Abstract

Rates of stimulant use, including misuse of prescription stimulants and use of cocaine and methamphetamine, are rising rapidly among adolescents and young adults (“youth”). Stimulant misuse is associated with overdose, polysubstance use, substance use disorders, and other medical harms. Substance use is often initiated during adolescence and young adulthood, and interventions during these crucial years have the potential to impact the lifetime risk of stimulant use disorder and associated harms. In this narrative review, we review recent data on prescription and illicit stimulant use in youth. We describe the rising contribution of stimulants to polysubstance use involving opioids and other substances and to overdose, as well as ways to minimize harm. We also discuss prescription stimulant misuse, which is especially prevalent among youth relative to other age groups, and the limited evidence on potential pathways from prescription stimulant use to illicit stimulant use. Last, we assess potential strategies for the prevention and treatment of stimulant use disorder in youth.

Drug overdoses continue to pose a major threat to the health of all age groups in the US, but may be rising the most rapidly among youth, with a 48% increase in overdose deaths from 2019 to 2020 among those aged 15–24.1 While efforts to combat the overdose epidemic have largely been focused on opioids, rates of stimulant use and overdose are rising. This growing stimulant use epidemic, like that of opioids, involves the use of illicit products as well as nonmedical use of prescription medications and poses a significant threat to adolescents and young adults (a group collectively referred to as “youth” throughout this review). Youth are a key group to address in the national addiction crisis, as adolescence is a common time of substance use initiation,2,3 and efforts to reduce youth substance use are crucial for reducing the risk of lifetime addiction and its associated harms.4,5 Despite the importance of intervening early with stimulant use, little research has focused on pathways to use or treatment options for youth with stimulant use disorder. In this narrative review, we begin by presenting data on the epidemiology of stimulant use in youth, with a focus on the most commonly used stimulants as well as polysubstance use. We then review the harms associated with stimulant use. Finally, we discuss critical gaps in the literature regarding pathways to initiation of stimulant use among youth as well as effective treatments and prevention strategies.

History and Epidemiology of Illicit Stimulant Use

Historically, the United States has experienced many epidemics of stimulant use and overdose. Nonetheless, the current epidemic is large and growing, and has a close association with the opioid-related overdose crisis due to the increasing prevalence of polysubstance use (i.e., use of multiple substances simultaneously). One of the first documented stimulant epidemics in the United States began around World War II, during which soldiers and civilians commonly used amphetamines, marketed at the time for myriad medical uses.6 Perhaps the most well-known stimulant epidemic with wide-ranging political and economic consequences is the crack cocaine epidemic of the 1980s. The increased use of this new form of cocaine was met with policy and law enforcement action instead of clinical and public health responses, causing disproportionate consequences for Black communities.7–9 Amphetamine use decreased as federal regulations on substances tightened but has more recently seen a resurgence in the form of illicit methamphetamine and nonmedical use of prescription medications, including among youth.6 Today, nonmedical use of prescription stimulants is the most common way that youth misuse stimulants, and cocaine and methamphetamine remain the most commonly used illicit stimulants. It should be noted that MDMA, a drug with euphoric and psychedelic properties, is also a stimulant. MDMA, however, is used primarily for its psychedelic properties in party settings and is therefore not included in this review.

