Abstract

The Gag‐Pol polyprotein in human immunodeficiency virus type I (HIV‐1) encodes enzymes that are essential for virus replication: protease (PR), reverse transcriptase (RT), and integrase (IN). The mature forms of PR, RT and IN are homodimer, heterodimer and tetramer, respectively. The precise mechanism underlying the formation of dimer or tetramer is not yet understood. Here, to gain insight into the dimerization of PR and RT in the precursor, we prepared a model precursor, PR‐RT, incorporating an inactivating mutation at the PR active site, D25A, and including two residues in the p6* region, fused to a SUMO‐tag, at the N‐terminus of the PR region. We also prepared two mutants of PR‐RT containing a dimer dissociation mutation either in the PR region, PR(T26A)‐RT, or in the RT region, PR‐RT(W401A). Size exclusion chromatography showed both monomer and dimer fractions in PR‐RT and PR(T26A)‐RT, but only monomer in PR‐RT(W401A). SEC experiments of PR‐RT in the presence of protease inhibitor, darunavir, significantly enhanced the dimerization. Additionally, SEC results suggest an estimated PR‐RT dimer dissociation constant that is higher than that of the mature RT heterodimer, p66/p51, but slightly lower than the premature RT homodimer, p66/p66. Reverse transcriptase assays and RT maturation assays were performed as tools to assess the effects of the PR dimer‐interface on these functions. Our results consistently indicate that the RT dimer‐interface plays a crucial role in the dimerization in PR‐RT, whereas the PR dimer‐interface has a lesser role.

Keywords: darunavir, dimerization, Gag‐Pol polyprotein, HIV‐1, inhibitor, protease, reverse transcriptase

1. INTRODUCTION

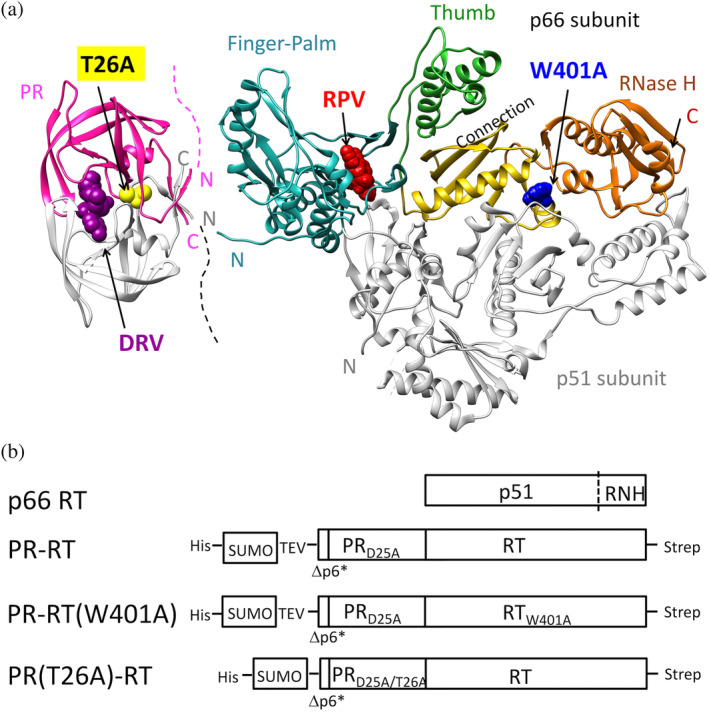

The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV‐1) encodes Gag‐Pol polyprotein that contains proteins essential for virus infectivity, including the critical enzymes protease (PR), reverse transcriptase (RT) and integrase (IN) (Coffin et al., 1997; Darke et al., 1988; Jacks et al., 1988). PR cleaves Gag‐Pol to release itself and the other proteins from the polyprotein (Hill et al., 2005; Navia et al., 1989; Oroszlan & Luftig, 1990; Pettit et al., 2003; Wlodawer & Erickson, 1993). Structural data have elucidated the mature forms of the enzymes, which are dimers for PR and RT (Figure 1a) and tetramer for IN (Davies II et al., 1991; Dyda et al., 1994; Jacobo‐Molina et al., 1993; Kohlstaedt et al., 1992; Miller et al., 1989; Navia et al., 1989; Smerdon et al., 1994). Thus, multiple conformational changes in these proteins are necessary to yield the mature viral enzymes from the precursor. Among these enzymes, PR dimerization, which installs catalytic activity, directly contributes to the maturation of the other proteins in Gag‐Pol (Darke et al., 1988).

FIGURE 1.

(a) Known structures of the mature PR homodimer and RT p66/p51, and (b) schematic representation of p66 RT and model precursors prepared in this study. (a) PR‐RT mutation sites, T26A in PR and W401A in RT, and the locations of the PR inhibitor darunavir (DRV) and of the RT inhibitor rilpivirine (RPV), each known to enhance dimerization of the mature enzymes, respectively, are indicated. Structures were generated using PDB 1T3R and 4G1Q (Kuroda et al., 2013; Surleraux et al., 2005). Only one subunit of PR and the p66 subunit of RT are colored: PR, pink; Finger‐Palm subdomain, cyan; Thumb subdomain, green; Connection subdomain, yellow; RNH domain, orange. How PR and RT fold in PR‐RT is unknown. The N‐ and C‐termini of PR and RT are indicated by N and C, respectively, using the same colors as those of the backbones. (b) Δp6* indicates two residues preceding PR, Asn‐Phe, and these proteins are fused to a hexa‐histidine tag and SUMO domain. Details of the amino acid sequences are described in the Section 5.

These mature enzymes are known to be rigidly folded (Figure 1a). The matured HIV‐1 PR forms a homodimer with the active site residue D25 at the dimer interface (Lapatto et al., 1989; Navia et al., 1989; Wlodawer et al., 1989). In the dimer structure, NH of the proline residue at the N‐terminus, P1, in one subunit forms a hydrogen bond with the backbone carbonic acid at the C‐terminus, F99’, in the other subunit (Figure S1). This proline residue is well conserved in HIV‐1 PR (Rhee et al., 2003). Importantly, previous structural studies of the mature PR have shown that even a few N‐terminal p6* residues appended to PR destabilize the PR dimer (Agniswamy et al., 2012; Ishima et al., 2007; Louis et al., 1994; Louis et al., 1999), presumably by disturbing the hydrogen bond network between the N‐terminal β‐strand in one subunit and the C‐terminal β‐strand in the other subunit, including the P1‐F99’ hydogen bond. In contrast to these notions for the mature PR, whether/how the flanking sequence at the C‐terminal end of PR, that is, RT N‐terminal sequence, affects PR dimerization, or how PR dimerization affects RT dimerization is not fully understood. The mature RT heterodimer consists of 66 kDa (p66) and 51 kDa (p51) subunits, the latter produced by proteolytic cleavage of the ribonuclease H (RNH) domain from p66 by HIV‐1 PR (Chattopadhyay et al., 1992; Divita et al., 1995; Sharma et al., 1994). We have also shown that RT p66 homodimer, p66/p66, forms a symmetric structure in solution on a time scale detected by NMR, and its binding to Lys3 tRNA introduces a conformational asymmetry in the two p66/p66 subunits and enhances specific proteolysis of one of the two RNH domains to generate p66/p51 (Ilina et al., 2018; Slack et al., 2019).

In contrast to the wealth of information that has been obtained over the years for the mature enzyme structures, structural information of the precursors is scarce. The PR‐RT crystal structure of the Prototype Foamy Virus (PFV) was solved at 2.9 Å resolution and exhibited a monomer PR‐RT form (Harrison et al., 2021). This observation of a monomer is reasonable because, unlike HIV‐1 PR, dimerization of the matured PFV PR is weak and is activated by interaction with RNA in the PR‐RT form (Hartl et al., 2010; Hartl et al., 2011). In the case of HIV, a cryo‐EM structure of HIV‐1 Pol was reported at 3.8 Å, but only the RT region was well‐resolved with a weaker density for the PR dimer and no explicit density for the main body of the IN region (Harrison et al., 2022). In this structure, the RT region forms an asymmetric dimer similar to that of the mature RT, suggesting that RT dimerization might contribute to PR dimerization in the Pol precursor (Harrison et al., 2022). Regarding Pol activity, it is known that PR‐RT that contains a mutation to prevent the cleavage between the PR and RT regions is functional in the virus (Cherry et al., 1998); however, it is unknown whether the PR in PR‐RT exists in a dimer form in the absence of substrate.

Our immediate goal is to understand dimerization of the HIV‐1 Gag‐Pol polyprotein, with a focus on the PR‐RT region. Given that both PR and RT proteins typically form dimers in solution, it may be naturally anticipated that PR‐RT would exhibit a dimer form. However, if PR strongly dimerizes in the Gag‐Pol polyprotein, PR may become active in the cytosol and cleave the polyprotein before delivering it to the budding virus. Indeed, nonnucleoside RT inhibitors (NNRTIs) that enhance RT dimerization are known to induce unregulated PR activation, resulting in reduced HIV‐1 production from latently infected resting CD4+ T cells (Jochmans et al., 2010; Trinite et al., 2019; Zerbato et al., 2017). Thus, characterization of the PR region in Gag‐Pol, particularly its dimerization, is important to gain insight into Pol enzyme maturation during progression of the HIV‐1 life cycle.

