Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) arises via the progressive accumulation of dysregulation in key genes including oncogenes and tumor-suppressor genes. Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTGS2, also called COX2) acts as an oncogenic driver in CRC. Here, we explored the upstream transcription factors (TFs) responsible for elevating PTGS2 expression in CRC cells. The results showed that PTGS2 silencing repressed cell growth, migration and invasion in HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells. The two fragments (499–981 bp) and (1053–1434 bp) were confirmed as the core TF binding profiles of the PTGS2 promoter. PTGS2 expression positively correlated with RUNX1 level in colon adenocarcinoma (COAD) samples using the TCGA-COAD dataset. Furthermore, RUNX1 acted as a positive regulator of PTGS2 expression by promoting transcriptional activation of the PTGS2 promoter via the 1086–1096 bp binding motif. In conclusion, our study demonstrates that PTGS2 upregulation induced by the TF RUNX1 promotes CRC cell growth, migration and invasion, providing an increased rationale for the use of PTGS2 inhibitors in CRC prevention and treatment.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, PTGS2, Transcription factor (TF), RUNX1

Subject terms: Cancer, Cell biology, Molecular biology, Diseases, Gastroenterology, Oncology

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most prevalent malignancy and ranks second in terms of mortality around the world1. There are many risk factors for CRC, including hereditary factors, environmental factors and inflammatory stimuli2. This cancer is a heterogeneous disease that has close relevance to a number of somatic and genetic alterations3,4. Recent studies have focused on investigating the molecular products, such as proteins and RNAs, that drive colorectal tumorigenesis and CRC cell malignant phenotype3,5,6. These molecular researches would contribute to the development of personalized medicine in the future.

Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTGS2, also called COX2), a rate-limiting cyclooxygenase that can be induced by inflammatory stimuli, is crucial for the production of inflammatory prostaglandin and possesses essential activity from normal development to human disease7–9. As an example, Zhou et al. established the role of PTGS2 as the hub gene in promoting atherosclerosis progression10. Moreover, PTGS2 has been reported to strongly participate in inflammatory responses and thus contributes to liver fibrosis and chronic periodontitis11,12. Importantly, recent work has revealed the significant involvement of PTGS2 in cancer initiation, progression and metastasis13,14. Indeed, elevated PTGS2 has been implicated in enhanced angiogenesis, increased tumor invasion and reduced cell apoptosis, and inhibitors of PTGS2 have been proposed as promising therapeutic agents against cancer15. In CRC, PTGS2 expression is markedly promoted in tumor samples versus normal colorectal tissues and tightly associated with poorer CRC-specific survival16,17. Furthermore, PTGS2 has an established role in promoting colorectal tumorigenesis and CRC progression18–20. These studies suggest that inhibition of PTGS2 is a potential therapeutic approach in CRC; however, the upstream regulators of PTGS2 abnormal expression have not yet been explored.

Transcription factors (TFs) have the capacity of controlling the rate of gene transcription by binding to specific DNA sequences in the promoters and thus have been identified as vital regulators in cancer biology21,22. Runt-related TF 1 (RUNX1), a member of the core-binding factor family of TFs, is involved in the regulation of a series of cellular processes, including cell growth, differentiation, survival, and death23,24. There is ample evidence that RUNX1 functions as a potent driver in various human cancers23,25,26. Importantly, RUNX1 can promote CRC cell migration and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) through TGF-β and Wnt/β-catenin pathways27,28. RUNX1 contributes to CRC cell growth and chemoresistance development via the Hedgehog signaling pathway29. In addition, RUNX1-activated upregulation of long non-coding RNA RNCR3 drives CRC cell malignant behaviors30. Nonetheless, the molecular basis of the oncogenic effect of RUNX1 on CRC development is still not fully understood.

In the current study, our data support the oncogenic role of PTGS2 in CRC in vitro. Further, we focused on elucidating the TFs that regulate PTGS2 expression in CRC cells. We identify, for the first time, RUNX1 as a transcription activator of PTGS2 in CRC cells by binding to the PTGS2 promoter and promoting its transcriptional activation.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and transfection

HCT116 (Cat#CL-0096, isolated from rectum tissues of patients with CRC) and SW480 (Cat#CL-0223B, isolated from colon tissues of patients with colorectal adenocarcinoma) CRC cells (Procell, Wuhan, China) were used in this study. HCT116 and SW480 cells were maintained in DMEM (Cat#G4510-500ML, Servicebio, Wuhan, China) enriched with 1% antibiotics (Cat#C0222, penicillin/streptomycin, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Cat#G8001-100ML, Servicebio). We maintained the two cell lines at 37 °C in a cell culture incubator containing 5% CO2.

Short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) to human RUNX1 (RUNX1-shRNA1, RUNX1-shRNA2, RUNX1-shRNA3), PTGS2 (sh-PTGS2#1 and sh-PTGS2#2) and a scrambled control sh-NC were obtained from Tsingke Biotechnology (Beijing, China). Sequences of shRNAs are displayed in Table 1. Human RUNX1 expression plasmid pLV3-RUNX1 and PTGS2 expression plasmid LV-PTGS2 were procured from Miaolingbio (Wuhan, China), pLV3-NC was used as a control. For plasmid transfection, HCT116 and SW480 cells were plated in 6-well culture dishes until the cell confluence reached 80–90%. The mixture of 3 μg plasmids and 5 μL RFect Plasmid DNA Transfection Reagent (Cat#21015, Baidai, Changzhou, China) was prepared and added into each well for 12 h. Then cells were harvested for following cell functional assays.

Table 1.

Sequences for shRNAs.

| Name | Sequences of shRNA (5’-3’) |

|---|---|

| shPTGS2#1 | GATTGAAGATTATGTGCAA |

| shPTGS2#2 | GAAATGCAATTATGAGTTA |

| RUNX1-shRNA1 | CTACGATCAGTCCTACCAATA |

| RUNX1-shRNA2 | TCGCCCTGTTTGGCATCTAAT |

| RUNX1-shRNA3 | GAACCAGGTTGCAAGATTTAA |

Cell viability analysis

Transfected HCT116 and SW480 cells were seeded at 1 × 104 cells/well in 96-well cell culture dishes. After a 48-h culture, metabolically active cells were examined by adding 10 µL of Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, Cat#C0038) solution to each well, as per manufacturing protocol (Beyotime). The plates were analyzed in a microplate reader after 1 h incubation. Cell viability was assessed as fold change of control group.

Calcein/PI Cell Viability/Cytotoxicity Assay

Transfected HCT116 and SW480 cells were seeded at 2 × 104 cells/well in 96-well cell culture dishes. After a 48-h culture, metabolically active cells were examined byusing Calcein/PI Cell Viability/Cytotoxicity Assay Kit (Cat#C2015M), as per manufacturing protocols (Beyotime). The cells were observed under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), and images of three random fields per each sample were obtained. The number of stained cells was quantified by ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MA, USA) and cell viability was calculated by using the method: cell viability (%) = (number of Calcein AM+ cells)/(number of Calcein AM+ cells + number of PI+ cells) × 100.

Cell proliferation analysis

HCT116 and SW480 cells transfected as indicated were seeded in 96-well dishes at 1 × 104 cells/well and incubated in standard growth media for 48 h. Cell growth was evaluated by detecting proliferation with Click-iT EdU-555 or EdU-488 Cell Proliferation Kit (Cat#G1602 or Cat#G1601) as recommended by the manufacturer (Servicebio). Briefly, EdU solution was added into each well at a final concentration of 10 µM and incubation was allowed for 2–3 h. The cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with iF555 solution (for EdU incorporation) for 30 min at room temperature, followed by Hoechst 33,342 solution (for nucleus staining) for 5 min. Images of three random fields per each sample were captured in an Olympus fluorescence microscope, and the EdU positive cells were defined as a percentage of total nuclei.

