Abstract

Tumor-derived extracellular vesicles (EVs) are promising to monitor early stage cancer. Unfortunately, isolating and analyzing EVs from a patient’s liquid biopsy are challenging. For this, we devised an EV membrane proteins detection system (EV-MPDS) based on Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) signals between aptamer quantum dots and AIEgen dye, which eliminated the EV extraction and purification to conveniently diagnose lung cancer. In a cohort of 80 clinical samples, this system showed enhanced accuracy (100% versus 65%) and sensitivity (100% versus 55%) in cancer diagnosis as compared to the ELISA detection method. Improved accuracy of early screening (from 96.4% to 100%) was achieved by comprehensively profiling five biomarkers using a machine learning analysis system. FRET-based tumor EV-MPDS is thus an isolation-free, low-volume (1 μL), and highly accurate approach, providing the potential to aid lung cancer diagnosis and early screening.

Keywords: extracellular vesicles, Förster resonance energy transfer, membrane proteins, aptamer, lung cancer diagnosis

Lung cancer poses a critical challenge in healthcare due to its high incidence and mortality rates.1 About 70% of lung cancer patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage, and the five year survival rate is only about 15%.2 Currently, lung cancer is typically diagnosed via imaging scans, but these have a poor density resolution, especially at early stage.3 Thus, novel early stage diagnosis approaches such as liquid biopsies and EV-based biomarkers are being explored.4 EVs are membrane-enclosed structures (30–150 nm in diameter) secreted by cells into the extracellular matrix containing various cytosolic materials, which serve as important intercellular communication signals in both physiological and pathological situations.5−8 EVs secreted by cancer cells contain more cancer-associated materials than normal cells and thus have potential as early biomarkers.9,10 Monitoring EVs and their contents in liquid biopsies holds promise for accurate and timely lung cancer diagnosis, facilitating prompt interventions and improving patient outcomes.

Despite growing scientific and clinical interest in tumor-specific EVs, their isolation from body fluids is challenging.10,11 The conventional EV isolation methods can be subdivided into different categories based on the exploited physical/chemical properties: centrifugation-based methods,12,13 size-based isolation,14,15 precipitation,16,17 and affinity-based isolation.18−20 Affinity-based isolation is a commonly utilized method for EV enrichment on lung cancer diagnosis.21,22 Although the common biomarkers such as CD63, CD81, and CD9 are widely used for EV capturing, it is acknowledged that there are currently no “universal” markers for all types of EVs. Thus, important EV subpopulations without the common biomarkers may be underestimated.23 Furthermore, the potential loss of EVs during the isolation process requires the detection to have high sensitivity. To address these challenges, significant efforts have been dedicated to enhance the efficiency of EV isolation.24−26 However, an alternative approach to detect EVs without extraction may offer improved results on lung cancer diagnosis.

Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) is a rapid, sensitive analysis method that has been broadly applied in the biological and biomedical fields.27−30 FRET is a mechanism by which energy is transferred between two closely spaced fluorescent molecules, known as the donor and acceptor molecules. Two important conditions need to be satisfied for the successful application of FRET: First, there must be good overlap between the donor’s emission spectrum and the receptor’s absorption spectrum. Second, the distance between the donor and recipient should fall within a range of 1–10 nm.31 Thus far, most FRET-based studies have mainly focused on detecting EV miRNAs (Table S1). In research centered on EV proteins, laborious washing steps and EV isolation are required, which would significantly prolong the diagnostic process (Table S1).32−34 The FRET approach based on co-localization of protein and EV membrane to avoid EV isolation is lacking. This method thus holds great promise as it avoids the loss of important cancer-associated EV populations.

Additionally, compared to single-target diagnosis, multitarget diagnosis enhances sensitivity and specificity. It focuses on multiple disease-related markers, enabling the detection of a wider range of disease-related alterations and minimizing the risk of false negatives or false positives.35,36 However, successful implementation of multitarget diagnosis necessitates careful marker selection, validation, and integration using appropriate analytical methods and algorithms, in conjunction with machine learning techniques.37−39 Machine learning algorithms examine large-scale data sets, detecting subtle patterns and abnormalities that help to make precise diagnoses, while reducing human error.40

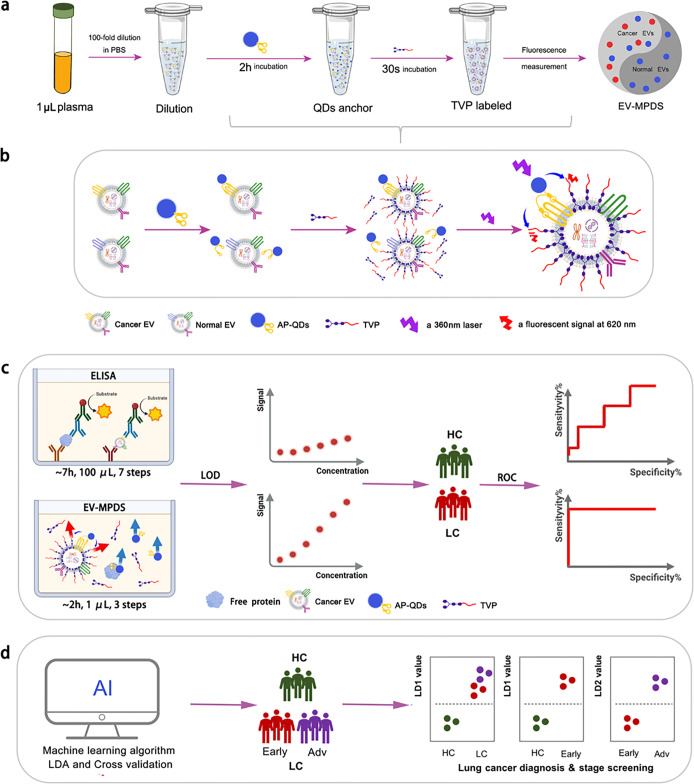

Here we presented a novel system called EV-MPDS, which was capable of detecting EV membrane protein without isolation based on the FRET through EV membrane- and specific protein-labeled probes (Figure 1), eliminating the need for time-consuming EV extraction steps. This system was designed for early diagnosis and staging of lung cancer. We then evaluated the detection capability of this novel method with five lung cancer biomarkers (CD63, CEA, PD-L1, EpCAM, and CA125), which have been reported for good lung cancer diagnosis,25,41−43 on cell lines and clinical samples, compared to the traditional ELISA method. Moreover, we evaluated the benefit of machine learning on improving accuracy in lung cancer early diagnosis and staging. Overall, this work establishes a convenient but accurate blood test to quantify EV surface proteins directly in plasma diluent, which could potentially translate into the clinic to aid lung cancer early diagnosis and staging.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of EV-MPDS. (a) Procedures of EV-MPDS work. (b) Rationale of EV-MPDS via FRET, with aptamer QDs serving as the donor molecule and TVP as the acceptor molecule. (c) EV-MPDS showed lower detection limitation and higher ability of lung cancer diagnosis compared with ELISA. (d) EVMPDS assisted in lung cancer diagnosis, early detection, and staging based on the AI classification.

