Abstract

Intracellular pH is a valuable index for predicting neuronal damage and injury. However, no PET probe is currently available for monitoring intracellular pH in vivo. In this study, we developed a new approach for visualizing the hydrolysis rate of monoacylglycerol lipase, which is widely distributed in neurons and astrocytes throughout the brain. This approach uses PET with the new radioprobe [11C]QST-0837 (1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoropropan-2-yl-3-(1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)azetidine-1-[11C]carboxylate), a covalent inhibitor containing an azetidine carbamate skeleton for monoacylglycerol lipase. The uptake and residence of this new radioprobe depends on the intracellular pH gradient, and we evaluated this with in silico, in vitro and in vivo assessments. Molecular dynamics simulations predicted that because the azetidine carbamate moiety is close to that of water molecules, the compound containing azetidine carbamate would be more easily hydrolyzed following binding to monoacylglycerol lipase than would its analogue containing a piperidine carbamate skeleton. Interestingly, it was difficult for monoacylglycerol lipase to hydrolyze the azetidine carbamate compound under weakly acidic (pH 6) conditions because of a change in the interactions with water molecules on the carbamate moiety of their complex. Subsequently, an in vitro assessment using rat brain homogenate to confirm the molecular dynamics simulation-predicted behaviour of the azetidine carbamate compound showed that [11C]QST-0837 reacted with monoacylglycerol lipase to yield an [11C]complex, which was hydrolyzed to liberate 11CO2 as a final product. Additionally, the 11CO2 liberation rate was slower at lower pH. Finally, to indicate the feasibility of estimating how the hydrolysis rate depends on intracellular pH in vivo, we performed a PET study with [11C]QST-0837 using ischaemic rats. In our proposed in vivo compartment model, the clearance rate of radioactivity from the brain reflected the rate of [11C]QST-0837 hydrolysis (clearance through the production of 11CO2) in the brain, which was lower in a remarkably hypoxic area than in the contralateral region. In conclusion, we indicated the potential for visualization of the intracellular pH gradient in the brain using PET imaging, although some limitations remain. This approach should permit further elucidation of the pathological mechanisms involved under acidic conditions in multiple CNS disorders.

Keywords: hydrolysis, hypoxia, intracellular pH, monoacylglycerol lipase, PET

Yamasaki et al. report the development of [11C]QST-0837 as a novel PET ligand for quantification of monoacylglycerol lipase activity and its potential for in vivo visualization of intracellular pH gradient in the brain using PET imaging.

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

Cerebral vascular hypoxia damages the CNS1–4 by switching aerobic energy metabolism to anaerobic metabolism, resulting in intracellular hyperaccumulation of acidic residues such as protons, lactate and carbonic acid.5 Subsequently, the neuronal synapse is depolarized by the disproportion of cations (Na+ and K+) because the production of ATP decreases under anaerobic metabolism. The intracellular Ca2+ concentration then increases and excess neurotransmitters (e.g. glutamate) are released, inducing neurotoxicity, neuroinflammation and neuronal death.6,7 Such acute damage can lead to a number of pathologies such as depression, post-stroke dementia and, potentially, neurodegeneration.3 Therefore, monitoring changes in intracellular pH (pHi), which depend on the intracellular accumulation of acidic sources, should be very important for predicting neuronal damage in the early stage of several CNS disorders.

PET is an advanced imaging technique that is widely used in basic and clinical studies to elucidate the kinetics, molecular density and distribution of drugs in vivo. To date, only two major radioprobes have been developed for pH-weighted PET imaging. Four decades ago, [11C]dimethyloxazolidinedione ([11C]DMO), the membrane permeability of which depends on the pH gradient, was first developed as a pH-weighted marker for PET studies.8,9 However, PET imaging with [11C]DMO was inaccurate because the biodistribution of [11C]DMO could not distinguish between plasmalemmal, intracellular and extracellular pH gradients.2 Two decades later, [64Cu]DOTA-pHLIP, which specifically binds to the membranes of low-pH cells, was identified.10 However, the binding of [64Cu]DOTA-pHLIP depends on the extracellular pH gradient, but not on the pHi. To the best of our knowledge, no pHi-sensitive PET probe is currently available for use in humans.

Recently, Butler et al.11 reported azetidine and piperidine carbamates as covalent inhibitors of monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL), an enzyme widely distributed throughout the mammalian brain and a key enzyme for regulation of the endocannabinoid system. Our group recently developed radiolabelled azetidine carbamate inhibitors for use as PET probes for imaging of MAGL (Supplementary Fig. 1A). Although they were designed as irreversible PET probes, they showed unexpected rapid radioactivity clearance after a high initial uptake of radioactivity in the brain, similar to that shown by reversible PET probes.12–14 Such brain kinetics strongly suggest that carbamate inhibitors covalently bind to MAGL, resulting in unstable complexes in the brain. In this study, following information in a previous report,15 we hypothesized a disassociation mechanism (Fig. 1A) for [11C]azetidine carbamates in the brain. [11C]Azetidine carbamate covalently reacts with MAGL to form an [11C]complex, which is subsequently hydrolyzed, resulting in 11CO2 as a final radioactive product. Because 11CO2 is rapidly cleared from the brain,16 we considered that the radioactivity clearance rate would depend mainly on the rate of hydrolysis of the [11C]complex within the brain.

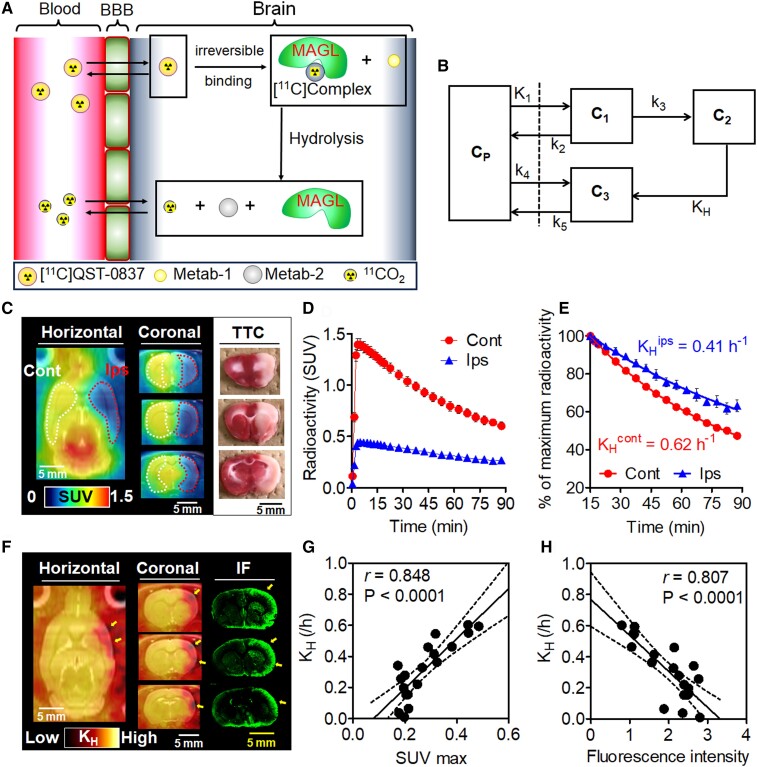

Figure 1.