In this study, we aimed to understand the dimerization interface in PR‐RT biochemically, using model precursor proteins. We prepared a model PR‐RT precursor that (a) contains an inactivating mutation, D25A, to prevent autoproteolysis, (b) includes two residues at the N‐terminus to mimic the PR region in the Gag‐Pol protein and to resemble PR in Pol, and (c) is fused to a SUMO‐tag at the N‐terminus. Because even a few N‐terminal p6* residues appended to PR destabilize the PR dimer (Agniswamy et al., 2012; Ishima et al., 2007; Louis et al., 1994; Louis et al., 1999), we believe that the tagged‐PR‐RT protein serves as a model PR‐RT. In addition, two variants of PR‐RT were prepared, one with a mutation in the PR region, PR(T26A)‐RT, and a second with a mutation in the RT region, PR‐RT(W401A) (Figure 1b, numbering per mature protein sequence). Both T26A in PR and W401A in RT are known as dimer dissociation mutations of the matured enzymes, that is, PR homodimer and RT heterodimer (Ishima et al., 2007; Tachedjian et al., 2003). Using these proteins, we carried out size exclusion chromatography (SEC) and polymerase assays both in the absence and presence of darunavir (DRV), which is known to increase dimer formation of the mature PR (Louis et al., 2009; Louis et al., 2013). SEC experiments were also performed in the presence of a non‐nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI), rilpivirine (RPV), that is known to enhance dimerization of RT homodimer as well as the heterodimer (Sharaf et al., 2017; Slack et al., 2019; Tachedjian et al., 2005). We also examined RT maturation, specifically production of p66/p51 by active PR, to further characterize the influence of the PR region on RT conformation in PR‐RT. Based on the results obtained from these studies, we conclude that the RT dimer interface plays a crucial role for the dimerization of PR‐RT while the PR region is less significantly dimerized in PR‐RT in solution.

2. RESULTS

2.1. Purification of PR‐RT and the mutants

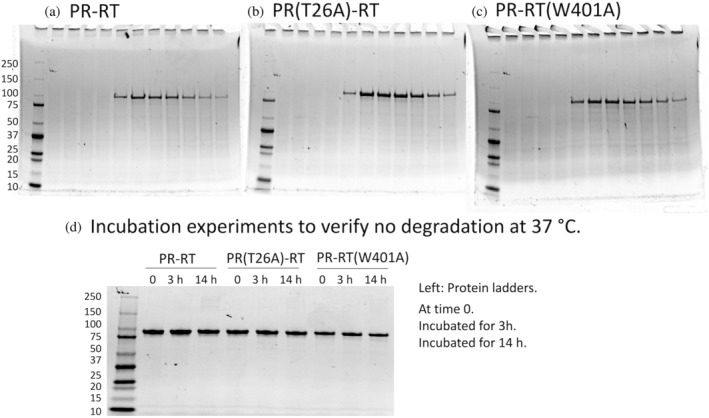

PR‐RT, PR(T26A)‐RT, and PR‐RT(W401A) (Figure 1b) were expressed with an N‐terminal SUMO tag to gain solubility and stability for the in vitro experiments. It is known that p66 encoded in E. coli can generate p66/p51 by E. coli protease proteolysis (Bavand et al., 1993; Clark Jr. et al., 1995; Lowe et al., 1988), and small contamination of the mature p66/p51 RT could interfere with our assays and confound data interpretation. Conflicting results have been published for RT precursor structures (Schmidt et al., 2019; Sharaf et al., 2014; Zheng et al., 2014). Thus, it is important to clearly describe the purity of PR‐RT used in our study. The eluted proteins showed one clear band in the sodium dodecyl‐sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS‐PAGE) (Figure 2a–c), with final UV260/280 ratios at <0.57 (Table S1). Molecular mass, determined by mass spectrometry, matched the theoretical values (Table S1). Incubation of the purified proteins with dsDNA at 37°C for 14 h confirmed the absence of significant E. coli protease contamination (Figure 2d, see Section 5).

FIGURE 2.

SDS‐PAGE of (a) PR‐RT, (b) PR(T26A)‐RT, (c) PR‐RT(W401A), each following the final heparin column elution, and (d) each protein following incubation at the indicated temperatures to confirm the absence of significant E. coli protease contamination. In the experiments in (d), proteins (8 μM, calculated as monomer) were incubated in the presence of 2 μM dsDNA for 0, 3, and 14 h at 37°C. If serine protease contamination was present, the dsDNA would enhance protease digestion at the RT site (see the Section 5 for RT maturation).

To establish an optimal buffer condition for PR‐RT, PR(T26A)‐RT and PR‐RT(W401A), dynamic light scattering (DLS) was performed with the purified proteins in buffers of varying salt and glycerol concentrations (Figure S2). In particular, since we planned to run various SEC experiments, we sought conditions that minimized aggregation to <5 MDa, to avoid an increase in column pressure. Our DLS data clearly showed such a condition for all three proteins at higher NaCl concentration, such as 300 mM, compared to the condition without NaCl (Figure S2). In addition, higher glycerol concentrations (>5%) tended to reduce aggregation in PR‐RT and PR(T26A)‐RT samples (Figure S2). A glycerol effect was not explicit for PR‐RT(W401A) (see the Section 3). Based on these results, we decided to use a 25 mM HEPES buffer containing 250 mM NaCl and 2%–10% glycerol at pH 7.5, for our SEC and SEC‐MALS experiments.

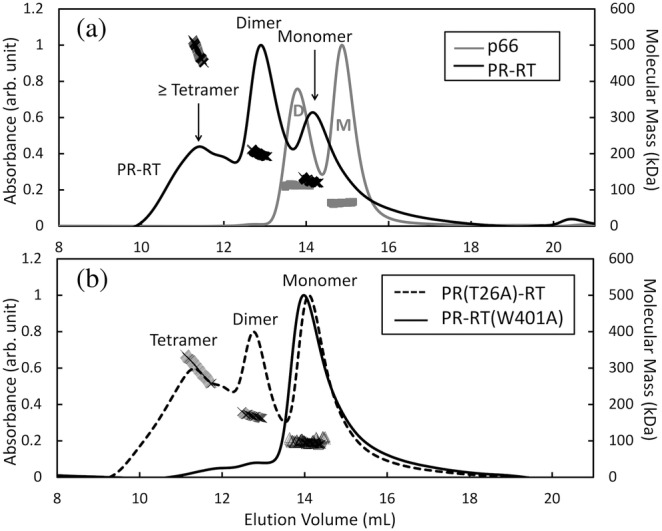

2.2. Identification of monomer and dimer species of PR‐RT and the mutants by SEC‐MALS

SEC‐MALS experiments were performed for p66, PR‐RT, PR(T26A)‐RT and PR‐RT(W401A) (Figure 3 and Table 1). Since the instrument is sensitive to the refractive index of the sample solution, we conducted SEC‐MALS experiments using a buffer containing 2% glycerol, rather than 10% glycerol, but with a pre‐filter to prevent elution of large molecular particles. Thus, the SEC‐MALS data were used only to identify the eluted species but not to quantitatively evaluate the total elution volumes or a molar ratio of the eluted species (see the SEC result section below).

FIGURE 3.

Normalized SEC‐MALS profiles to identify monomer, dimer and oligomer states of (a) p66 (gray line) and PR‐RT (black line), and those of (b) PR(T26A)‐RT (dashed line) and PR‐RT(W401A) (black line). Symbols in the graph indicate the observed molecular mass (the right vertical axis): p66 (gray squares), PR‐RT (black cross marks), PR(T26A)‐RT (thin cross marks), and PR‐RT(W401A) (gray triangles). Proteins at 8 μM concentration (calculated as a monomer) were injected into a Superdex Increase 200 10/300 GL column, with a pre‐filter, equilibrated with a 25 mM HEPES buffer containing 2% glycerol, 250 mM NaCl, and 1 mM DTT at pH 7.5.

TABLE 1.

Molecular masses estimated from SEC‐MALS.

| Protein | Molar mass | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical monomer (kDa) | SEC‐MALS mass (kDa) | |||

| Monomer | Dimer | Tetramer or larger | ||

| p66 | 66.1 | 63.8 ± 5 | 113.4 ± 3.7 | n.d. |

| PR‐RT | 89.7 | 124.6 ± 3 | 199.2 ± 2 | 514.6 ± 1.8 |

| PR(T26A)‐RT | 89.7 | 95.2 ± 1.5 | 169.1 ± 1.6 | 334.9 ± 1.4 |

| PR‐RT(W401A) | 89.6 | 99.0 ± 6 | n.d. | n.d. |

SEC‐MALS data of p66, as a control, indicated dimer and monomer fractions eluting at 13.8 and 14.9 ml, respectively (Figure 3a, gray line). The molar masses of these species obtained from MALS were 113.4 ± 3.7 and 63.8 ± 5 kDa, respectively, which are close to the theoretical values of the dimer and monomer, 133 and 66 kDa, respectively (Table 1). These obtained mass values are essentially the same as those reported previously (Sharaf et al, 2014; Ilina et al., 2020). The elution profile of the PR‐RT exhibited three elution peaks at ~11.3, 12.4 and 14.1 ml with molar masses of 514.6 ± 1.8, 199.2 ± 2, and 124.6 ± 3 kDa, respectively (Figure 3a and Table 1). These masses were close to the theoretical values of tetramer, dimer and monomer, 359, 179, and 89.7 kDa, respectively. The elution at ~11.3 ml could be a mixture of oligomer states, that is, with species larger than tetramer. For the dimer and monomer fractions, since the eluted peaks showed a slight overlap with each other, the mass of the dimer peak was slightly smaller than the theoretical value while that of the monomer was slightly larger.

