a 45-second time limit. Total accuracy within time limit (an indicator of decoding efficiency) is converted to a standard score (M = 100 and SD = 15). To assess spelling written words, the Spelling subtest of the Wechsler Individual Achievement Test, 3rd Edition (WIAT III) (Pearson 2009) was given. The task (test-retest reliability 0.92) is to spell in writing dictated real words, which the examiner first pronounced alone, then in a sentence, and then alone. The total raw score is converted to a standard score (M = 100 and SD = 15), an indicator of accuracy of dictated spelling.

Subword handwriting skills

Handwriting was assessed because dysgraphia (impaired handwriting) may co-occur with dyslexia and because it is relevant to written language learning activities in which those with dyslexia engage, whether with pen/cil and paper or stylus and screen of a laptop. To assess handwriting in the context of words in a sentence, the Detailed Assessment of Speed of Handwriting (DASH) Copy Best and Copy Fast (Barnett, Henderson, Scheib and Schulz 2007) were given. The task is to copy a sentence with all the letters of the alphabet under contrasting instructions: one's best handwriting or one's fast writing (interrater reliability .99). Students can choose to use their usual writing—manuscript (unconnected) or cursive (connected) or a combination. Note that even though the task is to copy letters in word and syntax context, the scaled score (M=10, SD=3), is based on legibility for single letters within the time limits. In the current study, two testers reviewed all the scored handwritten measures to reach consensus on scoring.

Aural and oral syntax in language by ear and mouth

To assess processing of syntax in language by ear, the Process Assessment of the Learner, Second Edition (PAL II) (Berninger 2007) was given (test-retest reliability .87). Beginning with a single sentence and increasing the number of sentences (from 2 to 4), the examiner orally reads each sentence in an item set, asks a process question to assess comprehension of the sentence/s, and records the student's repetition of each sentence and assesses for accuracy. Items are administered until the discontinue criteria are met; raw scores are converted to scaled score (M=10, SD=3). To assess production of syntax in language by mouth, the Clinical Evaluation of Language Function 4th Edition (CELF IV) (Semel, Wiig and Secord 2003) Formulated Sentences subtest was given (test-retest reliability range from 0.62 to .71). The task is to construct an oral sentence from a provided word. The score is number correct, which is converted to a scaled score (M = 10 and SD = 3).

Read and written syntax in language by eye and by hand

To assess syntax in reading comprehension, the WJ III Passage Reading Comprehension subtest (Woodcock et al. 2001) was given. This cloze task (test-retest reliability is 0.85) is to supply orally a missing word in the blank that fits the accumulating sentence syntax in the context of the preceding text. Total accuracy is converted to a standard score (M = 100 and SD = 15). To assess syntax constructed in written composition, the WJ III Writing Fluency subtest of the (Woodcock et al. 2001) was given. The task is to compose a written sentence for each set of three provided words, which are to be used without changing them in any way. There is a 7 min time limit. The score, which is the total number of syntactically correct sentences composed in writing within the time limit, is converted to a standard score (M = 100 and SD = 15) for which test-retest reliability is 0.88.

Phenotypes (behavioral markers of genetic and/or brain bases) for dyslexia

To assess the word form storage and processing for heard and spoken words (phonological coding), the Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing (CTOPP) (Wagner, Torgesen and Rashotte 1999) Nonword Repetition was given. The task (test-retest reliability 0.70) is to listen to an audio recording of nonwords, which are pronounced one at a time and then repeat exactly the heard oral nonword, which contains English sounds but has no meaning. The raw score is converted to a standard score (M = 100 and SD = 15). To assess the word form storage and processing for read and written words (orthographic coding), PAL II Expressive Coding (Berninger 2007) was given. The tasks (test-retest reliability 0.84) are to view a briefly displayed written word and then from memory to write all the letters in word, a letter in a designated word position, or a letter group in designated word positions. The raw score based on the three tasks is converted to a scaled score (M=10 and SD=3).

For integrating internal representations of alphabet letters and their production through sequential finger movements (orthographic loop), alphabet 15, a rapid automatic letter writing task, was given. The task (interrater reliability 0.97) is to print the alphabet in lower case manuscript (unconnected) letters so that others can recognize the letters but write as quickly as possible. The score is the number of legible letters in correct alphabetic order in the first 15 seconds, which is converted to a z-score based on research norms for grade. The number of letters in the first 15 seconds is an indicator of automatic access, retrieval, and production, after which controlled, strategic processing regulates access, retrieval, and production. See Shiffrin and Schneider (1977) for distinction between initial automatic and subsequent controlled processing.

