Abstract

A-to-I RNA editing diversifies human transcriptome to confer its functional effects on the downstream genes or regulations, potentially involving in neurodegenerative pathogenesis. Its variabilities are attributed to multiple regulators, including the key factor of genetic variants. To comprehensively investigate the potentials of neurodegenerative disease-susceptibility variants from the view of A-to-I RNA editing, we analyzed matched genetic and transcriptomic data of 1596 samples across nine brain tissues and whole blood from two large consortiums, Accelerating Medicines Partnership-Alzheimer’s Disease and Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative. The large-scale and genome-wide identification of 95 198 RNA editing quantitative trait loci revealed the preferred genetic effects on adjacent editing events. Furthermore, to explore the underlying mechanisms of the genetic controls of A-to-I RNA editing, several top RNA-binding proteins were pointed out, such as EIF4A3, U2AF2, NOP58, FBL, NOP56 and DHX9, since their regulations on multiple RNA-editing events were probably interfered by these genetic variants. Moreover, these variants may also contribute to the variability of other molecular phenotypes associated with RNA editing, including the functions of 3 proteins, expressions of 277 genes and splicing of 449 events. All the analyses results shown in NeuroEdQTL (https://relab.xidian.edu.cn/NeuroEdQTL/) constituted a unique resource for the understanding of neurodegenerative pathogenesis from genotypes to phenotypes related to A-to-I RNA editing.

Keywords: A-to-I RNA editing, RNA editing quantitative trait loci, neurodegenerative disease, RNA-binding protein, mediation analysis

Introduction

A-to-I RNA editing, a unique type of post-transcriptional modification, presents its diverse roles in brain development and immune regulation to contribute to the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disease [1–3]. For example, the abnormal R764G editing of the AMPA subunit, GRIA2, is known to affect the rate of channel desensitization and recovery from it to involve in neurodegeneration [4]. Moreover, there are other pathogenic RNA-editing biomarkers proposed in previous studies, based on their aberrant editing frequencies and their functional effects on genes related to diseases [5–8]. However, the current studies lack an explanation of the disease-susceptibility variants from the view of these A-to-I RNA-editing biomarkers, which limits the development of drugs for treating neurodegenerative disease, although one recent study analyzed 216 Alzheimer’s blood samples for the identification of genetic variants associated with differentially edited sites [9]. Due to the existence of the tissue-specific variants potentially regulating A-to-I RNA editing [10], it is necessary to provide a more comprehensive landscape for the genetic controls of RNA editing in neurodegenerative disease across different tissue types.

For this goal, we systematically studied 1596 samples across nine brain tissues and whole blood from two large consortiums, Accelerating Medicines Partnership-Alzheimer’s Disease (AMP-AD) [11] and Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI) [12, 13]. From the raw data of whole genomic sequencing (WGS) and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data, first, we identified the genetic basis of A-to-I RNA-editing events among each tissue type of the neurodegenerative diseases. For a functional annotation of these variants, we then studied the potential underlying mechanisms of these associations from the view of RNA-binding regulations, considering the possible effects of RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) on A-to-I RNA editing [14]. Moreover, we investigated the other molecular phenotypes that may be affected by these variants and also related to A-to-I RNA editing due to their possible interactions [5, 6, 15, 16], such as protein function, gene expression and alternative splicing, to further uncover the links and pathways between genetic variants and neurodegenerative disease. All the analysis results were archived in NeuroEdQTL (https://relab.xidian.edu.cn/NeuroEdQTL/), serving as a reference knowledgebase of the neurodegenerative pathogenesis translating genotypes to multiple phenotypes related to A-to-I RNA editing.

Materials and methods

Samples of neurodegenerative diseases

To study the genetic controls of RNA editing in neurodegenerative diseases, we collected 1050 samples of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and 546 samples of Parkinson’s disease (PD) with both of RNA-seq and WGS data from two large consortiums (Table 1), AMP-AD [11] and PPMI [12, 13]. The bio-specimens of these samples were obtained from whole blood, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), head of caudate nucleus (AC), posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), cerebellum (CER), temporal cortex (TCX), frontal pole (FP), inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), parahippocampal gyrus (PG) and superior temporal gyrus (STG).

Table 1.

The statistics of RNA-editing QTLs

| Disease | Region | Samples | SNPs | Editing | edQTLsa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cis | Trans | |||||

| AD | DLPFC | 199 | 5 863 270 | 6791 | 40 864/26 015/983 | – |

| AC | 160 | 5 889 229 | 5499 | 15 684/9936/437 | – | |

| PCC | 113 | 5 811 231 | 3975 | 5571/3370/154 | – | |

| CER | 78 | 5 952 311 | 35 743 | 44 481/26 760/1412 | 8/4/3 | |

| TCX | 79 | 5 969 029 | 11 384 | 10 345/7804/302 | – | |

| FP | 117 | 6 040 822 | 3197 | 3446/2388/127 | – | |

| IFG | 101 | 5 922 378 | 2367 | 1339/1071/50 | – | |

| PG | 97 | 6 079 696 | 2094 | 744/588/30 | – | |

| STG | 106 | 6 053 632 | 1162 | 641/520/32 | – | |

| PD | Blood | 546 | 5 767 671 | 3617 | 85 101/41 687/1308 | 5320/1742/75 |

AD: Alzheimer’s disease, PD: Parkinson’s diseases, edQTL: RNA-editing quantitative trait locus, DLPFC: dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, AC: head of caudate nucleus, PCC: posterior cingulate cortex, CER: cerebellum, TCX: temporal cortex, FP: frontal pole, IFG: inferior frontal gyrus, PG: parahippocampal gyrus, STG: superior temporal gyrus.

aThe three numbers separated by forward slash were the number of pairs of RNA-editing QTLs and editing events, the number of RNA-editing QTLs, and the number of editing events.

Processing of RNA-seq data

For all these 1596 neurodegenerative samples, we either collected A-to-I RNA-editing events from one previous study [5], or performed RNA-editing identification pipeline same as that study. The genome coordinates of these detected A-to-I RNA-editing events were converted from GRCh38/hg38 to GRCh37/hg19 by LiftOver [17], to maintain the assembly consistence of RNA-editing events with genotype data. Then we selected informative A-to-I RNA-editing events for quantitative trait locus (QTL) analysis, if their missing rates were smaller than 0.3 and standard deviations of editing frequencies were larger than 5% (Figure 1A). After that, there was an average of 7583 informative A-to-I RNA-editing events for each tissue group (Table 1). The editing frequencies of these events across all samples in each group were then transformed into a standard normal distribution based on rank [18], to minimize the effects of outliers on the regression scores.

Figure 1.

The identification and distribution analysis of RNA-editing QTLs. (A) The pipeline of RNA-editing QTL identification. (B–D) The distributions of RNA-editing QTLs in repeats, regions and chromosomes. (E) The distances of RNA-editing QTLs from the associated editing events. (F) The enriched pathways of the associated edited genes by Enrichr.

Moreover, to discover the probable interplay between genetic variants, gene expressions or splicing patterns, and A-to-I RNA-editing events, we also quantified normalized read counts (transcript per million, TPM) by RNA-Seq by Expectation Maximization (RSEM) [19] and detected alternative splicing events (percent spliced in, PSI) by SplAdder [20]. Their genome coordinates and informative candidates were also processed similarly as A-to-I RNA-editing events above (Figure 1A).

