Abstract

Neurodegenerative diseases are posing pressing health issues due to the high prevalence among aging populations in the twenty-first century. They are evidenced by the progressive loss of neuronal function, often associated with neuronal necrosis and many related devastating complications. Nevertheless, effective therapeutical strategies to treat neurodegenerative diseases remain a tremendous challenge due to the multisystemic nature and limited drug delivery to the central nervous system (CNS). As a result, there is a pressing need to develop effective alternative therapeutics to manage the progression of neurodegenerative diseases. By utilizing the functional reconstructive materials and technologies with specific targeting ability at the nanoscale level, nanotechnology-empowered medicines can transform the therapeutic paradigms of neurodegenerative diseases with minimal systemic side effects. This review outlines the current applications and progresses of the nanotechnology-enabled drug delivery systems (DDS) to enhance the therapeutic efficacy in treating neurodegenerative diseases.

Keywords: Nanotechnology, Neurodegenerative diseases, Drug delivery, Central nervous system (CNS), Blood brain barrier (BBB)

1. INTRODUCTION

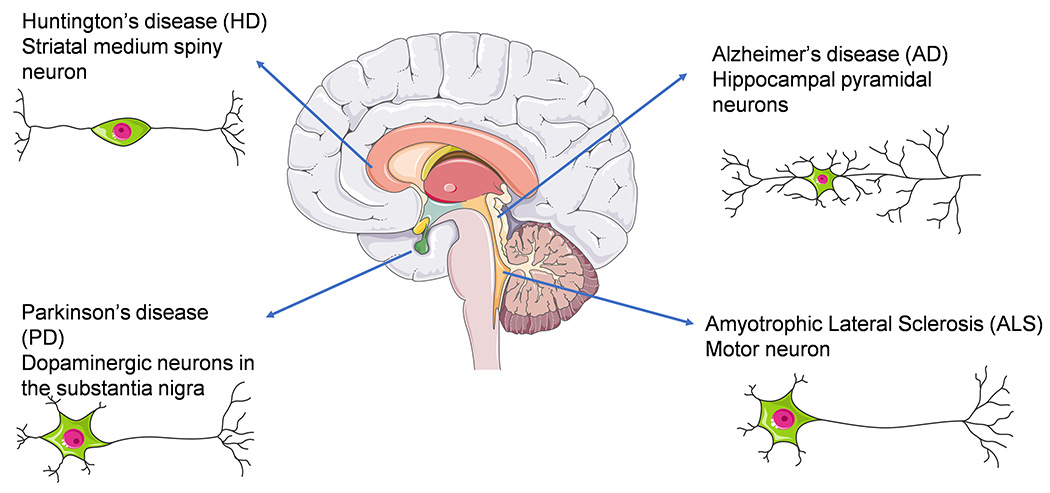

In recent history, neurodegenerative diseases were found to be contributing factors in 6.3% of all diseases worldwide(Akhtar et al., 2021). Specifically, nearly 1.5 billion individuals experience this universal effect as a result of some type of neurodegenerative disease (Barchet & Amiji, 2009). Considering the growth rate of the aging population, the World Health Organization predicts that the morbidity of neurodegenerative disease subjects will triple, surpassing cancer as the second highest disease-related mortality over the next three decades (Asefy et al., 2021; Chang et al., 2014). Neurodegenerative diseases are distinguished by progressive neuronal loss of function, often associated with neuronal necrosis (Fernandes et al., 2010), with some examples including ubiquitous Alzheimer’s disease (AD), widespread Parkinson’s disease (PD), Huntington’s disease (HD), as well as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, Figure 1)(Skovronsky et al., 2006). Despite comprehensive research focus on such diseases, there is currently no effective treatments or pharmacologic agents that arrest disease progression for patients suffering from neurodegenerative disorders. The present therapies aim at alleviating symptoms and/or providing palliative care rather than attempting to target the disease itself (Pieper et al., 2014). Moreover, due to the present need for lifelong therapy with high drug dosage frequency to treat neurological diseases, the quality of life of patients is significantly diminished and many suffer from severe side effects. Therefore, the urgency to develop a treatment that can effectively impact the course of neurodegeneration is apparent(Wang et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2018; Wang, Wang, Wang, et al., 2015).

Figure 1.

The most common neurodegenerative diseases and corresponding types of affected neurons.

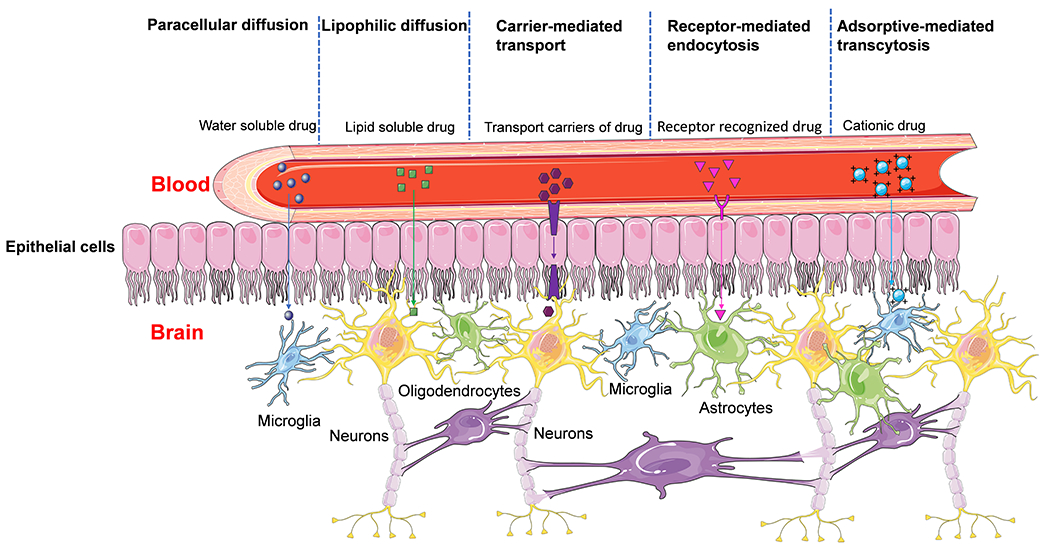

Nevertheless, neurodegenerative diseases are convoluted and multi-layered in nature which presents tremendous challenges in developing an effective therapeutic for these disorders. Worse still, the constraint of a series of physiological barriers, especially the blood-brain barrier (BBB), have prohibited 98% of prospective pharmaceuticals and can lead to peripheral adverse effects upon the release of pharmacokinetics (Lockman et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2014). The BBB resides at the interface between the blood capillaries and brain, which is formed by the brain capillary endothelium and surrounding cells, including tight junctions, astrocytes and neurons (Figure 2)(Oller-Salvia et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016). The main functions of the BBB are to endow a fully autonomous environment for the CNS (Rapoport et al., 1978), supply the brain with nutrients, and impede the noxious chemicals and harmful substance insults by sophisticated transport systems (Sanovich et al., 1995). The BBB helps to deter the CNS from foreign substances and maintains central nervous system (CNS) homeostasis, which is the most efficacious pathway to deliver drugs into the CNS (Lockman et al., 2002). In fact, the greatest distance between the cell and capillary is around 20 μm inside the BBB, which enables penetration by only small hydrophobic drugs (< 500 Da) that are able to permeate the endothelium membrane through paracellular diffusion in half a second (Oller-Salvia et al., 2016). Nevertheless, the abilities of drugs to penetrate the BBB are greatly restricted by the efflux transporters in the luminal membrane of brain endothelial cells. The five modes of drug release by which chemicals traverse the BBB are: water soluble molecules that transport into the BBB via tight juncture (paracellular diffusion), lipid-soluble molecules that diffuse transcellular lipoid bilayer membrane transport (lipophilic diffusion), transport carriers that mediate machineries of small molecules and peptides (carrier-mediated transport), and adsorptive-mediated transcytosis of cationic drug and specific receptor-mediated endocytosis and transcytosis (Akhtar et al., 2021; Bhattacharya et al., 2022). In fact, for some certain macromolecules and peptides, the molecules can effectively penetrated the BBB by endocytic manners associating receptor mediated transcytosis (RMT) and/or adsorptive-mediated transcytosis (AMT)(Oller-Salvia et al., 2016). Therefore, engineering nanoparticles with contriving surface modifications can be utilized to target and penetrate the BBB with lengthened blood circulation.

Figure 2.

Five main modes of drug traverse the BBB.

Over the past decades, there has been a heightened urgency to develop nanotechnology and provide more efficacious therapy in treating of CNS diseases. The advantage of nanotechnology was attributed to its capacity to deliver drugs displaying controlled release and target site-specific drug delivery, which often result in ameliorated therapeutic efficacy and mitigated bleak adverse effects(Zhiren Wang et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2021). The most crucial factors in obtaining significant therapeutic index and clinical success were selectivity, maximal tolerated dose (MTD) as well as the retention of blood circulation(Z. Wang et al., 2022). The optimal nanoparticle is biocompatible with mitigated toxicity and possesses the capacity to load and deliver drugs or therapeutics (Kumar et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). There are many favorable advantages by incorporating nanotechnology in the pharmaceutic platform, which include the extensive capacity in drug-loading to lengthen the drug’s blood circulation and mitigate the potential adverse effects and excellent surface area-to-size ratio to edit the ability of using effective passive drug-targeting methods with sustainable medical dosing options (Bhattacharya et al., 2022). Surface modification of nanomaterials with functionalization can be utilized to penetrate the BBB, which includes the zeta potential, morphology, hydrophobicity as well as the chemical ligand. Using blood-brain barrier shuttle peptides as transcytosis target to modify the surface of nanoparticles, molecular vectors have proven significant potential in preclinical research over the last two decades(Oller-Salvia et al., 2016). Cationization can effectively induce adsorption-mediated transcytosis (AMT) and facilitate nanocarriers to penetrate across multiple cell layers(Akinc et al., 2019). To avoid the fast clearance in the circulation and the opsonization induced by the cationic charges, charge reversal has emerged as an effective technology to achieve in vivo cationization-triggered target tissue penetration of nanomedicine. This strategy enabled cationization of the nanoparticles at the luminal endothelial cell surface while keeping the formulation neutral or slightly anionic during circulation(Zhou et al., 2019). In addition, via mimicking nanodiscs, high-density lipoprotein holds considerable promise to achieve delivery of bioactive compounds into cerebrum(Kadiyala et al., 2019). Furthermore, using sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P)-signaling molecules as active targeting lipid ligands, the S1PR-targeted liposome successfully achieved BBB penetration and targeted delivery of a complex multicomponent drug regimen(Liu et al., 2021). Considering of all these factors, the delivery of drugs into the CNS through permeation of the BBB via nanotechnology would provide a remarkable approach to combat this issue. This review outlines and discusses the state-of-the-art of current applications of nanotechnology in the treatment of the most prevalent neurodegenerative diseases.

