Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has presented families around the world with extraordinary challenges related to physical and mental health, economic security, social support, and education. The current study capitalizes on a longitudinal, cross-national study of parenting, adolescent development, and young adult competence to document the association between personal disruption during the pandemic and reported changes in internalizing and externalizing behavior in young adults and their mothers since the pandemic began. It further investigates whether family functioning during adolescence three years earlier moderates this association. Data from 484 families in five countries (Italy, the Philippines, Sweden, Thailand, and the United States) reveal that higher levels of reported disruption during the pandemic are related to reported increases in internalizing and externalizing behaviors after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic for young adults (Mage = 20) and their mothers in all five countries, with the exception of one association in Thailand. Associations between disruption during the pandemic and young adults’ and their mothers’ reported increases in internalizing and externalizing behaviors were attenuated by higher levels of youth disclosure, more supportive parenting, and lower levels of destructive adolescent-parent conflict prior to the pandemic. This work has implications for fostering parent-child relationships characterized by warmth, acceptance, trust, open communication, and constructive conflict resolution at all times given their protective effects for family resilience during times of crisis.

Keywords: COVID-19, parenting, adolescence, internalizing, externalizing, international

Global crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic disrupt families in a multitude of ways (Bornstein, 2020). To stem the spread of COVID-19, governments established public health regulations involving physical distancing, if not quarantine, which have disrupted family routines, work, education, and peer interactions. These regulations have resulted in parents providing 24/7 care to children alongside increased stress, illness, financial insecurity, and less access to social support (Cluver et al., 2020). Further, the impact on mental health will likely continue far beyond the development of a vaccine or widespread effective treatment, with possible cascading effects. Family systems perspectives strongly imply that the COVID-19 pandemic influences family adjustment and well-being because of the interwoven and mutually reinforcing associations between social disruptions and economic hardship, caregiver distress and coping, and children’s development (Prime et al., 2020). Incorporating life course and historical perspectives, this framework also suggests that preexisting vulnerabilities in families will increase the risk of negative adaptation brought about by the disruption of the pandemic, whereas stronger family relationships can be regarded as a promotive (enhancing positive outcomes) and protective (buffering against negative outcomes) factor that is critical to the adaptation of caregivers and children in crises (Masten & Narayan, 2012; Prime et al., 2020).

Young adults face various normative but stressful transitions in higher education, professional development, and forming more stable intimate relationships (Arnett, 2016), which are complicated by the economic, education, and social disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic. Shanahan and her colleagues (2020) report from a recent longitudinal study that pre-pandemic stressors predicted and exacerbated emotional distress during the pandemic. Apart from highlighting the importance of examining young adult adjustment, Shanahan et al. (2020) underscore the importance of longitudinal studies to examine how pre-pandemic variables influence adaptation during the pandemic. Another longitudinal, population-based study in the United Kingdom showed that a group including young adults (aged 18-34) showed the largest increase in mental health problems compared to other adult groups when pre-pandemic mental health was compared to assessments made in April, May, and June of 2020, after the initial lockdown in the U. K. (Daly, Sutin, & Robinson, 2020). Our sample of 20-year-olds is thus especially important to study because compared to older adults, they may be more vulnerable to the negative impacts of the pandemic. Similarly, other work across a 20-week period from March to August of 2020 in England showed that symptoms of depression and anxiety among adults declined and plateaued over time, but remained at clinically high levels, especially for younger adults and women living with children in the house (Fancourt, Steptoe, & Bu, 2021).

The present study first examines young adults’ and their mothers’ reports of personal disruption experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic in relation to reported increases in their internalizing and externalizing behaviors. We examine these associations in five countries - Italy, the Philippines, Sweden, Thailand, and the United States - to be able to assess whether the associations vary in contexts that differed in their responses to the pandemic. Second, we use mother, father, and adolescent reports of parent-child relationship quality to examine family factors assessed earlier during adolescence as moderators of associations between the level of disruption attributed to the pandemic and young adults’ and their mothers’ self-reported increases in internalizing and externalizing behaviors during the pandemic as compared to before the COVID-19 outbreak.

Parent-child relationships change during late adolescence and early adulthood and require “realignments” in the face of changing needs, roles, and expectations (Bornstein & Putnick, 2020). However, many key theories of development (e.g., attachment theory) are predicated on the idea that relationship quality in earlier developmental stages has enduring qualities and predicts children’s, adolescents’, and young adults’ adjustment in later developmental stages (e.g., Jones et al., 2018). For example, in a U.S. sample, adolescents who distrusted their mothers and fathers and felt more alienation from their parents in Grade 6 experienced more anxiety and depression in Grade 12 than those who had more positive relationships with their parents years earlier (Ebbert et al., 2019). Fewer studies have examined how parent-child relationship quality predicts parents’ subsequent adjustment, but transactional processes in which adolescents influence their parents as parents influence adolescents are an important part of family systems theory and supported by empirical findings (e.g., Withers et al., 2016). The pandemic also created a situation in which many parents spent time with their adult and other children more than might typically occur, which makes examining parents’ adjustment especially compelling. For example, many young adults’ education and work experiences moved online during the pandemic, resulting in parents and young adults spending more time living together. Additional time together might provide opportunities to jointly support one another but could also result in increased levels of conflict and household stress. There is also some evidence that the pandemic was associated with non-normative large decreases in the time adolescents spent with friends but increased parental control, particularly among adherence to governmental regulations to stem the spread of the virus, parental involvement in their young adults’ participation in educational experiences online, and sleep timing (Keijsers & Bülow, 2020). Decreased peer time and increased parental control during the pandemic operates in the opposite way of typical adolescent and young adult development, which is usually characterized by greater autonomy from parents and increased influence from peers (Steinberg & Silk, 2002). Parent-child relationship quality as evidenced earlier in life may moderate the link between experiencing stressful life events and changes in adjustment because supportive parent-child relationships may serve as a resource promoting resilience for both young people and their parents (Tolliver-Lynn et al., 2021). Thus, parent-adolescent relationship quality prior to the COVID pandemic may be expected to predict changes in adjustment during the pandemic for both parents and young adult children as well as to moderate links between disruption during the pandemic and changes in adjustment. Between May and August of 2020 in the United States, during which strict lockdown was enacted and gradually began to lift, adolescents who demonstrated poor emotion-regulation before the pandemic were also at greater risk of showing increases in depression, anxiety, oppositional-defiant behavior and other maladaptive behavior (Breaux et al., 2021). Breaux et al.’s study of 15-17 year olds, although a few years younger than the young adults in the current study, suggests that pre-existing problems with emotion regulation – which may play a role in negative patterns of parent-adolescent conflict – may also be associated with later adjustment problems.

We focus on potential moderating variables that are especially critical in adolescence and young adulthood and have been shown in cross-sectional and longitudinal studies to be associated with systemic family functioning: youth disclosure, supportive parent behaviors, and parent-child destructive conflict. We discuss these specific variables in the succeeding sections.

Youth Disclosure

Parent-child communication changes across a child’s development. In adolescence, children begin to manage the information accessible to their parents by utilizing strategies ranging from disclosure to concealment, in order to enhance their privacy and sense of autonomy, and sidestep parental disapproval and conflict (Laird et al., 2013). Given that adolescents increasingly engage in behaviors outside of parental awareness, youth disclosure is a critical way parents gain knowledge about their children’s whereabouts, activities, and peer relationships (Frijns et al., 2010; Lionetti et al., 2019). At a time when disclosure to parents normatively decreases (Laird et al., 2013), levels of adolescent disclosure are important markers of the quality of parent-child relationships. Longitudinal studies have shown that maternal relationships characterized by support, companionship, trust, and acceptance were reciprocally associated with more disclosure across time among mid- to late adolescents (Rote et al., 2020). Closeness to parents also enhances disclosure among Chinese-American and Mexican-American youth, whose valuing of emotional restraint and parental authority may otherwise inhibit disclosure (Yau et al., 2009). Low or decreasing disclosure is associated with greater concealment or secrecy over time, which, in turn, is associated with higher levels of antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms (Laird et al., 2013). In general, youth disclosure may allow parents to provide more support in times of difficulty or stress, as well as provide the benefits of confiding personal experiences to others, thereby reducing adolescents’ vulnerability to depressive symptoms (Frijns et al., 2010; Hamza & Willoughby, 2011; Smetana et al., 2009). Adolescents’ disclosure may also enhance parents’ well-being by helping parents feel close to their adolescents and alleviating worries they may otherwise have about their adolescents’ lives.

