Abstract

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is caused by low levels of the survival of motoneuron (SMN) Protein leading to preferential degeneration of lower motoneurons in the ventral horn of the spinal cord and brain stem. However, the SMN protein is ubiquitously expressed and there is growing evidence of a multisystem phenotype in SMA. Since a loss of SMN function is critical, it is important to decipher the regulatory mechanisms of SMN function starting on the level of the SMN protein itself. Posttranslational modifications (PTMs) of proteins regulate multiple functions and processes, including activity, cellular trafficking, and stability. Several PTM sites have been identified within the SMN sequence. Here, we map the identified SMN PTMs highlighting phosphorylation as a key regulator affecting localization, stability and functions of SMN. Furthermore, we propose SMN phosphorylation as a crucial factor for intracellular interaction and cellular distribution of SMN. We outline the relevance of phosphorylation of the spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) gene product SMN with regard to basic housekeeping functions of SMN impaired in this neurodegenerative disease. Finally, we compare SMA patient mutations with putative and verified phosphorylation sites. Thus, we emphasize the importance of phosphorylation as a cellular modulator in a clinical perspective as a potential additional target for combinatorial SMA treatment strategies.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00018-022-04522-9.

Keywords: Survival of motoneuron (SMN) protein, Spinal muscular atrophy (sMA), Posttranslational modification (PTM), Phosphorylation

Introduction

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is an autosomal-recessive neurodegenerative disease predominantly affecting children. SMA is characterized by proximal muscular atrophy due to progressive loss of α-motoneurons in the ventral horn of the spinal cord and in the brain stem. However, SMA is not a pure motoneuron disease, but rather a multisystem disorder [1–11]. Thereby, neuronal degeneration as well as functional dysregulation of several non-neuronal tissues is triggered by low levels of the ubiquitously expressed Survival of Motoneuron (SMN) protein [12]. Humans harbor two nearly identical SMN genes, SMN1 and SMN2. SMN1 encodes the SMN protein. However, a critical mutation in the SMN2 gene results in pre-mRNA mis-splicing of the vast majority of SMN2 transcripts. As a result, the SMN2 gene produces only a low amount of functional full-length SMN protein as compared to the SMN1 gene. In SMA, the SMN1 gene is homozygously deleted or mutated and the remaining amount of fully functional SMN protein expressed by the SMN2 gene is not capable to rescue the SMN1 gene expression loss, and typical SMA phenotypes are observed [12, 13]. However, clinical representations of SMA cover a range of severity, correlating with the copy number variations (CNVs) of the SMN2 gene and the expected SMN protein level [14–16]. Therefore, up to five clinical subtypes were classified based on the age of onset, motor milestones achieved during development, lethality, and CNV of the SMN2 gene. SMA type 0 with prenatal onset and SMA type I with onset before 6 months of age are the most severe forms manifesting in severe muscle impairment, nearly no movement control and symmetrical flaccid paralysis leading in most cases to aspiration pneumonia. Patients typically carry one or two SMN2 gene copies [17, 18]. The intermediate SMA type II is characterized by onset between 7 and 18 months and patients normally harbor three SMN2 gene copies [19]. Clinically, SMA type II manifests in a broad spectrum of symptoms ranging from severe respiratory restrictions to nearly no respiratory failure [20]. SMA type III and IV are less severe forms and patients have three or more SMN2 gene copies. Despite mild muscle weakness patients develop normally with an unchanged life expectancy [17, 19–21].

Increasing the expression of the SMN protein has been a successful therapeutic strategy for SMA. The antisense oligonucleotide Nusinersen has become the first approved medication for SMA patients in 2016 by the FDA, and by the EMA in 2017. Nusinersen regulates SMN2 pre-mRNA splicing; thereby, increasing full-length mRNA [22]. Similarly, the small molecule Risdiplam corrects SMN2 splicing and for both treatments higher copy numbers of SMN2 are beneficial [23–25]. Risdiplam was approved in 2020 by the FDA and in 2021 by the EMA. The scAAV9-based SMN1 gene replacement therapy with Onasemnogene abeparvovec [26–28] was approved by the FDA in 2019 and by the EMA in 2020. Although these are milestones in the treatment of SMA, those drugs still lack full capacity to restore SMN functions in a systemic manner in all types of SMA. In general, drug administration early in postnatal development revealed the best therapeutic outcomes [23–25, 28]. Onasemnogene abeparvovec is an one-time dose of an AAV9 vector comprising the human SMN1 cDNA being independent of the SMN2 copy numbers. A study of two patients, who had received intravenous administration of Onasmnogene abeparvovec revealed broad distribution of the vector genome in peripheral organs and in the central nervous system [29]. The broad distribution of the viral genome leads as well to, at least in parts, rescue of SMN protein levels in peripheral organs as well as in the CNS and especially motoneurons [29]. However, the efficacy of this drug depends on the abundance of the viral DNA which is stored in extrachromosomal episomes and not replicated during cell division. The episomal SMN1 cDNA dilutes in proliferating cells. Taken together, the available therapeutic options are a game changer for SMA patients with regard to their life expectancy and quality of life. However, all therapeutics do have the discussed limitations, which requires to address those by additional approaches for maintaining and restoring SMN functions. Available treatment options focus on restoring SMN protein levels and consequently SMN functions. However, degenerative processes may become SMN irreversible: In this case, disease progression makes it impossible to rescue dysregulated molecular networks and functions just by SMN restoration [29]. To address this problem, combinatorial approaches targeting SMN levels and additionally regulated molecules could be useful. Independently, SMN levels could be enhanced by increasing endogenous SMN stability and selectively improve specific SMN functions. Several studies revealed posttranslational modifications (PTMs), such as phosphorylation of the SMN protein as key regulators for its stability, intracellular localization, and expression. SMN complex formation via self-oligomerization and interaction with other proteins is mediated by phosphorylation [30–32]. Dysregulation of SMN phosphorylation leads to altered intracellular SMN shuttling between the nucleus and cytoplasm as well as SMN stability [33]. Therefore, posttranslational modifications of SMN and their effect on SMN protein stability, localization, and functions can be promising therapeutic targets for novel combinatorial therapies.

Several studies showed that SMN interacts with itself and a variety of different proteins thereby forming the SMN complex and regulating many biochemical pathways [34–44]. The SMN complex is a stable multiprotein complex comprising proteins, including the Gemin2-8 proteins, Unrip, and several Sm proteins [30, 45–47]. Interestingly, functions and interactions of the SMN protein vary depending on its intracellular localization. Intranuclear SMN and its complex have crucial housekeeping functions in the biogenesis and assembly of small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles (snRNPs) [30, 45, 48], pre-mRNA splicing [36] and DNA repair [49, 50]. Furthermore, the SMN protein is involved in the regulation of ribosomes and mRNA processing and encoding [41]. In the cytoplasm, SMN interacts with axonal microtubules being involved in mRNA transport processes along axons and dendrites [51], the actin cytoskeleton [43], and neuronal microfilaments regulating neurite outgrowth [35]. Furthermore, SMN is a key player in maintaining neuromuscular junctions (NMJs) [52] and endocytosis of synaptic vesicles [53]. In SMA, low levels of SMN lead to dysregulation of these biochemical processes, not only in neuronal, but also in non-neuronal tissues in the periphery. Therefore, SMN functions critically depend on its localization and sufficient interaction with other proteins in different cellular compartments.

Here, we review the current literature on PTMs of the SMN protein with an emphasis on phosphorylation. Different domains within the SMN protein mediate the interaction with a plethora of proteins. Moreover, we map the known SMN PTM sites within the domain structure and discuss their functional roles.

