Abstract

Sanitation improvements have had limited effectiveness in reducing the spread of fecal pathogens into the environment. We conducted environmental measurements within a randomized controlled trial in Bangladesh that implemented individual and combined water treatment, sanitation, handwashing (WSH) and nutrition interventions (WASH Benefits, NCT01590095). Following approximately 4 months of intervention, we enrolled households in the trial’s control, sanitation and combined WSH arms to assess whether sanitation improvements, alone and coupled with water treatment and handwashing, reduce fecal contamination in the domestic environment. We quantified fecal indicator bacteria in samples of drinking and ambient waters, child hands, food given to young children, courtyard soil and flies. In the WSH arm, Escherichia coli prevalence in stored drinking water was reduced by 62% (prevalence ratio = 0.38 (0.32, 0.44)) and E. coli concentration by 1-log (Δlog10 = −0.88 (−1.01, −0.75)). The interventions did not reduce E. coli along other sampled pathways. Ambient contamination remained high among intervention households. Potential reasons include noncommunity-level sanitation coverage, child open defecation, animal fecal sources, or naturalized E. coli in the environment. Future studies should explore potential threshold effects of different levels of community sanitation coverage on environmental contamination.

Background

Diarrheal disease, intestinal parasites, and subclinical enteric infections are transmitted through environmentally mediated pathways,1,2 which can be interrupted by water, sanitation and hygiene interventions. Sanitation as a “primary barrier” isolates fecal matter from the environment to prevent the spread of fecal pathogens and reduce fly breeding sites. Water treatment and handwashing as “secondary barriers” reduce the transmission of pathogens from the environment to new hosts while handwashing also reduces person-to-person transmission.3 Water treatment and handwashing have been shown to lower fecal contamination of drinking water and hands, respectively, and reduce reported diarrhea.4−7 In contrast, sanitation interventions have shown mixed health impact and generally no effect on domestic environmental contamination.8−11 Larger impact can potentially be achieved by augmenting sanitation improvements with water treatment and handwashing to synergistically interrupt multiple disease transmission pathways.

Few studies have assessed how water, sanitation, and hygiene interventions affect disease transmission through pathways other than the conventionally studied routes of drinking water and hands.11 In low-income countries, fecal contamination is pervasive on surfaces and objects in the domestic environment12 and ambient waters used for bathing and washing dishes.13 Flies carry fecal pathogens14,15 and can transmit these to stored food;16 fly control programs have successfully reduced diarrheal diseases.17,18 Soil is increasingly recognized as a reservoir for fecal organisms and has been linked to fecal contamination of drinking water, hands, and food;19 ingestion of soil by children has been associated with environmental enteric dysfunction and stunting.20 Identifying which of these transmission pathways are blocked by different interventions elucidates the mechanisms through which water, sanitation and hygiene programs improve health and allows broader understanding of how findings might generalize to other settings. Without measuring fecal contamination in different environmental matrices as a causal intermediate, trials are limited to a “black box” understanding, where underlying mechanisms of interventions are unknown and investigators can only speculate about reasons for intervention success or failure.

We collected environmental measurements within a randomized controlled trial in rural Bangladesh (WASH Benefits, ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01590095) to assess how sanitation improvements, alone and combined with water and handwashing interventions, affect fecal contamination along a comprehensive set of environmentally mediated pathways.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

The WASH Benefits trial was conducted in four districts (Gazipur, Kishoreganj, Mymensingh, Tangail) in central rural Bangladesh. Groundwater in parts of Bangladesh contains high levels of naturally occurring arsenic and iron.21 Study districts were chosen to have low concentrations of these groundwater chemicals because the trial’s chlorine-based microbiological water quality intervention was not designed to remove arsenic and also because the chlorine demand exerted by iron limits the effectiveness of chlorination.22 The areas were also chosen to not have any major water, sanitation and hygiene programs that would interfere with study activities.

The parent WASH Benefits trial enrolled pregnant women with the objective of following their birth cohort (referred to as “index children” hereinafter). Field staff screened the study area for eligible women and recorded their global positioning system (GPS) coordinates. Neighboring groups of eight eligible women were grouped into clusters based on their coordinates. Cluster dimensions were chosen such that one field worker could visit all cluster participants in 1 day. A minimum 1 km buffer was enforced between clusters to minimize spillovers of intervention effects and/or intervention messages between study arms. Every eight adjacent clusters formed a geographic block. An off-site investigator (BFA) block-randomized clusters into study arms using a random number generator, providing geographically pair-matched randomization. The trial arms included individual and combined water, sanitation, handwashing and nutrition interventions and a double-sized control arm which received no intervention. Details of the trial design have been reported.23 The primary outcomes of WASH Benefits were child diarrhea and growth, and additional trial outcomes included protozoa and soil-transmitted helminth infections; these have been reported separately.24−26 Measures of environmental contamination were prespecified intermediate outcomes.23

We conducted an environmental assessment among the control, sanitation and combined water, sanitation and handwashing (WSH) arms of the trial (see Supporting Information (SI) Text S1 and Figure S1 for details of all environmental assessments nested within WASH Benefits). The sanitation intervention included upgrades to concrete-lined double-pit latrines, and provision of child potties and scoops for the disposal of human and animal feces. Households in Bangladesh are clustered in multifamily compounds. All households in the compound where the enrolled women and their newborns lived received latrine upgrades, potties and scoops in order to reduce fecal contamination in the shared compound environment. Enrolled compounds made up <10% of a given geographical area because of the eligibility criterion of having a pregnant woman. As such, the trial did not provide community-wide sanitation coverage. The water treatment and handwashing interventions targeted the household where the enrolled women lived and included (1) point-of-use water treatment with sodium dichloroisocyanurate (NaDCC, Aquatabs) (Medentech, Wexford, Ireland) and safe storage in a narrow-mouth, lidded container with spigot and (2) provision of handwashing stations in the kitchen and latrine areas with a water reservoir, a bottle containing a soapy water mixture and a basin to catch the rinsewater.

