Abstract

Background

For patients with bilateral, symptomatic unicompartmental knee arthritis, single-stage bilateral unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (ssBUKA) presents an attractive option. However, most studies have examined younger patient cohorts and the safety of ssBUKA remains controversial for older individuals. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to compare complication rates following ssBUKA for patients ≤70 and > 70 years old.

Methods

A retrospective chart review of 238 patients having undergone ssBUKA was performed, including 134 patients ≤70 and 104 patients >70. Post-operative complications were recorded at the six-week post-operative visit, along with emergency room visits and hospital readmissions within 90 days.

Results

Compared to patients ≤70, patients >70 were more frequently female (43.3% and 55.8%, respectively) (p = 0.037) and had significantly lower body mass index (30.41 ± 4.64 and 27.30 ± 3.68, respectively) (p < 0.001). Patients >70 were discharged home (50%) less commonly than patients ≤70 (73.1%) (p < 0.001). Two patients ≤70 (1.5%) and two patients >70 (1.9%) sought emergency room treatment (p = 0.589), with respiratory complications most common. There were no differences regarding any postoperative complications between patients ≤70 and > 70 years old.

Conclusion

These results suggest that patients >70 can safely undergo ssBUKA, as it does not appear to increase the incidence of early post-operative complications compared to patients ≤70. However, 50% of patients >70 were not able to discharge directly home following surgery.

Keywords: Single-stage bilateral, Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty, Complications, Safety, Elderly

1. Introduction

Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) is a viable option for patients with unicompartmental knee arthritis, with good clinical and functional outcomes reported while maintaining a low risk of perioperative complications.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 Unfortunately, at least 20% of patients undergoing a primary knee arthroplasty are affected by bilateral disease and seek treatment for the contralateral limb within a few years of their first surgery.7, 8, 9 Compared to two independent procedures, performing a single-stage bilateral UKA (ssBUKA) results in shorter cumulative operating time, shorter cumulative length of hospital stay, decreased overall rehabilitation time, and is more cost effective to both the patient and hospital.10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 Despite these benefits, patients undergoing ssBUKA may have an increased risk of major systemic complication17 such as proximal deep vein thrombosis or cardiac arrhythmia, compared to two independent procedures.

Previous research comparing complication rates of ssBUKA have generally evaluated relatively young patient cohorts, with average ages ranging from 59 to 66 for ssBUKA patients and 61 to 65 for unilateral patients.15, 16, 17 Specific evaluation of elderly patients, defined in the current study as over 70 years old, is limited to comparisons of unilateral UKA to the more invasive total knee arthroplasty.18,19 The UKA procedure in those studies was concluded to be the better option for elderly patients, with UKA patients over 70 having better clinical outcomes, faster return to function and lower perioperative mortality.18,19 While not previously evaluated, the combined benefits of UKA and single-stage bilateral procedures potentially provide a safe, effective treatment option for patients over 70 suffering from bilateral symptoms. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to (1) report early perioperative complications in patients ≤70 years old and patients >70 years old following ssBUKA and (2) evaluate the influence of age as an independent risk factor for perioperative complications.

2. Methods and materials

This was an institutional review board approved (IRB No. 20190840), retrospective study reviewing a single surgeon's complications arising from a consecutive cohort of patients who underwent single-staged bilateral UKA between May 2014 and October 2019. All surgeries were performed in a small (160 bed) community hospital. The surgeon reviewed performs approximately 300–350 primary and revision knee arthroplasties per year, of which 30–40% are UKA. Indications for UKA included radiographic evidence of anteromedial osteoarthritis, predominantly localized medial compartment knee pain, no history of anterior cruciate ligament injury or reconstruction, absence of knee instability throughout the range of motion and no flexion contractions greater than 15° of the lower extremity. All patients with symptomatic bilateral anteromedial knee pain and satisfying the above clinical criteria were considered candidates for single-staged bilateral surgery. Patients were not excluded from consideration of ssBUKA based on individual characteristics, living situation or presence of stable comorbidities. Patients were only excluded if they had any active or unstable medical conditions that would be considered a contraindication for any arthroplasty surgery such as any active regional or systemic infections, or any unstable cardiopulmonary, vascular, hematologic, or neurologic conditions. Patients undergoing treatment for malignancy were also excluded. All patients underwent medical clearance within thirty days of the scheduled procedure and were assigned an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification by experienced anesthesiologists involved in the Perioperative Surgical Home initiative.20

