ABSTRACT

Orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) is the standard of care for patients suffering from end stage liver disease (ESLD). This is a high-risk procedure with the potential for hemorrhage, large shifts in preload and afterload, and release of vasoactive mediators that can have profound effects on hemodynamic equilibrium. In addition, patients with ESLD can have preexisting coronary artery disease, cirrhotic cardiomyopathy, porto-pulomary hypertension and imbalanced coagulation. As cardiovascular involvement is invariable and patient are at an appreciable risk of intraoperative cardiac arrest, Trans esophageal echocardiography (TEE) is increasingly becoming a routinely utilized monitor during OLT in patients without contraindications to its use. A comprehensive TEE assessment performed by trained operators provides a wealth of information on baseline cardiac function, while a focused study specific for the ESLD patients can help in prompt diagnosis and treatment of critical events. Future studies utilizing TEE will eventually optimize examination safety, quality, permit patient risk stratification, provide intraoperative guidance, and allow for evaluation of graft vasculature.

Keywords: Hemodynamic assessment, liver transplantation, transesophageal echocardiography

INTRODUCTION

Orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) is the standard of care for end-stage liver disease (ESLD) patients. In the USA alone, 9236 liver transplants were performed in 2021.[1] OLT is a high-risk procedure with the potential for hemorrhage, large shifts in both preload and afterload, and release of vasoactive mediators, especially during reperfusion, that profoundly affect hemodynamic equilibrium. Moreover, these upsets occur in patients often suffering acute decompensation of an organ whose integral functions have wide-ranging effects on other organs.[2,3] Other unique considerations, including release of tense ascites, temporary occlusion the inferior vena cava, and reperfusion, are well-known to affect hemodynamics. Given that cardiac arrest has been seen to occur in up to 5% of patients undergoing OLT,[4] the ability to directly visualize causative pathology would seem invaluable. Although TEE has been used in liver transplantation since the 1980’s,[5,6] its use has been sporadic. However, transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) usage during OLT has dramatically increased over the past decade. This review will summarize and discuss some of the evidence supporting the utility of transesophageal echocardiography during liver transplantation.

Echocardiography in the preoperative assessment of liver transplant recipients

Echocardiography plays an important role in the preoperative assessment of patients contemplated for liver transplantation.[7] Cardiovascular system involvement is almost invariable in patients with end-stage liver disease (ESLD).[8] Cardiac failure furthermore poses a significant risk to the transplant recipient,[9] being the third most common cause of morbidity and mortality at both 30 days and one year post-transplantation. An anatomical study including 133 patients with cirrhosis revealed 43% to have significant macroscopic cardiac abnormalities, the most common being cardiomegaly and left ventricular hypertrophy.[10] Echocardiography provides invaluable information on cardiac chamber size, contractility, and wall motion abnormalities. Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy (CCM) is a well-defined entity with prevalence rates varying anywhere from 26%-81%.[8-11] It is characterized by systolic and diastolic dysfunction and electrophysiological abnormalities such as QT interval prolongation.[12] Its prevalence is related to the severity of cirrhosis but independent of the etiology of liver disease. Due to the usually asymptomatic and subclinical nature of cirrhotic cardiomyopathy, it manifests only during periods of stress, and it may be only diagnosed in the preoperative echocardiography.[12] While liver transplantation may reverse CCM, a small percentage of transplant recipients develop heart failure in the post-transplant period.[13] Specific echocardiographic criteria were proposed by the Cirrhotic Cardiomyopathy Consortium (2019) for its diagnosis[14] [Table 1]. Before settling on a diagnosis of CCM, diminished left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) or global longitudinal strain (GLS), which is reported as a negative value, should prompt consideration of ischemic cardiomyopathy as an important differential diagnosis and warrants investigation by coronary angiography.

Table 1.

Cirrhotic Cardiomyopathy Consortium (2019), proposed criteria for the diagnosis of cirrhotic cardiomyopathy[14]

| Systolic dysfunction Any of the below | Advanced diastolic dysfunction ≥3 of the below | Areas for future research (Require further validation) |

|---|---|---|

| LV ejection fraction ≤50% | Septal e′ velocity <7 cm/sec | Abnormal chronotropic or inotropic response§ |

| Absolute* GLS <18% | E/e′ ratio ≥15 | Electrocardiographic changes |

| LAVI >34 mL/m2 | Electromechanical uncoupling | |

| TR velocity >2.8 m/sec‡ | Myocardial mass change | |

| Serum biomarkers | ||

| Chamber enlargement | ||

| CMRI∥ |

LV=left ventricle, E=early diastolic mitral inflow velocity, e′ = early diastolic mitral annular tissue velocity, GLS=global longitudinal strain, LAVI=left atrial volume index, TR=tricuspid regurgitation, CMRI=cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. *GLS is reported as a negative value in echocardiography reports. Changes in GLS should be described as changes in the absolute value. ‡In the absence of evidence of primary pulmonary hypertension or portopulmonary hypertension. §Examples include absence of, or blunted contractile or diastolic reserve on exercise stress testing, dobutamine stress testing, or at rest on CMRI. ∥Myocardial extracellular volume as a surrogate for myocardial fibrosis can be assessed using this modality

ESLD also has deleterious effects on the respiratory system, with sequelae affecting the right heart. Right heart failure is a significant cause of morbidity in cirrhotic disease. Two particular contributing factors include hepatopulmonary syndrome (HPS) and porto-pulmonary hypertension (PoPH).[15,16] Tricuspid regurgitation (TR) velocity may indicate the variant disease states in cirrhosis patients. While its elevation may be consistent with diastolic dysfunction, it can also be a marker of pulmonary hypertension, albeit one that cannot distinguish pulmonary venous (postcapillary) from pulmonary arterial (precapillary) hypertension. In the absence of elevated left ventricular (LV) filling pressures due to diastolic dysfunction, its elevation may be more consistent with precapillary hypertension and PoPH. The E/A ratio is <0.8, and E/e’ is <15.[14] Pulmonary hypertension may worsen during reperfusion leading to hypoxia and right ventricular (RV) dysfunction. Diagnosis of this condition might prompt the preemptive use of inodilators, such as milrinone, with severe cases potentially warranting inhaled nitric oxide use. Unfortunately, currently available validated data cannot classify RV function into discriminate categories of mild, moderate, or severe.[17,18] Based on current guidelines, only a dichotomous approach to RV impairment is feasible.[19] Severe PoPH associated with RV dysfunction is considered a contraindication to liver transplantation.[20] While recent practice guidelines suggest cancellation of OLT if the mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) exceeds 50 mmHg, in situations where mPAP lies between 35 and 50 mmHg, outcomes may be favorable when pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) is normalized with pulmonary vasodilatory therapy.[21]

A recent meta-analysis has suggested that defining PoPH into mild, moderate, and severe before LT can allow for the appropriate selection of patients who would have outcomes similar to those without PoPH. Identifying threshold values of mPAP in PoPH patients that predict poorer outcomes after transplant or provide guidance about which patients would benefit from specific treatment of their PoPH before OLT will be good questions for future work in this field.[20] Another deleterious effect of ESLD on the respiratory system is HPS. An echocardiographic bubble study, where agitated saline contrast may be seen entering the left atrium via pulmonary veins, is an important tool for diagnosing HPS. Overall, the RV function is one of the major determining factors for listing patients for liver transplantation. It is especially important in ESLD patients with PoPH and is easily assessed by the echocardiography.[15]

Intraoperative TEE during liver transplantation

Intraoperative cardiac arrest (ICA), which is reported to occur in 1 in 10,000 anesthetics, has a much higher incidence during OLT. One study reported an incidence of ICA up to 5%.[4] A recent study reported an incidence of 3.7% of ICA in over five thousand liver transplants,[22] over 90% of these being from deceased donors. Intraoperative mortality was 31.6% in ICA victims. Another large cohort study including 41,324 patients[23] examined factors leading to death within 24 hours of transplantation. Survival to 30 days post-OLT was 92.6%. Death within 24 hours was rare, but the causes included uncontrolled hemorrhage (0.14%), intracardiac or pulmonary thromboembolism (0.13%), and primary graft failure (0.12%). Other causes of mortality included pulmonary hypertension/right heart failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome, myocardial infarction, cardiac arrhythmias, hyperkalemic arrest, graft failure due to vascular thrombosis, congestive heart failure, cerebral edema/uncal herniation, intracranial hemorrhage, air embolism, embolic stroke, reperfusion, cardiac tamponade, and anaphylaxis (all <0.1%). Many of these conditions have recognizable echocardiographic manifestations, and multiple case reports exist of TEE facilitating their diagnosis and management.