The elution profile of PR(T26A)‐RT also exhibited tetramer, dimer and monomer fractions with estimated molar masses of 334.9 ± 1.4, 169.1 ± 1.6, and 95.2 ± 1.5 kDa, respectively (Figure 3b and Table 1), similar to those of PR‐RT. Different from PR‐RT and PR(T26A)‐RT, the elution profile of PR‐RT(W401A) indicated only monomer with a molar mass of 99.0 ± 6 kDa (Figure 3b and Table 1). Experiments were repeated at a second protein concentration to verify the elution profiles (Figure S3). Collectively, based on the SEC‐MALS, monomer and dimer elution peaks in PR‐RT and the mutants were identified.

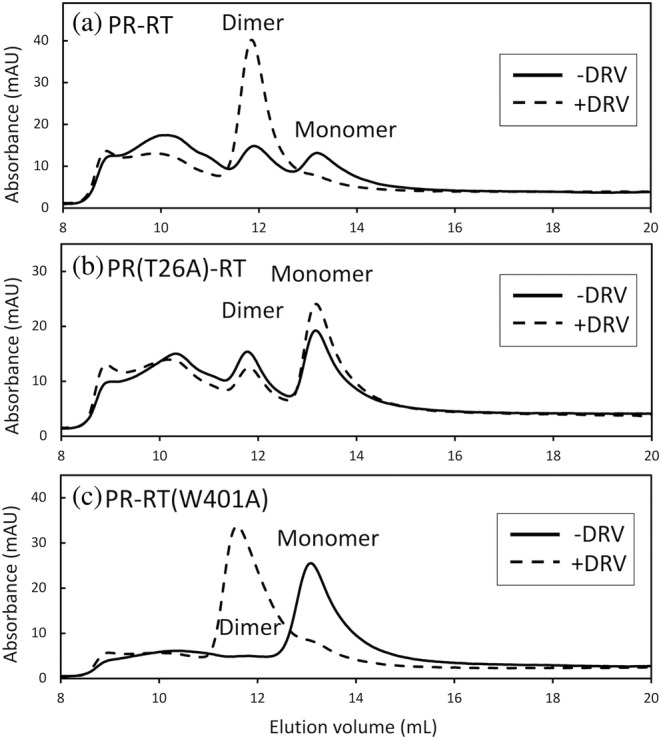

2.3. W401 is more critical for PR‐RT dimerization than T26

Since the SEC‐MALS experiments were performed with a prefilter, it was not certain how much of the injected protein was actually recovered. Thus, to evaluate the degree of elution of each injected protein, SEC experiments were performed without a prefilter and in a buffer with 10% glycerol. SEC profiles of PR‐RT, PR(T26A)‐RT and PR‐RT(W401A) at 8 μM protein concentration (as a monomer) in the absence of DRV (Figure 4, solid line) showed essentially the same elution patterns as those observed with SEC‐MALS (Figure 3), except for elutions spanning a wider retention volume after the void volume in PR‐RT and PR(T26A)‐RT. This amplification of large molecular mass in SEC was reasonable because the pre‐filter was not attached in this SEC experiment.

FIGURE 4.

SEC profiles of (a) PR‐RT, (b) PR(T26A)‐RT, and (c) PR‐RT(W401A) in the presence (dashed line) and absence (solid line) of DRV. Proteins at 8 μM protein concentration (calculated as a monomer) were injected into a Superdex Increase 200 10/300 GL column, equilibrated with a 25 mM HEPES buffer containing 10% glycerol, 250 mM NaCl and 1 mM DTT at pH 7.5. Note, due to differences in the instruments, including the presence or absence of a prefilter, and in the glycerol concentration, the elution positions differ slightly from those observed in SEC‐MALS.

In brief, PR‐RT showed three distinct fractions at retention volumes of ~9.9, 11.9, and 13.1 ml (Figure 4a, solid line) which correspond to the oligomers observed in SEC MALS, with sizes of “tetramer or greater”, dimer and monomer, respectively (Figure 3a). In particular, the relative position of the PR‐RT monomer (89.7 kDa) compared to p66 dimer (133 kDa) (Figure S4) confirms the PR‐RT monomer peak position in SEC. A similar profile was observed for PR(T26A)‐RT, but with an amplified intensity for the monomer peak at 13.1 ml (Figure 4b, solid line). The SEC profile of PR‐RT(W401A) showed only a monomer elution peak (Figure 4c, solid line). Experiments were repeated at different protein concentrations to verify the elution peak positions (Figure S4, see details in the figure caption).

To verify that a majority of the injected protein was in fact eluted, total elution volumes, from 8.5 to 17 ml, in the SEC elution profiles of PR‐RT, PR(T26A)‐RT, and PR‐RT(W401A) were calculated and compared with that of p66 (Table 2). By normalizing protein concentrations and the extinction coefficients of the proteins, we conclude that 98%, 93%, and 88% of the injected proteins were eluted for PR‐RT, PR(T26A)‐RT and PR‐RT(W401A), respectively (Table 2). Although 8 μM protein was applied to the SEC column, the proteins are empirically diluted by 10‐fold in these columns (Sharaf et al., 2017). Thus, the degree of aggregation may be lower compared to that observed by DLS. Our results confirmed that most fractions of each injected protein were eluted in our SEC condition.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of the total elution volumes of the SEC data to verify that most of the injected protein was eluted.

| Protein | Integrated area in SEC (8.5–17 ml) | Relative integrated SEC | Relative extinction coefficient (M−1 cm−1) a | Eluted fraction (%) b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p663 | 3106.9 | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| PR‐RT WT | 3468.47 | 1.12 | 1.14 | ~98. |

| PR(T26A)‐RT | 3289.43 | 1.06 | 1.14 | ~93. |

| PR‐RT(W401A) | 3015.42 | 0.97 | 1.10 | ~88. |

Molar concentration was calculated by assuming monomer.

Since this is a qualitative estimation of the overall elution, uncertainty is not added here. Empirically, we estimate a protein handling uncertainty of ~5%.

Taken together, both the SEC‐MALS and SEC data indicate that the dimer interface of the RT region, disrupted by the W401A mutation, is critical for PR‐RT dimerization. In contrast, the PR dimer interface is not as essential for PR‐RT dimerization when compared to the RT interface, considering that the SEC profiles of PR‐RT and PR(T26A)‐RT qualitatively show no substantial differences. Given that the dimer interface of PR spans ~28 Å, which is less than a half of the mature RT dimer interface (Figure 1a), the observed impact of the RT interface in PR‐RT dimerization may be reasonable.

2.4. DRV promotes dimerization of PR‐RT and PR‐RT(W401) but increases PR‐RT(T26A) dimerization to a lesser extent

To test whether the PR region is involved in PR‐RT dimerization, the SEC experiments were performed with DRV added to the PR‐RT proteins at a protein dimer:DRV ratio of 1:2. Indeed, in the presence of DRV, the magnitude of the dimer peak at 11.9 ml in PR‐RT significantly increased while that of the monomer at 13.1 ml decreased (Figure 4a, dashed line). Note, DRV itself has a UV absorbance (Bhavyasri & Sumakanth, 2020), therefore the relative UV intensity ratio of the monomer and dimer elution peaks does not reflect the monomer‐dimer ratio of the protein. A similar effect was observed for PR‐RT(W401A), showing a remarkable dimer elution in the presence of DRV (Figure 4c, dashed line), compared to the absence of DRV (Figure 4c, solid line). In contrast, DRV did not significantly change the elution profile of PR(T26A)‐RT (Figure 4b, dashed line). Based on the expected protein concentration in the column and neglecting the flow effect (i.e., 10‐fold dilution), if DRV is able to bind PR(T26A)‐RT, the DRV dissociation constant is high, estimated to be more than 20 μM. This observation is consistent with previous results of the mature PR: the melting temperature, T m , of the T26A mutant of the mature PR, that is monomer, is lower compared to PR dimer, and DRV only slightly increases the T m (Louis et al., 2013).

Similar SEC experiments were repeated in the presence of RPV, a NNRTI that is known to enhance RT dimer formation. Similar to our results obtained in the presence of DRV, the monomer fraction vanished from the elution profiles in the presence of RPV (Figure S5). However, the total elution volume was reduced. Knowing that RPV enhances dimerization of the RT homodimer, p66/p66 (Sharaf et al., 2017; Slack et al., 2019; Tachedjian et al., 2005), we expect that RPV binds PR‐RT dimer, and the complex form undergoes oligomerization or aggregation. In either case, the stark contrast between the SEC profiles obtained in the absence of DRV or RPV and those obtained in the presence of these agents indicates that dimerization of PR‐RT in the absence of these aids is not strong.