We started this study with developing donor and acceptor fluorescent molecules for FRET. Currently, membrane receptors such as Dio, Dli, PKH 26, CellMask, etc., suffer from drawbacks such as the need for long incubation periods and the requirement for washing off unbound probes after staining.44 To specifically target the EV membrane through a wash-free and ultrafast staining procedure, we employed a water-soluble AIEgen ((E)-4-(4-(diphenylamino)styryl)-1-(3-(trimethylammonio)propyl)pyridin-1-ium bromide, named TVP).45 Additional aptamer QDs (AP-QDs) were used to label membrane proteins. This labeling strategy allowed us to quantify EV membrane proteins using the FRET effect.

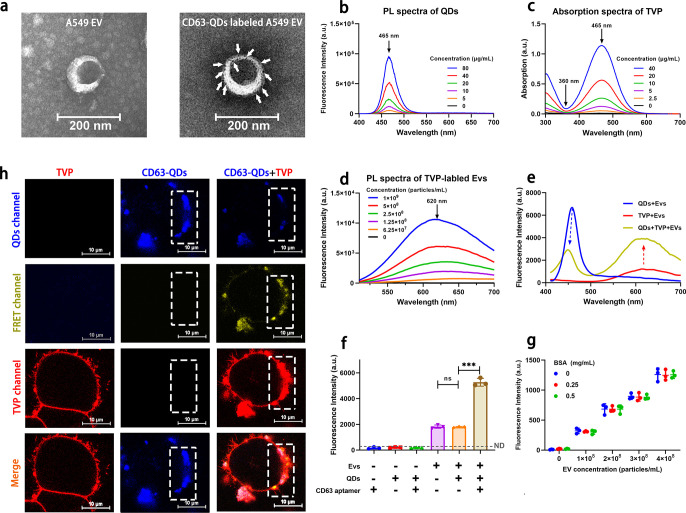

The unique amphiphilic property of TVP enables specific labeling of the lipid membrane45,46 and accurate quantification of EV membrane proteins. We synthesized TVP and confirmed it using NMR (Figures S1–S4). AP-QDs were successfully synthesized by combining CD63-aptamer-NH2 with carboxyl QDs (Figure S5). Then the TEM image confirmed that CD63-aptamer-modified QDs effectively labeled EVs (Figure 2a), validating the ability of AP-QDs to label EV membrane proteins.

Figure 2.

EV-MPDS confirmation. (a) TEM images of A549 EV and CD63 aptamer-QDs labeled A549 EVs. (b) PL spectra of CD63 aptamer QDs at 360 nm laser excitation. (c) Absorption spectra of TVP in the aqueous solutions. (d) PL spectra of TVP-labeled EVs at 465 nm laser excitation. (e) Fluorescence spectra of the QDs, TVPs, and QDs with TVP-labeled EVs under 360 nm laser excitation. (f) Comparison of 620 nm fluorescence intensity of different TVP-labeled samples under excitation at 360 nm. (g) Fluorescence intensity comparison of EVs mixed with BSA at the different concentrations co-labeled with CD63-QDs and TVP. (h) CLSM images of A549 cells labeled with QDs only, TVP only, or both compounds sequentially. (QDs channel: Ex = 405 nm, Em = 450–525 nm; E-FRET channel: Ex = 405 nm, Em = 550–700 nm; TVP channel: Ex = 488 nm, Em = 550–700 nm; scale bar = 10 μm).

In order to evaluate whether QDs and TVP can form a suitable pair for FRET, we proceeded to measure the optical properties of the QDs and TVP. The QDs exhibited a maximum fluorescence emission peak at 465 nm when excited with a 360 nm laser (Figure 2b). On the other hand, the UV–vis absorbance spectra of TVP showed an optimal absorption peak at 465 nm and the lowest absorption at 360 nm (Figure 2c). This indicated that TVP and QDs formed a suitable pair of fluorescent molecules for FRET. Furthermore, TVP-labeled EVs exhibited a maximum fluorescence emission peak at 620 nm when excited with a 465 nm laser (Figure 2d). Therefore, we considered that a fluorescence intensity of 620 nm under a 360 nm laser could be utilized to characterize the expression levels of membrane proteins when co-labeled with QDs and TVP.

The FRET phenomenon between QDs and TVP was observed by measuring the emission spectra of QD-labeled EVs, TVP-labeled EVs, and co-labeled EVs (Figure 2e). The QD signal was significantly lower in the co-labeled group (2.92 times lower than QD group), while the TVP signal was enhanced (2.25 times higher than TVP group) at 360 nm laser excitation, indicating energy transfer from QDs to TVP when co-labeled on EV membranes. Confocal microscopy also confirmed the labeling and FRET effect between QDs and TVP on the A549 cell line (Figures 2h and S6) and EVs (Figure S7). At the same time, the FRET single was observed only when CD63 aptamer QDs, TVP, and EVs were present (Figure 2f). Furthermore, the individual QD group, aptamer group, and aptamer-labeled QD group emitted almost no signals, indicating that excessive QDs, aptamers, and aptamer QDs had no effect on the detection results, and there was no need to remove the free probe in our subsequent detection. With the increase in EV concentration, the samples dual-labeled with CD63-QDs and TVP exhibited enhanced signals; however, the variations in bovine serum albumin (BSA) content had minimal impact on the fluorescence intensity (Figure 2g), indicating the dual-labeling system can be utilized for evaluating EV concentration, while remaining unaffected by the presence of free proteins in the solution.