TEE provides a wealth of important information regarding cardiac function, adequacy of preload, and presence of cardiac thrombo- or air embolism, all of which may be relevant to the diagnosis and management of critical physiologic disturbances during liver transplantation.[6,24-30] While there are no randomized trials, there are numerous case reports, case series, and retrospective cohorts supporting the utility of TEE during OLT. TEE has been used to diagnose successfully and prompt an alteration in patient management in cases of dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (LVOTO) with systolic anterior motion (SAM) of the anterior mitral leaflet,[31-36] unexpected cardiogenic shock,[37,38] isolated right ventricular failure,[5] Takotsubo cardiomyopathy,[39] cardiac tamponade,[40] intracardiac thrombosis/pulmonary embolism,[41-46] inferior vena cava stenosis,[47] trans-jugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt thrombosis,[48] and hypovolemia.[49] Even outside of frank cardiac arrest, these pathologies are not uncommon.

A cohort study evaluating the safety and impact of TEE[50] found it affected management in 64% of patients, with a major impact in 11%. Another retrospective cohort[51] of 100 patients undergoing OLT at a single institution examined abnormal intraoperative TEE findings by surgical phase and assessed their relationship to major postoperative adverse cardiac events. Patients experienced micro-emboli (44%), right ventricular (RV) dysfunction (42%), thromboembolic (37%: intracardiac 32%, pulmonary 5%), patent foramen ovale (PFO) (left-to-right shunt 37%, right-to-left shunt 8%), biventricular dysfunction (24%), hyperdynamic left ventricular (LV) function (24%), hypovolemia (22%), and LV dysfunction (mild 16%, moderate-severe 4%). Biventricular dysfunction and intracardiac thrombosis are independent predictors of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and mortality. The preponderance of these data has led the Society for the Advancement of Transplant Anesthesia to conclude that: a) TEE use in patients undergoing liver transplant is effective and safe and b) TEE use can improve outcomes in liver transplant patients in rare but life-threatening conditions.[52]

Safety of TEE in ESLD patients

While TEE is generally considered safe, probe placement and manipulation do have the potential to cause injury. Contraindications to TEE have been well-described.[53] An American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) 2010 review on safety of TEE lists several [Table 2] contraindications to its use. The same review describes the rate of intraoperative TEE-related complications as ranging from 0.2 to 1.2%. Of particular concern with TEE is the potential disruption of esophageal varices. In patients with ongoing hepatic disease, varices can be expected to worsen over time,[54] potentially adding to this concern. A case report[55] describes variceal disruption complicated by intractable hemorrhage during liver transplantation. The authors caution against using TEE in patients with grade 3 or actively bleeding varices and make suggestions to increase the safety of its use in this population hopefully. Despite these concerns, accumulating data supports the safety of TEE during liver transplantation.[30,56-61]

Table 2.

Contraindications of transesophageal echocardiography[53]

| Absolute contraindications | Relative contraindications |

|---|---|

| Perforated viscus | Atlantoaxial joint disease/severe cervical arthritis* |

| Esophageal pathology (stricture, trauma, tumor, scleroderma, Mallory-Weiss tear, diverticulum)$ | Prior chest radiation |

| Active upper GI bleeding | Symptomatic hiatal hernia |

| Recent upper GI surgery | History of GI surgery |

| Esophagectomy, Esophago-gastrectomy | Recent upper GI bleeding |

| Esophagitis, peptic ulcer disease | |

| Thoracoabdominal aneurysm | |

| Barrett’s esophagus | |

| History of dysphagia | |

| Coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia |

*With restricted cervical mobility. $TEE may be considered in patients with oral, esophageal, or gastric disease if expected benefit outweighs the potential risk provided appropriate cautions are applied. Suggested precautions may include: considering other imaging modalities (e.g., epicardial echocardiography), gastroenterology consultation, limited examination/avoiding unnecessary probe manipulation, using most experienced operator

A series of 14 patients[56] with known esophageal varices underwent TEE (excluding transgastric views) to evaluate infective endocarditis. TEE provided useful clinical information in all cases, with no major bleeding or other complications. A retrospective analysis of 396 liver transplant recipients (287 of whom had documented varices) revealed esophageal hemorrhage occurred in one patient (0.3%).[57] Another retrospective cohort[58] including 116 patients (of these, TEE was used in 114 for standard intraoperative monitoring and as a rescue intervention in 2) found that two (1.7%) patients experienced a complication. An additional cohort study[59] including 906 liver transplant patients (656 with a model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) >24) examined complications in patients where TEE was or was not used. TEE monitoring was used in 433 patients (66%). One patient in the TEE group suffered a major complication in the form of a Mallory-Weiss tear. Eleven patients (evenly divided between TEE and no-TEE groups) required postoperative gastroenterology consultation. The incidence of gastrointestinal (GI) hemorrhage (bloody NG output >500 ml/24 hrs) was not significantly different between groups. The authors also suggest decreasing the risk of variceal rupture during intraoperative TEE use [Table 3]. Another retrospective cohort,[60] including all liver transplantations where TEE was used over a ten-year period (232 cases, 70% of whom had at least grade 1 varices) disclosed 1 variceal rupture (0.4%), which required intraoperative banding. Finally, a systematic review and meta-analysis on the incidence of variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis undergoing TEE were recently published by Odewole M.[61] The pooled incidence (n = 3015) of bleeding for liver transplantation patients was 0.97% (95% CI 0.23-2.05%, i2 = 75.3%). This was higher than bleeding events when TEE was performed in cirrhotic patients for indications other than intraoperative monitoring for liver transplantation (0.004% 0-0.34%, i2 = 8) but was still considered low overall. The incidence of bleeding was similar comparing patients with MELD >18 (0.43% CI 0-1.75%) versus <18 (0.08% CI 0-1.54%; P = 0.43) and patients who underwent preprocedural esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) (0.2% CI 0-0.9%) versus those who did not (1.11% CI 0.2-2.4%; P = 0.63). Another systematic review that assessed the safety and efficacy of TEE for noncardiac surgery, with TEE being used in 1912 of 3837 patients (3083 of whom were undergoing liver transplantation),[30] found serious TEE probe-related complications in about 1.7% of cases. Overall, there is good data to support the safety of TEE during liver transplantation. While the authors believe TEE is generally contraindicated in patients with grade 3 or actively-bleeding varices, we note that dire clinical exigence might necessitate its use. In these cases [Table 4], though we are unaware of evidence supporting this strategy, safety might be enhanced by limiting probe advancement strictly to the mid-esophagus and avoiding distal esophageal or gastric placement.