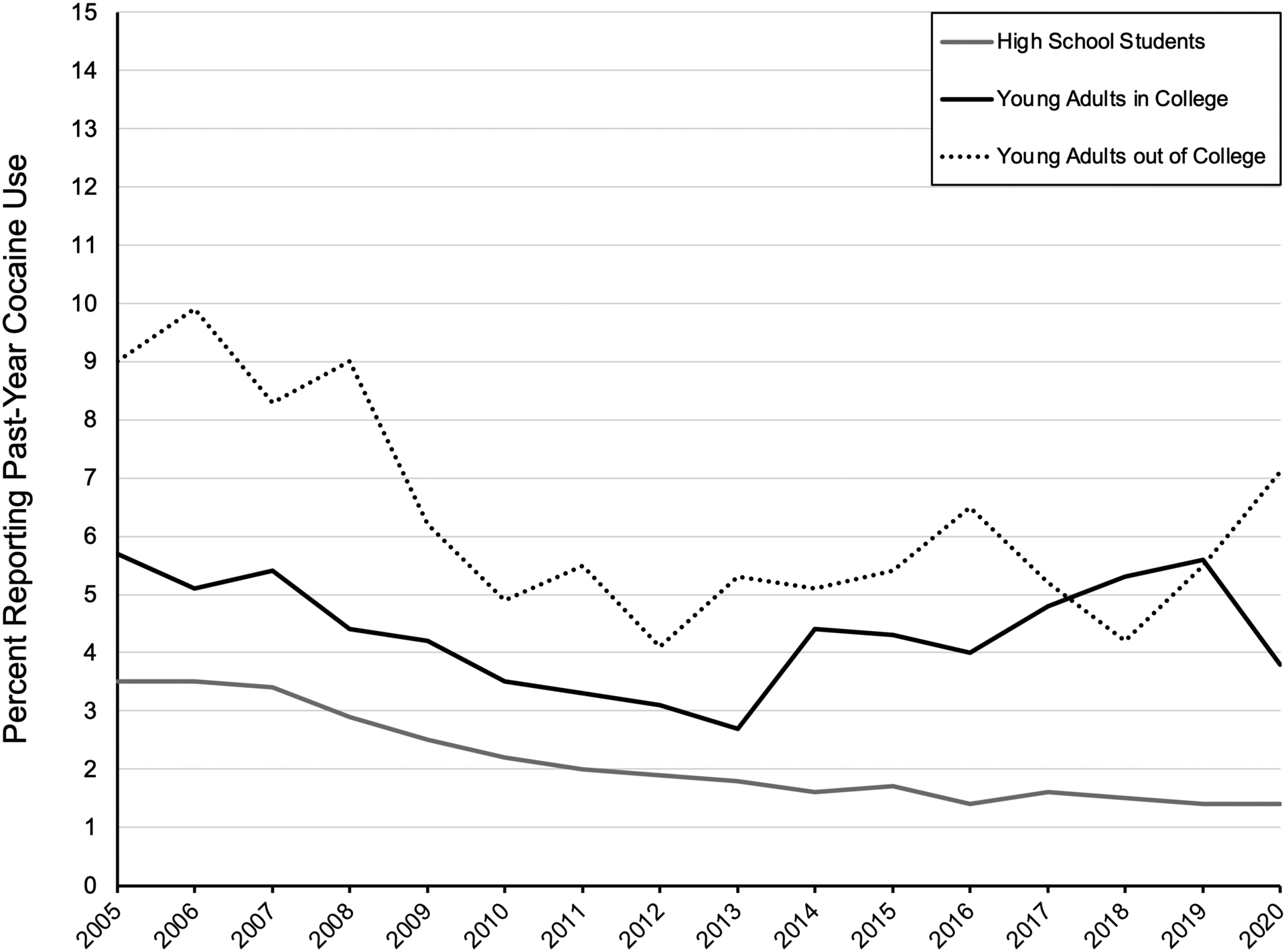

Despite decreasing use of crack cocaine, powdered cocaine remains a commonly used substance, particularly in young adults aged 18–25, of whom 4.3% reported past-year use in 2020 in the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, a residential-based survey.10 Although the prevalence of cocaine use reached an all-time low in 2013 in young adults, it has since steadily increased.11 Among high school students, 4.1% of seniors reported having ever used cocaine,12 and although lifetime cocaine use among high school students declined between 1999 and 2009, it subsequently rose.13 Among youth, cocaine use prevalence is highest in the Western US and lowest in the South. Figure 1 compares trends in recent (i.e., past-year) cocaine use in adolescents and young adults in Monitoring the Future, another national survey.

Figure 1:

Past-year use of cocaine, Monitoring the Future, United States, 2005–2020.