238 patients were identified for review during the data collection period specified. All patients received the same cemented mobile bearing implant (Oxford® Partial Knee; Zimmer Biomet, Warsaw, IN) (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). All patients were treated with the same preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative protocols. All patients underwent the same surgical protocol. The details of the surgical technique and perioperative protocols employed by the current study site have been described in detail in previous publications and are not included here.21,22

Fig. 1.

Pre-operative radiographs revealing left knee, anteromedial osteoarthritis – A) Anteroposterior View; B) Lateral View.

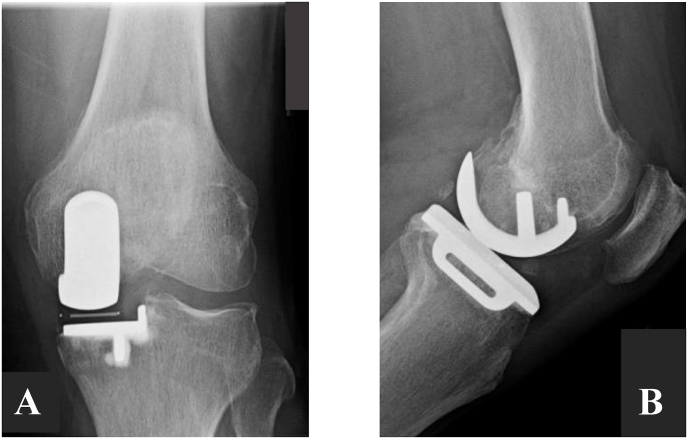

Fig. 2.

Post-operative radiographs following left unicompartmental arthroplasty – A) Anteroposterior View; B) Lateral View.

Patient characteristics at date of procedure were collected and included age, BMI, and ASA classification. Preoperative Knee Society Knee Score and Function Scores were collected prior to surgery. Perioperative data collected included any perioperative adverse events, hospital length of stay, and discharge destination. Early postoperative complications were defined as any wound or systemic complication arising within six weeks following surgery, with this extended to 90-days for emergency room visits or hospital readmissions.

Groups were divided into patients ≤70 and > 70 years old at the time of the procedure. Additional analyses were completed for each age group, stratified by discharge location and gender. Descriptive statistics for all outcome variables were determined for each group, including mean, standard deviations, and ranges. Univariate analyses were performed for all patients and by age group, with discharge location as the dependent variable. For significant variables or nearly significant variables (p < 0.10), multivariate analyses were performed to determine variables of influence. Odd ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were reported for significant variables. An analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed to control for gender when comparing pre-operative knee and function scores, by discharge location and age group. All statistical tests were performed using SPSS v25, with significance level of p < 0.05.

3. Results

There were 134 patients ≤70 years old and 104 patients >70 years old. Patients >70 had a significantly lower BMI (p < 0.001) and were more commonly female (p = 0.037) (Table 1). Patients >70 were less likely to be discharged directly home (50%) compared to patients ≤70 years old (73.1%) (p < 0.001). The univariate analysis examining factors potentially affecting ability to discharge directly home, indicated that females were twice as likely (p = 0.003) and patients >70 were nearly 3 times (p < 0.001) more likely to fail direct home discharge. In the multivariate analysis, only gender (OR: 2.083; p = 0.009) and age group (OR: 2.558; p = 0.001) significantly influenced patient discharge location (see Table 2).

Table 1.

