Significance

Viral infection drives microbial mortality and nutrient recycling in many ecosystems. Despite the importance of this process, little is known about how viruses obtain the resources they need to produce progeny. Here, we assess the balance between 2 basic sources of nutrients: the biomass of the infected host cell and the extracellular environment. Using an ecologically relevant marine phage–host system, we show that the phage uses the host cell’s nutrient uptake and biosynthetic machinery to acquire N from the extracellular environment and incorporate it specifically into viral proteins. We also show that certain host proteins continue to be produced during infection, suggesting specific roles in viral production or host defense. Our findings illustrate virus-driven nutrient flow in marine ecosystems.

Keywords: biogeochemistry, proteomics, bacteriophage

Abstract

The building blocks of a virus derived from de novo biosynthesis during infection and/or catabolism of preexisting host cell biomass, and the relative contribution of these 2 sources has important consequences for understanding viral biogeochemistry. We determined the uptake of extracellular nitrogen (N) and its biosynthetic incorporation into both virus and host proteins using an isotope-labeling proteomics approach in a model marine cyanobacterium Synechococcus WH8102 infected by a lytic cyanophage S-SM1. By supplying dissolved N as 15N postinfection, we found that proteins in progeny phage particles were composed of up to 41% extracellularly derived N, while proteins of the infected host cell showed almost no isotope incorporation, demonstrating that de novo amino acid synthesis continues during infection and contributes specifically and substantially to phage replication. The source of N for phage protein synthesis shifted over the course of infection from mostly host derived in the early stages to more medium derived later on. We show that the photosystem II reaction center proteins D1 and D2, which are auxiliary metabolic genes (AMGs) in the S-SM1 genome, are made de novo during infection in an apparently light-dependent manner. We also identified a small set of host proteins that continue to be produced during infection; the majority are homologs of AMGs in S-SM1 or other viruses, suggesting selective continuation of host protein production during infection. The continued acquisition of nutrients by the infected cell and their utilization for phage replication are significant for both evolution and biogeochemical impact of viruses.

Viruses are increasingly recognized as ubiquitous, abundant, and integral players in microbial communities. In addition to their influence on population dynamics and host evolution, they also play important roles in the biogeochemistry of microbial ecosystems, particularly with regard to nutrient cycling (1–3). Viruses essentially compete with microbial cells for the nutrients that limit biological production, and viral productivity has been found to correlate with environmental nutrient availability in a variety of settings (4, 5). There are 2 basic sources for the nutrients, such as N and phosphorus (P), that viruses need for replication: (1) breakdown and recycling of host cell biomass, and (2) de novo biosynthesis using host metabolic machinery and nutrients derived from the extracellular environment. The balance of nutrients deriving from each of these sources underpins the relationship among host physiology, environmental nutrient availability, and viral productivity. Furthermore, the degree of host biomass degradation and acquisition of extracellular nutrients during infection influences the composition and stoichiometry of dissolved organic matter released upon lysis. Assumptions about the proportions of host- versus extracellularly sourced nutrients for viral replication have a strong influence on the predictions of viral ecology and biogeochemistry models (6, 7), yet empirical constraints on this balance for most virus-host systems are lacking (8).

There is, however, a long history of tracking the source and fate of viral biomolecule constituents in Escherichia coli and its phages, and this work lies at the foundation of modern molecular biology. The Hershey–Chase experiment (9), which showed that only the atomic constituents of the parental virion nucleic acid, and not of its protein, enter the host cell at the beginning of infection, is widely regarded as the first definitive evidence that DNA is the essential genetic material (10). Contemporaneously, a number of groups were using isotopic labels to understand the relative amounts of phage material that derived from the host cell as opposed to the medium with similar goals of understanding the fundamental roles of biochemicals. Cohen (11) showed that roughly 70% of the P in the DNA of the T2 and T4 phages of E. coli derives from the medium after infection, and Stent and Maaløe (12) demonstrated that phage DNA produced early in the infection derives its P more from preexisting host DNA than does later-synthesized phage DNA, whose P comes primarily from the medium. The only published measurements that specifically address the question of host-versus-medium-derived N for viral protein synthesis (13), which examined T6 phage infection of E. coli, found that as much as 91% of phage protein N could derive from the medium postinfection. Following this formative period of molecular biology, few studies explored viral nutrient sourcing in other phage–host systems. One study suggested that marine bacteriophages, in contrast to those of enteric bacteria, could derive nearly all their nucleotides from the host cell, perhaps as a result of adaptation to much lower ambient nutrient availability outside the cell (14).

