Abstract

Background

Our objective was to determine patterns of antihypertensive agent use by stage of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and to evaluate the association between different classes of antihypertensive agents with nonrenal outcomes, especially in advanced CKD.

Methods and Results

We studied 3939 participants of the CRIC (Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort) study. Predictors were time‐dependent angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker , β‐blocker, and calcium channel blocker use (versus nonuse of agents in each class). Outcomes were adjudicated heart failure events or death. Adjusted Cox models were used to determine the association between predictors and outcomes. We also examined whether the associations differed based on the severity of CKD (early [stage 2–3 CKD] versus advanced disease [stage 4–5 CKD]). During median follow‐up of 7.5 years, renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system inhibitor use plateaued during CKD stage 3 (75%) and declined to 37% by stage 5, while β‐blocker, calcium channel blocker, and diuretic use increased steadily with advancing CKD. Renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system inhibitor use was associated with lower risk of heart failure (hazard ratio, 0.79; 95% confidence interval, 0.67–0.97) and death (hazard ratio, 0.78; 95% confidence interval, 0.67–0.90), regardless of severity of CKD. Calcium channel blocker use was not associated with risk of heart failure or death, regardless of the severity of CKD. β‐Blocker use was associated with higher risk of heart failure (hazard ratio, 1.62; 95% confidence interval, 1.29–2.04) and death (hazard ratio, 1.22; 95% confidence interval, 1.03–1.43), especially during early CKD (P<0.05 for interaction).

Conclusions

Angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor and angiotensin receptor blocker use decreased, while use of other agents increased with advancing CKD. Use of agents besides angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers may be associated with suboptimal outcomes in patients with CKD.

Keywords: heart failure, hypertension, kidney

Subject Categories: Heart Failure, Hypertension

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

We examined patterns of antihypertensive use with advancing chronic kidney disease, and how the class of antihypertensive agent used associate differentially with adverse outcomes.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Use of β‐blockers, calcium channel blockers, and diuretics steadily increased, whereas use of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers decreased with advancing chronic kidney disease.

Use of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers was associated with lower risk of heart failure and death, whereas use of β‐blockers was associated with higher risk of both outcomes.

Use of calcium channel blockers was not associated with these adverse outcomes. Nonuse of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers with advancing chronic kidney disease may associate with suboptimal outcomes.

Introduction

Hypertension affects over 85 million Americans, and >15% of patients with hypertension also have chronic kidney disease (CKD).1 Yet the class or classes of antihypertensive medications that should be used to optimize outcomes in the CKD population remain unclear.1 Use of renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system inhibitors such as angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) has been shown to delay the progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD). Thus, ACEIs and ARBs are currently the preferred agents in the CKD population.2, 3, 4, 5

While there are data to support the benefit of ACEI and ARB use during the early stages of CKD (stage 3) for both renal and cardiovascular benefit,6 especially among patients with diabetes mellitus,7 less data are available to support the benefit of ACEI and ARB use on outcomes in more advanced CKD (stage 4 or 5). There are also sparse data about how calcium channel blockers (CCBs) or β‐blockers (BBs) may be associated with risk of cardiovascular outcomes or death in the CKD population. Few head‐to‐head comparisons of the effect of different classes of antihypertensive medications on renal or nonrenal outcomes have been conducted, and many of the trials of the use of different antihypertensive classes have been placebo controlled.6, 7

The objectives of this study were to examine patterns and predictors of the class of antihypertensive medications used across CKD stages 2 to 5 in a well‐characterized cohort of participants with CKD followed longitudinally in the CRIC (Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort) study, with a focus on ACEI and ARB use. We also examined the association of ACEI and ARB, CCB, or BB use with risk of adjudicated heart failure (HF) events and all‐cause mortality, and determined whether these associations varied based on the severity of CKD (early versus advanced stages).

Methods

Study Population

The CRIC Study is a national multicenter observational cohort that enrolled participants with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) between 20 and 70 mL/min per 1.73 m2 based on the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation between June 2003 and September 2008. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were published previously, and the study is ongoing.8, 9 Informed consent was obtained from CRIC participants at all local sites. We used data from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) Central Repository in this analysis, and follow‐up time was censored as of March 31, 2013. The University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board considers this study exempt human subjects research.

The data and study materials will not be made available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results, as these data are publicly available at no cost through the NIDDK Central Repository, and the NIDDK Central Repository prohibits re‐release of these data.

Predictors of the Use of Antihypertensive Agents by Stage of CKD

Medication use was reported by CRIC participants at annual visits. We were primarily interested in the use of ACEIs or ARBs, CCBs, BBs, and diuretic use (especially loop and thiazide diuretics) across the different stages of CKD and the changes in therapy that occurred with the progression of CKD. We used person‐specific trajectories of renal function decline from mixed models to identify the time points when transitions to each subsequent CKD stage occurred as previously described.10 In analyses of use of antihypertensive agents across the different stages of CKD, participants were classified as “users” if they reported use of the medication at the first visit after their identified transition to the subsequent stage of CKD. The stages of CKD were defined based on eGFR falling below 90, 60, 45, 30, and 15 mL/min per 1.73 m2 for CKD stages 2, 3a, 3b, 4, and 5, respectively.11 Because use of ACEIs and ARBs may be more common among patients with substantial proteinuria, we also examined the prevalence of ACEI or ARB use according to the degree of proteinuria at the time of entry into each stage of CKD (≥1 versus <1 g/g of proteinuria).

