Abstract

Teratomas are the most common congenital tumors, occurring along the midline or paraxial sites, or uncommonly, the mediastinum. Teratomas are classified as mature, containing only differentiated tissues from the three germinal layers; and immature, which also present with neuroectodermal elements, ependymal rosettes, and immature mesenchyme. Herein, we describe a new case of fetal mediastinal immature teratoma detected at 21 weeks of gestational age (wga) + 1 day with thorough cytogenetic analysis. Ultrasound (US) showed a solid and cystic mass located in the anterior mediastinum, measuring 1.8 × 1.3 cm with no signs of hydrops. At 22 wga, US showed a mass of 2.4 cm in diameter and moderate pericardial effusions. Although the prenatal risks and available therapeutic strategies were explained to the parents, they opted for termination of pregnancy. Histology showed an immature teratoma, Norris grade 2. Karyotype on the fetus and tumor exhibited a chromosomal asset of 46,XX. The fetal outcome in the case of mediastinal teratoma relies on the development of hydrops due to mass compression of vessels and heart failure. Prenatal US diagnosis and close fetal monitoring are paramount in planning adequate treatment, such as in utero surgery, ex utero intrapartum therapy (EXIT) procedure, and surgical excision after birth.

Keywords: second trimester ultrasound, immature teratoma, karyotype

1. Introduction

Teratomas are the most common congenital tumours, representing 16.6% of all fetal neoplasms with an incidence of 1:20,000 to 1:40,000 livebirths [1,2,3]. They usually arise in a para-axial or midline location, including the brain, sacrum, and gonads. The sacroccyx is the main location (40%), and the mediastinum accounts for only 4% of cases [4,5].

Fetal mediastinal teratomas are rare and usually arise in the anterior mediastinum as a median or paramedian mass [6]. At prenatal ultrasound (US), they appear multilobulated with solid and cystic areas, sometimes with calcifications, and acoustic shadows [7,8]. The differential diagnosis includes bronchogenic cysts, congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation (CCAM) of the lung, diaphragmatic hernia, or bronchopulmonary sequestration [4,9]. Although located in the mediastinum, fetal intrapericardial teratomas are considered cardiac tumors, as their origin is typically from the right anterior border of the heart [10,11].

Fetal mediastinal teratomas are a type of Extragonadal Germ Cell Tumour (EGCT) and differentiate in tissues from the three germinal layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm). They are divided into mature and immature, the former being the majority. Immature teratomas are uncommon, representing only 1%. They are made up of neuroectodermal epithelium with neuroglial elements and ependymal rosettes; immature mesenchyme may also be present [12].

The thoracic location may cause compression of lungs, heart, and major vessels, resulting in pericardial and pleural effusions, pulmonary hypoplasia, and cardiac failure. The main clinical consequences are non-immune fetal hydrops (NIFH) and polyhydramnios, but severe fetal distress and even stillbirth may occur [7,9].

Second trimester US detection of mediastinal teratomas has been scarcely reported [2,7,8,13,14], including the immature type [2,7,13,14].

Herein, we present a new case of fetal mediastinal immature teratoma first observed at US in the second trimester, at 21 weeks of gestational age (wga) + 1 day, initially with no signs of hydrops. Immature teratoma was then confirmed at autopsy and histology. Karyotyping was carried out on both the fetus and the neoplasia. Both showed a normal female chromosomal asset of 46,XX. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first fetal case in which cytogenetic analysis on the tumor was performed.

2. Case Description

A 38 year-old primigravida underwent a routine US scan at 21 wga+ 1 day, which showed a suspicious anterior mediastinal mass of 1.8 × 1 cm. The mother was immediately referred to an expert sonographer (Professor G.P.). Previous scans (at 12 and 18 wga), pregnancy and mother’s health were otherwise unremarkable.