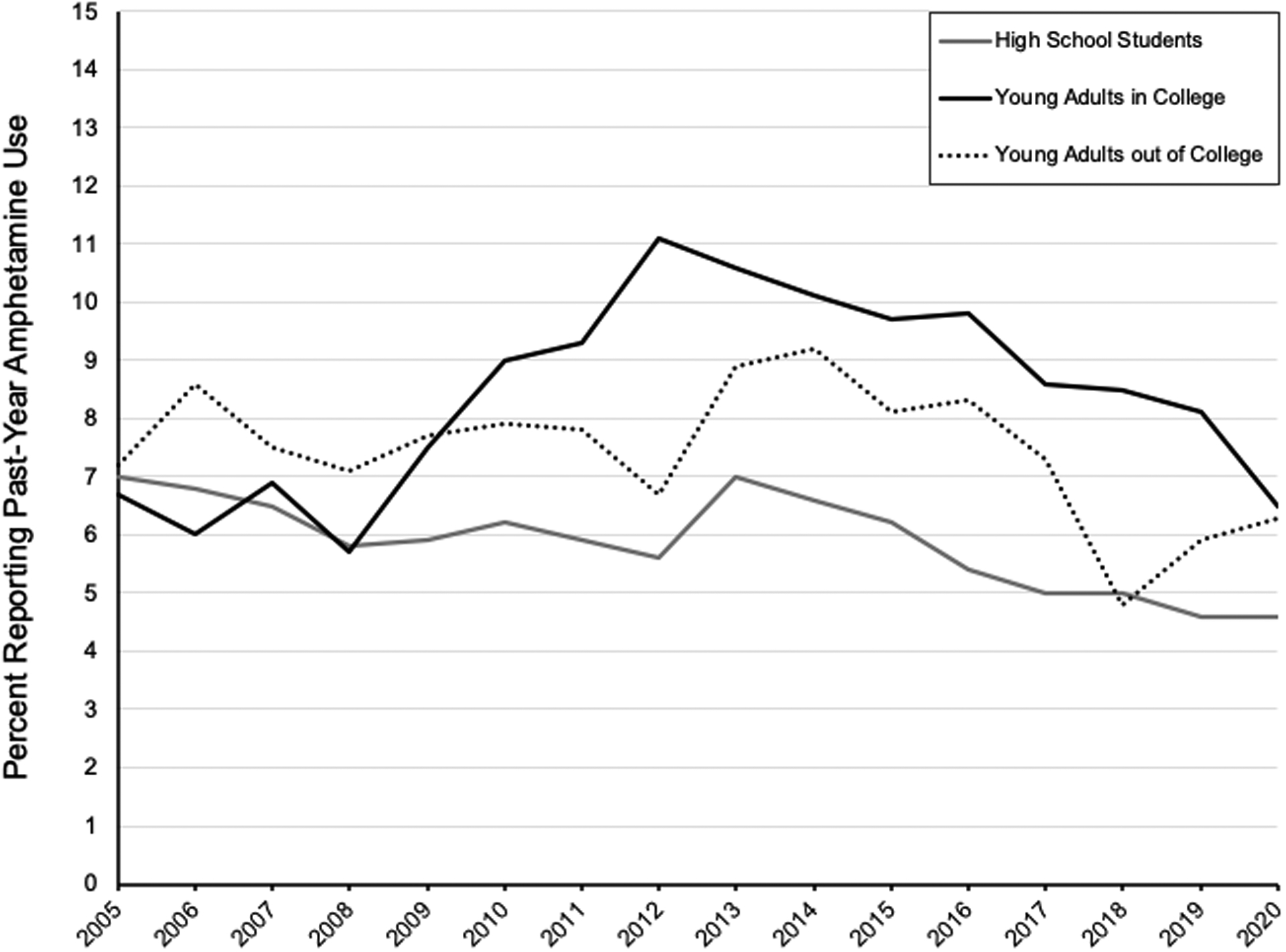

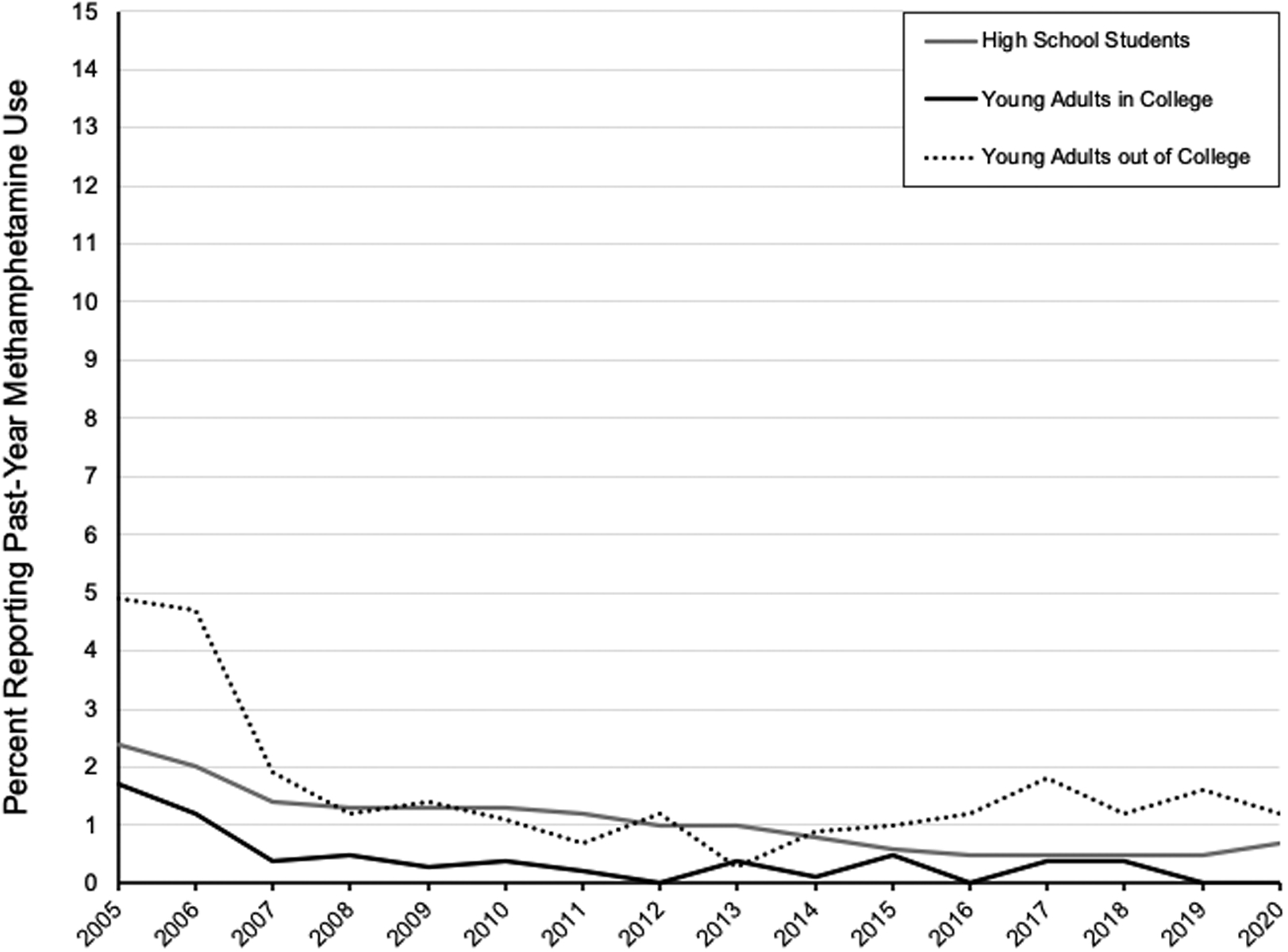

Patterns of methamphetamine use have changed dramatically in the past two decades. Methamphetamine use in the US was historically concentrated in the West and Midwest where it was made in home labs using pseudoephedrine, an over-the-counter decongestant medication.14 More potent methamphetamine imported from Mexico has become increasingly available, and use has been rising across the US, including areas with historically low use, such as the Northeast.15 White men were the primary demographic using methamphetamine in the 1980s, but use has been increasing among many demographic groups, including Latino populations, women, sexual minorities, and youth.14,16 Among high school seniors, 1.7% reported having ever used methamphetamine in 2020, up from 0.8% in 2019.17 Among college-age adults, 1.6% reported having ever used methamphetamine.10 Figure 2 compares trends in recent (i.e., past-year) amphetamine (panel A) and methamphetamine use (panel B) in adolescents and young adults in Monitoring the Future. Methamphetamine supply dipped early on in the COVID-19 pandemic, however, by August 2020 rates of law enforcement seizures of methamphetamine had risen above pre-pandemic levels.18

Figure 2:

Past-year use of amphetamine (panel A) and methamphetamine (panel B), Monitoring the Future, United States, 2005–2020. Note that methamphetamine is considered a subtype of amphetamine in Monitoring the Future data reporting.

While stimulant overdoses remain most common among those aged 35–39,19 youth are a crucial group for research and intervention related to stimulant use for a few key reasons. First, most individuals initiate substance use as adolescents, making this a crucial time to intervene.2,3 In some settings, first nonmedical misuse of prescription stimulants peaks between the ages of 16 and 19,2 and half of methamphetamine users report initiating before age 18.20 Nationally, the mean age of initiation is 18 years for cocaine and crack cocaine use, 17 years for methamphetamine use, and 17 for nonmedical prescription stimulant misuse.21 Individuals who initiate substance use at younger ages are also more likely to develop use disorders than those who initiate later (i.e., during adulthood).5,22 Individuals who initiate use at younger ages are also more likely to use multiple substances,3 and are less likely to seek treatment for substance use disorders.23 While the evidence is clear that adolescent initiation of substance use portends adult use, evidence is lacking on the specific impacts of stimulant misuse and the possible differential impacts of illicit and nonmedical prescription stimulant use during youth, and this area requires further study.24,25

Disparities in Illicit Stimulant Use:

