Significance

Exosomes are biological nanocarriers that offer several advantages over existing drug delivery vehicles because of their specialized abilities in intercellular communication. Attempts are being made to mimic and harness exosomes for exogenous drug delivery. However, exosomes have several inherent limitations that hinder their application as universal drug carriers. In this work, exosome polymer hybrids were prepared by precisely engineering the exosome surface with different synthetic polymers. These polymers can be easily tuned and modified to enhance the physicochemical profile of exosomes and overcome the existing limitations associated with ex vivo and in vivo stability and activity.

Keywords: polymer, ATRP, exosome, polymer biohybrid

Abstract

Exosomes are emerging as ideal drug delivery vehicles due to their biological origin and ability to transfer cargo between cells. However, rapid clearance of exogenous exosomes from the circulation as well as aggregation of exosomes and shedding of surface proteins during storage limit their clinical translation. Here, we demonstrate highly controlled and reversible functionalization of exosome surfaces with well-defined polymers that modulate the exosome’s physiochemical and pharmacokinetic properties. Using cholesterol-modified DNA tethers and complementary DNA block copolymers, exosome surfaces were engineered with different biocompatible polymers. Additionally, polymers were directly grafted from the exosome surface using biocompatible photo-mediated atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP). These exosome polymer hybrids (EPHs) exhibited enhanced stability under various storage conditions and in the presence of proteolytic enzymes. Tuning of the polymer length and surface loading allowed precise control over exosome surface interactions, cellular uptake, and preserved bioactivity. EPHs show fourfold higher blood circulation time without altering tissue distribution profiles. Our results highlight the potential of precise nanoengineering of exosomes toward developing advanced drug and therapeutic delivery systems using modern ATRP methods.

Exosomes are a subclass of lipid bilayer-enclosed extracellular vesicles (EVs) that play a crucial role in intercellular communication (1–3). They are secreted by most cell types in the body and are known to interact with recipient cells in several ways, including surface receptor interactions, membrane fusion, receptor-mediated endocytosis, phagocytosis and/or micropinocytosis (4, 5). Their nanoscopic size (30 to 150 nm), high biocompatibility, low immunogenicity (depending on the cell source), and ability to cross biological barriers, including the blood–brain barrier, make them an ideal vehicle for exogenous drug delivery (6–9). Over the last decade, multiple studies have shown effective utility of exosomes for the delivery of small molecule drugs, proteins, nucleic acids and nanoparticles for the treatment of several diseases (10–12). Although initial progress toward their clinical translation has been made, the need for a more robust platform persists. The therapeutic potential of exosomes is largely restricted due to their low exogenous drug-loading efficiency and limited ex vivo stability (13, 14). Moreover, systemically administered exosomes suffer from rapid clearance from blood in 2 to 20 min postinjection that is poorly suited for longer therapeutic action (15, 16).

Engineering exosomes to incorporate nonnative moieties or materials can augment their therapeutic capabilities (17–19). While bioengineering methods by genetically modifying the exosome-secreting cells have been explored, such approaches require careful design and expensive reagents, yet suffer from low incorporation efficiency and limited scalability. Alternatively, ex vivo engineering of exosome surfaces with synthetic macromolecules is a powerful approach to easily modulate their surface interactions and consequently alter or enhance their biochemical and physicochemical properties.

Here, we create a polymer-based platform that expands the structural repertoire of engineered exosomes and addresses the shortcomings of the ex vivo and in vivo stability of exosome-based therapeutics. We combine our previously reported method for rapid and on-demand functionalization of exosomes through DNA tethers (20) with atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP) techniques (21–23) to engineer exosome polymer hybrids (EPHs). These EPHs display significantly enhanced stability and pharmacokinetics. We explore the preparation methods for EPHs by either tethering preformed DNA block copolymers (DNABCPs) onto the exosome membrane (“grafting-to”) or by grafting polymers directly from the exosomal surface (“grafting-from”) (Fig. 1) using DNA initiators. These membrane-tethering approaches allow precise control over the polymer length, composition, and loading on the exosome surface and thereby show minimal effect on the accessibility of surface proteins or other membrane-tethered agents that may be used for targeted delivery. We show that the cellular uptake and bioactivity of native and drug-loaded exosomes are preserved following polymer functionalization. Tethered polymers enhance the stability of exosomes under different storage conditions, including in the presence of proteolytic enzymes. The blood circulation half-lives of EPHs are significantly increased using different polymers, while maintaining their intrinsic tissue-targeting properties.

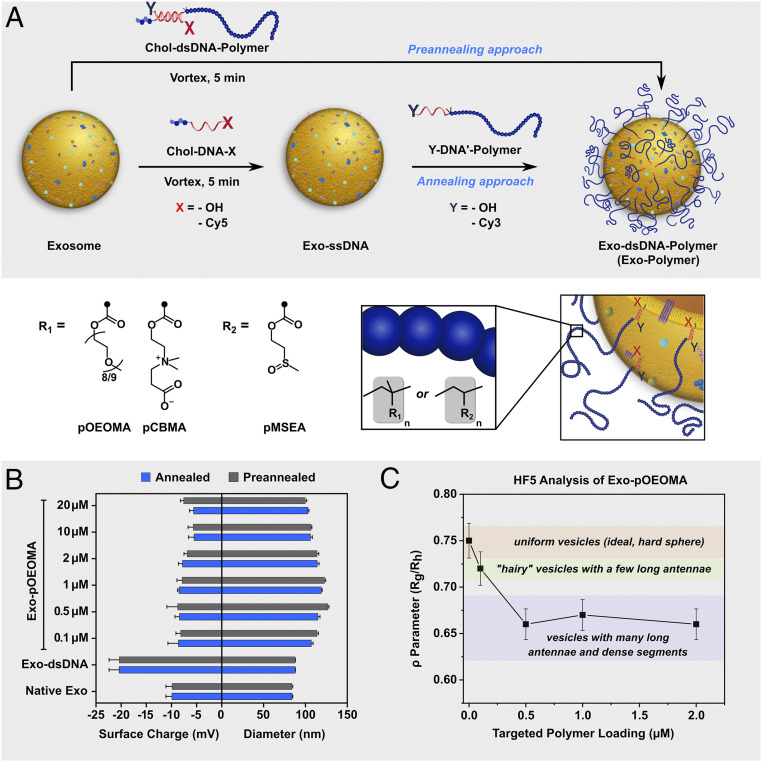

Fig. 1.

Preparation of EPHs using DNA tethers. Chol-DNA embeds into the exosome membrane to form Exo-ssDNA (single-stranded DNA) species with DNA strands orienting outward. Hybridization of complementary DNA block copolymer (DNA′-Polymer) to the DNA tethers on Ex-ssDNA species generates Exo-dsDNA-Polymer (Exo-Polymer) by the “grafting-to” strategy. Alternatively, for the “grafting-from” strategy, a complementary DNA initiator (DNA′-Initiator) functionalized with the α-bromoisobutyrate group is hybridized with the DNA tethers, followed by surface-initiated ATRP to prepare Exo-Polymer species.

Results

EPHs Using a “Grafting-To” Strategy.

