Abstract

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR)-interacting protein (AIP) is a ubiquitously expressed, immunophilin-like protein best known for its role as a co-chaperone in the AhR-AIP-Hsp90 cytoplasmic complex. In addition to regulating AhR and the xenobiotic response, AIP has been linked to various aspects of cancer and immunity that will be the focus of this review article. Loss-of-function AIP mutations are associated with pituitary adenomas, suggesting that AIP acts as a tumor suppressor in the pituitary gland. However, the tumor suppressor mechanisms of AIP remain unclear, and AIP can exert oncogenic functions in other tissues. While global deletion of AIP in mice yields embryonically lethal cardiac malformations, heterozygote, and tissue-specific conditional AIP knockout mice have revealed various physiological roles of AIP. Emerging studies have established the regulatory roles of AIP in both innate and adaptive immunity. AIP interacts with and inhibits the nuclear translocation of the transcription factor IRF7 to inhibit type I interferon production. AIP also interacts with the CARMA1-BCL10-MALT1 complex in T cells to enhance IKK/NF-κB signaling and T cell activation. Taken together, AIP has diverse functions that vary considerably depending on the client protein, the tissue, and the species.

Keywords: aryl hydrocarbon receptor-interacting protein (AIP), aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), chaperones, immunity, pituitary adenoma, cancer

Chaperone proteins serve an important role in cellular and biological processes as they function to stabilize, maintain the physiological structure, and regulate the subcellular localization of their client proteins (1, 2). For example, the FK506 binding proteins (FKBP), a subfamily of the immunophilins, regulate steroid receptor signaling, and the heat shock response. They bind to and mediate the action of the immunosuppressant drugs cyclosporine, FK506, and rapamycin (3, 4). FKBPs display peptidyl propyl cis-trans isomerase (PPIase) activity and possess tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) domains, 34 amino acid repeats that form a primarily hydrophobic alpha-helical structure that assists in protein-protein interaction (4, 5).

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR)-interacting protein (AIP, also known as XAP2, ARA9, and FKBP37) is a highly conserved, ubiquitously expressed, cytoplasmic 330-amino acid protein that shares 52% structural similarity with FKBP12 (3, 6, 7, 8). AIP has an amino-terminal PPIase domain that is linked to three TPRs through a 12-amino acid hinge and ends in a terminal α-helix (4, 9). While AIP is similar to FKBPs, it does not bind FK506 or rapamycin and does not display any PPIase-like activity (10, 11, 12).

AIP has been identified as a chaperone for over 20 different proteins (13) but was initially discovered as a binding partner in a yeast 2-hybrid screen of the hepatitis B virus X protein (14). Subsequently, a yeast 2-hybrid screen that used AhR as bait identified the same protein which was named Ah receptor-associated protein (ARA9) (3). While most studies have focused on how AIP modulates the signal transduction pathway of AhR, others have identified novel roles of AIP based on its various other binding partners.

AIP has been proposed to function as a tumor suppressor gene, and mutations in AIP are correlated with 30% of familial isolated pituitary adenomas (FIPAs) and 3% of cases of sporadic pituitary adenomas (15). Most of the pituitary adenomas have a young age of onset and secrete growth hormone (GH) only or both GH and prolactin. These tumors tend to be more aggressive, with large and invasive pituitary adenomas that display resistance to somatostatin analog treatment (7). In addition to endocrine tumors, AIP mutations have also been associated with several other types of cancer, including colorectal cancer, gastric carcinoma, pancreatic carcinoma, and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (16, 17, 18, 19).

Further investigation into the pathogenicity of AIP mutations in these cancers suggests that AIP can function as either a tumor suppressor or an oncogene depending on the type of cancer (20). These and other scientific studies have determined that the roles of AIP are most likely cell-, tissue-, and species-specific. In this review, we will discuss the canonical functions of AIP as a chaperone protein for its various binding partners, its functions in murine models, the oncogenic and tumor suppressor functions of AIP in different tumors, and its newly discovered roles in modulating the immune system.

AIP regulates the stability of the AhR cytosolic complex

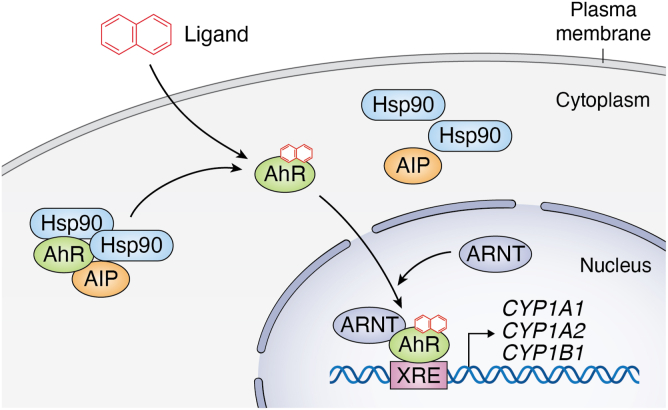

The AIP–AhR interaction has been the focus of many studies. AhR is a ligand-activated transcription factor that mediates the metabolism of several environmental toxins, including polyaromatic hydrocarbons and polyhalogenated aromatic hydrocarbons. In its inactive state, AhR resides in the cytoplasm as part of a complex with the heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) dimer, AIP, and p23 (1). Along with Hsp90, AIP stabilizes AhR in its inactive state and prevents AhR proteasomal degradation. Upon ligand binding (the most potent of which is 2,3,7,8-tetrachlordibenzo-p-dioxin, TCDD), AhR sheds its chaperone proteins and moves into the nucleus (8). AhR then interacts with the AhR nuclear translocator (ARNT) and binds to the xenobiotic response element (XRE) in gene promoters to induce the expression of genes regulating the xenobiotic response, including the cytochrome P450 family of metabolic enzymes (Fig. 1) (3).

Figure 1.

AhR activation pathway. Inactivated AhR is found in the cytoplasm, bound to AIP and a dimer of Hsp90. Upon ligand binding, AhR undergoes a conformational change and sheds its chaperone proteins. AhR then translocates to the nucleus where it binds to the AhR nuclear translocator (ARNT), and xenobiotic response elements (XREs) in gene promoters to upregulate the expression of AhR target genes.

The AIP-AhR-Hsp90 complex

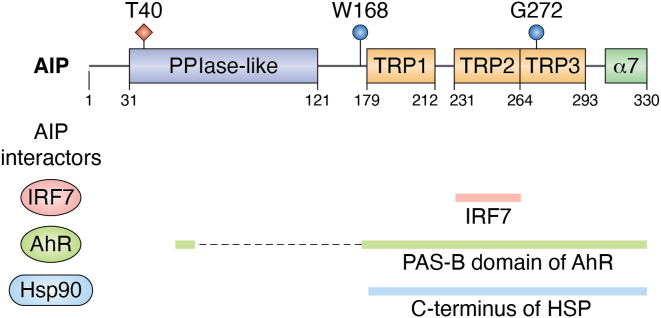

AIP is a core component of the AhR cytoplasmic complex, along with Hsp90 (3). Within the complex, AIP interacts with both AhR and Hsp90, suggesting that AIP acts as a brace connecting the two proteins (9). The TPR domains within the C-terminus of AIP are most critical for the Hsp90 and AhR interactions (Fig. 2) (6, 8, 11, 21, 22). In particular, the distal C-terminus (amino acids 311–330) was critical for AIP binding to both AhR and Hsp90 (22). Site-directed mutagenesis studies revealed that AIP Gly272 was necessary for binding to AhR and Hsp90 (21). The recently resolved Cryo-EM structure of the AhR-AIP-Hsp90 complex provided further insight into the interactions (9). Lys66-Lys69 within the PPIase domain, the helix α2-α3 loop within TPR1, and Trp168 of the linker region were identified as the key regions underlying AIP interaction with AhR (9). Although it was thought that the N-terminus of AIP was flexible and did not participate in binding to AhR, cryo-EM analysis revealed that the deletion of the N-terminus of AIP compromised its role in regulating the subcellular location of AhR (22).

Figure 2.

Schematic of AIP structure. The peptidyl propyl cis-trans isomerase (PPIase) and tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) domains and the corresponding amino acids are indicated. The areas of AIP that interact with AhR, Hsp90, and IRF7 are indicated in the lines below. The amino acids that are essential for AIP interaction with AhR are highlighted in blue. The amino acid (Thr40) that is phosphorylated by TBK1 and increases AIP interaction with IRF7 is indicated in red.

AIP has been shown to bind to the carboxyl (C)-terminus of Hsp90 via its TPR domain, and mutation of AIP Lys266 to alanine abolished the binding to Hsp90 (8, 11). AIP interaction with AhR is mediated by the Fα helix in the PAS-B domain (C-terminal; amino acids 380–491) and the 40 amino acids that connect the PAS-B domain to the C-terminal transactivation domain (6, 8, 9, 23). Although several residues (i.e., I277, S276, E279, R218) of AhR when mutated to alanine reduced the binding to AIP, other residues including Phe404, Phe406, and Tyr414 were more critical for AIP binding (9).

AIP as a chaperone for AhR

A number of studies have investigated the biochemical function of AIP within the AhR-Hsp90-AIP cytoplasmic complex. AIP was found to stabilize the unliganded structure of AhR, preventing the ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation of AhR (1, 7, 8, 9). Consistently, AIP overexpression leads to a two-fold increase in AhR protein levels (5, 23). Therefore, AIP plays a key role as a chaperone in the stabilization of AhR.

AIP was also found to be critical for the cytoplasmic localization and retention of AhR. When overexpressed alone, AhR was found in the nucleus; however, when co-expressed with AIP, AhR was cytoplasmic (24). Furthermore, several studies have shown that AIP delays TCDD-induced nuclear translocation of AhR. AIP was proposed to cause a conformational change in inactive AhR that impedes importin-β binding to the nuclear localization signal of AhR, which can be reversed with ligand binding (5, 7, 8, 23, 25).

Overexpression of AIP was shown to increase the transcriptional response of AhR to dioxin, increasing both the maximal response and the sensitivity of the receptor (6, 8, 26). AIP could also increase the activity of AhR in a dose-dependent manner in a luciferase reporter assay (4).