If data on use of antihypertensive agents were missing, then data from the prior visit were carried forward. We also examined the number of total antihypertensive medications used in each stage of CKD (including diuretics).

Clinical Predictors of ACEI or ARB Use by Each CKD Stage

Next, we examined predictors of ACEI or ARB use at entry into each stage of CKD in (separate) multivariable logistic regression models as specified a priori given the solid indication for the use of ACEIs or ARBs (over other classes of antihypertensive agents) according to guideline recommendations in CKD.12, 13 The outcome of interest in these logistic models was ACEI or ARB use (yes/no) as a binary outcome. Factors of interest included age at enrollment (≥60 versus <60 years), sex, race, annual household income, proteinuria (≥1 or <1 g/g), HF, myocardial infarction or revascularization, stroke, diabetes mellitus, obesity (body mass index ≥30 kg/m2), uncontrolled systolic blood pressure (≥140 mm Hg versus <140 mm Hg), concurrent use of other antihypertensive medications (CCBs and BBs), concurrent diuretic use, and potassium concentration. We also tested for interactions between each of these risk factors and stage of CKD in fully adjusted models.

Association Between Time‐Updated Antihypertensive Medication Use and Risk of HF

We examined the association between use of each class of antihypertensive agent as a time‐dependent predictor of HF, a primary outcome of interest. Time‐dependent use of ACEIs or ARBs was based on self‐report and updated annually, with missing values carried forward in Fine‐Gray models using a counting process formulation of these models.14 We chose to focus on HF as the cardiovascular outcome of interest, as it was the most common event and hence would provide the most power. Two independent reviewers adjudicated HF events in the CRIC study, and we included only events classified as “definite.”15, 16, 17 Criteria used for the definition of an HF event were based on symptoms, radiographic changes (such as pulmonary edema), or physical examination findings (such as presence of rales and peripheral edema), central venous hemodynamic monitoring data, and review of echocardiogram data.17, 18

Our primary models were adjusted Fine‐Gray models (treating death as a competing risk) that accounted for age, sex, race, income status, baseline HF, baseline myocardial infarction, baseline peripheral artery disease, baseline stroke, baseline eGFR (by Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration creatinine‐based equation19), baseline proteinuria (<1 versus ≥1 g/g), and time‐dependent covariates including diabetes mellitus, obesity (body mass index ≥30 kg/m2), systolic blood pressure (BP), statin use, aspirin use, diuretic use, and concurrent use of other antihypertensive agents (CCBs and BBs) for the outcome of HF. Because we were interested in the risks or benefits associated with the use of each class of antihypertensive agent independent of achieved BP control, we chose to adjust for absolute systolic BP levels in these models.

We repeated our primary analysis using time‐dependent BB or CCB use at each visit as our primary predictors of interest (and therefore adjusting for ACEI or ARB use) for the outcome of HF. We did not focus on diuretics as a primary predictor in these main analyses given the greater potential for confounding by indication due to volume overload, especially since HF was the outcome of interest, although we did adjust for diuretic use in our primary models. To reduce the likelihood of confounding by indication, we performed a sensitivity analysis for the outcome of HF in which we repeated our analysis among the subgroup without baseline HF (who would not be receiving treatment with specific classes of antihypertensive agents for secondary prevention of HF). In secondary analyses, we examined the association between diuretic use (versus nonuse) and the risk of HF.

We did not adjust for time‐updated proteinuria and eGFR in our primary models, given that both BP control and ACEI or ARB use may reduce proteinuria or be associated with changes in eGFR and may be a potential mediator of outcomes of interest. However, in sensitivity analysis, we additionally adjusted for time‐updated eGFR and proteinuria (categorized as <1 versus ≥1 g/g).

Association Between Time‐Updated Antihypertensive Medication Use and Risk of Death

We used unadjusted and adjusted Cox models to examine the association between use of each class of antihypertensive agent and death, adjusting for the same covariates as described above. Deaths were identified through report from next of kin, retrieval of death certificates or obituaries, review of hospital records, and linkage with the Social Security Death Index.

Association Between Class of Antihypertensive Medication Use With Risk of Adverse Outcomes by CKD Severity

We tested for interaction between use of each class of antihypertensive medication (ACEIs and ARBs, CCBs, or BBs) and CKD severity (early CKD defined as eGFR by Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation ≥30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 [stage 2–3] versus advanced CKD defined as <30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 [stage 4–5 disease]) in unadjusted and adjusted Fine‐Gray or Cox models for both the outcomes of HF and death, respectively.

All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, NC). Informed consent was obtained for participation at all CRIC study sites.