After EV-MPDS confirmation, we evaluated its detection capability. First, we extracted EVs produced by A549, H1299, and H23 cells for human lung cancer cell lines and a human bronchial epithelial cell line (Beas 2b cell) for the normal cell line using size exclusion chromatography (SEC) at around 50% recovery rate (Figure S8). We then confirmed the successful EV extraction through Western blot (WB) analysis (Figure S8) and TEM image (Figure 3a). Next, we investigated the optimal concentration of TVP for labeling EVs. We found that the signal exhibited a linear correlation within a certain range (6.76 × 104–5.28 × 109 particles/mL) and remained stable within 10 min (Figures S9 and S10).

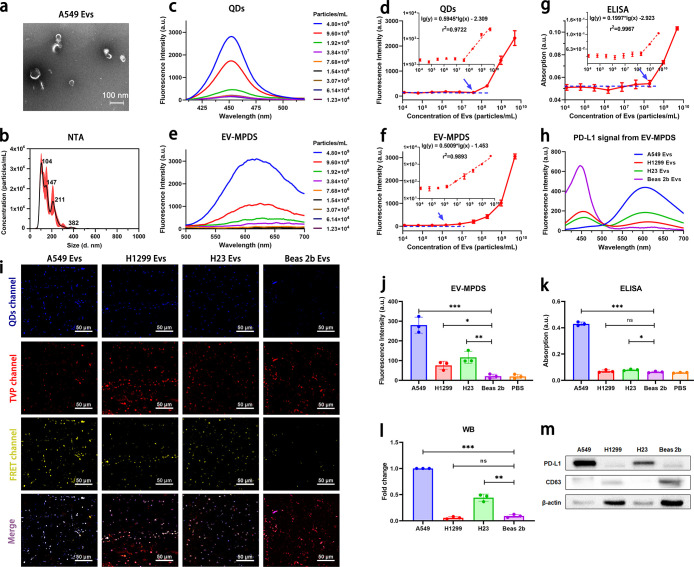

Figure 3.

Performance of EV-MPDS was evaluated. (a, b) TEM images (a) and nanoparticle tracking analysis (b) were conducted to visualize and analyze the EVs extracted from A549 cell supernatant. (c, d) Fluorescence spectra (c) and the relationship between fluorescence intensity and EV concentration (d) were measured for EVs labeled with QDs only at different concentrations. (e, f) The same analysis was performed for EVs detected by EV-MPDS. (g) ELISA analysis was used to determine the relationship between fluorescence intensity and EV concentration. (h–m) PD-L1 was detected on EVs extracted from equal volumes of A549, H1299, H23, and Beas-2b cell supernatant using EV-MPDS, ELISA, and WB. (h) Fluorescence spectra, (i) CLSM images were obtained for the four types of EVs, and (j) the fluorescence intensity analysis in EV-MPDS detection. The PD-L1 expression levels in different samples were analyzed by (k) ELISA and (l) Western blot with (m) representative Western blot images.

To evaluate the detection capability of EV-MPDS, we obtained the A549 EVs with a concentration of 4.80 × 109 particles/mL (Figure 3b). We employed CD63-QDs, EV-MPDS, and ELISA to detect CD63 expression levels on EVs. For CD63-QDs detection, we found that the limit of detection (LOD) was 5.82 × 104 particles/μL (Figure 3c,d), while the LOD of EV-MPDS (Figure 3e,f) was 1.95 × 103 particles/μL. These results suggested that the EV-MPDS method may be more sensitive. This variation could be attributed to the loss of a fraction of EVs during the secondary extraction process necessary to eliminate the free probe. We also used traditional ELISA to analyze the same batch of samples and compared the results with those of EV-MPDS. The calculated LOD for ELISA was 2.48 × 105 particles/μL, which was much higher than that of EV-MPDS (1.95 × 103 particles/μL) (Figure 3g). This significant difference highlights the superior capability of EV-MPDS, which was nearly 100-fold more sensitive than ELISA in detecting EV proteins.

To further evaluate the detection capability of EV-MPDS, we extracted EVs from A549, H1299, H23, and Beas 2b cells using the same volume of supernatant. The PD-L1 expression levels on these EVs were detected by EV-MPDS, ELISA, and WB analysis. Based on the fluorescence spectrum of EV-MPDS (Figure 3h), the FRET signal intensity at 620 nm was highest in A549 EVs, followed by H23 and H1299 EVs. Furthermore, the PD-L1 detection signals from cancer cell lines were all significantly higher than that from the Beas 2b cell line. This trend was also observed in the fluorescence images of FRET channel (Figure 3i) and its quantification (Figure 3j). In the ELISA test results (Figure 3k), the signal levels of A549 and H23 EVs were notably different from Beas 2b EVs, while the distinction between H1299 EVs and Beas 2b EVs was less clear, likely due to the limitations of the ELISA’s limit of detection (LOD). As for WB analysis (Figure 3l,m), it showed a stronger PD-L1 expression level on H23 and Beas 2b EVs compared to EV-MPDS, possibly because not only the proteins present on the EV membrane but also those present in the EV were obtained in WB detection.

