Abstract

Background

Massive rotator cuff tears (MRCT) account for a substantial fraction of tears above the age of 60 years. However, there are no clear criteria for prescription parameters within therapeutic exercise treatments. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects and characteristics of therapeutic exercise treatments in patients with MRCT.

Methods

A systematic search was conducted in MEDLINE/PubMed, Web of Science, SPORTDiscus, SciELO, Scopus and EMBASE from inception to August 2022. Studies were included if they evaluated the effects of exercise on patients with MRCT. The risk of bias was evaluated and the Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template (CERT) was also used. A narrative synthesis without meta-analysis was performed.

Results

One randomized controlled trial, two non-randomized studies, six non-controlled studies, one case series and four retrospective studies were included. They ranged from serious to moderate risk of bias. The CERT reflected a poor description of the exercise programmes. Studies showed a pattern of improvements in most patient-reported outcome measures (PROM) surpassing the MCID, and active elevation range of motion.

Conclusions

There is limited evidence that exercise and co-interventions are effective in the management of some patients with MRCT, based on a systematic review without meta-analysis. Future research should improve content reporting.

Level of evidence

IV.

Keywords: massive rotator cuff tear, shoulder, exercise, physical therapy, older adults

Introduction

Rotator cuff disease is the most common condition affecting the shoulder. The spectrum of disease can range from tendinopathy to chronic massive tears. Over 20% of the general population is expected to have a full-thickness rotator cuff tear (FRCT), and approximately 30% of them are symptomatic.1,2 Its prevalence increases with advancing age, and cuff tear size may also progress over time. Large size tears account for a substantial fraction of tears above the age of 60 years. 2 The largest tears are the massive rotator cuff tears (MRCT). There is no consensus regarding diagnostic criteria for MRCT. The two most commonly used criteria are a tear with a diameter greater than 5 cm or a tear involving two or more tendons. 3 Using these criteria, the reported prevalence in the literature has ranged from 10% to 40% of all rotator cuff tears. 4

Chronic MRCT treatment presents a challenge. They are injuries difficult to repair with surgery, and re-tears occur frequently. 3 Due to progressive fatty infiltration and atrophy of the associated muscles over time, tendon retraction, peritendinous adhesions and poor tissue quality, conventional rotator cuff repair to the footprint is often not possible. 5

Non-operative treatment is usually indicated as the first-line treatment for older adult patients with chronic irreparable rotator cuff tears or low functional demands, and also in those interested in conservative management or patients with comorbidities who are poor medical candidates for surgery.5,6

Conservative treatment includes therapeutic exercise, usually conducted under the guidance of a physical therapist, and pain management (education, medication, corticosteroid injections and local electro-thermal modalities such as transcutaneous nerve stimulation or heat…). The objectives of therapeutic exercise are to relieve stiffness and to strengthen the deltoid, the intact rotator cuff muscles and the periscapular musculature, leading to an improvement in pain and function. Furthermore, it has the advantage that it almost lacks from adverse effects, 7 even in patients with multimorbidity. 8 Various studies suggest that therapeutic exercise can significantly improve pain, function and active shoulder range of motion in patients with MRCT.5,6

There is a common problem in the musculoskeletal research field using therapeutic exercise, that is the poor description of the exercise programmes,9,10 which limits the interpretation and reproduction of studies and the capability of clinicians to implement research into clinical practice. 11 To resolve the issue of poor exercise treatment description, the Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template (CERT) was created, serving as a template for designing and evaluating the prescription of exercise interventions. 12

The aim of this systematic review is to describe the characteristics of the exercise-based programmes being used for the treatment of MRCT and to analyse their effectiveness regarding pain, active mobility and function.

Methods

Design

This systematic review was reported according to the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA). 13 The protocol of the review was registered prospectively at PROSPERO (CRD42020177100).

Search strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted in Medline/PubMed, Web of Science, SPORTDiscus, SciELO, Scopus and EMBASE databases from inception to March 2021 (Supplementary material 1). Furthermore, a hand-search of the references included in previously published systematic reviews and within included articles of this review was performed. The search was repeated again on 12 August 2022 after data extraction was completed to look for newly published studies.

Screening process

Two reviewers independently screened the title and abstract of the articles for their inclusion in the systematic review. The third reviewer resolved any discrepancies. The same process was performed for full-text screening. The whole screening process was conducted using the Covidence web application (Veritas Health Innovation Ltd, Melbourne, Australia).

The studies were included if they presented the following inclusion criteria: including patients with MRCT; presenting a design of a randomized controlled trial, non-randomized controlled trial, non-controlled trial, retrospective study or case series; presenting at least one group treated with conservative treatment including therapeutic exercise; reporting at least one outcome variable regarding pain intensity and/or shoulder function/disability measured with any kind of questionnaire.

The studies were excluded if they included only participants with non-MRCT or were case report studies. Publication year and language restrictions were not imposed.

Data extraction

Data extraction was conducted using a standardized form. The following data were extracted from each article: first author and year of publication, study design, sample characteristics, diagnostic criteria for MRCT, treatments descriptions, outcome measures descriptions and results of the study. Furthermore, the CERT 12 checklist was reported for each study. When some data was not present, the authors were contacted to retrieve the intended information.

Risk of bias

The internal validity of the randomized controlled trials was evaluated using Cochrane's RoB-2. 14 For non-randomized studies the ROBINS-I tool of the Cochrane Collaboration was used. 15 Finally, for non-controlled studies, retrospective studies and case series, risk of bias was not assessed.

Interpretation of the results

For each study, the change from baseline to each follow-up was analysed to determine whether it was greater than the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) reported for various shoulder patient-reported outcome measures (PROM). The MCID is defined as the difference between two repeated measures on the same participant which is expected to be interpreted as clinically meaningful for the patient. 16 Although this statistic is intended for individual patient data, it is commonly used to interpret the clinical relevance of mean differences within clinical trials. 16

The MCID has been reported for various shoulder-related disorders PROM. In recent years, two systematic reviews on this topic have been published.16,17 The estimated MCID for the Oxford Shoulder Score (OSS) ranges between 5 and 6.9 points 16 ; for the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons Standardized Shoulder Assessment Form (ASES) ranges between 6.4 and 21.9 points 16 ; for the Constant-Murley Score (CONSTANT) ranges between 8 and 10 points 17 ; for the University of California at Los Angeles Scale (UCLA) ranges between 2 and 8.7 points 17 ; for the Shoulder Rating Questionnaire of ĹInsalata (SRQ) ranges between 4 and 5 points 17 ; for the Subjective Shoulder Value (SSV) ranges between 12.1 and 26.6 points 17 ; for the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) ranges between 3.9 and 15 points 17 ; and for pain intensity measured with the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) ranges between 1.4 and 1.6 cm. 17 It couldn't be found the MCID for the Japanese Orthopaedic Association Score (JOA), the Measure Yourself Medical Outcome Profile (MYMOP), the 5-level EuroQol Questionnaire (5Q-5D-5L) and Short-Form 36 questionnaire (SF-36) for shoulder disorders. The results of different PROMS were interpreted as positive towards the effectiveness of therapeutic exercise with co-interventions, if they were statistically significant and surpassed the MCID, or if they were statistically significant in the case when no MCID was found.

Statistical analysis

Due to the high methodological heterogeneity between included studies, study designs and risk of bias, it was not possible to conduct a meta-analysis, so all the studies were analysed qualitatively. For continuous variables, the mean and 95% confidence interval (CI) were reported when available, otherwise data provided by the authors were reported. For categorical variables, the absolute frequencies and percentages were reported.