We recently reported that exosomes can be readily augmented using cholesterol-modified DNA tethers (Chol-DNA) to include different bioactive cargoes (20). These amphiphilic Chol-DNA tethers partition into the exosome membrane and negatively charged DNA remains displayed outside the membrane for further engineering. Here, we used a “grafting-to” strategy that employs noncovalent interactions between DNA tethers on the exosome surface and complementary DNA block copolymers to prepare EPHs (Exo–double-stranded DNA [dsDNA]–Polymer or Exo-Polymer) (Fig. 2A). An 18-mer DNA tether, synthesized with cholesterol and an oligomer with six ethylene glycol units as a spacer on the 5′-end (Chol-DNA) (SI Appendix, Table S1), is gently vortexed with exosomes at room temperature (25 °C) for 5 min to prepare DNA-tethered exosomes (Exo–single-stranded DNA [ssDNA]). DNA tethers serve as a handle on the exosome surface to anneal complementary DNABCPs, to generate EPHs (annealing approach). Alternatively, Chol-DNA can be annealed with the complementary sequence in DNA′-Polymer before tethering to the exosome surface to generate EPHs (preannealing approach). In initial studies, we selected oligo(ethylene oxide) methacrylate (OEOMA, Number-average molecular weight (Mn) = 500) as the monomer. The complementary DNA′-pOEOMA30K (SI Appendix, Table S2) was prepared using a 23-mer DNA macroinitiator with a 5′-α-bromoisobutyrate group (DNA′-iBBr) (SI Appendix, Table S1), as previously reported (24). Varying the concentration of the Chol-DNA and DNA′-poly(OEOMA)30K [pOEOMA30K] strands (from 0.1 µM to 20 µM) with a fixed amount of exosomes isolated from J774A.1 cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S1), we targeted the preparation of Exo-pOEOMA hybrids with varied polymer loadings.

Fig. 2.

”Grafting-to” strategy to prepare EPHs. (A) Schematic showing polymer functionalization of the exosome membrane by the annealing and preannealing approach. Chol-DNA-X embeds into the exosome membrane (Exo-ssDNA), and complementary Y-DNA′-polymer can be hybridized to Exo-ssDNA to prepare EPHs by the annealing approach. Alternatively, for the preannealing approach, Chol-DNA-X and Y-DNA′-Polymer can be hybridized before tethering to exosomes. (B) Plot showing size and surface charge of EPHs prepared by both the annealing and preannealing approach with varying surface loading of DNA′-pOEOMA30K (0 µM to 20 µM). Bars indicate mean ± SEM (n = 3 independent experiments). (C) Plot showing the ρ parameter (Rg/Rh) of Exo-pOEOMA species with varying surface polymer loading. Rg and Rh values were determined by the HF5 method (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Bars indicate mean ± SD (n = 4 independent measurements).

Both annealing and preannealing approaches showed an increase in the average diameter of the vesicles after polymer functionalization (Fig. 2B; see also SI Appendix, Fig. S2). However, in the preannealing approach at the higher targeted loading of 20 µM, a secondary population of potentially free polymer tethers was observed around 20 nm (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). The surface charge of the resulting exosomes significantly decreased due to the presence of DNA tethers on the surface (Exo-dsDNA); however, subsequent polymer functionalization allowed a similar surface charge as native exosomes (Fig. 2B). Additionally, control studies confirmed the absence of any nonspecific attachment of DNA′-pOEOMA30K to the exosome surface. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements showed no change in the average diameter of the exosomes after incubation with DNA′-pOEOMA30K (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). We further characterized the Exo-pOEOMA using the hollow fiber flow-field-flow fractionation (HF5) technique, which allows the analysis of very low analyte concentrations. HF5 is a subtechnique of the flow-field-flow fractionation recently reported as highly suitable for investigation of exosomes (25) (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). In this study, each measurement with multidetector HF5 contains a wealth of information about changes in size and conformation (from DLS and multiangle light scattering [MALS] detectors) of the exosomes, in addition to quantification of the sequential modification of the exosomes (using four defined wavelengths of the ultraviolet (UV)-visible detector). The analytical power of multidetector field-flow fractionation (FFF) was recently demonstrated for delicate nanoparticles (26, 27). Using preannealed Chol-DNA and Cyanine3-DNA′-pOEOMA30K, Exo-pOEOMA hybrids were prepared with varied polymer loadings. HF5 fractograms showed an increase in the retention times of exosomes after polymer functionalization (SI Appendix, Fig. S5A). At the peak maximum of EPHs, which represents the major sample population, the hydrodynamic radius (Rh) was higher than the radius of gyration (Rg), indicating the spherical and dense nature of EPHs (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 B and C). Further, the shape parameter (ρ), calculated from Rg/Rh at peak maximum, decreased after polymer functionalization, from 0.77 (typical for uniform, homogenous and hard spheres) for native exosomes to 0.65 for EPHs. The latter value is characteristic for large hard spheres with many dense segments combined with few long chains on the outer surface, which influence the diffusion of the particles by hindering their motion (Fig. 2C and SI Appendix, Fig. S5A) (28–30). The average number of polymer chains per exosome varies from ∼2,000 to 8,000, depending on the targeted loading (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). Further, the polymer chains did not dissociate after 1-wk storage and thawing from a −20 °C freezer (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). A subpopulation of free polymer strands was observed when targeted polymer loading on the exosome surface was increased, suggesting incomplete partitioning of amphiphilic Chol-dsDNA-pOEOMA30K species into the exosome membrane (SI Appendix, Figs. S7 and S8).

Following our evaluation of the preparation of EPHs using Exo-pOEOMA hybrids, we explored other different biocompatible polymers in EPHs by the same “grafting-to” strategy. Complementary DNABCPs (SI Appendix, Table S2) were prepared using carboxybetaine methacrylate (CBMA) as monomer to generate EPHs with zwitterionic polymer functionalization (Exo-pCBMA hybrids). We also examined a sulfoxide-based water-soluble polymer, poly(2-(methylsulfinyl)ethyl acrylate) (pMSEA) (31), to prepare Exo-pMSEA hybrids. DLS analyses showed a clear increase in the average size of resulting EPHs while surface charge was comparable to native exosomes (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). Our attempts to prepare EPHs with cationic polymers, using 2-(dimethylamino)ethyl methacrylate (DMAEMA) as monomer, resulted in multiple subpopulations (SI Appendix, Fig. S9B). Likely, the electrostatic interactions between poly(DMAEMA) [pDMAEMA], the negatively charged exosome membrane, and the DNA strands interfered with the membrane insertion ability of the tethers.

Exosome Polymer Hybrids Using a “Grafting-From” Strategy.

