Abstract

Background:

As the population ages, clinicians increasingly encounter ischemic heart disease in patients with underlying dementia. Therefore, we quantified differences in in-hospital adverse events and 30-day readmission rates among patients with and without dementia undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Methods:

Using the National Readmissions Database 2017–2018, we identified 755,406 index hospitalizations in which PCI was performed, of which 17,309 (2.3%) had a diagnosis of dementia. After propensity score-matching patients with and without dementia, we assessed 30-day readmission and in-hospital adverse events by Cox proportional hazards and logistic regression modeling and compared them with those of other common cardiac (pacemaker placement [PP]) and non-cardiac (hip replacement surgery [HRS]) procedures.

Results:

Thirty-day readmission was significantly higher in patients with dementia than patients without dementia (hazards ratio [HR] 1.67, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.60–1.74). Patients with dementia also experienced higher odds of delirium (odds ratio [OR] 4.37, CI 3.69–5.16), in-hospital mortality (OR 1.15, CI 1.01–1.30), cardiac arrest (OR 1.19, CI 1.01–1.39), acute kidney injury (OR 1.30, CI 1.21–1.39), and fall (OR 2.51, CI 2.06–3.07). On multivariable Cox modeling, dementia independently predicted 30-day readmission (HR 1.14, CI 1.07–1.20). The higher readmission risk with PCI (11%) among those with dementia was similar to that of patients undergoing PP (10%), but lower than in those undergoing HRS (41%).

Conclusion:

Patients with dementia who undergo PCI experience significantly increased rates of in-hospital delirium, mortality, kidney injury, falls, and 30-day readmission. These adverse outcomes should be considered during shared decision-making with patients and their families.

Keywords: Dementia, PCI, coronary, readmission

Introduction

Ischemic heart disease is exceedingly common among older adults, with nearly a quarter million percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) performed on adults aged 65 and above annually1. Dementia, which is one of the most common causes of morbidity and mortality in older adults, doubles in prevalence every five years after the age of 602. As the population ages, clinicians are increasingly faced with the concurrent presentation of ischemic heart disease in patients with dementia. By one estimate from the Public Health Agency of Canada, the prevalence of coexisting ischemic heart disease and dementia has been estimated at 2.8% of individuals ≥65 year old.3 Whether presenting electively or for acute myocardial infarction (AMI), patients with dementia are less likely to undergo revascularization.4, 5 PCI may confer a benefit in terms of survival in patients with dementia presenting with AMI6, while treatment goals are squarely centered around symptomatic benefit in most with stable ischemic heart disease (SIHD), yet patients with dementia are much less likely to undergo PCI compared with patients without dementia4, 7, 8. Furthermore, patients with dementia have been excluded from most trials of PCI, often through exclusion by age, and most observational studies of PCI do not consider dementia in their analyses9, 10. This represents a knowledge gap that cannot be ignored, as the prevalence of dementia is projected to rise from 46.8 million individuals in 2015 to 74.7 million individuals in 203011.

Existing observational analyses of PCI for coronary heart disease in patients with dementia are limited and have focused on survival after PCI for AMI in this population4, 7, 8. However, shared decision-making with older adult patients with dementia and their families requires realistic expectations around short-term safety, risks of inpatient complications, and other key influences on quality of life, such as readmissions that directly reduce days alive and out of the hospital. Addressing predictors of readmission is particularly important in older adults with dementia because readmissions predispose patients to delirium, deconditioning, and increased mortality12–17.

Contemporary in-hospital risks and 30-day readmission rates for patients with dementia undergoing PCI are unknown. Thus, we quantified differences in in-hospital events and readmission rates among patients with and without dementia undergoing PCI. We then compared PCI outcomes among patients with dementia to those without dementia and placed those results in the context of other commonly performed procedures in this age group.

Methods

Data Source

The National Readmissions Database (NRD) is a database designed for readmission analyses by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality as part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP)18. The NRD is derived from the State Inpatient Databases, which contain unique and verified patient linkage numbers used to track each patient across different hospitals within a state while strictly protecting patient privacy. Since only 28 states contribute to the NRD, and 80% of hospitals in these states participate, discharge weights are applied through poststratification according to hospital characteristics and discharge characteristics in order to accurately represent hospital and discharge types. Hospital characteristics are delineated in the NRD’s NRD_STRATUM variable, which includes the hospital’s census region, urban/rural location, teaching status, size based on the number of beds, and ownership/control18. Information on hospital characteristics was obtained from the American Hospital Association’s Annual Survey of Hospitals19. Strata are collapsed prior to the weight calculations to ensure that at least two sampled hospitals and at least 100 discharges were in each stratum. After application of weights to 15 million discharges, the NRD can estimate approximately 35 million discharges, representing national hospital readmissions regardless of expected payer18. The NRD provides verified patient linkage numbers that identifies discharges belonging to the same patient and timing between admissions, allowing one to calculate individual readmission rates. Using the NRD, we identified index hospitalizations between 2017 and 2018 in which PCI was performed. Our study was exempt from institutional board review as our data was restricted to the NRD, a publicly available database with deidentified patient-level information. The data used in our study can be found at https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nrdoverview.jsp18.

Study Population and Variables

International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Procedure Coding System (ICD-10-PCS) codes were used to identify all index hospitalizations in which PCI, consisting of drug-eluting stent placement, bare-metal stent placement, and plain old balloon angioplasty, was performed. The indication for PCI was stratified into ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), unstable angina (UA), and stable ischemic heart disease (SIHD), the last of which was assumed if no diagnostic code for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) was present in both primary and secondary diagnoses as validated by previous studies1, 20, 21. Index hospitalizations for pacemaker placement or hip replacement surgery, two relatively common cardiac and non-cardiac procedures, were also identified for contextualization and sensitivity analysis. All the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) and ICD-10-PCS codes used in our study can be found in Supplementary Table 1. Patients 18 years and older who underwent PCI were stratified into two groups: those with and without dementia. Only discharges from January through November in each year were included to guarantee completeness of data on 30 days of follow-up after discharge. Discharges with missing information on demographics, census, and primary payer were excluded. For each patient, age, sex, comorbidities, hospital characteristics, primary payer, median income, and procedural data were extracted.