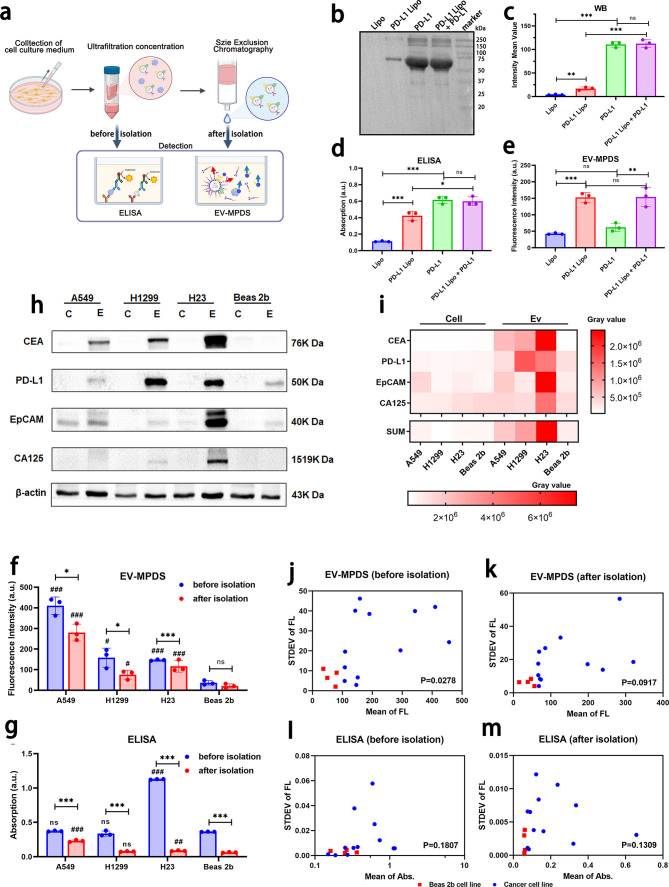

As the EVs recovery rate was only around 50%, indicating a lot of EVs were lost, we attempt to verify whether EV-MPDS was able to detect only the proteins on membrane in a mixed solution for eliminating the need for extraction steps. We first used PD-L1 liposomes to mimic PD-L1 on EVs, which verified by TEM observation of Au nanoparticle-labeled PD-L1 liposome (Figure S11). We measured the PD-L1 level of the liposome group (blank control), PD-L1 group (100 ng of PD-L1), PD-L1 liposome group (50 ng of PD-L1), and a mixture of PD-L1 (50 ng of PD-L1) and PD-L1 liposome (50 ng of PD-L1) groups by WB, ELISA, and EV-MPDS. The results of WB and ELISA were consistent with the total content of PD-L1 in the corresponding group, indicating that the signal determined by WB and ELISA was the sum of free PD-L1 and PD-L1 on the liposome (Figure 4b–d). However, in EV-MPDS detection (Figure 4e), the PD-L1 liposome group showed a similar signal level to that of the mixture group, both of which were much higher than the PD-L1 group. Moreover, there was no significant difference between the PD-L1 group and the liposome group. These findings indicated that EV-MPDS had a minimal detection signal for free PD-L1 and could accurately quantify the signal of the membrane protein in the mixture.

Figure 4.

Detection and classification verification of EV-MPDS in unextracted mixture samples were performed. (a) The process involved preparing and detecting the cell supernatant concentrate before extraction and extractive EVs. (b–e) PD-L1 liposomes were used to mimic PD-L1 on EVs. (b, c) WB analysis, (d) ELISA analysis, and (e) EV-MPDS were conducted to examine liposomes, PD-L1 liposomes, PD-L1, and a mixture of PD-L1 and PD-L1 liposomes. (f, g) PD-L1 abundance was evaluated in the cell supernatant and EVs extracted from the cell supernatant using ELISA (f) and EV-MPDS (g), respectively. (h, i) Four cancer biomarkers (CEA, PD-L1, EpCAM, and CA125) on EVs to distinguish lung cancer cell lines from normal cell line by WB analysis. (h) Representative blot images and (i) a heat map were generated to show the expression of these biomarkers in cell and EV samples. (j–m) Scatter plots were used to verify the expression distribution of biomarkers (CEA, PD-L1, EpCAM, and CA125) in the cell supernatant and EVs extracted from the cell supernatant, as detected by ELISA and EV-MPDS, respectively (# shows the significant differences compared to the Beas 2b group). The study included A549, H1299, and H23 as cancer cell lines and Beas-2b as the normal cell line.

Next, in order to assess the ability of EV-MPDS to detect proteins on the EV membrane in biological samples, we conducted further validation using a cell supernatant concentrate and SEC-extracted EVs, in comparison with ELISA (Figure 4a). In EV-MPDS, the signal obtained from the Beas 2b cell line was significantly lower than that of all the cancer cell lines, both in EVs and in cell supernatant detection (Figure 4f), suggesting that EV-MPDS had the potential to diagnose disease cell lines from normal cell lines, regardless of whether the EVs were extracted. Furthermore, the overall signal levels obtained from cell supernatant were higher than those from the extracted EVs, and the statistical significance between cancer cell lines and normal cell line was higher in the cell supernatant detection, suggesting EV-MPDS without extraction demonstrated a superior ability for diagnosing cancer cell lines. However, in ELISA detection, the signal trends were different (Figure 4g). The levels of PD-L1 on A549 and H23 EVs showed significant differences from those of Beas 2b EVs. However, only the signal in the H23 cell supernatant was significantly higher than the supernatant of Beas 2b. These findings suggested that in ELISA detection, EV-based detection had superior diagnostic ability compared to cell supernatant-based detection. This difference may be caused by the high abundance of secreted PD-L1 in the cell supernatant, which lacks disease specificity.47

Then, we used four cancer biomarkers (CEA, PD-L1, EpCAM, and CA125) on EVs to investigate their combined usage in achieving accurate discrimination. From WB results (Figure 4h,i), the biomarkers were selectively enriched in EVs, but not as abundant in the parent cells at the equal protein content, which may be caused by the process of EV biogenesis involved the sorting and incorporation of specific proteins into the vesicles.25,48,49 This has significant implications for EV as a biomarker in discovery and diagnostic applications. Furthermore, the expression of the indicated biomarkers on EVs derived from the lung cancer cell lines was higher than those derived from normal lung epithelial cells, suggesting that CEA, PD-L1, EpCAM, and CA125 on EVs could serve as a panel of suitable biomarkers for distinguishing lung cancer cells from normal cells. Subsequently, in order to verify the superiority of EV-MPDS in the diagnosis of lung cancer in unextracted samples, we analyzed the expression of the four cancer biomarkers (CEA, PD-L1, EpCAM, and CA125) with or without EVs isolation from the same cell culture volume using ELISA and EV-MPDS. The signals of the extracted EVs showed better distinction as compared to unextracted samples in ELISA detection (Figure 4j–m). In EV-MPDS detection, the signals of the Beas 2b cell line had almost no overlap with the cancer cell lines, both before and after EV isolation. The signal before extraction had higher discrimination ability as compared to the signal after extraction, possibly due to signal loss during the isolation process.