2. NANOTECHNOLOGY-EMPOWERED THERAPEUTICS IN ALZHEIMER’S DISEASES

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most prevalent and chronic type of neurodegenerative diseases, accounts for over 50% of dementia morbidity with approximately 55 million patients worldwide(Gauthier et al., 2021). In the United States, AD holds the sixth leading cause of mortality within those over the age of 65, which affects 5.8 million citizens and the number was anticipated to rise to 13.8 million in 2050 if no potent interventions are developed(Cummings et al., 2021).

The pathology of AD was multi-layered and convoluted, and can be distinguished by aberrant extracellular amyloid-β (Aβ) plaque formation amidst the neuronal cells, neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) generation inside the cells, and neuronal loss(Amemori et al., 2015; Mostafavi et al., 2018). Since in the mid-1980s, Aβ and tau were successfully identified as the dominant composition of senile plaques and tangles by pathologists, which has been elucidated by detailed knowledge of amyloid precursor protein (APP) metabolism in subsequent research efforts (Blennow, 2010; Wang, Wang, Li, et al., 2015). The amyloidogenic proteolysis of APP by β-secretase (β-APP cleaving enzyme or BACE-1) followed by γ-secretase through cleavage and releases sAPPβ and Aβ(Hayne et al., 2014). Under the pathological mechanism of AD, the dysfunction between the formation and metabolization of Aβ peptide leading to the extracellular Aβ plaque deposits accumulation as oligomers, protofibrils, fibrils on the surface of neurons(Kotler et al., 2014). The amyloid cascade hypothesis was the prevailing hypothesis for AD pathogenesis, which deemed that the Aβ-induced excitotoxicity with plaque generation was the critical factor, ultimately resulting in neuronal degeneration and memory dysfunction(Amiri et al., 2013). Tau protein was a kind of microtubule-associated protein, which presented in axons and dendrites and imparted structural integrity and stability to microtubules(Stern et al., 2019). The binding of tau to microtubules was modulated by kinases and phosphatases, which altered tau’s charge distribution(Savelieff et al., 2013). In AD, an imbalance between kinase and phosphatase activities results in accumulation and aggregation of chronically hyperphosphorylated tau (ptau)(Bussian et al., 2018). This insoluble state gave rise to irrecoverable detriments to cytoplasmic functions inside the neurons and a turbulence for axonal conduction, ultimately resulting in apoptosis of neurons and dementia(Agarwal et al., 2020). In addition, the decreases of neurotransmitter choline, oxidative stress, the dysregulation of metal ions in the brain may also act critical factors in the pathology of AD(Amemori et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2016). Thus, the disease was influenced by biological complexity and phenotypic heterogeneity, which may be the result of a variety of factors interacting(Mostafavi et al., 2018).

Currently, the primary therapeutic options approved by United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for AD were acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs), including donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine, the N-methyl-Daspartate (NMDA) receptor (NMDAR) antagonist, memantine, as well as the anti-Aβ monoclonal antibody, aducanumab(Dunn et al., 2021). However, these drugs can only provide short-term symptomatic relief by ameliorating memory and cognitive function, unable to cure this disease through disease-modifying therapies or treatments (DMTs)(Cummings et al., 2017). Consequently, there was an imminent unmet medical need to exploit new therapeutics in AD. Nevertheless, numerous latest clinical trials involving late-stage AD patients have failed, which may be ascribed to the enigmatic pathology and multi-layered potential hypotheses of AD(Altinoglu & Adali, 2020). Additionally, drug delivery into the target cerebral region for the treatment of AD was hindered by the BBB limitation, which limited the pharmacodynamics and therapeutics(Arya et al., 2019). Presently, the treatment of AD by using nanoparticles are demonstrated as better approaches for enhancing the therapeutical efficacies by indurating the pharmacokinetic accumulation of drugs inside the CNS(Arya et al., 2019; Kassem et al., 2020). Nanoparticles provide various types of formulation, which possess CNS-targeted and long circulation profiles with mitigated systemic side-effects and concurrent complications. A description of these studies’ results was here presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of nanotechnology-empowered therapeutics in AD

| Drug | Type of NPs | NPs material | BBB penetration targeting | Application model | Route of administration | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tacrine | Polymer | poly(n-butylcyanoacrylate) | Polysorbate 80 | Rats | Intravenous | (Wilson et al., 2008b) |

| Microemulsions | Labrafil M 1944 CS, Cremophor RH 40 and Transcutol P | Carbopol 934 P | Scopolamine-induced amnesic mice | Intranasal | (Jogani et al., 2008) | |

| Magnetic chitosan | Lin seed oil, Chitosan and neodymium magnet | External magnetic fields | Rats | Intravenous | (Wilson et al., 2009) | |

| Donepezil | Polymer | Chitosan | Cannula | Rats | Intranasal | (Bhavna et al., 2014) |

| PLGA | Polysorbate 80 | Rats | Intravenous | (Md, Ali, et al., 2014) | ||

| PLGA-b-PEG | NA | Human brain microvascular endothelial cells (HBMECs) | NA | (Baysal et al., 2017) | ||

| Emulsification | Glycerol mono-oleate and Poloxamer 407 | gellan gum and Konjac glucomannan | Rats | Intranasal | (Patil et al., 2019) | |

| Labrasol, cetyl pyridinium chloride and glycerol | NA | Rats | Intranasal | (Kaur, Nigam, Bhatnagar, et al., 2020) | ||

| Liposomes | 1,2-distearyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DSPC), cholesterol, PEG | NA | Rats | Intranasal | (Al Asmari et al., 2016) | |

| Dipalmitoylphosphocholine (DPPC) and cholesterol | NA | Rabbits | Intranasal | (Al Harthi et al., 2019) | ||

| Rivastigmine | Liposomes | PC, DCP, cholesterol | NA | AlCl3-induced AD rats | Subcutaneous | (Ismail et al., 2013) |

| Lecithin from soya and cholesterol | NA | Rats | Intranasal | (Arumugam et al., 2008) | ||

| EPC, cholesterol | DSPE-PEG-CPP | Rats | Intranasal | (Yang et al., 2013) | ||

| Lecithin, oleic acid, cholesterol | NA | Rats | Dermal | (Salimi et al., 2021) | ||

| DPPC, cholesterol | sodium-taurocholate | Mice | oral and intraperitoneal | (Değim et al., 2010; Mutlu et al., 2011) | ||

| Polymeric | Poly(n-butylcyanoacrylate) | Polysorbate 80 | Rats | Intravenous | (Wilson et al., 2008a) | |

| PLGA and PBCA | NA | Scopolamine-induced amnesic mice | Intravenous | (Joshi et al., 2010) | ||

| Chitosan | Chitosan, sodium tripolyphosphates (TPP) | NA | Rats | Intranasal | (Fazil et al., 2012) | |

| Solid lipid | Compritol 888 ATO | NA | Franz diffusion cell | Intranasal | (Shah et al., 2015) | |

| Huperzine A | Solid lipid | Capmul® MCM (glyceryl mono-dicaprylate), glyceryl monostearate | NA | Scopolamine induced rat amnesia | Skin application | (Patel et al., 2013) |

| PLGA | PLGA 5050 2A, chitosan | lactoferrin (Lf) | Mice | Intranasal | (Meng et al., 2018) | |

| Microspheres | PLA/PLG | NA | Rats | Subcutaneous | (Gao et al., 2006) | |

| Microspheres | PLG-H | NA | Rats | Subcutaneous | (Gao et al., 2007) | |

| Galantamine | Liposomes | DSPC, cholesterol, DSPE-PEG2000 | Peptide (Lys-Val-Leu-Phe-Leu-Ser) | EX vivo | NA | (Mufamadi et al., 2013) |

| Solid lipid | Glyceryl behenate lipid | NA | Isoproterenol induced cognitive deficits in rat | Oral | (Misra et al., 2016) | |

| Chitosan | Chitosan | Polysorbate 80 | Rats | Intranasal | (Hanafy et al., 2016) | |

| Hydroxyapatite | Calcium carbonate, mmonium dihydrogen phosphate, cerium sulphate, chitosan | NA | AlCl3-induced AD rats | Intraperitoneal | (Wahba et al., 2016) | |

| Memantine | Polymer | PLGA | Polyethylene glycol | Transgenic APPswe/PS1dE9 AD mice | Oral | (Sanchez-Lopez et al., 2018) |

| Nanoemulsion | Labrasol (oil), oleic acid, soybean oil | Tween 20 and igepal | Rats | Intravenous | (Kaur, Nigam, Srivastava, et al., 2020) | |

| Curcumin | Nanostructured lipid carriers | Lipid | NA | Scopolamine induced AD rats | Intranasal | (Sood et al., 2013) |

| Solid lipid | Compritol 888 ATO, Polysorbate 80, soy lecithin | NA | Cerebral ischemia (BCCAO model) in rat | Oral | (Kakkar et al., 2013) | |

| SLCP™ or Longvida® | NA | Mouse neuroblastoma cells | NA | (Maiti & Dunbar, 2017) | ||

| Longvida® | NA | hTau transgenic mice | Oral | (Ma et al., 2013) | ||

| Longvida® | NA | RAW 264.7 mouse macrophage cells | NA | (Nahar et al., 2015) | ||

| Longvida® | NA | Transgenic 5XFAD AD mice | Intraperitoneal | (Maiti et al., 2016) | ||

| Longvida® | NA | Older population (aged 60-85) | Oral | (Cox et al., 2015) | ||

| Longvida® | NA | Middle aged people (aged 40-60) | Oral | (DiSilvestro et al., 2012) | ||

| TMC, chitosan | NA | Mice | Oral | (Ramalingam & Ko, 2015) | ||

| LDL-mimic nanocarrier | S100-COOH, PC, cholesterol oleate, glycerol trioleate | NA | D-gal and Aβ induced AD rats | Intravenous | (Meng et al., 2015) | |

| Lipid-core nanocapsules | ε-caprolactone, grape seed oil, sorbitan monostearate | NA | Aβ induced AD rats | Intraperitoneal | (Hoppe et al., 2013) | |

| Micelles | Tween-80 | NA | NMRI mice | Oral | (Hagl et al., 2015) | |

| Liposomes | DSPC, cholesterol, DPS-PEG- Curcumin | Anti-Transferin antibody | BBB cellular model | NA | (Mourtas et al., 2014) | |

| DPPC, cholesterol, DPS-curcumin | NA | Transgenic APP/PS1 AD mice | Injection in the hippocampus | (Lazar et al., 2013) | ||

| SM, cholesterol, mal-PEG-PhoEth | ApoE peptides | RBE4 cell monolayer BBB model | NA | (Re et al., 2011) | ||

| SM, cholesterol, mal-PEG-DSPE | TAT peptide | Human brain capillary endothelial cells (hCMEC/D3) | NA | (Sancini et al., 2013) | ||

| SPC, cholesterol, DSPE-PEG(2000) | NA | Aβ induced AD rats | Intravenous | (Kuo et al., 2017) | ||

| PC, DPPC, DSPC, DPPG, cholesterol, Lipid-PEG- Curcumin | NA | Binding to Aβ42 | NA | (Mourtas et al., 2011) | ||

| Lecithin, cholesterol | NA | Aβ induced AD rats | Intranasal | (Sokolik et al., 2017) | ||

