Abstract

Trypsin and chymotrypsin-like serine proteases from family S1 (clan PA) constitute the largest protease group in humans and more generally in vertebrates. The prototypes chymotrypsin, trypsin and elastase represent simple digestive proteases in the gut, where they cleave nearly any protein. Multidomain trypsin-like proteases are key players in the tightly controlled blood coagulation and complement systems, as well as related proteases that are secreted from diverse immune cells. Some serine proteases are expressed in nearly all tissues and fluids of the human body, such as the human kallikreins and kallikrein-related peptidases with specialization for often unique substrates and accurate timing of activity. HtrA and membrane-anchored serine protease fulfill important physiological tasks with emerging roles in cancer. The high diversity of all family members, which share the tandem β-barrel architecture of the chymotrypsin-fold in the catalytic domain, is conferred by the large differences of eight surface loops, surrounding the active site. The length of these loops alters with insertions and deletions, resulting in remarkably different three-dimensional arrangements. In addition, metal binding sites for Na+, Ca2+ and Zn2+ serve as regulatory elements, as do N-glycosylation sites. Depending on the individual tasks of the protease, the surface loops determine substrate specificity, control the turnover and allow regulation of activation, activity and degradation by other proteins, which are often serine proteases themselves. Most intriguingly, in some serine proteases, the surface loops interact as allosteric network, partially tuned by protein co-factors. Knowledge of these subtle and complicated molecular motions may allow nowadays for new and specific pharmaceutical or medical approaches.

Abbreviations

- CARASIL

cerebral autosomal recessive arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy

- CUB

complement C1r/C1s/Uegf/Bmp1

- DESC

differentially expressed in squamous cell carcinoma

- EGF-like

epidermal growth factor-like

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- FIMAC

Factor I (CI) membrane attack complex

- Gla

γ- carboxyglutamate

- HAP

haemagglutinin protease

- HAT

human airway trypsin

- LDLR

low density lipoprotein receptor

- MAM

meprin/A-5 protein/receptor protein-tyrosine phosphatase mu

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- PAR

proteinase activated receptor

- PDZ

post synaptic density protein (PSD95)/Drosophila disc large tumor suppressor (Dlg1)/zonula occludens-1 protein (zo-1)

- PSA

prostate specific antigen

- TMPRSS

Transmembrane protease, serine

- SCRC

scavenger receptor cysteine rich

- SEA

sea urchin sperm protein/enterokinase/agrin

1. Introduction

Among the known proteases the family S1 from the clan PA stands out with the largest number of members and highly diverse endopeptidase functions, according to its classification in the early 1990s [1]. Bovine chymotrypsin was the first protease, whose structure was determined at atomic resolution (Fig. 1) [2]. Based on the research history, the prototypic chymotrypsin A serves as reference for the numbering scheme proposed by Hartley in 1970 for the catalytic domain [3]. Thus, the catalytic triad residues are designated His57, Asp102 and Ser195 as in chymotrypsinogen A, which are present in all members of the subclan PA(S) [4]. The chymotrypsin fold is even preserved in several viral proteases of subclan PA(C), with His-Asp-Cys or His-Glu-Cys catalytic triads and His-Cys dyads [5]. Most of them are picornains, such as the poliovirus gene 3C product [6], while bacterial and viral serine proteases of 13 other families from S3 to S75 possess His-Asp-Ser triads [7].

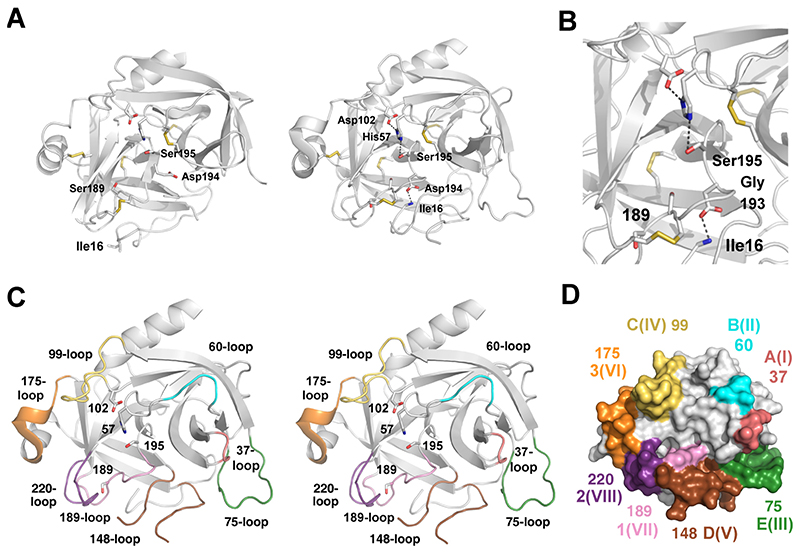

Figure 1. The chymotrypsin/trypsin fold consisting of two β-barrels and eight surface loops.

1A: The left panel shows the crystal structure of the proform or zymogen of bovine chymotrypsinogen A (PDB code 1CHG [288]) and the right panel displays the active form (2CHA [289]), both in ribbon representation. The catalytic triad residues Ser195, His57, and Asp102 are depicted as stick models, as well as the specificity determining Ser189 and the five disulfide bridges. Upon activation with formation of a salt bridge between the new N-terminus Ile16 and Asp194, large rearrangements are seen around the active site, which rigidifies and shapes the S1 pocket. 1B: Close-up view of the active site. Hydrogen bonds are shown as dotted lines. Residue 189 at the bottom of the S1 subsite is the crucial residue that determines the primary specificity of serine proteases, while the oxyanion hole, based on the N-H groups of Ser195 and Gly193 stabilizes the transition state of substrates at the scissile bond. 1C: Stereo representation of chymotrypsin with the eight surface loops in color around the active site. The numbering scheme is mainly based on the central residue of the loop, as derived from bovine chymotrypsinogen A (bCTRA) or by the most common designations. All these loops show significant variations among the S1 family proteases and can serve as regulatory elements. 1D: Molecular surface of bCTRA with the eight colored active site loops and alternative numbering schemes, e.g. I-VIII, or as proposed by Perona and Craik (A–E and 1-3) [14].

A multiple gene duplication encoding a 5-6 amino acid proto-strand has been suggested for the early evolution of trypsin-like proteins, which eventually assembled in two six-stranded antiparallel β-barrel domains [8]. According to the high diversification of functional trypsin-like proteases and their distribution from bacteria to vertebrates, a family tree was assumed that is more than one billion years old [9]. Since most trypsin-like serine proteases genes have the codon TCN (N = A/G/C/T) for the catalytic Ser195 and most blood coagulation factors genes have the corresponding serine codon AGY (Y = C/T), it was hypothesized that the latter ones evolved from proteases with cysteine (codon TGY) and threonine nucleophiles (codon ACN), respectively [7, 10]. Also, in some non-peptidase homologs of trypsin-like proteases the catalytic residues have been replaced by various amino acids residues, such as Arg57 or Asn195 in examples from snake venom [11].

After protein synthesis precursors of the S1 family are translocated to the endoplasmic reticulum with an N-terminal signal peptide that is cleaved by the Sec transmembrane complex. Some of these proteases can already be active, while others are transported as zymogens via the Golgi to secretory vesicles, undergoing posttranslational modifications [12]. Proteolytic cleavage of the propeptide activates the protease after secretion to the extracellular matrix, blood plasma and other body fluids. Usually, the N-terminal Ile16 or Val16 residues in the chymotrypsin numbering scheme insert into the so-called activation pocket (Fig. 1A). Thereby the N-terminal amino group forms a salt-bridge with Asp194, which rearranges and stabilizes the active site, in particular the catalytic triad, the oxyanion hole and the S1 specificity pockets (Figs. 1A, B). The general catalytic mechanism of serine peptidases is described in a concise overview by Polgar in the Handbook of Proteolytic enzymes [13]. Eight surface loops around the active site are the major determinants of specificity and regulation (Figs. 1C, D) [14].

Although the family is termed trypsin-like according to their three-dimensional fold, their members display three major substrate preferences. True trypsin-like peptidases cleave amide bonds after Arg or Lys in the P1 position, chymotrypsin-like ones prefer Phe, Tyr and other large hydrophobic P1 residues, while elastase-like ones accept only small hydrophobic P1 residues, such as Ala, Val or Thr. However, some S1 family peptidase exhibit mixed or more specialized P1 preferences. In addition, the extended specificity up to the P4 and P4′ positions and sometimes further results in an enormous diversity with respect to protease substrates. This specificity depends to a great deal on the eight surface loops around the active site, which confer most of the functional characteristics to individual proteases [15]. Moreover, the focus of this review is on the chymo/trypsin-like serine proteases of the family S1, in particular for the 176 human members, with essential physiological and disease-related functions.

2. Functional classes of serine proteases in the family S1

2.1. Digestive serine proteases from the pancreas, their activators and variants

After proteolytic cleavage in the stomach by the aspartic protease pepsin and its isoforms, three major types of serine proteases cleave proteins into smaller fragments, which are eventually degraded to free amino acids by exopeptidases, such as various amino- and carboxypeptdidases. The activation cascade of pancreatic enzymes is not fully understood, but it comprises more additional pathways and feedback loops as in current textbook schemes (Fig. 2A) [16].

Figure 2. Trypsin-like serine proteases in the digestive tract of the small intestine.

