Significance

The emergence of a tracheal system for respiration is one of the landmarks of terrestrial adaptations among arthropods. Yet, this system is diverse in its organization and elusive in its origin. By studying tracheal development in Oncopeltus fasciatus, we demonstrate the role of Hox genes in its morphogenesis and distinct segmental patterning. Furthermore, we report that the exocrine glands express ventral veinless and are under the regulation of Hox genes, similar to the endocrine glands and the trachea. This discovery highlights how a shared gene network could have regulated the development of these structures in a common insect–crustacean ancestor.

Keywords: trachealess, ventral veinless, cut, Oncopeltus, tracheal system

Abstract

The diversity in the organization of the tracheal system is one of the drivers of insect evolutionary success; however, the genetic mechanisms responsible are yet to be elucidated. Here, we highlight the advantages of utilizing hemimetabolous insects, such as the milkweed bug Oncopeltus fasciatus, in which the final adult tracheal patterning can be directly inferred by examining its blueprint in embryos. By reporting the expression patterns, functions, and Hox gene regulation of trachealess (trh), ventral veinless (vvl), and cut (ct), key genes involved in tracheal development, this study provides important insights. First, Hox genes function as activators, modifiers, and suppressors of trh expression, which in turn results in a difference between the thoracic and abdominal tracheal organization. Second, spiracle morphogenesis requires the input of both trh and ct, where ct is positively regulated by trh. As Hox genes regulate trh, we can now mechanistically explain the previous observations of their effects on spiracle formation. Third, the default state of vvl expression in the thorax, in the absence of Hox gene expression, features three lateral cell clusters connected to ducts. Fourth, the exocrine scent glands express vvl and are regulated by Hox genes. These results extend previous findings [Sánchez-Higueras et al., 2014], suggesting that the exocrine glands, similar to the endocrine, develop from the same primordia that give rise to the trachea. The presence of such versatile primordia in the miracrustacean ancestor could account for the similar gene networks found in the glandular and respiratory organs of both insects and crustaceans.

Upon transition to terrestrial environments, many arthropods, including insects, developed a tracheal system for respiration. This system is composed of a network of tubes (trachea) that are connected to the outside through epidermal openings known as spiracles. In Drosophila melanogaster, 10 tracheal placodes develop, invaginate, and branch to form the tracheal network [for a review, see Manning and Krasnow (1)]. This process is regulated by the upstream regulatory transcription factors trachealess (trh) and ventral veinless (vvl), which in turn activate numerous tracheal genes (2–4) [for a review, see Hayashi and Kondo (5)]. Moreover, the Hox gene Abdominal-B (Abd-B) specifies the formation of the posterior spiracles through the activation of downstream targets, including the homeodomain transcription factor cut (ct) (6, 7). Recently, it was shown that the development of the tracheal system is related to the development of the endocrine glands since both originate from serially homologous primordia that are regulated by Hox genes (8).

Although the genetic control of tracheal morphogenesis is extensively studied in Drosophila, we know very little about its regulation in more basal insect lineages. This study provides a comprehensive analysis of tracheal system development using a hemimetabolous species, the milkweed bug (Oncopeltus fasciatus). In this mode of development, the hatched embryos resemble adults in morphology except for size and absence of wings and genitalia. Hence, the tracheal organization established during embryogenesis can serve as a blueprint for studying the final adult morphology (Fig. 1). This direct relationship between embryonic and adult tracheal patterning circumvents the complexities that exist in Drosophila, where the tracheal system is repatterned before reaching the adult stage by utilizing the combined input of imaginal and larval cells (9–12).

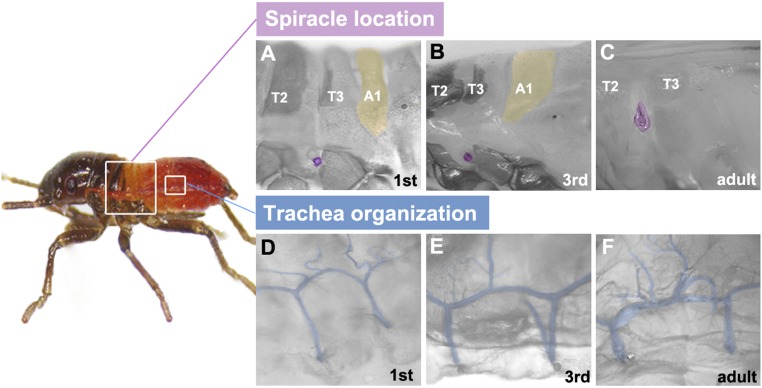

Fig. 1.

Spiracle location and trachea organization in Oncopeltus. (A–C) Location and number of spiracles are conserved from first nymph to adult. The spiracle of the second thoracic segment (T2) is pseudocolored in magenta, while the A1 segment is pseudocolored in yellow. (D–F) Tracheal organization (pseudocolored in blue) is also conserved throughout postembryonic development. Anterior is Left in all panels.

In this study, we analyze the expression pattern and function of trh, vvl, and ct, and the role Hox genes play in their regulation. First, we document a difference in the tracheal branching pattern in the thorax and abdomen, which is controlled by Hox genes functioning as activators, modifiers, or suppressors of trh expression. Second, in the absence of Hox genes, vvl’s default expression pattern in the thorax features three distinct cell clusters that are connected to ducts. Third, the salivary and scent glands, both of which have exocrine function, express vvl and are regulated by Hox genes. Together, these observations complement previous findings (8) and suggest that the exocrine glands might develop from the same homologous precursors that give rise to the endocrine glands and the tracheal system.

Results and Discussion

Development of the Oncopeltus Tracheal System.

To analyze tracheal system development in Oncopeltus, we first examined the expression pattern of trh during embryonic development. Initial trh expression appears at around 25% of embryonic development (Fig. 2A) and is localized in three tracheal placodes (Tr1–Tr3). Staining with engrailed (en), which marks the segmental posterior boundary (13, 14), shows that these placodes are located in the anteriormost regions of segments T2, T3, and A1, respectively (Fig. 2A′). By 35% of embryonic development, an additional seven tracheal placodes have formed spanning from segments A2 to A8 (Fig. 2B). This temporal difference, regarding the development of tracheal placodes, contrasts with the simultaneous placode development in Drosophila and Tribolium (1, 2, 15). At this stage, trh expression also appears in the salivary glands (SGs) and begins to extend from Tr1 into the posterior region of the T1 segment (Fig. 2 B and B′, arrowhead). Subsequently, Tr1 expansion into the posterior region of T1 increases (Fig. 2 C, Inset), and Tr2 and Tr3 begin their expansion into the posterior compartments of T2 and T3, respectively (Fig. 2C′, arrowheads). At the same time, the abdominal tracheal placodes remain in their respective segments while beginning to extend laterally (Fig. 2C″). Interestingly, in the Drosophila embryo, all tracheal placodes extend anteriorly into the adjacent segments (1). Overall, this duality in Oncopeltus tracheal branching (different patterns in thorax and abdomen) is correlated with the temporal differences in tracheal formation (thorax first, abdomen second) and may be representative of hemimetabolous insect lineages in general.

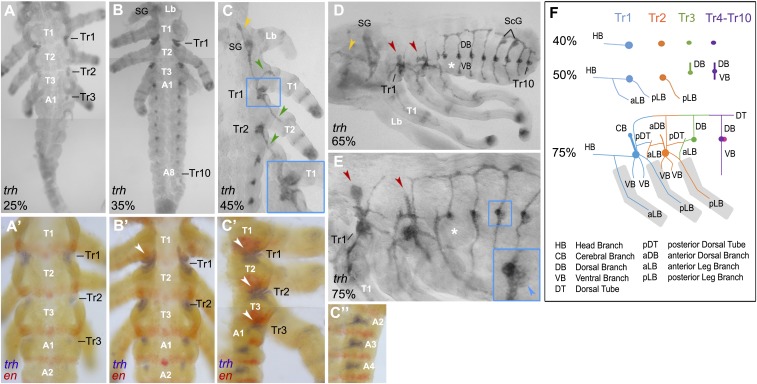

Fig. 2.

trh mRNA expression during Oncopeltus embryogenesis. (A and B) The formation of tracheal placodes (Tr) begins in T2–A1 segments, followed by the formation of abdominal placodes in A2–A8. (C) Head branch (orange arrowhead) and leg branches (green arrowheads) migrate from Tr1 and Tr2 placodes. (C, Inset) Tr1 placode extends further into the posterior T1 segment. (A′–B′) Double labeling of trh and en used to precisely determine the location of placode formation. Arrowhead in B′ points to expansion of Tr1 into en domain. (C′ and C″) While thoracic placodes extend anteriorly (arrowheads), abdominal placodes extend only laterally. (D) DBs, VBs, and DTs form in the abdomen, except for Tr3 which lacks a VB (asterisk). Also, the signal appears in the ScGs. The head branch continues to extend anteriorly (orange arrowhead). Thoracic placodes form large branches extending dorsoanteriorly (red arrowheads). (E) Thoracic branches continue to extend (red arrowheads). (E, Inset) A fainter trh signal appears posterior to the abdominal primary placodes (blue arrowhead). (F) Diagram summarizing the progression of tracheal branching at 40, 50, and 75% embryonic development. Anterior is Top in A–C″. Anterior is Left in D–F. Combined images are used for A, B, and C′.

