Abstract

Objective: Neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) has risen drastically over the past decade. Infants with NAS experience extreme discomfort and developmental delays when going into withdrawal. Management includes multiple supportive and nonpharmacologic therapies as first-line treatments in an effort to reduce or prevent the need for medication management. Acupuncture has demonstrated efficacy in adults experiencing withdrawal from addictions, as well as for treating many other conditions in pediatric patients who have similar symptoms to withdrawal. The purpose of this review is to evaluate the safety and efficacy of acupuncture for neonates in withdrawal.

Materials and Methods: This review was guided by the Arksey and O'Malley methodological framework, and analysis was performed based on a social ecological model. The PRISMA [Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses] statement was used to organize selected publications, and a flow chart was created to display the search process. PubMed, EMBASE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, and the Cochrane Databases were searched for relevant publications.

Results: Acupuncture appears to be safe and effective for reducing withdrawal symptoms in infants, and, thus, should be considered as an additional nonpharmacologic treatment option for NAS.

Keywords: neonatal acupuncture, infant acupuncture, infant acupressure, neonatal abstinence syndrome, opioid withdrawal, nonpharmacologic treatments

Introduction

Neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) is a condition in which infants go through withdrawal secondary to prenatal substance exposure. This condition causes many uncomfortable and painful symptoms that result from central nervous system hyperirritability and autonomic nervous system dysfunction, including tremors, hypertonicity, agitation, disrupted sleep, feeding difficulty, vomiting, diarrhea, temperature instability, tachypnea, and impaired weight gain.1–3 Over the past 15 years, the incidence of NAS has risen by 300%, now affecting 6 infants per 1000 live births in the United States.4–6 This trend has increased NAS-specific health care treatment costs specifically related to NAS by an estimated range of $190 million to $720 million.3

The current standard of care for NAS emphasizes nonpharmacologic interventions that modify the infant's environment to support neurodevelopmental and physiologic stability.1,3 These treatments include a combination of therapies, such as breastfeeding, rooming-in, positioning, swaddling, clustering care around feedings, rocking beds, and sound-makers as tolerated.3 However, these methods often fail to relieve the infant's symptoms. Pharmacologic treatments, such as morphine or methadone tapers, are administered in the neonatal intensive care setting, which are, in turn, associated with longer hospital stays, interruption of maternal bonding, and increased risk for negative developmental effects.1,7 Therefore, effective nonpharmacologic treatments are the preferred first line of therapy for infants with NAS and warrant further investigation.

Acupuncture has demonstrated effectiveness for treating addiction and pain in both adult and pediatric populations.8–15 Given this success, acupuncture may serve as an additional nonpharmacologic treatment for NAS, preventing or reducing the need further for pharmacologic management. Current evidence on neonatal acupuncture for treating NAS is limited; therefore, a scoping review was performed to investigate and summarize findings related to the efficacy and safety of acupuncture in the neonatal population to support further research on this treatment for NAS. This review was guided by the following question: “What is known from existing research about acupuncture in the neonatal population?”

Theoretical Framework

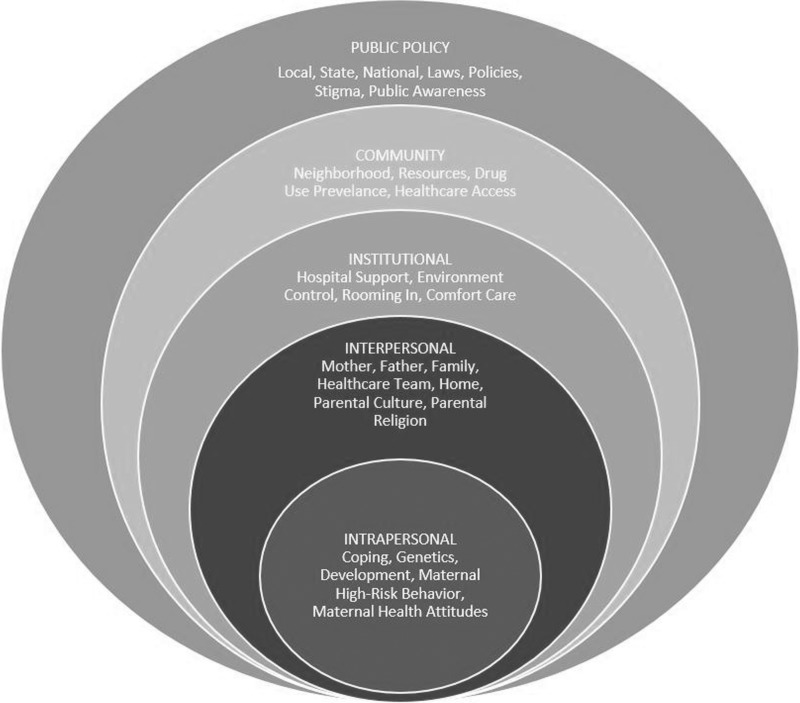

The social ecological model was used to guide this review to ensure a thorough assessment and description of the behavioral and environmental influences that affect NAS in order to support inclusion of effective, early health-promoting interventions such as acupuncture.16,17 Combined strategies targeting both the individual and the social environment are the most successful for attaining comprehensive health promotion. This framework accounts for the multisystem interactions contributing to behavioral outcomes and displays how incorporation of acupuncture may be integrated in the standard of care for NAS.18 Figure 1 presents these relationships on the five levels proposed by McLeroy and colleagues, which includes intrapersonal, interpersonal, institutional, community, and public policy.16

FIG. 1.

Social ecological model for neonatal abstinence syndrome management.

Intrapersonal factors include coping mechanisms, genetics, developmental history, maternal high-risk behavior, and maternal attitudes about health.18 A mother's high-risk behavior and health attitude affects her decision directly to consume opioids and continue usage throughout her pregnancy. This decision affects the developing infant directly, as the mother provides all nourishment, potentially exposing her fetus to harmful substances. The amount and type of substance consumption also influences the complexity of the withdrawal an infant might experience. For example, if a mother chooses to smoke cigarettes, consume alcohol, and take benzodiazepines in addition to opioids, the infant will experience a higher level of withdrawal.19 The infant's ability to handle withdrawal, is the combined result of genetics and developmental history. These collectively affect the infant's severity of opioid withdrawal in complex, interconnected ways.