Study Outcomes

The primary outcome of interest was 30-day readmission for any cause. For each patient, only the first readmission within 30 days after discharge from index hospitalization was included. The causes of readmissions were divided into cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular causes. Cardiovascular causes were further classified into heart failure, myocardial infarction, stroke, arrhythmia, and other cardiovascular causes. Non-cardiovascular causes were further classified into acute kidney injury, gastrointestinal bleeding, electrolyte abnormality, sepsis, and other non-cardiovascular causes. Secondary outcomes of interest comprised of delirium, in-hospital mortality, cardiac arrest, cardiogenic shock, hypovolemic shock, intracranial hemorrhage, gastrointestinal bleeding, blood transfusion, acute kidney injury, fall in hospital, length of hospital stay at the index hospitalization.

Statistical Analysis

We applied discharge weights, using the DISCWT variable provided by the NRD, in all analyses to represent national estimates.22 This is done by multiplying DISCWT with its corresponding data entry. Percentages and means were used to summarize categorical and continuous variables, respectively. For comparison of continuous variables, Student’s t-test and the Wilcoxon rank sum test were used for parametric and non-parametric distributions, respectively. The Chi-squared test was used to compare categorical variables. Patients with and without dementia were propensity score-matched based on sex, age, comorbidities, hospital characteristics, primary payer, clinical presentation, and procedural information using the greedy nearest-neighbor method. Overlap plots and love plots were drawn to assess for adequate balance of covariates. Post-match absolute standardized differences below 10% were confirmed for all covariates to ensure negligible correlation23. Kaplan-Meier curves over 30 days were drawn to illustrate 30-day readmissions, after which the log-rank test was applied. A Cox proportional-hazards model was created to generate hazard ratios between patients with and without dementia for the primary endpoint. For secondary outcomes, logistic regression was performed to calculate odds ratios and linear regression was performed to calculate mean differences. Finally, multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression was performed to explore potential risk factors for 30-day readmission in all patients with candidate predictors determined based on clinical relevance. For the variable delirium, we additionally performed an analysis of interaction with discharge disposition (e.g. to skilled nursing facility) in association with 30-day readmission. Data mining, comparison of baseline characteristics, regression analyses, and Cox proportional-hazards model were conducted using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Propensity score-matching, Kaplan-Meier curves, and log-rank tests were performed using MatchIt, survival, and survminer packages in R version 4.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Baseline characteristics

In 2017 and 2018, PCI was performed in a total of 755,406 index hospitalizations (Supplementary Figure 1), of which 17,309 (2.3%) of the patients had a secondary diagnosis of dementia and 738,097 (97.7%) did not. Before propensity score-matching, the group with dementia had an average age of 78.8 years, with 42.9% being female; the group without dementia had an average age of 64.9 years, with 31.3% being female. Baseline characteristics showed that patients with dementia were older and had more comorbidities, heart failure, end-stage renal disease, deficiency anemia, malnutrition, and major depression (Table 1). The full table including hospital characteristics, primary payer, and median income quartile is shown in Supplementary Table 2. However, they were less frequently obese and less frequently had a history of past or recent smoking. After propensity score matching, 17,309 and 17,187 patients with and without dementia were included, respectively. Propensity score matching adequately balanced the covariates between the two groups as demonstrated by the convergence of the overlap plot and the narrowing of the love plot (Supplementary Figures 2 and 3). All the following results are those of the propensity score-matched groups unless stated otherwise.

Table 1.

General characteristics of index hospitalizations for PCI stratified to dementia

| Before Matching | After Matching | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dementia(+) | Dementia(−) | ASD, % | Dementia(+) | Dementia(−) | ASD, % | |

| N (sample) | 9,505 | 402,605 | 9,505 | 9,505 | ||

| N (weighted) | 17,309 | 738,097 | 17,309 | 17,187 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Sex, % | 23.4 | 0.2 | ||||

| Male | 57.1 | 68.7 | 57.1 | 57.0 | ||

| Female | 42.9 | 31.3 | 42.9 | 42.0 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Age, mean | 78.8 | 64.9 | 139.1 | 78.8 | 78.3 | 3.3 |

| 18–44 years, % | 0.2 | 4.9 | 0.2 | 0.2 | ||

| 45–64 years, % | 5.9 | 43.4 | 5.9 | 5.3 | ||

| 65–74 years, % | 20.3 | 28.4 | 20.3 | 21.1 | ||

| 74–85 years, % | 46.3 | 17.6 | 46.3 | 43.8 | ||

| ≥85 years, % | 27.3 | 5.7 | 27.3 | 29.6 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Comorbidities, % | ||||||

| Smoking | 38.6 | 51.6 | 26.6 | 38.6 | 38.4 | 0.5 |

| Hypertension | 85.4 | 79.2 | 17.6 | 85.4 | 85.8 | 1.1 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 43.9 | 38.6 | 10.8 | 43.9 | 43.4 | 1.1 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 72.6 | 72.6 | 0.1 | 72.6 | 73.2 | 1.2 |

| Obesity | 11.7 | 21.8 | 31.3 | 11.7 | 11.6 | 0.5 |

| Heart failure | 42.3 | 25.3 | 34.5 | 42.3 | 41.1 | 2.5 |

| Valvular heart disease | 14.2 | 7.8 | 13.2 | 14.2 | 14.0 | 0.5 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 27.1 | 13.8 | 29.8 | 27.1 | 27.4 | 0.9 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 4.8 | 2.7 | 10.0 | 4.8 | 4.6 | 1.2 |

| Previous stroke | 20.6 | 7.6 | 32.2 | 20.6 | 18.3 | 5.5 |

| Previous PCI | 2.0 | 1.6 | 2.9 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 1.5 |

| Previous CABG | 11.1 | 9.3 | 5.6 | 11.1 | 11.1 | 0.1 |

| Previous pacemaker | 5.6 | 2.2 | 14.8 | 5.6 | 5.1 | 2.1 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 22.3 | 17.9 | 10.6 | 22.3 | 21.9 | 0.9 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 7.8 | 3.9 | 14.5 | 7.8 | 7.0 | 2.9 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 31.5 | 16.7 | 31.8 | 31.5 | 30.3 | 2.5 |

| End-stage renal disease | 3.4 | 2.4 | 5.0 | 3.4 | 3.3 | 0.2 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.2 |