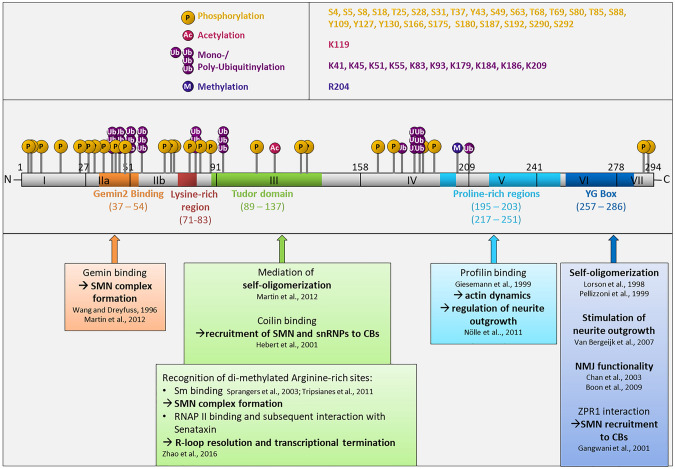

The domain structure of SMN

The SMN1 gene consists of nine exons (1, 2a, 2b, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8) and encodes the full-length SMN protein with 294 amino acid residues. Owing to a gene duplication, humans have the nearly identical SMN2 gene. However, a C to T transition within SMN2 leads to exon 7 skipping, which results in the truncated and rapidly degraded SMNΔ7 isoform [13, 54]. Alternative splicing of the SMN1 pre-mRNA can also lead to the retention of intron 3 and expression of a predicted 18.865 kDa sized axonal-SMN (a-SMN) in motoneurons, liver, and heart [55]. SMN1 as well as SMN2 both encode the additional isoform SMN6B in which an alternative exon 6B is formed due to inclusion of an intronic Alu sequence. However, not much is known about SMN6B functions [56]. Furthermore, specific mutations in SMN2 lead to expression of other truncated isoforms SMNΔ5 and SMNΔ5, 7 [12]. However, none of those isoforms can substitute the ubiquitous expression and diverse functionality of the full-length SMN protein [57]. Full-length SMN comprises three domains highly conserved throughout several species [58] (Fig. 1 and 3, supplemental Fig. 1). SMN harbors a Gemin2-binding domain in close proximity to the N-terminus encoded by exon 2 [45] (Fig. 1). Gemin2 is one of six Gemin proteins interacting with SMN and thereby stabilizing self-oligomerization as well as SMN complex formation [47, 59]. In addition, the highly conserved exon 2 codes for a nucleic acid-binding domain and an interaction site with the tumor suppressor and transcription regulator p53 [34, 60]. The Tudor domain mediates many essential interactions (Fig. 1). This domain recognizes di-methylated arginine residues of Sm proteins [61, 62], which contribute to the SMN complex formation and intranuclear assembly of snRNPs, which are important components of the spliceosome [63]. Some snRNPs, GAR1, fibrillarin, heterogeneous ribonucleoprotein particles (hnRNPs), and the fused in sarcoma (FUS) protein directly interact with the SMN Tudor domain [64–67]. Additional interaction partners include histone H3 [68], the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II [69] and the Cajal body protein coilin [70]—all of which are involved in DNA/RNA processing and protein expression. Interestingly, a member of the fibroblast growth factor family, FGF-223, directly interacts with the SMN protein [71]. The SMN complex functions as a shuttling system between cytoplasm and nucleus for SMN itself and associated factors, such as FGF-223 [48]. A poly-L-proline stretch (PLP) encoded by parts of exons 5 and 6 is conserved in vertebrates and mediates important interactions with the actin cytoskeleton regulatory protein profilin2a [43] (Fig. 1). Interestingly, the F-/G-actin ratio in growth cones of α-motoneurons is increased in SMA cells as compared to controls resulting in growth cone collapse [43]. The highly conserved YG box localizes adjacent to the PLP stretch in exon 6 and close to the C-terminus (Fig. 1). The YG box is characterized by a repeated YxxG amino acid motif, which is crucial for SMN self-oligomerization and SMN complex formation [37]. Furthermore, the C-terminus itself mediates self-oligomerization [72] and regulates SMN protein stability via phosphorylation [33] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The PTM-landscape of SMN. The SMN protein is encoded by 8 exons comprising different conserved domains. The depicted PTM sites are identified by mass spectrometry/proteomics and other methods (see also Table 1). P phosphorylation, Ac acetylation, Ub/UbUbUb mono-/polyubiquitinylation, M methylation

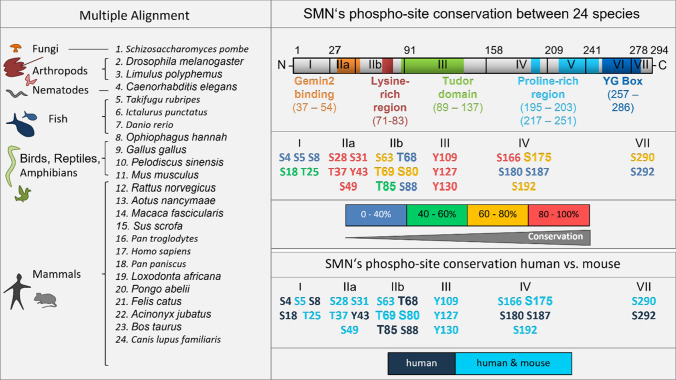

Fig. 3.

Conservation of MS-identified phosphorylation sites of the SMN protein. The multiple alignment of the SMN protein sequences of 24 species including fungi, arthropods, nematodes, fish, birds, reptiles, amphibians and mammals was performed with the freeware CLUSTALW [79]. The conservation of the phosphorylation sites within the 8 encoding exons was further analyzed between the 24 species. The conservation of a phospho-site found in 24 of 24 species (24/24) was set as 100%. For a translational perspective the conservation of SMN phosphorylation sites between human and mouse was additionally determined

The phospho-landscape of SMN

Phosphorylation and—as its counterpart—dephosphorylation are mediated by kinases and phosphatases, respectively. Thus, these enzymes regulate highly dynamic and reversible processes that occur as a fast response to environmental influences [73]. Phosphorylation predominantly occurs at the amino acid residues serine (S), threonine (T), and tyrosine (Y) [74, 75]. In the early 20th century, phosphorylation at a serine residue was identified for the first time in the protein Vitellin [76]. Phospho-serine was denoted as an individual amino acid until the discovery of a phosphate group bound to a serine [77]. In vertebrates, the relative abundance of most common phosphorylated sites (pS: pT: pY) are in the ratio of 1,800: 200: 1 [74]. Of note, the role of phospho-tyrosine (pY) should not be underestimated since tyrosine phosphorylation plays an important role for signaling of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), which are important for neurotrophic factor signaling in neurons and mitogenic signaling in proliferating cells. Thus, they are targeted in cancer treatment [78].

Phosphorylation sites within the SMN sequence have been identified using different approaches and cellular models (Table 1). SMN displays 50 putative phosphorylatable amino acid residues within the SMN primary structure, of which 26 have been identified by mass spectrometry (MS) (Fig. 2; Table 1). Among those, some phosphorylation sites localize within the conserved N-terminal Gemin2-binding domain (S28, S31, T37, Y43, S49) and the central Tudor domain (Y109, Y127, Y130) of SMN [79, 80] (Fig. 3). For instance, phosphorylation at SMN S28 and S31 was found in HeLa cells [30], while pY109, pY127, and pY130 were identified by a screening of several nonsmall cell lung cancer cell lines (NSCLC) [81]. Additional N-terminal phosphorylation sites at SMN S4, S5, S8, T85 and central S187 were found in vitro and further characterized in vivo in protein kinase A (PKA)-overexpressing COS-7 cells [32]. Furthermore, a MS analyses of immunoaffinity-purified SMN complex from HAP1 cells revealed S49 and S63 being phosphorylated [80]. In HeLa cell lysates, the residues S4, S18, T25, T68, T85, S88, and S180 were identified as SMN phosphorylation sites [31]. Since the SMN C-terminus is hardly accessible by tryptic or other enzymatic digestion methods which are essential for MS, the identification of phosphorylation sites has previously been restricted to the N-terminus of SMN. However, we introduced an artificial trypsin target sites which allowed MS analyses and access to the C-terminus for the first time leading to the identification of pS290 and pS292 [33].

Table 1.

Posttranslational modified sites of SMN identified via mass spectrometry

| Exon | Amino acid residue | PTM | Model | Method | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1 | S4 | P | In vitro phosphorylation of recombinant PKA catalytic subunit and GST-SMN; HeLa cells | Purified recombinant GST-SMN constructs in vitro incubation with PKA; LC–MSMS with AB SCIEX 4000 QTRAP; Immunopurification of SMN complex, LC–MS with LTQ Orbitrap | [31, 32] |

| E1 | S5 | P | In vitro phosphorylation of recombinant PKA catalytic subunit and GST-SMN | Purified recombinant GST-SMN constructs in vitro incubation with PKA; LC–MSMS with AB SCIEX 4000 QTRAP | [32] |

| E1 | S8 | P | In vitro phosphorylation of recombinant PKA catalytic subunit and GST-SMN | Purified recombinant GST-SMN constructs in vitro incubation with PKA; LC–MSMS with AB SCIEX 4000 QTRAP | [32] |

| E1 | S18 | P | HeLa cells | Immunopurification of SMN complex, LC–MS with LTQ Orbitrap | [31] |

| E1 | T25 | P | HeLa cells | Immunopurification of SMN complex, LC–MS with LTQ Orbitrap | [31] |

| E1 | S28 | P | HeLa cells | Immunoaffinity of SMN with MALDI-TOF with Q-TOF | [30] |

| E1 | S31 | P | HeLa cells | Immunoaffinity of SMN with MALDI-TOF with Q-TOF | [30] |

| E2a | T37 | P | Acute myeloid leucemia cell line KG1 |

SCX chromatography, phospho-peptide enrichment, LC–MS using LTQ-Orbitrap hybrid MS with nanoscale capillary LC |

[82, 83] |

| E2a | K41 | Ub | HeLa cells; HEK293T cells; Hep2 and Jurkat cells; HCT116 and HEK293T; MV4-11 cells and HEK293T cells |

Mass spectrometry on a nanoscale HPLC system with a hybrid LTQ-Orbitrap Velos; Mass spectrometry of Usp9x-interacting Proteins in a nanoscale reverse phase liquid chromatography coupled with an LTQ Orbitrap Velos mass spectrometer; LC–MS/MS using an EASY nLC1000 connected to a Q Exactive HF mass spectrometer; Antibody-based capture of endogenous diGly-containing peptides and MS; hybrid linear ion-trap/Orbitrap mass spectrometer (LTQ-Orbitrap Velos) |