Processing of genotype data

The germline genotype data were directly downloaded from AMP-AD and PPMI. They were detected by standardized pipeline using BWA [21] for alignment and HaplotypeCaller mode of GATK [22] for variant calling. To increase the reliability of genotype data, as previous literature [23–25], bi-allelic variants were selected according to variant quality score recalibration (‘PASS’), genotype quality (GQ ≥ 20), depth values (DP ≥ 10), minor allele frequency (MAF ≥ 5%), missing rate (Missing < 10%) and Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (P ≥ 1 ×  ). Finally, for each group, there were about 5.9 M genetic variants (Table 1) to be studied in the following RNA-editing QTL analysis.

). Finally, for each group, there were about 5.9 M genetic variants (Table 1) to be studied in the following RNA-editing QTL analysis.

Identification of RNA-editing QTLs

Like the QTL analyses performed in previous studies [18, 24], we needed to consider several confounders to improve the identification sensitivity of RNA-editing QTLs (edQTLs). For the confounders in each group, we first extracted the top five principal components (PCs) from the genotype data by smartpca [26] to correct the ethnicity differences. Next, we obtained the first 15 probabilistic estimations of RNA-editing residuals (PEERs) by PEER package in R [27] to eliminate possible batch effects. These PCs and PEER factors were combined with other common confounders such as gender, age and disease stages, as the covariates for further edQTL identification by MatrixeQTL (FDR < 0.05) [28].

For all the identified edQTLs, we continued to comparing the corresponding RNA-editing frequencies among their three genotyping groups by ANOVA (P < 0.05) and also analyzing their spearman correlations with RNA-editing events (P < 0.05). These two analyses validated the reliability of edQTL identification and also provided the visualization of the associations between genetic variants and RNA-editing events.

Additionally, we also performed expression QTL (eQTL) and splicing QTL (sQTL) analysis, similarly as the pipeline of edQTLs identification. The associations between these edQTLs and eQTLs or sQTLs were further explored to reveal the potentially regulatory mechanisms of genetic variants on multiple molecular phenotypes.

Distribution analysis of RNA-editing QTLs

The functions of genetic variants relied on their locations in specific genes or motifs. Thus, the functional annotations of these RNA-editing QTLs started from the analysis of their distributions. First, we assigned edQTLs in different chromosomes, regions and repeats, to reveal their preferred regulatory distances from corresponding editing events. Second, we identified the edQTLs potentially enriched in RNA-binding proteins and their targets from chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (CLIPseq) analyses [29–33], since the previous studies reported their regulatory roles in A-to-I RNA editing [14, 34]. Last, we also analyzed RNA-editing QTLs and their associated editing events in coding regions using SIFT, Polyphen2 and PROVEAN (dbNSFP version 4.2a) [35], to uncover their effects on deleterious proteins. The edQTLs in particular genes or regions may disrupt their original functions on A-to-I RNA editing.

Correlation analysis of RNA-editing QTLs with disease

To uncover the potentials of RNA-editing QTLs in neurodegenerative pathogenesis, we performed correlation analyses between these edQTLs and disease severity, GWAS traits, or clinical phenotypes. The severity relationships identified the RNA-editing QTLs possibly contributing to disease progression tested by ANOVA and Spearman method (P < 0.05). As for the GWAS associations, we discovered the genetic variants that were reported to be disease susceptibility loci or located in linkage disequilibrium (LD) regions with known GWAS tags using LDlinkR package [36]. The parameters of this tool were set as follows: (i) γ2 (the square of the Pearson correlation coefficient of LD) threshold: 0.5, (ii) population panel: CEU (Utah residents with northern and western European ancestry) and (iii) distance limit: 500 kb. Last, the edQTLs linked with clinical phenotypes were annotated according to the archives in ClinVar [37]. The above correlation analyses may help pinpoint the pathogenic variants in neurodegenerative disease. Some of these biomarkers and their host genes have been recognized as potential drug targets according to PharmGKB [38] and DrugBank [39]. Others may deserve to be studied further for their relationships with drugs.

Mediation analysis of genetic variants, editing events and other phenotypes

To identify the shared genetic basis of A-to-I RNA editing and other phenotypes, such as gene expressions and splicing patterns, we performed mediation analysis between them using three models [40]. The first model presented the genetic variants and their LD buddies [41] showing independent effects on RNA editing and other phenotypes tested by the three analyses of QTLs. The second model pointed out the potential factors acting as a bridge between genetic variants and A-to-I RNA-editing events (PedQTL➔mediators < 0.05, Pmediation effect < 0.05). The last model uncovered the possible downstream effects of genetic variants through the mediation of A-to-I RNA editing (PeQTL/sQTL➔editing < 0.05, Pmediation effect < 0.05). These analyses, on one hand, revealed partial mechanisms underlying the associations between genetic variants and editing events, on the other hand, studied further downstream effects of genetic variants associated with A-to-I RNA editing in neurodegenerative disease.

Results

The preferred regulations of RNA-editing QTLs on adjacent editing events to involve in neurodegenerative pathogenesis

Through our pipeline (Figure 1A), we detected 95 198 edQTLs associated with A-to-I RNA editing in the 1596 samples across nine brain regions and whole blood of neurodegenerative patients (Table 1). Almost all these edQTLs (98.75%, 94 011/95 198) were also tested to have significant correlations with corresponding RNA-editing events by other two methods, ANOVA and Spearman correlation. It validated the reliability of the identified RNA-editing QTLs. Of them, 98.17% (93 456/95 198) showed cis-regulatory effects on the RNA-editing events, while only a small part conferred trans-regulatory effects (Table 1). Moreover, these RNA-editing QTLs favored to locate in repeats (Figure 1B), non-coding regions (Figure 1C) and chromosome 19 (Figure 1D) as RNA-editing events reported in previous literature [5, 42]. Combining these analyses and the close distance of RNA-editing QTLs from the associated editing events (Figure 1E), we may conclude that RNA-editing QTLs prefer to regulate adjacent editing events.

For these RNA-editing QTLs, we then performed enrichment analysis (P < 0.05 and Q < 0.2) of their associated edited genes by Enrichr [43]. The enriched pathways as shown in Figure 1F revealed the probably involved neurodegeneration-related biological processes of these RNA-editing QTLs. For example, deregulated calcium signaling can lead to neurodegeneration via complex and diverse mechanisms involved in selective neuronal impairments and death [44]. The proteins of the NOD-like receptors family are linked with the pathophysiology of neurodegenerative diseases [45]. Dopamine is an important and prototypical neurotransmitter to affect synaptic plasticity, neuronal activity and behavior related to neurodegeneration [46, 47]. Thus, these RNA-editing QTLs may also play important roles in these neurodegeneration-related pathways through their possible regulations on A-to-I RNA editing. Here, we selected an RNA-editing QTL in the well-known neurodegenerative gene of APOE as an example to show its potentially pathogenic roles (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

An RNA-editing QTL (rs769450) showed its roles in neurodegeneration. (A–C) The Manhattan plot and boxplots showed that this RNA-editing QTL was negatively associated with two RNA-editing events in the cerebellum region of AD patients. (D, E) These two RNA-editing events were abnormally edited in AD samples compared to controls. (F) These analyses and previous literature revealed the alleviation role of this RNA-editing QTL in neurodegeneration. AD: Alzheimer’s disease.

This RNA-editing QTL (rs769450) located in 19:45410444 position of APOE gene. It showed significantly negative associations with two RNA-editing events in TOMM40 tested by all the three methods (Figure 2A–C). Of these two editing events, one presented a tendency of higher frequencies (P = 0.11 in Figure 2D), and the other was significantly up-edited (P = 0.01 in Figure 2E) in AD compared to controls. Moreover, we also discovered the potential roles of their host gene in extracellular amyloid beta aggregation [48]. Thus, the down-regulation function of this RNA-editing QTL on these two editing events in TOMM40 may explain its alleviation role in neurodegeneration (Figure 2F). These analyses also backed up the LD relationships between APOE and TOMM40 [49], the GWAS associations of this RNA-editing QTL with AD traits [50], and its correlations with warfarin drug responses to prevent the formation of blood clots constituted by fibrin interacting with amyloid-β peptide [37, 38].

