Abstract

Purpose:

We investigated whether a clinically used carbonic anhydrase inhibitor (CAIs) can modulate intraocular pressure (IOP) through soluble adenylyl cyclase (sAC) signaling.

Methods:

IOP was measured 1 h after topical treatment with brinzolamide, a topically applied and clinically used CAIs, using direct cannulation of the anterior chamber in sAC knockout (KO) mice or C57BL/6J mice in the presence or absence of the sAC inhibitor (TDI-10229).

Results:

Mice treated with the sAC inhibitor TDI-10229 had elevated IOP. CAIs treatment significantly decreased increased intraocular pressure (IOP) in wild-type, sAC KO mice, as well as TDI-10229-treated mice.

Conclusions:

Inhibiting carbonic anhydrase reduces IOP independently from sAC in mice. Our studies suggest that the signaling cascade by which brinzolamide regulates IOP does not involve sAC.

Keywords: intraocular pressure, IOP, soluble adenylyl cyclase, cAMP, pharmacological inhibitors, carbonic anhydrase

Introduction

Glaucoma is a family of optic neuropathies that can lead to irreversible vision loss by causing damage to the optic nerve. Increased intraocular pressure (IOP) is a significant risk factor for glaucoma, and therapeutics which lower IOP are effective treatments for glaucoma. Carbonic anhydrases are a family of zinc-containing metalloenzymes that catalyze the equilibrium of CO2 + H2O ←→ HCO3− + H+, and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (CAIs) have long been known to lower IOP to treat glaucoma.1–4 CAIs are thought to lower IOP by reducing the availability of HCO3− for anion exchange, thereby decreasing water movement and aqueous humor production from ciliary body epithelial cells.5–7

The ciliary epithelium contains a pigmented ciliary epithelium (PE) cell region, which contacts the ciliary stroma, and a nonpigmented ciliary epithelium (NPE) cell region, which contacts the aqueous humor. NPE cells are the primary site of aqueous humor secretion. There are 15 known isoforms of carbonic anhydrases in humans,8 and several carbonic anhydrase isoenzymes, including CAI, CAII, CAIV, CAVI, CAIX, and CAXII, have been shown to be expressed in NPE.5,9–12 Different carbonic anhydrases have distinct localizations within the cell, including the cytoplasm, membrane, and mitochondria.

In addition to carbonic anhydrase regulation of the CO2/HCO3−/pH equilibrium, cyclic 3′, 5′ adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) is among the signaling pathways which can regulate IOP.13–16 The ubiquitous second messenger, cAMP, is produced from adenosine triphosphate (ATP) by adenylyl cyclases and broken down by phosphodiesterases. There are 2 families of adenylyl cyclases in mammals: G-protein-regulated transmembrane adenylyl cyclases (tmACs) encoded by genes ADCY1-9 and soluble adenylyl cyclase (sAC) encoded by a single gene, ADCY10.17–20 tmACs are regulated at the plasma membrane by heterotrimeric G proteins downstream from hormonally regulated G protein coupled receptors. sAC is not membrane bound and can be localized within the cytoplasm, mitochondria, and nucleus.21,22 sAC is the only adenylyl cyclase regulated by bicarbonate (HCO3−) anions.23,24

Mittag et al. reported that rabbit ciliary body epithelium cells from the eye contain a bicarbonate-sensitive adenylyl cyclase.25 In NPE cells, which produce aqueous humor, sAC generated cAMP was elevated following CAI treatment.26 sAC was shown to be present in ocular tissues, including the ciliary body,27 and IOP was elevated in sAC knockout (KO) mice.13 These findings raised the intriguing possibility that sAC mediates the IOP lowering effects of CAIs. In this study, we sought to determine whether a second generation CAIs, brinzolamide, clinically used to lower IOP,28 requires sAC to lower intraocular pressure (IOP) in mice. We assessed the effects of brinzolamide treatment in mice devoid of sAC by leveraging both sAC knock-out mice and a recently described potent sAC inhibitor designed to interrogate the in vivo functions of sAC.28

