Abstract

By inhibition of JAK-STAT signaling, SOCS1 acts as a master regulator of the cytokine response across numerous tissue types and cytokine pathways. Haploinsufficiency of SOCS1 has recently emerged as a monogenic immunodysregulatory disease with marked clinical variability. Here, we describe a patient with severe dermatitis, recurrent skin infections, and psoriatic arthritis that harbors a novel heterozygous mutation in SOCS1. The variant, c.202_203delAC, generates a frameshift in SOCS1, p.Thr68fsAla*49, which leads to complete loss of protein expression. Unlike WT SOCS1, Thr68fs SOCS1 fails to inhibit JAK-STAT signaling when expressed in vitro. The peripheral immune signature from this patient was marked by a redistribution of monocyte sub-populations and hyper-responsiveness to multiple cytokines. Despite this broad hyper-response across multiple cytokine pathways in SOCS1 haploinsufficiency, the patient’s clinical disease was markedly responsive to targeted IL4Rα- and IL17-blocking therapy. In accordance, the mutant allele was unable to regulate IL4Rα signaling. Further, patient cells were unresponsive to IL4/IL13 while on monoclonal antibody therapy. Together, this study reports a novel SOCS1 mutation and suggests that IL4Rα blockade may serve as an unexpected, but fruitful therapeutic target for some patients with SOCS1 haploinsufficiency.

Keywords: Inborn errors of immunity, SOCS1, autoimmunity, autoinflammation, JAK-STAT signaling, cytokine

Introduction

Intricate regulation of cytokine signaling is essential for homeostasis. Accordingly, inborn errors of immunity involving negative regulators of cytokine signaling have devastating consequences on human immunity [1]. Often, these disorders disrupt the JAK-STAT axis, a highly-conserved pathway whereby receptor-associated kinases, JAKs, relay signaling from the cytokine receptor to a family of transcription factors, the STATs [2]. The negative regulators of this signaling cascade are often pathway-specific, and in turn, the associated monogenic disorders that involve these regulators present with specific clinical pathologies. Characteristic examples include defects in type-I interferon negative regulation [3–6] and deficiencies of soluble receptor decoys [7].

In contrast, the recently-described haploinsufficiency of SOCS1 (Suppressor-of-Cytokine-Signaling-1) represents the loss of a near-universal regulator of JAK-STAT cytokine signaling [8, 9]. SOCS1 functions via two distinct inhibitory domains: a Kinase-Inhibitory Region (KIR) that directly inhibits JAK enzymatic activity and a SOCS box that recruits ubiquitin ligases for the degradation of signaling intermediates [10]. As opposed to other negative regulators, SOCS1 exhibits remarkable breadth of action across numerous cytokine pathways and cell types. Consequently, a wide spectrum of clinical phenotypes has been associated with SOCS1 haploinsufficiency. Most patients present with prominent autoimmune, autoinflammatory and atopic features, with a subset demonstrating infectious complications [8, 9, 11–14]. Furthermore, the optimal therapeutic strategy remains elusive.

Methods

Genetic Sequencing

Genomic DNA was isolated from a sample of patient blood with routine methods. We first sequenced DNA for exons 3 and 4 of CARD14 to exclude cases with pathogenic mutations in its hotspot regions, given the phenotypic resemblance to the monogenic psoriasis syndromes seen in patients with activating CARD14 mutations [15]. Since these were not detected, DNA was sent to the Broad Institute (www.broadinstitute.org) for exome sequencing to an average sequencing depth of 20×. Data were analyzed with Engenome software (https://engenome.com/). Candidate de novo mutations were confirmed visually with the integrated genomics viewer (www.broadinstitute.org) and investigated for pathogenicity with ANNOVAR [16].

For confirmation of the SOCS1 p.Thr68fs (c.202_203delAC) mutation, the region of interest was amplified by RT-PCR using mRNA isolated from the patient’s peripheral blood and analyzed by Sanger sequencing.

Molecular Cloning and Ectopic Expression

WT and mutant SOCS1 mRNA were cloned by PCR from patient blood into a CMV-driven, Hygromycin-resistant backbone using the Gateway cloning platform (Thermo Fisher). Lentiviral particles were generated in HEK293T cells by CaCl2 transfection using the SOCS1 constructs, psPAX2, and pMD2. For transductions, A549 cells were treated with lentiviral particles and polybrene, followed by selection with hygromycin until a negative control (un-transduced cells) was eliminated. For transient expression, cells were transfected with Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cell Culture and Cytokine Stimulations

HEK293T and A549 cells were cultured at 37 °C with 10% CO2 in DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen), GlutaMAX (Gibco), and penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco). Cell lines were regularly tested for mycoplasma contamination with the E-MYCO PCR kit (Fischer Scientific). Whole blood samples from the patient and healthy donors were collected into sodium heparin vacutainer tubes and transferred to non-treated tissue culture plates for experimentation. For cytokine stimulation, cell lines or whole blood were treated for 15 min with either Interferon-I (IFNα2b, Intron-A, Merck), Interferon-II (IFNγ), IL4, or IL13 (Biolegend) at the indicated doses. To cease the stimulation, cells were either lysed or chemically-stabilized, as detailed below.

mRNA Isolation and qPCR

RNA was isolated from whole blood using the PaxGene Blood RNA kit (PreAnalytix). The Qiagen RNeasy kit was used for RNA extraction from cell culture. cDNA was generated via reverse-transcription (ABI High Capacity Reverse Transcription). The expression of target genes was determined using TaqMan primer-probes against the following genes: SOCS1, MX1, IFI27, 18S, and GAPDH. Quantitative PCR was performed using TaqMan Universal Master Mix II with uracil-DNA glycosylases on a QuantStudio 6 Pro light cycler (Applied Biosystems). The relative levels of gene expression were calculated by the ΔΔCT method, relative to 18S or, and the mean values for the mock-treated controls or healthy donors.

Immunoblotting

Whole-cell extracts were prepared by lysis of trypsin-released cells in RIPA lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with protease/phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Cell Signaling Technology). Lysates were then centrifuged and manually cleared of insoluble components by pipetting. Samples were denatured in NuPage buffer (Invitrogen) at 95 °C for 5 min. Gel electrophoresis and membrane transfer to PVDF membranes were conducted with the Bio-Rad Western Blot kit. Blocking occurred in 5% BSA for primary antibodies or 5% nonfat dry milk for secondary antibodies. Antibodies against the following proteins were used: SOCS1 (ThermoFisher), Flag M2 (Sigma Aldrich), phospho-Tyr 701 STAT1 (Cell Signaling Technology), phosphor-Tyr 689 STAT2 (Cell Signaling Technology), phospho-Tyr 641 STAT6 (Cell Signaling Technology), USP18 (Cell Signaling Technology), and β-actin (Cell Signaling Technology). Signal was detected with the enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagent Super-Signal West pico (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and imaged on the Cytiva ImageQuant 800.