The hypothesized mechanism for hydrolysis of the 11C-labelled MAGL inhibitor containing an azetidine carbamate skeleton. (A) Proposed disassociation route for the 11C-labelled MAGL inhibitor containing an azetidine carbamate moiety. (B) Diagram illustrating the effect of acidic sources on 11CO2 production.

Enzyme activity is reduced at pH values outside the optimal range, generally because changes in pH affect enzyme–substrate complex formation, substrate ionization and the 3D structure of enzymes. More importantly, MAGL is widely expressed throughout the brain and is intracellularly localized not only in pre- and post-synaptic neurons, but also in astrocytes.17,18 Therefore, estimation of the 11CO2 production rate through hydrolysis of the [11C]complex formed between azetidine and MAGL may permit monitoring of regional changes in pHi within the brain (Fig. 1B).

Following on from this insight, we developed 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoropropan-2-yl-3-(1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)azetidine-1-[11C]carboxylate ([11C]QST-0837; IC50 = 0.2 nM) as a novel radioprobe for visualizing the pHi gradient. For comparison with [11C]QST-0837, we simultaneously synthesized its piperidine analogue (1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoropropan-2-yl-4-(1-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)piperidine-1-[11C]carboxylate; [11C]HPPC; IC50 = 2.0 nM). We first performed molecular dynamics (MD) simulations for the complexes between azetidine carbamate or piperidine carbamate compounds and MAGL and then confirmed their structural relationship with in vivo hydrolytic instability. Subsequently, we radiosynthesized [11C]QST-0837 and [11C]HPPC and tested their ability to measure the pHi gradient in vitro and in vivo.

Materials and methods

General

All chemical reagents and organic solvents were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Industries (Osaka, Japan), or Nacalai Tesque (Kyoto, Japan) and were used without further purification. 11C was produced using a cyclotron (CYPRIS HM-18; Sumitomo Heavy Industries, Tokyo, Japan).

Animals

Male Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats (n = 24, 7–10 weeks old) weighing 280–350 g were purchased from Japan SLC (Shizuoka, Japan), kept in a temperature- and humidity-controlled environment with a 12-h light–dark cycle and allowed to freely consume a standard diet (MB-1/Funabashi Farm, Chiba, Japan) and water. All animal experiments were performed according to the recommendations specified by the Committee for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology (QST) and Animal Research and the Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines and were approved by the Institutional Committee of QST (approval number: 16-1006).

MD simulations

A 3D MAGL structure (PDB code: 6AX1), including the ligand-binding domain, was used for modelling and MD simulations. The initial structures of the carbamate inhibitor (MAGL complexes) (complex-A for azetidine carbamate and complex-P for piperidine carbamate) were constructed based on model ligands (compound-A for azetidine carbamate and compound-P for piperidine carbamate) in the homology module of the molecular modelling software MOE (Chemical Computing Group, Montreal, Canada). MD simulations for complex-A were conducted under neutral (pH 7) and weakly acidic (pH 6) conditions. Under neutral conditions, Asp and Glu residues and the C-terminus of MAGL were kept deprotonated (COO−, Lys and Arg residues), the N-terminus of the protein was kept protonated and the His residues of MAGL were kept deprotonated. Under weakly acidic conditions, the His residues of MAGL were protonated.

The complex-A and complex-P were solvated in a truncated octahedral TIP3P water box with a thickness of 8 Å around the complex. Then, protein.ff14SB, water.tip3p and a general amber force field were used as force fields. The systems were neutralized by adding Na+ ions as the counter ions. The energy minimized (MM) calculations and MD simulations were performed using AMBER18/PMEMD with periodic boundary conditions of constant temperature (300 K) and pressure (1 atm) and a non-bonded interaction cut-off distance of 8 Å. The particle mesh Ewald method was employed to calculate the electrostatic interactions. After tethering the heavy atoms of the protein, the MM calculations of the system were performed in 1000 steps using the steepest descent and conjugated gradient methods. MD simulations were performed only for water molecules in the system within a 50 ps time frame, whilst increasing the temperature from 0 to 300 K. Subsequently, the Cα atoms of the protein were tethered, and then, MM calculations of the side chain of the protein were performed in 1000 steps using the steepest descent method and in 10 000 steps using the conjugated gradient method. MD calculations for the Cα atoms of the protein were performed under the same conditions as described above. MM calculations for the system were performed in 1000 steps using the steepest descent method and in 10 000 steps using the conjugated gradient method. Finally, the MM calculations and MD simulations were performed for the entire system. Atoms were heated from 0 to 300 K at 50 ps intervals, and the whole system reached the equilibrium state for MD simulation (5 ns) of the complex structures under constant temperature (300 K) and pressure (1 atm). For each complex, structural changes were evaluated using the root mean square deviation (RMSD) of the trajectory of the intermediate structures in the MD simulations.

Radiochemistry

11CO2 was produced via 14N(p, α)11C nuclear reactions using a cyclotron (Cypris HM18, Sumitomo Heavy Industries) and was transferred into a pre-heated mechanizer packed with a nickel catalyst at 400°C to produce 11CH4, which was subsequently reacted with chlorine gas at 560°C to generate 11CCl4. 11COCl2 was produced via the reaction of 11CCl4 with iodine oxide and sulphuric acid and was trapped in a solution of 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoropropan-2-ol (3.1 μl) and 1,2,2,6,6-pentamethylpiperidine (PMP; 5.4 μl) in tetrahydrofuran (200 µl) at 0°C.19 The solution was then heated to 30°C for 3 min. A solution of precursors of [11C]QST-0837 or [11C]HPPC (1.00 mg, see Supplementary Fig. 2) with PMP (2.3 µl) in tetrahydrofuran (200 µl) was added to the mixture and heated at 30°C for 3 min, and the solvent was then removed at 80°C before cooling to room temperature (r.t.) (Supplementary Fig. 3A). After dilution with 1 ml of separation solvent, the mixture was purified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC; CAPCELL Pak C18 column; 10 mm i.d. × 250 mm, 5 µm) using a mobile phase of CH3CN/H2O/Et3N (70/30/0.1, v/v/v, for [11C]QST-0837) or CH3CN/H2O/TFA (75/25/0.1, v/v/v, for [11C]HPPC) at a flow rate of 5.0 ml/min. The respective retention times were 11.0 min for [11C]QST-0837 and 11.7 min for [11C]HPPC. The HPLC fractions of [11C]QST-0837 and [11C]HPPC were collected in a flask containing 25% ascorbic acid in sterile water (100 µl), and Tween 80 (75 µl) in ethanol (0.3 ml) was added before synthesis and evaporation to dryness. The final product was collected in a sterile flask and reformulated in sterile normal saline (2 ml). The resulting compound was analysed using HPLC with a UV detector of 254-nm wavelength and a radioactivity detector. The radiochemical and chemical purities were measured by analytical HPLC (CAPCELL Pak C18 column; 4.6 mm i.d. × 250 mm, 5 µm) as a mobile phase of CH3CN/H2O/Et3N (70/30/0.1, v/v/v, for [11C]QST-0837) or CH3CN/H2O/TFA (75/25/0.1, v/v/v, for [11C]HPPC), at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min. The identification of [11C]QST-0837 and [11C]HPPC was confirmed by co-injection with compound-A or compound-P, respectively, and the retention times in radio-HPLC analyses were 10.3 min for [11C]QST-0837 and 10.8 min for [11C]HPPC. The calculated lipophilicities (cLogP) of each radioligand were estimated using ChemBioDraw Ultra (version 12.0; PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA).