| History of malignancy | 13.5 | 8.5 | 14.7 | 13.5 | 13.1 | 1.2 |

| Deficiency anemia | 5.6 | 2.5 | 11.9 | 5.6 | 4.7 | 1.6 |

| Malnutrition | 4.6 | 1.5 | 15.1 | 4.6 | 4.1 | 2.6 |

| Major depression | 1.1 | 0.4 | 6.6 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 2.8 |

|

| ||||||

| Clinical presentation, % | ||||||

| STEMI | 29.0 | 32.3 | 7.3 | 29.0 | 27.8 | 2.7 |

| NSTEMI | 45.4 | 40.0 | 10.8 | 45.4 | 45.7 | 0.6 |

| Unstable angina | 12.1 | 15.5 | 10.5 | 12.1 | 13.7 | 3.5 |

| Stable ischemic heart disease | 13.5 | 12.1 | 4.0 | 13.5 | 13.3 | 0.7 |

|

| ||||||

| Procedures, % | ||||||

| Drug-eluting stent | 84.4 | 89.3 | 13.5 | 84.4 | 85.7 | 3.6 |

| Bare-metal stent | 9.8 | 6.2 | 12.1 | 9.8 | 9.2 | 2.2 |

| Plain old balloon angioplasty | 12.3 | 10.7 | 4.9 | 12.3 | 11.7 | 2.0 |

| Intravascular ultrasound | 6.1 | 6.7 | 2.4 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 0.2 |

| Optical coherence tomography | 0.3 | 0.4 | 2.5 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 2.1 |

| Intra-aortic balloon pump | 4.3 | 3.4 | 4.6 | 4.3 | 4.0 | 1.6 |

| ECMO | 0.1 | 0.2 | 4.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| Renal replacement therapy | 3.3 | 2.3 | 5.5 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 0.4 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 8.7 | 5.2 | 12.7 | 8.7 | 8.3 | 1.5 |

Abbreviations: ASD = absolute standardized difference; CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; ECMO = extracorporeal membranous oxygenation; NSTEMI = non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI = ST-elevation myocardial infarction

Adverse outcomes at index hospitalization

At index hospitalizations in which PCI was performed, patients with dementia experienced higher odds of delirium (OR 4.37, 95% CI 3.69–5.16, p<0.01), in-hospital mortality (odds ratio [OR] 1.15, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.01–1.30, p=0.03), cardiac arrest (OR 1.19, 95% CI 1.01–1.39, p=0.04), blood transfusion (OR 1.17, 95% CI 1.00–1.36, p=0.05), acute kidney injury (OR 1.30, 95% CI 1.21–1.39, p<0.01), and fall in hospital (OR 2.51, 95% CI 2.06–3.07, p<0.01) (Table 2). Patients with dementia also experienced longer length of hospital stay (mean difference 1.43 days, 95% CI 1.22–1.64, p<0.01). We observed modest variability across different clinical presentations in the association between dementia status and clinical outcomes. Patients with dementia had higher odds of in-hospital mortality, hypovolemic shock, and AKI in STEMI; higher odds of AKI in NSTEMI; higher odds of in-hospital mortality in UA; and higher odds of AKI in SIHD (Supplementary Table 3). The odds of having delirium and a fall in the hospital were higher in patients with dementia regardless of clinical presentation.

Table 2.

Comparison of outcomes between patients with and without dementia after propensity score-matching

| Dementia(+) | Dementia(−) | OR (95% CI) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index Hospitalization | Delirium, % | 9.5 | 2.4 | 4.37 (3.69–5.16) | <0.001 |

| In-hospital mortality, % | 6.2 | 5.4 | 1.15 (0.01–1.30) | 0.030 | |

| Cardiac arrest, % | 4.1 | 3.5 | 1.19 (1.01–1.39) | 0.039 | |

| Cardiogenic shock, % | 8.6 | 8.0 | 1.09 (0.97–1.21) | 0.142 | |

| Hypovolemic shock, % | 0.9 | 0.6 | 1.42 (0.99–2.04) | 0.061 | |

| Intracranial hemorrhage, % | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.88 (0.53–1.46) | 0.622 | |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage, % | 2.8 | 2.5 | 1.12 (0.92–1.37) | 0.260 | |

| Blood transfusion, % | 4.7 | 4.0 | 1.17 (1.00–1.36) | 0.047 | |

| Acute kidney injury, % | 26.7 | 21.9 | 1.30 (1.21–1.39) | <0.001 | |

| Fall in hospital, % | 4.2 | 1.7 | 2.51 (2.06–3.07) | <0.001 | |

| Non-fatal complication*, % | 36.0 | 25.4 | 1.66 (1.55–1.77) | <0.001 | |

| Length of hospital stay, days | 6.6 ± 8.2 | 5.2 ± 6.6 | 1.43 (1.22–1.64) | <0.001 | |

|

| |||||

| 30-day Readmission | In-hospital mortality (%) | 6.0 | 5.6 | 1.08 (0.77–1.52) | 0.664 |

| Length of hospital stay, days | 4.9 ± 5.2 | 4.7 ± 4.8 | 0.21 ([−0.18]-0.60) | 0.141 | |

Non-fatal complication refers to delirium, survived cardiac arrest, cardiogenic shock, hypovolemic shock, intracranial hemorrhage, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, acute kidney injury, or fall in hospital which did not result in death

Abbreviations: PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention

Disposition after discharge

At discharge, patients with dementia were more frequently sent to a skilled nursing facility (30.1% vs 12.2%) or to home health care (23.1% vs 16.7%) after PCI compared with patients without dementia, who were more frequently discharged to home (69.9% vs 45.6%) (Supplementary Figure 4). Disposition from index hospitalization significantly differed by the presence of delirium. Across the entire cohort, just 27.8% of patients who experienced in-hospital delirium were discharged to home, compared with 59.7% of those who did not experience delirium. Almost half (41.7%) of patients with in-hospital delirium were discharged to skilled nursing facilities compared with just 27.8% of patients who were free of delirium. Even within the cohort of patients with dementia, patients who experienced delirium were more frequently sent to skilled nursing facilities compared with those who were free of delirium (43.5% vs 28.7%).