RNA-editing QTLs may alter RNA-binding regulations on A-to-I RNA editing

To explore the mechanisms of the associations between RNA-editing QTLs and editing events, we analyzed that from the view of RNA-binding regulations. Firstly, we identified 716 RNA-editing QTLs in RBP genes associated with editing events in RBP targets (Figure 3A, Table S1 available online at http://bib.oxfordjournals.org/). The regulations of these RBPs on editing events were tested by their correlations in different genotyping groups (P < 0.05 in AA or aa group, Num > 10). Among the 103 significant pairs (Figure 3B), 96.12% (99) pairs were associated in only one genotyping group (Figure 3C). It revealed that the RNA-editing QTLs may disturb RNA-binding regulations on A-to-I RNA editing. For example, an RNA-editing QTL (rs3760252) in the RNA-binding protein of DDX42 may interfere in its regulations on the editing event (chr17_61913227_-) in its targeted gene of SMARCD2 (Figure 3D). It was supported by the differential editing frequencies among the three genotyping groups (Figure 3E), negative associations between the expressions of DDX42 and the frequencies of the editing event in only AA genotyping group (Figure 3F), the involvements of DDX42 in mRNA splicing [51], and the location of this editing site between two possible alternatively spliced exons targeted by this RBP from StarBase. Due to the differential frequencies of this editing event in AD compared to controls (Figure 3G), we may suggest this RNA-editing QTL as a potential biomarker in neurodegenerative disease. This analysis supported its GWAS associations with hemoglobin level, a risk factor of dementia [52].

Figure 3.

The analysis of RNA-editing QTLs in RBP genes to show their effects on A-to-I RNA editing. (A) The number of RNA-editing QTLs in RBP genes associated with the editing events in their targets. The pubmed IDs shown in this panel are the studies reporting the regulations of RNA-binding proteins on A-to-I RNA editing. (B) The number of pairs between RNA-editing QTLs in RBP genes and the editing events in their targets whose frequencies were significantly associated with RBP expressions. Blue and orange bars represent the negative and positive associations respectively. (C) The fraction of the significant associations in different genotyping groups. (D) The RNA-editing QTL (rs3760252) may interfere in the regulation of DDX42 on the editing event (chr17_61913227_-). (E) It was positively associated with the editing event in the cerebellum region of AD patients. (F) The expressions of DDX42 and the frequencies of the editing event were only significantly associated in the AA genotyping group. (G) The associated editing event was highly edited in AD. RBP: RNA-binding protein.

Next, we overlaid RNA-editing QTLs and evaluated global enrichment of RNA-editing associated variants [31] in the dataset of RBP targets from CLIPseq analyses of StarBase and one ADAR-binding study [30], as shown in Figure 4A and B. Both analyses identified the most enriched IGF2BP2, followed by EIF4A3, U2AF2, ELAVL1, NOP58, DHX9 and ADAR. These enriched RBPs were found to significantly interact with the three ADAR enzymes across different diseases and regions (Table S2 available online at http://bib.oxfordjournals.org/). Some of them have been validated as ADAR-binding partners [34, 53, 54]. The regulations of these RBPs on editing events were evaluated by their correlations in AA and aa genotyping groups (Tables S3 and S4 available online at http://bib.oxfordjournals.org/, Figure 4C). The statistical results revealed that 93.18% (12 796/13 732) cases showed significant associations in only one genotyping group, indicating that the genetic variants may eliminate or create RBP regulations on these editing events.

Figure 4.

The analysis of RNA-editing QTLs in RBP targets to show their effects on A-to-I RNA editing. (A) The number of RNA-editing QTLs in RBP targets. The pubmed IDs shown in this panel are the studies reporting the regulations of RNA-binding proteins on A-to-I RNA editing. (B) The enrichment (expected versus observed) of the RNA-editing QTLs in RBP targets by GREGOR. The enriched ADAR-binding sites from two different studies showed similar results, revealing the reliability of the CLIPseq analyses. (C) The number of RNA-editing QTLs in RBP targets potentially regulating the editing events whose frequencies were significantly associated with the corresponding RBP expressions in the genotyping groups (AA or aa). (D–F) An RNA-editing QTL potentially disrupted NOP58 regulation on an RNA-editing event of FGD5-AS1 in the STG region of AD patients. (G) The statistically positive or negative effects of several RNA-binding proteins on editing events in different groups. For more detailed statistics results, please refer to Table S5 available online at http://bib.oxfordjournals.org/. (H) The number of RBPs showing potentially positive or negative effects on the editing events in the four groups. For blood samples of PD and AC samples of AD, most RBPs showed negative effects on the RNA-editing events. While in another two groups, most RBPs presented positive effects. (I, J) For the 22 RBPs showing opposite effects on 81 RNA-editing events between blood samples of PD patients and CER samples of AD patients, we compared the levels of these editing events in the two groups. All the editing events were significantly down-regulated in PD, partially, since these RBPs probably conferred negative effects in this group. GREGOR: genomic regulatory elements and GWAS overlap algorithm, CLIPseq: cross-linking immunoprecipitation associated to high-throughput sequencing, DLPFC: dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, AC: head of caudate nucleus, PCC: posterior cingulate cortex, CER: cerebellum, TCX: temporal cortex, FP: frontal pole, IFG: inferior frontal gyrus, PG: parahippocampal gyrus, STG: superior temporal gyrus, PD: Parkinson’s disease.

Specifically, rs36118024, an RNA-editing QTL in NR2C2, may alter the bindings and regulations of NOP58 on the editing event in FGD5-AS1 through their competitions to show its possible roles in neurodegeneration. The hypothesis was supported by the significant associations between this RNA-editing QTL and the editing event (Figure 4D), the possible disrupted regulations of NOP58 on the editing event by this genetic variant (Figure 4E), the locations of this RNA-editing QTL and the editing event around NOP58-binding regions detected by photoactivatable-ribonucleoside-enhanced CLIPseq (PAR-CLIPseq) analyses (Figure 4F), and the effect of FGD5-AS1 on the neurodegeneration-related PI3K/Akt signaling pathway [55, 56]. The above analyses revealed the possible involvements of genetic variants in RNA-binding regulations on A-to-I RNA editing in neurodegenerative disease.

Furthermore, whether these RNA-binding proteins tended to enhance or inhibit the levels of A-to-I RNA-editing events was also a question needed to be addressed. To answer this, we performed one sample t-test for the significant correlation coefficients (Num > 10 and P < 0.05) between RBP expressions and the frequencies of the editing events in RBP targets (Table S5 available online at http://bib.oxfordjournals.org/, Figure 4G). Some RBPs presented consistently regulatory roles on A-to-I RNA editing in different groups, such as ADAR showing positive effects as the well-known knowledge [57] and DHX9 displaying negative effects as an RNA-independent interaction partner of ADAR [53, 58]. Also, additional RBPs may regulate RNA editing in bidirectional ways across different groups. For example, reported as an editing regulator [14], TROVE2 was prone to enhance editing in the cerebellum regions of AD patients and inhibit editing in the blood samples of PD patients. These differences may be attributed to the sample region heterogeneity (Figure 4H–J).