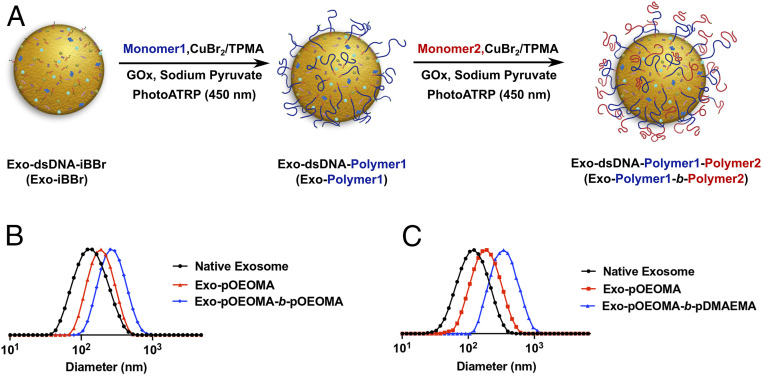

The exosome surface can be functionalized with preannealed Chol-DNA and DNA′-iBBr strands to prepare exosome macroinitiator (Exo-dsDNA-iBBr or Exo-iBBr). This functionalization allows the preparation of EPHs by grafting well-controlled polymers directly from the exosome surface (Fig. 3A). This strategy requires careful and biocompatible polymerization conditions to maintain the integrity of exosomes. As all reversible-deactivation radical polymerization (RDRP) methods are inhibited by the presence of oxygen, they require rigorous degassing procedures such as “free-pump-thaw” cycles (32). Our initial efforts to bubble inert gases through the exosome polymerization reactions led to degradation of exosomes due to shear stress (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). We therefore turned to newly developed glucose oxidase (GOx)-mediated oxygen-tolerant ATRP. In this method, added glucose and sodium pyruvate convert dissolved oxygen to carbon dioxide during the course of the polymerization reactions, obviating the need for physical degassing (33). For polymerizations, OEOMA500 and CuBr2/Tris(2-pyridylmethyl)amine) (TPMA) were chosen as the monomer and catalyst, respectively. Exo-iBBr, prepared with 20 µM targeted surface loading, were irradiated under blue light (450 nm, 4.5 mW/cm2) for 15 min for grafting well-controlled polymers from the exosome surface by GOx-mediated Photo-ATRP (34). The resulting Exo-pOEOMA hybrids showed a clear shift in the average diameter as assayed by DLS while the overall surface charge increased post-polymerization (Fig. 3B). We observed no cytotoxic effects of Exo-pOEOMA on the viability of human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S11). In order to confirm the living nature of the polymerization process, we grafted another pOEOMA blockw from the purified Exo-pOEOMA hybrids to prepare Exo-pOEOMA-b-pOEOMA hybrids (Fig. 3B). More significantly, EPHs with cationic polymers that could not be achieved by the “grafting-to” strategy were also prepared by grafting a cationic pDMAEMA block from Exo-pOEOMA hybrids (Fig. 3C). DLS measurements confirmed the preparation of well-defined EPHs with maintained structural integrity (SI Appendix, Table S3).

Fig. 3.

”Grafting-from” strategy to prepare EPHs. (A) Schematic showing the grafting of polymers directly from the exosome surface by oxygen-tolerant blue light-mediated PhotoATRP. The ATRP initiator tethered to the exosome lipid membrane (Exo-dsDNA-iBBr) initiates polymer chains to prepare homopolymers (Exo-dsDNA-Polymer1), which can be subsequently chain extended to prepare block copolymers (Exo-dsDNA-Polymer1-b-Polymer2). (B) DLS plot showing size distribution of native exosomes and EPHs after grafting block copolymer with two pOEOMA blocks from the exosome surface. (C) Plot showing size distribution of native exosomes and EPHs after grafting pOEOMA from the exosome surface and further extending the polymer chains with a cationic pDMAEMA block.

Accessibility of Exosomal Surface Proteins, DNA Tethers, and Targeting Agents.

The attachment of polymers on the exosome surfaces can affect the accessibility of surface proteins, potentially affecting their bioactivity. Therefore, we assessed the accessibility of an exosomal surface marker protein, CD63, in EPHs. Binding studies of dye-labeled exosomes and anti-CD63 beads allow quantification of exosome surface CD63 protein’s accessibility toward binding. Further, accessibility can vary depending on the polymer type, surface loading, and polymer length. Using Cyanine 5 (Cy5)-labeled DNA tether (Chol-DNA-Cy5) (SI Appendix, Table S1) and complementary DNA′-pOEOMA strands (SI Appendix, Table S2) with different molecular weight (MW) polymers (Mn = 10,000, 20,000, 30,000 g/mol), Exo-pOEOMA hybrids of varying polymer lengths and surface loading were prepared. Total surface DNA tether loading was kept constant at 10 µM for all these Exo-pOEOMA hybrids while the polymer surface loading was varied (0 to 5 µM) through complementary DNA′-pOEOMA (Mn = 10,000, 20,000, 30,000 g/mol) strands. All Exo-pOEOMA hybrids were incubated with anti-CD63 beads and analyzed by flow cytometry. Exo-pOEOMA10K hybrids showed binding efficiency similar to the Exo-dsDNA control without any polymer while no significant effect of surface DNA tether loading was observed (Fig. 4B; blue bars). However, longer polymer chains in Exo-pOEOMA20K and Exo-pOEOMA30K hybrids with a surface polymer loading of 1 µM showed a decrease in the binding efficiency around 19% and 50%, respectively (Fig. 4 C and D; blue bars). Further, a sequential drop in Exo-pOEOMA binding to the anti-CD63 beads was observed with increased surface polymer loading for the 20,000 and 30,000 polymers.

Fig. 4.

Assessment of surface accessibility of EPHs. (A) Schematic showing the exosome surface protein CD63-mediated binding of Cy5-labeled Exo-pOEOMA (Exo-pOEOMA-Cy5) onto anti-CD63 beads. The binding of Exo-pOEOMA-Cy5 species was evaluated with varying MWs (Mn = 10,000, 20,000, 30,000 g/mol) and surface loadings (0 to 5 µM) of pOEOMA. (Inset) Polymer surface loadings by varying DNA′-pOEOMA concentration can influence the accessibility of CD63 protein on the Exo-pOEOMA-Cy5 surface. (B–D) Graphs showing mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of anti-CD63 beads-bound Exo-pOEOMA-Cy5 with different lengths of pOEOMA—10,000 (B), 20,000 (C), 30,000 (D)—and varying surface loadings of polymers. Accessibility of DNA tethers to nucleases is assessed by treating beads-bound Exo-pOEOMA with DNase-I for 1 h at 37 °C. The drop in the MFI postnuclease treatment highlights the degradation of DNA tethers. Bars indicate MFI ± SEM (n = 3 independent experiments). A.U. = arbitrary unit. (E) Schematic showing the binding assay of AS1411 aptamer-functionalized Exo-pOEOMA on the nucleolin protein-functionalized surface using QCM. (F) Plot showing frequency changes (ΔF) for the surface binding of Exo-pOEOMA-AS1411 species with constant loading of pOEOMA30K (1 µM) but varying AS1411 loading −1 µM (low) and 10 µM (high). Bars indicate the mean ± SEM (n = 3 independent experiments), ns, no significant difference; **P = 0.003; *P < 0.05.

In addition to the accessibility of surface proteins, we tested the accessibility of DNA tethers as their shielding from nucleases is crucial for maintaining effective EPHs. To investigate the nuclease stability of DNA tethers, we incubated the anti-CD63 beads-bound Exo-pOEOMA-Cy5 with DNase-I, an endonuclease that targets both single- and double-stranded DNA, and analyzed the drop in the Cy5 signal by flow cytometry. Control samples with no loaded polymer showed a complete cleavage of DNA tethers, highlighting their severe susceptibility to degradation. However, we observed nuclease resistance in Exo-pOEOMA10K and Exo-pOEOMA20K hybrids. This resistance was improved with increasing polymer surface loading (Fig. 4 B and C; gray bars). Interestingly, Exo-pOEOMA30K showed complete protection of DNA tethers against DNase-I, even at the minimum polymer loading of 0.1 µM, which amounts to just 1% of polymer tethers with respect to the total DNA tether loading (10 µM) on the exosome surface (Fig. 4D; gray bars). Taken together, our results revealed that pOEOMA of 20,000 and higher with surface loading at the concentration of 1 µM is optimal for balancing the accessibility of surface proteins while shielding the DNA tethers from nucleases.

We further investigated the effect of polymers on the accessibility and effectiveness of targeting agents displayed on the exosome surface. The AS1411 aptamer is a short G-quadruplex forming oligonucleotide which binds to nucleolin protein and can be used to target cancerous cells (35). Exo-pOEOMA30K hybrids with two different loadings of AS1411 aptamer were prepared, and their binding on a nucleolin-modified surface was analyzed using a quartz crystal microbalance (QCM) (36, 37) (Fig. 4 E and F). Complementary DNA′-AS1411 and DNA′-pOEOMA30K strands were used simultaneously to functionalize exosomes (Exo-pOEOMA-AS1411) with two different loadings of AS1411—1 µM (low) and 10 µM (high)—with a constant pOEOMA30K loading (1 µM). In the absence of any pOEOMA polymer, the two AS1411 surface loadings showed no difference in the binding of Exo-AS1411 to the QCM surface that was functionalized with the AS1411 receptor, nucleolin. In the presence of polymers, low surface binding was observed for Exo-pOEOMA-AS1411Low with low 1 µM AS1411 loading. However, with increased AS1411 surface loading of 10 µM (Exo-pOEOMA-AS1411High), higher binding that compensated for the surface shielding effect of the pOEOMA polymer was observed. These results further suggest that optimization of exosomal surface loading is critical for effective control over exosome interactions.