Thirty-day readmission

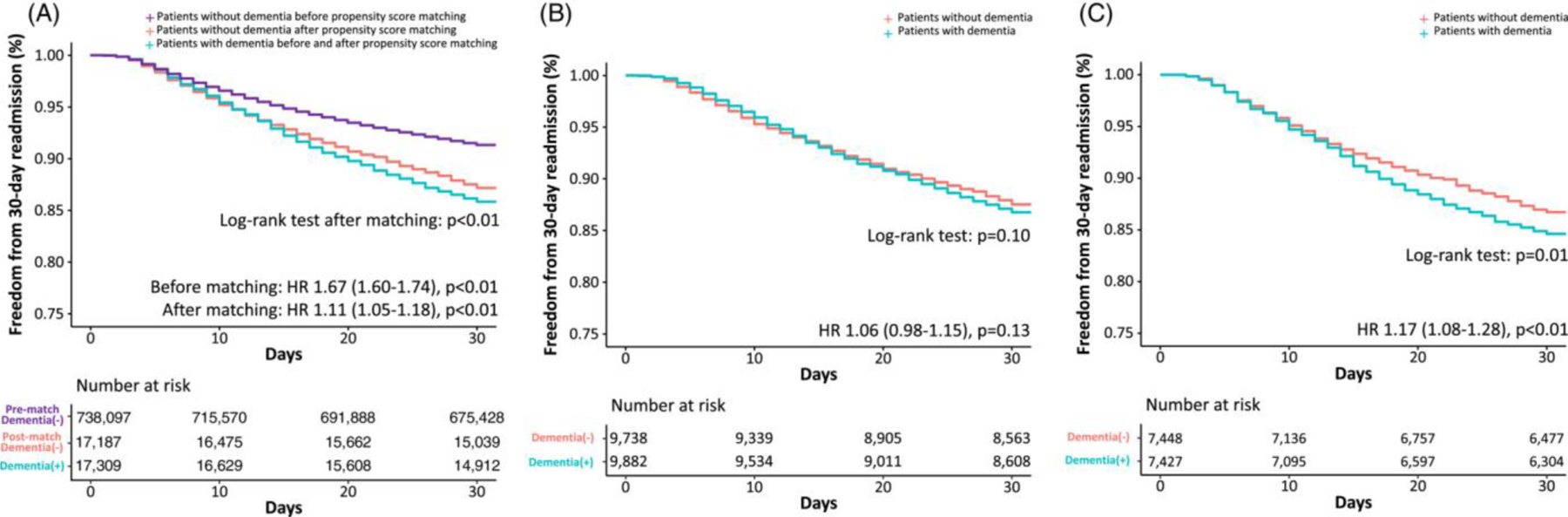

Before propensity score-matching, thirty-day readmission rates of patients with dementia following PCI were significantly higher than those without dementia (hazard ratio [HR] 1.67, 95% CI 1.60–1.74, p<0.01) (Figure 1). After propensity score matching, 13.8% of patients with dementia were readmitted within 30 days after undergoing PCI at index hospitalization compared with 12.5% of patients without dementia. Patients with dementia had a slightly higher hazard of 30-day readmission for any cause compared with those without dementia (HR 1.11, 95% CI 1.05–1.18, p<0.01). Results were similar in sensitivity analyses including patients ≥65 years and ≥75 years, but not in ≥85 years (Supplementary Figure 5). There was no difference in the hazard of 30-day readmission between male patients with and without dementia (HR 1.06, 95% CI 0.98–1.15, p=0.13) as opposed to a significant difference in female patients with and without dementia (HR 1.17, 95% CI 1.08–1.28, p<0.01). However, the test for interaction between sex and dementia was not significant (P-interaction=0.27).

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier curves of 30-day readmission in patients with and without dementia.

Kaplan-Meier curves show 30-day readmissions in all patients (Figure 1A), who were then stratified to male (Figure 1B) and female (Figure 1C) patients. A hazard ratio above 1 indicates that the hazard of 30-day readmission is higher in patients with dementia compared with those without dementia, and vice versa. The log-rank tests beneath the curves show the difference in the Kaplan-Meier curves between patients with and without dementia. In Figure 1A, the additional violet curve illustrates 30-day readmissions in patients without dementia prior to propensity score matching. In all figures, the red and blue curves represent 30-day readmissions in patients without dementia after propensity score matching and in patients with dementia (no change after propensity score matching), respectively.

Stratification to clinical presentation revealed that among patients who underwent PCI for NSTEMI, those with dementia had a higher hazard of 30-day readmission than those without dementia (HR 1.24, 95% CI 1.14–1.35, p<0.01) (Supplementary Figure 6). However, there was no difference in the hazard of 30-day readmission in patients with and without dementia in those who underwent PCI for STEMI (HR 0.98, 95% CI 0.88–1.10, p=0.73), UA (HR 1.08, 95% CI 0.92–1.27, p=0.36), and SIHD (HR 0.99, 95% CI 0.85–1.16, p=0.90). In patients with dementia, the most common cardiovascular cause of 30-day readmission was heart failure (14.4%), followed by myocardial infarction (9.4%) and arrhythmia (4.4%) (Supplementary Figure 7). Patients with dementia were more frequently admitted for non-cardiovascular causes (53.1%). In contrast, patients without dementia were more commonly admitted for cardiovascular causes (56.2%), with heart failure (18.4%) and myocardial infarction (10.2%) as the top 2 leading causes.

Comparison with other procedures

To provide additional clinical context to our findings, we repeated identical propensity score-matching and analyses for patients with and without dementia undergoing pacemaker placement or hip replacement surgery (Supplementary Tables 4-6 and Supplementary Figures 8-13). In patients with dementia, 30-day readmission rates were higher after PCI (13.8%) compared with after pacemaker placement (9.8%) or hip replacement surgery (10.8%). Similarly, the hazard of 30-day readmission was also greater after PCI when compared head-to-head with either pacemaker placement (HR 1.45, 95% CI 1.37–1.54, p<0.01) or hip replacement surgery (HR 1.32, 95% CI 1.25–1.38, p<0.01) (Figure 2). However, when patients with and without dementia were compared within the cohort who underwent the same procedure, the relative increase in the hazard of 30-day readmission in patients with dementia was greatest after hip replacement surgery (41%) compared with pacemaker placement (10%) or PCI (11%) (Central Illustration).

Figure 2. Potential risk factors of 30-day readmission in patients with dementia.