2.5. PR dimerization is not critical for reverse transcriptase activity of PR‐RT

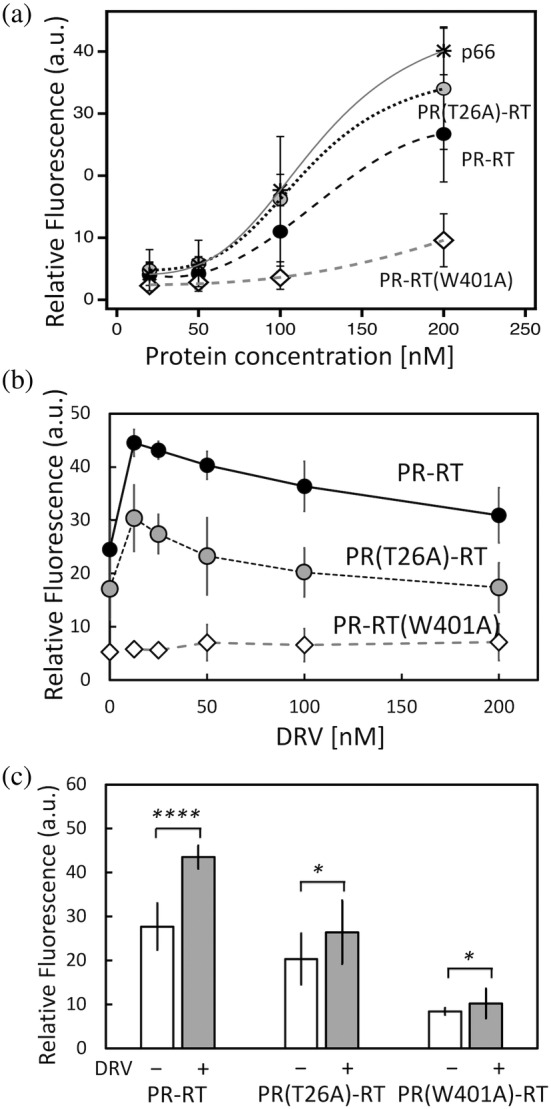

Since reverse transcription in HIV‐1 occurs after cell entry when RT is a mature heterodimer (Hu & Hughes, 2012; Hulme et al., 2011; Whitcomb et al., 1990; Yang et al., 2013), a reverse transcriptase assay using the immature PR‐RT form does not reflect a natural phenomenon in normal viral replication. However, here, we used the reverse transcriptase assay of PR‐RT in the presence and absence of DRV as a tool to investigate the effect of PR dimerization on the RT region of the PR‐RT model. First, the dependence of reverse transcriptase activity on protein concentration was measured for PR‐RT and each of the mutants (Figure 5a). Essentially, PR‐RT and PR(T26A)‐RT presented similar activity levels, while PR‐RT(W401A) exhibited reduced activity (Figure S6a–d). The activities of PR‐RT and PR(T26A)‐RT varied more among the repeats when compared to p66 (Figure S6a–d), as reflected by the standard deviation for the combined experimental data (Figure 5a). The W401A mutant of mature RT is known to be defective for dimerization and therefore lacks the activity (Tachedjian et al., 2003). Thus, our experimental data show that the W401A effect in PR‐RT is similar to that of the mature RT.

FIGURE 5.

Reverse transcription assay of PR‐RT, PR(T26A)‐RT, and PR‐RT(W401A): (a) protein concentration dependence, (b) DRV concentration dependence and (c) quantification at 50 nM DRV. In (a), the indicated protein concentrations are dimer concentration, since dimer is the functional form of RT. p66 was included as a control. Data from independent experiments that were used to generate the summary data in panel (a) are shown in Figure S5a–d. Data are shown as the average of the four experiments with the standard deviation as uncertainty. In (c), statistical significance of differences between ±DRV groups was evaluated from p values of the student's t‐tests: *0.01 < p < 0.05; ****p < 0.0001.

Second, similar experiments were conducted with DRV present at varying concentrations (Figure 5b). These experiments were performed at 200 nM protein concentration (calculated as dimer because the dimer is needed for its function) and with 4% and 0.8% DMSO in the intermediate and final reaction mixtures, respectively. DMSO alone had no effect on the reverse transcriptase activities of PR‐RT and the mutants (Figure S6e). The DMSO concentration was kept constant throughout the DRV experiments, that is, it was also present even at zero DRV concentration in this series of experiments.

In both PR‐RT and PR(T26A)‐RT data, a small amount of DRV, that is, less than 25 nM, significantly increased reverse transcriptase activity (Figure 5b and S7). The DRV‐dependent increase in the activity of PR‐RT was greater than that of PR(T26A)‐RT (Figure 5c). This is consistent with our SEC data, that is, DRV binds PR‐RT dimer better than PR(T26A)‐RT (Figure 4). However, as DRV concentration increased above 25 nM, the positive effect on reverse transcriptase activity became less, and at the highest concentration tested (200 nM), DRV had little to no effect (Figures 5b and S7). Although DRV has been proposed to dissociate the PR dimer in a cellular environment (Hayashi et al., 2014), we did not observe DRV‐induced dimer dissociation in our SEC experiments where 8 μM protein was injected (i.e., as a dimer and diluted 10‐fold in the column, resulting in ~400 nM, a concentration similar to that used for these reverse transcriptase assays). Since our SEC data show that DRV binds PR‐RT, one possible explanation for the reduced effect of higher DRV concentrations is that stable DRV binding rigidifies the relative orientation of the N‐terminal region of RT and negatively impacts dynamic RT function. Taken together, these reverse transcriptase assay results, in the absence and presence of DRV and between PR‐RT and PR(T26A)‐RT, indicate that stable dimer formation of the PR region in PR‐RT may not be needed for the polymerase function in RT.

2.6. T26A does not alter RT maturation of PR‐RT

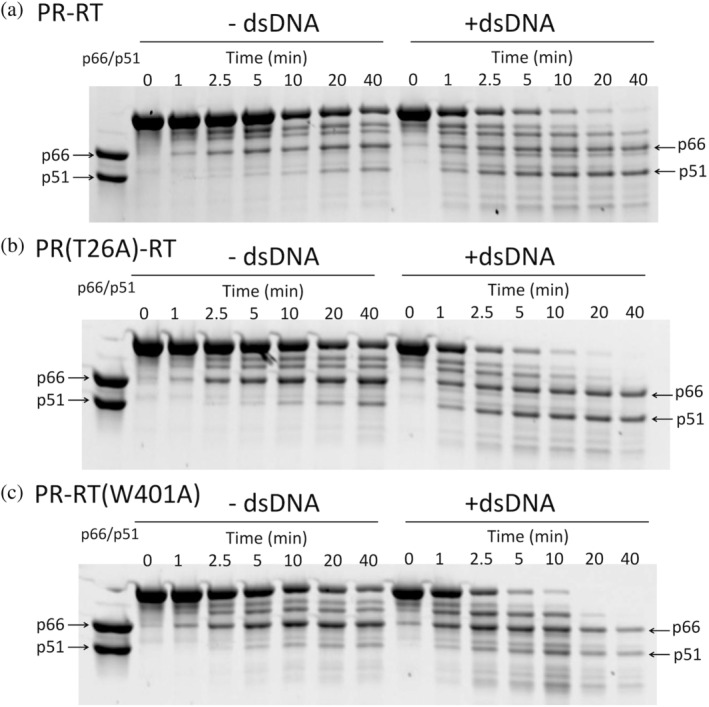

Processing of PR‐RT, PR(T26A)‐RT and PR‐RT(W401A) by active protease (Ilina et al., 2018, 2020; Slack et al., 2019) was monitored by SDS‐PAGE gel to assess how the presence of PR at the N‐terminus of RT affects RT maturation (Figures 6 and S8–S11). We particularly evaluated production of p66 and p51, which are the bands that are seen separately from other products in the gel. Although the N‐terminal processing of PR is self‐catalyzed as an intra‐molecular reaction, the C‐terminal end of PR is processed as an inter‐molecular reaction (Louis et al., 1994; Wondrak et al., 1996). Thus, use of active PR to investigate RT maturation in PR‐RT is valid. Experiments were performed in the absence and presence of 30 nt/32 nt dsDNA that is known to introduce conformational changes in the RT region, similar to dsRNA or RNA/DNA and, thus, is utilized as a tool to alter RT maturation.

FIGURE 6.

Processing of PR‐RT, PR(T26A)‐RT, and PR‐RT(W401A) by active HIV‐1 PR in the presence or absence of dsDNA: (a) PR‐RT, (b) PR(T26A)‐RT, and (c) PR‐RT(W401A). Processing of PR‐RT proteins at 4 μM protein concentration (calculated as a dimer) was performed by adding 1 μM PR (calculated as a dimer) with/without 4 μM dsDNA at pH 5.0. The entirety of these gels is shown in Figure S9. Data reproducibility was confirmed (Figure S10). A version with molecular markers is shown in Figure S11.