Supportive Parenting

Healthy parent-child relationships are defined by behaviors that demonstrate parental support, warmth, and quality of time spent together. The research literature has firmly established the positive function of warm and supportive parenting for overall child adjustment and well-being, through to adolescence and young adulthood (Khaleque & Ali, 2017). Supportive parent-child relationships are even more critical to children’s and parents’ adjustment and resiliency following traumatic experiences and major community-wide life events like natural disasters. Following a major hurricane, adolescents who reported supportive parenting and overall higher parent-child relationship quality also reported lower levels of internalizing symptoms during the disaster recovery period (Felix et al., 2013). When adolescents reported that parents were available to spend time with them in the days and weeks following the hurricane, adolescents were at lower risk for internalizing problems in the recovery. Similarly, in the immediate aftermath of a major tropical cyclone in Australia, parents who rated their family as more dysfunctional – including negative communication, ineffective problem-solving, and low affective responsiveness – were also more likely to rate their children as having higher levels of internalizing behavior, even when the level of disruption due to the disaster was not predictive of internalizing behavior (McDermott & Cobham, 2012). Supportive parenting was also critical to the resilience of Norwegian children living in southeast Asia during the 2004 tsunami (Hafstad et al., 2012). Making time to spend with their children and being attuned to their behaviors and even simple sharing of everyday events was reported by parents to be successful in preventing more serious distressing emotional experiences in their children. However, these studies have generally examined supportive parenting concurrently with disruptive life events and children’s adjustment. Longitudinal studies are needed to understand how supportive parenting earlier in adolescence may contribute to family members’ later resilience in the face of disruption such as during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Destructive Conflict

Parent-adolescent conflict is generally accepted to be a normative part of development as parent and child roles reorganize from being more parent-directed to jointly directed by adolescents and parents. Conflict during adolescence is not necessarily a predictor of long-term adjustment difficulties or permanent impairment of the parent-child relationship (Laursen & Collins, 2009) and is generally low-intensity and concerned with daily, mundane issues (Smetana & Rote, 2019). The nature of conflict resolution, rather than the frequency of conflict, may be more important for the prevention of maladaptive behavior during adolescence. In particular, destructive versus constructive conflict resolution may signal the difference between risk and resilience following later traumatic events. In a study of over 1300 Dutch adolescents, how parent-adolescent conflicts were resolved moderated the relation between frequency of conflict and adolescent adjustment. Destructive conflict resolution, which included high levels of conflict engagement and withdrawal, was related to higher levels of both internalizing and externalizing behavior (Branje et al., 2009). Similarly, Tucker et al. (2003) found that constructive resolution to conflict, rather than leaving disagreements unresolved, attenuated the link between conflict and depression for mother-daughter dyads. Those conflicts that lack resolution and effective communication between parent and child are also linked to lower quality intimate partner relationships in the child’s adult life.

During crisis periods that affect entire families and communities, parent-adolescent conflict may play a unique role in the development of maladaptive responses to stressors. Following a major flood and its aftermath, adolescent perceptions of higher levels of family conflict made a unique contribution to post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) two years later, over and above the level of disruption caused by the flood (Bokszczanin, 2008). Research with families following Hurricane Katrina confirmed this prior research, in that parent-child conflict was the only parenting variable uniquely predictive of PTSS two years following the hurricane, even when controlling for PTSS symptoms one year following the hurricane (Gil-Rivas & Kilmer, 2013).

Present Study

Taken together, the literature on parent-child relationship quality supports the hypothesis that during the COVID-19 pandemic, links between disruption attributed to the pandemic and changes in adjustment of young adults and their mothers may be moderated by a history of adaptive parent-adolescent relationships characterized by high youth disclosure, supportive parenting, and low levels of destructive parent-adolescent conflict. To examine these relations in a diverse group of countries that have had varied government responses to the pandemic, we capitalize on data collected from families three years prior to the pandemic and from the same families in the approximately five months following the onset of COVID-19, beginning in March of 2020, in five countries: Italy, the Philippines, Sweden, Thailand, and the United States. For each site, we determined the pandemic onset date as the date each country enacted widespread school/business closures. Across the five sites, these dates ranged from March 4, 2020 (Italy) to March 23, 2020 (Thailand).

These five countries have experienced different infection and death rates and have employed different national response strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Italy was the first country outside of China to experience rapid spread of COVID-19 resulting in 588.49 deaths per one million residents during the study period (Best, 2020). In response, Italy imposed swift and stringent containment procedures, including school closures, mandated universal mask-wearing, and a stay-at-home order that helped slow the spread of COVID-19 within three weeks (McCann et al., 2020), although the situation worsened and improved in waves in the months that followed. As of this writing (March 2021) the Philippines has the highest number of COVID-19 cases in Southeast Asia, with 37.37 deaths per one million residents during the study period (Best, 2020). A strict and long-running lockdown was imposed to slow the spread of COVID-19, and currently, Filipinos must wear masks, shields, and maintain a distance of one meter from others whenever in public. All schools and universities have closed, and classes moved online, and children below age 18 are prohibited from going outside their residence (Lema, 2020). By contrast, Sweden responded to the virus by closing secondary schools and universities, but not primary schools. To date, there has been no widespread national mask mandate, but residents are encouraged to refrain from contact and large groups. Businesses have largely remained open (Goodman, 2020). During the study period, Sweden suffered 573.3 deaths per one million residents (Best, 2020). In Thailand, schools and businesses were ordered to close, and borders were closed to non-nationals (Beech, 2020). Thailand sustained 101 days without a locally transmitted case of COVID-19 (Olarn & Gan, 2020). During the study period, Thailand suffered 0.84 deaths per one million residents (Best, 2020). The response in the United States (U.S.) has been varied. With little coordinated national guidance in the initial months of the pandemic, regulating public health fell to state and local governments. The death rate in the United States during the study period was 578 deaths per million residents (Best, 2020). In North Carolina, where the majority of the study participants in our US sample reside, K-12 schools and universities were closed in March 2020, and indoor group gatherings over 10 and outdoor group gatherings over 25 were prohibited until September 2020 (Cooper, 2020). Non-essential businesses, including bars, movie theaters, and amusement parks, remain closed as of this writing under a state Executive Order (Cooper, 2020). Data visualizations to help understand the scope of the pandemic and stringency of containment measures implemented by governments internationally over time are available through the University of Oxford Coronavirus Government Response Tracker (https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/research-projects/coronavirus-government-response-tracker).ponse Tracker (https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/research-projects/coronavirus-government-response-tracker).

This study examines mother and young adult reports of disruptions and adjustment during the COVID-19 pandemic and how prior parent-child relationship qualities assessed during adolescence moderate the relation between personal disruption during the pandemic and adjustment outcomes for young adults and their mothers. We first examined individual perceptions of personal disruption during the COVID-19 pandemic as predictors of concurrently reported increases in internalizing and externalizing behavior during the pandemic (Time 2, young adult age 20). We hypothesized that high levels of COVID-19 disruption will predict maladaptive changes in adjustment for young adults and their mothers. Next, we tested whether youth disclosure, supportive parenting, and parent-child destructive conflict during adolescence (Time 1, young adult age 17) moderated the association between COVID-19 disruption and adjustment at Time 2 independently for young adults and mothers. Consistent with prior literature on the moderating role of parenting behavior during stressful and traumatic community-wide events, we predicted that across countries the relation between the level of disruption experienced by each family member during the pandemic and their own reports of maladaptive changes during the pandemic will be moderated by characteristics of the parent-child relationship during the target child’s adolescence, such that higher levels of youth disclosure and supportive parenting, as well as lower levels of destructive conflict will buffer the association between COVID-19 disruption and mothers’ and young adults’ adjustment.

Method

Participants

Participants were drawn from a larger, nine-country longitudinal study of parenting and child development. Five countries that were able to collect data shortly after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic were included in the present study: Naples and Rome, Italy, n = 125; Manila, Philippines, n = 60; Trollhättan/Vänersborg, Sweden, n = 66; Chiang Mai, Thailand, n = 73; and Durham, North Carolina, USA, n = 142. When families were initially recruited for the overall study, children were 8 years old, on average, and came from a diverse range of socioeconomic backgrounds, approximately representative of the income ranges in each site. Letters were sent home with families through schools in each site asking parents to complete a form if they were interested in learning more about the study. Parents were then contacted by phone or in person to follow up. Each site adhered to local research with human subjects regulations; the protocol was approved by the Duke University IRB (protocol number 2017-1191, Parent Behavior and Child Adjustment Across Cultures), as well as by ethics review boards at the other cooperating universities.