To assess focused attention, that is, the ability to inhibit irrelevant information and attend only to relevant information, the Color Word Form Inhibition subtest of the Delis Kaplan Executive Functions (D-KEFS) (Delis, Kaplan and Kramer, 2001) was given. The task (test- retest reliability 0.62 to 0.76), based on the classic Stroop task, is to read orally a color word in black ink and then name the ink color for a written word in which the color of the ink conflicts with the color name of the word (e.g., the word red written in green ink). The difference in time for reading the words in black and naming the color of the ink that conflicts with the name of the color word is an index of focused/selective attention. Raw scores are converted to scaled scores for age (M = 10 and SD = 3).

Morphological coding needed for learning to read and spell English morphophonemic orthography

To assess word form storage and processing for affixes signaling derivation of a word from another word (morphological coding) in heard and read words, a version of the Comes-From test was given (Nagy, Berninger and Abbott 2006; Nagy, Berninger, Abbott, Vaughan and Vermeulen 2003). The task is to judge whether or not a word is derived from a base word. Examples include the following: Does corner come from corn? Does builder come from build? In both cases the first word contains a common spelling (er), but only in the second example does it function as a morpheme (a suffix that transforms a verb or action word into a noun or person word). Raw scores are transformed to z-scores (M = 0 and SD = 1) based on research norms for elementary and middle school grades (test-retest reliability for a one-year period is 0.67).

HAWK© Lessons

Sessions always began with iPad computerized learning activities in handwriting, followed by computerized learning activities for word reading and spelling, and concluded with syntax comprehension and construction learning activities. The last set included reading sentences one word at a time versus one added word at a time mode of serial sentence presentation in multi-sentence texts and for which multiple choice questions assessed comprehension of those texts.

For the current study, the handwriting lessons in Letters in Motion in iteration 4 of HAWK© (Thompson et al., 2016) were used again for both manuscript (first six lessons) and cursive (last six lessons). Learning activities included (a) watching letters form between lines on the screen; viewing and tracing with stylus letters forming on screen stroke by stroke and closing eyes and seeing letter form in mind's eye; (b) study motion of letters forming one stroke at a time with numbered arrows cues in different colors and closing eyes and seeing sequential steps of letter formation; (c) writing letters named by computer teacher from memory by stylus; (d) hitting done button and using paper and pencil outside the iPad to write the whole alphabet from memory in alphabetic order in the format practiced in just completed lesson; this alphabet writing was kept in writing portfolio to assess response to instruction (RTI). The computer screen provided feedback regarding total time for completing the handwriting activities which the student recorded on RTI form also kept in writing portfolio.

For the current study, eleven learning activities from iteration 4 of Words in Motion©: (Thompson et al. 2016a) were included: pattern analyzer for heard words—syllables; pattern analyzer for heard words—phonemes; musical rhythm of words (within word stress pattern); pattern analyzer for written words; combining two words to shorten them; combining two words to lengthen them; deciding whether spelling units are true affixes; cross-code matrix in spelling direction (phoneme-grapheme correspondences); creating word-specific spellings in mind's eye; paying attention to letter order and letter position in written words; and choosing correctly spelled words. At completion of all learning activities feedback regarding accuracy of performance was provided for all learning activities except shortening and lengthening words and cross-code matrix for spelling to record on RTI form in writing portfolio. However, at end of all learning activities students were asked to spell with pencil and paper dictated words showing they could apply what was taught and practiced in the cross-code spelling matrix; the dictated words were kept in the writing portfolio to asses RTI. Note that although alphabet principle was taught only in the spelling direction, all the other learning activities facilitate word reading as well as spelling.

For the current study, seven syntax learning activities from iteration 4 of Minds in Motion© (Thompson et al., 2016a) were included: musical melody of sentences (prosody), combining words to create meaning, adding glue words (function words—prepositions, conjunctions, pronouns) to glue content words (nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs) together in syntax; choosing sentence word order; changing sentence word order, choosing spellings that fit sentence context; using conjunctions to combine clauses. Students recorded feedback on the screen provided at the end of each learning activity on RTI forms in their writing portfolio. However, all learning activities for “read source text -write notes and summaries” and “listen to heard source text-write notes and summaries” in iteration 4 were omitted and replaced with new reading comprehension activities for which the mode of presentation alternated across sequential lessons: one word at a time (lessons 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11) and one added word at a time (lessons 2, 4, 6, 8, 10. 12). The texts for these reading comprehension activities were the source texts for the reading-writing activities in iteration 4 but were presented in sentence units rather than whole text units as in iteration 4. The content of the first six texts was about the world history of math. The content of the last six texts was about world geography and cultures. At completion of reading all the sentences in a source text, five multiple choice questions appeared one at a time to assess comprehension. The computer platform computed the accuracy of answering these multiple choice questions for each source text, displayed them as feedback to record on RTI form, and stored the data for future analyses that compared percent accuracy for one word at a time mode of presentation (6 lessons) versus one added word mode of presentation (6 lessons).