First branch morphogenesis arises from Tr1 and extends into the SGs and the head region, forming the head branch (HB) (Fig. 2C, orange arrowhead). Two additional branches extend from anterior and posterior Tr1 into the first and second thoracic legs (T1, T2), respectively, while a single branch extends posteriorly from Tr2 into T3 leg (Fig. 2C, green arrowheads). These tubular extensions form the anterior and posterior leg branches (aLB, pLB; Fig. 2F). Postkatatrepsis, abdominal branches have completely formed, encompassing both the dorsal branches (DBs) that connect to a lateral dorsal tube (DT), and the ventral branches (VBs) that connect to the ventral branches on the opposite side (Fig. 2D). Note that Tr3, while located in the abdomen, lacks a ventral branch (Fig. 2D, asterisk), which is consistent with the fact that the A1 segment is anatomically composed only of a dorsal half in Oncopeltus (Fig. 1 A and B). At this stage, trh expression also appears in the duct cells of the scent glands (ScGs) located in segments A5 and A6 (Fig. 2D).

While abdominal branch formation is complete by 65% of embryonic development, new branches continue to form from Tr1 and Tr2 placodes extending in the anteriodorsal direction (Fig. 2D, red arrowheads). These new thoracic branches continue to migrate, showing extensions that may contribute to wing development (16) (Fig. 2E, red arrowheads). At this time, a faint trh expression is detectable posterior to each primary abdominal placode (Fig. 2 E, Inset, blue arrowhead). Finally, the Tr1 branch reaches the prothoracic glands (PGs), marked by the expression of the marker gene phantom (phm), suggesting homology to the Drosophila cerebral branch (17, 18) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). A summary diagram depicting the progression of tracheal branching at 40, 50, and 75% embryonic development is presented in Fig. 2F.

The Role of Hox Genes in the Segmental Organization of the Oncopeltus Tracheal System.

Sánchez-Higueras et al. (8) have shown that the posterior Hox genes (Antennapedia [Antp], Ultrabithorax [Ubx], and abdominal-A [abd-A]) can induce trh expression in the developing Drosophila embryo, raising the possibility that these genes may also be responsible for the observed differences in timing and patterning of trh expression between the thoracic and abdominal segments in Oncopeltus (Fig. 2). To test for this, we began by examining the role of Antp, which is strongly expressed in the thorax of Oncopeltus (19) and has also been found to be expressed in the embryonic thoracic tracheal placodes of Drosophila and the moth Manduca sexta (8, 20). In our experiments, Oncopeltus Antp RNAi embryos are characterized by the complete loss of trh expression in Tr1 and Tr2 (Fig. 3A, asterisks and A′) and a gain of ectopic dorsal and ventral branches in Tr3 (Fig. 3A, arrowheads). These results indicate that Antp has a primary role in activating tracheal placode formation in the thorax (Tr1–2), while also regulating tracheal branching pattern in T3 segment (which arises from A1; Fig. 2A′). While Antp can activate trh in Drosophila, Antp mutants do not lose trh expression, indicating a redundant control of trh expression by Antp and additional factors (8). Present results in Oncopeltus reveal that a Hox gene alone can regulate tracheal development, suggesting that the redundancy in trh activation is not universal but rather one of the differences between these hemi- and holometabolous insects.

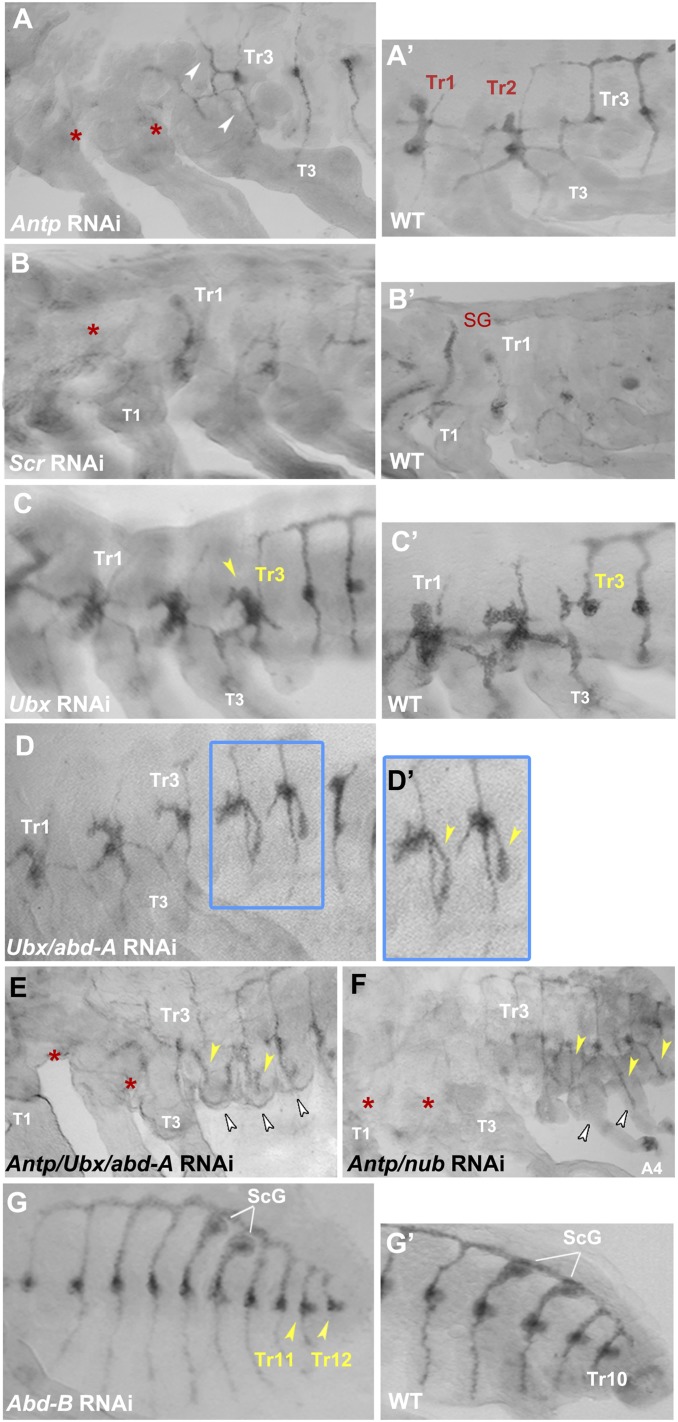

Fig. 3.

Hox gene regulation of trh expression. (A and A′) Compared to WT, trh expression is absent in Tr1 and Tr2 placodes (red asterisks) and ectopic branches arise from Tr3 (arrowheads) in Antp RNAi. (B and B′) Compared to WT, Scr RNAi embryos show loss of signal in SGs (red asterisk). (C and C′) Compared to WT, trh expression in the Tr3 placode becomes thoracic-like (yellow arrowhead). (D and D′) Ubx/abd-A RNAi embryos show an increase of the size of Tr3–Tr5 as well as the appearance of ectopic leg branches (yellow arrowheads). (E and F) Antp/Ubx/abd-A RNAi and Antp/nub RNAi embryos show consistent loss of signal in the thorax (red asterisks) and its continued presence in the abdomen. The trend toward the formation of ectopic abdominal leg branches (yellow arrowheads) is more prominent in Antp/nub RNAi embryos. In both panels, white arrowheads point to ectopic abdominal legs. (G and G′) Compared to WT, Abd-B RNAi results in the formation of two ectopic tracheal placodes (Tr11 and Tr12). All panels show embryos between 65 and 75% embryonic development. Anterior is Left in all panels.

