Abstract

Molecules based on the deprotonated p-hydroxycinnamate moiety are widespread in nature, including serving as UV filters in the leaves of plants and as the biochromophore in photoactive yellow protein. The photophysical behavior of these chromophores is centered around a rapid E → Z photoisomerization by passage through a conical intersection seam. Here, we use photoisomerization and photodissociation action spectroscopies with deprotonated 4-hydroxybenzal acetone (pCK–) to characterize a wavelength-dependent bifurcation between electron autodetachment (spontaneous ejection of an electron from the S1 state because it is situated in the detachment continuum) and E → Z photoisomerization. While autodetachment occurs across the entire S1(ππ*) band (370–480 nm), E → Z photoisomerization occurs only over a blue portion of the band (370–430 nm). No E → Z photoisomerization is observed when the ketone functional group in pCK– is replaced with an ester or carboxylic acid. The wavelength-dependent bifurcation is consistent with potential energy surface calculations showing that a barrier separates the Franck–Condon region from the E → Z isomerizing conical intersection. The barrier height, which is substantially higher in the gas phase than in solution, depends on the functional group and governs whether E → Z photoisomerization occurs more rapidly than autodetachment.

Molecules possessing the p-hydroxycinnamate moiety are widespread in nature.1 Examples include sinapoyl malate, caffeic acid, and ferulic acid in both the free form and covalently bound to cell walls and lignin structures, which are present in the leaves, stems, and seeds of plants where they function as UV-B filters.2 The UV-B filtering mechanism is, in part, thought to rely on a rapid internal conversion to the ground state, accompanied by E → Z photoisomerization.3 The efficacy of this nonradiative decay has prompted the skin-care industry to develop commercial sunscreens containing cinnamate-based molecules.4,5 In another biological context, deprotonated p-hydroxycinnamates are invoked as models for the chromophore in photoactive yellow protein (PYP), which is a small blue-light sensing protein found in the Halorhodospira halophila bacterium.6−8 In the PYP photocycle, absorption of blue light by a thioester-based hydroxycinnamate chromophore leads to an E → Z photoisomerization of the chromophore, which in turn leads to a change in protein conformation and eventually a negative phototaxis response of the bacterium.9−12

A desire to understand the photophysics of p-hydroxycinnamates and to develop synthetic derivatives that might be incorporated into optogenetic applications13−15 or skin-care products16 has prompted numerous investigations on the inherent photophysics in this class of molecules. Although the excited-state dynamics in p-hydroxycinnamates has been studied extensively in solution over the past two decades (see, for example, refs (17−22) and references therein), the extent to which solvation perturbs the intrinsic excited-state dynamics remains unclear. Theoretical investigations have suggested that solvation of anionic p-hydroxycinnamates significantly perturbs the S1(ππ*) potential energy surfaces and conical intersection seams,23−29 although experimental strategies capable of directly observing photoisomerization in the gas phase are now starting to emerge.30−32

Previous experiments on hydroxycinnamate anions, focusing on the inherent dynamics, utilized techniques including time-resolved photoelectron spectroscopy,33−35 frequency-resolved photoelectron spectroscopy to fingerprint internal conversion dynamics,36 and photoisomerization action (PISA) spectroscopy to select precursor deprotomers or geometric isomers and to probe photoisomerization or phototautomerization.32,37 However, these studies were unable to provide any evidence for E → Z photoisomerization across a series of around 20 hydroxycinnamate anions. The present study provides clear evidence for an E → Z photoisomerization response in deprotonated 4-hydroxybenzal acetone (pCK–, Figure 1a), a molecule which has been invoked as a proxy for the PYP chromophore.18,24,26,33,35,38 Importantly, the E → Z photoisomerization response occurs only following excitation of the higher photon energy region of the S1 ← S0 absorption band, consistent with earlier molecular dynamics simulations hypothesizing that photoisomerization by passage through a conical intersection is a barrier-controlled process.39−41 Our study provides experimental confirmation that functional group substitution on the hydroxycinnamate tail critically affects the excited-state barrier height and thus photoisomerization efficacy.24,26,42 Comparison of time-resolved data for pCK– in solution with gas phase data implies that the potential energy surface barrier to isomerization is stabilized in solution.

Figure 1.

(a) p-Hydroxycinnamate anions considered in this study. (b) Action spectra for pCK– (photodissociation, black) and pCEs– (photodetachment, blue, from ref (32)) as proxies for the S1 ← S0 absorption bands. The absorption spectrum of pCK– in water (at T = 300 K) is shown in red. Solid lines are moving averages over three data points for the gas phase and seven data points for the condensed phase data.

A photodissociation action spectrum (black), which serves as a proxy for the visible absorption spectrum of pCK–, is shown in Figure 1b. The spectrum was recorded by monitoring absorption-induced fragmentation of the anion under ultrahigh-vacuum conditions (see the Supporting Information for experimental details). The spectrum spans the 390–480 nm range with maximum response at 440 nm. The spectrum is red-shifted by ≈10 nm compared with the photodetachment action spectrum for the methyl ester (pCEs–) from ref (32) (see also ref (43)), corresponding to absorption-induced electron ejection. The origin of the red-shift for pCK– is presumably due to differences in inductive electron donation. The absorption spectrum of pCK- in water is blue-shifted by ≈80 nm relative to the photodissociation spectrum.