Shared genetic architecture of RNA editing across brain regions and diseases

To test the shared genetic architecture of RNA editing across different groups, we analyzed π1 statistics [59] for the P value distributions of the associations in the second dataset that were significantly correlated in the first dataset (Figure 5A, Figure S1A available online at http://bib.oxfordjournals.org/). Higher π1 values indicated a stronger shared signal. The shared genetic architectures were partially attributed to the number of significant pairs of RNA-editing QTLs and editing events in the second dataset (Figure 5B, Figure S1B available online at http://bib.oxfordjournals.org/), which was associated with the number of samples (Figure 5C) similar to that of expression QTLs analysis result (P = 1.89e-03, R = 0.85). During the analysis, cerebellum was an interesting outlier with smaller sample number, larger significant pairs of RNA-editing QTLs and editing events, and relatively less replications from other groups. It revealed a unique genetic basis of RNA editing in cerebellum, whose functional changes in cortical and subcortical connectivity were largely disease-specific and corresponded to neurodegenerative conditions [60]. Moreover, for the overlapped significant pairs, we also performed Pearson correlation analysis of beta values between two groups. Even the pairs between AD and PD were less associated than that in different brain regions of AD patients, the correlation coefficients were greater than 0.88 (Figure 5D). This extremely high correlation revealed the consistent effects of genetic variants on RNA-editing events across different groups. Specifically, the overlapped associations of RNA-editing QTLs with editing events between AD and PD may reveal the common regulatory pathways in different neurodegenerative diseases. For example, the potential regulation of rs36118024 on the editing event in FGD5-AS1 mentioned above was also observed in the blood samples of PD patients (Figure 5E and F).

Figure 5.

The shared genetic architecture of RNA editing across different regions and diseases. (A) π1 statistics for the significant pairs in the first dataset (row) that were also shared by the second dataset (column). The statistics values were calculated by two procedures. First, we selected the pairs of RNA-editing QTLs and editing events in the second dataset that were significantly correlated in the first dataset (FDR < 0.05). Second, for the P values of the selected associations, we calculated π1 values using the R function of qvalue_trunc with the bootstrap estimation method. (B) The π1 statistics results were partially attributed to the number of significant pairs in the second dataset. (C) The number of significant pairs was associated with the number of samples in each group. (D) Pearson correlation coefficients of beta values between two groups for the overlapped significant pairs of RNA-editing QTLs and editing events (P < 0.05). (E, F) AD and PD shared the genetic regulation of rs36118024 on the editing event in FGD5-AS1.

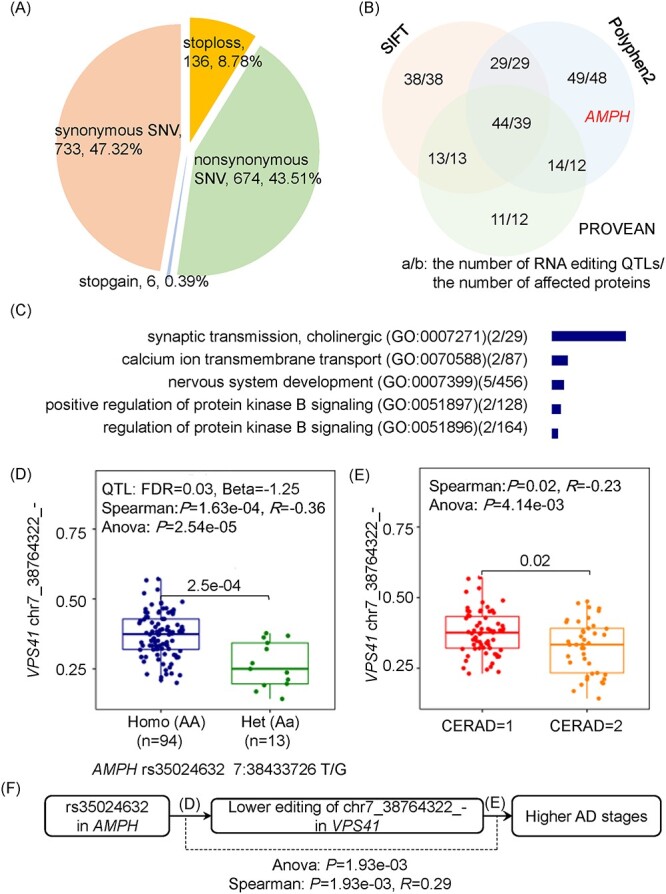

RNA-editing QTLs are potential genetic factors to modify protein functions

To uncover the effects of genetic variants on proteins, we identified 198 RNA-editing QTLs which themselves or whose associated editing events located in coding regions and were predicted to cause the deleterious functions of 172 proteins (Figure 6A and B), including 35 neurodegeneration related proteins. Due to the enriched functions of these proteins in the biological processes related to synaptic, calcium ion, and protein kinase B (Figure 6C, P < 0.05 and Q < 0.2), we assumed that the RNA-editing QTLs may also involve in these neurodegeneration-related pathways [61–63]. Specifically, an RNA-editing QTL (rs35024632, K454T) seems to aggregate AD from the down-regulation of an RNA-editing event in the neuroprotection related gene of VPS41 (Figure 6D–F) [64]. Thus, this exonic RNA-editing QTL may also be a potential biomarker from its genetic effects on the neurodegeneration related editing event.

Figure 6.

The effects of RNA-editing QTLs on proteins. (A, B) RNA-editing QTLs which themselves or whose associated RNA-editing events may affect amino acid sequences and protein functions. (C) The enriched biological functions and pathways of the neurodegeneration related proteins affected by RNA-editing QTLs (P < 0.05, Q < 0.2). (D, E) The genetic variant (rs35024632) may play its roles in neurodegeneration through the down-regulation of an RNA-editing event in the PCC regions of AD patients.

RNA-editing QTLs are also probable up-regulators of gene expressions

To further annotate the functions of these RNA-editing QTLs, we performed mediation analysis between genetic variants, RNA-editing events, and gene expressions using the models shown in Figure 7A. In total, there were 40 880 RNA-editing QTLs associated with both of editing events and gene expressions (Figure 7B). Of these associations, 90.05% (138 589/153 899) showed independent genetic effects on editing events and gene expressions (model ①), 4.60% (7071/153 899) provided propagation paths from genetic variants to A-to-I RNA-editing events via gene expressions (model ②), and 4.52% (6959/153 899) explained the further effects of RNA-editing QTLs on gene expressions through A-to-I RNA editing (model ③). In addition, 0.83% (1280/153 899) associations were not precisely classified into the second or third model of the propagations. The distributions of these associations were similar to the mediation analysis results of genetic variants, gene expressions and epigenetic landscape of human brains [65].

Figure 7.

Shared genetic architecture of RNA-editing events and gene expressions. (A) The models showed the associations between genetic variations, RNA-editing events, and gene expressions. (B) The distributions of these associations in each group. (C, D) One example in the CER region of AD patients showed that the edQTL (rs2240783) associated with the expression QTL in the adjacent locations of FUS targets may affect the expressions of SLC6A7, accompanied by the altered RNA-editing event (chr5_149575166_+) in it. (E, F) One example in the AC region of AD patients showed that the eQTL (rs7184655) may affect the expressions of neurodegeneration-related RPL13, through its regulation on an RNA-editing event (chr16_89630026_+) in the 3′-UTR of this gene.