Results

Patterns and Prevalence of Antihypertensive Agent Use

A total of 3939 CRIC participants (100%) were included for analysis; baseline characteristics of CRIC participants were previously described.8 Overall, mean age was 58 years, 42% were black, mean body mass index was 32 kg/m2, median eGFR was 43 mL/min per 1.73 m2, median urine protein/creatinine ratio was 0.2 g/g, and one half had diabetes mellitus at the time of enrollment (Table S1). Approximately 70% of participants reported ACEI or ARB use at baseline, about one half reported BB use, and 41% reported CCB use at enrollment.

With advancing stages of CKD, the number of participants receiving 3 or more antihypertensive medications steadily increased from 25% in CKD stage 2 to 75% in CKD stage 5 (Figure S1). By CKD stage 5, 98% of participants were receiving at least 1 antihypertensive agent (Figure S1).

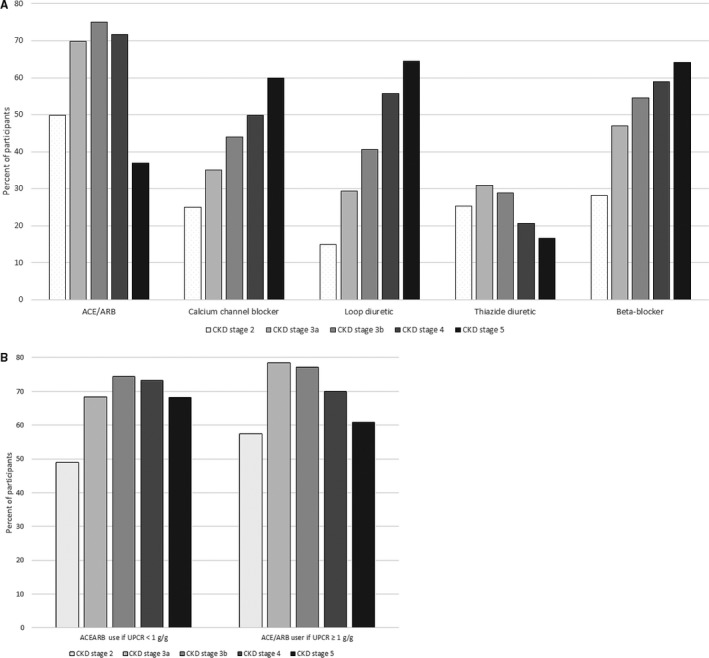

Use of antihypertensive agents by stage of CKD is shown in the Figure—Panel A. Only approximately one half of CRIC participants were using ACEIs or ARBs in CKD stage 2. The prevalence of ACEI or ARB use increased to >75% by stage 3b and then declined to ≈37% in stage 5 (Figure—Panel A). Thiazide diuretic use after CKD stage 3a was also less common. Use of other non–renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system antihypertensive agents steadily increased with advancing CKD (Figure—Panel A). Across stages of CKD, the pattern of ACEI or ARB use was similar among the subgroup with significant proteinuria (≥1 g/g) at the first visit upon entry into each stage of CKD (Figure—Panel B).

Figure 1.

A, Use of different classes of antihypertensive agents by stage of CKD. B, Use of different classes of antihypertensive agents by stage of CKD and degree of proteinuria. ACE indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CKD, chronic kidney disease; UPCR, urine protein/creatinine ratio.

Clinical Predictors of ACEI or ARB Use by Each CKD Stage

In multivariable analysis, women were less likely to receive an ACEI or ARB compared with men in CKD stages 2 to 4 (Table 1). Higher household income, black race, diabetes mellitus, obesity, and higher potassium levels were associated with ACEI or ARB use across CKD stages 3 to 5 (Table 1). Diuretic use was associated with ACEI or ARB use in stage 3a and 3b CKD but not in more advanced stages of CKD when diuretic use became more prevalent. A history of HF was not statistically significantly associated with ACEI or ARB use across any of the CKD stages (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical Predictors of ACEI or ARB Use as the Outcome of Interest by Each CKD Stage

| CKD Stage | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 (N=454) | 3a (N=1419) | 3b (N=2127) | 4 to 5 (N=1677) | |

| Age ≥60 y (vs age <60 y) | 1.09 (0.61–1.95) | 0.92 (0.71–1.19) | 1.06 (0.85–1.32) | 0.92 (0.72–1.17) |

| Female (vs male) | 0.41 (0.27–0.64)a | 0.60 (0.47–0.77)a | 0.71 (0.57–0.88)a | 0.86 (0.69–1.08) |

| Race | ||||

| White | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Black | 1.14 (0.69–1.89) | 1.57 (1.16–2.13)a | 1.41 (1.09–1.81)a | 1.24 (0.93–1.65) |

| Hispanic | 1.07 (.44–2.63) | 1.07 (0.66–1.73) | 1.25 (0.88–1.78) | 1.02 (0.70–1.47) |

| Incomeb | ||||

| ≤$20 000 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 20 001 to 50 000 | 1.06 (0.52–2.13) | 1.63 (1.13–2.37)a | 1.62 (1.23–2.14)a | 1.29 (0.96–1.72) |

| 50 001 to 100 000 | 1.05 (0.52–2.09) | 1.65 (1.11–2.44)a | 2.50 (1.77–3.50)a | 2.59 (1.74–3.83)a |