Next, we asked whether other Hox genes also control trh activation or tracheal branching morphology. Among the three thoracic segments, the lack of placode formation in the anterior region distinguishes the T1 segment from T2–3 segments (Fig. 2A′). As Sex combs reduced (Scr) was shown previously to regulate Oncopeltus sex comb development in T1 legs, and it is weakly expressed in anterior of T1 segment (19) (SI Appendix, Fig. S2), we examined whether it has a role in suppressing trh expression in the anterior prothorax. Scr RNAi embryos exhibit wild-type (WT)–like tracheal pattern in the prothorax and the only observed effect is the loss of trh expression in the salivary glands (Fig. 3B, asterisk and B′). This result is consistent with the role of Scr in regulating SG development in Drosophila (2) and corroborates the previous finding that Scr acts to regulate a distinct prothoracic identity mainly during postembryonic development (21).

Following our findings regarding Antp’s role in activating trh in the thorax, we asked whether posterior Hox genes (Ubx, abd-A, and Abd-B) may have a similar role in the abdomen. In these experiments, we find that the knockdown of Ubx, which is expressed in T3 and anterior A1 segments (19, 22) (SI Appendix, Fig. S2), leads to the transformation of trh expression pattern in the Tr3 placode to that of Tr2 (Fig. 3C, yellow arrowhead and C′). The knockdown of both Ubx and abd-A, which is expressed in A1–A8 (19) (SI Appendix, Fig. S2), similarly results in the transformation of the abdominal tracheal pattern into that of the thoracic trachea. This is evident by an increase in placode size and formation of leg branches (Fig. 3 D and D′, yellow arrowheads). However, this transformation is mainly observed in the anterior abdomen, suggesting that the depletion of abd-A may not be uniformly distributed across the abdomen. To address this, we targeted the gene nubbin (nub) by RNAi, which we have previously shown is required for the activation of abd-A specifically in the abdominal segments A3–A8 (23). nub RNAi leads to the complete loss of abd-A expression in this region, causing a strong conversion of abdominal to thoracic segment identities (23). Consistent with this, we find that nub RNAi embryos exhibit trh expression in Tr5–Tr7 placodes with a clear thoracic-like pattern (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A). These results complement the observed phenotypes in Ubx/abd-A double knockdowns, suggesting that these genes may function in modifying (rather than activating) trh expression in the abdomen.

However, an additional complexity needs to be accounted for in the interpretation of the above results. While Ubx and abd-A may indeed activate trh in the abdomen, it may be the posterior expansion of Antp upon their knockdown (24, 25, but see ref. 17), which is responsible for the observed phenotype. To address this caveat, we performed triple Antp/Ubx/abd-A knockdown experiments. The resulting embryos persist in expressing trh in the abdomen that displays signs of thoracic identity in the form of ectopic leg branches (Fig. 3E, yellow arrowheads). Note that the trh signal in the thorax, however, is greatly reduced (Fig. 3E, asterisks), an indication that Antp is sufficiently knocked down. Notwithstanding, this evidence of efficient Antp depletion, individual gene knockdown can show stochasticity in efficiency in multigene RNAi experiments (26), to the effects that not all target transcripts are equally reduced. To address the possibility of low efficiency of the abd-A knockdown, we also performed a double knockdown of Antp and nub. In these embryos, trh is completely absent from the thorax (Fig. 3F, asterisks), but present in the abdomen. Although residual gene expression in a multigene RNAi cannot be ruled out, the observed persistence of trh expression in the abdomen further corroborates the putative roles of Ubx and abd-A as modifiers of tracheal abdominal pattern.

Finally, we examined the role of Abd-B in tracheal development. In wild-type Oncopeltus embryos, the last tracheal placode (Tr10) is in segment A8; in Abd-B RNAi embryos, by contrast, two ectopic tracheal placodes (Tr11 and Tr12) form in segments A9 and A10 (Fig. 3G, yellow arrowheads and G′). Hence, unlike other Hox genes examined so far, Abd-B appears to have a suppressive role in trachea formation in Oncopeltus. This is in contrast to observations in Drosophila where Abd-B is an activator of trh in the posterior spiracles (7).

Overall, the results obtained in Oncopeltus provide several insights regarding the evolution of trh expression and its regulation in insects. First, Antp alone is essential for the activation of tracheal development in the thorax in contrast to its redundant role in the regulation of Drosophila trachea (8). Second, Ubx and abd-A appear to function in modifying trh expression and specifying its pattern during the embryonic development of the abdomen in Oncopeltus. It would, therefore, be interesting to investigate whether Oncopeltus Ubx and abd-A gene activities are capable of modifying the uniform tracheal pattern in Drosophila thus distinguishing the abdominal trachea from that of the thorax. Third, Abd-B acts as a repressor of trh expression in the posterior abdomen of the Oncopeltus embryo. This suppression may be due to Abd-B regulation of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway (27, 28), as the JAK/STAT signaling has been reported to activate trh expression in Drosophila in addition to the Hox gene input (29, 30). In Oncopeltus, we speculate that the JAK/STAT signaling pathway has a similar role in tracheal development, particularly in regards to activation of trh in the abdomen. Additionally, our present results suggest that JAK/STAT signaling is not acting redundantly with Antp and Abd-B Hox genes, but rather may be a downstream factor of them. This would be consistent with the complete loss or gain of trh expression we observe due to their knockdowns.

The Morphogenesis of Thoracic and Abdominal Spiracles in Oncopeltus.

Oncopeltus develops two thoracic and seven abdominal spiracles during embryogenesis. The location of spiracles is maintained in subsequent nymphal stages and finally in the adults (Fig. 1 A–C). To examine spiracle development during Oncopeltus embryogenesis, we analyzed the expression and function of the homeobox transcription factor, ct. In Drosophila, ct is expressed in the spiracular chamber of the posterior spiracles before and after their invagination occurs (7). Additionally, in Tribolium, ct is expressed in the primordia of the lateral spiracles where it is also required for their formation (15). In Oncopeltus, we observe ct expression in 10 clusters spanning from the posterior region of T1/anterior region of T2 to the A8 segment (Fig. 4 A and B), and RNAi depletion of ct transcripts results in loss of all spiracles in hatched first nymphs (Fig. 4C′, asterisks). The location of ct expression corresponds to the location of spiracles in nymphs, except for the A1 segment (Fig. 4 A and B, arrows) that does not form a spiracle (Fig. 4C). Although the two thoracic spiracles are located in the posterior regions of T1 and T2 in the first nymphs (Fig. 4C, arrowheads), ct expression in the spiracle primordia (Sp) is initiated in the boundary between T1/T2 (Sp1) and anterior T3 (Sp2), respectively (Fig. 4 A and A′). This is subsequently followed by the expansion of Sp1 into the posterior region of T1 around 50% embryogenesis (Fig. 4A′, arrowheads). Due to the very weak expression of en during late embryonic development, we cannot determine the precise stage when Sp2 becomes positioned in the posterior region of T2. The development of the abdominal spiracles’ primordia, however, occurs in the anterior compartment of each segment (Fig. 4A′) and remain at the same location in first nymphs (Fig. 4C, arrows). Interestingly, the varied segmental location between the thoracic spiracles (posterior compartment) and the abdominal spiracles (anterior compartment) in Oncopeltus is similar to the differential location observed between the anterior spiracles (located in the posterior of T1) and the posterior spiracles (located in the anterior of A8) of Drosophila (1, 31). Finally, the absence of a spiracle in T3 (Fig. 4C) may be a common feature to insects, as it was also reported in Tribolium, Drosophila larvae, and Manduca (15, 20, 32).