Data for the present study were drawn when the youth were approximately 17 and 20 years old, corresponding to Times 1 and 2 of the present study. At Time 1 (youth Mage = 16.85, SD = 0.97; 51% of youth male; mother Mage = 46.48, SD = 6.38; maximum years of parent education M = 14.16, SD = 4.17), 78% of the original sample recruited initially at age 8 continued to provide data at age 17. Compared to the initial sample, families who provided data at child age 17 did not differ on parental education, t(881) = −1.88, p = .06, or child gender, χ2 (1, N = 893) = 1.43, p = .23. COVID data at age 20 were collected using a truncated data collection period to quickly complete the analyses and help mental health professionals respond more effectively to the devastation caused by the pandemic. As a result, only 52% of the original sample of families provided data; this figure does not represent attrition from the ongoing longitudinal study but merely the participation rate during the compressed timeframe for COVID data collection. Compared to the initial sample, families who provide COVID-related data at child age 20 had higher levels of parental education (14.9 years (SD = 3.00) compared to 13.3 years (SD = 4.20)), t(881) = −5.90, p < .01, and were more likely to be families of female children (52.4% relative to 45.2%), χ2(1, N = 893) = 4.57, p = .03. Mothers, fathers, and adolescents provided data about parent-child relationship quality at Time 1, but during the pandemic, power to conduct analyses for father outcomes was limited by low sample size due to the truncated data collection period. Therefore, the association between disruption during the pandemic and adjustment is limited to young adults and their mothers.

Procedure and Measures

At Time 1, trained interviewers facilitated oral, written, or online interviews with participants according to participant need and preference. Interviews were conducted in participants’ homes or other locations chosen by the participants, and family members were interviewed separately to maintain confidentiality of responses. Time 1 interviews generally lasted between 60 and 90 minutes. At Time 2, interviews were conducted exclusively online or by telephone due to health concerns related to COVID-19, and typically lasted less than five minutes. Participants were provided modest financial compensation in appreciation of their participation, following institutional review board protocol in each site. Forward- and backward-translation of items and a process of cultural adaptation ensured linguistic and conceptual equivalence of measures (Erkut, 2010). Table 1 provides the descriptive statistics and correlations for the data used in these analyses. In addition, Table S1 provides the country-specific means and covariance matrices.

Table 1:

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

| Mean SD N |

Pearson Correlation Coefficients p-value N |

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | (14) | (15) | (16) | (17) | ||

| Young Adults - Change in Internalizing Problems since Pandemic Began (1) | 2.32 0.88 391 |

1 391 |

||||||||||||||||

| Mothers - Change in Internalizing Problems since Pandemic Began (2) | 2.33 0.86 383 |

0.23 <.01 308 |

1.00 383 |

|||||||||||||||

| Young Adults - Change in Externalizing Problems since Pandemic Began (3) | 1.84 0.76 391 |

0.55 <.01 391 |

0.13 0.02 308 |

1.00 391 |

||||||||||||||

| Mothers - Change in Externalizing Problems since Pandemic Began (4) | 1.69 0.77 383 |

0.18 0.0016 308 |

0.58 <.01 383 |

0.19 0.0009 308 |

1.00 383 |

|||||||||||||

| Young Adults - Personal Disruption from Pandemic (5) | 6.27 2.40 387 |

0.39 <.01 387 |

0.08 0.16 304 |

0.27 <.01 387 |

0.02 0.77 304 |

1.00 387 |

||||||||||||

| Mothers - Personal Disruption from Pandemic (6) | 6.02 2.55 380 |

0.09 0.13 306 |

0.40 <.01 380 |

0.03 0.62 306 |

0.22 <.01 380 |

0.19 0.00 303 |

1.00 380 |

|||||||||||

| Youth Disclosure - adolescent reported (7) | 0.00 0.80 671 |

0.1 0.04 368 |

0.02 0.67 365 |

−0.04 0.48 368 |

−0.07 0.16 365 |

0.15 0.01 364 |

−0.02 0.64 363 |

1.00 671 |

||||||||||

| Supportive Parenting - adolescent reported for mothers and fathers (8) | 0.02 0.66 671 |

−0.07 0.15 369 |

−0.03 0.61 365 |

−0.22 <.01 369 |

−0.07 0.15 365 |

0.05 0.30 365 |

0.06 0.26 363 |

0.37 <.01 669 |

1.00 671 |

|||||||||

| Supportive Parenting - adolescent reported for mothers only (9) | 0.03 0.73 663 |

−0.03 0.62 363 |

−0.01 0.78 364 |

−0.21 <.01 363 |

−0.08 0.11 364 |

0.12 0.02 359 |

0.03 0.51 362 |

0.38 <.01 662 |

0.83 <.01 663 |

1.00 663 |

||||||||

| Destructive Parent-Adolescent Conflict - parent-reported (10) | −0.01 0.57 685 |

0.08 0.14 372 |

0.22 <.01 370 |

0.17 0.00 372 |

0.27 <.01 370 |

−0.02 0.69 368 |

0.11 0.04 368 |

−0.19 <.01 660 |

−0.25 <.01 660 |

−0.30 <.01 653 |

1.00 685 |

|||||||

| Destructive Mother - Adolescent Conflict - mother-reported (11) | 0.00 0.64 663 |

0.10 0.06 360 |

0.22 <.01 367 |

0.17 0.00 360 |

0.30 <.01 367 |

−0.03 0.56 356 |

0.14 0.01 365 |

−0.16 <.01 645 |

−0.24 <.01 644 |

−0.30 <.01 642 |

0.88 <.01 663 |

1.00 663 |

||||||

| Young Adult is Male (12) | 0.51 893 |

−0.33 <.01 391 |

−0.06 0.21 383 |

−0.22 <.01 391 |

−0.04 0.43 383 |

−0.23 <.01 387 |

−0.05 0.34 380 |

−0.21 <.01 671 |

0.07 0.06 671 |

0.00 0.91 663 |

−0.02 0.56 685 |

−0.03 0.49 663 |

1.00 893 |

|||||

| Maximum Years of Education among Parents (13) | 14.16 4.17 883 |

0.10 0.06 387 |

0.02 0.63 383 |

0.10 0.06 387 |

0.04 0.44 383 |

−0.02 0.67 383 |

0.00 0.93 380 |

−0.03 0.43 665 |

0.11 0.00 665 |

0.05 0.19 657 |

0.13 0.00 680 |

0.09 0.02 658 |

0.00 0.89 883 |

1.00 883 |

||||

| Young Adults - Weeks Since Schools Closed due to Pandemic (14) | 10.40 3.60 391 |

0.06 0.25 391 |

−0.01 0.84 308 |

0.09 0.09 391 |

0.09 0.10 308 |

−0.17 0.00 387 |

−0.23 <.01 306 |

−0.04 0.43 368 |

−0.20 <.01 369 |

−0.17 0.00 363 |

0.07 0.21 372 |

0.06 0.22 360 |

0.07 0.18 391 |

−0.04 0.41 387 |

1.00 391 |

|||

| Mothers - Weeks Since Schools Closed due to Pandemic (15) | 9.85 3.86 384 |

0.01 0.81 309 |

−0.03 0.57 383 |

0.02 0.67 309 |

0.10 0.05 383 |

−0.16 0.00 305 |

−0.24 <.01 380 |

0.03 0.60 366 |

−0.15 0.00 366 |

−0.12 0.02 365 |

0.01 0.91 371 |

0.01 0.89 368 |

−0.01 0.89 384 |

−0.06 0.21 384 |

0.76 <.01 309 |

1.00 384 |

||

| Young Adults - Self Reported Internalizing in Adolescence (16) | 13.93 9.07 673 |

0.25 <.01 369 |

0.13 0.02 364 |

0.29 <.01 369 |

0.12 0.03 364 |

0.10 0.05 365 |

0.06 0.22 362 |

−0.07 0.07 670 |

−0.29 <.01 670 |

−0.26 <.01 662 |

0.17 <.01 661 |

0.15 0.00 645 |

−0.22 <.01 673 |

0.03 0.50 667 |

−0.02 0.69 369 |

0.02 0.64 365 |

1.00 673 |

|

| Young Adults - Self Reported Externalizing in Adolescence (17) | 10.65 6.65 673 |

0.07 0.18 369 |

−0.03 0.62 364 |

0.20 <.01 369 |

0.06 0.30 364 |

−0.02 0.73 365 |

0.02 0.73 362 |

−0.15 <.01 670 |

−0.27 <.01 670 |

−0.31 <.01 662 |

0.28 <.01 661 |

0.26 <.01 645 |

−0.02 0.69 673 |

0.02 0.70 667 |

0.04 0.40 369 |

0.12 0.02 365 |

0.58 <.01 673 |

1.00 673 |

Youth disclosure

Adolescent reports of youth disclosure at Time 1 were measured using a mean across three items from the Knowledge, Disclosure, Control, and Solicitation Scale (Stattin & Kerr, 2000). Items included adolescent reports of how much they freely offer information to parents (e.g., “Do you spontaneously tell your parents about your friends, [like] which friends you hang out with and how they think and feel about various things?”). The response scale was as follows: 0= never, 1=sometimes, 2=usually, 3=always. The disclosure scale has adequate reliability (α = .72). Using the alignment technique and the established guideline that approximate measurement invariance is achieved if less than 25% of intercepts and loadings are non-invariant (Muthén & Asparouhov, 2014), we find evidence of approximate measurement invariance for this scale with only 3% of the intercepts and loadings exhibiting non-invariance.