Immunofluorescence

The effect of sh-PTGS2, RUNX1-shRNA3, or sh-NC control on CRC cells was evaluated by detecting matrix metallopeptidase 9 (MMP9) and PCNA expression with an immunocytochemical method. 24 hh post transfection, HCT116 and SW480 cells were fixed, permeabilized by incubation in 0.5% Triton X-100, and washed in 1 × phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Following blocking in 3% BSA (Cat#ST2249-5g, Beyotime) for 30 min, probing was carried out with primary antibody (Servicebio) against PCNA (Cat#GB11010, 1:500 dilution) or MMP9 (Cat#GB11132, 1:1000 dilution) as described31. The Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (Cat#GB25303, Servicebio) at 1:500 dilution in 1 × PBS was used as the secondary antibody. After nuclear staining with DAPI, the cells were visualized on the Olympus fluorescence microscope. Images of three random fields were obtained and the fluorescence intensity was quantified by ImageJ to get an average fluorescence intensity of PCNA or MMP9.

Transwell migration and invasion assays

After being re-suspended in the serum-free medium, transfected HCT116 and SW480 cells were seeded on 24-transwell inserts (8 µm pore size, Corning, Shanghai, China) with (for invasion analysis) or without (for migration analysis) growth factor reduced Corning® Matrigel as previously reported32. The inserts were placed in appropriate wells containing complete cell culture media and incubated for 48 h, followed by staining with crystal violet (0.1%, Cat#GC307002-25g, Servicebio). Migratory or invaded cells on the lower surface were visualized using bright-field microscopy (Olympus) at 100× magnification. Pictures of at least three random fields from three replicate wells were obtained and the number of the migratory and invaded cells was quantified by ImageJ.

JC-1 cell apoptosis assay

Apoptosis of transfected HCT116 and SW480 cells was evaluated by measuring cell mitochondrial membrane potential using JC-1 Assay Kit (Cat#C2006, Beyotime). Briefly, after being resuspended in DMEM growth medium, cells were incubated with JC-1 working solution for 20 min at 37 °C. The signals of red fluorescence (excitation/emission wavelengths: 525/590 nm) and green fluorescence (excitation/emission wavelengths: 490/530 nm) were observed under the Olympus fluorescence microscope. Images of three random fields were analyzed by ImageJ software, and the ratio of red fluorescence/green fluorescence was determined.

Bioinformatics

The sequence of the human PTGS2 promoter was retrieved from Ensemble database (http://uswest.ensembl.org/index.html). The data of all human TFs were downloaded from JASPAR database (https://jaspar.genereg.net/). The TF binding profiles of the PTGS2 promoter were predicted by JASPAR database. The known TFs in regulating PTGS2 expression were retrieved from KnockTF database (http://www.licpathway.net/KnockTF/). To predict the binding sites between RUNX1 and the PTGS2 promoter, we also utilized JASPAR database. To observe the expression correlation of PTGS2 and RUNX1 and the clinical significance of RUNX1 in CRC, we interrogated the TCGA-COAD dataset using the National Cancer Institute GDC Data Portal (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/).

DNA pull-down assay and qualitative proteome analysis

The full-length sequence of the human PTGS2 promoter was synthesized by Tsingke Biotechnology. The biotinylated promoter full-length sequence (P0: 0–2000 bp) and three promoter truncations labeled by biotin (P1: 0–981 bp, P2: 499–1434 bp and P3: 1052–2000 bp) were PCR-amplified using corresponding biotinylated primers (synthesized by Tsingke Biotechnology; shown in Table 2) with the synthetic PTGS2 promoter sequence as template. The PCR reaction system (50 µL) consisted of 5 µL template, 2 µL Primer F, 2 µL Primer R, 16 µL ddH2O, and 25 µL Phanta Flash Mix (2 × , Cat#P520-01, Vazyme Biotech, Nanjing, China). PCR amplification was performed with the following conditions: 98 °C for 2 min, followed by 35 cycles at 98 °C for 10 s, and 50 °C for 15 s and 72 °C for 15 s. PCR productions were validated by 1.5% agarose gel eletrophoresis. The biotin labeling effect was examined using a biotin labeling efficiency assay with an HRP-conjugated streptavidin (Cat#G3431, 1:3000, Servicebio) and ECL Kit (Cat#P0018S, Beyotime). Briefly, PCR production was adjusted to a concentration of 20 ng/µL and added on the nylon membranes (0.45 µm pore size, Beyotime). After ultraviolet crosslinking for 10 min and incubation with blocking solution (Beyotime) for 20 min, the membranes were probed with the HRP-conjugated streptavidin for 1 h at room temperature and visualized by the ECL Kit.

Table 2.

Sequences of primers used for PCR amplification.

| Name | Primers for PCR (5′–3′) | |

|---|---|---|

| P0 (1–2000 bp) | Forward | AGAAAGCTCTGGAAGATTTTTAAG |

| Reverse | GAAGTCACGTCGGGACAGAC | |

| P1 (1–981 bp) | Forward | AGAAAGCTCTGGAAGATTTTTAAG |

| Reverse | TCTGATTCTTCATGAGACACGG | |

| P2 (499–1434 bp) | Forward | GGGATAGATGGAGTTCAATTC |

| Reverse | TGACCATGGATCAAAGTACAAC | |

| P3 (1053–2000 bp) | Forward | ACTTCTACAAATTGAGGTACCTGG |

| Reverse | GAAGTCACGTCGGGACAGAC | |

| RUNX1 | Forward | CACTGTGATGGCTGGCAATG |

| Reverse | CCTCTTCCACTTCGACCGAC | |

| PTGS2 | Forward | GGAGGTCTTTGGTCTGGTGC |

| Reverse | ACAACTGCTCATCACCCCAT | |

| GAPDH | Forward | GACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC |

| Reverse | ACGCCTGCTTCACCACCTT |

For DNA pull-down assay, the nuclear protein of HCT116 CRC cells was extracted using Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Protein Extraction Kit (Cat#0027, Beyotime). Streptomycin beads were obtained from Beyotime and washed three times with 1 × TBST. A total of 10 µg each of the four biotin-labeled DNA sequences (P0, P1, P2 and P3) dissolved in binding&washing buffer was added separately into 35 µL streptomycin beads and incubation was performed for 30 min at room temperature in a vertical rotating mixer. After that, the nuclear protein extracts were incubated with the generated DNA-bead complex for 1 h at room temperature. Beads were washed three times with PBST, and bound proteins were eluted with the protein eluent, followed by boiling for 5 min in SDS loading buffer. The precipitated proteins in each group were subsequently processed for qualitative proteome analysis by Qinglianbio Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) with RIGOL L-3000 HPLC System (RIGOL, Beijing, China) and Proteome Discoverer2.4 software.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Transfected HCT116 cells were homogenized in RNAiso Plus (Cat#9109, TaKaRa, Dalian, China) after treatment of recombinant DNase I (Cat#2270A, TaKaRa). cDNA was randomly primed using PrimeScript™ RT Master Mix (Cat#RR036A, TaKaRa) from 2 µg of total RNA with random hexamers. Then, cDNA was diluted 15–20 fold and subjected to qRT-PCR using SYBR Premix ExTaq Kit (Cat#RR420A, TaKaRa) with primers specific for RUNX1 and PTGS2 (synthesized by Tsingke Biotechnology; shown in Table 2). Using GAPDH as a reference gene, we calculated mRNA expression with the 2-ΔΔCt method33.