Photoisomerization of isolated pCK– was investigated using the emerging technique of PISA spectroscopy.

A detailed description and illustration of the PISA spectroscopy technique

are available in refs (30 and 44). Briefly, PISA spectroscopy allows for isomer-selected irradiation

experiments, isomer-specific product detection, and quantification

of photodetached electrons for anions using an electron scavenger

(SF6).32,44 In an experiment, charged isomers

that are drifting under the influence of an electric field through

a buffer gas (e.g., N2 or CO2) are separated

according to their drift speeds, which depend on their collision cross

sections. The target isomer is selected in a primary drift stage and

then exposed to wavelength tunable light, with separation of photoisomers

or photofragments in a second drift stage. By monitoring the yield

of photoisomers and  as a function of wavelength,

photoisomerization

and photodetachment action spectra are recorded. Complete experimental

details are given in the Supporting Information.

as a function of wavelength,

photoisomerization

and photodetachment action spectra are recorded. Complete experimental

details are given in the Supporting Information.

Electrospray ionization of pCK– in any of the buffer gases considered in this study produced a single

arrival time distribution (ATD) peak, consistent with a single isomer

(black traces in Figure 2a,b) assigned to the E configuration. In pure N2 buffer gas, the photoaction ATD in Figure 2a, corresponding to the difference between

“light on” and “light off” ATDs, shows

generation of a photoisomer at a slightly shorter arrival time, consistent

with the Z isomer, since cross-section modeling predicts

that the Z isomer has a smaller collision cross section

in pure N2 (Table 1). Similar results were obtained in pure CO2 buffer

gas (see the Supporting Information). The

photoaction ATD in N2 buffer gas doped with ≈1%

SF6 and ≈1% propan-2-ol shows generation of a photoisomer

at longer arrival time (assigned to Z) and electron

detachment as detected through  formation when using

420 nm light. Further

explanation on isomer-specific interactions with propan-2-ol leading

to the increased collision cross section for the Z isomer compared with the E isomer is given in the Supporting Information. Because the photodepletion

signal (i.e., bleach of the E isomer) in Figure 2b is balanced by

the sum of photoisomerization and electron detachment signals, the

experiment captures all prompt photoaction. This correspondence is

true across all wavelengths considered in this study. Notably, there

is no photodissociation in this experiment because collisional energy

quenching (tens to hundreds of nanoseconds) occurs more rapidly than

recovery of the ground electronic state followed by statistical dissociation

(microseconds).32,45

formation when using

420 nm light. Further

explanation on isomer-specific interactions with propan-2-ol leading

to the increased collision cross section for the Z isomer compared with the E isomer is given in the Supporting Information. Because the photodepletion

signal (i.e., bleach of the E isomer) in Figure 2b is balanced by

the sum of photoisomerization and electron detachment signals, the

experiment captures all prompt photoaction. This correspondence is

true across all wavelengths considered in this study. Notably, there

is no photodissociation in this experiment because collisional energy

quenching (tens to hundreds of nanoseconds) occurs more rapidly than

recovery of the ground electronic state followed by statistical dissociation

(microseconds).32,45

Figure 2.

Action spectroscopy of pCK–: (a) light-off (black) and photoaction (blue) ATD at 420 nm in pure N2 buffer gas; (b) light-off (black) and photoaction (blue, 420 nm and red, 435 nm) ATD in N2 buffer gas seeded with ≈1% propan-2-ol and ≈1% SF6; (c) electron photodetachment (red) and E → Z photoisomerization (blue) action spectra. The photoaction spectra show the changes between light-on and light-off ATDs, reflecting any photoinduced processes. The photoisomerization quantum yield is estimated at a 1–2% at 400 nm. See the Supporting Information for CO2 buffer gas data. The excited-state barrier to isomerization is estimated at ≈0.18 eV from the difference in spectral maxima in (c); use of thresholds is not reliable because of hot bands and the direct photodetachment contribution to electron detachment because the S1 state is situated in the detachment threshold.

Table 1. Calculated Properties for the E and Z Isomers of pCK–

| species | ΔEa | ADEa | VDEa | Ωc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (E)-pCK– | 0 | 2.83 | 2.90 | 137 |

| (Z)-pCK– | 27 | 2.80 | 2.86 | 136 |

| TSb | 125 | |||

| expt | 2.8 ± 0.1c | 3.0 ± 0.1c | 134 ± 5d |

ΔE in units of kJ mol–1; ADE (adiabatic detachment energy) and VDE (vertical detachment energy) in units of eV.

TS is the isomerization transition state on the ground electronic state. All energies at the DLPNO-CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pVTZ level of theory using ORCA 5.0.3.46 Ωc in units of Å2, calculated using MOBCAL.47,48

Reference (35).

(E)-pCK–.