Community health promoters hired from among local women and trained specifically for the study visited intervention households on average six times per month throughout the trial to provide intervention products for free, replenish supplies as needed throughout the study period and encourage user adherence. Intervention adherence, measured objectively with unannounced spot-check and structured observations as an independent investigation from the study activities reported here, was high throughout the study.27 Households in the intervention arms retained the intervention hardware (e.g., latrines, potties, safe storage container) but the supply of consumables (chlorine tablets, soapy water solution) was discontinued after the end of the trial. Control households did not receive any interventions or health promoter visits during or after the trial. No compensation was offered for participation. Further details of the intervention packages, health promoter visits and user adherence are reported elsewhere.27−29

Procedures

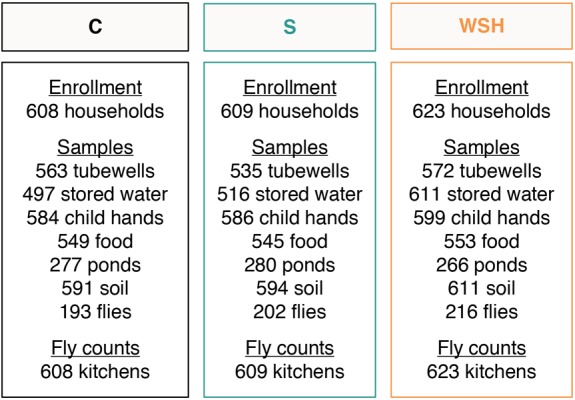

We conducted the environmental assessment after roughly 4 months of intervention. In the three study arms selected for the environmental assessment, field staff from the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b) trained specifically for this study conducted household visits to assess indicators of household water, sanitation and hygiene practices through spot-check observations and a structured questionnaire. They collected samples of source and stored drinking water, ambient water from ponds adjacent to enrolled households and used for bathing and domestic chores, hand rinses from index children, food given to young children, courtyard soil and flies captured near the kitchen to quantify fecal indicator bacteria in the domestic environment (Figure 1). They also enumerated and speciated synanthropic flies in the kitchen area.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of participant enrollment and environmental sampling scheme. C refers to the control arm, S to the individual sanitation arm and WSH to the combined water, sanitation and handwashing arm.

Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Indicators

Field workers observed drinking water storage conditions and recorded user-reported water treatment practices. In households reporting chlorination, they measured the free chlorine residual in stored drinking water with a digital colorimeter (Hach Pocket Colorimeter II). They inspected the compounds for latrine access, presence of an improved latrine as defined by the Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation,30 and latrine functionality and condition. They recorded caregiver-reported child defecation and child feces handling practices. Field staff also examined caregiver and index child hands (fingernails, fingerpads, palms) for visible dirt as a proxy for handwashing behavior31 and checked for the presence of water and soap within six steps of the latrine and kitchen. Finally, they observed food storage conditions such as whether the storage container was covered or elevated to assess if these were indirectly affected by the interventions even though the intervention packages did not entail any materials and behavioral messages for hygienic storage of food.

Sample Collection

Samples were collected using sterile Whirlpak bags (Nasco Modesto, Salida, CA). Clean gloves were worn while collecting pond, hand rinse, food and soil samples. To sample tubewells, field workers removed fabric or other materials from the tubewell mouth and flushed the well by pumping five times before collecting 250 mL of water. To collect stored water, field workers asked the respondent to provide a glass of drinking water from the primary storage container in the same manner they would give it to their children and pour approximately 150 mL into the Whirlpak. If the respondent reported using chlorine, sodium thiosulfate was used to neutralize residual chlorine. Ponds were sampled by dipping a Whirlpak into the pond and collecting 250 mL of water from the pond surface in the area where the household reported most commonly accessing the pond. Hand rinse samples were collected from the index child (aged 1–14 months), and if not available, from the next youngest child in the household. To sample child hands, field workers asked the respondent to place the child’s left-hand into a Whirlpak prefilled with 250 mL of distilled water. The hand was massaged from outside the bag for 15 s and shaken for 15 s. The procedure was repeated with the right-hand in the same bag, and the rinsewater was preserved in the Whirlpak. To sample food given to young children, field workers identified stored food prepared to be served to children <5 years and asked the respondent to provide a small amount in the same manner they would serve it to their children. They prioritized sampling rice if available. Field staff scooped the food from the dish it was provided in into a 50 mL sterile tube using a sterile spoon. To sample soil, the respondent was asked to identify the outdoor area where young children had most recently spent time. Field workers marked a 30 × 30 cm area using a stencil sterilized with ethanol between each household and scraped the top layer of soil within the stencil into a Whirlpak using a sterile scoop; the area was scraped once vertically and once horizontally to collect approximately 50 g of soil. To enumerate and sample flies, field workers identified a suitable location in the kitchen area (away from the stove smoke, under a roof or protected from rain) and horizontally hung three 1.5-foot strips of nonbaited sticky fly tape. They returned to the household 3–6 h later to count the captured synanthropic flies and speciate them according to a visual identification chart.32 They removed one fly from the center of the strip with the most flies using sterile tweezers and placed it into a Whirlpak. Samples were transported to the icddr,b field laboratory on ice at 2–8 °C.

Sample Processing

Samples were analyzed in 100 mL aliquots using IDEXX Quantitray (IDEXX Laboratories, Maine, USA) within 12 h of collection. Tubewell and stored water was analyzed undiluted. Pond samples were diluted 1:100 (1 mL of sample +99 mL of distilled water) and hand rinses 1:2 (50 mL of sample +50 mL of distilled water). Food and soil were homogenized with distilled water in a sterile blending bag (Interscience, Saint Nom, France) using a laboratory-scale food processer (Interscience, Saint Nom, France). A 10 g food aliquot was homogenized with 100 mL water; 10 mL of homogenate was then mixed with 90 mL of distilled water. A 20 g soil aliquot was homogenized with 200 mL water; 1 mL of homogenate was mixed with 99 mL of distilled water, serially repeated twice, to generate a final 100 mL aliquot. Additional 5 g aliquots of food and soil were oven-dried overnight to determine moisture content. Flies were homogenized with a pestle from outside the Whirlpak and mixed with 100 mL of distilled water; 1 mL of slurry was then mixed with 99 mL of distilled water. Colilert-18 media was added to samples, followed by incubation at 44.5 °C for 18 h to enumerate the most probable number (MPN) of Escherichia coli and fecal/thermotolerant coliforms33 (per 100 mL for water samples, per 2 hands for child hands, per 1 dry gram for food and soil and per 1 fly for flies). MPN values were derived from the number of yellow and/or fluorescent wells on the trays using the IDEXX Quantitray-2000 MPN table. Trays exceeding the upper detection limit of 2419 MPN were classified as too numerous to count (TNTC); the Quantitray-2000 system with this high detection limit was chosen to capture a range of contamination levels (see SI Table S1 for detection limits for each sample type).