Luciferase Assay

HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with SOCS1 or control constructs and Interferon-Stimulated Response Element (ISRE) Luciferase plasmids as per the manufacturer’s protocol using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (ProMega). Signal was detected using a PerkinElmer Envision 2105 plate reader.

Mass Cytometry

For immunophenotyping, surface markers were labeled using the Maxpar Direct Immune Profiling Assay (Standard BioTools) and blood was subsequently stabilized with Proteomic Stabilizer PROT1 (SmartTube) and stored at −80 °C. For analysis of cell signaling, whole blood was stimulated, immediately stabilized with PROT1 and frozen at −80 °C prior to staining. The standard mass cytometry staining and processing protocols were then performed as detailed in Gruber et al [17]. In brief, samples were thawed, barcoded, and blocked to prevent non-specific binding, surface-stained with antibody cocktails, permeabilized with methanol, and then stained for intracellular markers. Samples were then acquired on the on a Helios mass cytometer (Fluidigm). Acquired events were then normalized and concatenated with Fluidigm acquisition software, and the barcoded samples were deconvoluted. The FCS files were then analyzed on Cytobank (Beckman Coulter), using traditional biaxial gating of immune populations. Mean signal intensities were calculated, and relative induction was determined by normalization relative to the mean for healthy control samples.

Clinical Therapy

Subcutaneous secukinumab therapy was initiated at a loading dose of 300 mg administered weekly, then spaced to a maintenance dosing interval of every 4 weeks, as per standard recommendations. After approximately 4 months, therapy was held for 2 months due to patient preference in the setting of a sub-optimal treatment response. Secukinumab was then restarted at the same dosing regimen as previously mentioned. Approximately 4 months later, dupilumab was added for combined therapy. Subcutaneous dupilumab administration followed standard dosing, with an initial dose of 600 mg, followed by 300 mg given every 2 weeks.

Statistics

Statistical analysis and graphing was carried out using R 4.2.2 and the ggplot2, ggpubr, and rstatix package. Bar-plots represent mean values with error bars indicating the standard error. Box plots represent median and interquartile values with error bars indicating the 95% confidence interval. When p-values are provided, these reflect the results of multiple t-tests of the corresponding comparisons indicated in the figure.

Results

A Patient with Severe Dermatitis, Recurrent Skin Infections, and Psoriatic Arthritis

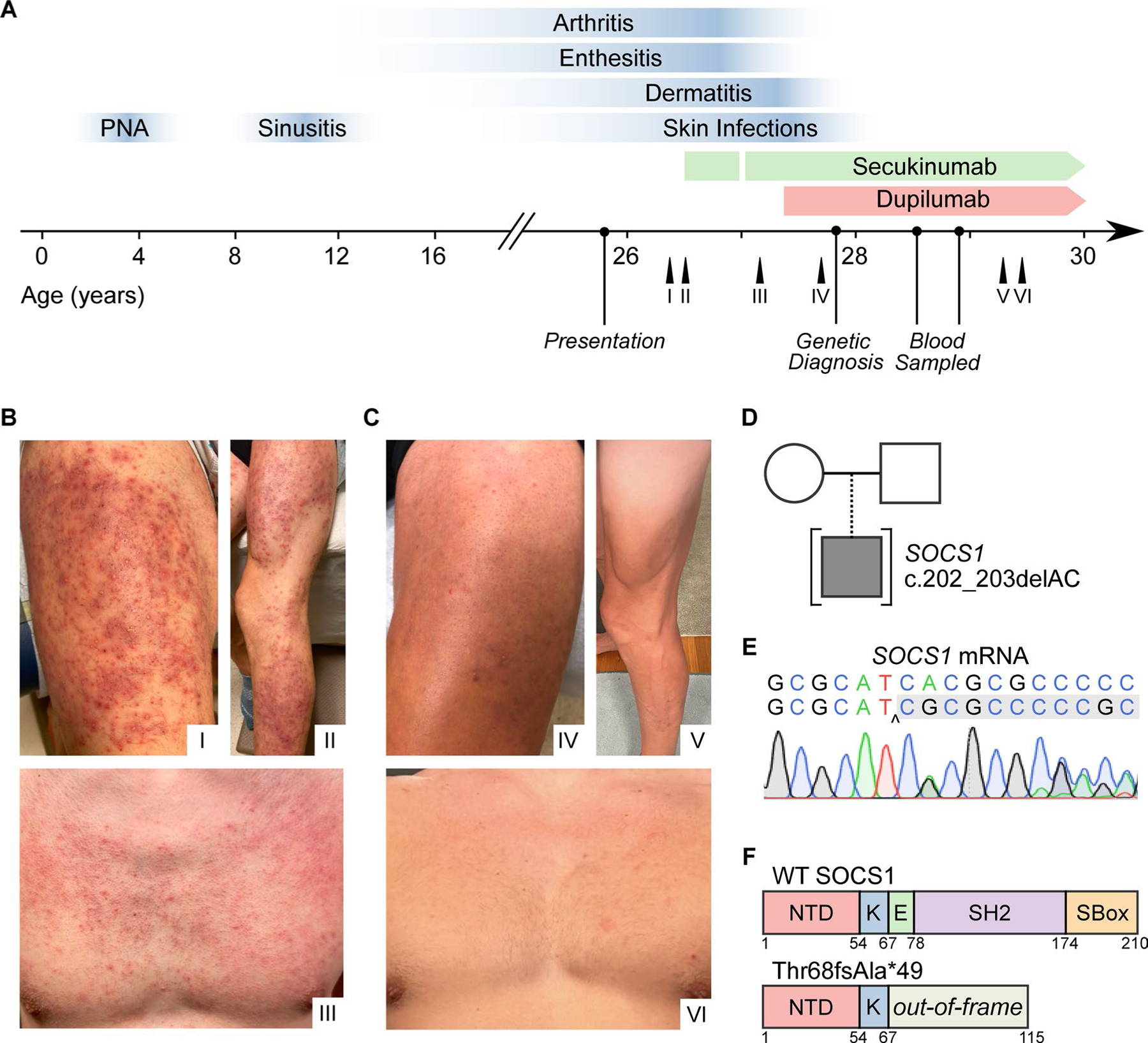

Here, we report on a 25-year-old male presenting to our multidisciplinary team for chronic severe dermatitis with psoriatic and eczematous features, complicated by recurrent follicular inflammation and skin infections. Longitudinal clinical review (detailed in Fig. 1A) revealed an early childhood history of failure-to-thrive and multiple infections, including pneumonia and sinusitis. Around age 10, he developed an undifferentiated chronic polyarticular arthritis, marked by intermittent fevers, enthesitis, sacroiliitis, and nail pitting. This was initially diagnosed as enthesitis-related juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), but later suspected to be psoriatic arthritis given the subsequent development of psoriatic-like plaques in adolescence. Most prominently, there was an approximate 10-year history of severe, recurrent folliculitis on the extremities with concomitant eczematous patches (Fig. 1B). Affected lesions repeatedly cultured positive for methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus, which required antibiotic courses of increasing potency.