Dual-luciferase reporter assay

The F4 fragment (1053–1434 bp) of the PTGS2 promoter and its three mutants in the individual binding site (site 1, 1062–1072 bp: AATTGAGGTAC; site 2, 1086–1096 bp: ATTTCAGGTTT; site 3, 1373–1383 bp: TATTGGGGCTA) were synthesized by Tsingke Biotechnology and cloned into the pGL3-basic vector (Promega, Southampton, UK), respectively. For luciferase reporter assay to measure the effect of RUNX1 on the transcription activity of the PTGS2 promoter, HCT116 cells (1 × 105 cells/well) were seeded in the wells of 6-well dishes one day before transfection with a mixture of 200 ng pGL3 luciferase constructs, 50 ng of pRL-TK Renilla internal control vector (Promega), and pLV3-RUNX1 or pLV3-NC. Cells were lysed 24 h later, and luciferase activity was assayed with the Dual-luciferase Reporter System (Cat#E1910, Promega). Firefly luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla activity and expressed as relative luciferase activity.

Statistical analysis

The results were representative of at least three separate experiments performed in triplicate. All error bars represent the SD of the mean. Differences were evaluated using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) by one-way or two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s or Sidak’s multivariate comparison (for three or more groups) or a unpaired Student’s t-test (two-tailed, for two groups) and considered significant when P < 0.05. Pictures were plotted by GraphPad Prism 8 and R-ggplot2 package. For survival analysis, the R-survival and R-survminer were used.

Results

Silencing of PTGS2 represses growth, migration and invasion of HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells

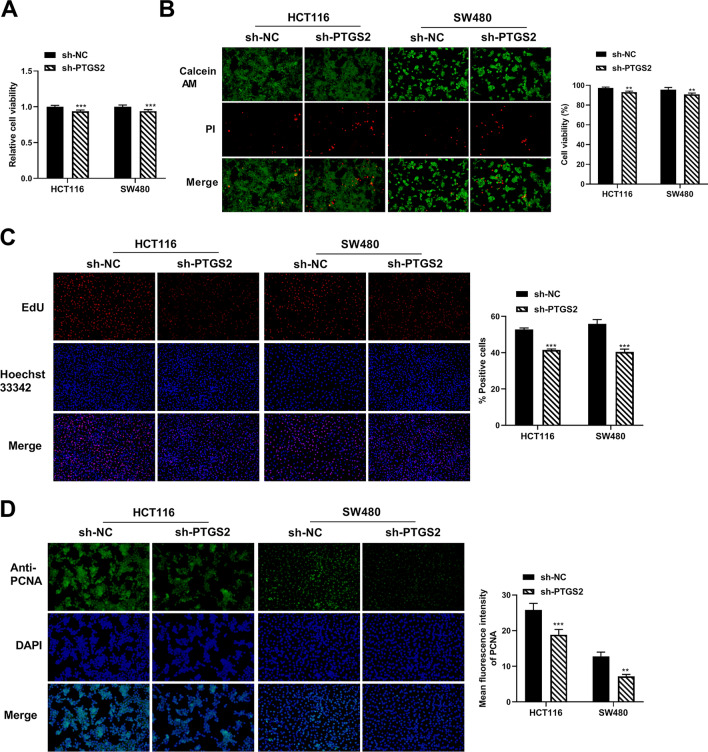

To test the effects of PTGS2 on cell growth, motility and invasion, we transfected HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells with two shRNAs specific for PTGS2 (sh-PTGS2#1 and sh-PTGS2#2) or a nontarget shRNA (sh-NC). The reduction efficacy of shRNAs in PTGS2 mRNA expression was validated by qRT-PCR (Supplementary Fig. 1A). Owing to the more significant inhibition of sh-PTGS2#2 on PTGS2 mRNA expression (Supplementary Fig. 1A), we used sh-PTGS2#2 (also named sh-PTGS2) for the subsequent silencing experiments. Silencing of PTGS2 by sh-PTGS2 significantly repressed CRC cell viability compared with the sh-NC control (Fig. 1A,B). EdU assays revealed that silencing of PTGS2 reduced the number of EdU positive cells in HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells after 48 h (Fig. 1C). Moreover, HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells transfected with sh-PTGS2 showed decreased expression of the proliferating marker PCNA compared with the control cells (Fig. 1D). Altogether, these data indicate that PTGS2 silencing represses CRC cell growth in vitro.

Figure 1.

PTGS2 silencing impedes the growth of HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells in vitro. (A, B) Cell viability assay was performed with HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells after transfection by sh-NC or sh-PTGS2#2 (also called sh-PTGS2) using CCK8 and Calcein/PI Cell Viability/Cytotoxicity Assay Kit. Images of three random fields per each sample were obtained. The number of stained cells was quantified by ImageJ and cell viability was calculated by using the method: cell viability (%) = (number of Calcein AM+ cells)/(number of Calcein AM+ cells + number of PI+ cells). (C) EdU assay for cell proliferation was performed with HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells transfected with sh-PTGS2 or sh-NC. Cells were incubated with EdU solution and stained with iF555 solution and Hoechst 33,342 solution. Images of three random fields per each sample were captured using a fluorescence microscope and the EdU positive cells (%positive cells) were defined as a percentage of total nuclei. Representative images per each group are shown. (D) Immunofluorescence assay showing PCNA fluorescence intensity in HCT116 and SW480 cell lines transfected as indicated. Cells were incubated with anti-PCNA antibody and secondary antibody. Cell nucleus was stained with DAPI. Images of three random fields were obtained and the fluorescence intensity was quantified by ImageJ to get an average fluorescence intensity of PCNA. Representative images per each sample are shown. n = three independent experiments performed in triplicate. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