Pharmacologic interventions might be administered to relieve severity symptoms associated with withdrawal and ideally improve the infant's comfort. However, these medications are associated with longer hospital stays, and there are no universal evidence-based pharmacologic treatment strategies.20 At this level, acupuncture may serve as an additional, first-line nonpharmacologic therapy to relieve symptoms of withdrawal by promoting parasympathetic activity and reducing the need for medication.2,21

The interpersonal level of the social ecological model comprises the social network of the baby.16 These individuals would include family members, friends, and the health care team that come into contact with the baby. Parental culture and religious affiliation also influence the infant's lifestyle and may serve to provide support and supplies. On the institutional level, the infant's care is centered around the mother–infant dyad, with a focus on maternal bonding and comfort care.1,16 Controlling the infant's environment by limiting stimulation is a priority when treating NAS. This includes soft music or sound machines, clustered care around feeding to reduce stimulation, and gentle touch. The healthcare team and medical center institutionally focus on this holistic care to maximize nonpharmacologic interventions fully that may be continued in the home after discharge from the hospital. Use of acupuncture could be included in this model of care and potentially serve as an additional therapy.

In the social ecological model community level, the baby's neighborhood, community resources, prevalence of drug abuse, and access to healthcare—in an interconnected fashion—all influence the mother's decisions whether to continue her high-risk behavior and/or utilize designated resources.17 Finally, public policy at the local, state, and national level affect the availability of assets and the direction of effective programs to treat substance dependence and prevent NAS.16 Social stigma associated with substance misuse, especially among mothers, is even more isolating and might prevent a mother from seeking appropriate medical care.22 Public awareness could bridge the healthcare gap by increasing social acceptance of this condition and by encouraging more mothers to obtain care.

Materials and Methods

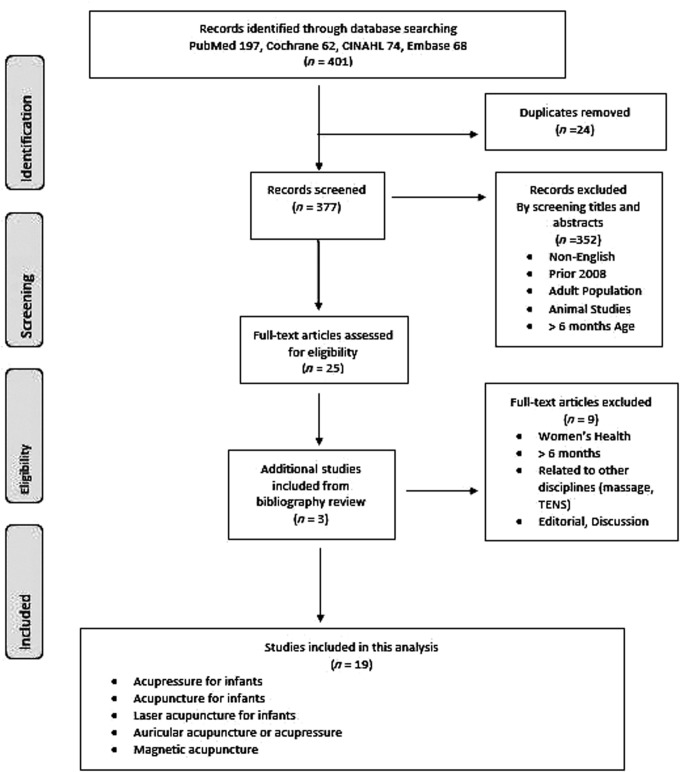

The Arksey and O'Malley methodological framework23 guided this scoping review with enhancements directed by Colquhoun et al.24 and Levac.25 The five-stage approach included identifying the research question, identifying relevant studies, selecting applicable studies, charting the data, and summarizing the results.23 A search strategy was developed and devised after consultation with a reference librarian in August 2018. The PRISMA [Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses] statement was used to organize selected publications, and a flow chart was created to display the search process (Fig. 2). PubMed, EMBASE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, and Cochrane Databases were searched for relevant publications.

FIG. 2.

The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram. CINAHL, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; TENS, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were developed and used to filter studies that pertained to the infant population; that were published in English over the past 10 years; and that included randomized, controlled, and pilot studies published in scholarly peer-reviewed journals. The reference lists of the retrieved documents were reviewed to seek additional primary sources and relevant publications. An initial search included all nonpharmacologic interventions for neonatal populations and yielded more than 2000 results. Therefore, the search methods were refined. A combination of the following search terms was used for each database: neonatal acupuncture, infant acupuncture, infant acupressure, neonatal abstinence syndrome, opioid withdrawal, and non-pharmacologic treatments.

The refined search initially led to the identification of 401 publications. After checking for duplicates, the total was reduced to 377 studies, which were each evaluated based upon the inclusion/exclusion criteria. After abstract reviews, 352 publications were excluded because they were not published in English within the last 10 years, did not pertain to the neonatal population, or were animal studies. The remaining 25 full-text studies were reviewed, and an additional 3 studies were included after review of the references. Of those 28 publications, 9 were excluded because they were related to other disciplines such as women's health or were editorials and/or were discussion articles. Finally, 19 studies were included in the study sample for analysis.