Other studies examined endogenous levels of AIP and/or AhR in contrast to the previously described overexpression experiments. In Hepa1 cells, AIP expression did not affect endogenous levels of AhR and had minimal to no effect on AhR subcellular localization (25). An AhR point mutant (Tyr408A) was generated that impaired binding to AIP but did not affect binding to ligand or Hsp90. It was found that AIP was essential for the cytoplasmic localization of AhR but repressed the transcriptional activation of AhR (27). Other studies examined species- and cell-specific differences in the regulation of AhR by AIP (28). In comparing mouse and human AhR, it was found that human and mouse AhR proteins exhibited differences in their subcellular localization and nucleocytoplasmic shuttling and regulation by AIP, and AIP remained in a complex with ligand-bound human AhR during shuttling to the nucleus (29).

Other AIP client proteins

In addition to AhR and Hsp90, AIP has been found to interact with and regulate the function of many of its client proteins (Table 1). AIP binds to multiple heat shock proteins and receptors, including the glucocorticoid receptor (GR), estrogen receptor alpha (ERα), and thyroid receptor β1 (TRβ1), and regulates the functions of these hormone receptors (30, 31, 32). The interactions of AIP with the receptor tyrosine kinase RET (rearranged during transfection), G proteins, and phosphodiesterases were shown to influence cell proliferation and cAMP levels with implications for pituitary tumorigenesis (33, 34, 35, 36, 37). AIP also interacts with and enhances the stability of survivin, a member of the inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) family, thus providing a potential mechanism for AIP in tumorigenesis (38, 39). AIP may also potentially interact with the cardiac-specific kinase TNNI3K (cardiac troponin I-interacting kinase), which could contribute to the cardiac malformations that occur in AIP knockout mice (13, 40).

Table 1.

Client proteins of AIP

| Client protein | Class of protein | Functional? | Effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hsp90 | Heat shock protein | No | N/A | (1, 11) |

| Hsc70 | Heat shock protein | No | N/A | (94) |

| HSPA5 | Heat shock protein | Not studied | N/A | (84) |

| HSPA9 | Heat shock protein | Not studied | N/A | (84) |

| HSPA8 | Heat shock protein | Not studied | N/A | (94) |

| HSP90AA1 | Heat shock protein | Not studied | N/A | (50) |

| HSP90AB1 | Heat shock protein | Not studied | N/A | (50) |

| NME1 | Cytoskeleton | Not studied | N/A | (84) |

| TUBB1 | Cytoskeleton | Yes | Upregulated with AIP mutants | (84) |

| TUBB2B | Cytoskeleton | Yes | Upregulated with AIP mutants | (84) |

| AhR | Cytosolic Receptor | Yes | Expression, localization, and transcriptional activity | (1, 3, 5, 6, 8, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29) |

| PDE4A5 | PDE | Yes | Inhibitory | (36) |

| PDE2A3 | PDE | No | N/A | (35) |

| ERα | Nuclear Receptor | Yes | Inhibits transcriptional activity | (31) |

| GR (via Hsp90) | Nuclear Receptor | Yes | Cytosolic retention | (7, 12) |

| PR | Nuclear Receptor | Yes | Reduced transcriptional activity | (7) |

| PPARα | Nuclear Receptor | Yes | Inhibitory | (83, 95) |

| TRβ1 | Nuclear Receptor | Yes | T3 independent for TR β1 | (32) |

| RET | Transmembrane Receptor | Yes | RET prevents AIP-survivin interaction | (33, 34) |

| EGFRa | Transmembrane receptor | No | N/A | (96) |

| Gαq | G protein | No | N/A | (37) |

| Gα13 | G protein | Yes | Inhibits AIP-AHR interaction | (37) |

| PRKAR1A | Protein kinase | Yes | Inhibitory | (36) |

| PRKACA | Protein kinase | Yes | Inhibitory | (36) |

| PDE4A5 | PDE | Yes | Inhibitory | (36) |

| PDE2A3 | PDE | No | N/A | (35) |

| X-protein of HBV | Viral Protein | Yes | Inhibited transcriptional activity | (14) |

| EBNA-3 | Viral Protein | Yes | Nuclear Translocation | (49, 97) |

| IRF7 | Immune | Yes | Cytosolic Retention | (52, 53) |

| BCL6 | Immune | Yes | Prevents degradation | (19) |

| CARMA1 | Immune | Yes | CBM complex formation | (57) |

| SOD1 | Metalloproteins | Not studied | N/A | (84) |

| AGO1 | RISC endonuclease | Not studied | N/A | (50) |

| LAMP1 | Glycoprotein | Not studied | N/A | (98) |

| LRP1B | Lipoprotein | Not studied | N/A | (99) |

| TOM20 | Mitochondrial | Yes | Promotes preproteins into mitochondria | (39, 94) |

| Survivin | Mitochondrial | Yes | Stabilizes and promotes mitochondrial transport | (38, 39) |

| HSPA9 | Mitochondrial | Not studied | N/A | (98) |

| TNNI3Ka | Cardiac | No | N/A | (40) |

Abbreviations: AGO1, Argonaute RISC catalytic component 1; EBNA-3, Epstein-Barr Virus Nuclear Antigen 3; EGFR, epidermal growth factor; ERα, estrogen receptor-alpha; GR, Glucocorticoid receptor; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HSPA8, Heat shock cognate 71 kDa protein; HSPA9, stress-70 protein; HSP90AA1, heat shock protein 90-alpha; HSP90AB1, heat shock protein 90-beta; IRF7, interferon regulatory factor 7; LAMP1, lysosome-associated membrane glycoprotein 1; LRP1B, Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1B; NME1, NMe/NM23 nucleoside diphosphate kinase 1; PPARα, Peroxisome Proliferator-activated receptor alpha; PR, Progesterone receptor; RET, Rearranged during transfection; SOD1, superoxide dismutase 1; TR β1, Thyroid hormone receptor-β1.

Indicates further confirmation needed to validate the interaction.

The physiological roles of AIP learned from murine models

Cardiovascular development

Mice with a null allele of AIP are not viable with embryonic lethality starting as early as e10 and no embryos surviving past e18.5 (41). These embryos had severe cardiac malformations, including double outlet right ventricle (both the pulmonary artery and the aorta arise from the right ventricle), ventricular septal defect, and pericardial edema. The embryos also exhibited a decreased number and caliber of blood vessels in yolk sacks, petechiae (pinpoint, round spots under the skin that are caused by bleeding), hemorrhaging, and open abdominal cavities (omphalocele) (41). These defects illustrate the critical roles of AIP in cardiac development, which is independent of its role as a chaperone protein for AhR. Mice with a hypomorphic allele of AIP (Ara9fxneo), which express ∼10% of AIP compared to the expression in wild-type (WT) mice, were also generated (42). Aipfxneo/fxneo and Aip+/− mice had significantly decreased liver weights compared to Aip+/+ and Aip+/fxneo mice. These mice developed patent ductus venous (DV), which results in a decreased blood supply to the liver, a phenotype also exhibited by Ahr and Arnt null mice (42). Therefore, low levels of AIP expression can rescue the lethal impairment of heart development that occurs in Aip null mice, but this results in diminished AhR signaling during development, thus phenocopying AhR−/− mice.

Hepatotoxicity

To determine the physiological roles of AIP in the liver, hepatocyte-specific Aip−/− mice were generated by crossing conditional Aipfx/fx mice with mice expressing a Cre transgene driven by the albumin (Alb) promoter (43). Despite a 60% reduction in AhR levels, Aip null hepatocytes had similar CYP1A1 and CYP1A2 expression compared to WT hepatocytes after mice were injected with dioxin. However, CYP1B1 expression in Aip null hepatocytes was reduced in response to dioxin, and mice lacking AIP in hepatocytes displayed resistance to dioxin-induced hepatotoxicity consisting of hepatocellular hydrophobic degeneration and focal inflammation with macrophages, lymphocytes, and necrotic cells (43).

Pituitary adenoma

Since germline mutations in AIP are associated with the development of pituitary adenomas, two different mouse models were used to investigate the role of AIP in pituitary tumorigenesis (44, 45). Raitila et al. (44) found that heterozygous Aip (Aip+/−) mice were significantly more prone to developing pituitary tumors, which were GH-secreting and displayed a more aggressive disease profile. They found that 78% (69/88) of Aip+/− mice developed at least one pituitary adenoma by 12 months of age, and some of these mice developed multiple tumors by 6 months of age. Of the 69 pituitary tumors in Aip+/− mice, 61 (88%) were GH-secreting. This is compared to 21% (12/58) of the Aip+/+ littermates by 12 months and most of these tumors (92.6%) were prolactinomas (44). However, in a subsequent study by an independent group, it was found that male Aip+/− mice did not develop pituitary adenomas up to the age of 12 months (15). Furthermore, Aip+/− mice did not exhibit gigantism/acromegaly (15). At 12 months of age, there was significantly higher total GH secretion in Aip+/− mice, but no other abnormalities of GH secretion. Somatotrophs from Aip+/− mice had an increased proliferative rate, but this was associated with pituitary hyperplasia rather than any neoplastic changes (15). The reason for the discrepancies between these two studies using the same mouse model is unknown but could be due to environmental factors.

To determine the role of the PKA pathway in AIP-dependent pituitary tumorigenesis, Aip+/− mice were crossed with Prkar1a (a regulatory subunit of PKA) heterozygote mice (46). Although Aip+/− mice displayed signs of acromegaly and elevated insulin-like growth factor 1 levels at 12 months of age, this was not observed in mice heterozygous for both Aip and Prkar1a (46). However, there were no signs of pituitary hyperplasia or tumorigenesis in either group of mice (46). Thus, AIP regulation of the PKA pathway appears to play an important role in GH secretion.