Results

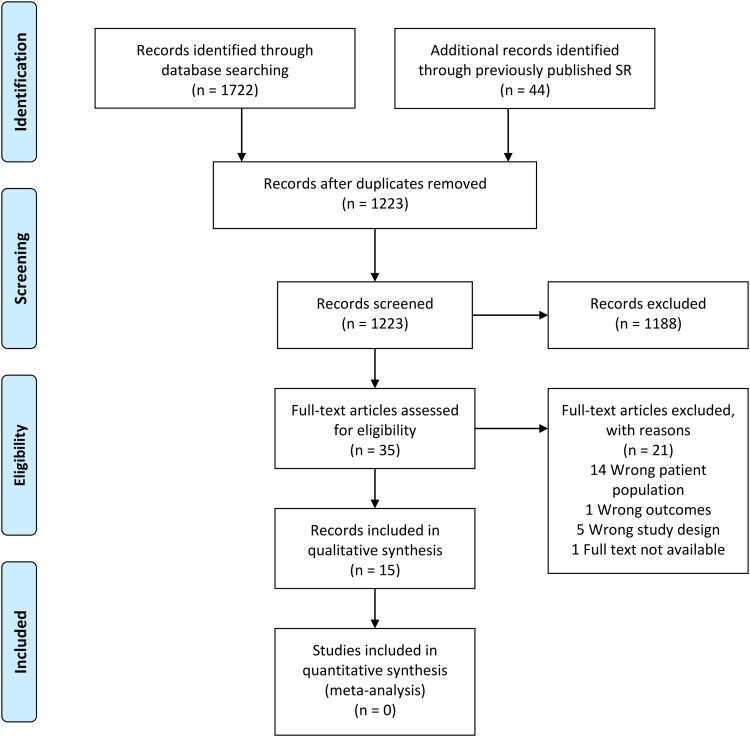

The literature search returned 1223 records after duplicates were removed (Figure 1). Finally, after the screening process, 15 records18–32 were included for qualitative analysis in the systematic review. One record 20 constituted a long-term follow-up of a previously published study. 32

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of included studies.

Characteristics of included studies and participants

Four articles had a retrospective design18,19,25,26 and 10 articles had a prospective design.20–24,27–32 The articles included 490 patients, being 239 women (48.78%, ranging from 33.33% to 80%), with a mean age ranging from 63.2 to 80 years, being equal or greater than 70 years in eight studies19,21,24,25,27–30 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics and drop-outs of included studies.

| Author, year | Design | Sample characteristics | Diagnostic criteria (imaging technique) | Treatment description (exercise programme and co-interventions) | Drop-outs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retrospective studies | |||||

| Vad et al. 2002 18 | Retrospective study | n: 40 (women not specified) Mean age: 63.2 |

- Tear greater than 5 cm - Tear of at least two tendons (MRI) |

Exercise programme: non specified Co-interventions: oral medication, steroid injections |

None |

| Yamada et al. 2000 19 | Retrospective study | n: 14 (5 women) Mean age: 70 (range: 55–81) |

- Tear greater than 5 cm - Hamada grade 4 (Arthrography) |

Exercise programme: passive and strengthening exercises Co-interventions: sling, steroids injections, heat |

None |

| Yildirim-Guzelant et al. 2014 25 | Retrospective study | n: 33 (14 women) Mean age: 71 (range: 50–84) |

- Tear of at least two tendons (MRI) |

Exercise programme: Rockwood exercise protocol Co-interventions: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs if necessary |

11 patients |

| Zingg et al. 2007 26 | Retrospective study | n: 19 (7 women) Mean age: 64 (range: 54–79) |

- Tear of at least two tendons (MRI) |

Exercise programme: passive and strengthening exercises Co-interventions: pain medication if necessary (systemic and local anti-inflammatory agents and steroid injections) |

21 patients |

| Prospective studies | |||||

| Ainsworth, 2006 27 | Non-controlled trial | n:10 (6 women) Mean age: 76 (range, 70–83) |

- Patte Stage 3 retraction (US) |

Exercise programme: Torbay exercise protocol Co-interventions: non specified |

None |

| Ainsworth et al. 2009 28 | Randomized controlled trial | n: 30 (16 women) Mean age: 78.4 (range, 65–96) |

- Tear greater than 5 cm. (US and/or MRI, non-specified) |

Exercise programme: Torbay exercise protocol Co-interventions: therapeutic ultrasound, advice, and steroid injection if necessary |

6 patients |

| Cavalier et al. 2018 29 | Non-randomized controlled trial | n: 71 (31 women) Mean age: 70 | - Tear of at least two tendons (MRI) |

Exercise programme: non specified Co-interventions: steroid injection |

None |

| Christensen et al. 2016 30 | Non-controlled trial | n: 30 (10 women) Mean age: 70.4 (range: 49–89) |

- Tear of at least two tendons (US, MRI) |

Exercise programme: strengthening exercises Co-interventions: non specified |

6 patients |

| Collin et al. 2015 31 | Non-controlled trial | n: 45 (28 women) Mean age: 67 (range: 56–76) |

- Tear of at least two tendons (US and/or MRI, non-specified) |

Exercise program: exercise aimed to relieve pain, to restore scapular mobility, to correct faulty humeral-head centring, to strengthen the intact muscles, and to improve scapular stability, proprioception, and movement automatism Co-interventions: non specified |

None |

| Gutiérrez-Espinoza et al. 2018, 202020,32 | Non-controlled trial | n: 96 (56 women) Mean age: 67.8 (SD: 5.7) | - Tear of at least two tendons (US, MRI) |

Exercise programme: exercises aimed to improve proprioception and normalize the scapular and glenohumeral resting position, scapular control exercises, and glenohumeral control exercises Co-interventions: manual physiotherapy |

None |

| Levy et al. 2008 21 |

Non-controlled trial | n:17 (11 women) Mean age: 80 (range: 70–96) |

- Tear of at least two tendons - Hamada grade ≥ 2 - Patte stage 3 retraction (Rx, US, MRI) |

Exercise programme: Reading Shoulder Unit exercise protocol Co-interventions: steroids injections, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or analgesic drugs if necessary |

None |

| Oyarzún et al. 2018 22 | Case series | n: 50 (32 women) Mean age: 68.3 (range: 60–75) | - Tear greater than 5 cm - Tear of at least two tendons (US or MRI) |

Exercise programme: Glenohumeral stabilization exercises Co-interventions: paracetamol if necessary, laterality training, and motor imaginary |

None |

| Veen et al. 2020 23 |

Non-randomized controlled trial | n: 5 (4 women) Mean age: 65 (range: 57–72) |

- Tear of at least two tendons - Patte stage 3 retraction (MRI) |

Exercise programme: exercises aimed to improve range, strength, and posture. Co-interventions: analgesic medication and steroid injections if necessary. |

None |

| Yian et al. 2017 24 |

Non-controlled trial | n: 30 (19 women) Mean age: 75 (range: 55–89) |

- Tear of at least two tendons - Patte stage 3 retraction (MRI) |

Exercise programme: Reading Shoulder Unit protocol Co-interventions: steroid injection and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory or pain drugs if necessary |

12 patients |

MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; n, number of patients; Rx, plain radiography; SD, standard deviation; US, ultrasonography.

Diagnostic criteria for MRCT

All the included studies used some kind of diagnostic imaging procedures: arthrography, 19 magnetic resonance imaging,18,20–26,30,32 ultrasound imaging20–22,27,32 and plain radiography.20,32 Some of the studies used a criterion of a tear involving at least two tendons,20,21,23–26,29–32 other used a criterion of a tear measuring 5 cm or longer,19,28 and other both criteria.18,22 One study used stage 3 Patte retraction as unique criteria. 27 Finally, some authors also included a criterion based on stage 3 Patte retraction,21,23,24,27 and Hamada grade greater than grade 2 19 or grade 4. 21

Regarding muscle's teared, supraspinatus and infraspinatus involvement was reported in eight studies19,20,23,25,26,29–32; supraspinatus and superior subscapularis involvement was reported in three studies20,29,31,32; supraspinatus and full subscapularis involvement was reported in three studies20,26,31,32; supraspinatus, infraspinatus and subscapularis involvement was reported in six studies20,21,25,26,30–32; and finally, supraspinatus, infraspinatus and teres minor involvement was reported in three studies.20,29,31,32

Risk of bias

The risk of bias is presented in Tables 2 and 3, and the ratings for each item of RoB-2 and ROBINS-I in Supplementary materials 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Outcomes for retrospective studies.