2A: Activation scheme. The membrane anchored, mosaic enteropeptidase (EK, trypsin-like serine protease domain in red, with additional domains) activates trypsin (TRY) by cleavage of the N-terminal propeptide, whereby the neo-N-terminus inserts in the activation pocket, depicted as N within the active protease domain in red. Trypsin activates chymotrypsins (CTR), elastases (ELA), carboxypeptidases (CBP) and tissue kallikrein 1 (KLK1). 2B: Overlay of bovine chymotrypsin B (green, PDB code 1CBW [290]), human trypsin-1 (red, 1TRN [291]) and porcine elastase 2A (yellow, 1BRU). These proteases are highly conserved in mammals, whereby trypsin is seven residues shorter than chymotrypsin, while elastase is eighth residues longer. The most distinguishing features are the primary specificity determining Asp189 of trypsin and Ser189 in chymotrypsin and elastase. The latter possesses a Ser226 instead of Gly226, which excludes the binding of large S1 side-chains. In addition, trypsin exhibits three Glu residues in the 75-loop, which bind the activity-enhancing Ca2+. 2C: Molecular surface of chymotrypsin, trypsin and elastase with electrostatic potential. Depending on the overall short surface loops, most specificity pockets, except the S1 subsite are not well defined and allow interaction with various substrate side-chains. Trypsin has a strong negative potential (red) in the S1 pocket and binds basic P1-Arg and Lys residues. Chymotrypsin prefers hydrophobic, aromatic P1-residues, such as Phe, Tyr and Trp, whereas elastase accepts shorter side-chains, such as Ala, Val, Ile, and Thr.

2.1.1. Trypsins

The prototype of all trypsin-like serine proteases in family S1 is the eponymous trypsin (MEROPS classification S01.151, enzyme catalogue number EC 3.4.21.4) from pancreas, which secretes a mixture of trypsinogen-1 (~65%), -2 (~33%) and -3 (<2%) into the duodenum, the first section of the small intestine [17]. Also with respect to structural data, trypsin is the prototype of family S1 proteases besides chymotrypsin, since the crystal structure of bovine trypsin was determined in 1974 [18, 19].

Enteropeptidase or enterokinase from the hepsin/TMPRSS family (see section 2.6.) is a heavily glycosylated, membrane-anchored “mosaic” protease in the brush border of the duodenal mucosa with tryptic specificity [20]. While the activator of enteropeptidase is still not well characterized, it generates active trypsin-1, trypsin-2 and trypsin-3 by cleavage of the propeptide VDDDDK from Ile16. Then, trypsin activates chymotrypsinogen, proelastase and procarboxypeptidase, a metalloprotease zymogen, before these proteases can degrade proteins from food in a rather promiscuous manner. The relatively low overall specificity of trypsin except for P1-Arg and -Lys residues can be explained by the wide specificity pockets and adjacent short surface loops around the active site (Figs. 2B, C). Small differences in the sequence and structure of the three trypsins confer a slightly altered preference not only for substrates, but also in the interaction with natural inhibitors [17]. Trypsin-3 or “mesotrypsin” is up-regulated in various aggressive cancer types, with an impact on metastasis formation and tumor growth, as it can cleave and inactivate protease inhibitors [21].

Pancreatitis leads in 40% of the patients to pancreatic cancer. Mutations in the trypsin-1 (PRSS1) gene as well as in the serine protease inhibitor Kazal type 1 encoding gene SPINK1 and in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) are implicated in hereditary pancreatitis [22]. Pathogenic mutations in the SPINK1 gene result in a decreased trypsin inhibitor expression, whereas the two trypsin-1 missense variants Arg117His (chymotrypsinogen numbering) and Asn21Ile account for almost 90% of all pancreatitis cases and both are associated with a gain of function, i.e. an increased enzymatic activity, due to enhanced trypsinogen auto-activation [23]. Since the Ala-Arg117 bond is the primary and physiologically relevant autolysis site in trypsin-1, it prevents premature activation in the pancreas and, consequently, the Arg117His mutation with the disfavored P1-His increases the stability of the active enzyme [24]. Other rare mutations lie either within the propeptide of trypsinogen (Ala8Val, Asp11Ala, Asp14Gly, Lys15Arg) or within the mature enzyme (Asn29Thr, Asn29Ile) and tend to an increased auto-activation [25].

2.1.2. Chymotrypsins

Similar to trypsin, chymotrypsin can be considered as the second prototype of the family S1 proteases, in particular, since the first crystal structure of a protease came from bovine chymotrypsin A [2]. However, chymotrypsin A (S01.001, EC 3.4.21.1),) is restricted to cattle, while chymotrypsin B (S01.152) is found in most vertebrates (Fig. 2C). Both share a distinct specificity for P1-Phe, -Tyr, -Trp and other large hydrophobic side-chains, while chymotrypsin A cleaves P1-Trp substrates significantly faster than the B type. Chymotrypsin C (S01.157), with a pronounced preference for P1-Leu residues, adopts an intermediate position between chymotrypsin A/B and elastases, which do not accept large hydrophobic residues [26]. Seemingly, properly active chymotrypsin C (CTRC) can degrade trypsins, which reduces the risk of pancreatitis, and it exhibits, in contrast to most other digestive proteases, N-glycosylation at three Asn residues, which is important for folding and stability. The major function is degradation of trypsin-1 in the pancreas, which is triggered by cleavage between Leu81 and Glu82 in the Ca2+ binding loop of trypsin, however, in addition, an autolytic cleavage of trypsin between the Arg–Val118 peptide bond is required [27]. A secondary function of CTRC is cleavage at the Phe-Asp11 bond of trypsinogen, resulting in the removal of a tripeptide which is accompanied by a 3-fold stimulation of trypsinogen activation and a positive feedback loop, since trypsin activates CTRC as well [25].

2.1.3. Elastases

The name elastase derives from their substrate, the elastic fiber protein elastin with a high content of Ala and Val. Although the specificity of some elastases may overlap with chymotrypsins, they prefer small hydrophobic side-chains, such as Ala, Val or Ile and accept Thr and Asn (Fig. 2C). Despite the name pancreatic elastase I (PE I, S01.153, EC 3.4.21.36), it is mainly expressed in human skin, in contrast to its expression in the pancreas of other mammals, while the major human pancreatic elastases are PE II and PE III, both present as A and B isoforms [28]. Overall, the digestive trypsin-like serine proteases appear to be compact, with short and rigid loops around the active site, which in case of trypsin is further stabilized by Ca2+ binding in the 75 or 70-80 loop, resulting in rather unspecific, promiscuous binding of substrates and rapid turnover (Fig. 2C).

2.2. Blood coagulation factors and fibrinolysis

Enzyme cascades for the activation of serine proteases have been found in insect embryogenesis, in the primordial coagulation system of arthropods, and in the complement system and blood coagulation of vertebrates [29]. Early in evolution a system existed similar to the hemolymph coagulation of invertebrates and diverged about 450 million years ago into the blood coagulation cascade and the innate immune response or complement system [30]. During blood coagulation injured blood vessels are sealed by the intrinsic “contact activation” pathway and the extrinsic “tissue factor” pathway resulting in the prothrombinase complex of the common pathway. This complex activates thrombin, which cleaves fibrinogen to fibrin that forms clots around platelet plugs [31]. In contrast to most digestive enzymes, coagulation factors comprise additional domains in a mosaic-like architecture and are highly specific for a very small number of physiological substrates, with a tight control of activation and activity by cofactors and inhibitors, including complex regulatory feedback loops (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3. Trypsin-like proteases in blood coagulation and fibrinolysis.

3A: Scheme of the blood coagulation system. Intrinsic and extrinsic pathways lead to the common pathway with thrombin as central protease that cleaves fibrinogen monomers, which assemble to fibrin polymers. The protease activation cascades include active tryptic proteases (red), non-protease regulators participate (white), and the crosslinking transglutaminase fXIIIa (grey). Plasmin removes fibrin clots for restoring blood vessels. 3B: Regulation of blood coagulation depends on distinct conformational changes of the active site loops, such as in fXII, whose zymogen conformation involves allostery of the N-terminus with the undefined 189- and 220- loops (dots) (4XE4 [34]). The color scheme for the loops corresponds to Figs. 1C and 1D, e.g. the 99-loop is depicted yellow, the 75-loop is green, etc. 3C: A comparison of fIXa with and without Ca2+ bound in the 75-loop (green) confirmed an allosteric communication line (arrow) to the N-terminus and the 189-loop (pink) (2WPI [40]); same color scheme as in Fig. 3B. 3D: A complex of snake venom homologs is a good model of the fVa-fXa complex or prothrombinase, and resembles the Xase complex of fVIIIa-fIXa (4BXS [47]). The crucial interaction is between the A2 domain (green) and the c175-loop (orange), resulting in an open “unlocked” conformation of the protease. 3E: Bovine thrombin depicted with electrostatic surface potential and fibrinogen peptide bound to the active site (1UCY [292]). Two anion binding exosites mediate interactions with various substrates and regulators. 3F: The structure of full-length plasminogen type II (4DUR [79]) reveals the arrangement of the five kringle domains (various colors), which contribute to fibrin clot and receptor binding. The N-terminal PAp domain (blue) maintains the closed and inactive conformation, as well as the unprocessed propeptide (black), while the catalytic domain (white) is in the zymogen state (catalytic triad residues shown as spheres).