Quality Control

One laboratory control per analyst per day and 5% replicates (repeat aliquots from same Whirlpak for every 20th sample) were processed. Field workers collected 10% field blanks (one blank for every 10 samples) by asking respondents to pour distilled water from a sterile bottle into a Whirlpak as if collecting a stored water sample and by opening and massaging a prefilled Whirlpak as if sampling a hand.

Ethics

Participants provided written informed consent in the local language (Bengali). The study protocol was approved by human subjects committees at the icddr,b (PR-11063), University of California, Berkeley (2011–09–3652), and Stanford University (25863).

Statistical Methods

Our prespecified analysis plan is registered and publicly available at Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/6u7cn/).

Sample Size

The environmental assessment targeted all households enrolled in one of the double-sized control arms, sanitation arm and WSH arm of WASH Benefits for a total of 2160 households (720/arm). We obtained measures of contamination and intraclass correlation coefficients from the literature and unpublished pilot data (see analysis plan). We assumed the interventions would decrease but not increase contamination4,6 and therefore used a one-sided α of 0.05. Our sample size had 80% power to detect a 25% relative reduction in E. coli prevalence in tubewells and 0.20 log10 reduction in E. coli counts in stored water, in soil and on hands, compared to controls.

Parameters of Interest

Our outcomes were (1) prevalence and concentration of E. coli and fecal coliforms, (2) prevalence and number of flies near the kitchen, and (3) prevalence of caregiver and child hands with visible dirt. Our parameters were prevalence ratios (PR) and differences (PD) for the binary measures, log10 reductions for E. coli and fecal coliform concentrations, and fly count ratios for the number of flies. We substituted bacterial counts with half the lower detection limit for nondetects and with 2420 MPN for TNTC samples.34

Estimation Strategy

We compared both intervention arms to controls and the combined WSH arm to the single sanitation arm. Analyses were intention-to-treat; this preserves the randomization and is appropriate given the trial’s high user adherence to interventions.27 Randomization balanced covariates across arms.24 Therefore, we relied on unadjusted estimates in our analysis. We estimated unadjusted parameters using generalized linear models with robust standard errors, and a log link for PRs, linear link for PDs and log10 reductions, and log link allowing for overdispersion (negative binomial regression) for fly count ratios. Secondary analyses adjusted for prespecified covariates using doubly robust targeted maximum likelihood estimation (TMLE) incorporating an ensemble machine learning method called Super Learner.35,36 We included an interaction term for wet vs dry season to assess effect modification by weather conditions; Bangladesh has a pronounced monsoon season from June through October which delivers >80% of the annual rainfall,37 and the wet conditions are typically associated with higher levels of environmental contamination.19

Results and Discussion

Enrollment

Of 2098 households enrolled in the control, sanitation and combined WSH arms of WASH Benefits, we enrolled 1840 (88%) in the environmental assessment between July 2013 and March 2014. Reasons for households not being enrolled included no live birth or index child death (n = 158, 7.5%), absence or relocation (n = 72, 3.4%), refusal (n = 21, 1.0%) and no intervention hardware yet having been delivered (n = 7, 0.3%). Covariates were balanced between arms among enrolled households (SI Table S2).

Time Since Intervention Delivery

Political instability in Bangladesh during the study delayed latrine construction in some areas. As a result, there was a short time window (1–4 weeks) between latrine construction completion and our environmental assessment in 20% of enrolled households. Of the rest, 55% of households received their latrine construction 1–6 months before and 22% 6–12 months before our visit. On average, the time window between latrine construction and our environmental assessment was 4 months. All other hardware distribution (potties and sani-scoops, handwashing stations, water treatment tablets, safe storage containers) had been completed for the entire study population with the exception of seven households at the time of our visit, and behavior promotion was ongoing. Among households in the combined WSH and sanitation arms, 94% had received a promotion visit within the last week, and 98% had received a visit within the last 2 weeks.

Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene Indicators

Drinking Water

Water treatment and safe storage practices were substantially improved in the WSH arm (Table 1), with 95% of drinking water storage containers fully covered (vs <30% in control and sanitation arms) and 92% of respondents reporting treating their water (vs <2% in control and sanitation arms) at the time of our household visit. Reported water treatment in the WSH arm was exclusively by Aquatabs, and 78% of households reporting using Aquatabs had detectable (>0.1 mg/L) free chlorine residual in their stored drinking water.

Table 1. Indicators of Water Treatment, Sanitation and Hand and Food Hygiene.

| percent of households | control | sanitation | WSHa |

|---|---|---|---|

| water storage container covered | 28.4 | 29.0 | 95.3 |

| reported treating drinking water | 1.8 | 1.9 | 92.0 |

| detectable (>0.1 mg/L) chlorine residualb | 77.7 | ||

| on-site latrine present in compound | 97.2 | 100.0 | 99.8 |

| primary latrine is improved latrine | 67.4 | 96.0 | 98.5 |

| primary latrine has functional water seal | 36.1 | 93.1 | 94.4 |

| primary latrine drains into environment | 22.2 | 3.6 | 1.8 |

| young children reported to defecate in potty/latrine | 7.9 | 17.5 | 17.8 |

| child feces disposed of in latrine | 9.7 | 29.8 | 30.9 |

| reported using scoopc to handle child feces | 7.9 | 8.5 | 7.6 |

| reported using scoopc to handle animal feces | 34.7 | 64.6 | 63.8 |

| water and soap available <6 steps from latrine | 7.5 | 7.4 | 45.3 |

| water and soap available <6 steps from kitchen | 4.4 | 2.8 | 69.6 |

| food storage container covered | 85.1 | 82.7 | 85.8 |

| food stored at safe location (elevated/inside cabinet) | 72.0 | 69.8 | 74.4 |

| ≥1 fly caught in kitchen | 31.9 | 34.0 | 35.3 |

| % of houseflies among flies caught | 85.2 | 96.5 | 88.7 |

WSH: Water, sanitation and handwashing.

Among households reporting having used chlorine to treat their stored drinking water.

Sani-scoop provided by WASH Benefits or other feces removal tool (e.g., garden hoe).

Sanitation

Almost all control households had access to some form of on-site sanitation facility (Table 1). Households in the sanitation and WSH arms had substantially increased access to improved latrines with hygienic isolation of feces, with >90% of latrines having a functional water seal (vs 36% among controls) and <5% draining into the environment (vs 22% among controls). Child feces management remained poor; in the sanitation and WSH arms, < 20% of young children were reported to defecate in a latrine or potty, approximately 30% of respondents reported disposing of child feces in a latrine and <10% reported using the sani-scoop to handle child feces, while approximately 65% reported using it to handle animal feces (Table 1).