A data-charting matrix was developed to organize extracted data, as recommended by Arksey and O'Malley (Appendix 1).23 Recorded information was categorized into the following groups: author; date; purpose; sample; setting; design; methods; primary outcome variable(s); aim; use of theory; intervention; results; and recommended research. The social ecological model was utilized to describe findings (stage 4) and to synthesize results (stage 5) from the publications, with a focus on the five influential levels of health outlined by McLeroy and colleagues.16,23

Results

Nineteen studies were retained for this review and charted analytically (Appendix 1). Of these, 12 were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) performed in inpatient (n = 6) or outpatient settings. The trials were conducted in multiple countries, including China (n = 1), Austria (n = 1), the United States (n = 1), Taiwan (n = 1), Norway (n = 2), Turkey (n = 3), and Sweden (n = 3). Five trials were pilot studies conducted on inpatients in Wales (n = 1), the United States (n = 2), and Austria (n = 2). One was a case study of an inpatient in Austria. The remaining study did not report a formalized clinical trial structure and provided acupressure in addition to the standard of care in an inpatient setting in Iraq.26

Five of the included studies evaluated the use of acupuncture to relieve symptoms of withdrawal caused by intrauterine exposure to substances and 5 studies utilized acupuncture to reduce symptoms of colic. Four trials assessed the effect of acupuncture or acupressure on neonatal pain; and the remaining 5 trials focused on improving weight gain (n = 1), Apgar scores (n = 1), neurologic development in cerebral palsy (n = 1), and the safety of laser acupuncture (n = 2). Overall, the results of these studies supported the use of acupuncture for treating multiple conditions in the infants.2,12,21,26–41

The 12 RCTs had varying sample sizes ranging from 7 to 147 participants.2,12,21,27,29,30,33–36,39,40 Of these randomized studies, half were prospective.2,12,21,27,35,40 The primary aim of other studies varied but often included the safety (n = 5) and feasibility (n = 4) of utilizing acupuncture as a treatment modality.26,28,32,37,39,41 Researchers in the studies also assessed the effect of acupuncture on withdrawal symptoms (n = 5), colic (n = 5), or pain (n = 4), neural development (n = 1), Apgar scores (n = 1), and weight gain (n = 1).2,12,21,26–31,33–36,38–41

Primary outcome variables assessed in the studies included duration of crying (n = 7), analgesic use (n = 6), symptoms of withdrawal (n = 5), vital signs (n = 5), pain scores (n = 4), presence of colicky crying (n = 4), pain scores (n = 4), hospital lengths of stay (n = 3), feedings (n = 3), durations of procedures (n = 2), Apgar scores (n = 2), thermographic skin measures (n = 2), behavioral states during the procedures (n = 1), weight (n = 1), stooling patterns (n = 1), gross motor function (n = 1), mental development (n = 1), psychomotor development (n = 1), cranial imaging (n = 1), and electroencephalogram (n = 1). Any adverse events were evaluated and/or reported in most of the studies (n = 16).

Several types of acupuncture were used in these studies. Needle acupuncture (n = 8) was most commonly used, followed by laser acupuncture (n = 5), acupressure (n = 4), magnetic acupuncture (n = 1), and a combination of needle and acupressure techniques (n = 1). The majority of the studies utilized full-body acupuncture sites (n = 13), 4 studies utilized a combination of auricular and body points (n = 4), and the remaining 2 studies applied auricular therapy alone.

Social Ecological Model

None of the studies discussed use of theory in their designs or analyses. A level of influence was included in all of the studies (Fig. 1). Intrapersonal factors were present in all 16 of the studies. The safety of acupuncture was also addressed on the intrapersonal level in all of the studies (n = 16). The majority of the studies concurrently included intrapersonal, interpersonal, and institutional influences (n = 9).

Intrapersonal Influences

The intrapersonal level of the social ecological model is the most basic aspect of the individual and includes developmental history.16 When considering the use of acupuncture as a potential adjunct treatment, safety and any potential negative effects must be considered. The majority of the studies (n = 14) incorporated intrapersonal characteristics by discussing targeted interventions focused on comfort care and coping for the treatment of pain, colic, or withdrawal.2,12,21,27,28,30,31,33–35,38–41 All of the studies outlined the safety of acupuncture in the neonatal population.2,12,21,26–41 The aim of 5 of these studies was to evaluate the safety of acupuncture in the neonatal population.26,28,32,37,41 No adverse events were reported in any study, and all of the studies supported further research on acupuncture due to proven safety. Several of the studies reported specific therapeutic benefits of acupuncture, such as better sleep (n = 1), improved weight gain and feeding (n = 2), reduced pain or need for rescue medications (n = 3), and less crying (n = 3).21,28–31,33–35,38

Interpersonal Influences

For neonates with NAS, family members, friends, and healthcare providers are the only social contacts, thus encompassing the social relationship as outlined by McLeroy, et al.16 Most of the interventions outlined the standard of care for hospitalized infants and fostered the mother–infant dyad. Swaddling, rooming-in, kangaroo care, parental involvement with care, breastfeeding, and holding were continued as part of the standard of care.2,12,21,26,28,29,31–36,38,41 Four of the studies utilized acupressure, which could feasibly be included in the standard of care as an additional adjunct and would not disrupt maternal bonding, as acupressure could be applied to the ear with continued nonpharmacologic interventions.2,12,26,29

Institutional Influences

In treating sick infants, 10 of the studies outlined the need for environmental controls, which have become the standard of care.3 Medical centers providing care to this population have created supportive rooms that are private, as opposed to the historical community nursery setting, thus allowing for more direct support of the infant's individual needs. This supports the use of incubators, sound-makers, reduced stimuli, and clustering of care to allow for longer resting intervals.2,12,21,26,28–32,36,41 Such modifications to the baby's environment support neurodevelopmental and physiologic stability.3,42

Five of the studies concluded that the use of acupuncture is a feasible intervention in the neonatal population as part of the standard of care.2,21,28,30,41 Of these 5 studies, 3 assessed the use of acupuncture to treat NAS.2,21,41 Three of the studies added that acupuncture was well-accepted by parents, providers, and staff members implementing care.21,31,41 Golianu and colleagues surveyed the nurses and providers caring for the infants who were weaning off of medications and reported a consensus among these caregivers that acupuncture was helpful in reducing medications.31 Schwartz, et al. reported a 96% successful recruitment and maternal support of their study utilizing acupressure to relieve symptoms of NAS.2

Discussion

The most prominent finding from this scoping review is that use of acupuncture is safe for infants.2,12,21,26–41 The social ecological model demonstrated that acupuncture may be incorporated into the standard of care for NAS as acupuncture may be administered to the infant's ear and/or be part of clustered care in order not to disrupt swaddling, kangaroo care, or breastfeeding. Further practicality was supported by reports of acupuncture acceptance among families as well as institutions. All reported benefits in these studies targeted specific symptoms of opioid withdrawal, including feeding difficulties, disrupted sleep, pain, and agitation. These findings supported the use of acupuncture as a potential intervention to treat NAS.2,12,21,26–31,33–41 All of the investigators recommended additional research to evaluate the efficacy of acupuncture further, and collectively agreed that acupuncture is safe, feasible, and may be implemented in the neonatal population. These results support further research to evaluate the use of acupuncture for the treatment of NAS.