2.2.1. Factors XII and XI

Most coagulation factors are produced in the liver, such as the proenzyme factor XII (fXII, Hageman factor), which is activated to the trypsin-like protease fXIIa by contact with neutral or negatively charged surfaces of natural or artificial origin, in particular during injury of blood vessels [32]. Thus, mature fXIIa starts the enzyme cascade of the intrinsic pathway, enhanced by binding to high molecular weight kininogen and plasma kallikrein, which can activate fXII as well [33]. Factor XII comprises 596 residues with the so-called N-terminal heavy chain and the light chain of the catalytic domain, in which the new N-terminus Val354 (c16 in chymotrypsinogen numbering for the catalytic domain) forms a salt bridge to Asp543 (c194) next to the catalytic Ser544 (c195), whereby both chains remain connected via a disulfide. The heavy chain contains fibronectin II, epidermal-growth factor-like (EGF-like), fibronectin I, another EGF-like, kringle and Pro-rich domains, which mediate binding of fXI, Zn2+, fibrin and heparin, as well as of artificial surfaces. To date, the structure of the mature active catalytic domain is unknown, whereas a construct with the two additional N-terminal residues Ser-Arg353 resulted in a zymogen conformation, lacking a properly formed oxyanion hole and disordered 189- and 220-loops around a distorted S1 pocket (Fig. 3B) [34].

Factor XI is the major substrate of fXII with a different multidomain “mosaic” pattern more similar to plasma kallikrein, exhibiting four apple domains (A1-4) of about 90 residues in the N-terminal heavy chain, whereby A4 provides interacting regions within a disulfide linked homodimer. Cleavage of the Arg-Ile370 bond by fXIIa, thrombin and auto-activation generates a trypsin-like N-terminus [35]. The catalytic domain exhibits significant insertions in the 37- and 60-loops, with Arg37d and Tyr59a contributing to specificity for residues P2´ to P5´, such as in the interaction with the physiological inhibitor protease nexin 2 [36]. Factor XI is encoded on chromosome 4, and genetic deficiencies lead to the recessive bleeding disorder hemophilia C, also known as Rosenthal syndrome, which for gynecological reasons affects more women than men. Hemophilia C does usually not lead to spontaneous bleeding, but can result in excessive blood loss by physical traumata or surgery [37].

2.2.2. Factors IX, X, and VII

The architecture of factors IX and X from the intrinsic pathway differs significantly from fXII and fXI, comprising two EGF-like domains and an N-terminal Gla domain, which contains up to 12 γ-carboxyglutamates, forming four Ca2+ and four Mg2+ sites that allow for binding phospholipids of vascular cell membranes [38]. Gla domain mediated binding of coagulation factors is essential for their localized and highly efficient activity [39]. Full activation of fIX requires the stepwise cleavage at the Arg-Ala146 and Arg-Val181 (c16) bonds, with a complete excision of the stretch Ala146-Arg180. In the catalytic domain of fIX, Glu388 (c219) distorts the S1 pocket and reduces the activity with respect to most other trypsin-like proteases that possess a Gly219, while mutants, such as Glu388Thr are more than 1000-fold active [40, 41]. The stimulatory effect of Ca2+ binding for the activity of the catalytic fIX domain was explained by a conformational communication line from the 75-loop via the Ile16-Asp194 salt bridge to the Cys191-Cys220 stretch, including the catalytic Ser195 and the oxyanion hole (Fig. 3C).

Activation of fX by fIX depends on Ca2+, phospholipids and fVIIIa, a non-protease enhancer of fIXa activity, which can increase Vmax more than 10,000-fold, once the “tenase (Xase)” complex has formed. Most likely, binding of fVIIIa rearranges the 99-loop with Tyr266 (c99) as a particularly critical residue, which can rotate from the S2 into the S4 subsite upon binding of larger P2 side-chains from substrates [42]. Binding of fVIIIa to fIXa opens the “locked” conformation of Tyr345 (c177) on the non-prime side, while the blocking Lys265 (c98) side-chain has to be pushed away by the substrate segment of fX [43]. The hereditary disease hemophilia centers on fIX and its cofactor VIII. The genetic deficiency of fVIII was termed hemophilia A (HA), while the corresponding deficiency of fIX was termed hemophilia B (HB) or “Christmas disease”, which can be both treated by regular injections of the recombinant factors VIII or IX [44]. As both genes are located on the X chromosome, the frequency in males is about 0.02% (HA) and 0.003% (HB), while both are extremely rare in women and heterozygous female carriers show usually only mild symptoms [45].

Resembling its activator fIX from the intrinsic pathway, fX (Stuart-Prower factor) is activated by excision of an activation peptide at the Arg-Ile195 (c16) bond, in order to form the salt bridge with Asp378 (c194), requiring Ca2+, phospholipids, and the non-protease cofactor fVa, to form the so-called prothrombinase complex, which converts prothrombin into active thrombin [46]. Typically, the phospholipids are located on vesicles from activated platelets, whereby in positive feedback loops, fX is capable of activating fVIII, fV, and fVII. First insights into the architecture of the prothrombinase complex were gained by a fX-fV complex from the venom of the Australian Eastern Brown Snake (Pseudonaja textilis) [47]. Besides interactions of the EGF2 domain of fX and the A3 domain of fV, a major interaction site is the 175-loop of the catalytic domain with the A2 domain that might be a parallel to the “unlocking” of fIX (Fig. 3D).

In addition, fVIIa in complex with the non-protease, membrane-anchored tissue factor (TF, thromboplastin) can generate fXa by cleavage of the Arg-Ile153 bond [48]. Essentially, the overall architecture of fVII is the same as in fIX and fX, with one Gla- and two EGF-like domains, whereas its activation does require only a single cut at Arg-Ile195. Factor VII can auto-activate and activate factors IX, V and VIII, while hyaluron binding protease (HABP, FASP) activates fVII as well and cleaves the tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI), thus, accelerating the coagulation cascade [49, 50]. Apparently, fVIIa is the only coagulation factor that is inhibited by Zn2+, which binds to the otherwise Ca2+ binding 75-loop [51]. However, this loop of fVII is capable to bind Ca2+, while two Zn2+ ions bind Lys24, Asp79 and His117 or His76 and Glu80 [52].

2.2.3. Thrombin and protein C

Thrombin (α-thrombin, fibrinogenase, fIIa), the central trypsin-like protease of blood coagulation, cleaves fibrinogen, resulting in fibrin clots, which stop blood loss through injured vessels (Figs. 3A, E). The specificity for the fibrinogen cleavage sites has been structurally elucidated with GVR-GPR as one of the preferred P3 to P3′ sequences [53]. Furthermore thrombin activates fXIII, a transglutaminase, which cross-links Glu and Lys side-chains, in order to render fibrin clots more stable. In addition, thrombin cleaves protease-activated receptor 1 (PAR-1), resulting in the aggregation of platelets (thrombocytes), which clump at vessel injuries supported by the von Willebrand factor (VWF) [54]. Furthermore, thrombin amplifies prothrombin activation in a positive feedback loop by activation of the fIXa and fXa cofactors fVIII and fV [55].

Prothrombin is membrane-bound via an N-terminal Gla domain, followed by two kringle domains. Cleavage at Arg-Ile321 (c16) by prothrombinase (fXa/Va) generates the intermediate meizothrombin, while a second cleavage at Arg-Thr272 releases active α-thrombin, fIIa [56]. Besides the A-glycosylation at cAsn61, the remarkable insertion of nine residues in the 60-loop covers the active site like a lid and shields it from less specific protein substrates [57, 58]. A unique Na+ binding site in the 220-loop enables the transition from “slow” to “fast” thrombin, with formation of the salt bridge cAsp222-cArg187 and the ideal conformation of cAsp189 and cSer195 for substrate recognition and turnover [59, 60]. In contrast to most other coagulation factor proteases, which require Ca2+ binding in the 75-loop for maximum activity, cLys70 precludes such additional stimulation. Regarding the molecular mechanism of substrate binding and turnover, thrombin has served as paragon for the conformational selection mechanism, with an open E and a closed E* conformation, depending mostly on movements of the 220-loop [61]. The anticoagulant effect of the glycosamine heparin is achieved by binding of sulfonic acid groups to the positively charged exosite II of thrombin, which facilitates complex formation with the serpin inhibitor antithrombin III [62]. The dual procoagulant and anticoagulant functions of thrombin were attributed to distinct interactions with either exosite I or II, whereby the electrostatic interactions were only required for the anticoagulant effects [63]. Infections with bacteria from the genus Staphylococus can induce blood clotting by insertion of the N-terminal segment IVTK of staphylocoagulase into the activation pocket of prethrombin-2, with formation of the salt-bridge to cAsp194 and a conformational switch to an active zymogen thrombin species [64].

Activation of protein C, the terminator of blood coagulation, depends on Ca2+ binding in the 75-loop and a specificity switch in thrombin induced by thrombomodulin binding, via the anion binding exosite I in the 37-, 60- and 75-loops [65]. This switch changes the substrate specificity of thrombin from rather basic residues in P3 and P3′ to acceptance of Glu in these positions [66]. Protein C (APC) is a trypsin-like serine protease with an N-terminal Gla domain and two EGF-like domains, whose activity is enhanced by the non-protease protein S and intact fV, while its 60-loop seems to partially block access to the active site [67, 68]. Its exosite I is more extended than the one of thrombin, comprising the 148-loop as important binding region for fVIII [69]. The anticoagulant effects of protein C are achieved by multiple cleavages in fVIIIa and fVa, which suffices to shut down blood coagulation, however, natural mutations of fV, such as Arg506Gln, confer resistance to cleavage by protein C [70].