Differences exist in adolescent stimulant use by race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and educational status. Cocaine and methamphetamine are both more common among adolescent boys and men.13,26 School-based surveys suggest that students who identify as American Indian/Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and Hispanic are more likely to use cocaine than their white peers, while Black and Asian adolescents are the least likely to use cocaine.13 Home-based surveys suggest that for adolescents aged 12–18, those who are Black, Asian, or American Indian or Alaskan Native are less likely than white adolescents to use cocaine.27 Bisexual high school girls report the highest rates of cocaine use among adolescent girls, while lesbians report the highest rates of methamphetamine use26,28 Sexual minority boys also report higher rates of methamphetamine and cocaine use than their straight peers, with gay high school males reporting the highest rates of use, followed by those who are unsure about their sexual orientation, bisexual males, and finally, straight males.28 Lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults aged 18–25 are also more likely to use illicit stimulants and to engage in nonmedical use of prescription stimulants than their straight peers.29,30 Further research is needed to understand the mechanisms underlying these disparities, including the possible impacts of social stressors, academic pressure, and peer use, among other potential factors.

While much stimulant research on young adults focuses on college students, some key differences exist between 18–25 year-olds who are in and out of college. Notably, 18–25 year-olds who do not attend college have more than twice the rate of methamphetamine use.11,31 In 2018, college students were more likely than their noncollege attending peers to use prescription stimulants and cocaine, although, in 2020, nonmedical prescription stimulant use was comparable between the two groups, and noncollege respondents reported significant higher cocaine use.11,31 The pandemic may have contributed to these shifts in use between young adults who attend college and those who do not. Further research is needed to explore the different factors that influence stimulant use for young adults in these unique social and economic contexts.

Polysubstance Use and Overdose:

The use of stimulants in combination with other drugs—that is, polysubstance use—is also rising and places youth at greater risk for overdose than use of a single substance. The current stimulant epidemic is closely tied to the ongoing opioid epidemic,32 with some individuals reporting using stimulants to balance out the sedative effects of opioids or to manage withdrawal symptoms.33 In 2017, 50.3% of psychostimulant-involved overdoses also involved opioids.24 Rates of polysubstance-involved overdose are rising rapidly among youth. From 2010 to 2018, opioid overdose deaths involving stimulants increased 351% among adolescents aged 13–25.34 More than half of youth opioid overdose deaths in 2018 involved another substance, and one-third involved stimulants, with cocaine being the most commonly involved substance (other than opioids).34 From 2016–2017, deaths involving cocaine and synthetic opioids increased by 50% among youth aged 15–19 and 64.3% among those aged 20–24; deaths involving psychostimulants and synthetic opioids increased by 150% for those aged 20–24.24 A study of those treated for polysubstance overdoses involving methamphetamine and opioids in Oregon found that patients who had also used methamphetamine tended to be significantly younger than those using only opioids, indicating that combined use may be a particular risk for youth.35

While co-use of stimulants and opioids is undoubtedly rising, factors leading to polysubstance use remain underexplored. One qualitative study found that participants reported using methamphetamine in addition to heroin because they believed it reduced their risk of overdosing or would curb their cravings enough to stop using heroin, although they ultimately continued using both.33 Some participants specifically used methamphetamine to counter the sedative effects of heroin or to reduce withdrawal symptoms. The few qualitative studies exploring reasons for co-use have typically included only adults, often with a focus on individuals with a primary opioid use disorder.36 Little work has explored polysubstance use in youth or pathways from stimulant use to co-use with opioids, and further research is critically needed on this topic. With stimulant use on the rise in adults, it is also crucial to understand the relationship between use during adolescence and subsequent use during adulthood.

Harms of Illicit Stimulant Use

While national efforts to reverse the overdose crisis have focused on opioids, more recently rising rates of stimulant overdose and associated harms have received much less attention. From April 2016 through September 2019, stimulant overdoses increased by 2.3% per quarter among youth age 15–24, mirroring a similar rise among suspected heroin overdoses of 3.3% per quarter.25 Between 2006 and 2016, emergency room visits involving psychostimulants increased by an average of 13.9% per year among all ages.24 Among youth, nonfatal ED visits for stimulant overdoses increased by 9.4% for 15–19 year olds and 9.9% among 19–24 year olds between 2015 and 2016.24 Between the years of 2012 and 2018, cocaine-related mortality increased threefold and psychostimulant-related mortality increased fivefold.32

In addition to risk for overdose, stimulant use is associated with other potential harms. Cocaine and methamphetamine can precipitate psychosis and other behavioral and emotional disturbances.37,38 Both have significant and potentially lethal effects on the cardiovascular system, increasing the risk of fatal cardiac events and heart failure.39–42 Both cocaine and methamphetamine can be injected, placing youth at risk for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis C virus, skin/soft tissue infections, and endocarditis.43,44 These risks highlight the urgent need for developmentally appropriate harm reduction services for youth. Additionally, stimulants are often used for so-called “chem sex”, or sex while using substances,45 and research suggests that individuals engaging in chem sex are less likely to use condoms.46 Chem sex is most common among men who have sex with men, which may relate to the known higher rates of stimulant use in this population.29 Using stimulants in combination with amyl-nitrate, an inhaled drug favored for its brief high and relaxation effects on the anal sphincter that is often used in party and sexual settings, is associated with a greater likelihood of engaging in risk behaviors leading to HIV infection47 and can lead to serious cardiovascular consequences. In addition to these physical health risks, illicit stimulant use is also associated with poor mental health outcomes48 and lower economic participation.49

Epidemiology of Nonmedical Prescription Stimulant Use:

While illicit stimulant use is on the rise among youth, prescription stimulant use remains the most common way that youth misuse stimulants. Given the ubiquity of prescription stimulants, youth have easier access to these substances and may view them as less dangerous than illicit substances, although they still carry significant risks. Medications such as amphetamine-dextroamphetamine (commonly known by one of its brand names, Adderall) and methylphenidate (Ritalin), are commonly used for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Between 2005 and 2014, ADHD diagnoses rose twofold in the United States from a prevalence of 6.8% to 14.4%, along with a similar increase in the number of prescriptions written for stimulants in the US.50,51 It is critical that youth receive treatment for ADHD, including use of prescription stimulants when indicated; nonetheless, the increased availability of prescription stimulants may also contribute to risk for diversion and misuse.