At the end of each session teachers reviewed the RTI forms and alphabet writing and dictated spelling activities in the writing portfolios with the students and their parents to assess response to instruction from lesson to lesson. The RTI forms provided visible records for assessing progress from lesson to lesson.

Bucky Stories

Following completion of the computerized writing and reading lessons, children read silently the written version of the Bucky story for the lesson (in their portfolio with a picture of Buckminister Fuller and a geodesic dome on the cover) while the teacher read the story aloud to the group. The content of the stories was based on Fuller (1963, 1972) and Fuller et al. (1970). Based on Buckminister's nickname, Bucky, which he was given early in life before entering school, the titles were Bucky Stories, 1 through 12. Following the reading of the Bucky story for the lesson, questions were posed by the teacher and by the participating children for oral discussion among the whole group and sharing of multiple opinions and perspectives. As explained next the content of these stories was written to create a hope theme that individual students can overcome early challenges and ongoing struggles to achieve personally and also contribute meaningfully to the lives of human beings in the world.

Bucky Story 1 was about his birth and the eyesight and walking problems he faced early in his development. His early fascination with exploring the external world outside the school environment was discussed.

Bucky Story 2 described his struggles in elementary and high school and college. He was expelled twice from Harvard. Bucky was more interested in inventing machines in mills and rescue boats for the navy than learning in a school environment.

Bucky Story 3 was about Bucky's marriage and birth of his first daughter. This joy was offset by the company where he worked failing and thus loss of his job, and his daughter becoming paralyzed and dying. During the next two years he lived alone and had a vision of how technology could improve the human condition and make the world a better place for all people.

Bucky Story 4 illustrated how joy can follow sadness. After the birth of a second daughter, Bucky began to realize his mental vision for humanity by becoming an architect committed to creating housing for low-income people.

Bucky Story 5 was about becoming involved in manufacturing geodesic domes, which like earth are spheres, but are composed of four triangles. Bucky had created his own geometry to use in housing, the military, and playground equipment.

Bucky Story 6 was about his creation of a Dymaxian Map in which the three-dimensional world is represented in a two-dimensional surface.

Bucky Story 7 was about the book Buckminster Fuller wrote, Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth, which encourages humans to think and work together peacefully for the benefit of all humanity.

Bucky Story 8 shared Bucky's insight that people on earth are really passengers on a spaceship traveling in the earth's outerspace in the larger universe.

Bucky Story 9 was about his theory of writing—run on sentences and compound words with multiple prefixes and multiple suffixes—render writing more creative. He not only wrote over 20 books but also poetry.

Bucky Story 10 was about his fascination with algebra equations for the lines and points in geometric patterns. His equation for geodesic lines can be used to calculate synergy—how in a whole system the sum is greater than the parts from which special properties emerge.

Bucky Story 11 was about Bucky's belief that the human species is on earth to provide comprehensive thinking about how the parts and whole of the universe work together. He was interested in how such thinking could be applied to improving the lives of the whole human race, but especially the more than half living in poverty.

Bucky Story 12 reviews the many accomplishments of Buckminster Fuller who was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom just before his death at 88. After his death, other scientists won the Nobel Prize for discovering a molecule with a geodesic structure, which they named after Buckminister Fuller to honor his contributions using this geometric pattern to improve life of humanity.

Representative questions posed by the teacher to stimulate discussion included the following: Would you have predicted that a boy with visual and motor disabilities who struggled throughout his schooling would achieve what Buckminister Fuller did by persisting across his lifetime? Why is it important that you believe in yourself and never stop thinking about helping others? Do you know anyone who is more interested in learning outside school than in school? Do you have any ideas how school could be made more interesting for students who learn best through “hands-on activities”? Bucky believed the minds' vision was as important as the eye's vision in making the world a better place for all people. What is your vision for how the world can be a better place for all children?

Kokopelli's World (KW)©

Finally, the children engaged in computer coding and programming grounded in human language as well as computer concepts and constructs. Kokopelli in Kokopelli World (KW)© is a contemporary version of a character in Native American Culture who dances and plays the flute. In iterations 1, 2, 3, and 4 he danced with delight to signal the completion of a learning activity. In KW he is the main character in the world that is controlled by issuing directions for computer coding using natural English language. KW contains a set of lessons in a blocks-based online programming environment derived from Google Blockly that teaches introductory programming concepts and constructs and was designed to be used with HAWK© literacy learning activities. KW is more similar to English language than programming languages often are in that the program is framed in terms of a programmer creating stories (programs) sentence by sentence that are told by the computer. Most activities are presented as a puzzle or game in which the programmer creates the stories by assembling groups of blocks. However, the sentences represented by block groups are not necessarily direct in the second person (grammatical) as typically used in programming languages, but may be indirect in third person. See coding area in the middle of Figure 1 using words in the menu on the left of Figure 1. Stories in KW may be interactive, allowing an audience member to affect the course of the story. The answer to the question codes the direction in which Kokopelli moves in the microworld on the right of Figure 1. Also, KW uses the present rather than the past tense in creating the stories. Use of variables is avoided. Rather, simple nonnumeric predicates are used for conditional statements (If…then) or predicates and constants in the case of loops. See Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Kokopelli's World© Programming Environment. The menu is on the left, the coding area is in the middle, and the microworld is on the right. The activity's instructions are at the top of screen.