2.2.4. The plasminogen activators uPA, tPA and plasmin

According to its function in the lysis of fibrin clots, plasmin was originally called fibrinolysin, requiring urokinase-type and tissue-type plasminogen activators (uPA and tPA), which are both highly specific trypsin-like serine proteases as their substrate [71]. Originally isolated from urine as “urokinase”, uPA circulates mostly in blood plasma as zymogen pro-uPA, which is also termed single-chain uPA (sc-uPA) to distinguish it from the active two-chain form (tc-uPA). Various serine proteases, including plasmin, can cleave at the Lys-Ile159 bond of uPA, which has an N-terminal kringle and an EGF-like and domain. By contrast, a FN1-like domain precedes the EGF-like, followed by two kringle domains in tPA. The plasminogen cleavage site CPGR-V(c16)VGG does not represent an optimal recognition sequence for uPA or tPA, which prefer SGR-SA or even YGR-SA, respectively [72]. EGF-like domain mediated binding of uPA to the membrane-anchored uPA receptor (uPAR) is an important activation and regulation cycle, which allows binding of inactive uPA forms or fragments, facilitated by increasing encounters when plasminogen is bound to fibrin at cell surfaces [73]. In addition, activation of plasminogen and inhibition of uPA in the receptor bound state play a role in pathophysiological conditions, such as tumor cell migration.

Both uPA and tPA exhibit insertions in nearly all surface loops with respect to chymotrypsin, such as 37a-d, 60a-c, 110a-d, and 186a-b or 186a-h, which contribute to a limited acceptance of other substrates, but increase the specificity for plasminogen [74]. Remarkably, the zymogen sc-tPA can adopt an active state, enhanced by fibrin binding, when Lys429 (c156) forms a salt bridge to Asp477 (c194), although the properly activated variant with Ile276 (c16) is much more active [75]. The loop extensions of uPA and tPA influence mainly the prime side region and confer the high specificity for the only substrate plasminogen, whereas the extended 37- and 60-loop act as special mediators of inhibition by the serpin PAI-1 [76]. Arg399 (c70) replaces a conserved Glu70 of most trypsin-like proteases and prevents very efficiently Ca2+ binding [77].

Plasminogen features a unique zymogen conformation with a hydrogen-bond from His586 (c40) to Asp740 (c194), precluding formation of the oxyanion hole and the S1 pocket, which is occupied by Trp761 (c215) (Fig. 3F) [78]. Mature plasmin comprises nearly 800 residues, after cleavage by either uPA or tPA at the Arg-Val562 bond and a second cleavage of the Lys-Lys78 bond by plasmin itself [79]. The heavy chain (78-561) comprises five kringle domains (80 residues) and remains covalently linked by two disulfides to the protease domain with the catalytic Ser741 (c195). Varying cleavage events generate other variants of plasmin, e.g. the “microplasmin” protease without kringle domains. Plasmin degrades fibrin clots by cleaving preferentially after P1-Lys and -Arg, exhibiting the unique feature of the so-called 94-shunt, a six residue deletion of the 99-loop, which is the basis of a high substrate promiscuity in the large S2 pocket [80]. The physiological inhibitor of plasmin is the serpin α2-antiplasmin, whereas aprotinin (bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor or “Trasylol”) had been used to prevent bleeding during surgery until around 2008 [81]. Additional functions of plasmin have been reported in inflammation, angiogenesis, wound healing, and in tumor growth. In order to enhance blood clot degradation by plasminogen activation, bacterial streptokinase or staphylokinase are employed in medical applications, displaying a similar activation mode as staphylocoagulase with thrombin [64, 82].

2.3. Serine proteases in the immune response

2.3.1. Complement system pathway overview

The complement system is a more than 550 million years old part of the innate immune response, resulting in pathogen lysis or phagocytosis [83]. Primordial organisms like horse shoe crabs with a hemolymph possess a simple version that combines blood coagulation and innate immune response [84]. The mammalian complement comprises eight trypsin-like proteases, various cofactors and pore forming proteins of the membrane attack complex (MAC), which are mostly expressed in the liver and interact with blood coagulation factors and kallikreins [85, 86]. Besides the classical and alternative pathways, additional pathways require lectins, macrophages and polymorphonuclear leukocytes or activated thrombin, that all result in the opsonization, a marking of target cells, and their recognition by complement receptors of immune cells for phagocytosis as well as in MAC formation for cytotoxic processes [87]. A simplified overview of the complicated network is displayed in Fig. 4A [88].

Figure 4. Trypsin-like proteases of the complement system.

4A: Scheme of the complement cascade and the three major pathways. The classical pathway involves proteases C1r and C1s, which activate the C2a component of the C3 convertase. C2a forms the protease component of the C5 convertase as well. The lectin pathway is initiated by mannan binding lectin (MBL) or ficolin, whereby the complex with the MASP proteases generates the C3 convertase C4bC2a. The alternative pathway generates the C5 convertase with factors CD and CB corresponding functionally to C1s and C2. Proteases are displayed red, thioesterase complexes black, and other protein cofactors white. All pathways are more complicated due to complement receptors, additional functions of cleavage products and various interconnections [88]. 4B: The MASP2-C4 Michaelis complex as example of the initiating step of the cascade (4FXG [175]). The trypsin-like protease domain with additional domains is shown in red shades, while the substrate C4 domains are shown in green and yellow. The active site bound segment and the catalytic triad residues are shown as spheres. Except for the alternative pathway, interaction of the serine protease with pathogen binding molecules is required. 4C: Factor C2a, the protease component of the C3 and C5 convertase of the classical pathway, consists of a serine protease domain (white), with many alterations compared to trypsin, and a regulatory VWA domain (green). The regulator helix α7 (dark green) sits at the domain interface with an N-glycan (spheres) at the linker (black) and can together with helix α1 switch to an active, open conformation (2I6Q and 2I6S [99]). Active C2a is still in a partial zymogen-like state, due to the flipped peptide of Lys656-Gly657 of the oxyanion hole, albeit activated by the unusual salt bridge of Arg696 (c224) in the 220-loop (purple) to Glu658 (c194). 4D: Factor CI, a major control element of the complement cascades circulates as active protease, although in a zymogen-like state, as corroborated by a largely disordered N-terminal segment up to residue 325 (c19), including the 75- (green), 148- (brown), 189- (pink), and 220-loops (magenta), which are depicted with their defined residues as spheres, like His57 (2XRC [103]). By contrast, the N-terminal FIMAC, LDLRA1/2 and SRCR domains, which mediate contact to the major substrate C3b, are well defined. 4E: Factor CB structure with three N-terminal sushi or CCP domains (labeled 1 to 3), which require cleavage at the Arg234-Lys235 bond for activation (2OK5 [108]). Active CBb of the alternative pathway resembles largely factor C2a, with a regulatory VWA domain and similar characteristics of the active site, including the unusual salt bridge (c224-c194) and the same oxyanion hole conformation.

The “classical” pathway is initiated by pathogen antigens binding to IgG or IgM antibodies and subsequent recognition by complement factor C1q, which activates the serine protease C1r, followed by activation of the related protease C1s [89]. C1s cleaves factor C4 into the anaphylatoxins C4a/b, as well as C2 into C2a/b, with the protease component C2a, which form the C3 convertase complex C4b2a that cleaves factor C3 into C3a/b, subsequently forming the C5 convertase C4b2a3b. Similar to C4b, the C5 convertase subunit C3b binds covalently to hydroxyl groups of carbohydrates on pathogen surfaces by a thiol nucleophile from a thioester, a central event of complement dependent opsonization [90]. Eventually C4b2a3b cleaves C5, resulting in C5b/6/7/8/poly-9, the pore-forming MAC, which lyzes pathogen cells [89].

The lectin pathway, depends on the mannan-binding lectin-associated serine proteases (MASP), resembling largely the C1r/s proteases. MASP-1 and MASP-2 are mainly activated by complex formation with mannose bound mannan-binding lectin (MBL) on pathogens and generate the C3 convertase C4b2a similar to the active C1 complex (Fig. 4B). In addition, the three human ficolins M, L and H are capable of MASP activation. In the alternative pathway, complement factor B replaces the homologous protease component of C2 in the C3 and C5 convertase complexes, while factor D corresponds to protease C1s of the classical pathway and cleaves factor B in complex with factor C3b, resulting in the C3bBb complex and subsequently in the C3 convertase. Complement protease CI controls all these pathways, since it is able to inactivate the essential C3 and C5 convertase components C3b and C4b to C3i and C4i in the presence of cofactors, such as factor H, C4b-binding protein, complement receptor 1 or CD46 [91].