[84–88] |

| E2a | Y43 | P | Jurkat cells | p-Tyr enrichment, LC–MS | [82] |

| E2a | K45 | Ub | Hep2 and Jurkat cells | LC–MS/MS using an EASY nLC1000 connected to a Q Exactive HF mass spectrometer | [88] |

| E2a | S49 | P | WT and RPS6KB1 knockout human HAP cells | LC–MS/MS using a Q-Exactive HF mass spectrometer equipped with an Easy nLC-1000 UPLC system | [80] |

| E2a | K51 | Ub | MV4-11 cells and HEK293T; Hep2 and Jurkat cells | hybrid linear ion-trap/Orbitrap mass spectrometer (LTQ-Orbitrap Velos); LC–MS/MS using an EASY nLC1000 connected to a Q Exactive HF mass spectrometer | [86, 88] |

| E2b | K55 | Ub | Hep2 and Jurkat cells | LC–MS/MS using an EASY nLC1000 connected to a Q Exactive HF mass spectrometer | [88] |

| E2b | S63 | P | WT and RPS6KB1 knockout human HAP cells; HeLa S3 cells | LC–MS/MS using a Q-Exactive HF mass spectrometer equipped with an Easy nLC-1000 UPLC system; p-Tyr enrichment, reverse phase chromatography, Q Exactive instrument, LC–MS with Orbitrap | [80] [82, 89] |

| E2b | T68 | P | HeLa cells | Immunopurification of SMN complex, LC–MS with LTQ Orbitrap | [31] |

| E2b | T69 | P | Odense-3 and HUES9 hESC lines | SCX chromatography, nanoscale C18-HPLC, LTQ-FT Ultra, LTQ-Orbitrap or LTQ-Orbitrap XL | [82, 90] |

| E2b | S80 | P | M059K cells | p-Ser/Thre enrichment, stable isotope labeling (SILAC), LC–MS | [82] |

| E2b | K83 | Ub | Hep2 and Jurkat cells | LC–MS/MS using an EASY nLC1000 connected to a Q Exactive HF mass spectrometer | [88] |

| E2b | T85 | P | In vitro phosphorylation of recombinant PKA catalytic subunit and GST-SMN; HeLa cells | Purified recombinant GST-SMN constructs in vitro incubation with PKA; LC–MSMS with AB SCIEX 4000 QTRAP; Immunopurification of SMN complex, LC–MS with LTQ Orbitrap | [31, 32] |

| E2b | S88 | P | HeLa cells | Immunopurification of SMN complex, LC–MS with LTQ Orbitrap | [31] |

| E3 | K93 | Ub | HeLa cells; HEK293T cells; Hep2 and Jurkat cells | Mass spectrometry on a nanoscale HPLC system with a hybrid LTQ-Orbitrap Velos; Mass spectrometry of Usp9x-interacting Proteins in a nanoscale reverse phase liquid chromatography coupled with an LTQ Orbitrap Velos mass spectrometer; LC–MS/MS using an EASY nLC1000 connected to a Q Exactive HF mass spectrometer | [84, 87, 88] |

| E3 | Y109 | P | Non-small cell lung cancer cell line (NSCLC) survey | Immunopurification of phospho-peptides and LC–MSMS | [81] |

| E3 | K119 | Ac | HEK293T cells | ICC with anti-acetyl lysine antibody of mutated K119R vs wildtype SMN protein | [91] |

| E3 | K119 | SUMO | UR61, HEK293T and MCF7 cells | Immunoprecipitation of a K119R mutant expressed in cells, SUMo detection via antibodies | [92] |

| E3 | Y127 | P | Non-small cell lung cancer cell line (NSCLC) survey | Immunopurification of phospho-peptides and LC–MSMS | [81] |

| E3 | Y130 | P | Non-small cell lung cancer cell line (NSCLC) survey | Immunopurification of phospho-peptides and LC–MSMS | [81] |

| E3 | S143* | – | – | – | N.A. |

| E4 | S166 | P | 105 breast cancer tissues | Peptide fractionation, phosphopeptide enrichment, isobaric peptide labeling (iTRAQ) MS/MS | [82, 93] |

| E4 | S175 | P | Human breast cancer cell lines MCF-7 and BT474 | Cytosolic and nuclear extraction, LC–MS/MS using an Ultimate 3000 nano-RSLC, LTQ-Orbitrap ELITE MS | [82, 94] |

| E4 | K179 | Ub | Hep2 and Jurkat cells | LC–MS/MS using an EASY nLC1000 connected to a Q Exactive HF mass spectrometer | [88] |

| E4 | S180 | P | HeLa cells | Immunopurification of SMN complex, LC–MS with LTQ Orbitrap | [31] |

| E4 | K184 | Ub | Hep2 and Jurkat cells | LC–MS/MS using an EASY nLC1000 connected to a Q Exactive HF mass spectrometer | [88] |

| E4 | K186 | Ub | MV4-11 and HEK293T cells; Hep2 and Jurkat cells | hybrid linear ion-trap/Orbitrap mass spectrometer (LTQ-Orbitrap Velos); LC–MS/MS using an EASY nLC1000 connected to a Q Exactive HF mass spectrometer | [86, 88] |

| E4 | S187 | P | In vitro phosphorylation of recombinant PKA catalytic subunit and GST-SMN | Purified recombinant GST-SMN constructs in vitro incubation with PKA; LC–MSMS with AB SCIEX 4000 QTRAP | [32] |

| E4 | S192 | P | HeLa cells | Kinase-inhibitor treatment, p-Tyr enrichment, SCX chromatography, nanoscale microcapillary LC–MS/MS, LTQ-Orbitrap | [82, 95] |

| E4 | R204 | Met | HCT116 | Immunoaffinity and mass spectrometry analysis | [96] |

| E4 | K209 | Ub | U2OS cells; Hep2 and Jurkat cells | Hybrid linear ion-trap Orbitrap (LTQ-Orbitrap Velos) or quadrupole Orbitrap (Q-Exactive) MS; LC–MS/MS using an EASY nLC1000 connected to a Q Exactive HF mass spectrometer | [97, 88] |

| E6 | S230* | – | – | – | N.A. |

| E6 | S262* | – | – | – | N.A. |

| E6 | S266* | – | – | – | N.A. |

| E6 | S270 Δ | – | – | – | N.A. |

| E6 | Y272* | – | – | – | N.A. |

| E6 | T274* | – | – | – | N.A. |

| E6 | Y277* | – | – | – | N.A. |

| E7 | S290 | P | NSC34 cells | hSMN construct expression in NSC34 cells, immunopurification, LC–MSMS with Orbitrap Q Excative Plus | [33] |

| E7 | S292 | P | NSC34 cells | hSMN construct expression in NSC34 cells, immunopurification, LC–MSMS with Orbitrap Q Excative Plus | [33] |

The PTMs of SMN are listed with regard to the position within the gene (exon number), protein (number of amino acid residue), the chosen model, the method used for detection, and the corresponding reference. Several PTMs were checked for high-throughput studies using mass spectrometry for proteomics and are listed according to PhosphoSitePlus [82]. For some identified PTMs of the SMN protein we have selected a few references. In those cases, we excuse that we could not include all relevant references due to space limitations

Ac acetylation, Met methylation, P phosphorylation, SUMO SUMOylation, Ub Ubiquitinylation, N.A. not available

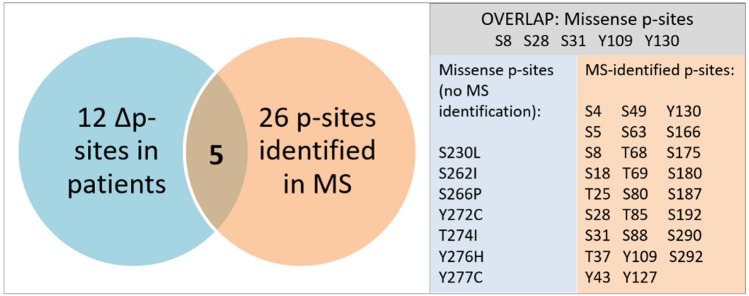

Fig. 2.