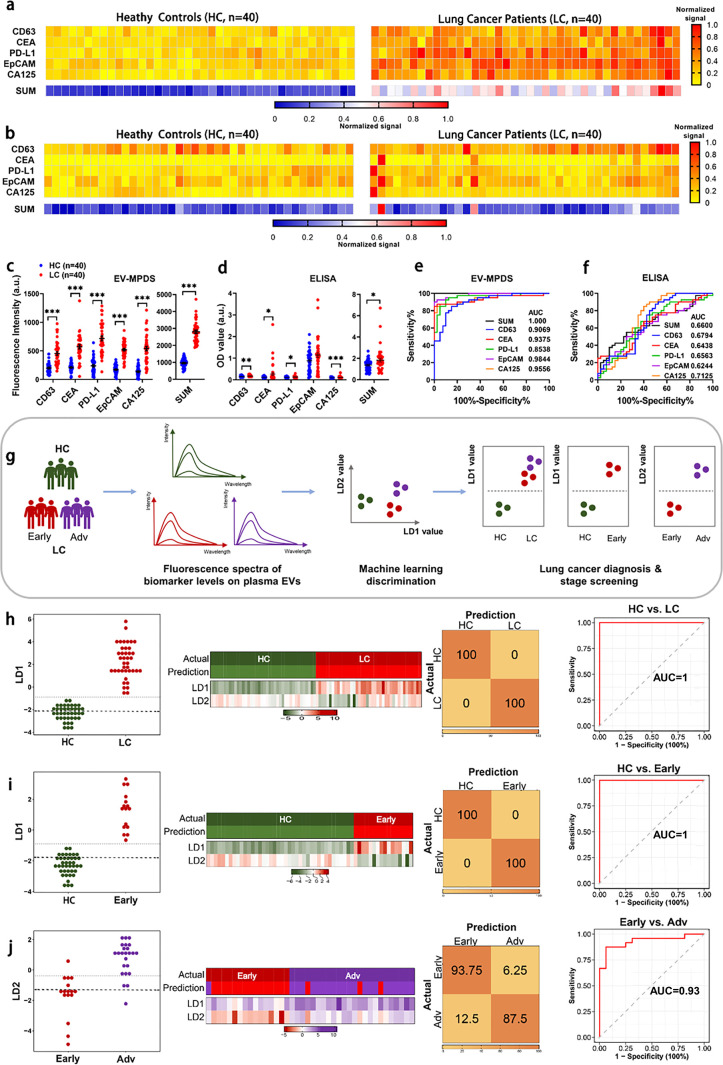

Having shown that EV-MPDS had excellent performance in cell supernatant without EV isolation, we next attempted to assess the clinical potential of EV-MPDS in plasma samples. First, we performed ten independent measurements of PD-L1 levels on EVs from 1 μL of patient plasma (Figure S12), demonstrating the excellent stability and repeatability of the EV-MPDS system in plasma EV detection (CV = 4.07%). Then, we analyzed the expression levels of the five lung cancer biomarkers (CD63, CEA, PD-L1, EpCAM, and CA125) on 80 plasma samples, including 40 lung cancer patients (LC) and 40 healthy controls (HC) by EV-MPDS and ELISA. In EV-MPDS, the expression levels of all biomarkers were higher in the LC group than the HC group (Figure 5a), but there was no obvious difference in ELISA detection (Figure 5b). From the signal scatter plots of five biomarkers, the expression of each biomarker significantly differed between LC and HC individuals in EV-MPDS, leading to successful discrimination of the two groups (Figure 5c). In contrast, ELISA showed only a slight increase in four biomarkers in patient plasma, and the discriminative power was lower as compared to that of EV-MPDS (Figure 5d).

Figure 5.

Diagnosis of lung cancer involves detecting circulating EVs using EV-MPDS and AI classification. A study examined EV samples from 40 lung cancer patients and 40 healthy controls, assessing five key lung cancer protein markers (CD63, CEA, PD-L1, EpCAM, and CA125). (a, b) Heat maps were generated to show cancer biomarker protein profiles using (a) EV-MPDS and (b) ELISA methods. (c, d) Scatter plots of the five EV biomarkers were created for plasma samples analyzed by (c) EV-MPDS and (d) ELISA. (e, f) ROC curve analysis evaluated the diagnostic power of the individual biomarkers and the SUM signature using (e) EV-MPDS and (f) ELISA. (g) Flowchart of signals obtained by EV-MPDS followed by a weighted ensemble classification system. (h–j) LDA-based analysis of EV biomarkers was used for lung cancer detection, providing LD1 or LD2 values for control and lung cancer group samples. Heat maps, confusion matrices, and ROC curves were generated for different comparisons, including (h) control vs lung cancer group, (i) control vs early stage lung cancer group, and (j) early stage vs advanced-stage lung cancer group.

Then, we assessed the ability of EV-MPDS and ELISA to differentiate between lung cancer patients and healthy individuals using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. In EV-MPDS, each of the five biomarkers had good diagnostic accuracy; the unweighted SUM analysis has a certain enhancement effect on the diagnostic ability (AUC = 1) (Figure 5e). In contrast, ELISA had a significantly lower overall AUC (AUC = 0.66) as compared to EV-MPDS (Figure 5f), indicating that EV-MPDS was more accurate in detecting these biomarkers in plasma. Next, the sensitivity and specificity of EV-MPDS and ELISA were separately calculated (Table S2). For EV-MPDS, the unweighted SUM significantly enhanced the sensitivity and specificity of the assay as well as the diagnostic accuracy (100%). However, for ELISA, the diagnostic accuracy decreased from 72.5% (CA125) to 65% (unweighted SUM) (Table S2). Finally, to perform a more intuitive analysis, we analyzed both cohort and correlations (Figure S13) of the unweighted SUM signal distribution using cutoff values for EV-MPDS and ELISA, which confirmed that EV-MPDS exhibited higher discriminative power than ELISA.

Furthermore, we wanted to evaluate the performance of EV-MPDS under different diagnostic scenarios. Specifically, we explored its potential for both early cancer detection and cancer staging. All test markers were able to distinguish heathy control (HC) and early stage (stage I/II) (Early) samples, while CEA, EpCAM, and CA125 were able to distinguish Early from advanced lung cancer (stage III/IV) (Adv) (Figure S14). We obtained an overall accuracy of 96.4% for lung cancer early diagnosis (Table S3) and 85.0% for staging (Table S4).

In order to further improve the accuracy of EV-MPDS, we developed a machine learning intelligence analysis system. Here, we used LDA50 with leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) on our EV data and identified a linear combination of the five biomarkers when detecting different EV groups. Hence, LD1 and LD2 values for each sample were generated (Figure 5g). Three submodels were defined according to the different comparisons: namely, HC vs lung cancer group (LC), HC vs Early, and Early vs Adv, based on the two values.