RT maturation of PR‐RT in the presence or absence of dsDNA (Figure 6a) was similar to that observed previously in our study of p66 maturation (Ilina et al., 2018). In brief, the reduction of intact PR‐RT (p90) occurs more quickly in the presence of dsDNA than in the absence of dsDNA. In addition, production of p51 at a level similar to p66, that is, p66/p51 RT formation, was also observed in the presence of dsDNA, whereas in the absence of dsDNA, production of p51 was relatively less than p66. Quantified plots are shown to illustrate the overall trend of p66 and p51 production relative to the reduction of the intact protein (p90) (Figure S8a). Since there were at least four cleavage sites and some of these were close to each other, detail quantification of all the bands could not be performed.

Because these processing experiments were performed at pH 5, while the SEC experiments were performed at pH 7.5, we cannot quantitatively compare the maturation results with those from SEC. We only evaluate the relative differences in PR processing of PR‐RT compared to PR(T26A)‐RT or PR‐RT(W401A). Importantly, the maturation results of PR(T26A)‐RT (Figure 6b and S8b) exhibited features similar to those of PR‐RT (Figure 6a and S8a), suggesting no significant difference in the protein conformation with respect to the degree of protection of the PR‐RT cleavage sites. PR‐RT(W401A) was also processed to p66 and p51 but with lower band intensities compared to PR‐RT and PR(T26A)‐RT (Figure 6c), presumably due to rapid degradation of the W401A monomers.

2.7. Synergy of PR and RT dimerization in PR‐RT

For a better understanding of PR‐RT dimerization, we curated known dimer dissociation constants, K d s, of PR and the model precursors from our data and those of others, as published in the literature (Table S2). We selected groups of data that were recorded at similar conditions, to enable relative comparisons of K d s. The K d of PR(D25A) is similar to that of PR(D25N) (Sayer et al., 2008) and is estimated to be ~0.9 μM, calculated from the intensity ratios of the monomer and dimer peaks in NMR spectra (Figure S12). The presence of even two selected residues in addition to the N‐terminal methionine, such as MI‐PR or MG‐PR, impact protease dimerization (Ishima et al., 2003). Note, the K d calculated from the protein concentration‐dependence of PR catalytic activity, used in this previous paper, can be influenced by the substrate–PR interaction. Thus, we used the published NMR spectra to re‐calculate K d values for MI‐PR and MG‐PR from the NMR spectral intensities, obtaining values of 1.8 and 0.3 mM, respectively (Figure S13) (Ishima et al., 2003). These values are 1800‐ and 300‐fold weaker, respectively, than those of the inactivated PRs.

The K d of PR‐RT was qualitatively estimated to be ~0.32 μM, based on the relative intensity changes of dimer and monomer elution peaks in SEC (Figure S14). This was slightly lower than that of PR(T26A)‐RT, ~1.3 μM (Figure S14). Precise determination of K d was not possible because PR‐RT contains an aggregate component. In addition, an equilibrium state is not established in the SEC column with a flow. Thus, we qualitatively evaluated PR‐RT K d relative to that of p66 (RT) homodimer, p66/p66, which was applied to the SEC at the same protein concentration, 8 μM, as that used for PR‐RT. The K d s of the PR‐RT proteins were much higher than that of the mature RT heterodimer, p66/p51, 0.02 μM, and were slightly lower than that of p66/p66, 2.8 μM. Differences in relative monomer‐dimer peak intensities between PR‐RT and PR(T26A)‐RT suggest that the PR region may contribute slightly to PR‐RT dimerization, but not sufficient to introduce structural changes in the RT region to allow p66/p51 interface formation.

3. DISCUSSION

In this study, because PR‐RT is a polyprotein with multiple inter‐domain or inter‐protein sites that can be targeted by E. coli enzymes, there were crucial considerations in the sample preparations. First, we demonstrated that our PR‐RTs remain intact without undergoing degradation during the incubation experiment (Figure 2d). This observation indicates that there is no significant contamination of E. coli protease. Second, due to the tendency of PR‐RTs to oligomerize or aggregate at high protein concentration (~1 mg/ml) (Figure S2), we evaluated the total elution volumes of the SEC data and confirmed elution of the majority of the injected protein (Table 2).

SEC and SEC‐MALS experiments showed both monomer and dimer elution peaks for PR‐RT and PR(T26A)‐RT, as well as oligomer, while PR‐RT(W401A) was mostly monomer (Figures 3 and 4). The propensity of PR‐RT(W401A), such as exposed hydrophobic surfaces in the monomer, may result in more aggregate at the DLS concentration, 1 mg/ml (Figure S2). Based on the monomer and dimer elution peak intensities, we qualitatively estimated the PR‐RT K d to be ~0.3 μM (Table S2 and Figure S14). The p66/p51 K d , 0.02 μM, is over 10‐fold lower than the previously determined value, 0.31 (Venezia et al., 2006). There may be two reasons for the difference: (1) our SEC buffer contains 250 mM NaCl but the buffer for sedimentation equilibrium contains 25 mM NaCl; (2) in the SEC, p66/p51 may not reach true equilibrium when the energy barrier for the dissociation is high. As described above, we only evaluate relative differences of the K d values for PR‐RT and RTs. Although our estimation of the K d of PR‐RT is qualitative, this estimate is supported by the stark contrast between the SEC elution profiles of PR‐RTs in the presence and absence of DRV or RPV (Figures 4 and S5). In addition to the SEC and SEC‐MALS results (Figures 3 and 4), similar propensities between PR‐RT and PR(T26A)‐RT were also observed in reverse transcriptase activity and RT maturation activity (Figures 5 and 6). These results support that the dimerization effect of the PR region in PR‐RT is weak.

In a previous study using Pol that contains IN region, the Superose 6 gel filtration profile showed a broad single peak, mainly with a dimer fraction (Harrison et al., 2022). Our data demonstrate a degree of dimer formation of PR‐RTs in solution, without the IN region. Our observation of both dimer and monomer fractions of PR‐RT, suggestive of ~μM K d , may be reasonable to minimize PR activation in the cellular environment before virus formation. In addition, observation of weak dimerization at the PR interface of PR‐RT with N‐terminal flanking amino acids is consistent with previous PR precursor studies (Table S2); the presence of such flanking amino acids could make the processing site at the C‐terminal end of PR more exposed to solution, allowing cleavage.

The actual dimerization of Gag‐Pol in the cellular environment or within the virus could be influenced by Gag and/or Gag‐Pol dimerization, IN oligomerization, RNA or tRNA interaction with Pol, Gag and Gag‐Pol processing (Cherepanov et al., 2003; Huang et al., 1994; Kessl et al., 2016; Khoder‐Agha et al., 2018; Kobbi et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2012; Mak et al., 1994; Pettit et al., 2003; Pettit et al., 2005). Thus, the findings in this study may not be directly applied to understand Pol maturation in HIV‐1. Given that IN forms oligomers and tends to aggregate (Cherepanov et al., 2003; Deprez et al., 2000; Jenkins et al., 1996), biophysical characterization of PR‐RT dimerization provides information useful for comprehensive understanding of maturation of Pol encoded enzymes.

4. CONCLUSIONS

We conclude that the RT domain in PR‐RT drives dimerization of the precursor protein based on our SEC and SEC‐MALS experiments, showing both monomer and dimer fractions in the elution profiles of PR‐RT and PR(T26A)‐RT. The dimer dissociation constant of PR‐RT is estimated to be higher than that of the mature RT heterodimer, p66/p51, but is slightly lower than the premature RT homodimer, p66/p66. Our results consistently indicate that the RT dimer‐interface plays a crucial role in the dimerization in PR‐RT, whereas the PR dimer‐interface has a lesser role.

5. MATERIALS AND METHODS

5.1. Materials

PR‐RT constructs: PR‐RTs were cloned with Expresso® T7 Sumo system (Lucigen, Middleton, WI). PR‐RT sequence is from HIV‐1 isolate BH10 with introduction of behavior improvement mutations and sequence optimization: D25A/C67A/C95A in PR and C38V/C280S in RT. PR‐RT was cloned with N‐terminal hexa‐histidine tag preceding the SUMO protease sequence, a TEV cleavage site and a C‐terminal Strep tag. Two amino acid residues from the transframe region (p6*), Asn‐Phe, were added preceding the PR protein, termed Δp6*. To evaluate PR‐RT dimerization at the RT interface, PR‐RT(W401A) was prepared from the PR‐RT. PR(T26A)‐RT was similarly prepared but without the TEV‐protease cleavage site and was thus 12 residues shorter compared to PR‐RT.

Active PR and 15N‐labeled inactive PR(D25A) were expressed and purified as described previously with the amino acid sequence: PQITL WKRPL VTIRI GGQLK EALLD(or A) TGADD TVIEE MNLPG KWKPK MIGGI GGFIK VRQYD QIPIE IAGHK AIGTV LVGPT PVNII GRNLL TQIGA TLNF (Ilina et al., 2018; Ishima et al., 1999, 2007; Khan et al., 2018). HIV‐1 p66, containing C38V/C280S mutation similar to that of PR‐RT was prepared as described previously (Slack et al., 2019). Heterodimer RT, that is, p66/p51, contains C38 and C280 (Ilina et al., 2018; le Grice & Gruninger‐Leitch, 1990). DRV was synthesized by Celia Schiffer's group (Khan et al., 2018; Nalam et al., 2013). RPV was obtained through NIH AIDS Reagent Program (Reagent #, 12147).