| Polymer | PLA, PVP | NA | Transgenic 2576 AD Mice | Oral | (Cheng et al., 2013) | |

| PLGA | NA | Aβ induced AD rats | Intraperitoneal | (Tiwari et al., 2014) | ||

| PBCN | NA | Mice | Intravenous | (Sun et al., 2010) | ||

| Eudragit® EPO | NA | Mice | Oral | (Kumar et al., 2016) | ||

| NIPAAM, VP, AA | NA | Mice | Intraperitoneal | (Ray et al., 2011) | ||

| Se-Nanospheres | Se-Cur/PLGA | NA | Transgenic 5XFAD AD mice | Intravenous | (Huo et al., 2019) | |

| Resveratrol | Lipid-Core Nanocapsules | poly(ε-caprolactone), capric/caprylic triglyceride, sorbitan monostearate | Polysorbate 80 | Aβ induced AD rats | Intraperitoneal | (Frozza et al., 2013) |

| poly(ε-caprolactone), capric/caprylic triglyceride, sorbitan monostearate | Polysorbate 80 | Rats | Intraperitoneal | (Frozza et al., 2010) | ||

| Mesoporous nano-selenium (MSe) | β-CD, MAH-β-CD | Borneol | Transgenic APP/PS1 AD mice | Intravenous | (Sun et al., 2019) | |

| Piperine | Chitosan | Chitosan, Poloxamer 188 | NA | Colchicine induced AD rats | Intranasal | (Elnaggar et al., 2015) |

| Solid lipid | GMS, PIP, Epikuron 200 | Polysorbate 80 | Ibotenic acid induced AD rats | Intraperitoneal | (Yusuf et al., 2013) | |

| Quercetin | Solid lipid | Compritol | Tween 80 | AlCl3-induced AD rats | Intravenous | (Dhawan et al., 2011) |

| Poloxamer-188, poloxamer, propylene glycol, stearic acid | NA | Zebrafish | Intraperitoneal | (Rishitha & Muthuraman, 2018) | ||

| Zein | Zein, lysine, HP-b-CD, mannitol | NA | SAMP8 and SAMR1 mice | Oral | (Moreno et al., 2017) | |

| Polymer | PLGA, PVA | NA | Transgenic APP/PS1 AD mice | Intravenous | (Sun et al., 2016) | |

| Coumarin | PEG-PLA | TQNP, H102 | NA | Transgenic APP/PS1 AD mice | Intravenous | (Zheng et al., 2017) |

| Erythropoietin | Solid lipid | Glycerin monostearate | Polysorbate 80 | Aβ induced AD rats | Intraperitoneal | (Dara et al., 2019) |

| BACE1-siRNA | Exosomes | Self-derived dendritic cells | Lamp2b | Mice | Intravenous | (Alvarez-Erviti et al., 2011) |

| RVG-9R and BACE1 siRNA | Solid lipid | Low-molecular-weight chitosan, viscosity 62 cP, polyvinyl alcohol | NA | Epithelial-like phenotypes | Intranasal | (Rassu et al., 2017) |

| CRISPR/Cas9 plasmids | Nano-biohybrid complexes | DOPA-PLys-PEG-Flu, DOPA-PLys-PEG-RVG | NA | Transgenic APPswe/PS1dE9 AD mice | Intravenous | (Shen et al., 2021) |

| Zinc | Polymer | PLGA 503H, g7-PLGA | Polyvinyl alcohol | Transgenic APP23 AD-like mice | Intraperitoneal | (Vilella et al., 2018) |

| Vitamin D binding protein (DBP) | Polymer | PLGA | Polyvinyl alcohol | Transgenic 5XFAD AD mice | Intravenous | (Jeon et al., 2019) |

| Neuroprotective peptide (NAPVSIPQ) | Polymer | PEG-PLA | B6 peptide | Aβ induced AD rats | Intravenous | (Liu et al., 2013) |

| Neuroprotective peptide | Lipoproteins | DMPC, ApoE3 | GM1-rHD | Aβ induced AD rats | Intranasal | (Huang et al., 2015) |

| ApoE3–rHDL | Lipoproteins | DMPC, ApoE3 | ApoE3-rHDL | Senescence-accelerated prone mouse (SAMP8) | Intravenous | (Song et al., 2014) |

| Nerve growth factor | Nano-ruthenium | Hollow nano-ruthenium | Photothermal effect | Okadaic acid induced AD mice | Intravenous | (Zhou et al., 2020) |

| Chondroitin sulphate | Nano-selenium | Nano-selenium | NA | D-gal/AlCl3-induced AD mice | Oral | (Ji et al., 2020) |

2.1. AChE inhibitors and NMDA receptor antagonist

The current approved therapeutics by the FDA for the treatment of AD are primarily AChE inhibitors, which were based on enzyme adaption of neurotransmitter(Cummings et al., 2021; Sood et al., 2014). Nevertheless, nonspecific toxicities of gastrointestinal side effects such as nausea and vomiting, are associated with AChE inhibitors, which always result in discontinuation of treatment(Colovic et al., 2013; Mehta et al., 2012).

Tacrine, the first drug to be widely marketed for treating the loss of memory and intellectual decline in Alzheimer’s disease, possesses a rapid circulation time and requires oral administration four times every day to achieve designed efficacy(Jann et al., 2002). Moreover, owing to the hepatotoxicity, routine blood tests were required for the patients who were administrated tacrine(Watkins et al., 1994), which led to withdraw from the market(Qizilbash et al., 2007). Several efforts in nanotechnology are developed for tacrine. Wilson et al (2008) investigated tacrine loaded polysorbate 80-coated poly(nbutyl cyanoacrylate) NPs(Wilson et al., 2008b). By comparison with free tacrine, the nanoparticles dramatically increased the drug concentration in liver, spleen and lung. Interestingly, the drug biodistribution in liver and spleen was decreased after coating the nanoparticles with 1% polysorbate 80. This coating modification of the nanoparticles significantly increased the tacrine concentration inside the brain in BBB penetration study. In another nanoparticle study by MPharm et al (2008), a quick absorption was observed through nose-to-brain delivery of tacrine-loaded microemulsions (MEs), which indicated twice as high as free drug by intranasal administration(Jogani et al., 2008). After the intranasal uptake of tacrine-loaded MEs, a considerable concentration of tacrine was delivered inside the cerebrum of scopolamine-induced amnesic mice, which promoted the fastest recovery of memory loss. By applying an exteriorly implemented magnet, Wilson et al (2009) also developed magnetic NPs delivery system based on chitosan(Wilson et al., 2009). By placing a magnet at the brain site, more than fivefold the concentration of tacrine in the cerebrum was detected in comparison with free drug after intravenous injection of the magnetite chitosan nano formulations into healthy rats.

Donepezil, the standard drug in the therapy of AD, improves memory, awareness, and the ability to function in AD patients(Contestabile, 2011). Donepezil-laden nanosuspension was developed by Bhavna et al (2014), which delivered into the cerebrum and determines no overt toxic properties in vivo(Bhavna et al., 2014). With the assistance of cannula, the chitosan-based nanoparticles were administered into the nostrils and significantly enhanced the drug accumulation in the cerebrum through nose to brain route. Donepezil loaded PLGA NPs were also studied by Bhavna et al (Md, Ali, et al., 2014), after coating with polysorbate 80 by the solvent emulsification diffusion-evaporation technique, the nanoparticles revealed sustained releasing and effective brain accumulation. Further studies demonstrated that a biphasic pattern profile of release was belong to the nanoparticles, which presented initial burst release and subsequent slower and continuous sustained release. The BBB penetration study in rats demonstrated that the significant concentrations of donepezil accumulation in cerebrum attributed to the coated NPs, therefore presenting that it may help significantly improve AD. In another polymeric nanoparticle developed by Baysal et al(Baysal et al., 2017), the PLGA-b-PEG nanoparticles were synthesized via double emulsion technology to load donepezil, which revealed the capability of penetration the BBB and indicated the properties of controlled release. The in vitro BBB model suggested that the concentration of IL-1b, IL-6, GM-CSF and TNF-α were considerably decreased in a dose-dependent manner under the presence of donepezil loaded nanoparticle. To further fortify the drug detention time inside the cavitas nasalis and facilitate donepezil penetration in the cerebrum, Patil et al developed mucoadhesive formulations by poloxamer 407 and glycerol mono-oleate(Patil et al., 2019). By comprising gellan and konjac gums, the optimized nanostructured cubosomal by situ nasal gel dispersion and mucoadhesive, which substantially boosted transnasal penetration and strengthened accumulation inside the brain by contrast with free drug solution. Kaur et al develop the donepezil nano emulsion by labrasol, cetyl pyridinium chloride, and glycerol(Kaur, Nigam, Bhatnagar, et al., 2020). The pharmacokinetic studies of the technetium pertechnetate (99mTc) labeled formulations when administered intranasally illustrated better retention of drug in the brain than the free drug solution and formulation administered orally and intravenously in Sprague Dawley rats. Moreover, the gamma scintigraphy images obtained were also in agreement with the biodistribution findings and showed maximum uptake in the brain via intranasal route of administration. The donepezil laden liposomal nanoparticles were manufactured by loading donepezil into the DSPC based liposome(Al Asmari et al., 2016). The study results demonstrated that the donepezil loaded liposome entailed consistent stability in morphology. The drug loaded liposomes indicated as high as 84.9% encapsulation efficiency with the profile of sustained release. After intranasal uptake of the donepezil liposomal formulation, the drug concentration in the plasma and brain was significantly bolstered. Harthi et al (2019) recently studied liposomal formulation of donepezil dispersing into thiolated chitosan hydrogel (TCH) by using phospholipid DPPC(Al Harthi et al., 2019). Via intranasal administration of the optimized hydrogel nanoparticles into rabbit, the area under the curve and mean peak concentration of drug in blood were enhanced by 39% and 46% in comparison with the oral tablets of donepezil, respectively. Furthermore, the drug accumulation in the brain was boosted by 107% through intranasal administration of donepezil in liposomal hydrogel. These data corroborated that intranasal administration of liposomal donepezil in TCH was a potential platform and paved a paradigm in the therapy of AD.

Ismail et al (2013) studied rivastigmine liposomes (RLs) in the AlCl3 induced AD rats, the efficacies revealed that the genes expression of the BACE1, AChE and IL1B were normalised, the memory and metabolic disturbances were significantly ameliorated after the treatment by RLs(Ismail et al., 2013). Arumugam et al (2008) delivered rivastigmine into the brain by developing liposomal rivastigmine through the intranasal administration(Arumugam et al., 2008). In stark contrast to free drug, an exceptional longer retention and higher concentration of drug inside the brain were achieved by the liposome. By coating the liposome with cell penetrating peptide (CPP), rivastigmine laden liposomes significantly strengthened the pharmacodynamics and BBB penetration via the nasal olfactory pathway after intranasal administration(Yang et al., 2013). Further studies results revealed that the gastrointestinal side-effects and first pass effect of hepar were synchronously mitigated. Similar liposomal rivastigmine were exploited and investigated in the therapy of AD(Değim et al., 2010; Mutlu et al., 2011; Salimi et al., 2021). By utilizing the poly(n-butylcyanoacrylate) nanoparticles, Wilson et al (2008) delivered rivastigmine into the brain with targeting(Wilson et al., 2008a). In contrast with the free drug, polysorbate 80 coated nanoparticles significantly increased the drug concentration by 3.82-fold inside the brain. In addition, polymeric, chitosan and solid lipid nanoparticles of rivastigmine nano were studied in mice or rats(Fazil et al., 2012; Joshi et al., 2010; Shah et al., 2015). Apart from this, other nano formulations of AChE inhibitors, including Huperzine A(Gao et al., 2006; Gao et al., 2007; Meng et al., 2018; Patel et al., 2013) and Galantamine(Hanafy et al., 2016; Misra et al., 2016; Mufamadi et al., 2013; Wahba et al., 2016), were also developed in the therapeutics of AD.