In vitro 11CO2 collection assay

Six rats were anesthetized with isoflurane (1–5% in air) and exsanguinated. The brain was quickly removed and homogenized with three equivalents of saline using a homogenizer (Silent Crasher S; Heidolph, Schwabach, Germany). The homogenate (6 ml) was added to a conical flask containing saline (2 ml) and lactic acid (1 ml) at various concentrations (0, 10, 30, 50 and 100 mM). The flask was closed with a rubber plug through which were inserted glass tubes to allow bubbling. An in vitro 11CO2 collection assay was performed according to a previous report with modification.20 Briefly, [11C]QST-0837 (1 ml, 10–18 MBq) or [11C]HPPC (1 ml, 10–11 MBq) was added to the flask and it was incubated in a 37°C water bath with shaking for 60 min. During the incubation, a tube was inserted into the bottle containing 10 ml of 2-aminoethanol (50% in distilled water). The air for bubbling was then automatically browsed using an air pump connected to another tube. The bottle was then changed for a new one after 5 min. Before stopping the enzymatic reaction, the pH of the brain homogenates was measured using a pH metre (Elite pH Spear Pocket Testers; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Subsequently, pre-chilled CH3CN (10 ml) was quickly added to the flask to stop the enzymatic reaction and the mixture was separated into several micro-tubes. The micro-tubes were centrifuged at 10 000 g, and the supernatants were transferred into new micro-tubes. An autogamma scintillation counter (2480 WIZARD2; PerkinElmer) was used to measure the radioactivity levels of the bottle for collecting 11CO2, the pellet and the supernatant. Radioactivity is expressed as a percentage of the incubation dose (%ID).

Permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion surgery

The permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) model was established in 10 rats. The rats were anesthetized with isoflurane (1.5% in air) and their body temperature was maintained at approximately 37°C using a heating pad (BWT-100; Bio Research Center Co., Ltd., Aichi, Japan). The MCAO surgery was performed using the Koizumi method.21 Briefly, using a surgical microscope (CLS 150MR; Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany), a silicon-coated monofilament (Doccol Corporation, Sharon, MA, USA) was introduced into the internal carotid artery via a cut in the external carotid artery and was passed until the monofilament occluded the MCAO base. After 1, 3–4, or 6 h of occlusion, the rats were used for the PET imaging study.

Small-animal PET imaging

Before PET assessment, the rats were anesthetized with isoflurane (5% in air) and a 24-gauge intravenous catheter (Terumo Medical Products, Tokyo, Japan) was inserted into their tail vein. For the blocking study, compound-A (unlabelled QST-0837), compound-P (unlabelled HPPC) and JW642 (MedChemExpress, Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA) in different doses (1 or 3 mg/kg) were administered via the tail vein catheter 30 min before the injection of the radioprobe.12,13 Subsequently, the rats were secured in a custom-designed chamber and placed in a small-animal PET scanner (Inveon; Siemens Medical Solutions, Knoxville, TN, USA). Their body temperatures were maintained using a 40°C water circulation system (T/Pump TP401; Gaymar Industries, Orchard Park, NY, USA). A bolus of [11C]QST-0837 (1 ml, 52–57 MBq, 0.3–0.9 nmol) or [11C]HPPC (1 ml, 41–60 MBq, 1.0–1.2 nmol) was injected at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min via the tail vein catheter. For the chase study, JW642 at 1 mg/kg was administered via the tail vein catheter 20 min after a bolus injection of radioprobe. Dynamic emission scanning in 3D list mode was performed for 90 min (1 min × 4 frames, 2 min × 8 frames and 5 min × 14 frames). The acquired dynamic PET images were reconstructed by filtered back-projection using a Hanning filter with a Nyquist cut-off of 0.5 cycles/pixel. The time–activity curves (TACs) of [11C]QST-0837 and [11C]HPPC were manually acquired for volumes of interest (VOIs) in the cerebral cortex, striatum (caudate/putamen), hippocampus, thalamus, pons and cerebellum, by referring to a rat brain MRI template in PMOD software (version 3.4; PMOD technology, Zurich, Switzerland). For the MCAO model, VOIs were manually drawn on both the ipsilateral and contralateral sides of the brain by visually assigning the affected regions. The radioactivity was decay-corrected to the injection time and is expressed as the standardized uptake value (SUV).22 The rate of hydrolysis (KH) was estimated by a one-exponential fitting on the TACs from 15–90 min, as follows:

| (1) |

| (2) |

In vivo mapping scaled with the relative KH value was generated as follows:

Frames from 3 to 10 (2–15 min) in PET dynamic images are averaged, which are regarded as the apparent maximum uptake of radioactivity.

Frames from 11 to 26 (15–90 min) in PET dynamic images are averaged.

Image for total volume of the efflux of radioactivity from the brain can be reconstructed by subtracting (2) from (1).

Images scaled with relative KH value are obtained by dividing (3) by (1).

All procedures were conducted using fusion tool of PMOD software.

2,3,5-Triphenyl tetrazolium chloride staining

After PET scanning, the rats were euthanized by cervical dislocation. The brain was quickly removed, placed on a brain slicer (EMJapan Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and cut into 2-mm coronal sections. The sections were incubated in 2% 2,3,5-triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC, dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline) for 20 min at r.t.

Immunofluorescent staining for hypoxia

Tissue hypoxia levels were assessed using Hypoxyprobe™ (Hypoxyprobe Inc., Burlington, MA, USA) immunofluorescence staining.23 Briefly, after MCAO rats were occluded for 4 h, Hypoxyprobe™ (60 mg/kg body weight) was injected intraperitoneally. The rats were sacrificed after a PET scan (90 min) and their brains were quickly removed and frozen on powdered dry ice. Coronal brain sections were cut at −20°C using a cryostat (NX50; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and mounted on MAS-coated glass slides (Matsunami-glass, Osaka, Japan). Cryo-sections were prepared with a 20 μm thickness and a 100 μm distance between two adjacent sections. For the assay, brain sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS for 15 min at r.t. and then blocked with blocking serum for 20 min at r.t. The sections were incubated with anti-hypoxyprobe mouse IgG as the primary antibody for 30 min at r.t. After thorough washing, the sections were incubated with a biotinylated secondary antibody (1:100) for 30 min at r.t., followed by fluorescent staining using a TSA fluorescence system (PerkinElmer). The slides were then mounted with medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). The fluorescent signals and areas with fluorescent staining in regions of interest (ROIs) shown in Supplementary Fig. 4 were quantified using ImageJ software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/). The fluorescence intensities were compared with KH values estimated on TACs acquired from VOIs on brain slices adjacent from ROIs drawn as Supplementary Fig. 4 in the same individual in the PET study using [11C]QST-0837.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 5.0; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Differences between means were assessed as appropriate, using two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc analysis.