Gaps in the Literature

The use of acupuncture in the neonatal population has been studied and deemed to be safe; however, the researchers involved in these existing studies recommended further analyses of efficacy (n = 13). With respect to acupuncture for treating NAS, few studies resulted in implementation, and only justification for feasibility and safety had been achieved (n = 5). Multiple methods and sites are also discussed in the literature with no indication regarding which technique would be optimal as a treatment intervention. The overall consensus from these studies is that the researchers recommended higher sample sizes, as well as prospective, RCTs with blinding to evaluate the efficacy of a standardized protocol using acupuncture for treating infant medical conditions.

Limitations

This scoping review provided a large overview of acupuncture in the infant population. The search was limited to English-language publications within the last 10 years. Inclusion of non–English-language databases might have provided further studies for analysis. Therefore, some relevant studies might have been excluded. A second reviewer was not included in the search process despite recommendations by Arksey and O'Malley.24

Conclusions

Acupuncture may be a noninvasive, acceptable, and feasible intervention for the neonatal population. Given the safety of acupuncture and positive outcomes in treating adult and pediatric populations, further research should be conducted examining the efficacy of acupuncture for treating NAS. Exploratory results of pilot studies with neonatal populations indicate that acupuncture could reduce opioid-withdrawal symptoms, reduce length of hospital stays, and, subsequently, reduce healthcare costs associated with treating NAS. Many opportunities exist to study the use of acupuncture for multiple medical conditions in neonatal medicine. Higher-quality RCTs should be performed to assess the safe use of acupuncture as an effective intervention. Additionally, comparisons of acupuncture techniques, sites, timing, and applications should be made to assess the greatest effects and feasibility.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Camille Ivey the Health Sciences Informationist, Vanderbilt University's Annette and Irwin Eskind Family Biomedical Library and Learning Center.

Appendix Table A1.

NAS Scoping Analysis

| Source (1st author, year & reference) | Design | Aim | Type of acupuncture | Setting/sample | Variables & data collection | Social ecological Model levels | Findings | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbasoğlu, 201512 | Prospective RCT; N = 32 | Effect of acupressure at Kun Lun (UB 60) & Taixi (K 3) points for pain management in preterm infants prior to heel lancing | Acupressure applied for 3 min prior to heel stick; n = 16 received acupuncture | Infants 28–36 wks old, in NICU of Baskent University Hospital in Turkey | Video; PIPP; gestational age; behavioral state; HR, O2 saturation; BP; & durations of crying & procedure | Intrapersonal, interpersonal & institutional | No significant difference in PIPP (pain) score; shorter mean duration of procedure & crying in acupressure group (p = 0.001); quick, safe, nonpharmacologic treatment for reducing pain in newborns | Need for more extensive research on different acupoints |

| Abbasoğlu, 201527 | Prospective RCT; N = 42 | Effect of laser acupuncture at Yintang point before heel lancing for pain management in newborns | Laser acupuncture 2 min before heel lance | Healthy infants 37–42 wks old, in Baskent University Hospital in Turkey | Video; NIPS; & durations of crying & procedure | Intrapersonal | Shorter mean procedure time but longer mean crying time; sucrose intervention group had lower mean pain score (NIPS) | Further research to evaluate efficacy of laser acupuncture modes/doses for pain management in newborns |

| Ahmad, 200926 | Standard medical management of infants born after emergency cesarean section with acupressure added; N = 50 | Increase Apgar scores via acupressure; evaluate feasibility with standard of care; & adverse events | Acupressure; manual stimulation of K 1 & LU 11 | Newborn infants (gestational age not reported) in Iraq | Apgar scores at 1, 5 & 10 min | Intrapersonal, interpersonal & institutional | 84% improved Apgar scores with acupressure & 16% had no improvement | Acupressure was feasible, without risk to infants & did not interfere with standard of care |

| Chen, 201728 | Single-blinded, placebo-controlled pilot RCT; N = 42 | Safety & feasibility of auricular noninvasive magnetic acupuncture to decrease infant pain during heel pricks | Auricular magnetic acupuncture; Battlefield Acupuncture protocol | Mean gestational age: 34.1, in NICU of Royal Hospital for Women in New South Wales, Australia | PIPP pain score, HR, SpO2 saturation, analgesic use | Intrapersonal, interpersonal & institutional | No adverse events; safe, feasible; no difference in PIPP pain scores before & after; mean PIPP scores during heel prick significantly lower (P = 0.04); no differences in HR, SpO2, or analgesic use | Further studies on the effect of magnetic acupuncture for newborn conditions causing stress or pain are warranted |

| Chen, L., et. al. 200829 | Double blinded RCT; N = 40 | Body weight gain via combined acupressure & meridian massage in premature infants | Acupressure + massage; 3 × per d for 15 min × 10 d; RN 12, ST 36, KI 1 | < 34 wks old preterm infants in China Medical University Hospital in Central Taiwan | Daily weight in g × 14 d; length of hospital stays; Apgar scores; volumes of milk & types of milk ingested | Interpersonal & institutional | No difference in volume of milk ingested; experimental group had higher daily weight gain; consistent with previous studies, acupressure & meridian massage had a significant effect on body weight in premature infants | Further validation of acupressure & meridian massage with extensive experimentation & investigation of other acupoints & meridians to assess effect on preterm infants |