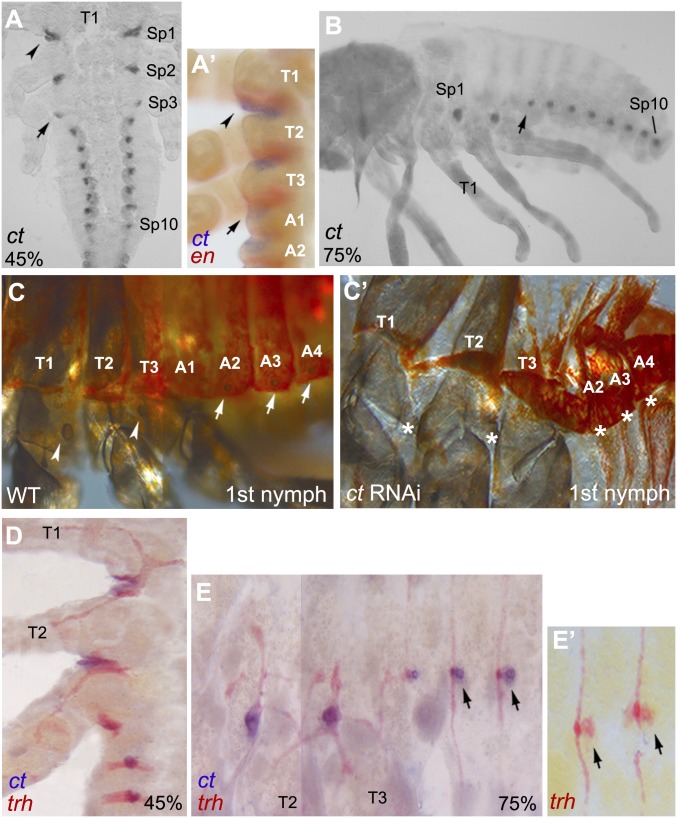

Fig. 4.

Expression and function of ct in Oncopeltus. (A and B) ct is expressed in the Sp from posterior T1/anterior T2 (arrowhead) to A8 and continues to late embryogenesis. (A′) Double labeling of ct and en shows that signal in Sp1 extends into the en domain of the T1 segment (arrowhead). The arrows in A and B points to ct expression in the A1 segment where a spiracle does not form. (C) In WT first nymphs, there are two thoracic spiracles located in posterior T1 and posterior T2 (arrowheads), and seven abdominal spiracles (only three shown) located anteriorly (arrows). Note that T3 and A1 lack a spiracle. (C′) All spiracles are lost in ct RNAi nymphs (asterisks). Differences in melanization levels between C and C′ are due to the lethality of ct knockdown and death of nymphs prior to full melanization. (D) ct is colocalized with trh in thoracic and abdominal placodes. (E and E′) Finer characterization of ct in the abdomen, showing that the signal is colocalized with trh weak expression posterior to the primary placodes (arrows). Anterior is Top in A and A′ and D. Anterior is Left in B, C, C′, E, and E′. Combined images are used for C and E.

Location of ct expression in the spiracle primordia coincides with the location of trh expression in the placodes (compare Fig. 2 B and D with Fig. 4 A and B). To determine if these two genes are coexpressed, we performed double in situ hybridization. As predicted, ct expression indeed overlaps with the location of the tracheal placodes (Fig. 4D). A more detailed analysis of the late stage of embryogenesis reveals that ct expression in the abdomen is specifically colocalized with the weaker expression of trh, located immediately posterior to the primary placodes that give rise to the tracheal network (Fig. 4 E and E′, arrows; Fig. 2E, blue arrowhead). This result suggests that spiracles and trachea may develop from separate populations of precursor cells. In other words, spiracle primordia are located next to the abdominal tracheal placodes and are characterized by the expression of both trh and ct, which resembles the coexpression of trh and ct in the spiracle primordia in Drosophila and Tribolium (7, 15).

The Role of Hox Genes and trh on Spiracle Formation.

Until now, only the larval posterior spiracles in Drosophila have been used as a model to study the genetic mechanisms governing spiracle organogenesis in insects [for a review, see Castelli Gair Hombría et al. (33)]. These respiratory structures develop in segment A8 and are controlled by Abd-B (6), which activates numerous downstream targets, including the transcription factor ct (7). Whereas the posterior spiracles are formed during embryogenesis, the formation of the anterior spiracles, located in posterior T1/anterior T2, occurs during the second larval instar. Consequently, eight additional spiracles develop during the late larval stage and become functional in the adult (1). Note that these adult spiracles develop from the contribution of both imaginal cells (that originate during embryogenesis) and larval cells (that reenter the cell cycle) (10–12).

As Oncopeltus develops all spiracles during embryogenesis in segments T1–A8 where Abd-B is not expressed (19), we asked what the upstream factors are controlling ct expression and spiracle organogenesis in this case. Antp and Ubx have been previously reported to play a regulatory role in spiracle development and spiracle repression, respectively (20, 32, 34–36). In Antp RNAi embryos, ct expression is completely lost in the thorax (Fig. 5B, asterisks), indicating that Antp is regulating spiracle development in this region. Knockdown of Ubx results in the ectopic expression of ct in the posterior T3/anterior A1 (Fig. 5C, arrow), resulting in the formation of ectopic spiracle in posterior T3 in the first nymphs (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B). This is consistent with the observations in Drosophila and Tribolium Ubx mutants (32, 36). In addition, there is a loss of ct expression in the A1 segment in embryos (Fig. 5C, asterisk). Overall, these results are in accordance with the previously described segmental transformation of T3 to T2 and A1 to T3 in Oncopeltus (19). In contrast, abd-A RNAi does not affect ct expression (Fig. 5D). The knockdown of Abd-B, finally, causes ectopic expression of ct in the A9 and A10 segments (Fig. 5E, arrows) and the consequential formation of ectopic spiracles in those segments was reported by Angelini et al. (19).

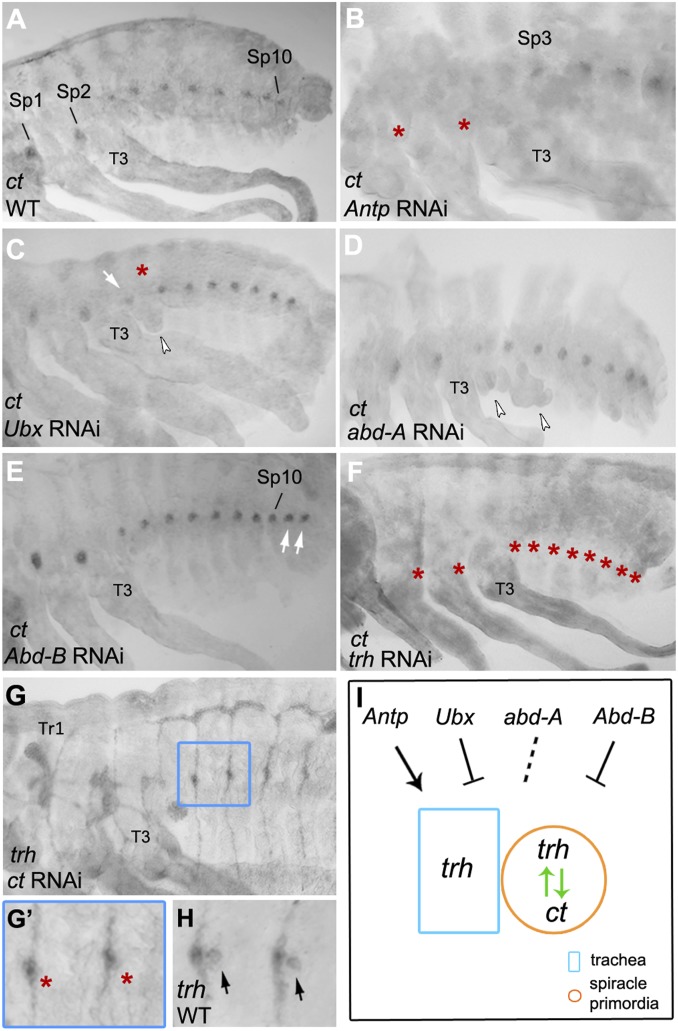

Fig. 5.

Regulation of ct expression by Hox genes and trh. (A) Expression of ct in WT embryos. (B) Antp RNAi embryos display loss of ct signal in the thorax (asterisks). (C) Ubx RNAi embryos showing ectopic expression of ct in posterior T3 (arrow) and loss of ct expression in A1 (asterisk). Arrowhead points to ectopic leg formation in A1. (D) ct expression is unaltered in abd-A RNAi; arrowheads point to ectopic legs in the abdomen. (E) Abd-B RNAi embryos showing ectopic expression of ct in the last two abdominal segments (arrows). (F) All ct expression is lost in trh RNAi (asterisks). (G) trh expression in the tracheal placodes and branches is unaltered in ct RNAi. (G′) Magnified detail from G showing absence of trh in the spiracle primordia (asterisks). (H) trh expression in spiracle primordia in WT (arrows). (I) Diagram of ct regulation by trh and Hox genes. Hox genes regulate trh in the trachea (blue rectangle) and in the spiracle primordia (orange circle); trh and ct cross-regulate each other in the spiracle primordia only (green arrows). The dotted line indicates a lack of effect of abd-A on trh and ct. All panels show embryos between 65 and 75% embryonic development. Anterior is Left in all panels.