| ≥100 000 | 0.89 (0.39–1.99) | 1.44 (0.92–2.25) | 2.35 (1.49–3.71)a | 3.48 (1.89–6.42)a |

| Proteinuria ≥1 g/g | 0.79 (0.36–1.70) | 1.40 (0.95–2.06) | 1.06 (0.82–1.37)‡ | 0.80 (0.63–1.02)‡ |

| HF | 2.41 (0.62–9.43) | 1.53 (0.87–2.69) | 1.11 (0.77–1.62) | 1.30 (0.91–1.88) |

| Stroke | 0.91 (0.28–2.96) | 1.85 (1.12–3.04)a | 1.08 (0.78–1.51) | 1.20 (0.85–1.69) |

| MI/revascularization | 2.63 (1.10–6.29)a | 1.38 (0.97–1.97) | 1.01 (0.77–1.32) | 0.95 (0.72–1.26) |

| Obese (vs <30 kg/m2) | 1.35 (0.87–2.10) | 1.56 (1.21–2.03)a | 1.43 (1.15–1.78)a | 1.75 (1.39–2.21)a |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3.78 (2.27–6.26)a | 1.80 (1.37–2.37)a | 2.07 (1.64–2.59)a | 1.78 (1.38–2.28)a ,‡ |

| Uncontrolled SBP ≥140 mm Hg (vs SBP <140 mm Hg) | 2.84 (1.38–5.87)a | 0.79 (0.57–1.08) | 0.85 (0.66–1.08) | 0.86 (0.67–1.10) |

| β‐Blocker use (vs nonuse) | 1.16 (0.70–1.94) | 0.95 (0.73–1.25) | 0.94 (0.75–1.18) | 0.81 (0.63–1.04) |

| Diuretic use (vs nonuse) | 1.54 (0.93–2.53) | 1.56 (1.19–2.05)a | 1.38 (1.09–1.74)a | 1.17 (0.90–1.53) |

| Calcium channel blocker use (vs nonuse) | 1.58 (0.94–2.64) | 1.53 (1.16–2.03)a | 0.90 (0.73–1.12) | 0.92 (0.73–1.16) |

| Potassium (per 1 mEq/L higher) | 1.56 (0.90–2.70) | 2.15 (1.61–2.86)a | 2.10 (1.69–2.61)a | 1.75 (1.42–2.14)a ,‡ |

ACEI indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CI, confidence interval; CKD, chronic kidney disease; HF, heart failure; MI, myocardial infarction; Ref, reference; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

P<0.05 for interaction for each stage of CKD and predictor of interest, using CKD stage 3a as the reference group.

Excludes those with missing income data or refusal to answer.

Association Between Time‐Updated Antihypertensive Use and Risk of HF

During median follow‐up of 7.0 years, 491 participants had an adjudicated HF event. Among those with HF and echocardiogram data that were available after the onset of HF (N=219), the mean ejection fraction was 44% (standard deviation, 13%).

In multivariable analysis, ACEI or ARB use was associated with lower risk of HF (hazard ratio [HR], 0.79; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.64–0.97) regardless of CKD severity (Table 2). CCB use was not statistically significantly associated with risk of HF (HR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.79–1.16), regardless of CKD severity. BB use was associated with higher risk of HF, regardless of CKD severity (HR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.29–2.04; Table 2).

Table 2.

Risk of Adjudicated Heart Failurea Based on Time‐Updated Antihypertensive Medication Use

| Heart Failure (N=3939) | Unadjusted Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted Hazard Ratiob (95% CI) | Adjusted P Value of Interaction by eGFR (≥ or <30 mL/min per 1.73 m2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACEI or ARB use | 0.91 (0.75–1.09) | 0.79 (0.64–0.97) | 0.29 |

| Calcium‐channel blocker | 1.34 (1.12–1.60) | 0.96 (0.79–1.16) | 0.08 |

| β‐Blocker | 2.98 (2.41–3.68) | 1.62 (1.29–2.04) | 0.73 |

ACEI indicates angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CI, confidence interval; CKD‐EPI, Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HF, heart failure; MI, myocardial infarction; PAD, peripheral artery disease.

Defined as HF (definite event).

Adjusted for baseline age, race, sex, income, baseline CHF, baseline MI, baseline stroke, baseline PAD, baseline eGFR (by CKD‐EPI), baseline proteinuria (≥1 or <1 g/g), and time‐updated covariates including diabetes mellitus, obese (yes/no BMI ≥30 kg/m2), systolic BP, aspirin use, statin use, diuretic use, and other antihypertensive medication use (calcium channel blocker, ACEIs or ARBs, or β‐blockers).

Among the subgroup with no HF at baseline (N=3557), we observed the same general patterns of risk. For example, ACEI or ARB use was associated with lower risk of HF (HR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.59–0.95), whereas BB (HR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.23–2.08) was persistently associated with higher risk of HF among those without baseline HF. CCB use was not associated with risk of HF (HR, 1.16; 95% CI, 0.92–1.47).

In secondary analyses, diuretic use was associated with higher risk of HF in adjusted Fine‐Gray models (HR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.43–2.32).