Exosomes with Reversible Polymer Functionalization.

In order to achieve reversible control over the polymer functionalization, we synthesized a photocleavable DNA tether (Chol-pc-DNA) (SI Appendix, Table S1) that incorporates a nitrophenyl group between the DNA and the 5′-cholesterol moiety (Fig. 5A). This tether and complementary DNABCPs provide access to EPHs with reversible polymer functionalization. To test the reversibility, Exo-pc-pOEOMA30K hybrids were prepared and analyzed before and after irradiation with UV light (365 nm, 5 mW/cm2). DLS results confirmed the removal of polymer from surface in just 2 min of UV light irradiation (SI Appendix, Fig. S12).

Fig. 5.

Effect of polymer functionalization on the stability of exosomes. (A) EPHs can be reversibly functionalized with polymers using a photocleavable DNA tether. The p-nitrophenyl group in between the cholesterol and DNA sequence induces reversibility to EPHs. (B) Plot showing percent total column eluant radioactivity (count/minute) of different size exclusion chromatography fractions of 125I-labeled native exosomes and EPHs after incubation with trypsin at 37 °C for 1 h. Shown is the stability of exosomal surface proteins against trypsin by size exclusion chromatography. EPHs prepared using photocleavable DNA tethers (Exo-pc-pOEOMA30K and Exo-pc-pCBMA) showed no degradation of surface proteins. After irradiation of EPHs with UV light (365 nm) for 2 min, removal of polymer from exosome surface showed protein degradation post 60-min incubation at 37 °C. (C) Plot showing the change in the average diameter of native exosomes and Exo-pOEOMA30K (1 µM polymer loading) after incubation at 4 °C and 37 °C in 1x PBS buffer for 30 d. The study was repeated four times, each with samples in triplicate. ns, no significant difference; ****P < 0.0001.

Exosomes with Enhanced Stability.

Using the photocleavable DNA tethers, the effect of polymer functionalization on the stability of exosomal surface proteins against proteases was analyzed. The exosomal surface proteins were radiolabeled with 125I. Both 125I-Exo-pc-pOEOMA30K and 125I-Exo-pc-pCBMA hybrids with photocleavable DNA tethers as well as native exosomes as control were treated with trypsin for 60 min at 37 °C. Degradation of surface proteins was evident from the shift of the radioactivity from the exosome fractions to the “protein” fractions using size exclusion chromatography. A clear shift in radioactivity occurred from the exosome fractions (10–12) to protein fractions (4–6) for native exosomes, highlighting trypsin-induced proteolysis of exosomal surface 125I-proteins (Fig. 5B). In contrast, 125I-Exo-pc-pOEOMA30K and 125I-Exo-pc-pCBMA showed high protein stability, with the major 125I signal being retained in the exosome fractions. However, a 2-min UV irradiation pretreatment to specifically remove exosome surface polymer, followed by incubation of 125I-EPHs with trypsin, resulted in a shift of radioactivity from exosome to protein fraction, demonstrating the proteolytic protection is under controlled reversibility.

The limited stability of native exosomes under storage conditions motivated the examination of the effect of polymers on the long-term storage stability of exosomes (13, 38). The size distribution profile was assessed using DLS to study the effect of storage conditions on the physical properties of exosomes. Native exosomes and Exo-pOEOMA30K with 1 µM loading were incubated for one month at different temperatures. DLS measurements showed that native exosomes aggregated at 4 °C, as evident by the increase in their size distribution profile, while 1-mo storage at 37 °C resulted in a broad size distribution profile of exosomes indicative of exosome surface protein shedding (SI Appendix, Fig. S13). In sharp contrast, Exo-pOEOMA30K hybrids exhibited a preserved uniform size distribution profile, with no apparent aggregation or protein shedding after 1-mo incubation at 4 °C or 37 °C (Fig. 5C).

Cellular Uptake of EPHs with Different Lengths and Composition.

To investigate whether polymer functionalization affects the internalization of exosomes, we examined the cellular uptake of various EPHs with HEK293 cells. Cells were incubated with native exosomes, exosomes with DNA tethers but without polymers (Exo-dsDNA), and Exo-pOEOMA hybrids with three different polymer lengths (10,000, 20,000, 30,000). We observed that all different Exo-pOEOMA hybrids internalized into the cells within 6 h, with a 20 to 40% drop observed in the internalization efficiency for Exo-pOEOMA30K hybrids (Fig. 6B). Further, we compared the effect of different polymers (pOEOMA, pCBMA, pMSEA) of similar polymer lengths on cellular uptake. Exo-pOEOMA30K, Exo-pCBMA, and Exo-pMSEA hybrids were incubated with HEK293 cells for 6 h. These cell internalization trials were also performed in the presence of two inhibitors, heparin and methyl-β-cyclodextrin, which are known to partially inhibit exosome internalization by blocking heparin sulfate proteoglycans and lipid raft-mediated processes, respectively (39). For all EPHs, we observed similar cellular uptake, with an ∼25 to 30% drop as compared to native exosomes (Fig. 6C). In the presence of the inhibitors, a significant drop was observed in the internalized fluorescence of both native exosomes and EPHs, highlighting similar uptake mechanisms.

Fig. 6.

Assessment of bioactivity of EPHs in vitro. (A) Schematic showing the in vitro assessment of bioactivity of EPHs and bioactive cargo-loaded EPHs. (B) Plot comparing the cell internalization efficiency of native exosomes and EPHs with different lengths of pOEOMA polymer (1 µM loading) in HEK293 cells after 6 h. (C) Plot showing the internalization efficiency of EPHs with different polymers—pOEOMA, pCBMA, pMSEA—in HEK293 cells after 6 h. To inhibit two major pathways of exosome internalization, cells were treated with heparin and methyl-β-cyclodextrin. A drop in the cellular uptake of both native exosomes and EPHs highlights a similar internalization mechanism. (D) Images showing the proangiogenesis property of MSC-derived exosomes and corresponding Exo-pOEOMA30K at 1 µM polymer loading. Similar increase in the branch points and tube length was observed in two cells lines—LECs and HUVECs. (E) Images showing the osteogenic property of BMP2-loaded exosomes and BMP2-loaded Exo-pOEOMA30K at 1 µM polymer loading. Both species promoted the expression of the ALP marker in 72 h. (F) Quantification of increase in the branch points and tube length in LECs and HUVECs by MSC-derived exosomes and Exo-pOEOMA30K species. (G) Plot showing the quantification of ALP expression by BMP2-loaded exosomes and Exo-pOEOMA30K species. (H) Plot showing the antiinflammatory effects of curcumin-loaded exosomes and curcumin-loaded Exo-pOEOMA30K at 1 µM polymer loading. Similar activity was observed for native exosomes and EPHs. All bars indicate mean ± SEM, n = 3 independent experiments. ***P < 0.001; ns, no significant difference.