Supportive parenting

Supportive parenting was measured at Time 1 with adolescent reports for each parent separately using four behavioral items from Capaldi and Patterson (1989). Three of the items used a 0 to 4 Likert scale (0 = never to 4 = almost every day) to measure how much time the parent spends with the adolescent doing something the adolescent enjoys, how often the parent notices when the adolescent does a good job, and how often the parent shows the adolescent his/her help around the house is appreciated. The fourth item was “How many days a week does your mother/father sit and talk with you?” When estimating the outcomes for young adults, the four items for both parents were standardized and averaged to capture total supportive parenting the adolescent experienced from both parents (α = .84; r between parent scales = .40, p < .01). For mothers’ outcomes, however, only the four items about mothers’ supportive parenting were included in the scale (α =.76). Alignment analyses provided evidence of approximate measurement invariance for both versions of this scale with only 3 and 8% of the intercepts and loadings exhibiting non-invariance, respectively.

Because our aim is to capture aspects of the parent-child relationship present in adolescence that may be related to youth adjustment a few years later, we combined mother and father responses from the supportive parenting measure, and again for the destructive conflict scales as described below. A focus on differences between parent-child relationship dyads (mother-daughter, father-daughter, e.g.) is beyond the scope of this paper. The correlation between mother and father reports within each scale is only moderate, but from an adolescent perspective, high levels of conflict and/or low levels of support - regardless of the source – would signal a parent-child relationship climate present during adolescence that may be problematic.

Destructive parent-adolescent conflict

Parent and adolescent behaviors during conflicts with each other and outcomes following conflict were measured using Honess et al.’s (1997) adaptation of Rands et al.’s (1981) and Camara and Resnick’s (1989) work. First, mothers and fathers were asked to what extent anger and aggression characterize disagreements between the parent and child, measuring both the parent’s and child’s behavior during the conflict (7 items each; e.g., gets wound up and walks away, gets sarcastic, says or does something to hurt feelings; mother α = .90; father α = .89; r between parent scales = .31, p < .01). The items were scored from 0 to 4 based on how well each item describes first the child and then the parent, with 0 = not at all to 4 = very well. Alignment analyses provided evidence of approximate measurement invariance for the mother- and father-reported scales with only 4 and 0% of the intercepts and loadings exhibiting non-invariance, respectively. In the second part of the measure the parent rated how often each of 11 possible escalation outcomes followed a disagreement, with responses ranging from 1 =never to 5 = very often. Items included statements such as “I end up feeling annoyed and angry” and “Later [my child] uses what I’ve said against me” (mother α = .91; father α = .90; r between parent scales = .30, p < .01). Alignment analyses provided evidence of approximate measurement invariance for the mother- and father-reported scales with only 4 and 1% of the intercepts and loadings exhibiting non-invariance, respectively. Together, the anger response and escalation outcome describe a destructive form of conflict resolution. When estimating the outcomes for young adults, the non-missing values for the two scales for both parents were standardized and averaged to capture total destructive conflict the adolescent experienced from both parents. Although the correlations between parent reports of each of the scales are only moderate, the alpha across all 4 subscales shows adequate reliability (α = .76). For mothers’ outcomes, however, only the two mother-reported subscales were averaged (r = .77, p < .01).

Experiences with COVID-19

We developed a 19-question measure about COVID-related experiences, Experiences Related to COVID-19 (see Appendix), after reviewing the literature on parent and adolescent stress responses following major traumatic events, including natural disasters (e.g., Bermudez et al., 2019; Hafstad et al., 2012), 9/11 (Calderoni et al., 2006; Hendricks & Bornstein, 2007), ongoing political violence (Cárdenas Castro et al., 2019; Gelkopf et al., 2012), and previous public health crises such as the SARS outbreak (Hawryluck et al., 2004) and H1N1 (Rubin et al., 2009). As a pilot test and to obtain data as early as possible as the United States responded to the pandemic, we began administering the measure via Qualtrics and telephone in the United States in March 2020. We made minor revisions to the measure based on initial responses. For this study, we utilized the following items:

COVID-19 personal disruption.

Mothers and young adults rated how disruptive the pandemic has been to them personally, taking into account daily routines, work, and family life, and using a scale from 1 to 10, with 1= not very disruptive to 10 = extremely disruptive.

Increases in internalizing and externalizing behavior.

Mothers and young adults independently self-reported increases in their own anxiety, depression, anger, and argumentativeness now as compared to before the outbreak of COVID-19 in their community. Increases in internalizing for each respondent were assessed by averaging two items (young adult items r = .55, p < .01, mother items r = .61, p < .01): “I feel more anxious now than I did before the outbreak” and “I feel more depressed now than I did before the outbreak.” Increases in externalizing behavior were also measured by averaging two items (young adult items r = .51, p < .01, mother items r = .54, p < .01): “I get in more arguments now than I did before the outbreak” and “I feel more angry now than I did before the outbreak.” Responses included 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = somewhat disagree, 3 = somewhat agree, 4 = strongly agree.

Covariates

We controlled for child gender because males’ and females’ externalizing and internalizing behaviors may be affected differently by stressful life events (e.g., Armstrong et al., 2018). We controlled for the number of weeks elapsed between public school closures in each country/state and the COVID-19 data collection to capture the length of time that COVID had been causing community-wide disruptions in each location, which might predict individuals’ perceptions of how disruptive COVID had been to them personally and increases in their internalizing and externalizing behaviors. As a proxy for SES, we utilized parental education - measured as the highest level of education attained by either parent at the time of recruitment. For young adult internalizing and externalizing Time 2 outcomes, we controlled for adolescent-reported internalizing and externalizing problems at Time 1, respectively, using 30 externalizing and 29 internalizing items from the Youth Self-Report of the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 1991). Data capturing mothers’ internalizing and externalizing problems were not available at Time 1.

Analytic Plan

Using full information maximum likelihood to account for data missing at random, multiple group path analyses were estimated using Mplus version 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 2018). The initial models constrained the path coefficients to be equal across countries but allowed the intercepts, covariances, and residual variances to vary by country. Model fit was deemed good if the majority of a diverse set of fit statistics met established criteria: non-significant chi-square test of model fit, CFI greater than or equal to .95, RMSEA less than or equal to .06, and SRMR less than or equal to .08 (Kline, 2011). When the initial model did not yield good fit, country-specific coefficients were released based on modification indices until good model fit was achieved. For each outcome, a main effects model was first estimated to assess the impact of COVID-19 personal disruption as well as youth disclosure, supportive parenting, and destructive parent-adolescent conflict during adolescence. These models also controlled for parents’ education, weeks since the pandemic began, and gender (for the young adult models only). Standardized coefficients are presented to capture the SD change in the outcome associated with a 1 SD increase in the predictor.

For each outcome, three additional models were estimated, one for each of the potential moderators. Each moderation model included all the original predictors as well as the interaction between the moderator and disruption. When the interaction term capturing moderation was statistically significant, the relation between the outcome and disruption was plotted for three values of the moderator (1 SD below M, at the M, and 1 SD above M). In addition, the region of significance for the slopes capturing the relation between disruption and the outcome at different levels of the moderator was calculated (Preacher et al., 2006). Given that intercepts and sometimes coefficients vary across countries, these figures and analyses were produced for each country separately when the moderator was significant; however, only one representative figure is presented. Figures S1–S8 display all the significant moderation effects for each country.

Results

The complete results are provided in the Tables and Supplemental Tables. All models met adequate fit criteria, and the fit statistics are included in the Tables. Unless noted, the results presented are significant at the .05 level or less. Only results consistent across countries and related to the research questions are discussed.

