Abstract

Topical antimicrobials are widely used to control wound bioburden and facilitate wound healing; however, the fine balance between antimicrobial efficacy and non‐toxicity must be achieved. This study evaluated whether an anti‐biofilm silver‐containing wound dressing interfered with the normal healing process in non‐contaminated deep partial thickness wounds. In an in‐vivo porcine wound model using 2 pigs, 96 wounds were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 dressing groups: anti‐biofilm silver Hydrofiber dressing (test), silver Hydrofiber dressing (control), or polyurethane film dressing (control). Wounds were investigated for 8 days, and wound biopsies (n = 4) were taken from each dressing group, per animal, on days 2, 4, 6, and 8 after wounding and evaluated using light microscopy. No statistically significant differences were observed in the rate of reepithelialisation, white blood cell infiltration, angiogenesis, or granulation tissue formation following application of the anti‐biofilm silver Hydrofiber dressing versus the 2 control dressings. Overall, epithelial thickness was similar between groups. Some differences in infiltration of specific cell types were observed between groups. There were no signs of tissue necrosis, fibrosis, or fatty infiltration in any group. An anti‐biofilm silver Hydrofiber wound dressing did not cause any notable interference with normal healing processes.

Keywords: anti‐biofilm dressings, healing, partial thickness wounds, porcine model, silver

1. INTRODUCTION

Infection prevents healing in chronic and acute wounds, and in recent years, biofilm has been implicated as an additional complicating factor.1 Biofilm is now recognised as a key local barrier to wound healing2 and is considered a critical factor in wound chronicity.3 Consequently, wound management strategies increasingly need to target biofilm prevention and removal.4 Traditionally, dressings containing antimicrobial agents such as silver and iodine have been used in the management of locally infected wounds and those at risk of infection. However, as biofilm increases microbial tolerance to both topical antiseptics and systemic antibiotics, new anti‐biofilm approaches are required to reduce microbial tolerance and enhance activity of antimicrobial agents.

A silver‐containing Hydrofiber dressing containing anti‐biofilm technology has been introduced to help combat biofilm‐associated wound infections. The anti‐biofilm silver‐containing Hydrofiber (ABSH) dressing is an absorbent, antimicrobial dressing comprised of Hydrofiber technology, silver and anti‐biofilm excipients for use in patients with non‐healing wounds that may be compromised by biofilm.5 ABSH dressings have been shown to be effective in reducing biofilm mass as well as Staphylococcus aureus and Klebsiella pneumoniae bacterial cell counts in robust in vitro biofilm wound models.6 In a pre‐clinical study using a rabbit ear model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa wound biofilm, ABSH reduced bacteria counts and improved wound healing relative to controls.7 Clinical studies have demonstrated that ABSH dressings improve wound status and reduce exudate levels in previously non‐healing wounds and have an acceptable safety profile.8, 9, 10 Although the anti‐biofilm dressing has been shown to improve progression in recalcitrant, biofilm‐impeded animal and human wounds,7, 10 the current in vivo research was undertaken to investigate potential interference of the additional anti‐biofilm excipients on normal healing progression in non‐contaminated, acute partial thickness wounds compared with the same dressing without the anti‐biofilm excipients.

2. METHODS

2.1. Experimental animals and regulations

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The study was conducted in compliance with the University of Miami's Department of Dermatology and Cutaneous Surgery's Standard Operating Procedures. Animals were monitored daily for observable signs of pain and discomfort, and analgesics were used throughout the study. Two female, specific pathogen‐free pigs (B. G. Looper Farm, Granite Falls, North Carolina) weighing 40 to 45 kg were individually housed in accredited animal facilities (American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care) with controlled temperature (19°C–21 °C) and lighting (12 h light/12 h dark). The pigs were fed a basal diet ad libitum and were acclimatised in the animal housing facilities for at least 7 days prior to the start of the study.

2.2. Wounding

During preparation, wounding, and dressing application, the animals were sedated with Telazol (1.4 mg/kg), xylazine (2 mg/kg), and atropine (0.05 mg/kg) administered by intramuscular injection followed by a combination of isofluorane (Isothesia; Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, Illinois) and oxygen via mask inhalation. Prior to wounding, hair was removed from the flank and back of the animals using animal clippers, and the skin was washed with a non‐antibiotic soap and sterile water. Using a specialised electrokeratome, 48 wounds (12 mm × 12 mm × 0.5 mm deep) were made in the paravertebral and thoracic area for each pig, that is, a total of 96 wounds. Wounds were separated from 1 another by 3 to 5 cm of unwounded skin and were individually dressed within 20 minutes of wounding.