Handwashing

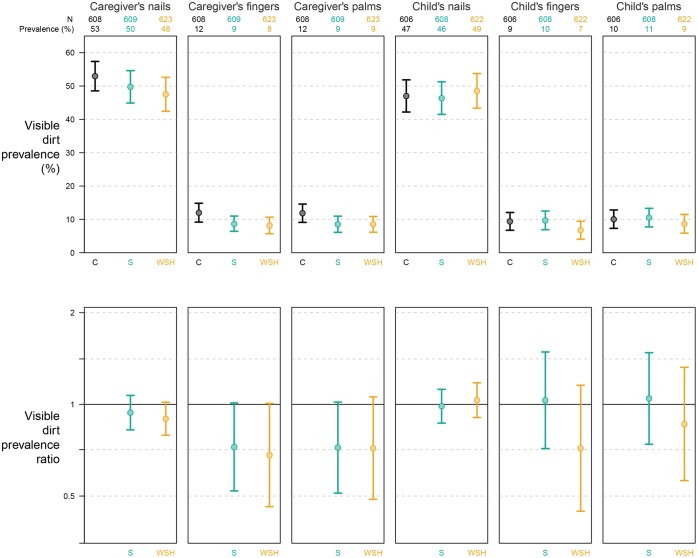

Access to water and soap for handwashing near the latrine and kitchen was substantially higher in the WSH arm compared to the control and sanitation arms (Table 1). Among caregivers and children in the control arm, approximately 50% of fingernails and 10% of fingerpads and palms had visible dirt (Figure 2). Caregivers in the WSH and sanitation arms had borderline reductions in the prevalence of dirt on fingerpads/palms but not nails compared to controls; the prevalence of dirt on child hands was similar across arms (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of caregivers and children with visible dirt on hands. C refers to the control arm, S to the individual sanitation arm and WSH to the combined water, sanitation and handwashing arm.

Food Hygiene

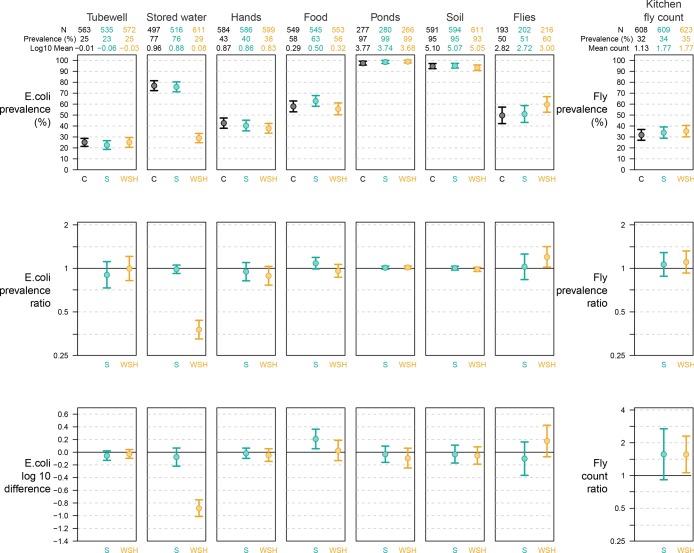

Food storage practices were comparable across arms, with the majority of the containers covered and stored at a safe location elevated from the ground or inside a cabinet (Table 1). Among controls, at least one fly was captured in 32% of kitchens and the mean number of flies was 1.13 (range: 1–68). The predominant fly species was the common housefly (Musca domestica) in all arms. There was no reduction in the prevalence and number of flies in the sanitation or WSH arms compared to controls (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Prevalence and concentration of E. coli (in source and stored drinking water, child hand rinses, food given to young children, pond water, courtyard soil, flies) and prevalence and number of flies captured near kitchen after approximately 4 months of intervention. E. coli concentrations are reported in the log of the most probable number (MPN) per 100 mL for tubewell, stored water and pond samples, per two hands for child hand rinses, per dry gram for food and soil samples and per fly for fly samples. C refers to the control arm, S to the individual sanitation arm and WSH to the combined water, sanitation, and handwashing arm.

Fecal Contamination

Levels of Contamination

We analyzed a total of 9940 samples. Half (49%) of households had a pond and a third (32%) had a fly caught for analysis. Among controls, we detected E. coli in 25% of tubewells, 77% of stored water, 43% of child hands, 58% of children’s food, 97% of ponds, 95% of courtyard soil and 50% of flies (Figure 3). The ambient environment, such as ponds and soil, had extremely high contamination; geometric mean E. coli was >5000 MPN per 100 mL of pond water and >120 000 MPN per dry gram for soil.

Intervention Effects

There was no difference in the prevalence or concentration of E. coli for any sample type between the sanitation and control arms (Figure 3, SI Table S3). Comparing the WSH arm to controls, stored drinking water had a significant reduction in E. coli prevalence (prevalence = 29%, prevalence ratio [PR] = 0.38 (0.32, 0.44), p < 0.001) and approximately 1-log reduction in E. coli concentration (Δlog10 = −0.88 (−1.01, −0.75), p < 0.001); no other pathway in the WSH arm had reductions in E. coli (Figure 3, SI Table S3). Secondary analyses adjusting for confounders yielded similar results (SI Table S3). Subgroup analyses suggested larger reductions in E. coli in stored drinking water during the dry season; there were no other seasonal effects (SI Table S4). Fecal coliforms showed similar patterns (SI Table S5).

Quality Control

Across sample types, 41% of samples were nondetect and 5% exceeded upper detection limits. Intraclass correlation between samples processed in replicate was 86%. E. coli was detected in 1% of blanks, and the geometric mean E. coli count among positive blanks was 6 MPN. Repeating the analyses after removing the data from days with contaminated blanks did not change findings (SI Table S6).

Implications

The sanitation intervention, alone or combined with water treatment and handwashing, did not reduce fecal contamination of ambient and groundwater sources, child hands, food, flies and soil in the domestic environment. Chlorination and safe storage reduced E. coli in stored drinking water, consistent with prior evidence.4 Intervention households were subject to high levels of contamination in the ambient environment.