Internalizing Problems

Higher levels of personal disruption due to COVID-19 were associated with greater increases in internalizing problems since the pandemic began for young adults and mothers (Table 2). Among young adults and mothers in all countries except Italy, a 1 SD increase in personal disruption was associated with 0.26 SD and 0.31 SD increase in internalizing problems since the pandemic began, respectively. Among Italian young adults and mothers, the magnitude of the association was larger: A 1 SD increase in personal disruption was associated with 0.49 SD and 0.56 SD increases in internalizing problems, respectively.

Table 2:

FIML Multiple Group Model Results Estimating Increase in Internalizing and Externalizing Problems since Pandemic Began

| Change in Internalizing Problems | Change in Externalizing Problems | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Young Adults: b(SE) | Mothers: b(SE) | Young Adults: b(SE) | Mothers: b(SE) | |

|

| ||||

| COVID-19 Personal Disruption | 0.26 (0.05)*** | 0.31 (0.05)*** | 0.47 (0.07)*** | 0.2 (0.05)*** |

| Youth Disclosure | −0.04 (0.06) | 0.01 (0.05) | 0.02 (0.06) | 0 (0.04) |

| Destructive Parent-Adolescent Conflict | −0.02 (0.05) | 0.1 (0.05)** | 0.04 (0.05) | 0.23 (0.06)*** |

| Supportive Parenting | 0.11 (0.06)* | 0.01 (0.05) | −0.13 (0.05)** | −0.02 (0.05) |

| Weeks since Schools Closed due to Pandemic | 0.11 (0.06)* | −0.02 (0.06) | 0.02 (0.05) | 0.08 (0.07) |

| Parental Years of Education | 0.11 (0.04)*** | 0.03 (0.05) | −0.1 (0.05)* | −0.01 (0.05) |

| Young Adult is Male | −0.41 (0.09)*** | −0.3 (0.09)*** | ||

| Youth-Reported Int/Externalizing in Adolescence | 0.15 (0.05)*** | 0.19 (0.06)*** | ||

| Country-Specific Coefficients | ||||

| Italy - COVID-19 Personal Disruption | 0.49 (0.07)*** | 0.56 (0.08)*** | 0.54 (0.09)*** | |

| Italy - Youth Disclosure | 0.2 (0.08)** | |||

| Italy - Supportive Parenting | −0.32 (0.08)*** | |||

| Philippines - COVID-19 Personal Disruption | 0.1 (0.09) | |||

| Philippines - Youth Disclosure | 0.32 (0.1)*** | 0.26 (0.1)** | ||

| Philippines - Parental Years of Education | −0.25 (0.09)*** | 0.29 (0.08)*** | ||

| Thailand COVID-19 Personal Disruption | −0.08 (0.08) | |||

| Thailand - Destructive Parent-Adolescent Conflict | −0.03 (0.1) | |||

| Thailand - Weeks since Schools Closed due to Pandemic | −0.76 (0.25)*** | |||

| US - COVID-19 Personal Disruption | 0.19 (0.09)** | |||

| US - Youth Disclosure | −0.15 (0.09) | |||

| US - Parental Years of Education | 0.35 (0.11)*** | |||

| Model Fit Statistics | ||||

| Chi Square (DOF), p-value | 34.81(29), p=0.21 | 22.37(21), p=0.38 | 32.06(25), p=0.16 | 27.76(21), p=0.15 |

| CFI | 0.95 | 0.99 | 0.94 | 0.91 |

| RMSEA | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| SRMR | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

For young adult models, supportive parenting and destructive conflict capture the behaviors for both mothers and fathers. For mother models, supportive parenting and destructive conflict capture behavior for mothers only. b=standardized coefficient,

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.10

Among mothers only, more destructive mother-adolescent conflict was associated with greater increases in internalizing problems since the pandemic began. A 1 SD increase in destructive mother-adolescent conflict was associated with 0.10 SD increase in internalizing problems since the pandemic began. The main effects of youth disclosure and supportive parenting during adolescence were not significantly related to internalizing problems for young adults or mothers.

Externalizing Problems

For both young adults and mothers, higher levels of personal disruption due to COVID-19 were associated with greater increases in externalizing problems since the pandemic began (Table 2), although the magnitude of the relation was stronger in some countries than others. Among young adults in the U.S., a 1 SD increase in personal disruption was associated with a 0.19 SD increase in externalizing problems. However, among young adults in Italy and Sweden, a 1 SD increase in personal disruption was associated with a 0.47 SD increase in externalizing problems. Among young adults in the Philippines and Thailand, the relation was not statistically significant. Among mothers in all countries except Italy, a 1 SD increase in personal disruption was associated with 0.20 SD increase in externalizing problems. Among Italian mothers, the magnitude of the association was larger: A 1 SD increase in personal disruption was associated with 0.54 SD increase in externalizing problems.

Among mothers only in all countries except Thailand, higher levels of destructive conflict during adolescence were associated with greater increases in externalizing problems since the pandemic began. A one SD increase in destructive mother-adolescent conflict was associated with a 0.23 SD increase in mother’s externalizing problems since the pandemic began. Among young adults only, a 1 SD increase in supportive parenting during adolescence was associated with 0.13 SD decrease in externalizing problems since the pandemic began. The main effects of youth disclosure during adolescence were not significantly related to externalizing problems for young adults or mothers.

Moderation of the Relation between Personal Disruption and Internalizing Problems

Table 3 provides the results and fit statistics for all moderation models. Among young adults, there was no consistent evidence across countries that the relation between COVID-19 personal disruption and internalizing problems was moderated by youth disclosure, supportive parenting, or destructive conflict during adolescence.

Table 3:

FIML Multiple Group Model Results Estimating Moderation of COVID-19 Personal Disruption relation to the Increases in Internalizing and Externalizing Problems

| Change in Internalizing Problems | Change in Externalizing Problems | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Young Adults: b(SE) | Mothers: b(SE) | Young Adults: b(SE) | Mothers: b(SE) | |

|

| ||||

| Moderation by Youth Disclosure | ||||

| COVID-19 Personal Disruption | 0.26 (0.05)*** | 0.38 (0.05)*** | 0.1 (0.06) | 0.16 (0.05)*** |

| Youth Disclosure | −0.04 (0.06) | 0.01 (0.05) | −0.02 (0.05) | −0.02 (0.04) |

| Youth Disclosure*Disruption | −0.02 (0.04) | −0.12 (0.05)** | −0.19 (0.05)*** | −0.09 (0.04)** |

| Country-Specific | ||||

| Italy - COVID-19 Personal Disruption | 0.49 (0.07)*** | 0.44 (0.09)*** | 0.53 (0.09)*** | |

| Italy - Youth Disclosure | 0.19 (0.08)** | |||

| Philippines - COVID-19 Personal Disruption | 0.1 (0.06) | |||

| Philippines - Youth Disclosure | 0.39 (0.1)*** | 0.27 (0.11)** | ||

| Philippines - Youth Disclosure*Disruption | −0.08 (0.08) | 0.02 (0.07) | 0.16 (0.09)* | |

| Sweden - COVID-19 Personal Disruption | 0.53 (0.1)*** | |||

| Thailand - COVID-19 Personal Disruption | −0.09 (0.08) | |||

| Thailand - Youth Disclosure*Disruption | 0.08 (0.08) | |||

| Model Fit Statistics | ||||

| Chi Square (DOF), p-value | 36.09(33), p=0.33 | 28.2(24), p=0.25 | 33.55(28), p=0.92 | 30(24), p=0.18 |

| CFI | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.93 |

| RMSEA | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| SRMR | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

|

| ||||

| Moderation by Supportive Parenting | ||||

| COVID-19 Personal Disruption | 0.26 (0.05)*** | 0.37 (0.04)*** | 0.47 (0.07)*** | 0.18 (0.05)*** |

| Supportive Parenting | 0.11 (0.06)* | 0.02 (0.05) | −0.13 (0.05)** | −0.01 (0.05) |

| Supportive Parenting*Disruption | 0 (0.04) | −0.17 (0.04)*** | −0.06 (0.04)* | −0.09 (0.04)** |

| Country-Specific | ||||

| Italy - COVID-19 Personal Disruption | 0.49 (0.07)*** | 0.52 (0.08)*** | ||

| Italy - Supportive Parenting | −0.32 (0.08)*** | |||

| Philippines - COVID-19 Personal Disruption | 0.09 (0.09) | |||

| Sweden - Supportive Parenting*Disruption | 0.31 (0.12)*** | |||

| Thailand - COVID-19 Personal Disruption | −0.05 (0.09) | |||

| US - COVID-19 Personal Disruption | 0.18 (0.09)* | |||

| Model Fit Statistics | ||||

| Chi Square (DOF), p-value | 36.39(33), p=0.31 | 28.02(23), p=0.22 | 37.99(30), p=0.15 | 30.8(24), p=0.16 |