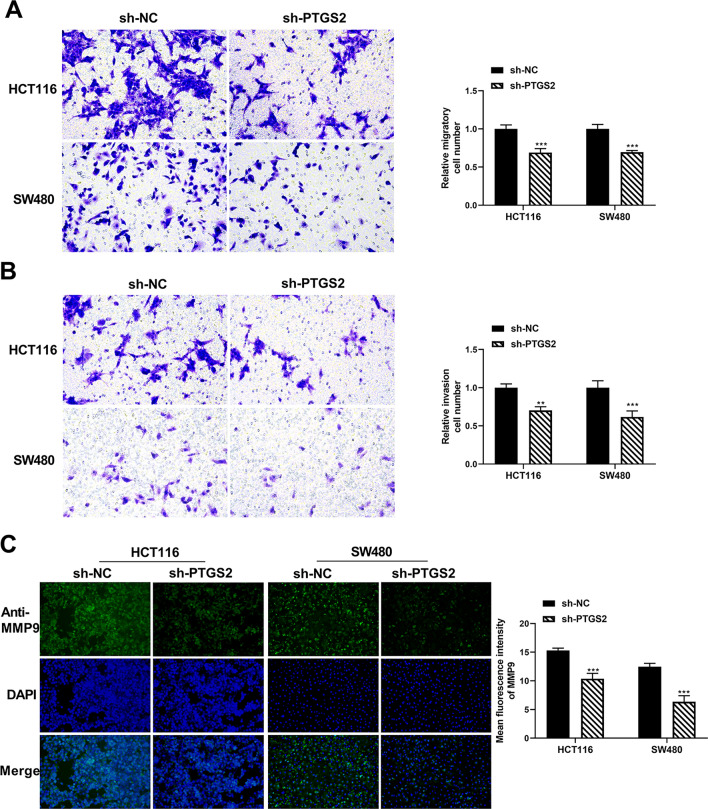

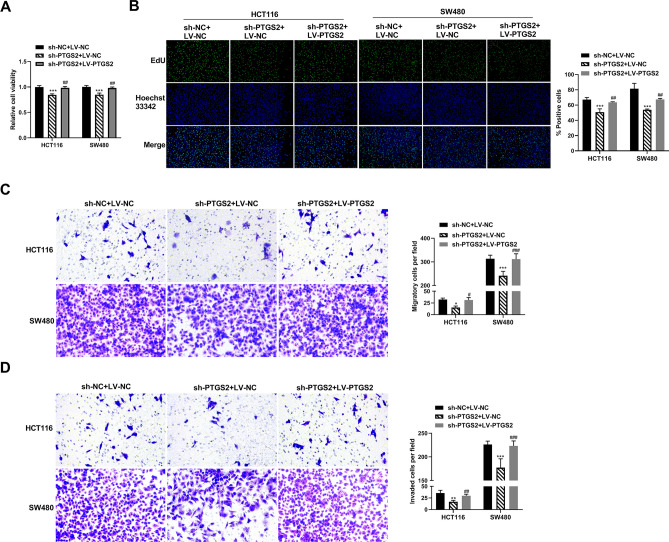

Using a transwell assay to study the effect on cell migration and invasion, we found that inhibition of PTGS2 by sh-PTGS2 introduction strongly impaired the migratory capacity of the two CRC cell lines (Fig. 2A). Moreover, silencing of PTGS2 impeded cell invasiveness compared with the sh-NC control (Fig. 2B). Through an immunofluorescence method, we found that PTGS2 inhibition led to a clear downregulation in the expression of the metastasis-related protein MMP9 in both HCT116 and SW480 CRC cell lines (Fig. 2C), supporting the notion that PTGS2 silencing impairs cell migration and invasion in vitro. Additionally, JC-1 fluorescence assays showed that CRC cells transfected with sh-PTGS2 had a lower ratio of red/green fluorescence signals than the controls (Supplementary Fig. 2), indicating that PTGS2 inhibition can promote CRC cell apoptosis in vitro. Lastly, to confirm that the observed phenotypes are indeed due to downregulation of PTGS2 and not to an off-target effect, we performed a rescue experiment by transfecting a PTGS2 expression plasmid into PTGS2-silenced HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells and found that the plasmid reversed sh-PTGS2-mediated inhibition of PTGS2 expression (Supplementary Fig. 1B). Furthermore, the PTGS2 expression plasmid reversed sh-PTGS2-mediated suppression of growth, migration and invasion of HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells (Fig. 3A–D).

Figure 2.

PTGS2 silencing represses the migration and invasion of HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells. (A, B) Transwell migration and invasion assays of HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells transfected with sh-PTGS2 or sh-NC. Transfected cells were seeded on 24-transwell inserts and translocated toward the complete growth medium. After 48 h of culture, pictures of at least three random fields from three replicate wells were obtained by a × 100 magnification microscope and the number of the migratory and invaded cells was quantified by ImageJ. (C) Immunofluorescence assay showing the fluorescence intensity of MMP9 in HCT116 and SW480 cells after transfection by sh-PTGS2 or sh-NC. Cells were incubated with anti-MMP9 antibody and secondary antibody. Cell nucleus was stained with DAPI. Images of three random fields were obtained and the fluorescence intensity was quantified by ImageJ to get an average fluorescence intensity of MMP9. Representative images per each sample are shown. n = three independent experiments performed in triplicate. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Figure 3.

The PTGS2 expression plasmid reverses PTGS2 silencing-mediated suppression of CRC cell growth, migration and invasion. (A) Cell viability assay was performed with HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells after transfection by sh-PTGS2 + LV-NC, sh-PTGS2 + LV-PTGS2 or sh-NC + LV-NC using CCK8 assay. (B) Cell proliferation was performed by EdU assay with HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells transfected with sh-PTGS2 + LV-NC, sh-PTGS2 + LV-PTGS2 or sh-NC + LV-NC. Cells were incubated with EdU solution and stained with iF488 solution and Hoechst 33,342 solution. Images of three random fields per each sample were captured using a fluorescence microscope and the EdU positive cells (%positive cells) were defined as a percentage of total nuclei. Representative images per each group are shown. (C, D) Transwell migration and invasion assays of HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells transfected with sh-PTGS2 + LV-NC, sh-PTGS2 + LV-PTGS2 or sh-NC + LV-NC. Transfected cells were seeded on 24-transwell inserts and translocated toward the complete growth medium. After 48 h of culture, pictures of at least three random fields from three replicate wells were obtained by a 100 × magnification microscope and the number of the migratory and invaded cells was quantified by ImageJ. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ##P < 0.01; ###P < 0.001.

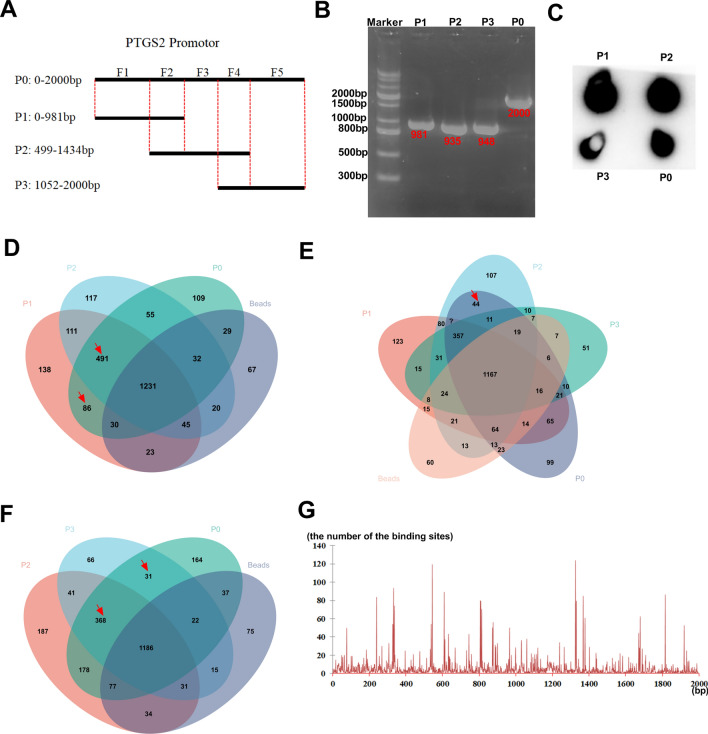

The two fragments (499-981 bp) and (1053-1434 bp) are the core TF binding profiles of the PTGS2 promoter

To elucidate the precise TF binding regions of the PTGS2 promoter, we firstly used PCR amplification with biotinylated primers to generate a biotinylated promoter full-length sequence (P0: 0–2000 bp) and three promoter truncations labeled by biotin (P1: 0–981 bp, P2: 499–1434 bp and P3: 1052–2000 bp) (Fig. 4A). The production of the four biotin-labeled sequences was validated by 1% agarose gel eletrophoresis (Fig. 4B) and a biotin labeling efficiency assay using an anti-biotin antibody conjugated by HRP (Fig. 4C). In the preliminary experiments, we found that HCT116 cells showed higher levels of PTGS2 mRNA than SW480 cells (data not shown), so HCT116 cells were selected for the subsequent mechanism assays. We then performed DNA pull-down assays: HCT116 CRC cells were lysed and incubated with each of the four biotin-labeled DNA sequences and streptomycin beads, followed by the collection of the precipitated proteins from the immunoprecipitates. Next, we analyzed the precipitated proteins using qualitative proteome profiling analysis by a HPLC–MS/MS method. Thousands of proteins were pulled down by each of the four biotin-labeled DNA sequences (P0, P1, P2 and P3) and beads (Supplementary Table 1). As illustrated in Fig. 4D, Venn diagram showed a total of 86 specific proteins pulled down by both P1 and P0 not P2 and beads (F1 fragment alone) and 491 specific proteins that overlapped among P1, P2 and P0 not beads (F2 fragment alone). Moreover, we found a total of 44 specific proteins pulled down by both P2 and P0 not P1, P3 and beads (F3 fragment alone), 368 proteins that overlapped among P2, P3 and P0 not beads (F4 fragment alone), and 31 proteins pulled down by both P3 and P0 not P2 and beads (F5 fragment alone) (Fig. 4E,F). These data indicated that the F1 fragment alone pulled down 86 specific proteins; the F2 fragment alone pulled down 491 specific proteins; the F3 fragment alone pulled down 44 specific proteins; the F4 fragment alone pulled down 368 specific proteins; and the F5 fragment alone pulled down 31 specific proteins. These proteins pulled down by each of the five fragments of the PTGS2 promoter were shown in Supplementary Table 2.