For the potential mechanisms of the second model, we explored it in the view of the RNA-binding regulations. In total, there were 2506 RNA-editing QTLs associated with genetic variants in RNA-binding proteins or adjacent targets (±500 nt). One of them (rs2240783) may be associated with the expression regulatory functions of its LD buddy (rs2240784, expression QTL, γ2 = 0.5595) to confer its effects on the editing event. It was supported by the adjacent locations of genetic variants around FUS-binding targets from StarBase, positive correlations of the expressions between FUS and SLC6A7, differential expressions of SLC6A7 among the genotyping groups of the expression QTL, significant associations between SLC6A7 expressions and the editing levels, and distinct editing frequencies across the genotyping groups of the RNA-editing QTL (Figure 7C and D). Since SLC6A7 belongs to SLC superfamily that plays important roles in the recovery of neurotransmitters [66], the RNA-editing QTL associated with the phenotype changes of this gene may be a biomarker of neurodegeneration. This example not only described the probable effects of genetic variants on gene expressions through interfering in the RNA-binding regulations, but also revealed one possible mechanism underlying the associations between RNA-editing QTLs and A-to-I RNA-editing events.

To explain the natural properties of the third model, we analyzed the associations from the view of 3′-UTR regulations. In total, there were 629 RNA-editing QTLs associated with the editing events in 3′-UTRs, which may interfere in the miRNA regulations on gene expressions. For example, the expression QTL analysis identified the associations between rs7184655 and RPL13 (Figure 7E and F). This relationship may be partially attributed to the mediation of an RNA-editing event in the 3′-UTR of RPL13. In detail, this genetic variant, also as an RNA-editing QTL, probably up-regulated the 3′-UTR editing event. According to a previous ADeditome study, this editing event has been reported to create several new miRNA-binding targets, thus enhancing the degradations of RPL13. Due to the important roles of RPL13 in tau interactions [67, 68] and the GWAS associations between this variant and neurodegeneration-related creatinine levels [69], we may annotate the functions of this RNA-editing QTL in neurodegenerative pathogenesis. This example showed the potential mechanisms of the genetic effects on gene expressions through the mediations of A-to-I RNA editing, and also pointed out multiple phenotype changes probably caused by RNA-editing QTLs in neurodegenerative disease.

RNA-editing QTLs may involve in the regulations of alternative splicing

Similarly, for the effects of RNA-editing QTLs on splicing, we also performed mediation analysis between genetic variants, RNA-editing events and alternative splicing patterns. After that, we discovered 17 426 RNA-editing QTLs associated with both of editing and alternative splicing events (Figure 8A and B). Beside the 80.34% (76 933/95 762) independent associations (model ①) and 1.49% (1431/95 762) unclassified relationships, 6.34% (6073/95 762) may describe the genetic effects on spicing patterns as the potential up-regulators of A-to-I RNA-editing events (model ②), and 11.83% (11 325/95 762) presented the probable associations between genetic variants and splicing events through the partial mediation of A-to-I RNA editing (model ③).

Figure 8.

Shared genetic architecture of RNA editing and alternative splicing. (A) The models showed the associations between genetic variants, RNA-editing events and alternative splicing patterns. (B) The distributions of these associations in each group. (C, D) One example in the DLPFC region of AD patients showed that the edQTL (rs1049115) may disturb LIN28 regulations on the exon skipping and editing event in adjacent two genes. (E, F) One example in the CER region of AD patients showed that the eQTL (rs202639) was associated with an intron retention event though partial mediation of an RNA-editing event in ZC3H7B. For the potential mechanisms of the associations between editing and splicing, we explored the possible regulations of three RNA-binding proteins on these two events, supported by their significant correlations.

For the genetic effects on alternative splicing in the second model, we explored the possible mechanisms from the RNA-editing QTLs whose associated genetic variants located in RNA-binding proteins [29, 32, 33] or splicing regions (spliced exons ± 20 nt) to possibly involve in splicing regulations. After that, we identified 123 RNA-editing QTLs potentially responsible for alternative splicing events. For example, an RNA-editing QTL (rs1049115), also a splicing QTL, located in the skipped exon of NQO2 to potentially affect the regulation of LIN28 on the splicing event (Figure 8C and D). It was supported by the differential splicing among the three genotyping groups, the enhanced CLIP (eCLIP) analysis for the binding of LIN28 on the mutated region, and the regulatory roles of LIN28 on mRNA splicing [70]. Moreover, the altered splicing event seemed to significantly interact with the editing event in an adjacent downstream lncRNA of NQO2. This lncRNA was also predicted as a potential target of LIN28 by RBPmap [71], and its editing event had differential frequencies among the three genotyping groups. The analyses above revealed that this genetic variant may disrupt LIN28 regulations on the splicing and editing events of the two adjacent genes. One gene of them (NQO2) has showed its ability in neurodegenerative pathogenesis [72] and targeted by potential treatment drugs (NADH, menadione and melatonin) of neurological disorders [73–75]. Thus, the RNA-editing QTL causing the phenotype changes of this gene may be pointed out as a potential biomarker of neurodegeneration.

For the possible mechanisms of the third model, we identified 341 RNA-editing QTLs whose associated editing events located in RNA-binding proteins or splicing regions to probably interfere in the splicing of exons. Specifically, a genetic variant probably affected the intron retention of CSDC2 through partial mediation of an RNA-editing event in ZC3H7B (Figure 8E and F). The associations between this editing and splicing event may be attributed to the co-regulations of RNA-binding proteins, such as DHX9, PRPF8 and U2AF2. Their involvements in the regulations of alternative splicing and RNA editing have been showed in previous studies [34, 53, 76, 77]. According to these analyses, we expanded the functions of RNA-editing QTLs from diverse aspects of phenotype changes.

Discussion

This study aims to annotate genetic variants in neurodegenerative disease from the aspect of A-to-I RNA editing. Based on two large datasets of neurodegenerative samples, we identified 95 198 genetic variants associated with A-to-I RNA editing in total. Most of these associations belong to a kind of cis-regulatory controls, revealing the preferred regulations of genetic variants on adjacent A-to-I RNA-editing events (Figures 1 and 2). To further explore the functions of these genetic variants, we performed analyses from the following two parts. One section was to uncover the potential mechanisms for the associations between genetic variants and RNA-editing events from the altered regulations of RNA-binding proteins (Figures 3,4,7C and D,8). Another section was to identify other molecular phenotypes beside RNA editing that these genetic variants may affect in neurodegenerative disease. The analyses recognized genetic effects on protein recoding (Figure 6), gene expression (Figure 7E and F), and alternative splicing (Figure 8E and F) through A-to-I RNA editing. Moreover, among all these genetic variants, we discovered 131 RNA-editing QTLs associated with 650 drug phenotypes from PharmGKB [78], and 6120 RNA-editing QTLs in genes targeted by 569 approved drugs from DrugBank [39]. All these analyses results provided a reference knowledgebase for a better understanding of the neurodegenerative pathogenesis and drug responses from translating genotypes to multiple phenotypes related to A-to-I RNA editing.

The latter functional annotations of the genetic variants relied on the accurate identification of RNA-editing QTLs. To address this, our study also performed another two analyses, ANOVA and Spearman correlation. It showed that 99.09% (211 593/213 544) associations also passed these two tests, revealing the reliability of our QTL identification pipeline. Moreover, we also compared our pipeline with another procedure used in one previous study [65]. The comparison estimated π1 statistics as 0.94 (0.89 using the second calculation method shown in Figure S1 available online at http://bib.oxfordjournals.org/) for the significant associations between genetic variants and gene expressions among dorsolateral prefrontal cortex dataset in our study (FDR < 0.05) which were also shared using their method. It revealed the rigorousness and reliability of our pipeline. The accurate identification of phenotypes quantitative trait loci laid the foundation of further study for the functional annotations of genetic variants.