Results

MD simulations

To understand the in vivo hydrolytic instability of complex-A, we performed MD simulations under neutral conditions similar to normal physiological conditions and compared the results between complex-A and complex-P (Fig. 2A–F). The RMSD values for complex-A and complex-P showed no significant changes in MD simulations (5 ns) under constant temperature (300 K; Fig. 2B and E). Because water is essential for the enzyme hydrolysis, we further analysed the accessibility of water molecules to the respective complexes. By forming hydrogen bonds, His269 and His121 in MAGL were able to capture the water surrounding the carbonyl moiety in both complexes. However, the water molecule was closer to the carbonyl moiety of complex-A (3.4 Å) than to that of complex-P (4.2 Å). Moreover, a hydrogen bond was formed between complex-A and Cys242 in MAGL, which was absent in the case of complex-P because of the longer distance (5.0 Å). These differences indicated that complex-A was hydrolyzed more easily than complex-P. Moreover, the structural strain of the azetidine skeleton is larger than that of the piperidine skeleton, leading to easier hydrolysis.

Figure 2.

MD simulations. (A) Chemical structures of compound-A and its MAGL complex. (B) Chart of the RMSD values for main chain atoms of complex-A in the MD simulations (5 ns) under neutral conditions. (C) 3D structures of complex-A. (D) Chemical structures of compound-P and its MAGL complex. (E) Chart of RMSD values for main chain atoms of complex-P in the MD simulations. (F) 3D structures of complex-P. (G) Overlaid structures of complex-A composed from MD simulations at pH 7 and pH 6. (H) Changes in the interaction of complex-A with water molecules between neutral (pH 7) and weakly acidic (pH 6) conditions. Spatial localization and interaction of the residue of complex-A with a water molecule at pH 7 (left). Changes in the interaction between the residue of complex-A and a water molecule at pH 6 (right). Hydrogen bonds in the complexes are shown as dotted lines. MD simulations were performed using 3D structures of MAGL (PDB: 6AX1).

As mentioned above, enzyme activity is generally weakened by divergence from the optimum pH. Therefore, in the present study, we also compared the interaction of complex-A with water molecules at pH values between neutral (pH 7) and weakly acidic (pH 6). The RMSD value calculated by overlaying the final structures of the MAGL main chain between pH 6 and pH 7 was 1.9 Å (Fig. 2G), suggesting that the in vivo binding affinity of compound-A for MAGL would not change at pH 6. By estimating the distance between the carbonyl moiety and the water molecule, we found that the imidazole ring in His269 of MAGL could form a hydrogen bond with water molecules under neutral conditions (Fig. 2H). However, at pH 6, water molecules would have difficulty accessing the carbonyl moiety because they would not be captured by the imidazole ring in MAGL, thus enhancing the stability of complex-A against hydrolysis. Moreover, His269 in MAGL maintained a strong electronic interaction with Asp239 in MAGL under the weakly acidic condition. This was possibly due to the protonation of the imidazole ring in His269 under such conditions, conditions that would also hinder the hydrolysis of complex-A.

Radiochemistry

To validate our proposed pHi gradient detection approach shown in Fig. 1B, we radiosynthesized [11C]QST-0837 and [11C]HPPC according to the methods in our previous report, using 11COCl2 as a labelling agent.19 Starting with 30 GBq of 11CO2, [11C]QST-0837 and [11C]HPPC were synthesized with 0.9 ± 0.5 GBq (3.1 ± 1.5%) and 1.1 ± 0.6 GBq (4.3 ± 2.3%) at the end of synthesis (EOS), respectively. The radiochemical purities of [11C]QST-0837 and [11C]HPPC were >98%, and the molar activities at the EOS were 101 ± 24 GBq/μmol for [11C]QST-0837 (n = 11) and 62 ± 13 GBq/μmol for [11C]HPPC (n = 5). No radiolysis was observed up to 90 min after formulation, suggesting the radiochemical stability of [11C]QST-0837 and [11C]HPPC over the duration of at least one PET scan. General chemical profiles (molecular weight, lipophilicity and IC50 value for MAGL) for [11C]QST-0837 and [11C]HPPC are shown in Supplementary Fig. 3B.

In vitro 11CO2 collection assay

To confirm the production of 11CO2 resulting from MAGL hydrolysis, we conducted in vitro 11CO2 collection assessments for [11C]QST-0837 and [11C]HPPC using rat brain homogenate (Fig. 3A). Figure 3B shows the radioactivity in three divided compartments (C1: unbound radioprobe, C2: complex with MAGL and C3: 11CO2 as a final product). In the C1 compartment representing the unreacted radioprobe, the radioactivity of [11C]QST-0837 was almost eliminated (<5%ID), whereas that of [11C]HPPC remained at over 50%ID. The radioactivity in the C2 compartment representing the [11C]complex-A or [11C]complex-P was approximately 35%ID for both. These results suggest that the reaction between each radioprobe and MAGL reached a saturation dose of approximately 35%ID. More importantly, production of 11CO2 was detected with [11C]QST-0837 (approximately 35%ID), but not with [11C]HPPC (<1%ID). This result indicates that [11C]complex-A was hydrolyzed under the test conditions, resulting in 11CO2, whereas [11C]complex-P was not hydrolyzed.

Figure 3.

In vitro 11CO2 collection assay using rat brain homogenate. (A) Schematic illustration and compartments of the assay. (B) Radioactivity (percentage of incubation dose, %ID) derived from [11C]QST-0837 or [11C]HPPC in the three divided compartments (C1: unbound, C2: complex and C3: product). Data from three independent experiments for each radioprobe are shown as mean ± SD. NS: Not significant, ***P < 0.001 (two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test). (C) Radioactivity (%ID) derived from [11C]QST-0837 in the presence of different concentrations (0, 10, 30, 50 and 100 mM) of lactic acid (LA). Data from four independent experiments for each LA concentration are shown as mean ± SD. NS: Not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 (two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test). (D) The pH-response curve for 11CO2 production rate. The pH evoking half the maximal 11CO2 production was 5.3.

We subsequently determined the effect of pH on the rate of 11CO2 production using an in vitro 11CO2 collection assay with multiple concentrations of LA. Figure 3C shows the radioactivity generated in each compartment at different pH values. In the C3 compartment, radioactivity gradually decreased with a lowering of pH. The pH evoking half the maximal 11CO2 production was 5.3 (Fig. 3D). In contrast, the radioactivity in the C2 compartment was approximately 40%ID with all LA concentrations except for 100 mM (pH 4.8), which resulted in a large decrease in radioactivity, similar to that in the C3 compartment. However, the radioactivity in the C1 compartment after treatment with 100 mM LA increased to >60%ID. These results suggest that under severely acidic conditions, the 11CO2 production rate is slow (<pH 4.8) and the binding affinity of [11C]QST-0387 to MAGL is decreased.