| Author, year | Follow-up | Variable | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vad et al. 2002 18 | 3.2 years (range: 2–7 years) | SRQ | Mean difference Exercise: 26.1; p < .05 Arthroscopic debridement: 39.1; p < .05 Repair: 50.6; p < .05 Between group different are statistically significant. |

| ROM | Active abduction: Mean difference Exercise: 40°; p < .05 Arthroscopic debridement: 36°; p < .05 Repair: 44°; p < .05 Between group differences not statistically significant. |

||

| Yamada et al. 2000 19 |

48 months (range: 12 months–19 years) | JOA | Mean difference Exercise: 17.85 (range: −10 to 32); p = .002 Surgery: 27.12 (range: 19–53); p < .001 Between-group differences are statistically significant. |

| Yildirim-Guzelant et al. 2014 25 | Not reported | ASES | Mean difference, 61.3; p = .022 |

| UCLA | Mean difference, 15; p = .031 | ||

| VAS | Mean difference, 5 cm; p = .031 | ||

| ROM | Active flexion: Mean difference, 55°; p = .027 Active external rotation: Mean difference, 3°; p > .05 |

||

| Strength | Post-treatment: Infraspinatus: Median, 3 (p > .05) Supraspinatus: Median, 3 (p > .05) Deltoid: Median, 4 (p = .04) |

||

| Zingg et al. 2007 26 | 48 months (range: 30–65 months) | CONSTANT | Post-treatment mean value, 69 (range: 41–94) |

| ROM | Flexion: Mean difference, 24°; p = .047 Abduction: Mean difference, 21°; p = .07 Internal rotation: Mean difference, −9°; p = .054 External rotation: Mean difference, −1°; p = .86 |

ASES, American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons Standardized Shoulder Assessment Form; CONSTANT, Constant-Murley Score; JOA, Japanese Orthopaedic Association Score; ROM, range of motion; SRQ, Shoulder Raging Questionnaire of ĹInsalata; UCLA, University of California at Los Angeles Scale; VAS, visual analogue scale.

Table 3.

Outcomes for prospective studies.

| Author, year | Follow-up | Variable | Outcomes | Risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ainsworth, 2006 27 | 3 months | OSS | Mean difference, 10 (SD, 5.87) | - |

| SF-36 | Physical: Mean difference, 10 (SD, 31.62) Emotional: Mean difference, −23 (SD, 41.72) General: Mean difference, −9 (SD, 9.94) |

|||

| Ainsworth et al. 2009 28 | 3, 6 and 12 months | OSS | Mean difference (SD) 3 months: Exercise, 8.19 (4.64); Control, 3 (7.03) 6 months: Exercise, 9.42 (6.23); Control, 4.43 (7.23) 12 months: Exercise, 8.96 (5.30); Control, 6.27 (7.93) Between-group differences: 3 months: 5.19 (95% CI: 1.99 to 8.39) 6 months: 4.99 (95% CI,:1.34 to 8.64) 12 months: 2.69 (95% CI,: -1.10 to 6.48) |

Some concerns a |

| SF-36 | Overall, there was a trend toward a small improvement over time in all domains in both groups (not significant). | |||

| MYMOP | Mean difference (SD) 3 months: Exercise, 1.03 (0.88); Control, 0.46 (1.25) 6 months: Exercise, 1.27 (1.15); Control, 0.67 (1.07) 12 months: Exercise, 1.02 (1.11); Control, 1.08 (1.32) Between-group differences: 3 months: 0.57 (95% CI, -0.01 to 1.15) 6 months: 0.60 (95% CI, 0.01 to 1.20) 12 months: -0.06 (95% CI, -0.74 to 0.62) |

|||

| ROM | Passive external rotation: Mean difference 3 months: Exercise, 1.88°; Control, 5.36° 6 months: Exercise, 8.75°; Control, −3.7° 12 months: Exercise, 7.43°; Control, 4.4° Between-group differences: 3 months: −3.48°; p > .05 6 months: 12.45°; p = .02 12 months: 3.03°; p > .05 |

|||

| Cavalier et al. 2018 29 | 1 year | ASES | Mean difference Exercise, 23.6; p < .01. Tenotomy/tenodesis long head biceps, 29.4; p < .01. Partial repair, 43.9; p < .01. Latissimus dorsi transfer, 13.3; p < 01. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty, 32.2; p < .01. |

Serious b |

| CONSTANT | Exercise, 17; p < .01. Tenotomy/tenodesis long head biceps, 10; p = .048. Partial repair, 21; p < .01. Latissimus dorsi transfer, 18; p < .01. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty, 22; p < .01. | |||

| SSV | Exercise, 26%, p < .01. Tenotomy/tenodesis long head biceps, 22%; p < .01. Partial repair, 31%; p < .01. Latissimus dorsi transfer, 31%; p < .01. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty, 30%; p < .01. | |||

| ROM | Active flexion: Mean difference, 25°; p < .01 Passive external rotation: Mean difference, 1.9°; p = .42 Passive internal rotation: Mean difference, 1.6; p = .02 There were not clinically important between-group differences of surgery groups compared to exercise group. |

|||

| Christensen et al. 2016 30 | 3 and 5 months | OSS | 3 months: Mean difference, 8.2 (95% CI: 2.4 to 14.0) 5 months: Mean difference, 11.7 (95% CI: 8.7 to 16.6) |

- |

| EQ-5D-5L | EQ-5D index: 5 months: Post-treatment median, 0.76;

p = .009 EQ-5D VAS: 5 months: Post-treatment median, 80; p < .001 |

|||

| VAS | There was an improvement on VAS during abduction, flexion and external rotation movements (p < .01) at

5 months. There was an improvement on VAS during isometric flexion (p < .01) at 45° and 90°, internal (p < .01) and external rotation (p = .047), but not during isometric abduction (p = .66) at 5 months. |

|||

| ROM | 5 months: Abduction: Mean difference, 34.4 (95% CI: 11.6 to 57.2) Flexion: Mean difference, 1.4 (95% CI: −24.1 to 26.8) External rotation: Mean difference, 3.8 (95% CI: −4.7 to 12.4) |

|||

| Strength | 5 months: Abduction: Mean difference, 12.3 (95% CI: 3.4 to 21.3) Flexion 45°: Mean difference, 10.2 (95% CI: 0.8 to 19.6) Flexion 90°: Mean difference, 7.0 (95% CI: 0.00 to 14.0) Internal rotation: Mean difference, 9.0 (95% CI: −1.9 to 19.8) External rotation, post-treatment median, 24.9 (p = .36) |

|||

| Collin e al. 2015 31 |

2 years | CONSTANT | Mean difference, 13; p < .05 | - |

| ROM | Active flexion: Participants with more than 160° at post-treatment follow-up, 24 (53.33%) | |||

| Gutiérrez-Espinoza et al. 2018, 202020,32 | 3 and 12 months | CONSTANT | 3months: mean difference, 24.9 (95% CI: 22.1 to 27.8) 1 year: mean difference, 26.5 (95% CI: 23.5 to 29.5) |

- |

| DASH | 3 months: mean difference, 28.7 (95% CI: 25.9 to 31.4) 1 year: mean difference, 31.4 (95% CI: 28.5 to 34.3) |

|||

| VAS | 3 months: mean difference, 3.6 cm (95% CI: 3.4 cm to 3.8 cm) 1 year: mean difference, 3.9 cm (95% CI: 3.6 cm to 4.1 cm) |

|||

| Levy et al. 2008 21 | 9 months | CONSTANT | Mean difference, 37 | - |

| Oyarzún et al. 2018 22 | 6 weeks and 6 months | CONSTANT | 6 weeks: Mean difference, 25.43; p = .01 6 months: Mean difference, 24.38; p = .01 |

- |

| VAS | 6 weeks: Mean difference, 3.6 cm; p = .01 6 months: Mean difference, 2.4 cm; p = .01 |

|||

| ROM | Active flexion: 6 weeks: Mean difference, 40°; p = .01 6 months: Mean difference, 34.87°; p = .01 |

|||

| Veen et al. 2020 23 | 3, 6 and 12 months | CONSTANT | Mean difference 3 months: Exercise, 16.9; Surgery, −8.3 6 months: Exercise, 13; Surgery, 3.2 1 year: Exercise, 19.1; Surgery, 26.4 Between-group differences: 3 months: 25.2; p < .05 6 months: 9.8; p < .05 1 year: −7.3; p > .05 |

Moderate b |

| VAS | Mean difference 3 months: Exercise, −3.3 cm; Surgery, 11.3 cm; p < .05 6 months: Exercise, −2.2 cm; Surgery, −0.75cm; p > .05 1 year: Exercise, -3.4 cm; Surgery, -2.83cm; p > .05 |

|||

| Yian et al. 2017 24 |

9 and 24 months | ASES | 9 months: Mean difference, 26; p < .001 2 years: Mean difference, 23; p = .001 |

- |

| SSV | 9 months: Mean difference, 20%; p < .001 2 years: Mean difference, 15%; p = .01 |

|||

| VAS | 9 months: Mean difference, 3.4 cm; p < .001 2 years: Mean difference, 3 cm; p < .001 |

|||

| ROM | Active scaption: 9 months: Mean difference, 40°; p < .001 2 years: Mean difference, 28°; p = .01 |

|||

| Strength | Abduction: 9 months: Mean difference, 1 kg; p < .001 2 years: Mean difference, 0.8 kg; p = .03 |

Cochrane's risk-of-bias tool 2.

Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies – of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool of the Cochrane Collaboration.

ASES; American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons Standardized Shoulder Assessment Form; CI, confidence interval; CONSTANT, Constant-Murley Score; DASH, Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand; EQ-5D-5L, 5-level EuroQol Questionnaire; MYMOP; Measure Yourself Medical Outcome Profile; OSS, Oxford Shoulder Score; ROM, range of motion; SF-36, Short-Form 36 questionnaire; SSV, Subjective Shoulder Value; SD, standard deviation; VAS, visual analogue scale.

Therapeutic exercise programmes

The performed therapeutic exercise programme was described in detail in eight studies.21–25,27,28,30 The Torbay exercise programme was used in two studies,27,28 as well as the Reading Shoulder Unit exercise programme21,24 and the Rockwood protocol was used in one study. 25 The remaining three studies used their own individual programmes.22,23,30 A full description of each therapeutic exercise programme along with webpage resource links is provided in Supplementary material 4. Finally, the CERT checklist for each study is presented in Supplementary material 5.

Co-interventions to the exercise programmes

Only three studies reported no use of co-interventions.27,30,31 Most of the studies included some analgesic or anti-inflammatory oral drugs when the patient needed them.18,21–26,30 Injections of corticosteroids and local analgesic drugs were also widely reported within the included studies.18,19,21–24,26,28,29 Finally, other therapeutic co-interventions used were slings, 19 heat, 19 advice, 28 therapeutic ultrasound, 28 laterality training, 22 motor imagery 22 and manual physiotherapy.20,32

Drop-outs

There were no drop-outs from the therapeutic exercise group in nine of the included studies.18–23,27,29,31,32 In the remaining five studies, the percentage of drop-outs from the therapeutic exercise group ranged from 20%28,30 to 46.68%. 26 The reasons for drop-out are presented in Supplementary material 7.

Prescription parameters

The duration of the therapeutic exercise programmes ranged from 6 weeks 22 to 6 months, 25 with the majority of the studies during about 3 months.21,23,24,27,28

Most of the studies used a combination of sessions at the clinic along with home exercises,21,24,27,28,30 whereas in the studies of Veen et al. 23 and Oyarzún et al. 22 patients were only treated at the clinic with no specification of home exercises.

Regarding the frequency of home exercises, the Torbay Program studies27,28 used a frequency of three exercises to be completed two to three times per day, the Reading Shoulder Unit Program studies21,24 used a frequency of three to five sessions of exercise per day and Christensen et al. 30 used a frequency of two exercises to be completed four times per week.

Exercise progression was described in six studies (Supplementary material 7).21,23,24,27,28,30 The strategies for exercise progression varied widely, including changing posture during exercises from supine (less gravity effect) to sitting/standing (more gravity effect),21,24,27,28 adding external load,21,23,24,27,28,30 and increasing repetitions. 30 Finally, the decision rules used for exercise progression were: evidence of movement control and consistency performing the exercises,27,28 patient's confidence gains in controlling shoulder movement during the exercises,21,24 pain intensity during and after the exercises (whether or not the patient felt challenged during the exercises), 30 patient is able to perform 4 × 12 repetitions, 30 general pain control, 23 attaining normal or functional passive range of motion, 23 and progression each 2–3 weeks if exercises do not produce discomfort. 23

Targeted muscles within exercise programme

Although a wide variety of muscles are activated within the exercises included in the different protocols, the authors of 10 of the studies20–25,27,28,30–32 claimed to target some muscles within their therapeutic exercise programmes, being the most commonly reported the anterior deltoid,21–25,27,28,30,31 teres minor,23–25,27,28,30,31 medium deltoid,22,23,25,31 and serratus anterior20,22,25,31,32 muscles. The detailed list of focused muscles for each individual study is presented in Supplementary material 8.

PROM

Within the retrospective studies, there was a significant improvement greater than the MCID in ASES, and UCLA. 25 There was also an statistically significant improvement in the JOA 19 and SRQ. 18 Finally, Zingg et al. 26 only provided data about post-treatment scores in CONSTANT, without changes from baseline being reported (Table 2).

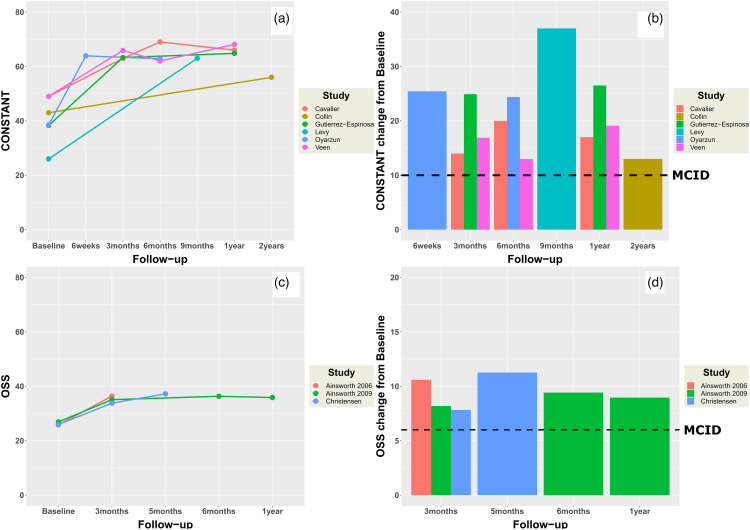

Regarding prospective studies, the improvements over time in CONSTANT20–23,29,31,32 and OSS27,28,30 were all greater than the MCID, and are presented in Figure 2. There were statistically significant improvements in SSV24,29 that were above the MCID cut-off point of 12.1 but below the cut-off point of 26.6. 17 There were also significant improvements greater than the MCID in ASES24,29 and DASH.20,32 Finally, there was a statistically significant improvement over time in MYMOP 28 and 5Q-5D-5L, 30 but not in SF-36 (Table 2).27,28

Figure 2.

Changes in Constant-Murley score (CONSTANT) and Oxford Shoulder Score (OSS) within prospective included studies. Line plots (a and c) represent raw values at each measurement point. Bar plots (b and d) represent changes from baseline to each follow-up. Dashed lines (bar plots b and d) represent the minimal clinically important difference (MCID), with a value of 6.9 points for OSS and a value of 10 points for CONSTANT.

Pain intensity

The study by Yildirim-Guzelant et al. 25 was the only retrospective study that measured pain intensity with VAS. They found a statistically significant improvement in VAS that was above the MCID (Table 2).

Regarding prospective studies, there was a significant improvement in pain intensity measured with VAS above MCID.20,22–24,32 Furthermore, there was a significant improvement above the MCID in VAS during active abduction, flexion and external rotation movements, 30 as well as during isometric testing in flexion at 45° and 90° and internal and external rotation (Table 3). 30

Range of motion

The retrospective studies showed a significant improvement in active abduction 26 and active flexion18,25,26 movements (Table 2).