Potential risk factors of 30-day readmission in patients with dementia. A hazard ratio greater than 1 denotes association with 30-day readmission and vice versa. The vertical lines for each potential risk factor represent the odds ratio whereas the perpendicular horizontal line shows the 95% confidence interval. The plots in model 1 on the left (Figure 2A) include baseline characteristics and clinical presentation while those in model 2 on the right (Figure 2B) also include outcomes at the index hospitalization. Figure 2 only includes a subset of the variables in the multivariable model for display purposes. Please refer to Supplementary Figure 6 for complete results of the model.

Potential risk factors for readmission

We performed sequential multivariable Cox regression models, first including baseline and clinical presentation characteristics (model 1) and next with clinical outcomes during index hospitalization added to the first model (model 2) (Figure 3). Dementia was associated with increased hazard of 30-day readmission on both models (HR 1.13, 95% CI 1.06–1.20 for model 1 and HR 1.17, 95% CI 1.09–1.24 for model 2, respectively). Increasing age (per 10 years) and female sex were each independently associated with increased hazard of 30-day readmission in both models. Comorbidities independently associated with increased hazard of 30-day readmission included smoking, diabetes, heart failure, valvular heart disease, atrial fibrillation, peripheral artery disease, previous stroke, chronic pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, end-stage renal disease, and deficiency anemia. In terms of clinical presentation, STEMI was associated with increased hazard of 30-day readmission compared with SIHD, whereas unstable angina and NSTEMI did not. In the multivariable Cox regression model including clinical outcomes, delirium was not associated with increased hazard of 30-day readmission, but hypovolemic shock, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, need for blood transfusion, acute kidney injury, and fall in hospital were. Interaction analysis revealed an interaction between diagnosis of delirium and disposition to a skilled nursing facility (P-interaction<0.01) for the outcome of 30-day readmission. Longer length of hospital stay was associated with decreased hazard of 30-day readmission. Additional details of the multivariable Cox regression models are separately shown in Supplementary Figure 14.

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier curves of 30-day readmissions after PCI, pacemaker placement, and hip replacement surgery in patients with dementia.

Kaplan-Meier curves show 30-day readmissions after PCI (light red, dark red), pacemaker placement (light green, dark green), and hip replacement surgery (light blue, dark blue) in patients with and without dementia, respectively. Comparison of procedures represents head-to-head comparison of procedures in patients with dementia. Comparison within procedures represents comparison of patients with and without dementia within the cohort of patients who underwent each procedure. The numbers in the table showing number at risk are those for patients with dementia.

Abbreviations: HRS = hip replacement surgery; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; PP = pacemaker placement

Much like that seen following PCI, the odds of in-hospital delirium were markedly elevated in those with dementia compared with those without dementia undergoing pacemaker placement (9.7% vs. 2.5%, OR 4.26, 95% CI 3.67–4.94) and hip replacement surgery (12.3% vs. 4.8%, OR 2.75, 95% CI 2.56–2.95), respectively (Supplementary Table 5).

Discussion

While most clinicians attempt to incorporate patients’ priorities and treatment preferences, many clinicians do not have access to specific numerical estimates on the risk of adverse events to inform shared decisions. Our study addresses a key knowledge gap in the literature, providing the first analysis in nearly 30 years of the impact of dementia on readmission in U.S. patients undergoing PCI8. In this study, we provide an updated assessment of the association between dementia and post-PCI readmission rates and adverse outcomes, given advances in the uptake, accessibility, and safety of PCI in the intervening decades, as well as changes in practice patterns as directed by successive national guidelines on PCI24–26. We found that post-PCI readmission rates and adverse outcomes were significantly higher in patients with dementia. For clinical context, the presence of dementia increased the hazard of 30-day readmission comparably to that seen in another commonly performed cardiac procedure (pacemaker placement), but less so than what was observed with a commonly performed non-cardiac procedure (hip replacement). Patients with dementia experienced higher odds of delirium, in-hospital mortality, cardiac arrest, blood transfusion, acute kidney injury, and fall in hospital compared with patients without dementia. These trends were seen despite propensity score matching, suggesting that the presence of dementia itself may confer additional risk for mortality, readmissions, and adverse outcomes. Furthermore, we found that dementia was independently associated with higher rates of 30-day readmission for any cause compared with patients without dementia.

Hospital readmission and development of adverse outcomes are important factors determining post-PCI quality life in patients with dementia27. In this large population of U.S. patients who underwent PCI, dementia was an independent predictor of 30-day readmission even after adjustment for other clinical and in-hospital characteristics. Patients with dementia undergoing PCI experienced 11% increased odds of 30-day readmission compared with older adults without dementia, suggesting that the discussion of risks should extend beyond that of the index hospitalization. It should be noted that in the general population, the presence of dementia is associated with higher readmission rates compared to individuals without dementia, with effect sizes varying by study design and site.28–31 Although we performed propensity score matching and identified an association between the presence of dementia and higher rates of readmission, we cannot make conclusions as to whether dementia is the causal factor for the increased readmission rate. The inability to differentiate whether a readmission is related to an index hospitalization is a common theme in readmissions research and policymaking.32 We have attempted to contextualize these findings in the setting of two other common procedures. We found that the increase in the hazard for readmission and in-hospital mortality of patients with dementia after PCI is comparable to that of pacemaker placement, another commonly performed cardiac procedure in older adults. In contrast, the increase in the hazard of 30-day readmission after PCI was lower than that after a commonly performed non-cardiac procedure, hip replacement surgery, all within a cohort of patients with dementia. This is a useful finding that can facilitate communication with patients and their families at the point-of-care regarding the decision to proceed with PCI, including possibly as part of a future decision aid, as both pacemaker placement and hip replacement surgery are common procedures that patients and their families may be familiar with.