Photodetachment (red) and photoisomerization (blue) action spectra for pCK– are shown in Figure 2c. While electron detachment is observed across the 370–480 nm range with maximum response at ≈435 nm, E – Z isomerization was observed only over the 360–430 nm range with maximum response at ≈405 nm. These spectra span the same wavelength range as the photodissociation spectrum (proxy for the absorption spectrum) in Figure 1b, although differing in shape, which is indicative of competitive photochemical pathways. It is worth noting that electron detachment may occur following absorption of a single photon because the onset of the action spectra is situated above the adiabatic detachment energy (Table 1) when allowing for the internal energy associated with temperature of the ions at T = 300 K (0.3 eV). This situation is also true for pCEs–.32,34,36,37

In PISA spectroscopy, an isomerization signal can result from two mechanisms: (i) a rapid excited-state process associated with passage through a conical intersection and (ii) statistical isomerization on the ground electronic state before collisions in the drift region thermalize the activated ions. In an earlier study considering pCEs–,32 we used master equation simulations combining RRKM isomerization rates with Langevin collisional energy quenching to explore the possibility of process ii, where it was concluded to be unlikely because of the electronic energy difference between the two isomers, although some Z → E thermal reversion may occur before collisions stabilize the isomers. To investigate thermal reversion (process ii) for pCK–, which may skew the appearance of the photoisomerization action spectra, we considered an experimental approach in which the ion mobility experiments were repeated in CO2 buffer gas (see the Supporting Information). The rationale is that the vibrational energy quenching collision cross section for CO2 is an order of magnitude larger than that for N2,49 providing more rapid thermalization and suppression of ground-state statistical processes. Because the action spectra in CO2 buffer gas closely resemble those shown in Figure 2c, it is unlikely that Z → E thermal reversion processes have a significant bearing on the action spectra.

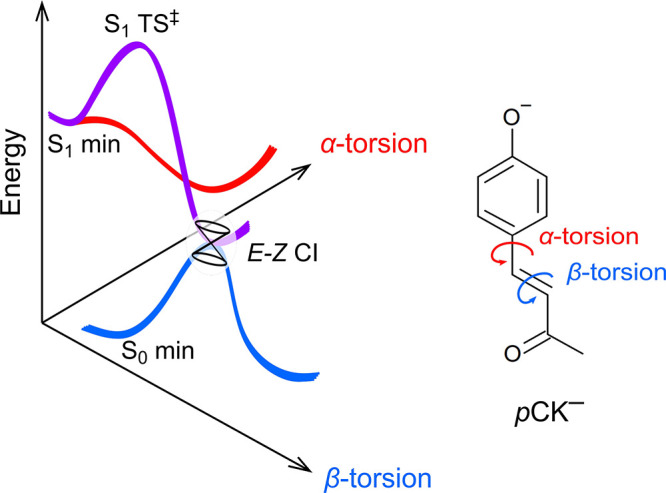

The occurrence of E → Z photoisomerization for pCK– in the gas phase contrasts with pCEs– and derivatives such as the phenoxide deprotomer of p-coumaric acid and ring-substituted derivatives caffeic, ferulic, and sinapinic acid (and methyl esters of each), for which no E → Z isomerization was observed.32,37 Earlier molecular dynamics simulations and related studies have suggested that there is a barrier on the S1 state potential energy surface for double-bond rotation (β-torsion coordinate in Figure 3a).39−41 A recent study of pCK– calculated a barrier of ≈0.25 eV along the β-torsion coordinate,35 although this value is based on linear interpolation of internal coordinates between the Franck–Condon geometry and the double-bond twisted minimum-energy structure. This value is lower than the earlier calculated barrier of ≈0.4 eV, relative to the Franck–Condon geometry, found for pCEs– using the DLPNO-STEOM-CCSD/aug-cc-pVDZ method.34 To enable a robust comparison between pCK– and pCEs–, we optimized the β-torsion critical points along the S1 potential energy surfaces (Figure 3) using a CASSCF(10,9) wave function followed by XMCQDPT2 energy calculations (Table 2) using the Firefly 8.2.0 software package.50 These calculations gave a barrier of 0.15 eV for pCK– and 0.33 eV for pCEs–, with torsion of the β coordinate of 53.5° (pCK–, −238 cm–1) and 49.1° (pCEs–, −325 cm–1) at the transition state. Significantly, the computed barrier for pCK– is in good agreement with experiment (≈0.18 eV) and is substantially lower than that for pCEs–.

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of potential energy surfaces for the E isomer of pCK– showing the α and β coordinates and identifying S0 and S1 minimum-energy geometries, the β-coordinate transition state (S1 TS‡), and the E–Z minimum-energy conical intersection (CI). Calculated energies for these critical points are given in Table 2. The α coordinate has been considered in ref (35).

Table 2. Calculated Potential Energy Surface Critical Points in eV at the XMCQDPT2(10,9)/aug-cc-PVDZ Level of Theory for pCK– and pCEs–

VEE = vertical excitation energy.

Relative to S1 min. Values relative to the Franck–Condon geometry are given in the text.