| Ecevit, 201130 | RCT with crossover; N = 10 | Effects of acupuncture on preterm neonates during minor painful procedures | Needle acupuncture; Yintang (Ex-HN 3) × 30 min | Mean gestational age: 29.9 wks in NICU of Baskent University Hospital in Turkey | NIPS pain score, crying time, O2 saturation, HR, respirations & BP | Intrapersonal & institutional | Decreased HR after needle application (P < 0.05); no changes in O2 saturation, BP, or respiratory rate; NIPS & crying duration were lower (P = 0.00); no crying during needle insertion; safe, effective & economical intervention | Further studies to evaluate efficacy of needle acupuncture for painful procedures |

| Golianu, 201431 | Pilot study; N = 10 | If acupuncture was beneficial & led to reduction in symptoms of agitation & withdrawal | Needle acupuncture + acupressure; NADA protocol + body points Yintang, ST 36, PC 6 × 15 min daily × 5 d on alternate ears + acupressure beads × 24 hrs | Age range: 5 wks old to 7 mo; in NICU of Stanford University in CA, USA | WAT-1; mg of morphine & benzodiazepines administered & # of rescue doses: bedside RN & MD survey | Intrapersonal, interpersonal & institutional | Acupuncture well-tolerated; mild skin abrasion with seed placement in 1 case that resolved in 24 hrs; By 24 hrs post treatment, 100% had reductions in opioid medications & 89% had reduced rescue doses after 48 hrs of treatments; survey of RN & MD providers showed that they felt acupuncture was helpful for reducing medications | Larger studies needed to evaluate statistical merit of these findings, including prospective RCTS & dose–response studies |

| Kurath-Koller, 201532 | Pilot; N = 20 | Thermal changes in skin temperatures in neonates during laser acupuncture & safety of laser acupuncture | Laser acupuncture × 5 min, rest for 10 min, then laser acupuncture again × 10 min | > 35 wks gestational age of inpatients in Graz, Austria | 360 thermographic measurements on bilateral hands, HR, O2 saturation, end-expiratory CO2 & breathing movements | Intrapersonal, interpersonal & institutional | No patient distress or discomfort; maximum temperatures 38.7°C on left hand & 38.3°C on right hand | Laser acupuncture did not cause skin irritation or adverse events in newborn infants, suggesting the treatment is safe; warming of neonate skin should be treated with caution & further studies should assess short & long-term effects |

| Landgren, 201034 | Blinded, clinical RCT, N = 81; 6 biweekly clinic visits | Whether acupuncture reduces duration & intensity of crying in infants with colic | Needle acupuncture LI 4 for 2 sec | > 36 wks old & 2–8 wks old in acupuncture clinic in Sweden | Fussing, crying, CC; total duration of fussing, crying & CC | Intrapersonal & interpersonal | Difference in total crying among groups (P = 0.034); shorter duration of fussing during the 1st & 2nd intervention wks; shorter duration of CC during the 2nd intervention week; & no serious side-effects | Future research needed to validate results & investigate efficacy of other acupuncture points & modes of stimulation for treating infantile colic |

| Landgren, 201135 | Prospective, blinded clinical RCT; N = 81; 6 biweekly clinic visits | Describe feeding & stooling patterns of infants with colic & evaluate influence of minimal acupuncture | Needle acupuncture LI 4 for 2 sec | > 36 wks old & 2–8 wks old at acupuncture clinic in Sweden | Parental diaries of infant crying, feeding & stooling | Intrapersonal & interpersonal | No differences in frequency or duration of meals; no significant differences in frequency of stools; sleep was improved in the acupuncture group (P = 0.006). | Further studies to clarify the mechanism of acupuncture in colic |

| Landgren, 201733 | Multicenter, single-blinded 3-armed RCT; N = 147; biweekly for 2 wks | Evaluate & compare effects of two types of acupuncture in infants with colic in public child-health centers | Needle acupuncture LI 4 & individualized acupuncture, compared to untreated group | ≥ 37 wks old in health centers in Sweden | Difference in mean values of total crying time or sum of time spent fussing, crying, & CC; adverse events | Intrapersonal & interpersonal | Effects of two types of acupuncture were similar & reduced time spent crying or CC (P = 0.05) & (P = 0.031); no serious adverse events reported; of 388 treatments, on 200 occasions, infants did not cry at all during acupuncture | Future studies should include larger sample sizes, infants with a cow's milk–free diet & further research to find optimal needling locations, stimulation, & treatment intervals |

| Liu, 201636 | RCT; N = 64 | If intelligence seven needle therapy administered in infants with perinatal brain damage syndrome would improve neural development | Needle acupuncture; 9–11 am every other day × 30 min, for 15 d; Shenting (GV 24), Benshen (GB 13) & Sishencong (EX-HN 1) | 4–5 mo old in Cerebral Palsy Rehabilitation Center of Nanhai Maternity and Children Hospital Affiliated with Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine in China | GMFM, MDI, & PDI; TCD ultrasound & CT, or MRI imaging; side-effects or complications | Intrapersonal, interpersonal & institutional | MDI scores were improved in the acupuncture group (P < 0.05) but no significant differences in the PDI scores; social adaptation was improved in acupuncture group (P < 0.01) as well as GMFM, linguistic & social intercourse (P < 0.05); no discrepancy in fine movement; acupuncture group showed greater recovery rate (P < 0.05); no complications. | Intelligence seven needle therapy might improve brain blood supply & promote growth of frontal & parietal lobes |

| Raith, 201438 | Case study; N = 1 | Efficacy of laser acupuncture on withdrawal symptoms of infant diagnosed with NAS | Laser acupuncture 1 hr after morphine administration; NADA protocol + body acupuncture LR 3, L I4, KI3, & HT 7; & 30 sec auricular points & 60 sec body points | 39.3 wks gestational age; inpatient in hospital in Austria | Finnegan score; morphine administration & volume of feeds | Intrapersonal & interpersonal | Improved feeding following laser acupuncture, reduced Finnegan scores 1 d after laser acupuncture, improved sleep, & RN report of increased relaxed state after acupuncture; & no adverse events or distress | Laser acupuncture may be used as a noninvasive therapeutic intervention; further studies should be conducted with increased number of cases to obtain statistically powerful results |