In 2020, 7.3% of high school seniors reported ever having misused an amphetamine (4.3% in the past year), and 4.4% and 1.7% had ever engaged in nonmedical use of Adderall and Ritalin, respectively.17 College-age young adults have even higher rates of nonmedical prescription stimulant use, and report reasons for use including perceived academic benefits, to attain a high, and to potentiate the effects of alcohol.10,52 Nonmedical prescription stimulant use has historically been most prevalent among 18–25 year-olds who attend college due to the touted academic benefits, but in 2020 both college students and non-college attending same age youth reported similar rates (6.5% and 6.3%, respectively)11. Seventh through 12th grade students report similar reasons for misusing prescription stimulants, including to improve concentration and alertness, to improve grades, to get high, and to counteract the effects of other drugs.53

Harms of Prescription Stimulant Misuse:

Though they can be safely used under the care of a physician, prescription stimulants are associated with significant risk when used for recreational or nonmedical reasons. While many youth report misusing prescription stimulants for their perceived academic benefit, no clear benefit has been established outside treatment for ADHD; in fact, college students who use prescription stimulants not prescribed to them report poorer academic performance, although this may represent a greater likelihood of stimulant initiation among already lower-performing students.54 Nonmedical use of prescription stimulants has also been linked to the misuse of other drugs, including alcohol, marijuana, ecstasy, and cocaine; however, causal pathways have yet to be fully described.54 The co-use of prescription stimulants and alcohol among college students has also been associated with increased alcohol and drug-related harms compared to using alcohol alone.55 While some data suggest that individuals prescribed stimulants starting in high school may be more likely to misuse alcohol and other drugs, little is known about whether or not there may be a pathway from prescription stimulant to illicit stimulant use56. Additional research is urgently needed to explore potential pathways between prescription and illicit stimulant use.

Diversion, or the giving or selling of a prescription stimulant to someone not prescribed it, is the primary way that youth acquire prescription stimulants for nonmedical use. Various studies have measured rates of diversion of prescription stimulants, with the majority of youth reporting getting stimulants from friends or family.57–59 While diversion is well-documented, reasons for it and preventive strategies have not been adequately elucidated and implemented. Some work has examined risk factors for stimulant diversion, and finds that youth aged 16–18 living in rural areas are most likely to report diverting prescription stimulants.60 Diversion is also very common among college students, with studies reporting a significant range in frequency of the behavior, from 16.7%57 of college students prescribed ADHD medication to over 58%.61

There are several recommended methods of reducing prescription stimulant diversion, including medication contracts, distributing educational materials to patients and families, and referring to treatment when a stimulant use disorder is suspected; however, the majority of clinicians report that they rarely engage in these practices, and many clinicians believe these strategies to be ineffective.62 A 2020 study found that a primary care-based intervention that trained providers on brief patient education and counseling, diversion prevention strategies, and medication monitoring significantly reduced rates of diversion among college students with ADHD, although the overall effect was small.57 More research is needed on the efficacy and implementation of current approaches to prevent the diversion of prescription stimulants and to investigate newer, potentially more effective interventions.

Factors Influencing Illicit and Nonmedical Prescription Stimulant Use Initiation:

Several individual-level factors have been associated with stimulant use. Earlier initiation of use of other substances is associated with earlier initiation of stimulant use.63 Additional research has explored factors influencing the initiation of other drugs and may point to factors that should be further explored for their potential relationship to initiating stimulant use. For example, personality characteristics, including higher levels of hopelessness and sensation seeking are associated with a greater likelihood of any substance use.64 Peer use of crack cocaine is also associated with youths’ use of stimulants.65

Parent-level factors are also known to be associated with the likelihood of youth initiating substance use. Parental substance use, maternal depression, and lower levels of parental involvement with kindergarten-aged children are associated with increased odds of earlier onset of first substance use.66 While parental pressure to perform well in school is hypothesized to be related to adolescent misuse of prescription stimulants, higher levels of parental monitoring are associated with lower levels of both prescription opioid and prescription stimulant misuse.67 Earlier onset crack-cocaine use was found in a Brazilian study to be associated with paternal alcohol problems, maternal relationship conflicts, and having experienced an episode of extremely severe maltreatment during childhood or adolescence.65 Additionally, recent research has demonstrated a link between parental opioid use and adolescent use,68 but further work is needed to determine if this relationship exists for stimulant use.

Potential Pathway from Prescription to Illicit Stimulant Use

Prescription stimulant misuse is more common than misuse of illicit stimulants, especially among youth, but there is currently little evidence on the potential progression from nonmedical use of prescription to use of illicit stimulants—an area needing urgent study. Nonmedical prescription stimulant use among youth has been linked to use of other substances, including cocaine,54 but a clear causal relationship has not been established. Some data suggest that misuse of prescription stimulants occurs in the context of individuals already using other substances, rather than serving a role as a so-called “gateway drug”.69 The opioid epidemic has demonstrated that misuse of prescription drugs may later develop into using illicit drugs in the same class,70 but research has yet to establish a similar relationship with stimulants. Because youth are more likely to initiate nonmedical misuse of prescription stimulants than illicit stimulants,10,60 elucidating potential pathways to use of more dangerous and potentially deadly drugs is crucial. More research into this topic may also identify potential points of intervention before illicit use starts.

Treatment Strategies for Stimulant Use Disorders:

Another important concern regarding stimulant use in youth is the lack of treatment strategies for stimulant use disorder. While multiple treatment options exist for opioid use disorder and have been approved for youth,71,72 no medications are currently US Food and Drug Administration-approved for stimulant use disorders. The combination of bupropion and naltrexone recently demonstrated efficacy in treating methamphetamine use disorder in adults with a treatment effect of 11.1 percentage points.73 Other medications that have been studied include bupropion monotherapy, naltrexone monotherapy, mirtazapine, mood stabilizers and other anticonvulsant medications, among other medications.74 None have been exclusively studied in youth.