The N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists, namely memantine (3,5-dimethyl-1-adamantanamine, MEM), for patients with mild to severe AD(Laserra et al., 2015). In order to further improve the efficacy and safety, memantine loaded polylactic-co-glycolic (PLGA) nanoparticles were employed to penetrate BBB through oral administration (Sanchez-Lopez et al., 2018). By compared with free drug solution, the nano formulation significantly ameliorated the memory impairment in transgenic APPswe/PS1dE9 mice. Further studies demonstrated that the β-amyloid plaques and AD associated inflammation inside the cerebrum were remarkably reduced after the treatment. Memantine laden nanoemulsion was developed for the therapy of AD through intranasal administration(Kaur, Nigam, Srivastava, et al., 2020). The pharmacokinetic studies of the radiolabeled formulation administered intranasally in rats showed higher uptake of drug inside the brain region by compared with oral and intravenous administered rats. The study results suggested that the developed nanoemulsion loaded with memantine could be used for intranasal administration to enhance its efficacy for Alzheimer disease.

2.2. Natural compounds

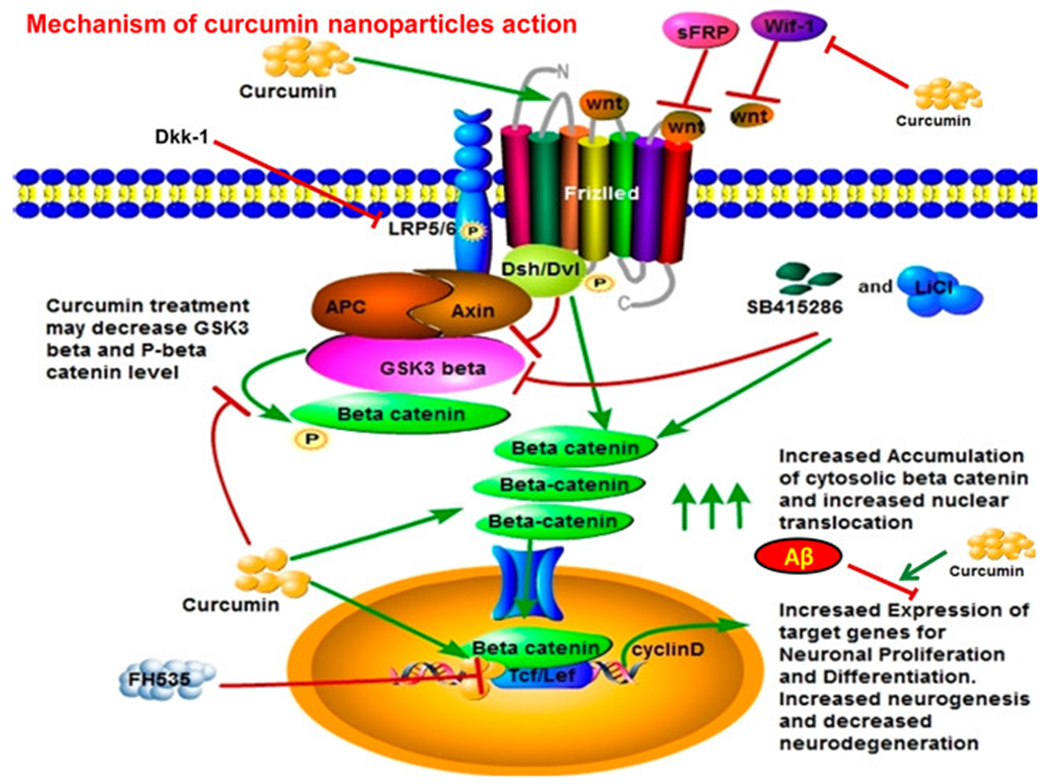

Over the past decades, more than 100 natural products have been investigated as potential therapeutics in the therapy of AD. In order to circumvent the characteristic limitations, some of the compounds have been prepared as nano formulation for the treatment of AD. By isolating from the plant of Curcuma longa L., the natural compound curcumin has demonstrated its ability to inhibit the Aβ production in vivo studies(Baum & Ng, 2004). In addition, Curcumin inhibited the Aβ aggregation, disaggregated Aβ aggregates and indicated anti-inflammatory and antioxidation activities in vivo (Lenhart et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2013). Sood et al (2013) developed curcumin and donepezil laden nanoparticle for delivery to brain by intranasal route(Chojnacki et al., 2014; Sood et al., 2013). Based on the hypothesis of cholinergic replacement and anti-amyloid, this combination treatment indicated significant brain targeting and better efficacy in AD through intranasal administration. In comparison with the intravenous injection, remarkably higher level of drug was detected inside the brain with slower clearance. Furthermore, the memory and learning abilities as well as concentration of acetylcholine inside the brain were significantly ameliorated after the combination therapy of nano formulation in rats. Quite a few curcumin loaded solid lipid nanoparticles were developed in the therapy of AD. Among them, Longvida® is an innovative solid lipid nanoparticle of curcumin, which possesses increased bioavailability and health-facilitating effects(Nahar et al., 2015). The efficacy studies in aged human tau transgenic mice demonstrated that Longvida® selectively inhibits soluble Tau dimers and ameliorates memory deficits and synaptic(Ma et al., 2013). This data provides rationale for this bioavailable curcumin formulation approved for clinical use to be a paradigm in the therapy of tauopathies, including AD(Gota et al., 2010). Maiti et al (2016) elucidated that curcumin and Longvida® possessed the ability to label and image the Aβ plaques in or ex vivo as Aβ-specific antibody, which presented a facile and low-cost approach for the measurement of Aβ-plaque deposits in post-mortem cerebrum tissue from murine models of AD(Maiti et al., 2016). It is worth noting that, Longvida® has good absorption in healthy 40-60 years old person at the dose 80 mg/day of curcumin in the early clinical trials(DiSilvestro et al., 2012). Further data analysis confirmed that this solid lipid nano formulation of curcumin indicated a series of potentially health facilitating effects in healthy middle-aged person. This included decreasing the level of Aβ, triglyceride and alanine amino transferase in plasma, increasing the activities of myeloperoxidase, salivary amylase and plasma myeloperoxidase. Moreover, further study of the efficacies of Longvida® for mood and cognition in the healthy older person (60-85 years old) suggested promising effects(Cox et al., 2015). In comparison with the placebo, Longvida® demonstrated substantially ameliorated behaviours in working memory test and sustained attention task after one hour administration. In addition, after long-term treatment, the clinical manifestations in mood and working memory were remarkably reenforced, which including the fatigue, alertness and contentedness under normal calmness or triggered by psychological stress. Further study demonstrated that Longvida® considerably decreased the level of total and LDL cholesterol while maintaining the hematological safety profiles(Cox et al., 2015). Presently, Longvida® is under clinical trial in the therapy of AD. By activating the pathway of Wnt/β-catenin, the curcumin nanoparticles strengthened neuronal differentiation in the mechanism of neurogenesis, which boosted nuclear translocation of β-catenin, suppressed the concentration of GSK-3β, and strengthened promotion activity of the TCF/LEF and cyclin-D1 (Figure 3)(Tiwari et al., 2014).

Figure 3.

The mechanism of curcumin encapsulated PLGA nanoparticles (Cur-PLGA-NPs) inducing NSC proliferation and neuronal differentiation. Reproduced with permission from(Tiwari et al., 2014).

Additionally, low density lipoproteins (LDLs) mimic nanocarriers, micelles, liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles, and Se-nanosphere formulations of curcumin that were also developed in the treatment of AD murine model (Table 1).

Resveratrol, a natural product with a stilbene structure, has been extensively investigated for its far-ranging of bioactive effects. Recent evidence has suggested that resveratrol functions as an anti-AD drug through inhibiting the aggregation of Aβ via eliminating oxidants as well as exhibiting anti-inflammatory activities(Frozza et al., 2010). Frozza et al (2013) developed lipid-core nanocapsules of resveratrol for therapy in Aβ induced AD rats(Frozza et al., 2013). By comparison with the free resveratrol, the study results indicated that the resveratrol loaded nanoparticles possessed significant ability to mitigate the deleterious effects of Aβ. The author suggested that these efficacies could be attributed to the considerable accumulation of resveratrol level inside the cerebrum tissue entailed with the lipid-core nanocapsules. Other system of nanoparticles for resveratrol, including mesoporous nano-selenium (MSe) were studied in transgenic APP/PS1 AD mice(Sun et al., 2019).

In addition, other natural products, such as piperine(Elnaggar et al., 2015; Yusuf et al., 2013), quercetin(Dhawan et al., 2011; Moreno et al., 2017; Nday et al., 2015; Rishitha & Muthuraman, 2018; Sun et al., 2016), coumarin(Zheng et al., 2017) and erythropoietin(Dara et al., 2019) were also delivered by nano formulation for the treatment of AD in the murine model where detailed information on this is listed in table 1.

2.3. Other active ingredients

Over the past decade, a multitude of new approaches and strategies were studied in the therapy of AD. Despite the enormous problems caused by non-specific targeting and immunogenicity, siRNA have been extensively utilized to hinder Aβ aggregation in vivo(Gregori et al., 2015). Thus, effective delivery platform has been developed and certain NPs were exploited for the capability of deliver siRNA to targeting tissues or cell lines. By loading siRNA of BACE1 into exosomes which produced by self-derived dendritic cells(Alvarez-Erviti et al., 2011), the specific gene knockdown in the targeting neurons, microglia, oligodendrocytes of the brain were specifically achieved through intravenous injection of the neuron-specific RVG-targeted exosomes, which indicated the knockdown of BACE1 by 60% of mRNA and 62% of protein levels. By using a controllable technology, Shen et al (2021) constructed CRISPR/Cas9 plasmids (CF-TBIO) loaded nano-biohybrid complexes to knock out the gene of BACE1 and decrease the deposits of amyloid-β in vivo(Shen et al., 2021). By prolonging the dosing interval, the nano formulation significantly improved the cognitive abilities, mitigated the pathological disorder in transgenic AD mice. These results illustrated that CF-TBIO was a potent CRISPR-chem drug-delivery paradigm and possessed great potential for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. A great deal of neurotrophic proteins and neuropeptides have demonstrated their crucial neurotrophic function during neurodevelopment and post nerve damage, which showed a potential target in the therapy of AD(Bassan et al., 1999). However, the complex nature of peptides posed a significant challenge as they are too labile, degrade facilely under the enzymes, unable to cross the BBB, and indicate a rapid circulation half-life in vivo. In order to address these problems and enhance the accumulation of neuroprotective peptide inside the brain, Liu et al (2013) developed a B6 peptide coated PEG-PLA nanoparticles (NP) in the therapy of AD(Liu et al., 2013). Through the lipid raft-mediated and clathrin-mediated endocytosis, B6-modified NP (B6-NP) indicated superior penetration into the capillary endothelial cells of the brain. The efficacy study in AD mouse models delineated that the learning ability, disruption of cholinergic and hippocampal neurons loss was significantly ameliorated after treatment by the B6-NP loaded neuroprotective peptide-NAPVSIPQ. Apart from these, other active ingredients, including zinc, nerve growth factor (NGF) and chondroitin sulphate have been developed as nanotechnology-empowered therapeutics in AD.