Figure 2.

Control blocks in Kokopelli's World© from top to bottom: loop, conditional, and direction.

Altogether across the twelve lessons participants complete 74 learning activities involving coding and programming. Each learning activity in a lesson has a text- and audio-introduction with instructions for the next programming activity. Kokopelli is usually the main character in KW stories and introduces new characters in the story, but the student may include introductions of another actor, Raven, or dramatic “properties” in the story. Including the End block after a group of sentences at the end signals the story is complete but is generally not required in a KW story. A program can be converted into a plain text or oral text spoken aloud by the computer.

The initial code window may be blank or include some starter code. The starter code consists of some instances of blocks from the activity's menu, and these instances are generally the only blocks the student is expected to use in that activity. Each activity has an internal set of checks that are used by the lesson control software for determining whether the activity is completed or not. These lesson control software checks can include examining the final state of the program, or looking for the presence of key blocks or structures in the student's code. If a program passes all the checks when it is executed, the student is allowed to continue on to the next activity. When a program that has been executed does not meet all of the requirements, the student is given a hint based on the check that failed. Each activity also has an internal time limit. If the student has not created a program that satisfies the requirements in that amount of time, he or she is typically allowed to continue. This policy helps to avoid student frustration.

The KW software logs individual actions students perform, such as creating or deleting blocks, connecting or disconnecting them, and moving them around the screen. These data records are stored on a server. Full copies of their programs are also captured and stored whenever their programs are executed. The logs serve two purposes: (a) allowing the possibility of sharing of programs (and stories or games that they represent), and (b) facilitating data analysis by the research team at a later time to address the research questions.

Each lesson in KW focuses on one or more key concepts. The lessons generally build on each other and increase in conceptual complexity over the course of the twelve lessons. The lesson topics are the following:

Sequences of blocks and microworld motion in the cardinal directions

Simple actions, such as dancing, eating

Coordination and control of multiple story characters

Complex actions, such as picking things up, dropping them

Conditionals, such as, if “Raven is near the rock”