An independent study generated conditional knockout mice lacking Aip in pituitary somatotrophs (sAIPKO mice) (45). Differences in body weight and mean GH hormone levels were greater in the sAIPKO mice compared to WT mice, and the differences were greater between females than males. By 18 weeks of age, sAIPKO mice had enlarged pituitary glands and tumors were visible by 24 weeks, and by 30 weeks of age 80% of sAIPKO mice had tumors (45). Similar to pituitary adenomas in humans that are associated with loss of function AIP mutations and display increased tumor invasion and poor response to somatostatin analog treatment, sAIPKO mice had pituitary adenomas that were aggressive and treatment-resistant (45). The cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27 was cytosolic, rather than nuclear, and CDK4 (which mediates the G1-S transition) was perinuclear in siAIPKO pituitary tumors (45). Therefore, loss of somatotroph AIP disrupts the proper regulation of cell cycle regulators which could lead to hyperplasia and pituitary adenomatous transformation.

Functions of AIP in the immune system

Binding to viral proteins

Originally, AIP (then termed XAP2) was identified as a binding partner of the X protein of hepatitis B virus (HBV) (14). HBV X acts as a transcriptional activator and is thought to contribute to HBV-induced tumorigenesis (47). AIP binds to the N-terminus (amino acids 13–26) of the X protein, part of the regulatory domain that represses transactivation. The functional outcome of AIP binding to X is repression of the transcriptional activity of the X protein (14).

Epstein–Barr Virus (EBV) nuclear antigen-3 (EBNA-3) is an EBV-encoded nuclear antigen that is necessary for B-cell transformation and one of six nuclear antigens expressed in EBV immortalized lymphoblastoid cell lines (48). A yeast 2-hybrid screen conducted with EBNA-3 as bait using an EBV-transformed human lymphocyte cDNA library yielded AIP (XAP2) as an interacting partner of EBNA-3 (49). Interestingly, the subcellular localization of AIP is modulated by EBNA-3 since AIP is normally cytoplasmic but translocates to the nucleus upon EBNA-3 expression (49).

Innate immunity

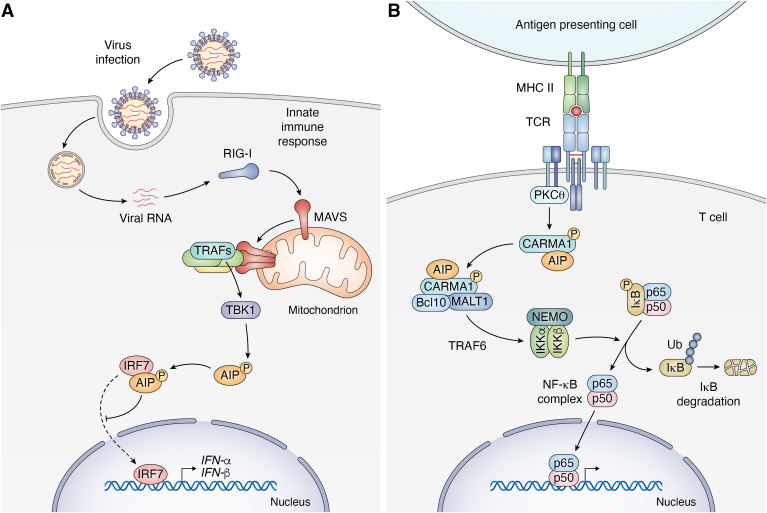

AIP was identified as a potential binding partner for the transcription factor interferon (IFN) regulatory factor 7 (IRF7) by a proteomics approach mapping the innate immune interactome following virus infection (50). IRF7 is known as the master regulator of type I IFN and is critical for immunity against virus infection (51). The binding of AIP and IRF7 was validated and shown to increase during virus infection (52). The second TPR domain of AIP (amino acids 231–264) mediates the interaction with the virus-activated domain of IRF7 (Fig. 2). AIP functions as an inhibitor of type I IFN production by sequestering IRF7 in the cytoplasm and blocking virus-induced IRF7 nuclear translocation (52, 53) (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

AIP regulation of innate and adaptive immune signaling pathways.A, in the RIG-I-like receptor (RLR) pathway, RIG-I senses 5′-triphosphate double-stranded RNA genomes from RNA viruses, and activates the mitochondrial adaptor MAVS (mitochondrial anti-viral signaling molecule). Activated MAVS forms large prion-like aggregates that recruit TRAF E3 ubiquitin ligases (TRAF2, 3, 5, 6) leading to TBK1 activation. TBK1 phosphorylates AIP at Thr40, which serves as a molecular switch for AIP binding to IRF7 and preventing its nuclear translocation. The AIP-IRF7 interaction suppresses the expression of type I IFNs and interferon-stimulated genes. B, following T-cell receptor activation, PKCθ is activated and phosphorylates CARMA1. AIP interacts with and stabilizes CARMA1 in its open conformation, thus enhancing the complex formation of CARMA1 with BCL10 and MALT1. The activated CBM complex triggers IKK and NF-κB signaling.

Our recent study demonstrated that AIP is phosphorylated by the kinase TBK1 at Thr40 (Fig. 3) and this acts as a molecular switch to promote the interaction between AIP and IRF7 (53). TBK1 is activated by virus-triggered nucleic acid sensing pathways and therefore plays important roles in both the induction and inhibition of type I IFN activation (54). An AIP T40E phospho-mimetic exhibited enhanced binding to IRF7 and was associated with less type I IFN expression during RNA virus infection (53). Conversely, an AIP phospho-mutant T40A was impaired for IRF7 binding which resulted in increased type I IFN expression and decreased viral replication (53).

Adaptive immunity

Following T cell receptor co-stimulation with CD28, the signaling scaffold protein CARMA1 (also known as CARD11) is phosphorylated by protein kinase C theta (PKCθ) (55). CARMA1 then forms a complex with BCL-10 and MALT1 (known as the CBM complex), which then activates IκB kinase (IKK) and NF-κB signaling (56). A yeast 2-hybrid screen using the C-terminus of CARMA1 as bait followed by co-immunoprecipitation experiments revealed that the PPI domain of AIP binds to the C-terminus of CARMA1 (57). AIP knockdown in T cells decreases the CARMA1-BCL10 interaction following T cell receptor activation, leading to decreased IKK activity, downstream NF-κB signaling, and IL-2 expression and secretion (57). This indicates that AIP is necessary for proper CBM complex formation, and acts as a positive regulator for NF-κB and NF-AT signaling in activated T cells (Fig. 3B).

Within germinal centers, B cells undergo rapid proliferation, class switch recombination, somatic hypermutation, and affinity maturation to generate effective adaptive immune responses. BCL6 is a transcription factor and master regulator of the germinal center B cell phenotype, repressing apoptotic proteins and allowing for continued proliferation of B cells within the dark zone of germinal centers (58). BCL6 can undergo proteasomal degradation triggered by the E3 ubiquitin ligase FBXO11; however, the de-ubiquitinating enzyme UCHL1 binds to BCL6 and protects it from degradation (19, 59). AIP can interact with BCL6, UCLH1, and FBXO11 and displaces FBXO11 from the complex while promoting UCLH1 binding to BCL6, leading to the de-ubiquitination and stabilization of BCL6 (19). Knockout of AIP resulted in decreased BCL6 expression and reduced cell viability of a diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) cell line (19). Therefore, AIP acts as a positive regulator of BCL6 and may be involved in the development of DLBCL.

AIP in tumorigenesis

Loss of function AIP mutations have widely been associated with pituitary adenomas, suggesting that AIP is a tumor suppressor in the pituitary gland (7). However, AIP can function as an oncogene in DLBCL and various cancers of the gastrointestinal tract (17, 18, 19, 20). These studies highlight cell-specific roles of AIP in either the prevention or promotion of tumorigenesis.

AIP mutations are associated with endocrine tumors

Pituitary adenomas are relatively common tumors (prevalence of 1:1000), accounting for about 15% of intracranial tumors (60). While pituitary adenomas are benign, they can be hormone-secreting functional tumors and large, invasive tumors leading to mass effect and compression complications (61). While most pituitary adenomas arise from sporadic mutations, approximately 5% are due to inherited mutations and are considered familial isolated pituitary adenomas (FIPAs). These can be caused by germline mutations in MEN1, GNAS, or PRKAR1 leading to multiple endocrine neoplasia type I (MEN1), McCune-Albright syndrome, and Carney complex, respectively (62). However, mutations in AIP, located only 2.4 megabases from the MEN1 gene locus on chr11q13 (63, 64), have been associated with 15% to 30% of FIPA cases and 1% to 3% of sporadic pituitary adenomas (13, 65). Patients with germline AIP mutations have a male predominance and have a younger onset of pituitary adenomas (66). These pituitary adenomas are usually functional, secreting GH (80%) or both GH and prolactin. Pituitary tumors with AIP mutations tend to be larger, more invasive, and can present with pituitary apoplexy (13, 67, 68). These tumors are usually resistant to octreotide, a somatostatin analog that is the standard treatment for functional pituitary adenomas (67).

The various AIP mutations associated with pituitary adenomas are listed in Table 2. A premature stop codon at Arg304 is the most common mutation, followed by R271W and R16H (69, 70). While there is a small founder effect for R304 in central Italy, R304 is located near a CpG island and is largely considered a hot spot mutation (69). The AIP R304X variant was shown to be less stable than WT AIP and more likely to be ubiquitinated by the F-box-containing protein, FBX03 (71). Most AIP mutations often display loss of heterozygosity, low immunostaining, and/or low mRNA levels of AIP (72). In fact, low AIP expression was a stronger predictor of cell proliferation and tumor invasiveness than traditional measures like Ki67 (73). In addition, the half-life of AIP variants directly correlated with the age of diagnosis in pituitary adenoma patients where short AIP variant half-life was observed in patients that were diagnosed at a younger age (71). Taken together, these collective studies suggest that loss of AIP is associated with pituitary tumorigenesis; however, the penetrance of AIP mutations is about 30% (13, 65).

Table 2.