5.2. Protein expression and purification

PR‐RT, PR(T26A)‐RT, and PR‐RT(W401A) were expressed using Escherichia coli Rosetta (DE3) cells. The respective clones were inoculated in 50 ml LB medium with 50 μg/ml kanamycin and 25 μg/ml chloramphenicol overnight at 37°C and 225 rpm. Seeding cultures were diluted in 200 ml LB medium with 50 μg/ml kanamycin and 25 μg/ml chloramphenicol to a final cell density OD 600 nm of 0.2. The cells were grown overnight at 37°C and 225 rpm. Cultures were then diluted (1:50) in 1 L LB medium at an initial OD 600 nm of 0.25 and with the same antibiotics concentrations used for expression. Cells were incubated at 37°C and 225 rpm until OD 600 nm reached 1.4. Temperature was cooled to 18°C and protein expression was induced with 0.5 M β‐D‐1‐thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Cell cultures were grown at 18°C and 225 rpm for 16 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4°C, 4000 rpm for 20 min.

PR‐RT, PR(T26A)‐RT and PR‐RT(W401A) pellets were each resuspended in a 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer containing 150 mM NaCl at pH 8.0, and sonicated (6 s ON and 10 s OFF for 10 min total). Lysed cells were centrifugated at 20,000 rpm for 45 min at 4°C. Inclusion body pellets were resuspended in a 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer containing 1 M urea at pH 8.0, sonicated and centrifugated at 20,000 rpm for 45 min at 4°C. Then, they were finally solubilized in a 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer containing 8 M urea and a protease inhibitor cocktail (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA), at pH 8.0, followed by sonication and centrifugation to collect the supernatant.

The supernatant of each protein in 8 M urea was filtered in a 0.45 μm membrane and loaded into a 5 ml HisTrap HP nickel affinity column (Cytiva, Global Life Science Solutions, Marlborough, MA) connected to a ÄKTA system with 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer containing 8 M urea, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM beta‐mercaptoethanol at pH 8.0, and eluted by applying a 500 mM imidazole gradient. Eluted protein was concentrated and loaded in a gel filtration column HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 prep grade (Cytiva), pre‐equilibrated with the 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer, containing 8 M urea, 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT at pH 8.0. Protein was refolded by dropwise dilution to a 25 mM HEPES buffer, containing 125 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mM DTT and the protease inhibitor cocktail at pH 7.5. Protein was then loaded into a Heparin column (Cytiva), equilibrated with a 25 mM HEPES buffer containing 10% glycerol, 0.02% NaN3 and 1 mM DTT at pH 7.5, and was eluted by applying a 1 M NaCl gradient. At each step, fractions were analyzed by SDS‐PAGE (Bio‐Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA) for protein purity. The final products were confirmed by SDS‐PAGE and mass spectrometry (a Bruker LC‐ESI‐TOF system, Bruker Daltonics Inc., Billerica, MA).

Buffer conditions for protein experiments were further determined by carrying out dynamic light scattering experiments at 1 mg/ml protein concentration (DynaPro, Wyatt Technology, Santa Barbara, CA). The degree of contamination by E. coli protease was assessed by incubating the proteins at 8 μM concentration (calculated as a monomer) in the presence of 2 μM dsDNA (explained below) for up to 14 h at 37°C. Note, molar protein concentration for PR‐RT is described as a monomer for SEC and SEC‐MALS experiments, but as a dimer for the experiments that require dimerization for function, such as the reverse transcriptase assay and RT maturation assay.

5.3. SEC and SEC‐MALS experiments

SEC‐MALS experiments for PR‐RT, PR(T26A)‐RT and PR‐RT(W401A), as well as p66, were performed using a Superdex Increase 200 10/300 GL column (Cytiva), connected to the DAWIN HELEOS II light scattering detector SEC‐MALS with a Optilab rEX (Wyatt Technology, Santa Barbara, CA). Each protein sample of 100 μl at 8 μM concentration (calculated as a monomer) was loaded onto the pre‐equilibrated column with a 25 mM HEPES buffer, containing 2% glycerol, 250 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT at pH 7.5 at room temperature, at 0.5 ml/min flow rate. The molecular masses of the eluted protein species were determined using the ASTRA V.7.1.2 program (Wyatt Technologies). Note, the glycerol concentration was lowered in the SEC‐MALS experiments to accurately determine the molecular mass. In the lower glycerol concentration, oligomerization of the proteins is expected. To separate the dimer peak from a larger molecular mass component, an online filter holder for ÄKTA systems (Cytiva, Marlborough, MA) was attached prior to the SEC column. The experiment was repeated at a different protein concentration to verify the elution.

Analytical SEC experiments for PR‐RT, PR(T26A)‐RT and PR‐RT(W401A) were performed by injecting 90 μl of each 8 μM protein in a Superdex Increase 200 10/300 GL column (Cytiva) pre‐equilibrated with a 25 mM HEPES, containing 10% glycerol, 250 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT at pH 7.5. The proteins were eluted at 0.5 ml/min flow rate at room temperature. Experiments were also performed by injecting PR‐RT at 29 μM, PR(T26A)‐RT at 18.5 μM and PR‐RT(W401A) at 25 μM concentration. SEC experiments were also performed by injecting the PR‐RT and the mutants in the presence of DRV or RPV that was added to the loading at 1:2 = dimer protein: inhibitor ratio. As controls, SEC of p66 protein at 8 μM (i.e., 4 μM as p66/p66) and p66/p51 at 1 μM, each as dimer, were also carried out to allow comparison with the dimer dissociation propensity of PR‐RT.

5.4. Reverse transcriptase assay

Reverse transcriptase assays for PR‐RT, PR(T26A)‐RT, and PR‐RT(W401A) were performed using the EnzCheck Reverse Transcriptase kit (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA). Protein concentration dependence experiments were examined by preparing serially diluted proteins, ranging from 12.5 to 200 nM concentration. DRV dependence of the reverse transcriptase activity was performed at 200 μM PR‐RTs (calculated as a dimer), by preparing serially diluted stock DRV in 100% DMSO, and making the DMSO concentration in the protein‐DRV mix solution and final reaction mixture 4% and 0.8%, respectively. In each reaction, 5 μl protein or protein‐DRV solution was mixed with 20 μl of reaction buffer provided by the kit, which contains 60 mM Tris–HCl, 60 mM KCl, 8 mM MgCl2, 13 mM DTT, and 100 μM dTTP at pH 8.1. Each reaction was performed at 20°C for 20 min, and stopped by adding 2 μl of 200 mM EDTA. Polymerization was detected by adding PicoGreen to the samples and its fluorescence was measured using TECAN Spark fluorescence equipment (Tecan, Switzerland) with excitation/emission of 480/520 nm, respectively, in 30 ms.

5.5. RT maturation assay

Monitoring of p66 and p51 production from PR‐RT and the mutants by HIV‐1 PR, that is, RT maturation assay (Ilina et al., 2018, 2020; Slack et al., 2019), was performed in the presence and absence of dsDNA. In previous studies, tRNA and dsRNA were used as nucleic acids that enhance RT maturation because these RNA molecules are packaged into the virus along with Gag‐Pol proteins (Ilina et al., 2018, 2020; Slack et al., 2019). In the current study, we utilized dsDNA instead, as a tool to compare relative differences in RT maturation between the three PR‐RT variants. The oligo sequences used for these experiments are ~30 bp‐long integrase strand‐transfer (INST) sequences, known to bind RT (Li et al., 2012): 5′‐ACTGCTAGAGATTTTCCACACTGACTAAAAGG and INST2 5′‐CCTTTTAGTCAGTGTGGAAAATCTCTAGCA (IDT technologies). dsDNA was annealed and aliquoted for assays. Processing of PR‐RT, PR(T26A)‐RT, and PR‐RT(W401A) was performed at 4 μM protein concentration (calculated as a dimer) by adding 1 μM PR (calculated as a dimer) with/without 4 μM dsDNA, in 20 mM acetate buffer pH 5.0 at 37°C. Reaction was stopped by addition of Tricine buffer and denaturation at 95°C for 1 min. Evaluation of PR‐RT and mutant protein processing was performed by SDS‐PAGE (Biorad).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Rieko Ishima: Conceptualization; writing – review and editing; supervision; funding acquisition. Brisa Caroline Alves Chagas: Writing – original draft; investigation; formal analysis; writing – review and editing; conceptualization. Xiaohong Zhou: Validation; writing – review and editing. Michel Guerrero: Investigation; writing – review and editing. Tatiana V. Ilina: Conceptualization; methodology; writing – review and editing.

FUNDING INFORMATION

NIH P50 AI150481, NIH R01 GM135919, and University of Pittsburgh.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

DATA S1. TABLE S1. Protein UV260/UV280 and the mass results.

TABLE S2. Dimer dissociation constants, K d s, of HIV‐1 PR, RT, and model precursors.

FIGURE S1. Terminal β‐sheet structure of HIV‐1 PR.

FIGURE S2. Heat map display of screening results of buffer conditions obtained using DLS.

FIGURE S3. SEC‐MALS of PR‐RT and the mutants at two different protein concentrations.