3. NANOTECHNOLOGY-ENABLED THERAPEUTICS IN PD

PD ranks as the second most prevalent chronic neurodegenerative disease worldwide(Teixeira et al., 2018), which is an refractory and escalated neurodegenerative disease that is mostly innate origin with 1-2% of population among the age 65 or older affected(Kulkarni et al., 2015). PD is distinguished by the apoptosis of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra of brain, a crucial tissue which regulates motor effects by generating dopaminergic axons into the striatum(De Jesús-Cortés et al., 2012). During early stages, the clinical manifestations of PD are primarily seen as motor related which include hypokinesia, rigidity, shaking, tremor as well as difficulty walking. More advanced stages of PD are related with cognitive and behavioural disorders, such as dementia. Several cellular pathways are proposed to be associated with neuronal apoptosis in PD, including the stress in endoplasmic reticulum as well as dysfunction in proteasome and mitochondria(Athauda & Foltynie, 2015).

In order to improve the patient’s quality of life, management of approaches such as the criteria for diagnosing and evaluation the stage of the disease have been initiated, followed by the exploiting and utilization of personalized approaches. Presently, the symptomatic treatment approved by FDA mainly relied on the use of pharmacological approaches, including L-DOPA, which served as the standard therapy, dopamine agonists (such as ropinirole and pramipexole), monoamine oxidase type B (MAO-B, including safinamide, selegiline and rasagiline), and catechol-Omethyltransferase (including entacapone and tolcapone) inhibitors, to make up for the deficiencies of dopamine in the system of nigrostriatal dopamine. However, these therapeutics possess quite a few side-effects, which prevents long-term use of such therapeutics(Onofrj et al., 2008). Therefore, based on these several unmet needs, urgent solutions are required to improve therapy for patients with PD(LeWitt & Chaudhuri, 2020). Nevertheless, satisfactory therapeutics to ameliorate the syndromes and/or slowed progress of PD by rescuing dopaminergic neurons from premature apoptosis is still in deficiency(Teixeira et al., 2018). Nanotechnology-empowered treatment is a budding therapy strategy in PD due to the targeting delivery, boosted efficacy in treatment, and bioavailability of neurotherapeutics with minimal side effects(Gomes et al., 2014). A description of these studies’ information is presented below in table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of nanotechnology-empowered therapeutics in PD

| Drug | Type of NPs | NPs material | BBB penetration targeting | Application model | Route of administration | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rasagiline | Chitosan | Chitosan glutamate, TPP | NA | Swiss albino mice | Intranasal | (Mittal et al., 2016) |

| Ropinirole | Chitosan | Chitosan glutamate, TPP | NA | Rats | Intranasal | (Jafarieh et al., 2015) |

| Solid lipid | Dynasan 114, stearylamine | Pluronic F-68, soy lecithin | Albino mice | Intranasal | (Pardeshi, Rajput, et al., 2013) | |

| Polymer-lipid hybrid | HPMC K15M, dynasan 114, stearylamine | Pluronic F-68, soy lecithin | Albino mice | Intranasal | (Pardeshi, Belgamwar, et al., 2013) | |

| Nanoemulsion | Sefsol 218, tween 80, Transcutol | NA | Rats | Intranasal | (Mustafa et al., 2012) | |

| Levodopa | Chitosan | Chitosan, tri-polyphosphate | NA | Rats | Intranasal | (Sharma et al., 2014) |

| Polymer | PLGA | NA | 6-OHDA induced PD rats | Intranasal | (Gambaryan et al., 2014) | |

| Poly(L-DOPA) | NA | MPTP induced PD mice | Intraperitoneal | (Vong et al., 2020) | ||

| Bromocriptine | Chitosan | Chitosan glutamate, TPP | NA | Swiss albino mice | Intranasal | (Md et al., 2013) |

| Chitosan glutamate, TPP | NA | Swiss albino mice | Intranasal | (Md, Haque, et al., 2014) | ||

| Urocortin peptide | Polymer | Odorranalectin-PEG-PLGA | NA | 6-OHDA induced PD rats | Intranasal | (Wen et al., 2011) |

| Neuropeptide substance P | Gelatin | Gelatin | NA | 6-OHDA induced PD rats | Intranasal | (Zhao et al., 2016) |

| Fibroblast growth factor | Gelatin | GNLs, copolymer-poloxamer 188 | NA | 6-OHDA induced PD rats | Intranasal | (Zhao et al., 2014) |

| GDNF | Polymer | PLGA | NA | MPTP induced PD monkey | Intracerebroventricular | (Garbayo et al., 2016) |

| hGDNF | Polymer | DGL-PEG-angiopep (DPA) | Angiopep | Rotenone Induced PD rats | Intravenous | (Huang et al., 2013) |

| Lipid | TAT-Conjugated Lipid, Precirol ATO ®5, Mygliol ® | Poloxamer 188 | MPTP induced PD mice | Intranasal | (Hernando et al., 2018) | |

| GDNF and VEGF | Polymer | PLGA | NA | 6-OHDA induced PD rats | Intracerebroventricular | (Herran et al., 2013) |

| GDNF, VEGF | Polymer | PLGA | NA | 6-OHDA induced PD rats | Intracerebroventricular | (Herran et al., 2014) |

| MicroRNA-124 | Polymer | PLGA | NA | 6-OHDA induced PD mice | Intracerebroventricular | (Saraiva et al., 2016) |

| Alpha-Synuclein RNAi | Iron oxide | Nano Fe3O4 | Oleic acid | MPTP induced PD mice | Intraperitoneal | (Niu et al., 2017) |

| RNAi, mRNA, NGF | Nano-MgO Micelle | Sodium laurate, nano-MgO | NA | MPTP induced PD mice | Intraperitoneal | (Li et al., 2021) |

| Plasmid DNA (pDNA) | Chitosan | Chitosan | NA | MPTP induced PD mice | Intraperitoneal | (Hu et al., 2018) |

| Retinoic acid | Polymer | Polymeric (PEI-DS) | NA | MPTP induced PD mice | Intracerebroventricular | (Esteves et al., 2015; Maia et al., 2011) |

| Curcumin | Liposome | DGP, Curcumin-DGP | NA | (DJ-1)-knockout PD rats | Intravenous | (Chiu et al., 2013) |

| Curcumin and Piperine | Lipid | GMO | Pluronic F-68 | Rotenone Induced PD mice | Oral | (Kundu et al., 2016) |

| MSCs and Curcumin | Exosomes | Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) exosomes | NA | MPTP induced PD mice | Intranasal | (Peng et al., 2022) |

| Resveratrol | Polymer | PLA polysorbate | Polysorbate 80 | MPTP induced PD mice | Intraperitoneal | (da Rocha Lindner et al., 2015) |

| Liposome | Lecithin and cholesterol | NA | 6-OHDA induced PD rats | Oral | (Wang et al., 2011) | |

| Nicotine | Polymer | PLGA | NA | MPTP induced PD mice | Intraperitoneal | (Tiwari et al., 2013) |

| Schisantherin A | Nanocrystal | Schisantherin A, F68 | NA | MPTP induced PD zebrafish | Oral | (Chen et al., 2016) |

| Non-Fe Hemin-Cl | Polymer | PMPC | HIV-1 trans-activating transcriptor (TAT) | MPTP induced PD mice | Intravenous | (Wang et al., 2017) |

| Cerium oxide | Cerium oxide | Cerium oxide | NA | NA | NA | (Kaushik et al., 2018) |

| Iron (II, III) oxide | Superparamagnetic iron oxide | Nano Fe3O4 | NA | 6-OHDA induced PD rats | Intracerebroventricular | (Umarao et al., 2016) |

| Graphene quantum dots | Graphene quantum dots | Carbon fibres | NA | PFFs induced PD mice | Intraperitoneal | (Kim et al., 2018) |

3.1. MAO-B inhibitor and dopamine receptor agonist

As an irreversible and selective MAO-B inhibitors, rasagiline was classified as the second-generation inhibitor and indicated the activity of dopamine receptor agonist(Weinreb et al., 2010; Youdim et al., 2005). Owing to the first pass effect of hepar, rasagiline possesses extremely fast blood circulation half-life of 0.6-2 h and has only 36% of oral bioavailability. The oral route of this drug has gastrointestinal adverse effects including vomiting, nausea, dizziness, and headache, which led to implacableness in the patient. To circumvent these limitations, Mittal et al (2016) prepared and evaluated rasagiline laden chitosan glutamate nanoparticles (RAS-CG-NPs) through the utilizing of ionic gelation of CG (Mittal et al., 2016). By comparison with both intranasal administration of free drug and intravenous injection of nanoparticles, the intranasal administration of the RAS-CG-NPs significantly increased the drug accumulation inside the brain at all indicated time points. These results indicated remarkable improvement of bioavailability inside brain after uptake of the rasagiline-laden CG-NPs, which represented an innovative therapeutic paradigm for the treatment of PD by direct targeting nose to brain.