Germline AIP mutations found in patients with pituitary adenomas

| Mutation |

Tumor characteristics |

References | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene mutation | Exon | Predicted protein | Protein domain | LOH | Onset | Size | Hormone status | Response to SSA | |

| Loss of Function Mutations | |||||||||

| Nonsense Mutations | |||||||||

| c.40 C>T | 1 | Q14X | PPIase | Yes | Young | Macro | GH, GH/PRL, PRL, NFPA | (60, 61, 100, 101, 102) | |

| c.64 C>T | 1 | R22X | PPIase | Young | Macro | GH | (100) | ||

| c.70G>T | 1 | E24X | PPIase | Young | Macro, Micro | GH | (76) | ||

| c.241 C>T | 2 | R81X | PPIase | Young | Macro | GH | (76) | ||

| c.424 C>T | Q142X | PPIase/TPR1 | Young | Macro | GH, PRL | (70, 103) | |||

| c.490 C>T | 3 | Q164X | PPIase/TPR1 | Young | Macro | GH/PRL | (64) | ||

| c.550 C>T | Q184X | TPR1 | Young | Macro | GH | (70) | |||

| c.601A>T | 4 | K201X | TPR1 | Young | Macro | GH, NFPA | (70, 104) | ||

| E216X | TPR1/TPR2 | Yes | Young | Macro | GH | (105) | |||

| c.649C>T | 4 | Q217X | TPR1/TPR2 | Young | Macro∗ | GH/PRL | (103) | ||

| c.662dupC | 4 | E222X | TPR2 | Young | Macro | GH | (105) | ||

| c.685C>T | 5 | Q229X | TPR2 | Young | Macro | GH (with papillary thyroid cancer) | Resistant | (106) | |

| c.715C>T | 5 | Q239X | TPR2 | Young | Macro | GH | (103) | ||

| c.721A>T | 5 | K241X | TPR2 | Young | Macro | PRL | (61, 70) | ||

| c.783C>G | 5 | Y261X | TPR2 | Young | Macro | GH | (104) | ||

| c.804A>C | 6 | Y268X | TPR3 | Young | Macro | GH, PRL | (61, 107) | ||

| c.910C>T | 6 | R304X | α7 | Yes | Young | Macro | GH, GH/PRL, PRL | (69, 72, 86, 101, 103, 104, 108, 109) | |

| c.945C>T | 6 | Q315X | α7 | Yes | Young | Macro∗ | GH, GH/PRL, | (110) | |

| Frameshift Mutation leading to truncated protein | |||||||||

| c.3_4insC | 1 | R2fsX3 | PPIase | Young | Macro, Micro | GH, NFPA | (70) | ||

| c.74_81del ins7 | 1 | L25PfsX130 | PPIase | Young | Macro, Micro | GH, GH/PRL, PRL | (64) | ||

| c.88_89delGA | 1 | D30T.fsX14 | PPIase | Young | Macro | NFPA | (70) | ||

| c.249G>T | 2 | Q82fsX7 | PPIase | Yes | Young | Macro | GH, PRL | (70, 72) | |

| c.244_248del GAAGG |

2 | Q83AfsX15 | PPIase | Young | Macro | GH/PRL | (64) | ||

| c.286_287 delGT |

3 | V96PfsX31 | PPIase | Young | Macro | GH | (69) | ||

| c.338inc ACCC |

3 | P114fsX | PPIase | Young | Macro | GH | (70) | ||

| c.350delG | 3 | G117A.fsX39 | PPIase | Young | Macro | GH, PRL | (61, 70, 86, 104) | ||

| c.404delA | 3 | H135L.fsX19 | PPIase | Young | Macro | GH | (64) | ||

| c.500delC | P167HfsX3 | TPR1 | UNK | UNK | UNK | (70) | |||

| c.517_521del GAAGA |

4 | Q174fs21X | TPR1 | Yes | Young | Macro∗ | GH, GH/PRL | Resistant | (72, 103, 111) |

| c.543delT | 4 | L181fsX13 | TPR1 | Young | Macro, Micro | GH, PRL, NFPA | (70) | ||

| c.542delT | 4 | I182S.fsX12 | TPR1 | (60, 112) | |||||

| c.752delT | 5 | L251R.fsX52 | TPR2 | No | Young | Macro | ACTH | (104) | |

| c.824_825insA | 6 | H275Q.fsX12 | TPR3 | Young | N/A | GH | (60, 100, 112) | ||

| c.854_857del AGGC |

6 | Q285.fsX16 | TPR3 | Young | Macro∗ | GH, GH/PRL | Partial | (72, 103) | |

| c.919insC | 6 | Q307fsX104 | TPR3/α7 | Young | Macro | GH, PRL | (70) | ||

| Missense Mutation | |||||||||

| c.26G>A | 1 | R9Q | N-term | Young | Macro, Micro | GH, PRL, ACTH | (104, 113) | ||

| c.47G>A | 1 | R16H | N-term | No | Elderly | Macro∗ | GH, ACTH | Resistant | (103, 113, 114, 115) |

| V49M | PPIase | No | Young | GH | (113, 116) | ||||

| W73M | PPIase | Young | GH | (117) | |||||

| K103R | PPIase | Young | Micro | ACTH | (91, 113) | ||||

| c.512C>T | 4 | T171I | TPR1 | Young | Macro∗ | GH, GH/PRL | (78) | ||

| c.713G>A | 5 | C238Y | TPR2 | Yes | Young | Macro | GH | (76) | |

| c.769A>G | I257 | TPR2 | Young | Macro | TH | (64, 70) | |||

| G272D | TPR3 | Elderly | GH | (84) | |||||

| c.896C>T | 6 | A299V | TPR3/α7 | Young | Micro | GH, PRL | (60, 64, 118) | ||

| Promoter and Splice Site Mutations | |||||||||

| -270_-269 CG > AA; -220 G>A | 5′UTR | Reduced expression | Yes | Young | Macro | GH | (64) | ||

| c.2T>C | 1 | No protein | Young | Macro | GH | (70, 86) | |||

| c.807C>T | 6 | F269, loss of exon6 | Young | GH | (64, 76) | ||||

| Deletions and Insertions | |||||||||

| 100-1025_279+ 375del | (ldel) 2 | delA34_K39 | PPIase | Young | Macro, Micro | GH/PRL/ACTH, GH/PRL | (70) | ||

| 1104_-109_279 +578 | (del) 1, 2 | Exon1 and 2 deletion | PPIase | Young | Macro | GH | (70) | ||

| Full gene | Full protein loss | Young | Macro | GH | (70) | ||||

| c.794_823dup | 6 | Ins274 | TPR3 | Young | GH | (76) | |||

| Function is conserved | |||||||||

| Missense Mutations | |||||||||

| c.563G>A | 4 | R188Q | TPR1 | Young | Micro | PRL | (104) | ||

| c.721A>G | 5 | K241E | TPR2 | Yes | Young | Macro∗ | GH, PRL, NFPA | Responsive | (72, 103) |

| c.811C>T | 5 | R271W | TPR3 | Young | Macro, Micro | GH, GH/PRL, PRL | (61, 103) | ||

| E293G | TPR3 | (100) | |||||||

| E293V | TPR3 | Elderly | GH | (119) | |||||

| c.911G>A | 6 | R304Q | α7 | Young | ACTH | (60, 76) | |||

| Deletions (in frame) | |||||||||

| c.66-71del AGGAGA |

1 | delG23_E24 | N-term | Yes | Young | Macro | GH | (60, 70) | |

| c.138_161del24 | 1 | delG47_R54 | PPIase | Young | Macro | GH | (70) | ||

| c.878_879 AG>GT |

6 | E293G | TPR3 | Yes | Young | GH | (60) | ||

| 880-891delCTG GCCCAGCC |

6 | L294_A297del | TPR3 | Yes | Young | GH | (60) | ||

| Intron and Splice Site Mutations | |||||||||

| IVS1-1G>C; c100-18C>T | Intron2 | UNK | Young | Macro∗ | PRL | Partial | (61, 100) | ||

| c.469-1 G>A | Intron3 | UNK | Young | Macro | PRL | (102, 120) | |||

| c.469-2 A>G | Intron3 | UNK | Young | Macro | GH/PRL | (70, 100, 104, 120) | |||

| Silent Mutations | |||||||||

| c.516C>T | 4 | D172D | PPIase/TPR1 | GH, PRL, NFPA | (114) | ||||

| c.591G>A | 5 | E197E | TPR1 | Young, Elderly | Macro | GH | (70) | ||

| c.807C>T | 6 | F269F | TPR3 | Young | Macro | GH, PRL, NFPA | (121) | ||

| Unknown Effect on Function | |||||||||

| Missense Mutations | |||||||||

| I13N | N-term | Yes | Young | GH | (113, 122) | ||||

| c.166C>A | 1 | R56C | PPIase | Young | Macro | PRL | (61, 70) | ||

| c.174G>C | 2 | K58N | PPIase | Young | Macro∗ | PRL | Partial | (61, 104) | |

| L70M | PPIase | Young, Elderly | Macro | GH/PRL, PRL | (61, 70) | ||||

| c.250G>A | 2 | E84K | PPIase | Young | Macro | GH/PRL | (70) | ||

| R128H | PPIase/TPR1 | No | Young | Macro | GH | (72) | |||

| Q164R | PPIase/TPR1 | Young | GH | (72) | |||||

| c.509T>C | 4 | M170T | PPIase/TPR1 | Young | Macro | GH | (104) | ||

| V195A | TPR1 | Yes | Young | Macro∗ | PRL | Resistance | (61, 72, 123) | ||

| Q228K | TPR2 | Yes | Young | Macro | GH | (105, 124) | |||

| c.718T>C | 5 | C240R | TPR2 | Young | Macro | GH | (70) | ||

| c.803A>G | 6 | Y268C | TPR3 | Young | Macro | PRL | (61, 70) | ||

| A277P | TPR3 | Yes | Young | Macro | GH/PRL | (72) | |||

| c.871G>A | 6 | V291M | TPR3 | Young | Macro | GH/PRL | (70) | ||

| c.872T>A | 6 | V291E | TPR3 | Young | Macro | GH/PRL | (104) | ||

| R304N | α7 | Young | Macro | GH. ACTH | (100) | ||||

| Q307R | α7 | ACTH | (124) | ||||||

| R314W | α7 | Young | GH | (84) | |||||

| c.974G>A | R325Q | α7 | Yes | Young | Macro | PRL | (104) | ||

| Deletion, Duplication, Frameshift, and Insertion Mutations | |||||||||

| c.138_161del24 | 2 | G47_R54del | PPIase | Young | Macro∗ | GH | (103) | ||

| c.286-287delGT | 3 | P46fs | PPIase | GH, GH/PRL | (116) | ||||

| c.542delT | 4 | UNK | Young | GH | (60) | ||||

| c.742_744del TAC | 5 | Y248del | TPR2 | Yes | Young | Macro | GH | (121) | |

| L294_A297del | TPR3 | (100) | |||||||

| c.805_825dup | 6 | F269_H275dup | TPR3 | Young | Macro | GH/PRL | (86, 104) | ||