Table 3.

Suggested precautions to decrease the risk of variceal rupture during intraoperative TEE use in patients with esophageal varices[55,58]

| 1. TEE examinations should be performed by experienced operators (who have ideally completed training) with strict vigilance |

| 2. Preoperative gastroenterology consultation for contemporaneous (within 12 months) endoscopic assessment of variceal status and possible variceal banding (12% annual rate of progression of small varices) |

| 3. Perform TEE after correcting coagulopathies |

| 4. Use rigid laryngoscope-assisted probe insertion to reduce incidence of oropharyngeal mucosal injury and number of insertion attempts |

| 5. Abandon TEE examination if probe insertion or advancement is difficult |

| 6. Limit probe insertion to mid-esophageal level |

| 7. Avoid wide range of probe tip flexion and unnecessary probe manipulation |

| 8. Avoid manipulation in a fixed flexion position |

| 9. Use TEE probe with a temperature-control mechanism |

| 10. Place TEE in ‘freeze’ mode when not obtaining images |

| 11. Remove TEE probe as soon as possible to limit thermal and mechanical effects |

| 12. Ensure availability of interventional gastroenterology teams to provide emergency endoscopic treatment for variceal bleeding |

Table 4.

Suggested guide to decision to perform intraoperative TEE during OLT in patients with known esophageal varices* or portal hypertensive gastropathyΔ[98]

| Grading of esophageal varices* | Endoscopic findings | Risk assessment | Decision to perform TEE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 | Small, straight varices that disappear with insufflation | Expected minimal risk | Can perform comprehensive TEE exam with minimal probe manipulation |

| Grade 2 | Medium, tortuous varices that occupy less than one third of the esophageal lumen | Expected low-medium risk | Can perform comprehensive TEE exam with minimal probe manipulation |

| Grade 3 | Large, coiled-shaped varices that occupy more than one third of the esophageal lumen OR high-risk features (red wale sign, decompensated patient) | Expected moderate-high risk | Avoid TEE unless needed as rescue intervention Restrict probe placement to upper and mid-esophageal sites Ensure minimal manipulation |

*Esophageal varices are dilated submucosal distal esophageal veins connecting the portal and systemic circulations due to portal hypertension.[99] ΔPortal hypertensive gastropathy is a condition where the gastric mucosa becomes congested and friable with dilated and distended capillaries and bleeds easily on contact[100]

Evolution of TEE during OLT

Attitudes toward and utilization of TEE for orthotopic liver transplantation have evolved. TEE has been used in liver transplantation since the 1980’s.[5,6] While its use had been sporadic, its importance was becoming increasingly recognized. A 2008 survey[62] of representatives of 30 high-volume liver transplant centers in the USA, encompassing 217 anesthesiologists, revealed that 86% performed TEE in some or all liver transplantation cases. The majority acquired skills and experience in TEE informally, with only 12% of users having board certification and only 1 center having a policy related to credentialing requirements for TEE. Two years later, in joint practice guidelines by the ASA and SCA on perioperative TEE, 54% of expert consultants (n = 54) and 46% of ASA members (n = 779) believed that TEE ought to be used during liver transplantation, with 33% and 41% of each respective group being uncertain.[63] A 2013 web-based survey of members of the liver transplant anesthesia consortium (LTrAC), a consortium of liver transplant anesthesiologists (n = 60 institutions) disclosed that TEE was used more often at large centers (48%, 50 or more transplants per year) as compared to small transplant centers (30%, less than 50 transplants per year). TEE board certification was uncommon (7%) at all centers.[64] Most recently, a 2018 survey of directors of liver transplant anesthesia programs/their alternates were completed.[65] Of 111 adult liver transplant centers, 79 (71%) could be reached, 56 of whom provided complete responses. These respondents represented 63% of transplant patients in 2015. TEE certification seems to have increased in frequency, with at least 1 anesthesiologist at 54% of centers possessing advanced perioperative TEE certification (64% with basic) from the National Board of Echocardiography (NBE) and 20% of centers having 3 or more anesthesiologists with this certification. Concerning persons making use of TEE as an intraoperative monitor, 90% of centers reported that at least one team member used TEE during liver transplantation, 54% of centers reported that more than half of their team did so, and 37% of centers reported that all members of their team used TEE. Regarding frequency of utilization, 56% of centers noted it was used in more than half of all cases, and two-thirds of this group always used it. Five centers reported never using TEE. Of these centers, 4 (2 low-volume, 2 medium) felt it was unnecessary, and 1 (low-volume) lacked knowledge of how to do so. TEE utilization was largely unaffected by the presence of cardiac fellowship-trained transplant anesthesiologists. Contraindications were typically limited to those already-enumerated above. Most centers perform a limited echocardiographic examination, with only 10% consistently performing the entirety of the ASE comprehensive exam, 25% in more than half of their cases, and 37% in less than half. More than a quarter (27%) of centers never performed the comprehensive exam. Regarding the utility of information provided by TEE, nearly three-quarters (73%) of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that TEE in liver transplants provides information that changes clinical outcomes (16% were uncertain). However, 66% of respondents felt it changed the outcome 25% or less of the time. A large majority (84%) of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that TEE provides information that cannot be derived from other types of measurements. Opinion on minimum training requirements was broad, with most respondents finding on-the-job training (52%) or basic NBE certification (52%) appropriate. However, a specialized course in TEE for liver transplant (34%) or advanced certification (7%) was also suggested. Some (5.4%) respondents were unsure what training should be necessary. The Society for the Advancement of Transplant Anesthesia endorses a more rigorous approach, supporting recommendations from the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists that all anesthesiologists using TEE during liver transplant surgery complete formal training pathways lead to certification by the NBE.[52]

Opinions vary on whether TEE should be used routinely for all cases of orthotopic liver transplantation or only selectively. This was examined in an editorial series. Those in favor of its use made arguments[66] regarding the inadequacy of other monitors and the utility of intraoperative echocardiography. As to other monitors, authors cited the unreliability of central venous pressure (CVP) and the invasiveness of pulmonary artery catheter (PAC) placement, as well as factors that might affect the reliability of PAC-derived cardiac output measurements. However, PAC use might be of value in patients with known pulmonary hypertension. TEE was argued to be helpful given that it allowed the determination of adequacy of LV preload/hypovolemia, LV contractility, hyperdynamic LV function, and LV or RV dysfunction. They further cited its ability to disclose unusual but significant findings, such as pulmonary, cardiac, or caval thromboembolism, patent foramen ovale/intracardiac shunting, LVOTO, or Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Its utility in confirming catheter placement, pleural or pericardial effusion diagnosis, and hepatic blood flow post-anastomosis assessment is also mentioned.

Other authors[67] felt it would be used more appropriately as an additional monitor when strictly warranted. They based this opinion on several criteria. They argue that different levels of expertise, resources, and support would be available at different transplant centers. Information might be difficult or impossible to obtain, given the tediousness or impracticality of specific measurements or the inability to acquire particular views. TEE cannot be used in all patients and is impractical for postoperative intensive care unit (ICU) monitoring, particularly in an extubated patient. They argued it gives only snapshots of fluid status and myocardial performance rather than continuous information. They stress that experience and expertise are essential to extracting accurate information and caution that with relatively low numbers of board-certified practitioners, there is a real possibility for inappropriate interpretation and intervention. These latter points likely form the basis for the general opinion among surveyed transplant anesthesiologists that some degree of dedicated training in TEE is a critical component of its use. There is some evidence to support the utility of short, intensive review workshops to enhance physician facilities with TEE. A report[68] describes such a simulation-based study. Anesthesiologists (n = 17) underwent a 4-hour review course on TEE taught by fellowship-trained cardiac anesthesiologists with board certification in advanced perioperative TEE. It focused on the basic ASE perioperative TEE exam with added transgastric IVC and hepatic vein views. Self-reported results included improved didactic assessment knowledge and comfort level with image acquisition and interpretation. The authors believe that the use of TEE and PAC should be viewed as complimentary rather than competitive. Both are important hemodynamic monitors with distinct advantages and limitations over one another.