Loops with fixed numbers of iterations

Nested conditionals

Nested loops

User-defined Functions

User (runtime) input through direction blocks

Simple games

Randomness

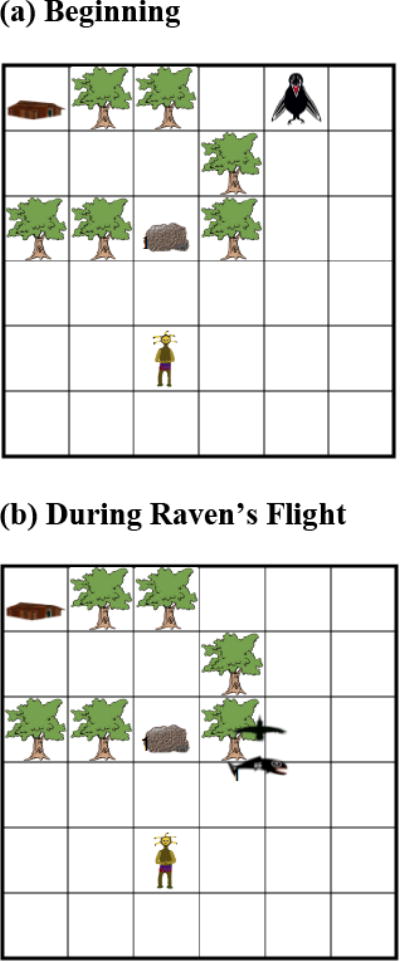

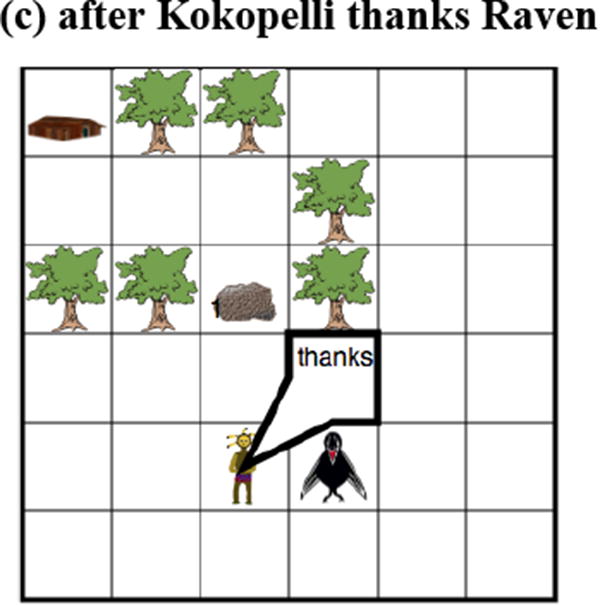

In the last lesson, students have reached a level at which they can complete a partially-written interactive story. The player controls Kokopelli's movements, while Raven, another character in KW, moves randomly. As a game, the player tries to make Kokopelli eat as many of the berries as possible before Raven gets to them. The game aspects are illustrated in Fig. 3. Also see an example of a completed coded story in Figure 4 and the three screens in Figure 5 that display the sequence of story construction for coding in this programming environment.

Figure 3.

A game in Kokopelli's World©, in which the player (controlling Kokopelli) and Raven (moving randomly) have a race to eat more berries than the other.

Figure 4. One student's original coded story about Raven delivering a salmon to Kokopelli.

Figure 5.

Screens of the child's story in execution. (a) beginning, (b) during Raven's flight, and (c) after Kokopelli thanks Raven.

Data Analyses

To address the first research aim, a repeated measures (within participant) design was used to evaluate significant change from pretest to posttest on the measures in the assessment battery. A series of correlated t-tests were performed. Of interest was whether there was significant improvement on each of the three hallmark impairments (accuracy and rate of phonological decoding and spelling from dictation), on each of the syntax measures, and each of the phenotype measures related to dyslexia. One posthoc analysis of covariance was also conducted (see Results). Morphological coding relevant to learning to read and spell English morphophonemic orthography was also assessed. To address the second research aim, average accuracy of performance on comprehension questions was compared for the alternating six one-word at a time and the six one-added word modes of presentation of sentences. To address the third research aim, the frequency of correct coding and incorrect coding on computer programming activities for loop, function, and conditional was inspected. To address the fourth research aim, students were observed by the third, fourth, fifth, and tenth author during the computer language learning activities, discussions of the hope studies, and participation in the computer coding activities; and the first two authors administered a survey and interview about the children's perspectives on the computer coding and programming activities. Of interest were indicators of participants' attention and engagement in the computerized language lessons and in the computer coding and programming activities and of motivation issues that were discussed in reference to the hope stories.

Results

Pretest-Posttest Changes on Normed Assessment Measures

Table 1 summarizes the means and standard deviations at pretest and posttest and results of correlated t-tests comparing the pretest and posttest scores for each measure in the assessment battery given before and after participating in the 12 intervention sessions. Significant improvement from pretest to posttest was found at conventional levels of statistical significance (two-tailed) for all measures related to the hallmark impairments in dyslexia (two decoding/reading measures and one encoding/spelling measures), three of the four syntax measures—language by ear, by mouth, and by hand; and the phenotype measures for dyslexia— orthographic coding, orthographic loop, and focused attention as well as morphological coding relevant to reading and spelling words in English, a morphophonemic orthography. Together, these results are relevant to the first research aim regarding the effectiveness of the intervention.

However, also relevant to the first research aim, each of the decoding measures was used for two reasons as a covariate in follow-up analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) for WJ 3 Passage Comprehension. First, one hallmark impairment in dyslexia is decoding. Second, the t-tests had shown significant improvement on both decoding measures but not reading comprehension (WJ3 Passage Comprehension) when individual differences in decoding that can affect reading comprehension are not considered. ANCOVA showed the time effect was statistically significant, M=97.50, SD= 19.16, M=102.21, SD=11.81, F(1, 12)=26.42, p<.001, eta2 =.688. When the covariate was WJ3 Word Attack, the interaction for time x accuracy of decoding was also statistically significant, F (1, 12)=23.16, p<.001, eta2 =.659. Likewise, when rate of decoding was the covariate (TOWRE Phonemic), the interaction for time x rate of decoding was also statistically significant, F(1,12)=7.03, p<.021, eta2=.370.

Comparison of Mode of Sentence Presentation for Reading Comprehension

Repeated measures ANOVA showed that the average performance on the reading comprehension checks was higher on the six lessons for one word at a time presentation, M=2.63 (SD=0.75) than on the six lessons for one added word at a time presentation, M=2.11 (SD=0.78), F(1,14) = 7.18, p=.018, eta2=.339. This finding is relevant to the second research aim and optimal mode of computer presentation of sentences for learning activities designed to improve reading comprehension of students with dyslexia in upper elementary or middle school grades.