PET imaging in healthy rats

Figure 4A–D show representative PET images and TACs of [11C]QST-0837 and [11C]HPPC across brain regions. PET images of both radioprobes showed widespread radioactive signals throughout the brain. For [11C]QST-0837, the radioactivity showed a gradual clearance after the initial uptake. However, [11C]complex-P was not hydrolyzed in vivo and the radioactivity remained at 1.0–1.4 SUV without clearance at 15 min post-injection. The highest radioactive uptake for [11C]QST-0837 was 1.6–1.9 SUV in each investigated region, which was slightly higher than that of our previously developed [11C]compound 6 (1.4–1.7 SUV). This was possibly because of the adequate lipophilicity (cLogP = 3.36) and the 2-fold higher affinity of [11C]QST-0837 (IC50 = 0.2 nM) to MAGL compared with that of [11C]compound 6 (IC50 = 0.4 nM).14

Figure 4.

PET imaging in the brain of a healthy rat. (A) Representative 0–90 min summed PET–MRI images of [11C]QST-0837. (B) Time–activity curves (n = 4) of [11C]QST-0837 in the cerebral cortex, striatum, hippocampus, thalamus, pons/medulla and cerebellum. (C) Representative 0–90 min summed PET–MRI images of [11C]HPPC. (D) Time–activity curves (n = 4) of [11C]HPPC in the cerebral cortex, striatum, hippocampus, thalamus, pons/medulla and cerebellum. (E and F) Chase studies of [11C]QST-0837 and [11C]HPPC using an irreversible-type inhibitor for MAGL (JW642). (E) Time–activity curves (n = 3) of [11C]QST-0837 in the brain of rat treated with JW642 (1 mg/kg, i.v.) 20 min after the scan started. (F) Time–activity curves (n = 3) of [11C]HPPC in the brain of rat administered with JW642 (1 mg/kg, i.v.) 20 min after the scan started. ROIs were drawn in the cerebral cortex, striatum, hippocampus, thalamus, pons and cerebellum. Radioactivity is expressed as the SUV. Co, cerebral cortex; St, striatum; Hi, hippocampus; Th, thalamus; Po, pons/medulla; Ce, cerebellum.

Figure 4E shows chase studies of [11C]QST-0837 and [11C]HPPC to determine the irreversible binding of these radioprobes for MAGL. In this study, the commercial inhibitor JW642 was used as a potent irreversible inhibitor for MAGL because of its structural similarity. Pre-treatment with 1 mg/kg JW642 (i.v.) significantly decreased brain uptake of both radioprobes, the same as self-blocking (Supplementary Fig. 5). However, there were no changes in the radioactive uptake of either radioprobes when JW642 was post-administered, which strongly suggests that [11C]QST-0837 and [11C]HPPC are irreversibly bound to MAGL in brain tissue.

Estimation of hydrolysis rate (KH) in PET with [11C]QST-0837

Here, we propose a compartment model (Fig. 5A and B) to understand the dynamics of [11C]QST-0837 in the brain, based on the results of the PET studies using healthy rats and the predicted transformation of [11C]azetidine carbamate shown in Fig. 1A. When [11C]QST-0837 is injected, it enters the bloodstream, reaches the brain capillaries (CP), passively crosses (K1) the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and enters brain tissue (C1). Subsequently, [11C]QST-0837 irreversibly binds (k3) to intracellular MAGL to form [11C]complex-A (C2 compartment), which gradually hydrolyzes (KH), producing 11CO2 (C3 compartment), and the radioactivity from 11CO2 is rapidly cleared (k5) from the brain tissue. Theoretically, when the input function of the radioactivity is close to a negligible value (e.g. 15 min after the injection), the clearance rate of radioactivity in the TAC would depend on KH and the efflux rate (k5) of 11CO2. The efflux rate of 11CO2 has been reported to be 1.74 min−1 in the brains of healthy humans,16 which is very rapid. Therefore, in our PET experiment, we considered the clearance rate of the radioactivity on PET with [11C]QST-0837 to be the KH value. Here, the clearance rate of the radioactivity is simply estimated by a mono-exponential fitting with a non-linear least squares regression.24 In the brain of healthy rat, the radioactivity clearance rates (≈KH) were 0.66 ± 0.06 h−1 for the cerebral cortex, 0.75 ± 0.05 h−1 for the striatum, 0.71 ± 0.05 h−1 for the hippocampus, 0.71 ± 0.05 h−1 for the thalamus, 0.72 ± 0.07 h−1 for the pons/medulla and 0.69 ± 0.08 h−1 for the cerebellum. Interestingly, although differences of initial radioactive uptakes were observed in individuals and brain regions, the clearance rate was the similar level in all subjects and investigated brain regions. Additionally, there was no relationship between estimated maximum radioactive uptake and clearance rate (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Figure 5.

PET imaging in the brain of a MCAO rat. (A) Diagrammatic reasoning of the clearance of radioactivity starting from [11C]QST-0837. (B) Schematic of a compartment model for estimation of the kinetic parameters of the radioactivity. CP: free radioactive compounds containing [11C]QST-0837 and 11CO2 in the plasma; C1: free and non-specific binding of [11C]QST-0837 in the brain tissue; C2: state under [11C]complex-A; C3: 11CO2 as the final product of hydrolysis in the brain tissue; K1: influx rate of [11C]QST-0837; k2: efflux rate of [11C]QST-0837; k3: association rate of [11C]QST-0837 to MAGL; KH: hydrolysis rate of MAGL; k4: reuptake rate of 11CO2; k5: efflux rate of 11CO2 from the brain side. (C) Representative PET images with [11C]QST-0837 and TTC staining in the brains of rats subjected to MCAO for 3–4 h. PET images were generated by summing for 0–90 min after injection and scaling with the SUV. The brain slices were prepared after the PET scan and were stained using TTC. (D) Time–activity curves (TACs) of [11C]QST-0837 in contralateral (Cont) and ipsilateral (Ips) sides. (E) Clearance rate of radioactivity in contralateral (Cont) and ipsilateral (Ips) sides. Radioactivity is expressed as the percentage of maximum radioactivity (SUV of 15 min). KH was generated using a mono-exponential fitting. (F) PET images scaled with relative KH value and immunofluorescent (IF) images reflecting hypoxic regions in the MCAO rat brains. Arrows indicate areas of intense reduction in KH value and strong fluorescent signals. (G) Correlation plots between the maximum SUV value (SUV max) in TACs acquired from VOIs on brain slice adjacent from ROIs (shown in Supplementary Fig. 4) for quantification of immunohistochemical signals and KH values estimated on their TACs. (H) Correlation plots between quantitative values for immunohistochemical signal in ROIs (shown in Supplementary Fig. 4) on three slides and KH values estimated on TACs obtained from VOIs on brain slice adjacent from these ROIs. Relationship tests were conducted by a linear regression.