| CFI | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.92 |

| RMSEA | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.039 | 0.04 |

| SRMR | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

|

| ||||

| Moderation by Destructive Parent-Adolescent Conflict | ||||

| COVID-19 Personal Disruption | 0.38 (0.05)*** | 0.39 (0.05)*** | 0.47 (0.07)*** | 0.26 (0.06)*** |

| Destructive Parent-Adolescent Conflict | −0.03 (0.05) | 0.02 (0.05) | 0.04 (0.05) | 0.22 (0.06)*** |

| Destructive Parent-Adolescent Conflict*Disruption | −0.04 (0.05) | 0.09 (0.04)** | −0.02 (0.04) | 0.06 (0.05) |

| Country-Specific | ||||

| Italy - Destructive Parent-Adolescent Conflict | 0.25 (0.09)*** | |||

| Philippines - COVID-19 Personal Disruption | 0.1 (0.09) | |||

| Thailand - COVID-19 Personal Disruption | −0.1 (0.09) | |||

| Thailand - Destructive Parent-Adolescent Conflict | −0.06 (0.1) | |||

| Thailand - Destructive Parent-Adolescent Conflict*Disruption | 0.32 (0.1)*** | |||

| Sweden - Destructive Parent-Adolescent Conflict*Disruption | −0.47 (0.21)** | |||

| US - COVID-19 Personal Disruption | 0.19 (0.09)** | 0.05 (0.09) | ||

| Model Fit Statistics | ||||

| Chi Square (DOF), p-value | 39.58(33), p=0.2 | 29.6(24), p=0.2 | 35.79(29), p=0.18 | 23.35(22), p=0.93 |

| CFI | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.98 |

| RMSEA | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| SRMR | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

Only the predictors relevant to moderation are present here; however, the complete group of predictors used in Table 2 were included in these models. The complete results for each model are displayed in Tables S2–S4. For young adult models, supportive parenting and destructive conflict capture the behaviors for both mothers and fathers. For mother models, supportive parenting and destructive conflict capture behavior for mothers only. b=standardized coefficient.

p < .01,

p < .05,

p < .10

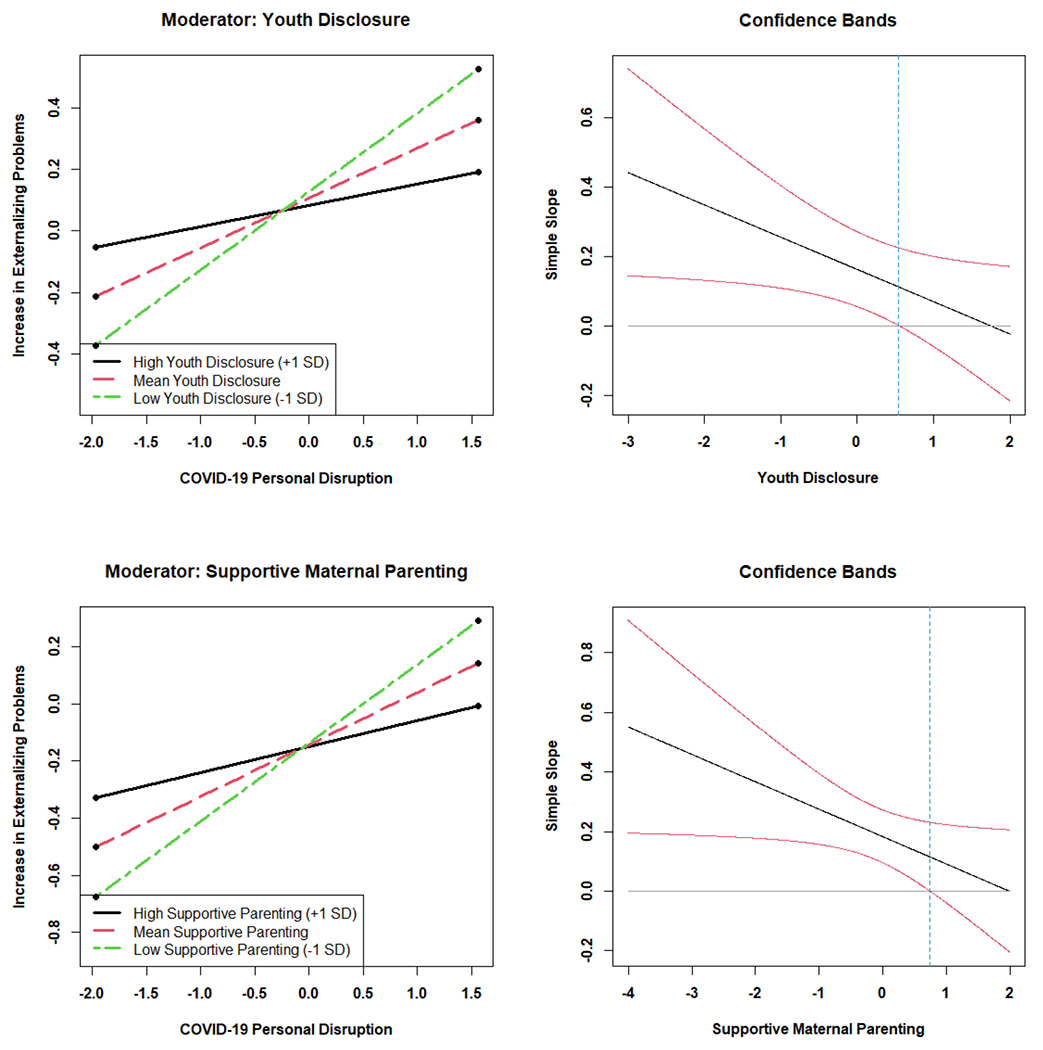

Among mothers in all countries except the Philippines, youth disclosure during adolescence moderated the relation between mothers’ personal disruption and internalizing problems since the pandemic began. As seen in the first panel of Figure 1, greater personal disruption was associated with greater increases in internalizing problems during the pandemic among mothers who experienced low (1 SD below M), average, and high (1 SD above M) levels of disclosure with their child during adolescence. However, the association was attenuated for mothers who experienced greater disclosure from their child during his/her adolescence as indicated by the flattening of the slope as disclosure increases. In these countries with significant moderation, analyzing the regions of significance for the simple slopes revealed that the slopes presented in the figure were all significantly different from zero. Among mothers who experienced extremely high levels of disclosure during their child’s adolescence (greater than approximately 1.55 SD above M) the relation between disruption and internalizing problems was not significantly different from zero. This result suggested that experiencing extremely high levels of disclosure from a child during his/her adolescence completely protected mothers against rising internalizing problems in the midst of COVID-19 personal disruption (and, conversely, that the association between disruption during the pandemic and mothers’ increased internalizing was exacerbated when adolescents had disclosed little).

Figure 1:

Moderation of Relation between Personal Disruption during the Pandemic and Mothers’ Increase in Internalizing Problems

1st Panel: Results for Italy are shown with a region of significance outside (1.56, 16.01) indicating that the slope was not significantly different from zero at high levels of disclosure (> 1.56 SD above the M). The results were similar for Sweden, Thailand, and the U.S. Full set of figures provided in Figure S2.

2nd Panel: Results for Italy are shown with a region of significance outside (1.32, 4.61) indicating that the slope was not significantly different from zero at high levels of supportive parenting (> 1.32 SD above the M). The results were similar for the Philippines, Thailand, and the U.S. The moderation is in the opposite direction for Sweden. Full set of figures provided in Figure S3.

3rd Panel: Results for the Philippines are shown with a region of significance outside (−67.55, −2.07) indicating that the slopes are significant for the entire distribution of destructive mother-adolescent conflict. The results are similar for all other countries. Full set of figures provided in Figure S4.

Among mothers in all countries except Sweden, maternal supportive parenting during the child’s adolescence moderated the relation between COVID-19 personal disruption and mothers’ internalizing problems since the pandemic began. Greater personal disruption was associated with greater increases in internalizing problems during the pandemic, but the association was attenuated for mothers whose child reported greater maternal supportive parenting in adolescence (Figure 1 – 2nd panel). In all countries except Sweden, an analysis of the regions of significance for the simple slopes revealed that the relation between disruption and increases in internalizing problems was not significantly different from zero at supportive parenting levels greater than approximately 1.31 SD above M. These results suggested that providing high levels of supportive parenting during a child’s adolescence completely protected mothers against rising internalizing problems in the midst of COVID-19 personal disruption. The findings from Sweden showing a different pattern are presented in Figure S3.