Because phage particles are composed primarily of protein and nucleic acids, they are enriched in N and P, the nutrients that limit phytoplankton growth throughout much of the oceans, and have higher elemental N:C and P:C ratios compared with cellular biomass (8). Phages of marine bacteria have undergone selection for efficient replication under nutrient-limited conditions, which is likely to influence how the viruses acquire nutrients during infection. It is clear from marine viral genomes, which bear a variety of AMGs hypothesized to enhance the efficiency of nutrient acquisition or utilization during infection, that adaptation to chronic nutrient scarcity has shaped viral evolution just as much as that of their hosts (15, 16) and expression of AMGs during infection could also shape the balance between intra- and extracellularly derived nutrients. Here, we used a model marine cyanobacterium, Synechococcus WH8102, and T4-like myovirus, S-SM1, to explore the sourcing of N for phage protein production during infection. Using 15N isotopic labeling and novel proteomics techniques, we tracked N flow from the extracellular medium into individual phage and host proteins over the course of infection.

Results

Direct Incorporation of Acquired N into Viral Proteins.

We differentiated host biomass-derived versus extracellularly derived N in proteins using an isotope labeling approach (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Briefly, Synechococcus WH8102 host cells and the S-SM1 phage, each prepared in natural abundance (i.e., 0.4 atom% 15N) media, were mixed at high concentrations [∼7 to 9 × 107 cells/mL, multiplicity of infection (i.e., ratio of infective phages to host cells) of 3]. After allowing the phage to adsorb for 30 min, the cells were pelleted and then resuspended in medium containing 98 atom% 15NO3− as the sole N source. Thus, any N acquired from the medium during the infection would be 15N, while the preexisting host biomass contained 14N. Immediately after resuspension in the labeled medium and at 2, 4, and 7 to 9 h later, samples were collected for protein 15N-incorporation measurements in both intracellular (by pelleting infected cells by centrifugation) and extracellular (by filtering the supernatant) fractions. The infection experiment was performed at 3 different light intensities (126, 40, and 14 µmol photons m−2 s−1 using host cells that had been grown at the same respective light levels; herein abbreviated high light (HL), medium light (ML), and low light (LL), respectively) to explore the effects of host growth rate and light availability on phage nutrient incorporation. Isotope incorporation was determined by proteomic liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) analysis, using Topograph (17) to calculate atom% 15N in each identified peptide and a classifier we developed (see Methods) to quality filter the Topograph results and generate atom% 15N values for individual proteins (SI Appendix, Fig. S2).

We generated protein-specific 15N values for roughly 1,000 distinct phage and host proteins (out of 234 and 2,512 predicted protein-coding ORFs in the phage and host genomes, respectively) at each time point in the HL experiment. As expected, the number of detected phage proteins increased as the lytic cycle proceeded (Fig. 1 and SI Appendix, Table S1). We found that, on average, proteins in the phage particles released by lysis were composed of 41% medium-derived 15N at 8 h, while host cell proteins (with a small and specific set of exceptions, discussed below) showed no isotope incorporation over the course of the infection (Fig. 1). This is clear evidence that the dissolved 15N nitrate was taken up by infected cells, reduced to ammonium, and assimilated into amino acids, and those newly synthesized amino acids specifically utilized in the translation of phage proteins without incorporation into the host proteome. This ongoing activity is the work of host biosynthetic machinery, despite general suppression of host gene expression, since the phage does not encode any genes for these processes. These data demonstrate that cyanophages can acquire a substantial proportion of their building blocks from the extracellular medium after infection begins, consistent with prior E. coli results (13). The isotopic enrichment appeared first in phage proteins in the cell pellet and only later in the extracellular phage protein in the supernatant, following cell lysis and the release of the progeny phage (Fig. 1). In conjunction with the absence of host labeling, this is further evidence that the isotope incorporation occurred in infected cells and not, for example, by a subpopulation of uninfected cells taking up the label and producing amino acids that were subsequently acquired by infected hosts.

Fig. 1.

Time courses of cell lysis, phage production, and protein 15N incorporation during infection of Synechococcus WH8102 by phage S-SM1 in HL conditions (126 µmol photons m−2 s−1). (A) Extracellular phage genome copies (by qPCR of g20) and phycoerythrin fluorescence (from lysed cell debris); points and error bars are averages and ±1 SD, respectively, across experimental triplicates. (B and C) Distributions of atom% 15N values of host (purple) and phage (green) proteins in (B) intracellular (i.e., cell pellet) and (C) extracellular (i.e., >10 kDa/<0.2 µm filtrate) samples; the numbers at the top indicate the number of proteins detected for host and phage at each timepoint, the gray bars show values of individual proteins (averaged across experimental triplicates), the colored horizontal lines show host and phage medians at each timepoint.