Figure 4.

The two fragments (499–981 bp) and (1053–1434 bp) are the core TF binding profiles of the PTGS2 promoter. (A) Schematic showing the four biotin-labeled sequences (P0, P1, P2 and P3) and the five fragments (F1, F2, F3, F4 and F5) of the PTGS2 promoter. The five fragments of the PTGS2 promoter (F1: 1–498 bp, F2: 499–981 bp, F3: 982–1052 bp, F4: 1053–1434 bp, and F5: 1435–2000 bp) were classified based on the four biotin-labeled sequences. (B) The biotin-labeled sequences (P0, P1, P2 and P3) were PCR-amplified using the PTGS2 promoter sequence as template. The production of the four biotin-labeled sequences was validated by 1% agarose gel eletrophoresis. (C) Biotin labeling efficiency assay using an anti-biotin antibody conjugated by HRP with ECL Kit. (D–F) Venn diagram showing the specific proteins pulled down by the four biotin-labeled DNA sequences (P0, P1, P2 and P3) and beads in HCT116 cells. (G) A distribution histogram showing the number of the binding sites in each base of the PTGS2 promoter predicted by JASPAR database.

Meantime, we used JASPAR database (https://jaspar.genereg.net/) to predict the TF binding profiles of the PTGS2 promoter. Through a distribution histogram to show the number of the binding sites in each base of the PTGS2 promoter, we found that the PTGS2 promoter has more binding sites around these bases (240 bp, 340 bp, 540 bp, 610 bp, 810 bp, 1330 bp, 1380 bp and 1810 bp) (Fig. 4G), implying that these regions might be the core TF binding regions of the PTGS2 promoter. By combining these specific proteins pulled down by each of the five fragments of the PTGS2 promoter with the 1665 all human TFs from JASPAR database, we found that the number of TFs bound with each of the five fragments was 6 (F1), 49 (F2), 2 (F3), 43 (F4) and 4 (F5), respectively. These data together suggest that the core TF binding regions of the PTGS2 promoter might be located in the F2 (499–981 bp) and F4 (1053–1434 bp) two fragments.

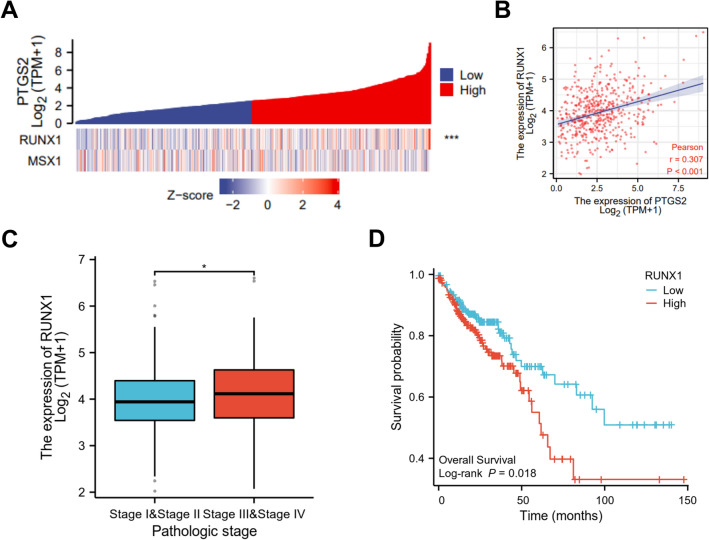

PTGS2 expression positively correlates with the expression of TF RUNX1

Using KnockTF database (http://www.licpathway.net/KnockTF/) to obtain the known TFs in regulating PTGS2 expression, a total of 62 TFs was found based on the screen set threshold of log2FC > 1 (FC > 2) (Supplementary Table 3). To further study the TFs that regulate PTGS2 in HCT116 CRC cells, we combined the 62 known TFs with the TFs pulled down by the PTGS2 promoter in HCT116 cells. Intriguingly, we found two TFs: RUNX1 and MSX1. To observe the correlation between PTGS2 and RUNX1 or MSX1 expression in CRC, we interrogated the TCGA-COAD dataset using National Cancer Institute GDC Data Portal (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). Heat map showed a significant correlation of PTGS2 and RUNX1 expression in COAD samples, while no significant association was found between PTGS2 and MSX1 (Fig. 5A). Pearson’s correlation analysis also confirmed the significant and positive correlation between PTGS2 and RUNX1 expression in COAD samples (r = 0.307, P < 0.001; Fig. 5B). Furthermore, according to the findings reported by Li et al.29, RUNX1 expression was significantly associated with the pathologic stage of the tumors (Fig. 5C), and the high expression of RUNX1 predicted a poorer prognosis of these patients with COAD (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5.

PTGS2 positively correlates with RUNX1. (A) Heat map showing a correlation between PTGS2 and RUNX1 or MSX1 expression using the TCGA-COAD dataset. (B) Scatter plots of PTGS2 expression versus RUNX1 level in 478 patients with COAD using the TCGA-COAD dataset. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) and P value are shown. (C) RUNX1 expression is associated with the pathologic stage of the COAD tumors. (D) Association between RUNX1 expression and the overall survival of these patients with COAD. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001.

RUNX1 acts as a positive regulator of PTGS2 expression by increasing the transcriptional activation of the PTGS2 promoter