We previously reported that the cellular uptake of exosomes can be altered using a targeting agent such as the AS1411 aptamer (20). We therefore investigated the cellular uptake of AS1411-functionalized Exo-pOEOMA30K hybrids in two cell lines, HEK293 and human pancreatic cancer cells (MiaPaCa2), to understand the effect of the polymers on the targeting ability of engineered exosomes. The cancerous MiaPaCa2 cell line is known to express high levels of nucleolin on the cell membrane that facilitates AS1411-mediated internalization whereas HEK293 cells that have no membrane-associated nucleolin serve as negative control (40, 41). Exosomes were simultaneously functionalized with pOEOMA and AS1411 at 1 µM loading (Exo-pOEOMA-AS1411Low) and incubated with cells for 6 h. Even in the presence of inhibitors (heparin and methyl-β-cyclodextrin), Exo-pOEOMA-AS1411 hybrids internalized in the MiaPaCa2 cells while HEK293 cells showed low cellular uptake, as expected (SI Appendix, Fig. S14). Further, pOEOMA functionalization led to around 40% reduction in the internalization efficiency of Exo-AS1411 with 1 µM loading, highlighting the shielding effects of the polymers on the exosome surface. Increasing the AS1411 loading to 10 µM with the same pOEOMA loading of 1 µM (Exo-pOEOMA-AS1411High) led to an ∼60% increase in cellular uptake (SI Appendix, Fig. S14). These results are consistent with the QCM analyses that show increased binding with higher AS1411 loading in the EPHs.

Angiogenesis through Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived EPHs.

Mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes are known to have angiogenic properties (42); therefore, we decided to evaluate the effects of polymer functionalization on the angiogenic capacity of EPHs. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs) were treated with MSC-derived Exo-pOEOMA30K hybrids at 1 µM polymer loading, and the cells were analyzed for tube length and number of branch points (Fig. 6 D and F). Both native exosomes and Exo-pOEOMA30K hybrids increased the tube length in HUVECs by 34% and 40%, respectively, as compared to untreated control (Fig. 6F). In LECs, tube length increased by 40% and 34% with native exosomes and Exo-pOEOMA30K hybrids, respectively. Similarly, both treatments also increased the branch points by similar efficiency in both cell lines, as compared to control. These results suggest that polymer grafting did not affect the angiogenic potential of MSCs exosomes.

Osteogenic Differentiation through BMP2-EPHs.

To evaluate the effect of the polymer on exosomes loaded with a cargo, we examined the osteogenic capacity of bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP2) loaded exosomes with and without polymer. The bioactivity of BMP2-exosomes was studied by assessing the induction of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) in C2C12 murine myoblast cells after treatment with exosomes. ALP is one of the early osteogenic differentiation markers. The results show that the ALP up-regulations in C2C12s treated with BMP2-Exo and BMP2-Exo-pOEOMA30K hybrids were not significantly different from each other, suggesting that polymer functionalization does not negatively affect the biological osteogenic activity of BMP2-exosomes (Fig. 6 E and G).

Antiinflammatory Properties of Curcumin-Loaded EPHs.

To probe the bioactivity of drug-loaded EPHs, exosomes isolated from J774A.1 cells were loaded with curcumin. We tested the potential of these exosomes or EPHs to down-regulate proinflammatory associated NF-κB expression in the RAW-Blue macrophage reporter cell line. This reporter cell line stably expresses a secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) gene inducible by NF-κB activation that can be detected colorimetrically. Our results indicate that both native J774A.1-derived curcumin-exosomes and J774A.1-derived curcumin-Exo-POEOMA30K counteracted NF-κB activation by bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), as shown in Fig. 6H. Moreover, there was no significant difference in NF-κB activation between native J774A.1-derived curcumin-exosomes and J774A.1-derived curcumin-Exo-POEOMA treatments, suggesting that the biological activity of curcumin-loaded exosomes can be preserved after polymer functionalization.

In Vivo Pharmacokinetics and Biodistribution of EPHs.

The serum clearance kinetics of EPHs was assessed by quantifying the ExoGlow signal in the mouse bloodstream as a function of time. Exosomes were labeled with the ExoGlow-Vivo EV Labeling Kit (Near infrared [IR]) according to the manufacturer’s instructions prior to polymer grafting. EPHs with three different types of polymers—pOEOMA30K, pCBMA, and pMSEA at 1 µM loading—were evaluated. The time 0 draw was done around 15 to 30 s (as quickly as manually feasible) postinjection although we noted that the maximum signal may have been there before then. Almost half of the fluorescence signal from native exosomes detected at time 0 (15 to 30 s) was distributed into tissues at around 30 min. Half of the native exosomes initially detected at time 0 had distributed to tissues by 15 min. At 120 min postinjection, 7.5% of the native exosome signal remained whereas, at 180 min, only 2.4% of the signal remained. In contrast all the three EPH samples showed longer blood circulation times (Fig. 7A). Approximately 50% of the initially injected exosome signal was detected at ∼1 h for Exo-pOEOMA, at 2 h for Exo-pCBMA, and at 15 min for Exo-pMSEA hybrids. At 3 h, almost 30% of Exo-POEOMA, 41% of Exo-pCBMA, and 20% of Exo-pMSEA hybrids remained in blood circulation. Whereas native and Exo-dsDNA was cleared from blood in about 3 h, even after 12 h, 10% of Exo-POEOMA, 24% of Exo-pCBMA, and 11% of Exo-pMSEA hybrids remained in blood circulation.

Fig. 7.

In vivo pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of EPHs. (A) Plot showing the percent fluorescent intensity of ExoGlow-labeled exosomes and EPHs (Exo-pOEOMA, Exo-pCBMA, Exo-pMSEA) in mice blood at different time intervals following intravenous injection through the tail vein. The results are expressed as mean ± SEM of eight mice. (B) Plot showing the percentage accumulation of exosome and EPHs in different organs of mice after 24 h. The results are expressed as mean ± SEM of six mice. GI, gastrointestinal.

Whole-organ images after 24 h postinjection through the tail vein showed that native exosomes accumulated in lungs (9.28%), liver (50.9%), pancreas (11.2%), and kidney (12.8%) while accumulation in the brain (0.9%) and heart (2.5%) were low (Fig. 7B and SI Appendix, Fig. S15). The organ distribution profiles of EPHs with different polymers were similar to that of native exosomes, suggesting that, although polymer functionalization increases blood circulation time, it does not change the intrinsic tissue distribution profile of exosomes.

Discussion

In this work, we have demonstrated a versatile method for the preparation of EPHs using membrane tethering of cholesterol-conjugated DNA strands. The use of DNA tethers establishes a sequence-specific control over the surface modification and enables multivalent functionalization. We used ATRP, a reversible-deactivation radical polymerization technique that allowed us to prepare well-defined polymers for exosome surface modification. ATRP shows low cross-reactivity with biomolecules and biological functional groups and maintains a low concentration of radicals in the system. As a result, ATRP and other RDRP methods have been widely employed in the preparation of polymer biohybrids from proteins, peptides, nucleic acids, and carbohydrates (22, 43–45). More recently, polymer functionalization of membrane enclosed systems like cells and liposomes have also been reported (46–48).

We explored two “grafting-to” approaches—annealing and preannealing—to introduce one DNA tether or a dsDNA tether with the polymer. Both approaches showed a similar size and surface charge of the prepared Exo-pOEOMA hybrids. In the preannealing approach, free polymer tethers were observed at high targeted surface loading. These are potentially due to the amphiphilic nature of Chol-dsDNA-pOEOMA species; nonetheless, HF5 studies showed that 2,000 to 8,000 polymer tethers can be grafted per particle. HF5 studies with shape (ρ) parameters in the range of 0.7 to 0.66 further highlight the spherical nature of Exo-pOEOMA species. Considering the average diameter of 140 nm for exosome from HF5 data (SI Appendix, Figs. S5 and S6), ∼2,500 polymer chains at 0.1 µM loading account for a density of 1 polymer chain per 25 nm2. Increasing the targeted surface loading by 10-fold to 1 µM, surface density increased significantly to an average of 1 polymer chain per 8 nm2, suggesting a dense surface coverage. We also found that the polymer chains do not fall off and are retained on the exosome surface after a freeze–thaw cycle.