The role of TEE has expanded beyond the assessment of the heart alone. TEE has been used, for example, to verify the position of guidewires before large-bore catheter placement and diagnose the cause of intractable intraoperative hypoxemia (ascites-related pleural effusion with consequential atelectasis.[69,70]

Liver transplantation-focused TEE views

As an ideal protocol, we endorse the utilization of the comprehensive TEE examination by those who are certified or otherwise facile with its performance and interpretation. However, given its technical complexity and the potentially prolonged period required for its conduction, more limited protocols are actively being evaluated for patient assessment during OLT. The ultimate determination on whether to utilize the comprehensive TEE assessment or a more limited protocol will likely depend on operator experience and clinical acuity. A recent TEE protocol for liver transplantation[71] included a comprehensive baseline examination during the dissection phase, followed by a more focused assessment during the anhepatic and neohepatic phases with labeling of images during different phases of the transplant. Their focus during the anhepatic phase was left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. During the neohepatic phase, they actively looked for RV dysfunction, intracardiac clots and systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve. Circumstances might dictate that an abbreviated protocol be followed. The authors here suggest such an assessment [Table 5]. An abbreviated, focused protocol may reduce the time otherwise required to obtain all 28 views for the presence of critical TEE findings.[72] This retrospective study recently demonstrated that a focused protocol diagnosed prespecified causes of hypotension during liver transplantation in 92% of occurrences. Their views included the mid-esophageal (ME) 4 chamber view, ME long axis view, ME bicaval view, ME right ventricular inflow-outflow view, and the non-standard inferior vena cava (IVC)/hepatic vein view. Previous papers have published perioperative TEE protocols with limited views for the non-cardiac surgery.[29,73] They demonstrated that 72.9% of rescue examinations resulted in a change in management, supporting the use of TEE as a diagnostic tool during hemodynamic compromise.[73] However, critical events during a liver transplant may be specific to the pathology of end-stage liver disease or the surgical procedure itself. Some pathologies specific to advanced liver disease may not be diagnosed preoperatively. In hepatopulmonary syndrome, substantial dilatation of capillary and precapillary vessels leads to formation of intrapulmonary shunts.[74] TEE can distinguish intracardiac shunts from these intrapulmonary shunts by imaging the source and the timing of microbubbles arriving into the left atrium (across the interatrial septum versus via the pulmonary veins), thus diagnosing potential hepatopulmonary syndrome.[75] This may be useful when hypoxia is unresponsive to treatment and may indicate the need for prolonged ventilation after a liver transplant until closure of these intrapulmonary shunts.

Table 5.

Suggested abbreviated protocol for TEE during OLT. Transgastric views may be omitted in the case of patients with known or high-risk varices[24]

| TEE views | Indication/Diagnosis evaluated |

|---|---|

| Mid-esophageal 4-chamber | RV/LV dysfunction |

| Diastolic dysfunction (E/A or tissue Doppler assessment of E/e’) | |

| Mid-esophageal 2-chamber | LV function |

| Mitral valve pathology | |

| Doppler assessment through Pulmonary vein | |

| Mid-esophageal bicaval | PFO/Atrial septal defect |

| Bubble test for hepatopulmonary syndrome | |

| Mid-esophageal modified bicaval | Tricuspid regurgitation (CWD) |

| Calculate RVSP/PAP in case of PoPH or during reperfusion | |

| Mid-esophageal RV inflow-outflow | RV function |

| Mid-esophageal aortic valve short axis | Aortic valve pathology (stenosis/regurgitation) |

| Mid-esophageal LV long-axis | Systolic anterior motion of mitral valve/LVOTO |

| LVOT dimension (component of calculation of cardiac output) | |

| Mid-esophageal ascending aortic short axis | Pulmonary embolism |

| Main pulmonary artery dimension (component of calculation of cardiac output) | |

| Cardiac output (PWD through main pulmonary artery) | |

| Transgastric mid-papillary | Hypovolemia |

| Myocardial ischemia (regional wall motion abnormalities) | |

| Hepatic venous drainage to IVC (modification with clockwise rotation and Omniplane 40° and 60°) | |

| Deep transgastric | Cardiac output (PWD through LVOT) |

RV=right ventricle, LV=left ventricle, PFO=patent foramen ovale, CWD=continuous wave doppler, RVSP=right ventricular systolic pressure, PAP=pulmonary artery pressure, PoPH=portopulmonary hypertension, LVOT=left ventricular outflow tract, LVOTO=left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, IVC=inferior vena cava, PWD=pulsed wave Doppler

Non-standard TEE views may be used to assess the portal and hepatic veins. Turbulent flow or high velocities through these vessels may occur with obstruction or kinking and lead to graft dysfunction; this can be detected with TEE.[76] A TEE examination of the liver can be performed at the edge of the TEE transgastric view at 0 degrees; the probe is then rotated clockwise. Setting the phasic array signal emitted by the transducer to between 40° and 60° will generate a basic hepatic view.[77] A ME bicaval view with an Omni-plane angle of 40°-70° can be obtained to visualize the IVC and then advancing the probe 2-3 cm. Varying the angle at this position (50-130°) will allow for visualization of the right, middle, and left hepatic veins.[78] Meierhenric et al. identified the three main hepatic veins in their studied patients. They reported adequate Doppler tracings of the right and middle hepatic veins were achieved more easily than of the left hepatic vein.[79] For the left hepatic vein Doppler, the angle of insonation was more than 60 degrees, and there were artifacts caused by heart motion transmitted to the left lobe of the liver.

Normal portal vein flows (PVF) present with gentle undulations on Doppler assessment, and high portal vein pulsatility is present in arterio-portal shunting, right heart failure, and tricuspid regurgitation.[80] In cardiac surgery, a high portal pulsatility fraction (50%) was shown to be associated with RV dysfunction, leading to venous hypertension and low systemic perfusion, consequently increasing postoperative complications.[81] Also, portal flow pulsatility can predict liver function test abnormalities in patients with congestive heart failure.[82] The evaluation of PVF using Doppler ultrasound can represent a simple method to assess hepatic congestion resulting from hypervolemia and/or right heart failure in patients undergoing OLT and has further potential to allow earlier identification of patients prone to allograft dysfunction. To obtain an image of PVF using TEE, a view of IVC is obtained using a lower ME view with the omni plane transducer at 90°. The TEE probe is then slowly advanced to a transgastric position while maintaining the liver under the ultrasound beam. Multiplane angle rotation between 50° and 70° will typically align the right portal vein with the center of the ultrasound beam.[83] In a recent case report, authors describe using TEE to visualize portal venous inflow to the liver after a living donor liver transplant.[84] They first used transgastric views to visualize the hepatic vein and, advancing further, described the portal vein as a vessel with a thick echo-dense wall. Portal vein flow velocity is usually 10-20 cm/sec in patients with portal hypertension.[82]

Everyday situations highlighting the utility of TEE

In the authors’ experience, TEE has been an invaluable tool to rapidly diagnose the causes of sudden and severe hemodynamic instability, as well as to guide its management. We have routinely performed TEE during all OLTs (excluding patients with contraindications as described above) for almost 10 years; most of our transplant anesthesiologists have advanced certification in perioperative TEE by the NBE.