2.3. Dressing application

In each animal, wounds were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 dressing groups (16 wounds per group): the test ABSH dressing (AQUACEL Ag+Extra, ConvaTec Ltd, Flintshire, UK), a silver Hydrofiber (SH) control dressing (AQUACEL Ag Extra, ConvaTec Ltd), and an untreated control. Each test dressing (10 cm × 10 cm) was placed over 4 wounds and moistened with 3 mL of sterile saline. A polyurethane film (PUF) dressing (Tegaderm; 3M Healthcare, St. Paul, Minnesota) was applied to all groups to help maintain a moist environment, including the untreated control group (hereafter referred to as the PUF control). The dressings were then secured with surgical tape and the entire animal loosely wrapped with self‐adherent bandages (Coban; 3M Healthcare St. Paul, Minnesota).

2.4. Sample collection and histology analysis

Four wound biopsies from each animal were taken per dressing group on days 2, 4, 6, and 8 after wounding; that is, a total of 8 samples per group/per assessment day were analysed. Incisional biopsies were taken from the centre of the wounds and included normal adjacent skin on both sides. Samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, stained with haematoxylin and eosin and Giemsa. Slides were blindly evaluated by a dermatopathologist using a light microscope. The following parameters were evaluated11:

Percentage of wound epithelialised (%), determined by the length of wound surface covered with epithelium expressed as a percentage of the total length.

Epithelial thickness (cell layers μm), reported as an average of 5 measurements taken at equal distance points from each other in the biopsy.

White cell infiltrate, measured by the presence and amount of sub‐epithelial mixed leukocytic infiltrates and graded as follows: Mean Score: 1 = absent; 2 = mild; 3 = moderate; 4 = marked; and 5 = exuberant.

Inflammatory infiltration of specific cell types, scored as described in Table 1. Cell counts were performed under a high‐power field (400×).

Angiogenesis (presence of new blood vessels), graded as mean scores: 1 = absent; 2 = mild; 3 = moderate; 4 = marked; and 5 = exuberant.

Granulation tissue formation (dermis) was graded as follows: 0 = 0; 0.5 = 1 to 10%; 1 = 11 to 30%; 2 = 31 to 50%; 3 = 51 to 70%; 4 = 71 to 90%; 5 = 91 to 100%.

Tissue necrosis, fibrosis and fatty infiltration were scored as described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Semi‐quantitative scoring system for inflammatory cell infiltration and tissue responses

| Score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Cell typea | |||||

| PMN | 0 | 1–5 | 6–10 | Heavy | Packed |

| Lymphocytes | 0 | 1–5 | 6–10 | Heavy | Packed |

| Macrophages | 0 | 1–5 | 6–10 | Heavy | Packed |

| Giant cells | 0 | 1–2 | 3–5 | Heavy | Packed |

| Mast cells | 0 | 1–2 | 3–5 | Heavy | Packed |

| Tissue response | |||||

| Necrosis | 0 | Minimal | Mild | Moderate | Severe |

| Fibrosis | 0 | Narrow band | Moderate | Thick band | Extensive |

| Fatty infiltrate | 0 | Minimal | Several layers | Broad | Extensive |

Each cell type was counted under high‐power field (400×) of 10 fields and the mean value scored. PMN, polymorphonuclear leukocytes.

2.5. Statistical analysis

A total of 8 wounds per dressing group per time point were assessed, and all data were combined. A 1‐way analysis of variance was performed using SPSS Statistics Version 22 (IBM, New York). Differences between dressing groups were considered statistically significant when the P‐value was <.05.

3. RESULTS

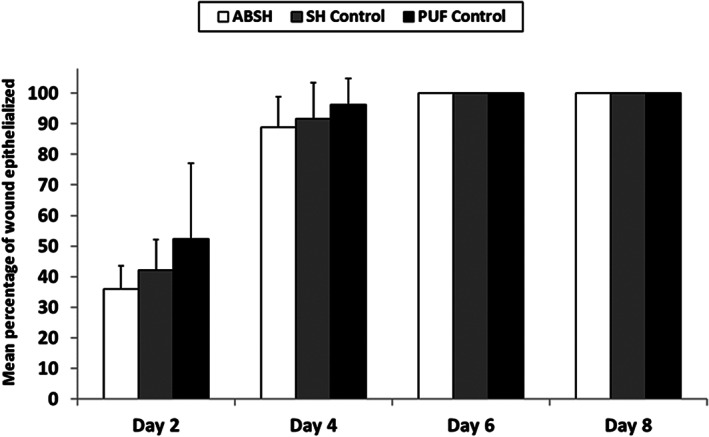

On days 2 and 4, no statistically significant differences were observed for the rate of re‐epithelialisation between dressing groups (Figure 1). All wounds in all dressing groups were completely reepithelialised by day 6. Overall, epithelial thickness was similar between groups, except for day 6, when epithelial thickness was greater in the SH control group (100.5 μm) compared with the other 2 groups (88.8 μm for ABSH and 84.9 μm for the PUF control group).