Altered phosphorylation of the SMN protein in SMA patients. To date, there are 26 phosphorylation sites within the SMN protein sequence, which have been identified by mass spectrometry. To our knowledge, 12 point mutations of SMN found in SMA patients are putative phosphorylation sites. Only 5 of these known SMA patient mutations are also identified as phosphorylation sites. The residual 7 point mutations remain putative phosphorylation sites within the SMN protein

Approximately 95% of SMA patients harbor a homozygous deletion of the SMN1 gene, whereas 5% of SMA patients show a heterozygous deletion of SMN1 also carrying point mutations (silent, nonsense or missense) on the second allele [98]. Depending on type and localization of the point mutations within the protein sequence, the mutated SMN is either fully functional, impaired or completely dysfunctional [99, 100]. 24 out of 50 phosphorylatable sites in the SMN sequence are putative phosphorylated residues (Fig. 2). Among those putative phospho-sites, there are 3 serine, 1 threonine and 3 tyrosine residues, which are also known to be point-mutated in some SMA patients (Table 2, designated with an asterisk, *). In total, SMN displays 12 patient mutations which are either confirmed phospho-sites (5 residues) or putative ones (7 residues, see above) (Fig. 2; Table 2). However, it is currently unclear whether altered phosphorylation or another functional change of those 5 mutated phospho-sites are linked to SMA phenotypes. Although SMN is ubiquitously expressed, SMN possesses both organism-universal (noncell type specificity) and tissue-characteristic functions (cell type specificity). Consequently, we hypothesize that the phosphorylation pattern of SMN could be at least partly cell type-specific. Kinases and phosphatases both modify the phospho-landscape and are present in different tissue-specific isoforms thereby perfectly adapted to the cellular environment. Aberrant protein phosphorylation is known to be involved in a plethora of diseases e.g., cancer [101, 102], inflammatory autoimmune diseases [103], diabetes [104], and neurodegeneration [105]. Although cell-specific phosphorylation of SMN has not been analyzed in a comparative approach, the phosphorylation pattern of Profilin2a, an SMN-binding protein, has been analyzed in SMA, which is hyperphosphorylated in SMA compared to healthy conditions [106]. With regard to point mutations in SMN, there is evidence that distinct mild SMN1 missense mutations are functional in the presence of SMN2 copies producing full-length SMN [107] and mutations within SMN2 may affect the SMA phenotype [108]. One SMA patient harbored a nucleotide exchange in exon 2a (c.84C > T) in one SMN1 allele leading to the silent point mutation p.Ser28Ser [109]. However, this SMA patient showed an additional intragenic mutation (17895 T > C) within intron 4 of SMN1 [109]. Frameshifts resulting in premature stop codons lead to truncated and dysfunctional SMN [100]. A SMA type II patient displayed the SMN1 missense mutation S230L (c.689C > T) with two SMN2 gene copies [43]. S230 is close to one poly-L-proline stretch (210–224) that mediates profilin2a binding [43]. The missense mutation S230L revealed impaired interaction with profilin2a and led to dysregulated actin dynamics highlighting the importance of actin in SMA pathophysiology [43]. The putative phospho-site S270 was identified as a phospho-degron, which is recognized by Slmb/B-TrCP as part of the degron motif DpSGXXpS/T [110] (Table 1, designated with a triangle, Δ). This degron is required for the binding of the ubiquitin ligase E3 initiating proteasomal degradation [110]. However, mutation of the phospho-degron S270 to the nonphospho mutant S270A resulted in stabilization of the SMNΔ7 protein [110]. In most severe type I SMA patients, point mutations of the putative phosphorylation sites within the SMN YG box (S262I, Y272C, T274I) have been identified [99]. About 20% of SMA type I patients with a point mutation display the mutation Y272C [99]. SnRNP association failed due to impaired Sm protein binding when SMN was mutated within the YG box (Y272C) as found in SMA patients [111].

Table 2.

SMN point mutations of phospho-sites in SMA patients

| #Exon | Mutation of SMN protein | Type of mutation | Nucleotide change | #SMN2 copies | SMA Type | Patient mutant reference | Reference for MS identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1 | p.Ser8Lysfs*23 | Frame shift | c.22dupA |

N.A 2 |

I/II + I | [109, 112–114] | S8 [32] |

| E2a | p.Ser28Ser | Silence | c.84C > T | 1 SMN1, 3 SMN2 | N.A. | [109] | S28 [30] |

| E2a | p.Ser31Phe* | Frame shift | 124insT | 1 SMN1, 2 SMN2 | II | [100] | S31 [30] |

| E3 | p.Tyr109Cys | Missense | c.326A > G | 3 | III | [114] | [81] |

| E3 |

p.Tyr130Cys p.Tyr130His and Tyr130Cys |

Missense | c.389A > G |

N.A. Y > C:1 Y > H:2 |

III III | [115, 116] | [81] |

| E3 | p.Ser143Phefs*5 | Frame shift | c.427dupT | 1 SMN1, 3 SMN2 | N.A. | [117] | N.A. |

| E5 | p.Ser230Leu | Missense | c.689C > T | 2 | II/II + III | [43, 113, 114] | N.A. |

| E6 |

p.Ser262Ile p.Ser262Gly |

Missense Missense |

c.785G > T c.784A > G |

1/1 | III | [12, 100, 118, 119] | N.A. |

| E6 | p.Ser266Pro | Missense | c.796 T > C | N.A | [116] | N.A. | |

| E6 |

p.Tyr272Cys p.Tyr272Trpfs*35 |

Missense Frame shift |

c.815A > G c.811_814 dupGGCT |

2 1 SMN1, 2–3 SMN2, 1–2 |

I/II/III | [12, 98, 100, 114, 119–121] | N.A. |

| E6 | p.Thr274Ile | Missense | c.821C > T | 1 SMN1,1–2 SMN2 | II/III | [98, 100, 118, 119, 122] | N.A. |

| E6 | p.Tyr276His | Missense | c.826 T > C | 1 SMN1, 3 SMN2 | N.A. | [117] | N.A. |

| E6 | p.Tyr277Cys | Missense | c.830A > G | 2 | II/III | [113, 114] | N.A. |

We have selected a few references for specific sites. In those cases, we apologize that we could not include all relevant references due to space limitations

Functions of SMN regulated by phosphorylation

SMN is ubiquitously expressed and interacts with numerous proteins by its conserved binding domains [58] (Fig. 1; Table 1). The protein–protein interactions as well as the localization of SMN are regulated by dynamic posttranslational modifications such as phosphorylation. In some cases, the intracellular localization of SMN and its associated function in different cellular compartments rely on SMN interactions with other protein. Here, we review the current knowledge about the phosphorylation in a functional context.

Spliceosome biogenesis and intracellular shuttling

The N-terminus of SMN comprises the Gemin2-binding domain essential for SMN complex formation [37, 38] and pre-mRNA maturation [67, 123, 124]. The SMN complex includes several proteins including SMN, Gemin2-8, and Unrip, which assemble in the cytoplasm. The association of the SMN complex with snRNPs comprising snRNA and Sm proteins is a crucial step in spliceosome formation [48]. The Sm proteins comprise arginine/glycine (RG)-rich motifs with di-methylated arginine residues, which are recognized by the Tudor domain of SMN [61, 62]. SMN binds to the ring-shape arrangement of Sm proteins to assemble snRNPs for maturation of pre-mRNA [63]. In the nucleus, the SMN complex localizes to intranuclear structures, namely Cajal bodies (CB) and gems (Gemini of Cajal bodies) [124, 125]. Gems are SMN-positive nuclear bodies (NB) which functions have not been completely elucidated yet [125–127]. Coilin is a characteristic marker for CBs [128], which binds to the C-terminal part of the Tudor domain of SMN recruiting SMN and snRNPs to the CB [70].

The translocation of the SMN complex between cytoplasm and nucleus is regulated by phosphorylation. Cytoplasmic SMN is hyper-phosphorylated whereas nuclear SMN is hypo-phosphorylated in HeLa cells [30]. The serine residues S28 and S31 are phosphorylated for SMN complex assembly while the SMN complex is instable when dephosphorylated by alkaline phosphatase [30]. Hence, hyper-phosphorylation affects the intracellular distribution of the SMN complex and increases its activity while hypo-phosphorylation leads to an unstable SMN complex [30]. Therefore, distinct SMN phosphorylation sites are involved in SMN complex formation and intracellular distribution of the complex and SMN itself. Accordingly, mutagenesis of phosphorylation sites S, T, and Y to nonpolar alanine (A) or polar aspartate (D) mimic either no phosphorylation or a phosphorylated state at the specific positions [31]. The nonphospho mutants of SMN S4, S5, S8, S18, T25, S28, S31, T62, T68, T85, and S88 revealed a reduced binding to coilin and impaired binding to Gemin2 and 8 [31]. In addition, nonphospho mutants of S28 and S31 also showed impaired intracellular localization of the SMN complex [31]. Individual mutations of the serines S4, S5, S8, and S187 and T85 to nonphospho mutants results in altered binding of SMN to Gemin2 and 8 leading to impaired SMN complex assembly [32]. Furthermore, recent work demonstrated SMN phosphorylation on serines S49 and S63 being crucial for CB-associated condensation of the SMN protein [80]. The S49 phosphorylation is mediated directly by active TOR signaling and interaction of SMN with the ribosomal protein S6 kinase β-1 [80]. These findings suggest SMN phosphorylation as a platform for the mediation or priming for protein interactions e.g., within the SMN complex, but could also modulate the intracellular shuttling of SMN.

Oligomerization

The SMN protein forms an oligomeric core within the SMN complex required for snRNP assembly [129, 130]. The Tudor domain of SMN mediates its self-oligomerization [37, 131]. In addition, the conserved YG box [37, 111] and the C-terminus also contribute to the SMN self-oligomerization [72] (Fig. 1). According to the function of the YG box, the SMA patient missense mutation Y272C leads to impaired self-oligomerization of SMN [34, 111]. Mutations found in type II (S262I) and III (T274I) SMA patients revealed intermediate ability for SMN self-association [72]. However, the N-terminal nonphospho mutants S28A and S31A as well as their corresponding phospho-mimetics S28D and S31D oligomerized with endogenous SMN [31]. The C-terminal phospho-mimetic S290D showed impaired oligomerization with endogenous SMN in motoneuron-like NSC34 cells [33]. In contrast, nonphospho mutant S290A as well as wildtype SMN displayed no effect on self-oligomerization [33]. Taken together, the phosphorylation at the SMN N-terminus showed no impact on self-oligomerization whereas C-terminal phosphorylation close to the YG box affects the self-oligomerization capability. Of note, the residues S262, Y272, and T274 within the YG box and known as SMA patient mutation sites remain as putative phosphorylation sites of SMN.