Among mothers in all countries, destructive mother-adolescent conflict during adolescence moderated the relation between COVID-19 personal disruption and internalizing problems since the pandemic began. Greater personal disruption was associated with greater increases in internalizing problems during the pandemic, but the association was attenuated for mothers who experienced less destructive mother-adolescent conflict with their child during his/her adolescence (Figure 1 – 3rd panel). An analysis of the regions of significance for the simple slopes revealed that the relation between disruption and increases in internalizing problems was significantly different from zero at all levels of destructive mother-child conflict during adolescence.

Moderation of the Relation between Personal Disruption and Externalizing Problems

Among young adults in Italy, Sweden and the U.S., greater personal disruption was associated with greater increases in externalizing problems during the pandemic, but the association was attenuated for young adults who disclosed more to their parents during adolescence (Figure 2). An analysis of the regions of significance for the simple slopes for Italy and Sweden revealed that among young adults who reported high levels of disclosure during adolescence (greater than 1.18 SD above M in Italy and 1.49 SD above M in Sweden) the relation between disruption and externalizing problems was not significantly different from zero (1st panel of Figure 2). This result indicated that high levels of disclosure in adolescence completely protected young adults against rising externalizing behavior in the midst of COVID-19 personal disruption.

Figure 2:

Moderation of Relation between Personal Disruption during the Pandemic and Young Adults’ Increase in Externalizing Problems

1st Panel: Results for Italy are displayed with a region of significance outside (1.18, 6.25) indicating that the slopes were not significantly different from zero at high levels of youth disclosure (> 1.18 SD above the M). The results were similar for Sweden.

2nd Panel: Results for US are displayed with a region of significance outside (−0.14, 1.84) indicating that the slopes were not significantly different from zero at youth disclosure values within this range.

Full set of figures provided in Figure S5.

In the U.S. (2nd panel of Figure 2), the protective nature of youth disclosure in adolescence was even more pronounced. Among youth who experienced low levels of disclosure in adolescence (disclosure more than 0.14 SD below M), the relation between disruption and increases in externalizing problems was positive but decreasing as disclosure increased. At disclosure levels greater than 0.14 SD, the relation was not significantly different from zero indicating that disclosure at these levels in adolescence completely protected young adults against rising externalizing behavior in the midst of COVID-19 personal disruption.

There was no consistent evidence across countries that the relation between COVID-19 personal disruption and increases in externalizing problems among young adults was moderated by supportive parenting or destructive parent-adolescent conflict during adolescence.

Among mothers in all countries except the Philippines, youth disclosure during adolescence moderated the relation between COVID-19 personal disruption and externalizing problems during the pandemic. Greater personal disruption was associated with greater increases in externalizing problems during the pandemic, but the association was attenuated for mothers who experienced greater disclosure from their child during his/her adolescence (Figure 3 – 1st panel). In Sweden, Thailand, and the U.S., the regions of significance for the simple slopes revealed that the relation between disruption and increases in externalizing problems was not significantly different from zero at disclosure levels greater than approximately 0.53 SD above M. These results suggested that experiencing high levels of disclosure from a child during his/her adolescence completely protected mothers against rising externalizing behavior in the midst of COVID-19 personal disruption. In Italy, the slopes decreased as disclosure rose across the entire distribution of disclosure, but disclosure never completely eliminated the positive relation between disruption and externalizing problems.

Figure 3:

Moderation of Relation between Personal Disruption during the Pandemic and Mothers’ Increase in Externalizing Problems

1st Panel: The results for the U.S. are displayed with a region of significance outside (0.54, 29.94) indicating that the slopes were not significantly different from zero at higher levels of youth disclosure (> 0.54 SD above the M). The same pattern of moderation emerges in Thailand and Sweden. In Italy, the slopes are slightly steeper due to a higher coefficient on disruption, and the simple slopes are significantly different from zero for all possible disclosure values. Full set of figures provided in Figure S6.

2nd Panel: The results for the Philippines are displayed with a region of significance outside (0.74, 56.44) indicating that the slopes were not significantly different from zero at higher levels of supportive parenting (> 0.74 SD above the M). The same pattern of moderation emerges in Thailand, Sweden, and the U.S. In Italy, the slopes are slightly steeper due to a higher coefficient on disruption, and the simple slopes are significantly different from zero for all possible supportive parenting values. Full set of figures provided in Figure S7.

Among mothers in all countries, maternal supportive parenting during adolescence moderated the relation between COVID-19 personal disruption and mothers’ externalizing problems since the pandemic began. Greater personal disruption was associated with greater increases in externalizing problems during the pandemic, but the association was attenuated for mothers whose child reported greater maternal supportive parenting in adolescence (Figure 3 – 2nd panel). In the Philippines, Sweden, Thailand, and the U.S., the regions of significance for the simple slopes revealed that the relation between disruption and increases in externalizing problems was not significantly different from zero at supportive parenting levels greater than approximately 0.74 SD above M. These results suggested that providing high levels of supportive parenting during a child’s adolescence completely protected mothers against rising externalizing behavior in the midst of COVID-19 personal disruption. In Italy, the slopes decreased as maternal supportive parenting rose across the entire distribution of supportive parenting, but supportive parenting never completely eliminated the positive relation between disruption and externalizing problems.

Destructive conflict did not significantly moderate the association between disruption during the pandemic and mothers’ externalizing behaviors, except in Sweden (see Figure S8).

Discussion

The overall aims of this study were to examine disruptions during the COVID pandemic in relation to reported increases in internalizing and externalizing of young adults and their mothers in five countries, and to examine the role of prior parent-adolescent relationship qualities as moderators of the associations between pandemic disruption and adjustment in young adults and their mothers. As has been summarized in other work (see Brooks et al., 2020), the pandemic is associated with notable increases in self-reported levels of problematic mental health indicators among parents and young adults. In our sample from five countries, more than half of the young adults reported an increase in anxiety or sadness during the pandemic, and nearly one-third reported increases in externalizing behaviors.

Using an ongoing, cross-national, longitudinal study, we first hypothesized that the level of disruption reported by young adults and mothers would predict increases in internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Our hypothesis was supported. With the exception of externalizing behaviors of young adults in Thailand and the Philippines, the level of pandemic-related disruption reported by young adults and mothers predicted self-reported COVID-19-related changes in adjustment following the onset of the pandemic.

Among mothers in Italy (and young adults in Italy, for internalizing behaviors), the negative impacts of pandemic-related disruptions on anxiety, and depression, anger and argumentativeness were particularly strong. At the time of the brief COVID assessment, Italy was experiencing its first wave of COVID-related infections and deaths, as well as strict government lockdown measures, which may have contributed to the strength of the findings. In general, respondents in all sites reported greater adjustment difficulties in accord with more experiences of disruption, consistent with other reports of elevated mental health problems associated with the pandemic among adults (e.g., Liu et al., 2020).

We also hypothesized that qualities of the parent-adolescent relationship assessed prior to COVID would moderate associations between the level of disruption experienced during the pandemic and young adults’ and their mothers’ reports of increases in internalizing and externalizing during the pandemic. This hypothesis was generally supported, but the specifics of the moderation effects differed for young adults and their mothers and for youth disclosure, supportive parenting, and destructive parent-adolescent conflict. Youth disclosure in adolescence buffered the negative impact of pandemic disruptions on internalizing (for mothers, except mothers in the Philippines) and externalizing behaviors (for mothers and young adults, except young adults in the Philippines and Thailand). High levels of adolescent disclosure may be a particularly important marker of open parent-child communication and positive relationship quality, given normative declines in disclosure across adolescence (Lionetti et al., 2019). A history of disclosure may buffer against anger and arguments during the pandemic and also alleviates mothers’ anxieties (Hamza & Willoughby, 2011). However, youth disclosure may have different meanings or functions in Asian families, where restraint and authority are emphasized over intimacy and openness (Yau et al., 2009).

For mothers in all sites (except Sweden for internalizing behaviors) supportive parenting likewise attenuated the impact of pandemic-related disruptions on internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Because supportive parenting was measured in terms of caregiver behaviors toward the child, its moderating effect for mothers may be, in part, a function of the mothers’ characteristics. For instance, warmth, acceptance, and spending time with the child may be associated with maternal qualities that protect against adjustment problems.