-

Though SAM of the anterior mitral leaflet with LVOTO is commonly seen in structurally predisposed hearts, this can occur during relative hypovolemia and in the presence of hyperdynamic circulation in a structurally normal heart. LVOTO increases the incidence of perioperative cardiac arrest and requires significantly higher doses of vasopressors and intravenous fluids.[85] However, if LVOTO occurs due to an underfilled left ventricle from a failing right ventricle, the treatment focuses on RV support to promote forward flow to the left side of heart.[86]

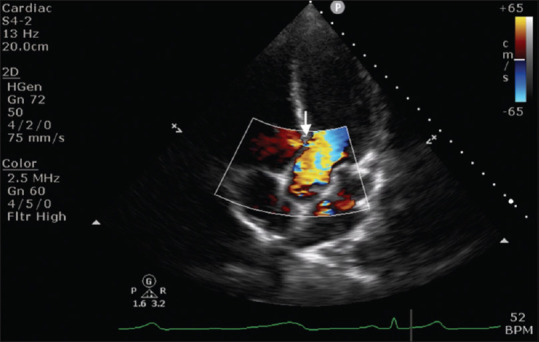

The authors encountered refractory hypotension during the anhepatic phase, where TEE revealed SAM causing LVOT obstruction with moderate mitral regurgitation [Figures 1 and 2]. The patient did not respond to usual volume resuscitation and vasopressors. Treatment with beta-blockers prompted sudden hemodynamic improvement. Thus, TEE helped in not only diagnosing the cause of intractable hypotension but also assisted management by allowing observation of improvement in real time.

Intracardiac thrombosis (ICT) is a known complication during OLT with a reported incidence of 0.36%-6.2%.[43,44,87] Intraoperative risk factors associated with its development are hemodialysis, previous TIPS or portocaval shunt surgery, pre-existing venous thrombosis, antifibrinolytic use, or atrial fibrillation.[44,87] It can occur both during the pre-anhepatic phase and the reperfusion phase.[44] The origin of the thrombi remains a matter of debate. They might originate from the superior vena cava (SVC) or IVC, PAC, or due to IVC clamping.[88] The clinical presentation of ICT during OLT includes a sudden increase in pulmonary artery pressure, systemic hypotension, and cardiac arrest. A retrospective cohort study suggests intravenous heparin before clamping may be protective against ICT,[87] and case reports document the successful use of low-dose tPA as treatment.[89] The authors had a case of intracardiac thrombosis in a patient with acute liver failure undergoing OLT. TEE demonstrated a clot from IVC extending into the right atrium [Figure 3], which was treated with alteplase. Despite a difficult postoperative course, the patient ultimately survived to discharge home. Though traditionally underreported, the incidence of detected intracardiac thrombus may increase due to the routine use of intraoperative TEE in many centers. Routine intraoperative TEE might lead to better detection than selective use, which could allow underdiagnosis and potentially delays time-sensitive treatment. In another retrospective study, incidence of ICT was 25% in patients undergoing multi-visceral transplantation.[90] Apart from diagnosing ICT, TEE also helps monitor the response to treatment, such as decreasing clot size and improving recovery of ventricular function.[91]

-

Miscellaneous cardiac lesions: it is not uncommon for the patient to suffer from cardiac lesions, which can only be diagnosed by perioperative echocardiography.

- Membranous ventricular septal defect (VSD): The authors diagnosed a small membranous VSD with a left-to-right shunt by a transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) in the immediate preoperative period[92] [Figure 4]. With intra-operative TEE, precautions were taken to prevent reversal of flow through the shunt. During the reperfusion phase, the left-to-right gradient decreased (but did not reverse), putting the patient at a slight risk for paradoxical embolism. With the help of intraoperative TEE, we performed hemodynamic calculations to measure gradients across the VSD during the reperfusion phase and modify our management. Air and debris from reperfusion in the right heart chambers could also be demonstrated.

- Aortic valve vegetation: The author diagnosed a case of vegetations on the aortic valve along with moderate to severe aortic incompetence [Figures 5 and 6] and moderate mitral regurgitation in a patient with unanticipated severe pulmonary hypertension diagnosed intraoperatively.[93] Pulmonary hypertension, in this case, had all three components—pre-capillary (high cardiac output and anemia), capillary (PoPH), and post-capillary (due to left heart failure and fluid overload). The donor surgery was halted, and an emergency multidisciplinary discussion took place. Pulmonary hypertension was managed with the help of diuretics and milrinone, and liver transplant was successfully carried out with continuous monitoring with both PAC and the TEE. The patient was discharged and was advised for aortic valve replacement.

Figure 1.

Midesophageal (ME) 4-chamber view: 2D image captured during anhepatic phase demonstrating systolic anterior motion of anterior mitral leaflet (SAM) causing with dynamic left ventricle outflow tract obstruction (LVOTO) mitral leaflet coaptation defect

Figure 2.

ME 4-chamber view: color Doppler image captured during anhepatic phase demonstrating flow acceleration across LVOT and posteriorly directed moderate mitral regurgitation jet

Figure 3.

ME right ventricle inflow-outflow tract view during reperfusion demonstrating intracardiac thrombus in the IVC extending into the right atrium

Figure 4.

Transthoracic apical 4-chamber view demonstrating a peri-membranous ventricular septal defect with a left to right shunt

Figure 5.

ME aortic valve long-axis view with intraoperative color Doppler showing diastolic regurgitant flow acceleration across the aortic valve in a recipient undergoing living related liver transplant

Figure 6.

ME descending thoracic aorta long-axis view of the same patient from Figure 5. Spectral Doppler waveform reveals holo-diastolic flow reversal, suggesting significant aortic incompetence

Future directions for TEE during OLT

A case report[94] described using nonstandard TEE views to evaluate hepatic vasculature and guide surgical management during OLT. The authors demonstrated supra-hepatic IVC anastomotic stenosis and a thrombus in the hepatic vein and IVC. This led to outflow obstruction and allograft congestion with hemodynamic instability. This important information led to the hepatic vein and IVC thrombectomy with anastomosis revision. In another case report,[95] De Marchi and colleagues described donor-recipient cavo-caval mismatch and stricture diagnosed by TEE. This prompted the revision of the anastomosis and relief of graft congestion. Studies examining the utility of TEE to evaluate graft hemodynamics and provide postoperative prognostication are ongoing. A recently published prospective trial[96] used TEE imaging of graft hepatic venous flow to show decreased flow correlated with increased risk of death, acute rejection, prolonged operative time, and delayed graft function. A prospective cohort[97] tracked e’, a marker of diastolic function, in 40 patients undergoing OLT and found lower values correlated with increased incidence of postoperative cardiorespiratory complications. Recently, Tempe et al. have also described views for interrogating portal venous flow patterns during OLT.[84]

CONCLUSION

TEE is increasingly becoming a routinely utilized monitor during OLT in patients without contraindications to its use, besides providing a wealth of information on baseline cardiac function. It also allows for the determination of cardiac responsiveness with progression of surgery. An increasing evidence base supports its utility in diagnosing and managing critical perioperative events, particularly during reperfusion. While the comprehensive echocardiographic examination might provide robust and detailed information, more limited and pragmatic evaluations elicit key information for optimal patient care during the perioperative management of patients undergoing liver transplantation. Future studies utilizing TEE will facilitate such disparate goals as optimizing examination safety, quality, and efficiency, permitting patient risk-stratification, and providing intra-operative guidance and evaluation of graft vasculature.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.All-time records again set in 2021 for organ transplants, organ donation from deceased donors-OPTN [Internet] [Last accessed on 2022 Oct 17]. Available from:https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/news/all-time-records-again-set-in-2021-for-organ-transplants-organ-donation-from-deceased-donors/