The prospective studies showed significant improvement over time in passive external rotation in the study of Ainsworth et al. 28 from 2009, but not in the study of Cavalier et al. 29 They also found a significant improvement in active flexion,22,29,31 active scaption, 24 and passive internal rotation. 29 Finally, Christensen et al. 30 found a significant improvement in abduction, but not in external rotation and flexion. However, they did not report if the movement was performed passively or actively (Table 3).

Strength

Regarding retrospective studies, only the study published by Yildirim-Guzelant et al. 25 in 2014 assessed strength changes by manual examination. They found a significant improvement in deltoid strength, but not in supraspinatus and infraspinatus strength (Table 2).

Prospective studies showed a significant improvement in strength measured with a hand-held dynamometer in isometric abduction24,30 and isometric flexion at 45° and 90°, 30 but not in isometric internal and external rotations (Table 3). 30

Discussion

In this systematic review, 15 records including 490 patients were included, regarding therapeutic exercise with co-interventions (e.g. injections, pain killer…) treatment for MRCT. Overall, studies showed that patients with MRCT can be managed satisfactorily with non-operative treatment based mainly on exercises with co-interventions up to 2 years follow-up.

Currently, there are three well-known therapeutic exercise programmes for the approach of patients with MRCT: the Torbay Program,27,28 the Reading Shoulder Unit Program21,24 and the Rockwood Program. 25 (Supplementary material 4) The exercise programmes used within included studies were all based on improving the strength of the intact muscles. Furthermore, most of the studies used analgesic or anti-inflammatory oral drugs, and/or corticosteroid or analgesic injections as co-interventions if patients needed.18,19,21,23,24,26,28,29

Recently, Shepet et al. 33 have published another systematic review in this topic, with similar conclusions to the present review. They included only 10 articles, leaving out the studies of Ainsworth et al. 28 published in 2009, Yamada et al., 19 Yildirim-Guzelant et al., 25 Oyarzún et al., 22 Cavalier et al., 29 Gutiérrez-Espinoza et al. 20 and Veen et al. 23 On the other hand, they included the studies of Agout et al. 34 published in 2018 and Yoon et al. 35 published in 2019.

We did not include in the present review the study of Agout et al. 34 because they analysed non-operative patients as a whole, without distinguishing those treated only with physical therapy, those receiving only local steroid injections, and those receiving both treatments, thus making it impossible to know the effects of therapeutic exercise treatment with co-interventions.

Furthermore, we did not include the study of Yoon et al. 35 because they only included patients with few functional limitations (pain less than or equal to 3 cm in VAS, active forward elevation > 120°, and not having much difficulty performing activities of daily living), and because 50% of their patients converted to surgery, but only those who did not convert were measured at follow-up, hindering making conclusions about the effectiveness of the therapeutic exercise treatment.

Some authors have proposed that non-operative treatment for patients with MRCT is only indicated if the patient has no significant pain and/or functional limitations.5,35,36 The patients included in the studies of this systematic review had a wide variety of symptom severity, thus, such previous recommendations reported in the literature are not justified based on the results of this systematic review, as patients with greater pain severity and/or disability can also improve with a therapeutic exercise programme along with co-interventions focused on pain management.

Outcomes

Overall, there was a clinically significant improvement over time in function/disability measured with various PROM, pain intensity, active elevation range of motion and elevation strength within included studies. Only five studies included a comparator group, composed of passive modalities and corticosteroid injections 28 or surgical procedures.18,19,23,29 Comparator groups also showed a significant and clinically relevant improvement over time (Tables 2 and 3), and there were mixed results in between-group comparisons, with some studies showing statistically significant improvements in surgical comparator groups in some PROMs but not others (Tables 2 and 3). However, due to moderate-to-high risk of bias, especially treatment allocation bias, as most studies used different criteria for including subjects in the therapeutic exercise group or comparator group, definitive conclusions cannot be reached about which is the optimal treatment. Future research comparing surgical and therapeutic exercise approaches with adequate study designs and less bias is needed.

The improvements observed were mainly achieved within the first 3 to 6 months20,22,23,28–30,32 and seem to be maintained up to 2–3 years.18,19,24,26,31 Only one study measured improvements at a shorter follow-up (6 weeks), showing clinically and statistically significant improvements in function, pain and active flexion. The fact that all other studies measured outcomes from 3 months onwards could be because, based on our clinical experience, patients with MRCT seem to take a little bit longer to improve.

Therapeutic programmes

Therapeutic exercise has been widely investigated in the shoulder pathology literature, being recommended for the treatment of rotator cuff tendinopathy, 37 partial and FRCT, 38 shoulder instability 39 and superior labral anterior-posterior injuries. 40 In agreement with all these literatures, a previously published systematic review about the effectiveness of non-operative treatments for MRCT, 33 and based on the results of this systematic review, it seems exercise along with some anti-inflammatory/analgesic co-interventions when needed, is also a treatment option for some types of MRCT.

Despite some drop-outs were reported,24–26,28,30 which could represent a failure of the therapeutic exercise intervention in some patients, the reasons were mostly not-related to a failure of the therapeutic exercise treatment (e.g. person deceased, moving out from the city, or withdraw before treatment begun) (Supplementary material 6). This can imply that, overall, patients are comfortable with therapeutic exercise being an option for the treatment of their shoulder complaints.

Exercise prescription parameters considerations

There was a wide variety of different exercise prescription parameters within included studies, which do not allow us to draw definitive conclusions about which ones are the best ones. This issue has been clearly documented in musculoskeletal pain literature, such as in patients with rotator cuff tendinopathy, 41 patellar tendinopathy and/or patellofemoral pain. 42

In most of the studies, the exercise programmes lasted about 3 months.21,23,24,27,28 In patients with rotator cuff tendinopathy, some authors recommend that treatment should be changed if there is no significant improvement after 12 weeks of therapeutic exercise. 41 Furthermore, no improvement after 6–12 weeks of conservative treatment has been suggested to be a criteria for moving towards surgical treatment in patients with FRCT. 43 However, it is not clear the optimal treatment duration. 44 This lack of research into this topic is also present in MRCT, hindering drawing conclusions about the optimal treatment duration for MRCT.

Although many patients with MRCT seem to improve in function and pain intensity within the first 3 months, this does not imply the patients have achieved their maximum possible improvements, neither that all patients will improve within this time. In fact, although we have no data for patients with MRCT, natural history of patients with FRCT shows that these patients seem to improve over time, despite treatment provided, up to 24 months after treatment started, based on a systematic review focusing on randomized controlled trials. 45

One of the main goals of the therapeutic exercise programmes for patients with MRCT is the improvement of the strength within the intact muscles.3,33 Research regarding resistance training has shown that periods longer than 3 months are needed for a good improvement of muscle strength and morphology in healthy old adults, with a training period up to 50–53 weeks turning to be the most effective. 46 The studies that measured muscle strength24,30 did it at follow-up periods longer than 3 months, ranging from 5 months 30 to 2 years 24 within the prospective studies. Furthermore, all the studies18,24,26,29–31 except the one of Oyarzún et al. 22 measured active shoulder elevation range of motion also at longer follow-up periods than 3 months, ranging from 5 months 30 to 2 years.24,31 Thus, we cannot ensure that muscle strength neither active elevation will improve enough within the first 3 months, so it might be better to encourage patients to keep up with the exercises performed at home from 6 months to 1 year.

A combination of sessions at the clinic along with home exercises was the preferred option within the included studies.21,24,27,28,30 Research into this topic has shown that there seems to be no difference in terms of improvements in pain and disability between supervised and home-based exercise programmes in some shoulder populations such as patients with rotator cuff tendinopathy,41,47 and post-operative rotator cuff repair. 48

However, there are some barriers to the implementation of home-based exercise programmes. It is important that the patient understands his or her problem and to provide an explanation about the meaning of pain within the exercise performance, as some patients might not adhere to the exercise programme because of wrong beliefs that lead them not to trust this intervention.49,50 Another barrier might be equipment availability, 50 so it is important to provide the patients with adequate equipment and/or to use common objects of daily living for the performance of the exercises, so they don't have to buy them.