| Mutations in non-coding regions | |||||||||

| c.220G>A | Intron1 | UNK | Young | GH | (76) | ||||

| c.279_269 CG>AA | Intron1 | UNK | Young | GH | (76) | ||||

| IVS2 279+ 23C>T | Intron2 | UNK | Young | Macro | GH/PRL | (72) | |||

| IVS2-1G>C | Intron2 | UNK | Young | GH | (60) | ||||

| IVS3 468+ 16G>T | Intron3 | UNK | Yes | Young | Macro | GH | (72) | ||

| IVS3 468 +15C>T | Intron3 | UNK | Yes | Young | Macro | GH/PRL/ACTH | (72) | ||

| IVS3-1 G>A | Intron3 | UNK | GH | (100) | |||||

| IVS3-2 A>G | Intron3 | UNK | (100) | ||||||

| 3′UTR | UNK | NFPA | (114) | ||||||

Young is defined as <50 years old at age of diagnosis; Macro is defined as macroadenoma (>10 mm); Macro∗ indicates a macroadenoma with invasive features; Micro is defined as microadenoma (<10 mm).

Abbreviations: α7, terminal alpha-7 helix; ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone leading to Cushing’s disease; GH, growth hormone; NFPA, non-functioning pituitary adenoma; PPIase, peptidyl propyl cis-trans isomerase domain; PRL, prolactin; TH, thyroid hormone; TPR, tetratricopeptide repeat.

Investigations into AIP mutations in other endocrine tumors revealed that AIP is not associated with MEN1 and has little to no role in the genesis of non-medullary thyroid cancer (74, 75). Screening of 132 parathyroid carcinomas revealed the AIP R304Q missense mutation in two unrelated women (diagnosed >50 years old) (63). Therefore, while AIP mutations are rare, they may predispose to parathyroid carcinoma.

The role of AIP in the development of pituitary tumors

Initial investigations into defining AIP as a tumor suppressor in the pituitary gland focused on cell proliferation and GH secretion in AIP knockout, knockdown, and expression of mutant AIP variants in different cell types including the GH3 pituitary tumor cell line, 293 cells, and human fibroblasts (7). Expression of WT AIP reduced cell proliferation whereas AIP-deficient GH3 cells exhibited increased cell proliferation and AIP mutants were unable to decrease cell proliferation (76, 77, 78). AIP KO GH3 xenografted BALB/c nude mice had tumors that were four times larger than control cells with more GH in secretory vesicles and increased cell proliferation as measured by Ki67 (77). The mice with AIP KO GH3 xenografts also weighed more and were larger (in length and width) 8 weeks after inoculation and had higher GH and IGF-1 levels (77). AIP can be found in association with secretory vesicles in somatotroph (GH-secreting) and lactotroph (PRL-secreting) cells (15). Consistently, AIP-deficient GH3 cells had a 7.3-fold increase in GH synthesis and 1.3-fold increase in PRL synthesis (77, 78). This increase in hormone secretion may be mediated by a “leaky” ryanodine receptor which has been shown to cause excessive Ca2+ release from the ER in C. elegans with non-functional AIP variants (79).

AIP knockdown and AIP variants were also associated with a more invasive phenotype (78). AIP-deficient GH3 cells exhibited epithelial-to-mesenchymal-transition (EMT)-like changes with elongated, spindle-shape mesenchymal morphology, increased flexibility and elevated release of chemotactic factors (80). AIP-mutation positive pituitary tumors were associated with an altered tumor microenvironment including increased CD86+ macrophage and FOXP3+ Tregs infiltration, and upregulation of tumor-derived cytokine CCL5 (also known as RANTES). These AIP-mutation positive tumors had a gene signature indicative of increased EMT, with downregulation of CDH1 (E-cadherin), absent membranous CTNNB1 (B-cadherin), increased expression of ZEB1 (Zinc-finger E-box binding homeobox 1), and decreased expression of ESPR1 (epithelial splicing regulatory protein 1), PERP (TP53 apoptosis effector), and EPCAM (epithelial cell adhesion molecule). Furthermore, pituitary-specific AIP KO mice had a greater disruption of the reticulin network and increased F4/80+ infiltrating macrophages in the pituitary gland of 15-month-old mice (80). Together, these findings highlight the disruption of the tumor microenvironment in AIP-mutant-positive tumors and suggest that CCL5 and its receptor CCR5 could serve as potential therapeutic targets.

Another AIP variant, a T171I missense mutation, was found in three patients with pituitary adenoma and was associated with decreased expression of Sstr2 (somatostatin receptor 2), which is needed for responsiveness to somatostatin analogs (78). The AIP variant was also associated with decreased expression of the tumor suppressor gene Zac1. In contrast, there was increased phosphorylation of Stat3 and IL-6 expression, a well-characterized oncogenic signaling axis (78).

AIP mutations are generally loss-of-function and have been linked to diminished or impaired protein interactions since about 75% of known mutations are clustered in the C-terminus of AIP, a region essential for most of the AIP protein-protein interactions (13, 45, 81). Indeed, several AIP binding partners, including PPARα and NME1 (a tumor suppressor that negatively regulates cell migration, motility, and proliferation and has a negative correlation with pituitary tumor extension into the cavernous sinus) have been associated with pituitary tumorigenesis (82, 83, 84). However, it was determined that there was no correlation between PPARα and AIP in pituitary tumors (83). Furthermore, the effect of AIP knockdown on GH3 secretion in the presence of AhR ligands was inconclusive (85, 86). The functional effects of the AIP-NME1 interaction remain unknown (84). More work is needed to understand how AIP mutations impact its interactions with other proteins and the effects of those interactions on pituitary tumorigenesis.

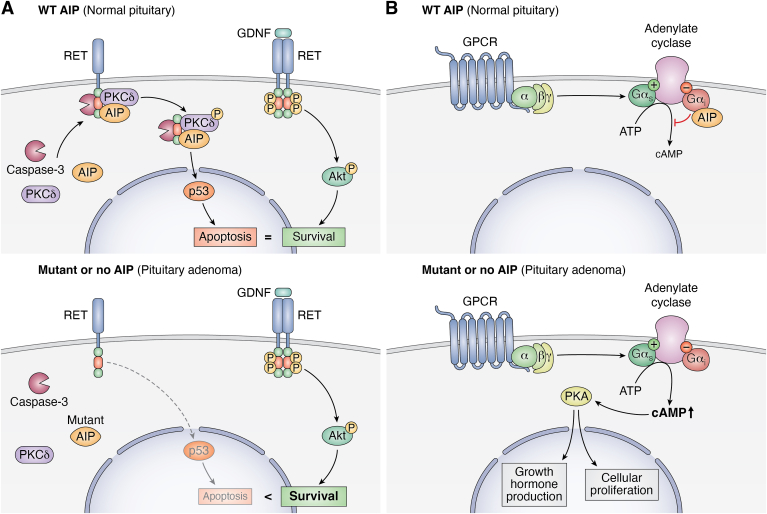

In the RET/caspase-3/PKCδ pathway, RET is cleaved and intracellular RET forms a complex with caspase-3 and PKCδ (87). PKCδ is then phosphorylated and cleaved by caspase-3, leading to the phosphorylation of JNK and CREB, which upregulate PIT1, ARF, and p53 to promote apoptosis. AIP stabilizes the RET-caspase 3-PKCδ complex in PIT1-expressing cells (somatotrophs and lactotrophs) promoting the apoptotic PIT1-CDK2N1-ARF-p53 signaling pathway (20, 34), thereby balancing the pro-survival GNDF-mediated activation of RET and the AKT pathway (Fig. 4A, top). In the absence of AIP or in the presence of AIP pathogenic mutants, the RET/caspase-3/PKCδ complex is disrupted, which leads to increased proliferation of somatotrophs (34) (Fig. 4A, bottom). However, six common AIP mutants found in patients with pituitary adenoma were still able to interact with RET (33).

Figure 4.

Tumor suppressor function of AIP in somatotrophs.A, AIP regulates RET signaling to promote apoptosis. GDNF (glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor) binding to the RET receptor promotes cell survival through AKT signaling. In wild-type AIP somatotrophs (top), AKT cell survival signaling is balanced by the pro-apoptotic RET/caspase-3/PKCδ pathway. In this pathway, AIP promotes the shuttling of caspase-3 and PKCδ to the intracellular (IC) portion of the RET receptor. Caspase-3 cleaves the IC portion of RET and PKCδ which activates the pro-apoptotic p53 pathway. However, in somatotrophs expressing loss of function AIP or no AIP (bottom), the RET/caspase-3/PKCδ pathway is downregulated and the pro-survival GDNF-mediated RET/AKT pathway predominates over the pro-apoptotic RET/caspase-3/PKCδ pathway thus predisposing to pituitary adenoma formation. B, AIP regulates cAMP signaling through its interaction with the inhibitory Gαi subunit (top). When AIP is mutated or deleted, cAMP signaling is dysregulated. The increased cAMP promotes PKA-mediated GH production and cellular proliferation.