Detailed US examination at 22 wga revealed a solid rounded echogenic mass in the anterior mediastinum with a minimal cystic component measuring 2.4 cm in maximum diameter. The mass dislocated inferiorly the main great vessels (aorta and pulmonary artery), posteriorly the aortic arch, laterally the superior vena cava, and superiorly the innominate vein (Figure 1). The heart showed normal anatomy with regular systemic and pulmonary venous return, atrio-ventricular and ventricular-arterial connections. Cardiac function, heartbeats, and rhythm were normal. A moderate pericardial effusion was present, but the pleural cavities were free of fluid. No fetal hydrops was present. The thymus was not clearly assessed. No other anomalies were observed at US.

Figure 1.

Ultrasound image of the teratoma: transverse view of the fetal chest at 22 weeks; a complex mass with solid and liquid components was seen in the upper and anterior part of the thorax (arrow).

The parents were made aware of the most probable diagnosis due to the anterior thoracic location (fetal mediastinal teratoma) and were explained the potential risks during pregnancy such as NIFH and polyhydramnios. All the possible therapeutic strategies potentially performed both during pregnancy and at birth were also illustrated, such as amniotic fluid reduction, ex utero intrapartum therapy (EXIT) or neonatal surgery in an adequate hospital structure. Moreover, the favorable neonatal outcome after surgical removal of mediastinal masses was also explained. Nevertheless, the parents opted for legal termination of pregnancy at 22 wga + 2 days. During the procedure, amniotic fluid was collected for karyotyping, which showed a normal female 46,XX formula.

Autopsy showed a female fetus with no significant dysmorphic features. Fetal anthropometric parameters and organ weights were assessed according to Archie JG et al. [15].

Internal examination revealed a pinkish nodule of 2.5 × 1.5 × 0.8 cm located in the anterior mediastinum underneath the thymus and above the pericardium (Figure 2). The nodule was easily dissected both from the posterior thymic surface and the anterior pericardium. On dissection, the nodule was mainly made up of solid pinkish tissue with focal cystic areas (Figure 3). Pericardial effusion was moderate with 0.5 mL of serous fluid. The combined lung weight was 8.7 g. Although not indicative of hypoplasia, the weight was in the lower range of what is expected for age (12.0 ± 3.8 g) [15]. Grossly, no other anomalies were identified.

Figure 2.

Gross features of mediastinal teratoma (blue arrow) at autopsy: the tumor was located underneath the thymus (star) and above the heart.

Figure 3.

Dissected appearance of the teratoma: a pinkish solid, but soft nodule with cystic areas.

Microscopically, the nodule showed the typical features of a teratoma, composed of mature and immature tissue from the three embryonic germinal layers. Endodermal elements were predominant with ciliated respiratory epithelium, gastric mucosa, and glands in a lobular pattern (Figure 4). A miniature fetal liver (endoderm origin) with hematopoiesis (mesoderm) was focally identified. The mesodermal component was represented by choroid pigmented epithelium, renal structures, cartilage, abundant areas of immature mesenchyme, and smooth muscle. Neuroectoderm was abundant and characterized by immature neuroepithelium with ependymal rosettes (Figure 5). Although not validated for fetal teratomas, the application of Norris grading system would classify the neoplasia as immature grade 2 [16,17]. Cytogenetic analysis was carried out on the neoplasia, which showed 46,XX, a chromosomal asset identical to the somatic counterpart (Figure 6).

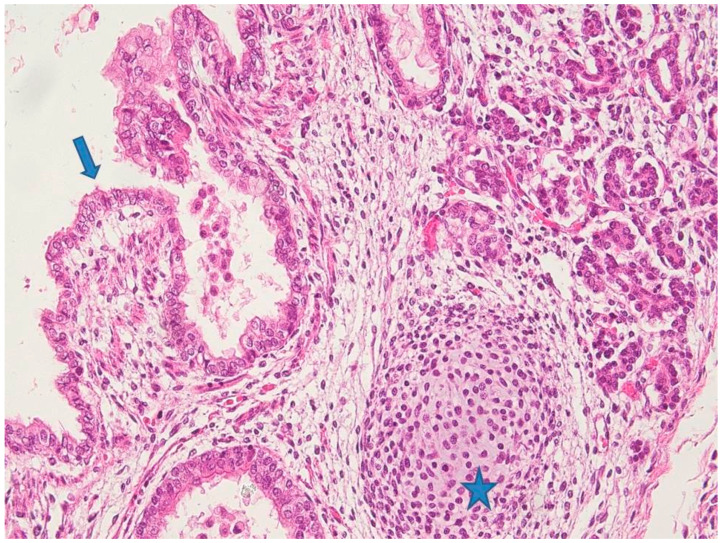

Figure 4.