SMN and its interaction with ZPR1

In mammals, the Zinc finger protein 1 (ZPR1) is ubiquitously expressed and plays a central role in receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) signaling pathways mediating cell proliferation, growth and viability [50, 132–135]. ZPR1 binds the cytoplasmic domain of the RTK epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) [132, 136]. The C-terminus of SMN interacts with the C-terminal region of ZPR1, which guides SMN from the cytoplasm to nuclear bodies during serum-induced stimulation in COS-7 cells [137]. SMA type I patient-derived fibroblasts show impaired binding of ZPR1 to the SMN complex [137]. In HEK293T cells, the SMN C-terminal phospho-mimetic S290D displayed impaired interaction with ZPR1 as compared to wildtype SMN and its corresponding nonphospho mutant S290A [33]. In line with that immunocytochemistry revealed less co-localization of ZPR1 with the phospho-mimetic S290D [33]. These results imply that the essential SMN:ZPR1 interaction and co-localization may be impaired due to phosphorylation at the ZPR1-binding site in the C-terminus of SMN. Phosphorylation at S290 may mediate ZPR1-binding to SMN or may even constitute a binding platform for ZPR1. In addition, SMA patient-derived lymphoblastoid cells revealed a reduced ZPR1 expression [138]. Accordingly, ZPR1 depletion leads to neurodegeneration mediated by c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway and increases the severity of SMA in mice [139]. Apart from SMN mutations, other factors may also contribute to the severity of the cellular SMA phenotype: protein interactions, the underlying SMN functions, the ZPR1 depletion, and the impaired SMN:ZPR1 interaction due to the altered phosphorylation state of SMN.

Stability of SMN

The protein turnover of SMN is mediated by the ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS, see below) [140]. In SMA patients, the truncated SMNΔ7 protein is faster degraded than the full-length SMN wildtype [140]. Several mechanisms affect the protein stability of SMN: (i) the capability of self-oligomerization ([72, 111] see above), (ii) the protein interactions e.g., SMN complex formation [140] and (iii) the posttranslational modifications of SMN [33]. Precisely, the phosphorylation of SMN may act as regulator for priming the protein for a change in stability. For instance, formation of the SMN complex comprising the binding of Gemin3, -5, and -6 leads to an increased SMN stability [140]. However, SMN binding to Gemin2 and -8 is increased when PKA-mediated phosphorylation is prevented in COS-7 cells [32]. In NSC34 cells, the SMN phospho-mimetic S290D revealed a remarkably decrease in the protein stability [33]. The half life of S290D was further reduced confirming the low protein expression in comparison to SMN wildtype and the corresponding nonphospho mutant S290A [33]. As a consequence of decreased SMN protein stability, the number of SMN-positive nuclear bodies was reduced [33, 141]. These results underline the importance of SMN phosphorylation for protein stability which may affect crucial SMN downstream functions, such as SMN complex formation, and localization to nuclear bodies.

Erasing the modification: the role of phosphatases acting on SMN

Kinase-mediated phosphorylation of proteins plays a crucial role for numerous signaling pathways within cells. The functions of the dynamic posttranslational modifications are diverse including activation or inhibition of enzymes, induction of intracellular translocation, triggering or preventing downstream pathways of the kinase target, protein − protein interactions or mediation of transcription and translation. Although there is substantial data on the phosphorylation state of SMN, less is known about the involved phosphatases.

Protein phosphatase 4 (PPP4) (indirect interaction)

PPP4 is ubiquitously expressed in higher eukaryotes and dephosphorylates serine or threonine residues [142]. This phosphatase builds a 450–600 kDa complex, which mainly localizes to the nucleus [143] and comprises two regulatory subunits R1 [144], adjacent to the well conserved catalytic subunit PP4c [145], and the core regulatory subunit R2 [146]. R2-PP4c promotes snRNP maturation together with SMN being part of the SMN complex [143]. In HeLa cells, co-immunoprecipitation of R2-PP4c revealed interactions with the four SMN complex components SMN and Gemins 2–4 [143]. Since the regulatory R2-PP4c subunit binds to SMN, it is likely that PPP4 dephosphorylates SMN.

Protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) (indirect interaction via Gemin8)

The protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) is a major mammalian serine/threonine phosphatase encoded by three genes [147]. The isoforms PP1 α, β/δ and γ are differentially expressed in mammalian tissues and acquire their target specificity by complex formation in a myriad of holoenzymes [148]. Those specific PP1 regulators determine the impact of dephosphorylation on cellular processes, which range from cell proliferation [149], glycogen biogenesis [150], muscle contraction to neuronal functions such as synaptic plasticity [151, 152]. In HeLa cells, protein phosphatase 1γ (PP1γ) was identified as a phosphatase of SMN [153]. A knockdown of PP1γ resulted in an increased accumulation of the SMN complex and snRNPs in CBs [153]. As a consequence, hyper-phosphorylation of SMN was observed in PP1γ-depleted HeLa cells. PP1γ overexpression corrected the SMN phosphorylation state. In co-immunoprecipitation assays, Gemin8 as part of the SMN complex could be isolated together with PP1γ indicating an indirect interaction [153]. These findings suggest that reduced PP1γ activity results in a hyper-phosphorylated state of the SMN complex with a subsequent co-localization of SMN and snRNPs in CBs.

PPM1G/PP2Cγ, PTPN23 and the case of PTEN (direct interaction)

The nuclear protein phosphatase magnesium-dependent 1 gamma (PPM1G) is a member of the protein phosphatase 2c (PP2C) family regulating cell growth and inhibiting cellular stress [154, 155]. PPM1G is recruited by and interacts with NF-κB in order to modulate transcription elongation after DNA damage [155–158]. In addition, PPM1G is also involved in snRNP assembly and pre-mRNA splicing [155–158]. Hence, the dephosphorylation of SMN by nuclear PPM1G/PP2Cγ leads to stabilized localization of SMN in CBs in HeLa cells [158]. Since PPM1G/PP2Cγ interact with several components of the SMN complex, namely phospho-protein Gemin3 and Unrip, PPM1G/PP2Cγ may also regulate the formation of the SMN complex and its localization to CBs [158].

The tyrosine protein phosphatase nonreceptor type 23 (PTPN23) is a putative tumor suppressor gene which encodes the His-domain comprising protein tyrosine phosphatase (HD-PTP) [159, 160]. Loss of PTPN23 results in abnormal accumulation of ubiquitinylated proteins in endosomes which disrupts endocytic trafficking [161]. PTPN23 is expressed in the central nervous system (CNS) in the cerebral cortex, thalamus and hypothalamus of adult mice and a PTPN23−/− knockout results in embryonic lethality [162]. The Drosophila melanogaster PTPN23 orthologue myopic was identified as a regulator of CNS development [163]. In humans, mutations within the PTPN23 gene causes defective development of the nervous system underlining the importance of PTPN23 for neuronal function [164]. The knockdown of PTPN23 in HeLa cells leads to a reduced number of SMN-positive CBs [141]. Taken together, dephosphorylation of specific sites of SMN by PTPN23 results in accumulation of SMN in CBs.

The phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN) is known as the inhibitor of the phosphoinositide 3 kinase (PI3K) pathway resulting in decreased cell proliferation and cell survival [165, 166]. PTEN dephosphorylates phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3) to phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-bisphosphate (PIP2) [165–167]. Recently, PTEN has been identified as a phosphatase of SMN and as a regulator of SMN stability [33]. PTEN binds to SMN at its C-terminal region in a region comprising residues 239–278 [33]. The adjacent C-terminal serine S290 of SMN is phosphorylated in differentiated motoneuron-like NSC34 cells and modulates PTEN binding [33]. Pharmacological inhibition of PTEN causes reduced SMN stability [33]. In addition, PTEN knockdown in NSC34 cells resulted in a decreased SMN protein level and a reduced number of SMN-positive nuclear bodies [33], of which the latter is a typical hallmark observed in SMA patient cells [168]. PTEN depletion also shows prolonged cell survival of murine fibroblasts possibly mediated by AKT signaling [166] and SMNΔ7 SMA mice showed increased survival and less motoneuron degeneration [169]. However, SMN levels have not been accessed in those studies.