Accuracy of Computer Coding for Programming

Table 2 summarizes the accuracy and inaccuracy for performing each of three kinds of computer coding in KW learning activities: loop, function, and conditional. These data are relevant to the third research aim specific to evaluation of response to KW coding and programming. Overall, the frequency of accurate performance exceeded that for inaccurate performance for each of the three coding/programming constructs. Nevertheless 12 lessons were not sufficient for reaching mastery without any inaccuracies. It should also be noted that the logical demands of the conditional block may seem more difficult to them than loops; hence conditional was rarely used and loop was used most frequently.

Table 2. Number Correct and Number Incorrect Coding in Kopelli's World.

| Construct | Number Correct | Number Incorrect | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loop | 23 | 10 | 33 |

| Function | 3 | 5 | 8 |

| Conditional | 1 | 0 | 1 |

Attention, Engagement, and Motivation

All the teachers during the intervention sessions had been involved in prior intervention studies with HAWK© and were amazed at how in the current study they did not have to monitor paying attention and engaging in the computerized language learning activities or remind students to focus attention and stay on task, as they had to do frequently in prior instructional studies without (a) discussions of hope stories and sharing personal struggles in learning with others having similar struggles, and (b) hands-on engagement in computer coding and programming. The hope stories and computer coding/programming appeared to increase motivation to learn as well. Students arrived at the after school program, enthusiastically went to their lap top with identifying portfolio, and were eager to begin learning. None were reluctant and had to be encouraged to begin.

Participant Responses on Survey about Kokopelli's World

Of the 11 who completed the written surveys, seven reported prior experience with coding (4 with scratch). When asked which computer activities they enjoyed the most, 7 reported coding, 2 reported reading, 1 had no preference liking all the activities equally, and 1 response was not related to the computer activities in the lessons. When asked which control block in the computer coding was their favorite, most liked the loop block best because it was “easier”, “more interesting”, or “saved them from creating extra code” However, a few liked the function definition best because they could name the function whenever they wanted. See Appendix for their perspectives on preferred writing format.

Discussion

Significance of Findings

Explicit instruction in reading is necessary but not sufficient for students with persisting dyslexia during middle childhood and early adolescence. Explicit instruction in spelling is also needed. Although alphabetic principle was taught only in the spelling direction (phoneme → grapheme) rather than reading direction (grapheme → phoneme), students with persisting dyslexia improved in oral decoding accuracy and rate for reading as well as spelling. These findings add to existing research showing that students with specific learning disabilities benefit from both spelling and reading interventions (Wanzek, Vaughn, Wexler, Swanson, Edmonds and Kim 2006). Following computer instruction in handwriting by stylus, they also improved in their handwriting skills for letter formation in the context of words and sentences whether the copy task requirements required one's best or one's fast handwriting. This finding provides converging evidence for the construct validity of these handwriting assessment measures (Barnett, Henderson, Scheib and Schulz 2009). Such handwriting skills can also support the spelling that students with dyslexia need to complete school written assignments successfully.

Also, during middle childhood and early adolescence, explicit instruction in phonological skills is necessary but not sufficient for students with dyslexia. Students with dyslexia also benefit from explicit instruction in orthographic coding, orthographic loop, and morphological coding and strategies for focusing attention on relevant language cues, that is, they can respond to such instruction even though their struggles have persisted despite other past and current intervention. At the syntax level of language both relative weaknesses in reading comprehension and written composition and relative strengths in listening comprehension and oral expression can improve in response to computerized instruction for these language skills and language-based computer coding and programming activities for creating stories sentence by sentence. Effective ways to supplement computerized explicit instruction in writing and reading for students with persisting dyslexia are to (a) discuss hope stories with peers also dealing with dyslexia to motivate them through stories of others who have successfully overcome chronic struggles in language learning, and (b) participate in hands-on, cognitively engaging, language-based computer coding and programming to create stories from words and syntax.

Limitations

This study used a design experiment method—combining multiple instructional components (explicit levels of language instruction close in time, hope stories, and language-based computer coding and programming)—to achieve a desired outcome (improvement in hallmark impaired word decoding and spelling skills in dyslexia, syntax skills for language by ear, mouth, eye, and hand, and hallmark phenotype impairments in dyslexia). The effectiveness of this multi-component instructional intervention can be evaluated using repeated measures statistical analyses of changes in the same participant, who serves as own control, from before to after participation in the intervention; but causal influences about which single component caused a specific change from pretest to posttest cannot be made. Rather the changes from pretest to posttest are the result of the combination of the multiple components designed to achieve a desired outcome over a relatively short intervention (12 lessons during winter and spring of the school year). Also, this computer intervention study for dyslexia was conducted in a university research setting rather than a school setting and after a day at school when participants may have been tired even though they participated enthusiastically. However, emerging use of on-line presentation of lessons offers the promise of participating in the lessons during the school day in school settings across longer time periods. In addition, the students were all speakers of mainstream English, but students who speak other dialects of English such as African American dialect also benefit from explicit spelling instruction (Pittman, Joshi, Carreker 2014).