Methods

The sAC inhibitor TDI-10229 was synthesized and characterized as described in Fushimi et al.29

In vitro cyclase activity assay with purified sAC protein

Assays for sAC catalytic activity were performed with purified human protein in 100 μL reactions containing 4 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2,1 mM ATP, 40 mM NaHCO3, 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, and 3 mM dithiothreitol. Each reaction contained about 1,000,000 counts of α-32P labeled ATP. The cAMP generated was purified using sequential Dowex and Alumina chromatography utilizing the “two-column” method developed by Salomon.30

Cellular cyclase activity assay in sAC overexpressing (4-4) cells

Cells stably overexpressing sAC (4-4 cells) were generated and functionally authenticated in our laboratory as previously described.31 For this assay, 1.00 × 105 cells were seeded per well of a 24-well plate in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium +10% fetal bovine serum media at 37°C/5% CO2. One hour before the assay, the media was aspirated and replaced with 300 μL of new media. For 10 min, in duplicate wells, cells were preincubated with all inhibitors (brinzolamide, acetazolamide, TDI-10029) at the indicated concentrations or dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) as control at 37°C/5% CO2. For initiating cAMP accumulation, cells were incubated with a phosphodiesterase inhibitor cocktail of 500 μM 3-isobutyl-methylxanthine and 30 μM dipyridamole for 10 min.

To stop the reaction and lyse the cells, the media was aspirated and replaced with 250 μL of 0.1 M HCl. After shaking the plate for 5 min, the 24-well plate was centrifuged at 1,000g for 5 min. The supernatant was used for cAMP quantification using the Direct cAMP Elisa kit (Enzo Life Sciences) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Animal models and study approval

All animal procedures were conducted with approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Weill Cornell Medicine (New York, NY). Mice were bred and housed at the animal facility of Weill Cornell Medicine under a regular 12-h light–12-h dark cycle. Standard rodent chow and water were available ad libitum. As reported previously, sAC-C1KO (Sacytm1Lex/Sacytm1Lex) mice were generated by homologous recombination using an IRES-lacZ expression cassette replacing exons 2–4.32,33 This KO design results in the C1 catalytic domain of sAC being interrupted.32,33 C57BL/6J was the background strain for all KO and wild-type (WT) mice. Exclusively male and age-matched controls, 10–12 weeks, were used for all procedures.

Mice were injected intraperitoneally (IP) with TDI-10229 dissolved in DMSO (20 mg/kg) and DMSO alone. To avoid subjecting mice to repeated injections, we avoided using acetazolamide and instead focused on the topically applied, clinically relevant brinzolamide. For topical administration, mice were manually constrained, and 1 drop (15 μL) of clinical grade brinzolamide (Azopt® 10 mg/mL) was applied to both eyes of each mouse. IOP readings were taken 1 h after drug administration. All procedures were performed between 10 am and 2 pm to avoid diurnal variation in eye pressure.34

IOP measurement by direct cannulation

IOP is a measure of the eye's internal pressure. While IOP varies during the day, we measured between 10 am and 2 pm to remain consistent with previous studies of the effect of sAC on IOP in vivo.13,35 Anterior chamber cannulation was used to determine the IOP of mice as described by others.13,35,36 This method has been reported to be the most sensitive in measuring IOP in mice receiving anesthesia with systemically administered DMSO solubilized compounds.35 Mice were adequately anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) by IP injection before beginning the procedure. The depth of anesthesia was assessed by pressure stimuli (pinch) to a hind foot or back skin before placement on the platform used for the procedure.

Loss of consciousness and no response to touch were considered adequate. The eye's anterior chamber was cannulated using a 33-gauge stainless steel needle (TSK Steriject). This cannula was inserted anterior to the limbus and through the cornea. Once a stable reading was obtained, the cannula was withdrawn. The cannula was connected to a pressure transducer using a Teflon tube and calibrated to a water height equivalent of 0 mmHg. The transducer signal was amplified (Bridge8 amplifier; World Precision Instruments), converted to a digital signal (Lab-TRAX-4 converter; World Precision Instruments), and the voltage was recorded on a computer using LabScribe 3 software. This apparatus was calibrated using a fluid reservoir, in which the height could be adjusted to generate a series of known pressure. The IOP was calculated by comparing the change in voltage to a standard calibration curve generated at the end of each experiment using a water height column.