Fig. 1.

Identification of a heterozygous SOCS1 mutation in a patient with severe dermatitis and psoriatic arthritis. A Clinical timeline mapping key disease features (blue) throughout time relative to treatment with dupilumab and secukinumab therapy. Labeled arrows (I–VI) indicate the timing at which photographs were taken, with roman numerals corresponding to those in B and C. B Dermatitis of the anterior thigh (I), leg (II), and chest (III) before clinical therapy. C Dermatitis of the anterior thigh (IV), leg (V), and chest (VI) after clinical therapy. D Family pedigree demonstrating the SOCS1 variant in the proband. E Sanger sequencing of the locus of interest of SOCS1 mRNA isolated from whole blood. F Linear structure of SOCS1 protein in the WT and mutant alleles. Abbreviations as follows: N-terminal domain (NTD), kinase domain (K), extended-SH2 domain (E), Src homology domain (SH2), and SOCS box (SBOX).

At time of consultation, immunologic work-up revealed grossly normal levels of lymphocyte populations and immunoglobulin subtypes (Table 1 part A and B). Autoimmune serologies and related studies were negative (Table 1 part C). Analysis of immunization serologies revealed low titers for some live virus vaccines (mumps, rubella, and varicella) but adequate humoral responses to protein vaccine antigens (Table 1 part D).

Table 1.

Hematologic and immunologic parameters. (A) Peripheral blood immunophenotyping. (B) Quantitative immunoglobulin concentrations. (C) Autoimmune assays, including serologies, complement levels, and HLA genotyping. (D) Serological testing for vaccine responses

| A. Peripheral blood phenotyping | ||

|---|---|---|

| Test | Reference range and units | Result |

| White blood cell | 3.4–10.8 × 10E3/μL | 6.5 |

| Hemoglobin | 13.0–17.7 g/dL | 14.6 |

| Platelet | 150–450 × 10E3/μL | 252 |

| Neutrophil | 1.4–7.0 × 10E3/μL | 4.3 |

| Immature granulocyte count | 0.0–0.1 × 10E3/μL | 0.0 |

| Eosinophil count | 0.0–0.4 × 10E3/μL | 0.1 |

| Basophil count | 0.0–.2 × 10E3/μL | 0.1 |

| Monocyte count | 0.1–0.9 × 10E3/μL | 0.8 |

| Lymphocyte count | 0.7–3.1 × 10E3/μL | 1.3 |

| CD19+ lymphocyte | 12–645/μL | 134 |

| NK (CD56+/16+) | 24–406/μL | 156 |

| CD 3+ T-cell count | 622–2402/μL | 989 |

| CD 4+ T-cell count | 359–1519/μL | 456 |

| CD 8+ T-cell count | 109–897/μL | 456 |

| CD4/CD8 Ratio | 0.92–3.72 | 1.00 |

| B. Quantitative immunoglobulins | ||

| Test | Reference range and units | Result |

| IgA total | 90–386 mg/dL | 54–86 ↓ |

| IgM total | 20–172 mg/dL | 43 |

| IgE total | 0–200 IU/mL | 140 |

| IgG total | 603–1613 mg/dL | 1368 |

| IgG, subclass 1 | 248–810 mg/dL | 890 ↑ |

| IgG, subclass 2 | 130–555 mg/dL | 320 |

| IgG, subclass 3 | 15–102 mg/dL | 102 |

| IgG, subclass 4 | 2–96 mg/dL | 101 ↑ |

| C. Autoimmune assays | ||

| Test | Reference range and units | Result |

| Complement C3 | 90–187 mg/dL | 118 |

| Complement C4 | 16–45 mg/dL | 16.5 |

| Anti-S. Cerevisiae IgA | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-S. Cerevisiae IgG | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-myeloperoxidase IgG | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-serine protease 3 IgG | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-tissue transglutaminase | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-endomysial | Negative | Negative |

| Antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-gliadin IgG | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-gliadin IgA | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-chimeric antibodies | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-nuclear antibody | Negative | Negative |

| Rheumatoid factor | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-Dnase B | Negative | Negative |

| Anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide | Negative | Negative |

| Cryoglobulin | Negative | Negative |

| HLA-B27 genotyping | Negative | Negative |

| D. Vaccine serologies | ||

| IgG target | Index | Value |

| Rubella | > 0.99 IV | < 0.90 ↓ |

| Rubeola | > 16.4 AU/mL | 74.4 |

| Mumps | > 10.9 AU/mL | < 9.0 ↓ |

| Varicella | > 165 IV | < 135 ↓ |

| Haemophilus influenzae B | > 0.15 ug/mL | 0.23 |

| Diphtheria antitoxoid | < 0.10 IU/mL | 0.21 |

| Tetanus antitoxoid | < 0.10 IU/mL | 0.49 |

Throughout the course of his illness, suboptimal treatment responses had been observed to numerous immunomodulatory therapies, including methotrexate, infliximab, canakinumab, colchicine, acitretin, and etanercept. Initially, the patient was started on secukinumab for psoriatic arthritis, with mild improvement in his dermatologic and articular disease. However, he continued to have recurrent skin infections in the setting of chronic dermatitis despite management with several topical therapies. After several months, dupilumab was added to treat the ongoing dermatitis, with concurrent use of secukinumab (Fig. 1A). Remarkably, the patient’s dermatitis and folliculitis rapidly improved (Fig. 1C). Complete remission of all disease features has persisted on dual therapy, with only minor relapses occurring following missed doses of dupilumab.

Sequencing Reveals a Heterozygous Mutation in SOCS1

Given the severity, early-onset, and multi-system involvement of disease, genetic analysis was performed to assess for a genetic etiology. Whole exome sequencing revealed a heterozygous two base-pair deletion in the SOCS1 gene, c.202_203delAC (Fig. 1D). Sequencing of gDNA from family members was deferred as the patient was adopted. Sanger sequencing confirmed the presence of the heterozygous deletion in SOCS1 (Fig. 1E). Additionally, the variant was absent from all public genome data bases queried. The resulting mutation, Thr68fsAla*49, generates a frameshift with a subsequent premature stop codon in the Extended SH2 domain (Fig. 1F). The product, if translated, is predicted to encode a truncated peptide containing only the N-terminal and Kinase-Inhibitory-Region (KIR) domains. In accordance, the mutation was predicted to be deleterious by in silico prediction, with a CADD score of 32, above the Mutation Significance Cutoff (MSC) threshold of 11.6.