Uptake of extracellular N into phage protein was modulated by light intensity, while average 15N incorporation into host protein remained negligible across all treatments. 15N incorporation levels into phage proteins were nearly equivalent between the HL and the ML experiments, indicating that neither the decreased light availability nor somewhat lowered host growth rate (µ = 0.61/d at ML, 0.66/d at HL) at the medium compared with the HL condition had a strong impact on sourcing of N for phage protein production (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). In the LL condition (host µ = 0.33/d), by contrast, phage proteins showed significantly less 15N incorporation, reaching only 25% 15N by 9 h postinfection. This reduced incorporation of extracellular N suggests that the slower-growing host cells may afford the infecting phages less nutrient acquisition capacity (possibly due to limitation of photosynthetically generated reductant for nitrate reductase), which, in turn, delays and/or reduces viral productivity (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). These results illustrate how environmental controls on host physiology—in this case, light limitation of a photoautotroph—can influence the sourcing of nutrients for viral replication and show that the balance between host- and extracellularly derived nutrients is not strictly “hardwired” into the viral infection program.

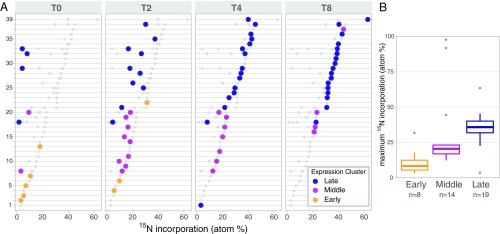

Later-Expressed Viral Proteins Derive Less N from Host.

Our molecular-level isotope incorporation data also show how extracellularly derived N is funneled into the translational program of phage S-SM1. Genes in T4-like cyanomyoviruses can be categorized into early, middle, and late expression clusters based on the timing of peak transcription and on shared promoter motifs (18). We observed progressive 15N incorporation into proteins produced over the course of this expression program with the proteins produced earlier in the infection incorporating less 15N from the medium than those synthesized later (Fig. 2A). This progression was also detectable within individual late phage proteins, a number of which increased in 15N content steadily over the first 4 h of infection. The maximum 15N incorporation for phage proteins expressed from early genes was 8%, compared with 21% for middle genes and 36% for late genes (median values for each class) (Fig. 2B). The increase in 15N incorporation levels over this expression time course demonstrates a shift in the source of N for phage protein synthesis from primarily host derived in the early stages of infection to more extracellularly derived for the later production of progeny virion particles.

Fig. 2.

(A) Incorporation of medium-derived 15N into 39 proteins of phage S-SM1 during infection under HL conditions (see SI Appendix, Fig. S5 for annotations and the position of 2 outliers excluded from the middle cluster). Panels show isotope incorporation detected at each timepoint (t = 0, 2, 4, and 8 h after 15N addition) into proteins that are classified by their transcriptional timing into early, middle, and late expression clusters. The colored points show the atom% 15N determined for a given protein at the timepoint indicated; the gray points show the atom% 15N values for that protein at all other timepoints for comparison. (B) Distributions of the maximum atom% 15N values observed across timepoints for proteins in each of the early, middle, and late expression categories. The boxes show medians and 25th/75th percentiles, the whiskers are ±1.5×IQR; the gray dots show outliers.

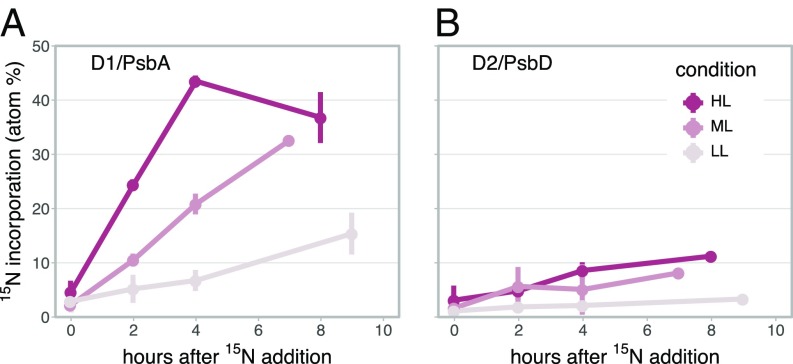

Turnover of Phage-Encoded Photosystem II Proteins.