In sensitivity analysis, when we additionally adjusted models for proteinuria as a time‐updated covariate, our overall findings were similar for the outcome of HF (Table S2). However, the protective association between ACEI or ARB use and HF was further attenuated with the addition of time‐updated eGFR and proteinuria as covariates (HR; 0.82; 95% CI, 0.67–1.02).

Association Between Time‐Updated Antihypertensive Use and Risk of Death

For the outcome of all‐cause mortality, use of ACEIs or ARBs was associated with lower risk of death (HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.67–0.90), regardless of CKD severity (P=0.19 for interaction). CCB use was not associated with risk of death (HR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.79–1.06). BB use was associated with a higher risk of death (HR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.03–1.43), although the association was stronger during the early versus more advanced stages of CKD (P=0.02 for interaction; Table 3).

Table 3.

Risk of Death Based on Time‐Updated Antihypertensive Medication Use

| N=3939 | Unadjusted Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted Hazard Ratioa (95% CI) | Adjusted P Value of Interaction by eGFR (≥30 or <30 mL/min per 1.73 m2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| All‐cause mortality | |||

| ACEI or ARB use | 0.75 (0.65–0.86) | 0.78 (0.67–0.90) | 0.19 |

| Calcium channel blocker | 1.20 (1.05–1.37) | 0.92 (0.79–1.06) | 0.39 |

| β‐Blocker | 2.00 (1.73–2.31) | 1.22 (1.03–1.43) | 0.02 |

| eGFR ≥30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 2.04 (1.72–2.43) | 1.23 (1.02–1.49) | |

| eGFR <30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 1.57 (1.19–2.07) | 1.14 (0.84–1.55) | |

ACEI indicates angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CI, confidence interval; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HF, heart failure; MI, myocardial infarction; PAD, peripheral artery disease.

Adjusted for baseline age, race, sex, income, baseline HF, baseline MI, baseline stroke, baseline PAD, baseline eGFR, baseline proteinuria (≥1 or <1 g/g), and time‐updated covariates including diabetes mellitus, obesity (yes/no BMI >30 kg/m2), systolic BP, aspirin use, statin use, diuretic use, and other antihypertensive medication use (calcium channel blocker, ACEIs or ARBs, or β‐blockers).

In sensitivity analysis, when we additionally adjusted models for proteinuria as a time‐updated covariate, our overall findings were similar for the risk of death (Table S2).

In secondary analysis, diuretic use was not associated with risk of death (HR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.94–1.28) in adjusted Cox models.

Discussion

A number of trials have examined the effect of different classes of BP medications on cardiovascular and kidney outcomes,3, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 but the majority of these trials were conducted in people with normal kidney function or mild renal impairment, and few trials have provided long‐term data on mortality outcomes.27, 28 In this study, we found that ACEI or ARB use began to decline after CKD stage 3b and was not as prevalent as would be expected, especially among participants with substantial proteinuria for whom guidelines clearly recommend ACEIs or ARBs as first‐line agents.12, 13 In contrast, use of CCBs, diuretics, and BBs increased steadily with advancing stages of CKD. Even after accounting for systolic BP control, we found that ACEI or ARB use was associated with a substantially lower risk of HF and death. CCB use was not associated with risk of HF or death. However, BB use was associated with a higher risk of HF and death, especially during the early stages of CKD.

Currently, the American Heart Association guidelines for high BP recommend using ACEIs or ARBs as first‐line therapy for patients with CKD stage 3 and higher, or for patients with CKD stage 1 to 2 with albuminuria ≥300 mg/g.1 These recommendations are primarily based on the added benefit of proteinuria reduction associated with the use of ACEIs or ARBs, which has been shown to slow CKD progression.13 However, we noted that ACEI or ARB use decreased substantially from stage 3b to stage 5, and 63% of participants were not receiving ACEIs or ARBs by the time they reached CKD stage 5 despite the fact that 98% were receiving antihypertensive agents. Even at their peak use, only three quarters of CRIC participants with proteinuria ≥1 g/g were receiving guideline‐recommended ACEI or ARB therapy. Participants who were obese and had diabetes mellitus were more likely to receive ACEI or ARB therapy, whereas women were less likely to receive these agents. Whether this observation is related to concerns about fetal risks during pregnancy with these agents is unclear.

Although we do not have data to address why so many participants were not receiving guideline‐recommended treatment of CKD and hypertension, we expect that providers might have been concerned about risk (or occurrence) of acute kidney injury or hyperkalemia with use of ACEIs or ARBs.29 Despite their known efficacy, the prevalence of ACEI and ARB use in patients with CKD has been reported to be low, even when there are solid indications for their use (eg, diabetic nephropathy or HF).30, 31, 32, 33 However, we believe that our study provides new information that may warrant greater caution in withdrawing ACEIs or ARBs in the short term and highlights the need for interventional trials of alternative strategies in the future. For example, the availability of newer potassium binders that may be better tolerated than sodium polystyrene and safer for long‐term use34, 35, 36, 37 presents the opportunity to continue ACEIs or ARBs, even in the advanced stages of CKD. In light of the beneficial association between ACEI or ARB use and risk of HF and death (that may at least be partially mediated by their effect on proteinuria), prospective clinical trials are warranted to examine whether these strategies reduce HF and mortality.35