Thr68fsAla*49 SOCS1 Fails to Inhibit Cytokine Signaling via Loss‑of‑Expression

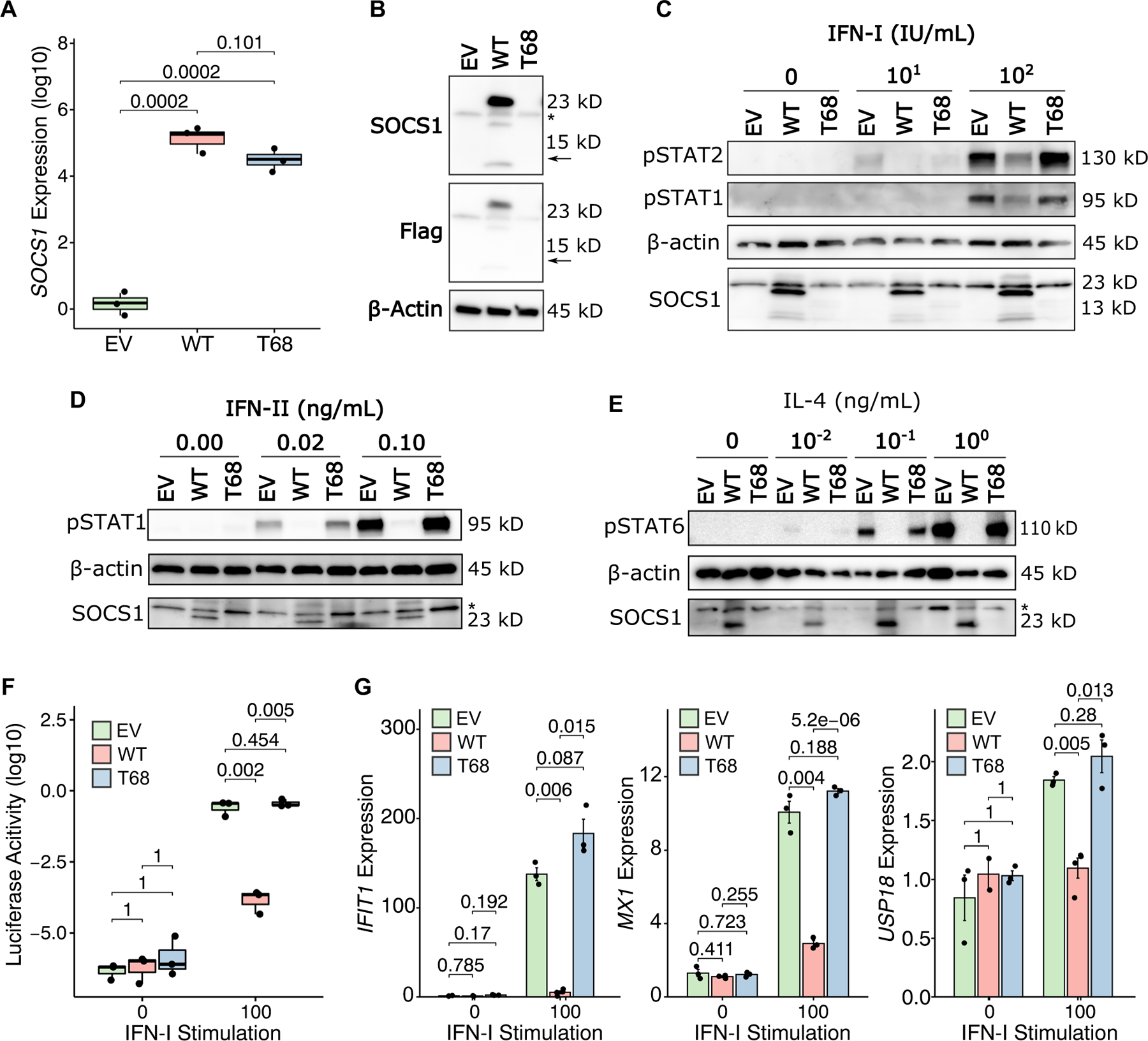

To study the effect of c.202_203delAC SOCS1, the mutant and WT alleles were cloned from patient whole blood into lentiviral expression vectors carrying an N-terminal Flag-tag. In parallel, an empty vector (EV) negative control was generated. Constructs were then transfected or transduced into HEK293T and A549 cells. Analysis by qPCR for SOCS1 mRNA levels revealed similar expression of the WT and mutant alleles (Fig. 2A). In contrast, no mutant protein expression was detected by immunoblotting (Fig. 2B). As neither an anti-SOCS1 polyclonal antibody nor an anti-Flag antibody produced an immunoblot signal in the mutant allele, it was determined that no truncated protein is produced from Thr68fsAla*49 SOCS1.

Fig. 2.

SOCS1 T68fs fails to inhibit cytokine signaling by loss-of-expression. A SOCS1 mRNA levels by qPCR in A549 cells transduced with either empty vector (EV), WT SOCS1, or T68fs SOCS1. P-values for individual comparisons from statistical testing shown above. B Western blotting for Flag-tagged SOCS1 transfected into HEK239T cells. Immunoblotting by polyclonal SOCS1 antibodies or anti-Flag antibody. For anti-SOCS1 immunoblotting, the band present in all conditions below ~23kDa is non-specific. The horizontal arrow indicates the predicted molecular weight of T68fs SOCS1. The asterisk indicates the non-specific band. C Western blot for STAT1/2 phosphorylation by IFN-I stimulation of SOCS1-transfected HEK239T cells. D Western blot for STAT1 phosphorylation by IFN-II stimulation of SOCS1-transduced A549 cells. E Western blot for STAT6 phosphorylation by IL4 in SOCS1-transduced A549 cells. F ISRE-inducible Luciferase activity in SOCS1-transfected HEK239T cells stimulated with IFN-I. G Interferon-stimulated gene induction in SOCS1-transfected HEK239T cells stimulated with IFN-I.

Next, we assessed whether Thr68fsAla*49 SOCS1 retained any inhibitory function despite undetectable protein expression. To test inhibition of cytokine signaling, SOCS1 vectors were ectopically expressed in the HEK293T or A549 cells, which were then stimulated briefly with increasing doses of JAK-STAT cytokines and analyzed by Western Blot for downstream STAT phosphorylation. Whereas WT SOCS1 overexpression abrogates nearly all cytokine-induced STAT phosphorylation, Thr68fsA*49 SOCS1 fails to inhibit the response to type-I-Interferon (IFN-I), type-II-interferon (IFN-II), or IL4 (Fig. 2C–E). These signaling effects were independent of total STAT expression (Supplementary Figure 1). The downstream impacts of this were then further validated in both an ISRE-regulated Luciferase system (Fig. 2F) and by qPCR for target gene expression (MX1, IFIT1, USP18) after prolonged IFN-I stimulation (Fig. 2G). Together, these studies demonstrate that Thr68fsAla*49 SOCS1 is complete loss-of-function by loss-of-expression.