The values of LD1 and LD2 for all samples were obtained with eqs 1 and 2, respectively.

| 1 |

| 2 |

In the HC vs LC and HC vs Early comparisons, based on the computed formula for LD1, we found that EpCAM had the highest weight coefficient (1.21), followed by CEA (0.58) and CA125 (0.81). This indicates a stronger correlation between these biomarkers and lung cancer as well as early stage lung cancer development. Furthermore, in the Early vs Adv comparison, according to the computed formula for LD2, we observed that PD-L1 had the highest negative weight coefficient (−1.6), while CA125 had the highest positive weight coefficient (0.85). This finding aligns with the trends observed in current relevant literature.51−53 Furthermore, these three groups of samples were significantly distinguished by the LD1 and LD2 values (Figure S15). In particular, HC versus LC and HC versus Early were markedly separated by their LD1 values, with the corresponding AUC value, sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy being 1 (Figure 5h,i and Table S5). Meanwhile, Early versus Adv were markedly separated by LD2, with an AUC value of 0.93, a sensitivity of 0.94, a specificity of 0.88, and an accuracy of 0.90 (Figure 5j and Table S5). Both of these data sets were higher than the result of a simple unweighted sum. Taken together, the profiling of EV biomarkers using EV-MBDS and subsequent analysis using a machine learning algorithm such as LDA represent a viable, accurate method, through which lung cancer can be diagnosed at an early stage in clinical practice.

In this study, we developed and validated a novel method called EV-MPDS for the selective detection and quantification of EV membrane-bound proteins. The method utilizes a FRET interaction between a membrane probe (TVP) and aptamer QDs. This FRET signal is observed only when both the membrane structure and the specific protein of interest are present, effectively eliminating interference from free proteins. EV-MPDS offers a simple and rapid approach with improved sensitivity compared to traditional ELISA. One of the key advantages of EV-MPDS is its ability to analyze EVs directly from the cell culture supernatant or blood, eliminating the need for complex EV extraction procedures that can lead to sample heterogeneity and potential errors. By combining multiplex quantification of five biomarkers and machine learning analysis, EV-MPDS enables the accurate detection of early lung cancer, surpassing the limitations of single biomarker approaches. In the future, we will endeavor to establish a universal EV-MPDS protocol to accurately discriminate cancer EVs from various types of cancer to facilitate cancer diagnosis and precision therapeutics in the clinic.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere gratitude to the Advanced Cell Technology Core Facility of Guangzhou Laboratory. We also express our heartfelt thanks to Tanghui Liu for her invaluable assistance with fluorescence spectra and intensity detection. Furthermore, we deeply appreciate the support provided by the Advanced Bioimaging Technology Core Facility of Guangzhou Laboratory. Our gratitude extends to Yu Fu for her valuable contributions to cell and EV confocal imaging. We acknowledge the indispensable assistance of Wandong Chen from Guangzhou Laboratory in the preparation of NHS liposomes. Additionally, we are thankful to Heying Li from the Guangzhou Institutes of Biomedicine and Health for her guidance in preparing TEM samples and analyzing TEM images.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.nanolett.3c02193.

Additional experimental details and data, including the characterization of TVP and aptamer QDs, detection conditions of EV-MPDS, and summary of lung cancer diagnostic statistics in different detection methods (PDF)

Author Contributions

# S.X., Y.Y., and S.L. contributed equally to this work. S.X. conceived the project, performed the majority of the experimental procedure, performed the data analysis, and wrote the manuscript. Y.Y. performed clinical samples collection and processing. S.L. performed the machine learning model building and wrote the manuscript. B.X. and Q.S. contributed to some experiments of clinical samples. H.T., L.Z., Y.Z., and Q.C. contributed to data analysis and manuscript revision. X.L. contributed to EVs isolation and discussion. M.D. conceived the project and supervised the study.