Having established the intrinsic E → Z photoisomerization response for pCK– at T = 300 K, we next considered excited-state lifetimes. Following rapid geometric relaxation from the Franck–Condon geometry (τ1 < 1 ps), gas phase lifetimes for pCK– have been determined to be τ2 = 52 ps when pumped at 400 nm33 and ≈120 ps when pumped at 444 nm,35 with the latter corresponding to exciting near the absorption band maximum. While the 400 nm study observed ground-state recovery (and assumed isomerization), the 444 nm study observed only autodetachment (spontaneous ejection of an electron from the S1 state because it is situated in the detachment continuum) and predicted α-torsion dynamics based on photoelectron angular distributions. The present action spectra shown in Figure 2c confirm that both time-resolved studies reached correct conclusions: excitation at 400 nm leads to isomerization while excitation at 444 nm does not. These dynamics contrast with pCEs–, which, when pumped near the maximum in its absorption band (438 nm), decays exclusively thorough autodetachment with a lifetime of 45 ± 4 ps.34 Similar autodetachment processes have been fingerprinted over the entire absorption band for pCEs– with no evidence for internal conversion and thus the possibility of Z isomer formation.36 The longer excited-state lifetime for pCK– compared with pCEs– when pumped near the maximum in the photodissociation action spectrum is presumably because, while the two anions have similar electron detachment thresholds, the absorption profile for pCK– is red-shifted by ≈0.1 eV (Figure 1), decreasing the propensity for electron autodetachment following rapid nuclear relaxation away from the Franck–Condon geometry.

To facilitate a comparison of gas phase excited-state lifetimes with those in solution, we performed time-resolved fluorescence upconversion (≈50 fs time resolution) on pCK– dissolved in a series of polar solvents at T = 300 K.51,52 Fluorescence upconversion is a time-resolved spectroscopic technique in which the fluorescence emission from a sample is frequency mixed with a probe laser pulse (800 nm), producing an “upconverted” signal. By changing the delay between femtosecond pump and probe pulses, and monitoring the upconverted signal, fluorescence lifetimes are measured. The present upconversion measurements refine an earlier solvent polarity and viscosity upconversion study on pCK– 18 and were performed because the earlier study (i) was limited by ≈500 fs time resolution, (ii) used an excitation wavelength (340 nm), which is far from the absorption maximum and likely accesses a nπ* state that gains substantial intensity through Herzberg–Teller coupling,36 and (iii) assumed static samples that likely gave rise to photostationary states. Steady-state fluorescence excitation and emission spectra for pCK– in water are shown in Figure 4a, revealing a large Stokes shift of 5794 ± 20 cm–1 (4143 ± 20 cm–1 in ethanol; see further data in the Supporting Information); the large shift is in part attributed to hydrogen-bond interactions between the phenoxide group and solvent molecules weakening upon excitation.17,19,41 The Stokes shift at T = 77 K is significantly lower at 2243 ± 20 cm–1 (ethanol), consistent with inhibition of nuclear and/or solvent relaxation to reach the lowest energy fluorescing geometry.

Figure 4.

Fluorescence

spectroscopy of pCK– in solution

at T = 300 K: (a) excitation (red,

monitoring at 480 nm) and emission (blue, exciting at 400 nm) fluorescence

spectra in water; (b) time-resolved fluorescence upconversion decay

curves and model fits in a series of alcohols (fitted values are given

in the Supporting Information). Experimental

data points are shown for ButOH; (c) viscosity (η) effect of  in a series of alcohols (red) and water–ethylene

glycol mixtures (blue).

in a series of alcohols (red) and water–ethylene

glycol mixtures (blue).

Fluorescence upconversion data following excitation of pCK– with 400 nm light, which were measured in a flow cell at T = 300 K, are shown in Figure 4b; results for water–ethylene-glycol mixtures are given in the Supporting Information. The decay curves were fit with a two-component exponential decay model with lifetime τ1 dominated by rapid solvent rearrangement (limited by the cross correlation), and τ2 is linked to the excited-state lifetime and associated solvent motion, i.e., convoluted with the ≈880 fs longest time scale dynamics for water rearrangement.53 Fitted lifetimes in selected solvents are given in Table 3 (see all data in the Supporting Information). It is worth nothing that the ≈1 ps lifetime of pCK– in water is comparable with the time scale for E → Z photoisomerization of the chromophore in PYP.11,54 It is striking that the excited-state lifetimes for pCK– in solution are 1 or 2 orders of magnitude shorter than in the gas phase, suggesting a considerable reduction of the isomerization barrier in solution or access of an alternative relaxation pathway. This situation contrasts with anionic retinoids in the gas phase that undergo barrier-controlled stereospecific E–Z photoisomerization and have considerably shorter lifetimes than in solution.55 Studies of derivative hydroxycinnamate chromophores in solution have shown that the excited-state lifetime is sensitive to the identity of the functional group on the carbonyl tail,19 with the ketone group for pCK– giving rise to the shortest lifetimes, although an overall picture is complicated because of solvent polarity effects, differences in charge-transfer character, and hydrogen bonding.20