As a non-ergot D2/D3 dopamine agonist, ropinirole indicated greatest affinity at the receptors of D3 and been prescribed to treat PD patients with mild or severe symptoms. Oral ropinirole therapy is associated with nausea, vomiting, and gastrointestinal disturbances which lead to incompliance among patients with frequent dosing schedules(Kaye & Nicholls, 2000). Jafarieh et al (2015) investigated ropinirole hydrochloride (RH)-laden chitosan nanoparticles (CSNPs), 0.5 h after intranasal administration of the free drug or nanoparticles, the drug concentration ratio for brain/blood were 0.251 and 0.386, respectively(Jafarieh et al., 2015). By comparison with other delivery methods, this kind of innovative formulation exhibited advantage of nose to brain delivery of ropinirole through the utilizing of mucoadhesive nanotechnology. Solid lipid NPs (SLNs)(Pardeshi, Rajput, et al., 2013), polymer-lipid hybrid nanoparticles(Pardeshi, Belgamwar, et al., 2013) as well as nanoemulsion(Mustafa et al., 2012) were also used for the delivery of ropinirole (Table 2). As a long-established gold standard drug for the treatment of PD, L-3,4-Dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA) is ultimately bound to treat each patient. Nevertheless, L-DOPA possesses certain disadvantages, which include gradual decrease in the therapeutic effect during repeated use and requires increased dosages of drug to achieve the precise effect. Considering these drawbacks, Gambaryan et al (2014) studied L-DOPA loaded PLGA nanoparticles delivery platform in 6-OHDA-induced PD rats(Gambaryan et al., 2014). With L-DOPA nanoparticles, motor function recovery continued with unabating effect for one week after drug discontinuance, whereas free standard drugs demonstrated notable efficacy following only the first time of therapy. Pharmacokinetics study unravelled that L-DOPA nanoparticles possessed prolonged blood circulation, improved bioavailability, boosted efficacy and significant drug accumulation inside the brain through intranasal administration. Additionally, chitosan nanoparticles(Sharma et al., 2014) and poly(L-DOPA) (Vong et al., 2020) were exploited for the delivery of L-DOPA (Table 2). The natural product bromocriptine (BRC) which derived from ergot and indicated the activity of dopamine receptor agonist, has been extensively utilized in clinic to mitigate and ameliorate the deleterious motor disturbances involved in chronic levodopa therapy in PD. Md et al (2013) investigated and optimized chitosan based nano formulation of bromocriptine though direct nose-to-brain route(Md, Haque, et al., 2014; Md et al., 2013). BRC laden chitosan NPs exhibited higher drug residence inside the nostrils for up to 4 h, which bypassed the BBB and presented profound brain/blood ratios in drug concentration, whereas only about 1 h was retained by the free BRC solution. This nanoparticulate drug delivery platform represented as a potent nose-to-brain drug delivery paradigm in the therapy of PD(Md, Haque, et al., 2014).

3.2. Other compounds

Currently, a broad range of nanoplatform have been developed for the delivery of active compounds for the therapy of PD. Wen et al (2011) prepared odorranalectin-conjugated nanoparticles by loading urocortin peptide (UCN) and investigated its therapeutic efficacy on hemiparkinsonian rats(Wen et al., 2011). The resulting nanoparticles effectively fortified the cerebrum accumulation of DiR loaded nanoparticles and boosted the neuroprotective effects of urocortin (UCN) peptide on hemiparkinsonian rats following intranasal delivery. This system demonstrated that the odorranalectin-conjugated nanoparticles could be utilized as a potential platform for drug delivery via nose-to-brain pathway, particularly for macromolecular therapeutics, in the therapy of CNS disease. Other peptides, such as the neuropeptide substance P(Zhao et al., 2016), fibroblast growth factor(Zhao et al., 2014), glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF)(Garbayo et al., 2016), hGDNF(Hernando et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2013) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)(Herran et al., 2014; Herran et al., 2013) laden nanoparticles were developed for the therapy of PD in murine model.

Gene treatment has received tremendous focus in the therapy of CNS disorders. Saraiva et al (2016) used biocompatible and traceable polymeric nanoparticles to load a neuronal fate determinant microRNA-124 (MiR-124)(Saraiva et al., 2016), which prompt the neurogenesis in subventricular zone and neurons repairment in PD. The in vivo results revealed that MiR-124 nanoparticles were also capable of eliciting the neurons migrated into the lesioned striatum of 6-OHDA induced PD mice. Furthermore, miR-124 nanoparticles revealed to improve motor performance in 6-OHDA mice at the apomorphine-induced rotation task. Additionally, alpha-synuclein RNAi(Niu et al., 2017), α-synuclein (α-syn)-targeted mRNA(Li et al., 2021) and plasmid DNA (pDNA)(Hu et al., 2018) were also delivered by nanoparticles in the treatment of PD.

Natural products have been also proposed as potent drugs for the treatment of PD. Esteves et al (2015) developed retinoic acid nano formulation by using polymeric nanoparticles(Esteves et al., 2015). The results elucidated that the retinoic acid nanoparticles remarkably mitigated the loss of dopaminergic neuron at the region of substantia nigra and ameliorated innervations of neuronal fiber/axonal at the region striatum. Moreover, an up regulation of transcription factors Pitx3 and Nurr1 was elicited by RA-NPs, which suggesting the facilitating effect on the formation and protection of dopaminergic neurons in PD. In addition, Maia et al (2011) elucidated the effects of retinoic acid laden polyelectrolyte nanoparticles to elicit neurogenesis exclusively after being delivered into subependymal ventricular zone stem cells(Maia et al., 2011). Retinoic acid laden nano formulation significantly bolstered the population of functional neurons with neuronal nuclear protein (NeuN), which possessed the function of responding to depolarization and expressed the NMDA receptor. This neoformation presented an innovative paradigm at delivering of pro-neurogenic factors in vivo and PD therapy.

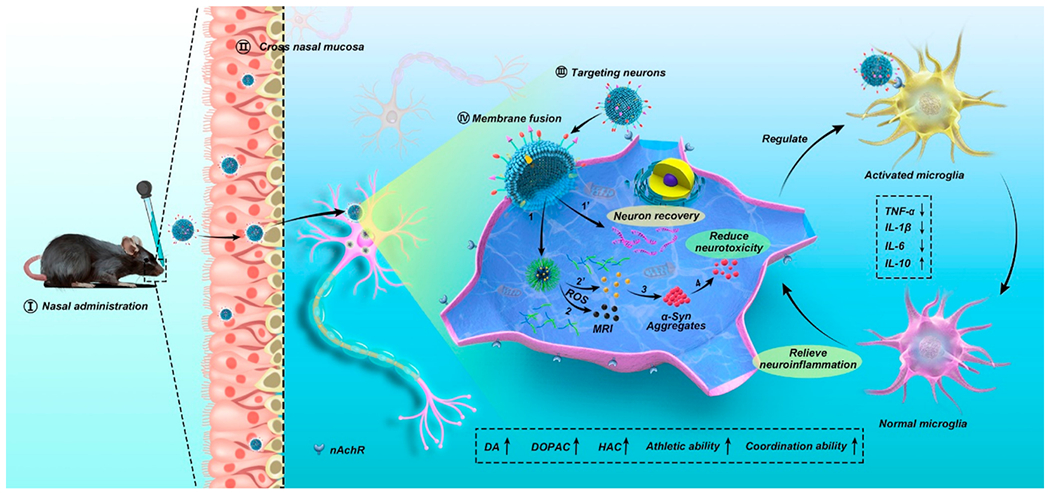

Peng et al (2022) developed a self-oriented nanoparticles named PR-EXO/PP@Cur by combining curcumin with medical MSC-derived exosomes (Figure 4)(Peng et al., 2022). After intranasal administration of the nanoparticles, the study’s results elucidated that the exosomes were able to effectively release curcumin into the cytoplasm of neurons through self-oriented permeating the multiple membrane barriers. Furthermore, by decreasing the aggregates of α-synuclein aggregates, facilitating neuron function recovery, and mitigating the neuroinflammation, these novel nanoparticles were able to attain three dimensional synergistic therapy to manage the involute pathologies of PD. Additionally, Curcumin(Chiu et al., 2013; Kundu et al., 2016; Peng et al., 2022), piperine(Kundu et al., 2016), resveratrol(da Rocha Lindner et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2011), nicotine(Tiwari et al., 2013), schisantherin A(Chen et al., 2016) as well as non-Fe Hemin-Cl(Wang et al., 2017) were also delivered by nanoparticles in the treatment for PD.

Figure 4.

Schematic illustration of delivery and potential therapeutic mechanism of PR-EXO/PP@Cur nanocarriers. Reproduced with permission from(Peng et al., 2022).

Apart from the above-mentioned active component, some inorganic ingredients were developed as nano formulation in PD treatment, the detail information was listed in table 2.

4. NANOTECHNOLOGY-EMPOWERED THERAPEUTICS IN HD

Huntington’s disease (HD) is a rare genetic disease related to enlarged trinucleotide CAG repeats and fatal monogenic mutation at the gene of chromosome 4 which encoding the huntingtin protein(Valadao et al., 2022). This causes the production of a mutant huntingtin (mHTT) protein with an aberrantly growing polyglutamine repeat, leading to neuronal disorder and apoptosis. The general prevalence of HD was about 10-14 individuals per hundred thousand populations, which has indicated frequent occurrence during middle age with an average survival time of 15 to 20 years(McColgan & Tabrizi, 2018). Several studies revealed that HD relating to a multitude of pathways, which including the production of toxic mutant protein, dysfunction of mitochondria, disturbance of proteostasis(McColgan & Tabrizi, 2018).

Over the past two decades, more than 100 clinical investigations have been executed for HD by studying diverse therapeutics. Nevertheless, no more than 3.5% of the investigations passing to the following clinical trials with extraordinary low success rate(Travessa et al., 2017). present investigations involved therapeutic strategies performed by nanotechnology mainly focus on inhibition or deactivation of the HTT protein, silencing of the HTT gene, antioxidation. The budding treatments concentrated on decreasing concentration of mHTT by silencing the mHTT gene via either the DNA or RNA, which perhaps were the leading potent methods as for disease modification(McColgan & Tabrizi, 2018). Through the nose-to-brain route, anti-HTT small interfering RNA (siRNA) laden chitosan-based nanoparticle (NP) were designed by Sava et al(Sava et al., 2020). The study results proved that this NP significantly decreased the expression of HTT mRNA by 50% in the transgenic HD mice, which protected the siRNA from decomposition “en route” to the brain. The results deciphered that intranasal delivery of nano formulation loading siRNA was a potent treatment option for decreasing mutant HTT expression with high efficacy and safety. Through co-incubating hydrophobically-modified siRNAs (hsiRNAs) with exosomes, Didiot et al (2016) developed hsiRNA-loaded exosomes with consistent distribution and integrity of vesicle size(Didiot et al., 2016). After intracerebroventricular injection of the hsiRNA-loaded exosomes into the mouse model, the expression of Huntingtin mRNA in the bilateral cerebrum was significantly decreased by 35% and bilateral oligonucleotide distribution was evoked. The effects of the “natural” oligonucleotide delivery approach to facilitate the distribution and boost the function of oligonucleotides provides a crucial paradigm for development of innovative treatment for HD and neurodegenerative diseases.