Patient demographics by age group - mean (SD)/freq (%).

| Age ≤70 | Age >70 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Patients | 134 | 104 | |

| Age (years) | 63.94 (8.99) | 78.19 (6.13) | <0.001 |

| Body Mass Index | 30.41 (4.64) | 27.30 (3.68) | <0.001 |

| Gender (Male) | 76 (56.7%) | 46 (44.2%) | 0.037 |

| ASA (≤2) | 78 (58.2%) | 50 (48.1%) | 0.077 |

| IFG | 84 (62.7%) | 72 (69.7%) | 0.180 |

| Discharge (Home) | 98 (73.1%) | 52 (50.0%) | <0.001 |

| KSS Knee Score | 48.11 (10.75) | 49.09 (14.08) | 0.549 |

| KSS Function Score | 55.82 (12.88) | 54.71 (20.24) | 0.607 |

| Surgical Time (min) | 148.5 (22.8) | 145.3 (16.3) | 0.232 |

| Tourniquet Time (min) | 35.09 (7.74) | 33.56 (6.96) | 0.118 |

| LOS (days) | 1.13 (0.71) | 1.04 (0.44) | 0.229 |

SD = standard deviation; Freq = frequency; ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologist; IFG = impaired fasting glucose; KSS = Knee Society Score; min = minute; LOS = length of stay.

Table 2.

Univariate analysis for contributors to failing discharge directly home for all patients.

| OR | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | Reference | ||

| Female | 2.254 | 1.316–3.862 | 0.003 |

| Age Category | |||

| ≤70 | Reference | ||

| >70 | 2.722 | 1.583–4.680 | <0.001 |

| Body Mass Index | 0.998 | 0.941–1.058 | 0.946 |

| ASA | 0.952 | 0.562–1.615 | 0.856 |

| IFG | 0.875 | 0.504–1.519 | 0.635 |

| KSS Knee Score | 0.997 | 0.976–1.019 | 0.806 |

| KSS Function | 0.986 | 0.969–1.002 | 0.089 |

OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologist.

IFG = impaired fasting glucose.

KSS = Knee Society Score.

For patients ≤70, home discharge was achieved less frequently by females (p = 0.001) (Table 3), with no other significant differences to patients discharged to a short-term facility. Gender (OR: 3.765; 95% CI: 1.678–8.448; p = 0.001) was a significant individual contributor to discharge location, with BMI (OR: 1.075; 95% CI: 0.989–1.168; p = 0.088) being nearly significant. However, only gender significantly influenced patient discharge location in the multivariate analysis. Patients >70 discharged home had significantly higher pre-operative Knee Society Function Scores (p = 0.013) than those patients >70 requiring discharge to a short-term facility (Table 3). Function score was also significant in the multivariate analysis (OR: 0.975; 0.954–0.995; p = 0.013).

Table 3.

Patient characteristics for each age group by discharge location - mean (SD)/freq (%).

| Age ≤70 |

Age >70 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home (N = 98) | Other (N = 36) | p-value | Home (N = 52) | Other (N = 52) | p-value | |

| Age | 64.16 (5.54) | 63.33 (5.25) | 0.437 | 77.46 (5.93) | 78.92 (6.30) | 0.226 |

| Body Mass Index | 29.99 (4.68) | 31.55 (4.40) | 0.085 | 27.32 (3.75) | 27.28 (3.64) | 0.954 |

| Gender (Male) | 64 (65.3%) | 12 (33.3%) | 0.001 | 24 (46.2%) | 22 (42.3%) | 0.422 |

| ASA (≤2) | 56 (57.1%) | 22 (61.1%) | 0.417 | 24 (46.2%) | 26 (50.0%) | 0.422 |

| IFG | 62 (63.3%) | 22 (61.1%) | 0.486 | 38 (73.1%) | 34 (65.4%) | 0.262 |

| KSS-Knee | 48.18 (11.4) | 47.94 (8.93) | 0.912 | 49.68 (15.69) | 48.52 (12.48) | 0.679 |

| KSS-Function | 55.20 (12.56) | 57.50 (13.76) | 0.362 | 59.62 (21.28) | 49.81 (18.04) | 0.013 |

SD = standard deviation; Freq = frequency; N = number of patients; ASA = American Society.