Future Research Directions

Despite limitations, the findings provide proof of concept of the benefits of combining computerized written language lessons at multiple levels of language, hope stories, and hands-on computer coding and language blocks programming for story writing for students with persisting dyslexia. This approach might be extended in two ways. First, with growing interest in on-line instruction, all three activities in the current study could be offered in such on-line instruction, a vision of the first two and ninth authors through the Opt-Ed partnership for the two computerized activities (HAWK© and KW©). The Hope Stories could also be presented through ear phones as well as visually on a screen; and participating students could engage in internet-supported on-line discussion of inspiring stories of others overcoming struggles to achieve and contribute to society. Second, the on-line instruction could be provided for students with other kinds of learning disabilities as well as well as typically developing language learners who have also improved in response to HAWK© learning activities (Tanimoto et al. 2015) and might also benefit from KW©.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by HD P50HD071764 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and involved an interdisciplinary team. The first two authors developed the computer platform for HAWK™ and Kokopelli's World™. The third, fourth, and fifth authors were the teachers who worked with students using the computerized learning activities in the afterschool program. The sixth author administered and scored the pretest and posttest assessments. The seventh author and tenth author developed the contents of the comprehension checks for the one word at a time and one added word at a time and modified the content of prior versions to create the version of HAWK™ used in the current study. The eighth author analyzed all the results. The ninth author advised on research on hope and motivation and user-computer interface, and obtained a distribution agreement with the UW for disseminating HAWK™, and the tenth author wrote the Hope Stories and supervised the acquisition of sample and afterschool program.

Appendix: Survey on Perspectives of Students with Dyslexia Regarding Preferred Writing Format

Student 1 prefers to write on paper, bad at typing

Student 2 likes computer but likes paper format

Student 3 prefers pencil and paper for writing a story but using computer for writing assignments

Student 4 prefers paper for math to show work but computer for writing because of spell check and it goes faster

Student 5 prefers doing math and drawing by hand on paper but writing by typing on computers

Student 6 prefers paper because “I suck at typing.” But computer for studying because of its freedom and resources

Student 7 prefers paper for math likes to use the computer for typing and games

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The last author is author of PAL II used for the oral sentence working memory task and the expressive coding (orthographic) task.

References

- Abbott R, Mickail T, Richards T, Renninger A, Hidi S, Beers S, Berninger V. Understanding interest and self-efficacy in the reading and writing of students with persisting specific learning disabilities during middle childhood and early adolescence. International Journal of Educational Methodology. 2017 Jul;3(1):41–64. doi: 10.12973/ijem.3.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett A, Henderson L, Scheib B, Schulz C. Detailed assessment of speed of handwriting (DASH) copy best and fast. London: Pearson; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett A, Henderson S, Scheib B, Schulz J. Development and standardization of a new handwriting speed test: The Detailed Assessment of Speed of Handwriting. British Journal of Educational Psychology. 2009;6:137–157. [Google Scholar]

- Berninger V. Dyslexia an invisible, treatable disorder: The story of Einstein's Ninja Turtles. Learning Disability Quarterly. 2000;23:175–195. [Google Scholar]

- Berninger V. Diagnostic for Reading and Writing (PAL-II RW) 2nd. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation. Now Pearson; 2007. Process Assessment of the Learner. [Google Scholar]

- Berninger V. Highlights of programmatic, interdisciplinary research on writing. Learning Disabilities Research and Practice. 2009;24:68–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5826.2009.00281.x. NIHMS 124304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berninger VW. Interdisciplinary frameworks for schools: Best professional practices for serving the needs of all students. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/14437-002. Resources and Advisory Panel. All royalties go to Division 16 to support these websites and develop future editions. [Google Scholar]