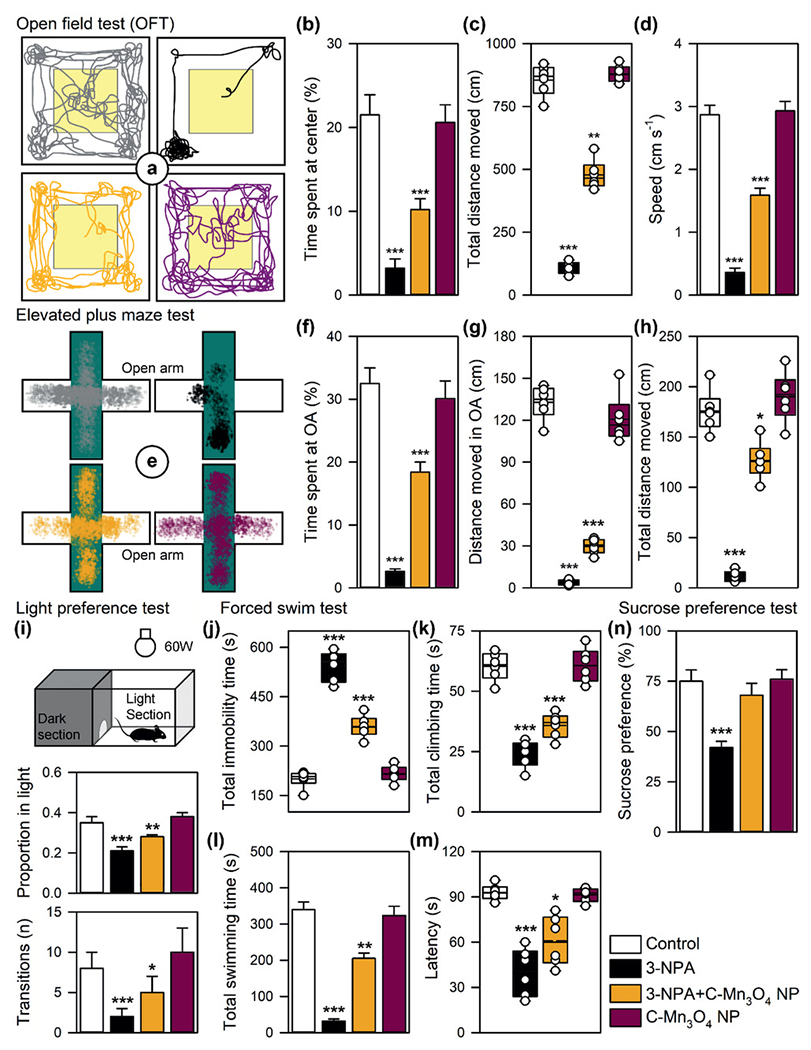

Post-mortem HD patient studies have revealed that the level of selenium was considerably decreased in the brain, which is an indispensable element that plays a vital role in anti-cytotoxicity and redox. By mimicking the enzyme glutathione peroxidase (GPx), the biocompatible C-Mn3O4 and selenium nanoparticles was developed for the treatment of HD disease through controlling HD-related neurodegeneration(Adhikari et al., 2021; Cong et al., 2019). The citrate functionalized C-Mn3O4 NP indicated significant GPx-like activity under the physiological conditions and successfully internalized into cellular dioxide scavenging system(Adhikari et al., 2021). Further therapeutic efficacy in the HD mouse was confirmed this functionalized C-Mn3O4 NP (Figure 5), which presents a novel and effective strategy by using enzyme-based nanoparticles.

Figure 5.

Effect of C-Mn3O4 NPs for anxiety and depression-like behavior test. OFT. a) Representative tracks inside the open field. b) Time spent at the center. c) Total distance moved. d) Average speed. EPM test. e) Trace of movement in EPM. f) Time spent in open arm. g) Distance moved in open arm. h) Total distance moved. i) Light preference test. Time spent in light zone and transitions into light zone. FST. j) Total immobility time, k) total climbing time, l) total swimming time, and m) latency to first immobility event. n) SPT. Data are expressed as Mean ± SD. N = 6. Statistical significance versus control group (***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05). Reproduced with permission from(Adhikari et al., 2021).

Rosmarinic acid indicated to possess remarkable ability of attenuating H2O2-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and cell apoptosis(Lee et al., 2008). By utilizing solid lipid nanoparticles to load rosmarinic acid, Bhatt et al (2015) successfully developed a drug delivery platform which substantially boost the drug accumulation in brain through intranasal route(Bhatt et al., 2015). The results demonstrated that the nano formulation treatment significantly ameliorated behavioural performance and mitigated the oxidative stress in a rats model induced by in 3-nitropropionic acid, which presented as a potent therapeutic option for the effective treatment of HD. Additionally, thymoquinone(Ramachandran & Thangarajan, 2018), epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG)(Cano et al., 2021), cholesterol(Birolini et al., 2021; Valenza et al., 2015) and ivabradine(Saad et al., 2021) were developed as nanoparticles for the treatment of HD (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of nanotechnology-empowered therapeutics in HD

| Drug | Type of NPs | NPs material | BBB penetration targeting | Application model | Route of administration | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-HTT siRNA | Chitosan | Chitosan | NA | Transgenic YAC128 HD mice | Intranasal | (Sava et al., 2020) |

| hsiRNAHTT | Exosome | U87 glioblastoma cells exosome | NA | Rats | Intrastriatal bolus | (Didiot et al., 2016) |

| GPx-like Activity | Biocompatible nanoscale | C-Mn3O4 | NA | 3-NPA induced HD mice | Intraperitoneal | (Adhikari et al., 2021) |

| Selenium nanoparticles | Selenium | Nano selenium | NA | Transgenic HD models of Caenorhabditis elegans | NA | (Cong et al., 2019) |

| Rosmarinic acid | Solid lipid | Glycerol monostearate (GMS), HSPC, Tween 80, soya Lecithin | NA | 3-NPA induced HD rats | Intranasal | (Bhatt et al., 2015) |

| Thymoquinone | Solid lipid | Stearic acid, lecithin, taurocholate | NA | 3-NPA induced HD rats | Intraperitoneal | (Ramachandran & Thangarajan, 2018) |

| Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) | Polymer | PEG-PLGA | NA | 3-NPA induced HD mice | Intraperitoneal | (Cano et al., 2021) |

| Colesterol | Polymer | PLGA | Heptapeptide (g7) | Transgenic R6/2 HD mice | Intraperitoneal | (Birolini et al., 2021) |

| Colesterol fluorescente (NBDchol) | Polymer | PLGA conjugated rhodamine | Glycopeptides (g7) | Transgenic R6/2 HD mice | Intraperitoneal | (Valenza et al., 2015) |

| Ivabradine | Phospholipids | Phospholipon 90H | NA | 3-nitropropionic acid (3-NPA) induced HD mice | Intravenous | (Saad et al., 2021) |

5. NANOTECHNOLOGY-CAPACITATED THERAPEUTICS IN ALS

ALS, also alias Lou Gehrig’s disease or motor neuron disease (MND), is an exceedingly uncommon and quickly progressive disease that is usually characterized by mid age onset and is associated with degeneration of spinal cord motor neurons(Tesla et al., 2012). This neurodegenerative disease results in weakness and atrophy of muscles inside the whole body, and patients finally forfeit all spontaneous movement with morbidity around 1-3 people per 100,000 worldwide(Oskarsson et al., 2018). Despite no complete explicit pathogenesis is deciphered, the dysfunction of RNA processing and protein disturbance can be responsible. Clinical study indicates that nearly 40% of ALS patients with a family history possessed the repeat magnifications of chromosome 9 open reading frame 72 gene (C9orf72), which responsible for the cause of ALS(Oskarsson et al., 2018).

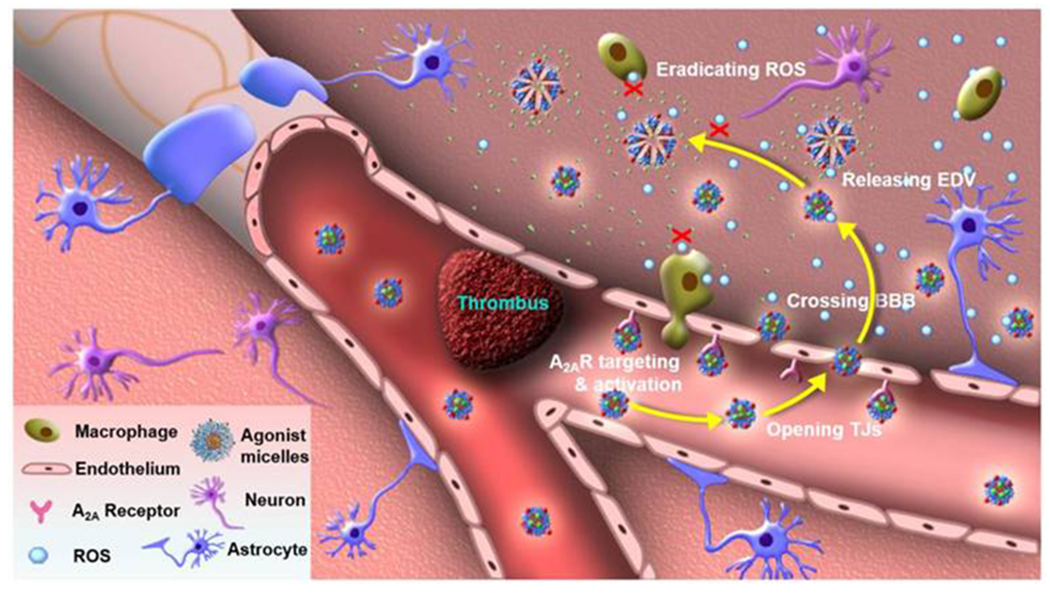

So far, there are no effective therapeutics for ALS, the reported median survival expectancy of ALS patients ranged from 24 to 48 months after diagnosis(Oskarsson et al., 2018). Presently, only two therapeutics, namely riluzole and edaravone, have been authorized by the US FDA for the therapy of ALS. Bondì et al (2010) prepared brain-targeted solid lipid nanoparticles as drug carriers for riluzole to a reach therapeutic drug concentration inside the cerebrum(Bondi et al., 2010). The results revealed that the riluzole laden nanoparticles significantly enhanced the drug accumulation inside the brain with a rational indiscriminate biodistribution in other tissues. By suppressing P-glycoprotein inside brain endothelial, the cocktail liposomes loaded with riluzole and verapamil were developed to overcome drug resistance(Yang et al., 2018). Through enhancing the BBB penetration (Figure 6), Jin et al (2017) exploited edaravone encapsulated agonistic micelles to protect the ischemic tissue inside the brain(Jin et al., 2017). By comparison with the free edaravone, the results indicated that agonistic micelles remarkably enhanced the drug accumulation inside brain ischemia post intravenous injection in mice, which represented as a promising paradigm for enhancing the therapeutic efficacy in the treatment of ALS. Other nano formulation, such as minocycline(Wiley et al., 2012) and cerium oxide(DeCoteau et al., 2016), were exploited in the therapy of ALS (Table 4).

Figure 6.

Edaravone agonistic micelles specifically activated A2AR over-expressed in the capillaries of brain ischemia, increased BBB penetration by temporarily opening para-endothelial tight junctions (TJs), entered brain ischemia by crossing the compromised TJs, released the encapsulated edaravone, and sustainably eradicated ROS excreted by brain-derived cells (microglia, astrocytes and endothelium) as well as infiltrated inflammatory cells (macrophages and neutrophils). Reproduced with permission from(Jin et al., 2017).

Table 4.