Evidence is also limited on behavioral interventions for stimulant use disorder. A 2020 systematic review found that, of 11 interventions analyzed, only contingency management, a behavioral intervention in which participants receive something of value (such as a gift card) as a reward for negative drug tests, was found to be effective.75 Of the studies reviewed, however, participants averaged approximately age 35, and no trials focused on behavioral interventions among adolescents. Further, while methamphetamine use is growing at a faster rate than cocaine use, the majority of the studies on behavioral interventions for stimulant use disorder focused on cocaine75. Even fewer focused on amphetamines or other prescription stimulants. Additionally, no specific therapies exist for co-occurring stimulant and opioid use disorders, despite one-third of those with opioid use disorder reporting stimulant use.76 Limited evidence suggests that internet-based interventions may be effective for opioid use disorder or even polysubstance use disorders, but these studies did not show internet interventions to be effective for stimulant use disorders and focused only on adults.77 Given the dearth of evidence-based pharmacotherapy and behavioral interventions, clinicians caring for youth with a stimulant use disorder should consider referral to an addiction specialist where available.

Conclusion

Nonmedical stimulant use, including the use of prescription and illicit stimulants, is on the rise among youth, along with the serious consequences, including overdose, other medical harms, psychiatric harms, and long-term sequelae of substance use. As rates of use among adolescents and young adults climb, research and clinical knowledge has yet to catch up (Table 1). Most stimulant research focuses exclusively on adults; therefore, little is known about how to prevent and treat stimulant use in youth, how youth are using stimulants, and if there are pathways from nonmedical prescription use to the use of illicit stimulants or polysubstance use. While some disparities in stimulant use have been recognized, little research has explored the reasons for different use among demographic groups. Adolescents and young adults deserve particular consideration in research, given that adolescence is a common time of substance use initiation and younger onset of use increases the risk of lifetime use and use disorders. Research is needed to better understand how stimulant use develops to prevent use in the first place, support youth who are beginning to use before they develop use disorders, and prevent the long-term harms associated with stimulant use.

Table 1:

Key areas for additional research.

| Relationship between adolescent stimulant misuse and future substance use in adulthood |

| Mechanisms underlying disparities in stimulant misuse |

| Factors influencing stimulant misuse for young adults who attend college and same-age peers who do not attend college |

| Polysubstance use in youth |

| Pathways toward polysubstance use |

| Long-term impacts of stimulant misuse during youth |

| Potential pathways between prescription and illicit stimulant misuse |

| Approaches to prevent prescription stimulant diversion |

| Impact of parental and peer stimulant use on youth stimulant use behaviors |

| Treatment strategies for stimulant misuse and stimulant use disorders in youth |

Funding Source:

National Institute on Drug Abuse (K23DA045085): Hadland

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose. The funder/sponsor did not participate in the work.

References:

- 1.Products - Vital Statistics Rapid Release - Provisional Drug Overdose Data. Published August 5, 2021. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm

- 2.Austic EA. Peak ages of risk for starting nonmedical use of prescription stimulants. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;152:224–229. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.03.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The TEDS Report: Age of Substance Use Initiation among Treatment Admissions Aged 18 to 30. Published online 2014:6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levy SJL, Williams JF, COMMITTEE ON SUBSTANCE USE AND PREVENTION. Substance Use Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment. Pediatrics. 2016;138(1):e20161211. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen CY, Storr CL, Anthony JC. Early-onset drug use and risk for drug dependence problems. Addict Behav. 2009;34(3):319–322. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.10.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rasmussen N America’s First Amphetamine Epidemic 1929–1971. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(6):974–985. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.110593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crack vs. Heroine Project: Racial Double Standard in Drug Laws Persists Today. Equal Justice Initiative. Published December 9, 2019. Accessed November 21, 2021. https://eji.org/news/racial-double-standard-in-drug-laws-persists-today/

- 8.Watkins BX, Fullilove RE, Fullilove MT. Arms against Illness: Crack Cocaine and Drug Policy in the United States. Health Hum Rights. 1996;2:42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watkins BX, Fullilove MT. The Crack Epidemic and the Failure of Epidemic Response. Temple Polit Civ Rights Law Rev. 2000;10:371. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Section 1 PE Tables – Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables, SAMHSA, CBHSQ. Accessed November 16, 2021. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt35323/NSDUHDetailedTabs2020/NSDUHDetailedTabs2020/NSDUHDetTabsSect1pe2020.htm