The above experiments show that the posterior Hox genes Antp, Ubx, and Abd-B control spiracle formation in Oncopeltus through the regulation of ct expression, acting as either activators or suppressors (Fig. 5). However, abd-A has no effect on the abdominal spiracles (Fig. 5D), suggesting that another factor is regulating ct expression in the A2–A8 segments. Given that trh is expressed in the spiracle primordia and colocalized with ct expression (Fig. 4 D and E), we tested whether ct is regulated by trh. In trh RNAi embryos, there is a complete loss of ct expression in both the thorax and the abdomen (Fig. 5F, asterisks). In the complementary experiment, i.e., the knockdown of ct, trh expression in the placodes and the tracheal branching is unaltered, but the expression of trh in the spiracle primordia is lost (Fig. 5 G and G′, asterisks). Together, these results indicate the presence of a cross-regulatory interaction between trh and ct in the spiracle primordia, where the two regulators depend on each other for spiracle formation.

A genetic interaction between trh and ct was also found in the Drosophila posterior spiracles, where trh is activated by ct in the spiracular chamber and is essential for the normal development of the filzkorper (7). These two genes are also coexpressed in the lateral spiracles in Tribolium, but their regulation has not been tested yet (15). Our analysis in Oncopeltus further shows that, in addition to the regulation of trh by ct (as in Drosophila), trh can also positively regulate ct (Fig. 5I). This, in turn, provides a more comprehensive understanding of the observed effects of Hox genes on spiracle formation. In the case of Antp, its knockdown causes a complete loss of trh signal in the thorax (both in the tracheal placodes and the spiracle primordia), which in turn leads to loss of ct expression (Figs. 3A and 5B). In the case of Abd-B, its knockdown leads to the ectopic expression of trh, which in turn leads to the activation of ct in A9 and A10 segments (Figs. 3G and 5E). Similarly, knockdown of Ubx in T3 causes the formation of an ectopic Tr2-like placode in this segment, which in turn leads to ct activation and the formation of an ectopic spiracle (Figs. 3C and 5C and SI Appendix, Fig. S4B). Finally, abd-A knockdown does not affect trh activation, and as a result, ct expression remains unaltered (Figs. 3D and 5D). In summary, Hox genes regulate trh expression both in the trachea and in the spiracle primordia (Fig. 5I). Their role in the latter explains how Hox genes regulate the formation of spiracles, which is accomplished via trh regulation of ct.

Expression of vvl in Oncopeltus Trachea and Glands.

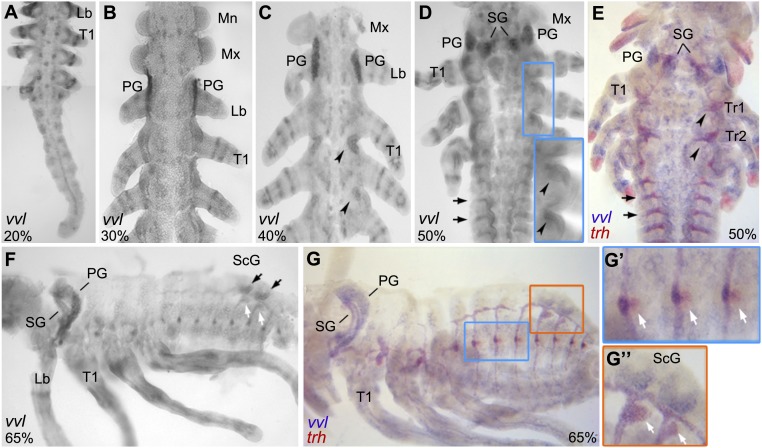

To provide a more comprehensive analysis of Oncopeltus tracheal system development, we also examined the expression and function of the POU-domain transcription factor, vvl (3, 4). In Drosophila, vvl is activated by the JAK/STAT signaling pathway, and along with trh, regulates a multitude of downstream tracheal genes (29, 30, 37, 38). In addition, vvl is involved in gland formation (corpora allata [CA] and prothoracic glands) under the regulation of the head Hox genes (8). In Oncopeltus, the earliest vvl expression is restricted to the appendages and the central nervous system (CNS), and continues through late embryogenesis (Fig. 6). By 40% of embryonic development, strong vvl signal appears in lateral clusters of cells located at the boundary between T1 and T2, and T2 and T3 (Fig. 6C, arrowheads), corresponding to Tr1 and Tr2 placodes, respectively (Fig. 2A). Subsequently, vvl signal in the thorax expands (Fig. 6 D, Inset, arrowheads), and lateral stripes appear in the abdomen (Fig. 6D, arrows). To better characterize vvl expression in the trachea and the spiracles, we performed double in situ hybridization with vvl and trh probes. As illustrated by arrows and arrowheads in Fig. 6E, vvl is indeed coexpressed with trh in the tracheal placodes and branches, in both the thorax and the abdomen. Note that, while vvl expression continues in the trachea during late development (Fig. 6 F and G), vvl is not coexpressed with trh at the location of the spiracle primordia (Fig. 6G′, arrows). This result is consistent with the lack of vvl expression in the Drosophila posterior spiracles (30), suggesting that spiracle morphogenesis in both hemimetabolous and holometabolous insects does not require vvl.

Fig. 6.

vvl mRNA expression during Oncopeltus embryogenesis. (A and B) vvl expression starts in the appendages and CNS, followed by appearance in PGs. (C) New expression appears in the lateral thorax (arrowheads), while the signal in PGs expands. (D) There is an additional expression in SGs, and further modulation of vvl signal in the thorax (Inset, arrowheads) and abdomen (arrows). (E) vvl is colocalized with trh in the SG, Tr1–Tr2 (arrowheads), and abdomen lateral branches (arrows). (F) At this stage, PG moves into T1, and vvl becomes visible in the excretory cells (black arrows) and duct cells (white arrows) of ScG. (G–G″) While vvl is colocalized with trh in the SG, trachea, and duct cells of the ScG (see G″, arrows), it is solely expressed in the abdominal placodes and not in the spiracle primordia (see G′, arrows). Mandibles, Mn; maxillary, Mx; labial, Lb; pr sali. Anterior is Top in A–E. Anterior is Left in F–G″. Combined images are used for A.

In addition to its expression in the tracheal system, vvl is also observed in Oncopeltus glands. At first, vvl is restricted to the PGs in the labial segment (Fig. 6 B and C). By 50% embryogenesis, vvl appears in the salivary glands as well (Fig. 6D). The expression of vvl in both of these head glands remains through late embryogenesis, when the prothoracic glands begin to extend into the T1 segment (the prothorax; Fig. 6F). Note that there is no vvl expression in the maxillary segment at any stage of development. Given that the CA develops in this segment (39), this observation suggests that vvl is not involved in CA development unlike in Drosophila (8). Finally, by 65% of embryogenesis, vvl is observed in the dorsal abdomen at the location of the scent glands (Fig. 6F). Specifically, vvl is expressed in both the secretory cells (Fig. 6F, black arrows) and the duct cells (Fig. 6F, white arrows), where in the latter, it is colocalized with trh (Fig. 6G″, white arrows). Overall, these results allow us to compare the presence or absence of vvl expression in Oncopeltus and Drosophila glands. First, in the case of the endocrine glands, vvl is only expressed in the PGs in Oncopeltus, whereas it is found in both PGs and CA in Drosophila (8). Second, vvl is expressed in the SGs and ScGs, both of which are exocrine glands in Oncopeltus. This is different from Drosophila, which lacks the ScGs, and where vvl is not expressed in the SGs (3, 4). In broader terms, vvl in Oncopeltus is present in both the endo- and the exocrine glands, while in Drosophila, it is restricted to the endocrine glands only.