Some authors of the included studies used a frequency of home exercises from 2 to 5 times per day.21,24,27,28 There is no consensus in the literature regarding optimal frequency of exercise for musculoskeletal shoulder disorders, 41 and there is some research suggesting that more might not be better.41,42,51

Time availability at home is one of the barriers for the adherence of patients to home exercise programmes. 50 One of the objectives in treating people with MRCT is to improve the strength of intact muscles. It should be taken into account actual research regarding muscle strength training, which suggests that the overall weekly volume of training is more important than days per week,52–54 so patients may perform the exercises in multiple short-time training sessions along the week, instead of long-time sessions, making it easy to adapt the exercise routine to their available time.

Although exercise progression was described in six studies,21,23,24,27,28,30 the strategies employed varied widely and were poorly specified. Based on the results of this systematic review, it can be concluded that exercise progression based on increasing load seems to be important, but no conclusion can be drawn regarding the criteria for exercise progression.

Considerations for future research and clinical practice

After reviewing the current literature regarding exercise therapy treatment for MRCT, some aspects should be considered. Exercise programmes were poorly described even within the studies that described them the better.

Previously, Major et al. 11 showed a poor content reporting of exercise interventions in rotator cuff disease, and they recommend the CERT as a reliable tool for evaluating exercise treatments within clinical trials. Beyond the CERT usage recommendations and considering that strength training is the main type of exercise for the management of MRCT, we recommend reporting some minimal needs which allow replication of the employed interventions, adapted from Page et al., 55 Slade et al. 56 and Hecksteden et al. 57 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Recommendations for content reporting of exercise interventions.

| Contraction type | Isometric/isotonic concentric/isotonic eccentric, mixed |

| Load magnitude | |

| Intensity | RPE, %RM, RIR, execution velocity |

| Volume | Number of repetitions, number of sets, rest in-between sets |

| Schedule | Number of exercise interventions (per day or week) Duration of the experimental period (days or weeks) |

| Materials | Bands, free weights… |

| Pain free execution | YES/NO |

| Progression criteria | Pain improvement, disability improvement, patient preferences… |

| Provider | Expertise, background and any specific training given… |

| Range of motion | Complete, free of pain… |

| Setting | Home based, institutional, individual, group based, inpatient. |

| Supervision | Supervised/unsupervised/mixed |

RPE, rated perceived exertion; %RM, percentage of repetition maximum; RIR, repetitions in reserve.

Although many of the studies included participants with different patterns of teared muscles, none of them reported to take this into account when selecting the exercises for each patient, thus using the same programme for all participants. Despite no conclusion can be drawn from the results of this systematic review regarding which patterns of teared muscle seem to respond better to therapeutic exercise, we think that not taking it into account could lead to non-successful treatment because of the wrong selection of exercises (e.g. external rotation exercises for patients with tears involving both infraspinatus and teres minor muscles). Furthermore, some authors have suggested that MRCT involving subscapularis muscle could be a predictor of bad outcomes with non-operative treatment,31,35 although there are other ones suggesting no such association, 34 and no conclusion can be reached with the results of the present study.

We recommend to take into account the patterns of teared muscles, and to use the classification based on 5 components proposed by Collin et al. 58 in which subscapularis is divided into upper and lower parts, for reporting tear patterns in research and for selecting the adequate exercises for patients with MRCT.

Regarding frequency of sessions at the clinic, we recommend a model similar to the one employed by Ainsworth et al.27,28 starting with more frequency of sessions at the clinic (e.g. two sessions per week) and moving onwards to less frequency (e.g. one session per week) as the patient improves, up to a minimum of 3 months, based on patient's needs. After the initial 3 months, patient should be encouraged to continue performing the learned exercises for at least another 3 months, and one or two revision sessions at the clinic within this period should be recommendable to improve patient's adherence.

Exercise progression was poorly described in most of the included studies. Furthermore, the reported progression criteria were very subjective (e.g. patient has good control performing the exercises,27,28 and patient gains confidence in controlling shoulder movement during exercise21,24) (Supplementary material 7), hindering replication in both research and clinical fields. Objective criteria should be reported for exercise progression, as well as for exercise regression (i.e. criteria for knowing when to return to a previous level of exercise based on the worsening of the patient), even if these objective criteria are based on subjective scores (i.e. pain intensity and perceived exertion).

We also encourage to include patient's education (e.g. explanations about the relationship between shoulder pain and function and MRCT, the role of pain within the exercises…) within the physical therapy programme, to improve patient’s adherence and confidence within the prescribed exercises,49,50 since it seems to be a relationship between patient's expectations and conservative treatment outcomes.59–62

Analgesic and/or anti-inflammatory oral medication are recommended for pain management if patients need it, as pain intensity can also be one of the barriers to exercise adherence.49,50 Regarding injections, corticosteroid is widely used in included studies. Corticosteroids have been shown to produce a decrease in pain intensity in this and other shoulder pain populations, however, they have also been shown to have an adverse impact on rotator cuff tendon health and repair. 63 Suprascapular nerve block seems to be equally effective as corticosteroid injections in patients with chronic shoulder pain, without having a detrimental effect on tendon health. 64 Thus, we recommend future research to compare this procedure to corticosteroid injections, so we can discern which one is better for patients with MRCT.

Finally, therapeutic exercise treatment of patients with MRCT should be framed into a biopsychosocial model, considering it as a multidimensional intervention that can confer benefits through multiple biopsychosocial interrelated processes, not just simply by increasing strength or improving shoulder mechanics, 65 such as decreasing fear-avoidance beliefs or pain catastrophizing, inducing a general hypoalgesia response, or increasing mental wellbeing.

Limitations

Due to high methodological heterogeneity between included studies, no meta-analysis could be performed. Second, almost all of the included studies were non-randomized, non-controlled or retrospective studies. Third, the included studies had a moderate-to-serious risk of bias. And fourth, most studies used some co-interventions, which precludes drawing conclusions about the isolated effect of therapeutic exercise.

Future research into this topic should improve these aspects so we can be more confident about the effectiveness of exercise-based physical therapy treatment for patients with MRCT.

Conclusion

There is limited evidence that therapeutic exercise and co-interventions are effective in the management of some patients with MRCT, based on a systematic review without meta-analysis of non-randomized, non-controlled and retrospective studies. Despite several limitations within included studies, this treatment seems to be promising. Future research with greater content reporting quality should be conducted to improve our knowledge of this field and the clinical applicability.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-sel-10.1177_17585732221140113 for Content reporting and effectiveness of therapeutic exercise in the management of massive rotator cuff tears: A systematic review with 490 patients by Rubén Fernández-Matías, Fernando García-Pérez, Néstor Requejo-Salinas, Carlos Gavín-González, Javier Martínez-Martín, Homero García-Valencia and Mariano Tomás Flórez-García in Shoulder & Elbow

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-sel-10.1177_17585732221140113 for Content reporting and effectiveness of therapeutic exercise in the management of massive rotator cuff tears: A systematic review with 490 patients by Rubén Fernández-Matías, Fernando García-Pérez, Néstor Requejo-Salinas, Carlos Gavín-González, Javier Martínez-Martín, Homero García-Valencia and Mariano Tomás Flórez-García in Shoulder & Elbow

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-sel-10.1177_17585732221140113 for Content reporting and effectiveness of therapeutic exercise in the management of massive rotator cuff tears: A systematic review with 490 patients by Rubén Fernández-Matías, Fernando García-Pérez, Néstor Requejo-Salinas, Carlos Gavín-González, Javier Martínez-Martín, Homero García-Valencia and Mariano Tomás Flórez-García in Shoulder & Elbow

Supplemental material, sj-docx-4-sel-10.1177_17585732221140113 for Content reporting and effectiveness of therapeutic exercise in the management of massive rotator cuff tears: A systematic review with 490 patients by Rubén Fernández-Matías, Fernando García-Pérez, Néstor Requejo-Salinas, Carlos Gavín-González, Javier Martínez-Martín, Homero García-Valencia and Mariano Tomás Flórez-García in Shoulder & Elbow

Supplemental material, sj-docx-5-sel-10.1177_17585732221140113 for Content reporting and effectiveness of therapeutic exercise in the management of massive rotator cuff tears: A systematic review with 490 patients by Rubén Fernández-Matías, Fernando García-Pérez, Néstor Requejo-Salinas, Carlos Gavín-González, Javier Martínez-Martín, Homero García-Valencia and Mariano Tomás Flórez-García in Shoulder & Elbow