Mass Cytometry on Peripheral Immune Cells Reveals Cytokine Hyper‑responsiveness

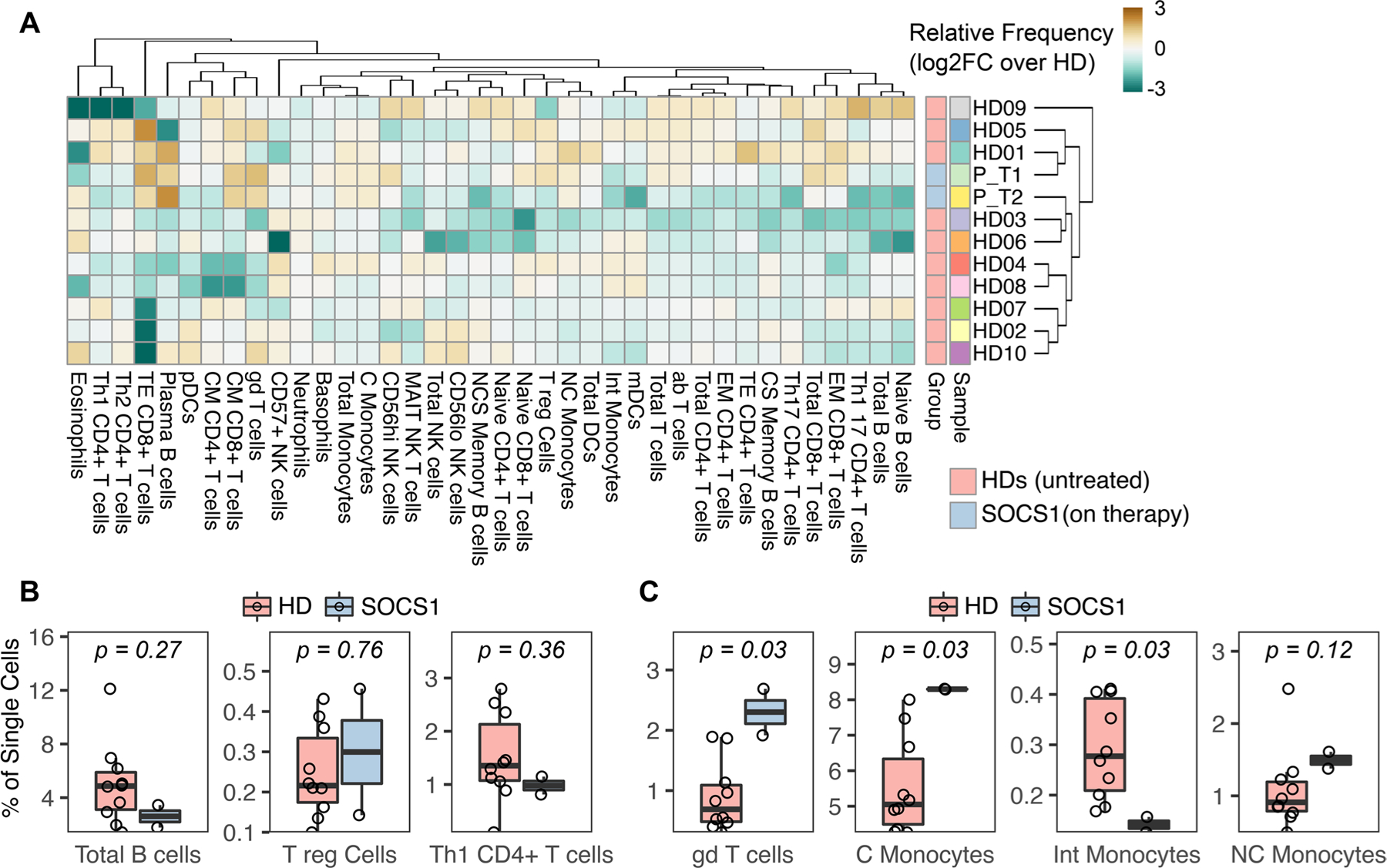

Given the broad involvement of SOCS1 in cytokine signaling across all immune cells, we utilized the breadth of mass cytometry to map the peripheral blood immunophenotype. At time of sampling, the patient was receiving dual monoclonal antibody therapy (please see collection timing in Fig. 1A). Nonetheless, a unique immunophenotype could be distinguished from peripheral blood of healthy donors (n = 10). By cell-type frequency, the patient immune signature clustered separately from healthy donor immune cells (Fig. 3A). As compared to prior reports, there were no significant differences in the distribution of B-cells, T-regulatory cells, nor Th1 CD4+ T-cells (Fig. 3B) [8, 9, 12–14]. Additionally, there were no relative changes in Th-17 cell frequencies (Supplementary Figure 2). Rather, the patient exhibited increases in the relative frequency of γδ T-cells and a re-distribution of monocytes toward a classical CD14+ phenotype (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Mass cytometry demonstrates monocyte and γδ T-cell skewing in peripheral blood. A Relative frequency of immune cell subsets in the patient (at two time points, P_T1 and P_T2) and healthy donors (n = 10). Color intensity indicates log2 fold-change of absolute frequency over the median frequency of the healthy donors. Abbreviations: Patient (P or “SOCS1”), healthy donor (HD), effector memory (EM), class switched (CS), non-class switched (NCS), myeloid dendritic cells (mDC), classical monocytes (C monocytes), central memory (CM). B Relative frequency of total B-cells, T-regulatory cells and Th1 CD4+ T-cells. C Relative frequency of γδ T-cells and monocyte subsets.