Patients with dementia represent a complex population for PCI-related decisions. On one hand, observational data suggests that PCI may confer a survival benefit in dementia patients with acute myocardial infarction6. However, this survival benefit does not appear to extend to patients with negative troponins or stable disease33–35, and in older adults with dementia, potential harms following PCI must be considered. Physicians, patients, and families may contemplate many factors in the decision to pursue or defer PCI, including potential complications, quality of life, compatibility with patient’s established goals of care, and limited life expectancy. In the pre-procedural setting when the discussion can sometimes be perceived as ‘withholding’ or offering PCI, knowledge of the threefold rate of post-procedural in-hospital delirium allows clinicians and families to develop a more holistic understanding of the downstream course of events. Delirium, with its associated alteration in personality, can be a jarring experience for families that is highly clinically significant. Quality improvement work could involve modification of sedation practice to minimize administration of delirium-inducing agents and incorporation of a delirium prevention order set into the post-PCI order pathway, with nursing efforts such as enforcing the perception of day and night by window blinds. Noting that dementia patients undergoing PCI have more than one and a half times the rate of falls in hospital, quality improvement work could involve modification of protocols by nursing, physical therapy, and occupational therapy to maximize fall prevention precautions in this population. Noting that dementia patients undergoing PCI have 15% increased odds of in-hospital mortality, quality improvement work could involve development of policies where these patients are booked for designated stepdown beds beside the unit nursing station for closer monitoring, or application of early warning systems that predict cardiac arrest. Noting that dementia patients undergoing PCI have a 30% increased odds of AKI, quality improvement work could involve modification of the post-procedural order set for AKI prophylaxis, which at many institutions is based on the intra-procedural left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP), to prompt the clinician to also take into account the patient’s dementia status and ability to voluntarily consume oral fluids versus the need to provide them intravenously. Each of these initiatives, which has the potential to impact the process and experience of caring for this patient population, warrants its own set of plan-do-study-act cycles.

Our sensitivity analyses evaluating the association between dementia and readmission risk across different age groups demonstrated that while dementia was associated with higher hazard of 30-day readmission in patients ≥65 years or ≥75 years, no association was seen in those ≥85 years. Although the interaction between these age groups and dementia was not significant (P-interaction=0.28), the findings suggest that the impact of dementia on readmission risk may diminish with older age. Dementia predisposes patients to pneumonia, feeding problems, injuries, ulcers, and aspiration, whose prevalence is intrinsically high in the oldest old population36. It may be that the presence of multiple morbidities and frailty in the oldest old population results in increased readmissions regardless of concomitant dementia. This finding supports the hypothesis that the higher rates of readmission seen in patients with dementia are not a result of PCI per se, but rather due to the risks associated with dementia itself.

In addition to dementia, we identified a number of other independent predictors of 30-day readmission. The finding that smoking, diabetes, heart failure, valvular heart disease, atrial fibrillation, peripheral artery disease, previous stroke, chronic pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, end-stage renal disease, and deficiency anemia are factors significantly associated with post-PCI readmission should prompt special attention to these comorbidities in the post-procedural period. Interestingly, length of hospital stay had a significant and negative association with risk of 30-day readmission. This might reflect the presence of premature discharges leading to 30-day readmission. It remains to be seen whether certain prevention strategies can reduce post-PCI readmission.

Of note, in contrast with other studies on delirium and readmission37, delirium at the index hospitalization was not associated with increased risk of 30-day readmission in our cohort. A possible explanation is that more patients with in-hospital delirium were discharged to skilled nursing facilities (41.7%) compared with patients without in-hospital delirium (27.8%), potentially attenuating the risk of 30-day readmission. It is possible that patient behaviors related to the delirium led to intentional disposition planning for discharge to skilled nursing, in order to provide closer support and monitoring, consequently reducing their likelihood of requiring readmission. In the same vein, more patients with dementia were discharged to skilled nursing (43.5%) compared with patients without dementia (28.7%). The result of the interaction analysis was consistent with this hypothesis. Another explanation is that delirium may have resolved after discharge, thus no longer contributing to increased readmissions.

Our results should be viewed in light of several limitations. Analyses based on administrative datasets, including the NRD, are susceptible to coding errors38, and do not capture the nuances of disease (e.g. severity of dementia, type of dementia), the method of diagnosis (e.g. as delirium or other forms of altered mental status may be labeled in the chart as dementia), procedural details (e.g. anatomy of coronary lesions, complexity of PCI, success of procedure, procedural complications), advance directive information (e.g. do not resuscitate status), or socioeconomic details (e.g. family support, home safety, financial status), which are factors that likely influence readmission risk. Dementia may be underreported in both primary and secondary DRG diagnoses even in patients whose condition precipitating admission is dementia39. In addition, while PCI for STEMI, NSTEMI, and UA are done as inpatient, PCI for SIHD can occur as an outpatient or inpatient. Because outpatient cardiac catheterizations are not captured in the NRD, true estimates for outcomes of PCI in SIHD may be different from what we found in the NRD. Moreover, patients with dementia experience delayed presentations of ACS, pre-hospital logistics, and door-to-balloon time due to impaired ability to communicate symptoms of ACS and preferences about quality of life40. Thus, the average patient with dementia may have had a more prolonged time of ischemia than the average patient without dementia prior to PCI, even though they are labeled with the same ICD code for ACS. Finally, measures of frailty, which predict post-surgical outcomes across subspecialties41, are also not captured in this analysis.

In conclusion, in comparison to patients without dementia, patients with dementia who undergo PCI have markedly increased rates of delirium and other in-hospital adverse events and a higher rate of 30-day readmission. The degree of increased risk of 30-day readmission conferred by the presence of dementia is similar between those undergoing PCI and another commonly performed cardiac procedure, pacemaker placement, but lower than that seen with hip replacement surgery. These findings are important to inform shared decision-making and expectations about hazards of hospitalization in patients with dementia undergoing PCI.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1. List of the ICD-10-CM and ICD-10-PCS codes used.

Supplementary Table 2. General characteristics of index hospitalizations for PCI stratified to dementia (full).

Supplementary Table 3. Comparison of outcomes between patients with and without dementia at index hospitalizations stratified to clinical presentation.

Supplementary Table 4. General characteristics of index hospitalizations for pacemaker placement stratified to dementia.

Supplementary Table 5. General characteristics of index hospitalizations for hip replacement surgery stratified to dementia.

Supplementary Table 6. Comparison of outcomes between patients with and without dementia at index hospitalizations for pacemaker placement and hip replacement surgery.

Supplementary Figure 1. Flow chart of this study.

Supplementary Figure 2. Overlap plot for propensity score matching.

Supplementary Figure 3. Love plot for propensity score matching.

Supplementary Figure 4. Disposition after discharge from index hospitalization.

Supplementary Figure 5. Sensitivity analysis including patients ≥65, ≥75, and ≥85 years-old.

Supplementary Figure 6. Kaplan-Meier curves of 30-day readmission in patients with and without dementia stratified to presentation.