Table 3. Fitted Excited-State Lifetimes (τ2 in ps) for pCK– in Water and Alcohol Solvents at T = 300 K.

| species | τ2 | ± |

|---|---|---|

| water | 1.17 | 0.01 |

| MeOH | 2.45 | 0.02 |

| EtOH | 2.33 | 0.04 |

| 1-PropOH | 3.40 | 0.07 |

| 2-PropOH | 3.84 | 0.04 |

| ButOH | 5.47 | 0.05 |

| PentOH | 7.11 | 0.08 |

| HeptOH | 8.44 | 0.10 |

| OctOH | 6.57 | 0.04 |

The influence of viscosity on the

excited-state lifetime of pCK– is

shown in Figure 4c

revealing a strong effect, consistent with

an isomerization-type reaction. See the Supporting Information for the solvent polarity effect. Following ref (18), excited-state lifetimes

as a function of viscosity were fit with the phenomenological power

law  ,56 where kf is assumed as the photoisomerization rate

and C is proportional to the Arrhenius term

,56 where kf is assumed as the photoisomerization rate

and C is proportional to the Arrhenius term  and is linked to polarity dependence (stabilization)

of the transition state. The parameter α is a measure of the

viscosity effect for isomerization, which approaches unity in highly

viscous solvents.57 Fitted values of α

are 0.53 and 0.59 for the alcohols and water–ethylene glycol

mixtures, respectively, with the latter being slightly larger than

that reported in ref (18). Assuming an Arrhenius relation at T = 300 K and

a pre-exponential factor of

and is linked to polarity dependence (stabilization)

of the transition state. The parameter α is a measure of the

viscosity effect for isomerization, which approaches unity in highly

viscous solvents.57 Fitted values of α

are 0.53 and 0.59 for the alcohols and water–ethylene glycol

mixtures, respectively, with the latter being slightly larger than

that reported in ref (18). Assuming an Arrhenius relation at T = 300 K and

a pre-exponential factor of  s–1, the excited-state

barrier height in water is ≈0.07 eV, which is around half of

the gas phase value. This estimate is consistent with potential energy

surface calculations on the dianion of p-coumaric

acid with microhydration, showing a reduction of the barrier from

0.70 eV (gas phase) to 0.09 eV. Values of α have been determined

at 0.64 for pCEs– 18 and 0.75 for the thioester anion,17 consistent with pCK– having the lowest isomerization barrier in solution. We conclude

that solvation significantly stabilizes the barrier to isomerization.

s–1, the excited-state

barrier height in water is ≈0.07 eV, which is around half of

the gas phase value. This estimate is consistent with potential energy

surface calculations on the dianion of p-coumaric

acid with microhydration, showing a reduction of the barrier from

0.70 eV (gas phase) to 0.09 eV. Values of α have been determined

at 0.64 for pCEs– 18 and 0.75 for the thioester anion,17 consistent with pCK– having the lowest isomerization barrier in solution. We conclude

that solvation significantly stabilizes the barrier to isomerization.

In summary, this study has demonstrated that E → Z photoisomerization of a p-hydroxycinnamate anion may occur in the gas phase, although a barrier to double-bond torsion on the S1(ππ*) potential energy surface is a key factor in defining if photoisomerization is competitive with electron autodetachment. Substitution on the carbonyl group tunes the barrier height separating the Franck–Condon geometry and the E–Z isomerizing conical intersection seam. Solvation of the chromophore significantly stabilizes the excited-state barrier, leading to rapid nonradiative relaxation. The present experimental strategy is applicable to other charged systems that may photoisomerize and possess excited-state barriers, and is particularly applicable to systems for which there are wavelength-dependent dynamics leading to multiple isomeric products.55 Future work on deprotonated hydroxycinnamate anions will seek to photogenerate, isolate, and apply frequency and time-resolved action spectroscopy techniques to Z isomers, as well as other unstable or intermediate isomers such as keto–enol tautomers,32 to map out excited-state potential energy surfaces.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded through a University of East Anglia start-up allowance (to J.N.B.), the Australian Research Council Discovery Project scheme (DP150101427 and DP160100474 to E.J.B.), and a NSERC Discovery Grant (RGPIN-2017-04217 to W.H.S.). E.K.A. acknowledges a University of East Anglia doctoral studentship. N.J.A.C. acknowledges a Vanier-Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship from NSERC. Dr. Palas Roy is thanked for training on the fluorescence upconversion experiment. Electronic structure calculations were performed on the High Performance Computing Cluster supported by the Research and Specialist Computing Support service at the University of East Anglia.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jpclett.2c02613.