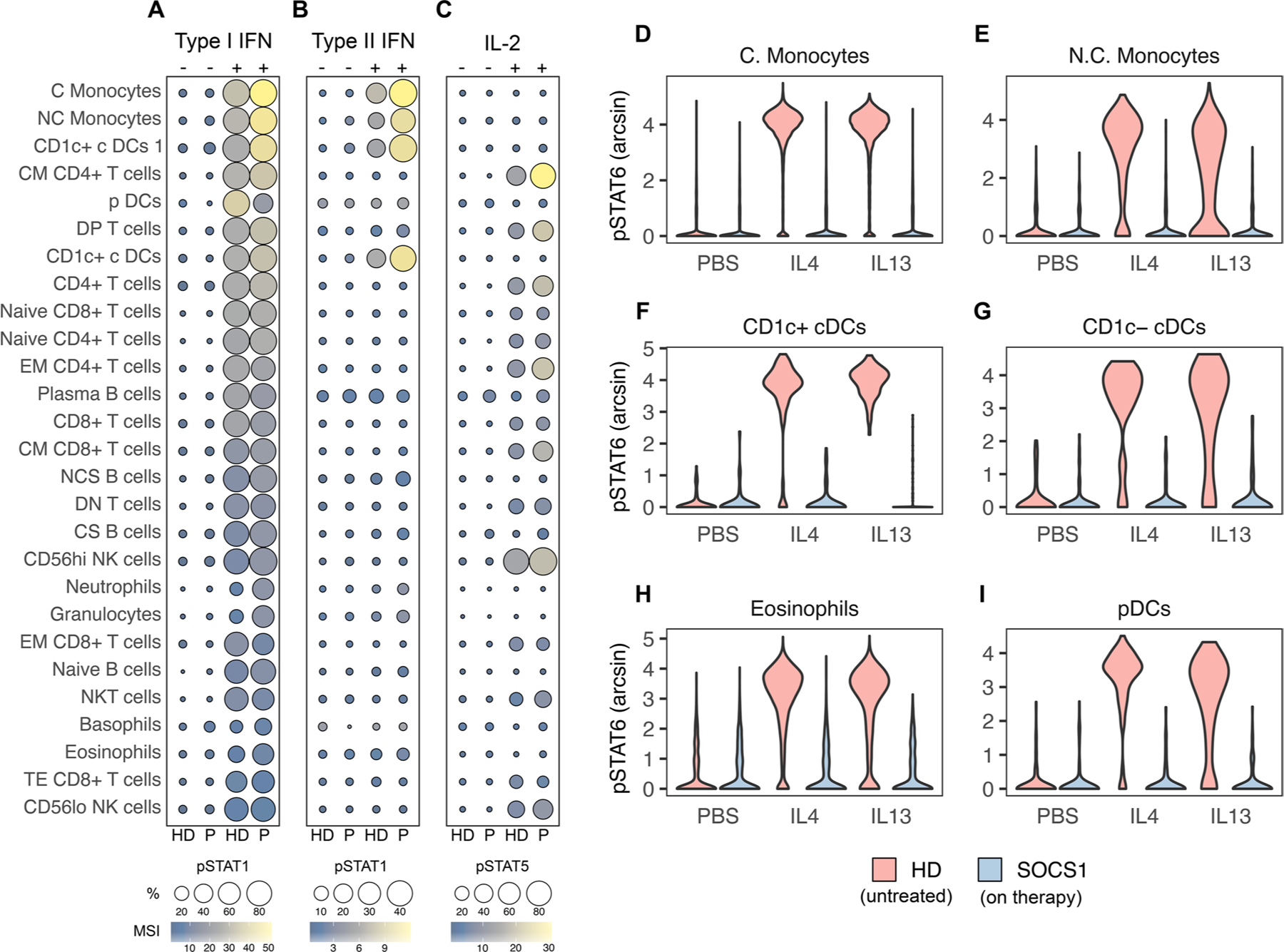

Whole blood was then stimulated ex vivo with cytokines to assess the in vivo potential for cytokine hyper-responsiveness in SOCS1 haploinsufficiency. Upon stimulation with IFN-I, IFN-II or IL2, patient cells demonstrated enhanced phosphorylation of downstream STAT proteins as compared to healthy donor cells (Fig. 4A–C). For these experiments, relatively low doses of cytokines were used to mimic physiologic conditions, identify uniquely sensitive cell types, and avoid saturation of signal transduction. Accordingly, monocyte and classical dendritic cell populations from the patient exhibited the strongest hyper-response to IFN-I and IFN-II, whereas pDC and T-cell subsets demonstrated the most exaggerated IL2 / pSTAT5 signaling.

Fig. 4.

SOCS1 T68fs immune cells hyper-respond to cytokine. A Interferon-alpha stimulation (1000 IU/mL) of whole blood and analysis of STAT1 phosphorylation by mass cytometry as measured by mean signal intensity (MSI) and percent positive relative to unstimulated. B Interferon-gamma stimulation (10 ng/mL) of whole blood and analysis of STAT1 phosphorylation as above. C IL2 (10 ng/mL) of whole blood and analysis of STAT5 phosphorylation as above. D–I IL4 and IL13 stimulation (both 10 ng/mL) of the indicated whole blood subsets and analysis of STAT6 phosphorylation. Healthy donor (HD, pink) and patient samples (P or “SOCS1”, blue).

We then confirmed that IL4Rα-signaling was effectively blocked via dupilumab. To interrogate this, patient blood was collected 2 weeks following an in vivo treatment with dupilumab and stimulated ex vivo with IL4 and IL13. As compared to healthy donor cells, which phosphorylate STAT6 after IL4 or IL13 stimulation, patient cells entirely lost their response (Fig. 4D–I). This absence of basal or inducible STAT6 phosphorylation functionally validates the efficacy of anti-IL4Rα therapy.

Discussion

With only limited reports published to date, SOCS1 haploinsufficiency and its pathogenesis remain poorly understood (Table 2). Here, we report a novel case that sheds light on this rapidly-developing clinical entity, from its genetic and immunologic underpinnings to the clinical diversity and therapeutic challenges.

Table 2.

Clinical and immunologic phenotypes reported in SOCS1 haploinsufficiency

| Study | Variant | Age | Predominant clinical phenotype | Auto-immunity | Auto-inflammation | Lymphoproliferative disease | Skin disease | Major infectious complications | Atopy | Quant. immunoglobulins | Major immune cell phenotypes | Systemic immune therapies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thaventhiran 2020 [9]1 | Y64* | 5 | HIES, purulent infections | AIN, AIHA, ITP, alopecia totalis | - | - | Eczema | Pneumonia, dental abscess, UTI, local HSV | Eczema AR Asthma | ↑↑IgE | ↓Th17, ↓Treg, ↑Th1 | Corticosteroids, IVIg, romiplostim |

| Y64* | 7 | EAA | Hashimotos thyroiditis | - | Splenomegaly | - | URI | ↓IgG ↓IgM ↓IgE ↓IgA |

↓↓B-cells | Corticosteroids | ||

| M161Afs | 8 | CVID with GLILD | ITP, AI hepatitis | Uveitis | Splenomegaly | - | URI, pneumonia, AOM | ↓IgG ↓IgM ↓IgE ↓IgA |

↓↓B-cells | Corticosteroids, rituximab, IVIg | ||

| Lee 2020 [12] | A37Rfs | 2 | Evans syndrome | AIN, ITP, AIHA | Fever, diarrhea, oral ulcers | - | - | - | ↓IgG ↓IgA |

↓Neutrophil, ↓CD8+ T-cell ↑Naive B-cell |

Corticosteroids, MMF | |

| A37Rfs | 14 | Evans syndrome, MIS-C | AIN, ITP, AIHA | MIS-C | - | MIS-C | - | ↓IgG ↓IgM ↓IgA |

↓Neutrophil, ↓T-cell ↑Naive B-cell |

Corticosteroids, MMF, IVIg, eltrombopag | ||

| Hadjadj 2020 [8] | P123R | 2 | Autoimmune cytopenias | ITP, AIHA | - | - | - | - | ↓SM B-cell, ↑CD21lo B-cell | Corticosteroids, IVIg, MMF | ||

| P123R | 6 | ITP | ITP, autoimmune thyroiditis | Polyarthritis | - | - | - | ↓MZ B-cell, ↑CD21lo B-cell | Corticosteroids | |||

| A9Pfs | 5 | Evans syndrome | AIN, ITP, AIHA | - | Splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy | - | Respiratory, herpes zoster | ↓SM B-cell ↑CD21lo B-cell ↓Neutrophil |