Histology of mature components of the neoplasia: endodermal elements with respiratory cilitaed epithelium (blue arrow) and glands (top right of the picture). Cartilage (mesoderm) was also present (star). (Hematoxylin Eosin (HE) staining 10×).

Figure 5.

Immature elements of the tumor: neuroectodermal structures with ependymal rosettes (HE staining 20×).

Figure 6.

Tumor karyotype: female asset of 46,XX.

3. Discussion

Prenatal US diagnosis of mediastinal teratoma has been scarcely reported, especially in the second trimester, and is summarized in Table 1 [2,7,8,9,13,14,18,19,20,21,22,23,24].

Table 1.

Fetal cases currently reported with prenatal ultrasound (US) of mediastinal teratoma. Wga: weeks of gestational age; NIFH: Non Immune Fetal Hydrops; Y: yes; NOS: not otherwise specified. TOP: termination of pregnancy.

| Author and Year | Wga at US Diagnosis | Teratoma US Findings | NIFH | Teratoma Histological Diagnosis | Outcome | Surgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weinraub et al. [9] 1989 | 29 | Multilocular and cystic | Y: diffuse fetal edema, pleural effusions; pulmonary hypoplasia, placental hydrops and polyhydramnios | Mature | Fetal demise at 29 weeks | No |

| Dumbell et al. [20] 1990 | 35 | Multilocular and cystic | Y: skin edema, polyhydramnios | Mature | Induction of labour; vaginal delivery at 36 weeks, baby alive at 18-month- follow-up | Y: 2 days after birth |

| Froberg et al. [4] 1994 | 25 | Solid and cystic | Y: fetal anasarca | Immature | IUFD at 27 weeks: induction of labour, vaginal delivery | |

| Liang et al. [21] 1998 | 38 | Solid and cystic | No: polyhydramnios | Mature | Delivery at 39 weeks | Y: 7 days after birth |

| Schild et al. [22] 1998 | 27 | Solid | Y: skin edema, pleural effusions, ascites | Mature | C-section at 27 weeks + 5 days: failed resuscitation | |

| Wang et al. [18] 2000 | 36 | Multilocular cystic | No; polyhydramnios at 38 weeks | Immature | Induction of labor, vaginal delivery at 39 weeks; alive after 3 months after surgery | Y: 4 days after birth |

| Aksoy et al. [23] 2002 | 34 | Solid and cystic | Y: edema of head and neck, polyhydramnios, pulmonary hypoplasia | Immature | C-section at term; died at one day of life | Y: immediately after birth |

| Merchant et al. [7] 2005 Case 1 |

21 weeks + 4 days | Heterogeneous mass with calcifications | Y: diffuse edema, pleural effusions, ascites | Immature | C-section at 25 weeks for preterm labor; alive at 9-month-follow-up | Y: in utero at 23 weeks |

| Merchant et al. [7] 2005 Case 2 |

34 | Heterogeneous mass with calcifications | Y: chest wall, facial, and scalp edema, hepatomegaly, ascites, pleural effusions, and massive polyhydramnios | Immature | EXIT procedure, alive at 1 year follow-up | Y: during EXIT procedure |

| Takayasu et al. [8] 2010 | 23 | Cystic mass | Y: developed at 29 weeks | Mature | Vaginal delivery at 39 weeks; alive at 6-month-follow-up | Y: at 30 days of age |