Experimental methods; theoretical methods; CASSCF orbitals; vertical excitation energies; action spectroscopy in CO2 buffer gas; pCK–·propan-2-ol complexes; solution spectroscopy; critical point geometries (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Pei K.; Ou J.; Huang J.; Ou S. p-Coumaric Acid and its Conjugates: Dietary Sources, Pharmacokinetic Properties and Biological Activities. J. Sci. Food Agricul. 2016, 96, 2952–2962. 10.1002/jsfa.7578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker L. A.; Horbury M. D.; Greenough S. E.; Allais F.; Walsh P. S.; Habershon S.; Stavros V. G. Ultrafast Photoprotecting Sunscreens in Natural Plants. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2016, 7, 56–61. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b02474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker L. A.; Marchetti B.; Karsili T. N. V.; Stavros V. G.; Ashfold M. N. R. Photoprotection: Extending Lessons Learned From Studying Natural Sunscreens to the Design of Artificial Sunscreen Constituents. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 3770–3791. 10.1039/C7CS00102A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt E. L.; Stavros V. G. Applications of Ultrafast Spectroscopy to Sunscreen Development, From First Principles to Complex Mixtures. Int. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2019, 38, 243–285. 10.1080/0144235X.2019.1663062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita S.; Harabuchi Y.; Inokuchi Y.; Maeda S.; Ehara M.; Yamazaki K.; Ebata T. Substitution Effect on the Nonradiative Decay and trans → cis Photoisomerization Route: A Guideline to Develop Efficient Cinnamate-Based Sunscreens. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 834–845. 10.1039/D0CP04402D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer T. Isolation and Characterization of Soluble Cytochromes, Ferredoxins and Other Chromophoric Proteins From the Halophilic Phototrophic Bacterium Ectothiorhodospira halophila. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Bioenergetics 1985, 806, 175–183. 10.1016/0005-2728(85)90094-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer T. E.; Yakali E.; Cusanovich M. A.; Tollin G. Properties of a Water-Soluble, Yellow Protein Isolated From a Halophilic Phototrophic Bacterium that has Photochemical Activity Analogous to Sensory Rhodopsin. Biochem 1987, 26, 418–423. 10.1021/bi00376a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprenger W. W.; Hoff W. D.; Armitage J. P.; Hellingwerf K. J. The Eubacterium Ectothiorhodospira halophila is Negatively Phototactic, With a Wavelength Dependence that Fits the Absorption Spectrum of the Photoactive Yellow Protein. J. Bacteriol. 1993, 175, 3096–3104. 10.1128/jb.175.10.3096-3104.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wilderen L. J. G. W.; van der Horst M. A.; van Stokkum I. H. M.; Hellingwerf K. J.; van Grondelle R.; Groot M. L. Ultrafast Infrared Spectroscopy Reveals a Key Step For Successful Entry Into the Photocycle For Photoactive Yellow Protein. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 2006, 103, 15050–15055. 10.1073/pnas.0603476103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenboer J.; Basu S.; Zatsepin N.; Pande K.; Milathianaki D.; Frank M.; Hunter M.; Boutet S.; Williams G. J.; Koglin J. E.; et al. Time-Resolved Serial Crystallography Captures High-Resolution Intermediates of Photoactive Yellow Protein. Science 2014, 346, 1242–1246. 10.1126/science.1259357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pande K.; Hutchison C. D. M.; Groenhof G.; Aquila A.; Robinson J. S.; Tenboer J.; Basu S.; Boutet S.; DePonte D. P.; Liang M.; et al. Femtosecond Structural Dynamics Drives the trans/cis Isomerization in Photoactive Yellow Protein. Science 2016, 352, 725–729. 10.1126/science.aad5081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuramochi H.; Takeuchi S.; Yonezawa K.; Kamikubo H.; Kataoka M.; Tahara T. Probing the Early Stages of Photoreception in Photoactive Yellow Protein With Ultrafast Time-Domain Raman Spectroscopy. Nat. Chem. 2017, 9, 660–666. 10.1038/nchem.2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losi A.; Gardner K. H.; Möglich A. Blue-Light Receptors for Optogenetics. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 10659–10709. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang J.; Woolley G. A. Directed Evolution Approaches for Optogenetic Tool Development. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2021, 49, 2737–2748. 10.1042/BST20210700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seong J.; Lin M. Z. Optobiochemistry: Genetically Encoded Control of Protein Activity by Light. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2021, 90, 475–501. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-072420-112431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zillich O. V.; Schweiggert-Weisz U.; Eisner P.; Kerscher M. Polyphenols as Active Ingredients For Cosmetic Products. Int. J. Cosmetic Sci. 2015, 37, 455–464. 10.1111/ics.12218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espagne A.; Changenet-Barret P.; Plaza P.; Martin M. M. Solvent Effect on the Excited-State Dynamics of Analogues of the Photoactive Yellow Protein Chromophore. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 3393–3404. 10.1021/jp0563843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espagne A.; Paik D. H.; Changenet-Barret P.; Martin M. M.; Zewail A. H. Ultrafast Photoisomerization of Photoactive Yellow Protein Chromophore Analogues in Solution: Influence of the Protonation State. ChemPhysChem 2006, 7, 1717–1726. 10.1002/cphc.200600137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espagne A.; Paik D. H.; Changenet-Barret P.; Plaza P.; Martin M. M.; Zewail A. H. Ultrafast Light-Induced Response of Photoactive Yellow Protein Chromophore Analogues. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2007, 6, 780–787. 10.1039/b700927e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espagne A.; Changenet-Barret P.; Baudin J.-B.; Plaza P.; Martin M. M. Photoinduced Charge Shift as the Driving Force For the Excited-State Relaxation of Analogues of the Photoactive Yellow Protein Chromophore in Solution. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem. 2007, 185, 245–252. 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2006.06.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuramochi H.; Takeuchi S.; Tahara T. Ultrafast Structural Evolution of Photoactive Yellow Protein Chromophore Revealed by Ultraviolet Resonance Femtosecond Stimulated Raman Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2012, 3, 2025–2029. 10.1021/jz300542f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.; Schatz S.; Stuhldreier M. C.; Böhnke H.; Wiese J.; Schröder C.; Raeker T.; Hartke B.; Keppler J. K.; Schwarz K.; et al. Ultrafast Dynamics of UV-Excited trans- and cis-Ferulic Acid in Aqueous Solutions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 30683–30694. 10.1039/C7CP05301K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gromov E. V.; Burghardt I.; Köppel H.; Cederbaum L. S. Photoinduced Isomerization of the Photoactive Yellow Protein (PYP) Chromophore: Interplay of Two Torsions, a HOOP Mode and Hydrogen Bonding. J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115, 9237–9248. 10.1021/jp2011843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boggio-Pasqua M.; Groenhof G. Controlling the Photoreactivity of the Photoactive Yellow Protein Chromophore by Substituting at the p-Coumaric Acid Group. J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 115, 7021–7028. 