FIGURE S4. SEC of PR‐RT and the mutants at two protein concentrations.

FIGURE S5. SEC of PR‐RT and the mutants in the presence of RPV.

FIGURE S6. Individual reverse transcriptase assay data and the DMSO dependence of the activity.

FIGURE S7. Individual reverse transcriptase assay data in the presence of DRV.

FIGURE S8. Intensity of SDS gel bands shown in Figure 6a,b.

FIGURE S9. Entire gel of the RT maturation assay.

FIGURE S10. Repeat of the RT maturation assay.

FIGURE S11. Repeat of the RT maturation assay in the presence of molecular marker.

FIGURE S12. NMR spectrum of PR(D25A).

FIGURE S13. Revisit of the previously published NMR spectra of SFNF‐PR(D25N), MI‐PR and MG‐PR.

FIGURE S14. Decomposition of monomer and dimer elution peaks from the SEC profiles.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Fatema Bhinderwala, Christina Monnie, Troy Krzysiak, and Teresa Brosenitsch for instruction of the fluorescence measurements, SEC‐MALS usage, technical assistance of Akta systems, and critical reading of the manuscript, respectively.

Chagas BCA, Zhou X, Guerrero M, Ilina TV, Ishima R. Interplay between protease and reverse transcriptase dimerization in a model HIV‐1 polyprotein. Protein Science. 2024;33(7):e5080. 10.1002/pro.5080

Review Editor: Zengyi Chang.

Contributor Information

Tatiana V. Ilina, Email: ilina.tv@gmail.com.

Rieko Ishima, Email: ishima@pitt.edu.