Data analysis and statistics

Excel and GraphPad Prism 9 software were used to analyze all data acquired. A P value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. The significance levels were marked by asterisks (*): *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; and ****P < 0.0001. The IOP measurements are presented using box plots where at least 75% of measured values fall within the box, with the remaining values in the range indicated by error bars. A 1-way analysis of variance was performed to compare groups.

Results

Previous work demonstrating that sAC activity in NPE cells can be stimulated by CAI treatment, used the broad specificity CAIs acetazolamide.26 We first asked whether the second generation and clinically relevant CAII selective inhibitor, brinzolamide, would similarly affect intracellular sAC-dependent cAMP accumulation. To focus exclusively on sAC-dependent cAMP accumulation inside cells, we leveraged 4-4 cells, whose intracellular cAMP accumulation is almost exclusively due to stably overexpressed sAC.31 Acetazolamide and brinzolamide stimulated cAMP accumulation in 4-4 cells (Fig. 1). We confirmed that the cAMP increase was due to stimulation of sAC in 2 ways. First, the intracellular cAMP accumulation is measured in the presence of a cocktail of phosphodiesterase inhibitors (IBMX and Dipyridamole), confirming that the cAMP elevation is not due to decreased degradation by phosphodiesterases. Second, the CAI-dependent increases were blocked by inclusion of the potent and selective sAC inhibitor TDI-10229, confirming that inhibition of CAIs stimulate sAC activity.

FIG. 1.

The concentration of cAMP in sAC-overexpressing 4-4 cells. Cellular accumulation of cAMP was measured in cells pretreated with inhibitors for 10 min followed by treatment with 500 μM IBMX and 30 μM DP (IBMX+DP) for 10 min, mean ± SEM (n = 3). DP, dipyridamole; cAMP, cyclic 3′, 5′ adenosine monophosphate; sAC, soluble adenylyl cyclase; SEM, standard error of the mean.

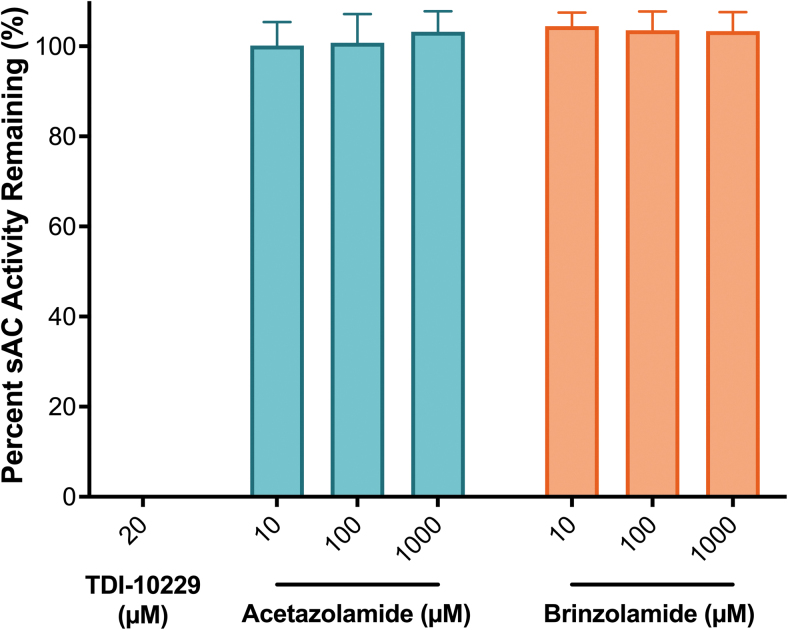

To examine whether the CAIs affect sAC activity directly, we measured in vitro cyclase activity of purified sAC protein. To demonstrate the dynamic range of the assay, we confirm that the recently described sAC-specific inhibitor, TDI-10229, when used at 20 μM, which is 100-fold above its IC50,29 completely inhibits in vitro sAC activity (Fig. 2). Neither acetazolamide nor brinzolamide affected in vitro activity of purified sAC protein; therefore, we conclude that the stimulation of sAC-dependent activity observed in cellular contexts (Fig. 1) occurred via modulation of intracellular HCO3− concentrations.