This work was financially supported by the Start-up Foundation of Guangzhou National Laboratory (YW-JCZD0101).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Sung H.; Ferlay J.; Siegel R. L.; Laversanne M.; Soerjomataram I.; Jemal A.; Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71 (3), 209–249. 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastorino U.; Silva M.; Sestini S.; Sabia F.; Boeri M.; Cantarutti A.; Sverzellati N.; Sozzi G.; Corrao G.; Marchianò A. Prolonged lung cancer screening reduced 10-year mortality in the MILD trial: new confirmation of lung cancer screening efficacy. Ann. Oncol 2019, 30 (7), 1162–1169. 10.1093/annonc/mdz117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby D.; Bhatia S.; Brindle K. M.; Coussens L. M.; Dive C.; Emberton M.; Esener S.; Fitzgerald R. C.; Gambhir S. S.; Kuhn P.; Rebbeck T. R.; Balasubramanian S. Early detection of cancer. Science 2022, 375 (6586), eaay9040. 10.1126/science.aay9040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue Y.; Feng X.; Fan X.; Zhu G.; McLaughlan J.; Zhang W.; Chen X. Extracellular Vesicles for the Diagnosis of Cancers. Small Structures 2022, 3 (1), 2100096. 10.1002/sstr.202100096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalluri R.; LeBleu V. S. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science 2020, 367 (6478), eaau6977. 10.1126/science.aau6977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenich D. S.; Omizzollo N.; Szczepanski M. J.; Reichert T. E.; Whiteside T. L.; Ludwig N.; Braganhol E. Small extracellular vesicle-mediated bidirectional crosstalk between neutrophils and tumor cells. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2021, 61, 16–26. 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2021.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möller A.; Lobb R. J. The evolving translational potential of small extracellular vesicles in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2020, 20 (12), 697–709. 10.1038/s41568-020-00299-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marar C.; Starich B.; Wirtz D. Extracellular vesicles in immunomodulation and tumor progression. Nat. Immunol 2021, 22 (5), 560–570. 10.1038/s41590-021-00899-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makler A.; Asghar W. Exosomal biomarkers for cancer diagnosis and patient monitoring. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn 2020, 20 (4), 387–400. 10.1080/14737159.2020.1731308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W.; Hurley J.; Roberts D.; Chakrabortty S. K.; Enderle D.; Noerholm M.; Breakefield X. O.; Skog J. K. Exosome-based liquid biopsies in cancer: opportunities and challenges. Ann. Oncol 2021, 32 (4), 466–477. 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.01.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.; Xu Y.; Lu Y.; Xing W. Isolation and Visible Detection of Tumor-Derived Exosomes from Plasma. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90 (24), 14207–14215. 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b03031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eitan E.; Zhang S.; Witwer K. W.; Mattson M. P. Extracellular vesicle-depleted fetal bovine and human sera have reduced capacity to support cell growth. J. Extracell Vesicles 2015, 4, 26373. 10.3402/jev.v4.26373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan K.; Martin K.; FitzGerald S. P.; O’Sullivan J.; Wu Y.; Blanco A.; Richardson C.; Mc Gee M. M. A comparison of methods for the isolation and separation of extracellular vesicles from protein and lipid particles in human serum. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10 (1), 1039. 10.1038/s41598-020-57497-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidhom K.; Obi P. O.; Saleem A. A Review of Exosomal Isolation Methods: Is Size Exclusion Chromatography the Best Option?. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21 (18), 6466. 10.3390/ijms21186466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busatto S.; Vilanilam G.; Ticer T.; Lin W. L.; Dickson D. W.; Shapiro S.; Bergese P.; Wolfram J. Tangential Flow Filtration for Highly Efficient Concentration of Extracellular Vesicles from Large Volumes of Fluid. Cells 2018, 7 (12), 273. 10.3390/cells7120273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi E. S.; Faruque H. A.; Kim J. H.; Kim K. J.; Choi J. E.; Kim B. A.; Kim B.; Kim Y. J.; Woo M. H.; Park J. Y.; et al. CD5L as an Extracellular Vesicle-Derived Biomarker for Liquid Biopsy of Lung Cancer. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021, 11 (4), 620. 10.3390/diagnostics11040620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu Z.; Pang R. T. K.; Liu W.; Li Q.; Cheng R.; Yeung W. S. B. Polymer-based precipitation preserves biological activities of extracellular vesicles from an endometrial cell line. PLoS One 2017, 12 (10), e0186534 10.1371/journal.pone.0186534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liangsupree T.; Multia E.; Riekkola M. L. Modern isolation and separation techniques for extracellular vesicles. J. Chromatogr. A 2021, 1636, 461773. 10.1016/j.chroma.2020.461773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondal S. K.; Whiteside T. L. Immunoaffinity-Based Isolation of Melanoma Cell-Derived and T Cell-Derived Exosomes from Plasma of Melanoma Patients. Methods Mol. Biol. 2021, 2265, 305–321. 10.1007/978-1-0716-1205-7_23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Chen Y.; Pei F.; Zeng C.; Yao Y.; Liao W.; Zhao Z. Extracellular Vesicles in Liquid Biopsies: Potential for Disease Diagnosis. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 6611244. 10.1155/2021/6611244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandfeld-Paulsen B.; Jakobsen K. R.; Bæk R.; Folkersen B. H.; Rasmussen T. R.; Meldgaard P.; Varming K.; Jorgensen M. M.; Sorensen B. S. Exosomal Proteins as Diagnostic Biomarkers in Lung Cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2016, 11 (10), 1701–1710. 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S.; Hu T.; Han G.; Wu Y.; Hua X.; Su J.; Jin W.; Mou Y.; Mou X.; Li Q.; Liu S. Accurate Cancer Diagnosis and Stage Monitoring Enabled by Comprehensive Profiling of Different Types of Exosomal Biomarkers: Surface Proteins and miRNAs. Small 2020, 16 (48), e2004492 10.1002/smll.202004492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irmer B.; Chandrabalan S.; Maas L.; Bleckmann A.; Menck K. Extracellular Vesicles in Liquid Biopsies as Biomarkers for Solid Tumors. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15 (4), 1307. 10.3390/cancers15041307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng J.; Tian F.; Liu C.; Liu Y.; Zhao S.; Fu T.; Sun J.; Tan W. Rapid One-Step Detection of Viral Particles Using an Aptamer-Based Thermophoretic Assay. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143 (19), 7261–7266. 10.1021/jacs.1c02929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L.; Wang H.; Fu J.; Wu X.; Liang X. Y.; Liu X. Y.; Wu X.; Cao L. L.; Xu Z. Y.; Dong M. Microfluidic-based exosome isolation and highly sensitive aptamer exosome membrane protein detection for lung cancer diagnosis. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 214, 114487. 10.1016/j.bios.2022.114487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Greene J. A.; Hernández-Ortega K.; Quiroz-Baez R.; Resendis-Antonio O.; Pichardo-Casas I.; Sinclair D. A.; Budnik B.; Hidalgo-Miranda A.; Uribe-Querol E.; Ramos-Godínez M. D. P.; et al. Quantitative proteomic analysis of extracellular vesicle subgroups isolated by an optimized method combining polymer-based precipitation and size exclusion chromatography. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2021, 10 (6), e12087 10.1002/jev2.12087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai W. Q.; Chang Y. F.; Chou F. N.; Yang D. M. Portable FRET-Based Biosensor Device for On-Site Lead Detection. Biosensors 2022, 12 (3), 157. 