Supplemental material, sj-docx-6-sel-10.1177_17585732221140113 for Content reporting and effectiveness of therapeutic exercise in the management of massive rotator cuff tears: A systematic review with 490 patients by Rubén Fernández-Matías, Fernando García-Pérez, Néstor Requejo-Salinas, Carlos Gavín-González, Javier Martínez-Martín, Homero García-Valencia and Mariano Tomás Flórez-García in Shoulder & Elbow

Supplemental material, sj-docx-7-sel-10.1177_17585732221140113 for Content reporting and effectiveness of therapeutic exercise in the management of massive rotator cuff tears: A systematic review with 490 patients by Rubén Fernández-Matías, Fernando García-Pérez, Néstor Requejo-Salinas, Carlos Gavín-González, Javier Martínez-Martín, Homero García-Valencia and Mariano Tomás Flórez-García in Shoulder & Elbow

Supplemental material, sj-docx-8-sel-10.1177_17585732221140113 for Content reporting and effectiveness of therapeutic exercise in the management of massive rotator cuff tears: A systematic review with 490 patients by Rubén Fernández-Matías, Fernando García-Pérez, Néstor Requejo-Salinas, Carlos Gavín-González, Javier Martínez-Martín, Homero García-Valencia and Mariano Tomás Flórez-García in Shoulder & Elbow

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the people who supported them while conducting this research.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Rubén Fernández-Matías https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8365-7264

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Yamamoto A, Takagishi K, Osawa T, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of a rotator cuff tear in the general population. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2010; 19: 116–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minagawa H, Yamamoto N, Abe H, et al. Prevalence of symptomatic and asymptomatic rotator cuff tears in the general population: from mass-screening in one village. J Orthop 2013; 10: 8–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lädermann A, Denard PJ, Collin P. Massive rotator cuff tears: definition and treatment. Int Orthop 2015; 39: 2403–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bedi A, Dines J, Warren RF, et al. Massive tears of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010; 92: 1894–1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cvetanovich GL, Waterman BR, Verma NN, et al. Management of the irreparable rotator cuff tear. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2019; 27: 909–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geary MB, Elfar JC. Rotator cuff tears in the elderly patients. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil 2015; 6: 220–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niemeijer A, Lund H, Stafne SN, et al. Adverse events of exercise therapy in randomised controlled trials: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2020; 54: 1073–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bricca A, Harris LK, Jäger M, et al. Benefits and harms of exercise therapy in people with multimorbidity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Ageing Res Rev 2020; 63: 101166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slade SC, Finnegan S, Dionne CE, et al. The consensus on exercise reporting template (CERT) applied to exercise interventions in musculoskeletal trials demonstrated good rater agreement and incomplete reporting. J Clin Epidemiol 2018; 103: 120–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holden S, Rathleff MS, Jensen MB, et al. How can we implement exercise therapy for patellofemoral pain if we don’t know what was prescribed? A systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2018; 52: 385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Major DH, Røe Y, Grotle M, et al. Content reporting of exercise interventions in rotator cuff disease trials: results from application of the consensus on exercise reporting template (CERT). BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med 2019; 5: e000656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Slade SC, Dionne CE, Underwood M, et al. Consensus on exercise reporting template (CERT): explanation and elaboration statement. Br J Sports Med 2016; 50: 1428–1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ital J Public Health 2009; 6: 354–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. Rob 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Br Med J 2019; 366: I4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. Br Med J 2016; 355: I4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones IA, Togashi R, Heckmann N, et al. Minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for patient-reported shoulder outcomes. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2020; 29: 1484–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dabija DI, Jain NB. Minimal clinically important difference of shoulder outcome measures and diagnoses: a systematic review. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2019; 98: 671–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vad VB, Warren RF, Altchek DW, et al. Negative prognostic factors in managing massive rotator cuff tears. Clin J Sport Med 2002; 12: 151–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamada N, Hamada K, Nakajima T, et al. Comparison of conservative and operative treatments of massive rotator cuff tears. Tokai J Exp Clin Med 2000; 25: 151–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gutiérrez-Espinoza HJ, Lorenzo-García P, Valenzuela-Fuenzalida J, et al. Resultados funcionales de un programa de fisioterapia en pacientes con rotura masiva e irreparable del manguito rotador. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2021.;65:248-254. DOI: 10.1016/j.recot.2020.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levy O, Mullett H, Roberts S, et al. The role of anterior deltoid reeducation in patients with massive irreparable degenerative rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2008; 17: 863–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oyarzún DR, Quintanilla FA, Espinoza HG, et al. Terapia de juicio de lateralidad e imaginería de movimiento y ejercicios de activación muscular selectiva glenohumerales en sujetos con ruptura masiva del manguito rotador: serie de casos. Rev la Soc Esp del Dolor 2018; 25: 197–206. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Veen EJD, Diercks RL, Landman EBM, et al. The results of using a tendon autograft as a new rotator cable for patients with a massive rotator cuff tear: a technical note and comparative outcome analysis. J Orthop Surg Res 2020; 15: 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yian EH, Sodl JF, Dionysian E, et al. Anterior deltoid reeducation for irreparable rotator cuff tears revisited. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2017; 26: 1562–1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yildirim Güzelant A, Sarifakioğlu AB, Korcan Gönen A, et al. Massive retracted irreparable rotator cuff tears: what is the effect of conservative therapy? Turk Geriatri Derg 2014; 17: 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zingg PO, Jost B, Sukthankar A, et al. Clinical and structural outcomes of nonoperative management of massive rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007; 89: 1928–1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ainsworth R. Physiotherapy rehabilitation in patients with massive, irreparable rotator cuff tears. Musculoskeletal Care 2006; 4: 140–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ainsworth R, Lewis J, Conboy V. A prospective randomized placebo controlled clinical trial of a rehabilitation programme for patients with a diagnosis of massive rotator cuff tears of the shoulder. Shoulder Elbow 2009; 1: 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cavalier M, Jullion S, Kany J, et al. Management of massive rotator cuff tears: prospective study in 218 patients. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2018; 104: S193–S197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Christensen BH, Andersen KS, Rasmussen S, et al. Enhanced function and quality of life following 5 months of exercise therapy for patients with irreparable rotator cuff tears - an intervention study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2016; 17: 252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Collin PG, Gain S, Nguyen Huu F, et al. Is rehabilitation effective in massive rotator cuff tears? Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2015; 101: S203–S205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gutiérrez-Espinoza H, Arriagada-Núñez V, Araya-Quintanilla F, et al. Physical therapy in patients over 60 years of age with a massive and irreparable rotator cuff tear: a case series. J Phys Ther Sci 2018; 30: 1126–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shepet KH, Liechti DJ, Kuhn JE. Nonoperative treatment of chronic, massive irreparable rotator cuff tears: a systematic review with synthesis of a standardized rehabilitation protocol. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2021; 30: 1431–1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agout C, Berhouet J, Spiry C, et al. Functional outcomes after non-operative treatment of irreparable massive rotator cuff tears: prospective multicenter study in 68 patients. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2018; 104: S189–S192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoon T-HH, Kim S-JJ, Choi C-HH, et al. An intact subscapularis tendon and compensatory teres minor hypertrophy yield lower failure rates for non-operative treatment of irreparable, massive rotator cuff tears. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2019; 27: 3240–3245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Juhan T, Stone M, Jalali O, et al. Irreparable rotator cuff tears: current treatment options. Orthop Rev 2019; 11: 8146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pieters L, Lewis J, Kuppens K, et al. An update of systematic reviews examining the effectiveness of conservative physiotherapy interventions for subacromial shoulder pain. J Orthop Sport Phys Ther 2020; 50: 131–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Edwards P, Ebert J, Joss B, et al. Exercise rehabilitation in the non-operative management of rotator cuff tears: a review of the literature. Int J Sports Phys Ther 2016; 11: 279–301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bateman M, Jaiswal A, Tambe AA, et al. Diagnosis and management of atraumatic shoulder instability. J Arthrosc Jt Surg 2018; 5: 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Michener LA, Abrams JS, Huxel Bliven KC, et al. National athletic trainers’ association position statement: evaluation, management, and outcomes of and return-to-play criteria for overhead athletes with superior labral anterior-posterior injuries. J Athl Train 2018; 53: 209–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Littlewood C, Malliaras P, Chance-Larsen K. Therapeutic exercise for rotator cuff tendinopathy: a systematic review of contextual factors and prescription parameters. Int J Rehabil Res 2015; 38: 95–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Young JL, Rhon DI, Cleland JA, et al. The influence of exercise dosing on outcomes in patients with knee disorders: a systematic review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2018; 48: 146–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmidt CC, Morrey BF. Management of full-thickness rotator cuff tears: appropriate use criteria. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2015; 24: 1860–1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pieters L, Lewis J, Kuppens K, et al. An update of systematic reviews examining the effectiveness of conservative physical therapy interventions for subacromial shoulder pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2020; 50: 131–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khatri C, Ahmed I, Parsons H, et al. The natural history of full-thickness rotator cuff tears in randomized controlled trials: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med 2019; 47: 1734–1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Borde R, Hortobágyi T, Granacher U. Dose–response relationships of resistance training in healthy old adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med 2015; 45: 1693–1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gutiérrez-Espinoza H, Araya-Quintanilla F, Cereceda-Muriel C, et al. Effect of supervised physiotherapy versus home exercise program in patients with subacromial impingement syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys Ther Sport 2020; 41: 34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Longo UG, Berton A, Ambrogioni LR, et al. Cost-effectiveness of supervised versus unsupervised rehabilitation for rotator-cuff repair: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17: 2852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cuff A, Littlewood C. Subacromial impingement syndrome – what does this mean to and for the patient? A qualitative study. Musculoskelet Sci Pract 2018; 33: 24–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sandford FM, Sanders TAB, Lewis JS. Exploring experiences, barriers, and enablers to home- and class-based exercise in rotator cuff tendinopathy: a qualitative study. J Hand Ther 2017; 30: 193–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Young JL, Rhon DI, de Zoete RMJ, et al. The influence of dosing on effect size of exercise therapy for musculoskeletal foot and ankle disorders: a systematic review. Braz J Phys Ther 2018; 22: 20–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grgic J, Schoenfeld BJ, Davies TB, et al. Effect of resistance training frequency on gains in muscular strength: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med 2018; 48: 1207–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schoenfeld BJ, Grgic J, Krieger J. How many times per week should a muscle be trained to maximize muscle hypertrophy? A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies examining the effects of resistance training frequency. J Sports Sci 2019; 37: 1286–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fragala MS, Cadore EL, Dorgo S, et al. Resistance training for older adults: position statement from the national strength and conditioning association. J Strength Cond Res 2019; 33: 2019–2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Page P, Hoogenboom B, Voight M. Improving the reporting of therapeutic exercise interventions in rehabilitation research. Int J Sports Phys Ther 2017; 12: 297–304. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Slade SC, Dionne CE, Underwood M, et al. Consensus on exercise reporting template (Cert): modified delphi study. Phys Ther 2016; 96: 1514–1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hecksteden A, Faude O, Meyer T, et al. How to construct, conduct and analyze an exercise training study? Front Physiol 2018; 9: 1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Collin P, Matsumura N, Lädermann A, et al. Relationship between massive chronic rotator cuff tear pattern and loss of active shoulder range of motion. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2014; 23: 1195–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dunn WR, Kuhn JE, Sanders R, et al. Neer Award: predictors of failure of nonoperative treatment of chronic, symptomatic, full-thickness rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2013; 2016: 1303–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dunn WR, Schackman BR, Walsh C, et al. Variation in orthopaedic surgeons’ perceptions about the indications for rotator cuff surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; 87: 1978–1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fucentese SF, von Roll AL, Pfirrmann CWA, et al. Evolution of nonoperatively treated symptomatic isolated full-thickness supraspinatus tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012; 94: 801–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Torrens C, Miquel J, Santana F. Do we really allow patient decision-making in rotator cuff surgery? A prospective randomized study. J Orthop Surg Res 2019; 14: 116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Puzzitiello RN, Patel BH, Nwachukwu BU, et al. Adverse impact of corticosteroid injection on rotator cuff tendon health and repair: a systematic review. Arthrosc 2020; 36: 1468–1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chang KV, Hung CY, Wu WT, et al. Comparison of the effectiveness of suprascapular nerve block with physical therapy, placebo, and intra-articular injection in management of chronic shoulder pain: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2016; 97: 1366–1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Powell JK, Lewis JS. Rotator cuff-related shoulder pain: is it time to reframe the advice, ‘you need to strengthen your shoulder’? J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2021; 51: 156–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-sel-10.1177_17585732221140113 for Content reporting and effectiveness of therapeutic exercise in the management of massive rotator cuff tears: A systematic review with 490 patients by Rubén Fernández-Matías, Fernando García-Pérez, Néstor Requejo-Salinas, Carlos Gavín-González, Javier Martínez-Martín, Homero García-Valencia and Mariano Tomás Flórez-García in Shoulder & Elbow