Our findings are consistent with previous sanitation trials that generally found no impact on environmental contamination.8−10 These prior studies entailed community-level programs with low to moderate adherence; 38–65% of households in intervention villages had indicators of improved sanitation vs 10–35% of controls.8−10 WASH Benefits Bangladesh implemented a compound-level intervention with upgrades to concrete-lined double-pit latrines for all households in enrolled compounds. In the sanitation arm, > 90% of respondents had an improved latrine with a functional water seal, and structured observations demonstrated high latrine use among adults.27 Low adherence is therefore unlikely to explain the lack of intervention effects from sanitation. However, structured observations can overestimate latrine use as an observer’s presence artificially enhances socially desirable practices.38 Also, children continued open defecation despite sanitation access and provision of child potties; fewer than 20% of children were reported to defecate in a latrine or potty. Child feces are often rinsed into ditches or bushes or left on the ground in rural Bangladeshi households;39 30% of our respondents reported disposing of child feces in a latrine and <10% reported using a scoop to handle child feces.

Additionally, trial participants made up <10% of compounds within the boundaries of study clusters because of the eligibility criterion of having a pregnant woman. Enrolled compounds were surrounded by nonstudy compounds whose sanitary conditions likely remained at baseline levels. In a separate assessment in our study area, we found evidence for spillover of environmental contamination between neighboring study and nonstudy compounds.40 Our compound-level interventions were thus possibly not sufficient to impact the broader environment without higher community-level coverage of improved sanitation. A growing body of evidence suggests that community-level sanitation coverage may be more important than individual household sanitation for preventing child diarrhea in rural settings.41,42 For example, in rural Mali, higher community-level sanitation coverage was more strongly associated with improved child growth and improved drinking water quality than individual household access to a toilet.43 Contamination from the community can enter the compound on shoes and soles of compound residents or through surface runoff and/or animal waste runoff. Bangladeshi families also use soil from outside the compound to coat walls and courtyards. Soil, in turn, can contaminate hands, stored water and food.19 Additionally, groundwater and ambient waters can receive subsurface infiltration from surrounding compounds. Studies in Bangladesh found that latrine density within 100 m of a well and within a pond’s catchment area is predictive of tubewell and pond water quality44,45 rather than the presence of a latrine within the compound.46 However, a recent study showed that infiltration from latrines is limited to a radius of a few meters47 such that contamination from surrounding compounds through subsurface transport is unlikely to affect groundwater quality. Nonetheless, wells can also receive surface contamination from the surrounding environment through unsealed or malfunctioning wellheads.48

Furthermore, almost all control households in our study population had some form of on-site sanitation, such that the trial presented an improvement in latrine quality and drainage as well as access to tools for child feces management but not basic latrine access. A setting with lower latrine coverage in the control group and a larger contrast in sanitation access between controls and intervention recipients may be better poised to detect an impact on environmental contamination.

It is also possible that the window between intervention initiation and our measurements (4 months on average) was not enough time for water, sanitation and hygiene practices to change or for environmental reservoirs to respond to any reductions in fecal input. While the water quality improvements indicate that water treatment practices had taken hold, sanitation behaviors might not have changed sufficiently to impact environmental contamination. Additionally, subsurface infiltration from new pit latrines is higher during the initial few months and diminishes afterward, potentially due to the formation of a layer (like the schmutzdecke on biosand filters) that attenuates contamination.47 Finally, while E. coli typically survives <20 days in soil,49 it can persist for extended durations in tropical soils.50 It is therefore possible that a longer follow-up period would capture more pronounced impact from sanitation improvements on environmental contamination.

Despite the lack of reductions in environmental contamination, sanitation arm participants experienced reductions in diarrhea24 and infections with protozoa25 and soil-transmitted helminths,26 suggesting reduced fecal-oral pathogen transmission in this arm not reflected by our E. coli measurements. One explanation is that the impact of the sanitation intervention on fecal-sourced E. coli in the environment may have been masked by “naturalized” E. coli since E. coli can be naturally present in tropical soils and waters.51 Naturalized E. coli are phenotypically identical to E. coli from fecal sources; the detection methods used in our study cannot distinguish between naturalized and fecal E. coli.52,53 The lack of E. coli reduction in soil, ponds, and groundwater could therefore be due to nonfecal E. coli in the environment. However, testing a subset of our soil samples with biochemical assays, phylogrouping and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detection of genes associated with enteric vs environmental origin showed no differences between E. coli isolates in soil vs in fecal samples collected from animals and humans in the study area.54

Another explanation is that fecal indicator bacteria cannot differentiate between animal vs human fecal sources.55 It is possible that the sanitation intervention reduced human fecal contamination but animal fecal contamination masked this effect. While two-thirds of participants in the sanitation and WSH arms reported using a scoop to dispose of animal feces, we observed animal feces in 90% of study compounds (vs human feces in <5%), and the presence of domestic animals was associated with increased E. coli in soil, drinking water and stored food.19 Testing a subset of 500 soil, stored water and hand rinse samples from study households for molecular fecal markers revealed prevalent ruminant and avian markers while human markers were rare,56 highlighting the role of animal fecal sources.

Our findings indicate high levels of ambient contamination not affected by sanitation improvements in this setting. This could be due to lack of community-level improved sanitation coverage, child open defecation, animal fecal sources, or naturalized E. coli. Studies measuring the impact of sanitation on contamination in the ambient environment should consider alternative indicators to differentiate between human and animal fecal sources. Studies should explore if there are threshold effects associated with different levels of sanitation coverage and different contrasts in pre- vs postintervention sanitation access on environmental contamination.

Acknowledgments

This research protocol was funded by the World Bank and by Global Development grant OPPGD759 from Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to University of California, Berkeley to International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b, grant number 741). icddr,b acknowledges with gratitude the commitment of Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and University of California, Berkeley to its research efforts. icddr,b is also grateful to the Governments of Bangladesh, Canada, Sweden and the UK for providing core/unrestricted support. We also offer our sincere gratitude to the study participants who participated in the trial and community health promoters (CHPs), field workers and supervisors who delivered the interventions.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.8b02988.