Summary of nanotechnology-empowered therapeutics in ALS

| Drug | Type of NPs | NPs material | BBB penetration targeting | Application model | Route of administration | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Riluzole | Solid lipid | Compritol 888 ATO, epikuron 200 | NA | Rats | Intraperitoneal | (Bondi et al., 2010) |

| Verapamil, riluzole | Cocktail liposome | DSPC, cholesterol, DSPE-PEG2000, | NA | Brain endothelial bEND.3 cells | NA | (Yang et al., 2018) |

| Edaravone | Micelles | PEG-PLA, | NA | Mice | Intravenous | (Jin et al., 2017) |

| Minocycline | Liposome | DPPC, cholesterol, DSPE-PEG2000, | LPS | SOD1 mice | Intracerebroventricular by Osmotic Pump | (Wiley et al., 2012) |

| Cerium oxide | Cerium oxide | Cerium oxide | NA | SOD1 mice | Intravenous | (DeCoteau et al., 2016) |

6. NANOTECHNOLOGY-EMPOWERED THERAPEUTICS IN OTHER NEURODEGENERATIVE DISEASES

Amnesia is a clinical symptom described by cognition decline, which may be induced by either brain diseases or injury. Presently, no exclusive therapeutics were approved for the treatment of this disease, but many rely on the AD drug(Ngowi et al., 2021). This includes the galantamine loaded thiolated chitosan nanoparticles(Sunena et al., 2019), NGF laden PBCA nanoparticles(Basel et al., 2005), as well as rivastigmine chitosan nanoparticles(Nagpal et al., 2013) in the amnesia murine model. In short, NPs have demonstrated boosted therapeutic efficacy; nevertheless, continued investigations are needed to concentrate on the efficacies for the therapy of amnesia.

Multiple system atrophy (MSA) is a fatal and rare neurodegenerative disease, which characterized by the degeneration of autonomic nervous and system central and autonomic nervous system with no explicit reason or unknown environmental factors (Fanciulli & Wenning, 2015; Quinn, 2004). The clinical symptom of MSA were disorder in motor, accompanied by parkinsonism and pyramidal features, associated with cardiovascular autonomic or involvement urogenital(Quinn, 2004). Presently, only pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches based on symptomatic therapy are available with poor evidence level. A multidisciplinary management approach was recommended to optimally address the patients’ needs(Fanciulli & Wenning, 2015).

Multiple sclerosis is a neurodegenerative disorder inside the CNS and is known to be the most common non-traumatic debilitating disease among younger populations (Dobson & Giovannoni, 2019). Currently, more than 2.2 million people are affected by multiple sclerosis worldwide with significant increasing prevalence in many regions(Wallin et al., 2019). Presently, no effective drugs were approved for the therapy of the disease and few therapeutics are utilized to mitigate the symptoms of only early stages of the disease with low evidence levels. Recently, dimethyl fumarate loaded solid lipid nanoparticles(Ojha & Kumar, 2018) and chitosan nanoparticles(Ojha et al., 2019) were reported to significantly increase the bioavailability and neuroprotective effects in rat model. This data presented that nanotechnology was a potential strategy with an enhanced circulation for the better treatment of multiple sclerosis.

Ataxia is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by poor muscle control that causes clumsy voluntary movements. It may result in difficulty with walking and balance, hand coordination, speech and swallowing, and eye movements. Ataxia usually caused by damage to the part of the brain that controls muscle coordination (cerebellum) or its connections. Unfortunately, no therapy is currently available for treating this condition. Self-assembling VEGF nano formulation possessed potent neurotrophic and angiogenic properties(Hu et al., 2019). This nano formulation demonstrated safe and functional amelioration in treating late stages of ataxia in the transgenic SCA1 mice.

Conclusion

Owing to the aging and longevity of population worldwide, the number of patients diagnosed with chronic neurodegenerative diseases is projected to increase exponentially. Nevertheless, none of current therapeutic approaches can offer satisfactory results in the therapy of neurodegenerative diseases. Therefore, there is an immediate action to develop novel therapeutics for neurodegenerative diseases with urgent unmet medical need that can hinder the progression of disease. Although the application of nanomedicine in neurodegenerative diseases may increase the cost of drug development and lead to the complexity of drug administration. The unique properties of nanoparticles have led to advantages over conventional therapeutics by enhancing drug accumulation inside the brain by infiltration of the BBB, which may present an innovative strategy to break this impasse and provide the solution of breakthrough therapies for the therapy of neurodegenerative diseases. Nanotechnologies are at the forefront of the application of such strategies and especially the development of therapeutics to transport drug into the target site of brain. As illustrated in numerous studies, nanomedicine can take advantage of neuroscience-related mechanism as well as restorative strategies, which exhibited promising results in the development of nano-empowered therapeutics for use in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Consequently, nanotechnology can be utilized to possibly circumvent the present limited availability in neurological treatments, which includes non-specific distribution and poor efficiency rates of therapeutics. However, the development of nanotechnologies in neurodegenerative disorders is still at the initial phase of progress. Intensive investigations need to be carried out for better fathoming of the physiology and pathology of the brain in order to devise better delivery nano systems. Currently, the utilization of nanotechnology-enabled therapeutics represents a promising and mainstay strategy to further unravel the mechanistic actions of the therapies for the neurodegenerative diseases. In addition, the expanding RNAi therapeutics in neurodegenerative diseases through lipophilic-RNA conjugates or cholesterol-functionalized DNA/RNA boasts innovative benefits both in clinical efficacy and drug administration(Brown et al., 2022; Nagata et al., 2021), heralding the next generation of nanotherapeutics development. Additionally, targeting at microglia and modulating the immune microenvironment was a new alternative direction of developing nanomedicines in neurodegenerative disorders. The developing combination of alternative routes of therapeutics administration should be given great attention, particularly intranasal delivery and the BBB receptor-mediated transport through exploiting physiological processes. Meanwhile, the discovery of new potential therapeutic targets should take advantage of the superiority of nanotechnology for developing effective therapeutics, which possessed promising potential in developing compelling therapeutic effects over the long haul.

Acknowledgments

Jianqin Lu: Conceptualization; Supervision; Writing – original draft; Funding acquisition. Zhiren Wang: Conceptualization; Investigation, Writing – original draft. Karina Marie Gonzalez: Writing – review and editing. Leyla Estrella Cordova: Writing – review and editing.

Funding Information

This work was supported in part by a Startup Fund from the R. Ken Coit College of Pharmacy at The University of Arizona and a PhRMA Foundation Research Starter Grant in Drug Delivery, and by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants (R35GM147002 and R01CA272487).

Abbreviations

- 5XFAD

B6SJL-Tg(APPSwFlLon,PSEN1*M146L*L286V)6799Vas/Mmjax

- Aβ

amyloid-β

- AChE

Acetylcholinesterase

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- AMT

adsorptive-mediated transcytosis

- ALS

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- APP

amyloid precursor protein

- APP/PS1

B6.Cg-Tg(APPswe,PSEN1dE9)85Dbo/Mmjax

- BACE1

Beta-Secretase 1

- BBB

Blood brain barrier

- BRC

bromocriptine

- CPP

cell penetrating peptide

- CNS

central nervous system

- CSNPs

chitosan nanoparticles

- DSPC

1,2-distearyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- DDS

drug delivery systems

- DPPC

Dipalmitoylphosphocholine

- EPC

1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-ethylphosphocholine

- siRNA

Small interfering RNA

- B6 peptide

CGHKAKGPRK

- DMTs

disease-modifying therapies or treatments

- 6-OHDA

6-hydroxydopamine

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- GPx

glutathione peroxidase

- GDNF

glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- HD

Huntington’s disease

- hsiRNAs

hydrophobically-modified siRNAs

- RMT

receptor mediated transcytosis

- LDLs

low density lipoproteins, L-DOPA, L-3,4-Dihydroxyphenylalanine

- MTD

maximal tolerated dose

- MAO-B

monoamine oxidase type B

- mHTT

mutant huntingtin

- MND

motor neuron disease

- MSA

Multiple system atrophy

- NeuN

neuronal nuclear protein

- NFT

neurofibrillary tangles

- NGF

nerve growth factor

- S1P

sphingosine-1-phosphate

- SM

Sphingomyelin

- NMDAR

N-methyl-Daspartate receptor

- MEs

microemulsions

- PLGA

Polylactic-co-glycolic acid

- PC

Phosphatidylcholines

- TPP

tripolyphosphates

- TCH

thiolated chitosan hydrogel

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- UCN

urocortin peptide

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

All authors in this review have no competing of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

References

- Adhikari A, Mondal S, Das M, Biswas P, Pal U, Darbar S, Bhattacharya SS, Pal D, Saha-Dasgupta T, Das AK, Mallick AK, & Pal SK (2021). Incorporation of a Biocompatible Nanozyme in Cellular Antioxidant Enzyme Cascade Reverses Huntington’s Like Disorder in Preclinical Model. Adv Healthc Mater, 10(7), e2001736. 10.1002/adhm.202001736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal M, Alam MR, Haider MK, Malik MZ, & Kim DK (2020). Alzheimer’s Disease: An Overview of Major Hypotheses and Therapeutic Options in Nanotechnology. Nanomaterials (Basel), 11(1). 10.3390/nano11010059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar A, Andleeb A, Waris TS, Bazzar M, Moradi AR, Awan NR, & Yar M (2021). Neurodegenerative diseases and effective drug delivery: A review of challenges and novel therapeutics. J Control Release, 330, 1152–1167. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akinc A, Maier MA, Manoharan M, Fitzgerald K, Jayaraman M, Barros S, Ansell S, Du X, Hope MJ, Madden TD, Mui BL, Semple SC, Tam YK, Ciufolini M, Witzigmann D, Kulkarni JA, van der Meel R, & Cullis PR (2019). The Onpattro story and the clinical translation of nanomedicines containing nucleic acid-based drugs. Nat Nanotechnol, 14(12), 1084–1087. 10.1038/s41565-019-0591-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Asmari AK, Ullah Z, Tariq M, & Fatani A (2016). Preparation, characterization, and in vivo evaluation of intranasally administered liposomal formulation of donepezil. Drug Des Devel Ther, 10, 205–215. 10.2147/DDDT.S93937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Harthi S, Alavi SE, Radwan MA, El Khatib MM, & AlSarra IA (2019). Nasal delivery of donepezil HCl-loaded hydrogels for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep, 9(1), 9563. 10.1038/s41598-019-46032-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altinoglu G, & Adali T (2020). Alzheimer’s Disease Targeted Nano-Based Drug Delivery Systems. Curr Drug Targets, 21(7), 628–646. 10.2174/1389450120666191118123151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Erviti L, Seow Y, Yin H, Betts C, Lakhal S, & Wood MJ (2011). Delivery of siRNA to the mouse brain by systemic injection of targeted exosomes. Nat Biotechnol, 29(4), 341–345. 10.1038/nbt.1807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amemori T, Jendelova P, Ruzicka J, Urdzikova LM, & Sykova E (2015). Alzheimer’s Disease: Mechanism and Approach to Cell Therapy. Int J Mol Sci, 16(11), 26417–26451. 10.3390/ijms161125961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amiri H, Saeidi K, Borhani P, Manafirad A, Ghavami M, & Zerbi V (2013). Alzheimer’s disease: pathophysiology and applications of magnetic nanoparticles as MRI theranostic agents. ACS Chem Neurosci, 4(11), 1417–1429. 10.1021/cn4001582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arumugam K, Subramanian GS, Mallayasamy SR, Averineni RK, Reddy MS, & Udupa N (2008). A study of rivastigmine liposomes for delivery into the brain through intranasal route. Acta Pharm, 58(3), 287–297. 10.2478/v10007-008-0014-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]