PET imaging for measurement of pHi in the brains of experimental stroke model rats

Figure 5C and D show representative averaged PET images of [11C]QST-0837 and TACs for the ipsilateral and contralateral sides of the brains of MCAO rats subjected to 3–4-h occlusion. Radioactive signals disappeared from the ipsilateral side of the forebrain, including the cortex, striatum and amygdala, which appeared as light (white) areas after TTC staining. Additionally, the initial radioactive uptake in the ipsilateral area was approximately 30% of that in the contralateral side. This indicates that the cerebral blood flow (CBF) on the ipsilateral side dropped by 70%. Figure 5E shows a plot of the radioactive clearance in the ipsilateral and contralateral sides of the brains of MCAO rats, including the results of mono-exponential regression analyses. The KH values of [11C]complex-A in the ipsilateral and contralateral sides were 0.41 and 0.62 h−1, respectively. In MCAO rats with 3–4 h of occlusion, the KH value in the ipsilateral area was 34% lower than that in the contralateral area. Furthermore, the KH values of rats with 1 and 6 h of occlusion were 0.53 and 0.49 h−1, respectively, in the ipsilateral sides and 0.66 and 0.63 h−1 in the contralateral sides. The KH value on the ipsilateral side was 25% lower than that on the contralateral region at 1 h after occlusion and 17% lower at 6 h after occlusion (Table 1). These results correspond with previously reported values for time-dependent changes in intracellular lactate levels in the MCAO model.25–27

Table 1.

Hydrolysis rate (KH) of MAGL in pMCAO rats

| K H (h−1) | Occlusion time (h) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 a | 3–4 b | 6 a | |

| Contralateral region | 0.62 ± 0.07 | 0.62 ± 0.05 | 0.67 ± 0.07 |

| Ipsilateral region | 0.47 ± 0.10* | 0.41 ± 0.07*** | 0.56 ± 0.11 |

| Ips/Cont ratio | 0.75 ± 0.10 | 0.66 ± 0.07 | 0.83 ± 0.10 |

a n = 3. b n = 4. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 (contralateral versus ipsilateral).

The lower KH value reflects anaerobic glycolysis and intracellular acidosis, and therefore, we further investigated heterogeneous KH values during hypoxia in the brains of MCAO rats at 3–4-h occlusion. Moreover, we compared the KH values in brain regions with immunofluorescent signals corresponding to hypoxia. As shown in Fig. 5F, low KH values were detected in the upper lip region of the primary somatosensory cortex, secondary somatosensory cortex, insular cortex and piriform cortex, all of which correspond to regions that suffer a severe reduction in CBF following MCAO.28 In these regions, the maximum SUV value was also low and positively correlated with the KH value (Fig. 5G). Moreover, immunofluorescent signals on slides corresponding to ROIs in the PET images showed a strong negative correlation (r > 0.8, P < 0.0001) with KH values (Fig. 5H).

Discussion

In this study, we developed 11COCl2-labelled azetidine carbamate ([11C]QST-0837), which targets MGAL. Then, utilizing the discovery that [11C]QST-0837 is slowly hydrolyzed by MAGL, we successfully demonstrated in vivo mapping of pHi according to the hydrolytic activity of MAGL in the brains of MCAO rats.

To investigate why the radiolabelled covalent MAGL inhibitors containing an azetidine carbamate skeleton (developed as an irreversible-type PET probe) showed unexpected clearance of radioactivity from the brain in the PET study, we performed MD simulations using a 3D MAGL structure and compound-A (Fig. 2). These MD simulations showed that the Cys242 of MAGL formed a hydrogen bond with the azetidine carbamate, but not with piperidine carbamate (Fig. 2C and F). Thus, we suggest that the difference in the interaction with MAGL between azetidine and piperidine carbamates is caused by structural differences in the carbon ring and the degree hydrophobicity. The formation of a hydrogen bond between azetidine carbamate and Cys242 could fix a spatial arrangement of the azetidine carbamate moiety that would be easily hydrolyzed by MAGL because of the increased accessibility of the water molecule. Further MD simulations suggested that complex-A would be structurally stable under weakly acidic conditions (pH 6) because the accessibility of the carbonyl moiety to water molecules would be hindered. MAGL is classified into the serine protease family, which structurally includes Ser122, His269 and Asp239 as the catalytic triad, three amino acids important for enzyme activity.29,30 Since in MD simulations the difference in the RMSD values on the main chain of complex-A between pH 7 and pH 6 was 1.9 Å, the main chain of the 3D structure of MAGL indicated no obvious structural changes at pH 6. However, under a weakly acidic condition such as pH 6, the His269 of the catalytic triad and other histidines in MAGL were protonated, resulting in formation of an ionic bond between His269 and Asp239 (Fig. 2H). We suggest that these reactions shifted the spatial arrangement of the side chain of His269 in MAGL, and that consequently, MAGL lost its function as a catalytic triad to trap the water molecule around the carbonyl moiety. Thus, the hydrolyzation of complex-A could depend on pH conditions, and therefore, estimation of the rate of hydrolysis of [11C]QST-0837 by MAGL could be used as an indicator of in vivo pHi.

As shown in Fig. 1A, we hypothesized that azetidine carbamate [11C]QST-0837 was bound to MAGL in the brain and hydrolyzed, resulting in production of 11CO2. Therefore, following successful 11C-labelling using 11COCl2 as a radiolabelled intermediate, we conducted in vitro 11CO2 collection assays using rat brain homogenate for [11C]QST-0837 and piperidine carbamate [11C]HPPC (as a comparator). In these assays, the radioactivity could be present in three compartments, which represent the unbound condition (unreacted), the complex and the production of 11CO2. As expected, radioactivity in the 11CO2 compartment was significantly detected with [11C]QST-0837, but not with [11C]HPPC. These results strongly support the modelled differences (in the MD simulations) in the structural resistance of compound-A and compound-P to hydrolysis by MAGL. Furthermore, for [11C]QST-0837, we investigated the change in 11CO2 production rate according to the change in pH. As predicted in the MD simulations, the production rate of 11CO2 decreased at lower pH values. Although highly acidic conditions (<pH 4.8) seemed to deactivate MAGL by denaturing it, the binding affinity of [11C]QST-0837 to MAGL and the 11CO2 production were maintained down to pH 5.7. It is known that the optimum pH for MAGL activity in the brain is in the range of 8–9,31 whereas the pHi is kept at around 7 in the healthy brain. Therefore, since the pH evoking half the maximal 11CO2 production was 5.3, this approach could be used to detect activity across a pH range of 5–7.

Prior to our work on the in vivo visualization of the pHi gradient using the disease model, we compared the brain kinetics of [11C]QST-0837 and [11C]HPPC using PET imaging in healthy rats (Fig. 4). [11C]QST-0837 containing an azetidine carbamate skeleton showed a moderate clearance of radioactivity after initial uptake, which was not seen with [11C]HPPC containing a piperidine carbamate skeleton. However, administration of JW642 (a potent covalent inhibitor of MAGL) after the injection of [11C]QST-0837 did not result in changes in radioactivity in the brain regions showing clearance, which strongly suggests that [11C]QST-0837 irreversibly bound to MAGL in vivo and that this was followed by production of 11CO2.