2.3.2. Complement proteases of the classical pathway

The initiator protease of the classical pathway, C1r, forms a homodimer and comprises 688 amino acids, with two N-terminal CUB domains, an EGF-like domain and two complement control protein (CCP) or sushi domains [92, 93]. Upon IgG/M binding in the inactive, Ca2+ stabilized C1qC1r2C1s2complex, C1r auto-activates by liberation of the N-terminal Ile446 (c16) and subsequently cleaves the zymogen C1s [94]. C1s has the same modular domain structure as C1r and remains in the C1 complex with C1q and C1r once it is activated by release of Ile423 (c16), cleaving the substrates C2 and C4 at Arg-Lys and Arg-Ala bonds, which form the complex C4b2a protease. Recent structural studies indicate that the C1 complex is activated via intermolecular events and that six Ca2+ binding sites in the CUB-EGF-CUB domain segment contribute to the stabilization of the C1r-C1s heterodimer subunits [95, 96]. Homozygous genetic deficiency in C1q is strongly associated with developing the autoimmune disease systemic lupus erythematosus, while C1r or C1s-deficienct patients experience recurrent bacterial, viral, and fungal infections combined with severe cutaneous lesions [97].

The C3 convertase (C4b2a) cleaves C3 into C3a and C3b, which assembles with the C3 convertase to the C5 convertase C4b2a3b [89]. Factor C2 is composed of C2a with the catalytic domain and one von Willebrand factor A-type domain (VWA), whereas the three N-terminal sushi (CCP) domains are cleaved off for activation by C1r [98]. Active C2a exhibits some remarkable differences to the common trypsin-like proteases. Apart from the Mg2+ requiring complex formation with C4b, mediated by the metal ion-dependent adhesion site (MIDAS) of the VWA domain in an open conformation, the activation domain is stabilized by a salt bridge of the side-chain of Arg696 in a loop 2 (220-loop) insertion to Glu658 (c194) [99]. This salt bridge is important for the oxyanion hole conformation, resembling partially a zymogen state, as the peptide plane Lys656-Gly657 (c192-193) is flipped by 180° with respect to the conformation of active trypsin (Fig. 4C). Moreover, insertions of 9, 13, and 15 residues in loops C (99), 3 (175), and 2 (220), as well as deletions of 4 and 12 residues in loops E (75) and D (148) virtually abolish the S2 and S3 specificity pockets. Thus, C2a cleaves in a highly specific manner only in the C3/5 convertase complex at Arg-Ser727 (C3) and Arg-Leu75 (C5) bonds. Individuals with homozygous complement C2 gene deficiency often do not display any obvious disease, very likely due to a factor B-mediated bypass activation of the complement. Still, about 40% of the individuals develop systemic lupus erythematosus or a lupus-like disease [100]. Furthermore, molecular variants of genes encoding C2, C3 and CI, are associated with a high risk for age-related macular degeneration [101].

CI is an atypical trypsin-like serine protease that circulates as active protease and cannot be inhibited by natural inhibitors, whereas it cleaves small synthetic substrates [102]. It exhibits a unique architecture with the FIMAC domain that enables membrane insertion, one SCRC and two LDL-receptor class A domains preceding the protease domain, which exhibits a zymogen-like active site with disordered loops 148, 191 and 220, albeit with a free N-terminus at Ile322 (c16) [103]. It has been suggested that an allosteric auto-inhibition occurs by contacts of the N-terminal heavy chain to the C-terminal helix and opposite to the active site, while activity might be substrate-induced as observed for thrombin (Fig. 4D). CI cleaves at Arg-Thr/Ser/Asn/Glu bonds, whereby changes in specificity depend on the cofactors [104]. Under certain conditions CI activity can result in phagocytosis instead of lysis of pathogens.

2.3.3. Complement proteases of the lectin and the alternative pathway

For MASP-1 some parallels to thrombin have been described, in particular heparin binding and a more accessible active site than in the self-inhibited factor D, despite a similar salt bridge between Asp640 (c189) and Arg677 (c224) [105]. As thrombin, pro-MASP-2 displays a significant zymogen activity, which may depend on the similarly extended 60-loop, while its substrate specificity is nearly identical to that of the C1 complex [106, 107]. In the alternative pathway, complement factor B essentially replaces the highly homologous C2 in the C3 and C5 convertase complexes. A full-length structure of CB comprising the three CCP or sushi domains explained the zymogen state by a closed conformation of the MIDAS motif in the VWA domain, which shields the Arg234-Lys235 bond (Fig. 4E) [108]. In addition, Arg705 as equivalent of Arg696 in factor C2a, is located more than 10 Å away from Asp673 (194), preventing an active conformation of the catalytic domain as present in factor Bb [109]. Recently, MASP-3 has been characterized as link between the lectin and alternative pathway, as it is able to activate pro-factor D, which circulates mostly as active protease in blood [110].

In the alternative pathway, factor D corresponds to C1s of the classical pathway. Pro-factor D exhibits an intact catalytic triad, but a typically distorted activation domain as observed for other zymogens [111]. Factor D is highly specific for cleaving only the Arg-Lys235 bond to activate protease factor B. The active C3bBD* complex structure revealed that the residues c213-c218 of the 220-loop adopt a self-inhibitory conformation, where Ser215 forces the catalytic His57 out of the triad [112]. In addition, Arg218 forms a salt-bridge to Asp189 in the self-inhibited state. Binding to the substrate C3bB is mediated by a positively charged exosite of factor D, consisting of loops D and 1 to 3, which essentially correspond to the 148-, 175-, 191-, and 220-loops. Very low blood plasma-concentrations of factor D define its role as rate-limiting enzyme of the alternative pathway and the loss of complement activation in CD deficiency increases the susceptibility to invasive meningococcal disease [113]. By contrast, increased levels of CD in age-related macular degeneration make it a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of this disease and its advanced form geographic atrophy [114].

2.3.4. Neutrophil serine proteases

Neutrophil elastase or leukocyte elastase (HNE or HLE) is present as mature protease in storage “azurophil” granules of polymorphonuclear neutrophils (blood), together with myeloblastin/proteinase 3 [115]. Their major task is killing pathogens, such as phagocytosed bacteria, and regulating inflammatory processes together with other neutrophil serine proteases. HNE and proteinase 3 (PR3), also named myeloblastin, participate with histones, antimicrobial peptides and DNA fibers in so-called neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), which catch and kill bacteria and fungi. Both proteases prefer Val, Thr, Ala or Met in P1 position, which can be explained by the unusual Gly189/Val190 or Ile190 combinations, whereby variations in the loops, such as Asp61 and Lys99 confer a distinct substrate specificity for basic P1′ and acidic P2 residues [116]. An inhibitor complex structure of HNE showed that only two of the three known N-glycosylation sites at Asn72, 109, and 159 were occupied, which, nevertheless are important for the interaction with the physiological inhibitor α1-antitrypsin [117]. PR3 can cleave cathelicidin and thereby generate the antimicrobial peptide LL-37, activates tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-β (IL-β) and transforming growth factor β (TGF- β). A non-protease homolog of PR3 is azurocidin, without catalytic triad, due to the mutations His57Ser and Ser201Gly, while it alarms and enhances the immune system and its response, respectively [118, 119].

Like HNE and PR3, cathepsin G (CG) from neutrophils contributes to killing microbes in phagosomes. CG is a chymotryptic protease with a preference for P1-Phe, while P1-Lys can be turned over due to the presence of Glu226, similar as in chymase from rat mast cells [120]. An unusual structural feature is the missing disulfide Cys191-Cys220, which is otherwise highly conserved, and the rather hydrophobic combination of Ala189/Ala190. Regarding the loops, HNE exhibits a three residue insertion in the 37-loop, whereas CG has such an insertion in the 60-loop. According to the architecture of the S1 subsite, HNE and PR3 are more chymotrypsin-like, whereas CG has a mixed specificity cleaving after large, hydrophobic and basic amino acids [115]. The fourth member of the neutrophil serine protease family, NSP4, displays similar to HNE and PR3 a Gly189/Phe190 combination in the S1 pocket [121]. Although NSP4 shows an elastase-like active site, it is trypsin-like with a preference for P1-Arg. Its low abundance in neutrophils suggests a more regulatory role in the innate immune reactions, instead of digesting mostly bacterial proteins [121, 122]. The physiological activity of neutrophil serine proteases is tightly controlled by α1-protease inhibitor, α2-macroglobulin, secretory leucoprotease inhibitor (SLPI), and elafin to maintain tissue homeostasis. However, unbalanced protease activity can cause serious inflammatory lung diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and cystic fibrosis [115].

2.3.5. Serine proteases from mast cells

Human mast cells belong to the immune system, defending the host against intruding pathogens, such as bacteria and parasites, with chymotryptic chymases and tryptic tryptases as prominent serine proteases, and other proteases that are stored as zymogens in secretory granules, which release their content when immune signals initiate degranulation [123]. Chymase, an α-chymase, is the only human member of these specialized serine proteases, which are more diversified and better characterized in rodents, with up to five different α- and β-chymases [124].