Using different monomers allows engineering of EPHs with varying functional groups on the surface and their potential derivatization that can alter the exosome’s physical properties. Increasing induction of anti-polyethylene glycol (PEG) antibodies in human also points to a strong need for advancing biocompatible polymers beyond PEG-based polymers (49, 50). Thus, along with brush-like polyethylene oxide (PEO)-based pOEOMA, two other biocompatible polymers were explored—zwitterionic pCBMA and sulfoxide-based pMSEA—to prepare EPHs. Zwitterionic polymers are nonfouling in nature and offer higher chemical diversity for exosome-based materials (51). A recent report that a pMSEA polymer can reduce macrophage uptake of a protein polymer hybrid provides another example of a polymer enhancing the biochemical profile in a polymer biohybrid (31, 52). Grafting of cationic polymers such as pDMAEMA onto the exosome surface can also offer a wide variety of responsive hybrids and therapeutic materials. However, we found that it was challenging to prepare Exo-pDMAEMA hybrids by the grafting-to strategy due to competing electrostatic interactions. Thus, to enable cationic polymer-exosome hybrid species, we explored a “grafting-from” strategy.

The “grafting-from” strategy is a powerful method which not only improves polymer grafting efficiency from surfaces in general, but also provides access to functional block copolymers and other polymer architectures. Indeed, enzymatic degassing and blue light-mediated photoATRP provided fast routes to prepare EPHs with preserved structural integrity in 15 to 30 min. Use of low parts per million (ppm) amounts of Cu/TPMA catalyst circumvented any cytotoxicity in prepared EPHs. This synthetic strategy also provided the means to prepare EPHs with cationic pDMAEMA by chain extension of Exo-pOEOMA hybrids. While electrostatic interactions between cationic polymers and negatively charged membrane have been explored to prepare exosome hybrids recently, such surface encapsulation approaches tend to shadow the exosomal surface properties (53).

Surface polymer density and the accessibility of surface proteins were critical aspects in the design to preserve the bioactivity in EPHs. Shorter pOEOMA chains (Mn = 10,000 g/mol) were ineffective in modulating the exosome surface accessibility, despite high 5 µM surface loadings. Longer polymer chains (Mn = 20,000, 30,000) at 1 µM allowed binding of surface CD63 proteins to antibody-conjugated magnetic beads and also prevented the degradation of the DNA tethers upon nuclease treatment. These results highlight that surface polymer chains control the access of small enzymes to exosomal membrane as well as the binding ability of surface proteins. Further, QCM studies showed that surface polymers can also significantly reduce the accessibility of surface tethered targeting agents; however, the targeting ability can be recovered by increasing the concentration of the tethered targeted agent. While polymer loading is useful for modulating surface interactions, these results also point out that uncontrolled polymer conjugation can negatively affect exosome–cell interactions, which would be ill-suited for certain applications such as those that rely on targeting. In addition to having highly controlled polymerization techniques, we also showed that the polymers could also be readily removed. To demonstrate this, we used a nitrophenyl-based group in the tether to allow for the reversible cleavage of polymers in 2 min by UV light irradiation. While the photolysis of certain nitrophenyl compounds can lead to toxic by-products (54), other stimuli-responsive linkers, such as disulfide, can be explored in future for the purpose of reversibility.

Storage at −20 °C is typically preferred for exosomes as their surface proteins are prone to shedding and aggregation at higher temperatures (13, 38, 55). By incubating Exo-pOEOMA at 1 µM polymer loading at different temperatures, the structural integrity of exosomes was observed over time. While native exosomes showed a tendency to aggregate at 4 °C, we also observed broadening of exosome population size along with protein subpopulations. Unlike native exosomes, EPHs showed no difference in the structural profile over a period of 1 mo at −20 °C, 4 °C, and 37 °C. This significantly enhanced exosome stability can be attributed to the PEO-chains on the membrane that potentially prevent exosome–exosome interactions. While this gave confidence on the overall stability of EPHs, the behavior of native exosomes and surface proteins needs more sensitive methods to be studied. Radiolabeling with 125I was employed to evaluate the stability of exosomal surface membrane proteins upon trypsin protease treatment of EPHs. Both pOEOMA and pCBMA tethered exosomes showed no degradation of surface proteins; however, this protection from proteolysis was reversible upon photocleavable release of polymers. These results highlight the stability and shielding advantage of polymer chains, as well as the ability and effectiveness of reversing the surface polymer functionalization.

Cellular uptake studies of the EPHs confirmed that the cell uptake of exosomes could be modified by conjugation of polymers on the membrane. This change in cell uptake property was dependent on the length and the amount of polymer tethered on the surface of exosomes. Since ATRP allows for precise control over tethered polymer architecture, the precise polymer length and loading amount were optimized to preserve the native properties of exosome uptake. We have previously shown that macrophage-derived exosome uptake by HEK cells can be partially inhibited by β-methylcyclodextrin and heparin (20). Cell uptake of EPHs can also be inhibited by the same two inhibitor combinations, confirming that both native exosomes and EPHs have similar modes of cell internalization.

Depending on the cellular source, exosomes have unique intrinsic properties that make them good candidates for drug delivery (14). Several investigators have further tailored exosome properties depending on targeted applications. In order to test how polymer conjugation affects exosome native and engineered properties, EPHs were synthesized from MSC-derived exosomes, curcumin-loaded macrophage exosomes, and BMP2-loaded macrophage exosomes. MSC-derived exosomes retained their angiogenic potential and induced early tubes in HUVEC and LEC cells, even after polymer conjugation. Similarly, both BMP2-exosomes and curcumin-exosomes retained their enhanced cargo-based biological activities of inducing osteoblastic differentiation and down-regulating NF-κB, respectively. These experiments suggest that polymer functionalization does not affect the intrinsic bioactivity of native or engineered exosomes.

The physicochemical properties of exosomes, such as size and surface charge, that influence their pharmacokinetics and biodistribution can be modulated with polymer conjugation. The coating or encapsulation of nanoparticles with polymers is of particular interest for the controlled release of drugs, genes, and other bioactive agents (56). Several reports have shown that coating nanoparticles with polymers, such as PEG, can improve their blood circulation time by avoiding their phagocytosis by monocytes (57). Kooijmans et al. were able to improve the blood circulation of exosomes from 10 min to 60 min (58). However, this approach lacks control over the length and amount of conjugated polymer, which could be a hurdle for the eventual clinical translation. In our approach, which employs precise control over polymer composition, chain lengths, and loading, the EPHs generated have much longer blood circulation time compared to their native exosome counterparts. Native exosomes offer a potential drug delivery system but are rapidly eliminated from blood circulation, limiting their applications; our results indicate that EPHs are a feasible alternative for an improved pharmacokinetic profile with preserved bioactivity.

Conclusion

The use of ATRP to engineer exosomes with functional polymers provides an advanced platform for exosome-based delivery vehicles and functional biomaterials for therapeutic applications. EPHs can be generated using both grafting-to and grafting-from techniques, and characterization using HF5 highlighted efficient polymer surface loading. ATRP allowed for precise engineering of polymer length on the exosome membranes, which were stable across a range of temperatures tested. EPHs were more stable under different storage conditions relative to their native exosome counterparts. Polymer conjugation improved exosomes’ blood circulation half-life while retaining their innate or engineered biological activity. Taken together, these properties of EPHs overcome some major limitations associated with the application of exosomes as drug delivery systems.

Materials and Methods

Exosome Isolation and Characterization.