Based on the results of in vitro assays and PET studies using healthy rats, we proposed a compartment model for estimation of the hydrolysis rate (KH) of [11C]QST-0837 in vivo (Fig. 5A and B). Since the efflux rate of 11CO2 was much faster than the KH,16 the KH value of [11C]QST-0837 could be simply estimated using a mono-exponential fitting of the TAC. Here, because the plasma input function of [11C]QST-0837 was almost extinguished 15 min after the injection (Supplementary Fig. 7), exponential fitting on TAC from 15–90 min was permitted. Finally, to evaluate the feasibility of in vivo visualization of the pHi gradient based on the KH value, we conducted PET experiments with [11C]QST-0837 using MCAO rats as a disease model for acute acidic injury resulting from hypoxia (Fig. 5C–H). Several reports using MCAO rats showed that lactate concentrations continued to increase in the insult area until 3–4 h after occlusion.25,27 Another report using MCAO piglets showed that lactate levels in the insult area peaked within 2–6 h post-occlusion and then gradually decreased thereafter.32 We prepared MCAO rats with different occlusion periods (1, 3–4, or 6 h) and performed PET assessments. These showed that the KH value on the ipsilateral side of the brain in MCAO rat decreased, with a peak at 3–4 h of occlusion, which corresponded with the time course of the intracellular concentration of lactate, as described above. Moreover, although there was no correlation between KH values and regional differences of CBF in the brains of healthy rat (Supplementary Fig. 6G), the CBF in the ipsilateral brain area of a MCAO rat and immunofluorescence signals reflecting a severely hypoxic area on its brain sections showed strong correlation with the KH values (Fig. 5F–H). It is noted that the variation of KH value would become larger when maximum SUV was around 0.2 (Fig. 5G). Too much lower CBF (>0.2 SUV) would decrease sensitivity in radioactivity measurements using the PET scanner, although estimation of KH is theoretically independent from CBF.

In this study, we could not indicate a direct relationship between KH values and pHi in MCAO rats, since there was no way for simultaneous measurement with PET scan for pHi by combining other modalities, such as combination of 31P and 1H NMRs33 and amide proton transfer (APT)–MRI.34 However, lactic acidosis has long been associated with hypoxia in brain ischaemia and intracellular lactic accumulation induced by anaerobic glycolysis in severe hypoxic region has also been demonstrated by a number of efforts.35,36 Actually, the direct correlation between hypoxia level and pH had been reported under in vitro condition.37 Therefore, this study has successfully indicated the potential for in vivo monitoring of pHi in the brain using PET with [11C]QST-0837.

The MCAO model has also been used for APT–MRI, a known pH-weighted imaging technique26,27,32,38 that is widely used in clinical studies of hypoxia in cases of stroke and brain tumour.34,39,40 However, a significant correlation between APT signals and intracellular lactate levels has not been found.27,32 This might be because of technical issues with MRI, which make the technique suitable for morphological imaging but not for functional imaging. Therefore, our proposed PET imaging technique may present a superior alternative to the APT–MRI technique, which suffers from low sensitivity.

In addition to intracellular enzyme activity (as in the case of MAGL), the cytoskeletal component integration, cellular growth and differentiation rates are all highly affected by pHi. The common characteristics of different CNS diseases such as ischaemic stroke, traumatic brain injury, epilepsy, Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease are partly induced by decreases in associated enzymes, which show altered activity under acidic conditions.41 Furthermore, it is not only ischaemia and tumours that cause intracellular acidification, but also the aging process.3 Thus, in vivo monitoring of pHi using PET with [11C]QST-0837 could be a promising tool for developing new therapeutic approaches against multiple CNS disorders and for understanding the pathological mechanism of the aging process. However, some limitations remain, of which calibration of KH against in vivo pHi is essential. We are preparing further studies that will combine with MRI techniques for calibration of KH values in vivo.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of the QST for their support with the following: cyclotron operation, radioisotope production, radiosynthesis and animal experiments. We also thank Edanz (https://jp.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Tomoteru Yamasaki, Department of Advanced Nuclear Medicine Sciences, Institute for Quantum Medical Science, National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology, Chiba 263-8555, Japan.

Wakana Mori, Department of Advanced Nuclear Medicine Sciences, Institute for Quantum Medical Science, National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology, Chiba 263-8555, Japan.

Takayuki Ohkubo, Department of Advanced Nuclear Medicine Sciences, Institute for Quantum Medical Science, National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology, Chiba 263-8555, Japan; SHI Accelerator Service Co. Ltd., Tokyo 141-0031, Japan.

Atsuto Hiraishi, Department of Advanced Nuclear Medicine Sciences, Institute for Quantum Medical Science, National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology, Chiba 263-8555, Japan.

Yiding Zhang, Department of Advanced Nuclear Medicine Sciences, Institute for Quantum Medical Science, National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology, Chiba 263-8555, Japan.

Yusuke Kurihara, Department of Advanced Nuclear Medicine Sciences, Institute for Quantum Medical Science, National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology, Chiba 263-8555, Japan; SHI Accelerator Service Co. Ltd., Tokyo 141-0031, Japan.

Nobuki Nengaki, Department of Advanced Nuclear Medicine Sciences, Institute for Quantum Medical Science, National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology, Chiba 263-8555, Japan; SHI Accelerator Service Co. Ltd., Tokyo 141-0031, Japan.

Hideaki Tashima, Department of Advanced Nuclear Medicine Sciences, Institute for Quantum Medical Science, National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology, Chiba 263-8555, Japan.

Masayuki Fujinaga, Department of Advanced Nuclear Medicine Sciences, Institute for Quantum Medical Science, National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology, Chiba 263-8555, Japan.

Ming-Rong Zhang, Department of Advanced Nuclear Medicine Sciences, Institute for Quantum Medical Science, National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology, Chiba 263-8555, Japan.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Brain Communications online.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes for Quantum Science and Technology President’s Strategic Grant (exploratory research to T.Y.), Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (grants-in-aid for scientific research; grant no. 20H03635 to M.R.-Z.) and Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (grant no. 21zf0127003h001 to M.R.-Z.).