Of Anesthesiologist; IFG = impaired fasting glucose; KSS = Knee Society Score.

Due to the influence of gender, an ANCOVA was used to control for gender when evaluating pre-operative knee and function scores. Both knee and function scores remained insignificant between discharge locations when controlling for gender (p = 0.646 and p = 0.510, respectively). Similarly, in patients >70, knee score remained insignificant (p = 0.767) and function score remained significantly different (p = 0.014) between discharge locations.

Five patients presented with a post-operative complication within six weeks. Respiratory complications were the most common, with two patients ≤70 (1.5%) and two patients >70 (1.9%) seeking treatment via the emergency room within the first six weeks (p = 0.589). One patient >70 (1.0%) underwent a manipulation under anesthesia due to poor range of motion at the six-week clinic visit (p = 0.437). No patient sustained a deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, cardiac or neurologic event, renal or urinary issues, bearing dislocation, periprosthetic infection or wound complication.

4. Discussion

Due to the exclusion of elderly patients in previous research, understanding the influence of age on the safety of ssBUKA has been limited and largely profiles complications in young patient cohorts.12,16,23 In a recent systematic review of the safety of simultaneous bilateral UKA, only ten articles reviewing 765 simultaneous BUKA met the criteria for inclusion.23 Only three of these studies included greater than 100 patients (191, 124, 159) in the cohorts undergoing simultaneous BUKA compared to the current study which involves 238 patients, 104 of which were >70 years old at the time of index surgery.23 The average age of patients in the studies reviewed undergoing simultaneous BUKA ranged from 58 to 70 years with most studies having an average age of ≤68 years old compared to the current study in which the average age of the older cohort was 78.23 The lack of large studies involving patients >70 years old undergoing ssBUKA cannot be overstated. With the stated benefits of both UKA and single-stage bilateral procedures, the purpose of the current study was, therefore, to evaluate the incidence of complications following ssBUKA for patients ≤70 and > 70 years old. In a direct comparison of two relatively large patient cohorts, with an average age of 63.9 and 78.2 years old, wound and systemic complications did not differ between the groups and no patient suffered a deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. The most common reason for emergency room visit was for upper respiratory symptoms, occurring in 1.5% and 1.9% of patients ≤70 and > 70 years old, respectively, with no patient requiring readmission. Based on these results, ssBUKA may be a valuable and safe procedure for elderly patients, when performed by an experienced arthroplasty surgeon.

As expected, patients >70 had a higher comorbidity index, with 52% of patients having an ASA of three or greater. Additionally, nearly 70% of patients were diagnosed with an impaired fasting glucose condition. While the increased presence of comorbidities may cause concern, the low incidence of post-operative complications is consistent with previous literature for ssBUKA on younger cohorts.15,16 Chan et al.17 reported a higher risk of major complications in the ssBUKA group, but also had an average tourniquet time of approximately 54 min per knee and a median length of hospital stay of five days. In comparison, the average tourniquet time in the current study was approximately 34 min, with an average length of stay of 1.1 days. Longer tourniquet times and length of stay have been identified as risk factors for post-arthroplasty complication, thus age may not represent the primary predictor for post-operative complications.

While age alone was not associated with an increased risk of perioperative complications, an additional area for concern with elderly patients undergoing ssBUKA was the comparatively low incidence of patients able to be discharged directly home following surgery. Despite having a similar length of hospital stay, 73.1% of patients ≤70 were discharged directly home compared to only 50.0% of patients >70, indicating greater postoperative care may be needed as compared to two independent procedures. When directly comparing patient characteristics between discharge locations, female patients ≤70 were significantly more likely to require acute postoperative inpatient rehabilitation care prior to returning home compared to males. Interestingly, gender was not influential in discharge disposition for patients >70; rather a lower pre-operative knee function in patients >70 significantly increased the risk of requiring acute postoperative inpatient rehabilitation services prior to returning home. Compared to previous research, pre-operative knee function for all patients >70 was similar to previously published scores for ssBUKA.10,12,17 However, patients >70 discharged home had a significantly higher knee function score compared to those unable to discharge directly home (59.6 and 49.8, respectively). Not surprisingly, our data indicates that elderly patients with lower functional capacity will more likely require acute postoperative inpatient stays prior to returning home. Under current insurance coding, ssBUKA is not distinguished from unilateral UKA and is still considered an outpatient procedure. The current study indicates that for older patients with low pre-operative function, it may be unreasonable to expect true outpatient discharge for nearly half of all patients >70 years old.