Four human tryptases are known: α-tryptase (tryptase alpha 1) prefers P1-Lys over P1-Arg, like β-tryptase (tryptase beta 1/2/3), γ-tryptase (tryptase gamma 1) favors P1-Arg, while δ-tryptase (tryptase delta 1) is inactive [125, 126]. Interestingly, α-tryptase is a constitutively secreted protease with very low activity, due to the substitution of Gly216 by Asp, whose absence in some humans has not effects on health [127]. β-tryptase is known in three isoforms, e.g. βII, which all form ring-like tetramers with the active sites located inside the water filled cavity. Tetramerization of β-tryptase is a prerequisite for its enzymatic activity and most likely the cause for resisting all known physiological inhibitors [128, 129]. Six surface loop stretches bind neighbor molecules, whereby the 60-loop and the 175-loop are extended by five and nine residues. Only γ-tryptase is anchored with a C-terminal peptide in membranes, whereas a truncation of 40 C-terminal residues renders δ-tryptase inactive [130]. Tryptases and other mast cell proteases have been implicated in a plethora of diseases, including cardio-vascular, respiratory, digestive, reproductive, nervous system disorders, and oncogenesis [123, 131].

2.3.6. Granzymes of cytotoxic T lymphocytes

The name “granzymes” derives from granules of T lymphocytes and trypsin-like enzymes, which play a role in the destruction of pathogens in blood together with the pore forming perforin [132]. The formation of large membrane pores, allows granzymes to enter the cytosol of target cells, where they initiate apoptosis, which is important in killing tumor cells [133]. To date twelve granzymes (GZM) are known, of which GZMA, -B, -H, -K, and – M are present in humans, which are usually activated by cathepsin C (DPPI) [134].

Granzyme A was described in natural killer cells (NK), lymphokine activated killer cells (LAK) as major executor of apoptosis, although its various roles in human have not been fully revealed. GZMA prefers Arg over Lys in the P1 position and forms a unique disulfide-linked homodimer via Cys93 in the 99-loop. Originally classified as chymotrypsin homolog due to the presence of Thr189, Granzyme B turned out to be one of the few trypsin-related peptidases with a primary preference for acidic residues, such as P1-Asp [135]. The different architecture of the wider S1 subsite in GZMB, which lacks the highly conserved disulfide Cys191-Cys220, results in the formation of a salt bridge from Arg226 to P1-Asp residues [136].

In contrast to GZMA and B, GZMH possesses the unique Glu14-Glu15 pro-dipeptide and exhibits a distinct chymotryptic specificity for P1-Phe, -Tyr and –Met, which can be explained by Thr189 at the bottom of the S1 pocket and a Gly226 instead of an Arg226 as in GZMB [137]. The major task of GZMH is killing target cells upon entering the cytosol and the cleavage of proteins that are critical in viral infections, e.g. in hepatitis B [138].

Besides GZMA and based on the presence of an Asp189, GZMK is the only tryptic granzyme, which equally accepts Lys and Arg in P1 position according to various scanning approaches, which related the extended specificity to the natural substrate tubulin, as present in the microtubulin network of tumor cells [139]. The fifth human granzyme, GZMM displays a preference for hydrophobic P1-residues without Cβ-branching, such as Met and Leu. This special preference can be explained by the unusual combination of Ala189-Pro190 and the presence of Ser216 instead of Gly216. Overall, the humans granzymes show no striking aberrations in the surface loops, although individual GZMs have significant insertions in the 60-loop (GZMK/M), deletions in the 75-loop (GZMM) and insertions in the 175-loop (GZMA/K). GZMA and GZMB are the major granzymes implicated in cell death processes, whereby GZMB represents the most powerful pro-apoptotic granzyme which is most likely based on the unusual preference for P1-Asp substrates, similar to caspases. GZMB-mediated cell death is rapid in contrast to a slower form of cell death, which is initiated by the tryptic GZMA in a caspase-independent pathway, called athetosis, depending on an intact actin cytoskeleton as shown in a mouse model [140].

2.4. Kallikreins and kallikrein-related peptidases (KLKs)

Basically, kallikreins and KLKs are expressed in all tissues and fluids of the human body, however, their individual tissue expression varies extremely with development, healthy or pathological conditions [141–144]. They are closely related to trypsin and the historical distinction of the classical kallikreins 1-3 and the new kallikreins 4-15 is justified by the peculiar 11 residue insertion in the 99-loop, giving rise to the name “kallikrein loop”. It is preferable to classify them according to their functional tasks, which are associated with proteolytic activation cascades (Fig. 5A) [145–147]. KLK3/PSA is the best known member of this group, since it is employed as biomarker and therapeutic target for prostate cancer. Moreover, most KLKs are implicated in cancer and other diseases, which is described in detail by several comprehensive reviews with respect to pathophysiological roles and clinical relevance [148–152]. Similarly, structure and functions have been reviewed by various research groups [153–155].

Figure 5. Kallikreins and kallikrein-related peptidases.

5A: Tissue kallikrein and plasma kallikrein KLKB are kininogen cleaving regulators of blood pressure, while the prostatic KLKs 2, 3, 4, 5, and 11 are either part of an activation cascade and/or degrade gel forming proteins to enhance sperm motility for impregnation. In brain, KLK6 and 8 participate in the regulation of glia cell and synaptic remodeling, whereas the skin related KLKs 5, 7, and 14 activate themselves and cleave cell connecting molecules for skin cell shedding. 5B: KLK2 is glycosylated at Asn95, depicted as core glycan, which favors the closed conformation of the 99-loop (yellow) with an 11-residue insertion with respect to bCTRA. KLK3 has an N-glycan linked to Asn61 (not shown) and a 99-loop, which can cover the non-prime-side from S4 to S2 like a lid, as in KLK2 (lower panel). The eKLK3 structure represents an E* form, with closed 99- (yellow), 148- (brown), 189- (pink), and 220-loops (magenta), but intact catalytic triad and Ile16-Asp194 salt bridge (1GVZ [165]), color scheme as in Figs. 1C and 1D. 5C: KLK4 exhibits a unique Zn2+ binding site that connects the 75-loop with the N-terminal segment via the ligands Glu74 and His25, with an additional cation binding Glu74* ligand from a neighbor molecule (2BDH [174]). Zn2+ binding causes a conformational change to a zymogen-like conformation of the active site via an exposed N-terminus, perhaps mediated by the disulfide Cys22-Cys157, as suggested for fVIIa. 5D: KLK5, 7, and 8 possess inhibitory Zn2+ binding sites, involving His99 and other ligands, such as His96 (2PSX and 2PSY [203]). The inhibition process is depicted in three steps: The two His side chains of the 99-loop in KLK5 are ready to bind Zn2+ in solution (1), an intermediate state with His96 and His99 bound to Zn2+ was observed for KLK5 (2). Eventually, the inactive state with a disrupted catalytic triad (3) is represented by tonin, a KLK2 ortholog from rat, where Zn2+ is bound by His57 (1TON [180]). 5E: KLK8 exhibits both a stimulatory Ca2+ binding site in the 75-loop and the aforementioned Zn2+ inhibition site in the 99-loop. Structure based molecular dynamics simulation corroborated that these loops are connected by a variant of the communication line of the coagulation factors (5MS3 [193]). Significant concerted loop movements upon Ca2+ removal with respect to the crystal structure are depicted as spheres for the 37- (red), 75- (green) and 99-loops (olive).

2.4.1. Kallikreins

In humans, tissue and plasma kallikreins reduce blood pressure by processing low and high molecular weight kininogens (LMWK, HMWK) to the vasodilators lysyl-bradykinin (kallidin) and bradykinin, hormone-like deca- and nonapeptides with additional functions in inflammation and pain (Fig. 5A) [156]. Essentially, tissue kallikrein (KLK1) belongs to the 15 membered family of the kallikrein-related peptidases (KLKs), whereas plasma kallikrein (PK, KLKB1) is only distantly related and participates in blood coagulation [143, 157].

Plasma kallikrein is mostly expressed in liver and activated in blood by coagulation factor XII, where it cleaves HMWK at the Lys-Arg bond, facilitated by the four apple domains, which are also present in fXI [143, 158]. A comparison of a ligand-free catalytic domain of human PK with an inhibitor-bound murine PK demonstrated that the conserved Glu217 in the 220-loop adopts a closed conformation, blocking the active site by a hydrogen bond to the catalytic Ser195 [159]. The physiological functions of PK are hemostasis, e.g. by activation of fXII, which in turn activates PK, inflammation and immune response, whereas a pathological deficiency leads to various cardiovascular symptoms [157].

In contrast to PK, tissue kallikrein or KLK1 is produced mostly in pancreas or kidneys and can cleave kininogens at the Met-Lys and Lys-Arg bonds, releasing lysyl-bradykinin or bradykinin from LMWK and HMWK [157]. A distinguishing feature of KLK1 is the N- and O-glycosylation at six positions, three alone in the 99-loop [160]. The structure of a recombinant ligand-free KLK1 displayed a partially disordered 99-loop with only a single short glycan linked to Asn95, while the heavy physiological glycosylation may contribute to the control of substrate turnover as in KLK2 (see below) [161].