In this study, we also compared RNA-editing QTLs across tissues and diseases (Figure 5A, Figure S1A available online at http://bib.oxfordjournals.org/). The differences between nine brain regions of AD patients revealed the contributions of tissues to RNA-editing regulation diversity. This was also validated in another healthy human tissues from Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project [10]. As shown in Figure S2A available online at http://bib.oxfordjournals.org/, two similar brain regions, cerebellar hemisphere and cerebellum, owned more significant association pairs of genetic variants and RNA-editing events. Specifically, for cerebellum samples, this hypothesis of tissue contributions also held up with more than 3-folds of overlapped pairs between diseases and healthy controls in the same tissue when compared to that in different tissues (Figure S2B available online at http://bib.oxfordjournals.org/). Besides, the disease was also a potential factor to affect the genetic controls of RNA editing. For example, the healthy cerebellum and blood samples shared 3255 pairs of genetic variants and RNA-editing events. This number was reduced for the shared pairs between the cerebellum regions of AD patients and blood samples of healthy controls or PD patients. Interesting, compared to healthy controls, blood samples of PD patients had more overlapped pairs with the cerebellum regions of AD patients (Figure S2C available online at http://bib.oxfordjournals.org/). It revealed the similar pathogenesis between AD and PD.

Due to the tissue contributions to RNA-editing regulations, our work was complementary to one recent study. It identified RNA-editing QTLs in peripheral blood samples of 216 African American or White race Alzheimer’s patients [9], including 540 RNA-editing QTLs associated with differential editing events or GWAS risk variants. While our study recognized RNA-editing QTLs in nine brain regions of AD patients and whole blood samples of PD patients, covering 22 346 RNA-editing QTLs associated with 891 differential editing events, and 62 178 RNA-editing QTLs associated with GWAS risk alleles (Figure S3A–D available online at http://bib.oxfordjournals.org/). Both studies identified the roles of an RNA-editing QTL (rs2854160) in neurodegeneration (Figure S3E available online at http://bib.oxfordjournals.org/) from its associations with differentially edited sites between AD and controls (Figure S3F and G available online at http://bib.oxfordjournals.org/) [9]. These two studies constituted a landscape for the genetic architecture of A-to-I RNA editing in neurodegenerative disease. Further, this map will be continuously updated with more identified RNA-editing QTLs from other neurodegenerative samples across different tissues.

Moreover, due to the contributions of disease to RNA-editing regulations, we also performed RNA-editing QTL analysis with the same pipeline in healthy controls from the two consortiums (Table S6 available online at http://bib.oxfordjournals.org/). Based on the analyses, we validated the regulation preference of genetic variants on adjacent A-to-I RNA-editing events. Also, comparing the analysis results with that in neurodegenerative diseases, we discovered less association pairs of RNA-editing QTLs and editing events. It, on one hand, was attributed to the smaller sample numbers, suggesting the collection of more healthy control samples from other platforms in the future. On the other hand, it seems that neurodegenerative diseases may gain a part of RNA-editing regulations, due to the π1 statistics results shown in Figure S4 available online at http://bib.oxfordjournals.org/ ( ). Further analyses on these differences may reveal some mechanisms of neurodegeneration.

). Further analyses on these differences may reveal some mechanisms of neurodegeneration.

After that, to uncover the potential mechanisms for the associations between genetic variants and RNA-editing events, we mainly explored it from the view of interfered RNA-binding effects (Figures 3 and 4), due to the possibility of allele-specific binding and editing regulations by RNA-binding proteins proposed in previous studies [14, 79]. Beside the main editing enzymes of ADAR, we also discovered multiple other factors probably involved in the regulations of A-to-I RNA editing, including the top RNA-binding proteins such as EIF4A3, U2AF2, NOP58, FBL, NOP56 and DHX9. They were all significantly associated with ADAR expressions (Table S2 available online at http://bib.oxfordjournals.org/) and correlated with the editing events in their binding targets (Table S3 available online at http://bib.oxfordjournals.org/). For some of these RBPs, previous evidence has verified the bidirectional roles of DHX9 on RNA editing in cancers [58] and the alteration of most known editing sites in a single direction by U2AF2 in K562 cells [34]. The other RBPs can be further studied as novel RNA-editing regulators either through their interactions with the main editing enzymes indirectly or binding to the adjacent editing regions directly.

Last, to reveal the diverse functions of RNA-editing QTLs, we also identified the other molecular phenotypes possibly affected by these genetic variants and related to A-to-I RNA editing using mediation analysis (Figures 7 and 8). In total, 277 genes and 449 splicing events were involved in this kind of propagation paths (model ② and ③). These analyses mainly focused on the associations between single variant and each phenotype. According to the mediation results shown in NeuroEdQTL database, multiple genetic variants may confer their co-regulations on the downstream phenotypes, such as the potential regulations of five RNA-editing QTLs (rs7184655, rs35878298, rs77497623, rs2280370 and rs174035) on the expressions of RPL13 through A-to-I RNA editing (Figure 7E and F). Given this possibility and the interactions between multiple editing events or genes [5], we plan to propose a multi-layer network of DNA mutation, RNA editing, and gene expression in the future, to systematically explain the potential mechanisms related to these three kinds of features in neurodegenerative pathogenesis.

Conclusion

This study systematically annotated the potentials of genetic variants from the aspect of A-to-I RNA editing across nine brain tissues and whole blood of neurodegenerative disease. Specifically, it provided a reliable list of genetic variants associated with A-to-I RNA editing in two large neurodegeneration-related consortiums. Next, it tried to explain the potential mechanisms for the variant effects on editing events, revealing the top RNA-binding proteins probably regulating A-to-I RNA editing. Last, it proposed three other molecular phenotypes which were affected by these genetic variants and also related to A-to-I RNA editing. The whole work, combined with one recent RNA-editing QTL study in AD, will be a relatively comprehensive and unique resource for the genetic controls of A-to-I RNA editing in neurodegenerative disease.

Key Points

Analysis of matched genetic and transcriptomic data of 1596 samples across nine brain regions and whole blood of neurodegenerative patients identified 95 198 RNA-editing quantitative trait loci.

Genomic distribution analysis of 95 198 RNA-editing quantitative trait loci revealed the preferred genetic effects on adjacent editing events.

Studying the shared genetic architecture of RNA editing revealed the common regulatory pathways in different neurodegenerative diseases.

Exploration of the underlying mechanisms of the genetic controls of A-to-I RNA editing pointed out several top RNA-binding proteins whose regulations on multiple editing events were probably interfered by genetic variants, such as EIF4A3, U2AF2, NOP58, FBL, NOP56 and DHX9.

Mediation analyses of genetic variants, RNA-editing events and other molecular phenotypes identified the functions of three proteins, expressions of 277 genes and splicing of 449 events, which may be affected by genetic variants and also associated with A-to-I RNA editing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the Center for Computational Systems Medicine (CCSM) for valuable discussion.

Sijia Wu is an assistant professor of Xidian University. Her research interests are bioinformatics, computational biology and computational genomics.

Qiuping Xue is a master degree candidate in Xidian University. Her research interest is bioinformatics.

Mengyuan Yang is an assistant professor of Zhengzhou University. Her research interests are bioinformatics, computational biology and computational genomics.

Yanfei Wang is a Ph.D. candidate in the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. Her research interests are bioinformatics, computational biology and computational genomics.

Pora Kim is an assistant professor in the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. Her research interests are bioinformatics, computational biology and computational genomics.

Xiaobo Zhou is a professor in the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. His research interests are bioinformatics, systems biology, imaging informatics and clinical informatics.