This study had several limitations. First, this represents a retrospective study involving patients treated in a high volume community hospital setting, to which multiple primary care physicians refer patients. An exhaustive evaluation of patient specific comorbidities could not be collected due to various primary care practice locations and systems. However, ASA classifications were assigned based on medical histories provided by the primary care physician prior to surgery. Therefore, the ASA classification was the most accurate indication of overall health status available. Additionally, only emergency room visits or readmissions could be evaluated. Minor postoperative medical issues such as urinary retention or constipation may have been treated by primary care physicians and may be unaccounted for. Second, only short term (six week) complications were evaluated. However, this ensured a 100% review of all patients involved and identification of any early significant complications, readmissions or emergency room visits within the study period. Third, the acute rehabilitation facility is not part of the study site hospital system, therefore, the length of stay at this facility could not be collected limiting the ability to comment on the financial consequences or accurately assess the post-operative inpatient requirements for ssBUKA in patients >70 years old. Finally, data were collected from procedures performed by a single, high-volume surgeon in an institution with at least ten years of high-volume fast track arthroplasty experience. While this may eliminate variability related to surgical technique, these results may not be generalizable to lower volume institutions.

5. Conclusion

The results of the current study support the safety of performing ssBUKA in patients >70 years of age. Despite 52% and 70% of patients >70 presenting with an ASA ≥3 and impaired fasting glucose, respectively, the incidence of systemic and wound complications was not significantly different from patients ≤70 years old. Older patients, however, were less likely to achieve home discharge following ssBUKA, particularly those with lower pre-operative functional scores. These patients will likely require greater inpatient resource utilization following ssBUKA than younger, higher functioning patients and surgeons should counsel and plan for this accordingly.

Conflict of interest

All other authors certifies that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g. consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or non-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval

This retrospective chart review study involving human participants was in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The Hawai'i Pacific Health Research Institute (local Western Institutional Review Board) approved this study.

Informed consent

This was a retrospective chart review and data collected were deidentified and presented as large scale, aggregate data. Therefore, no informed consent was obtained or required by the IRB.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Kadee-Kalia Tamashiro: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Landon Morikawa: Data curation. Samantha Andrews: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Cass K. Nakasone: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Acknowledgements

None.