| Raith, 201521 | Prospective, blinded single-center RCT; N = 28 | If a combination of laser acupuncture & pharmacologic therapy reduces duration of therapy in newborns diagnosed with NAS, compared to pharmacologic therapy alone | Laser acupuncture; 5 ear points (NADA protocol) × 30 sec +4 body points: LR 3, LI 4, Taixi, & Shen Men × 60 sec daily | NICU of University Hospital of Graz in Graz, Austria | Finnegan score 3 × per day, morphine doses & durations, lengths of hospital stay | Intrapersonal, interpersonal & institutional | Duration of morphine therapy was reduced (28 d vs. 39 d; P = 0.019) & reduced length of stay (35 d vs 50 d; P = 0.048); laser acupuncture was safe, feasible, efficient & well-accepted by parents | Laser acupuncture could be used as an adjunct in a multimodal therapy program to treat neonates with NAS |

| Raith, 201237 | Pilot study; N = 10 | If laser acupuncture significantly changes surface temperature, thus, representing a potential risk of application | Laser acupuncture; bilateral arms at LI 4 point (Hegu) × 5 min, rest 10 min, then again × 10 min | 31.5 wks gestational age; inpatients prior to hospital discharge in Division of Neonatology, Graz University Clinic in Graz, Austria | Thermography of bilateral hands before laser acupuncture applied, 1 min, 5 min & 10 min after laser acupuncture; HR, O2 saturation, end-expiratory CO2, EEG, & respiratory movements | Intrapersonal | No changes in HR, O2, CO2, EEG, or breathing movements; skin temperature rose to a maximum of 37.9°C; no adverse effects on skin | Laser acupuncture does not appear to confer any risks; further question to be answered: “Is sympathetic activity related to acupuncture?” |

| Schwartz, 20112 | > 4 yr randomized, prospective, unblinded study; N = 76 | If auricular acupressure augmentation of standard medical management decreased hospital lengths of stay for NAS care or improved infant comfort | Auricular acupressure & NADA protocol: Lung, Shenmen, Sympathetic. Rotating ears; RNs massaged 30–60 sec after NAS scoring; rotated ears every 24–48 hrs; n = 39 acupressure | > 37 wks old in inpatient pediatric service of Boston, MA, USA | Hospital length of stay, Finnegan scores, & total amount of pharmacologic support; skin irritation | Intrapersonal, interpersonal & institutional | No skin irritations; no significant differences in lengths of stay or pharmacologic management; demonstrated safety & feasibility of acupressure in a vulnerable population; maternal compliance & 96% successful recruitment; & well-received by mothers | Framework provided for future prospective studies to determine efficacy of acupuncture-based therapies |

| Skjeie, 201139 | Open, single-blinded RCT; N = 7 | Feasibility of a proposed design of an acupuncture trial to relieve symptoms of infantile colic | Needle acupuncture; ST 36 bilaterally × 30 sec × 3 consecutive d; n = 4 in intervention group | > 36 wks old at GP outpatient office in Norway | Number of hrs crying in 24-hr period per parental report in an interview | Intrapersonal | No significant findings statistical findings; no adverse events. | Development of a standardized protocol with larger, blinded RCT |

| Skjeie, 201340 | Prospective, blinding- validated multicenter RCT; N = 90 | Hypothesis that acupuncture treatment has a clinically relevant effect on infantile colic | Needle acupuncture × 30 sec × 3 consecutive d at ST 36 | > 39 wks old; GP outpatient clinic in southern Norway | Crying time in min & hrs; Wessel's infantile colic criteria; parental assessment; adverse events | Intrapersonal | No significant changes in crying time; mean difference of 13 min in acupuncture group; reduction in Wessel's criteria in the acupuncture group on d 33 (P = 0.034); no adverse effects | Acupuncture for infantile colic should be restricted to clinical trials |

| Weathers, 201541 | Pilot study; N = 20 | Auricular acupuncture safety, feasibility, & acceptability as a nonpharmacologic adjunct in NAS | Needle auricular acupuncture & NADA protocol + Frustration, R-Point, & Psychovegetative rim; needles in place in 1 ear × 3 ± 1 d then rotated to opposite ear until methadone discontinued or discharge dose established | ≥ 37 wks old, diagnosed with NAS requiring pharmacologic treatment in NICU of University of South Florida & Tampa General Hospital, in Tampa, FL, USA | Finnegan score, skin breakdown was assessed twice per day, pharmacologic treatment (drug, duration, peak dose, total dose, & discharge dose), auricular acupuncture details, growth data, parental survey pre & post | Intrapersonal, interpersonal & institutional | No skin breakdown or cellulitis; 2% of needles were dislodged & replaced by PI; 1 event reported to IRB, needles were in place & infant underwent MRI; no apparent adverse events; parents & providers had increased acceptability of auricular acupuncture after study; safe, feasible & accepted by parents & providers | Auricular acupuncture using NADA points may be a potentially effective nonpharmacologic adjunct to standard of care; future research is needed to evaluate the effect of auricular acupuncture on specific outcome measures in infants with NAS |

NAS, neonatal abstinence syndrome; RCT, randomized controlled trial; min, minute(s); wks, week(s); NICU, neonatal intensive care unit; PIPP, Premature Infant Pain Profile; HR, heart rate; BP, blood pressure; NIPS, neonatal infant pain; SpO2, blood oxygen saturation; d, day(s); RN, registered nurse; mo, month(s); NADA, National Acupuncture Detoxification Association; WAT-1; withdrawal assessment tool–1; MD, medical doctor; sec, second(s); GMFM, gross motor function measure; MDI, mental development index; PDI, psychomotor development index; TCD, transcranial Doppler; CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; hr, hour; yr, year; EEG, electroencephalogram; GP, general practice; PI, principal investigator; IRB, institutional review board.