Figure 1.

The percentage of wound epithelialised during application of an anti‐biofilm silver Hydrofiber dressing, a silver Hydrofiber dressing control, or polyurethane film control at 2, 4, 6, and 8 days after wounding. Percentage calculated as a mean of 8 samples; error bars represent standard deviations. Abbreviations: ABSH, anti‐biofilm silver Hydrofiber; SH, silver Hydrofiber; PUF, polyurethane film

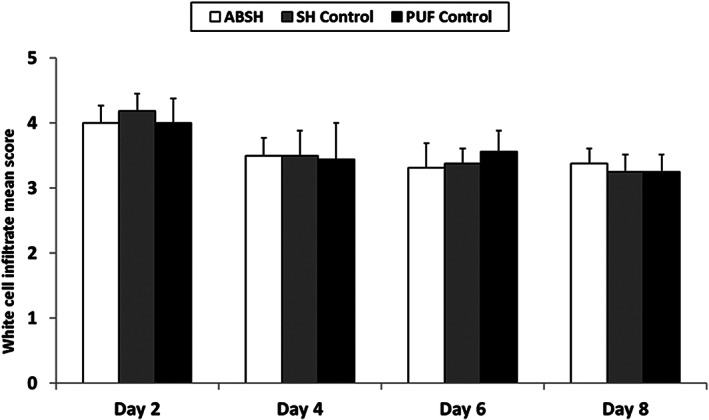

There were no statistically significant differences observed for white cell infiltration in wounds between the test dressing group and the control groups (Figure 2). Inflammatory infiltration of specific cell types into wounds dressed with each test dressing is detailed in Table 2. On day 2, mean scores for infiltration of polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMN) cells and lymphocytes were slightly higher in wounds dressed with ABSH compared with the PUF control group (P < .05); however no statistically significant differences between these groups were observed on days 4, 6, and 8. No significant differences in mean scores for infiltration of PMN cells and lymphocytes were observed between the ABSH group and the SH control group on days 2, 4, and 6; however, slightly more PMN cells and lymphocytes were seen in wounds dressed with ABSH compared with SH control at day 8 (P < .05). Macrophages were seen in wounds as early as day 2 in all 3 dressing groups. There were no statistically significant differences in mean infiltration scores for macrophages in wounds dressed with ABSH dressing compared with the SH control dressing on any study day. The mean score for macrophage infiltration in the ABSH and the SH control groups increased at days 4, 6 and 8 relative to day 2 and were generally greater than observed in the PUF control group (Table 2). A similar pattern was observed for giant cells (Table 2). No mast cells were observed in wounds for any of the groups.

Figure 2.

White cell infiltrate mean scores during application of an anti‐biofilm silver Hydrofiber dressing, silver Hydrofiber dressing control, or polyurethane film control at 2, 4, 6, and 8 days after wounding. Error bars represent standard deviations; n = 8. Abbreviations: ABSH, anti‐biofilm silver Hydrofiber; PUF, polyurethane film; SH, silver Hydrofiber

Table 2.

Mean scores ± standard deviation for infiltration of specific inflammatory cell types during application of an anti‐biofilm silver Hydrofiber dressing, silver Hydrofiber control dressing, or polyurethane film control at 2, 4, 6, and 8 days after wounding

| Inflammatory | Study | Dressing application | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell type | Day | ABSH | SH control | PUF control |

| PMN | 2 | 3.5 ± 0.0* | 3.5 ± 0.0 | 3.3 ± 0.3 |

| 4 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | |

| 6 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.4 | |

| 8 | 1.5 ± 0.5** | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 1.1 ± 0.4 | |

| Lymphocytes | 2 | 3.5 ± 0.0* | 3.5 ± 0.0 | 3.3 ± 0.3 |

| 4 | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 3.0 ± 0.0 | 2.8 ± 0.5 | |