- Berninger V, Abbott R, Cook C, Nagy W. Relationships of attention and executive functions to oral language, reading, and writing skills and systems in middle childhood and early adolescence. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2016:1–16. doi: 10.1177/0022219415617167. NIHMS 721063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berninger V, Geselowitz K, Wallis P. Multiple perspectives on the nature of writing: Typically developing writers in grades 1, 3, 5, and 7 and students with writing disabilities. In: Bazerman C, editor. The Lifespan Development of Writing. Chapter 5. Urbana, Illinois: National Teachers of English (NCTE) Books Program; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Berninger V, Nagy W, Tanimoto S, Thompson R, Abbott R. Computer instruction in handwriting, spelling, and composing for students with specific learning disabilities in grades 4 to 9. Computers and Education. 81:154–168. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2014.10.00. 2015, published on line October 30, 2014. NIHMS636683 http://audioslides.elsevier.com/getvideo.aspx?doi=10.1016/j.compedu.2014.10.005 PubMed http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4217090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berninger V, Nielsen K, Abbott R, Wijsman E, Raskind W. Writing problems in developmental dyslexia: Under-recognized and under-treated. Journal of School Psychology. 2008;46:1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2006.11.008. NIHMS 37383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berninger V, Richards T. Inter-relationships among behavioral markers, genes, brain, and treatment in dyslexia and dysgraphia. Future Neurology. 2010;5:597–617. doi: 10.2217/fnl.10.22. NIHMS 226931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berninger V, Winn W, Stock P, Abbott R, Eschen K, Lin C, et al. Tier 3 specialized writing instruction for students with dyslexia. Reading and Writing An Interdisciplinary Journal. 2008;21:95–129. Printed Springer On Line. May 15, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bruck M. Component spelling skills of college students with childhood diagnoses of dyslexia. Learning Disability Quarterly. 1993;16:171–184. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky N. Language and Mind. 3rd. New York: Cambridge Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Connelly V, Campbell S, MacLean M, Barnes J. Contribution of lower order skills to the written composition of college students with and without dyslexia. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2006;29:175–196. doi: 10.1207/s15326942dn2901_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delis D, Kaplan E, Kramer J. Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation/Pearson; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller B. Operating manual for spaceship earth. New York: E.P. Dutton & Co; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller B. Buckminster Fuller to children of earth. Garden City, NY: Doubleday; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller B, Agel J, Flore Q. I seem to be a verb. Bantam Paperbacks; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Guzdial M. Learner-centered design of computing education: Research on computing for everyone. Morgan & Claypool; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Howland K, Good J. Learning to communicate computationally with Flip: A bi-modal programming language for game creation. Computers & Education. 2015;80:224–240. [Google Scholar]

- Huffington Post. Coding allows learning disabled students to shine. 2016 Online at http://www/huffingtonpost.com/vidcode/coding-allows-learning-di_b_9586838.html.

- Idan O, Margalit M. Socioemotional self-perceptions, family climate, and hopeful thinking among students with learning disabilities and typically achieving students from the same classes. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2014;47(2):136–152. doi: 10.1177/0022219412439608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- InfoWorld. Software reviews: Spinnaker. 33. Vol. 6. InfoWorld; 1983. pp. 56–58. [Google Scholar]

- Katusic SK, Colligan RC, Weaver AL, Barbaresi WJ. The forgotten learning disability – Epidemiology of written language disorder in a population-based birth cohort (1976-1982), Rochester, Minnesota. Pediatrics. 2009;123:1306–13. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackaye T, Margalit M. Self-efficacy, loneliness, effort, and hope: Developmental differences in the experiences of students with learning disabilities and their non-learning disabled peers at two age groups. Learning Disabilities: A Contemporary Journal. 2008;6(2):1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lefly D, Pennington B. Spelling errors and reading fluency in dyslexics. Annals of Dyslexia. 1991;41:143–162. doi: 10.1007/BF02648083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon GR, Shaywitz S, Shaywitz B. A definition of dyslexia. Annals of Dyslexia. 2003;53:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Maughan B, Messer J, Collishaw S, Snowling MJ, Yule W, Rutter M. Persistence of literacy problems: Spelling in adolescence and at mid-life. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2009;50(8):893–901. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgado M, Cruz M, Kahn K. Radia Perlman—A pioneer of young children computer programming. Current Developments in Technology-Assisted Education. 2006:1903–1908. [Google Scholar]

- Niedo J, Lee YL, Breznitz Z, Berninger V. Computerized silent reading rate and strategy instruction for fourth graders at risk in silent reading rate. Learning Disability Quarterly. 37(2):100–110. doi: 10.1177/0731948713507263. 2014, May 2013, October 28 on line. NIHMSID #526584. PubMed Central (PMC) for public access May 1, 2015 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4047714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedo J, Tanimoto S, Thompson R, Abbott R, Berninger V. Computerized instruction in translation strategies for students in upper elementary and middle school grades with persisting learning disabilities in written language. Learning Disabilities A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2016;21:62–78. doi: 10.18666/LDMJ-2016-V21-I2-7751. NIHMS 836952 Pub Med https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5489131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen K, Haberman K, Todd R, Abbott R, Mickail T, Berninger V. Emotional and behavioral correlates of persisting specific learning disabilities in written language (SLDs-WL) during middle childhood and early adolescence. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. doi: 10.1177/0734282917698056. in press. NIHMSID 852098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papert S. Mindstorms: Children, computers, and powerful ideas. Basic Books; New York: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Papert S, Solomon C. LOGO Memo. Vol. 3. MIT. AI Lab: 1972. Twenty things to do with a computer. July 1971. Also in Educational Technology, April 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson. Wechsler individual achievement test. 3rd. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2009. [Google Scholar]