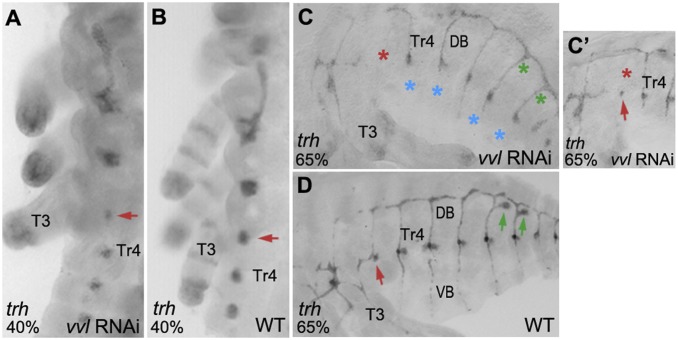

Genetic Regulation between trh and vvl.

The initiation of trh and vvl expression is independent of each other in Drosophila (29, 30, 37); however, the subsequent expression of each gene is maintained by autoregulation involving protein–protein interaction between the PAS domain of Trh and the POU domain of Vvl (40–43). We tested whether a similar regulation is present in Oncopeltus. While vvl RNAi causes embryonic lethality, embryos can complete 80 to 90% of embryogenesis, thus allowing us to assess the effects of vvl knockdown on trh expression. As shown in Fig. 7A, there are no changes in trh early expression (compared to WT in Fig. 7B), indicating that trh activation is independent of vvl. This is similar to findings in Drosophila (38, 40, 42), suggesting commonality in trh activation. At later stages, when the tracheal tubes have formed, we also observe trh expression (Fig. 7C), indicating that, broadly, the maintenance of trh expression does not require vvl. However, there are three significant effects of vvl RNAi on trh in Oncopeltus. First, there is a loss of trh signal in the Tr3 placode (Fig. 7C, red asterisk). In milder phenotypes, there is a minimal expression of trh in Tr3 (Fig. 7C′, red arrow), in addition to lack of dorsal branch formation (Fig. 7C′, red asterisk). This is consistent with the reduced trh expression in Tr3 at earlier stages (Fig. 7A, red arrow). This specific effect on the Tr3 placode is puzzling; however, it could be related to the unique morphology of A1 in Oncopeltus, which is composed of a dorsal half only (Fig. 1 A and B). Second, there is no trh expression in the ventral branches of the abdomen (Fig. 7C, blue asterisks). Since trh can autoregulate its expression in the dorsal branches, the most likely explanation for its absence from the ventral branches is that the ventral trachea itself fails to form. In other words, the absence of trh signal is due to the absence of the ventral trachea. Additionally, this implies that vvl may be required for the formation of the ventral trachea, but not the dorsal. In this scenario, dorsal and ventral branch formation in Oncopeltus may be regulated separately. Further studies in additional species could determine if this is a common feature in hemimetabolous insects. Third, trh is lost in the duct cells of the scent glands (Fig. 7C, green asterisks). This could be because trh expression is dependent on the presence of vvl in these cells (Fig. 6G″, arrows). Alternatively, loss of trh may be a consequence of the loss of the scent glands. However, at this time, we cannot distinguish between the two possibilities due to the lethality of vvl RNAi, which in turn prevents full determination of its role in scent gland organogenesis.

Fig. 7.

trh expression in vvl RNAi embryos. (A and B) Compared to WT, trh expression is unaltered, except for reduced expression in the Tr3 placode (red arrow). (C and D) At a later stage, trh is lost in Tr3 (red asterisk), the VBs (blue asterisks), and in the duct cells of ScGs (green asterisks). (C′) A vvl RNAi embryo with a mild phenotype showing presence of Tr3 placode (red arrow), but the lack of dorsal branch formation (red asterisk). Anterior is Top in A and B. Anterior is Left in C′ and D.

We also performed the complementary experiment to determine the effect of trh knockdown on vvl expression. At the early stage, vvl expression is not affected (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 A and A′), establishing that early vvl expression is not dependent on trh. During late development, vvl is lost in the trachea but maintained in the CNS and the glands (SI Appendix, Fig. S5B). Loss of vvl from the trachea during late development, is most likely due to the requirement of trh for its maintenance, consistent with previous findings in Drosophila (40, 42). In summary, the initial expression of trh and vvl is independent of each other in Oncopeltus. However, we find that vvl requires trh during late development, whereas trh continued expression is independent of vvl. Although this latter result contradicts findings by Zelzer and Shilo (42) and Boube et al. (40), it is consistent with a later study by Chung et al. (38), showing that trh mRNA and protein levels do not alter in Drosophila vvl mutants. Taken together, it appears that vvl’s role on trh autoregulation may be minimal in both insect species.

Hox Genes and Gland Development.

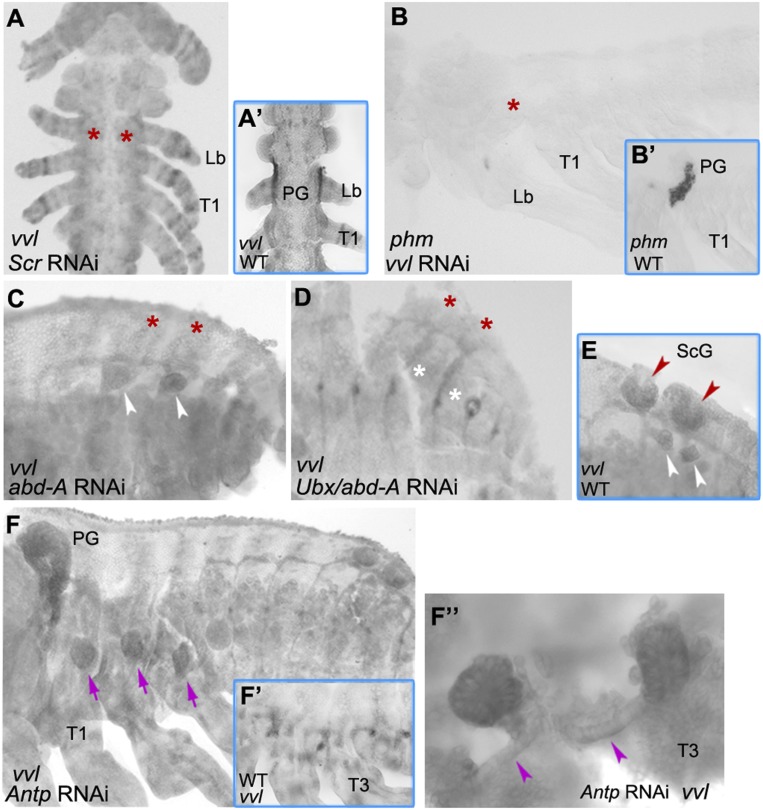

One of the most significant new insights into tracheal system development is the discovery that endocrine glands and trachea arise from serially repeated precursors and can convert to each other (8). These primordia express vvl and are specified to become glands or trachea through the action of Hox genes and JAK/STAT signaling. The head Hox genes (Scr and Deformed [Dfd]) activate vvl to form the PG and CA, whereas the trunk Hox genes (Antp, Ubx, abd-A, Abd-B) activate vvl and trh to form the tracheal network. As Oncopeltus develops glands in both the head (SG and PG), and the posterior abdomen (ScG), we asked how much of the Drosophila model applies to Oncopeltus. We began by studying the effect of Scr knockdown on vvl expression, as PG development is initiated in the labial segment—the primary domain of Scr expression (21). Compared to WT, the vvl signal that marks the PG is completely lost in Scr RNAi embryos (Fig. 8A, asterisks and A′). To confirm the functional significance of the observed absence of vvl, we utilized phm as a PG-specific marker (18) (Fig. 8B′ and SI Appendix, Fig. S1). In vvl RNAi embryos, phm expression is also lost (Fig. 8B, asterisk). Together, these results demonstrate that Scr and vvl are essential for PG development.

Fig. 8.

Hox gene regulation of gland organogenesis. (A and A′) vvl expression in the PG is lost in Scr RNAi (asterisks). (B and B′) phm expression in the PG is also lost in vvl RNAi (asterisk). (C–E) While vvl is only lost from the excretory cells of the ScG (red asterisks) in abd-A RNAi embryos, it is lost from both the excretory cells (red asterisks) and the duct cells (white asterisks) in Ubx/abd-A RNAi embryos. White arrowheads in C and E point to the duct cells; red arrowheads in E point to the excretory cells. (F and F′) Compared to WT, the vvl signal is lost from the tracheal placodes and transformed into three cell clusters in the thorax (purple arrows) in Antp RNAi embryos. (F″) Magnification (40×) of the vvl-expressing cell clusters showing connective ducts (purple arrowheads). A and A′ show embryos at ∼30% embryogenesis. All remaining panels show embryos between 65 and 75% embryogenesis. Anterior is Top in A and A′. Anterior is Left in all remaining panels.