- 2.Burtenshaw AJ, Isaac JL. The role of trans-oesophageal echocardiography for perioperative cardiovascular monitoring during orthotopic liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:1577–83. doi: 10.1002/lt.20929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adelmann D, Kronish K, Ramsay MA. Anesthesia for liver transplantation. Anesthesiol Clini. 2017;35:491–508. doi: 10.1016/j.anclin.2017.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gold AK, Patel PA, Lane-Fall M, Gutsche JT, Lauter D, Zhou E, et al. Cardiovascular collapse during liver transplantation-echocardiographic-guided hemodynamic rescue and perioperative management. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2018;32:2409–16. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2018.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ellis JE, Lichtor JL, Feinstein SB, Chung MR, Polk SL, Broelsch C, et al. Right heart dysfunction, pulmonary embolism, and paradoxical embolization during liver transplantation. A transesophageal two-dimensional echocardiographic study. Anesth Analg. 1989;68:777–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Wolf A. Transesophageal echocardiography and orthotopic liver transplantation: General concepts. Liver Transpl Surg. 1999;5:339–40. doi: 10.1002/lt.500050408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin P, DiMartini A, Feng S, Brown R, Jr, Fallon M. Evaluation for liver transplantation in adults:2013 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the American Society of Transplantation. Hepatology. 2014;59:1144–65. doi: 10.1002/hep.26972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garg A, Armstrong WF. Echocardiography in liver transplant candidates. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:105–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chahal D, Liu H, Shamatutu C, Sidhu H, Lee SS, Marquez V. Review article: Comprehensive analysis of cirrhotic cardiomyopathy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021;53:985–98. doi: 10.1111/apt.16305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zardi EM, Abbate A, Zardi DM, Dobrina A, Margiotta D, Van Tassell BW, et al. Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:539–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.12.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zardi EM, Zardi DM, Chin D, Sonnino C, Dobrina A, Abbate A. Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy in the pre- and post-liver transplantation phase. J Cardiol. 2016;67:125–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2015.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bodys-Pełka A, Kusztal M, Raszeja-Wyszomirska J, Główczyńska R, Grabowski M. What's new in cirrhotic cardiomyopathy?-Review article. J Pers Med. 2021;11:1285. doi: 10.3390/jpm11121285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chayanupatkul M, Liangpunsakul S. Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy: Review of pathophysiology and treatment. Hepatol Int. 2014;8:308–15. doi: 10.1007/s12072-014-9531-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Izzy M, VanWagner LB, Lin G, Altieri M, Findlay JY, Oh JK, et al. Redefining cirrhotic cardiomyopathy for the modern era. Hepatology. 2020;71:334–45. doi: 10.1002/hep.30875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krowka MJ, Fallon MB, Kawut SM, Fuhrmann V, Heimbach JK, Ramsay MAE, et al. International liver transplant society practice guidelines: Diagnosis and management of hepatopulmonary syndrome and portopulmonary hypertension. Transplantation. 2016;100:1440–52. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krowka MJ. Hepatopulmonary syndrome and portopulmonary hypertension: The pulmonary vascular enigmas of liver disease. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken) 2020;15(Suppl 1):S13–24. doi: 10.1002/cld.846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: An update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28:1–39.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rudski LG, Lai WW, Afilalo J, Hua L, Handschumacher MD, Chandrasekaran K, et al. Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults: A report from the American Society of Echocardiography endorsed by the European Association of Echocardiography, a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology, and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010;23:685–713. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2010.05.010. quiz 786-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Labus J, Uhlig C. Role of echocardiography for the perioperative assessment of the right ventricle. Curr Anesthesiol Rep. 2021;11:306–17. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang B, Shi Y, Liu J, Schroder PM, Deng S, Chen M, et al. The early outcomes of candidates with portopulmonary hypertension after liver transplantation. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18:79. doi: 10.1186/s12876-018-0797-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeMartino ES, Cartin-Ceba R, Findlay JY, Heimbach JK, Krowka MJ. Frequency and outcomes of patients with increased mean pulmonary artery pressure at the time of liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2017;101:101–6. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith NK, Zerillo J, Kim SJ, Efune GE, Wang C, Pai SL, et al. Intraoperative cardiac arrest during adult liver transplantation: Incidence and risk factor analysis from 7 academic centers in the United States. Anesth Analg. 2021;132:130–9. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fukazawa K, Pretto EA, Nishida S, Reyes JD, Gologorsky E. Factors associated with mortality within 24h of liver transplantation: An updated analysis of 65,308 adult liver transplant recipients between 2002 and 2013. J Clin Anesth. 2018;44:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2017.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reeves ST, Finley AC, Skubas NJ, Swaminathan M, Whitley WS, Glas KE, et al. Basic perioperative transesophageal echocardiography examination: A consensus statement of the American Society of Echocardiography and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2013;26:443–56. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2013.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hahn RT, Abraham T, Adams MS, Bruce CJ, Glas KE, Lang RM, et al. Guidelines for performing a comprehensive transesophageal echocardiographic examination: Recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2013;26:921–64. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hall TH, Dhir A. Anesthesia for liver transplantation. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2013;17:180–94. doi: 10.1177/1089253213481115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Pietri L, Mocchegiani F, Leuzzi C, Montalti R, Vivarelli M, Agnoletti V. Transoesophageal echocardiography during liver transplantation. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:2432–48. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i23.2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Porter TR, Shillcutt SK, Adams MS, Desjardins G, Glas KE, Olson JJ, et al. Guidelines for the use of echocardiography as a monitor for therapeutic intervention in adults: A report from the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28:40–56. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fayad A, Shillcutt SK. Perioperative transesophageal echocardiography for non-cardiac surgery. Can J Anaesth. 2018;65:381–98. doi: 10.1007/s12630-017-1017-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fayad A, Shillcutt S, Meineri M, Ruddy TD, Ansari MT. Comparative effectiveness and harms of intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography in noncardiac surgery: A systematic review. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2018;22:122–36. doi: 10.1177/1089253218756756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lim YC, Doblar DD, Frenette L, Fan PH, Poplawski S, Nanda NC. Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography in orthotopic liver transplantation in a patient with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Clin Anesth. 1995;7:245–9. doi: 10.1016/0952-8180(94)00049-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harley ID, Jones EF, Liu G, McCall PR, McNicol PL. Orthotopic liver transplantation in two patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Br J Anaesth. 1996;77:675–7. doi: 10.1093/bja/77.5.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cywinski JB, Argalious M, Marks TN, Parker BM. Dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in an orthotopic liver transplant recipient. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:692–5. doi: 10.1002/lt.20440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aniskevich S, Shine TS, Feinglass NG, Stapelfeldt WH. Dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction during liver transplantation: The role of transesophageal echocardiography. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2007;21:577–80. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chin JH, Kim YK, Choi DK, Shin WJ, Hwang GS. Aggravation of mitral regurgitation by calcium administration in a patient with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy during liver transplantation: A case report. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:1979–81. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.02.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Essandoh M, Otey AJ, Dalia A, Dewhirst E, Springer A, Henry M. Refractory hypotension after liver allograft reperfusion: A case of dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Front Med (Lausanne) 2016;3:3. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2016.00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hughes CG, Waldman JM, Barrios J, Robertson A. Postshunt hemochromatosis leading to cardiogenic shock in a patient presenting for orthotopic liver transplant: A case report. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:2000–2. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.02.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mandell MS, Seres T, Lindenfeld J, Biggins SW, Chascsa D, Ahlgren B, et al. Risk factors associated with acute heart failure during liver transplant surgery: A case control study. Transplantation. 2015;99:873–8. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eagle SS, Thompson A, Fong PP, Pretorius M, Deegan RJ, Hairr JW, et al. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy and coronary vasospasm during orthotopic liver transplantation: Separate entities or common mechanism? J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2010;24:629–32. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2009.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sharma A, Pagel PS, Bhatia A. Intraoperative iatrogenic acute pericardial tamponade: Use of rescue transesophageal echocardiography in a patient undergoing orthotopic liver transplantation. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2005;19:364–6. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gologorsky E, De Wolf AM, Scott V, Aggarwal S, Dishart M, Kang Y. Intracardiac thrombus formation and pulmonary thromboembolism immediately after graft reperfusion in 7 patients undergoing liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2001;7:783–9. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2001.26928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ellenberger C, Mentha G, Giostra E, Licker M. Cardiovascular collapse due to massive pulmonary thromboembolism during orthotopic liver transplantation. J Clin Anesth. 2006;18:367–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xia VW, Ho JK, Nourmand H, Wray C, Busuttil RW, Steadman RH. Incidental intracardiac thromboemboli during liver transplantation: Incidence, risk factors, and management. Liver Transpl. 2010;16:1421–7. doi: 10.1002/lt.22182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peiris P, Pai SL, Aniskevich S, 3rd, Crawford CC, Torp KD, Ladlie BL, et al. Intracardiac thrombosis during liver transplant: A 17-year single-institution study. Liver Transpl. 2015;21:1280–5. doi: 10.1002/lt.24161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim S, DeMaria S, Jr, Cohen E, Silvay G, Zerillo J. Prolonged intraoperative cardiac resuscitation complicated by intracardiac thrombus in a patient undergoing orthotopic liver transplantation. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2016;20:246–51. doi: 10.1177/1089253216652223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dalia AA, Khan H, Flores AS. Intraoperative diagnosis of intracardiac thrombus during orthotopic liver transplantation with transesophageal echocardiography: A case series and literature review. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2017;21:245–51. doi: 10.1177/1089253216677966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aubuchon J, Maynard E, Lakshminarasimhachar A, Chapman W, Kangrga I. Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography reveals thrombotic stenosis of inferior vena cava during orthotopic liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2013;19:232–4. doi: 10.1002/lt.23576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vannucci A, Johnston J, Earl TM, Doyle M, Kangrga IM. Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography guides liver transplant surgery in a patient with thrombosed transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Anesthesiology. 2011;115:1389–91. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318223b8dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pissarra F, Oliveira A, Marcelino P. Transoesophageal echocardiography for monitoring liver surgery: Data from a pilot study. Cardiol Res Pract. 2012;2012:723418. doi: 10.1155/2012/723418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Suriani RJ, Cutrone A, Feierman D, Konstadt S. Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography during liver transplantation. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 1996;10:699–707. doi: 10.1016/S1053-0770(96)80193-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shillcutt SK, Ringenberg KJ, Chacon MM, Brakke TR, Montzingo CR, Lyden ER, et al. Liver transplantation: Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography findings and relationship to major postoperative adverse cardiac events. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2016;30:107–14. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.De Marchi L, Wang CJ, Skubas NJ, Kothari R, Zerillo J, Subramaniam K, et al. Safety and benefit of transesophageal echocardiography in liver transplant surgery: A position paper from the Society for the Advancement of Transplant Anesthesia (SATA) Liver Transpl. 2020;26:1019–29. doi: 10.1002/lt.25800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hilberath JN, Oakes DA, Shernan SK, Bulwer BE, D’Ambra MN, Eltzschig HK. Safety of transesophageal echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010;23:1115–27. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2010.08.013. quiz 1220-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Merli M, Nicolini G, Angeloni S, Rinaldi V, De Santis A, Merkel C, et al. Incidence and natural history of small esophageal varices in cirrhotic patients. J Hepatol. 2003;38:266–72. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(02)00420-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wigg AJ, Tashkent Y, Chen JW. Is transesophageal echocardiography really safe during liver transplant surgery in patients with high-risk varices? Liver Transpl. 2021;27:767–8. doi: 10.1002/lt.26037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Spier BJ, Larue SJ, Teelin TC, Leff JA, Swize LR, Borkan SH, et al. Review of complications in a series of patients with known gastro-esophageal varices undergoing transesophageal echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22:396–400. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Burger-Klepp U, Karatosic R, Thum M, Schwarzer R, Fuhrmann V, Hetz H, et al. Transesophageal echocardiography during orthotopic liver transplantation in patients with esophagoastric varices. Transplantation. 2012;94:192–6. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31825475c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Markin NW, Sharma A, Grant W, Shillcutt SK. The safety of transesophageal echocardiography in patients undergoing orthotopic liver transplantation. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2015;29:588–93. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2014.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Myo Bui CC, Worapot A, Xia W, Delgado L, Steadman RH, Busuttil RW, et al. Gastroesophageal and hemorrhagic complications associated with intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography in patients with model for end-stage liver disease score 25 or higher. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2015;29:594–7. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2014.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pai SL, Aniskevich S, 3rd, Feinglass NG, Ladlie BL, Crawford CC, Peiris P, et al. Complications related to intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography in liver transplantation. Springerplus. 2015;4:480. doi: 10.1186/s40064-015-1281-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Odewole M, Sen A, Okoruwa E, Lieber SR, Cotter TG, Nguyen AD, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: Incidence of variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis undergoing transesophageal echocardiography. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;55:1088–98. doi: 10.1111/apt.16860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wax DB, Torres A, Scher C, Leibowitz AB. Transesophageal echocardiography utilization in high-volume liver transplantation centers in the United States. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2008;22:811–3. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.American Society of Anesthesiologists and Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists Task Force on Transesophageal Echocardiography. Practice guidelines for perioperative transesophageal echocardiography. An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists Task Force on Transesophageal Echocardiography. Anesthesiology. 2010;112:1084–96. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181c51e90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schumann R, Mandell MS, Mercaldo N, Michaels D, Robertson A, Banerjee A, et al. Anesthesia for liver transplantation in United States academic centers: Intraoperative practice. J Clin Anesth. 2013;25:542–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2013.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zerillo J, Hill B, Kim S, DeMaria S, Mandell MS. Use, training, and opinions about effectiveness of transesophageal echocardiography in adult liver transplantation among anesthesiologists in the United States. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2018;22:137–45. doi: 10.1177/1089253217750754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Isaak RS, Kumar PA, Arora H. PRO: Transesophageal echocardiography should be routinely used for all liver transplant surgeries. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2017;31:2282–6. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2016.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cywinski JB, Maheshwari K. Con: Transesophageal echocardiography is not recommended as a routine monitor for patients undergoing liver transplantation. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2017;31:2287–9. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2016.