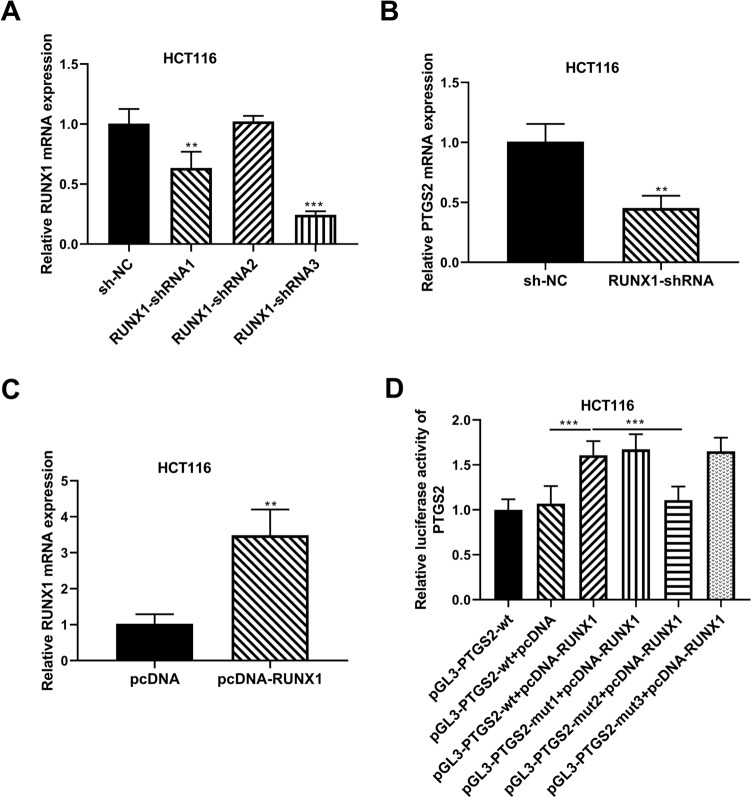

Further, we asked whether RUNX1 regulates PTGS2 expression in HCT116 cells and, if so, how. To address this, we manipulated RUNX1 expression with three shRNAs targeting RUNX1 (RUNX1-shRNA) or a RUNX1 expression plasmid (pcDNA-RUNX1) in HCT116 cells. Transfection of RUNX1-shRNA1 or RUNX1-shRNA3, but not RUNX1-shRNA2, remarkably suppressed the expression of RUNX1 mRNA in HCT116 cells (Fig. 6A). Since RUNX1-shRNA3 led to the most significant downregulation in RUNX1 mRNA expression (Fig. 6A), we selected it for the subsequent research. Inhibition of RUNX1 by RUNX1-shRNA3 introduction significantly repressed cell growth, PCNA expression, migration, invasion, and MMP9 expression in CRC cells (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4). Additionally, reduced expression of RUNX1 led to enhanced cell apoptosis (Supplementary Fig. 2). These findings indicated that RUNX1 knockdown in HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells can recapitulate the same phenotype observed upon PTGS2 knockdown. Interestingly, we observed a clear reduction in the level of PTGS2 mRNA in RUNX1-silenced HCT116 cells (Fig. 6B), indicating that RUNX1 positively regulated PTGS2 expression.

Figure 6.

RUNX1 increases PTGS2 expression by binding to the PTGS2 promoter and promoting its transcriptional activation. (A) qRT-PCR of RUNX1 mRNA expression in HCT116 cells transfected with sh-NC, RUNX1-shRNA1, RUNX1-shRNA2 or RUNX1-shRNA3. Using GAPDH as a reference gene, relative expression of RUNX1 mRNA was calculated by the 2−ΔΔCt method. (B) qRT-PCR of PTGS2 mRNA level in HCT116 cells after transfection by sh-NC or RUNX1-shRNA3. Using GAPDH as a reference gene, relative expression of PTGS2 mRNA was calculated by the 2−ΔΔCt method. (C) qRT-PCR of RUNX1 mRNA expression in HCT116 cells transfected with pLV3-NC or pLV3-RUNX1. Using GAPDH as a reference gene, relative expression of RUNX1 mRNA was calculated by the 2−ΔΔCt method. (D) The wild-type (wt) and mutant-type (mut) PTGS2 luciferase reporter plasmids were constructed and transfected into HCT116 cells with pRL-TK Renilla control vector and pLV3-RUNX1 or pLV3-NC, followed by the analysis of luciferase activity. Firefly luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla activity and expressed as relative luciferase activity. n = three independent experiments performed in triplicate. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Our DNA pull-down results showed that RUNX1 was pulled down by the F2 (499–981 bp) and F4 (1053–1434 bp) fragments of the PTGS2 promoter (Supplementary Table 2), suggesting that RUNX1 might bind to the PTGS2 promoter via the two regions. Using JASPAR database to predict the binding sites between RUNX1 and the PTGS2 promoter, we found that the F2 fragment has no potential binding sites, and the F4 fragment contains three potential binding sites (site 1, 1062–1072 bp: AATTGAGGTAC; site 2, 1086–1096 bp: ATTTCAGGTTT; site 3, 1373–1383 bp: TATTGGGGCTA). To validate the binding of RUNX1 to the PTGS2 promoter, we cloned the F4 fragment of the PTGS2 promoter into the PGL3 vector (pGL3-PTGS2-wt) and analyzed its luciferase activity in the presence of pcDNA-RUNX1. Elevated expression of RUNX1 upon pLV3-RUNX1 transfection, confirmed by qRT-PCR (Fig. 6C), enhanced the luciferase activity of the PTGS2 luciferase reporter in HCT116 cells (Fig. 6D), revealing that RUNX1 can enhance transcriptional activation of the PTGS2 promoter. To elucidate the validity of the three binding sites, we next generated three corresponding mutations (pGL3-PTGS2-mut1, pGL3-PTGS2-mut2 and pGL3-PTGS2-mut3) in each of the three potential sites, respectively. Luciferase assays revealed that site-directed mutation of the binding site 2 significantly abolished the promotion of RUNX1 overexpression in PTGS2 luciferase activity, while the two mutations in binding site 1 and 3 did not affect the effect of RUNX1 (Fig. 6D), demonstrating that transcriptional activation of the PTGS2 promoter by RUNX1 is dependent on the 1086–1096 bp position of the F4 fragment. Together, these results establish that RUNX1 can enhance PTGS2 expression in HCT116 cells by promoting transcriptional activation of the PTGS2 promoter via the 1086–1096 bp binding motif.

Discussion

CRC frequently arises via the progressive accumulation of dysregulation in key genes including oncogenes and anti-tumor genes34. Targeting driver pathways would provide a better opportunity to design more efficient therapeutic interventions for CRC35,36. In the current report, our shRNA silencing experiments confirmed the oncogenic activity of PTGS2 in CRC. Furthermore, we defined RUNX1 as a potent TF activator of PTGS2 expression in CRC cells. We therefore provide evidence that elevated expression of PTGS2 induced by RUNX1 contributes to colorectal tumorigenesis.

Numerous studies have demonstrated the crucial implication of PTGS2 in the carcinogenesis of CRC18,19. For instance, glycosylated PTGS2, a stable PTGS2 form, is prevalently expressed in CRC tumors with high sensibility37. The polymorphism of PTGS2 is related to the risk of CRC38,39. Enhanced expression of intestinal PTGS2 is reported to be an early event in colorectal tumorigenesis39. Moreover, PTGS2 upregulation is associated with poorer CRC-specific survival16,17,40. Therefore, PTGS2 has been proposed as a promising target for CRC prevention and treatment41,42. In this paper, loss-of-function phenotypes of PTGS2 by sh-PTGS2 led to a decrease in CRC cell growth, migration and invasiveness in vitro, suggesting that PTGS2 is a promoting regulator of CRC cell malignant behaviors. A recent study shows that PTGS2 does not affect CRC cell differentiation and metastasis in vivo43. These contradictory conclusions may be attributed to more complex in vivo microenvironments relative to in vitro conditions.

Previous reports indicate that some TFs, such as Ets-1 and KLF4, are able to enhance the expression of PTGS2 by elevating the transcriptional activation of the PTGS2 promoter44,45. Moreover, TFs Sp1 and NRF2 can induce PTGS2 expression in cancer cells46,47. On this basis, we here focused on investigating the TFs that regulate PTGS2 expression in CRC cells. Using DNA pull-down assay and qualitative proteome profiling analysis, we firstly elucidated the TF binding regions of the PTGS2 promoter. Our data indicated that the two fragments (499–981 bp and 1053–1434 bp) of the PTGS2 promoter can bind more TFs than other sequences, suggesting that the two fragments might be the core TF binding profiles of the PTGS2 promoter. Using KnockTF database, RUNX1 seems to be a TF involved in the regulation of PTGS2 expression in CRC cells. Interestingly, we also found a significant positive correlation between PTGS2 and RUNX1 expression in COAD samples. In rat periovulatory granulosa cells and leukemic stem cells, RUNX1 can induce PTGS2 expression by increasing transcriptional activity of the PTGS2 promoter48,49. Similarly, we experimentally showed that RUNX1 operates as a positive regulator of PTGS2 expression in HCT116 CRC cells by promoting transcriptional activation of the PTGS2 promoter via the 1086–1096 bp binding motif. On the other hand, suppression of RUNX1 can lead to an increase in PTGS2 expression in myofibroblasts50. Recent work has uncovered the double-edge role of RUNX1 in the progression of solid tumors by functioning as an oncogenic driver or a tumor suppressor26. These contradictory findings may be in part due to the different tumor types. More interestingly, in CRC, RUNX1 is overexpressed and has been identified as a potent driver in colorectal tumorigenesis28,51; conversely, RUNX1 is reported to work as an anti-cancer factor in gastrointestinal malignancies52,53. Our data suggested the oncogenic role of RUNX1 in CRC (Supplementary Figs. 2–4). These controversial findings may be due to microsatellite instability statues and different microenvironments of gastrointestinal tumor tissues.