The genes psbA and psbD, encoding the photosystem II reaction center proteins D1 and D2, were the first AMGs to be recognized in the genomes of cyanophages (19, 20). These proteins form the core of the water-splitting electron transport machinery for oxygenic photosynthesis, and the virus-encoded versions have been shown to produce functional proteins during infection (21). These proteins are also susceptible to photodamage and must be continually renewed—especially D1, which turns over as rapidly as every 30 min to an hour (22–24). Expression of D1 and D2 from phage-encoded loci is thought to compensate for the shutdown of host expression of these proteins and thereby enable continued photosynthetic electron transport and energy metabolism during infection, enhancing phage production (24–26).

We detected 15N incorporation into both D1 and D2, indicating de novo synthesis of these reaction center proteins during S-SM1 infection of Synechococcus WH8102 (Fig. 3). The peptides we detected are common to both host- and phage-encoded versions of the proteins, so they cannot be unequivocally assigned to one or the other. However, given that phage PSII genes are known to yield functional protein during infection (21), and here D1 and D2 show 15N labeling patterns consistent with other phage proteins, we believe the synthesis observed here is most likely from the phage genes. Both proteins became more 15N enriched over the course of the experiment at a higher rate with increasing light intensity (Fig. 3). Additionally, D1 was always more 15N enriched than D2, consistent with its higher rate of turnover due to photodamage. These results provide the first experimental validation of the assumption of light-responsive PSII expression/repair during cyanophage infection made in previous modeling studies (25, 26). Notably, while phage proteins were labeled to similar overall extents in the ML and HL experiments (SI Appendix, Fig. S4), D1 and D2 were consistently more labeled at HL, suggesting either higher rates of photodamage that drove faster turnover or greater net synthesis of the proteins at higher intensity.

Fig. 3.

Time courses of 15N incorporation into photosystem II reaction center proteins (A) D1/PsbA and (B) D2/PsbD during infection under HL, ML, and LL conditions.

Exogenous N Incorporation into Specific Host Proteins.

While the vast majority of host proteins showed little to no 15N incorporation during infection (Fig. 1 and SI Appendix, Fig. S3), we found that 12 host-encoded proteins did incorporate significant 15N, indicating their continued production from newly synthesized amino acids despite the general suppression of host gene expression (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Figs. S6 and S7). While transcriptional studies in related cyanophage systems have documented continued mRNA synthesis of select host genes during infection (18, 27), our results identified a distinct set of host response proteins. Intriguingly, the majority of these host proteins (8/12) have homologs (i.e., AMGs) in the genomes of S-SM1 or other phages and/or on putative viral genome fragments from aquatic viral metagenome datasets (Dataset S1). This finding suggests that continued expression of these proteins may be advantageous for the phage. Consistent with this hypothesis, there is prior experimental evidence for several of these proteins demonstrating their activity during phage infection and their importance in maximizing progeny phage production.

Fig. 4.

15N incorporation time courses in the HL condition of the 12 Synechococcus WH8102 host proteins that became significantly labeled in our phage infection experiments. The circles after gene names indicate the presence of a homolog in viral (meta)genome sequences: ••• = present in the S-SM1 genome; •• = present in other viral isolate genomes; • = present in putative viral contigs from aquatic metagenomic data (Dataset S1).

One of the most strongly labeled host proteins was heme oxygenase, which catalyzes the first step in phycobilin pigment biosynthesis, a pathway for which multiple AMGs exist in phage genomes (28, 29); there is also biochemical evidence for ongoing synthesis (30) and degradation (31) of phycobilisomes during infection. Heme oxygenase is found in the genomes of several Prochlorococcus phages but only a single Synechococcus phage S-SM7 (15). While the function of bilin biosynthesis during phage infection remains unclear (29), the 15N incorporation we observed suggests that some phages without these genes (such as S-SM1) can maintain expression of host phycobilin metabolism.

We detected 15N labeling of several host proteins involved in protein production or maturation (Fig. 4). Methionyl aminopeptidase removes initiator methionine residues, the second step in the N-terminal methionine excision (NME) pathway of protein maturation. Many marine phage genomes have been found to encode peptide deformylases that remove the N-formyl group from these sites, the first step in the NME pathway (32, 33). NME is necessary for stable assembly of the D1/D2 reaction center of photosystem II (34), so the continued production of methionyl aminopeptidase may be linked to phage PSII protein expression. One amino acid biosynthesis protein, cysteine synthase A, also acquired the 15N label; continued turnover of this enzyme might support production of Cys-rich pigment-linked phycobiliproteins (28) or could have an alternative regulatory function (35). We also detected 15N labeling of host ribosomal protein S21, which is necessary for mRNA binding and translation initiation (36). Homologs of these 3 proteins—methionyl aminopeptidase, cysteine synthase A, and ribosomal protein S21—have been identified in viral genomes or putative viral contigs, consistent with the idea that their expression during infection enhances viral fitness (32, 37).

The pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), which respires stored carbon and generates reducing power and nucleotide biosynthesis precursors, has been implicated as a major target of metabolic remodeling during cyanophage infection (38). Three host-encoded enzymes are involved in glycogen degradation via the PPP acquired 15N label: glycogen phosphorylase, phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, and transaldolase. The latter 2 (gnd and talC) are widespread AMGs among marine cyanophages (15), and their continued synthesis from the host loci during infection is particularly interesting given that S-SM1 encodes its own copies of these enzymes. While the phage-encoded TalC protein was not detected in our datasets, the phage-encoded Gnd was also clearly 15N labeled (SI Appendix, Fig. S8), indicating that de novo synthesis of this enzyme proceeded from both host and phage loci during infection. The host-encoded CP12 repressor of the Calvin cycle also acquired the 15N label (SI Appendix, Fig. S8)—albeit to an extent just slightly below the P value threshold for the set of most-significantly labeled host genes (SI Appendix, Fig. S6)—and its continued expression may act to steer carbon flux toward the PPP (38). Our results here suggest that enhancement of metabolic flux through the PPP during cyanophage infection could be mediated by simultaneous protein expression from both phage and host copies of homologous genes.

Continued de novo synthesis of other host proteins may point to cellular defense mechanisms against phage infection. The Rho termination factor, which acquired the 15N label in our experiments, has been implicated in silencing of foreign DNA elements as a defense against deleterious effects of their expression (39, 40). Likewise, we detected labeling of ribonuclease J, which may act to degrade phage transcripts and inhibit infection progress, or, conversely, to drive mRNA turnover and enable phage transcription (41). Three hypothetical proteins—SYNW1071, SYNW1249, and SYNW0829, the last of which has a homolog in a putative cyanophage contig from the North Pacific (Dataset S1)—were also found to become significantly labeled. It is clear that we are just beginning to recognize the diversity of host defense systems and components of the host metabolism that interact with phage replication (42, 43); the highly labeled hypothetical proteins observed in this study could be useful targets for future functional characterization.

Given the striking correspondence between the small number of host proteins found to be 15N labeled during S-SM1 infection and the set of metabolic processes known or inferred to be influenced by phage-encoded AMGs, it is possible that this apparently selective continuation of host protein production during infection represents either an early or a late stage in the process of phage AMG acquisition (27). For example, this specific expression from a host gene could be an early metabolic rewiring strategy evolved by phages before investing in carrying an AMG encoding the induced function in their own genome. Alternatively, gaining the ability to selectively express certain host proteins during infection may allow phages to dispense with their own AMG copies and, thus, represent a later stage of the process. Discriminating between these scenarios will require elucidation of the mechanism of the seemingly targeted continuation of expression of particular host-encoded genes during infection. This could be mediated via transcription (18) or post-transcriptionally through specific mRNA stabilization or translational-level mechanisms, such as ribosome recruitment (44).

Discussion

This work has demonstrated that phages of cyanobacteria acquire substantial amounts of N for protein synthesis from the extracellular environment after infection begins, through continued operation of host nutrient acquisition and biosynthesis machinery. Our results are consistent with earlier findings of extracellular N deprivation suppressing phage productivity (45). Phage nucleic acids, known to be produced mainly during the early stages of infection before synthesis and assembly of virion structural proteins, contain less extracellularly derived N than phage protein does (13), in accord with the temporal shift we observed toward more medium-derived N sourcing. These results parallel those of Stent and Maaløe (12) regarding the shift in the sourcing of P for phage DNA synthesis in the E. coli-T4 system and suggest that this shift from more host-derived to more extracellularly derived nutrients for phage production over the course of infection could be a general feature of a range of lytic phages.

Pasulka et al. (46) recently documented enhanced incorporation of 15N into Syn1 viral particles using NanoSIMS during a multiday infection experiment using Synechococcus WH8101 as a host but with the extended duration of that experiment and the inability to measure isotopic compositions of specific host- and virus-derived biomolecules that study could not differentiate between concurrent labeling of host and phage proteins and direct incorporation of the exogenous nitrogen into viral particles. We have shown that such labeling of viral biomolecules by an extracellular isotope tracer can occur in the absence of detectable incorporation of the label into host biomass, clearly demonstrating direct transfer of dissolved nutrients to viral particles. In contrast to the conclusions of Wikner et al. (14), our results indicate that de novo biosynthesis during infection does contribute substantially to productivity of at least some marine phages.