To receive CME credit, you must complete the quizonline at: www.medicalacupuncture.org/cme

CME Quiz Questions

Article learning objectives: After studying this article, participants should be able to summarize the scientific evidence for the role of acupuncture as a therapeutic intervention in neonatal abstinence syndrome; describe current standard of care for NAS and the medical issues concerning effectiveness and safety of this current standard; and describe neonatal abstinence syndrome and explain the potential role and value of a non-pharmacologic intervention such as acupuncture.

Publication date: March 22, 2019

Expiration date: April 30, 2020

Disclosure Information:

Authors have nothing to disclose.

Richard C. Niemtzow, MD, PhD, MPH, Editor-in-Chief, has nothing to disclose.

Questions:

-

1.

Identify the incorrect statement:

-

a.

Neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) is a condition in which neonates experience withdrawal secondary to prenatal substance exposure.

-

b.

Symptoms of NAS include hyperirritability of the central nervous system such as tremors, hypertonicity, and insomnia.

-

c.

Symptoms of NAS include those of autonomic nervous system dysfunction such as feeding difficulty, vomiting, diarrhea, and tachypnea.

-

d.

Other symptoms typical of NAS are bradycardia and somnolence.

-

e.

The incidence of NAS in the United States has risen sharply over the last 15 years, representing a growing and important problem in neonatal care.

-

a.

-

2.

Identify the incorrect statement:

-

a.

Current standard of care for NAS emphasizes non-pharmacologic interventions such as swaddling, rooming in, and clustering care around feedings.

-

b.

Pharmacologic treatment consists of morphine and methadone tapers administered in the neonatal intensive care setting.

-

c.

Narcotic tapers in the neonatal intensive care setting have been demonstrated to shorten hospital stays, promote maternal bonding, and decrease the risk for developmental delays.

-

d.

Standard of care non-pharmacologic interventions often fail to relieve the neonate's symptoms.

-

e.

The authors make the case that the failure of current non-pharmacologic interventions to relieve symptoms and the association of narcotic tapers with longer hospital stays and developmental delays mandates further research into effective non-pharmacologic therapies for NAS.

-

a.

-

3.

Identify the incorrect statement:

-

a.

Acupuncture has demonstrated effectiveness in treating addiction and pain in the adult and pediatric population.

-

b.

Current evidence on treatment of NAS with acupuncture is strongly supportive of immediate institution of this therapeutic intervention.

-

c.

Current evidence on acupuncture for NAS is limited.

-

d.

The authors performed a scoping review to investigate and summarize findings about the safety and effectiveness of acupuncture in the neonatal population to support further research in the treatment of NAS.

-

e.

The scoping review was guided by the question: “What is known from existing research about acupuncture in the neonatal population?”

-

a.

-

4.

Identify the incorrect statement:

-

a.

The authors scoping review was limited to English language studies from the last 10 years.

-

b.

The studies analyzed used various types of acupuncture including needle acupuncture, laser, acupressure, and magnetic device.

-

c.

No adverse events were reported in any study.

-

d.

All of the studies outlined the safety of acupuncture in the neonatal population.

-

e.

The authors concluded that safety concerns argued against further acupuncture studies in this population.

-

a.

-

5.

Identify the incorrect statement:

-

a.

Several studies demonstrated that acupressure could feasibly be included in the standard of care as an adjunct that would not disrupt maternal bonding.

-

b.

Five of the studies concluded that acupuncture is a feasible intervention in the standard of care for NAS.

-

c.

Several studies reported that acupuncture was well accepted by parents, providers, and staff implementing care.

-

d.

The most prominent finding from this scoping review is that acupuncture is safe for infants.

-

e.

The authors noted that many different acupuncture and related methods had been used in the studies analyzed. However, they did not consider the absence of studies looking at optimal treatment intervention as a gap in this body of scientific literature.

-

a.

Continuing Medical Education – Journal Based CME Objectives:

Articles in Medical Acupuncture will focus on acupuncture research through controlled studies (comparative effectiveness or randomized trials); provide systematic reviews and meta-analysis of existing systematic reviews of acupuncture research and provide basic education on how to perform various types and styles of acupuncture. Participants in this journal-based CME activity should be able to demonstrate increased understanding of the material specific to the article featured and be able to apply relevant information to clinical practice.

CME Credit

You may earn CME credit by reading the CME-designated article in this issue of Medical Acupuncture and taking the quiz online. A score of 75% is required to receive CME credit. To complete the CME quiz online, go to http://www.medicalacupuncture.org/cme – AAMA members will need to login to their member account. Non-members have the opportunity to participate for a small fee.

Accreditation: The American Academy of Medical Acupuncture is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME).

Designation: The AAMA designates this journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exists.