Corticosteroids, rapamycin, IVIg | |||

| A9Pfs | 3 | Psoriasis lymphoma | Celiac disease | - | Hodgkins lymphoma Psoriasis | - | ↑CD21lo B-cell | Chemotherapy | ||||

| M161Afs | 3 | Evans syndrome | ITP, AIHA | - | HSM, lymphadenopathy | Eczema | - | Eczema | - | ↓SM B-cell, ↑CD21lo B-cell | Corticosteroids, MMF | |

| R22W | 16 | SLE + LN-II | SLE + LN | - | - | Discoid lupus | - | - | - | ↓MZ B-cell ↓SM B-cell |

Corticosteroids, HCQ, MMF | |

| Y154H | 9 | SLE + LN-IV | SLE + LN | Fever, polyarthritis | - | Cutaneous lupus | - | - | - | ↓MZ B-cell ↓SM B-cell ↑CD21lo B-cell |

Corticosteroids, HCQ, MTX, CP, MMF, baricitinib | |

| Y154H | 8 | ITP | ITP, +ANA/dsD-NAAb | - | - | - | - | - | - | ↓MZ B-cell ↑CD21lo B-cell |

Corticosteroids, IVIg, HCQ, azathioprine, rituximab | |

| Y154H | 15 | Psoriasis | - | - | - | Psoriasis | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Y154H | 44 | Psoriasis autoimmunity | AI-hepatitis, AIPancreatitis | Spondylitis | - | Psoriasis | - | - | - | ↓MZ B-cell | Corticosteroids, HCQ, MTX, anti-TNFα | |

| Michniacki 2022 [13] | Δ 5 Mb2 | 5 | Enthesitis, bone marrow hypoplasia, ITP | ITP | Arthritis, enthesitis | - | - | SARS-CoV-2-induced inflammatory syndrome | ↑Eos, ↑IgE | ↑IgE | ↑B-cell, ↑Eosinophils ↑NK-cell |

JAK inhibitors |

| Hale 2023 [14] | M161Afs | 7 | ALPS, HPS, lethality | AIN, ITP | Pulmonary and hepatic failure, lethal ACR | ALPS, splenomegaly | - | Pneumonia, opportunistic infections | - | ↓IgM ↓IgA |

↑DNT TCRαβ+ ↓Neutrophil ↑Naïve B-cell |

Liver/lung transplant |

| M161Afs | 5 | Atopy autoinflammation | - | Fever | HSM, lymphadenopathy | Eczema | - | Eczema, AR, ↑Eos | - | ↑TCRγδ+ DNT, ↑Eosinophil | - | |

| This report | T68fs | 10 | Dermatitis polyarthritis | - | Fever, enthesitis, arthritis | - | Psoriasis, folliculitis, eczema | MSSA+ skin abscesses, pneumonia | Eczema | - | ↑TCRγδ+ ↑CD14+ Monocytes |

Secukinumab, dupilumab |

Clinical and biological features of all cases of SOCS1 haploinsufficiency reported to date [8, 9, 12–14], including the genetic variant, age at onset (years), reported clinical phenotypes, immunologic studies performed, and therapies utilized.

Also reported in Korholz 2021

5 MB microdeletion at 16p13.2p13

HIES hyper IgE syndrome, AIHA autoimmune hemolytic anemia, ITP immune-mediated thrombocytopenia, AR allergic rhinitis, UTI urinary tract infection, HSV herpes simplex virus, IVIg intravenous immunoglobulin, URI upper respiratory infection, EAA eosinophilic allergic alveolitis, CVID common variable immunodeficiency, GLILD granulomatous and lymphocytic interstitial lung disease, AOM acute otitis media, AIN autoimmune neutropenia, MMF mycophenolate mofetil, CP cyclophosphamide, MIS-C multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, SM B-cell switched memory B-cell, MZ B-cell marginal zone B-cell, HSM hepato-splenomegaly, SLE systemic lupus erythematosus, LN lupus nephritis, ANA anti-nuclear antibody, dsDNA Ab double-strand DNA antibody, AI-hepatitis autoimmune hepatitis, ALPS autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome, HPS hepatopulmonary syndrome, ACR acute cellular rejection

The asterisk is a standard notation in genetics to indicate a termination / stop codon

Genetically, Thr68fs SOCS1 constitutes a novel lesion in the SOCS1 gene. Like other SOCS1 frameshift or truncating mutations, which underlie the majority of SOCS1 haploinsufficiency [8, 9, 11–14], Thr68fs is complete loss-of-expression. Functionally, this loss leads to exaggerated responses to numerous cytokines. Among these are the IFN-I and IFN-II axes—the latter of which drives embryonic lethality in Socs1−/−mice [18]—and interleukin signaling (e.g., IL2 and IL4). As many of these cytokine pathways regulate immune cell proliferation and differentiation, it is unsurprising that abnormalities in the immunophenotype are common in SOCS1 haploinsufficiency (Table 2). Interestingly, the patient here was spared many of the common aberrations previously identified, including a depletion of Treg cells and a skewing of B-cell populations [8, 11, 14]. Instead, this patient’s peripheral immune repertoire demonstrated a redistribution in monocyte subtypes—the same cells which were noted to have the largest increase in IFN-I and IFN-II responsiveness. Nonetheless, it remains possible that our observations reflect secondary effects of clinical therapy with secukinumab and/or dupilumab, although these immunophenotypic changes have not been observed in other studies of patients on each of these therapies [19–21].

Clinically, this ex vivo IFN-I and IFN-II signature correlated with autoinflammatory overtones (intermittent fevers and an undifferentiated chronic polyarticular arthritis), which were accompanied by infectious complications and severe dermatitis (folliculitis, recurrent skin infections, psoriasis, eczema). While this constellation shares many of the features of previously-reported patients [8, 9, 11–14], the striking severity of the dermatologic manifestations are unique. Further, many features reported in prior studies are absent here. Namely, there was no evidence of autoantibodies, hypogammaglobulinemia, lymphoproliferation, or immune-mediated cytopenia. Without leukopenia or hypogammaglobulinemia, the etiology of infection-related disease in SOCS1 haploinsufficiency remains unclear. Specifically, this occurrence challenges whether infectious complications represent a bona fide susceptibility to infection versus an excessive inflammatory response to otherwise benign flora or minimally-virulent pathogens. Consistent with this “hyper-responsive” hypothesis is a recent report of SOCS1 haploinsufficiency presenting as severe enthesitis and ITP unmasked by SARS-CoV-2 infection [13].

To date, current therapeutic strategies in SOCS1 haploinsufficiency have largely relied on corticosteroids, traditional disease-modifying-antirheumatic drugs or JAK-inhibitors (Table 2) [8, 9, 11–14]. While the broad immune dysregulation of SOCS1 may merit such broad immunosuppression, targeted therapies may strike a more optimal risk-benefit. Here, we observed complete remission with dual IL4Rα and IL17A blockade. The exact contributions of each therapy are difficult to ascertain, as our analysis was limited by the unavailability of sample prior to each therapy. However, anti-IL4Rα seemed to confer the most profound therapeutic benefit, as the majority of clinical improvement occurred after addition of dupilumab, and relapse occurred with any missed doses.