10.3390/bios12030157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milićević D.; Hlaváč J. Triple-FRET multi-purpose fluorescent probe for three-protease detection. RSC Adv. 2022, 12 (44), 28780–28787. 10.1039/D2RA05125G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapkota K.; Dhakal S. FRET-Based Aptasensor for the Selective and Sensitive Detection of Lysozyme. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland) 2020, 20 (3), 914. 10.3390/s20030914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L.; Wang J.; Xia S.; Wang X.; Yu Y.; Zhou H.; Liu H. A FRET-based near-infrared ratiometric fluorescent probe for detection of mitochondria biothiol. Talanta 2020, 219, 121296. 10.1016/j.talanta.2020.121296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jares-Erijman E. A.; Jovin T. M. FRET imaging. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003, 21 (11), 1387–1395. 10.1038/nbt896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L.; Xu Y.; Wei X.; Lin H.; Huang M.; Lin B.; Song Y.; Yang C. Coupling Aptamer-based Protein Tagging with Metabolic Glycan Labeling for In Situ Visualization and Biological Function Study of Exosomal Protein-Specific Glycosylation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2021, 60 (33), 18111–18115. 10.1002/anie.202103696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu N.; Li G.; Zhou J.; Zhang Y.; Kang K.; Ying B.; Yi Q.; Wu Y. A light-up fluorescence resonance energy transfer magnetic aptamer-sensor for ultra-sensitive lung cancer exosome detection. J. Mater. Chem. B 2021, 9 (10), 2483–2493. 10.1039/D1TB00046B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panagopoulou M. S.; Wark A. W.; Birch D. J. S.; Gregory C. D. Phenotypic analysis of extracellular vesicles: a review on the applications of fluorescence. J. Extracell Vesicles 2020, 9 (1), 1710020. 10.1080/20013078.2019.1710020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muinao T.; Deka Boruah H. P.; Pal M. Multi-biomarker panel signature as the key to diagnosis of ovarian cancer. Heliyon 2019, 5 (12), e02826 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapitz A.; Azkargorta M.; Milkiewicz P.; Olaizola P.; Zhuravleva E.; Grimsrud M. M.; Schramm C.; Arbelaiz A.; O’Rourke C. J.; La Casta A.; et al. Liquid biopsy-based protein biomarkers for risk prediction, early diagnosis, and prognostication of cholangiocarcinoma. Journal of Hepatology 2023, 79 (1), 93–108. 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y.; Sun L.; Liu W.; Yang L.; Song Z.; Ning X.; Li W.; Tan M.; Yu Y.; Li Z. Multiplex single-cell droplet PCR with machine learning for detection of high-risk human papillomaviruses. Analytica Chimica Acta 2023, 1252, 341050. 10.1016/j.aca.2023.341050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D.; Hu J.; Zhang L.; Li L.; Yin Q.; Shi J.; Guo H.; Zhang Y.; Zhuang P. Deep learning and machine intelligence: New computational modeling techniques for discovery of the combination rules and pharmacodynamic characteristics of Traditional Chinese Medicine. European Journal of Pharmacology 2022, 933, 175260. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2022.175260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C.; Zhao J.; Tian F.; Cai L.; Zhang W.; Feng Q.; Chang J.; Wan F.; Yang Y.; Dai B.; et al. Low-cost thermophoretic profiling of extracellular-vesicle surface proteins for the early detection and classification of cancers. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 3 (3), 183–193. 10.1038/s41551-018-0343-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson K.; Wu E.; Zhang A.; Alizadeh A. A.; Zou J. From patterns to patients: Advances in clinical machine learning for cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Cell 2023, 186 (8), 1772–1791. 10.1016/j.cell.2023.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan L.; Chen Y.; Ke L.; Zhou Q.; Chen J.; Fan M.; Wuethrich A.; Trau M.; Wang J. Plasma extracellular vesicle phenotyping for the differentiation of early-stage lung cancer and benign lung diseases. Nanoscale Horiz 2023, 8 (6), 746–758. 10.1039/D2NH00570K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saad H. M.; Tourky G. F.; Al-Kuraishy H. M.; Al-Gareeb A. I.; Khattab A. M.; Elmasry S. A.; Alsayegh A. A.; Hakami Z. H.; Alsulimani A.; Sabatier J. M.; et al. The Potential Role of MUC16 (CA125) Biomarker in Lung Cancer: A Magic Biomarker but with Adversity. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022, 12 (12), 2985. 10.3390/diagnostics12122985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng S.; Wang R.; Zhang X.; Ma Y.; Zhong L.; Li K.; Nishiyama A.; Arai S.; Yano S.; Wang W. EGFR-TKI resistance promotes immune escape in lung cancer via increased PD-L1 expression. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18 (1), 165. 10.1186/s12943-019-1073-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y.; Zhu Y.; Youngblood H. A.; Almuntashiri S.; Jones T. W.; Wang X.; Liu Y.; Somanath P. R.; Zhang D. Nebulization of extracellular vesicles: A promising small RNA delivery approach for lung diseases. J. Controlled Release 2022, 352, 556–569. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2022.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D.; Su H.; Kwok R. T. K.; Hu X.; Zou H.; Luo Q.; Lee M. M. S.; Xu W.; Lam J. W. Y.; Tang B. Z. Rational design of a water-soluble NIR AIEgen, and its application in ultrafast wash-free cellular imaging and photodynamic cancer cell ablation. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9 (15), 3685–3693. 10.1039/C7SC04963C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X.; Wang D.; Xu W.; Cao S.; Peng Q.; Tang B. Z. Charge control of fluorescent probes to selectively target the cell membrane or mitochondria: theoretical prediction and experimental validation. Materials Horizons 2019, 6 (10), 2016–2023. 10.1039/C9MH00906J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li C.; Li C.; Zhi C.; Liang W.; Wang X.; Chen X.; Lv T.; Shen Q.; Song Y.; Lin D.; Liu H. Clinical significance of PD-L1 expression in serum-derived exosomes in NSCLC patients. J. Transl. Med. 2019, 17 (1), 355. 10.1186/s12967-019-2101-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eirin A.; Zhu X. Y.; Puranik A. S.; Woollard J. R.; Tang H.; Dasari S.; Lerman A.; van Wijnen A. J.; Lerman L. O. Comparative proteomic analysis of extracellular vesicles isolated from porcine adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem/stromal cells. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36120. 10.1038/srep36120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poggio M.; Hu T.; Pai C.-C.; Chu B.; Belair C. D.; Chang A.; Montabana E.; Lang U. E.; Fu Q.; Fong L.; Blelloch R.; et al. Suppression of Exosomal PD-L1 Induces Systemic Anti-tumor Immunity and Memory. Cell 2019, 177 (2), 414–427.e413. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xanthopoulos P.; Pardalos P. M.; Trafalis T. B.; Xanthopoulos P.; Pardalos P. M.; Trafalis T. B. Linear discriminant analysis. Robust Data Mining 2013, 27–33. 10.1007/978-1-4419-9878-1_4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q.; Chen M.; Gu J.; Niu K.; Zhao X.; Zheng L.; Xu Z.; Yu Y.; Li F.; Meng L.; et al. Novel Biomarkers of Dynamic Blood PD-L1 Expression for Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Patients. Frontiers in Immunology 2021, 12, 665133. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.665133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou N.; Wang H.; Liu H.; Xue H.; Lin F.; Meng X.; Liang A.; Zhao Z.; Liu Y.; Qian H. MTA1-upregulated EpCAM is associated with metastatic behaviors and poor prognosis in lung cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 34, 157. 10.1186/s13046-015-0263-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura Y.; Fujii T.; Hamamoto K.; Miyagawa N.; Kataoka M.; Iio A. Serum CA125 level is a good prognostic indicator in lung cancer. Br. J. Cancer 1990, 62 (4), 676–678. 10.1038/bjc.1990.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.