FIG. 2.

The concentration-response of TDI-10229, a potent and selective sAC inhibitor,29 acetazolamide (green) and brinzolamide (orange) on purified recombinant human sAC protein in the presence of 1 mM ATP, 2 mM Ca2+, 4 mM Mg2+, and 40 mM HCO3−, normalized to the respective DMSO-treated control; mean ± SEM (n = 3). ATP, adenosine triphosphate; DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide.

We next examined the effects of carbonic anhydrase inhibition in vivo. Both acetazolamide and brinzolamide affect sAC activity inside cells via a similar mechanism, and to avoid having to multiply inject subject animals, we used the topically applied brinzolamide instead of the injected CAI acetazolamide. We measured IOP in mice via direct cannulation of the anterior chamber. The average IOP of WT mice was 10.58 ± 1.778 mmHg (mean ± standard deviation [SD], Fig. 3), and as expected, 1 h after treatment with a clinically approved topical eye drop formulation of brinzolamide, IOP was reduced to a mean value of 9.29 ± 1.945 mmHg (mean ± SD, Fig. 3). Consistent with previous reports,35,37 the mean IOP of sAC KO mice was elevated relative to WT mice to 11.79 ± 2.862 mmHg (mean ± SD, Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Brinzolamide decreases IOP in both WT and sAC KO mice. IOP was measured in WT (sAC+/+, C57BL/6J) or KO (sAC−/−) mice after 1 h treatment with topical brinzolamide (1 drop (15 μL) of 10 mg/mL). The line indicates mean. n = 101 sAC+/+, n = 26 sAC+/+ with brinzolamide, n = 27 sAC−/−, n = 12 sAC−/− with brinzolamide. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. IOP, increased intraocular pressure; KO, knockout; WT, wild-type.

Surprisingly, the ability of the CAI brinzolamide to reduce IOP was unaffected by the absence of sAC; the average IOP of sAC KO mice with brinzolamide was reduced to 9.67 ± 2.100 mmHg (mean ± SD, Fig. 3), which is indistinguishable from the IOP level in WT mice treated with brinzolamide.

Multiple published reports characterizing sAC KO mice describe no reported abnormal structural defects which could affect IOP in sAC KO mice.13,19,32,38 However, we were concerned that sAC KO mice may have adapted to the absence of sAC and developed adaptations permitting sAC-independent regulation of IOP. Therefore, we also pursued a pharmacological approach to inhibiting sAC in vivo. Previous reports demonstrated that 2 different sAC-specific inhibitors, KH713 and LRE1,35 elevate IOP in vivo. Both inhibitors suffer from liabilities; KH7 has been shown to uncouple mitochondria, and LRE1 has poor in vivo pharmacokinetics.29,39

Our laboratory has used structure-based drug design starting with the LRE1 scaffold to develop a second-generation sAC-specific inhibitor, TDI-10229.29 TDI-10229 is ∼20 × more potent than LRE1 on sAC protein (Table 1) and in cellular contexts, it displayed characteristics defining it as the more favorable compound to use as an in vivo tool.29 TDI-10229 is highly selective for sAC versus other nucleotidyl cyclases (specifically tmACs), and showed an overall benign safety profile, both in vitro and in vivo, and no significant cytotoxicity.29 The pharmacokinetic profile showed sustained bioavailability assessed by blood levels starting at 1 h postinjection, which is better suited for studying the acute effects of sAC inhibition on CAI-mediated IOP regulation. Using TDI-10229, we could assess the role of sAC in CAI-mediated IOP regulation 1 h after injection.

Table 1.