As shown here and elsewhere, SOCS1 is a potent regulator of IL4Rα/IL4/IL13 signaling [22, 23]. However, it is unclear what allows for phenotypic rescue by specific IL4Rα pathway inhibition despite numerous other SOCS1-regulated cytokine pathways that remain hyper-responsive during dupilumab therapy. There may be significant pathway crosstalk or “dominant” pathogenic effects of increased IL4Rα signaling. Of note, is the biochemical and phenotypic overlap of SOCS1 haploinsufficiency with other rare monogenic disorders that upregulate IL4Rα signaling, such as JAK1 GoF [4, 24] and STAT6 GoF [25]. Studies of common genetic variation also draw connections to psoriasis, for which susceptibility loci have been mapped to the cluster of genes for IL4, IL5, and IL13 [26]. For IL17 signaling, genetic parallels are also evident: monogenic CARD14 gain-of-function disease, in which enhanced keratinocyte responsiveness to IL17A mediates psoriasis, phenocopies the dermatologic manifestations of SOCS1 haploinsufficiency [27].

The importance of these connections will be elucidated as more patients with SOCS1 haploinsufficiency are investigated, many of whom may benefit from IL4Rα +/− IL17 blockade. These future studies will require particular attention to not only the possible risks of additive adverse effects of combined therapy, but also the variable treatment responses across the spectrum of clinical phenotypes in SOCS1 haploinsufficiency.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patient for his generous participation in this research study. We also acknowledge the Human Immune Monitoring Center at the Icahn School of Medicine for their technical assistance and the Department of Pediatrics for their research support.

Funding

This study was funded by the following grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases: R01AI148963, R01AI127372, and R01AI151029

Footnotes

Supplementary Information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s10875-023-01635-z.

Ethics Approval All experimental studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to Participate Informed consent was provided by the patient for participation in the study.

Consent for Publication Informed consent was provided by the patient for publication of this report.

Declarations

Competing Interests DB is the founder and part owner of Lab11 Therapeutics. ABG has received honoraria as an advisory board member and consultant for Amgen, AnaptypsBio, Avotres Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dice Therapeutics, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Sanofi, UCB, and Xbiotech and has received research/educational grants from AnaptypsBio, Moonlake Immunotherapeutics AG, Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and UCB Pharma (all paid to Mount Sinai School of Medicine). SK has received consulting honoraria and research grants from Eli Lilly, Sanofi Regeneron, Incyte, UCB, Abbvie, Takeda, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Arcutis, and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Data Availability

All analyzed data is published in the manuscript. The raw data generated in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. No materials are applicable.

References

- 1.Tangye SG, et al. Human inborn errors of immunity: 2022 update on the classification from the International Union of Immunological Societies Expert Committee. J Clin Immunol 2022;42(7):1473–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Philips RL, et al. The JAK-STAT pathway at 30: much learned, much more to do. Cell. 2022;185(21):3857–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meuwissen ME, et al. Human USP18 deficiency underlies type 1 interferonopathy leading to severe pseudo-TORCH syndrome. J Exp Med 2016;213(7):1163–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gruber C, et al. Homozygous STAT2 gain-of-function mutation by loss of USP18 activity in a patient with type I interferonopathy. J Exp Med 2020;217(5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang X, et al. Human intracellular ISG15 prevents interferon-alpha/beta over-amplification and auto-inflammation. Nature. 2015;517(7532):89–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duncan CJA, et al. Severe type I interferonopathy and unrestrained interferon signaling due to a homozygous germline mutation in STAT2. Sci Immunol 2019;4(42) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marrakchi S, et al. Interleukin-36-receptor antagonist deficiency and generalized pustular psoriasis. N Engl J Med 2011;365(7):620–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hadjadj J, et al. Early-onset autoimmunity associated with SOCS1 haploinsufficiency. Nat Commun 2020;11(1):5341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thaventhiran JED, et al. Whole-genome sequencing of a sporadic primary immunodeficiency cohort. Nature. 2020;583(7814):90–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liau NPD, et al. The molecular basis of JAK/STAT inhibition by SOCS1. Nat Commun 2018;9(1):1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korholz J, et al. One gene, many facets: multiple immune pathway dysregulation in SOCS1 haploinsufficiency. Front Immunol 2021;12:680334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee PY, et al. Immune dysregulation and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) in individuals with haploinsufficiency of SOCS1. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2020;146(5):1194–1200 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Michniacki TF, et al. SOCS1 Haploinsufficiency presenting as severe enthesitis, bone marrow hypocellularity, and refractory thrombocytopenia in a pediatric patient with subsequent response to JAK inhibition. J Clin Immunol 2022;42(8):1766–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hale RC, et al. Phenotypic variability of SOCS1 haploinsufficiency. J Clin Immunol 2023;43(5):902–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jordan CT, et al. PSORS2 is due to mutations in CARD14. Am J Hum Genet 2012;90(5):784–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res 2010;38(16):e164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gruber CN, et al. Complex autoinflammatory syndrome unveils fundamental principles of JAK1 kinase transcriptional and biochemical function. Immunity. 2020;53(3):672–684 e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alexander WS, et al. SOCS1 is a critical inhibitor of interferon gamma signaling and prevents the potentially fatal neonatal actions of this cytokine. Cell. 1999;98(5):597–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Celakovska J, et al. Evaluation of leukocytes, B and T lymphocytes, and expression of CD200 and CD23 on B lymphocytes in patients with atopic dermatitis on dupilumab therapy-pilot study. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2023;13(5):1171–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wechsler ME, et al. Effect of dupilumab on blood eosinophil counts in patients with asthma, chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, atopic dermatitis, or eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2022;10(10):2695–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang Y, et al. Dynamics of adaptive immune cell and NK cell subsets in patients with ankylosing spondylitis after IL-17A inhibition by secukinumab. Front Pharmacol 2021;12:738316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Losman JA, et al. Cutting edge: SOCS-1 is a potent inhibitor of IL-4 signal transduction. J Immunol 1999;162(7):3770–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hebenstreit D, et al. IL-4 and IL-13 induce SOCS-1 gene expression in A549 cells by three functional STAT6-binding motifs located upstream of the transcription initiation site. J Immunol 2003;171(11):5901–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Del Bel KL, et al. JAK1 gain-of-function causes an autosomal dominant immune dysregulatory and hypereosinophilic syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017;139(6):2016–2020 e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharma M, et al. Human germline heterozygous gain-of-function STAT6 variants cause severe allergic disease. J Exp Med 2023;220(5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang M, et al. Variants in the 5q31 cytokine gene cluster are associated with psoriasis. Genes & Immunity. 2007;9(2):176–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang M, et al. Gain-of-function mutation of card14 leads to spontaneous psoriasis-like skin inflammation through enhanced keratinocyte response to IL-17A. Immunity. 2018;49(1):66–79 e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All analyzed data is published in the manuscript. The raw data generated in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. No materials are applicable.