Liyu Huang is a professor of Xidian University. His research interests are computational imaging and bioinformatics.

Contributor Information

Sijia Wu, School of Life Science and Technology, Xidian University, Xi’an 710071, China.

Qiuping Xue, School of Life Science and Technology, Xidian University, Xi’an 710071, China.

Mengyuan Yang, School of Life Sciences, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou 450001, China.

Yanfei Wang, Center for Computational Systems Medicine, School of Biomedical Informatics, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, Texas 77030, USA.

Pora Kim, Center for Computational Systems Medicine, School of Biomedical Informatics, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, Texas 77030, USA.

Xiaobo Zhou, Center for Computational Systems Medicine, School of Biomedical Informatics, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, Texas 77030, USA.

Liyu Huang, School of Life Science and Technology, Xidian University, Xi’an 710071, China.

Authors’ contributions

S.W., P.K. and X.Z. contributed to conception and study design. Q.X., M.Y. and Y.W. contributed to the acquisition of data. S.W. contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data. S.W. contributed to the drafting of the manuscript. S.W. and P.K. contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript. S.W. and L.H. contributed to the funding of this work. L.H. and X.Z. contributed to leadership and supervision of various aspects of this work. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Data availability

The clinical information, RNA sequencing and WGS data for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s patients were collected from AMP-AD (https://www.synapse.org/, Synapse ID: syn2580853) and PPMI (https://www.ppmi-info.org/). Analyses results involved in this study were available at NeuroEdQTL database (https://relab.xidian.edu.cn/NeuroEdQTL/).

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62002270), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, the Natural Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province of China (Grant No. 2020JQ-332), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2018M643583), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82227802), National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2017YFA0205202) and partially funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 61672422). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Behm M, Öhman M. RNA editing: a contributor to neuronal dynamics in the mammalian brain. Trends Genet 2016;32:165–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gardner OK, Wang L, Van Booven D, et al. RNA editing alterations in a multi-ethnic Alzheimer disease cohort converge on immune and endocytic molecular pathways. Hum Mol Genet 2019;28:3053–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Eisenberg E, Levanon EY. A-to-I RNA editing—immune protector and transcriptome diversifier. Nat Rev Genet 2018;19:473–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lomeli H, Mosbacher J, Melcher T, et al. Control of kinetic properties of AMPA receptor channels by nuclear RNA editing. Science 1994;266:1709–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wu S, Yang M, Kim P, et al. ADeditome provides the genomic landscape of A-to-I RNA editing in Alzheimer’s disease. Brief Bioinform 2021;22:bbaa384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Khermesh K, D'Erchia AM, Barak M, et al. Reduced levels of protein recoding by A-to-I RNA editing in Alzheimer's disease. RNA 2016;22:290–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ma Y, Dammer EB, Felsky D, et al. Atlas of RNA editing events affecting protein expression in aged and Alzheimer’s disease human brain tissue. Nat Commun 2021;12:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pozdyshev DV, Zharikova AA, Medvedeva MV, et al. Differential analysis of A-to-I mRNA edited sites in Parkinson’s disease. Genes 2021;13:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gardner OK, Van Booven D, Wang L, et al. Genetic architecture of RNA editing regulation in Alzheimer’s disease across diverse ancestral populations. Hum Mol Genet 2022;31:2876–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Park E, Jiang Y, Hao L, et al. Genetic variation and microRNA targeting of A-to-I RNA editing fine tune human tissue transcriptomes. Genome Biol 2021;22:1–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hodes RJ, Buckholtz N. Accelerating Medicines Partnership: Alzheimer’s Disease (AMP-AD) Knowledge Portal Aids Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Through Open Data Sharing. Taylor & Francis, Expert opinion on therapeutic targets 2016; 20:389–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Marek K, Jennings D, Lasch S, et al. The Parkinson progression marker initiative (PPMI). Prog Neurobiol 2011;95:629–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Marek K, Chowdhury S, Siderowf A, et al. The Parkinson's progression markers initiative (PPMI)–establishing a PD biomarker cohort. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2018;5:1460–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Quinones-Valdez G, Tran SS, Jun H-I, et al. Regulation of RNA editing by RNA-binding proteins in human cells. Commun Biol 2019;2:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Licht K, Kapoor U, Amman F, et al. A high resolution A-to-I editing map in the mouse identifies editing events controlled by pre-mRNA splicing. Genome Res 2019;29:1453–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kume H, Hino K, Galipon J, et al. A-to-I editing in the miRNA seed region regulates target mRNA selection and silencing efficiency. Nucleic Acids Res 2014;42:10050–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hinrichs AS, Karolchik D, Baertsch R, et al. The UCSC genome browser database: update 2006. Nucleic Acids Res 2006;34:D590–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Consortium G . The genotype-tissue expression (GTEx) pilot analysis: multitissue gene regulation in humans. Science 2015;348:648–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform 2011;12:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kahles A, Ong CS, Zhong Y, et al. SplAdder: identification, quantification and testing of alternative splicing events from RNA-Seq data. Bioinformatics 2016;32:1840–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM arXiv. 2013; arXiv:1303.3997.

- 22. Poplin R, Ruano-Rubio V, DePristo MA, et al. Scaling accurate genetic variant discovery to tens of thousands of samples BioRxiv. 2018;201178; 10.1101/201178. [DOI]