REFERENCES

- Agniswamy J, Sayer JM, Weber IT, Louis JM. Terminal interface conformations modulate dimer stability prior to amino terminal autoprocessing of HIV‐1 protease. Biochemistry. 2012;51:1041–1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavand MR, Wagner R, Richmond TJ. HIV‐1 reverse transcriptase: polymerization properties of the p51 homodimer compared to the p66/p51 heterodimer. Biochemistry. 1993;32:10543–10552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhavyasri KSM, Sumakanth M. Simultaneous method development, validation and stress studies of darunavir and ritonavir in bulk and combined dosage form using UV spectroscopy. Scholars Academic Journal of Pharmacy. 2020;9:244–252. [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay D, Evans DB, Deibel MR, Vosters AF, Eckenrode FM, Einspahr HM, et al. Purification and characterization of heterodimeric human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV‐1) reverse transcriptase produced by in vitro processing of p66 with recombinant HIV‐1 protease. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992;267:14227–14232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherepanov P, Maertens G, Proost P, Devreese B, van Beeumen J, Engelborghs Y, et al. HIV‐1 integrase forms stable tetramers and associates with LEDGF/p75 protein in human cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:372–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry E, Liang C, Rong L, Quan Y, Inouye P, Li X, et al. Characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type‐1 (HIV‐1) particles that express protease‐reverse transcriptase fusion proteins. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1998;284:43–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark AD Jr, Jacobo‐Molina A, Clark P, Hughes SH, Arnold E. Crystallization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase with and without nucleic acid substrates, inhibitors, and an antibody fab fragment. Methods in Enzymology. 1995;262:171–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffin JM, Hughes SH, Varmus HE. The interactions of retroviruses and their hosts. In: Coffin JM, Hughes SH, Varmus HE, editors. Retroviruses. New York: Cold Spring Harbor; 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke PL, Nutt RF, Brady SF, Garsky VM, Ciccarone TM, Leu CT, et al. HIV‐1 protease specificity of peptide cleavage is sufficient for processing of gag and pol polyproteins. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1988;156:297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies JF II, Hostomska Z, Hostomsky Z, Jordan SR, Matthews DA. Crystal structure of the ribonuclease H domain of HIV‐1 reverse transcriptase. Science. 1991;252:88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deprez E, Tauc P, Leh H, Mouscadet JF, Auclair C, Brochon JC. Oligomeric states of the HIV‐1 integrase as measured by time‐resolved fluorescence anisotropy. Biochemistry. 2000;39:9275–9284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Divita G, Rittinger K, Geourjon C, Deleage G, Goody RS. Dimerization kinetics of HIV‐1 and HIV‐2 reverse transcriptase: a two step process. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1995;245:508–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyda F, Hickman AB, Jenkins TM, Engelman A, Craigie R, Davies DR. Crystal structure of the catalytic domain of HIV‐1 integrase: similarity to other polynucleotidyl transferases. Science. 1994;266:1981–1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison J, Passos DO, Bruhn JF, Bauman JD, Tuberty L, DeStefano JJ, et al. Cryo‐EM structure of the HIV‐1 pol polyprotein provides insights into virion maturation. Science Advances. 2022;8:eabn9874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison J, Tuske S, Das K, Ruiz FX, Bauman JD, Boyer PL, et al. Crystal structure of a retroviral polyprotein: prototype foamy virus protease‐reverse transcriptase (PR‐RT). Viruses. 2021;13:1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl MJ, Bodem J, Jochheim F, Rethwilm A, Rosch P, Wohrl BM. Regulation of foamy virus protease activity by viral RNA: a novel and unique mechanism among retroviruses. Journal of Virology. 2011;85:4462–4469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl MJ, Schweimer K, Reger MH, Schwarzinger S, Bodem J, Rosch P, et al. Formation of transient dimers by a retroviral protease. Biochemical Journal. 2010;427:197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi H, Takamune N, Nirasawa T, Aoki M, Morishita Y, Das D, et al. Dimerization of HIV‐1 protease occurs through two steps relating to the mechanism of protease dimerization inhibition by darunavir. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U S A. 2014;111:12234–12239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill M, Tachedjian G, Mak J. The packaging and maturation of the HIV‐1 Pol proteins. Current HIV Research. 2005;3:73–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu WS, Hughes SH. HIV‐1 reverse transcription. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 2012;2:a006882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Mak J, Cao Q, Li Z, Wainberg MA, Kleiman L. Incorporation of excess wild‐type and mutant tRNA(3Lys) into human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Journal of Virology. 1994;68:7676–7683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulme AE, Perez O, Hope TJ. Complementary assays reveal a relationship between HIV‐1 uncoating and reverse transcription. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U S A. 2011;108:9975–9980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilina TV, Slack RL, Elder JH, Sarafianos SG, Parniak MA, Ishima R. Effect of tRNA on the maturation of HIV‐1 reverse transcriptase. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2018;430:1891–1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilina TV, Slack RL, Guerrero M, Ishima R. Effect of lysyl‐tRNA synthetase on the maturation of HIV‐1 reverse transcriptase. ACS Omega. 2020;5:16619–16627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishima R, Freedberg DI, Wang YX, Louis JM, Torchia DA. Flap opening and dimer‐interface flexibility in the free and inhibitor‐bound HIV protease, and their implications for function. Structure. 1999;7:1047–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishima R, Torchia DA, Louis JM. Mutational and structural studies aimed at characterizing the monomer of HIV‐1 protease and its precursor. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282:17190–17199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishima R, Torchia DA, Lynch SM, Gronenborn AM, Louis JM. Solution structure of the mature HIV‐1 protease monomer: insight into the tertiary fold and stability of a precursor. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:43311–43319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacks T, Power MD, Masiarz FR, Luciw PA, Barr PJ, Varmus HE. Characterization of ribosomal frameshifting in HIV‐1 gag‐pol expression. Nature. 1988;331:280–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobo‐Molina A, Ding J, Nanni RG, Clark AD Jr, Lu X, Tantillo C, et al. Crystal structure of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase complexed with double‐stranded DNA at 3.0A resolution shows bent DNA. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U S A. 1993;90:6320–6324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins TM, Engelman A, Ghirlando R, Craigie R. A soluble active mutant of HIV‐1 integrase: involvement of both the core and carboxyl‐terminal domains in multimerization. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:7712–7718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jochmans D, Anders M, Keuleers I, Smeulders L, Krausslich HG, Kraus G, et al. Selective killing of human immunodeficiency virus infected cells by non‐nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor‐induced activation of HIV protease. Retrovirology. 2010;7:89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessl JJ, Kutluay SB, Townsend D, Rebensburg S, Slaughter A, Larue RC, et al. HIV‐1 integrase binds the viral RNA genome and is essential during virion morphogenesis. Cell. 2016;166:1257–1268.e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan SN, Persons JD, Paulsen JL, Guerrero M, Schiffer CA, Kurt‐Yilmaz N, et al. Probing structural changes among analogous inhibitor‐bound forms of HIV‐1 protease and a drug‐resistant mutant in solution by nuclear magnetic resonance. Biochemistry. 2018;57:1652–1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoder‐Agha F, Dias JM, Comisso M, Mirande M. Characterization of association of human mitochondrial lysyl‐tRNA synthetase with HIV‐1 pol and tRNA3(Lys). BMC Biochemistry. 2018;19:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobbi L, Octobre G, Dias J, Comisso M, Mirande M. Association of mitochondrial Lysyl‐tRNA synthetase with HIV‐1 GagPol involves catalytic domain of the synthetase and transframe and integrase domains of pol. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2011;410:875–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlstaedt LA, Wang J, Friedman JM, Rice PA, Steitz TA. Crystal structure at 3.5A resolution of HIV‐1 reverse transcriptase complexed with an inhibitor. Science. 1992;256:1783–1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda DG, Bauman JD, Challa JR, Patel D, Troxler T, Das K, et al. Snapshot of the equilibrium dynamics of a drug bound to HIV‐1 reverse transcriptase. Nature Chemistry. 2013;5:174–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapatto R, Blundell T, Hemmings A, Overington J, Wilderspin A, Wood S, et al. X‐ray analysis of HIV‐1 proteinase at 2.7 a resolution confirms structural homology among retroviral enzymes. Nature. 1989;342:299–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- le Grice SF, Gruninger‐Leitch F. Rapid purification of homodimer and heterodimer HIV‐1 reverse transcriptase by metal chelate affinity chromatography. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1990;187:307–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SK, Potempa M, Swanstrom R. The choreography of HIV‐1 proteolytic processing and virion assembly. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2012;287:40867–40874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Koh Y, Engelman A. Correlation of recombinant integrase activity and functional preintegration complex formation during acute infection by replication‐defective integrase mutant human immunodeficiency virus. Journal of Virology. 2012;86:3861–3879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis JM, Ishima R, Aniana A, Sayer JM. Revealing the dimer dissociation and existence of a folded monomer of the mature HIV‐2 protease. Protein Science. 2009;18:2442–2453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis JM, Nashed NT, Parris KD, Kimmel AR, Jerina DM. Kinetics and mechanism of autoprocessing of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease from an analog of the Gag‐Pol polyprotein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U S A. 1994;91:7970–7974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis JM, Tozser J, Roche J, Matuz K, Aniana A, Sayer JM. Enhanced stability of monomer fold correlates with extreme drug resistance of HIV‐1 protease. Biochemistry. 2013;52:7678–7688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis JM, Wondrak EM, Kimmel AR, Wingfield PT, Nashed NT. Proteolytic processing of HIV‐1 protease precursor, kinetics and mechanism. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:23437–23442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe DM, Aitken A, Bradley C, Darby GK, Larder BA, Powell KL, et al. HIV‐1 reverse transcriptase: crystallization and analysis of domain structure by limited proteolysis. Biochemistry. 1988;27:8884–8889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak J, Jiang M, Wainberg MA, Hammarskjold M‐L, Rekosh D, Kleiman L. Role of Pr160gag‐pol in mediating the selective incorporation of tRNALys into human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particles. Journal of Virology. 1994;68:2065–2072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M, Schneider J, Sathyanarayana BK, Toth MV, Marshall GR, Clawson L, et al. Structure of complex of synthetic HIV‐1 protease with a substrate‐based inhibitor at 2.3A resolution. Science. 1989;246:1149–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalam MN, Ali A, Reddy GS, Cao H, Anjum SG, Altman MD, et al. Substrate envelope‐designed potent HIV‐1 protease inhibitors to avoid drug resistance. Chemistry and Biology. 2013;20:1116–1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navia MA, Fitzgerald PM, McKeever BM, Leu CT, Heimbach JC, Herber WK, et al. Three‐dimensional structure of aspartyl protease from human immunodeficiency virus HIV‐1. Nature. 1989;337:615–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oroszlan S, Luftig RB. Retroviral proteinases. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 1990;157:153–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit SC, Gulnik S, Everitt L, Kaplan AH. The dimer interfaces of protease and extra‐protease domains influence the activation of protease and the specificity of GagPol cleavage. Journal of Virology. 2003;77:366–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit SC, Lindquist JN, Kaplan AH, Swanstrom R. Processing sites in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV‐1) Gag‐Pro‐Pol precursor are cleaved by the viral protease at different rates. Retrovirology. 2005;2:66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee SY, Gonzales MJ, Kantor R, Betts BJ, Ravela J, Shafer RW. Human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase and protease sequence database. Nucleic Acids Research. 2003;31:298–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayer JM, Liu F, Ishima R, Weber IT, Louis JM. Effect of the active site D25N mutation on the structure, stability, and ligand binding of the mature HIV‐1 protease. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283:13459–13470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt T, Schwieters CD, Clore GM. Spatial domain organization in the HIV‐1 reverse transcriptase p66 homodimer precursor probed by double electron–electron resonance EPR. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U S A. 2019;116:17809–17816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharaf NG, Poliner E, Slack RL, Christen MT, Byeon IJ, Parniak MA, et al. The p66 immature precursor of HIV‐1 reverse transcriptase. Proteins. 2014;82:2343–2352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharaf NG, Xi Z, Ishima R, Gronenborn AM. The HIV‐1 p66 homodimeric RT exhibits different conformations in the binding‐competent and ‐incompetent NNRTI site. Proteins. 2017;85:2191–2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma SK, Fan N, Evans DB. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV‐1) recombinant reverse transcriptase. Asymmetry in p66 subunits of the p66/p66 homodimer. FEBS Letters. 1994;343:125–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack RL, Ilina TV, Xi Z, Giacobbi NS, Kawai G, Parniak MA, et al. Conformational changes in HIV‐1 reverse transcriptase that facilitate its maturation. Structure. 2019;27:1581–1593.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smerdon SJ, Jager J, Wang J, Kohlstaedt LA, Chirino AJ, Friedman JM, et al. Structure of the binding site for nonnucleoside inhibitors of the reverse transcriptase of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U S A. 1994;91:3911–3915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surleraux DL, Tahri A, Verschueren WG, Pille GM, de Kock HA, Jonckers TH, et al. Discovery and selection of TMC114, a next generation HIV‐1 protease inhibitor. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2005;48:1813–1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachedjian G, Aronson HE, de los Santos M, Seehra J, McCoy JM, Goff SP. Role of residues in the tryptophan repeat motif for HIV‐1 reverse transcriptase dimerization. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2003;326:381–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tachedjian G, Moore KL, Goff SP, Sluis‐Cremer N. Efavirenz enhances the proteolytic processing of an HIV‐1 pol polyprotein precursor and reverse transcriptase homodimer formation. FEBS Letters. 2005;579:379–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinite B, Zhang H, Levy DN. NNRTI‐induced HIV‐1 protease‐mediated cytotoxicity induces rapid death of CD4 T cells during productive infection and latency reversal. Retrovirology. 2019;16:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venezia CF, Howard KJ, Ignatov ME, Holladay LA, Barkley MD. Effects of efavirenz binding on the subunit equilibria of HIV‐1 reverse transcriptase. Biochemistry. 2006;45:2779–2789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitcomb JM, Kumar R, Hughes SH. Sequence of the circle junction of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: implications for reverse transcription and integration. Journal of Virology. 1990;64:4903–4906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wlodawer A, Erickson JW. Structure‐based inhibitors of HIV‐1 protease. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 1993;62:543–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wlodawer A, Miller M, Jaskolski M, Sathyanarayana BK, Baldwin E, Weber IT, et al. Conserved folding in retroviral proteases: crystal structure of a synthetic HIV‐1 protease. Science. 1989;245:616–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wondrak EM, Nashed NT, Haber MT, Jerina DM, Louis JM. A transient precursor of the HIV‐1 protease. Isolation, characterization, and kinetics of maturation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:4477–4481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Fricke T, Diaz‐Griffero F. Inhibition of reverse transcriptase activity increases stability of the HIV‐1 core. Journal of Virology. 2013;87:683–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerbato JM, Tachedjian G, Sluis‐Cremer N. Nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors reduce HIV‐1 production from latently infected resting CD4+ T cells following latency reversal. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2017;61:e01736‐16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng XH, Pedersen LC, Gabel SA, Mueller GA, Cuneo MJ, DeRose EF, et al. Selective unfolding of one ribonuclease H domain of HIV reverse transcriptase is linked to homodimer formation. Nucleic Acids Research. 2014;42:5361–5377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

DATA S1. TABLE S1. Protein UV260/UV280 and the mass results.

TABLE S2. Dimer dissociation constants, K d s, of HIV‐1 PR, RT, and model precursors.

FIGURE S1. Terminal β‐sheet structure of HIV‐1 PR.

FIGURE S2. Heat map display of screening results of buffer conditions obtained using DLS.

FIGURE S3. SEC‐MALS of PR‐RT and the mutants at two different protein concentrations.

FIGURE S4. SEC of PR‐RT and the mutants at two protein concentrations.

FIGURE S5. SEC of PR‐RT and the mutants in the presence of RPV.

FIGURE S6. Individual reverse transcriptase assay data and the DMSO dependence of the activity.

FIGURE S7. Individual reverse transcriptase assay data in the presence of DRV.

FIGURE S8. Intensity of SDS gel bands shown in Figure 6a,b.

FIGURE S9. Entire gel of the RT maturation assay.

FIGURE S10. Repeat of the RT maturation assay.

FIGURE S11. Repeat of the RT maturation assay in the presence of molecular marker.

FIGURE S12. NMR spectrum of PR(D25A).

FIGURE S13. Revisit of the previously published NMR spectra of SFNF‐PR(D25N), MI‐PR and MG‐PR.

FIGURE S14. Decomposition of monomer and dimer elution peaks from the SEC profiles.