Since neuroendocrine tumors often have dysregulated cAMP signaling (68, 88), AIP regulation of cAMP via its interactions with PDEs and G-proteins has been the subject of several studies. AIP has been shown to reduce cAMP levels and activity, which was impaired by AIP R304X expression (77, 78, 88). In addition, overexpression of AIP caused a reduction in GH secretion, while AIP knockdown or AIP R304X expression increased GH secretion (88). Furthermore, microarray analysis revealed that Aip−/− MEFs have impaired cAMP signaling (68). Knockout or knockdown of AIP resulted in the accumulation of cAMP, and this was due to defective Gαi2 signaling and subsequent downregulation of pERK1/2 and p-CREB (68). Several N-terminal AIP mutants were shown to have disrupted Gαi-2 and Gαi-3 protein function, subsequently leading to increased cAMP and GH levels, as well as increased cell proliferation (68) (Fig. 4B). AIP also interacts with PKA regulatory and catalytic subunits to diminish PKA activity (36). Finally, various AIP mutants were shown to lose the interaction with phosphodiesterase-4A5 (PDE4A5) (76), although it is unclear if this is related to its tumor suppressor functions.

In addition to AIP mutants, downregulated expression of AIP could also promote the development of pituitary adenomas. Known regulators of AIP expression include general transcription factor IIb (GTF2B) and microRNAs (89, 90, 91, 92). There was a positive correlation between GTF2B and AIP mRNA expression, with high-grade GH-secreting pituitary adenomas having both lower GTF2B and AIP expression (89). Two micro-RNAs, miR-107 and miR-34a, have been associated with cancers and decreased AIP expression. While miR-107 binds to the 3′UTR of AIP and downregulates AIP expression, no correlation was observed between AIP levels and miR-107 expression in pituitary adenomas (90). High expression of another microRNA, miR-34a, was also associated with more invasive pituitary adenomas and was shown to decrease AIP expression through regulation of the 3′UTR of AIP (91). More work is needed to understand how AIP expression is normally regulated and how its expression could be impacted during pituitary tumor development.

AIP in non-endocrine tumors

Elevated AIP expression has been associated with a worse prognosis of several carcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract, including cholangiocarcinoma, pancreatic carcinoma, gastric carcinoma, and colorectal cancer (17, 18, 20). While these studies mainly found a correlation between AIP expression and carcinogenesis, rather than AIP activity, they nevertheless suggest that AIP may act as an oncogene in the gastrointestinal tract.

AIP expression was examined in pancreatic tumors from 204 patients (17). While cytoplasmic AIP expression was associated with a worse prognosis, 9.8% of samples with nuclear AIP staining were associated with a better prognosis (17). However, it remains unclear why nuclear AIP would improve the prognosis of pancreatic cancer patients.

Another study examined AIP expression in 147 cases of gastric cancer, and 36.6% of the tumors had high AIP expression (18). AIP staining was cytoplasmic in most of the tumors. Interestingly, high AIP expression was significantly and independently correlated with tumor progression and death, with high AIP expression associated with lower survival and higher progression rates. This suggests that AIP acts as an oncogene in gastric cancer, but again the mechanism is unknown (18).

Examination of the Cancer Genome Atlas database found that high AIP expression was associated with decreased survival and increased risk of relapse in colorectal cancer. Furthermore, functional studies revealed that AIP overexpression in colon epithelial cells increased cell migration and EMT transition, and inoculation of these cells in a mouse model of metastatic colon cancer led to liver metastasis and decreased survival (20).

AIP overexpression was noted in several highly metastatic colon cancer cell lines (KM12SM, SW620, Lim1213) compared to poorly metastatic cell lines (16). There was also a significant association between high AIP expression and lower survival in a public cohort of 508 colorectal cancer patients. When poorly metastatic colorectal cancer cells were stably transfected with AIP, there was increased activation of SRC, JNK, and AKT kinases and characteristics of the more metastatic, invasive colorectal cancer cell line, KM12SM, including increased migration, EMT, adhesion, and invasion (16). Proteomic analysis in the study further revealed that AIP upregulated the expression of the cell adhesion protein cadherin-17 (CDH17), which may promote liver adhesion and homing of colorectal cancer cells expressing AIP. Inoculation of AIP overexpressing KM12 cells into the spleen of nude mice yielded larger and highly proliferative tumors with increased liver metastasis, resulting in decreased survival (16).

In addition to these GI cancers, high AIP expression is also associated with DLBCL as revealed by the cBioPortal database for Cancer Genomics, histological examination of primary DLBCL compared to healthy controls, and in various DLBCL cell lines (19). As mentioned earlier, AIP involvement in DLBCL may be through its positive regulation of the transcription factor BCL6.

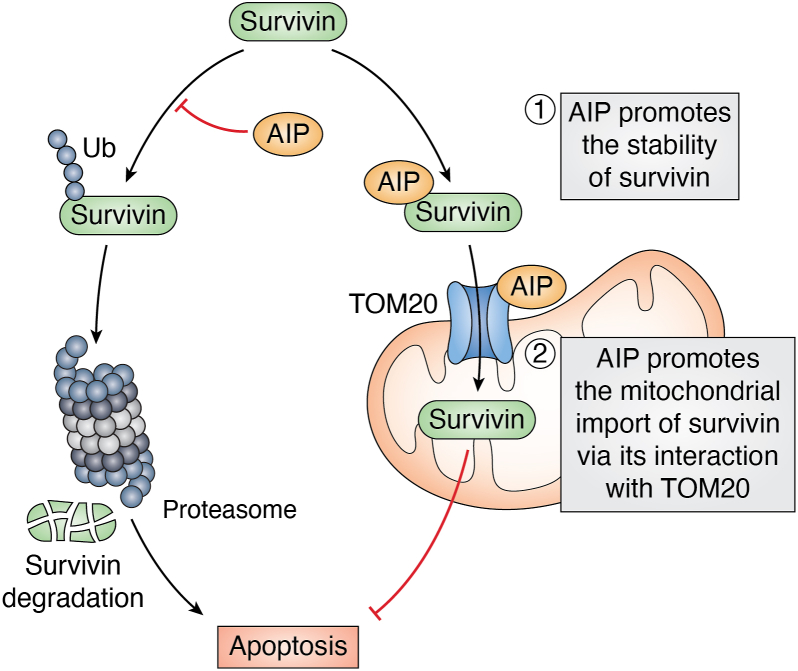

Although the mechanisms of AIP oncogenic functions are not well known and could vary depending on the specific tumor, AIP has been shown to interact with and regulate potential oncogenes. As discussed earlier, a proteomics screen identified AIP as an interacting protein of survivin, a member of the anti-apoptotic IAP family (38). AIP binds to and stabilizes survivin and therefore knockdown of AIP destabilizes survivin and enhances cell death (38). AIP is therefore likely a chaperone protein important to stabilize survivin. Furthermore, through its interaction with the mitochondrial protein, TOM20, AIP promotes the mitochondrial import of survivin to promote cell survival (39) (Fig. 5). AIP regulation of survivin is a salient example of a potential oncogenic mechanism but additional studies are needed to further understand how AIP can promote tumorigenesis.

Figure 5.

AIP promotes survivin stability and its mitochondrial import via TOM20. AIP functions as a chaperone to enhance the stability of the anti-apoptotic protein survivin. AIP also interacts with the mitochondrial import receptor TOM20 to facilitate the shuttling of survivin to the mitochondria, where it is imported and exerts its anti-apoptotic functions.

Closing remarks

AIP has been widely studied both as a co-chaperone molecule for AhR and as a tumor suppressor in the pituitary gland. However, AIP interacts with many other proteins and exerts a variety of effects on most of its client proteins that can be cell- and species-specific. Further investigations into known AIP-binding proteins and the discovery of novel interacting partners will undoubtedly unveil new functions and physiological roles of AIP, particularly in the immune system.

AIP suppresses the innate immune response by inhibiting IRF7 but enhances T-cell activation through the CBM complex and NF-κB activation. AIP likely has other functions in the immune system that are unexplored, but the generation of AIP conditional knockout mice in different immune cell types could shed light on its novel functions in the immune system. The tissue-specific roles of AIP are further highlighted in its disparate roles as a tumor suppressor in the pituitary gland and an oncogene in the context of DLBCL, colorectal, gastric, and pancreatic cancers (17, 18, 19, 20). AIP tumor suppressor function is likely mediated by its regulation of RET and/or Gαi signaling in somatotrophs, such that loss of function mutations in AIP lead to increased hormone secretion and cell proliferation (33, 34, 35, 36, 37). However, how AIP exerts oncogenic activity remains an open question, although the survivin-AIP interaction could potentially explain its oncogenic functions in certain cancers. Regardless, additional studies are needed for a more refined understanding of how AIP can promote oncogenesis in a tissue-specific manner.

The immune regulatory functions of AIP could potentially contribute to its described roles in cancer. Pituitary-specific deletion of AIP in mice led to increased infiltration of tumors with macrophages and FOXP3+Tregs, consistent with AIP-mutation-positive tumors in humans versus sporadic pituitary tumors (80). Increased tumor-associated macrophages were associated with an EMT-like phenotype, caused by macrophage-derived soluble factors (80). Therefore, AIP likely plays an important role in regulating the tumor microenvironment and restricting the recruitment of immunosuppressive tumor-associated macrophages and Tregs. Similar to AIP, IRF7 has been shown to play complex roles in the tumor microenvironment and can exert oncogenic or tumor suppressor activity, depending on the type of cancer (93). It will be of interest to examine IRF7 expression and activation as well as type I IFN expression in the tumor microenvironment of pituitary tumors as well as cancers associated with elevated AIP expression. AIP overexpression in tumors could potentially suppress the innate immune response and type I IFN in the tumor microenvironment which may contribute to the development and/or metastasis of certain cancers. Future studies should investigate how tumor-intrinsic AIP versus immune-cell AIP expression impacts the tumor microenvironment and tumor progression.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

S. A. K. writing–original draft; S. A. K., J. T., and E. W. H. writing–review and editing; E. W. H. funding acquisition.

Funding and additional information

The publication of this study was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases: NIH R21 AI153731. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Reviewed by members of the JBC Editorial Board. Edited by Alex Toker