Inhibitors of PTGS2 have been proposed as potential agents for CRC prevention and treatment15,41,42. Nevertheless, no major clinical trials of PTGS2 inhibitors were completed in CRC due to their adverse effects, such as elevated risk of myocardial infarction, dyspepsia, abdominal pain, gastrointestinal bleeding, and gastritis19,54. Moreover, it remains unclear how to prevent the potential adverse effects of PTGS2 inhibitors and which CRC patients would benefit the most from these inhibitors. To find more effective targets for PTGS2 inhibition, we investigated the upstream mechanism of PTGS2 regulation in this study and demonstrated that TF RUNX1 is a positive regulator of PTGS2 expression. Our data indicated the reduced effect of RUNX1-shRNA (sh-RUNX1) on PTGS2 level in HCT116 CRC cells. With these findings in our study, the sh-RUNX1 vector appears to represent a potential anti-CRC agent that might function as a suppressor on tumor growth and metastasis in CRC by silencing PTGS2. We envision that RUNX1 inhibitors may have the potential to improve the outcome of patients with CRC. Further work will build on these findings by determining the long-term efficacy and safety of such inhibitors in various experimental models.

In summary, we define that TF RUNX1 enhances PTGS2 expression by elevating transcription activation of the PTGS2 promoter via the 1086–1096 bp binding motif, and as a consequence, promotes CRC cell growth, migration and invasion. Emerging from our study is an increased rationale for the use of PTGS2 inhibitors in CRC prevention and treatment.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

W.Z., Y.G. designed and performed the experiments, wrote the manuscript. A.K., Q.Z., X.H., J.B., Y.L., B.X., X.J. conducted the experiments. G.W., C.Z., Y.Z. revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The present study was supported by Key Research and Development and Promotion Project of Henan Province (Scientific and Technological Project) (No. 212102310703).

Data availability

The data and material presented in this manuscript is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Weiwei Zheng and Yingchang Guo.

Contributor Information

Gang Wu, Email: Gang123wg@163.com.

Chao Zhang, Email: zhangchao65489@126.com.