We believe the finding of a substantially higher risk of HF and mortality risk with β‐blocker use in our study to be important, particularly since this association was present even among those without known HF at enrollment. Patients receiving BBs have also been reported to have a higher risk of cardiovascular events (including HF) in cohorts without CKD and in the perioperative setting.38, 39 In addition, a number of large meta‐analyses have suggested that BB use was associated with a higher risk of stroke and death in the general population.40, 41 In contrast, a meta‐analysis of trials of patients with CKD suggested that BBs conferred a benefit on the risk of mortality and HF despite a higher risk of hypotension and bradycardia.42 The strong association between BB use and risk of adverse outcomes in our study deserves further investigation to understand the reasons for this observation. However, we do emphasize that there may be other compelling indications for the continuation of β‐blockade (such as in the setting of angina or myocardial infarction) outside of the outcomes of interest that we examined.

Of note, we did not find CCB use to be associated with the risk of HF or death. Given that few trials have tested CCBs against alternate classes of antihypertensive agents in patients with CKD (especially those with advanced disease), further studies are needed to confirm our findings. In our secondary analyses, we found a higher risk of HF but not death with diuretic use (versus nonuse), but we recognize that these results may be prone to confounding by indication.

The strengths of our study include the large cohort size, its national representativeness, long duration of follow‐up, large number of events, and formal adjudication of HF events. In addition, we believe that the use of research‐grade data collected during routine study visits (as opposed to using electronic health records where ascertainment bias may occur in sicker patients who are seen more frequently) is a strength. However, because of the observational nature of our study, we cannot rule out the presence of residual confounding or confounding by indication, and our results do not imply causation. In addition, we did not have granular detail on the specific medications that were used (eg, atenolol versus metoprolol), their dosage, or participant adherence to therapy. Although medication use in CRIC was ascertained on an annual basis, we are unable to capture any changes that occurred between the yearly visits and their associated changes in BP and albuminuria in the short term. We also did not have data on the reasons that patients were not receiving ACEIs or ARBs or other antihypertensive agents, including historical episodes of hyperkalemia or acute kidney injury that may have limited renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system inhibition. We also lacked data on causes of death and hence were unable to examine cardiovascular‐specific mortality. Finally, CRIC participants may not be representative of patients who are not managed by nephrologists.

In conclusion, we observed an association between ACEI or ARB use and lower risk of HF and death, but >60% of the CRIC population was not receiving ACEIs or ARBs in some stages of disease. BB use was associated with higher risk of HF and death, especially during the earlier stages of CKD. CCBs were not associated with risk of HF or death. Given the decline in use of ACEIs or ARBs with advancing stages of CKD and increase in use of alternative antihypertensive agents, optimizing use of ACEIs or ARBs throughout all stages of CKD may be associated with improved outcomes, and use of BBs may be associated with adverse outcomes. Future trials are needed to determine the optimal antihypertensive agents in the various stages of CKD, and the inclusion of more patients with more advanced CKD in clinical trials is needed to enhance our understanding of how to optimize outcomes for this high‐risk population.

Sources of Funding

Dr Ku was funded by National Institutes of Health K23 HL131023. This work was also supported by the National Institutes of Health K24 DK85153 to Dr Johansen. The CRIC study was conducted by the CRIC Investigators and supported by the NIDDK.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Table S1. Characteristics at First Visit in CRIC of Those Included for Analysis

Table S2. Sensitivity Analysis Using Adjusted* Cox Models That Account for Time‐Updated Proteinuria and Renal Function for Outcomes of Heart Failure and Death

Figure S1. Number of antihypertensive agents used by stage of CKD.

Acknowledgments

The data from the CRIC study reported here were supplied by the NIDDK Central Repositories. This manuscript was not prepared in collaboration with Investigators of the CRIC study and does not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the CRIC study, the NIDDK Central Repositories, or the NIDDK.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e009992 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.118.009992.)