References

- 1.Howieson A., Farrington W. Unicompartmental knee replacement in the elderly: a systematic review. Acta Orthop Belg. 2015;81(4):565–571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fabre-Aubrespy M., Ollivier M., Pesenti S., Parratte S., Argenson J.N. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty in patients older than 75 results in better clinical outcomes and similar survivorship compared to total knee arthroplasty. A matched controlled study. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(12):2668–2671. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2016.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris M.J., Molli R.G., Berend K.R., Lombardi A.V., Jr. Mortality and perioperative complications after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2013;20(3):218–220. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2012.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siman H., Kamath A.F., Carrillo N., Harmsen W.S., Pagnano M.W., Sierra R.J. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty vs total knee arthroplasty for medial compartment arthritis in patients older than 75 Years: comparable reoperation, revision, and complication rates. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32(6):1792–1797. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2017.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher D.A., Dalury D.F., Adams M.J., Shipps M.R., Davis K. Unicompartmental and total knee arthroplasty in the over 70 population. Orthopedics. 2010;33(9):668. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20100722-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vasso M., Antoniadis A., Helmy N. Update on unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: current indications and failure modes. EFORT Open Rev. 2018;3(8):442–448. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.3.170060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Romagnoli S., Zacchetti S., Perazzo P., Verde F., Banfi G., Vigano M. Onsets of complications and revisions are not increased after simultaneous bilateral unicompartmental knee arthroplasty in comparison with unilateral procedures. Int Orthop. 2015;39(5):871–877. doi: 10.1007/s00264-014-2545-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meehan J.P., Danielsen B., Tancredi D.J., Kim S., Jamali A.A., White R.H. A population-based comparison of the incidence of adverse outcomes after simultaneous-bilateral and staged-bilateral total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(23):2203–2213. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sayeed S.A., Sayeed Y.A., Barnes S.A., Pagnano M.W., Trousdale R.T. The risk of subsequent joint arthroplasty after primary unilateral total knee arthroplasty, a 10-year study. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(6):842–846. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahn J.H., Kang D.M., Choi K.J. Bilateral simultaneous unicompartmental knee arthroplasty versus unilateral total knee arthroplasty: a comparison of the amount of blood loss and transfusion, perioperative complications, hospital stay, and functional recovery. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2017;103(7):1041–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2017.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lombardi A.V., Jr., Berend K.R., Walter C.A., Aziz-Jacobo J., Cheney N.A. Is recovery faster for mobile-bearing unicompartmental than total knee arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(6):1450–1457. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0731-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng S., Yang Z., Sun J.N., et al. Comparison of the therapeutic effect between the simultaneous and staged unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) for bilateral knee medial compartment arthritis. BMC Muscoskel Disord. 2019;20(1):340. doi: 10.1186/s12891-019-2724-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma T., Tu Y.H., Xue H.M., Wen T., Cai M.W. Clinical outcomes and risks of single-stage bilateral unicompartmental knee arthroplasty via oxford phase III. Chin Med J. 2015;128(21):2861–2865. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.168042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akhtar K.S., Somashekar N., Willis-Owen C.A., Houlihan-Burne D.G. Clinical outcomes of bilateral single-stage unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2014;21(1):310–314. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2013.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen J.Y., Lo N.N., Jiang L., et al. Simultaneous versus staged bilateral unicompartmental knee replacement. Bone Joint Lett J. 2013;95-B(6):788–792. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.95B6.30440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berend K.R., Morris M.J., Skeels M.D., Lombardi A.V., Jr., Adams J.B. Perioperative complications of simultaneous versus staged unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(1):168–173. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1492-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan W.C., Musonda P., Cooper A.S., Glasgow M.M., Donell S.T., Walton N.P. One-stage versus two-stage bilateral unicompartmental knee replacement: a comparison of immediate post-operative complications. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(10):1305–1309. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B10.22612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iacono F., Raspugli G.F., Akkawi I., et al. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty in patients over 75 years: a definitive solution? Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2016;136(1):117–123. doi: 10.1007/s00402-015-2323-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kennedy J.A., Matharu G.S., Hamilton T.W., Mellon S.J., Murray D.W. Age and outcomes of medial meniscal-bearing unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(10):3153–3159. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kain Z.N., Vakharia S., Garson L., et al. The perioperative surgical home as a future perioperative practice model. Anesth Analg. 2014;118(5):1126–1130. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sakka B., Shiinoki A., Morikawa L., Mathews K., Andrews S., Nakasone C.K. Comparisons of early post-operative complications following unilateral or single-stage bilateral unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2020;27:1406–1410. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2020.07.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsumoto M., Saito S., Andrews S., Mathews K., Morikawa L., Nakasone C.K. Barriers to achieving same day discharge following unilateral unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2020;27:1365–1369. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2020.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malahias M.A., Manolopoulos P.P., Mancino F., et al. Safety and outcome of simultaneous bilateral unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. J Orthop. 2021 Feb 19;24:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2021.02.019. PMID: 33679029; PMCID: PMC7907672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]