Overall, the here-mentioned kinases PKA, RPS6K1 and phosphatases PPP4, PP1, PPM1G/PP2Cγ and PTPN23, PTEN known to be involved in modulating SMN phosphorylation and the SMN function being connected to this enzyme–SMN interaction are listed in Table 3. Several in silico prediction tools were used identifying putative phosphorylation sites and kinases in the SMN protein e.g., NetPhos 3.1, KinasePhos 2.0 and GPS 5.0 [170–173]. Interestingly, only the PKA was both predicted in silico and confirmed to phosphorylate SMN at the phosphorylation site T85. Other in silico predicted phosphorylation sites remain putative sites for PKA (Table 3). To our knowledge, there are currently no available tools addressing in silico prediction of phosphatases and their substrates. Of note, at least the region of PTEN binding was identified within the SMN protein [33], however, the amino acid residue PTEN dephosphorylates remains to be determined (Table 3).

Table 3.

Confirmed and predicted in silico kinases and phosphatases modulating the SMN phosphorylation landscape

| Kinase/Phosphatase | Confirmed or in silico interaction | SMN p-sites or sequence | SMN function | Source/Paper |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein kinase A (PKA) | Confirmed | S4, S5, S8, T85, S187 | Binding to Gemin 2 and 8, SMN complex assembly | [32] |

| Protein kinase A (PKA) | In silico prediction | T25*,+,++, T122*,#, S290*,++, S292*, S28# and T85# | *NetPhos 3.1 [170, 171]; #KinasePhos 2.0, HMM bit score [172]; +GPS 5.0, high threshold, ++GPS 5.0, medium threshold [173] | |

| Ribosomal protein S6 kinase beta-1 | N.A. | S49 | [80] | |

| Protein-phosphatase 4 (PPP4) (indirect) | Confirmed | N.A. | snRNP maturation | [143] |

| Protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) (indirect) | Confirmed | N.A. | SMN co-localization with snRNPs in CBs | [153] |

| PPM1G/PP2Cy | Confirmed | N.A. | Stabilized localization of SMN in CBs | [158] |

| PTPN23 | Confirmed | N.A. | Accumulation of SMN in CBs | [141] |

| PTEN | Confirmed | G239-M278 | Binding of PTEN; SMN stability, number of SMN-positive nuclear bodies | [33] |

In conclusion, a hypo-phosphorylated state of specific sites induced by either phosphatases PTEN, PPM1G/PP2Cγ or PTPN23 favors accumulation of SMN in NBs, while hyper-phosphorylation by knockdown of phosphatase PP1γ also results in accumulation of SMN complex and snRNPs in CBs. These findings strongly support a specific phosphorylation pattern of SMN with dephosphorylated sites as well as phosphorylated sites acting together to stimulate translocation within the cell. The phosphorylation state of SMN may change within different cellular compartments in order to fulfill the compartment-specific functions of SMN. However, the connection between the SMA pathomechanisms and altered phosphorylation states of SMN needs to be further elucidated.

Other posttranslational modifications of SMN

Apart from phosphorylation, less is known about other posttranslational modifications (PTMs) of the SMN protein. Since SMN is ubiquitously expressed and involved in a broad range of diverse biological processes, the protein is likely to be modified at several domains. These highly modifiable regions are accessible by enzymes or interaction partners. PTMs of these protein regions can induce significant changes in structural and, therefore, interaction properties [174]. Besides PTMs mediating interactions of proteins, protein turnover rates are determined by covalent attachment of small signal molecules e.g., ubiquitinylation for protein degradation via the ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS) [175]. Regarding SMN, several PTMs have been identified being relevant for the coilin interaction or other CB-typical proteins for assembly in CBs [176]. Here, we will briefly summarize PTMs other than phosphorylation of the SMN protein and their consequences with the focus on protein functions, interactions and degradation.

Ubiquitinylation

SMN degradation by the UPS has been described in several studies [140, 177, 178] including identification of SMN Ub-sites in proteomics. Nonetheless, other functional consequences of these lysine residue modifications are mostly unknown. SMN comprises 22 lysine residues as putative targets for ubiquitinylation (Fig. 1). 10 of those lysines (K41, 45, 51, 55, 83, 93, 179, 184, 186 and 209) have been found to be ubiquitinylated [84–88, 97]. However, only few E3-Ub ligases deubiquitinylating enzymes or Ub modifiers mediating the Ub modifications of SMN are known. The first SMN Ub ligase identified was the ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCHL1). UCHL1 co-immunoprecipitated with SMN acting as an Ub ligase on the SMN protein and thereby mediating SMN degradation via the UPS. Specific inhibition of UCHL1 rescued SMN protein levels in SMA fibroblasts [179]. Though, inhibition of UCHL1 in a SMA mouse model did not ameliorate, but even exacerbated the SMA phenotype [180]. The SMN ubiquitinylation modifier apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) directly binds SMN thereby inhibiting at least in part the SMN ubiquitinylation. The overexpression of ASK1 consequently increased the SMN protein levels and moderately rescued neurite outgrowth in a SMA cell model [181]. More recently, the E3 Ub-ligase mind bomb 1 (Mib1) was shown to ubiquitinylate the SMN protein. SMN exon 6 is crucial for this interaction, which also enables the interaction of truncated SMNΔ7 with Mib1. Of note, knockdown experiments revealed that Mib1-catalyzed ubiquitinylation leads to degradation of the SMN protein which results in an increased protein turnover [182]. However, monoubiquitinylation of SMN by the E3 Ub-ligase Itch at SMN lysines 179 and 209 has a mild effect on UPS-mediated degradation. In addition, monoubiquitinylation influences the intracellular distribution of SMN between the cytoplasm and nucleus. A SMN mutant defective in ubiquitinylation accumulated predominantly in the nucleus but impaired canonical CB formation. Thus, monoubiquitinylation of SMN may prime SMN for a nuclear export signal [183]. This concept is supported by findings, that SMN deubiquitinylation by the ubiquitin-specific protease 9x (USP9x) occurs mainly in the cytoplasm [87].

SUMOylation

Another very common PTM of SMN is SUMOylation. Modification of proteins with the small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO) is a regulatory switch in many cellular pathways and processes [184]. SMN may be SUMOylated by SUMO1 at a SUMO-interacting motif (SIM)-like domain located within the SMN Tudor domain [92]. SIMs are characterized by a hydrophobic core (V/I-x-V/I-V/I) which serves as a platform for SUMO interaction [185]. In fact, SMN comprises a SIM-like domain (V124-V125-V126) and additionally a SUMO consensus motif (F-K119-R-E) (Fig. 1). Interestingly, experiments with mutations in those sequences did not abrogate SMN SUMOylation, but prevented interactions with coilin and Sm proteins, which are crucial for snRNP processing and CB formation [92, 186]. These results suggest that SMN is SUMOylated at different positions. Since interaction of e.g., profilin2a with SMN is restricted to a specific binding site [43], SUMOylation of SMN may still occur with a distance to the profilin2a-binding site. In conclusion, lysine K119 as well as the SIM-like domain may impact protein interactions of SMN.

Lysine acetylation

Lysine acetylation was first described on histones influencing RNA synthesis via the reorganization of chromatin [187]. Though, lysine acetylation is mainly known to regulate processes involving cell signaling and metabolic pathways [188, 189]. The transcriptional coactivators and large multidomain signaling proteins cyclic AMP-responsive element-binding protein (CBP) and its paralogue p300 both possess intrinsic histone acetyltransferase activities [190, 191] and interact with the SMN protein [91]. SMN is acetylated by CBP and p300 at lysine K119 (Fig. 1). Interestingly, this lysine was proposed to be SUMOylated (see above). K119 localizes within the Tudor domain and is a key element of SMN in the exon 3 responsible for interactions with numerous proteins, e.g. with the Sm proteins and coilin [70, 92, 192]. Acetylation of SMN K119 causes depletion of SMN-positive CBs and SMN accumulation in the cytoplasm. Furthermore, K119 acetylation influences the half life of the SMN protein and reduces its cytoplasmic diffusion rate. In addition, a SMN interactome analysis confirmed SMN interactions with proteins being important for CB functions dependent on K119 acetylation state [91].

Arginine methylation

Protein methylation is known as a regulatory element for a subset of diverse biological processes as for example epigenetic regulation of gene transcription [193], RNA and DNA processing as well as transport processes or DNA damage repair [194]. In a large proteomic study of protein methylation, SMN was found to encompass a monomethylarginine. Methylation occurs on arginine R204 which is found in exon 4 of the SMN protein [96] (Fig. 2). Unfortunately, a functional outcome of this SMN methylation has not been assessed yet. Nevertheless, monomethylation can be a reaction intermediate of protein arginine methyl transferases (PRMTs) suggesting that SMN comprises a dimethylarginine (DMA) [195]. Interestingly, DMAs are preferred molecular targets for protein–protein interactions mediated by Tudor domains. The SMN Tudor domain enables the interaction with methylated Sm proteins [196]. Moreover, since SMN interacts with numerous proteins as well as RNA, this arginine methylation at R204 can be crucial for SMN to enable those interactions.