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Christensen JM, Nelson JA, Klompas AM, Hofer RE, Findlay JY. The success of a simulation-based transesophageal echocardiography course for liver transplant anesthesiologists. J Educ Perioper Med. 2021;23:E672. doi: 10.46374/volxxiii_issue4_christensen. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vetrugno L, Barbariol F, Baccarani U, Forfori F, Volpicelli G, Della Rocca G. Transesophageal echocardiography in orthotopic liver transplantation: A comprehensive intraoperative monitoring tool. Crit Ultrasound J. 2017;9:15. doi: 10.1186/s13089-017-0067-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vetrugno L, Barnariol F, Bignami E, Centonze GD, De Flaviis A, Piccioni F, et al. Transesophageal ultrasonography during orthotopic liver transplantation: Show me more. Echocardiography. 2018;35:1204–15. doi: 10.1111/echo.14037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Berrio Valencia MI, Joschko A. Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiogram evaluation for liver transplantation. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2019;72:385–6. doi: 10.4097/kja.d.18.00331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vanneman MW, Dalia AA, Crowley JC, Luchette KR, Chitilian HV, Shelton KT. A focused transesophageal echocardiography protocol for intraoperative management during orthotopic liver transplantation. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2020;34:1824–32. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2020.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Staudt GE, Shelton K. Development of a rescue echocardiography protocol for noncardiac surgery patients. Anesth Analg. 2019;129:e37–40. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000003569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Weinfurtner K, Forde K. Hepatopulmonary syndrome and portopulmonary hypertension: Current status and implications for liver transplantation. Curr Hepatol Rep. 2020;19:174–85. doi: 10.1007/s11901-020-00532-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cosarderelioglu C, Cosar AM, Gurakar M, Dagher NN, Gurakar A. Hepatopulmonary syndrome and liver transplantation: A recent review of the literature. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2016;4:47–53. doi: 10.14218/JCTH.2015.00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bjerke RJ, Mieles LA, Borsky BJ, Todo S. The use of transesophageal ultrasonography for the diagnosis of inferior vena caval outflow obstruction during liver transplantation. Transplantation. 1992;54:939–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vetrugno L, Pompei L, Zearo E, Della Rocca G. Could transesophageal echocardiography be useful in selected cases during liver surgery resection? J Ultrasound. 2014;19:47–52. doi: 10.1007/s40477-014-0103-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cywinski JB, O’Hara JF., Jr Transesophageal echocardiography to redirect the intraoperative surgical approach for vena cava tumor resection. Anesth Analg. 2009;109:1413–5. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181b97788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Meierhenric R, Gauss A, Georgieff M, Schütz W. Use of multi-plane transoesophageal echocardiography in visualization of the main hepatic veins and acquisition of Doppler sonography curves. Comparison with the transabdominal approach. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:711–7. doi: 10.1093/bja/87.5.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Iranpour P, Lall C, Houshyar R, Helmy M, Yang A, Choi JI, et al. Altered Doppler flow patterns in cirrhosis patients: An overview. Ultrasonography. 2016;35:3–12. doi: 10.14366/usg.15020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Eljaiek R, Cavayas YA, Rodrigue E, Desjardins G, Lamarche Y, Toupin F, et al. High postoperative portal venous flow pulsatility indicates right ventricular dysfunction and predicts complications in cardiac surgery patients. Br J Anaesth. 2019;122:206–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2018.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Styczynski G, Milewska A, Marczewska M, Sobieraj P, Sobczynska M, Dabrowski M, et al. Echocardiographic correlates of abnormal liver tests in patients with exacerbation of chronic heart failure. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2016;29:132–9. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2015.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Denault AY, Azzam MA, Beaubien-Souligny W. Imaging portal venous flow to aid assessment of right ventricular dysfunction. Can J Anaesth. 2018;65:1260–1. doi: 10.1007/s12630-018-1125-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tempe DK, Sindwani G, Gupta S, Pamecha V, Mohapatra N, Arora MK. Transesophageal echocardiographic evaluation of the portal vein during living donor liver transplantation: A report of 3 patients. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2022;36((8 Pt B)):3152–5. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2022.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cailes B, Koshy AN, Gow P, Weinberg L, Srivastava P, Testro A, et al. Inducible left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in patients undergoing liver transplantation: Prevalence, predictors, and association with cardiovascular events. Transplantation. 2021;105:354–62. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000003245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dalia AA, Flores A, Chitilian H, Fitzsimons MG. A comprehensive review of transesophageal echocardiography during orthotopic liver transplantation. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2018;32:1815–24. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2018.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Groose MK, Aldred BN, Mezrich JD, Hammel LL. Risk factors for intracardiac thrombus during liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2019;25:1682–9. doi: 10.1002/lt.25498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Vetrugno L, Cherchi V, Lorenzin D, De Lorenzo F, Ventin M, Zanini V, et al. The challenging management of an intracardiac thrombus in a liver transplant patient at the reperfusion phase: A Case Report and Brief Literature Review. Transplant Direct. 2021;7:e746. doi: 10.1097/TXD.0000000000001200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Boone JD, Sherwani SS, Herborn JC, Patel KM, De Wolf AM. The successful use of low-dose recombinant tissue plasminogen activator for treatment of intracardiac/pulmonary thrombosis during liver transplantation. Anesth Analg. 2011;112:319–21. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31820472d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Raveh Y, Rodriguez Y, Pretto E, Souki F, Shatz V, Ashrafi B, et al. Thrombotic and hemorrhagic complications during visceral transplantation: Risk factors, and association with intraoperative disseminated intravascular coagulation-like thromboelastographic qualities: A single-center retrospective study. Transpl Int. 2018;31:1125–34. doi: 10.1111/tri.13281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Protin C, Bezinover D, Kadry Z, Verbeek T. Emergent management of intracardiac thrombosis during liver transplantation. Case Rep Transplant. 2016;2016:6268370. doi: 10.1155/2016/6268370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Desai TV, Dhir A, Quan D, Zamper R. Intraoperative management of liver transplant in a patient with an undiagnosed ventricular septal defect: A case report. World Journal of Anesthesiology. 2021;10:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sindwani G, Arora MK, Dhir A, Pamecha V. Unanticipated severe pulmonary hypertension in a patient undergoing living donor liver transplant - Role of milrinone and transesophageal echocardiography. Indian J Anaesth. 2021;65(Suppl 1):S53–5. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_833_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Khurmi N, Seman M, Gaitan B, Young S, Rosenfeld D, Giorgakis E, et al. Nontraditional use of TEE to evaluate hepatic vasculature and guide surgical management in orthotopic liver transplantation. Case Rep Transplant. 2019;2019:5293069. doi: 10.1155/2019/5293069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.De Marchi L, Lee J, Rawtani N, Nguyen V. Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiogram during orthotopic liver transplantation: TEE to the rescue!Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2018;22:146–9. doi: 10.1177/1089253218757032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Morita Y, Kariya T, Nagai S, Itani A, Isley M, Tanaka K. Hepatic vein flow index during orthotopic liver transplantation as a predictive factor for postoperative early allograft dysfunction. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2021;35:3275–82. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2020.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Devauchelle P, Schmitt Z, Bonnet A, Duperret S, Viale JP, Mabrut JY, et al. The evolution of diastolic function during liver transplantation. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2018;37:155–60. doi: 10.1016/j.accpm.2016.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Garcia-Tsao G, Abraldes JG, Berzigotti A, Bosch J. Portal hypertensive bleeding in cirrhosis: Risk stratification, diagnosis, and management:2016 practice guidance by the American Association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology. 2017;65:310–35. doi: 10.1002/hep.28906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Meseeha M, Attia M. StatPearls [Internet] Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022. [Last accessed on 2023 Feb 5]. Esophageal Varices. Available from:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448078/ [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wong F. Portal hypertensive gastropathy. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2007;3:428–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]