Soluble Adenylyl Cyclase Inhibitor Effects on Increased Intraocular Pressure

| sAC inhibitor | Cellular IC50 (μM) | Dosage and time | IOP (mmHg) | Relative increase in IOP | Significance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KH71 | 9.415 | 5 μmol/kg 3–4 h later |

14.60 ± 1.52 | 1.194 | P < 0.005 | 13 |

| KH71 | 9.415 | 1.25 mM in 4 mL/kg 2 h later |

14.4 ± 2.1 | 1.297 | P = 0.003 | 35 |

| KH72 | 9.415 | 1.25 mM in 4 mL/kg 2 h later |

14.4 ± 1.0 | 1.27 | P < 0.001 | 35 |

| LRE11 | 3.238 | 1.25 mM in 4 mL/kg 2 h later |

15.6 ± 3.5 | 1.289 | P = 0.002 | 35 |

| TDI-102293 | 0.1586 | 20 mg/kg 1 h later |

11.89 ± 1.72 | 1.149 | P < 0.0001 |

Note: Anesthesia; 1Avertin, 2Ketamine, Xylazine, Acepromazine, 3Ketamine, Xylazine.

IOP, increased intraocular pressure; sAC, soluble adenylyl cyclase.

While injection of the vehicle alone (i.e., DMSO) did not significantly affect IOP (10.34 ± 1.412 mmHg; mean ± SD, Fig. 4), injection of TDI-10229 (20 mg/kg) elevated IOP of WT mice to an average pressure of 11.89 ± 1.721 mmHg (mean ± SD, Fig. 4) 1 h after injection. The change in IOP with TDI-10229 is within the range of net changes in IOP previously observed using sAC inhibitors (KH7 and LRE1) in Table 1. As seen in sAC KO mice, brinzolamide treatment reduced IOP independent of sAC. The mean IOP for brinzolamide treatment of DMSO-injected mice was lowered to 9.130 ± 1.515 mmHg (mean ± SD, Fig. 4) and to 8.539 ± 1.607 mmHg (mean ± SD, Fig. 4) in TDI-10229-injected mice. Together, these genetic and pharmacologic data reveal that the absence of sAC does not impact the ability of the clinically used CAI brinzolamide to modulate IOP.

FIG. 4.

Administration of brinzolamide decreases IOP in both vehicle and TDI-10229-treated wild-type mice (sAC+/+, C57BL/6J). IOP was measured in mice IP injected with vehicle (DMSO) or TDI-10229 (20 mg/kg) and treated topically with vehicle or brinzolamide [1 drop (15 μL) of 10 mg/mL]. The line indicates mean. n = 52 sAC+/+ with DMSO, n = 30 sAC+/+ with DMSO + brinzolamide, n = 29 TDI-10229 sAC+/+, n = 15 sAC+/+ with TDI-10229 + brinzolamide. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001. IP, intraperitoneally.

Discussion

Reducing IOP remains an effective treatment strategy for preventing glaucoma. Carbonic anhydrases regulate the production of aqueous humor within the eye. CAIs, which affect the equilibrium between several inter-related effectors (i.e., pH, CO2, HCO3−) reduce IOP, but their mechanism of action remains poorly understood. There are several carbonic anhydrase isoenzymes shown to be expressed in NPE that can be selectively inhibited.5,9–12 Acetazolamide, a first-generation heterocyclic sulfonamide, that has been systemically used to manage glaucoma inhibits several CA isoforms within the eye. Subsequent generation CAIs, such as brinzolamide, currently used to treat glaucoma are selective for CA-II.

Previous studies identified a link between acetazolamide and intracellular levels of the second messenger cAMP.26 Treatment of NPE cells with acetazolamide, a nonspecific CAI, elevated intracellular cAMP, and the cAMP rise was shown to be dependent upon HCO3− regulated sAC.26 These findings led to the hypothesis that CAIs might function therapeutically by increasing HCO3− in the PE and NPE, which would activate sAC to elevate cAMP and reduce IOP. Here, we show that CAI exposure can also increase sAC mediated cAMP by in a cell line that overexpresses sAC (Fig. 1), and we show that both acetazolamide and brinzolamide stimulate sAC-mediated cAMP production inside cells. Thus, the ability to stimulate intracellular sAC activity is conserved between acetazolamide and the isoform-selective CAIs brinzolamide.