- 23. Cochran JN, Geier EG, Bonham LW, et al. Non-coding and loss-of-function coding variants in TET2 are associated with multiple neurodegenerative diseases. Am J Hum Genet 2020;106:632–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yang Y, Zhang Q, Miao Y-R, et al. SNP2APA: a database for evaluating effects of genetic variants on alternative polyadenylation in human cancers. Nucleic Acids Res 2020;48:D226–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Axelrud LK, Santoro ML, Pine DS, et al. Polygenic risk score for Alzheimer’s disease: implications for memory performance and hippocampal volumes in early life. Am J Psychiatry 2018;175:555–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Price AL, Patterson NJ, Plenge RM, et al. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet 2006;38:904–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stegle O, Parts L, Durbin R, et al. A Bayesian framework to account for complex non-genetic factors in gene expression levels greatly increases power in eQTL studies. PLoS Comput Biol 2010;6:e1000770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shabalin AA. Matrix eQTL: ultra fast eQTL analysis via large matrix operations. Bioinformatics 2012;28:1353–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li J-H, Liu S, Zhou H, et al. starBase v2. 0: decoding miRNA-ceRNA, miRNA-ncRNA and protein–RNA interaction networks from large-scale CLIP-Seq data. Nucleic Acids Res 2014;42:D92–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bahn JH, Ahn J, Lin X, et al. Genomic analysis of ADAR1 binding and its involvement in multiple RNA processing pathways. Nat Commun 2015;6:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schmidt EM, Zhang J, Zhou W, et al. GREGOR: evaluating global enrichment of trait-associated variants in epigenomic features using a systematic, data-driven approach. Bioinformatics 2015;31:2601–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Teng X, Chen X, Xue H, et al. NPInter v4. 0: an integrated database of ncRNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res 2020;48:D160–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lin Y, Liu T, Cui T, et al. RNAInter in 2020: RNA interactome repository with increased coverage and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res 2020;48:D189–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Freund EC, Sapiro AL, Li Q, et al. Unbiased identification of trans regulators of ADAR and A-to-I RNA editing. Cell Rep 2020;31:107656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liu X, Li C, Mou C, et al. dbNSFP v4: a comprehensive database of transcript-specific functional predictions and annotations for human nonsynonymous and splice-site SNVs. Genome Med 2020;12:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lin SH, Brown DW, Machiela MJ. LDtrait: an online tool for identifying published phenotype associations in linkage disequilibrium. Cancer Res 2020;80:3443–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Landrum MJ, Lee JM, Benson M, et al. ClinVar: public archive of interpretations of clinically relevant variants. Nucleic Acids Res 2016;44:D862–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Barbarino JM, Whirl-Carrillo M, Altman RB, et al. PharmGKB: a worldwide resource for pharmacogenomic information. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med 2018;10:e1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wishart DS, Feunang YD, Guo AC, et al. DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res 2018;46:D1074–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annu Rev Psychol 2007;58:593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet 2007;81:559–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chigaev M, Yu H, Samuels DC, et al. Genomic positional dissection of RNA editomes in tumor and normal samples. Front Genet 2019;10:211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kuleshov MV, Jones MR, Rouillard AD, et al. Enrichr: a comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res 2016;44:W90–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Marambaud P, Dreses-Werringloer U, Vingtdeux V. Calcium signaling in neurodegeneration. Mol Neurodegener 2009;4:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kong X, Yuan Z, Cheng J. The function of NOD-like receptors in central nervous system diseases. J Neurosci Res 2017;95:1565–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rangel-Barajas C, Coronel I, Florán B. Dopamine receptors and neurodegeneration. Aging Dis 2015;6:349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nobili A, Latagliata EC, Viscomi MT, et al. Dopamine neuronal loss contributes to memory and reward dysfunction in a model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Commun 2017;8:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ferencz B, Karlsson S, Kalpouzos G. Promising genetic biomarkers of preclinical Alzheimer's disease: the influence of APOE and TOMM40 on brain integrity. Int J Alzheimer’s Dis 2012;2012:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mise A, Yoshino Y, Yamazaki K, et al. TOMM40 and APOE gene expression and cognitive decline in Japanese Alzheimer’s disease subjects. J Alzheimers Dis 2017;60:1107–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Buniello A, MacArthur JAL, Cerezo M, et al. The NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog of published genome-wide association studies, targeted arrays and summary statistics 2019. J Nucleic Acids Res 2019;47(D1):D1005–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zhao B, Li Z, Qian R, et al. Cancer-associated mutations in SF3B1 disrupt the interaction between SF3B1 and DDX42. J Biochem 2022;172:117–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wolters FJ, Zonneveld HI, Licher S, et al. Hemoglobin and anemia in relation to dementia risk and accompanying changes on brain MRI. Neurology 2019;93:e917–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Aktaş T, Avşar Ilık İ, Maticzka D, et al. DHX9 suppresses RNA processing defects originating from the Alu invasion of the human genome. Nature 2017;544:115–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Stellos K, Gatsiou A, Stamatelopoulos K, et al. Adenosine-to-inosine RNA editing controls cathepsin S expression in atherosclerosis by enabling HuR-mediated post-transcriptional regulation. Nat Med 2016;22:1140–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Jiang F, Liu X, Wang X, et al. LncRNA FGD5-AS1 accelerates intracerebral hemorrhage injury in mice by adsorbing miR-6838-5p to target VEGFA. Brain Res 2022;1776:147751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Xu F, Na L, Li Y, et al. RETRACTED ARTICLE: roles of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signalling pathways in neurodegenerative diseases and tumours. Cell Biosci 2020;10:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 57. Nishikura K. A-to-I editing of coding and non-coding RNAs by ADARs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2016;17:83–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hong H, An O, Chan TH, et al. Bidirectional regulation of adenosine-to-inosine (A-to-I) RNA editing by DEAH box helicase 9 (DHX9) in cancer. Nucleic Acids Res 2018;46:7953–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Storey JD, Tibshirani R. Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2003;100:9440–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gellersen HM, Guo CC, O’Callaghan C, et al. Cerebellar atrophy in neurodegeneration—a meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2017;88:780–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Fang L, Duan J, Ran D, et al. Amyloid-β depresses excitatory cholinergic synaptic transmission in drosophila. Neurosci Bull 2012;28:585–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Cordaro M, Cuzzocrea S, Di Paola R. Ion channels and neurodegenerative disease aging related. In: Ion Transporters-From Basic Properties to Medical Treatment. London, England: IntechOpen, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Rosenberger AF, Hilhorst R, Coart E, et al. Protein kinase activity decreases with higher Braak stages of Alzheimer’s disease pathology. J Alzheimers Dis 2016;49:927–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Griffin EF, Yan X, Caldwell KA, et al. Distinct functional roles of Vps41-mediated neuroprotection in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease models of neurodegeneration. Hum Mol Genet 2018;27:4176–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ng B, White CC, Klein H-U, et al. An xQTL map integrates the genetic architecture of the human brain's transcriptome and epigenome. Nat Neurosci 2017;20:1418–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Aykaç A, Sehirli AO. The role of the SLC transporters protein in the neurodegenerative disorders. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci 2020;18:174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Wolozin B, Ivanov P. Stress granules and neurodegeneration. Nat Rev Neurosci 2019;20:649–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kong W, Mou X, Liu Q, et al. Independent component analysis of Alzheimer's DNA microarray gene expression data. Mol Neurodegener 2009;4:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Cui C, Sun J, Pawitan Y, et al. Creatinine and C-reactive protein in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, multiple sclerosis and Parkinson’s disease. Brain Commun 2020;2:fcaa152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Yang J, Bennett BD, Luo S, et al. LIN28A modulates splicing and gene expression programs in breast cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol 2015;35:3225–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Paz I, Kosti I, Ares M, Jr, et al. RBPmap: a web server for mapping binding sites of RNA-binding proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 2014;42:W361–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Voronin MV, Kadnikov IA, Zainullina LF, et al. Neuroprotective properties of Quinone reductase 2 inhibitor M-11, a 2-Mercaptobenzimidazole derivative. Int J Mol Sci 2021;22:13061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Lautrup S, Sinclair DA, Mattson MP, et al. NAD+ in brain aging and neurodegenerative disorders. Cell Metab 2019;30:630–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Zhang Y, Zhao Y, Wang Z, et al. Menadione sodium bisulfite inhibits the toxic aggregation of amyloid-β (1–42). Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA) Gen Subj 2018;1862:2226–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Roy J, Wong KY, Aquili L, et al. Role of melatonin in Alzheimer’s disease: from preclinical studies to novel melatonin-based therapies. Front Neuroendocrinol 2022;65:100986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Wickramasinghe VO, Gonzàlez-Porta M, Perera D, et al. Regulation of constitutive and alternative mRNA splicing across the human transcriptome by PRPF8 is determined by 5′ splice site strength. Genome Biol 2015;16:1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Glasser E, Maji D, Biancon G, et al. Pre-mRNA splicing factor U2AF2 recognizes distinct conformations of nucleotide variants at the center of the pre-mRNA splice site signal. Nucleic Acids Res 2022;50:5299–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Whirl-Carrillo M, McDonagh EM, Hebert J, et al. Pharmacogenomics knowledge for personalized medicine. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2012;92:414–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Yang E-W, Bahn JH, Hsiao EY-H, et al. Allele-specific binding of RNA-binding proteins reveals functional genetic variants in the RNA. Nat Commun 2019;10:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The clinical information, RNA sequencing and WGS data for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s patients were collected from AMP-AD (https://www.synapse.org/, Synapse ID: syn2580853) and PPMI (https://www.ppmi-info.org/). Analyses results involved in this study were available at NeuroEdQTL database (https://relab.xidian.edu.cn/NeuroEdQTL/).