Outlook and consequences for the therapy of SMA

Spinal Muscular Atrophy is a model disease regarding different aspects: First, it is a monogenic disorder linking the SMN protein to dysregulated cellular homeostasis. This should have led to the identification of clear-cut mechanisms responsible for SMA pathogenesis. However, this is not the case. Recently, several mechanisms have been identified with SMN being a relevant regulator of those. The large interactome of SMN makes it impossible to attribute pathological alterations to one or few mechanisms. Second, three therapies are on the market for this devastating rare disease. Obviously, this is a significant success mechanistically based on the correction of SMN loss by splicing modifiers or gene replacement. However, a significant number of patients does not or respond less well to those treatment approaches. Therefore, there is still potential for improvements and novel combinatorial therapeutic strategies, respectively, addressing molecular networks, which became SMN irreversible, i.e. nonresponsive towards SMN restoration especially at later nonoptimal time points in life [29]. Third, those approaches developed for SMA could be translated to other neurodegenerative and monogenic diseases using SMA as a model for the development of novel strategies.

Elucidating SMN´s protein functions and its role in molecular networks is still a major challenge. Although this review summarizes data about phosphorylation sites, involved kinases and phosphatases, there is still a lack of information about its integration in regulatory phosphorylation-dependent networks. It is currently unclear, which phospho-sites are employed in different cell types and organs to regulate diverse functions of SMN. Moreover, although some of those phospho-sites have been characterized, there is a lack of annotated functions. This is surprising since several of SMN´s physiological functions appear to be regulated by dynamic phosphorylation. In general, this is true for many proteins. However, less of 3% of all phospho-sites have been linked to functional outcomes [197]. At this point, we would like to address two main mechanisms on how phosphorylation affects SMN´s functions to identify future areas and aspects of research: (i) Phosphorylation is used by cells for internal sorting and tethering to cellular compartments. As described in this review, this has primarily elucidated for nuclear–cytoplasmic shuttling. However, motoneurons have large processes (dendrites and axons) and differential sorting and localization could be the result of specific phosphorylation patterns. (ii) Phosphorylation regulates the stability of SMN. As described above, specific sites are responsible for this effect and the concerted activities of kinases and phosphatases provide a secondary level of regulation. The identification of those molecules is definitely a future experimental challenge to understand and influence SMN stability. The current therapies are designed towards upregulation of SMN levels. However, extending half-life times of SMN e.g., by modulating kinases as target molecules could be an additional regulatory strategy to increase SMN levels especially in combinatorial therapies in cases when splicing regulation or gene replacement need to be augmented. Taken together, analyses of the phospho-landscape of SMN provide highly relevant insights into the function and regulation of this key molecule for the pathogenesis of SMA.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 Supplemental Phylogenetic comparison of SMN primary structures from 24 different species. Primary structures of SMN from 24 different species were aligned by Clustal Omega (program clustalo, version 1.2.4) [198] and a phylogenetic tree was generated as a neighbor-joining tree without distance corrections. The alignment was visualized by IcyTree software [199]. (PNG 17 kb)

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Claus group for discussions, and especially Amy Glynn for suggestions on the text. Moreover, we are grateful for funding by the Deutsche Muskelstiftung (SMAPERIPHERAL) and SMA Europe (SMATARGET).

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the preparation, writing, and final approval of the manuscript.

Funding

We are grateful for funding by the Deutsche Muskelstiftung (SMAPERIPHERAL) and SMA Europe (SMATARGET).