| 6 | 2.8 ± 0.3 | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 2.7 ± 0.4 | |

| 8 | 2.3 ± 0.3** | 2.0 ± 0.0 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | |

| Macrophages | 2 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 1.0 ± 0.0 |

| 4 | 1.9 ± 0.4* | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | |

| 6 | 1.6 ± 0.5* | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | |

| 8 | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 1.4 ± 0.5 | 1.0 ± 0.0 | |

| Giant cells | 2 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.3 ± 0.5 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| 4 | 1.8 ± 0.5* | 1.7 ± 0.7 | 0.1 ± 0.2 | |

| 6 | 1.5 ± 0.8* | 1.8 ± 0.8 | 0.6 ± 0.5 | |

| 8 | 1.1 ± 0.6* | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 0.3 ± 0.5 | |

| Mast cells | 2 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| 4 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | |

| 6 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | |

| 8 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | |

ABSH, anti‐biofilm silver Hydrofiber; PMN, polymorphonuclear leukocytes; PUF, polyurethane film; SH, silver Hydrofiber.

P < .05 compared with PUF control.

P < .05 compared with SH control; n = 8.

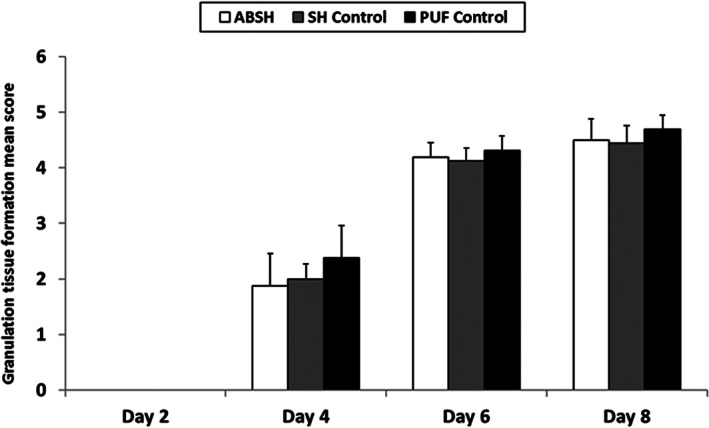

Overall, angiogenesis scores were similar between groups, ranging from 2.2 to 2.5 on day 4, 3.1 to 3.1 on day 6 and 3.0 to 3.2 on day 8 (no angiogenesis was observed on Day 2). No obvious granulation tissue formation was observed on day 2 with any of the dressings, and no significant differences were observed between groups on days 4, 6 and 8 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

New granulation tissue formation mean scores during application of an anti‐biofilm silver Hydrofiber dressing, silver Hydrofiber dressing control, or polyurethane film control at 2, 4, 6, and 8 days after wounding. Error bars represent standard deviations; n = 8. ABSH, anti‐biofilm silver Hydrofiber; PUF, polyurethane film; SH, silver Hydrofiber

There were no signs of erythema (redness) or oedema (swelling) observed in any wound in any group throughout the study duration. There were no histological signs of necrosis, fibrosis, or fatty tissue infiltration present in any of the wounds.

4. DISCUSSION

In this in‐vivo porcine study, no notable interference with normal wound‐healing processes was observed for any of the dressings investigated. No statistical differences were observed in the rate of reepithelialisation, white blood cell infiltration, angiogenesis, or granulation tissue formation following application of ABSH dressing compared with control dressings. Overall, epithelial thickness was similar between dressing groups. There was no oedema, erythema, or signs of tissue damage observed in any of the dressing groups.

The percentage of reepithelialisation represents the percentage of the wound area covered by the newly formed epidermis with 1 or more layers of keratinocytes, and is a good index for the speed of keratinocyte migration and the first step of reepithelialisation. White cell infiltration is a marker of the inflammation reaction that may be because of the normal process of wound repair or in response to microbial infection or a tissue reaction to foreign materials in the wound. Angiogenesis marks the degree of new microvascular blood vessel formation, which is characterised by newly formed capillary blood vessels with proliferating endothelial cells sprouting from adjacent existing blood vessels. The dermal reconstitution begins in about 3 to 4 days of injury with the hallmark of granulation tissue formation, which includes angiogenesis and the accumulation of fibroblasts and collagen extracellular matrices. The granulation tissue formation measures the percentage of wound bed filled with newly formed granulation tissue. Based on the findings of this study, the ABSH dressing does not appear to interfere with wound‐healing processes.