10.1021/jp108977x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isborn C. M.; Götz A. W.; Clark M. A.; Walker R. C.; Martínez T. J. Electronic Absorption Spectra From MM and Ab Initio QM/MM Molecular Dynamics: Environmental Effects on the Absorption Spectrum of Photoactive Yellow Protein. J. Chem. Theory Comput.h 2012, 8, 5092–5106. 10.1021/ct3006826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gromov E. V. Unveiling the Mechanism of Photoinduced Isomerization of the Photoactive Yellow Protein (PYP) Chromophore. J. Chem. Phys. 2014, 141, 224308. 10.1063/1.4903174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Prieto F. F.; Munoz-Losa A.; Luz Sanchez M.; Elena Martin M.; Aguilar M. A. Solvent Effects on De-Excitation Channels in the p-Coumaric Acid Methyl Ester Anion, An Analogue of the Photoactive Yellow Protein (PYP) Chromophore. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 27476–27485. 10.1039/C6CP03541H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Prieto F. F.; Muñoz Losa A.; Fdez. Galván I.; Sánchez M. L.; Aguilar M. A.; Martín M. E. QM/MM Study of Substituent and Solvent Effects on the Excited State Dynamics of the Photoactive Yellow Protein Chromophore. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2017, 13, 737–748. 10.1021/acs.jctc.6b01069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomoto A.; Inai N.; Yanai T.; Okuno Y. Substituent and Solvent Effects on the Photoisomerization of Cinnamate Derivatives: An XMS-CASPT2 Study. J. Phys. Chem. A 2022, 126, 497–505. 10.1021/acs.jpca.1c08504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamson B. D.; Coughlan N. J. A.; Continetti R. E.; Bieske E. J. Changing the Shape of Molecular Ions: Photoisomerization Action Spectroscopy in the Gas Phase. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 9540–9548. 10.1039/c3cp51393a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markworth P. B.; Coughlan N. J. A.; Adamson B. D.; Goerigk L.; Bieske E. J. Photoisomerization Action Spectroscopy: Flicking the Protonated Merocyanine-Spiropyran Switch in the Gas Phase. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 25676–25688. 10.1039/C5CP01567G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull J. N.; da Silva G.; Scholz M. S.; Carrascosa E.; Bieske E. J. Photoinduced Intramolecular Proton Transfer in Deprotonated para-Coumaric Acid. J. Phys. Chem. A 2019, 123, 4419–4430. 10.1021/acs.jpca.9b02023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee I.-R.; Lee W.; Zewail A. H. Primary Steps of the Photoactive Yellow Protein: Isolated Chromophore Dynamics and Protein Directed Function. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 2006, 103, 258–262. 10.1073/pnas.0510015103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull J. N.; Anstöter C. S.; Verlet J. R. R. Ultrafast Valence to Non-Valence Excited State Dynamics in a Common Anionic Chromophore. Nature Comm 2019, 10, 5820. 10.1038/s41467-019-13819-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anstöter C. S.; Curchod B. F. E.; Verlet J. R. R. Geometric and Electronic Structure Probed Along the Isomerisation Coordinate of a Photoactive Yellow Protein Chromophore. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2827. 10.1038/s41467-020-16667-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull J. N.; Anstöter C. S.; Verlet J. R. R. Fingerprinting the Excited-State Dynamics in Methyl Ester and Methyl Ether Anions of Deprotonated para-Coumaric Acid. J. Phys. Chem. A 2020, 124, 2140–2151. 10.1021/acs.jpca.9b11993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull J. N.; Buntine J. T.; Carrascosa E.; Stockett M. H.; Bieske E. J. Action Spectroscopy of Deprotomer-Selected Hydroxycinnamate Anions. Eur. Phys. J. D 2021, 75, 67. 10.1140/epjd/s10053-021-00070-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mustalahti S.; Morozov D.; Luk H. L.; Pallerla R. R.; Myllyperkiö P.; Pettersson M.; Pihko P. M.; Groenhof G. Photoactive Yellow Protein Chromophore Photoisomerizes around a Single Bond if the Double Bond Is Locked. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 2177–2181. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.0c00060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenhof G.; Bouxin-Cademartory M.; Hess B.; de Visser S. P.; Berendsen H. J. C.; Olivucci M.; Mark A. E.; Robb M. A. Photoactivation of the Photoactive Yellow Protein: Why Photon Absorption Triggers a Trans-to-Cis Isomerization of the Chromophore in the Protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 4228–4233. 10.1021/ja039557f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenhof G.; Schäfer L. V.; Boggio-Pasqua M.; Grubmüller H.; Robb M. A. Arginine52 Controls the Photoisomerization Process in Photoactive Yellow Protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 3250–3251. 10.1021/ja078024u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boggio-Pasqua M.; Robb M. A.; Groenhof G. Hydrogen Bonding Controls Excited-State Decay of the Photoactive Yellow Protein Chromophore. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 13580–13581. 10.1021/ja904932x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkes M. A.; Phillips C.; Porter M. J.; Fielding H. F. Controlling Electron Emission From the Photoactive Yellow Protein Chromophore by Substitution at the Coumaric Acid Group. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 10329–10336. 10.1039/C6CP00565A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha-Rinza T.; Christiansen O.; Rajput J.; Gopalan A.; Rahbek D. B.; Andersen L. H.; Bochenkova A. V.; Granovsky A. A.; Bravaya K. B.; Nemukhin A. V.; et al. Gas Phase Absorption Studies of Photoactive Yellow Protein Chromophore Derivatives. J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 9442–9449. 10.1021/jp904660w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamson B. D.; Coughlan N. J. A.; Markworth P. B.; Continetti R. E.; Bieske E. J. An Ion Mobility Mass Spectrometer for Investigating Photoisomerization and Photodissociation of Molecular Ions. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2014, 85, 123109. 10.1063/1.4903753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull J. N.; Scholz M. S.; Carrascosa E.; da Silva G.; Bieske E. J. Double Molecular Photoswitch Driven by Light and Collisions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 120, 223002. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.120.223002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neese F. The ORCA program system. WIRES Comp. Mol. Sci. 2012, 2, 73–78. 10.1002/wcms.81. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campuzano I.; Bush M. F.; Robinson C. V.; Beaumont C.; Richardson K.; Kim H.; Kim H. I. Structural Characterization of Drug-Like Compounds by Ion Mobility Mass Spectrometry: Comparison of Theoretical and Experimentally Derived Nitrogen Collision Cross Sections. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 1026–1033. 10.1021/ac202625t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesleh M. F.; Hunter J. M.; Shvartsburg A. A.; Schatz G. C.; Jarrold M. F. Structural Information From Ion Mobility Measurements: Effects of the Long-Range Potential. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 16082–16086. 10.1021/jp961623v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Child M. S.Molecular Collision Theory; Dover Publications Inc.: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Granovsky A. A. Firefly Version 8.2.0. http://classic.chem.msu.su/gran/firefly/index.html.