Text S1. Environmental assessments nested within WASH Benefits (Figure S1). Types of samples collected for environmental assessments approximately 4 months, one year and two years after the initiation of WASH Benefits interventions (Table S1). E. coli detection units and limits (Table S2). Enrollment characteristics by intervention group (Table S3). E. coli prevalence and concentration measured in control, sanitation and WSH arms after four months of intervention (Table S4). Subgroup analysis by dry vs wet season on E. coli prevalence (Table S5). Fecal coliform prevalence and concentration measured in control, sanitation and WSH arms after four months of intervention (Table S6). E. coli prevalence and concentration (after data from dates with contaminated blanks have been removed) (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Eisenberg J. N. S.; Trostle J.; Sorensen R. J. D.; Shields K. F. Toward a Systems Approach to Enteric Pathogen Transmission: From Individual Independence to Community Interdependence. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2012, 33, 239–257. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031811-124530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawata K. Water and Other Environmental Interventions--the Minimum Investment Concept. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1978, 31 (11), 2114–2123. 10.1093/ajcn/31.11.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis V.; Cairncross S.; Yonli R. Review: Domestic Hygiene and Diarrhoea – Pinpointing the Problem. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2000, 5 (1), 22–32. 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2000.00512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold B. F.; Colford J. M. Treating Water with Chlorine at Point-of-Use to Improve Water Quality and Reduce Child Diarrhea in Developing Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2007, 76 (2), 354–364. 10.4269/ajtmh.2007.76.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clasen T. F.; Alexander K. T.; Sinclair D.; Boisson S.; Peletz R.; Chang H. H.; Majorin F.; Cairncross S.. Interventions to Improve Water Quality for Preventing Diarrhoea. In Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luby S. P.; Agboatwalla M.; Raza A.; Sobel J.; Mintz E. D.; Baier K.; Hoekstra R. M.; Rahbar M. H.; Hassan R.; Qureshi S. M.; Gangarosa E. J. Microbiologic Effectiveness of Hand Washing with Soap in an Urban Squatter Settlement, Karachi, Pakistan. Epidemiol. Infect. 2001, 127 (2), 237–244. 10.1017/S0950268801005829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman M. C.; Stocks M. E.; Cumming O.; Jeandron A.; Higgins J. P. T.; Wolf J.; Prüss-Ustün A.; Bonjour S.; Hunter P. R.; Fewtrell L.; Curtis V. Systematic Review: Hygiene and Health: Systematic Review of Handwashing Practices Worldwide and Update of Health Effects. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2014, 19 (8), 906–916. 10.1111/tmi.12339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil S. R.; Arnold B. F.; Salvatore A. L.; Briceno B.; Ganguly S.; C J. M. Jr; Gertler P. J. The Effect of India’s Total Sanitation Campaign on Defecation Behaviors and Child Health in Rural Madhya Pradesh: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. PLOS Med. 2014, 11 (8), e1001709. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clasen T.; Boisson S.; Routray P.; Torondel B.; Bell M.; Cumming O.; Ensink J.; Freeman M.; Jenkins M.; Odagiri M.; Ray S.; Sinha A.; Suar M.; Schmidt W. P. Effectiveness of a Rural Sanitation Programme on Diarrhoea, Soil-Transmitted Helminth Infection, and Child Malnutrition in Odisha, India: A Cluster-Randomised Trial. Lancet Glob. Health 2014, 2 (11), e645–e653. 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70307-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering A. J.; Djebbari H.; Lopez C.; Coulibaly M.; Alzua M. L. Effect of a Community-Led Sanitation Intervention on Child Diarrhoea and Child Growth in Rural Mali: A Cluster-Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet Glob. Health 2015, 3 (11), e701–e711. 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00144-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sclar G. D.; Penakalapati G.; Amato H. K.; Garn J. V.; Alexander K.; Freeman M. C.; Boisson S.; Medlicott K. O.; Clasen T. Assessing the Impact of Sanitation on Indicators of Fecal Exposure along Principal Transmission Pathways: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2016, 219 (8), 709–723. 10.1016/j.ijheh.2016.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering A. J.; Julian T. R.; Marks S. J.; Mattioli M. C.; Boehm A. B.; Schwab K. J.; Davis J. Fecal Contamination and Diarrheal Pathogens on Surfaces and in Soils among Tanzanian Households with and without Improved Sanitation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46 (11), 5736–5743. 10.1021/es300022c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knappett P. S. K.; McKay L. D.; Layton A.; Williams D. E.; Alam M. J.; Huq M. R.; Mey J.; Feighery J. E.; Culligan P. J.; Mailloux B. J.; Zhuang J.; Escamilla V.; Emch M.; Perfect E.; Sayler G. S.; Ahmed K. M.; van Geen A. Implications of Fecal Bacteria Input from Latrine-Polluted Ponds for Wells in Sandy Aquifers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 46 (3), 1361–1370. 10.1021/es202773w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Förster M.; Sievert K.; Messler S.; Klimpel S.; Pfeffer K. Comprehensive Study on the Occurrence and Distribution of Pathogenic Microorganisms Carried by Synanthropic Flies Caught at Different Rural Locations in Germany. J. Med. Entomol. 2009, 46 (5), 1164–1166. 10.1603/033.046.0526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szalanski A. L.; Owens C. B.; McKay T.; Steelman C. D. Detection of Campylobacter and Escherichia Coli O157: H7 from Filth Flies by Polymerase Chain Reaction. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2004, 18 (3), 241–246. 10.1111/j.0269-283X.2004.00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doza S.; Rahman M. J.; Islam M. A.; Kwong L. H.; Unicomb L.; Ercumen A.; Pickering A. J.; Parvez S. M.; Naser A. M.; Ashraf S.; Das K. K.; Luby S. P. Prevalence and Association of Escherichia Coli and Diarrheagenic Escherichia Coli in Stored Foods for Young Children and Flies Caught in the Same Households in Rural Bangladesh. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2018, 98, tpmd170408. 10.4269/ajtmh.17-0408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen D.; Green M.; Block C.; Slepon R.; Ambar R.; Wasserman S.; Levine M. Reduction of Transmission of Shigellosis by Control of Houseflies (Musca Domestica). Lancet 1991, 337 (8748), 993–997. 10.1016/0140-6736(91)92657-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavasse D. C.; Shier R. P.; Murphy O. A.; Huttly S. R. A.; Cousens S. N.; Akhtar T. Impact of Fly Control on Childhood Diarrhoea in Pakistan: Community-Randomised Trial. Lancet 1999, 353 (9146), 22–25. 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)03366-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ercumen A.; Pickering A. J.; Kwong L. H.; Arnold B. F.; Parvez S. M.; Alam M.; Sen D.; Islam S.; Kullmann C.; Chase C.; Ahmed R.; Unicomb L.; Luby S. P.; Colford J. M. Animal Feces Contribute to Domestic Fecal Contamination: Evidence from E. Coli Measured in Water, Hands, Food, Flies, and Soil in Bangladesh. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51 (15), 8725–8734. 10.1021/acs.est.7b01710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George C. M.; Oldja L.; Biswas S.; Perin J.; Lee G. O.; Kosek M.; Sack R. B.; Ahmed S.; Haque R.; Parvin T.; Azmi I. J.; Bhuyian S. I.; Talukder K. A.; Mohammad S.; Faruque A. G. Geophagy Is Associated with Environmental Enteropathy and Stunting in Children in Rural Bangladesh. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2015, 92 (6), 1117–1124. 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BGS; DPHE. Arsenic Contamination of Groundwater in Bangladesh; Kinniburgh D. G., Smedley P. L., Eds.; British Geographical Survey Technical Report, British Geographical Survey: Keyworth, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Naser A. M.; Higgins E. M.; Arman S.; Ercumen A.; Ashraf S.; Das K. K.; Rahman M.; Luby S. P.; Unicomb L. Effect of Groundwater Iron on Residual Chlorine in Water Treated with Sodium Dichloroisocyanurate Tablets in Rural Bangladesh. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2018, 98, tpmd160954. 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold B. F.; Null C.; Luby S. P.; Unicomb L.; Stewart C. P.; Dewey K. G.; Ahmed T.; Ashraf S.; Christensen G.; Clasen T.; Dentz H. N.; Fernald L. C. H.; Haque R.; Hubbard A. E.; Kariger P.; Leontsini E.; Lin A.; Njenga S. M.; Pickering A. J.; Ram P. K.; Tofail F.; Winch P. J.; Colford J. M. Cluster-Randomised Controlled Trials of Individual and Combined Water, Sanitation, Hygiene and Nutritional Interventions in Rural Bangladesh and Kenya: The WASH Benefits Study Design and Rationale. BMJ. Open 2013, 3 (8), e003476. 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luby S. P.; Rahman M.; Arnold B. F.; Unicomb L.; Ashraf S.; Winch P. J.; Stewart C. P.; Begum F.; Hussain F.; Benjamin-Chung J.; Leontsini E.; Naser A. M.; Parvez S. M.; Hubbard A. E.; Lin A.; Nizame F. A.; Kaniz J.; Ercumen A.; Ram P. K.; Das K. K.; Abedin J.; Clasen T. F.; Dewey K. G.; Fernald L. C.; Clair N.; Tahmeed A.; Colford J. M. Effects of Water Quality, Sanitation, Handwashing, and Nutritional Interventions on Diarrhoea and Child Growth in Rural Bangladesh: A Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6 (3), e302–e315. 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30490-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin A.; Ercumen A.; Benjamin-Chung J.; Arnold B. F.; Das S.; Haque R.; Ashraf S.; Parvez S. M.; Unicomb L.; Rahman M.; Hubbard A. E.; Stewart C. P.; Colford J. M.; Luby S. P. Effects of Water, Sanitation, Handwashing, and Nutritional Interventions on Child Enteric Protozoan Infections in Rural Bangladesh: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 10.1093/cid/ciy320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ercumen A.; Benjamin-Chung J.; Arnold B.; Lin A.; Hubbard A.; Stewart C.; Parvez S.; Unicomb L.; Rahman M.; Haque R.; Colford J. M.; Luby S. P.. Effects of Water, Sanitation, Handwashing and Nutritional Interventions on Soil Transmitted Helminth Infections in Young Children: A Cluster-Randomised Controlled Trial in Rural Bangladesh. 2018, (in preparation). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Parvez S. M.; Azad R.; Rahman M.; Unicomb L.; Ram P. K.; Naser A. M.; Stewart C. P.; Jannat K.; Rahman M. J.; Leontsini E.; Winch P. J.; Luby S. P.. Achieving Optimal Technology and Behavioral Uptake of Single and Combined Interventions of Water, Sanitation Hygiene and Nutrition, in an Efficacy Trial (WASH Benefits) in Rural Bangladesh. Trials 2018, 19 ( (1), ). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unicomb L.; Begum F.; Leontsini E.; Rahman M.; Ashraf S.; Naser A. M.; Nizame F. A.; Jannat K.; Hussain F.; Parvez S. M.; Arman S.; Mobashara M.; Luby S. P.; Winch P. J. WASH Benefits Bangladesh Trial: Management Structure for Achieving High Coverage in an Efficacy Trial. Trials 2018, 19 (1), 359. 10.1186/s13063-018-2709-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M.; Ashraf S.; Unicomb L.; Mainuddin A. K. M.; Parvez S. M.; Begum F.; Das K. K.; Naser A. M.; Hussain F.; Clasen T.; Luby S. P.; Leontsini E.; Winch P. J. WASH Benefits Bangladesh Trial: System for Monitoring Coverage and Quality in an Efficacy Trial. Trials 2018, 19 (1), 360. 10.1186/s13063-018-2708-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO-UNICEF. Progress on Drinking Water and Sanitation: 2013 Update. Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation (JMP); WHO-UNICEF: New York, Geneva, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Halder A. K.; Tronchet C.; Akhter S.; Bhuiya A.; Johnston R.; Luby S. P. Observed Hand Cleanliness and Other Measures of Handwashing Behavior in Rural Bangladesh. BMC Public Health 2010, 10 (1), 545. 10.1186/1471-2458-10-545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandi B.The Fauna of India and the Adjacent Countries. Diptera: Sarcophagidae: Zoological Survey of India, 2002.