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-sel-10.1177_17585732221140113 for Content reporting and effectiveness of therapeutic exercise in the management of massive rotator cuff tears: A systematic review with 490 patients by Rubén Fernández-Matías, Fernando García-Pérez, Néstor Requejo-Salinas, Carlos Gavín-González, Javier Martínez-Martín, Homero García-Valencia and Mariano Tomás Flórez-García in Shoulder & Elbow

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-sel-10.1177_17585732221140113 for Content reporting and effectiveness of therapeutic exercise in the management of massive rotator cuff tears: A systematic review with 490 patients by Rubén Fernández-Matías, Fernando García-Pérez, Néstor Requejo-Salinas, Carlos Gavín-González, Javier Martínez-Martín, Homero García-Valencia and Mariano Tomás Flórez-García in Shoulder & Elbow

Supplemental material, sj-docx-4-sel-10.1177_17585732221140113 for Content reporting and effectiveness of therapeutic exercise in the management of massive rotator cuff tears: A systematic review with 490 patients by Rubén Fernández-Matías, Fernando García-Pérez, Néstor Requejo-Salinas, Carlos Gavín-González, Javier Martínez-Martín, Homero García-Valencia and Mariano Tomás Flórez-García in Shoulder & Elbow

Supplemental material, sj-docx-5-sel-10.1177_17585732221140113 for Content reporting and effectiveness of therapeutic exercise in the management of massive rotator cuff tears: A systematic review with 490 patients by Rubén Fernández-Matías, Fernando García-Pérez, Néstor Requejo-Salinas, Carlos Gavín-González, Javier Martínez-Martín, Homero García-Valencia and Mariano Tomás Flórez-García in Shoulder & Elbow

Supplemental material, sj-docx-6-sel-10.1177_17585732221140113 for Content reporting and effectiveness of therapeutic exercise in the management of massive rotator cuff tears: A systematic review with 490 patients by Rubén Fernández-Matías, Fernando García-Pérez, Néstor Requejo-Salinas, Carlos Gavín-González, Javier Martínez-Martín, Homero García-Valencia and Mariano Tomás Flórez-García in Shoulder & Elbow

Supplemental material, sj-docx-7-sel-10.1177_17585732221140113 for Content reporting and effectiveness of therapeutic exercise in the management of massive rotator cuff tears: A systematic review with 490 patients by Rubén Fernández-Matías, Fernando García-Pérez, Néstor Requejo-Salinas, Carlos Gavín-González, Javier Martínez-Martín, Homero García-Valencia and Mariano Tomás Flórez-García in Shoulder & Elbow

Supplemental material, sj-docx-8-sel-10.1177_17585732221140113 for Content reporting and effectiveness of therapeutic exercise in the management of massive rotator cuff tears: A systematic review with 490 patients by Rubén Fernández-Matías, Fernando García-Pérez, Néstor Requejo-Salinas, Carlos Gavín-González, Javier Martínez-Martín, Homero García-Valencia and Mariano Tomás Flórez-García in Shoulder & Elbow