A semi‐quantitative analysis of various inflammatory cell types did demonstrate higher levels of PMN cells, lymphocytes, macrophages and giant cells following application of ABSH and the SH control dressing relative to the PUF control dressing. An initial increase in the inflammatory response observed for the 2 silver‐containing Hydrofiber dressings may reflect a higher activity of cells involved in natural debridement and removal of bacteria. Macrophages are large white cells derived from blood monocytes that ingest foreign particles and microorganisms by phagocytosis. Multiple macrophages can fuse together becoming giant cells with multiple nuclei and are very commonly observed when dressings and other medical devices are placed on a wound.12, 13, 14

The authors note that there are limitations of extrapolating pre‐clinical data to the clinical setting, especially as patients have different wound aetiologies, sizes, depths, and other variables. Ideally, testing of these dressings on the wound‐healing process sould be conducted on humans; however, it would not be practical to perform frequent biopsies to enable the histological assessment of the wound‐healing process. Furthermore, ethical considerations may not permit the inclusion of controls (untreated wounds), thereby limiting evaluation of the findings. A porcine model was therefore selected because pig skin is anatomically and physically more similar to human skin than smaller mammals.15 Furthermore, results from porcine models correlate more closely with clinical trial data than observed for other animal models.15 The porcine wound model used is well established and has been used for over 32 years to evaluate the effects of a variety of agents on wound healing.16, 17, 18, 19

Many antimicrobial agents have been shown to reduce the bacterial load in wounds and hence play an important role in wound management strategies.19, 20, 21, 22 However, there is some evidence to suggest that topical antimicrobial agents may also be cytotoxic to host cells.23, 24, 25 in vitro studies have raised concerns that some silver dressings can have detrimental effects on cells involved in the healing process and cause delays in reepithelialisation.26, 27 The current in‐vivo study did not find any delay to reepithelialisation following application of the ABSH dressing, and there were no other observations to suggest that this dressing interferes with wound‐healing processes. It should be noted that this study was conducted using non‐contaminated acute wounds (without biofilm) as the aim was to evaluate any interferences in normal wound healing processes that might be associated with the ABSH dressings rather than to assess the potential of the ABSH dressings to combat wound biofilm and assist healing. The ABSH dressing is designed and reported for use in patients with non‐healing wounds that may be compromised by biofilm, so it was not anticipated that the ABSH dressing would contribute to improved wound‐healing outcomes relative to the control dressings in this acute wound model.

The observations from this in‐vivo porcine model are consistent with those of clinical studies, which also did not identify any safety concerns associated with ABSH dressings.8, 9, 10 Furthermore, these clinical studies have demonstrated that ABSH dressings can reduce wound size, improve wound status, and improve skin health in previously non‐improving chronic wounds. In a multi‐centre clinical study conducted in the UK and Poland including 42 patients with venous leg ulcers, 76% of ulcers showed improvements in ulcer condition following application of an ABSH dressing.8 In a study of 111 patients in the UK and Ireland with challenging wounds present for a median of 12 months, of which over half were suspected to contain biofilm, 78% of wounds improved or healed and 70% had improved skin health following the introduction of an ABSH dressing.10

5. CONCLUSIONS

Together with published clinical studies, the findings from the current in‐vivo study indicate that ABSH dressings do not interfere with wound‐healing processes and provide further evidence to support the safety of this dressing in wound management.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge that this study was funded by ConvaTec Ltd. Philip Bowler is an Employee at ConvaTec Ltd. Editorial assistance was provided by Lorraine Ralph at ConvaTec Ltd.

Davis SC, Li J, Gil J, et al. The wound‐healing effects of a next‐generation anti‐biofilm silver Hydrofiber wound dressing on deep partial‐thickness wounds using a porcine model. Int Wound J. 2018;15:834–839. 10.1111/iwj.12935