- Heisler I. A.; Kondo M.; Meech S. R. Reactive Dynamics in Confined Liquids: Ultrafast Torsional Dynamics of Auramine O in Nanoconfined Water in Aerosol OT Reverse Micelles. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 1623–1631. 10.1021/jp808989f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chosrowjan H.; Taniguchi S.; Tanaka F. Ultrafast Fluorescence Upconversion Technique and its Applications to Proteins. FEBS J. 2015, 282, 3003–3015. 10.1111/febs.13180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez R.; Fleming G. R.; Kumar P. V.; Maroncelli M. Femtosecond Solvation Dynamics of Water. Nature 1994, 369, 471–473. 10.1038/369471a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseinizadeh A.; Breckwoldt N.; Fung R.; Sepehr R.; Schmidt M.; Schwander P.; Santra R.; Ourmazd A. Few-fs Resolution of a Photoactive Protein Traversing a Conical Intersection. Nature 2021, 599, 697–701. 10.1038/s41586-021-04050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull J. N.; West C. W.; Anstöter C. S.; da Silva G.; Bieske E. J.; Verlet J. R. R. Ultrafast Photoisomerisation of an Isolated Retinoid. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 10567–10579. 10.1039/C9CP01624D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichardt C.; Welton T.. Solvents and Solvent Effects in Organic Chemistry; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Anna J. M.; Kubarych K. J. Watching Solvent Friction Impede Ultrafast Barrier Crossings: A Direct Test of Kramers Theory. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 133, 174506. 10.1063/1.3492724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.