Supplementary Figure 7. Cause of 30-day readmission in patients with and without dementia.

Supplementary Figure 8. Complete potential risk factors of 30-day readmission in patients with dementia.

Supplementary Figure 9. Overlap plot for propensity score matching in cohort of pacemaker placement.

Supplementary Figure 10. Love plot for propensity score matching in cohort of pacemaker placement.

Supplementary Figure 11. Kaplan-Meier curves of 30-day readmission after pacemaker placement in patients with and without dementia.

Supplementary Figure 12. Overlap plot for propensity score matching in cohort of hip replacement surgery.

Supplementary Figure 13. Love plot for propensity score matching in cohort of hip replacement surgery.

Supplementary Figure 14. Kaplan-Meier curves of 30-day readmission after hip replacement surgery in patients with and without dementia.

Central Illustration. Observed adverse in-hospital events and 30-day readmissions among patients with dementia undergoing PCI and other common procedures. This figure provides expectations clinicians, patients, and families for potential adverse events and 30-day readmissions among patients with dementia vs. without dementia undergoing PCI. The figure also provides context for the hazard of 30-day readmission by also presenting 30-day readmission rates for two commonly performed cardiac (pacemaker placement) and non-cardiac (hip replacement surgery) procedures performed in this population.

Key points.

Patients with dementia have higher hazard of 30-day readmission after PCI than those without dementia.

Those with dementia also have higher odds of delirium, in-hospital mortality, cardiac arrest, acute kidney injury, and fall after PCI.

These findings should help guide shared decision-making, especially in the context of similar or worse clinical outcomes seen with other commonly performed procedures, such as pacemaker placement and hip replacement surgery.

Why does this matter?

As clinicians increasingly encounter patients with dementia who may require percutaneous coronary intervention, understanding in-hospital adverse events and readmissions is crucial to inform shared decision-making with patients, families, and caregivers. Integration of known quantitative risks and benefits of PCI into the shared decision-making process in populations with dementia represents a key area for future implementation efforts.

Acknowledgements

Funding:

no grants, contracts, or other forms of financial support was received for this study

Sponsor’s role

No funding was received in conducting this study.

Abbreviations

- ACS

Acute coronary syndrome

- AMI

Acute myocardial infarction

- CI

Confidence interval

- HCUP

Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project

- ICD-10-CM

International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification

- ICD-10-PCS

International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Procedure Coding System

- HR

Hazard ratio

- NRD

National Readmissions Database

- NSTEMI

Non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction

- OR

Odds ratio

- PCI

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- SIHD

Stable ischemic heart disease

- STEMI

ST-elevation myocardial infarction

- UA

Unstable angina

Footnotes

Disclosures:

Park DY: None

Hu JR: None

Alexander KP: None

Nanna MG: Dr. Nanna reports funding from the American College of Cardiology Foundation supported by the George F. and Ann Harris Bellows Foundation and from the National Institute on Aging/National Institutes of Health from R03AG074067 (GEMSSTAR award).

Conflict of interest

Dr. Nanna reports funding from the American College of Cardiology Foundation supported by the George F. and Ann Harris Bellows Foundation and from the National Institute on Aging/National Institutes of Health from R03AG074067 (GEMSSTAR award). Graphical abstract was created with icons from BioRender.

Data statement

Data included in this study can be found in the public website of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP)

Ethical approval

This study was exempt from ethics approval as publicly available deidentified data from the Nationwide Readmissions Database were used.

References

- [1].Alkhouli M, Alqahtani F, Kalra A, et al. Trends in Characteristics and Outcomes of Patients Undergoing Coronary Revascularization in the United States, 2003–2016. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3: e1921326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].von Strauss E, Viitanen M, De Ronchi D, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L. Aging and the occurrence of dementia: findings from a population-based cohort with a large sample of nonagenarians. Arch Neurol 1999;56: 587–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Public Health Agency of Canada. Dementia and ischemic heart disease comorbidity among Canadians aged 65 years and older: Highlights from the Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System 2021.

- [4].Tehrani DM, Darki L, Erande A, Malik S. In-hospital mortality and coronary procedure use for individuals with dementia with acute myocardial infarction in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61: 1932–1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Vu M, Koponen M, Taipale H, Kettunen R, Hartikainen S, Tolppanen A-M. Coronary Revascularization and Postoperative Outcomes in People With and Without Alzheimer’s Disease. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A 2021;76: 1524–1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Cermakova P, Szummer K, Johnell K, et al. Management of Acute Myocardial Infarction in Patients With Dementia: Data From SveDem, the Swedish Dementia Registry. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2017;18: 19–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chanti-Ketterl M, Pathak EB, Andel R, Mortimer JA. Dementia: a barrier to receiving percutaneous coronary intervention for elderly patients with ST-elevated myocardial infarction. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2014;29: 906–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sloan FA, Trogdon JG, Curtis LH, Schulman KA. The effect of dementia on outcomes and process of care for Medicare beneficiaries admitted with acute myocardial infarction. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52: 173–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Alexander KP, Newby LK, Cannon CP, et al. Acute Coronary Care in the Elderly, Part I. Circulation 2007;115: 2549–2569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Alexander KP, Newby LK, Armstrong PW, et al. Acute coronary care in the elderly, part II: ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology: in collaboration with the Society of Geriatric Cardiology. Circulation 2007;115: 2570–2589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Prince MJ, Wimo A, Guerchet MM, Ali GC, Wu Y-T, Prina M. World Alzheimer Report 2015 - The Global Impact of Dementia London: Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Zisberg A, Shadmi E, Gur-Yaish N, Tonkikh O, Sinoff G. Hospital-associated functional decline: the role of hospitalization processes beyond individual risk factors. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63: 55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].McCabe JJ, Kennelly SP. Acute care of older patients in the emergency department: strategies to improve patient outcomes. Open Access Emerg Med 2015;7: 45–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Krumholz HM. Post-hospital syndrome--an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med 2013;368: 100–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lum HD, Studenski SA, Degenholtz HB, Hardy SE. Early hospital readmission is a predictor of one-year mortality in community-dwelling older Medicare beneficiaries. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27: 1467–1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Visade F, Babykina G, Puisieux F, et al. Risk Factors for Hospital Readmission and Death After Discharge of Older Adults from Acute Geriatric Units: Taking the Rank of Admission into Account. Clin Interv Aging 2021;16: 1931–1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].An S, Ahn C, Moon S, Sim EJ, Park S-K. Individualized Biological Age as a Predictor of Disease: Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study (KoGES) Cohort. Journal of Personalized Medicine 2022;12: 505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Overview of the Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD) Volume 2022: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [Google Scholar]