Yuanzeng Zhu, Email: yuanzengzhu1130@163.com.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-60296-z.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mahmoud NN. Colorectal cancer: Preoperative evaluation and staging. Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2022;31(2):127–141. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2021.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zygulska AL, Pierzchalski P. Novel diagnostic biomarkers in colorectal cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23(2):852. doi: 10.3390/ijms23020852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carethers JM, Jung BH. Genetics and genetic biomarkers in sporadic colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(5):1177–1190.e1173. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.06.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ding D, Han S, Zhang H, He Y, Li Y. Predictive biomarkers of colorectal cancer. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2019;83:107106. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2019.107106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coghlin C, Murray GI. Biomarkers of colorectal cancer: Recent advances and future challenges. Proteomics Clin. Appl. 2015;9(1–2):64–71. doi: 10.1002/prca.201400082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anamthathmakula P, Winuthayanon W. Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTGS2) in the oviduct: Roles in fertilization and early embryo development. Endocrinology. 2021 doi: 10.1210/endocr/bqab025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koki A, Khan NK, Woerner BM, Dannenberg AJ, Olson L, Seibert K, Edwards D, Hardy M, Isakson P, Masferrer JL. Cyclooxygenase-2 in human pathological disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2002;507:177–184. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0193-0_28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liang X, Wu L, Wang Q, Hand T, Bilak M, McCullough L, Andreasson K. Function of COX-2 and prostaglandins in neurological disease. J. Mol. Neurosc. 2007;33(1):94–99. doi: 10.1007/s12031-007-0058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou Y, Zhou H, Hua L, Hou C, Jia Q, Chen J, Zhang S, Wang Y, He S, Jia E. Verification of ferroptosis and pyroptosis and identification of PTGS2 as the hub gene in human coronary artery atherosclerosis. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2021;171:55–68. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2021.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang H, Xuefeng Y, Shandong W, Jianhua X. COX-2 in liver fibrosis. Clin. Chim. Acta Int. J. Clin. Chem. 2020;506:196–203. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang S, Barros SP, Niculescu MD, Moretti AJ, Preisser JS, Offenbacher S. Alteration of PTGS2 promoter methylation in chronic periodontitis. J. Dental Res. 2010;89(2):133–137. doi: 10.1177/0022034509356512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hashemi Goradel N, Najafi M, Salehi E, Farhood B, Mortezaee K. Cyclooxygenase-2 in cancer: A review. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019;234(5):5683–5699. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ye Y, Wang X, Jeschke U, von Schönfeldt V. COX-2-PGE(2)-EPs in gynecological cancers. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020;301(6):1365–1375. doi: 10.1007/s00404-020-05559-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khan Z, Khan N, Tiwari RP, Sah NK, Prasad GB, Bisen PS. Biology of Cox-2: An application in cancer therapeutics. Current Drug Targets. 2011;12(7):1082–1093. doi: 10.2174/138945011795677764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mima K, Nishihara R, Yang J, Dou R, Masugi Y, Shi Y, da Silva A, Cao Y, Song M, Nowak J, et al. MicroRNA MIR21 (miR-21) and PTGS2 expression in colorectal cancer and patient survival. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2016;22(15):3841–3848. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kunzmann AT, Murray LJ, Cardwell CR, McShane CM, McMenamin UC, Cantwell MM. PTGS2 (Cyclooxygenase-2) expression and survival among colorectal cancer patients: A systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prevent. Publ. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. Cosponsored Am. Soc. Prevent. Oncol. 2013;22(9):1490–1497. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nanda N, Dhawan DK. Role of cyclooxygenase-2 in colorectal cancer patients. Front. Biosci. 2021;26(4):706–716. doi: 10.2741/4914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheng J, Sun H, Yu FB, Li B, Zhang Y, Zhu YT. The role of cyclooxygenase-2 in colorectal cancer. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2020;17(8):1095–1101. doi: 10.7150/ijms.44439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Negi RR, Rana SV, Gupta V, Gupta R, Chadha VD, Prasad KK, Dhawan DK. Over-expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in colorectal cancer patients. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prevent. APJCP. 2019;20(6):1675–1681. doi: 10.31557/APJCP.2019.20.6.1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lambert M, Jambon S, Depauw S, David-Cordonnier MH. Targeting transcription factors for cancer treatment. Molecules. 2018;23(6):1479. doi: 10.3390/molecules23061479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huh HD, Kim DH, Jeong HS, Park HW. Regulation of TEAD transcription factors in cancer biology. Cells. 2019;8(6):600. doi: 10.3390/cells8060600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lie ALM, Mevel R, Patel R, Blyth K, Baena E, Kouskoff V, Lacaud G. RUNX1 dosage in development and cancer. Mol. Cells. 2020;43(2):126–138. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2019.0301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doffo J, Bamopoulos SA, Köse H, Orben F, Zang C, Pons M, den Dekker AT, Brouwer RWW, Baluapuri A, Habringer S, et al. NOXA expression drives synthetic lethality to RUNX1 inhibition in pancreatic cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2022 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2105691119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin TC. RUNX1 and cancer. Biochimica et biophysica acta Reviews on cancer. 2022;1877(3):188715. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2022.188715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hong D, Fritz AJ, Gordon JA, Tye CE, Boyd JR, Tracy KM, Frietze SE, Carr FE, Nickerson JA, Van Wijnen AJ, et al. RUNX1-dependent mechanisms in biological control and dysregulation in cancer. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019;234(6):8597–8609. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu C, Yang Z, Yu D, Lin J, Cai W. RUNX1 regulates TGF-β induced migration and EMT in colorectal cancer. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2020;216(11):153142. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2020.153142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Q, Lai Q, He C, Fang Y, Yan Q, Zhang Y, Wang X, Gu C, Wang Y, Ye L, et al. RUNX1 promotes tumour metastasis by activating the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway and EMT in colorectal cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. CR. 2019;38(1):334. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1330-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Q, Lai Q, He C, Zhang H, Pan X, Li H, Yan Q, Fang Y, Liu S, Li A. RUNX1 regulates the proliferation and chemoresistance of colorectal cancer through the Hedgehog signaling pathway. J. Cancer. 2021;12(21):6363–6371. doi: 10.7150/jca.51338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu G, Wang H, Yuan D, Yao J, Meng L, Li K, Zhang Y, Dang C, Zhu K. RUNX1-activated upregulation of lncRNA RNCR3 promotes cell proliferation, invasion, and suppresses apoptosis in colorectal cancer via miR-1301-3p/AKT1 axis in vitro and in vivo. Clin. Transl. Oncol. Off. Publ. Fed. Span. Oncol. Soc. Natl. Cancer Inst. Mexico. 2020;22(10):1762–1777. doi: 10.1007/s12094-020-02335-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Korpal M, Ell BJ, Buffa FM, Ibrahim T, Blanco MA, Celià-Terrassa T, Mercatali L, Khan Z, Goodarzi H, Hua Y, et al. Direct targeting of Sec23a by miR-200s influences cancer cell secretome and promotes metastatic colonization. Nat. Med. 2011;17(9):1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nm.2401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma L, Teruya-Feldstein J, Weinberg RA. Tumour invasion and metastasis initiated by microRNA-10b in breast cancer. Nature. 2007;449(7163):682–688. doi: 10.1038/nature06174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucl. Acids Res. 2001;29(9):e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sjöblom T, Jones S, Wood LD, Parsons DW, Lin J, Barber TD, Mandelker D, Leary RJ, Ptak J, Silliman N, et al. The consensus coding sequences of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science. 2006;314(5797):268–274. doi: 10.1126/science.1133427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng X, Xu X, Chen D, Zhao F, Wang W. Therapeutic potential of targeting the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in colorectal cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019;110:473–481. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.11.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu G, Pei L, Xia H, Tang Q, Bi F. Role of oncogenic KRAS in the prognosis, diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer. Mol. Cancer. 2021;20(1):143. doi: 10.1186/s12943-021-01441-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Venè R, Costa D, Augugliaro R, Carlone S, Scabini S, Casoni Pattacini G, Boggio M, Zupo S, Grillo F, Mastracci L, et al. Evaluation of glycosylated PTGS2 in colorectal cancer for NSAIDS-based adjuvant therapy. Cells. 2020;9(3):683. doi: 10.3390/cells9030683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ross J, Lockett L, Brookes D, Tabor B, Duesing K, Buckley M, Lockett T, Molloy P, Macrae F, Young G, et al. An association between the PTGS2 rs5275 polymorphism and colorectal cancer risk in families with inherited non-syndromic predisposition. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. EJHG. 2013;21(12):1389–1395. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vogel LK, Sæbø M, Høyer H, Kopp TI, Vogel U, Godiksen S, Frenzel FB, Hamfjord J, Bowitz-Lothe IM, Johnson E, et al. Intestinal PTGS2 mRNA levels, PTGS2 gene polymorphisms, and colorectal carcinogenesis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(8):e105254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kosumi K, Hamada T, Zhang S, Liu L, da Silva A, Koh H, Twombly TS, Mima K, Morikawa T, Song M, et al. Prognostic association of PTGS2 (COX-2) over-expression according to BRAF mutation status in colorectal cancer: Results from two prospective cohorts and CALGB 89803 (Alliance) trial. Eur. J. Cancer. 2019;111:82–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benelli R, Venè R, Ferrari N. Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (cyclooxygenase-2), a complex target for colorectal cancer prevention and therapy. Transl. Res. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 2018;196:42–61. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2018.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu Y, Sun H, Hu M, Zhang Y, Chen S, Tighe S, Zhu Y. The role of cyclooxygenase-2 in colorectal carcinogenesis. Clin. Colorectal Cancer. 2017;16(3):165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zahedi T, Hosseinzadeh Colagar A, Mahmoodzadeh H. PTGS2 over-expression: A colorectal carcinoma initiator not an invasive factor. Rep. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2021;9(4):442–451. doi: 10.52547/rbmb.9.4.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang XF, Zhu Y, Liang WB, Zhang JJ. Transcription factor Ets-1 inhibits glucose-stimulated insulin secretion of pancreatic β-cells partly through up-regulation of COX-2 gene expression. Endocrine. 2014;46(3):470–476. doi: 10.1007/s12020-013-0114-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaushik DK, Gupta M, Das S, Basu A. Krüppel-like factor 4, a novel transcription factor regulates microglial activation and subsequent neuroinflammation. J. Neuroinflammation. 2010;7:68. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-7-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu K, Shu HK. EGFR activation results in enhanced cyclooxygenase-2 expression through p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent activation of the Sp1/Sp3 transcription factors in human gliomas. Cancer Res. 2007;67(13):6121–6129. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jessen C, Kreß JKC, Baluapuri A, Hufnagel A, Schmitz W, Kneitz S, Roth S, Marquardt A, Appenzeller S, Ade CP, et al. The transcription factor NRF2 enhances melanoma malignancy by blocking differentiation and inducing COX2 expression. Oncogene. 2020;39(44):6841–6855. doi: 10.1038/s41388-020-01477-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu J, Park ES, Jo M. Runt-related transcription factor 1 regulates luteinized hormone-induced prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 expression in rat periovulatory granulosa cells. Endocrinology. 2009;150(7):3291–3300. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yeh JR, Munson KM, Elagib KE, Goldfarb AN, Sweetser DA, Peterson RT. Discovering chemical modifiers of oncogene-regulated hematopoietic differentiation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009;5(4):236–243. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim W, Barron DA, San Martin R, Chan KS, Tran LL, Yang F, Ressler SJ, Rowley DR. RUNX1 is essential for mesenchymal stem cell proliferation and myofibroblast differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014;111(46):16389–16394. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407097111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rada M, Kapelanski-Lamoureux A, Petrillo S, Tabariès S, Siegel P, Reynolds AR, Lazaris A, Metrakos P. Runt related transcription factor-1 plays a central role in vessel co-option of colorectal cancer liver metastases. Commun. Biol. 2021;4(1):950. doi: 10.1038/s42003-021-02481-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fijneman RJ, Anderson RA, Richards E, Liu J, Tijssen M, Meijer GA, Anderson J, Rod A, O'Sullivan MG, Scott PM, et al. Runx1 is a tumor suppressor gene in the mouse gastrointestinal tract. Cancer Sci. 2012;103(3):593–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.02189.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Voora D, Rao AK, Jalagadugula GS, Myers R, Harris E, Ortel TL, Ginsburg GS. Systems pharmacogenomics finds RUNX1 is an aspirin-responsive transcription factor linked to cardiovascular disease and colon cancer. EBioMedicine. 2016;11:157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koehne CH, Dubois RN. COX-2 inhibition and colorectal cancer. Semin. Oncol. 2004;31(2 Suppl 7):12–21. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2004.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data and material presented in this manuscript is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.