To assess whether CAI regulation of sAC impacts IOP in vivo, we tested whether sAC activity is necessary for CAIs to reduce IOP in mice in an intact eye using anterior cannulation. We opted to focus exclusively on brinzolamide for our in vivo studies because it is considered a specific, noncompetitive inhibitor of CA-II, and because it is topically applied, we can avoid repeated injections of treated mice. In both sAC KO mice as well WT mice, in the presence of pharmacological inhibitor TDI-10229 which completely blocks sAC activity,29,40 CAI treatment lowered IOP. Thus, the sAC-dependent cAMP cascade appears to be unnecessary for CAI modulation of IOP in an intact eye.

If CAI treatment does not require sAC, how does it lower IOP? Carbonic anhydrase activity is known to influence the availability of HCO3− and H+, which are thought to affect the activities of various signaling cascades and/or ion cotransporters or exchangers which modulate eye pressure. Modulating carbonic anhydrases has been shown to have a functional role in maintaining cytoplasmic pH in cultured NPE cells.41 Transport of HCO3− across the ciliary epithelium influences the pH necessary for active ion transport. Aqueous humor production is an energy-dependent process relying on active transport generated from the hydrolysis of ATP to ADP by the Na+-K+-ATPase.42 Further, NPE also expresses HCO3−- and H+-dependent signaling cascades such as the chloride–bicarbonate exchanger (AE2), sodium–bicarbonate cotransporter (kNBC1), and sodium–hydrogen exchangers (NHE1 and NHE4).5,26 Reducing transepithelial potential in NPE cells by any of these mechanisms following administration of a CAIs may impact IOP.41

Our study continues to demonstrate the value of improving the efficacy of sAC inhibitors for in vivo animal testing. Future compound development of topical sAC inhibitors would be essential to evaluate whether this is an effective therapeutic target for improving hypotony, a rare condition where IOP is too low. Currently, sAC inhibitors are being investigated as a potential on-demand nonhormonal contraceptive for men.43,44 It will be necessary to identify whether acutely inhibiting sAC would affect IOP in humans, and this study provides a framework for investigations into eye phenotypes in human safety trials of sAC inhibitors. However, the data presented here reveal that a sAC inhibitor contraceptive may not adversely affect the efficacy of glaucoma treatment with CAIs.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Buck-Levin Laboratory and Therapeutics Discovery Institute for helpful discussions during the course of this work.

Authors' Contributions

S.V.W.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, and writing—original draft and review and editing. J.F.: methodology and investigation. R.S.: methodology and investigation. A.D.M.: methodology. L.R.L.: conceptualization, supervision, writing—review and editing, and funding acquisition. J.B.: conceptualization, supervision, writing—review and editing, and funding acquisition.

Author Disclosure Statement

L.R.L. and J.B. are cofounders of Sacyl Pharmaceuticals, Inc., established to develop sAC inhibitors into on-demand contraceptives. All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Funding Information

NICHD grants to L.R.L. and J.B. (HD100549 and HD088571).