| Giancotti et al. [24] 2011 | 29 | Heterogeneous appearance with calcifications | Y: pleural effusions, ascites, polyhydramnios | Teratoma NOS | C-section 32 weeks; alive at 8-month-follow-up | Y: 1 day after birth |

| Gaetani et al. [2] 2016 | 21 weeks + 4 days | Cystic | No | Immature | C-section at 33 weeks | |

| Gong et al. [19] 2016 | 27 | Heterogenous lobulated | Y: diffuse and polyhydramnios | Immature | TOP at 27 weeks | |

| Darouich et al. [13] 2020 | 23 | Solid and cystic | Y: diffuse skin edema, ascites, and pleural effusions | Immature | TOP at 24 weeks | |

| Srisupundit et al. [14] 2020 | 20 | Solid and cystic | Y: subcutaneous edema, moderate pleural effusion and ascites | Immature | TOP at 23 weeks | |

| Present case | 21 weeks + 1 day | Solid with focal cystic areas | No | Immature teratoma | TOP at 22 weeks |

In our case, a mediastinal mass was detected at US at 21 wga + 1 day, being the second fetal case reported both with an early diagnosis and without hydrops. Only one case, at 21 wga + 6 days has been described without hydrops [2]. Instead, the other fetus, diagnosed at 20 wga, showed NIFH [14].

Overall, in the literature data retrieved, NIFH was a frequent finding, ranging from mild signs (pleural or pericardial effusions) to more severe features (skin edema, pulmonary hypoplasia, ascites, polyhydramnios). Therefore, prenatal US diagnosis is fundamental in identifying the type of mediastinal mass, early signs of NIFH and further therapeutic planning.

In fact, at US, mediastinal teratoma is typically characterized by progressive mass growth, and CCAM or pulmonary sequestration remain unchanged or even decrease in size at consecutive scans [2,25,26]. In our case, the teratoma was rapidly growing in a short time. US scans at 12 and 18 weeks were normal, but at 21 + 1 wga, the mass measured 1.8 × 1.3 cm with no accompanying hydrops. At 22 weeks, the neoplasm reached 2.4 cm in maximum diameter and a mild to moderate pericardial effusion was detected with major vessels displacement. At autopsy, carried out at 22 + 2 wga, the dimensions recorded were 2.5 × 1.5 × 0.8 cm.

In our case, histopathological examination revealed an immature teratoma, Norris grade 2. The immature type seems the most common in the prenatal setting [2,4,7,13,14,18,19], including three cases diagnosed only at birth with normal prenatal US [27,28,29]. In other fetal presentations of mediastinal teratoma, diagnosed only at autopsy, tumor differentiation was not mentioned [30,31].

In three cases [31], teratoma was found at autopsy with other associated anomalies, but karyotype was not performed. However, in most fetuses or newborns, teratoma was an isolated finding with no other associated anomalies, and the somatic karyotype was normal [13,18,22] or even not investigated [2,4,7,8,9,14,19,20,21,23,24,27,28,29,30,31]. None had karyotyping carried out on the tumor. Nonetheless, mediastinal teratoma may occur in Klinefelter syndrome and isochromosome 12p is considered indicative of malignant potential [32,33]. In our case, teratoma was an isolated finding with no other associated anomalies. Cytogenetic analysis displayed a normal karyotype of 46,XX in both the fetus and the neoplasia. These findings correlate with the current literature, as in the pediatric population, the tumor karyotype is normal independently of its grade of maturation and differentiation [34,35]. Moreover, as reported in children, mediastinal teratomas are reported more frequently in females [5,36,37]. To the best of our knowledge, our case was the first fetus in which a thorough cytogenetic analysis was performed.

In general, in newborns, after surgical removal, mature and immature mediastinal teratomas have a favorable prognosis with low mortality and good health at different follow up durations (Table 1) [38,39,40,41,42,43]. Although infrequent, immature teratomas may recur and a close clinical follow-up including tumor markers is necessary [44,45]. On the other hand, in the prenatal setting, fetal outcome of mediastinal teratomas relies on the development of NIFH, due to tumor size and progressive compression of venous return. Prenatal treatments include fetal aspiration of the cystic mass, amnioreduction in the case of polyhydramnios, and, where available, fetal surgery to avoid NIFH or its worsening. Timing and decision of postnatal excision depends on fetal conditions and mass size, and it should be organized in adequate hospital structures. The optimal approach is the ex utero intrapartum therapy (EXIT)-to-resection procedure, which allows immediate fetal thoracotomy and surgical removal of the mass, preventing acute respiratory distress [2].