References

- 1. Boucher AM. Nonopioid management of neonatal abstinence syndrome. Adv Neonatal Care 2017;17(2):84–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schwartz L, Xiao R, Brown E, Sommers E. Auricular acupressure augmentation of standard medical management of the neonatal narcotic abstinence syndrome. Med Acupunct. 2011;23(3):175–186 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Edwards L, Brown LF. Nonpharmacologic management of neonatal abstinence syndrome: An integrative review. Neonatal Netw. 2016;35(5):305–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Patrick SW, Schumacher RE, Benneyworth BD, Krans EE, McAllister JM, Davis MM. Neonatal abstinence syndrome and associated health care expenditures: United States, 2000–2009. JAMA. 2012;307(18):1934–1940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ko JY, Patrick SW, Tong VT, Patel R, Lind JN, Barfield WD. Incidence of neonatal abstinence syndrome—28 states, 1999–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(31):799–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Patrick SW, Davis MM, Lehmann CU, Cooper WO. Increasing incidence and geographic distribution of neonatal abstinence syndrome: United States 2009 to 2012. J Perinatol. 2015;35(8):650–655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu A, Björkman T, Stewart C, Nanan R. Pharmacological treatment of neonatal opiate withdrawal: Between the devil and the deep blue sea. Int J Pediatr. 2011;2011:935631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhang AL, Di YM, Worsnop C, May BH, Xue CC. Ear acupressure for smoking cessation: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;20(4):290–294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yeh ML, Wang PL, Lin JG, Chung ML. The effects and measures of auricular acupressure and interactive multimedia for smoking cessation in college students. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014;2014:898431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ma E, Chan T, Zhang O, et al. Effectiveness of acupuncture for smoking cessation in a Chinese population. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2015;27(2):NP2610–NP2622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. National Acupuncture Detoxification Association (NADA). Acupuncture Detoxification Specialist Training and Resource Manual, 4th ed. Laramie, WY: NADA Literature Clearing House; 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Abbasoğlu A, Cabıoğlu MT, Tuğcu AU, İnce DA, Tekindal MA, Ecevit A, Tarcan A. Acupressure at BL60 and K3 points before heel lancing in preterm infants. Explore (NY). 2015;11(5):363–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nager AL, Kobylecka M, Pham PK, Johnson L, Gold JI. Effects of acupuncture on pain and inflammation in pediatric emergency department patients with acute appendicitis: A pilot study. J Altern Complement Med. 2015;21(5):269–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tsai SL, Reynoso E, Shin DW, Tsung JW. Acupuncture as a nonpharmacologic treatment for pain in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2018;September 21:e-pub ahead of print [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yang C, Hao Z, Zhang LL, Guo Q. Efficacy and safety of acupuncture in children: An overview of systematic reviews. Pediatr Res. 2015;78(2):112–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(4):351–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stokols D. Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. Am J Health Promot. 1996;10(4):282–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brofenbrenner U. The Ecological Models of Human Development, vol 3, 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Elsevier; 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kocherlakota P. Neonatal abstinence syndrome. Pediatrics. 2014;134(2):e547–e561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Davis JM, Shenberger J, Terrin N, et al. Comparison of safety and efficacy of methadone vs morphine for treatment of neonatal abstinence syndrome: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(8):741–748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Raith W, Schmölzer GM, Resch B, Reiterer F, Avian A, Koestenberger M, Urlesberger B. Laser acupuncture for neonatal abstinence syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2015;136(5):876–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sutter MB, Gopman S, Leeman L. Patient-centered care to address barriers for pregnant women with opioid dependence. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2017;44(1):95–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–31 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O'Brien K, et al. Scoping reviews: Time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(12):1291–1294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Levac D, Colquhoun HL, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementat Sci. 2010;5(1):69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ahmad L, Courtney T. 100 Babies and two incubators: Using acupressure to increase the Apgar score in newborns experiencing respiratory distress in war-torn Iraq. Am Acupuncturist. 2009;49:30–31 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Abbasoğlu A, Cabioğlu MT, Tuğcu AU, Yapakci E, Tekindal MA, Tarcan A. Laser acupuncture before heel lancing for pain management in healthy term newborns: A randomised controlled trial. Acupuncture Med. 2015;33(6):445–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen KL, Lindrea KB, Quah-Smith I, Schmölzer GM, Daly M, Schindler T, Oei JL. Magnetic noninvasive acupuncture for infant comfort (MAGNIFIC)—a single-blinded randomised controlled pilot trial. Acta Paediatr. 2017;106(11):1780–1786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chen LL, Su YC, Su CH, Lin HC, Kuo HW. Acupressure and meridian massage: Combined effects on increasing body weight in premature infants. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17(9):1174–1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ecevit A, Ince DA, Tarcan A, Cabioglu MT, Kurt A. Acupuncture in preterm babies during minor painful procedures. J Tradit Chin Med. 2011;31(4):308–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Golianu B, Seybold J, Almgren C. Acupuncture helps reduce need for sedative medications in neonates and infants undergoing treament in the intensive care unit: Prospective case series. Med Acupunct. 2014;26(5):279–285 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kurath-Koller S, Litscher G, Gross A, Freidi T, Koestenberger M, Urlesberger B, Raith W. Changes of locoregional skin temperature in neonates undergoing laser needle acupuncture at the acupuncture point Large Intestine 4. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:571857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Landgren K, Hallstrom I. Effect of minimal acupuncture for infantile colic: A multicentre, three-armed, single-blind, randomised controlled trial (ACU-COL). Acupunct Med. 2017;35(3):171–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Landgren K, Kvorning N, Hallstrom I. Acupuncture reduces crying in infants with infantile colic: A randomised, controlled, blind clinical study. Acupunct Med. 2010;28(4):174–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Landgren K, Kvorning N, Hallstrom I. Feeding, stooling and sleeping patterns in infants with colic—a randomized controlled trial of minimal acupuncture. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2011;11:93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liu ZH, Li YR, Lu YL, Chen JK. Clinical research on intelligence seven needle therapy treated infants with brain damage syndrome. Chin J Integr Med. 2016;22(6):451–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Raith W, Litscher G, Sapetschnig I, Bauchinger S, Ziehenberger E, Müller W, Urlesburger. Thermographical measuring of the skin temperature using laser needle acupuncture in preterm neonates. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:614210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Raith W, Urlesberger B. Laser acupuncture as an adjuvant therapy for a neonate with neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) due to maternal substitution therapy: Additional value of acupuncture. Acupunct Med. 2014;32(6):523–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Skjeie H, Skonnord T, Fetveit A, Brekke M. A pilot study of ST36 acupuncture for infantile colic. Acupunct Med. 2011;29(2):103–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Skjeie H, Skonnord T, Fetveit A, Brekke M. Acupuncture for infantile colic: A blinding-validated, randomized controlled multicentre trial in general practice. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2013;31(4):190–196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Weathers L, Driver K, Zaritt J, et al. Safety, acceptability, and feasibility of auricular acupuncture in neonatal abstinence syndrome: A pilot study. Med Acupunct. 2015;27(6):453–460 [Google Scholar]

- 42. Maguire D. Care of the infant with neonatal abstinence syndrome: Strength of the evidence. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2014;28(3):204–211 ;quiz E203–E204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]