References

- 1. Maren TH. Carbonic anhydrase inhibition in ophthalmology: Aqueous humor secretion and the development of sulfonamide inhibitors. In: The Carbonic Anhydrases. (Chegwidden WR, Carter ND, Edwards YH. eds.) Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland; 2000; pp. 425–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Becker B. Decrease in intraocular pressure in man by a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, diamox; a preliminary report. Am J Ophthalmol 1954;37(1):13–15; doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(54)92027-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Larsson LI, Alm A. Aqueous humor flow in human eyes treated with dorzolamide and different doses of acetazolamide. Arch Ophthalmol 1998;116(1):19–24; doi: 10.1001/archopht.116.1.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Scozzafava A, Supuran CT. Glaucoma and the applications of carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Subcell Biochem 2014;75:349–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shahidullah M, To C-H, Pelis RM, et al. Studies on bicarbonate transporters and carbonic anhydrase in porcine nonpigmented ciliary epithelium. Investig Opthalmol Vis Sci 2009;50(4):1791; doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Maren TH. The kinetics of HCO3- synthesis related to fluid secretion, pH control, and CO2 elimination. Ann Rev Physiol 1988;50(1):695–717; doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.50.030188.003403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Goel M. Aqueous humor dynamics: A review. Open Ophthalmol J 2010;4(1):52–59; doi: 10.2174/1874364101004010052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Supuran CT. Structure and function of carbonic anhydrases. Biochem J 2016;473(14):2023–2032; doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Liao SY, Ivanov S, Ivanova A, et al. Expression of cell surface transmembrane carbonic anhydrase genes CA9 and CA12 in the human eye: Overexpression of CA12 (CAXII) in glaucoma. J Med Genet 2003;40(4):257–261; doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.4.257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wu Q, Delamere NA, Pierce W Jr. Membrane-associated carbonic anhydrase in cultured rabbit nonpigmented ciliary epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1997;38(10):2093–2102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Matsui H, Murakami M, Wynns GC, et al. Membrane carbonic anhydrase (IV) and ciliary epithelium. Carbonic anhydrase activity is present in the basolateral membranes of the non-pigmented ciliary epithelium of rabbit eyes. Exp Eye Res 1996;62(4):409–417; doi: 10.1006/exer.1996.0046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wistrand PJ, Schenholm M, Lonnerholm G. Carbonic anhydrase isoenzymes CA I and CA II in the human eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1986;27(3):419–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lee YS, Tresguerres M, Hess K, et al. Regulation of anterior chamber drainage by bicarbonate-sensitive soluble adenylyl cyclase in the ciliary body. J Biol Chem 2011;286(48):41353–41358; doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.284679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Camp AS, Ruggeri M, Munguba GC, et al. Structural correlation between the nerve fiber layer and retinal ganglion cell loss in mice with targeted disruption of the Brn3b gene. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52(8):5226–5232; doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ramachandran C, Satpathy M, Mehta D, et al. Forskolin induces myosin light chain dephosphorylation in bovine trabecular meshwork cells. Curr Eye Res 2008;33(2):169–176; doi: 10.1080/02713680701837067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ramachandran C, Patil RV, Sharif NA, et al. Effect of elevated intracellular cAMP levels on actomyosin contraction in bovine trabecular meshwork cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52(3):1474–1485; doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Buck J, Sinclair ML, Schapal L, et al. Cytosolic adenylyl cyclase defines a unique signaling molecule in mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999;96(1):79–84; doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.1.79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zippin JH, Levin LR, Buck J. CO(2)/HCO(3)(-)-responsive soluble adenylyl cyclase as a putative metabolic sensor. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2001;12(8):366–370; doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(01)00454-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hess KC, Jones BH, Marquez B, et al. The “soluble” adenylyl cyclase in sperm mediates multiple signaling events required for fertilization. Dev Cell 2005;9(2):249–259; doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dessauer CW, Watts VJ, Ostrom RS, et al. International union of basic and clinical pharmacology. CI. Structures and small molecule modulators of mammalian adenylyl cyclases. Pharmacol Rev 2017;69(2):93–139; doi: 10.1124/pr.116.013078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zippin JH, Chen Y, Nahirney P, et al. Compartmentalization of bicarbonate-sensitive adenylyl cyclase in distinct signaling microdomains. FASEB J 2003;17(1):82–84; doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0598fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Acin-Perez R, Salazar E, Kamenetsky M, et al. Cyclic AMP produced inside mitochondria regulates oxidative phosphorylation. Cell Metab 