Extracellular N was a substantial but minority source of N for phage replication in these experiments; under all conditions tested, more than half of phage protein N was host cell derived. A bacterial cell generally contains many times the protein N required by even large phage bursts: the roughly 1 fmol of protein N per Synechococcus cell (47, 48) could theoretically be converted (at ∼1 amol N per phage; ref. 8) into 1,000 myophage progeny. Even setting aside some portion of the host proteome (e.g., in ribosomes) as required for phage replication and, therefore, “off limits,” extracellular N incorporation would not seem to be necessary on a mass-balance basis. Our results suggest that, at some point, it becomes energetically or kinetically preferable for the phage replication program to shift from host protein catabolism toward de novo amino acid synthesis.

The experiments of Kozloff et al. (13) on T6 infection of E. coli found even higher levels of medium-derived N in phage particles, up to 91%. Host growth rates in those experiments were not reported but were likely higher than those in this study. This earlier evidence as well as the lower level of isotope incorporation we observed in the LL experiment (SI Appendix, Fig. S3) are consistent with the notion that phages infecting slower-growing hosts take less advantage of exogenous N than those infecting fast-growing hosts. In this, our results are consistent with Wikner et al. (14), who also found lowered extracellular P incorporation when phages infected slow-growing hosts. This may be because slow-growing host cells contain less machinery for nutrient uptake, monomer synthesis, and/or macromolecule polymerization, and so phages cannot acquire as much additional N or P over the constrained time frame of the infection. This limitation could be one factor that contributes to correlation between host growth rate and phage productivity.

Current ecosystem and biogeochemical models that incorporate the effects of viral lysis (e.g., refs. 6 and 7) often assume that the N/P content of virions released upon lysis cannot exceed the N/P content of uninfected hosts, providing a key boundary condition in such models. Our results indicate that, at least for N and potentially also for P, the nutrient content of host cells is, in fact, not a reliable bound on the resources available for phage replication and that ongoing host cell metabolism during infection contributes substantially to viral productivity (49). It seems increasingly clear that virally infected cells must be treated as a separate category of agents in ecosystem models as their metabolism, which remains highly active in many respects, has been so extensively rewired by viral takeover (50). When considering observed rates of nutrient uptake, for example, in microbial ecosystems, biogeochemical models need to acknowledge that a proportion of that uptake—for which the kinds of methods employed here can start to provide constraints—is flowing directly to viral production. In nutrient-limited conditions, both the intracellular quotas and the extracellular availability of nutrients will be lower than in the replete conditions employed here, and the balance of nutrient sourcing for viral replication is likely to shift. Whether viral replication is limited by the same resources as host growth depends on the relative abilities of the phage to exploit the standing stock of host biochemical resources and to rewire host metabolic machinery to acquire additional nutrients from the environment.

Methods

Cell Cultivation and Phage Infection.

Axenic Synechococcus WH8102 was grown in L1 medium (51) with 882 µM added 14NO3− under 3 light regimes (14.4 ± 0.6, 39.5 ± 2.3, and 126.0 ± 4.6 µmol photons m−2 s−1) and infected with phage S-SM1 at a multiplicity of infection (i.e., ratio of infective phage to host cells) of 3. Following phage adsorption, infected cells were pelleted by centrifugation, and the pellets resuspended in L1 medium with 882 µM 15NO3− (99 atom% 15N) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). All experiments were performed in triplicate. Samples were taken immediately (T0 with respect to 15N addition) and 2, 4, and 7 to 9 h later for intra- and extracellular proteomic analysis and hourly for fluorescence and quantitative PCR monitoring of infection progress (further details in SI Appendix).

Proteomic MS and Atom% 15N Determination.