Exosomes from conditioned media were isolated by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) using previously described protocol (20). Briefly, conditioned media (minimum of 48 h in cell culture) were differentially centrifuged (2500g for 10 min at 4 °C and 10000g for 30 min at 4 °C), followed by ultrafiltration (0.22 μm filter; Millipore-Sigma, Billerica, MA) and then size-exclusion chromatography on an A50 cm column (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) packed with Sepharose 2B (Sigma- Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Protein concentrations of exosome fractions were determined using a BCA Protein Assay kit as recommended by the manufacturer (Pierce, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Further characterization of exosomes was done with DLS, tunable resistive pulse sensing, Western blotting, and transmission electron microscopy. See SI Appendix for detailed procedures.

DNA Synthesis.

All DNA sequences were either synthesized using MerMade4 DNA synthesizer (Bioautomation, Irving, TX) using the standard DNA phosphoramidites (Chemgenes, Wilmington, MA) or ordered from IDT (Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc., Iowa, USA). Commercially available phosphoramidites (Glen Research, Sterling, VA) were used to introduce modifications on the 3′-end and 5′-end during the DNA synthesis. DNA macroinitiator sequences (DNA′-iBBr) were synthesized by coupling α-bromoisobutyrate initiator phosphoramidite on the 5′-end as previously reported (24). See SI Appendix for more details.

DNABCP Synthesis.

For the preparation of DNA′-pOEOMA sequences, 50 μL of DNA′-iBBr (2 mM stock), 260 μL of OEOMA500 monomer, 650 μL of the catalyst stock solution (12 mM CuBr2, 72 mM TPMA), 3.8 mL of ultrapure water, and 250 μL of 1 M NaCl were combined in a 20 mL glass vial. The reaction was degassed by passing a stream of nitrogen gas for 20 min. A 365-nm UV light source (5 mW/cm2) was used to start the polymerization by PhotoATRP. The reaction was carried out for 30 min. The reaction was analyzed by aqueous gel permeation chromatography (GPC), and the resulting DNABCP was purified using Amicon Ultra Centrifugal Filters (30-kDa molecular weight cut-off [MWCO]; Millipore Sigma, St. Louis, MO) before further usage. Similarly, DNA′-pOEOMA sequences with different polymer lengths (10 kDa and 20 kDa) were synthesized by varying the reaction time. The resulting DNABCPs were analyzed and purified before usage. Additional DNABCPs with different monomers were prepared using similar conditions as described in SI Appendix.

Preparation of EPHs by “Grafting-To” Strategy.

For the annealing approach, 20 µg of isolated THP1 exosomes were gently vortexed (600 RPM, Vortex-Genie 2 Vortex Mixer; Scientific Industries) with different concentrations of cholesterol-DNA (Chol-DNA) (0.1 µM to 20 µM) for 5 min at room temperature in 100 µL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer (final exosome concentration = 0.2 µg/µL). The samples were then annealed with a respective concentration of complementary polymer strand (DNA′-pOEOMA30K) by sequential incubation at 37 °C, 0 °C, and room temperature for 15 min, 10 min, and 30 min, respectively. Samples were then washed with Amicon Ultra Centrifugal Filters (100- kDa MWCO; Millipore Sigma, St. Louis, MO), followed by reverse spin to get Exo-dsDNA-pOEOMA (Exo-pOEOMA). For the preannealing approach, the Chol-DNA and complementary DNA′-pOEOMA30K strands were annealed by sequential incubation at 65 °C, 0 °C, and room temperature for 15 min, 10 min, and 30 min, respectively. Then, 20 μg of isolated THP1 exosomes were then gently vortexed for 5 min at room temperature with different concentrations (from 0.1 μM to 20 μM) of the preannealed duplex polymer strand (Chol-dsDNA-pOEOMA30K). Samples were washed with 100 kDa MWCO filters to remove any excess polymer strand. Size and surface charge of the resulting species was measured using Zetasizer (Malvern Instruments Ltd., Malvern, UK).

Preparation of EPHs by “Grafting-From” Strategy.

The exosome macroinitiator was prepared using the preannealing approach. Sixty μg of exosomes were gently vortexed with preannealed Chol-dsDNA-iBBr tether, followed by washes with Amicon Ultra Centrifugal Filters (100 kDa MWCO) to prepare the exosome macroinitiator (Exo-iBBr; 20 µM dsDNA tether concentration) species. For the “grafting-from” reaction, 150 μL of 60 μg Exo-iBBr, 7.5 µL of OEOMA500, 20 μL of the catalyst stock solution (12 mM CuBr2, 72 mM TPMA), 5 μL of Glucose Oxidase stock (15 mg/mL), 20 μL of Sodium Pyruvate stock (2 M), and 15 μL of 10× PBS were mixed with 52.5 μL of H2O. The reaction mixture was then transferred to a thin glass culture tube. Then, 30 μL of glucose stock (1.5 M) was added, and the vial was sealed for the deoxygenation (incubation for 5 min). The reaction vial was irradiated with blue light (4.5 mW/cm2) for 30 min. The reaction solution was washed with 100 kDa MWCO filters to get purified Exo-pOEOMA species, followed by analysis by DLS. Chain extension experiment and cytotoxicity studies were performed as described in SI Appendix.

Detailed procedures for synthesis, characterization, microscopy, and analysis can be found in SI Appendix. All other data discussed in the paper are available in the main text and SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Theresa L. Whiteside (University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Hillman Cancer Center, Pittsburgh, PA) for providing HUVEC and SVEC4-10 cells and access to the qNano instrument. We thank Rachel Keeney (Mellon College of Science, Carnegie Mellon University [CMU], Pittsburgh, PA) for her assistance with the graphic design. We thank Liye Fu for assistance with oxygen-tolerant ATRP; and Dr. Grzegorz Szczepaniak for comments on the figures. U.L.M. acknowledges an Erasmus+ grant for financial support. S.T. and N.S. acknowledge Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Grant JP17H06351). P.G.C. acknowledges financial support in part provided by CMU-Biohybrid Organ Center Seed Funding. Financial support from NSF Grant DMR 1501324 is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2020241118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability.

All study data are included in the article and SI Appendix.