Funding information ConvaTec Ltd

REFERENCES

- 1. Leaper D, Assadian O, Edmiston CE. Approach to chronic wound infections. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173(2):351‐358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Metcalf DG, Bowler PG. Biofilm delays wound healing: a review of the evidence. Burns Trauma. 2013;1(1):5‐12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wolcott R, Sanford N, Gabrilska R, Oates JL, Wilkinson JE, Rumbaugh KP. Microbiota is a primary cause of pathogenesis of chronic wounds. J Wound Care. 2016;25(suppl 10):S33‐S43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Metcalf D, Bowler P, Parsons D. Wound biofilm and therapeutic strategies. In: Dhanasekaran D, Thajuddin N, eds. Microbial Biofilms – Importance and Applications. Tiruchirappalli, India: IN TECH; 2016:271‐298. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bowler PG, Parsons D. Combatting wound biofilm and recalcitrance with a novel anti‐biofilm Hydrofiber® wound dressing. Wound Med. 2016;14:6‐11. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Parsons D, Meredith K, Rowlands VJ, Short D, Metcalf DG, Bowler PG. Enhanced performance and mode of action of a novel Antibiofilm Hydrofiber® wound dressing. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:1‐14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Seth AK, Zhong A, Nguyen KT, et al. Impact of a novel, antimicrobial dressing on in vivo, Pseudomonas aeruginosa wound biofilm: quantitative comparative analysis using a rabbit ear model. Wound Repair Regen. 2014;22(6):712‐719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Harding KG, Szczepkowski M, Mikosiński J, et al. Safety and performance evaluation of a next‐generation antimicrobial dressing in patients with chronic venous leg ulcers. Int Wound J. 2016;13(4):442‐448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Metcalf D, Parsons D, Bowler P. A next‐generation antimicrobial wound dressing: a real‐life clinical evaluation in the UK and Ireland. J Wound Care. 2016;25(3):132‐138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Metcalf DG, Parsons D, Bowler PG. Clinical safety and effectiveness evaluation of a new antimicrobial wound dressing designed to manage exudate, infection and biofilm. Int Wound J. 2017;14(1):203‐213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li J, Zhang YP, Zarei M, et al. A topical aqueous oxygen emulsion stimulates granulation tissue formation in a porcine second‐degree burn wound. Burns. 2015;41(5):1049‐1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Agren MS, Mertz PM, Franzen L. A comparative study of three occlusive dressings in the treatment of full‐thickness wounds in pigs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36(1):53‐58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Barlev D, Spicknall KE. Histologic findings following use of hydrophilic polymer with potassium ferrate for hemostasis. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41(12):959‐962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wolf MT, Dearth CL, Ranallo CA, et al. Macrophage polarization in response to ECM coated polypropylene mesh. Biomaterials. 2014;35(25):6838‐6849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sullivan TP, Eaglstein WH, Davis SC, Mertz P. The pig as a model for human wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2001;9(2):66‐76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Davis SC, Li J, Gil J, et al. A closer examination of atraumatic dressings for optimal healing. Int Wound J. 2015;12(5):510‐516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Davis SC, Mertz PM, Cazzaniga AL, Serralta V, Orr R, Eaglstein WH. The use of new antimicrobial gauze dressings: effects on the rate of epithelialization of partial‐thickness wounds. Wounds. 2002;14(7):252‐256. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Harding AC, Gil J, Valdes J, Solis M, Davis SC. Efficacy of a bio‐electric dressing in healing deep, partial‐thickness wounds using a porcine model. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2012;58(9):50‐55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mertz PM, Davis SC, Brewer LD, Franzén L. Can antimicrobials be effective without impairing wound healing? The evaluation of a Cadexomer iodine ointment. Wounds. 1994;6(6):184‐193. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lansdown AB. Silver. I: its antibacterial properties and mechanism of action. J Wound Care. 2002;11(4):125‐130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dryden MS, Cooke J, Salib RJ, et al. Reactive oxygen: a novel antimicrobial mechanism for targeting biofilm‐associated infection. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2017;8:186‐191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Siah CJ, Yatim J. Efficacy of a total occlusive ionic silver‐containing dressing combination in decreasing risk of surgical site infection: an RCT. J Wound Care. 2011;20(12):561‐568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brennan SS, Leaper DJ. The effect of antiseptics on the healing wound: a study using the rabbit ear chamber. Br J Surg. 1985;72(10):780‐782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lineaweaver W, McMorris S, Soucy D, Howard R. Cellular and bacterial toxicities of topical antimicrobials. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;75(3):394‐396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Duc Q, Breetveld M, Middelkoop E, Scheper RJ, Ulrich MM, Gibbs S. A cytotoxic analysis of antiseptic medication on skin substitutes and autograft. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157(1):33‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fredriksson C, Kratz G, Huss F. Accumulation of silver and delayed re‐epithelialization in normal human skin: an ex‐vivo study of different silver dressings. Wounds. 2009;21(5):116‐123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zou SB, Yoon WY, Han SK, Jeong SH, Cui ZJ, Kim WK. Cytotoxicity of silver dressings on diabetic fibroblasts. Int Wound J. 2013;10(3):306‐312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]