References

- 1.Meyer B.K., Perdew G.H. Characterization of the AhR-hsp90-XAP2 core complex and the role of the immunophilin-related protein XAP2 in AhR stabilization. Biochemistry. 1999;38:8907–8917. doi: 10.1021/bi982223w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alqudah A., AbuDalo R., Qnais E., Wedyan M., Oqal M., McClements L. The emerging importance of immunophilins in fibrosis development. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2023;478:1281–1291. doi: 10.1007/s11010-022-04591-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma Q., Whitlock J.P., Jr. A novel cytoplasmic protein that interacts with the Ah receptor, contains tetratricopeptide repeat motifs, and augments the transcriptional response to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:8878–8884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyer B.K., Pray-Grant M.G., Vanden Heuvel J.P., Perdew G.H. Hepatitis B virus X-associated protein 2 is a subunit of the unliganded aryl hydrocarbon receptor core complex and exhibits transcriptional enhancer activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:978–988. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lees M.J., Peet D.J., Whitelaw M.L. Defining the role for XAP2 in stabilization of the dioxin receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:35878–35888. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302430200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carver L.A., LaPres J.J., Jain S., Dunham E.E., Bradfield C.A. Characterization of the Ah receptor-associated protein, ARA9. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:33580–33587. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rowlands J.C., Urban J.D., Wikoff D.S., Budinsky R.A. An evaluation of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the human aryl hydrocarbon receptor-interacting protein (AIP) gene. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2011;26:431–439. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.dmpk-11-sc-013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Petrulis J.R., Perdew G.H. The role of chaperone proteins in the aryl hydrocarbon receptor core complex. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2002;141:25–40. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(02)00064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gruszczyk J., Grandvuillemin L., Lai-Kee-Him J., Paloni M., Savva C.G., Germain P., et al. Cryo-EM structure of the agonist-bound Hsp90-XAP2-AHR cytosolic complex. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:7010. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-34773-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Linnert M., Lin Y.J., Manns A., Haupt K., Paschke A.K., Fischer G., et al. The FKBP-type domain of the human aryl hydrocarbon receptor-interacting protein reveals an unusual Hsp90 interaction. Biochemistry. 2013;52:2097–2107. doi: 10.1021/bi301649m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bell D.R., Poland A. Binding of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) to AhR-interacting protein. The role of hsp90. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:36407–36414. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004236200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laenger A., Lang-Rollin I., Kozany C., Zschocke J., Zimmermann N., Ruegg J., et al. XAP2 inhibits glucocorticoid receptor activity in mammalian cells. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:1493–1498. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trivellin G., Korbonits M. AIP and its interacting partners. J. Endocrinol. 2011;210:137–155. doi: 10.1530/JOE-11-0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuzhandaivelu N., Cong Y.S., Inouye C., Yang W.M., Seto E. XAP2, a novel hepatitis B virus X-associated protein that inhibits X transactivation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4741–4750. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.23.4741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lecoq A.L., Zizzari P., Hage M., Decourtye L., Adam C., Viengchareun S., et al. Mild pituitary phenotype in 3- and 12-month-old Aip-deficient male mice. J. Endocrinol. 2016;231:59–69. doi: 10.1530/JOE-16-0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Solis-Fernandez G., Montero-Calle A., Sanchez-Martinez M., Pelaez-Garcia A., Fernandez-Acenero M.J., Pallares P., et al. Aryl-hydrocarbon receptor-interacting protein regulates tumorigenic and metastatic properties of colorectal cancer cells driving liver metastasis. Br. J. Cancer. 2022;126:1604–1615. doi: 10.1038/s41416-022-01762-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fernandez-Acenero M.J., Barderas R., Pelaez Garcia A., Martinez-Useros J., Diez-Valladares L., Perez A., et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor interacting protein (AIP) significantly influences prognosis of pancreatic carcinoma. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 2021;53 doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2021.151742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diaz Del Arco C., Estrada Munoz L., Barderas Manchado R., Pelaez Garcia A., Ortega Medina L., Molina Roldan E., et al. Prognostic role of aryl hydrocarbon receptor interacting protein (AIP) immunohistochemical expression in patients with resected gastric carcinomas. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2020;26:2641–2650. doi: 10.1007/s12253-020-00863-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun D., Stopka-Farooqui U., Barry S., Aksoy E., Parsonage G., Vossenkamper A., et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor interacting protein maintains germinal center B cells through suppression of BCL6 degradation. Cell Rep. 2019;27:1461–1471.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haworth O., Korbonits M. AIP: a double agent? The tissue-specific role of AIP as a tumour suppressor or as an oncogene. Br. J. Cancer. 2022;127:1175–1176. doi: 10.1038/s41416-022-01964-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meyer B.K., Petrulis J.R., Perdew G.H. Aryl hydrocarbon (Ah) receptor levels are selectively modulated by hsp90-associated immunophilin homolog XAP2. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2000;5:243–254. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2000)005<0243:aharla>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kazlauskas A., Poellinger L., Pongratz I. Two distinct regions of the immunophilin-like protein XAP2 regulate dioxin receptor function and interaction with hsp90. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:11795–11801. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200053200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kazlauskas A., Poellinger L., Pongratz I. The immunophilin-like protein XAP2 regulates ubiquitination and subcellular localization of the dioxin receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:41317–41324. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007765200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petrulis J.R., Hord N.G., Perdew G.H. Subcellular localization of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor is modulated by the immunophilin homolog hepatitis B virus X-associated protein 2. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:37448–37453. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006873200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pollenz R.S., Wilson S.E., Dougherty E.J. Role of endogenous XAP2 protein on the localization and nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of the endogenous mouse Ahb-1 receptor in the presence and absence of ligand. Mol. Pharmacol. 2006;70:1369–1379. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.027672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.LaPres J.J., Glover E., Dunham E.E., Bunger M.K., Bradfield C.A. ARA9 modifies agonist signaling through an increase in cytosolic aryl hydrocarbon receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:6153–6159. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.9.6153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hollingshead B.D., Petrulis J.R., Perdew G.H. The aryl hydrocarbon (Ah) receptor transcriptional regulator hepatitis B virus X-associated protein 2 antagonizes p23 binding to Ah receptor-Hsp90 complexes and is dispensable for receptor function. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:45652–45661. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407840200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pollenz R.S., Dougherty E.J. Redefining the role of the endogenous XAP2 and C-terminal hsp70-interacting protein on the endogenous Ah receptors expressed in mouse and rat cell lines. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:33346–33356. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506619200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramadoss P., Petrulis J.R., Hollingshead B.D., Kusnadi A., Perdew G.H. Divergent roles of hepatitis B virus X-associated protein 2 (XAP2) in human versus mouse Ah receptor complexes. Biochemistry. 2004;43:700–709. doi: 10.1021/bi035827v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schulke J.P., Wochnik G.M., Lang-Rollin I., Gassen N.C., Knapp R.T., Berning B., et al. Differential impact of tetratricopeptide repeat proteins on the steroid hormone receptors. PLoS One. 2010;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cai W., Kramarova T.V., Berg P., Korbonits M., Pongratz I. The immunophilin-like protein XAP2 is a negative regulator of estrogen signaling through interaction with estrogen receptor alpha. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Froidevaux M.S., Berg P., Seugnet I., Decherf S., Becker N., Sachs L.M., et al. The co-chaperone XAP2 is required for activation of hypothalamic thyrotropin-releasing hormone transcription in vivo. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:1035–1039. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vargiolu M., Fusco D., Kurelac I., Dirnberger D., Baumeister R., Morra I., et al. The tyrosine kinase receptor RET interacts in vivo with aryl hydrocarbon receptor-interacting protein to alter survivin availability. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009;94:2571–2578. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garcia-Rendueles A.R., Chenlo M., Oroz-Gonjar F., Solomou A., Mistry A., Barry S., et al. RET signalling provides tumorigenic mechanism and tissue specificity for AIP-related somatotrophinomas. Oncogene. 2021;40:6354–6368. doi: 10.1038/s41388-021-02009-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Oliveira S.K., Hoffmeister M., Gambaryan S., Muller-Esterl W., Guimaraes J.A., Smolenski A.P. Phosphodiesterase 2A forms a complex with the co-chaperone XAP2 and regulates nuclear translocation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:13656–13663. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610942200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schernthaner-Reiter M.H., Trivellin G., Stratakis C.A. Interaction of AIP with protein kinase A (cAMP-dependent protein kinase) Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018;27:2604–2613. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddy166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakata A., Urano D., Fujii-Kuriyama Y., Mizuno N., Tago K., Itoh H. G-protein signalling negatively regulates the stability of aryl hydrocarbon receptor. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:622–628. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kang B.H., Altieri D.C. Regulation of survivin stability by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor-interacting protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:24721–24727. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603175200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kang B.H., Xia F., Pop R., Dohi T., Socolovsky M., Altieri D.C. Developmental control of apoptosis by the immunophilin aryl hydrocarbon receptor-interacting protein (AIP) involves mitochondrial import of the survivin protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:16758–16767. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.210120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao Y., Meng X.M., Wei Y.J., Zhao X.W., Liu D.Q., Cao H.Q., et al. Cloning and characterization of a novel cardiac-specific kinase that interacts specifically with cardiac troponin I. J. Mol. Med. (Berl.) 2003;81:297–304. doi: 10.1007/s00109-003-0427-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin B.C., Sullivan R., Lee Y., Moran S., Glover E., Bradfield C.A. Deletion of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor-associated protein 9 leads to cardiac malformation and embryonic lethality. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:35924–35932. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705471200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin B.C., Nguyen L.P., Walisser J.A., Bradfield C.A. A hypomorphic allele of aryl hydrocarbon receptor-associated protein-9 produces a phenocopy of the AHR-null mouse. Mol. Pharmacol. 2008;74:1367–1371. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.047068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nukaya M., Lin B.C., Glover E., Moran S.M., Kennedy G.D., Bradfield C.A. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor-interacting protein (AIP) is required for dioxin-induced hepatotoxicity but not for the induction of the Cyp1a1 and Cyp1a2 genes. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:35599–35605. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.132043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Raitila A., Lehtonen H.J., Arola J., Heliovaara E., Ahlsten M., Georgitsi M., et al. Mice with inactivation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor-interacting protein (Aip) display complete penetrance of pituitary adenomas with aberrant ARNT expression. Am. J. Pathol. 2010;177:1969–1976. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gillam M.P., Ku C.R., Lee Y.J., Kim J., Kim S.H., Lee S.J., et al. Somatotroph-specific Aip-deficient mice display pretumorigenic alterations in cell-cycle signaling. J. Endocr. Soc. 2017;1:78–95. doi: 10.1210/js.2016-1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schernthaner-Reiter M.H., Trivellin G., Roetzer T., Hainfellner J.A., Starost M.F., Stratakis C.A. Prkar1a haploinsufficiency ameliorates the growth hormone excess phenotype in Aip-deficient mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2020;29:2951–2961. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddaa178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kew M.C. Hepatitis B virus x protein in the pathogenesis of hepatitis B virus-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011;26 Suppl 1:144–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Styles C.T., Paschos K., White R.E., Farrell P.J. The cooperative functions of the EBNA3 proteins are central to EBV persistence and latency. Pathogens. 2018;7:31. doi: 10.3390/pathogens7010031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kashuba E., Kashuba V., Pokrovskaja K., Klein G., Szekely L. Epstein-Barr virus encoded nuclear protein EBNA-3 binds XAP-2, a protein associated with Hepatitis B virus X antigen. Oncogene. 2000;19:1801–1806. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li S., Wang L., Berman M., Kong Y.Y., Dorf M.E. Mapping a dynamic innate immunity protein interaction network regulating type I interferon production. Immunity. 2011;35:426–440. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Honda K., Yanai H., Negishi H., Asagiri M., Sato M., Mizutani T., et al. IRF-7 is the master regulator of type-I interferon-dependent immune responses. Nature. 2005;434:772–777. doi: 10.1038/nature03464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou Q., Lavorgna A., Bowman M., Hiscott J., Harhaj E.W. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor interacting protein targets IRF7 to suppress antiviral signaling and the induction of type I interferon. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:14729–14739. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.633065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kazzaz S.A., Shaikh K.A., White J., Zhou Q., Powell W.H., Harhaj E.W. Phosphorylation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor interacting protein by TBK1 negatively regulates IRF7 and the type I interferon response. J. Biol. Chem. 2023;300 doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2023.105525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhao C., Zhao W. TANK-binding kinase 1 as a novel therapeutic target for viral diseases. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 2019;23:437–446. doi: 10.1080/14728222.2019.1601702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Matsumoto R., Wang D., Blonska M., Li H., Kobayashi M., Pappu B., et al. Phosphorylation of CARMA1 plays a critical role in T cell receptor-mediated NF-kappaB activation. Immunity. 2005;23:575–585. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blonska M., Lin X. NF-kappaB signaling pathways regulated by CARMA family of scaffold proteins. Cell Res. 2011;21:55–70. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schimmack G., Eitelhuber A.C., Vincendeau M., Demski K., Shinohara H., Kurosaki T., et al. AIP augments CARMA1-BCL10-MALT1 complex formation to facilitate NF-kappaB signaling upon T cell activation. Cell Commun. Signal. 2014;12:49. doi: 10.1186/s12964-014-0049-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Basso K., Dalla-Favera R. BCL6: master regulator of the germinal center reaction and key oncogene in B cell lymphomagenesis. Adv. Immunol. 2010;105:193–210. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(10)05007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Duan S., Cermak L., Pagan J.K., Rossi M., Martinengo C., di Celle P.F., et al. FBXO11 targets BCL6 for degradation and is inactivated in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. Nature. 2012;481:90–93. doi: 10.1038/nature10688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Georgitsi M., Raitila A., Karhu A., Tuppurainen K., Makinen M.J., Vierimaa O., et al. Molecular diagnosis of pituitary adenoma predisposition caused by aryl hydrocarbon receptor-interacting protein gene mutations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:4101–4105. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700004104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vroonen L., Beckers A., Camby S., Cuny T., Beckers P., Jaffrain-Rea M.L., et al. The clinical and therapeutic profiles of prolactinomas associated with germline pathogenic variants in the aryl hydrocarbon receptor interacting protein (AIP) gene. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2023;14 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1242588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tatsi C., Stratakis C.A. The genetics of pituitary adenomas. J. Clin. Med. 2019;9:30. doi: 10.3390/jcm9010030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pardi E., Marcocci C., Borsari S., Saponaro F., Torregrossa L., Tancredi M., et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor interacting protein (AIP) mutations occur rarely in sporadic parathyroid adenomas. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013;98:2800–2810. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-4029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Igreja S., Chahal H.S., King P., Bolger G.B., Srirangalingam U., Guasti L., et al. Characterization of aryl hydrocarbon receptor interacting protein (AIP) mutations familial isolated pituitary adenoma families. Hum. Mutat. 2010;31:950–960. doi: 10.1002/humu.21292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lloyd C., Grossman A. The AIP (aryl hydrocarbon receptor-interacting protein) gene and its relation to the pathogenesis of pituitary adenomas. Endocrine. 2014;46:387–396. doi: 10.1007/s12020-013-0125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Daly A.F., Tichomirowa M.A., Petrossians P., Heliovaara E., Jaffrain-Rea M.L., Barlier A., et al. Clinical characteristics and therapeutic responses in patients with germ-line AIP mutations and pituitary adenomas: an international collaborative study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010;95:E373–E383. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Daly A.F., Beckers A. Familial isolated pituitary adenomas (FIPA) and mutations in the aryl hydrocarbon receptor interacting protein (AIP) gene. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 2015;44:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tuominen I., Heliovaara E., Raitila A., Rautiainen M.R., Mehine M., Katainen R., et al. AIP inactivation leads to pituitary tumorigenesis through defective Galphai-cAMP signaling. Oncogene. 2015;34:1174–1184. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Occhi G., Jaffrain-Rea M.L., Trivellin G., Albiger N., Ceccato F., De Menis E., et al. The R304X mutation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor interacting protein gene in familial isolated pituitary adenomas: mutational hot-spot or founder effect? J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2010;33:800–805. doi: 10.1007/BF03350345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Beckers A., Aaltonen L.A., Daly A.F., Karhu A. Familial isolated pituitary adenomas (FIPA) and the pituitary adenoma predisposition due to mutations in the aryl hydrocarbon receptor interacting protein (AIP) gene. Endocr. Rev. 2013;34:239–277. doi: 10.1210/er.2012-1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hernandez-Ramirez L.C., Martucci F., Morgan R.M., Trivellin G., Tilley D., Ramos-Guajardo N., et al. Rapid proteasomal degradation of mutant proteins is the primary mechanism leading to tumorigenesis in patients with missense AIP mutations. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016;101:3144–3154. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jaffrain-Rea M.L., Angelini M., Gargano D., Tichomirowa M.A., Daly A.F., Vanbellinghen J.F., et al. Expression of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) and AHR-interacting protein in pituitary adenomas: pathological and clinical implications. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 2009;16:1029–1043. doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kasuki Jomori de Pinho L., Vieira Neto L., Armondi Wildemberg L.E., Gasparetto E.L., Marcondes J., de Almeida Nunes B., et al. Low aryl hydrocarbon receptor-interacting protein expression is a better marker of invasiveness in somatotropinomas than Ki-67 and p53. Neuroendocrinology. 2011;94:39–48. doi: 10.1159/000322787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Igreja S., Chahal H.S., Akker S.A., Gueorguiev M., Popovic V., Damjanovic S., et al. Assessment of p27 (cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B) and aryl hydrocarbon receptor-interacting protein (AIP) genes in multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN1) syndrome patients without any detectable MEN1 gene mutations. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf.) 2009;70:259–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Raitila A., Georgitsi M., Bonora E., Vargiolu M., Tuppurainen K., Makinen M.J., et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor interacting protein mutations seem not to associate with familial non-medullary thyroid cancer. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2009;32:426–429. doi: 10.1007/BF03346480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Leontiou C.A., Gueorguiev M., van der Spuy J., Quinton R., Lolli F., Hassan S., et al. The role of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor-interacting protein gene in familial and sporadic pituitary adenomas. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008;93:2390–2401. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fukuda T., Tanaka T., Hamaguchi Y., Kawanami T., Nomiyama T., Yanase T. Augmented growth hormone secretion and Stat3 phosphorylation in an aryl hydrocarbon receptor interacting protein (AIP)-disrupted somatotroph cell line. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cai F., Hong Y., Xu J., Wu Q., Reis C., Yan W., et al. A novel mutation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor interacting protein gene associated with familial isolated pituitary adenoma mediates tumor invasion and growth hormone hypersecretion. World Neurosurg. 2019;123:e45–e59. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chen B., Liu P., Hujber E.J., Li Y., Jorgensen E.M., Wang Z.W. AIP limits neurotransmitter release by inhibiting calcium bursts from the ryanodine receptor. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1380. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01704-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Barry S., Carlsen E., Marques P., Stiles C.E., Gadaleta E., Berney D.M., et al. Tumor microenvironment defines the invasive phenotype of AIP-mutation-positive pituitary tumors. Oncogene. 2019;38:5381–5395. doi: 10.1038/s41388-019-0779-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Morgan R.M., Hernandez-Ramirez L.C., Trivellin G., Zhou L., Roe S.M., Korbonits M., et al. Structure of the TPR domain of AIP: lack of client protein interaction with the C-terminal alpha-7 helix of the TPR domain of AIP is sufficient for pituitary adenoma predisposition. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Peculis R., Niedra H., Rovite V. Large scale molecular studies of pituitary neuroendocrine tumors: novel markers, mechanisms and translational perspectives. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13:1395. doi: 10.3390/cancers13061395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rotondi S., Modarelli A., Oliva M.A., Rostomyan L., Sanita P., Ventura L., et al. Expression of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor alpha (PPARalpha) in somatotropinomas: relationship with Aryl hydrocarbon receptor Interacting Protein (AIP) and in vitro effects of fenofibrate in GH3 cells. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2016;426:61–72. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2016.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]