2009;9(3):265–276; doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen Y, Cann MJ, Litvin TN, et al. Soluble adenylyl cyclase as an evolutionarily conserved bicarbonate sensor. Science 2000;289(5479):625–628; doi: 10.1126/science.289.5479.625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kleinboelting S, Diaz A, Moniot S, et al. Crystal structures of human soluble adenylyl cyclase reveal mechanisms of catalysis and of its activation through bicarbonate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111(10):3727–3732; doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322778111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mittag TW, Guo WB, Kobayashi K. Bicarbonate-activated adenylyl cyclase in fluid-transporting tissues. Am J Physiol 1993;264(6 Pt 2):F1060–F1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shahidullah M, Mandal A, Wei G, et al. Nonpigmented ciliary epithelial cells respond to acetazolamide by a soluble adenylyl cyclase mechanism. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2014;55(1):187–197; doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sun XC, Zhai CB, Cui M, et al. HCO(3)(-)-dependent soluble adenylyl cyclase activates cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in corneal endothelium. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2003;284(5):C1114–C1122; doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00400.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Supuran CT. Emerging role of carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Clin Sci (Lond) 2021;135(10):1233–1249; doi: 10.1042/CS20210040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fushimi M, Buck H, Balbach M, et al. Discovery of TDI-10229: A potent and orally bioavailable inhibitor of soluble adenylyl cyclase (sAC, ADCY10). ACS Med Chem Lett 2021;12(8):1283–1287; doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.1c00273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Salomon Y. Adenylate cyclase assay. Adv Cyclic Nucleotide Res 1979;10;35–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zippin JH, Chen Y, Straub SG, et al. CO2/HCO3(-)- and calcium-regulated soluble adenylyl cyclase as a physiological ATP sensor. J Biol Chem 2013;288(46):33283–33291; doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.510073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Esposito G, Jaiswal BS, Xie F, et al. Mice deficient for soluble adenylyl cyclase are infertile because of a severe sperm-motility defect. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004;101(9):2993–2998; doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400050101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Farrell J, Ramos L, Tresguerres M, et al. Somatic ‘soluble’ adenylyl cyclase isoforms are unaffected in Sacy tm1Lex/Sacy tm1Lex ‘knockout’ mice. PLoS One 2008;3(9):e3251; doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Savinova OV, Sugiyama F, Martin JE, et al. Intraocular pressure in genetically distinct mice: An update and strain survey. BMC Genet 2001;2:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gandhi JK, Roy Chowdhury U, Manzar Z, et al. Differential intraocular pressure measurements by tonometry and direct cannulation after treatment with soluble adenylyl cyclase inhibitors. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 2017;33(8):574–581; doi: 10.1089/jop.2017.0027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Aihara M, Lindsey JD, Weinreb RN. Aqueous humor dynamics in mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2003;44(12):5168–5173; doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lee YS, Marmorstein AD. Control of outflow resistance by soluble adenylyl cyclase. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 2014;30(2–3):138-42; doi: 10.1089/jop.2013.0199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Xie F, Conti M. Expression of the soluble adenylyl cyclase during rat spermatogenesis: Evidence for cytoplasmic sites of cAMP production in germ cells. Dev Biol 2004;265(1):196–206; doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Acin-Perez R, Salazar E, Brosel S, et al. Modulation of mitochondrial protein phosphorylation by soluble adenylyl cyclase ameliorates cytochrome oxidase defects. EMBO Mol Med 2009;1(8–9):392–406; doi: 10.1002/emmm.200900046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Balbach M, Ghanem L, Rossetti T, et al. Soluble adenylyl cyclase inhibition prevents human sperm functions essential for fertilization. Mol Hum Reprod 2021;27(9):gaab054; doi: 10.1093/molehr/gaab054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wu Q, Pierce WM Jr., Delamere NA. Cytoplasmic pH responses to carbonic anhydrase inhibitors in cultured rabbit nonpigmented ciliary epithelium. J Membr Biol 1998;162(1):31–38; doi: 10.1007/s002329900339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Goel M, Picciani RG, Lee RK, et al. Aqueous humor dynamics: A review. Open Ophthalmol J 2010;4:52–59; doi: 10.2174/1874364101004010052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ferreira J, Levin LR, Buck J. Strategies to safely target widely expressed soluble adenylyl cyclase for contraception. Front Pharmacol 2022;13:953903; doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.953903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Balbach M, Rossetti T, Ferreira J, et al. On-demand male contraception via acute inhibition of soluble adenylyl cyclase. Nat Commun 2023;14(1):637; doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-36119-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]