- [19].AHA Data & Insights Volume 2022: American Hospital Association, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Doshi R, Patel N, Kalra R, et al. Incidence and in-hospital outcomes of single-vessel coronary chronic total occlusion treated with percutaneous coronary intervention. Int J Cardiol 2018;269: 61–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Goel K, Gupta T, Kolte D, et al. Outcomes and Temporal Trends of Inpatient Percutaneous Coronary Intervention at Centers With and Without On-site Cardiac Surgery in the United States. JAMA Cardiol 2017;2: 25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Healthcare C, Utilization P. DISCWT - Weight to discharges in the universe. NRD Description of Data Elements 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Austin PC. Using the Standardized Difference to Compare the Prevalence of a Binary Variable Between Two Groups in Observational Research. Communications in Statistics - Simulation and Computation 2009;38: 1228–1234. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Smith SC Jr., Dove JT, Jacobs AK, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for percutaneous coronary intervention (revision of the 1993 PTCA guidelines)-executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines (Committee to revise the 1993 guidelines for percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty) endorsed by the Society for Cardiac Angiography and Interventions. Circulation 2001;103: 3019–3041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Circulation 2011;124: 2574–2609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lawton JS, Tamis-Holland JE, Bangalore S, et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Coronary Artery Revascularization. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2022;79: e21–e129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Pickens S, Naik AD, Catic A, Kunik ME. Dementia and Hospital Readmission Rates: A Systematic Review. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders Extra 2017;7: 346–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Briggs R, Dyer A, Nabeel S, et al. Dementia in the acute hospital: the prevalence and clinical outcomes of acutely unwell patients with dementia. QJM 2017;110: 33–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Daiello LA, Gardner R, Epstein-Lubow G, Butterfield K, Gravenstein S. Association of dementia with early rehospitalization among Medicare beneficiaries [DOI] [PubMed]

- [30].Ahmedani BK, Solberg LI, Copeland LA, et al. Psychiatric Comorbidity and 30-Day Readmissions After Hospitalization for Heart Failure, AMI, and Pneumonia. Psychiatric Services 2015;66: 134–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Mitchell R, Draper B, Harvey L, Brodaty H, Close J. The survival and characteristics of older people with and without dementia who are hospitalised following intentional self-harm. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2017;32: 892–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Joynt KE, Jha AK. Thirty-Day Readmissions — Truth and Consequences. New England Journal of Medicine 2012;366: 1366–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Boden WE, O’Rourke RA, Teo KK, et al. Optimal Medical Therapy with or without PCI for Stable Coronary Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2007;356: 1503–1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Maron DJ, Hochman JS, Reynolds HR, et al. Initial Invasive or Conservative Strategy for Stable Coronary Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2020;382: 1395–1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Savonitto S, Cavallini C, Petronio AS, et al. Early aggressive versus initially conservative treatment in elderly patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2012;5: 906–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med 2009;361: 1529–1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Sara CL Association between Inpatient Delirium and Hospital Readmission in Patients ? 65 Years of Age: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of Hospital Medicine 2019;14: 201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Finlayson E, Birkmeyer JD. Research based on administrative data. Surgery 2009;145: 610–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Fillit H, Geldmacher DS, Welter RT, Maslow K, Fraser M. Optimizing Coding and Reimbursement to Improve Management of Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2002;50: 1871–1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Birkemeyer R, Rillig A, Treusch F, et al. Outcome and treatment quality of transfer primary percutaneous intervention in older patients with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics 2011;53: e259–e262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Robinson TN, Wu DS, Sauaia A, et al. Slower walking speed forecasts increased postoperative morbidity and 1-year mortality across surgical specialties. Ann Surg 2013;258: 582–588; discussion 588–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1. List of the ICD-10-CM and ICD-10-PCS codes used.

Supplementary Table 2. General characteristics of index hospitalizations for PCI stratified to dementia (full).

Supplementary Table 3. Comparison of outcomes between patients with and without dementia at index hospitalizations stratified to clinical presentation.

Supplementary Table 4. General characteristics of index hospitalizations for pacemaker placement stratified to dementia.

Supplementary Table 5. General characteristics of index hospitalizations for hip replacement surgery stratified to dementia.

Supplementary Table 6. Comparison of outcomes between patients with and without dementia at index hospitalizations for pacemaker placement and hip replacement surgery.

Supplementary Figure 1. Flow chart of this study.

Supplementary Figure 2. Overlap plot for propensity score matching.

Supplementary Figure 3. Love plot for propensity score matching.

Supplementary Figure 4. Disposition after discharge from index hospitalization.

Supplementary Figure 5. Sensitivity analysis including patients ≥65, ≥75, and ≥85 years-old.

Supplementary Figure 6. Kaplan-Meier curves of 30-day readmission in patients with and without dementia stratified to presentation.

Supplementary Figure 7. Cause of 30-day readmission in patients with and without dementia.

Supplementary Figure 8. Complete potential risk factors of 30-day readmission in patients with dementia.

Supplementary Figure 9. Overlap plot for propensity score matching in cohort of pacemaker placement.

Supplementary Figure 10. Love plot for propensity score matching in cohort of pacemaker placement.

Supplementary Figure 11. Kaplan-Meier curves of 30-day readmission after pacemaker placement in patients with and without dementia.

Supplementary Figure 12. Overlap plot for propensity score matching in cohort of hip replacement surgery.

Supplementary Figure 13. Love plot for propensity score matching in cohort of hip replacement surgery.

Supplementary Figure 14. Kaplan-Meier curves of 30-day readmission after hip replacement surgery in patients with and without dementia.

Central Illustration. Observed adverse in-hospital events and 30-day readmissions among patients with dementia undergoing PCI and other common procedures. This figure provides expectations clinicians, patients, and families for potential adverse events and 30-day readmissions among patients with dementia vs. without dementia undergoing PCI. The figure also provides context for the hazard of 30-day readmission by also presenting 30-day readmission rates for two commonly performed cardiac (pacemaker placement) and non-cardiac (hip replacement surgery) procedures performed in this population.