References

- 1. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, DePalma SM, Gidding S, Jamerson KA, Jones DW, MacLaughlin EJ, Muntner P, Ovbiagele B, Smith SC Jr, Spencer CC, Stafford RS, Taler SJ, Thomas RJ, Williams KA Sr, Williamson JD, Wright JT Jr. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APHA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71:e13–e115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, Keane WF, Mitch WE, Parving HH, Remuzzi G, Snapinn SM, Zhang Z, Shahinfar S. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:861–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Clarke WR, Berl T, Pohl MA, Lewis JB, Ritz E, Atkins RC, Rohde R, Raz I. Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin‐receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:851–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Remuzzi G, Chiurchiu C, Ruggenenti P. Proteinuria predicting outcome in renal disease: nondiabetic nephropathies (REIN). Kidney Int Suppl. 2004;92:S90–S96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Weir MR, Lakkis JI, Jaar B, Rocco MV, Choi MJ, Mattrix‐Kramer H, Ku E. Use of renin‐angiotensin system blockade in advanced ckd: An NKF‐KDOQI controversies report. Am J Kidney Dis. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/american-journal-of-kidney-diseases/articles-in-press. Accessed September 20, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xie X, Liu Y, Perkovic V, Li X, Ninomiya T, Hou W, Zhao N, Liu L, Lv J, Zhang H, Wang H. Renin‐angiotensin system inhibitors and kidney and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with CKD: a Bayesian network meta‐analysis of randomized clinical trials. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67:728–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wu HY, Huang JW, Lin HJ, Liao WC, Peng YS, Hung KY, Wu KD, Tu YK, Chien KL. Comparative effectiveness of renin‐angiotensin system blockers and other antihypertensive drugs in patients with diabetes: systematic review and Bayesian network meta‐analysis. BMJ. 2013;347:f6008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Feldman HI, Appel LJ, Chertow GM, Cifelli D, Cizman B, Daugirdas J, Fink JC, Franklin‐Becker ED, Go AS, Hamm LL, He J, Hostetter T, Hsu CY, Jamerson K, Joffe M, Kusek JW, Landis JR, Lash JP, Miller ER, Mohler ER III, Muntner P, Ojo AO, Rahman M, Townsend RR, Wright JT; Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Study I . The Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study: design and methods. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:S148–S153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lash JP, Go AS, Appel LJ, He J, Ojo A, Rahman M, Townsend RR, Xie D, Cifelli D, Cohan J, Fink JC, Fischer MJ, Gadegbeku C, Hamm LL, Kusek JW, Landis JR, Narva A, Robinson N, Teal V, Feldman HI; Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Study G . Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) study: baseline characteristics and associations with kidney function. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:1302–1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ku E, Johansen KL, McCulloch C. Time‐centered approach to understanding risk factors for the progression of CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13:693–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stevens PE, Levin A. Evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease: synopsis of the kidney disease: improving global outcomes 2012 clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:825–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. KDIGO group . KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2013;3(suppl):1–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Taler SJ, Agarwal R, Bakris GL, Flynn JT, Nilsson PM, Rahman M, Sanders PW, Textor SC, Weir MR, Townsend RR. KDOQI US commentary on the 2012 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for management of blood pressure in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62:201–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang Z, Reinikainen J, Adeleke KA, Pieterse ME, Groothuis‐Oudshoorn CGM. Time‐varying covariates and coefficients in Cox regression models. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6:121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liu KD, Yang W, Go AS, Anderson AH, Feldman HI, Fischer MJ, He J, Kallem RR, Kusek JW, Master SR, Miller ER III, Rosas SE, Steigerwalt S, Tao K, Weir MR, Hsu CY. Urine neutrophil gelatinase‐associated lipocalin and risk of cardiovascular disease and death in CKD: results from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;65:267–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ku E, Xie D, Shlipak M, Hyre Anderson A, Chen J, Go AS, He J, Horwitz EJ, Rahman M, Ricardo AC, Sondheimer JH, Townsend RR, Hsu CY; CRIC Study Investigators . Change in measured gfr versus egfr and ckd outcomes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:2196–2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dobre M, Yang W, Pan Q, Appel L, Bellovich K, Chen J, Feldman H, Fischer MJ, Ham LL, Hostetter T, Jaar BG, Kallem RR, Rosas SE, Scialla JJ, Wolf M, Rahman M. Persistent high serum bicarbonate and the risk of heart failure in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD): a report from the Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e001599. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. He J, Shlipak M, Anderson A, Roy JA, Feldman HI, Kallem RR, Kanthety R, Kusek JW, Ojo A, Rahman M, Ricardo AC, Soliman EZ, Wolf M, Zhang X, Raj D, Hamm L. Risk factors for heart failure in patients with chronic kidney disease: the CRIC (Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort) Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e005336. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.005336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Inker LA, Schmid CH, Tighiouart H, Eckfeldt JH, Feldman HI, Greene T, Kusek JW, Manzi J, Van Lente F, Zhang YL, Coresh J, Levey AS. Estimating glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine and cystatin C. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:20–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Davis BR, Whelton PK. Benazepril plus amlodipine or hydrochlorothiazide for hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1148–1149; author reply 1149–1150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jamerson K, Weber MA, Bakris GL, Dahlof B, Pitt B, Shi V, Hester A, Gupte J, Gatlin M, Velazquez EJ. Benazepril plus amlodipine or hydrochlorothiazide for hypertension in high‐risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2417–2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wright JT Jr, Bakris G, Greene T, Agodoa LY, Appel LJ, Charleston J, Cheek D, Douglas‐Baltimore JG, Gassman J, Glassock R, Hebert L, Jamerson K, Lewis J, Phillips RA, Toto RD, Middleton JP, Rostand SG; African American Study of Kidney D, Hypertension Study G . Effect of blood pressure lowering and antihypertensive drug class on progression of hypertensive kidney disease: results from the AASK trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2421–2431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fried LF, Emanuele N, Zhang JH, Brophy M, Conner TA, Duckworth W, Leehey DJ, McCullough PA, O'Connor T, Palevsky PM, Reilly RF, Seliger SL, Warren SR, Watnick S, Peduzzi P, Guarino P. Combined angiotensin inhibition for the treatment of diabetic nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1892–1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mann JF, Schmieder RE, Dyal L, McQueen MJ, Schumacher H, Pogue J, Wang X, Probstfield JL, Avezum A, Cardona‐Munoz E, Dagenais GR, Diaz R, Fodor G, Maillon JM, Ryden L, Yu CM, Teo KK, Yusuf S. Effect of telmisartan on renal outcomes: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:1–10, w11–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mann JF, Schmieder RE, McQueen M, Dyal L, Schumacher H, Pogue J, Wang X, Maggioni A, Budaj A, Chaithiraphan S, Dickstein K, Keltai M, Metsarinne K, Oto A, Parkhomenko A, Piegas LS, Svendsen TL, Teo KK, Yusuf S. Renal outcomes with telmisartan, ramipril, or both, in people at high vascular risk (the ONTARGET study): a multicentre, randomised, double‐blind, controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:547–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Remuzzi G, Ruggenenti P, Perna A, Dimitrov BD, de Zeeuw D, Hille DA, Shahinfar S, Carides GW, Brenner BM. Continuum of renoprotection with losartan at all stages of type 2 diabetic nephropathy: a post hoc analysis of the RENAAL trial results. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:3117–3125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tobe SW, Clase CM, Gao P, McQueen M, Grosshennig A, Wang X, Teo KK, Yusuf S, Mann JF. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes with telmisartan, ramipril, or both in people at high renal risk: results from the ONTARGET and TRANSCEND studies. Circulation. 2011;123:1098–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tokmakova MP, Skali H, Kenchaiah S, Braunwald E, Rouleau JL, Packer M, Chertow GM, Moye LA, Pfeffer MA, Solomon SD. Chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular risk, and response to angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibition after myocardial infarction: the Survival And Ventricular Enlargement (SAVE) study. Circulation. 2004;110:3667–3673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Einhorn LM, Zhan M, Hsu VD, Walker LD, Moen MF, Seliger SL, Weir MR, Fink JC. The frequency of hyperkalemia and its significance in chronic kidney disease. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1156–1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Berger AK, Duval S, Manske C, Vazquez G, Barber C, Miller L, Luepker RV. Angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers in patients with congestive heart failure and chronic kidney disease. Am Heart J. 2007;153:1064–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Winkelmayer WC, Fischer MA, Schneeweiss S, Wang PS, Levin R, Avorn J. Underuse of ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers in elderly patients with diabetes. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46:1080–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Peng Y, Xia TL, Huang FY, Huang BT, Liu W, Chai H, Zhao ZG, Zhang C, Liao YB, Pu XB, Chen SJ, Li Q, Xu YN, Luo Y, Chen M, Huang DJ. Influence of renal insufficiency on the prescription of evidence‐based medicines in patients with coronary artery disease and its prognostic significance: a retrospective cohort study. Medicine. 2016;95:e2740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chang TI, Zheng Y, Montez‐Rath ME, Winkelmayer WC. Antihypertensive medication use in older patients transitioning from chronic kidney disease to end‐stage renal disease on dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11:1401–1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bakris GL, Pitt B, Weir MR, Freeman MW, Mayo MR, Garza D, Stasiv Y, Zawadzki R, Berman L, Bushinsky DA. Effect of patiromer on serum potassium level in patients with hyperkalemia and diabetic kidney disease: the AMETHYST‐DN randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314:151–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Weir MR, Bakris GL, Bushinsky DA, Mayo MR, Garza D, Stasiv Y, Wittes J, Christ‐Schmidt H, Berman L, Pitt B. Patiromer in patients with kidney disease and hyperkalemia receiving RAAS inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:211–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bakris GL. Current and future potassium binders. Nephrol News Issues. 2016;30(suppl):27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sarafidis PA, Georgianos PI, Bakris GL. Advances in treatment of hyperkalemia in chronic kidney disease. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2015;16:2205–2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tsujimoto T, Sugiyama T, Shapiro MF, Noda M, Kajio H. Risk of cardiovascular events in patients with diabetes mellitus on beta‐blockers. Hypertension. 2017;70:103–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Andersson C, Merie C, Jorgensen M, Gislason GH, Torp‐Pedersen C, Overgaard C, Kober L, Jensen PF, Hlatky MA. Association of beta‐blocker therapy with risks of adverse cardiovascular events and deaths in patients with ischemic heart disease undergoing noncardiac surgery: a Danish nationwide cohort study. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:336–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lindholm LH, Carlberg B, Samuelsson O. Should beta blockers remain first choice in the treatment of primary hypertension? A meta‐analysis. Lancet. 2005;366:1545–1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wiysonge CS, Bradley H, Mayosi BM, Maroney R, Mbewu A, Opie LH, Volmink J. Beta‐blockers for hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;1:CD002003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Badve SV, Roberts MA, Hawley CM, Cass A, Garg AX, Krum H, Tonkin A, Perkovic V. Effects of beta‐adrenergic antagonists in patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:1152–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Characteristics at First Visit in CRIC of Those Included for Analysis

Table S2. Sensitivity Analysis Using Adjusted* Cox Models That Account for Time‐Updated Proteinuria and Renal Function for Outcomes of Heart Failure and Death

Figure S1. Number of antihypertensive agents used by stage of CKD.