2.4.2. Prostatic KLKs in human reproduction

Remarkably, the expression of KLKs 2, 3, 4 and 11 in the male reproductive system, including prostate, seminal fluid, and testes, where KLK5 expression is high, appears to be complementary to the expression of other KLKs in the female reproductive system, such as uterus and cervico-vaginal fluid [144]. KLK2 seems to be an auto-activating tryptic protease and is most likely the physiological activator of KLK3/PSA in seminal fluid. Both KLKs exhibit a similar propeptide with the scissile bond Arg-Ile16. Their common task is the degradation of semenogelin-1 and -2, resulting in liquefaction of the seminal clot, which is required for sperm motility prior to fertilization (Fig. 5A). Zymogen-like and mature protease conformations in crystal structures of the chymotryptic KLK3 confirm the insertion mechanism of the N-terminal amino group into the activation pocket with formation of the salt bridge to Asp194 [162]. However, the flexible kallikrein/99-loop of KLK2 and KLK3 can adopt an open or a closed conformation, which completely shields the S2 to S4 specificity pockets [163, 164]. A concerted transition of the 99-, 148-, and 220-loops in KLK2 from the closed E* to the open E-form is the best explanation for a conformational selection mechanism, similar to the situation in thrombin [61]. Horse KLK3 (eKLK3) adopts the E* form with closed 99-, 148-, 189- and 220-loops, despite an intact N-terminal salt bridge and catalytic triad [165]. The eKLK3 structure suggests that the inhibitory Zn2+ binding site of KLK2 and KLK3 is formed by His91, His101 and His233. An N-glycan linked to Asn95 of KLK2 is the crucial element in regulating the substrate access and turnover by favoring the closed conformation and protecting from cleavage (Fig. 5B) [166].

According to their substrate profiles, the tryptic proteases KLK4 and KLK11 could be additional activators of pro-KLK2 and pro-KLK3 in a corresponding proteolytic cascade,, while KLK3 and KLK11 cleave the unusual Gln-Ile16 bond of pro-KLK4 [146, 167, 168]. However, glycosylated KLK2 was the most efficient pro-KLK4 activator, not KLK3 [169]. Activation of KLK4 in other body fluids and tissues, such as developing teeth, depends most likely on matrix metalloproteinases, in particular MMP-3 and MMP-20 [170, 171]. Based on its hippocampal expression, KLK11 was named hippostasin, while the prostatic isoform-3 exhibits a 25 residue long insertion in the 60-loop, which leaves the enzyme activity intact [172].

Except for KLK11, Zn2+ inhibition at micromolar concentrations has been confirmed for the prostatic KLKs, which is in the physiological range since Zn2+ in prostatic fluid reaches millimolar concentrations [173]. KLK4 has a distinct role in enamel formation, as corroborated by the genetic disease amelogenesis imperfecta, which is characterized by malformed teeth, due to an inactive version of KLK4. Mutational analyses localized the inhibitory Zn2+ binding site for KLK2 in the kallikrein/99-loop and in KLK4 at His25 near the N-terminus and Glu74 in the 75-loop (Fig. 5C) [164, 174]. In case of KLK4, the inhibition mechanism appears to be similar as in fVIIa, in which Zn2+ bound to the 75-loop switched the mature protease to a zymogenic state with an exposed N-terminus [51]. The distantly related, trypsin-like and Zn2+-regulated acrosin is stored in sperm heads for the acrosome reaction for fusion with the ovum, featuring a positively charged N-terminal domain with patches for membrane interaction, similar to coagulation factors [175].

2.4.3. Skin derived KLKs 5, 7, and 14

Early studies designated KLK5 and KLK7 as stratum corneum tryptic and chymotryptic enzymes, referring to the primary specificity of both enzymes, with a distinct preference of KLK7 for P1-Tyr [167]. Together with the tryptic KLK14, these KLKs form a proteolytic activation cascade, which can start with pro-KLK5 auto-activation, facilitated by its 37 residue long propeptide [176]. All three KLKs degrade cell adhesion molecules in the corneodesmosomes of the corneocytes for desquamation, i.e. skin cell shedding (Fig. 5A). Dysregulation of KLK activity occurs in in Netherton syndrome and atopic dermatitis, involving mutations in the natural lymphoepithelial Kazal inhibitor-1 (LEKTI-1) [177, 178].

KLK5 possesses a specific Zn2+ binding site in the 99 loop, as observed by binding the ligands His96 and His99, similar to rat kallikrein tonin, with His57 as third ligand, explaining the inhibition by disruption of the catalytic triad (Fig. 5D) [179, 180]. Although KLK7 lacks a His96, the physiologically relevant cations Cu2+ and Zn2+ inhibit at the same position, as confirmed by the His99Ala mutant [181]. Both KLK5 and KLK7 possess shorter and more compact loops than the other KLKs, exhibiting a common positively charged area, corresponding to exosites I and II of thrombin [153]. A comparison of the free mature KLK7 (PDB 3BSQ) and an inhibitor bound structure (2QXH) suggests that both are virtually identical as in the lock-and-key model of enzymes, with a rigid, open E conformation that cannot adopt a closed E* form [181–183]. As most kallikrein-related peptidases, KLK14 is expressed in many tissues and body fluids, whereas its expression and function change in tumor tissue, such as becoming an activator of PAR-2 [184, 185]. Basically, all human KLKs have been implicated in PAR-1/2/3/4 signaling in inflammation and cancer processes [186].

2.4.4. Central nervous system KLKs 6 and 8

Mainly KLK6 and KLK8, also known as neurosin and neuropsin, are expressed in human brain. KLK6 resembles trypsin in many aspects and has a specific role in neuronal inflammation and multiple sclerosis, e.g. by degrading myelin basic protein of glial cells [187, 188]. Recently, it was demonstrated that KLK6 can remodel glial cells of the central nervous system, which can be complementary to the role of KLK8 in synaptic remodeling of hippocampus neurons (Fig. 5A)[189, 190].

Since rodent and human KLK6 and KLK8 are highly conserved, corresponding studies have contributed to the identification of neuregulin-1 or EphB as KLK8 substrates [191, 192]. KLK8 is rather unique with respect to binding stimulatory Ca2+ in the 75-loop like trypsin and inhibitory Zn2+ in the 99-loop, which was corroborated by crystal structures and a mutational analysis [193]. Additional features are N-glycosylation at Asn95 and the presence of Cys93 as in granzyme A, which dimerizes via a disulfide [194]. Similar to KLK4, molecular dynamics of KLK8 suggested that the surface loops of trypsin-like serine proteases are connected in an allosteric network (Fig. 5E) [193, 195]. Recently, an intriguing additional role of KLK8 in skin has been discovered, as elevated protease activity of KLK8 results in KLK6 activation and PAR-2 signaling, associated with rapid wound healing, while both KLK6 and 8 were coordinately expressed in ovarian cancer [196, 197]. Similar to KLK6, but in contrast to KLK8, trypsin-3 (mesotrypsin) targets PAR-1 with subsequent Ca2+ signaling in neurons, in particular in astrocytes [189, 198]. Another trypsin-like, membrane-bound “mosaic” protease, called neurotrypsin, is found from insect neurons to vertebrate brains, where it cleaves the proteoglycan agrin at motoneuron junctions for synapse formation [199, 200].

2.4.5. Other KLKs

Human KLKs 9, 10, and 12-15 have been functionally characterized to some extent, however, distinct physiological roles have not been determined for all of them, despite a very restricted tissue expression in some cases [144]. Some basic characteristics can be derived from their amino acid sequences in context with functional data: KLK9 and KLK15 may have an unusual substrate specificity, based on their S1 pocket residues Gly189 and Glu189, respectively, while KLK15 has an eight residue insertion in the 148-loop and in KLK13 the formation of a standard N-terminus requires cleavage after Phe15 or an alternative propeptide cleavage after Lys5 [173].

An eight residue insertion in the 99-loop of KLK10 resembles the classical KLKs 1 to 3, while the physiology of KLK10 is not well characterized. A role as tumor suppressor was suggested in breast, ovarian and prostate cancer, which remains controversial [201, 202]. Active human KLK10 requires a three residue longer N-terminus as the standard Ile/Val16 and cleaves with a mixed preference for basic and unbranched hydrophobic P1-side-chains [167]. Structures of ligand-free and Zn2+ bound zymogen-like KLK10 explained the inhibition by disruption of the catalytic triad, while the disordered N-terminus and 75-, 148-, and the 99-loops are connected in an allosteric network [203]. Most likely, substrate binding favors the productive active site conformation as in the induced fit model, which seems to be only a special case of the conformational selection model [204].

2.5. HtrA proteases

The high temperature requirement A (HtrA) proteases were discovered in E. coli and termed DegP, DegQ and DegS, displaying a modified elastase-like preference for P1-Val and Ile [205]. In general, DegP degrades misfolded proteins in the bacterial periplasm with the help of two PDZ domains at elevated temperatures from 37 °C on, but acts as chaperone at lower temperatures, whereby the resting state is a double trimer and the active state a 24-mer [206].

All four human HtrAs are secreted and possess a C-terminal PDZ domain, and except HtrA2, N-terminal IGFBP (insulin-like growth factor binding protein) and Kazal domains [207]. None of the additional domains is required for protease activity and both the IGFBP and Kazal domains are not functional, although HtrA4 is hardly characterized compared to the other members of the group [208]. The basic HtrA assembly is a trimer, while higher oligomers show increasing activity, in particular HtrA1 with an elastase-like specificity for P1-Thr, Val, Ala and Leu [209, 210]. Based on the N-terminal domain insertions, the catalytic triad residues of HtrA1 are His220 (c57), Asp250 (c102) and Ser328 (c195), whereby a stabilizing salt-bridge to the N-terminus is missing. PDZ-mediated substrate binding induces an active conformation of the triad, requiring the concerted opening of the three disordered loops L1 (323-327, 191-loop), L2 (348-351, 220-loop) and L3 (307-316, 175-loop), a sensor for allosteric activation (Fig. 6) [14, 211].