- Yakub G. P.; Castric D. A.; Stadterman-Knauer K. L.; Tobin M. J.; Blazina M.; Heineman T. N.; Yee G. Y.; Frazier L. Evaluation of Colilert and Enterolert Defined Substrate Methodology for Wastewater Applications. Water Environ. Res. 2002, 74 (2), 131–135. 10.2175/106143002X139839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helsel D. R. Less than Obvious - Statistical Treatment of Data below the Detection Limit. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1990, 24 (12), 1766–1774. 10.1021/es00082a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van der Laan M. J.; Polley E. C.; Hubbard A. E.. Super Learner. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2007, 6 ( (1), ). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gruber S.; van der Laan M. J.. Tmle: An R Package for Targeted Maximum Likelihood Estimation. 2011.

- Ahmed K. M.; Bhattacharya P.; Hasan M. A.; Akhter S. H.; Alam S. M. M.; Bhuyian M. A. H.; Imam M. B.; Khan A. A.; Sracek O. Arsenic Enrichment in Groundwater of the Alluvial Aquifers in Bangladesh: An Overview. Appl. Geochem. 2004, 19 (2), 181–200. 10.1016/j.apgeochem.2003.09.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ram P. K.; Halder A. K.; Granger S. P.; Jones T.; Hall P.; Hitchcock D.; Wright R.; Nygren B.; Islam M. S.; Molyneaux J. W.; Luby S. P. Is Structured Observation a Valid Technique to Measure Handwashing Behavior? Use of Acceleration Sensors Embedded in Soap to Assess Reactivity to Structured Observation. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2010, 83 (5), 1070–1076. 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam M.; Ercumen A.; Ashraf S.; Rahman M.; Shoab A. K.; Luby S. P.; Unicomb L. Unsafe Disposal of Feces of Children < 3 Years among Households with Latrine Access in Rural Bangladesh: Association with Household Characteristics, Fly Presence and Child Diarrhea. PLoS One 2018, 13 (4), e0195218. 10.1371/journal.pone.0195218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin-Chung J.; Amin N.; Ercumen A.; Arnold B. F.; Hubbard A. E.; Unicomb L.; Rahman M.; Luby S. P.; Colford J. M. A Randomized Controlled Trial to Measure Spillover Effects of a Combined Water, Sanitation, and Handwashing Intervention in Rural Bangladesh. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 187, 1733. 10.1093/aje/kwy046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres L.; Briceno B.; Chase C.; Echenique J. A.. Sanitation and Externalities: Evidence from Early Childhood Health in Rural India, SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 2375456; Social Science Research Network: Rochester, NY, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller J. A.; Villamor E.; Cevallos W.; Trostle J.; Eisenberg J. N. I Get Height with a Little Help from My Friends: Herd Protection from Sanitation on Child Growth in Rural Ecuador. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 45 (2), 460–469. 10.1093/ije/dyv368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris M.; Alzua M. L.; Osbert N.; Pickering A. Community-Level Sanitation Coverage More Strongly Associated with Child Growth and Household Drinking Water Quality than Access to a Private Toilet in Rural Mali. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51 (12), 7219–7227. 10.1021/acs.est.7b00178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knappett P. S. K.; Escamilla V.; Layton A.; McKay L. D.; Emch M.; Williams D. E.; Huq R.; Alam J.; Farhana L.; Mailloux B. J.; Ferguson A.; Sayler G. S.; Ahmed K. M.; van Geen A. Impact of Population and Latrines on Fecal Contamination of Ponds in Rural Bangladesh. Sci. Total Environ. 2011, 409 (17), 3174–3182. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.04.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escamilla V.; Knappett P. S. K.; Yunus M.; Streatfield P. K.; Emch M. Influence of Latrine Proximity and Type on Tubewell Water Quality and Diarrheal Disease in Bangladesh. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2013, 103 (2), 299–308. 10.1080/00045608.2013.756257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ercumen A.; Naser A. M.; Arnold B. F.; Unicomb L.; Colford J. M.; Luby S. P. Can Sanitary Inspection Surveys Predict Risk of Microbiological Contamination of Groundwater Sources? Evidence from Shallow Tubewells in Rural Bangladesh. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017, 96 (3), 561–568. 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravenscroft P.; Mahmud Z. H.; Islam M. S.; Hossain A. K. M. Z.; Zahid A.; Saha G. C.; Zulfiquar Ali A. H. M.; Islam K.; Cairncross S.; Clemens J. D.; Islam S. M. The Public Health Significance of Latrines Discharging to Groundwater Used for Drinking. Water Res. 2017, 124, 192–201. 10.1016/j.watres.2017.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knappett P. S. K.; McKay L. D.; Layton A.; Williams D. E.; Alam M. J.; Mailloux B. J.; Ferguson A. S.; Culligan P. J.; Serre M. L.; Emch M.; Ahmed K. M.; Sayler G. S.; van Geen A. Unsealed Tubewells Lead to Increased Fecal Contamination of Drinking Water. J. Water Health 2012, 10 (4), 565. 10.2166/wh.2012.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santamaría J.; Toranzos G. A. Enteric Pathogens and Soil: A Short Review. Int. Microbiol. 2003, 6 (1), 5–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byappanahalli M. N.; Fujikoa R. S. Evidence That Tropical Soil Environment Can Support the Growth of Escherichia Coli. Water Sci. Technol. 1998, 38 (12), 171–174. 10.2166/wst.1998.0533. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fujioka R.; Sian-Denton C.; Borja M.; Castro J.; Morphew K. Soil: The Environmental Source of Escherichia Coli and Enterococci in Guam’s Streams. J. Appl. Microbiol. 1998, 85 (S1), 83S–89S. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1998.tb05286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh S.; Buddenborg S.; Yoder-Himes D. R.; Tiedje J. M.; Konstantinidis K. T. Genomic Diversity of Escherichia Isolates from Diverse Habitats. PLoS One 2012, 7 (10), e47005. 10.1371/journal.pone.0047005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto D. K.; Yan T. Genotypic Diversity of Escherichia Coli in the Water and Soil of Tropical Watersheds in Hawaii ∇. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77 (12), 3988–3997. 10.1128/AEM.02140-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julian T. R.; Islam M. A.; Pickering A. J.; Roy S.; Fuhrmeister E. R.; Ercumen A.; Harris A.; Bishai J.; Schwab K. J. Genotypic and Phenotypic Characterization of Escherichia Coli Isolates from Feces, Hands, and Soils in Rural Bangladesh via the Colilert Quanti-Tray System. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81 (5), 1735–1743. 10.1128/AEM.03214-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinton L. W.; Finlay R. K.; Hannah D. J. Distinguishing Human from Animal Faecal Contamination in Water: A Review. N. Z. J. Mar. Freshwater Res. 1998, 32 (2), 323–348. 10.1080/00288330.1998.9516828. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boehm A. B.; Wang D.; Ercumen A.; Shea M.; Harris A. R.; Shanks O. C.; Kelty C.; Ahmed A.; Mahmud Z. H.; Arnold B. F.; Chase C.; Kullman C.; Colford J. M.; Luby S. P.; Pickering A. J. Occurrence of Host-Associated Fecal Markers on Child Hands, Household Soil, and Drinking Water in Rural Bangladeshi Households. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2016, 3 (11), 393–398. 10.1021/acs.estlett.6b00382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.