- 11.Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, & Miech RA Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2020: Volume II, College students and adults ages 19–60. Ann Arbor Inst Soc Res Univ Mich. Published online 2021. Accessed June 23, 2022. http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-vol2_2020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnston LD, Miech RA, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, & Patrick ME Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use 1975–2020: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor Inst Soc Res Univ Mich. Published online 2021. Accessed June 29, 2022. http://www.monitoringthefuture.org//pubs/monographs/mtf-overview2020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schneider KE, Krawczyk N, Xuan Z, Johnson RM. Past 15-year trends in lifetime cocaine use among US high school students. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;183:69–72. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.10.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzales R, Mooney L, Rawson R. The Methamphetamine Problem in the United States. Annu Rev Public Health. 2010;31:385–398. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wakeman S, Flood J, Ciccarone D. Rise in Presence of Methamphetamine in Oral Fluid Toxicology Tests Among Outpatients in a Large Healthcare Setting in the Northeast. J Addict Med. 2021;15(1):85–87. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonzales R, Ang A, McCann MJ, Rawson RA. An emerging problem: methamphetamine abuse among treatment seeking youth. Subst Abuse. 2008;29(2):71–80. doi: 10.1080/08897070802093312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abuse NI on D. Monitoring the Future Study: Trends in Prevalence of Various Drugs. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Published December 17, 2020. Accessed November 13, 2021. https://www.drugabuse.gov/drug-topics/trends-statistics/monitoring-future/monitoring-future-study-trends-in-prevalence-various-drugs [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palamar JJ, Le A, Carr TH, Cottler LB. Shifts in drug seizures in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;221:108580. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stimulant Deaths on the Rise, Compounded by Rise in Synthetic Opioids. NIHCM. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://nihcm.org/publications/stimulant-deaths-on-the-rise-compounded-by-rise-in-synthetic-opioids [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yimsaard P, Maes MM, Verachai V, Kalayasiri R. Pattern of Methamphetamine Use and the Time Lag to Methamphetamine Dependence. J Addict Med. 2018;12(2):92–98. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alcover KC, Thompson CL. Patterns of Mean Age at Drug Use Initiation Among Adolescents and Emerging Adults, 2004–2017. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(7):725–727. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.6235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age of onset of drug use and its association with DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence: Results from the national longitudinal alcohol epidemiologic survey. J Subst Abuse. 1998;10(2):163–173. doi: 10.1016/S0899-3289(99)80131-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Berglund PA, et al. Patterns and predictors of treatment seeking after onset of a substance use disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(11):1065–1071. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.11.1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoots B, Vivolo-Kantor A, Seth P. The rise in non-fatal and fatal overdoses involving stimulants with and without opioids in the United States. Addiction. 2020;115(5):946–958. doi: 10.1111/add.14878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roehler DR, Olsen EO, Mustaquim D, Vivolo-Kantor AM. Suspected Nonfatal Drug-Related Overdoses Among Youth in the US: 2016–2019. Pediatrics. 2021;147(1). doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-003491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newcomb ME, Birkett M, Corliss HL, Mustanski B. Sexual Orientation, Gender, and Racial Differences in Illicit Drug Use in a Sample of US High School Students. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(2):304–310. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Published online 2020:156. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johns MM, Lowry R, Rasberry CN, et al. Violence Victimization, Substance Use, and Suicide Risk Among Sexual Minority High School Students — United States, 2015–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(43):1211–1215. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6743a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Philbin MM, Greene ER, Martins SS, LaBossier NJ, Mauro PM. Medical, Nonmedical, and Illegal Stimulant Use by Sexual Identity and Gender. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59(5):686–696. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.05.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fairman RT, Vu M, Haardörfer R, Windle M, Berg CJ. Prescription stimulant use among young adult college students: Who uses, why, and what are the consequences? J Am Coll Health J ACH. 2021;69(7):767–774. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2019.1706539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schulenberg JE, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Miech RA & Patrick ME Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2018: Volume II, College students and adults ages 19–60. Ann Arbor Inst Soc Res Univ Mich. Published online 2019. Accessed June 23, 2022. http://www.monitoringthefuture.org//pubs/monographs/mtf-vol2_2018.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ciccarone D The rise of illicit fentanyls, stimulants and the fourth wave of the opioid overdose crisis. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2021;34(4):344–350. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lopez AM, Dhatt Z, Howe M, et al. Co-use of methamphetamine and opioids among people in treatment in Oregon: A qualitative examination of interrelated structural, community, and individual-level factors. Int J Drug Policy. 2021;91:103098. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.103098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lim JK, Earlywine JJ, Bagley SM, Marshall BDL, Hadland SE. Polysubstance Involvement in Opioid Overdose Deaths in Adolescents and Young Adults, 1999–2018. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(2):194–196. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.5035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Study Finds High Rates of Combined Opioids and Methamphetamine Use in Oregon | NDEWS l National Drug Early Warning System l University of Maryland. Accessed September 8, 2021. https://stagebsos6.umd.edu/feature/study-finds-high-rates-combined-opioids-and-methamphetamine-use-oregon

- 36.Ellis MS, Kasper ZA, Cicero TJ. Twin epidemics: The surging rise of methamphetamine use in chronic opioid users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;193:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.08.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zweben JE, Cohen JB, Christian D, et al. Psychiatric symptoms in methamphetamine users. Am J Addict. 2004;13(2):181–190. doi: 10.1080/10550490490436055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morton WA. Cocaine and Psychiatric Symptoms. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;1(4):109–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaye S, McKetin R, Duflou J, Darke S. Methamphetamine and cardiovascular pathology: a review of the evidence. Addict Abingdon Engl. 2007;102(8):1204–1211. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01874.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Autopsies reveal how meth hurts the heart. American Heart Association. Accessed September 8, 2021. https://newsroom.heart.org/news/autopsies-reveal-how-meth-hurts-the-heart