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declared no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Nora Tula Detering and Tobias Schüning contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Crawford TO, et al. Abnormal fatty acid metabolism in childhood spinal muscular atrophy. Ann Neurol. 1999;45(3):337–343. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199903)45:3<337::aid-ana9>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wijngaarde CA, et al. Cardiac pathology in spinal muscular atrophy: a systematic review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12(1):67. doi: 10.1186/s13023-017-0613-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nery FC, et al. Impaired kidney structure and function in spinal muscular atrophy. Neurol Genet. 2019;5(5):e353. doi: 10.1212/NXG.0000000000000353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hua Y, et al. Peripheral SMN restoration is essential for long-term rescue of a severe spinal muscular atrophy mouse model. Nature. 2011;478(7367):123–126. doi: 10.1038/nature10485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamilton G, Gillingwater TH. Spinal muscular atrophy: going beyond the motor neuron. Trends Mol Med. 2013;19(1):40–50. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szunyogova E, et al. Survival Motor Neuron (SMN) protein is required for normal mouse liver development. Sci Rep. 2016;6:34635. doi: 10.1038/srep34635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deguise MO, et al. Abnormal fatty acid metabolism is a core component of spinal muscular atrophy. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2019;6(8):1519–1532. doi: 10.1002/acn3.50855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vitte JM, et al. Deletion of murine Smn exon 7 directed to liver leads to severe defect of liver development associated with iron overload. Am J Pathol. 2004;165(5):1731–1741. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63428-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martinez-Hernandez R, et al. The developmental pattern of myotubes in spinal muscular atrophy indicates prenatal delay of muscle maturation. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2009;68(5):474–481. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181a10ea1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allardyce H, et al. Renal pathology in a mouse model of severe Spinal Muscular Atrophy is associated with downregulation of Glial Cell-Line Derived Neurotrophic Factor (GDNF) Hum Mol Genet. 2020;29(14):2365–2378. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddaa126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hensel N, et al. Altered bone development with impaired cartilage formation precedes neuromuscular symptoms in spinal muscular atrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2020;29(16):2662–2673. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddaa145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lefebvre S, et al. Identification and characterization of a spinal muscular atrophy-determining gene. Cell. 1995;80(1):155–165. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90460-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lorson CL, et al. A single nucleotide in the SMN gene regulates splicing and is responsible for spinal muscular atrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(11):6307–6311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monani UR. Spinal muscular atrophy: a deficiency in a ubiquitous protein; a motor neuron-specific disease. Neuron. 2005;48(6):885–896. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lefebvre S, et al. Correlation between severity and SMN protein level in spinal muscular atrophy. Nat Genet. 1997;16(3):265–269. doi: 10.1038/ng0797-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burghes AH, Beattie CE. Spinal muscular atrophy: why do low levels of survival motor neuron protein make motor neurons sick? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(8):597–609. doi: 10.1038/nrn2670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D'Amico A, et al. Spinal muscular atrophy. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2011;6:71. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-6-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dubowitz V. Very severe spinal muscular atrophy (SMA type 0): an expanding clinical phenotype. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 1999;3(2):49–51. doi: 10.1053/ejpn.1999.0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feldkotter M, et al. Quantitative analyses of SMN1 and SMN2 based on real-time lightCycler PCR: fast and highly reliable carrier testing and prediction of severity of spinal muscular atrophy. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70(2):358–368. doi: 10.1086/338627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kolb SJ, Kissel JT. Spinal muscular atrophy. Neurol Clin. 2015;33(4):831–846. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wirth B, et al. Mildly affected patients with spinal muscular atrophy are partially protected by an increased SMN2 copy number. Hum Genet. 2006;119(4):422–428. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ottesen EW. ISS-N1 makes the First FDA-approved drug for spinal muscular atrophy. Transl Neurosci. 2017;8:1–6. doi: 10.1515/tnsci-2017-0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finkel RS, et al. Nusinersen versus Sham control in infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(18):1723–1732. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1702752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mercuri E, et al. Nusinersen versus Sham control in later-onset spinal muscular atrophy. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(7):625–635. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1710504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ratni H, et al. Discovery of risdiplam, a selective survival of motor neuron-2 ( SMN2) gene splicing modifier for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) J Med Chem. 2018;61(15):6501–6517. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyer K, et al. Improving single injection CSF delivery of AAV9-mediated gene therapy for SMA: a dose-response study in mice and nonhuman primates. Mol Ther. 2015;23(3):477–487. doi: 10.1038/mt.2014.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mendell JR, et al. Single-dose gene-replacement therapy for spinal muscular atrophy. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(18):1713–1722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1706198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al-Zaidy S, et al. Health outcomes in spinal muscular atrophy type 1 following AVXS-101 gene replacement therapy. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2019;54(2):179–185. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hensel N, Kubinski S, Claus P. The need for SMN-independent treatments of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) to complement SMN-enhancing drugs. Front Neurol. 2020;11:45. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grimmler M, et al. Phosphorylation regulates the activity of the SMN complex during assembly of spliceosomal U snRNPs. EMBO Rep. 2005;6(1):70–76. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Husedzinovic A, et al. Phosphoregulation of the human SMN complex. Eur J Cell Biol. 2014;93(3):106–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu CY, et al. Identification of the phosphorylation sites in the survival motor neuron protein by protein kinase A. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1814(9):1134–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2011.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rademacher S, et al. A single amino acid residue regulates PTEN-binding and stability of the spinal muscular atrophy protein SMN. Cells. 2020 doi: 10.3390/cells9112405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lorson CL, Androphy EJ. The domain encoded by exon 2 of the survival motor neuron protein mediates nucleic acid binding. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7(8):1269–1275. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.8.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Bergeijk J, et al. The spinal muscular atrophy gene product regulates neurite outgrowth: importance of the C terminus. FASEB J. 2007;21(7):1492–1502. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7136com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pellizzoni L, et al. A novel function for SMN, the spinal muscular atrophy disease gene product, in pre-mRNA splicing. Cell. 1998;95(5):615–624. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81632-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin R, et al. The survival motor neuron protein forms soluble glycine zipper oligomers. Structure. 2012;20(11):1929–1939. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang J, Dreyfuss G. Characterization of functional domains of the SMN protein in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(48):45387–45393. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105059200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fuller HR, et al. The SMN interactome includes Myb-binding protein 1a. J Proteome Res. 2010;9(1):556–563. doi: 10.1021/pr900884g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fuller HR, Gillingwater TH, Wishart TM. Commonality amid diversity: Multi-study proteomic identification of conserved disease mechanisms in spinal muscular atrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2016;26(9):560–569. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2016.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lauria F, et al. SMN-primed ribosomes modulate the translation of transcripts related to spinal muscular atrophy. Nat Cell Biol. 2020;22(10):1239–1251. doi: 10.1038/s41556-020-00577-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wirth B. Spinal muscular atrophy: in the challenge lies a solution. Trends Neurosci. 2021;44(4):306–322. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2020.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nölle A, et al. The spinal muscular atrophy disease protein SMN is linked to the Rho-kinase pathway via profilin. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20(24):4865–4878. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hensel N, Claus P. The actin cytoskeleton in SMA and ALS: how does it contribute to motoneuron degeneration? Neuroscientist. 2018;24(1):54–72. doi: 10.1177/1073858417705059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu Q, et al. The spinal muscular atrophy disease gene product, SMN, and its associated protein SIP1 are in a complex with spliceosomal snRNP proteins. Cell. 1997;90(6):1013–1021. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80367-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gubitz AK, Feng W, Dreyfuss G. The SMN complex. Exp Cell Res. 2004;296(1):51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Feng W, et al. Gemins modulate the expression and activity of the SMN complex. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14(12):1605–1611. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Forthmann B, Grothe C, Claus P. A nuclear odyssey: fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) as a regulator of nuclear homeostasis in the nervous system. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72(9):1651–1662. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1818-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Takizawa Y, et al. GEMIN2 promotes accumulation of RAD51 at double-strand breaks in homologous recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(15):5059–5074. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kannan A, et al. ZPR1 prevents R-loop accumulation, upregulates SMN2 expression and rescues spinal muscular atrophy. Brain. 2020;143(1):69–93. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pagliardini S, et al. Subcellular localization and axonal transport of the survival motor neuron (SMN) protein in the developing rat spinal cord. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9(1):47–56. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kariya S, et al. Reduced SMN protein impairs maturation of the neuromuscular junctions in mouse models of spinal muscular atrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(16):2552–2569. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dimitriadi M, et al. Decreased function of survival motor neuron protein impairs endocytic pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(30):E4377–E4386. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1600015113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lorson CL, Androphy EJ. An exonic enhancer is required for inclusion of an essential exon in the SMA-determining gene SMN. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9(2):259–265. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Setola V, et al. Axonal-SMN (a-SMN), a protein isoform of the survival motor neuron gene, is specifically involved in axonogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(6):1959–1964. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610660104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Seo J, et al. A novel human-specific splice isoform alters the critical C-terminus of survival motor neuron protein. Sci Rep. 2016;6:30778. doi: 10.1038/srep30778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chaytow H, et al. The role of survival motor neuron protein (SMN) in protein homeostasis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2018;75(21):3877–3894. doi: 10.1007/s00018-018-2849-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Osman EY, et al. Functional characterization of SMN evolution in mouse models of SMA. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):9472. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-45822-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ogawa C, et al. Gemin2 plays an important role in stabilizing the survival of motor neuron complex. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(15):11122–11134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609297200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Young PJ, et al. A direct interaction between the survival motor neuron protein and p53 and its relationship to spinal muscular atrophy. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(4):2852–2859. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108769200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sprangers R, et al. High-resolution X-ray and NMR structures of the SMN Tudor domain: conformational variation in the binding site for symmetrically dimethylated arginine residues. J Mol Biol. 2003;327(2):507–520. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00148-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tripsianes K, et al. Structural basis for dimethylarginine recognition by the Tudor domains of human SMN and SPF30 proteins. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18(12):1414–1420. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Buhler D, et al. Essential role for the tudor domain of SMN in spliceosomal U snRNP assembly: implications for spinal muscular atrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8(13):2351–2357. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.13.2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pellizzoni L, et al. The survival of motor neurons (SMN) protein interacts with the snoRNP proteins fibrillarin and GAR1. Curr Biol. 2001;11(14):1079–1088. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00316-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mourelatos Z, et al. SMN interacts with a novel family of hnRNP and spliceosomal proteins. EMBO J. 2001;20(19):5443–5452. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.19.5443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rossoll W, et al. Specific interaction of Smn, the spinal muscular atrophy determining gene product, with hnRNP-R and gry-rbp/hnRNP-Q: a role for Smn in RNA processing in motor axons? Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11(1):93–105. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yamazaki T, et al. FUS-SMN protein interactions link the motor neuron diseases ALS and SMA. Cell Rep. 2012;2(4):799–806. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sabra M, et al. The Tudor protein survival motor neuron (SMN) is a chromatin-binding protein that interacts with methylated lysine 79 of histone H3. J Cell Sci. 2013;126(Pt 16):3664–3677. doi: 10.1242/jcs.126003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhao DY, et al. SMN and symmetric arginine dimethylation of RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain control termination. Nature. 2016;529(7584):48–53. doi: 10.1038/nature16469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hebert MD, et al. Coilin forms the bridge between Cajal bodies and SMN, the spinal muscular atrophy protein. Genes Dev. 2001;15(20):2720–2729. doi: 10.1101/gad.908401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Claus P, Bruns AF, Grothe C. Fibroblast growth factor-2(23) binds directly to the survival of motoneuron protein and is associated with small nuclear RNAs. Biochem J. 2004;384(Pt 3):559–565. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lorson CL, et al. SMN oligomerization defect correlates with spinal muscular atrophy severity. Nat Genet. 1998;19(1):63–66. doi: 10.1038/ng0598-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ardito F, et al. The crucial role of protein phosphorylation in cell signaling and its use as targeted therapy (review) Int J Mol Med. 2017;40(2):271–280. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.3036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mann M, et al. Analysis of protein phosphorylation using mass spectrometry: deciphering the phosphoproteome. Trends Biotechnol. 2002;20(6):261–268. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(02)01944-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Keenan EK, Zachman DK, Hirschey MD. Discovering the landscape of protein modifications. Mol Cell. 2021;81(9):1868–1878. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Levene PA, Alsberg CL. The cleavage products of vitellin. J Biol Chem. 1906;2(1):127–133. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(17)46054-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lipmann F. Analysis of phosphoproteins and developments in protein phosphorylation. Trends Biochem Sci. 1983;8(9):334–336. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(83)90105-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ghosh S, Marrocco I, Yarden Y. Roles for receptor tyrosine kinases in tumor progression and implications for cancer treatment. Adv Cancer Res. 2020;147:1–57. doi: 10.1016/bs.acr.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22(22):4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schilling M, et al. TOR signaling regulates liquid phase separation of the SMN complex governing snRNP biogenesis. Cell Rep. 2021;35(12):109277. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rikova K, et al. Global survey of phosphotyrosine signaling identifies oncogenic kinases in lung cancer. Cell. 2007;131(6):1190–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hornbeck PV, et al. PhosphoSitePlus, 2014: mutations, PTMs and recalibrations. Nucl Acids Res. 2015;43:D512–D520. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Weber C, Schreiber TB, Daub H. Dual phosphoproteomics and chemical proteomics analysis of erlotinib and gefitinib interference in acute myeloid leukemia cells. J Proteom. 2012;75(4):1343–1356. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Danielsen JM, et al. Mass spectrometric analysis of lysine ubiquitylation reveals promiscuity at site level. Mol Cell Proteom. 2011 doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.003590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kim W, et al. Systematic and quantitative assessment of the ubiquitin-modified proteome. Mol Cell. 2011;44(2):325–340. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wagner SA, et al. A proteome-wide, quantitative survey of in vivo ubiquitylation sites reveals widespread regulatory roles. Mol Cell Proteom. 2011 doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.013284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Han KJ, et al. Ubiquitin-specific protease 9x deubiquitinates and stabilizes the spinal muscular atrophy protein-survival motor neuron. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(52):43741–43752. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.372318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Akimov V, et al. UbiSite approach for comprehensive mapping of lysine and N-terminal ubiquitination sites. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2018;25(7):631–640. doi: 10.1038/s41594-018-0084-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sharma K, et al. Ultradeep human phosphoproteome reveals a distinct regulatory nature of Tyr and Ser/Thr-based signaling. Cell Rep. 2014;8(5):1583–1594. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rigbolt KT, et al. System-wide temporal characterization of the proteome and phosphoproteome of human embryonic stem cell differentiation. Sci Signal. 2011;4(164):rs3. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lafarga V, et al. CBP-mediated SMN acetylation modulates Cajal body biogenesis and the cytoplasmic targeting of SMN. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2018;75(3):527–546. doi: 10.1007/s00018-017-2638-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tapia O, et al. The SMN Tudor SIM-like domain is key to SmD1 and coilin interactions and to Cajal body biogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2014;127(Pt 5):939–946. doi: 10.1242/jcs.138537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mertins P, et al. Proteogenomics connects somatic mutations to signalling in breast cancer. Nature. 2016;534(7605):55–62. doi: 10.1038/nature18003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]