Cell pellets (intracellular protein fraction) were extracted, and supernatants (extracellular protein fraction) were concentrated before spin filter purification, trypsin digestion, and LC-MS/MS analysis. Peptides were identified via SEQUEST HT (52) and Percolator (53). Topograph (17) was used to calculate the atom% 15N in each identified peptide. Peptide-level data were mapped to the proteomes of WH8102 and S-SM1 and filtered using the calibration-based classification model (SI Appendix). Protein-level data were averaged across the experimental triplicates, and the error taken as ±1 SD between the replicates; see SI Appendix for further details of proteomics analyses. Raw proteomic mass spectral data are deposited in the MassIVE repository under accession MSV000083830.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Gerry Olack, Xiufeng Ma, and Stewart Edie for discussions and advice and to anonymous reviewers whose comments improved the paper. This work was supported by the Gordon & Betty Moore Foundation Marine Microbiology Initiative (Award 3305) and the Simons Foundation (Award 402971).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: Proteomic mass spectral data are available in the Mass Spectrometry Interactive Virtual Environment (MassIVE) repository, ftp://massive.ucsd.edu/MSV000083830.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1901856116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Danovaro R., et al. , Marine viruses and global climate change. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 35, 993–1034 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weitz J. S., Quantitative Viral Ecology: Dynamics of Viruses and Their Microbial Hosts (Princeton University Press, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mateus M. D., Bridging the gap between knowing and modeling viruses in marine systems—An upcoming frontier. Front. Mar. Sci. 3, 284 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Motegi C., Kaiser K., Benner R., Weinbauer M. G., Effect of P-limitation on prokaryotic and viral production in surface waters of the Northwestern Mediterranean Sea. J. Plankton Res. 37, 16–20 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nabergoj D., Modic P., Podgornik A., Effect of bacterial growth rate on bacteriophage population growth rate. MicrobiologyOpen 7, e00558 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weitz J. S., et al. , A multitrophic model to quantify the effects of marine viruses on microbial food webs and ecosystem processes. ISME J. 9, 1352–1364 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edwards K. F., Steward G. F., Host traits drive viral life histories across phytoplankton viruses. Am. Nat. 191, 566–581 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jover L. F., Effler T. C., Buchan A., Wilhelm S. W., Weitz J. S., The elemental composition of virus particles: Implications for marine biogeochemical cycles. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12, 519–528 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hershey A. D., Chase M., Independent functions of viral protein and nucleic acid in growth of bacteriophage. J. Gen. Physiol. 36, 39–56 (1952). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stent G. S., A short epistemology of bacteriophage multiplication. Biophys. J. 2, 13–23 (1962). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen S. S., The synthesis of bacterial viruses; the origin of the phosphorus found in the desoxyribonucleic acids of the T2 and T4 bacteriophages. J. Biol. Chem. 174, 295–303 (1948). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stent G. S., Maaløe O., Radioactive phosphorus tracer studies on the reproduction of T4 bacteriophage. II. Kinetics of phosphorus assimilation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 10, 55–69 (1953). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kozloff L. M., Knowlton K., Putnam F. W., Evans E. A. J. Jr, Biochemical studies of virus reproduction. V. The origin of bacteriophage nitrogen. J. Biol. Chem. 188, 101–116 (1951). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wikner J., Vallino J. J., Steward G. F., Smith D. C., Azam F., Nucleic acids from the host bacterium as a major source of nucleotides for three marine bacteriophages. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 12, 237–248 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crummett L. T., Puxty R. J., Weihe C., Marston M. F., Martiny J. B. H., The genomic content and context of auxiliary metabolic genes in marine cyanomyoviruses. Virology 499, 219–229 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hurwitz B. L., U’Ren J. M., Viral metabolic reprogramming in marine ecosystems. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 31, 161–168 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsieh E. J., et al. , Topograph, a software platform for precursor enrichment corrected global protein turnover measurements. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 11, 1468–1474 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doron S., et al. , Transcriptome dynamics of a broad host-range cyanophage and its hosts. ISME J. 10, 1437–1455 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mann N. H., Cook A., Millard A., Bailey S., Clokie M., Marine ecosystems: Bacterial photosynthesis genes in a virus. Nature 424, 741 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindell D., et al. , Transfer of photosynthesis genes to and from Prochlorococcus viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 11013–11018 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindell D., Jaffe J. D., Johnson Z. I., Church G. M., Chisholm S. W., Photosynthesis genes in marine viruses yield proteins during host infection. Nature 438, 86–89 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohad I., Kyle D. J., Arntzen C. J., Membrane protein damage and repair: Removal and replacement of inactivated 32-kilodalton polypeptides in chloroplast membranes. J. Cell Biol. 99, 481–485 (1984). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kulkarni R. D., Golden S. S., Adaptation to high light intensity in Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942: Regulation of three psbA genes and two forms of the D1 protein. J. Bacteriol. 