Competing interests

The authors report no competing interests.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

References

- 1. Freeman RS, Barone MC. Targeting hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) as a therapeutic strategy for CNS disorders. Curr Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord. 2005;4:85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhang X, Lin Y, Gillies RJ. Tumor pH and its measurement. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:1167–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bădescu GM, Fîlfan M, Ciobanu O, Dumbravă DA, Popa-Wagner A. Age-related hypoxia in CNS pathology. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2016;57:33–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baillieul S, Chacaroun S, Doutreleau S, Detante O, Pépin JL, Verges S. Hypoxic conditioning and the central nervous system: A new therapeutic opportunity for brain and spinal cord injuries? Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2017;242:1198–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bouzat P, Oddo M. Lactate and the injured brain: Friend or foe? Curr Opin Crit Care. 2014;20:133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Uria-Avellanal C, Robertson NJ. Na+/H+ exchangers and intracellular pH in perinatal brain injury. Transl Stroke Res. 2014;5:79–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chesler M. Failure and function of intracellular pH regulation in acute hypoxic-ischemic injury of astrocytes. Glia. 2005;50:398–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kearfott KJ, Junck L, Rottenberg DA. C-11 dimethyloxazolidinedione (DMO): Biodistribution, radiation absorbed dose, and potential for PET measurement of regional brain pH: Concise communication. J Nucl Med. 1983;24:805–811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Syrota A, Samson Y, Boullais C, et al. Tomographic mapping brain intracellular pH and extracellular water space in stroke patients. J Cereb Blood Flow and Metab. 1985;5:358–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vāvere AL, Biddlecombe GB, Spees WM, et al. A novel technology for the imaging of acidic prostate tumors by positron emission tomography. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4510–4516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Butler CR, Beck EM, Harris A, et al. Azetidine and piperidine carbamates as efficient, covalent inhibitors of monoacylglycerol lipase. J Med Chem. 2017;60:9860–9873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cheng R, Mori W, Ma L, et al. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of 11C-labeled azetidinecarboxylates for imaging monoacylglycerol lipase by PET imaging studies. J Med Chem. 2018;61:2278–2291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen Z, Mori M, Deng X, et al. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of reversible and irreversible monoacylglycerol lipase positron emission tomography (PET) tracers using a “tail switching” strategy on a piperazinyl azetidine skeleton. J Med Chem. 2019;62:3336–3353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mori W, Hatori A, Zhang Y, et al. Radiosynthesis and evaluation of a novel monoacylglycerol lipase radiotracer: 1,1,1,3,3,3-Hexafluoropropan-2-yl-3-(1-benzyl-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)azetidine-1-[11C]carboxylate. Bioorg Med Chem. 2019;27:3568–3573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tuo W, Leleu-Chavain N, Spencer J, Sansook S, Millet R, Chavatte P. Therapeutic potential of fatty acid amide hydrolase, monoacylglycerol lipase, and N-acylethanolamine acid amidase inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2017;60:4–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brooks DJ, Lammertsma AA, Beaney RP, et al. Measurement of regional cerebral pH in human subjects using continuous inhalation of 11CO2 and positron emission tomography. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1984;4:458–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Di Marzo V, Stella N, Zimmer A. Endocannabinoid signalling and the deteriorating brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16:30–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Viader A, Blankman JL, Zhong P, et al. Metabolic interplay between astrocytes and neurons regulates endocannabinoid action. Cell Rep. 2015;12:798–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang L, Mori W, Cheng R, et al. Synthesis and preclinical evaluation of sulfonamido-based [11C-carbonyl]-carbamates and ureas for imaging monoacylglycerol lipase. Theranostics. 2016;6:1145–1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Barzagli F, Mani F, Peruzzini M. A comparative study of the CO2 absorption in some solvent-free alkanolamines and in aqueous monoethanolamine (MEA). Environ Sci Technol. 2016;50:7239–7246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Koizumi J, Yoshida Y, Nakazawa T, Ooneda G. Experimental studies of ischemic brain edema, I: A new experimental model of cerebral embolism in rats in which recirculation can be introduced in the ischemic area. Jpn J Stroke. 1986;8:8. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Keyes JW Jr. SUV: Standard uptake or silly useless value? J Nucl Med. 1995;36:1836–1839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang L, Ren C, Li Y, et al. Remote ischemic conditioning enhances oxygen supply to ischemic brain tissue in a mouse model of stroke: Role of elevated 2,3-biphosphoglycerate in erythrocytes. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2021;41:1277–1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Okamura T, Kikuchi T, Okada M, et al. Noninvasive and quantitative assessment of the function of multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 in the living brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:504–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hillered L, Hallström A, Segersvärd S, Persson L, Ungerstedt U. Dynamics of extracellular metabolites in the striatum after middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat monitored by intracerebral microdialysis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1989;9:607–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jokivarsi KT, Hiltunen Y, Tuunanen PI, Kauppinen RA, Gröhn OH. Correlating tissue outcome with quantitative multiparametric MRI of acute cerebral ischemia in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:415–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Park JE, Jung SC, Kim HS, et al. Amide proton transfer-weighted MRI can detect tissue acidosis and monitor recovery in a transient middle cerebral artery occlusion model compared with a permanent occlusion model in rats. Eur Radiol. 2019;29:4096–4104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tsuchidate R, He QP, Smith ML, Siesjö BK. Regional cerebral blood flow during and after 2 hours of middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1997;17:1066–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tornqvist H, Belfrage P. Purification and some properties of a monoacylglycerol hydrolyzing enzyme of rat adipose tissue. J Biol Chem. 1976;251:813–819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Karlsson M, Contreras JA, Hellman U, Tornqvist H, Holm C. cDNA cloning, tissue distribution, and identification of the catalytic triad of monoglyceride lipase. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:27218–27223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zheng Y, Wang XM. Measurement of lactate content and amide proton transfer values in the basal ganglia of a neonatal piglet hypoxic-ischemic brain injury model using MRI. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2017;38:827–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Evagorou A, Anagnostopoulos D, Farmaki E, Siafaka-Kapadai A. Hydrolysis of 2-arachidonoylglycerol in tetrahymena thermophila. Identification and partial characterization of a monoacylglycerol lipase-like enzyme. Eur J Protistol. 2010;46:289–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Crockard HA, Gadian DG, Frackowiak RSJ, et al. Acute cerebral ischaemia: Concurrent changes in cerebral blood flow, energy metabolites, pH, and lactate measured with hydrogen clearance and 31P and 1H nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. II. Changes during ischaemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1987;7:394–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhou J, Heo HY, Knutsson L, van Zijl PCM, Jiang S. APT-weighted MRI: Techniques, current neuro applications, and challenging issues. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2019;50:347–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rehncrona S. Brain acidosis. Ann Emerg Med. 1985;14:770–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Levine RL. Ischemia: From acidosis to oxidation. FASEB J. 1993;7:1242–1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Arocena M, Landeira M, Di Paolo A, et al. Using a variant of coverslip hypoxia to visualize tumor cell alterations at increasing distances from an oxygen source. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:16671–16678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jokivarsi KT, Gröhn HI, Gröhn OH, Kauppinen RA. Proton transfer ratio, lactate, and intracellular pH in acute cerebral ischemia. Magn Reason Med. 2007;57:647–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wang E, Wu Y, Cheung JS, et al. Mapping tissue pH in an experimental model of acute stroke—Determination of graded regional tissue pH changes with non-invasive quantitative amide proton transfer MRI. Neuroimage. 2019;191:610–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kamimura K, Nakajo M, Yoneyama T, et al. Amide proton transfer imaging of tumors: Theory, clinical applications, pitfalls, and future directions. Jpn J Radiol. 2019;37:109–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fang B, Wang D, Huang M, Yu G, Li H. Hypothesis on the relationship between the change in intracellular pH and incidence of sporadic Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia. Int J Neurosci. 2010;120:591–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.