In general, although the literature data is scarce, the prognosis of fetal mediastinal teratomas has been reported as favorable overall, if promptly managed during pregnancy, and it is closely connected to NIFH occurrence. In the case we presented, fetal outcome was uncertain as the mass was rapidly growing and worsening of NIFH was highly likely or even inevitable. Moreover, as the immature type is considered potentially malignant with a high risk of recurrence, this histological finding was another adverse prognostic factor. No data is available regarding the karyotype in fetal teratoma and its predictive value. Therefore, cytogenetic analyses should be helpful in exploring this unknown prognostic factor in the fetal/perinatal setting.

In conclusion, in our specific case, although it is only speculative, fetal prognosis would have probably been negative, as tumor growth was rapidly progressive and NIFH evolution may have resulted in fetal death.

Author Contributions

Carried out the pathological diagnosis and wrote the manuscript—original draft preparation, review and editing, M.P.B.; Made ultrasound diagnosis and clinically managed the patient, G.C. and G.P.; Provided the histological pictures and searched for the bibliograhy, A.P.; Carried out the cytogenetic diagnosis, V.B.; Reviewed the histological slides, N.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Our investigations were carried out following the rules of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975, revised in 2013. According to Italian legislation, Ethical Approval for a single case is not required, as long as the data is kept anonymous and the investigations performed do not imply genetic results.