Destructive conflict in adolescence also moderated the relation between pandemic disruption and increases in internalizing behavior for mothers in all sites (and among young adults in Thailand), and increases in externalizing behaviors for mothers in Sweden. Lower levels of destructive conflict during adolescence attenuated the relation between pandemic disruption and increasing maternal internalizing and externalizing behavior. Our finding confirms decades-old work showing that conflicts featuring anger and escalation rather than problem-solving and compromise are associated with negative outcomes in other domains, including later adjustment (Reese-Weber & Bartle-Haring, 1998; Rinaldi & Howe, 2003). Surprisingly, destructive conflict in adolescence did not moderate any relations among the young adults, suggesting differential long-term effects of conflict on adolescents and their parents. It is possible that the destructive conflict meant more to the mothers than the adolescents, hence the impact on mothers’ later adjustment.

We probed interaction effects to examine values of the parent-child relationship characteristics (i.e., disclosure, supportive parenting, and destructive conflict) where the interaction between pandemic disruption and mother or young adult changes in adjustment moved from significant to non-significant. In doing so, we found that increases in positive parent-adolescent relationship quality attenuated negative pandemic effects for a substantial range of moderator values. There were some instances where extremely high levels of the moderator resulted in interaction slopes that were not different from zero, suggesting that very high levels of the moderator may be completely protective. Yet the practical implications of this are limited to the small portion of the sample exhibiting very high levels of the moderators. For example, at extremely high levels of adolescent disclosure, the relations between disruption and both mothers’ increase in internalizing behavior and youth increases in externalizing behavior are completely attenuated. However, extremely high levels of adolescent disclosure are typically non-normative at age 17 and could have other detrimental effects not measured here. Interpretation of these bounds should thus be viewed with caution.

The global nature of the pandemic is a double-edged sword. On one hand, unlike other individually experienced traumas, parents and their young adult children may share many of the same losses, fears, and frustrations, such as personal health concerns and worry about the health of loved ones, loss of social connections, and interruptions to daily routines, which may make it easier for young adults and their parents to relate to one another via a common, shared experience. Hafstad et al. (2012) found this shared experience to be critical to the successful application of supportive parenting for Norwegian families in Southeast Asia following the 2004 tsunami. On the other hand, when every family member is experiencing loss and abrupt change, disruptions in the family system may be more extensive, and thus it is more difficult to be attuned and respond to the behavioral and emotional needs of others. Thus, a history of a strong parent-child relationship is critical for buffering the effect of the pandemic on feelings of sadness, anxiety, anger, and irritability.

This study adds to the existing COVID-19 literature in a number of ways. Beyond simply documenting cross-sectional associations between pandemic disruption and adjustment, we utilized a longitudinal study of parenting and child development with samples from five countries to examine interactions between prior parent-child relationship quality and disruption during the pandemic in predicting reported changes in adjustment during the pandemic. We examined these relations in a group of countries diverse with respect to the timing and spread of the COVID-19 outbreak and governmental response.

An implication of these findings for intervention and prevention efforts is that fostering parent-child relationships characterized by warmth, acceptance, trust, open communication, and constructive conflict resolution is always important, at any time, given their protective effects during times of crises. Open, supportive parent-child relationships build resilience among parents as well as their children. It is insufficient to think about supporting families and addressing traumas and mental health problems during or in the aftermath of a disaster or public health crisis. We will continue to have disasters and pandemics in the future, so it is important to take the long view, a proactive and preventive perspective in supportive parenting interventions to build resilient families.

Some study limitations should be noted. First, despite within-country diversity in economic security and education, we did not include nationally representative samples from each country and thus cannot generalize results to entire countries. Second, the COVID-19 measures of adjustment are based on a self-reported comparison to pre-pandemic levels of internalizing and externalizing behavior. Although we were able to control for pre-pandemic adolescent-reported internalizing and externalizing behavior, we were not able to do so for mothers. However, self-reports of mental health changes have been shown to be correlated with objective measures (e.g., Zimmerman et al., 2004). Third, this study does not account for changes in parent-child relationship quality in the three years between the two assessment points. The parent-child relationship and co-parenting relationship during a pandemic may be quite different from relationships during ordinary times due to familial stress, and concurrent parenting may be especially salient for internalizing and externalizing problems during these stressful times. Additionally, recent cross-national research shows that how parents jointly cope with stress is a predictor of both mother-child relationship quality and an indirect predictor of adolescent externalizing behavior over a two-year period (Skinner et al., 2021). This dyadic coping could account for some of the variance in changes in well-being during the pandemic. However, although this study did not utilize repeated measures of the parent-child relationship over time, assessment of disclosure, supportive parenting, and destructive conflict could not be asked in the same way at both age 17 and age 20, since many 20-year-olds are not living with their parents and have fewer opportunities for such interactions.

Fourth, we did not have data on whether young adults were living with their parents during the pandemic or whether their living arrangements changed during the pandemic; changes in living arrangements could have contributed to individuals’ perceptions of disruptions during the pandemic as well as the extent to which earlier parent-child relationship characteristics (and, perhaps, concurrent parenting) were related to perceived changes in young adults’ and their mothers’ well-being. Fifth, theoretical models (e.g., Sameroff, 2010) and empirical studies (e.g., Rackoff & Newman, 2020) increasingly recognize and demonstrate that the impact of stressful events may differ from family to family, and from individual to individual. Although we were able to describe specific moderation effects by examining regions of significance, the current design was not able to examine detailed heterogeneity at this more specific level, that is, whether some children may benefit and others may develop problems. Further research is needed to examine differential susceptibility to stressors associated with COVID. However, it is also important from a public health perspective to provide information on overall patterns, as we have done, because even if there are small subgroups in which the effects differ from the main patterns, public policymakers want to know what general recommendations are prudent. For example, not all people who smoke get lung cancer, but emphasizing that would be dangerous from a public health standpoint. Finally, the associations between disruption and adjustment are not causal and could be alternately interpreted as increased levels of internalizing and externalizing problems predicting the level of life disruption.

Taken together, the results have implications for understanding associations between perceptions of COVID-19 disruptions and young adults’ and their mothers’ adjustment, as well as how these associations are moderated by prior parent-adolescent relationship qualities. Qualities of the parent-child relationship during adolescence around the world may serve to protect children from increases in maladaptive behavior during major negative life events not just during childhood and adolescence, but into young adulthood. Mothers also benefitted from these protective effects, suggesting that strong parent-adolescent relationships characterized by open communication, support, and positive conflict resolution are enduring resources that can promote family resilience during times of unprecedented stress.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research has been funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant RO1-HD054805, by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Grant P30 DA023026, the Intramural Research Program of the NIH/NICHD, USA, and an International Research Fellowship at the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), London, UK, funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 695300-HKADeC-ERC-2015-AdG). The authors note no conflicts of interest. The authors also wish to thank W. Andrew Rothenberg and Madeline M. Carrig for their statistical consultation and advice.

APPENDIX

(Note: Bolded items were included in the present study.)

Experiences Related to COVID-19

Instructions: Thinking about your thoughts, feelings, and behaviors around the COVID-19 (coronavirus) illness, please answer the following questions:

| Strongly disagree | Somewhat disagree | Somewhat agree | Strongly agree | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | We recognize that many local, state, and federal government agencies are involved in the response to COVID-19. Balancing your perspective on all these agencies: I am confident the government is handling the COVID-19 response in the best possible manner. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||||

| 2. | I am hopeful that the COVID-19 virus will resolve over time and I have a good outlook toward the future. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||||

| 3. | I complied with the rules and suggestions of the government and health care system to try to contain the virus. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||||

| 4. | I found it easy to comply with the rules and suggestions of the government and health care system to try to contain the virus |

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||||

| 5. | Do you have a close friend or loved one who has tested positive for the COVID-19 virus? | |||||||||

| 0=no | ||||||||||

| 1=yes | ||||||||||

| 6. | This may be a difficult question, but has someone close to you lost their life due to the COVID-19 virus? | |||||||||

| 0=no | ||||||||||

| 1=yes | ||||||||||

| 7. | Please indicate how close you are to this person (skip if answer to question 6 = no) | |||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| Not close at all | Very close | |||||||||

Think about your behavior in the year prior to outbreak of COVID-19 (coronavirus) and your behavior now. Please use the following scale.

| Decreased a lot since the outbreak | Decreased a little since the outbreak | Stayed about the same since before the outbreak | Increased a little since the outbreak | Increased a lot since the outbreak | I did not do this before the outbreak and have not started | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8. Smoking cigarettes | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 99 |

| 9. Drinking alcohol | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 99 |

| 10. Illicit drug use (including using prescription drugs in different way than prescribed) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 99 |

| 11. Spending time with family doing fun things | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 99 |