176, 959–965 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bailey S., Clokie M. R. J., Millard A., Mann N. H., Cyanophage infection and photoinhibition in marine cyanobacteria. Res. Microbiol. 155, 720–725 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bragg J. G., Chisholm S. W., Modeling the fitness consequences of a cyanophage-encoded photosynthesis gene. PLoS One 3, e3550 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hellweger F. L., Carrying photosynthesis genes increases ecological fitness of cyanophage in silico. Environ. Microbiol. 11, 1386–1394 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindell D., et al. , Genome-wide expression dynamics of a marine virus and host reveal features of co-evolution. Nature 449, 83–86 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Puxty R. J., Millard A. D., Evans D. J., Scanlan D. J., Shedding new light on viral photosynthesis. Photosynth. Res. 126, 71–97 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ledermann B., Aras M., Frankenberg-Dinkel N., “Biosynthesis of cyanobacterial light-harvesting pigments and their assembly into phycobiliproteins” in Modern Topics in the Phototrophic Prokaryotes, Hallenbeck P. C., Ed. (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2017), pp. 305–340. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shan J., Jia Y., Clokie M. R. J., Mann N. H., Infection by the ‘photosynthetic’ phage S-PM2 induces increased synthesis of phycoerythrin in Synechococcus sp. WH7803. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 283, 154–161 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma X., Coleman M. L., Waldbauer J. R., Distinct molecular signatures in dissolved organic matter produced by viral lysis of marine cyanobacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 20, 3001–3011 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharon I., et al. , Comparative metagenomics of microbial traits within oceanic viral communities. ISME J. 5, 1178–1190 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frank J. A., et al. , Structure and function of a cyanophage-encoded peptide deformylase. ISME J. 7, 1150–1160 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giglione C., Vallon O., Meinnel T., Control of protein life-span by N-terminal methionine excision. EMBO J. 22, 13–23 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Campanini B., et al. , Moonlighting O-acetylserine sulfhydrylase: New functions for an old protein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1854, 1184–1193 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Duin J., Wijnands R., The function of ribosomal protein S21 in protein synthesis. Eur. J. Biochem. 118, 615–619 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mizuno C. M., et al. , Numerous cultivated and uncultivated viruses encode ribosomal proteins. Nat. Commun. 10, 752 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thompson L. R., et al. , Phage auxiliary metabolic genes and the redirection of cyanobacterial host carbon metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, E757–E764 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cardinale C. J., et al. , Termination factor Rho and its cofactors NusA and NusG silence foreign DNA in E. coli. Science 320, 935–938 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mitra A., Nagaraja V., Under-representation of intrinsic terminators across bacterial genomic islands: Rho as a principal regulator of xenogenic DNA expression. Gene 508, 221–228 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Condon C., What is the role of RNase J in mRNA turnover? RNA Biol. 7, 316–321 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fedida A., Lindell D., Two Synechococcus genes, two different effects on cyanophage infection. Viruses 9, 136 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doron S., et al. , Systematic discovery of antiphage defense systems in the microbial pangenome. Science 359, eaar4120 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stern-Ginossar N., Thompson S. R., Mathews M. B., Mohr I., Translational control in virus-infected cells. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 11, 033001 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fowler C. B., Cohen S. S., Chemical studies in host-virus interactions; a method of determining nutritional requirements for bacterial virus multiplication. J. Exp. Med. 87, 259–274 (1948). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pasulka A. L., et al. , Interrogating marine virus-host interactions and elemental transfer with BONCAT and nanoSIMS-based methods. Environ. Microbiol. 20, 671–692 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bertilsson S., Berglund O., Karl D. M., Chisholm S. W., Elemental composition of marine Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus : Implications for the ecological stoichiometry of the sea. Limnol. Oceanogr. 48, 1721–1731 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heldal M., Scanlan D. J., Norland S., Thingstad F., Mann N. H., Elemental composition of single cells of various strains of marine Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus using X-ray microanalysis. Limnol. Oceanogr. 48, 1732–1743 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Birch E. W., Ruggero N. A., Covert M. W., Determining host metabolic limitations on viral replication via integrated modeling and experimental perturbation. PLoS Comput. Biol. 8, e1002746 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rosenwasser S., Ziv C., Creveld S. G. V., Vardi A., Virocell metabolism: Metabolic innovations during host-virus interactions in the Ocean. Trends Microbiol. 24, 821–832 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guillard R. R. L., Hargraves P. E., Stichochrysis immobilis is a diatom, not a chrysophyte. Phycologia 32, 234–236 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eng J. K., McCormack A. L., Yates J. R., An approach to correlate tandem mass spectral data of peptides with amino acid sequences in a protein database. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 5, 976–989 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Käll L., Canterbury J. D., Weston J., Noble W. S., MacCoss M. J., Semi-supervised learning for peptide identification from shotgun proteomics datasets. Nat. Methods 4, 923–925 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.