Informed Consent Statement

The current Italian legislation neither requires the family’s consent or ethical approval for a single case, as long as the data are strictly kept anonymous. As summoning the mother was not possible because it would interfere with the grieving process, patient’s consent was completely waived, according to the Italian Authority of Privacy and Data Protection (“Garante della Privacy”: GDPR nr 679/2016; 9/2016 and recent law addition number 424/19 July 2018; http://www.garanteprivacy.it).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study is available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kamil D., Tepelmann J., Berg C., Heep A., Axt-Fliedner R., Gembruch U., Geipel A. Spectrum and outcome of prenatally diagnosed fetal tumors. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2008;31:296–302. doi: 10.1002/uog.5260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaetani M., Damiani G.R., Pellegrino A., Rizzo N., Martelli F., Aly Y., Lima M., Farina A. Diagnosis and management of a rare case of fetal mediastinal teratoma without non-immunological hydrops. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2016;36:390–392. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2015.1085845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grosfeld J.L., Billmire D.F. Teratomas in infancy and childhood. Curr. Probl. Cancer. 1985;9:1–53. doi: 10.1016/S0147-0272(85)80031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Froberg M.K., Brown R.E., Maylock J., Poling E. In utero development of a mediastinal teratoma: A second-trimester event. Prenat. Diagn. 1994;14:884–887. doi: 10.1002/pd.1970140920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tapper D., Lack E.E. Teratomas in infancy and childhood. A 54-year experience at the Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Ann. Surg. 1983;198:398–410. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198309000-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Avni F.E., Massez A., Cassart M. Tumours of the fetal body: A review. Pediatr. Radiol. 2009;39:1147–1157. doi: 10.1007/s00247-009-1160-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merchant A.M., Hedrick H.L., Johnson M.P., Wilson R.D., Crombleholme T.M., Howell L.J., Adzick N.S., Flake A.W. Management of fetal mediastinal teratoma. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2005;40:228–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takayasu H., Kitano Y., Kuroda T., Morikawa N., Tanaka H., Fujino A., Muto M., Nosaka S., Tsutsumi S., Hayashi S., et al. Successful management of a large fetal mediastinal teratoma complicated by hydrops fetalis. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2010;45:e21–e24. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinraub Z., Gembruch U., Födisch H.J., Hansmann M. Intrauterine mediastinal teratoma associated with non-immune hydrops fetalis. Prenat. Diagn. 1989;9:369–372. doi: 10.1002/pd.1970090512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuan S.M. Fetal Intrapericardial Teratomas: An Update. Z. Geburtshilfe Neonatol. 2020;224:187–193. doi: 10.1055/a-1114-6572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tollens M., Grab D., Lang D., Hess J., Oberhoffer R. Pericardial teratoma: Prenatal diagnosis and course. Fetal. Diagn. Ther. 2003;18:432–436. doi: 10.1159/000073138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carter D., Bibro M.C., Touloukian R.J. Benign clinical behavior of immature mediastinal teratoma in infancy and childhood: Report of two cases and review of the literature. Cancer. 1982;49:398–402. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820115)49:2<398::AID-CNCR2820490231>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Darouich S., Bellamine H. Fetal mediastinal teratoma: Misinterpretation as congenital cystic lesions of the lung on prenatal ultrasound. J. Clin. Ultrasound. 2020;48:287–290. doi: 10.1002/jcu.22808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Srisupundit K., Sukpan K., Tongsong T., Traisrisilp K. Prenatal sonographic features of fetal mediastinal teratoma. J. Clin. Ultrasound. 2020;48:419–422. doi: 10.1002/jcu.22876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Archie J.G., Collins J.S., Lebel R.R. Quantitative standards for fetal and neonatal autopsy. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2006;126:256–265. doi: 10.1309/FK9D5WBA1UEPT5BB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norris H.J., Zirkin H.J., Benson W.L. Immature (malignant) teratoma of the ovary: A clinical and pathologic study of 58 cases. Cancer. 1976;37:2359–2372. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197605)37:5<2359::AID-CNCR2820370528>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O′Connor D.M., Norris H.J. The influence of grade on the outcome of stage I ovarian immature (malignant) teratomas and the reproducibility of grading. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 1994;13:283–289. doi: 10.1097/00004347-199410000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang R.M., Shih J.C., Ko T.M. Prenatal sonographic depiction of fetal mediastinal immature teratoma. J. Ultrasound Med. 2000;19:289–292. doi: 10.7863/jum.2000.19.4.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gong W., Liang L., Zheng D.G., Zhong R.S., Zhu Y.X., Wen Y.J. A case report of fetal malignant immature mediastinal teratoma. Clin. Exp. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017;44:496–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dumbell H.R., Coleman A.C., Pudifin J.M., Winship W.S. Prenatal ultrasonographic diagnosis and successful management of mediastinal teratoma. A case report. S. Afr. Med. J. 1990;78:481–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liang R.I., Wang P., Chang F.M., Chang C.H., Yu C.H. Prenatal sonographic characteristics and Doppler blood flow study in a case of a large fetal mediastinal teratoma. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 1998;11:214–218. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1998.11030214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schild R.L., Plath H., Hofstaetter C., Hansmann M. Prenatal diagnosis of a fetal mediastinal teratoma. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 1998;12:369–370. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1998.12050369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aksoy F., Sen C., Danişment N. Congenital mediastinal immature teratoma: A case report with autopsy findings. Turk J. Pediatr. 2002;44:76–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giancotti A., La Torre R., Bevilacqua E., D’Ambrosio V., Pasquali G., Panici P.B. Mediastinal masses: A case of fetal teratoma and literature review. Clin. Exp. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012;39:384–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Isaacs H., Jr. Perinatal (fetal and neonatal) germ cell tumors. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2004;39:1003–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson R.D., Hedrick H.L., Liechty K.W., Flake A.W., Johnson M.P., Bebbington M., Adzick N.S. Cystic adenomatoid malformation of the lung: Review of genetics, prenatal diagnosis, and in utero treatment. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2006;140:151–155. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allman A.W., Buss P.W., Spicer R.D., Wake A. Mediastinal teratoma presenting as apparent fresh stillbirth. Arch. Dis. Child Fetal. Neonatal. Ed. 2001;84:F65–F66. doi: 10.1136/fn.84.1.F65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wesolowski A., Piazza A. A case of mediastinal teratoma as a cause of nonimmune hydrops fetalis, and literature review. Am. J. Perinatol. 2008;25:507–512. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1083836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simoncic M., Kopriva S., Zupancic Z., Jerse M., Babnik J., Srpcic M., Grosek S. Mediastinal teratoma with hydrops fetalis in a newborn and development of chronic respiratory insufficiency. Radiol. Oncol. 2014;48:397–402. doi: 10.2478/raon-2013-0080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuller J.A., Laifer S.A., Martin J.G., MacPherson T.A., Mitre B., Hill L.M. Unusual presentations of fetal teratoma. J. Perinatol. 1991;11:294–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Noreen S., Heller D.S., Faye-Petersen O. Mediastinal teratoma as a rare cause of hydrops fetalis and death: Report of 3 cases. J. Reprod. Med. 2008;53:708–710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kang J., Mashaal H., Anjum F. StatPearls [Internet] StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island, FL, USA: 2021. Mediastinal Germ Cell Tumors. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee T., Seo Y., Han J., Kwon G.Y. Analysis of chromosome 12p over-representation and clinicopathological features in mediastinal teratomas. Pathology. 2019;51:62–66. doi: 10.1016/j.pathol.2018.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schneider D.T., Schuster A.E., Fritsch M.K., Calaminus G., Göbel U., Harms D., Lauer S., Olson T., Perlman E.J. Genetic analysis of mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors in children and adolescents. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2002;34:115–125. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kao C.S., Bangs C.D., Aldrete G., Cherry A.M., Ulbright T.M. A Clinicopathologic and Molecular Analysis of 34 Mediastinal Germ Cell Tumors Suggesting Different Modes of Teratoma Development. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2018;42:1662–1673. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yalçın B., Demir H.A., Tanyel F.C., Akçören Z., Varan A., Akyüz C., Kutluk T., Büyükpamukçu M. Mediastinal germ cell tumors in childhood. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2012;29:633–642. doi: 10.3109/08880018.2012.713084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schneider D.T., Calaminus G., Reinhard H., Gutjahr P., Kremens B., Harms D., Göbel U. Primary mediastinal germ cell tumors in children and adolescents: Results of the German cooperative protocols MAKEI 83/86, 89, and 96. J. Clin. Oncol. 2000;18:832. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.4.832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barksdale E.M., Jr., Obokhare I. Teratomas in infants and children. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2009;21:344–349. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32832b41ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stajevic M., Dizdarevic I., Krunic I., Topic V. Mediastinal teratoma presenting with respiratory distress and cardiogenic shock in a neonate. Interact Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2020;30:788–789. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivz328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bekker A., Goussard P., Gie R., Andronikou S. Congenital anterior mediastinal teratoma causing severe airway compression in a neonate. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;26:bcr2013201205. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-201205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuroiwa M., Suzuki N., Takahashi A., Ikeda H., Hatakeyama S.I., Matsuyama S., Tsuchida Y. Life-threatening mediastinal teratoma in a neonate. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2001;17:235–238. doi: 10.1007/s003830000466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lakhoo K., Boyle M., Drake D.P. Mediastinal teratomas: Review of 15 pediatric cases. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1993;28:1161–1164. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(93)90155-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mogilner J.G., Fonseca J., Davies M.R. Life-threatening respiratory distress caused by a mediastinal teratoma in a newborn. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1992;27:1519–1520. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(92)90490-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kreller-Laugwitz G., Kobel H.F., Oppermann H.C. Mediastinalteratom bei einem Neugeborenen [Mediastinal teratoma in a newborn infant] Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 1988;136:270–272. (In German) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Upadhyaya M., Jaffar Sajwany M., Tomas-Smigura E. Recurrent immature mediastinal teratoma with life-threatening respiratory distress in a neonate. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2003;13:403–406. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-44731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study is available on request from the corresponding author.