Figure 6. Various trypsin-like serine proteases with allosteric loop networks. Significant loops are labeled.

6A: Human HtrA1 displays a zymogen-like conformation with a highly disordered region around the 175-loop (L3), since it misses an N-terminal activating salt bridge. Trimerization and substrate binding induce conformational changes, including the 189- and 220-loops (L1 and L2) and the catalytic triad (3NWU, 3NZI [211]). 6B: Matriptase of the TMPRSS family is a membrane anchored protease related to enterokinase. A locked zymogen mutant Arg614Ala (c15) displays 3% activity, due to a missing activating salt bridge to the N-terminus, as well as closed 148-, 175-, and 220-loops (transparent surfaces), while the mature protease adopts standard conformations (cartoon representation) (1EAX, 5LYO [227, 293]). 6C: Streptogrisin B from a fungus represents a minimal version of trypsin-like serine proteases with only 186 residues. It contains extremely short loops with respect to trypsin, while only the 189- and 220-loops reach standard lengths (1DS2 [294]).

Mitochondrial HtrA2 is elastase-like, but favors P1-Leu and disfavors P1-Ala in degradome analyses, which lead to the identification of actin and tubulin as substrates [212].

Access to the active site is hindered by the L1 (191) and LD (148) loops, the latter being the major regulator through interaction with the PDZ domain [213]. Secreted HtrA3 exists in two isoforms, the shorter one lacks the PDZ domain and presumably remodels the extracellular matrix, with loop B (LB, c60) as the dominating regulator [214, 215]. HtrA1 and HtrA3 are involved in embryo implantation, but dysregulation of HtrA1, 2 or 3 is associated with many diseases, such as cancer, arthritis, neurodegeneration, and age-related macular degeneration [216]. For example, biallelic mutations in the HtrA1 gene cause the cerebral small vessel disease CARASIL and both HtrA1 and HtrA2 participate in programmed cell death, either in apoptosis or in anoikis, which is induced in anchorage-dependent cells upon detachment from the surrounding matrix, whereas dysfunctional HtrA2 has been linked to Parkinson's and Alzheimer's disease [217–219]. HtrA3 was identified as pregnancy-related serine protease, but is also expressed in heart, ovary and testis, and is an indicator of early-onset preeclampsia, similar to HtrA4, which is restricted to the placenta [220, 221].

2.6. Membrane anchored serine proteases

About 20 membrane anchored serine proteases fulfill a variety of important tasks in the human body [222, 223]. They have gained interest due to their physiological functions, and emerging roles in protease-mediated signaling of cancer [224]. The prominent example of enteropeptidase, belonging to the hepsin/TMPRSS subfamily, has already been described in the context of digestive enzyme activation cascades (section 2.1.). Hepsin and the other members of the subfamily, such as epitheliasin (TMPRSS2) consist of an N-terminal membrane-spanning domain, a LDLRA domain and a protease domain. Hepsin can activate several proteases from the blood coagulation cascade and seems to play a special role in prostate cancer [225]. Corin is expressed in heart and uterus; it regulates salt levels and blood pressure, with mutated forms contributing to preeclampsia, and it exhibits a complicated mosaic architecture with TM, Fz1 (frizzle-like), LDLR1-5, Fz2, LDLR6-8, and protease domains [226].

Matriptase is a tryptic transmembrane mosaic protease that is important for epidermal barrier function. The “zymogen locked” mutant Arg614Ala (c15) displays a zymogen activity around 3= of the mature protease, corresponding to a zymogenicity factor of 33, which was explained by a distorted oxyanion hole and S1 subsite, as well as by closed conformations of the 148-, 175-, and 220-loops (Fig. 6B) [227]. The closely related matriptase-2 controls the iron levels in blood, but is largely uncharacterized as matriptase-3 and the polyserases with up to three protease domains within a single polypeptide [228, 229].

DESC1-4, HAT-like 1, 4, and 5 are related trypsin-like transmembrane proteases, as exemplified by the structure of the catalytic domain of DESC1, resembling trypsin, enteropeptidase, hepsin and matriptase, with a typical S1 subsite that was also compared to active thrombin [230]. Most of the membrane-anchored serine proteases are type II transmembrane proteases, whereas γ-tryptase is the only member encompassing a C-terminal type I transmembrane domain; testisin and prostasin are membrane-anchored via C-terminal glycophospatidylinositol (GPI) segments, with a restricted expression in testes and potential roles in prostate cancer involving PAR signaling [231, 232]. Prostasin and the soluble hepatocyte growth factor activator (HGFA) can switch between open and closed states, depending mostly on the 220-loop, similar to the E and E* forms of α-thrombin [233].

Dysregulated expression of several membrane-anchored proteases, especially hepsin, TMPRSS2, matriptase, testisin and prostasin, is linked to carcinogenesis, since increased levels of them in relation to their endogenous inhibitors are associated with poor patient prognosis [224]. The oncogenic activity mediated by these proteases may depend on their role as proteolytic modifiers of growth factors and protease-activated receptors, especially PAR-2, rather than representing extracellular matrix protein degrading enzymes [234].

2.7. Serine proteases as toxins and allergens

2.7.1. Reptilian and mammalian trypsin-like protease toxins

Many snake venoms contain metalloproteases (SVMPs), which can be the dominating toxin, or even more frequently serine protease toxins (SVSPs), which often interfere with the blood coagulation system [235, 236]. Several pit vipers produce venoms that contain thrombin-like serine proteases, such as venombin A and venombin AB (gabonase), which cleave fibrinogen and even activate the cross-linking transglutaminase fXIII [237]. Russell's viper venom factor V activator (RVV-V) from the South Asian Daboia russelii is another example of a thrombin-like protease, in which the Ser-Trp-Gly216 stretch is replaced by Ala-Gly-Gly199 (c216). Scutelarin from the Australian taipan (Oxyuranus scutellatus) is a multidomain activator of prothrombin with fXa/fVa-like domains, whereas the plateletaggregating endopeptidase from the South American pit viper Bothrops jararaca activates PAR-1 on platelets like thrombin and its protease A degrades fibrin and fibrinogen [238, 239].

By contrast, mammalian toxins are rare, with the notable exception of the short-tailed shrew (Blarina brevicauda), which produces blarina toxin (BLTX) in the submaxillary and sublingual glands, a venom that is lethal for mice and share 53% identical residues with human tissue kallikrein [240]. Similar to the gila toxin from lizards of the genus Heloderma, blarina toxin cleaves like a kininogenase LMWK and HMWK, exhibiting more positively charged residues around the active site and a unique 21 residue insertion in the 99-loop compared with the 11 residue insertion of KLK1 [241].

2.7.2. Allergenic trypsin-like proteases from mites and cockroaches

Aerosolized proteins from animal sources, e.g. arthropod feces, are a worldwide health problem, affecting around 10% of humans with symptoms of allergy or atopic dermatitis. Among these allergens are several proteases, in particular trypsin-like serine proteases [242]. House dust mites, such as Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus or farinae and Euroglyphus maynei produce the cysteine protease Der p 1 (or Der f 3 and Eur m 3), which activates the serine proteases Der p 3, 6 and 9 [243]. Der p 3 exhibits tryptic and Der p 6 chymotryptic specificity, while the collagenolytic Der p 9 is mixed chymotryptic/elastase-like, due to the presence of Ala189 in the S1 pocket [244, 245]. Structural differences to the mammalian counterparts are small, such as a Thr15 or Gly15 preceding the propeptide, only three disulfides and a shortened 75-loop. It has been demonstrated that Der p 3 and 9 can activate PAR-2 and that serpins inhibit them [246]. Other mites from tropical areas exhibit related allergenic proteases, such as Blo t 3, Tyr p 3 and Sar s 3 [245].

Also, the American cockroach (Periplaneta americana) produces a trypsin-like serine protease allergen, Per a 10, which causes allergic bronchial inflammation via cleavage of several cellular receptor proteins n [247]. Recently, three Per a 10 related enzymes from the German cockroach (Blatella germanica), were identified, which activate MAP kinase and enhance the allergic response via cleavage of PAR-2 [248].

2.8. Serine proteases from fungi, bacteria and viruses

Alpha-lytic protease from Lysobacter enzymogenes, with elastase-like specificity, has gained some interest as model protease for structure-functional studies, e.g. crystallography in the subångström range [249, 250]. Streptogrisin B is a fungal P1-Lys specific serine protease from Streptomyces griseus, which serves as model protease for structure-based mechanistic studies, despite considerable deletions, resulting in a 186 residue molecule (Fig. 6C) [251]. By contrast, streptogrisin E (glutamyl endopeptidase II) and other serine proteases produced by bacteria from the genus Staphylococcus and Bacillus, such as glutamyl endopeptidase I, display an unusual specificity for P1-Glu [252]. The related glutamyl epidermolysin A and B or so-called exfoliative toxins from Staphylococcus aureus and similar species destroy components of the human epidermis, resulting in blisters and progression to deeper layers of the skin [253]. They cleave cadherins, such as desmoglein-1 after P1-Glu residues with high specificity. IgA1-specific serine proteases are present in Neisseria bacteria and the virus Haemophilus influenza, and are related to the HAP protease, an unusual autotransporter of S6 family with a chymotrypsin-like protease domain [254].

3. The loop system of family S1 serine proteases and its modulators

3.1. The N-terminal activation loop