Given that the ScGs are located in A5–A6 (Fig. 6F), we examined the role of abd-A in their formation. Compared to WT (Fig. 8E), abd-A RNAi embryos exhibit a partial effect on vvl expression in the ScGs; loss of signal is observed only in the secretory cells (Fig. 8C, asterisks), but not in the duct cells (Fig. 8C, arrowheads). In light of this result, we next asked whether Ubx, which is weakly expressed in the posterior abdomen (44), may also be involved in ScG development. In Ubx/abd-A RNAi embryos, we now observe a complete loss of vvl signal (Fig. 8D, asterisks), indicating that both of the Hox genes are indeed involved in ScG organogenesis. This observed effect in the embryos is consistent with an earlier report of ScG defects in moderate phenotypes of Ubx/abd-A RNAi first nymphs (19). Overall, the findings presented here further extend insights from Drosophila and demonstrate aspects of gland development in insects. The role of Scr in the formation of PGs, via activation of vvl, seems to represent a conserved function in endocrine gland regulation in insects. The finding that Ubx and abd-A are involved in ScG formation, also via activation of vvl, reveals a function of posterior Hox genes in exocrine gland development. In Drosophila these genes can induce tracheal, but not glandular, formation (8). Hence, we can now extend the current paradigm regarding insect gland organogenesis to include both head and trunk Hox genes as regulators of both the endocrine and exocrine glands.

Finally, we sought to further characterize the role of Antp in tracheal system development by examining its regulation of vvl. As we have shown in Fig. 3A, Antp RNAi results in a complete loss of trh signal in the thorax. As vvl requires trh for its continued expression (SI Appendix, Fig. S5B), we expected to observe a similar loss of vvl in those embryos. Contrary to this prediction, vvl signal is not only present but it displays a novel thoracic pattern, encompassing an oval-shaped cell cluster located at the base of each thoracic leg (Fig. 8F, purple arrows). Additionally, a detailed examination of these structures reveals that each is connected to a duct (Fig. 8F″, purple arrowheads). Note that outside of the thorax (in PGs and abdominal placodes), vvl expression is unaltered and WT-like. The appearance of these structures in Antp knockdowns, but not in trh RNAi embryos (SI Appendix, Fig. S5B), suggests that the observed vvl expression is not due to the absence of trh in Antp RNAi, but to the absence of Antp itself. Furthermore, the fact that trh expression is lost in Antp RNAi indicates that the vvl-expressing clusters are not malformed tracheal cells.

Studies in Drosophila have shown that, in the absence of trh and under the regulation of head Hox genes, vvl takes on a glandular fate (8). Therefore, we tested if these vvl-expressing cell clusters may be ectopic endocrine glands induced by the expansion of either Scr or Dfd into the thorax upon Antp knockdown. As illustrated in SI Appendix, Fig. S6 A–D, neither Scr nor Dfd expand into the thorax of Antp RNAi embryos. These results reveal that, in Oncopeltus, the initial activation of vvl in the thorax is independent of Hox genes, featuring a distinct pattern composed of three oval-shaped cell clusters. This pattern may represent the default state of vvl in the thorax. In this scenario, the input from Antp, and its consequential activation of trh, would then lead to vvl expression in the trachea instead.

The discovery of the default vvl pattern in Oncopeltus thorax is intriguing, raising questions about the origins and function of the three cell clusters. At present, the lack of phm expression in these cell clusters (SI Appendix, Fig. S6F) shows that they are not endocrine glands, but it does not exclude the possibility that they may represent nonfunctional vestiges that once had a glandular function. At the same time, the presence of ducts (Fig. 8F″, purple arrowheads) is suggestive of a putative relationship to exocrine glands. Several crustacean groups feature serially repeated glands in the postcephalic region (45–47). Particularly, in Cephalocarida (47), these glands are restricted to the thorax and located laterally at the limb base—similar to the location of vvl clusters in Oncopeltus. Additionally, they are composed of podocytes that function in hemolymph filtering and are homologous to the osmoregulatory maxillary glands. As cephalocarids are considered a sister taxa to insects (48), it is tempting to speculate that the last common ancestor of insects and crustaceans might have possessed similar excretory organs in its dorsal trunk. It was previously proposed that the insect–crustacean ancestor may have developed endocrine glands and respiratory organs (external gills) from segmentally repeated precursors (49). Along those lines, finding that the exocrine glands of Oncopeltus also express vvl and are under the regulation of Hox genes (Figs. 6 and 8), may be an indication that the exocrine glands develop from the same homologous precursors. This possibility is consistent with the facts that the gills of mayfly larvae, and the epipods/gills of the crustacean Artemia, have osmoregulatory functions (50–52) and, moreover, the gills and exocrine glands of crustaceans share a similar genetic network (i.e., they both express trh and vvl) (52–54). Genetic and molecular studies utilizing semiaquatic insects that possess trachea, gills, and osmoregulatory organs (55), may be especially informative in elucidating the developmental mechanisms that facilitated the evolution of a tracheal system in terrestrial arthropods.

Materials and Methods

Cloning and In Situ Hybridization.

Detailed cloning of Oncopeltus trh, vvl, ct, en, phm, Antp, and Abd-B, primer sequences, GenBank accession nos., and gene fragment length are provided in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods and Table S1. All remaining genes used in this study were previously described (21, 23, 44). All RNA probes were synthesized using previously described protocols (44, 56, 57). For a detailed description, see SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

dsRNA Synthesis and RNAi.

dsRNA synthesis and RNAi injections were performed as described (21). A full description of the injected concentrations and the generated range of phenotypic effects and lethality is provided in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

Lactic Acid Immersions.

Oncopeltus nymphs and adults were immersed in 100% lactic acid following Ruan et al. (58). For modifications and microscopy details, see SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

Data Availability Statement.

All gene sequences were deposited in the GenBank database (accession nos. MN549348–MN549353) and are listed in SI Appendix, Table S1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank two anonymous reviewers whose careful reading and thoughtful comments greatly improved this manuscript. We also wish to thank Jim Marden and Markus Friedrich for their critical reading of the text. This work was in part supported by National Science Foundation EArly-concept Grants for Exploratory Research grant 1838291 to A.P. and the 2018 Richard Barber Interdisciplinary Research Program award to A.P. and L.H.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The sequence reported in this paper has been deposited in the GenBank database (accession nos. MN549348–MN549353).