- 41.Zhao SX, Deluna A, Kelsey K, et al. Socioeconomic Burden of Rising Methamphetamine-Associated Heart Failure Hospitalizations in California From 2008 to 2018. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2021;14(7):e007638. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.007638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schwartz BG, Rezkalla S, Kloner RA. Cardiovascular Effects of Cocaine. Circulation. 2010;122(24):2558–2569. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.940569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lyss SB, Buchacz K, McClung RP, Asher A, Oster AM. Responding to Outbreaks of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Among Persons Who Inject Drugs-United States, 2016–2019: Perspectives on Recent Experience and Lessons Learned. J Infect Dis. 2020;222(Suppl 5):S239–S249. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nerlander LMC, Hoots BE, Bradley H, et al. HIV infection among MSM who inject methamphetamine in 8 US cities. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;190:216–223. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.06.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tomkins A, George R, Kliner M. Sexualised drug taking among men who have sex with men: a systematic review. Perspect Public Health. 2019;139(1):23–33. doi: 10.1177/1757913918778872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maxwell S, Shahmanesh M, Gafos M. Chemsex behaviours among men who have sex with men: A systematic review of the literature. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;63:74–89. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ostrow DG, Plankey MW, Cox C, et al. Specific sex drug combinations contribute to the majority of recent HIV seroconversions among MSM in the MACS. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2009;51(3):349–355. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a24b20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Degenhardt L, Hall W. Addiction 1: Extent of illicit drug use and dependence, and their contribution to the global burden of disease. Lancet Lond. 2012;379(9810):55–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.DeSimone J Illegal Drug Use and Employment. J Labor Econ. 2002;20(4):952–977. doi: 10.1086/342893 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Davidovitch M, Koren G, Fund N, Shrem M, Porath A. Challenges in defining the rates of ADHD diagnosis and treatment: trends over the last decade. BMC Pediatr. 2017;17:218. doi: 10.1186/s12887-017-0971-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Piper BJ, Ogden CL, Simoyan OM, et al. Trends in use of prescription stimulants in the United States and Territories, 2006 to 2016. PLOS ONE. 2018;13(11):e0206100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Teter CJ, McCabe SE, Cranford JA, Boyd CJ, Guthrie SK. Prevalence and motives for illicit use of prescription stimulants in an undergraduate student sample. J Am Coll Health J ACH. 2005;53(6):253–262. doi: 10.3200/JACH.53.6.253-262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Boyd CJ, McCabe SE, Cranford JA, Young A. Adolescents’ Motivations to Abuse Prescription Medications. Pediatrics. 2006;118(6):2472–2480. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McCabe SE, Knight JR, Teter CJ, Wechsler H. Non-medical use of prescription stimulants among US college students: prevalence and correlates from a national survey. Addiction. 2005;100(1):96–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.00944.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McCabe SE, Cranford JA, Morales M, Young A. Simultaneous and concurrent polydrug use of alcohol and prescription drugs: prevalence, correlates, and consequences. J Stud Alcohol. 2006;67(4):529–537. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kaloyanides KB, McCabe SE, Cranford JA, Teter CJ. Prevalence of Illicit Use and Abuse of Prescription Stimulants, Alcohol, and Other Drugs Among College Students: Relationship with Age at Initiation of Prescription Stimulants. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27(5):666–674. doi: 10.1592/phco.27.5.666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Molina BSG, Kipp HL, Joseph HM, et al. Stimulant Diversion Risk Among College Students Treated for ADHD: Primary Care Provider Prevention Training. Acad Pediatr. 2020;20(1):119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2019.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Poulin C From attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder to medical stimulant use to the diversion of prescribed stimulants to non-medical stimulant use: connecting the dots. Addiction. 2007;102(5):740–751. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01758.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Section 6 PE Tables – Results from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables, SAMHSA, CBHSQ. Accessed September 9, 2021. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt29394/NSDUHDetailedTabs2019/NSDUHDetTabsSect6pe2019.htm

- 60.Cottler LB, Striley CW, Lasopa SO. Assessing prescription stimulant use, misuse and diversion among youth 10 to 18 years of age. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2013;26(5):511–519. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283642cb6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gallucci AR, Martin RJ, Usdan SL. The diversion of stimulant medications among a convenience sample of college students with current prescriptions. Psychol Addict Behav. 2015;29(1):154–161. doi: 10.1037/adb0000012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Colaneri N, Keim S, Adesman A. Physician practices to prevent ADHD stimulant diversion and misuse. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;74:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brecht ML, Greenwell L, Anglin MD. Substance use pathways to methamphetamine use among treated users. Addict Behav. 2007;32(1):24–38. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Malmberg M, Overbeek G, Monshouwer K, Lammers J, Vollebergh WAM, Engels RCME. Substance use risk profiles and associations with early substance use in adolescence. J Behav Med. 2010;33(6):474–485. doi: 10.1007/s10865-010-9278-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Perrenoud LO, Oikawa KF, Williams AV, et al. Factors associated with crack-cocaine early initiation: a Brazilian multicenter study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10769-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kaplow JB, Curran PJ, Dodge KA. Child, Parent, and Peer Predictors of Early-Onset Substance Use: A Multisite Longitudinal Study. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2002;30(3):199–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Donaldson CD, Nakawaki B, Crano WD. Variations in parental monitoring and predictions of adolescent prescription opioid and stimulant misuse. Addict Behav. 2015;45:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.01.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Griesler PC, Hu MC, Wall MM, Kandel DB. Nonmedical Prescription Opioid Use by Parents and Adolescents in the US. Pediatrics. 2019;143(3):e20182354. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sweeney CT, Sembower MA, Ertischek MD, Shiffman S, Schnoll SH. Nonmedical Use of Prescription ADHD Stimulants and Preexisting Patterns of Drug Abuse. J Addict Dis. 2013;32(1):1–10. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2012.759858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Abuse NI on D. Prescription opioid use is a risk factor for heroin use. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Published October 1, 2015. Accessed September 8, 2021. https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/prescription-opioids-heroin/prescription-opioid-use-risk-factor-heroin-use [Google Scholar]

- 71.Borodovsky JT, Levy S, Fishman M, Marsch LA. Buprenorphine treatment for adolescents and young adults with opioid use disorders: a narrative review. J Addict Med. 2018;12(3):170–183. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Carney BL, Hadland SE, Bagley SM. Medication Treatment of Adolescent Opioid Use Disorder in Primary Care. Pediatr Rev. 2018;39(1):43–45. doi: 10.1542/pir.2017-0153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Trivedi MH, Walker R, Ling W, et al. Bupropion and Naltrexone in Methamphetamine Use Disorder. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(2):140–153. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2020214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Coffin PO, Santos GM, Hern J, et al. Effects of Mirtazapine for Methamphetamine Use Disorder Among Cisgender Men and Transgender Women Who Have Sex With Men: A Placebo-Controlled Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(3):246–255. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ronsley C, Nolan S, Knight R, et al. Treatment of stimulant use disorder: A systematic review of reviews. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(6):e0234809. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0234809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liu MT. Pharmacotherapy treatment of stimulant use disorder. Ment Health Clin. 2021;11(6):347–357. doi: 10.9740/mhc.2021.11.347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Boumparis N, Karyotaki E, Schaub MP, Cuijpers P, Riper H. Internet interventions for adult illicit substance users: a meta-analysis. Addiction. 2017;112(9):1521–1532. doi: 10.1111/add.13819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]