References

- 1.Yáñez-Mó M., et al. , Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J. Extracell. Vesicles 4, 27066 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maas S. L. N., Breakefield X. O., Weaver A. M., Extracellular vesicles: Unique intercellular delivery vehicles. Trends Cell Biol. 27, 172–188 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kourembanas S., Exosomes: Vehicles of intercellular signaling, biomarkers, and vectors of cell therapy. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 77, 13–27 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hong C.-S., et al. , Circulating exosomes carrying an immunosuppressive cargo interfere with cellular immunotherapy in acute myeloid leukemia. Sci. Rep. 7, 14684 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colombo M., Raposo G., Théry C., Biogenesis, secretion, and intercellular interactions of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 30, 255–289 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.EL Andaloussi S., Mäger I., Breakefield X. O., Wood M. J. A., Extracellular vesicles: Biology and emerging therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 12, 347–357 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnsen K. B., et al. , A comprehensive overview of exosomes as drug delivery vehicles - endogenous nanocarriers for targeted cancer therapy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1846, 75–87 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haney M. J., et al. , Exosomes as drug delivery vehicles for Parkinson’s disease therapy. J. Control. Release 207, 18–30 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.György B., Hung M. E., Breakefield X. O., Leonard J. N., Therapeutic applications of extracellular vesicles: Clinical promise and open questions. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 55, 439–464 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lener T., et al. , Applying extracellular vesicles based therapeutics in clinical trials - an ISEV position paper. J. Extracell. Vesicles 4, 30087 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alvarez-Erviti L., et al. , Delivery of siRNA to the mouse brain by systemic injection of targeted exosomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 341–345 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pegtel D. M., et al. , Functional delivery of viral miRNAs via exosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 6328–6333 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee M., Ban J.-J., Im W., Kim M., Influence of storage condition on exosome recovery. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 21, 299–304 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meng W., et al. , Prospects and challenges of extracellular vesicle-based drug delivery system: Considering cell source. Drug Deliv. 27, 585–598 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morishita M., Takahashi Y., Nishikawa M., Takakura Y., Pharmacokinetics of exosomes-an important factor for elucidating the biological roles of exosomes and for the development of exosome-based therapeutics. J. Pharm. Sci. 106, 2265–2269 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiklander O. P. B., et al. , Extracellular vesicle in vivo biodistribution is determined by cell source, route of administration and targeting. J. Extracell. Vesicles 4, 26316 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Armstrong J. P. K., Holme M. N., Stevens M. M., Re-engineering extracellular vesicles as smart nanoscale therapeutics. ACS Nano 11, 69–83 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luan X., et al. , Engineering exosomes as refined biological nanoplatforms for drug delivery. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 38, 754–763 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piffoux M., Silva A. K. A., Wilhelm C., Gazeau F., Tareste D., Modification of extracellular vesicles by fusion with liposomes for the design of personalized biogenic drug delivery systems. ACS Nano 12, 6830–6842 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yerneni S. S., et al. , Rapid on-demand extracellular vesicle augmentation with versatile oligonucleotide tethers. ACS Nano 13, 10555–10565 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matyjaszewski K., Xia J., Atom transfer radical polymerization. Chem. Rev. 101, 2921–2990 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baker S. L., et al. , Atom transfer radical polymerization for biorelated hybrid materials. Biomacromolecules 20, 4272–4298 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matyjaszewski K., Advanced materials by atom transfer radical polymerization. Adv. Mater. 30, e1706441 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pan X., et al. , Automated synthesis of well-defined polymers and biohybrids by atom transfer radical polymerization using a DNA synthesizer. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 56, 2740–2743 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang H., Lyden D., Asymmetric-flow field-flow fractionation technology for exomere and small extracellular vesicle separation and characterization. Nat. Protoc. 14, 1027–1053 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Engelke J., et al. , An in-depth analysis approach enabling precision single chain nanoparticle design. Polym. Chem., 10.1039/D0PY01045F (2020). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Engelke J., et al. , Critical assessment of the application of multidetection SEC and AF4 for the separation of single-chain nanoparticles. ACS Macro Lett., 10.1021/acsmacrolett.0c00519 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burchard W., “Solution properties of branched macromolecules” in Branched Polymers II, Roovers J., Ed. (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 1999), pp. 113–194. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burchard W., “Static and dynamic light scattering from branched polymers and biopolymers” in Light Scattering from Polymers (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 1983), pp. 1–124. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gumz H., et al. , Toward functional synthetic cells: In-depth study of nanoparticle and enzyme diffusion through a cross-linked polymersome membrane. Adv. Sci. (Weinh.) 6, 1801299 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li S., et al. , Biocompatible polymeric analogues of DMSO prepared by atom transfer radical polymerization. Biomacromolecules 18, 475–482 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yeow J., Chapman R., Gormley A. J., Boyer C., Up in the air: Oxygen tolerance in controlled/living radical polymerisation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 4357–4387 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Enciso A. E., Fu L., Russell A. J., Matyjaszewski K., A breathing atom-transfer radical polymerization: Fully oxygen-tolerant polymerization inspired by aerobic respiration of cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 57, 933–936 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fu L., et al. , Synthesis of polymer bioconjugates via photoinduced atom transfer radical polymerization under blue light irradiation. ACS Macro Lett. 7, 1248–1253 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bates P. J., Laber D. A., Miller D. M., Thomas S. D., Trent J. O., Discovery and development of the G-rich oligonucleotide AS1411 as a novel treatment for cancer. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 86, 151–164 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takahashi S., et al. , 70 S ribosomes bind to Shine-Dalgarno sequences without required dissociations. ChemBioChem 9, 870–873 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takahashi S., et al. , Recovery of the formation and function of oxidized G-quadruplexes by a pyrene-modified guanine tract. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 5774–5783 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jeyaram A., Jay S. M., Preservation and storage stability of extracellular vesicles for therapeutic applications. AAPS J. 20, 1 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ludwig N., Yerneni S. S., Razzo B. M., Whiteside T. L., Exosomes from HNSCC promote angiogenesis through reprogramming of endothelial cells. Mol. Cancer Res. 16, 1798–1808 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park J. Y., et al. , Gemcitabine-incorporated G-quadruplex aptamer for targeted drug delivery into pancreas cancer. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 12, 543–553 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ai J., Xu Y., Lou B., Li D., Wang E., Multifunctional AS1411-functionalized fluorescent gold nanoparticles for targeted cancer cell imaging and efficient photodynamic therapy. Talanta 118, 54–60 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liang X., Zhang L., Wang S., Han Q., Zhao R. C., Exosomes secreted by mesenchymal stem cells promote endothelial cell angiogenesis by transferring miR-125a. J. Cell Sci. 129, 2182–2189 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choi W., et al. , Biomolecular densely grafted brush polymers: Oligonucleotides, oligosaccharides and oligopeptides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 59, 19762–19772 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Siegwart D. J., Oh J. K., Matyjaszewski K., ATRP in the design of functional materials for biomedical applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 37, 18–37 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen C., Ng D. Y. W., Weil T., Polymer bioconjugates: Modern design concepts toward precision hybrid materials. Prog. Polym. Sci. 105, 101241 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Niu J., et al. , Engineering live cell surfaces with functional polymers via cytocompatible controlled radical polymerization. Nat. Chem. 9, 537–545 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Masuda T., Shimada N., Maruyama A., Liposome-surface-initiated ARGET ATRP: Surface softness generated by “grafting from” polymerization. Langmuir 35, 5581–5586 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim J. Y., et al. , Cytocompatible polymer grafting from individual living cells by atom-transfer radical polymerization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 55, 15306–15309 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Verhoef J. J. F., Carpenter J. F., Anchordoquy T. J., Schellekens H., Potential induction of anti-PEG antibodies and complement activation toward PEGylated therapeutics. Drug Discov. Today 19, 1945–1952 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pelegri-O’Day E. M., Lin E.-W., Maynard H. D., Therapeutic protein-polymer conjugates: Advancing beyond PEGylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 14323–14332 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mi L., Jiang S., Integrated antimicrobial and nonfouling zwitterionic polymers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 53, 1746–1754 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yu Y., et al. , Proteins conjugated with sulfoxide-containing polymers show reduced macrophage cellular uptake and improved pharmacokinetics. ACS Macro Lett. 9, 799–805 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sawada S. I., et al. , Nanogel hybrid assembly for exosome intracellular delivery: Effects on endocytosis and fusion by exosome surface polymer engineering. Biomater. Sci. 8, 619–630 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Klán P., et al. , Photoremovable protecting groups in chemistry and biology: Reaction mechanisms and efficacy. Chem. Rev. 113, 119–191 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cheng Y., Zeng Q., Han Q., Xia W., Effect of pH, temperature and freezing-thawing on quantity changes and cellular uptake of exosomes. Protein Cell 10, 295–299 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mogoşanu G. D., Grumezescu A. M., Bejenaru C., Bejenaru L. E., Polymeric protective agents for nanoparticles in drug delivery and targeting. Int. J. Pharm. 510, 419–429 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Suk J. S., Xu Q., Kim N., Hanes J., Ensign L. M., PEGylation as a strategy for improving nanoparticle-based drug and gene delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 99, 28–51 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kooijmans S. A. A., et al. , PEGylated and targeted extracellular vesicles display enhanced cell specificity and circulation time. J. Control. Release 224, 77–85 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and SI Appendix.