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1908975117/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Manning G., Krasnow M. A., “Development of the Drosophila tracheal system” in The development of Drosophila Melanogaster, Bate M., Arias A. M., Eds. (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, New York, 1993), pp. 609–685. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Isaac D. D., Andrew D. J., Tubulogenesis in Drosophila: A requirement for the trachealess gene product. Genes Dev. 10, 103–117 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson M. G., Perkins G. L., Chittick P., Shrigley R. J., Johnson W. A., drifter, a Drosophila POU-domain transcription factor, is required for correct differentiation and migration of tracheal cells and midline glia. Genes Dev. 9, 123–137 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Celis J. F., Llimargas M., Casanova J., Ventral veinless, the gene encoding the Cf1a transcription factor, links positional information and cell differentiation during embryonic and imaginal development in Drosophila melanogaster. Development 121, 3405–3416 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayashi S., Kondo T., Development and function of the Drosophila tracheal system. Genetics 209, 367–380 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sánchez-Herrero E., Vernós I., Marco R., Morata G., Genetic organization of Drosophila bithorax complex. Nature 313, 108–113 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu N., Castelli-Gair J., Study of the posterior spiracles of Drosophila as a model to understand the genetic and cellular mechanisms controlling morphogenesis. Dev. Biol. 214, 197–210 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sánchez-Higueras C., Sotillos S., Castelli-Gair Hombría J., Common origin of insect trachea and endocrine organs from a segmentally repeated precursor. Curr. Biol. 24, 76–81 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whitten J. M., The post-embryonic development of the tracheal system in Drosophila melanogaster. Q. J. Microsc. Sci. 98, 123–150 (1957). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pitsouli C., Perrimon N., Embryonic multipotent progenitors remodel the Drosophila airways during metamorphosis. Development 137, 3615–3624 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sato M., Kitada Y., Tabata T., Larval cells become imaginal cells under the control of homothorax prior to metamorphosis in the Drosophila tracheal system. Dev. Biol. 318, 247–257 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weaver M., Krasnow M. A., Dual origin of tissue-specific progenitor cells in Drosophila tracheal remodeling. Science 321, 1496–1499 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu P. Z., Kaufman T. C., Kruppel is a gap gene in the intermediate germband insect Oncopeltus fasciatus and is required for development of both blastoderm and germband-derived segments. Development 131, 4567–4579 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Auman T., et al. , Dynamics of growth zone patterning in the milkweed bug Oncopeltus fasciatus. Development 144, 1896–1905 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Miguel C., Linsler F., Casanova J., Franch-Marro X., Genetic basis for the evolution of organ morphogenesis: The case of spalt and cut in the development of insect trachea. Development 143, 3615–3622 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Medved V., et al. , Origin and diversification of wings: Insights from a neopteran insect. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 15946–15951 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sánchez-Higueras C., Hombría J. C., Precise long-range migration results from short-range stepwise migration during ring gland organogenesis. Dev. Biol. 414, 45–57 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Warren J. T., et al. , Phantom encodes the 25-hydroxylase of Drosophila melanogaster and Bombyx mori: A P450 enzyme critical in ecdysone biosynthesis. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 34, 991–1010 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Angelini D. R., Liu P. Z., Hughes C. L., Kaufman T. C., Hox gene function and interaction in the milkweed bug Oncopeltus fasciatus (Hemiptera). Dev. Biol. 287, 440–455 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng Z., Khoo A., Fambrough D. Jr, Garza L., Booker R., Homeotic gene expression in the wild-type and a homeotic mutant of the moth Manduca sexta. Dev. Genes Evol. 209, 460–472 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chesebro J., Hrycaj S., Mahfooz N., Popadić A., Diverging functions of Scr between embryonic and post-embryonic development in a hemimetabolous insect, Oncopeltus fasciatus. Dev. Biol. 329, 142–151 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahfooz N. S., Li H., Popadić A., Differential expression patterns of the hox gene are associated with differential growth of insect hind legs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 4877–4882 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hrycaj S., Mihajlovic M., Mahfooz N., Couso J. P., Popadić A., RNAi analysis of nubbin embryonic functions in a hemimetabolous insect, Oncopeltus fasciatus. Evol. Dev. 10, 705–716 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carroll S. B., Laymon R. A., McCutcheon M. A., Riley P. D., Scott M. P., The localization and regulation of Antennapedia protein expression in Drosophila embryos. Cell 47, 113–122 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Struhl G., White R. A., Regulation of the Ultrabithorax gene of Drosophila by other bithorax complex genes. Cell 43, 507–519 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Copf T., Rabet N., Averof M., Knockdown of spalt function by RNAi causes de-repression of Hox genes and homeotic transformations in the crustacean Artemia franciscana. Dev. Biol. 298, 87–94 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lovegrove B., et al. , Coordinated control of cell adhesion, polarity, and cytoskeleton underlies Hox-induced organogenesis in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 16, 2206–2216 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pinto P. B., Espinosa-Vázquez J. M., Rivas M. L., Hombría J. C., JAK/STAT and Hox dynamic interactions in an organogenetic gene cascade. PLoS Genet. 11, e1005412 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown S., Hu N., Hombría J. C., Identification of the first invertebrate interleukin JAK/STAT receptor, the Drosophila gene domeless. Curr. Biol. 11, 1700–1705 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sotillos S., Espinosa-Vázquez J. M., Foglia F., Hu N., Hombría J. C., An efficient approach to isolate STAT regulated enhancers uncovers STAT92E fundamental role in Drosophila tracheal development. Dev. Biol. 340, 571–582 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hartenstein V., Campos-Ortega J. A., Fate-mapping in wild-type Drosophila melanogaster. Rouxs Arch. Dev. Biol. 194, 181–195 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewis E. B., A gene complex controlling segmentation in Drosophila. Nature 276, 565–570 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Castelli Gair Hombría J., Rivas M. L., Sotillos S., Genetic control of morphogenesis–Hox induced organogenesis of the posterior spiracles. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 53, 1349–1358 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martinez-Arias A., The Antennapedia gene is required and expressed in parasegments 4 and 5 of the Drosophila embryo. EMBO J. 5, 135–141 (1986). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beeman R. W., Stuart J. J., Brown S. J., Denell R. E., Structure and function of the homeotic gene complex (HOM-C) in the beetle, Tribolium castaneum. BioEssays 15, 439–444 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lewis D. L., DeCamillis M., Bennett R. L., Distinct roles of the homeotic genes Ubx and abd-A in beetle embryonic abdominal appendage development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 4504–4509 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown S., Hu N., Hombría J. C., Novel level of signalling control in the JAK/STAT pathway revealed by in situ visualisation of protein-protein interaction during Drosophila development. Development 130, 3077–3084 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chung S., Chavez C., Andrew D. J., Trachealess (Trh) regulates all tracheal genes during Drosophila embryogenesis. Dev. Biol. 360, 160–172 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hartenstein V., The neuroendocrine system of invertebrates: A developmental and evolutionary perspective. J. Endocrinol. 190, 555–570 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boube M., Llimargas M., Casanova J., Cross-regulatory interactions among tracheal genes support a co-operative model for the induction of tracheal fates in the Drosophila embryo. Mech. Dev. 91, 271–278 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zelzer E., Shilo B. Z., Cell fate choices in Drosophila tracheal morphogenesis. BioEssays 22, 219–226 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zelzer E., Shilo B. Z., Interaction between the bHLH-PAS protein Trachealess and the POU-domain protein Drifter, specifies tracheal cell fates. Mech. Dev. 91, 163–173 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Certel K., Anderson M. G., Shrigley R. J., Johnson W. A., Distinct variant DNA-binding sites determine cell-specific autoregulated expression of the Drosophila POU domain transcription factor drifter in midline glia or trachea. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 1813–1823 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mahfooz N., Turchyn N., Mihajlovic M., Hrycaj S., Popadić A., Ubx regulates differential enlargement and diversification of insect hind legs. PLoS One 2, e866 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wright K. A., The fine structure of the nephrocyte of the gills of two marine decapods. J. Ultrastruct. Res. 10, 1–13 (1964). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Doughtie D. G., Rao K. R., The syncytial nature and phagocytic activity of the branchial podocytes in the grass shrimp, Palaemonetes pugio. Tissue Cell 13, 93–104 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hessler R. R., Elofsson R., Segmental podocytic excretory glands in the thorax of Hutchinsoniella macracantha (Cephalocarida). J. Crustac. Biol. 15, 61–69 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Regier J. C., et al. , Arthropod relationships revealed by phylogenomic analysis of nuclear protein-coding sequences. Nature 463, 1079–1083 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grillo M., Casanova J., Averof M., Development: A deep breath for endocrine organ evolution. Curr. Biol. 24, R38–R40 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nowghani F., et al. , Impact of salt-contaminated freshwater on osmoregulation and tracheal gill function in nymphs of the mayfly Hexagenia rigida. Aquat. Toxicol. 211, 92–104 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Holiday C. W., Salinity-induced changes in branchial Na+/K+-ATPase activity and transepithelial potential differences in the brine shrimp Artemia salina. J. Exp. Biol. 151, 279–296 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mitchell B., Crews S. T., Expression of the Artemia trachealess gene in the salt gland and epipod. Evol. Dev. 4, 344–353 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Franch-Marro X., Martín N., Averof M., Casanova J., Association of tracheal placodes with leg primordia in Drosophila and implications for the origin of insect tracheal systems. Development 133, 785–790 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang J. Q., et al. , Molecular cloning and its expression of trachealess gene (As-trh) during development in brine shrimp, Artemia sinica. Mol. Biol. Rep. 39, 1659–1665 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brittain J. E., Biology of mayflies. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 27, 119–147 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li H., Popadić A., Analysis of nubbin expression patterns in insects. Evol. Dev. 6, 310–324 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu P., Kaufman T. C., In situ hybridization of large milkweed bug (Oncopeltus) tissues. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2009, pdb.prot5262 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ruan Y., et al. , Visualisation of insect tracheal systems by lactic acid immersion. J. Microsc., 10.1111/jmi.12711 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All gene sequences were deposited in the GenBank database (accession nos. MN549348–MN549353) and are listed in SI Appendix, Table S1.